Older people are at increased risk for burn-related injury and death. One reason is that our skin gets thinner as we age, and thinner skin provides less protection against burns and scalds. While superficial burns heal on their own, severe burns require medical treatment, can develop complications, and heal slowly. Older people also have reduced skin sensitivity and in addition, may not be able to move quickly, so they may not react to or be able to move away from heat or flame in time to minimize injury. The increased contact time with the burn source causes a more severe burn. Recovery may be prolonged and complicated by a change in living situation, if the person needs to be in a rehabilitation facility or any place other than at home.

Changes in the body and skin caused by normal aging also put older people at increased risk for hyperthermia and hypothermia. A reduction in the fat layer under the skin and the thinning of the skin mean that there is less natural insulation. If the body is not able to respond appropriately and adequately to external temperature conditions, extreme changes in internal body temperature can result. And they can be very dangerous. A dangerous rise in internal temperature is called hyperthermia; a dangerous drop in internal temperature is called hypothermia. Additional hyper- and hypothermia risk factors for older people include not realizing that they are too hot or too cold and being slow to respond appropriately to the body’s temperature needs. For example, they may not promptly put on a sweater when cold or take a drink of cool water when hot. Older people may be less well nourished and thus have a lower metabolic rate; they may be more sedentary and thus generate less heat because they are not moving; they may be less well off financially and not able to pay for adequate heating or cooling.

Both ends of the thermal spectrum—too hot and too cold—can cause injury. This chapter is about how to prevent burns and how to prevent hypothermia and hyperthermia.

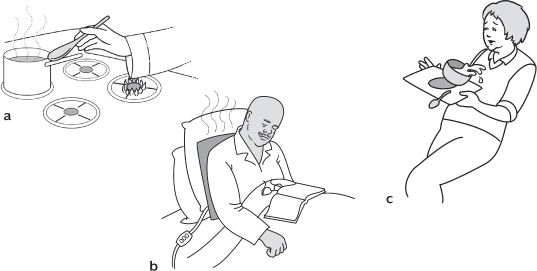

We can group the causes of burns into three categories: being burned through contact with open flame, being burned through contact with a hot surface, and being burned through contact with a hot liquid or steam. (Figure 3.1 shows examples.) Burns caused by contact with hot liquids or steam are called scalds. Contact burns and scalds may be minor (producing redness), moderate (blisters), or severe (deep, third degree), depending on how hot the surface or liquid you contact is and how long you stay in contact with that surface or liquid. The severity of open flame burns is related to how quickly and in what direction the clothing you are wearing burns, how long the flames continue to burn before being extinguished, how long it takes for emergency medical care to be administered, and how long it takes to reach a burn center for specialized treatment, if necessary.

Figure 3.1. Three categories of burn: (a) open flame burn, (b) contact burn, and (c) scald

Burns caused by open flames are usually more dangerous than contact burns, because more surface area can potentially burn, as flames spread through clothing. Likewise, scalds are usually more dangerous than contact burns because more surface area can be affected and the contact period with the skin can be longer. If you touch a hot pan while taking it out of the oven, only the part of your hand in contact with the pan gets burned; if you knock over a pot of coffee, the hot liquid could spill down your pants and burn your legs; if you reach over a candle and your sleeve catches fire, the fire could quickly spread to encompass the whole torso. In addition, someone whose clothing is on fire may panic and run around, instead of doing the recommended “stop, drop, and roll.” Someone who has spilled hot liquid on herself may not think to take the clothes off immediately or to pour cold water over the affected area. And, while it’s usually easy to hold a mildly burned hand under cool tap water to prevent further injury, scalds and burns from open flames are not as easy to remedy and often require complicated treatment.

Burns and scalds most commonly occur in the kitchen, because that’s where we cook, heat foods, and eat. But people also get burns and scalds in rooms with such products as space heaters, heating pads, hair dryers, irons, bathtubs, and cigarette lighters. A wide variety of circumstances can set the stage for a burn or scald. Here are some accounts of burns and scalds among people 65 and older treated in emergency departments in 2010:

Picked up a hot pot from the stove and burned hand

Reached over a stove to grab a pot and sleeve caught fire

Turned around while cooking at a gas stove and nightgown caught fire

Hair caught fire while blowing out a candle

Trying to light the furnace when a flashback burned the person’s face

Backed into a heater and shirt caught fire

Fell asleep on a heating pad and back got burned

Burning trash in the back yard and pants caught on fire

Spilled boiling water, burning both thighs

Poured water on a grease fire, and the fire flashed up and burned the person’s face

Frying potatoes while wearing oxygen equipment, and flames burned the person’s face

How could these injuries have been prevented? That’s the topic of the following sections, which are organized according to the three underlying hazards: open flames, hot surfaces, and hot liquids.

Factors that increase the risk of fire-related injury and mortality among older people include decreased mobility, hearing loss, loss of sense of smell, and confusion. Open flame is an obvious fire hazard. You won’t always know that a surface you are near is hot enough to burn or that a liquid is hot enough to scald, but a person who is cognitively intact will always know that an open flame can burn them and can ignite nearby materials. So, the first exercise in creating a safer environment is to look for the use of open flame (including pilot lights) in the home. Some common sources are: gas appliances, including stoves, dryers, water heaters, and furnaces; lit candles; struck matches or lighters; fireplaces; grills; and woodstoves. We can add lit cigarettes, cigars, and pipes to this list, because they are often involved when bedding and furniture catch fire, leading to house fires.

Open flame in the kitchen is likely to be limited to the oven and cook-top. The gas cook-top presents the highest risk of open flame hazard, and the greater danger is to the person who reaches near or over a lit burner. The best preventive measure one can take is to turn off burners before removing pans from them. The second-best preventive measure is to wear short sleeves, rolled-up sleeves, or tight-fitting long sleeves. Bathrobes, nightgowns, and tops with loose sleeves are an invitation to catching fire. Also, keep anything else that can catch fire—curtains, potholders, food packaging, towels—away from the stovetop. Note that electric stoves with coil-style elements can also ignite clothing and materials. Glass electric cook-tops do not present the same open flame hazard, although they do present the hazard of a hot surface.

The very first rule to do with kitchen safety is never leave cooking foods unattended! Unattended cooking is the leading cause of house fires. Stay in the kitchen while you are frying, grilling, or broiling food. If you are simmering, baking, roasting, or boiling food, check it regularly, stay home while the food is cooking, and use a timer to remind you that you are cooking, because it’s easy to get distracted and forget about what’s on the stove or in the oven. Many older people have a reduced sense of smell, which means they may not be aware that something is burning on the stove.

Hot grease can catch fire. If you expect there to be lots of splashing of hot grease, try to cook with a pot screen or pot cover and be sure to clean the stove after food preparation. Just in case, be prepared for a stovetop fire—keep a large pot lid nearby to smother flames. In case of fire, turn the stove off and slide the cover carefully over the flame. Leave the cover in place until it is completely cooled; resist the temptation to peek under it. Never pour water on a grease fire! It will not put out the fire; it will only cause the burning oil to splash, spreading the grease fire around. Never try to carry a burning pot outside—that will only slosh and splash the hot grease and increase burning and fire risks. A common recommendation is to keep a box of baking soda nearby and be ready to pour it onto a fire, but it may take a lot of baking soda to be effective. Covering the fire with a large lid is both quick and effective.

If you experience an oven fire, turn off the oven and keep the door closed. If that doesn’t quickly control the fire, get out of the house, close the door behind you, and call 911.

Many houses have a gas water heater and clothes dryer. Remember that these gas appliances have a pilot light—an open flame. If you store or use flammable liquids like gasoline, paint thinners, glues, and so on in the same area as the gas appliance, you are asking for trouble. Vapors from these products are highly volatile, and they are heavier than air, so they travel along the floor. Flammable vapors—not the liquid—are what first explode and catch fire. You won’t see the vapors, but if they reach the pilot light, which may also be near the floor, they will ignite and explode. Store all flammable products in a different area from the gas appliance. Store gasoline in an out building or shed, not in the house or garage. All 30-, 40-, and 50-gallon gas storage-type water heaters manufactured after July 1, 2003 should comply with the American National Standard Institute’s safety standard for water heaters and be equipped with technology to prevent the burning of these dangerous vapors, but it is still best to keep flammables away from flames!

If you have to relight a pilot light, be sure to follow the directions exactly. Not waiting a sufficient time between failed attempts to light the pilot can allow gas to build up. When you next strike a match, the vapors that have not had time to dissipate will ignite. This is how people get their eyebrows singed while performing this task. If that’s all that gets burned, the person is fortunate.

Candles: Candles can be lovely and add warmth and pleasant scents to a room, but they also are an open flame hazard. Many candles have been recalled for posing a fire hazard because the candles themselves, not just their wicks, caught fire and set other items on fire. Some candle containers have shattered from the heat, posing not only a fire hazard but a laceration hazard. To completely remove risk from candles, do not have lit candles in the house; but if you wish to burn candles, do not leave the room they are in. Do not make a habit of keeping lit candles in several rooms at once.

I once was given a candle in the shape of a bird. When lit, the candle was supposed to shrink proportionally, keeping the shape of the bird. I lit the candle and set it down on a table that was covered with a tablecloth, intending to leave it there for only a few moments, then left the room. When I returned, the candle was completely on fire and so was the tablecloth beneath it! Had I gotten involved in, say, a telephone call while out of the room, my home might have burned to the ground. Lit candles should never be set directly on a flammable surface, and it’s best to put the candle out when you leave the room and relight it when you return.

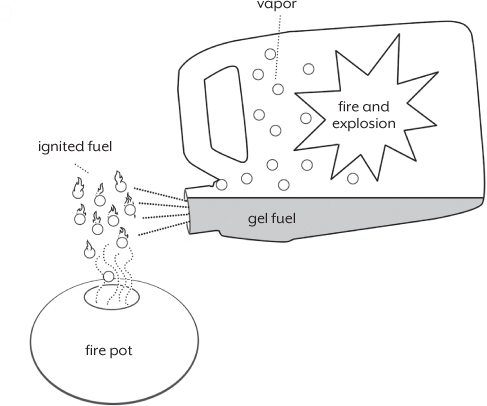

Fire pots: In 2011, fire pots that use gel fuel were identified by the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission as presenting an unreasonable risk of fire-related injury, because they can spread or spew ignited fuel onto users and surroundings. Unlike candles, these products do not have a wick to sustain the flame; the fire burns on the surface of the fuel. If these pots tip over while ignited, fuel and fire will spread very quickly. According to the commission, fire pots are

portable, decorative lighting accents marketed for indoor and outdoor use. Their purpose is decorative. They provide some illumination and are not intended to provide heat. Many are made of ceramic material and look like vases or decorative pots, but some have different features and materials, such as a partial enclosure made of glass. Firepots are also sometimes called personal fireplaces, personal fire pits, firelights, or fire bowls. These products have the following characteristics in common. They: (1) are portable; (2) are open on at least one side; (3) have an open cup, usually made of stainless steel, to hold the gel fuel; and (4) are used with alcohol-based gel fuel.

Fire pots are relatively new products. They were not prominently marketed until late 2009.

The gel fuel used with the fire pots is viscous, like syrup, and is made primarily of alcohol so that it will burn clean, without smoke or ash. The most common injury scenario involving these products was a fire and explosion when the person was in the process of, or had just finished, refueling a pot that was still lit or warm. What happens is that the flame in the fire pot, which can be hard to see under certain circumstances, ignites the fuel vapor emanating from the spout of the gel fuel container as the person is pouring. The ignited vapor follows the trail of vapor back into the fuel container, causing an explosion inside the container. The explosion propels ignited gel fuel out of the container. Figure 3.2 illustrates this series of events. The ignited fuel can splatter onto people and things. Gel fires are difficult to put out with water, and patting the fire can spread the gel, which spreads the flames instead of putting them out. Two deaths and 86 injuries related to these devices had been reported as of December 2011. Several victims were hospitalized with second- and third-degree burns to the face, chest, hands, arms, or legs.

In September 2011, the CPSC recalled all gel fuels made by nine companies (Bird Brain Inc., Bond Manufacturing, Sunjel (2 Burn), Fuel Barons, Lamplight Farms, Luminosities (Windflame), Pacific Décor, Real Flame, and Smart Solar) and admonished consumers to stop using pourable gel fuel. As of 2012, the commission was considering what would constitute appropriate regulation of fire pots.

The fire pot refueling problems bring up a common pattern of flashback type burns: when liquid fuel is added to an already lit or still hot or warm fire (as in a fire pit, BBQ grill, or trash fire) the fire can ignite the vapor trail of the fuel back toward its container, and thus toward the person holding the container. Once a fire is going, even if it is not going well, do not add liquid fuel to it. Instead, add kindling or paper—that is, products that do not emit flammable or explosive vapors.

Figure 3.2. How fuel can ignite during refueling of a gel pot

Fireplaces and woodstoves: Also warming and lovely are fireplaces and woodstoves. Of course, we do leave rooms in which these types of fires are burning. In the case of these products, you want to make sure that the fire, including sparks and embers, stays inside, where it’s supposed to be. This means having an adequate screen in front of a fireplace, and keeping the doors to the woodstove properly closed. You should also take some safety measures when trying to start a fireplace or woodstove fire. Use a commercially available fire starter log or newspaper and kindling to get a fire going, and gently add more wood over time to keep the fire burning. Do not overload the fire with wood because the flame may get larger than you can contain. Do not use a flammable liquid to get the fire going. It has been reported that people have used gasoline or some other accelerant to get a fire going. This is extremely dangerous, as an explosion and generalized fire can occur. A fireball could envelop you. Never bring gasoline into the house; always keep it stored in a shed or out building. When it comes time to get rid of fireplace or woodstove ashes, make sure they are cool to the touch before discarding them in the trash. Many house fires have been started by warm ashes left in plastic bags or containers on decks, or near other flammable materials.

Smoking remains a substantial cause of house fires. Careless smoking accounts for one-third of fire-related deaths to persons over age 70. People fall asleep while smoking, causing bedding, chairs, or rugs to catch fire; people also empty ash trays while the ashes are still warm, causing trash containers to catch fire. If you must smoke, do not light up or smoke while in bed; and before you go to bed, thoroughly check for smoldering cigarette butts or ashes on any furniture you used during the evening—chairs, sofas, end tables, coffee tables, etc. When you empty ashtrays, either dispose of the ashes into an empty metal can or let them cool overnight before you dispose of them.

There are many common products in the home that can ignite and should never be used while you are smoking or anywhere near an open flame. Know which household products are flammable. Some that we take for granted as safe and use liberally are quite flammable, for example, acetone-based nail polish remover, rubbing alcohol, certain hair sprays, petroleum-based lip balms and lotions, and certain glues. Read product labels carefully. Sometimes the information about flammability is in small, inconspicuous print. There is a federal requirement for flammable products to be labeled as such, so search the label thoroughly.

There is another situation that becomes a very high risk for fire, and that is the use of medical oxygen in the home. The oxygen in tanks used for oxygen therapy is not like the air we breathe, which is about 20 percent oxygen. Medical oxygen is concentrated—it’s 100 percent oxygen—and oxygen fuels fires. When the amount of oxygen in a room is increased, objects like furniture, clothes, bedding, plastic, and hair absorb the oxygen and therefore can catch fire at a lower temperature than they ordinarily would. Any fire that starts in the presence of extra oxygen will burn hotter and faster than usual. Even an oxygen tank that is turned off presents a risk.

Smoking while using oxygen is by far the leading culprit in house fires associated with oxygen use. These fires typically start in a bedroom or living room. There is no safe way to smoke if you use home oxygen. However, if you must smoke, there is a less dangerous way: shut off the oxygen, wait ten minutes, then go outside to smoke. This way, you will not continue to add oxygen to your clothes and hair, and when you go outside, the oxygen on you will dissipate more quickly into the larger atmosphere. When oxygen is in use at home, post signs inside and outside to remind others not to smoke.

Cooking at a gas stove while using oxygen and being around candles while using oxygen can also cause house fires, though cooking and candles were responsible for far fewer oxygen-related fires than smoking. Other products that can cause fires while oxygen is in use include, but are not limited to, electric razors (which can spark), space heaters, and hair dryers. Keep at least ten feet away from any flame or high-heat source while using oxygen.

I love a steak on the grill. I am a charcoal person, myself, but any type of grill means fuel and fire. Familiarize yourself completely with how your grill works—how to light it and how to put it out. Follow the instructions every time, without short cuts. Never use fuel other than the one approved for use; never use starter fluid other than the one approved for use. You may be tired of hearing this, but based on the injury data I have reviewed, I cannot say it too many times—never, under any circumstances, use gasoline to get a fire going. After cooking is finished, if there are ashes to discard, wait until they are cool to the touch to do so.

Do you live in an area that allows backyard burning of trash or brush? If so, for the very same reasons mentioned above, do not be tempted to use gasoline to get the fire started. (For information on the hazards of burning poison ivy and oak see Chapter 7.)

In all cases, do not pour any liquid starter or accelerant onto a fire that is even warm. The vapor on the surface of the fluid can ignite, and the fire can travel up the trail of vapor to you.

If there is a fire, knowing what to do can make the difference between surviving and dying. According to the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), from age 65 on, people are twice as likely to be killed or injured by fires compared to the population at large. According to the Consumer Product Safety Commission, those 85 or older are four times as likely. In an effort to reduce the number of fire-related deaths, the NFPA in conjunction with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) developed a program aimed at fire safety for older adults. They advise that, if you don’t live in an apartment building, you consider sleeping in a room on the ground floor; this will make escape easier. Their program also includes these tips:

✓ Make sure that smoke alarms are installed in every sleeping room and outside of sleeping areas. The majority of fatal fires occur when people are sleeping; smoke can put you into a deeper sleep rather than waking you up. If anyone in the house is deaf or has diminished hearing, consider installing a smoke alarm that uses flashing light or vibration to alert to a fire.

✓ Have an escape plan and practice it (see second paragraph below). Practice can help avoid confusion about what to do in a fire.

✓ Make sure you can exit through doors and windows. Locks should be easy to open. Windows should not be nailed or painted shut.

✓ Keep a phone and emergency numbers near your bed.

Many households have smoke alarms that are not in working order and thus will be totally useless if a fire breaks out. Make sure all alarms have working batteries in them. The Consumer Product Safety Commission recommends changing smoke alarm batteries twice a year, when you change your clocks forward and back for daylight saving time. If you are unsure whether or not you have the correct number of alarms, ask your fire department to check your home.

Having an escape route will help you get out quickly. Walk through the house and make note of every possible exit and escape route. There should be at least two ways (counting doors and windows) to get out of every room. Make sure the escape routes are not blocked by furniture or other objects. Identify an outside place to meet, a safe distance from the house, after the escape. Once you’re out, stay out! Under no circumstances should you ever go back into a burning building. If someone is missing, inform the fire department dispatcher when you call. Firefighters have the skills and equipment to perform rescues. The NFPA website, nfpa.org, has valuable fire safety information.

Some house fires are started by faulty electrical equipment or wiring. According to the Electrical Safety Foundation International, electrical fires can be started by “arc faults.” Arc faults occur when electricity is unintentionally released from home wiring, cords, or appliances because of damage or improper installation. This release of electricity can cause surrounding material to catch fire. The most common causes of arc faults are loose or improper electrical connections, such as household wiring to outlets or switches; frayed appliance or extension cords; pinched or pierced wire insulation, as could occur if a chair leg sits on top of an extension cord or if a pounded nail nips the wire insulation inside the wall; cracked wire insulation due to age, corrosion, or heat; wire insulation that has been chewed by rodents; overheated wires or cords; and damaged electrical appliances.

Have the home wiring checked every 10 years. Homes older than 40 years are more likely to catch fire electrically than those 11 to 20 years old, because old wiring may not have the capacity to safely handle new appliances and equipment. Technology continues to improve. Have an electrician examine your home. You may need more outlets, fuses, or circuit breakers; and unless you have circuit breakers from 2008 or later, you most likely need arc fault circuit interrupters (AFCIs). AFCIs replace standard circuit breakers in the electrical circuit panel. AFCIs can detect arc faults and shut down the power in milliseconds to prevent fires.

It’s best to plug each appliance directly into a wall outlet and to avoid using extension cords. To reduce the risk of electric shock, have an electrician install GFCIs (ground-fault circuit interrupters) in places where water may be present. All bathroom, kitchen counter, outdoor, and garage outlets should be equipped with GFCIs. GFCIs monitor the amount of current flowing through an electrical outlet. If there is any imbalance, the GFCI trips the circuit, cutting off electricity and preventing shock and electrocution. A GFCI is able to sense a mismatch as small as 4 milliamps, and it can react in as quickly as one-thirtieth of a second.

You can check the GFCIs in your home to make sure they are working correctly by following these steps:

1. Press the “reset” button on the outlet.

2. Plug in an ordinary night light and turn it on. It should turn on.

3. Press the “test” button on the outlet. The night light should go out.

4. Press the “reset” button again, and the light should come on.

If the light failed to go off in step 3, have an electrician check out the wiring to the outlet, because the outlet could have been improperly wired or could be damaged, and if that is the case the GFCI will not offer shock protection.

Also, make sure that you use the correct wattage bulbs in lights. Lamps and other light fixtures are labeled to tell you the maximum wattage. Using higher wattage bulbs can lead to overheating and fires.

Probably none of us has escaped the minor contact burn, the one resulting from touching a hot cookie sheet or a hot iron. Some of us probably have had more severe burns, say from contacting a hot engine muffler on a lawn mower. Very serious contact burns can result from contacting an extremely hot surface or from having prolonged contact with a hot surface, as in falling asleep on it or being trapped against it. Normally, our reflexes make us pull away from a hot surface quickly. Older people, especially those with diseases that affect peripheral nerves, like diabetes, may not have as keen a sense of touch and may not pull away as quickly. For them, contact time may be longer, and therefore the burn has the potential to be deeper and more severe.

Let’s go back into the kitchen. Hot surfaces abound when we are cooking. Not only is the stove hot, but so are pots, dishes, handles, lids, and more. Check out the potholders. Are they in good shape, or worn? Do they offer adequate heat protection? Whatever the situation, adequate heat protection between you and the hot surface ought to solve the problem of contact burns.

Microwave ovens are a special case. Because the ovens themselves stay cooler than conventional ovens, we may not be on guard against burns when using them. Be aware that some dishes and mugs can become very hot in the microwave. Sometimes, the container gets hotter than the food. I have some microwave-safe dishes that behave exactly like that, so I no longer use them in the microwave. Always do a quick check for hot surfaces and use a potholder if necessary to remove items from the microwave. Stop using dish-ware that you know becomes excessively hot.

Place hot containers like pots out of your way and on a heat-safe surface, so you don’t bump into them inadvertently while doing other tasks in the kitchen.

As for contact burn risks in other rooms, we have already talked about the open flame hazard of fireplaces and woodstoves, but these products also have very hot surfaces, as do gas fireplaces. The screens or glass doors on the fronts of these products can get very hot—as hot as 500°F. Keep your distance; if you have to move a screen or open a door to tend the fire, use a mitt or glove designed for the high temperatures these products generate. Because many young children have been burned by placing their hands on the glass of gas fireplaces, in 2011 concerned citizens filed a petition asking the Consumer Product Safety Commission to require a warning on the glass and/or a safety screen.

Space heaters are sources of hot surfaces too. It might be tempting, but do not get too close to space heaters; the heat they generate can ignite clothing. That’s why they should be placed at least three feet from any material that could ignite, like draperies, rugs, and furniture. It’s also a reason not to use them to dry clothes.

There are some additional concerns with fuel-burning space heaters (kerosene, gas, wood, coal) that do not apply to electrical heaters, because the fuel-burning ones generate carbon monoxide. If you must use such a heater indoors, take these precautions:

• Make sure the heater is installed by a professional, so that proper venting is achieved.

• Keep all the doors inside the house open, to provide good air flow.

• Turn the heater off when you go to bed.

• Install a carbon monoxide detector near where people sleep.

• Keep a fire extinguisher nearby.

Chapter 4 discusses carbon monoxide poisoning in greater detail.

Lastly, heating pads are worth noting as contact burn hazards. First-, second-, or third-degree burns can occur if someone falls asleep while using a heating pad, because one can be exposed to very high heat for an extended period. Sometimes heating pads are used in conjunction with taking a pain medication that causes drowsiness. This combination, and the fact that older people have a reduced ability to sense temperature change, can create a very dangerous situation. Keep heating pads at a moderate or low setting and use them for only short periods, not overnight.

Contact burn incidents associated with electric blankets are rare. Fires associated with electric blankets are also rare, but this tip should be followed: if you use an electric blanket, don’t tuck it in around the mattress, for this can damage the wires inside it; and don’t place additional bedding on top of it, because doing so can create excessive heat buildup, which can start a fire.

Scalds are particularly dangerous injuries, because typically more body surface is exposed to the excessive heat than in a contact burn situation. Also, trapped by clothing, the heat can stay close to the body for a longer time. Hot water has consistently been the most common source of scald burns—hot water from the tap, hot water from the stove or microwave, and hot drinks. Any liquid hotter than 120°F can scald; at 130°F, it will scald instantly. Since boiling water is 212°F, it’s easy to understand why spilled pasta water, tea water, or any other boiling water is extremely dangerous.

Fortunately, scald injuries caused by hot tap water have diminished, because hot water heaters are now shipped from the factory with the thermostat set to a medium setting. Check your water heater thermostat; it should be set to a maximum of 120°F. Water heaters also are prominently labeled to warn about scald injury. Another protective factor is that mixing valves, which control the temperature of water as delivered at the tap, are more commonly used than in the past. Be in the habit of testing the temperature of water before stepping into a shower or tub. Because of reduced skin sensitivity, an older person using a hand to test the water temperature may not get an accurate reading. An easy way to be sure of the temperature is to buy and use a thermometer designed to test the bath water for babies. It will quickly register whether the water temperature is safe. This is very important, because if the water is too hot, impaired mobility and reduced sensitivity can mean that an older person is exposed for a much longer time to water that can scald and can therefore get a much deeper burn.

Spilled hot grease is a horrible scald hazard. The very high temperature of grease (350° to 400°F) can instantly cause terrible burns. Deep fryers present the increased risk of a larger volume of hot grease. If you use a deep fryer, be sure that the cord does not dangle over the edge of the counter. Inadvertent catching or pulling on the cord can pull the entire fryer, hot contents and all, off the counter and onto you.

Never store used grease while it is still hot; never pour hot grease into a container that can melt.

Hot wax from candles can also burn skin.

Many heat-related hazards have been described in this chapter. They are presented in the following checklist of key prevention tips for minimizing the risk of injury associated with open flames, hot surfaces, and hot liquids.

✓ Clothing: Wear tops with close-fitting sleeves or roll-up the sleeves.

✓ Bathing: Appropriate bathing temperature is around 100°F; test water before getting in, and set your water heater to a maximum of 120°F.

✓ Smoking: Never smoke in bed or around medical oxygen. Dispose of cigarette, pipe, and cigar ashes only when they are cold.

✓ Candles: Stay in the same room with a lit candle; do not use flammables such as nail polish remover around candles; blow candles out when you leave the room or go to bed.

✓ Gel pots: Refuel with care and only when the product is completely cool; do not use brands of fuel that have been recalled.

✓ Fireplaces, woodstoves: Never use gasoline to start or fuel a fire. Be aware that surface temperatures of screens and glass doors can reach 500°F.

✓ Gas appliances: The pilot light is an open flame; do not store flammable liquids like paint thinners and gasoline in the same area.

✓ Electrical wiring: Have home wiring checked every ten years to be sure it is up to code and sufficient for your needs.

✓ Cooking: Do not reach over open flames. Use good potholders. Be prepared for a stovetop fire by having a pot lid close by; never throw water on a hot grease fire. Keep stovetop clean of grease. Turn pot handles inward.

✓ Microwaving: Some containers will get hot; use potholders.

✓ Outdoor grilling: Use only the fuel recommended for the equipment; follow lighting instructions exactly. Dispose of ashes from charcoal grills only when they are cold.

✓ Backyard leaf or trash burning: Never use gasoline as a fuel to start or enhance a fire.

✓ Phone numbers: Keep emergency phone numbers handy and near the phone; program them into your phone.

✓ Exit strategy: Plan how to get out in case of a fire; practice the drill.

✓ Smoke and CO detectors: Install and keep in working order smoke and carbon monoxide detectors (in almost two-thirds of home fire deaths for 2005–2009, there was either no smoke alarm in the house or the smoke alarm was not working).

Our bodies have their own thermoregulatory system. They are naturally designed to regulate our core temperature by keeping a balance between the heat we generate (when we burn calories) and the heat we lose (through our skin). When we are cold (losing too much heat), the body shivers to generate heat; when we are hot (not losing enough heat) the body perspires to get rid of excess heat. We also intentionally control body temperature by the clothing we wear, dressing more warmly in cold seasons and wearing lighter-weight clothing during warm seasons, and by adjusting the thermostat in our home for comfort. Average normal body temperature is 98.6°F.

Exposure for long periods to intense heat or cold can cause the body to lose its ability to respond to temperature change effectively. When the body temperature drops too far below (hypothermia) or goes too far above (hyperthermia) normal body temperature, we get into trouble. Both hypothermia and hyperthermia are dangerous. Hypothermia is defined as a body temperature below 96°F. There is no set temperature that defines hyperthermia, but concern grows as the body temperature rises above 98.6°F. A core body temperature of around 104° signals danger.

Older people are hospitalized and die from temperature-related illness at a higher rate than the general population. Some underlying health issues that can increase the risk in older people include poor circulation; inefficient sweat glands; skin changes related to aging; any illness that causes fever; heart, lung, and kidney diseases; high blood pressure; salt-restricted diets; inability to perspire related to taking certain medications like diuretics, sedatives, and heart and blood pressure medicines; being substantially overweight or underweight; and drinking alcoholic beverages.

The temperature outside or inside a building does not have to hit 100°F for you to be at risk for a heat-related illness. Heat exhaustion—a warning that the body is having difficulty keeping cool—and heat stroke—a medical emergency in which the body has dangerously exceeded healthy temperature—are the most common forms of hyperthermia. Here are some signs that mean a person may need relief. With heat exhaustion, the person may be thirsty, giddy, weak, uncoordinated, nauseated, and sweating profusely. The skin can be cold and clammy. If heat exhaustion is not treated, it can progress to heat stroke. Signs of heat stroke include confusion, combativeness, bizarre behavior, faintness, staggering, strong, rapid pulse, flushed skin, lack of sweating, delirium, and coma. Heat stroke is extremely dangerous and requires immediate medical attention.

Other heat-related symptoms include heat cramps, which involve a painful tightening of the muscles in your stomach area, arms, or legs. Heat cramps can occur after or during hard work or exercise. They are a signal that your body is getting too hot, even though your body temperature and pulse usually stay normal. The skin may feel moist and cool. Another symptom is heat edema, a swelling in the ankles and feet when you get hot. Finally, there is heat syncope, a sudden dizziness that may come on when you are active in the heat. If you take a medication known as a beta blocker or if you are not accustomed to hot weather, you are more likely to feel faint when in the heat. Pay attention to these symptoms.

Preventing heat-related illness is always better than treating it. Here are some steps you can take to help reduce the risk:

✓ Pay attention to the weather reports. You are more at risk as the temperature or humidity rises or when an air pollution alert is in effect.

✓ Dress for the weather. Natural fabrics (like cotton) tend to be cooler than synthetics (like polyester); lighter colors keep you cooler because they reflect the sun.

✓ During warmer months, especially if there is a heat wave, make sure there is enough air flow to keep the room temperature comfortable. Open windows can offer a cross-breeze, but if the only air coming in is very hot, you may need a fan or air conditioning (either central or window units) to help relieve the heat. At the beginning of the warm season, make sure these kinds of aids are available and working properly. If you do not have any of them, contact a local public health agency or council on aging to find out whether they have loaner programs.

✓ Keep shades and curtains drawn during the hottest parts of the day.

✓ If the home can’t get cool enough to be comfortable, go someplace that is air conditioned.

✓ Drink plenty of liquids like water, fruit juices, and vegetable juices. Drink even if you are not thirsty. Avoid beverages containing caffeine and alcoholic drinks, because they help your body to lose fluids. If your doctor has told you to limit your fluid intake, ask what you should do when it is very hot. Avoid hot, heavy meals.

✓ Minimize or forego exercise or activities that can exert you when it is hot.

If someone is suffering a heat-related illness, here are some recommendations for what to do:

For heat exhaustion: Rest in a cool place, sponge off with cool water, and drink plenty of fluids. Get medical care if you don’t feel better soon.

For heat stroke: Call 911. You need to get medical help right away.

For heat edema: Put your legs up. If that doesn’t provide relief fairly quickly, check with your doctor.

For heat syncope: Put your legs up and rest in a cool place.

During colder months, make sure that the home is not kept at an unusually high temperature and that no one is overdressing so much that they could develop hyperthermia. While one is less likely to be on alert for hyperthermia in colder weather, lowered sensitivity to body temperature can cause older persons to keep the house too warm or put on too many layers of clothes and then not realize that they are too hot.

Hypothermia is defined as a body temperature below 96°F. Hypothermia is dangerous because it can cause an irregular heartbeat, leading to heart failure and death. Signs of hypothermia include excessive shivering, confusion or sleepiness, slow or slurred speech, shallow breathing, weak pulse, low blood pressure, stiff arms or legs, poor control over body movements, and slow reactions. Because some of these symptoms can be related to other problems, just look for the “umbles”—stumbles, mumbles, fumbles, and grumbles—which show that the cold is affecting how well the person’s muscles and nerves work. Observe the environment. Are you seeing these symptoms while the person is in a cold environment? Take the person’s temperature. If it is below 95°, the situation is an emergency and the person needs medical attention.

If medical care is not immediately available, you can take these measures to begin warming the person:

• Get the person into a warm room or shelter.

• If the person is wearing any wet clothing, remove it and replace with dry clothing or covering.

• Warm the center of the body first—chest, neck, head, and groin—using an electric blanket, if available, set on low. Or use skin-to-skin contact under loose, dry layers of blankets, clothing, towels, or sheets. It seems a natural instinct, but don’t rub the person’s arms and legs—that can make things worse.

• Warm beverages can help increase the body temperature, but do not give alcoholic beverages. Do not try to give beverages to an unconscious person.

• After body temperature has increased, keep the person dry and wrapped in a warm blanket, including the head and neck.

• Get medical attention as soon as possible.

A person with severe hypothermia may be unconscious and may not seem to have a pulse or to be breathing. In this case, handle the victim gently, and get emergency assistance immediately. Even if the victim appears dead, CPR should be administered. CPR should continue while the victim is being warmed, until the victim responds or medical aid becomes available. In some cases, hypothermia victims who appear to be dead can be successfully resuscitated. If body temperature has not dropped below 90°F, chances for total recovery are good.

Preventing cold-related illness is always better than having to treat it. Here are some things you can do to help reduce the risk of hypothermia:

✓ Regulate the temperature of the home environment. How good is the home’s insulation; is it intact? How old is the furnace? Is the furnace working properly? Does it need to be replaced? How well do the windows fit the window openings? Is too much air escaping or coming in? Do the windows need to be caulked or replaced? Are there storm windows? Is weather-stripping needed on doors? If heating the whole house is too expensive, could some rooms be closed off and not heated? The answers to these questions may not be obvious. You might benefit from a home energy evaluation, which can be performed by a local gas, oil, or electricity provider.

✓ Maintain good nutrition to keep the body’s metabolism active. Balanced meals are key. How well-stocked are the fridge and pantry? Are there simple, easy-to-prepare meals at hand, like cans of soups, instant oatmeal or other hot cereal, and good-quality frozen dinners? Keep in mind that alcohol lowers the body’s ability to retain heat.

✓ How about wardrobe: Are there enough cold weather clothes? Are there enough blankets and throws and are they within arm’s reach of the furniture where they will be needed? Older persons should wear several layers of loose clothing. The layers will trap warm air between them.

✓ Manage diseases such as diabetes and thyroid dysfunction that affect blood flow or hormone levels. Are the medications being taken for such conditions doing their job? If not, they may need adjustment.

✓ Winter storms can knock out power, leaving the home too cold to be comfortable. Accessory heating systems, like space heaters may be necessary. If a generator is used, be sure to use it properly—it must be kept outside the house, to prevent carbon monoxide poisoning. Review the generator information in Chapter 4.

✓ Sometimes, a person’s financial situation affects the risk for hypothermia. Most utility companies offer the option to spread out the cost of heating or cooling a home over the entire year; in some cases there is special relief for older people who need it.

Exposure to cold can also cause frostbite, an injury that involves freezing of the tissue. Sometimes frostbite and hypothermia coexist. The extremities—the fingers, toes, nose, and ears—get cold first, as the body channels its blood supply inward to protect the major organs from the cold. These are the body parts most susceptible to frostbite. Depending on the degree of cold, the length of exposure, and the layers of skin affected, injury can be permanent. The risk of frostbite is increased in people who have slowed blood circulation and among people who are not dressed properly for cold temperatures.

Any of the following signs may indicate frostbite: a white or grayish-yellow skin area, skin that feels unusually firm or waxy, or numbness. Because the frozen tissue becomes numb, a victim is often unaware of frostbite until someone else points it out. If you think a person has frostbite, get medical care for the person. As long as there is no sign of hypothermia, you can follow these steps until medical help arrives:

• Get the person into a warm room as soon as possible.

• Unless absolutely necessary, do not walk on frostbitten feet or toes—this increases the damage.

• Immerse the affected area in warm—not hot—water (the temperature should be comfortable when touched by unaffected parts of the body), or warm the affected area using body heat, for example, by placing frostbitten fingers in an armpit.

• Do not rub the frostbitten area with snow or massage it at all. This can cause more damage.

• Do not use a heating pad, heat lamp, or the heat of a stove, fireplace, or radiator for warming, because affected areas are numb and so can easily be burned.

Both hypothermia and hyperthermia are serious. If you are concerned about or responsible for an older person who may be at risk for being dangerously cold or hot, actually looking in on them will give you a more reliable assessment of their condition than a brief chat on the phone.