The backyard, the workshop, and the garage all are extensions of the home, and they harbor some of the same hazards that are found inside the home. They also present some special hazards.

The backyard can be a peaceful place, with flower and vegetable gardens, trees and bushes, perhaps even a pool, pond, or stream. If you tend your own yard, chances are you water, mow, trim, plant, and so on. Gardening is a very popular and healthy pastime. Overall, it is a very safe hobby, too, but there are a few gardening hazards to avoid. In Chapter 2, I discuss fall hazards in detail. Although there are fewer risks for falling in the backyard than inside the house, they do exist. Here are some reported incidents:

An 89-year-old was raking leaves in his backyard when he tripped and fell, suffering a concussion.

A 71-year-old tripped over some rusty garden tools and lacerated his leg.

A 77-year-old fell when she pushed on a shovel as she was digging up a rose bush and fractured her arm.

A 75-year-old was weed-whacking and fell down an embankment.

A tripping hazard that sent about 4,000 people ages 65 and older to emergency rooms in 2010 was the common garden hose—a staple of gardens everywhere. What makes tripping on the hose potentially so dangerous is what the person might fall onto. The many possibilities include fences, raised garden beds, landscape timbers, railings, stone walls, curbs, and more. For example, an 83-year-old tripped over a hose in the garden and fell, striking his head on a brick, and a 93-year-old tripped on a hose and fell striking his head on a concrete flower box.

I am not going to suggest that you alter the terrain of your backyard, unless you feel it is particularly dangerous, but you can address the hose itself. Do you have it on a reel—so that it can be retracted and kept well out of the way? Help reduce the risk of tripping on the hose by rolling out only the length of hose you need and not much more and rewinding the hose after every use.

Mowing too is a reasonably safe endeavor, but we have all heard about people being injured from mowing. Mandatory federal regulations long ago addressed the once common hazard of a power mower’s rotating blade lacerating or amputating fingers when people reached into the chute to clear accumulated grass clippings and inadvertently reached into the path of the blade. On today’s power mowers, blades stop rotating when the user releases his grip on the handles of walk-behind mowers, or gets up off the seat of a ride-on mower. Many people understandably find these safety features irritating, but do not bypass them, because they really do substantially increase your safety.

There remains the hazard of tip-over, especially with ride-on mowers and lawn tractors. This hazard might not seem obvious. It can be hard to imagine such a heavy piece of machinery overturning. Tip-over can occur when the operator attempts to traverse land that is on an incline. The mower is thrown off its center of gravity and overturns. Tip-over can result in severe blunt trauma or compression asphyxia, as the rider usually gets trapped beneath the machine. In fact, 22 older people died in 2009 because of tractor tip-over. Review the user manual that comes with this equipment. The instructions will help you assess the incline of your yard and will tell you how to safely navigate the hills and valleys there. Correct technique is required even on the small inclines and dips.

Gravity is an ever-present force! Here’s another example of how inclines can get the better of you: a 76-year-old was pushing a lawn mower down a hill when it gained speed, and as she chased it—or as it pulled her down the hill—she fell against a fence.

Running over bystanders, particularly young children, is another ride-on mower hazard. Children standing or playing in the yard while a ride-on mower is in use may not be visible to the operator, especially when they are behind him. It is such a tragedy to the family when a child dies this way. Never allow a child to be in the yard while the yard is being mowed; never invite a child to sit with you on a mower. These are not safe things to do. Even adult bystanders should stay several feet away from a mower to avoid being struck by thrown objects, like stones.

The hazards associated with gasoline storage and misuse are discussed in Chapter 3. Here I will talk about the hazard of gasoline while it is being used, not stored. Any gasoline-fueled equipment presents a risk of fire. If you spill gas while you are pouring it into the equipment’s reservoir, wait a few minutes for the gas to evaporate before starting the engine, because a spark from the starter could ignite the gas vapors. When you need to refuel, wait a few minutes for the engine to cool, because spilling gas onto a hot engine could ignite gas vapors. And don’t smoke or light up!

Ladders present the opportunity for injury outside as well as inside the house. If you are thinking of accessing those tree branches that need to be trimmed by using a ladder, you might want to reconsider and leave the job to a professional. Performing these kinds of tasks on a ladder is a good way to lose your balance. If you are using a power tool, like a small chain saw, instead of a manual tool, the risk for losing your balance increases. In addition, incorrect set-up of an extension ladder is very common. People tend to position the base (foot) of the ladder too far away from the vertical surface, which can result in the ladder “walking down the wall.” On the other hand, if the foot of the ladder is too close to the vertical surface, leaning backwards while on the ladder can cause the ladder to fall away from the wall or tree or whatever it’s leaning against, taking you with it. See Figure 7.1A for an illustration of the correct angle for setting up a ladder. Your ladder may have a label on the side showing an “L.” This is to help you position the ladder correctly. If you orient the ladder so that the horizontal leg of the “L” is parallel to the ground, it will be at the correct angle. If there is no “L” on the ladder, the rule to follow is this: Set up the ladder where you will be using it. Imagine a triangle drawn from the foot of the ladder to the point where the ladder is resting on something above and from that point straight down to the ground, then along the ground back to the ladder foot (see Figure 7.1A). That last line, back to the foot, should be one-fourth the length of the first line, from the foot up to the point of support at the top. You may wish to tape a copy of Figure 7.1A to the side of your ladder.

Another easier way to correctly set up an extension ladder is shown in Figure 7.1B. Rest the ladder against the vertical surface. Stand with your feet touching the base of the ladder and extend your arms. Adjust the ladder position until the palms of your hands rest on the ladder rung while your feet are touching the base.

Even correctly positioned ladders can topple if a person overreaches. It is always safer to climb down and reposition the ladder than to reach too far to a side. One more thing before we leave ladders: if you are standing on a metal one or using a metal tool, be sure to be nowhere near a live electrical wire—look up as well as around before raising the ladder! Electrocution is a real and potentially fatal hazard.

Much of backyard power equipment is noisy—noisy enough to cause hearing damage. Wear ear protection. While we are speaking of protecting a sense, also think about your eyes. Wear eye protection to avoid being struck by thrown rocks or twigs while you are weed-whacking, mowing, leaf blowing, and generally using any power equipment to take care of the yard. If you chop wood, remember that striking tools, like mauls, axes, and so on, also can throw chips, off the tool itself or off the wood you are chopping. Wear eye protection for this task, too.

Do you want to power wash the deck or the siding? There are just a few things to be aware of. Most important is that water under that much pressure will cut through skin. Wear hard-toed shoes for this task; never wear sandals or shoes that leave your bare feet exposed. Follow the product directions to avoid an out-of-control wand. Once again, put on protective ear plugs and eyewear!

If you live in a place where snow is part of your landscape, perhaps you use a snow blower. In a recent study, older adults had a higher proportion of emergency room visits for injuries associated with snow blowers than younger people did. Most of the injuries to older people were finger or hand amputations associated with reaching into the discharge chute. The most common designs of snow blowers include a front auger that picks up snow and an internal impeller that discharges the snow from the chute. Both the auger and the impeller are rotating parts, and they rotate at high speed. Users who are not aware of the impeller blade and its location increase their risk of injury. If you use your hands to clear the discharge chute of wet snow you will be close to the impeller blades. Turn the equipment off and wait until the blades stop coasting before reaching into the chute. Better yet, use the cleaning tool that comes with snow blowers to clear the chute. It’s a shovel-shaped device attached to the machine and is standard on newer models.

Figure 7.1. (A) Mathematics of correct ladder set up and (B) easy method for correct ladder set up

It’s always good to know which plants might be poisonous. If you’ve ever had poison ivy, you know it is no fun. Poison ivy and poison oak are fairly common plants. Poison ivy exists everywhere in the continental United States except California; poison oak is primarily in the Southeast and on the West Coast. Poison sumac, another skin irritant, is found along the Mississippi River and boggy areas of the Southeast. Drawings of these plants are shown in Figure 7.2. As you look at the images of poison ivy and poison oak, remember this old saying, “Leaves of three, let it be.” That guidance will help you identify these plants. As for poison sumac, look for stems that contain seven to thirteen leaves arranged in pairs growing directly opposite each other.

These poisonous plants are most often a problem when a person’s skin contacts the sap oil that is released when the leaf or other plant parts, including roots, are bruised, damaged, or burned. The result is an itchy red rash with bumps or blisters. Most people will develop a rash after exposure to an amount of sap oil the size of a grain of salt. Depending upon where on the body exposure occurs and how broadly it is spread, the rash may need medical attention.

Figure 7.2. Avoid contact with these plants.

If you have been exposed to smoke from burning these plants, you should seek immediate medical attention, because the inhaled allergens will cause throat and lung irritation. For most minor skin exposures, an over-the-counter topical medication like calamine lotion or hydrocortisone cream may suffice. An antihistamine like Benadryl will help relieve the itching.

If you know you have any of these poison plants in your yard, avoid contact by wearing long sleeves, long pants, and gloves when working around them. When you are finished, wash those clothes separately—not with other clothing—in hot water, and any tools you used directly with the plants should be washed with rubbing alcohol or soap and lots of water. Wash your hands with dishwashing soap, because it is a degreaser, and you want to get rid of any sap oil on your skin.

Although ticks are more likely to be found in the woods or high grass than in your backyard, they are worth mentioning because of the potential for contracting Lyme disease. Lyme disease gets its name from the town of Old Lyme, Connecticut, where the first case was identified in the United States in 1975. Lyme disease is the most commonly reported tick-borne disease in the United States. It is passed to humans by the bite of black-legged ticks, also known as deer ticks in the eastern United States, and western black-legged ticks that are infected with the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi. Deer ticks prefer to feed on the blood of white-tailed deer, but humans who brush up against leaves or grass where there are ticks can become unknowing hosts.

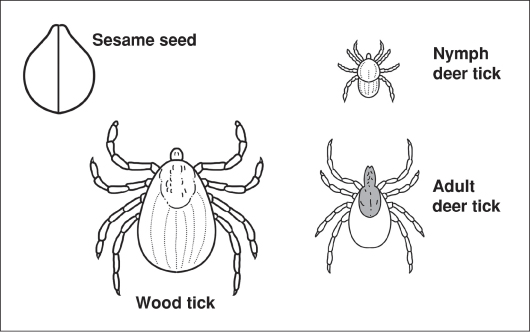

Black-legged ticks can be so small that they are almost impossible to see; many people with Lyme disease never even saw a tick on their body. So, if you are in a woodsy area or anywhere that attracts wildlife, especially deer, wear light-colored long pants, a long-sleeved shirt, and socks. This will help protect you and make ticks easier to spot. By comparison with black-legged ticks, wood ticks—which do not transmit Lyme disease—are much larger (see Figure 7.3). Wood ticks typically feed on the blood of dogs and cats, but they, too, will attach to a human. They are readily visible, however, especially if engorged with blood, and are thus more easily noticed and removed.

Not all black-legged ticks are infected with the bacterium and most people who are bitten by a tick do not get Lyme disease. The Lyme disease bacterium normally lives in mice, squirrels, and other small mammals. When a tick bites an infected animal, the tick can become infected with the bacterium. When that infected tick then bites a person, the bacterium can infect that person. In 2010, more than 22,500 confirmed and 7,500 probable cases of Lyme disease were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. These statistics include persons who were exposed in the course of their jobs. The highest numbers of confirmed Lyme disease cases were reported from Maine, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Delaware, Virginia, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. If diagnosed and treated early with antibiotics, Lyme disease is almost always readily cured.

There are three stages of Lyme disease. Stage 1 is called early localized Lyme disease. The infection is not yet widespread in the body. There may be a “bull’s eye” rash, a flat or slightly raised red spot at the site of the tick bite. Often there is a clear area in the center. It can be quite large and expanding in size. Symptoms can include body-wide itching, chills, fever, a general ill feeling, headache, light-headedness or fainting, muscle pain, or stiff neck.

Stage 2 is called early disseminated Lyme disease. The bacteria have begun to spread throughout the body. Stage 3 is called late disseminated Lyme disease. The bacteria have spread throughout the body. In most cases, a tick must be attached to your body for 24 to 36 hours to spread the bacteria to your blood.

If Lyme disease is not promptly treated, it can spread to the brain, heart, and joints. If you think you may have been moving around in areas where ticks abound, after you get home, remove your clothes and thoroughly inspect all skin surface areas, including between your fingers and toes and your scalp. Shower soon after coming indoors, to wash off any unseen ticks. Always check your pets for ticks, too. According to the American Lyme Disease Foundation, if you discover a deer tick attached to your skin but it has not yet become engorged, it has probably not been there long enough to transmit disease. Just in case, however, be alert for any symptoms (a red rash, especially surrounding the tick bite, flu-like symptoms, or joint pains) in the first month following any deer tick bite. If a rash or other early symptoms develop, see a physician immediately.

Figure 7.3. Comparative sizes of wood ticks and deer ticks; deer ticks spread Lyme disease

The American Lyme Disease Foundation recommends following these steps to remove a tick (http://www.aldf.com/lyme.shtml #removal):

1. Using a pair of fine-pointed, precision tweezers (with smooth, not rasped tips), grasp the tick by the head or mouthparts right where they enter the skin. DO NOT grasp the tick by the body.

2. Without jerking, pull firmly and steadily directly outward. DO NOT twist the tick out or apply petroleum jelly, a hot match, alcohol, or any other irritant to the tick in an attempt to get it to back out.

3. Place the tick in a vial or small jar of alcohol to kill it.

4. Clean the bite wound with disinfectant, such as alcohol or peroxide.

Another extension of the home environment is the workshop or garage. If your hobby involves woodworking, you already know that woodworking tools have inherent hazards, like fast moving blades, sharp edges, and sharp points—all of which are necessary for the tool to do its job well. Two common blade-related injuries often associated with table saws, circular saws, and radial arm saws, are kickback and inadvertent contact with the blade. Both can result in very severe injury or even death. Kickback can cause internal injuries, as well as external lacerations. Correct feeding of materials into the blade and correct body positioning can reduce the risk of kickback type injuries. The use of guards on the saw can reduce the risk of inadvertent contact with the blade. And, of course, you will be wearing protection for your eyes and ears.

In 2010, about 10,000 people older than 65 were treated in hospital emergency departments for injuries sustained while operating table or bench saws. Most of the injuries were hand or finger lacerations or amputations. If your equipment has a guard (and it should), I encourage you to use the guard in its proper position. The Consumer Product Safety Commission is considering (in 2013) whether a new mandatory performance safety standard is needed to address an unreasonable risk of injury associated with blade contact from table saws.

Much has been done to improve the safety of art materials since the passage of the Labeling of Hazardous Art Materials Act (LHAMA) in 1988. Even so, arts and crafts materials can pose hazards. The act requires that art materials containing chemicals that can cause chronic health effects with long-term exposure be labeled to inform the user of those potential long-term effects. Examples are chemicals that are potentially carcinogenic (cancer-causing), neurotoxic (toxic to the nervous system), or teratogenic (causing birth defects). Nontoxic products are labeled “Conforms with ASTM D-4263.” Read the labels on paint tubes, glues, pastels, and other art materials to find out if they present any dangers from long-term use.

Older people are also a growing proportion of all-terrain vehicle (ATV) operators. A review of 6,308 ATV-related traumas reported to the National Trauma Data Bank during the period 1989–2003 showed that being older than 60 years was associated with significantly longer length of hospital stay, greater number of intensive care unit days, and increased risk of dying. About 10 percent of consumer product–related deaths in the age group 65 and older reported in 2009 involved ATVs. These vehicles can be powerful and difficult to control, and they require good balance, which many older persons no longer have. Rollover incidents are relatively common. If, despite the hazards, you decide you want to operate an ATV, get training from a licensed dealer, and always wear a helmet. Know the terrain you will be negotiating, and respect the vehicle’s power.

The importance of wearing a helmet is underscored by a Consumer Product Safety Commission study reporting that Baby Boomers who died from head injuries related to bicycle accidents were twice as likely to die from their injury as children who rode bikes. We correctly take action to protect the young from head injury, but their grandparents need head protection too.