When an older person falls, there is, unfortunately, a good chance that the person’s quality of life will be severely diminished. Whether as the result of an injury suffered in the fall, an increased fear of falling, or reduced confidence in the ability to perform daily tasks, many older people lose some or even most of their independence after a fall. Sometimes people are lucky and suffer no injury or only a minor injury in a fall, but often enough falls result in broken bones and hospitalizations. And some falls cause fatal injuries.

These figures will give you an idea of the magnitude of the problem: In 2010 in the United States, more than half a million people aged 65 to 74 years were injured in a fall and about a million and a half people 75 or older were injured as a result of a fall. In 2009, nearly three thousand people aged 65 to 74 years and more than seventeen thousand people aged 75 or older died as a result of a fall.

No matter what sources you consult, they all draw the same conclusion: falls are the primary injury mechanism for the aging population. These sources also say that if a person falls once, the likelihood of a second fall is nearly doubled and that the risk of being seriously injured in a fall increases with age. This doesn’t mean that falls are a normal part of aging and that they are inevitable. To the contrary, risk factors for falling vary among individuals. For this reason, a person’s individual risks can be identified, and then appropriate strategies to address those particular risks can be put in place.

The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) collects data on consumer product related injuries. The CPSC defines consumer products as those used in and around the home, in schools, and in recreation. More than half (59%) of consumer product–related emergency room visits for adults 65 to 74 years of age involve falls; 77 percent of consumer product–related emergency room visits for adults aged 75 or older involve falls. Typical fall scenarios include falling down stairs; falling out of bed; tripping over rugs, cords, or other obstacles on the floor; and falling off ladders and step stools.

Here are some other facts about falls:

• More falls happen in the home than anywhere else.

• Women are more likely to fall, but men are more likely to die from a fall.

• After a fall, some people develop a fear of falling again. This fear can cause people to limit their activities, leading to reduced mobility and physical fitness, and thus, ironically, increasing their risk of falling.

Knowing that falls are a common source of injury is not as helpful as knowing why people fall. Knowing why allows us to do something about it. There is no single or simple way to explain why people fall, however. Usually, there are multiple reasons for a fall. Remember that we humans are complicated and complex, and we interact with numerous environments. During most human activities, a lot is going on at the same time, and there are many factors that affect the chances of falling—what safety experts call fall risk factors.

Fall risk factors can be grouped into two broad categories: internal (or intrinsic) factors—those within the person; and external (or extrinsic) factors—those outside the person. Figures 2.1 and 2.2 identify some internal and external fall risk factors. Separating risk factors into these two categories is a very good way to understand which factors we have control over and can change and which factors we don’t have good control over and may find hard to change.

It may seem that factors inside ourselves would be easier to address and modify than those outside ourselves. However, ironically, internal risk factors are more difficult to change than external ones, and unfortunately the intrinsic factors may have more significant impact on risk of falling than extrinsic ones do. According to current research, the strongest risk factors for falls include: previous falls; strength, gait, and balance impairments; and medications—all intrinsic factors. Some additional intrinsic fall risk factors are: the presence of illness or disease, nutritional status, degradation in the function of the senses (especially vision and hearing), foot conditions, fear of falling, and mental decline. Obviously, intrinsic factors vary from individual to individual. So, the first question to ask is, “What are the specific fall risk factors intrinsic to this person?” and the second question is, “How can these intrinsic fall risk factors be reduced?”

Figure 2.1. Internal fall risk factors

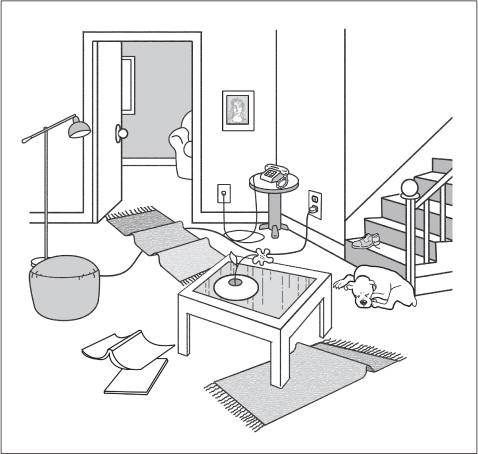

Figure 2.2. External fall risk factors

In the following sections, I discuss all the intrinsic factors that the published scientific literature supports as being contributing factors to falls. Some factors may jump right off the page as being very relevant to you; others may not seem relevant at all.

Since having fallen once is a significant risk factor for falling again, preventing that first fall is doubly important. Here are the key means of counteracting internal fall risk factors when trying to prevent a first fall:

✓ Keep physically strong.

✓ Eat well to ensure good nutrition.

✓ Know what medicines you are taking and be aware of side effects.

✓ Have your vision and hearing tested regularly.

✓ Have foot problems checked by a podiatrist.

Let’s take these prevention strategies one at a time and consider how they relate to falls and falls prevention.

A person’s overall physical condition is a contributing factor in falls. As noted in Chapter 1, most people lose muscle and bone mass as they age, which means they lose physical strength, too. Strength is needed to move your body, like getting up from a chair, and to maintain balance. An important consequence of decreased strength is that people may change their activity level, from active, to moderately active, to sedentary. Reducing activity creates a circle of decline: the less active people are, the more strength they lose, and then in turn they become even less active. Decreased physical activity translates to decreased muscle mass, strength, and power. So, staying strong is crucial to preventing falls. (It has countless other benefits, as well.)

Research has shown that physical strength and balance can be improved through exercise. When improved and maintained, strength and balance become fall protective factors. Many fall prevention programs include exercise (strength training, balance, stretching, and so on) to help with physical fitness. The 2011 American Geriatric Society Guidelines recommend that all fall prevention programs include an exercise component. The greatest positive effects of exercise on fall rates were seen in programs that included a combination of a high total dose of exercise and challenging balance exercises. Interestingly, these programs did not include walking, probably because walking itself can be a risk for falling, as you will read later on in this chapter. (This does not mean that if you walk for exercise and are comfortable doing so you should stop.) Some programs involve tai chi or yoga, including yoga done while seated in a chair. These practices help improve balance and strength, and for some offer the added benefit of feeling calm and grounded. A 2012 study added another dimension to the fall prevention role of exercise. The findings of the study suggest that exercise reduces the chance of falls because it improves cognitive function, especially so-called executive functions like planning, working memory, attention, problem solving, verbal reasoning, appropriate inhibition, mental flexibility, and multitasking.

Decide with your doctor what kinds of exercises are appropriate for you, then choose a program you think you might enjoy. For many people, exercising on their own is neither fun nor motivational. Such persons should look for exercise programs offered at community centers, gyms, councils on aging, hospitals, and so on. You may be surprised at the variety of classes available. With a class, there is the added benefit of social interactions, which help keep a person mentally healthy. Some people prefer not to exercise with a group. They may choose to exercise at a gym but not in a class; personal trainers are usually available for a fee, or they may offer a complimentary, one-time consultation to sketch out a strength and balance regimen for an individual. Many people make a pact with a friend to exercise together.

A new exercise approach is described as exergaming—a combination of video gaming and exercise. Could this combination be for you? Apparently, the enjoyable and challenging nature of video game–based exercising motivates people to exercise. A study from the Netherlands showed that persons who engaged in exer-gaming experienced improved balance as well as improved task performance.

Because more than half of the falls that occur while a person is walking involve tripping, gait and balance are critical intrinsic factors in avoiding falling. (The obstacle that one trips on is an extrinsic risk factor.) Gait is simply the way we walk—how our feet touch and then lift off the floor. Balance is control over one’s center of gravity. Gait and balance, although separate entities, are often intertwined. For example, changes in bone structure that accompany osteoporosis often result in curvature of the spine. When the spine is curved, the head tends to be positioned forward relative to the rest of the body. Having the head positioned more forward instead of in line with the body alters the person’s center of gravity and can throw the person off balance, which in turn can lead to a change in gait. The head is pretty heavy! Imagine carrying a bowling ball out in front of you for any length of time, and you can appreciate that you would have to change your gait to compensate for the resulting change in your center of gravity. Thus, a change in gait can often be an important symptom that a person’s health status has changed.

We may take balance for granted, but it is very complex. The upright body is basically unstable and relies on perceptions of its surroundings to maintain balance. Those perceptions include what we see around us, what the vestibular system in our inner ear tells us about where we are in space, and what our feet tell us about the kind of surface beneath us. All of that information has to be processed cognitively so that the brain can tell the body how to maintain balance. And finally, the muscles have to be able to move the body to make the necessary adjustments to stay balanced.

Think of walking as a continuous process of losing and regaining balance. At some point in every gait cycle, one foot pushes off the ground and moves through the air before it comes down again, usually heel first. While that foot was in the air, the weight was on the other foot. Most falls occur at the moment when the weight is being transferred from one foot to the other—that is, when the toes of the back foot and the heel of the front foot are in contact with the ground.

The published scientific literature confirms that gait changes are common among older persons and that they contribute to the risk of tripping and falling. Here are some examples of abnormal types of gaits: cautious, weak, fear-of-falling, freezing (feet feel glued to the ground but the body moves forward), and marche à petit pas (taking small steps). The most significant and observable age-related change in gait is slowed walking speed, primarily related to a shorter stride length. Other types of age-related gait change are a more flat-footed contact with the ground, a toed-out stance, or not lifting the feet as high off the ground while walking. The underlying causes of gait changes are many; they include, but are not limited to, a painful or disfiguring foot condition, a fear of falling, a prior stroke, loss of strength, neurological changes, and reduced range of motion in the ankle joint.

To assess a person’s gait, observe how he walks; to assess your own gait, have someone watch while you walk. These are the questions the observer should ask:

• Does he take full steps, placing the heel down first?

• Does he shuffle?

• Does he walk slowly or quickly?

• Does he have good balance?

I can recall how my mother’s gait changed from what I would consider a normal gait to a shuffle, her feet barely lifting off the floor. Her gait change was related to her dementia. With this change, her interaction with carpeting and thresholds was suddenly different and more hazardous. A gait change can make a person more prone to tripping; being aware of such a change can motivate you to make environmental (extrinsic) changes to reduce the risk of falls.

A factor related to strength—and therefore to risk of falling—is nutrition. While we need fewer calories per day as we age, we still need good nutrition. There are six categories of nutrients that the body needs to acquire from food: protein, carbohydrates, fat, fibers, vitamins and minerals, and water. Do not underestimate the need for water! Water is necessary for metabolism, excretion, and assimilation of nutrients. Dehydration is dangerous. It can make a person dizzy or disoriented and can cause muscle cramping. General guidelines for good nutrition tell us to eat a variety of foods, including plenty of vegetables, fruits, and whole grain products; to eat lean meats, poultry, fish, beans, and low-fat dairy products; and to keep salt, sugar, alcohol, and fat intake modest.

Vitamin D supplements are often recommended for older persons as a way to address bone loss. Among its several benefits, vitamin D seems to play a role in fall prevention, with the strongest benefit being for older men. Studies have shown that a low vitamin D level in the blood was associated with disturbed gait control. Other studies have shown that vitamin D supplements are effective only in people who are deficient in vitamin D to begin with.

Another nutritional component associated with fall prevention is folate. One study which investigated vitamin D, folate, and vitamin B12 showed that serum (blood) levels of folate were significantly lower in people who were prone to falling.

Before you run out and buy dietary supplements of these or any other compounds, remember that taking supplements cannot replace a balanced diet, and taking supplements can be dangerous. Pills usually concentrate the amount of a substance. As an example, vitamin E supplements contain anywhere from 100 to 1,000 IU (international units) per pill. Consider that you would have to eat four cups of almonds (rich in vitamin E) to get 100 IU of vitamin E. Also consider that the daily recommended dose of vitamin E for adults is only 22.4 IU. Consult your doctor about taking supplements—whether you should take them, and if so, which ones, how much, and how often.

Many older people take medication to treat high blood pressure, high cholesterol, depression, diabetes, arthritis, and a host of other problems. In fact, the average older American may be taking four different prescription medications at the same time. Some of these medicines have side effects—perhaps nausea, dizziness, or constipation, for example. The more medications we take, the greater are the chances of unwanted side effects. If side effects occur, we may be given additional medications to take to address the adverse reactions of the other medications. The result is called polypharmacy, the taking of multiple drugs at the same time when some of them are to counter adverse effects of other medications being taken. A recent study reported that polypharmacy can be more of a fall risk factor than the diseases for which the original medicines were prescribed.

The following is a hypothetical example of how polypharmacy can increase the risk of falling. Bill takes a prescription drug that causes him some nausea and gastric irritation. To address the nausea and gastric irritation, he takes an additional drug, which in turn causes him to retain fluid. He takes a pill to help eliminate the fluid, but that pill causes dizziness. To address the dizziness, he takes another medication. Bill started taking one drug and ended up taking four. Consider that Bill’s fluid pill causes him to urinate with greater frequency, including needing to get up during the night. If he experiences dizziness, and is walking to the bathroom in the middle of the night (most likely in low light, and without his glasses), he has greatly increased his chances for a fall.

Some medications raise particular concerns for falls, and thus it is important that someone monitor people who are taking that medication. These drugs include blood pressure medications, medicines for diabetes, and anti-anxiety medications—all of which have the potential to cause dizziness. Neither very high nor very low blood pressure is good. Low blood pressure or a sudden drop in blood pressure can make you dizzy and unsteady on your feet, and thus increase the likelihood of a fall. While high blood pressure in itself usually has no symptoms, treatment of high blood pressure can make you dizzy. A recent study conducted in England found that thiazide antihypertensive drugs (those that reduce blood pressure by increasing urine output) were associated with an increased risk of falls, especially in the first three weeks of taking them. Although the researchers did not mention getting up in the middle of the night to urinate as a possible factor, another study noted that many falls occur between midnight and 6 a.m. Another study recommended that fall prevention programs include an assessment of the person’s urination frequency and referral for treatment to ease symptoms of urge incontinence.

Treatment of diabetes requires monitoring of blood sugar. If blood sugar is too high, adjustment to diet or medication is necessary. If blood sugar drops too low (called hypoglycemia), a person can become dizzy and unsteady and thus be at increased risk for a fall. Therapeutic insulin, a hormone given to people who have diabetes to lower their blood sugar, has been shown to be a risk factor for falls among older persons. This suggests a relationship between the treatment and its potential to result in too low a level of blood sugar, and it emphasizes the importance of closely monitoring a patient on this medication. So, persons with diabetes are well advised to accurately track their blood sugar and take measures to improve their safety, since both the disease and certain treatments are risk factors for falling.

Anti-anxiety drugs are commonly prescribed for older people who show signs of agitation. There is a high incidence of dizziness as a side effect from these medications. A Canadian study that examined falls in an older population for whom an anti-anxiety medication had been prescribed (most commonly lorazepam or zopiclone) found that among patients who fell, nearly half had begun taking the anti-anxiety medication within seven days before the fall.

These are only a few kinds of medications that are associated with an increased risk for falls. Others can pose the same risk. All medications should be taken exactly as directed, that is, the correct amount at the recommended times of day for the number of days indicated, and the patient should be monitored for possible medication-related changes. Many older people are on medications for lengthy periods of time, some perhaps for the rest of their lives. It is good practice to periodically review with your doctor and/or pharmacist all the medicines you are taking, so any potential fall risks can be brought to light. Another reason to review medications is to identify any potential drug interactions and identify any potential for overdosing by taking multiple medications that contain the same active ingredients. Be sure to review over-the-counter (OTC) nonprescription drugs, including herbal preparations and supplements. Because OTC medications are convenient, relatively inexpensive, widely available, and don’t require a prescription, people may view them differently from prescription drugs and may treat them as if they could be taken liberally, without concern, and without side effects. But OTC medicines also have a maximum daily dosage, a limited overall period for taking the medicine, and specific instructions—for example to take the medicine with food—and these admonitions should be adhered to with the same care you would take with a prescription drug.

A study based on a review of the literature from 1966 through 2008 showed an increased risk for falls in older individuals exposed to NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), although it did not elaborate on the reasons. Some common over-the-counter NSAIDs are aspirin, ibuprofen (Advil and Motrin), and naproxen (Aleve). These drugs are popular among the older population because they ease arthritis pain and are generally perceived as being safe (although taken in excess they can cause stomach problems, including ulcers).

Finding a balance between taking the drugs that are necessary for one’s health and comfort and avoiding injury related to poly-pharmacy will be one of the biggest challenges for public health professionals in this century. Doctors and patients need to work together to monitor how many and which drugs and remedies are being taken. The goal is not to find a set number of medications and try to stay below that number but to find the right medications at the right dosages and for the shortest possible duration. Tell your doctor these are the criteria you want followed when your medications are prescribed. This approach may keep your treatment safer and more effective and may also help improve your quality of life. (Medicine related poisoning is discussed in Chapter 3.)

Seeing clearly, including having good depth perception, is extremely important for fall prevention. It has been reported that people with reduced visual acuity are 1.7 times more likely to fall and 1.9 times more likely to have multiple falls compared to fully sighted people. Regular eye exams are recommended especially as we age, not only to ensure adequate magnification, but also as a way to detect cataracts, glaucoma, macular degeneration, and other serious eye problems early in their development. Many people 65 or older do not get regular eye exams because they believe there is no need, but vision is very much a factor in good overall health. Perhaps because poor vision does not make one “sick” in the traditional sense, it may not be taken as seriously as a condition that has a more obvious or a painful physical effect.

While eyeglasses are a helpful aid, changes in magnification can, ironically, increase the risk of falls in the short term. You may have had the experience of an adjustment period after your glasses prescription has been changed. But don’t let this keep you from addressing your future vision needs; you just need to be aware of how changes in magnification can affect your gait and make you more susceptible to falls while you are getting used to the prescription. If your new prescription makes things bigger, they appear closer; if it makes things smaller, they appear more distant. These differences in depth perception can affect our movements. We may think we have placed a foot on a step or curb before we actually reach that step or curb. We may take higher, shorter steps. These are natural gait adjustments in response to changes in magnification. Getting used to new glasses requires a bit of time, but our eyes and brains do adjust reasonably quickly. It is much safer in the long run to have corrected vision.

Have you ever had an eyeglass prescription that was “off”? Did it make you dizzy or affect your balance? If a person experiences any dizziness or problems seeing clearly after a new prescription, he should go back to the optometrist or ophthalmologist and have the prescription rechecked. Dizziness that cannot otherwise be medically explained might be due, for example, to a bifocal lens sitting too high in the eyeglasses and interfering with distance vision. While a person may not detect the problem, the person’s body may react by losing its sense of balance. Remember, what we see helps orient us in space.

More serious eye impairments, like cataracts and macular degeneration, contribute to falls because they can reduce contrast sensitivity and visual clarity (see Chapter 1). Early cataract surgery has been shown to reduce the rate of falls.

A secondary effect of vision problems is that people may decide to become less mobile. When people do not move, they lose muscle strength. Thus, one impairment—reduced vision—affects a totally different fall risk factor—strength. We begin to see how a combination of factors can make matters even worse. One study showed that poor vision itself was not as significant a factor in falls as the fact that the low vision made the person less active. The loss of strength from inactivity was the greater risk factor.

Hearing loss may not be as obvious a risk factor for falling as vision loss, but it nonetheless is a factor, in part because of its close relationship to balance. With hearing loss, we can lose some sense of where we are in space—and that loss affects a person’s sense of balance, increasing the risk of falls. A hearing problem can be indicative of an underlying balance problem, and a balance problem can be indicative of an underlying hearing loss, so pursuing good hearing health is indeed a part of maintaining overall good health in addition to being a fall prevention measure. A 2012 study found that having a hearing loss, regardless of whether it is moderate or severe, triples the risk of falling for people in their forties and older.

Vision and hearing health care are addressed in Chapter 9.

There is increasing evidence that foot problems and inappropriate footwear increase the risk of falls. Non-healing foot sores, foot deformity, pain associated with deep calluses, and not clipping one’s toenails have all been associated with falls. Certain disease conditions, for example diabetes, can affect the feet and have a significant effect on fall risk. A condition called diabetic neuropathy (which is diabetes-related nerve damage) can cause numbness in the feet, which in turn makes it very difficult for the feet to “sense” where they are in space and to respond appropriately when contacting surfaces. We may not realize how much important information we sense through our feet, such as where the edge of a step is or whether we are walking on level or sloping ground.

Taking good care of one’s feet and toenails may become more difficult as we get older. We may not be able to easily reach our feet because of reduced flexibility; we may not see clearly enough to perform the cutting and cleaning of toenails; arthritis may reduce the strength or dexterity of our hands, making using nail clippers or scissors difficult. People who have diabetes may not be able to feel what they are doing, and as a result they may do more harm than good. Poor foot care can result in pain and infection. Seeing a podiatrist can often be beneficial. (See Chapter 9.) Given all that our feet do for us, they deserve to be well cared for.

Keep physically active, within what’s reasonable, to help maintain strength. Consider an exercise program that includes balance practice. Many gyms and councils on aging offer programs tailored for the older population. Yoga and tai chi are also popular and are excellent for this age group.

Eat a balanced diet and drink plenty of water. Pay attention to any diet restrictions the doctor has ordered. Have someone help with food shopping and preparation if necessary.

Routinely have your vision and hearing checked, as these senses affect balance.

Take good care of your feet. See a podiatrist as needed.

Know what medicines you are taking and make note of any side effects you experience. Review your medication history, both prescription and over-the-counter, with your doctors and other health providers.

Let’s now turn to extrinsic risk factors for falls. Extrinsic factors are those “outside” the person. Here are examples of extrinsic factors: clothing and shoes the person wears; any walking aids, like canes, crutches, and walkers; and household items, like rugs, pillows, lights, and so on (see Figure 2.2). Extrinsic factors theoretically include everything in the household environment.

Data from the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission indicate that in 2010, 40 percent or more of emergency room treated injuries that were associated with the products listed in Table 2.1 happened to people 65 or older. The data also show that falls were a common injury pattern. The list is arranged in order of decreasing number of injuries to people 65 or older. The number of injuries associated with a certain category of product is then shown as a percentage of all injuries associated with that product, regardless of the person’s age. An expanded list appears in Appendix A and includes products for which 25 percent or more of emergency room treated injuries associated with those products happened to people 65 or older.

Other household items often associated with falls among older persons include beds, bedding, clothing, and telephones. Some other sources of fall risk are inappropriate footwear, low chairs, dim lighting, bifocal or progressive eyeglass lenses, and pets.

The goal of this section is to help you identify relevant extrinsic factors that could contribute to the risk of falls in your home. If you prefer, you can obtain an evaluation specific to your home by employing a professional home-hazard assessment service. A systematic way to identify extrinsic fall risk factors is to start physically closest to the person (clothing) and move outward to furniture and household items, going room by room. This is the pattern I have used in organizing the following sections. (Chapter 8 contains illustrations of rooms and other areas that have been designed to minimize the risk of injury.)

Table 2.1. Frequency of Product-Related Injury among People Ages 65 and Older in 2010

Product |

Number of injuries |

Percentage of injuries |

Crutches, canes, walkers |

102,815 |

77% of 133,527 injuries |

Wheelchairs |

96,261 |

66% of 145,850 injuries |

Toilets |

54,080 |

52% of 103,998 injuries |

Rugs or carpets |

49,560 |

41% of 120,873 injuries |

Runners, throw rugs, |

9,940 |

51% of 19,490 injuries |

Recliner chairs |

9,585 |

40% of 23,960 injuries |

Step ladders |

4,785 |

41% of 11,671 injuries |

Electrical cords |

4,030 |

40% of 10,083 injuries |

Scales |

1,306 |

55% of 2,375 injuries |

Thinking about tripping and falling hazards, focus on how you or the person you are helping gets dressed and what the person wears. Here is a variety of possible fall scenarios. These incidents each resulted in a visit to a hospital emergency room in 2010.

A 91-year-old fell backwards while trying to put on a pair of pants.

A 75-year-old got a pants leg caught on a stair rail and fell down the stairs.

An 86-year-old slipped and fell while wearing panty hose and no shoes.

An 82-year-old tripped over untied shoelaces and fell.

A 65-year-old fell down two steps when the heel of her shoe got caught in a crack on a step.

An 83-year-old fell because of ill-fitting slippers.

A 69-year-old tripped on his robe while on the stairs and fell, hitting a radiator.

An 81-year-old tripped on pajama pants on his way back from the bathroom.

These incidents illustrate some important clothing-related issues:

• Getting dressed while standing may be dangerous for someone who has poor balance, especially putting on any kind of pants, which requires standing on one leg while engaging in a multipart activity.

• Belts or loose clothing can drag on the floor, get stepped on, or snag on hooks or other protrusions and create a tripping hazard or cause a person to lose her balance.

• Walking in just socks or stockings or wearing ill-fitting footwear can create a slip or trip hazard.

Here are two key questions to consider: Is the person able to get dressed alone safely or does he or she need assistance, and should the person get dressed from a seated rather than standing position? Strength, balance, and vision have to be very good for a person to get dressed in a standing position. If there are deficiencies in any of these areas, a chair is needed in the bedroom or dressing area. (Before making a decision on the kind of chair that will be most suitable, review the section later in this chapter on types of chairs.) Note that the suggestion is to use a chair, not the bed. As you will discover in the discussion on the bedroom, bed linens can make a bed a slippery surface; a bed can act like a slide for a person sitting on it.

Next, what clothing characteristics need to be considered? Figure 2.3 illustrates some common hazards.

Take a look at pants, skirts, pajamas, nightgowns, and bathrobes, noting any part of the garment or related item (like a belt) that hangs near the floor. Make sure the garment always clears the floor when the person is walking. Clothing that drags along the floor can create a tripping hazard.

Full, flowing clothing and dangling accessories can catch on other items and throw the person off balance. Look at sleeves, belts, belt loops, pant legs, and tops. Do they fit close to the body and not dangle?

Figure 2.3. Clothing-related fall risk factors: pants that drag along the floor, stocking feet, dangling belt, and backless slippers

Does the footwear provide support and fit well? Loose, ill-fitting, or very soft shoes, like slippers or moccasins, lack support and can create a tripping hazard. Shoes that are too tight or in any way make a foot hurt will affect a person’s gait and balance. An older person should not wear shoes or slippers that are loose-fitting or backless. Daywear shoes should either lace up or close with Velcro® to be secure on the feet.

Are the shoes flat or do they have at most a small heel? Flatter shoes provide greater stability. Check the soles and heels. Are they worn out or in need of repair? Or should the shoes be replaced? Leather soles and worn soles can be slippery. Preferably, soles should be skid-resistant synthetic or rubber.

Going barefoot or walking around in stocking feet is dangerous because there is less traction than when a person is wearing shoes. Feet must be comfortable inside shoes, and the kind of socks or stockings worn can contribute to comfort or discomfort. Hosiery that is too thin can make shoes fit too loosely. If hose have thinned from wear, parts of the shoe may rub directly against the foot, causing blisters, abrasions, or calluses. We have already noted that foot problems can affect gait.

Robes, pajamas, and nightgowns should not drag along the floor. Because a person might be shoeless at night time, or wearing slippers, the length of nightwear should be assessed on the assumption that the person may be shoeless. Make sure these garments clear the floor by at least 2 inches.

Climbing stairs can make clothing behave differently, so if there are stairs that the person must negotiate, take a look at how the clothing behaves on stairs. The hemline of nightgowns and bathrobes will probably need to be higher than you would think to account for people forgetting to lift the hem as they climb, even if it’s only one step.

While we are on the subject of clothes, I should mention that there is a garment that is specifically made to protect from injury during a fall. A hip protector is an undergarment worn so that in case of a fall the hip is less likely to be fractured. It works by absorbing or redistributing the impact of a fall. In one study, people who participated in a one-week trial of different brands of hip protectors reported that they found them uncomfortable, a poor fit, inconvenient, and unflattering. Few people in the trial spontaneously mentioned the protective benefits of hip protectors. A person’s beliefs in the benefits of a hip protector will influence whether they choose to wear one. If a person is at a high risk for falling and has fragile bones, it would be appropriate to discuss hip protectors with her or his doctor.

Since the bedroom is a typical place for people to get dressed, take a look around, keeping in mind the following reported incidents:

A 78-year-old who was getting out of bed got tangled in the sheets and fell.

A 73-year-old was sitting on the bed when the comforter slipped and she fell to the floor.

A 68-year-old tripped on a blanket, part of which was draped on the floor, and fell to her knees.

A 66-year-old who was changing the bed got caught in the sheets and fell.

To prevent falling out of bed, some people choose bed rails, but rails produce mixed results, and they can create hazards. A bed rail is an additional object into which an elderly person can fall while walking around in the bedroom. And they aren’t always effective; some people actually fall out of bed over the top of the installed bed rail. Sometimes people become entrapped in the spaces of the bed rails (see Chapter 5, Figure 5.1). If the risk of falling out of bed is high, you might consider a hospital bed or similar bed whose height from the floor can be changed. Lowering the fall height might be the better solution, rather than installing bed rails.

As for the hazards associated with bedding, try to reduce the likelihood of entanglement by using the correct size linens for the bed. Use a fitted sheet for the bottom sheet and tuck in the top sheet, blankets, and covers so they do not dangle on the floor. When choosing the material for bedding, avoid satiny or silky textures, because these make the bed surface slippery. A person can slide off the bed onto the floor while trying to get into or out of bed, or while sitting on the bed trying to get dressed. (This is why a chair is a safer option.) Choose cotton, flannel, or blends that are less silky. Make the bed soon after you or the person you are caring for gets up; this will help keep the bedding in place, reducing the risk of entanglement and tripping.

It doesn’t take special training to see some of the fall risks in bathrooms. Toilets, showers, bathtubs, and scales all can pose risks. People lose their balance and fall when they are getting on or off the toilet. Grab bars or support bars can easily be added; they provide something to hold onto and help the person stay balanced while transitioning. A wide variety of designs is available. Raising the height of the toilet seat by using an accessory seat may also be helpful. These seats are sometimes equipped with handles, making it easier for the person to be guided on and off the seat.

Assess the ease of getting into the shower or tub. Grab bars will help, but if a person cannot easily step over the edge of a tub or shower, consider installing a walk-in shower or tub. These eliminate or greatly lower the edge the bather has to step over. To reduce the risk of falling once you are in the tub or shower, install grab bars and non-slip mats and consider using a shower seat. Shower stools or chairs are readily available, light weight, and easy to keep clean. Using a handheld shower head makes it easier for a seated person to bathe or be bathed; the water flow is easier to control for both seated and standing positions. Make sure that bathing needs—shampoo, soap, towels—are within easy reach. (See Figure 8.5.)

A scale can be a tripping hazard if it protrudes into a pathway, and getting on and off a scale requires good balance. If you have a scale, place it out of the walking pathway and position it near grab bars or some solid surface for the person to use as an assist to balance.

The bathroom will likely be used during the night by older people, so the path to the bathroom must be clear and sufficiently lit. You might have to think about rearranging bedroom furniture to make getting out of the bedroom and to a bathroom easier. Night lights can act as a guide in the dark, and a person can turn on additional lighting as necessary. Consider keeping a flashlight on a nightstand.

Falls in the kitchen are often related to over-reaching. Reaching requires flexibility and precise motor coordination; reaching for far away objects can throw you off balance. To get at out-of-reach items, some people stand on a chair, some on a step stool or small ladder. Chairs can be unsteady and are not intended for standing. My mother once stood on a wheeled chair on a sloping tiled floor to reach an item in a kitchen cabinet! By some good fortune she was not hurt as the chair moved across the floor.

Older people should consider rearranging items in the kitchen cabinets so that those used often are well within reach. You might wish to buy a “reach stick,” a special grabbing tool available at most hardware and medical supply stores. If you need to use a step stool, look for one with a handrail to help you keep your balance as you climb up and down. If you opt for a ladder, never stand on the top step. Invest in a sturdy step stool or ladder that is easy to open and lock in place. (See Chapter 8.)

Kitchen falls are also related to scatter rugs. It’s best to forego them. Kitchen floors can be slippery, when wet with spilled food or drink, when being washed, or after being waxed. Clean up spills right away; let floors dry thoroughly after being washed before walking on them; and skip waxing.

Beware of kitchen and dining room chairs with loose cushions. Make sure the cushions are securely tied to the chair. Cushions may seem harmless, but when one 75-year-old woman sat down on a chair, the unsecured cushion moved and caused her to slip out of the chair and onto the floor. She broke her hip.

Rugs and chairs are the most common fall hazards in the living room. About half of all rug-related injuries occur among people 65 or older. The rugs that are problematic include runners, area rugs, doormats, throw rugs, scatter rugs, and so on, rather than wall-to-wall carpeting. The most common scenarios involve tripping and getting tangled in the rug, resulting in a fall to the floor. We can readily recognize why area rugs inherently present a trip and fall hazard. They can have fringe, cause changes in elevation of the walking surface, and they can gather and slide. The hazard can be exaggerated by a person’s gait, type of shoe, degree of haste (as in hurrying to answer the phone), use of a walker or cane, and by the presence of extension cords.

Obviously, one can eliminate all hazards posed by rugs by removing all rugs. If this is not possible or desirable, consider each scatter rug, doormat, runner, area rug, and so on, then remove those that you believe pose the most severe hazard, whether because of their location (for example, in a frequently used pathway), condition (for example, frayed or unevenly worn), or design (having fringe or other decorative edging). For rugs you keep, add a slip-resistant pad underneath. If someone in the house uses a walker or cane or wheelchair, it is probably best to eliminate these kinds of floor coverings altogether. (See section on walking aids below.)

As for chairs, most reported incidents of falls involving them occurred when people were getting into or out of a chair or when a chair fell over backwards. Getting up or sitting down requires weight transfer, and weight transfer requires strength. To gauge the safety of chairs, look closely at the kind of chair, the area around the chair, and how the older person in question tends to sit.

• How high off the floor is the seat?

• Does the chair have arms?

• What material is the covering?

• Is the chair a recliner or does it have some mechanical features?

• Does the person use a pillow to sit on or at her back?

• Does the seat tilt backward? Forward?

• If the person falls getting out of the chair, what might he fall onto?

• Look around. Are there nearby glass topped tables, sharp corners on tables, fireplace edges or andirons?

Chairs should be easy to get into and out of. They should have arms to help with stability while sitting down and getting up from the chair. The chair itself should not move, like sliding on the floor. Recliners may be comfortable once you are settled in, but getting into and out of them poses some particular issues for older persons. Recliners tend to be big, deep, and to require considerable strength to move from one position to another. They can be difficult to get out of, and people have fallen while trying to get out of them.

In deciding which chair is best, look at the seat area. Does it tilt backwards, forwards, or is it level? If it tilts backwards, that would add to the difficulty of getting out of it. If the seat is low or very deep, that too would add to the difficulty of getting into or out of it. Can the person’s feet make solid contact with the floor while he or she is getting up? Good contact with the floor will add to stability.

Getting up quickly from a chair to answer the telephone is a well-documented fall hazard. Place a phone near your favorite chair. If that is not possible, use an answering machine and set it to respond on the least number of rings. Then, listen to messages at your leisure, without rushing. If you have a cell phone, keep it with you.

Refer again to Figure 2.2 as a guide for assessing your household environment. Also see Chapter 8. Since many falls occur because of tripping, start by looking at your floor. We addressed the issue of rugs above. Extension cords are certainly convenient equipment and are necessary at times, but you should make every effort to minimize their use. If you do use them, run them on the floor along a wall, not under a rug or anywhere that they might get under foot. Electrical cords in the walking path are an invitation to tripping, as the injury data attest. Electrical cords under carpeting have the potential to be stepped on, be damaged, and overheat. These conditions can lead to a short in the wiring and subsequent fire.

Do you have a dog or cat? Pets are wonderful. They offer companionship and entertainment and keep you involved. But, they can be tripped over too! Each year between 2001 and 2006, an estimated 18,500 people 65 or older were treated in hospital emergency rooms for falls associated with a dog, and about 2,500 for falls associated with a cat. The highest rates of injury were among those 75 or older. The majority of these 21,000 falls occurred in and around the home. Women were more likely than men to fall, and fractures were a common result of these falls. I’m not suggesting you give up your pet, but be aware of where your pet is before you rise from a chair and as you walk around.

Is your home an obstacle course? How many things do you have to walk around to get from point A to point B? Coffee tables are notorious roadblocks. Falls onto coffee tables result in a range of injuries. Consider replacing glass tables with wood; consider a table with rounded rather than sharp corners; consider end tables instead of coffee tables.

Clutter can also be a pathway obstacle. Clutter is a known tripping hazard, especially if it is on stairs. Stairs and hallways should remain free of newspapers, magazines, mail, boxes, shoes, and so on.

Are there changes in elevation as you navigate the home—perhaps one step up or down to a kitchen or living room or raised thresholds in doorways? Consider marking these points of change with contrasting colored paint or tape so they stand out, especially if someone in the house has diminished vision or poor balance.

Are all areas well lit? Rooms should have good, even lighting, and so should hallways and stairs. Dim lighting is a factor in falls, especially for people who have vision problems. Light switches should be available at both ends of hallways and at the top and bottom of stairs. This last feature is so helpful it is worth the expense of an electrician to add switches.

Examine stairs for loose handrails, worn or loose carpet, and worn or uneven steps; determine if repairs are needed. High-traction tread surfaces, which allow the soles of shoes to grip well, are recommended on stairs. Examine outdoor stairs. Be sure they also are well lit and have handrails. Are the stair treads textured to help minimize the risk of slipping in inclement weather?

Keep in mind these common tripping hazards:

• extension cords

• obstacles or clutter in a pathway

• uneven surfaces

• poorly lit areas

Ironically, devices intended to assist a person in walking—canes, walkers, and crutches—can pose fall hazards, as Table 2.1 and Appendix A testify. A 2009 study reported that the most frequent fall-related injury associated with walking aids was a fracture and that 60 percent of the incidents occurred at home. Although more than twice as many adults use canes as walkers, walkers were associated with the greater number of falls, seven times as many as with canes. The authors of the study explained that some of the differences between cane- and walker-related injuries were due to the fact that people who use walkers are weaker, frailer, and have poorer balance and greater mobility limitations than do people who use canes. They also suggested that people may have trouble using walkers effectively.

You may think that walkers are easy to use, but they are not. There’s a right and wrong way to move with them on level ground, to turn around, and to position the walker in order to be able to sit down on or get up from a chair. Thresholds, ramps, and curbs require skill to manage. It takes some time to learn how to “operate” a walker. Imagine the challenge for older people. My father was in his nineties when he first used a walker. He was still very skilled cognitively. I overheard the instructions for use of the walker given to him by the visiting nurse. I thought it was a lot to digest at once, even though he was given the opportunity to practice. With certainty I can say that he did not use the walker according to instructions; rather, he adapted the technique in a manner that seemed intuitive to him. Fortunately he never fell, but I saw the walker as a mixed blessing.

The report authors concluded that more research was needed into how to design better walking aids. They also pointed out that more information was needed about the circumstances preceding falls associated with walking aids, both to better understand the contributing fall risk factors and to develop specific and effective fall prevention strategies. Their concern was well placed: knowing how a person falls will guide us to better prevention strategies.

If you are considering using a walking aid or have been told you need to, choose one that is right for you, as advised by your doctor or a physical therapist or other professional. Then learn how to use it correctly. Ask about the right way to do things, and practice. Visiting nurses and the staff at medical supply companies can help. And remember that when you use a walking aid, you need more space around you as you move about. That could mean that objects that were not in your way before might become obstacles now. A little revision to your household environment may be necessary.

Many extrinsic fall risk factors have been identified in this chapter. The following list is a quick review of key prevention steps for each area discussed.

✓ Do a wardrobe check, eliminating or altering clothes that create a tripping hazard and repairing or replacing unsafe footwear.

✓ Make up the bed right away after rising, tucking in sheets and blankets so nothing drags on the floor.

✓ Install grab bars in the bathroom to assist with stability and balance, especially at the toilet and in the shower or bathtub.

✓ Reorganize kitchen cabinets, storing frequently used items within easy reach. As needed, invest in a sturdy step stool and/or reaching tools.

✓ Route electrical cords along the wall, not under carpet.

✓ Keep stairways and hallways well lit and clutter-free. Hold onto the railing when using stairs. Arrange furniture so you don’t have to negotiate an obstacle course.

✓ If you need a cane or walker, get instructions in how to use it correctly.

In spite of all the prevention measures you take, you still could fall. If you fall and remain conscious, try to relax and take a reading of your body to decide if you can get up. Wiggle your fingers and toes, and take a few full and slow breaths. If you can call for help, do so. Don’t rush to get up. Getting up quickly or the wrong way could make an injury worse. If you feel that you can get up by yourself, follow the directions given below and illustrated in Figure 2.4 to help you do that safely.

First, look around for a sturdy piece of furniture you can sit on or the bottom of a staircase. Don’t try to stand up without support. We use a chair as an example in the illustrations.

1. Roll onto your side: turn your head in the direction you want to roll (towards the chair); roll over onto your side by moving first your shoulders, then arm, hips, and finally lift your leg over.

2. Use your upward arm and hand, followed by help from the lower arm and hand, to push up to a kneeling position.

3. Slowly crawl to the chair.

4. Place your hands on the chair and slide one foot forward so that it is flat on the floor. Keep the other knee on the floor.

5. Slowly rise and turn your body to sit on the chair.

6. Sit calmly for a few minutes before trying to do anything else.

Figure 2.4. Getting up safely after a fall

Now, try to review, and if possible write down, what happened just before you fell and describe how you fell, so you can share this information with your doctor and others to help them understand why you fell. Note the date, time of day, and where you fell. What were you doing just before you fell? How did you fall—for example, did you trip over something or did you lose your balance? One study described four distinct kinds of falls: collapse (fall in a heap), fall in a direction (topple like a tree), trip or forward fall (failure to clear the surface—the foot catches on something), and sensory fall (insufficient sensory input for balance—for example, you took a step but didn’t feel your foot touch the floor). Can you place your fall into one of these categories?

With this information, your doctor may be able to identify an underlying cause for the fall. Collapse can indicate a sudden acute condition, like a seizure, or a dramatic drop in blood pressure. This kind of fall would be a clue that intrinsic factors are involved. Falls in a direction are also likely to be related to intrinsic factors, for example an artificial hip slips out of its socket, or a person suffers a spontaneous fracture. A forward fall most likely reflects a trip over an obstacle and probably occurs while a person is walking. Tripping always involves an extrinsic factor, perhaps in addition to an intrinsic one. A forward fall may also be related to gait. A gait known as “freezing feet”—where the feet stop, but the body continues forward—forces a person out of balance, so they fall. A sensory fall is suspected when a person falls while walking (but does not trip) and experiences vertigo or dizziness. If an underlying cause can be identified, it will be much easier to correct the problem and avoid falling again.

You may want to consider a medical alert service to provide assistance in getting up after a fall. These types of services often incorporate a pendant- or bracelet-style help button that a person can press when he or she falls and cannot get up on their own. Some devices recognize when a person has fallen and automatically call for help even without the person’s pressing the button. Some examples of medical alert services include: Philips Lifeline, LifeFone, and Medical Alert. An Internet search for “medical alert services” will yield several options to consider.

A person’s perceptions and beliefs about their risk of falling will influence their decision to undertake fall prevention measures and their commitment to following the steps they have chosen. Fall prevention should be encouraged as a way to promote health and maintain independence. If an older person believes that fall prevention measures matter, he or she is more likely to participate in prevention strategies and to do so with a positive attitude. If a person just expects to fall and doesn’t think anything can be done to prevent falls, then that person will be less likely to accept that fall prevention measures will work, and thus will be less willing to participate in preventive measures. If a person thinks he or she isn’t ever going to fall, it may be difficult to get that person to engage in fall risk assessment and undertake preventive measures.

Although falling can instill a fear of falling, it may still not motivate the person to take preventive steps. Family and community support for fall prevention helps older people recognize that falls don’t have to be part of normal aging. Knowing that you have control over some fall risk factors will help reduce the fear of falling, as well. Fall prevention messages from public health organizations target seniors, urging them to focus on the positive health and social benefits of taking steps to prevent falls.

Avoiding a first fall is the best way to minimize the risk of falls. Maintaining strength seems to be the major preventive measure one can take. It is strongly suggested that one incorporate several preventive measures, so you build a broad and diverse defense against falling. The following components are encouraged: exercises, particularly those for balance, strength, and gait training; modification of the home environment; minimization of medications; management of blood pressure and blood sugar; correction of vision and hearing losses; and management of foot problems and footwear. These interventions have been proven to be effective in decreasing falls and fall-related injuries. Adopting several of these intervention approaches offers the best promise of effective fall prevention. It is possible to prevent falls and, most importantly, injuries and death related to falls.