One way to reduce the risk of injury is to stay as healthy as you can. We have discussed the injury preventive benefits of exercise, good nutrition, hearing and vision care, and attention to medication regimens. Regular checkups with your doctor also help keep you strong and healthy. A key component of any visit to a doctor is understanding what happened during the visit. Understanding what your doctor tells you and what you read about your health is called “health literacy.” The term “health literacy” is defined as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health or medical decisions.” To get an idea of your level of health literacy, think about a recent visit you have had with a doctor and ask yourself the following questions:

• Did I come away from the visit with a thorough understanding of what went on? Did I ask questions about anything I did not fully understand? (The answer to these questions should be yes.)

• Did I agree for the sake of agreeing, without having a clear understanding of what I was agreeing with? (The answer should be no.)

• Could I hear everything the doctor said, or did I “fill in” with what I thought he meant when I could not make out what was being said? (You should be able to hear what your doctor is saying and say so if you can’t.)

• Was I able to accurately answer questions about myself? Did I understand the forms I was asked to fill out? (The answers should be yes.)

The first part of this chapter explains how to become more health literate and how to get the most from your doctor visits. The second part of the chapter further explores treatment of four specific areas of health: hearing, vision, feet, and teeth. Making the most of the assistance available in these areas of health care will help you stay active and healthy longer.

Health literacy gives you the tools to make good health decisions. An astonishing 40 percent of the U.S. population is affected by low health literacy; the adults most vulnerable to health illiteracy are older people, people with limited English-language proficiency, poor people, homeless people, and people with less education. People with low health literacy may have difficulty with a number of tasks that are crucial for good health, such as:

understanding and following directions for taking medications

reading a nutrition label

asking questions of doctors

sharing their medical history with health care providers

completing health information forms

understanding preventive care

In contrast, people with good health literacy can find information from books, the Internet, and elsewhere; read and understand information; read prescription bottles; take medications correctly; follow complex instructions, such as the preparation needed for a colonoscopy; make and keep appointments more successfully; and complete health information forms, such as a family medical history.

Low health literacy puts people at risk for failing to seek out and receive good health care, and it puts people’s safety at risk because they lack a good understanding of what they should do about their health. For example, many people who are trying to conserve their funds decide to make their medication go further by cutting their pills in half—without understanding how the reduced drug dosage may affect their health.

The following additional examples highlight some common areas of misunderstanding about medicine which can lead to errors.

For example, if the instructions for a medication say to take it every four hours, do you need to get up in the middle of the night to stay on schedule or should you take the medicine only during the hours you are awake? (You should ask the doctor or pharmacist.)

If you are a diabetic who should be checking your blood sugar levels, do you follow the instructions to ensure that the glucose meter is reading accurately, or do you skip that step and assume the meter is correct? (Calibrating the glucose meter makes it an accurate tool; without calibration, it is much less useful or possibly useless.)

Do you know where to get influenza and other vaccines? Do you know which vaccinations you should get? (Flu shots and other vaccines can ward off illnesses that in some cases may even be fatal. Your doctor, health clinic, and pharmacy can help.)

Do you have a relationship with a doctor from whom you can seek treatment guidance? (Regularly seeing and communicating with a doctor who knows you may result in better health outcomes.)

There is a lot of information to process when we interact with the health care system. Having a friend or family member go with you to a doctor’s appointment, especially if you are sick at the time, is a good way to improve your health literacy. For one thing, we all have more trouble paying attention and taking in information when we are sick, stressed, tired, anxious, or depressed. Your companion—it can be a son or daughter, a relative, or a friend—can take notes, help you remember events and dates, help you ask questions, and generally be your advocate. Your companion should be a person who has good cognitive skills and is alert enough to act as a second pair of ears and eyes for you. After the appointment, your advocate can help you remember what went on at the doctor’s office and be sure it is written down for your home health record.

One way the concept of health literacy is making an impact in the public arena is by placing more responsibility on the health community to improve how it delivers information. A U.S. government program called Healthy People noted that “clear, candid, accurate, culturally and linguistically competent provider-patient communication is essential for prevention, diagnosis, treatment and management of health concerns.” Healthy People sets ten-year national objectives for improving the health of all Americans. The current program, Healthy People 2020, has defined more than forty areas for health objectives, including the health of older adults. One of the objectives is to increase the proportion of older adults with one or more chronic conditions who report confidence in their own ability to manage their illnesses. You can see the role of health literacy in this objective; it means that people understand how to take their medications, know how to follow dietary restrictions, adhere to exercise or rehabilitation programs, and so on. The program also provides information on a wide range of health issues written in easy-to-understand language. To access this program’s website, go to www.healthypeople.gov/2020.

This improvement in how health information is delivered is an important step forward. Communication is a two-way process. Doctors need to be trained to watch for the signs of low health literacy, such as a disparity when a person claims that he or she is taking their medications correctly but the lab tests do not show the results that would be expected if this were true. If the problem is a misunderstanding on the part of the patient, the doctor must assume some responsibility for failing to communicate in a manner that the patient could comprehend. The doctor is the teacher and the patient the pupil. If the pupil is having trouble learning, it is the teacher who must try a new technique. Doctors should consider utilizing several different ways to deliver information: drawings or diagrams, videos, pamphlets or brochures, websites, storytelling, and so on. To ensure patient understanding, the doctor can ask the patient to repeat what he or she understood and should encourage the patient to ask further questions.

The patient needs to hold up the other side of the conversation. The National Patient Safety Foundation’s Partnership for Clear Health Communication encourages the “Ask me 3” approach for patients: three good questions to ask every time you speak with a health professional (doctor, nurse, pharmacist, etc.):

1. What is my main problem?

2. What do I need to do?

3. Why is it important for me to do this?

These very basic questions help to focus the discussion so that you get the information you need. To learn more, go to npsf.org/askme3.

Three other good questions relate specifically to medications:

1. What is this medicine for?

2. How should I take it?

3. What should I expect from the medicine, both the benefits and side effects?

Much remains to be done to simplify our health care maze. Just consider how difficult it is to choose a health insurance plan or a prescription drug plan. Do you understand your eligibility? Once you decide on a plan, do you understand your coverage? Do you understand those explanation of benefit (EOB) letters you get?

Health literacy campaigns call for language that can be understood the first time people read or hear it, so they can find what they need, understand what they find, and use what they find to meet their needs.

Now let’s examine how you can make the most of your visits to your doctor, whether he or she is your primary care physician or a specialist.

Your visits to your doctor should be two-way conversations. You ought to have the opportunity to ask questions and to confirm that you understand what the doctor is saying. You ought to feel comfortable speaking about sensitive issues, and you must be able to trust in the care you are receiving. What are you looking for in a doctor? Make a list of the things that are important to you. Your list might include:

• Am I more comfortable with a man or woman doctor, or is gender not important to me?

• Do I want my doctor to be affiliated with a particular hospital?

• Do I want a doctor with an individual practice or one who is part of a group so that group partners are available for me to see as well?

• Are office hours or office location important to me?

• Do I want a doctor who speaks my native language?

• Do I want to be able to e-mail the doctor? Have a phone conversation with the doctor?

• Do I want a doctor who considers alternative or complementary forms of care, like acupuncture?

• Am I prepared to pay extra to see a doctor who is outside my insurance plan’s network? HMOs (health maintenance organizations) and PPOs (preferred provider organizations) are networks of doctors. If you have one of these kinds of insurance, you may be required to see a doctor within that network or to pay extra if you wish to see one who is outside your network.

Doctors understand that patients’ needs change, and they understand that you must feel comfortable with your doctor. Do not decide to stay with a doctor you don’t really care for because you think you might hurt his or her feelings by seeing someone else. Your care is the most important factor.

• Ask friends, relatives, and medical and health care professionals which doctors they have had good experiences with and why.

• Look online for a doctor. Go to the American Medical Association website (ama-assn.org) and click on “find a doctor.”

• Check out doctors’ credentials. Many libraries have directories, such as the Directory of Physicians in the United States and the Official American Board of Certified Medical Specialists. For the most convenient source, go to MedlinePlus, the National Institutes of Health’s website for patients, their families, and friends: nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/directories.html. There you will find links to various helpful directories.

• Find out if a doctor you are considering is taking new patients.

• Make sure your insurance will be accepted by the doctor’s office. Find out if the doctor is accepting Medicare patients. If you are receiving Medicaid, ask if the doctor accepts it.

• Call your local or state medical society to find out if any complaints have been filed against a doctor you are considering.

• Consider setting up an appointment to “interview” the doctor. You will probably have to pay for this visit, but it will give you the best information about the doctor, his staff, and his office to help you make a decision.

When you start receiving care from a different doctor, ask that your medical records be sent from your previous doctor’s office before your first visit. It will save both you and the doctor a lot of time if he or she can review your records before seeing you. It will make you feel more relaxed if you do some advanced planning and thinking.

• How will you get to the doctor’s? If you are driving, know the route and where to park once you arrive. If you are taking public transportation, know the schedule, how far you may have to walk, and where you have to wait for the bus or train.

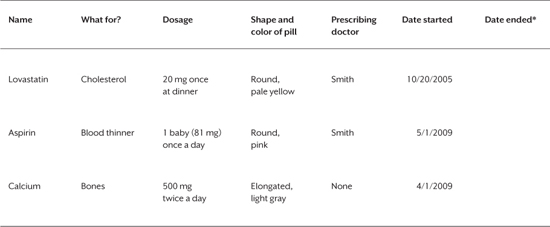

• Bring with you a list of all the medicines (prescriptions and over-the-counter products) you are taking and perhaps even take the bottles with you. Let the doctor know of any recent changes in your medications or symptoms. One good way to keep a record of your medicines is illustrated in Table 9.1.

• Make a list of all the concerns you want to discuss with the doctor. Start with the most important concerns. If there are major stresses in your life, let the doctor know what those are. Stress is a significant factor in health. This is not complaining; the doctor needs to know these things in order to make appropriate treatment plans for you.

• When discussing treatments, ask what the options are and how the different choices could affect you and your lifestyle. Ask about risks.

• Ask about preventive measures. What can you do to avoid illness and maintain health?

• Be honest in answering the doctor when he or she asks about your lifestyle, eating and sleeping habits, smoking and drinking habits, moods, and so on. Don’t report what you think the doctor wants to hear; report what’s true. Your honesty will help the doctor understand you better and make appropriate treatment recommendations for you.

• If you wear glasses or hearing devices, be sure to take them with you. Many older people misunderstand medical advice because they cannot hear well. Let the doctor and the office staff know if you need to receive written materials in large print or if you need for them to speak slowly and clearly so you can understand. These requests are nothing to be embarrassed about.

Table 9.1. Example of Medicine Record

*Consult with your doctor on how to stop taking any medication. Many medications will cause negative side effects if you stop taking them abruptly; your doctor will tell you how to wean yourself off them safely.

Note: Always tell your doctor about any prescription or over-the-counter medications or supplements, including herbal preparations, that you are taking, regularly or even occasionally.

• Bring someone with you—that advocate discussed earlier in this chapter. Ask him or her to take notes as you talk with the doctor; a lot of ground is covered in an initial office visit, and it is unlikely that you will remember everything that went on. If you want some time to be private between you and your doctor, let your companion know that as well.

• If you have any follow-up questions or need clarification on what the doctor said, jot down your questions and call the doctor’s office.

It is not unusual for a new doctor to make some changes in a patient’s medication regimen, either which medicines are being taken or the dosages. Talk with the doctor if you have concerns about polypharmacy, that is, taking many medications simultaneously (discussed in Chapter 2). Remember that the goal is to find the right medication for you at the right dosage and for the shortest possible duration.

These are some questions you might ask the doctor or your pharmacist about a new medicine prescribed for you. If it helps, write down the answers.

• What is the name of the medicine, and why am I taking it? Is it available and just as effective in a less expensive generic form?

• How many times a day should I take it? At what times? If the bottle says take “4 times a day,” does that mean 4 times in 24 hours or 4 times during the daytime?

• Should I take the medicine with food or without? Is there anything I should not eat or drink while taking this medicine?

• What does “as needed” mean?

• When should I stop taking the medicine?

• If I forget to take my medicine, what should I do?

• What side effects can I expect? What should I do if I have a problem?

Remind your doctor about any allergies and any problems you have had with medicines, such as rashes, indigestion, dizziness, or mood changes.

Because good hearing and vision are critical to overall health and safety, in addition to seeing a medical doctor, you might also see a doctor of audiology for your hearing health and a doctor of optometry for your vision health. A doctor of audiology is not a medical doctor but is a specialist in diagnosing and treating hearing problems. A doctor of optometry is not a medical doctor but is a specialist in evaluating your vision and prescribing corrective lenses. Hearing and vision are so important that you should be as picky about whom you see for these services as you are about your medical doctor.

The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association recommends having your hearing checked every three years after age 50. While many people are aware that their hearing is not what it used to be, they hesitate to see a hearing specialist because they don’t want to acknowledge their loss and they don’t want to wear hearing aids. Often it is an exhausted family member—exhausted from repeating phrases, shouting, putting up with a loud TV, and so on—who finally convinces a person to seek help. Here are some symptoms that tell you it’s time to see an audiologist.

• have trouble hearing over the telephone

• find it hard to follow conversations when two or more people are talking

• often ask people to repeat what they are saying

• need to turn up the TV volume so loud that others complain

• have a problem hearing because of background noise

• think that others are mumbling

• can’t understand when women and children speak

When you make the decision to have your hearing tested, the following explanation of terms will be helpful. An audiologist is professionally trained and licensed by the state to measure hearing loss and to fit hearing aids. At a minimum an audiologist has a masters degree and specialized training in hearing loss; in addition, some audiologists have a doctoral degree (Au.D. or Ph.D.). As of 2011, audiologists must have a minimum of a doctoral degree to practice. The doctoral degree requires four years of academic training beyond a bachelor’s degree. Coursework includes: anatomy, physiology, physics, genetics, normal and abnormal communication development, diagnosis and treatment of hearing problems, pharmacology, and ethics. Graduate programs also include supervised clinical practice.

A hearing instrument specialist (HIS) is someone authorized by the state to sell hearing aids. The credentials vary by state but typically involve taking a three-month class in subjects related to hearing, working as an apprentice to an already certified HIS, and passing a test about hearing aids in the state where the person is going to practice. A hearing instrument specialist is not an audiologist and does not have the academic training that an audiologist has. An HIS can “screen” for hearing loss but cannot evaluate, diagnose, or treat hearing loss. An HIS may have no education beyond high school. You are more likely to find an HIS working for a chain of retail stores that sell hearing aids, such as Costco or Miracle Ear®, whereas a doctor of audiology typically has an individual private practice, practices out of the office of an otolaryngologist (an ENT, a medical doctor who specializes in ear, nose, and throat health), or practices out of a hospital setting.

A doctor of audiology (Au.D.) provides individualized and continuous care of your hearing, much like your medical doctor does for your general health. For example, based on information from the American Academy of Audiology, a doctor of audiology

• uses audiometers, computers, and other devices to examine patients who have hearing, balance, or related ear problems in order to determine the extent of hearing damage and identify the underlying cause

• assesses the results of the examination and diagnoses problems

• determines and administers treatment

• fits and dispenses hearing aids

• teaches patients how to use and care for hearing aids

• counsels patients and their families on ways to listen and communicate

• can treat tinnitus (ringing or noises in the ears)

• sees patients regularly to check on hearing and balance and to continue or change the treatment plan

• keeps records on the progress of patients

Doctors of audiology measure the volume at which a person begins to hear sounds and the person’s ability to distinguish between types of sounds. Before recommending treatment options, they evaluate psychological information to estimate the impact of hearing loss on a patient. They also counsel patients on other ways of coping with profound hearing loss, such as lip reading and American Sign Language.

Since balance is such a significant factor in falls (see Chapter 2), and since the balance system is closely related to the hearing system, ask your audiologist to assess your balance. This should be a routine part of your hearing evaluation.

Sometimes, a hearing loss can be a symptom of a medical condition. A medical examination may uncover underlying illnesses or medical problems associated with your hearing loss. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regards a medical evaluation in the case of hearing loss so important that it requires all hearing aid sellers to tell clients that they should receive a medical examination before buying a hearing aid. The FDA also stipulates that people who decide to forego a medical evaluation before purchasing hearing aids must sign a waiver.

There are three common types of hearing loss: conductive, sensorineural, and mixed (a combination of those other two). Conductive hearing loss involves the outer ear, the middle ear, or both. (The human ear has three distinct sections, referred to as the outer, middle, and inner ear.) Conductive hearing loss usually results from a blockage by ear wax in the outer ear, a collection of fluid in the middle ear, a punctured ear drum, or disruption of the tiny bones (ossicles) behind the ear drum. Removal of ear wax and fluid is often easily performed by an otolaryngologist. Other middle ear problems may require surgery.

Sensorineural hearing loss involves damage to the inner ear. It can be caused by age, disease, illness, noise exposure, genetics, or exposure to certain medications (called ototoxic medications). This type of hearing loss cannot be corrected surgically but can be corrected or helped with hearing aids. This is the most common type of hearing loss among older people.

Mixed hearing loss may be treated by surgery, medication, hearing aids, or a combination of those treatments.

First, you will be amazed at the technology behind today’s hearing aids. They are smaller, smarter, and more powerful than ever. Older generation hearing aids (based on analog technology) just made all sounds louder; today’s digital hearing aids adjust for the different kinds of sounds and noises you hear, can be programmed for particular hearing environments (for example concerts, meetings, or quiet time), and allow you to hear in a manner much closer to the way people normally hear. Bluetooth technology (mentioned in Chapter 8) allows the hearing aids to connect, via a device called a streamer, to your phone, television, or other audio device, making those sounds amazingly clear.

Depending on your type of hearing loss, you might be treated with behind-the-ear aids, in-the-ear aids, or completely-in-the-canal (deep and not visible) aids. Cochlear implants are surgically inserted devices helpful to some people with severe hearing loss. Cochlear implants are tiny devices that are placed under the skin near the ear in a surgical operation performed by a medical doctor. Another part of the device is external and visible behind the ear. Cochlear implants deliver electrical impulses directly to the auditory nerve in the brain so that a person with certain types of deafness can hear.

Buying hearing aids online or via mail order is not recommended, because hearing aids must be custom fitted to work properly. Don’t get lured by the cheaper pricing offered by those who sell hearing aids online or through the mail. The fact is that, if you have a hearing loss that causes you problems, you need a person offering you continuous care for your hearing health.

Wherever you purchase your hearing aids, ask about the trial period policy and which fees are refundable if you return the hearing aids during that period. Also ask about future service, warranty, and repair.

If you are hesitating to see someone about your hearing loss, read this excerpt from a true story, as told to a doctor of audiology in 2012 and published in a local newspaper (Old Colony Memorial, Plymouth, MA):

I knew I had a hearing problem, but didn’t address the issue for about 15 years. . . . All that changed a month ago when I received a notice from your office about the newest technology in hearing aids. I was a little skeptical at first, but I said “go see what’s new.” I did and I am thankful for that. I was fitted with a demo for each ear and immediately heard the difference. My devices came in about two weeks and now I can hear things I haven’t heard in a long time. I am not afraid to join conversations or talk to people in crowds. . . . It has really made a definite difference in my life. You don’t really understand how hearing loss affects your life until you don’t hear for a while and then suddenly are able to hear. It is truly a relief and people around you notice the difference also. I was fitted for the devices and you can hardly notice them. I’m thankful I took the step and relied on your expertise.

This person’s experience is not an isolated case. People often begin to cry when they receive hearing aids and hear for the first time in a long while the sounds that were once familiar. Having one’s hearing restored can be overwhelmingly beautiful and emotional.

Here is another issue that is relevant for a discussion with your audiologist. Do you have ringing or other noises in the ears? Tinnitus is the perception of sound that has no external source. Some of the common sounds people with tinnitus report hearing are ringing, roaring, hissing, humming, buzzing, and cricket-like sounds. Sounds can stay the same, change, be constant, intermittent, or be heard in one or both ears or in the head. Current theory is that tinnitus is caused by neural activity in the brain and auditory system that has been triggered by, among many possibilities, stress, diet, hearing loss, natural aging, noise exposure, head injury, infections, or side effects from medications. It can also be a sign of other health problems, such as high blood pressure or allergies, so anyone experiencing tinnitus should also consult a medical doctor.

Tinnitus sometimes gets worse over time and in other cases does not. Severe tinnitus can be disabling to some individuals and can lead to depression. Although there is no cure, there are treatments that can alleviate the severity of the condition.

Vision care is as integral to maintaining health as we age as hearing care is. By the time most of us have reached our fifth decade, we are wearing some form of corrective lenses. As we continue to age, we may experience a specific eye disease, like glaucoma, cataracts, macular degeneration, or retinal diseases. (These eye diseases and how they affect vision are described in Chapter 1.) Some vision changes can affect one’s driving: greater sensitivity to glare from oncoming vehicle lights, the sun, or even street lights; greater difficulty seeing clearly at night; having to be closer to street or traffic signs in order to read them; and taking longer to recognize familiar places.

“Low vision” is a reduction in visual acuity to 20/70 or worse that makes everyday tasks difficult. A person with low vision may find it difficult or impossible to read, write, go shopping, watch television, drive a car, or recognize faces. A deterioration of your vision doesn’t mean that you have to give up certain activities; it just means you may have to find new ways to do them. (See Chapter 8 for visual assistive tools.)

The National Institute on Aging recommends that you have your vision checked every one to two years if you are 65 or older. You may see one or more specialists in getting your eyes checked. The following explanation of terms will be helpful.

An optometrist (doctor of optometry, O.D.) is not a medical doctor but trains for four years beyond a bachelor’s degree in advanced courses in health, math, and science. As part of their graduate curriculum, optometrists concentrate specifically on the structure, function, and disorders of the eye. They also study general health, anatomy, physiology, and biochemistry, so they have an understanding of how a patient’s overall medical condition can relate to eye health. Some optometrists specialize in geriatrics (care of older persons). An optometrist must be licensed by the state to practice and must earn continuing education credits to be able to renew licensure.

An optometrist conducts comprehensive eye exams, including screening for glaucoma, cataracts, and retinal diseases like macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy. When an optometrist identifies any of these concerns, he or she will refer the patient to an ophthalmologist (see below) for specific treatment and care. An optometrist also prescribes corrective lenses and can fit people with eyeglasses or contact lenses.

An ophthalmologist is a medical doctor who specializes in health of the eye. Ophthalmologists are trained to provide the full spectrum of eye care, from prescribing eyeglasses and contact lenses to diagnosing eye diseases and performing complex and delicate eye surgery. They may also be engaged in scientific research.

An optician is a professional who makes eyeglass lenses from a prescription supplied by a doctor of optometry or an ophthalmologist.

When you get new corrective lenses, it may take some time to adjust to them. As indicated in Chapter 2, new vision correction can sometimes become a risk factor for falls. If you don’t adjust within a few days to a week, let the doctor know. There could be an error in the prescription, in the positioning of the lens in relation to your eye, or in how the lenses were made.

In Chapter 2, on falls, I stressed the importance of keeping your feet in good condition and explained how feet can affect balance and gait. Another kind of doctor you might see is a podiatrist. Podiatrists are medical doctors who specialize in care of the feet, ankles, and lower legs. Podiatrists must have a medical degree (DPM, doctor of podiatric medicine) and must be licensed to practice. Often podiatrists are consulted for routine care only when a patient has a disease, like diabetes, that affects peripheral sensation. But many older people have trouble taking good care of their feet for a variety of reasons, including one as simple as no longer being able to reach their feet. If this is true for you and your feet are otherwise healthy, consider having your toenails cared for at a reputable salon or spa that gives pedicures. However, if you have any systemic disease, like diabetes, or have sores on your feet or legs, or if you are concerned about your feet for any reason, consult a podiatrist first.

In 2004, Kavita Ahluwalia, D.D.S., M.P.H., of the School of Dental and Oral Surgery at Columbia University in New York, wrote in a professional publication about her concern for oral care among aging Americans. She expressed her feeling that we had failed, as a society, to provide quality and accessible dental care for our older population. In the pre-fluoride era, she noted, adults routinely lost all or most of their teeth by midlife. Although today most seniors have retained most of their teeth, they are at increased risk for periodontal diseases, which are associated with chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular diseases, and diabetes. Given that the number and proportion of seniors in the population is increasing, the situation is likely to get worse over the next several decades.

Good oral care not only improves the condition of the mouth but also improves overall health and well-being. We have already discussed the role of teeth in eating, chewing, and choking prevention (see Chapter 5), but, as Dr. Ahluwalia points out, oral diseases and dysfunction can also affect speaking and social interactions. Based on what we know of the importance of social interactions to overall health, the consequences of bad oral care could also include increased isolation and depression.

Dr. Ahluwalia recommended these steps to address the situation.

First, the financing and provision of oral health care must be integrated with the mechanisms used to ensure overall health and well-being for the elderly. Second, because seniors are more likely to visit a physician than a dentist, it is imperative that primary care providers and geriatricians be educated about the medical, functional, emotional, and social consequences of oral diseases and dysfunction and that they provide regular screening and preventive education for dental diseases. Third, the daily caretakers of homebound and institutionalized elderly—nurses, home care workers, and nurses’ aides—need improved oral health care education and training. Fourth, quality assurance measures used by organizations that provide care for seniors ought to address oral health and function.

Finally, she noted that the dental community must recognize that managing oral diseases in older people poses specific challenges, which means that we must create new options for delivering improved oral health care to older people.

Most of these suggestions are aimed at health care policy makers, but there are personal policies we can follow as individuals to take care of our teeth. Visit your dentist, every six months, ideally. When in doubt, ask for instruction in proper brushing and flossing technique and frequency. Dental hygienists gladly give such guidance; they know how beneficial good dental habits are.

Whenever you see any type of doctor, try to think about your health as whole mind–whole body health. The more doctors know about your lifestyle, illnesses, medications, and dietary and exercise regimens, the better they will be able to diagnose your problems and treat you. And the healthier you are, the safer you will be.