So far in this book I have talked about specific types of injuries and how and where they are most likely to happen. In the first part of this chapter I change the perspective; I start with the environment and discuss hazards and injuries by location—room by room. You can use the information to check for hazards in every room in your home or that of someone about whom you are concerned. Much of the information will sound familiar. If you are concerned about someone who has Alzheimer’s disease or a related dementia or suffers from cognitive impairment of any kind, take note of the additional safety measures described for them, which are recommended by the National Institute on Aging.

The second part of this chapter describes the range of assistive and safety devices that are available for use in and around the home. Assistive devices are tools to help make your life easier. For example, to assist people with vision loss, there are phones with large numbers. Safety devices help reduce the risk of injury. For example, a device called a mixing valve controls the temperature of water delivered at a faucet to minimize the risk for scalds.

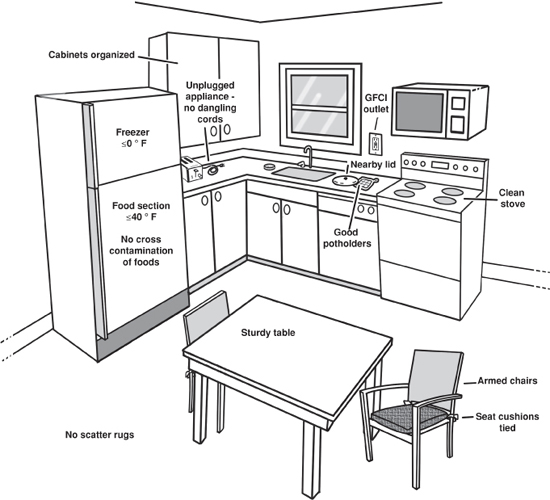

The key safety concerns in the kitchen are falls, burns, and food-borne illness. To prevent falls in the kitchen, take a look at how cabinets are organized and decide if rearranging them would make it easier to reach everyday items without using a step stool. Do you have or need reaching tools (see Figure 8.3)? Check out table and chair design and placement, and look at the flooring. To prevent burns, examine the stove, the oven, the microwave, and countertop cooking appliances like toasters, toaster ovens, and coffee pots. Preventing food-borne illness involves some simple steps like checking the fridge for correct temperatures and spoiled foods, and reviewing good food wrapping and separating techniques. It also means checking non-refrigerated foods: discard any bulging cans and any dry goods (like flour and sugar) that have been infested with or contaminated by bugs, worms, or other critters, or contaminated by droppings from these pests.

Figure 8.1. Kitchen: injury prevention tips

Start with the kitchen cabinets. Are the dishes and glassware used most often located within easy reach? Are the foods used most often within easy reach? Would grouping the foods by type make sense, for example, all cereal products together, or grouping by meal, for example, oatmeal, breakfast bars, teas, and coffee together? There is no one right way. What matters is arranging foods and plates and cutlery so you can get what you need easily and without climbing.

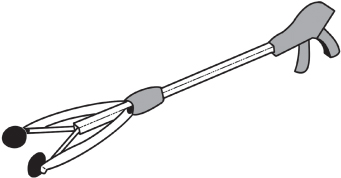

How do you reach things that are out of arm’s reach? A low stool with no hand support may or may not offer enough stability. A kitchen stool (like a barstool) or chair is not a good option, because the step height is too high (it’s awkward and unsafe to climb up onto a barstool or chair). Also, a chair or tall stool may be unstable; the legs may be uneven, causing it to wobble. When you need climbing help, you should use a sturdy step stool that has a handrail running along the sides and extending vertically to create a handle to hold on to while you use the stool (Figure 8.2). If something is positioned just a little bit out of reach, a reaching tool may be useful (Figure 8.3).

Figure 8.2. Well-designed step stool

Do the kitchen chairs have arms? Arms can help people get into or out of chairs. If the chairs have removable cushions, be sure they are securely in place, either held by ties to the back of the chair or kept in place by a nonslip surface on the bottom of the cushion. Slippery, unsecured cushions can slide off a chair and take with them the person who is trying to sit down or get up. Does the kitchen table have four legs or is it a pedestal table, with a center support? Pedestal tables can be unstable; if someone leans heavily on one edge, for instance when rising from a chair, a center-support table can tip over.

Next, take a look at the floor. Are there scatter rugs? It’s best to remove all scatter rugs. Alternatively, place a foam nonslip pad underneath rugs. Clean up any spills right away; it is easy to get distracted when you are busy, and a wet floor is an invitation to fall. Have paper towels handy for cleaning up spills. Don’t wax floors, because waxing makes them slippery. If you expect to be in the kitchen during the night, install a night light or leave a low-level light on.

Let’s start with the stove. Stay with food while it’s cooking. Forgotten items on the stovetop are a leading cause of house fires. Be prepared and keep a pot cover handy in case of a stovetop fire. When you are cooking, wear clothing that has snug fitting or short sleeves, rather than loose, flowing, or dangling sleeves. Clean the stovetop after use to prevent grease buildup, because grease can catch fire.

Keep several good potholders on hand, not frayed or thin ones. Because containers and foods can heat unevenly in the microwave, and because some containers get hot, don’t just grab an item from the microwave without first testing how hot it is to the touch. Use potholders, when needed, to take foods from the microwave, and use care to avoid spilling hot foods or liquids as you carry them from the microwave. If you know that you have lost sensitivity in your fingers, always use potholders when handling anything that might be hot. An extra second or two isn’t much to spend to avoid a burn.

Unplug electrical countertop appliances after use. Check to be sure the cords of countertop appliances do not hang over the counter edge, both when appliances are plugged in and when they are unplugged. An inadvertent tug on a dangling cord can bring down an appliance and its hot contents. To reduce the risk of shock, upgrade to GFCI-equipped outlets if there are none. GFCIs (ground fault circuit interrupters), discussed in Chapter 3, should be used wherever water is used nearby.

Never cook while using medical oxygen.

First to the fridge! Make sure the refrigerator compartment is set to 40°F or colder and that the freezer compartment is set to 0°F or colder. A refrigerator thermometer, carried by most supermarkets, will help you check the temperature. Go through the contents of the refrigerator, checking for leaky wrappings, items that are past their expiration dates, spoiled foods, and cross-contamination. Cross-contamination can occur when uncooked foods, especially raw meats, come into contact with ready-to-eat foods, that is, foods like fruit or salad that will not be cooked before they are consumed. Cross-contamination can happen during food preparation or in the fridge when food is not wrapped and sealed properly. Rewrap foods as necessary and discard outdated and spoiled foods. (Chapter 4 covers food safety in detail.) If necessary, clean the fridge, using a solution of baking soda and warm water on inside surfaces, and washing removable bins and shelving in warm soapy water.

Then review non-refrigerated foods, discarding products with evidence of contamination or spoilage. Check the dates on canned goods. You might want to rearrange canned goods so that you are sure to consume those with the nearest best-by dates first.

If a person in the house has Alzheimer’s or another dementia, consider these additional safety precautions for the kitchen:

• Cover or remove knobs from the stove or install an automatic shut-off switch. Safety devices made to protect children usually work to protect adults with dementia.

• Install childproof door latches on storage cabinets, “junk drawers,” and drawers containing breakable or dangerous items, like skewers. Be aware that a person with dementia may eat small items such as matches, hardware, and erasers, not understanding what they are.

• Lock away all household cleaning products, knives, scissors, blades, small appliances, and anything valuable.

• If drugs are kept in the kitchen, store all drugs, whether prescription or nonprescription, in a locked cabinet. If you keep alcoholic beverages in the house, they should also be behind a locked door.

• Remove from the house entirely any artificial fruits or vegetables and food-shaped kitchen magnets. A person with dementia may not be able to recognize that they aren’t edible. Eating magnets can be particularly dangerous.

• Insert a drain trap in the kitchen sink to catch anything that may otherwise become lost or clog the plumbing.

• Disconnect the garbage disposal. People with Alzheimer’s or dementia may place objects or their own hands in the disposal.

The key concerns in the bedroom are falls and burns from heat sources, like space heaters and heating pads. For people who use bed rails (see Chapter 5), there is the additional concern for suffocation and strangulation, although these injuries are rare.

Remove scatter rugs or place a nonskid pad underneath them. Consider installing wall-to-wall carpeting in the bedroom. Use sheets and blankets that fit the bed, and avoid silky-textured sheets, bedspreads, and quilts, which are slippery and can shift and become a tripping hazard or cause a person to slide onto the floor when trying to sit on or get off the bed. Make up the bed soon after getting up.

Figure 8.4. Bedroom: injury prevention tips

Remove tripping hazards, such as electrical cords, newspapers on the floor, and shoes left lying around. Create a clear, well-lit path from the bedroom to the bathroom and down any adjoining hallway. Install night lights that automatically come on in the dark and turn off at daylight. Keep a working flashlight on or in a nightstand.

If you live with someone who needs supervision and does not sleep in the same room with you, consider using an intercom device (such as a nursery monitor) to alert you to any noises indicating falls or a need for help during the night. Keep a telephone by the bed.

If you use a portable electric or fuel-burning space heater, be sure it is at least three feet away from fabric or any other material that might burn. Fuel-burning heaters (for example kerosene or propane heaters) are not recommended for bedrooms because they have an open flame and generate carbon monoxide. Regardless of where electric or fuel-burning heaters might be in a house, it is wise to put them out before going to bed. Doing so prevents not only burns and fires but potential carbon monoxide poisoning. If a person has Alzheimer’s or another dementia, remove portable space heaters from the person’s room.

Keep the settings on electric mattress pads, electric blankets, and heating pads low when in use, and turn them off for the night just before you get into bed. It’s too easy to fall asleep and forget to turn these products off. Some but not all such products have automatic shut-offs.

Never smoke in bed. If a person with dementia smokes in the house, check upholstered chairs where the person has been sitting for smoldering cigarette butts and warm ashes, and if you can, make smoking in the bedroom off limits for that person.

If you are considering using a hospital-type bed with rails and/or wheels, read the Food and Drug Administration’s up-to-date safety information at www.fda.gov for entrapment prevention. At the time of publication, the direct link was: http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/GuidanceDocuments/ucm072662.htm.

Also see Chapter 5, Figure 1, which illustrates the potential bed rail entrapment locations.

The key concerns in the bathroom are falls, scalds, drowning, and electrocution. The key preventives are some strategically placed safety and assistive devices, increased hazard awareness, and monitoring of persons who need supervision. Chapters 2 and 3 have some additional tips.

Install grab bars in the tub and shower and wherever they will be helpful with maintaining balance while standing and while changing position between sitting and standing. A grab bar in contrasting color to the wall is easier to see than one that matches the wall. If standing in the shower is not an ideal option, use a plastic shower stool. A handheld shower head makes bathing easier for both standing and seated positions.

The height of the step into the shower or tub should be easy to navigate. Consider low-edged alternatives to traditional bathtubs and edgeless entries for showers.

Use an elevated toilet seat if a household member has trouble getting up and down from the toilet, because a higher toilet seat will make this process easier. Many seats—elevated or not—are equipped with handrails. If your toilet seat does not have handrails, install grab bars beside the toilet, because support is always welcome. Towel racks are not grab bars. They are not designed to support an adult’s weight and can be pulled right out of the wall.

Use washable wall-to-wall bathroom carpeting or nonskid mats at the sink and tub to prevent slipping on wet tile floors. If the shower or tub does not have a nonslip surface, use a nonskid mat there as well.

Figure 8.5. Bathroom: injury prevention tips

Install night lights both inside the bathroom and along the path to the bathroom.

Consider using an intercom device (such as a nursery monitor), so that you can be alerted if someone falls or needs help.

Adjust the water heater setting to 120°F. If the water heater has a text indicator (warm to hot) instead of numbers, you can test the water at the bathroom faucet using an instant-read cooking or bathwater thermometer and make adjustments to the water heater dial as needed. Water at 130°F will scald instantly. Consider having a plumber install mixing valves in the shower, tub, and sink to maintain a safe water temperature at the faucet. Consider covering the faucet handles so that a person with dementia can’t turn on the hot water and get scalded (this approach is often recommended for bathing young children). Monitoring such persons while they bathe is a wise precaution.

Drowning can be a risk for all elderly people, but if someone has a heart condition, extra care should be taken during tub bathing. Stay with the person or just outside the bathroom, engaged in conversation with the person.

To avoid electrocution in the bathroom, never use or allow others to use any electrical appliance while someone is in the bath or shower. Unplug electrical appliances after use; a plugged in appliance in the “off” position still conducts electricity! Put hairdryers and other electrical appliances away when you are done; don’t leave them lying by the sink. Be sure that outlets around the sink are equipped with GFCIs (ground fault circuit interrupters) (see Chapter 3).

If a person with Alzheimer’s or other dementia lives in the house, remove portable electrical appliances from the bathroom and cover electrical outlets to reduce the risk of electrocution. If men use electric razors, have them shave outside the bathroom, away from water. To prevent poisoning, remove cleaning products from under the bathroom sink or lock them away.

Finally, remove or disable the lock on the bathroom door so that if someone inside needs assistance, help will not be locked out.

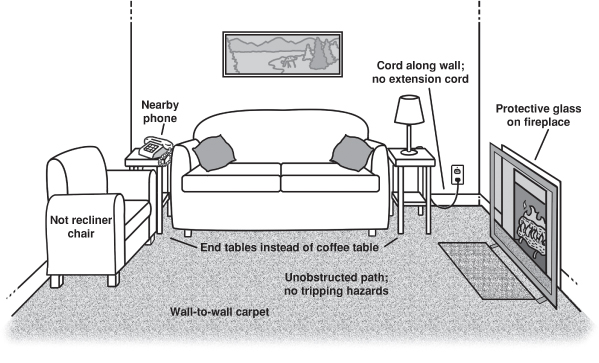

The key concerns in the living room are falls and fire. To prevent falls, remove tripping hazards and glass coffee tables. To prevent fire, minimize the use of extension cords, be vigilant when using candles, and control fires in fireplaces and woodstoves.

Figure 8.6. Living room: injury prevention tips

Remove scatter rugs, runners, and throw rugs, or use nonslip pads under them. Repair or replace worn carpet. Clear all pathways of electrical cords, and make sure cords run along the wall and not under carpeting. If there is a telephone other than a cell phone, put it in a convenient place and make sure its cords are not in the walking path. Set the answering machine to respond after the least number of rings. This way you can be sure that the call will be promptly answered, and you will not be tempted to get up and race to answer a phone that keeps ringing.

Choose chairs that are easy to get into and out of. Recliners are not recommended for elderly persons, because they are not easy to get into or out of. Arrange furniture so that walking does not pose the challenge of an obstacle course, and keep floors clear of clutter. A magazine on the floor can cause someone who steps on it to slip and fall. Look around to see what you might land on if you did fall. Install protective caps on the corners of coffee tables to prevent or minimize fall-related injuries. Replace glass-topped coffee tables with tables made of other material; if a person falls onto a glass table, there is the possibility for a severe laceration from broken glass. For that reason and for ease of movement, you may wish to opt for end tables instead of a coffee table.

To reduce the risk of someone’s walking into or through glass, place decals at eye level on any sliding glass doors, picture windows, and furniture with large glass panels, so people can easily see and recognize the glass pane.

Put out candles when you leave a room. Do not have candles burning in several rooms simultaneously. Monitor fires in fireplaces and woodstoves. Never use an accelerant (a flammable liquid) to start or fuel a fire; use only the intended fuel (wood) and newspaper and kindling or a commercial starter log to get a fire going.

Do not leave a person who has dementia alone with an open fire in a fireplace. Consider alternative heating sources. Most fireplaces (including gas ones) and space heaters can get very hot, posing a burn hazard, so consider a protective guard. Do not leave matches or cigarette lighters sitting out in view of persons with dementia.

The key concern in the laundry is for people with dementia. The best way to prevent injuries is to keep such persons away from laundry facilities. Keep the door to the laundry room locked if possible. Lock all laundry products, including laundry pods, in a cabinet. Laundry pods are individually wrapped single-use detergent packets that are colorful and may resemble candy. Children have eaten these pods, thinking they were candy. An adult with cognitive limitations could make the same mistake. Remove large knobs from the washer and dryer if the person with dementia tampers with machinery. Close and latch the doors and lids to the washer and dryer to prevent objects from being placed in the machines. Child safety locks are available for washers and dryers.

The key concerns in these areas are carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning, fires, and tool-related lacerations or amputations.

Never run a generator indoors or in a garage. Generators must be placed outdoors, well away from doors and windows to the home. Store all potentially toxic products (fertilizers, paints, cleaners, etc.) in their original containers and keep them well sealed. See Chapter 4 for further information.

Keep flammable materials, such as paint thinner and glues, tightly sealed. Store them well away from appliances that have a pilot light, preferably in a shed or out building. Never store gasoline in the basement or garage. Always store gasoline in a shed or out house not connected to your main home. See Chapter 3 for much more information about fire prevention.

Lock all garages, sheds, and basements if possible. Within these places, keep all potentially dangerous items, such as tools (power and manual), tackle, machines, and sporting equipment either locked away in cabinets or in appropriate boxes or cases. Keep all toxic materials, such as paint, fertilizers, and cleaning supplies, out of view. Either put them in a high place or lock them in a cabinet.

Secure and lock all motor vehicles. Consider covering vehicles, including bicycles, that are not frequently used. This may reduce a cognitively impaired person’s thoughts of leaving.

If the person is permitted in the garage, shed, or basement, accompany him or her, and make sure that the area is well lit and that stairs have a handrail. Keep walkways clear of debris and clutter.

The following reminders for general safety improvement throughout the home focus on the added safety provided by adequate lighting, working alarm systems, knowing what to do in an emergency, and having an exit plan in case of fire.

Make sure that hallways and stairways are well lit. Install lighting both at the top and at the bottom of stairs and at both ends of hallways. Check all rooms for adequate lighting.

Ideally, stairways will have two handrails, but all stairways should have at least one handrail that extends beyond the first and last steps. Always hold the handrail when going up or down stairs. If possible, stairways should be carpeted or have safety grip strips.

Avoid clutter, which can create a tripping hazard, distraction, and confusion. Throw out or recycle newspapers and magazines regularly. Keep all walking areas free of furniture.

Install smoke alarms and carbon monoxide detectors near all sleeping areas on all levels of the home. Check that they are in working order and at least twice a year—for instance, when you change the clocks for Daylight Saving Time and back again—change the batteries in the alarms. Schedule a visit by a representative from your local fire department to inspect your home to be sure it meets local safety codes for these devices.

Do not allow smoking around home-use oxygen. The person wearing the oxygen should keep at least ten feet away from any flame or heat source. Never cook while using oxygen. Post a sign on the door or window visible to those entering indicating that oxygen is in use and that smoking, sparks, and open flame are prohibited.

Figure 8.7. Stairway: injury prevention tips

Display emergency numbers and your home address near all telephones. The number to call for fire and ambulance is 911. The number to call for poison centers is 800-222-1222.

Create a fire escape plan and practice it. (See Chapter 3.)

Remove all poisonous plants from the home. Check with local nurseries or poison control centers for a list of house plants that if eaten or chewed on would make a person sick.

Because persons with dementia may not be able to take telephone messages and can become victims of telephone exploitation, turn telephone ringers off or set them to low if the person will be home alone. Put all portable phones and cell phones and equipment in a safe place so they will not be easily lost. Hide a spare house key outside, in case the ill person locks you out of the house.

Keep all medications (prescription and over-the-counter) in a locked drawer or cabinet. Keep thin plastic bags (for example dry cleaning bags) out of reach because they could pose a suffocation hazard.

Keep fish tanks out of reach. The combination of glass, water, electrical pumps, and potentially poisonous aquatic life could be harmful to a curious person with Alzheimer’s.

While we are discussing general home safety, gun storage requires special attention. More older persons than younger persons own a gun. A 2004 survey showed that 27 percent of those 65 and older personally owned a firearm. That means that quite a few more people live in a home that has a gun in it. In 2011, 37.2 percent of Americans aged 65 or older lived in a home with a firearm.

Fear of crime is a driving factor in gun ownership among the elderly, in spite of the fact that they are far less likely than are younger people to be to victims of violent crime. Ironically, among older people, gun ownership increases the risk of violent death, including suicide and homicide-suicide. A gun is the most common means of suicide in the United States, and the rates of firearm suicide are highest among people 75 or older. Suicide in this group is less likely to be related to mental health problems and more likely to be related to physical health. According to 2010 data from the National Violent Death Reporting System, with sixteen states reporting, in 93 percent of homicide-suicide cases in which a victim was 65 or older, an intimate partner was involved. In some of these cases, a man killed his wife or partner, and then himself, in a “mercy killing” to end a long illness.

For people with Alzheimer’s or other dementia, gun ownership or access is particularly problematic. Memory loss, confusion, aggressive behavior, and personality changes put them, and their caretakers, at great risk. The most effective measure to keep all persons safe is to remove all guns and other weapons from the home. If a person chooses to keep a firearm in the home, the gun must be stored safely. Safe gun storage means keeping guns and ammunition separate; place the unloaded gun in a locked box, out of sight, and store ammunition in another locked box separate from the gun.

As with the interior of the home, falls are the key concern as one approaches the exterior of a house. To prevent such falls, make sure that exterior steps are solid, and minimize slippery, rocky, or uneven pavement. Sufficient lighting is also essential.

Eliminate uneven outside surfaces and clear walkways of hoses and other tripping hazards. Keep hoses on a hose wheel or rack. Prune bushes and foliage well away from walkways and doorways. Steps should be in good repair, easily negotiated, and equipped with a handrail. Textured steps help prevent falls in wet or icy weather. For added visibility of steps, mark the edges with bright or reflective tape or paint.

Make sure outside lighting is adequate. Light sensors that turn on lights automatically as you approach the house may be useful. They also may be used in other parts of the home. Photosensitive lights turn on automatically when it gets dark.

Placing a chair near the door you usually use can be helpful. You may be tired from an outing or you may be juggling bundles as you return home. In either case, it is nice to have a place to rest right as you get inside. If there is space, place a seat or bench near the entry door so you can set packages down—or sit down yourself, if you need to—as soon as you get home. Such an arrangement enhances safety as well as comfort.

Restrict access to a backyard swimming pool, spa, or hot tub by surrounding it on all four sides with fencing equipped with a self-latching gate that opens outward. Check your local building codes for requirements. Adequate fencing also serves to prevent access by neighborhood toddlers and young children, who are at high risk of drowning in backyard pools. If a side of the house is used to complete the fourth side of fencing (as shown in the illustration), install window and door alarms to alert you when someone exits the house into the pool area. When the pool is not in use, cover it with a safety cover. When it is in use, supervise closely.

In addition, if a person in the home has Alzheimer’s or another dementia, remove the fuel source and fire starters from any backyard grills when not in use and supervise use when the person is present.

Figure 8.8. Exterior: injury prevention tips

Many assistive devices not only assist—they also increase safety. A device that allows you to reach and retrieve objects from high shelves, for example, both helps you quickly reach something you want and keeps you from climbing onto a chair or stretching in a way that throws you off balance. There are also devices designed specifically to increase safety, for example fall prevention devices. The assistive devices described below are arranged by the sense that they help (hearing, vision, and so on). The safety devices are categorized by the hazard they help avoid. These lists are by no means exhaustive, as the number and types of products on the market are extensive and growing, but they will give you an idea of the kinds of products available. When you consider the options of assistive technology, it could be useful to separate the options into high-tech and low-tech solutions. High-tech devices tend to be more expensive but may be able to assist with many different needs. Low-tech equipment is usually cheaper but less adaptable for multiple purposes.

Before purchasing any assistive technology, older adults should carefully evaluate their needs. A team approach is often most helpful. For example, an older person who has trouble communicating or is hard of hearing should consult with his or her audiology specialist, a speech-language therapist, and family and friends. Together, this team of people can identify the problem more precisely and can help select the most effective devices available at the lowest cost. A professional member of the team, such as the audiology specialist, can also educate and coach the older person and other family members in how to use the devices properly.

These recommendations are based on information from MedlinePlus (nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/assistivedevices.html), a plain-language medical website for patients and their families and friends.

Assistive listening devices (ALDs) are intended to assist people with hearing loss. They typically work by magnifying sounds, selectively directing sounds to the person, or replacing a sound with a visual or tactile stimulus. Examples of common products include alarm clocks and watches that either are very loud or vibrate at the set time, door bells that trigger a light inside the home to come on, smoke and carbon monoxide alarms that either sound at a specific pitch the person can hear or send out a light signal, phones equipped with TTY, which is a text telephone or teleprinter specifically designed for text communication over a public telephone network, captioned telephones, which utilize speech recognition technology to display a text version of the ongoing conversation, and answering machines that make messages louder and slower.

Other assistive hearing devices include looping systems, tele-coils, TV ears, and Bluetooth technology. Looping systems generate a magnetic signal and are designed to work with public address systems in places like auditoriums and churches. Looped rooms are wired so that any sound from a public address speaker goes directly to headphones a listener puts on or directly to a person’s hearing aids if they are equipped with a telecoil, also known as a T-coil. The loop system eliminates the interference from background sounds, so the listener hears the selected sound with great clarity.

A telecoil, or T-coil, is a device that can be incorporated into a hearing aid. It is a tiny coil of wire around a core that responds to changes in the magnetic field. T-coils are available for most behind-the-ear hearing aids and for some in-the-ear hearing aids. Your audiologist can help you learn about and consider these devices. (Audiology and hearing aids are discussed in Chapter 9.)

“TV ears” and other wireless TV listening devices enable people with a hearing loss to listen to television at a volume comfortable for them without having to make the volume uncomfortably loud for other people. These devices consist of a transmitter connected to the television and a receiver built into wireless headphones the person wears. The person controls the volume from the headset.

Bluetooth technology was invented by the Swedish company Ericsson. The inventors wanted to use Bluetooth as a collaborative tool to connect multiple electronic devices so as to share information quickly over the air. In 1998, a group of companies formed the Bluetooth Special Interest Group, an organization in which no one individual “owns” Bluetooth technology and all members work together to further develop and maintain the technology. Bluetooth technology for hearing assistance allows you to connect (called “pairing”) wirelessly, via a device called a “streamer,” to your phone, television, or other audio device, and receive exceptionally clear sounds directly to your hearing aids.

Low vision, defined as a level of vision of 20/70 or worse that cannot be corrected with conventional glasses, is not a normal part of aging, but it does primarily affect the elderly. Most people develop low vision because of eye diseases. Among the aging population, common causes of low vision are macular degeneration, glaucoma, and diabetic retinopathy. People with these eye diseases have some useful sight, but their vision loss affects their ability to read, drive, and perform other daily activities. For example, a person with low vision may not recognize images at a distance or may not be able to differentiate colors of similar tones. (See Chapter 1 for a description and illustration of the effects on vision of these conditions.) There are many tools available to assist people with low vision. Many books and other materials are published in large print versions. A wide variety of magnifiers is available: handheld magnifiers, magnifiers that clip to your eyeglasses or fit over your head, desktop magnifiers that project the text onto a screen, video magnifiers (closed circuit TVs), software that magnifies computer images, and specialized camera products that send images to a viewing screen or to your computer. Other products communicate verbally. These include products that scan text and read it back to you; talking clocks, wristwatches, and calculators; and talking global positioning system (GPS) devices that tell you the names of streets, intersections, and landmarks as you walk or ride along.

Many products help with balance. As discussed in Chapter 2, although people using walkers and canes face particular risks of falling, these assistive devices allow people to remain mobile, which is extremely important to a person’s mental and physical health. The key to safer use of these aids is learning how to use them correctly. They must also fit you in terms of height and comfort. If you are buying one of these products on your own (rather than getting one directly from a health care professional or facility), get a knowledgeable person from a medical supply store to assist you with both the fit and instructions on how to use it properly.

Grab bars provide assistance, whether you are standing still or transitioning between standing and sitting. They can be installed in the shower or tub, and on any wall. They are an easy and effective aid. Because bathrooms present numerous challenges to balance, you may have to consider making some structural changes in your bathroom in addition to installing grab bars. Stepping into a shower or tub may once have been easy, but the step height may now be a bit challenging—and dangerous, if it throws you off balance. You can buy bathtub door inserts that fit onto your existing tub, or you can buy a walk-in tub. These devices eliminate the need to step over a high side. For a less costly and simpler solution, you can buy a transfer bench, which straddles the tub. You sit down on the side of the bench outside of the tub, then slide over to the portion inside the tub. Various designs are available.

You can also buy shower stalls that are flush with the floor or have only a slight (half-inch or so) rise to floor level, for easy entry. These stalls make it easy for someone in a wheelchair to use the shower. Once in the shower or tub, bath seats can be very useful. Handheld shower heads are a better option than fixed shower heads, which pour water from overhead onto the person.

Toilet seat height can be a problem. A higher seat is easier to get down to and up from. You can have a taller toilet installed, but an easier, cheaper solution is to buy a raised toilet seat that fits onto the toilet you already have. Styles with arms offer added balance support.

Strength assistance products abound. They include aids for cooking, eating, gardening, grooming and more. Examples include jar openers, angled kitchen and garden utensils that keep your wrist in a neutral position, doorknob covers that help with gripping and twisting, and easy-grip scissors. There are also exercise products designed to strengthen hand grip.

Fine motor skill and flexibility aids help with getting dressed. There are zipper pulls, button hooks, dressing sticks, sock aids, long-handled shoehorns, and so on. In addition, there is adaptive clothing, specifically designed to make dressing easier for yourself or for the person helping someone get dressed. Examples include pants with long zippers extending down the legs on both sides, shoes with Velcro® instead of laces, and tops that open in the back, allowing the person to easily put both arms into sleeves simultaneously.

Fall prevention aids include socks with textured grippers on the bottoms, nonslip mats, and slip-resistant stair and floor tape. Tools like reach bars (see Figure 8.3) that help you to reach items from a standing or seated position rather than by climbing reduce the chances of falling off step stools or chairs and of overextending your reach and losing your balance.

Chapter 5 discusses the pros and cons of using bed rails to prevent falls from beds.

Mixing valves, installed by a plumber, ensure that the temperature of the water delivered at the faucet is not hot enough to scald. This solution takes away the danger of a surge of hot water and of mistakenly turning on excessively hot water. Faucet handle covers, which are often used to protect children, also work for older adults with dementia.

Keeping your medications organized will reduce the chances of overdosing or underdosing. Pill organizers are readily available at pharmacies, as are dosage dispensers (for example, for a liquid drug) and pill cutters. If a person cannot safely take medications on his or her own, buy a locking cabinet to keep the medications in; this will avoid the dangers posed by unsupervised access.