You would think that poisoning is a danger only for children, because most adults know better than to consume poisonous substances. But any substance can be poisonous if enough of it enters the body, and adults do get poisoned—as the public health data on poisoning attest.

The CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) defines a poison as any substance that is harmful to the body when ingested (eaten or drunk), inhaled, injected, or absorbed through the skin. Poisonous substances can include prescription and over-the-counter drugs, illegally used drugs, gases, chemicals, vitamins, and food. Poisoning is any harmful effect of being exposed to a poison.

The kind of damage caused by a poisoning depends on the poison, the amount taken, and the age and underlying health status of the victim. Some poisons are not very potent and cause problems only with prolonged exposure or repeated ingestion of large amounts. Other poisons are so potent that just a drop on the skin can cause severe damage. Some poisons cause symptoms within seconds, while others cause symptoms only after hours, days, or even weeks. Some poisons cause few obvious symptoms until they have damaged vital organs, such as the kidneys or liver, sometimes permanently.

Fortunately, most poisonings among older people cause only minor or moderate ill effects. A small percentage, however, cause serious injury or death. Of nearly two and a half million human exposures to poisons reported to sixty National Poison Centers during the year 2010, about 6.2 percent involved people aged 60 or older. About 0.2 percent of those older victims (232 people) died as a result of the exposure. But those 232 people made up 20 percent of all the reported poison-related deaths that year (232 of 1,146 deaths). Older people are indeed vulnerable to being poisoned.

Although children are more often poisoned by household products, cosmetics, and personal care items, older people are more likely to be poisoned by medications they are taking, whether they are prescription medications or over-the-counter medicines such as ibuprofen, acetaminophen, and aspirin.

What can we do to prevent poisoning of adults? The poison centers report noted that 93.7 percent of poisonings occurred at home, and we know that medications are the most common culprit of adult poisoning, so prevention begins at home with being careful about medications. Approximately 80 percent of the poisonings reported in 2010 were the result of ingesting a substance, rather than being exposed to it by other routes. Ninety percent of cases involved a single substance rather than multiple substances, and the most common substance reported was analgesics—pain killers.

This chapter focuses on medication poisoning, carbon monoxide poisoning, and food poisoning. Let me note right here that if you ever suspect a poisoning, you should immediately call 911 or the National Poison Control Hotline at 1-800-222-1222 for guidance.

The term medicine includes doctor-prescribed preparations, be they pills, liquids, lotions, or whatever, that you have filled at a pharmacy; so-called over-the-counter, or OTC, therapeutic substances of any sort that you can buy without a prescription; and vitamins, herbal preparations, and dietary supplements. You should treat OTC medicines, vitamins, herbals, and dietary supplements the same way you treat medicines that require a prescription. Read the label, choose a substance that is appropriate for your symptoms, take the recommended dose, and follow the instructions for how to take the medicine. For example, if you have a runny nose but no cough, don’t take a product that is for both cough and runny nose. Let your doctor know what OTC medicines you are taking, because they may interfere with prescription medicines you are taking. For example, if you take aspirin for a headache when you are already on a blood-thinning medicine, the blood thinner’s effect will be amplified, because aspirin slows blood clotting. So, don’t assume that just because a medication can be purchased without a prescription it can’t be potentially harmful. This caution applies to herbal preparations, which many people assume can do no harm because they are “natural.” In fact, they may require more care and knowledge on the part of the consumer, because they do not receive the same testing and regulation by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration that other drugs do.

Medicine-related poisonings are frequently caused by human error, such as taking a dose of a medication twice, taking the wrong medication, and taking the wrong dosage. Drug interactions are less common than taking the wrong medication or too much medication, but they are more likely than other medication mishaps to have a serious outcome. Drug interactions can result when the health professional makes a mistake in prescribing or when the patient takes more than one product containing the same ingredient. In the example of blood thinners and aspirin, the health care professional may not know when he or she prescribes a blood thinner that the patient sometimes takes aspirin, or a patient, having heard that aspirin can be helpful in preventing heart attacks, may add the aspirin on his or her own, not realizing it might cause problems with the blood thinner already being taken. Since many older people take several prescriptions (referred to as polypharmacy), they are more vulnerable to poisoning. (Chapter 2 explains the effects of polypharmacy on fall risk.)

Age-related changes in cognitive ability and loss of visual acuity can contribute to errors that lead to poisoning from medicines. If your memory is getting unreliable, you may forget to take a medication or forget that you have already taken a medication. If you have vision difficulties, you may misread a label and take the wrong medication or the wrong dose, mistake similar-looking containers or similar-colored substances and take either the wrong medication or a substance that isn’t a medicine, mistake a hearing aid battery for a pill, or misread a measuring device and take too little or too much medicine.

Changes in fine motor skills can also factor in. People who have difficulty opening packaging (with child-resistant lids, for example) may transfer the contents to an unlabeled container to avoid the struggle. Transferring contents can easily lead to confusion about which medications are which. (And transferring medications or leaving off child-resistant closures can put at risk young children who live in the same household or who visit in the home.)

Recognizing the difficulty that older adults may have with child-resistant closures, the Consumer Product Safety Commission amended the Poison Prevention Packaging Act to maintain the same level of protection for children while at the same time ensuring that most older adults could open the packaging without undue difficulty. Child resistance is tested (by groups of children aged 42 to 51 months old) and now ease of adult opening is also tested (by groups of adults aged 50 to 70 years). A closure is considered child resistant if 85 percent of children tested cannot open it in a given time frame, and a child-resistant closure is considered effective for adults if at least 90 percent of older adults can open the package in a given time frame.

If you are confident that no children younger than 5 years old will be around, you can ask the pharmacy to fill prescriptions using non–child-resistant closures. These usually snap or twist on and off in one easy motion.

Know what prescription and over-the-counter (OTC) medications you take or someone you are caring for is taking. Keep an up-to-date list of all prescription medications, including the dosage, the start date, the stop date, and the prescribing physician. Also keep an updated list of all the OTC medications and dietary supplements being taken, including the dosage, the start date, and the stop date. This information can help identify the problem drug if an overdose occurs. If you bring the list with you every time you visit the doctor, your risk of drug interactions or multiple prescriptions with the same ingredients is minimized. (See Chapter 9 for a sample medication record-keeping chart.)

Keep medicines in their original containers, so that you can identify not only the drug but also the pharmacy where it was obtained and the refill information. If you suspect a poisoning has occurred with that drug, the original packaging will be useful, because it has all the information you will need to report to emergency medical personnel or to a poison control center. If original contents are put into a different container, it’s easy to forget what that substance is and what its medical purpose is.

If possible, use the same pharmacy for all your prescriptions. A pharmacy will keep a record of all your prescriptions and can alert you or your doctor to overlapping medications, contraindications, and potential adverse effects.

Make it a rule always to keep the medicine in the same place (and out of reach of young children). Establishing a routine or habit helps you locate the medicine so you can take it on time. It also minimizes the risk of mistaking a different product for the medication.

It is very important to store medications in a separate place from hearing aid batteries and other small disc or coin-shaped batteries. Hearing aid batteries are exactly the same size as many pills. If a small battery is mistaken for a pill and swallowed, it can lodge in the esophagus or farther down in the gastrointestinal tract where it can cause chemical burns. Surgery might be required to remove the battery.

Take medicines at the same time or times each day. This helps regulate the amount of medicine in the bloodstream, for maximum effectiveness. It also reduces the chance of taking duplicate doses.

Make sure that you are taking the correct dose of each medication. Be sure to read the label. It will tell you how much to take at a time and how many times during the day you need to take the medicine. If you don’t understand how to take the medicine, ask the pharmacist. The pharmacy’s number is always printed on the label, and pharmacists are trained to answer patients’ questions about medicines.

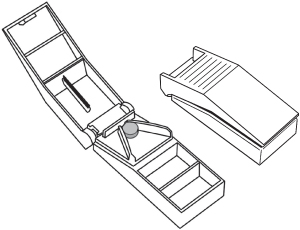

If pills have to be cut, use a pill cutter, which can be purchased inexpensively at any pharmacy. (An example is shown in Figure 4.1.) Cutting a pill in half without a pill cutter is not always easy. Some pills have a score mark on them (a line of slight indentation), which makes it easier to break the pill by pressing down on opposite sides of the line with your fingers, but other pills do not. Given the importance of accurate dosage and the potential for waste if a pill shatters while you are trying to divide it, a pill cutter is a very good investment.

Figure 4.1. Pill cutter (a) open and (b) closed

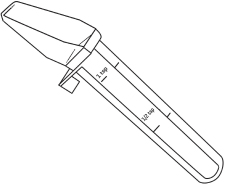

For liquid medication, always use an accurate measuring device. An example of a so-called medicine dropper or medicine spoon is shown in Figure 4.2. These devices are marked with lines indicating the volume, and some have a mechanical device to make sure you pour to the correct line. Ordinary household spoons vary in size and should not be used as measuring devices for medicines.

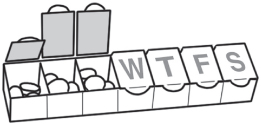

Using a pill planner or organizer can help you keep track of what you need to take when. Various designs are available, in different colors, with different numbers of days (see Figure 4.3 for an example).

Thoughtfully decide who will fill the pill planner. Correct filling of each slot is very important. Someone who understands the dosage requirements and can accurately fill the planner ought to do that task.

The planner should be refilled on a strict schedule. The day for refilling the compartments in the pill planner should be the same each week. There are at least two benefits to sticking to a fill schedule. First, a day’s compartment is never empty when you need it. Second, when pills are running low, you have a trigger for requesting refills from the doctor or pharmacy.

Don’t take a medication that was prescribed for another person. Even if the intent is well-meaning, doing this can create serious problems, including adverse reactions, overdosing, and allergic reactions.

What should you do if you suspect a medication poisoning has occurred? The symptoms of medication poisoning are so varied, depending on the substance, that it may not be possible for a lay person to recognize them. Instead of waiting for signs of illness, if you suspect a poisoning call the National Poison Control Hotline at 1-800-222-1222 for guidance.

If you take someone to the emergency room with suspected poisoning, take with you the suspected substance or substances in their original containers. It would also be helpful to take the complete list of medications the person normally uses.

Carbon monoxide (CO) gas is poisonous. It is also colorless, non-irritating, and has no scent or taste. Those qualities make it an insidious killer—you cannot see it, you cannot smell it, and you don’t realize it is causing you harm. One reason CO gas can quickly harm is that the red blood cells that carry oxygen throughout our bodies prefer carbon monoxide! That means, given the choice, they will select to absorb carbon monoxide over oxygen, depriving the body of the oxygen we need to survive. Thus, exposure to carbon monoxide is extremely dangerous and can be deadly. Symptoms of mild to moderate carbon monoxide poisoning may resemble flu symptoms. They include weakness, dizziness, nausea, and headaches. Symptoms of more prolonged exposure can include vomiting, loss of muscular control, and sleepiness. The most severe outcome of carbon monoxide poisoning is death.

Carbon monoxide is generated when any fuel burns, whether it’s kerosene in a heater, oil or natural gas in a furnace, charcoal in a grill, wood in a fireplace, or gasoline in a car, lawn mower, or generator. That’s why all fuel-burning devices are either designed and intended exclusively for outdoor use or, if intended for indoor use, are installed with a vent that leads outside the house. Electrically operated equipment does not generate carbon monoxide.

We cannot prevent the formation of carbon monoxide. The key to preventing CO poisoning is to make sure that the CO gets outside, into the air, where it can readily dissipate so that it is not available in concentrated amounts for anyone to breathe. With items ordinarily used outdoors, like lawn mowers, there is no real issue because as the CO is generated, it simply dissipates into the air. For items intended for interior use, like heaters, make sure that there is a vent to the outside and that the vent system is kept clean, clear, and in good repair. If the carbon monoxide can adequately vent to the outside, there is no cause for concern.

There is cause for concern when carbon monoxide accumulates, usually in a closed or confined space. If gasoline- or diesel-powered equipment is operated in a space that does not allow the CO to escape to the outside, there is always a risk of CO poisoning. Running a car in a garage is an example. Note that even keeping the garage door open will not safely disperse the carbon monoxide that is generated by fuel-operated equipment running inside a garage.

Carbon monoxide detectors have been developed to alert homeowners if carbon monoxide accumulates inside their home. As of November 2011, carbon monoxide detectors are required in certain residential buildings by 25 states (Alaska, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Rhode Island, Utah, Vermont, Washington, West Virginia, and Wisconsin). Many people do not know that their state has carbon monoxide detector laws, however, and many people do not install a CO detector because they don’t know about the devices or don’t understand how they work. Even if CO detectors are not required in your state, you should install one. They work just like smoke detectors except that, instead of detecting smoke, they alert you when there is too much carbon monoxide in the air. If you have questions, check with your local fire department.

About 20,000 nonfatal exposures to carbon monoxide occur each year in the United States. Carbon monoxide exposures are more likely to occur in winter months than in summer months, and most exposures occur at home. These facts are not surprising because the most common culprits are home heating systems, including furnaces, boilers, and other heaters. Winter storms pose a danger for stranded motorists who can be exposed to motor-vehicle exhaust, which contains carbon monoxide.

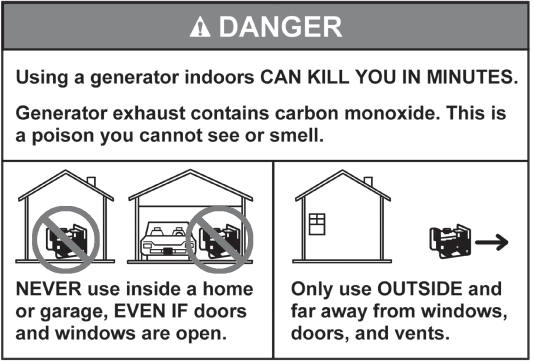

People who use portable generators at home when electricity goes out for any reason are also at risk. Because portable generators have been responsible for so many CO injuries and deaths, the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission requires that a carbon monoxide danger label (see Figure 4.4) appear on generators manufactured or imported after May 14, 2007. Never operate a generator indoors, in a garage, or in a basement. According to one study, more than half of people surveyed in 2005–2006 thought it was okay or weren’t sure whether it was okay to operate a generator in a garage as long as a door was open, and about 40 percent thought it was okay or weren’t sure if it was okay to operate a generator in a basement. Always locate the generator outside, far away from any vents, doors, or windows, so that CO gas does not enter the home.

Figure 4.4. Carbon monoxide danger label required on generators

Adults aged 25 to 34 years had the highest rate of carbon monoxide–related visits to an emergency room, however, those aged 65 or older had higher death rates than the younger age groups. In 2009, 59 people 65 or older died from CO poisoning.

The consequences of carbon monoxide poisoning are also more severe for the older age group. Older people are more vulnerable because they are more likely to have chronic diseases, especially diseases that affect breathing. Also, the symptoms of carbon monoxide poisoning can be harder to recognize in older people because they may already have some of the symptoms of carbon monoxide poisoning, such as dizziness, for other reasons. In addition, older people might not be aware that their heating systems are operating incorrectly. If they are hearing impaired, they may not be able to hear the alarm of a carbon monoxide detector, or if they hear it, they may not know what it means or what to do, because of cognition problems.

Follow the precautions below to avoid this odorless threat:

• Make sure that any fuel-burning device used indoors is intended to be used indoors. Never burn charcoal indoors. Never operate a generator indoors.

• Make sure that any fuel-burning product used indoors, like a fireplace, space heater, or woodstove, has been installed by a skilled and certified contractor and is properly vented to the outside. Make sure that vents and flues are not blocked by animal nests, snow, or anything else.

• Have heating systems (furnaces) and fireplaces checked on a regular basis by skilled and certified contractors.

• Turn off space heaters when you go to bed.

• Never run fuel-operated equipment, including motor vehicles and generators, inside a garage. Even an open garage door will not allow the clearance of dangerous levels of carbon monoxide.

• Install carbon monoxide detectors in your home. Devices made especially for people who are hearing impaired emit visual cues or vibration in addition to sound.

If the carbon monoxide detector goes off, open the windows and go outside. Then call the fire department for guidance.

If a person feels dizzy, nauseated, or headachy after using fuel-driven equipment in a confined space, lead the person outside for fresh air and call 911 for medical help.

Each year, millions of people in the United States get sick from contaminated food. Some food is already contaminated when it is purchased, and some food spoils and becomes contaminated because it is too old or has not been properly stored. Symptoms of food poisoning include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal cramps. Symptoms can range from mild to severe and can start almost as soon as the meal is finished or as long as 72 hours later. For the most part, symptoms last a day or two and there is no long-term damage. In rare instances, food poisoning can be very serious and even result in death. If symptoms persist more than a few days or if the person has a fever or bloody stools, medical attention may be appropriate, especially to treat dehydration or infection. Harmful bacteria are the most common causes of food poisoning, but viruses, parasites, toxins, and other contaminants in food can also make people sick.

Age-related changes in cognitive ability and loss of visual acuity can contribute to errors that lead to food poisoning. Also, changes in the senses of smell and taste, a compromised immune system, malnutrition, and chronic diseases all increase the risk of food poisoning. Someone who is not able to see, smell, or taste accurately may not notice that mold has grown on an item in the fridge or realize that milk or another food has spoiled. (A person whose senses of smell and taste are poor is also at risk for malnutrition, because he or she can’t taste the good flavor of the food and so may eat too little or have an unbalanced diet.)

Other contributors to food-related illness include improper cooking and storage of food and unsafe food handling behaviors, such as:

• Eating undercooked meat or eggs. Because eggs are relatively inexpensive, easy to fix, and generally well liked by older people, many older people eat eggs often, and sometimes they do not take care to cook eggs thoroughly.

• Not washing hands and food preparation surfaces thoroughly and often.

• Cross-contamination during food preparation, by failing to keep raw animal products separate from fresh produce. Cross-contamination happens when harmful microorganisms from uncooked foods (especially meat, poultry, and seafood) are transferred (by your hands, cutting boards, knives, and so on) to foods that are eaten without further cooking (like salad vegetables and fruits).

• Cross-contamination in the refrigerator due to poor or leaky packaging or storing raw animal products in close proximity to fresh produce. A leaky meat package may leak blood onto fresh produce or cheese, for example.

• Not washing fruit before eating it.

• Not refrigerating foods promptly when first purchased or when left over after meals.

• Thawing foods on the countertop instead of in the refrigerator.

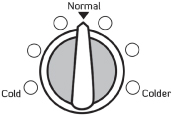

• Keeping the refrigerator set to too warm a temperature.

A study of food safety practices done in England found that most participants had not measured their refrigerator temperature and did not know what the temperature should be. The study also found that the majority of the people had not adjusted the temperature control dial of the refrigerator and instead gauged the “correct” temperature by the feel of foods inside. “Use by” dates were generally well understood but not always adhered to because of difficulty in reading the labels. Items were sometimes purchased near the end of the “use by” date because they were cheaper and then, although people appreciated that these dates related to food safety, the items were kept for up to a month before they were consumed. If such a study were conducted in the United States, I venture to say that the results would be about the same. In fact, a Pennsylvania study of seniors who prepared more than five meals a week at home found that participants used a mix of inappropriate and appropriate practices in cooking, cooling, and thawing foods. Seniors relied on what they had learned in the past about food safety rather than on what is now known about safe food practices.

Food safety involves a series of factors. Observing expiration dates stamped on packages is only one factor. The risk of food-borne illness is also affected by the temperature at which food is stored and the temperature of the room in which it is prepared. Focus your prevention efforts on these practices advocated by food safety experts:

Practice personal hygiene: wash hands and surfaces often.

Shop where you trust the quality and safety of the food; be mindful of expiration dates.

Wash produce before consuming it.

Cook foods adequately: invest in a food thermometer and use it.

Avoid cross-contamination: in the refrigerator, keep foods separate and wipe up drips and spills so that foods do not contaminate each other. Thoroughly wash hands, food contact surfaces (such as cutting boards), sponges, dish towels, and utensils that come in contact with raw animal products.

Keep foods at safe temperatures and consume them promptly: Set the fridge to 40°F or colder. (If there is no digital temperature indicator, buy a refrigerator thermometer to check.) Quickly refrigerate perishables after purchasing, and store all leftovers in baggies or containers that close tightly or wrap them tightly in plastic wrap or aluminum foil. Use masking tape and a waterproof felt-tip pen to label containers and wrapped food, identifying the food and the date you put it in the refrigerator.

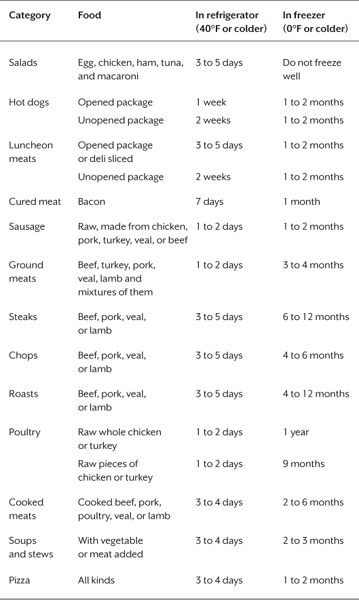

Foodsafety.gov is an online source of information on safe food preparation and handling. The recommended storage times from that website for various foods are listed in Tables 4.1 and 4.2. Note that food kept frozen remains safe indefinitely but that the quality of the food may decrease after the times noted. When freezing meat and poultry, wrap over the original package with foil or with plastic that is recommended for the freezer. Label and date items you freeze. Regularly review the contents of the fridge to discard items whose use-by date has expired. Thaw frozen items in the refrigerator, not on the counter, so that the temperature of the food does not rise to a level that invites bacterial growth.

Store canned foods in a cool, dry place. Never store canned goods under the sink, over the stove, in a damp basement or garage, or anywhere else that may have high and low temperature fluctuations. Canned foods with high acidic content, like tomatoes and other fruits, can be stored for up to 18 months. Low-acid foods, like vegetables and meats, can be kept for two to five years. Most canned goods now have “best by” dates stamped on the can.

Food safety experts offer this additional guidance:

• Generally, foods high in protein, like meat and fish, deteriorate faster than foods high in sugar or sodium. That’s why sugar and salt are used in food preservation.

• Follow food safety temperature guidelines. At room temperature, bacteria grow quickly and food spoils faster. Refrigerate food soon after purchase. Keep your refrigerator set below 41°F and heat foods to temperatures above 140° F. These extremes of cold and heat prevent bacteria from multiplying.

• Take a good look! If you see obvious discoloration, such as green meat or blue spots on bread, throw out that food. Changes in texture are also a sign of spoilage, such as clumpy milk. Other warning signs are packaging with obvious openings or bulges, and cans that are dented, leaking, bulging, or showing rust along any seam.

How you handle food at the store, before it even reaches your kitchen, can affect your risk of food-borne illness. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommends that, when shopping, you select refrigerated and frozen food after you pick up all the nonperishables on your list; that way, the foods that need to be kept cold are out of the refrigerated areas for a shorter time. (Most grocery stores are arranged so shoppers encounter nonperishables first.) Don’t buy meats in torn or leaking packaging, and don’t buy items beyond their “sell by” date or “use by” date.

Table 4.1. Recommended Food Storage Times and Temperatures

Table 4.2. Recommended Storage Times for Eggs

Egg product |

In refrigerator (40°F or colder) |

In freezer (0°F or colder) |

Raw eggs in shell |

3 to 5 weeks |

Do not freeze |

Raw egg whites |

2 to 4 days |

12 months |

Raw egg yolks |

2 to 4 days |

Do not freeze well |

Hard-cooked eggs |

1 week |

Do not freeze |

Casseroles with eggs |

3 to 4 days |

After baking, 2 to 3 months |

Quiche |

3 to 4 days |

After baking, 1 to 2 months |

To what temperature should food be cooked so that hazardous microbes are killed? It depends on the food, as the list below shows. If you don’t own a food thermometer, buy one, because using a food thermometer is the only way for you to know the internal temperature of food. There are two types of food thermometers—those that you put into the food at the beginning of cooking and leave there throughout the cooking time (usually used with roasts) and those that you insert for a few seconds to get a temperature reading when you think the food might be fully cooked. The latter are called “instant read” thermometers; they show the temperature either on a dial or as a digital number.

The FDA recommends cooking foods until they reach the following temperatures, as measured by a food thermometer:

• Cook all beef, pork, lamb, and veal steaks, chops, and roasts to a minimum internal temperature of 145°F before removing meat from the heat source. For safety and quality, allow meat to rest for at least three minutes before carving or consuming. For reasons of personal preference, consumers may choose to cook meat to higher temperatures.

• Cook all ground beef, pork, lamb, and veal to a minimum internal temperature of 160°F.

• Cook poultry to a minimum internal temperature of 165°F.

• Cook fish to a minimum internal temperature of 145°F.

• Reheat leftovers to 165°F.

To see how well you are doing in the area of food safety in your kitchen, take the “Food Safety Interactive Kitchen Quiz” at http://homefoodsafety.org/quiz.

Food in the refrigerator will be safe during a power outage as long as power is out no more than two hours. During the outage, keep the fridge and freezer doors closed as much as possible. If the power is out longer than two hours, follow these guidelines:

• A freezer that is half full will hold food safely for up to 24 hours. A full freezer will hold food safely for 48 hours.

• For foods in the refrigerated section, pack milk, other dairy products, meat, fish, eggs, gravy, and spoilable leftovers into a cooler surrounded by ice. Inexpensive Styrofoam coolers are fine for this purpose.

• Use a food thermometer to check the temperature of food from the cooler right before you cook or eat it. Throw away any food that has a temperature higher than 40°F.

The rule of thumb for food safety is “when in doubt, throw it out.”