Annotations for Exodus

1:1—13:16 Israel in Egypt. The first section of the book recounts Israel’s oppression in Egypt (1:1–22), the early life of Moses and his divine commission (2:1—4:31), the protracted conflict between the Lord and Pharaoh (5:1—11:10), and the death of Egypt’s firstborn and Israel’s deliverance (12:1—13:16). The total period covered is 430 years (12:40), although most of the material covers an 80-year period from Moses’ birth (2:1–2) to Israel’s departure (7:7).

1:1—4:31 Egyptian Oppression and the Prospect of Deliverance. Chs. 1–4 describe how a new regime ruthlessly attempted to control Jacob’s descendants and anticipate the deliverance that God promises to bring about through a most unlikely and reluctant agent.

1:1–22 The Israelites Oppressed. The proliferation of Jacob’s descendants in Egypt and a change in political leadership precipitate a crisis for the Israelites. The deliverance Joseph predicted (Gen 50:24–25) has not yet materialized. The opening chapter thus sets the scene for Israel’s anticipated exodus by describing the circumstances that Jacob’s descendants now face.

1:1–5 This flashback begins with the exact first words of Gen 46:8. Those listed (vv. 2–4; cf. Gen 46:8–25) and the quotation from Gen 46:27 (“seventy in all”) in v. 5 further reinforce continuity with Genesis.

1:5 seventy. May be a round or symbolic figure. “Seventy-five” (see NIV text note) is almost certainly a later attempt to incorporate the immediate descendants of Ephraim and Manasseh.

1:7 exceedingly fruitful . . . multiplied greatly . . . the land was filled with them. God’s promises (Gen 13:16; 15:5; 17:2, 6; 22:17) are coming to fruition as Jacob’s family in Egypt grows prolifically. Exodus thus opens on a very positive note: the mandate that God gave humans at creation (Gen 1:28), that was reiterated to Noah after the flood (Gen 9:1, 7), and that became a promise to Abraham and his offspring (Gen 17:6) is now being realized.

1:8 new king. The identity of this king who instigated the oppression of the Israelites is unclear. For just over a century (ca. 1650–1550 BC) the northern part of Egypt, including Goshen (Gen 47:27), was ruled by Semitic invaders referred to by the Egyptians as Hyksos (“shepherd kings”). It is possible that the Israelites were somehow associated with these foreigners and so would have come under close scrutiny by the new rulers (Egypt’s Eighteenth Dynasty) after the Hyksos were expelled by Ahmose I (1550–1525 BC). This new king may be one of his successors, possibly Thutmose I (1504–1491 BC) or Thutmose II (1491–1479 BC). Others associate this new regime with that of Seti I (1294–1279 BC) and his son, Rameses II (1279–1213 BC). See Introduction: The Date of the Exodus. Joseph meant nothing. This new ruler was under no obligation to maintain the special status that his predecessors conferred on the Hebrews. Like other pharaohs in this book, this king remains nameless. This may possibly be following the contemporary Egyptian custom of not naming their enemies. In any case, since the narrator did not consider such information essential, the identity of this pharaoh/dynasty should not distract us from the main focus.

1:10 deal shrewdly. Pharaoh thought he was being shrewd (cf. Gen 11:3–4), but attempting to thwart the fulfillment of God’s set plan and purpose was an act of folly, setting the stage for the ensuing struggle between the Lord and the gods of Egypt. leave the country. While Israel’s ethnic and political allegiance were an obvious worry, subsequent developments show that the chief concern was that Israel might leave the country.

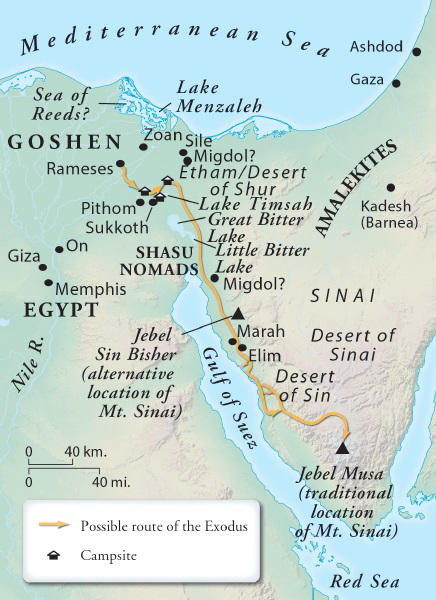

1:11 slave masters. They were Egyptian, but they later delegated some responsibilities to Israelite overseers (5:14). forced labor. This is the first of several attempts at population control. But this oppressive and brutal treatment was anticipated by God (cf. Gen 15:13). Not surprisingly, therefore, this policy failed; brutal oppression seemed only to exacerbate the problem of population control (v. 12). Pithom and Rameses. Their precise locations and nature have generated significant archaeological debate, but presumably these two “store cities” were strategically located somewhere in the eastern Nile delta, close to Goshen (see map), where the Israelites lived (Gen 45:10). Pithom. May have been located at Tell el-Retabeh, some 30 miles (48 kilometers) west of Lake Timsah. The name “Rameses” is probably linked to Rameses II, a pharaoh renowned for his building enterprises in the region, but it may be employed here for a location that previously had been known as Rowaty, then Avaris, and then possibly Peru-nefer. So this text does not indisputably settle the question of the date of these events.

![]()

![]()

1:13–14 worked . . . labor . . . work . . . labor . . . worked. Introduces a key motif. Serving and worshiping the Lord would eventually displace harsh labor in Egypt. The exploitive and demoralizing activity Pharaoh imposed sharply contrasts not only to work as God intended (cf. Gen 2:15) but to the service the Lord would demand of Israel. God’s creative and redemptive purposes are thus both under assault here as Egyptian animosity toward Abraham’s descendants intensifies.

1:15–21 Egypt’s king introduces an even more radical strategy: he conscripts Hebrew midwives to implement a crude form of “birth control.”

1:15 Shiphrah and Puah. It is not immediately obvious why these two midwives are named since neither is mentioned again. Perhaps these Semitic names simply make their nationality clear. This may contrast these women and the nameless pharaohs: unlike those who despised Abraham’s offspring and brought God’s curse upon themselves and their families (cf. Gen 12:3), these women are blessed, and posterity remember their names.

1:16, 22 boy. Use of this word, which can also be translated “son,” draws attention to a significant theme in chs. 1–15. To prevent Israel’s rebellion and departure, Hebrew sons are sentenced to death by Pharaoh. The Israelites are subsequently described as God’s “firstborn son” (4:22), and Pharaoh’s refusal to release them will result in the death of Egypt’s “firstborn son” (4:23). This happens as a result of the tenth plague (12:29–30), after which Israel is finally permitted to leave Egypt.

1:16 delivery stool. Comprised of two bricks, which women squatted on while giving birth. kill him. In keeping with the military threat previously envisaged (v. 10), Egypt’s king selects Hebrew males for extermination.

1:17 The midwives courageously refuse to comply with Pharaoh’s plan because they “feared God” more than Egypt’s king. Human authority has limitations (cf. Dan 3; 6; Acts 4:19).

1:19 Perhaps there is some truth to this explanation. After all, if these Israelites were multiplying (v. 7) and there were only two midwives for the entire population, then many women could well have given birth before a midwife arrived. But the text does not rule out misinformation (it is unlikely they were late for all such births), nor does it suggest that God blessed these women because of their deceitfulness. God blessed them because they “feared God” (v. 21).

1:21 If these midwives were themselves Hebrews (see note on v. 15), the irony should not be missed: God blessed them with the very thing that Pharaoh was seeking to deny (v. 10). In any case, rather than Pharaoh thwarting God’s plan, God thwarts Pharaoh’s plan.

1:22 Pharaoh’s final solution was state-imposed infanticide. While the dominant Hebrew text does not specify the ethnicity of the victims, English versions are undoubtedly correct in identifying them as “Hebrew” newborns. The opening chapter ends on an ominous note, but the thread of fulfillment running through it implies that Israel’s future is nevertheless secure.

2:1–22 It is into this perilous context (1:22) that Moses, the human agent of Israel’s deliverance, is born. Against all odds, he not only survives Pharaoh’s murderous decree but also finds shelter and protection within the royal household. God’s providential hand is evidently at work, even though the biblical narrator passes over this in silence. Other than the passing reference in 1:20, Exodus does not explicitly mention God until vv. 23–25, after Moses’ prospects have apparently been jeopardized by an act of folly (vv. 11–14), leading to his own mini-exodus and self-imposed exile in Midian (vv. 15–22).

2:1–10 The Birth of Moses. Pharaoh’s murderous efforts are foiled yet again, and interestingly, women again are involved: first the fertile Hebrew women; then the deceptive midwives; finally the child’s mother, sister, and ironically, Pharaoh’s daughter!

2:1–2 This new episode begins with the birth of a son to an unnamed Levite couple (see note on 6:20). Levites were the tribal descendants of Levi (Gen 29:34) and were later set apart as tabernacle officials (Exod 32:28–29; 38:21; Num 1:47–53). Nothing about this birth is unusual had it been under normal circumstances, but in view of Pharaoh’s edict (1:22), this child’s future seems grim.

2:2 saw . . . fine. Along with 1:7 (see note), this may possibly allude to the creation story (see Gen 1:31; the same Hebrew word translated “good” in Gen 1:31 is here translated “fine”), further depicting the unfolding events in terms of new creation—the creation of Israel as a nation. In any case, recognizing that he was “no ordinary child” (Acts 7:20; Heb 11:23), Moses’ mother takes steps that would preserve not only the life of her son but also, and more important, the life of Israel.

2:3 papyrus basket. The way this container is described further indicates that God’s saving purposes are at stake here. This is the only time the Hebrew noun translated “ark” in the flood story appears outside Genesis, where a much larger vessel is similarly waterproofed (Gen 6:14). Like the flood survivors, the baby is thus protected by an “ark.” Ironically, however, this ark is deposited at the very river of execution (1:22). the reeds. Ominously foreshadow the later drowning of the Egyptians in the “Sea of Reeds” in ch. 14 (see note on 10:19).

2:5–9 It may seem ominous that Pharaoh’s daughter discovers the ark, but unlike her father, she has compassion and thus ignores the royal edict. In an extraordinary turn of events, the child’s older sister (presumably Miriam; see 15:20 and note) organizes a foster home. Pharaoh’s daughter hires Moses’ mother as Moses’ wet-nurse, and Pharaoh ends up supporting one of those he condemned—the one through whom God would bring about what Pharaoh sought to prevent: the mass exodus of the Israelites from Egypt (1:10).

2:10 Moses. With a play on the boy’s Egyptian name (cf. the second element, meaning “born of,” in pharaonic names linked with the name of a deity such as Ahmose, Thutmose, and Rameses) emphasizing his providential rescue from a watery grave, this rescued child is at last named, and thus, for an Israelite audience at least, he is hereby identified as the human instrument God chose to deliver his people from captivity. Moses’ deliverance from the reeds of the Nile River foreshadows an even greater deliverance from the “Sea of Reeds” (see ch. 14; see also note on 10:19) as well as the rescue of God’s ultimate deliverer from death at the hands of Herod (Matt 2:13).

2:11–25 Moses Flees to Midian. Some 40 years elapse before this next episode takes place (Acts 7:23). According to Jewish tradition, during this time Moses received an Egyptian education (Acts 7:22; Philo and Josephus concur, adding that Moses surpassed all his peers and started to carve out a major political career). But these formative years are not important to include in Exodus, which skips over them without comment. The storyline resumes when the boy has grown up and is about to make some career-changing decisions.

2:11 went out. Moses is embarking here on his own mini-exodus, leaving the palace and exposing his personal sympathies. Moses thus takes the first tentative steps toward refusing “to be known as the son of Pharaoh’s daughter [and choosing] to be mistreated along with the people of God” (Heb 11:24–25).

![]()

![]()

2:12 There are various explanations for Moses’ action: (1) It was a rash, impulsive blow not intended to kill. (2) It was a deliberate, albeit reluctant, judicial act. (3) It was premeditated homicide. The text nowhere implies that Moses regretted his use of extreme force, and the proposal that he was looking around for someone else to intervene seems contrived. Fear of reprisal best explains Moses’ actions, and the overall impression is that Moses did exactly as he intended (Acts 7:24–25). He “strikes” a blow for the oppressed, just as later their oppressors would “strike” them and God himself would in turn “strike” their oppressors. At this stage, however, Moses was clearly acting prematurely and without any explicit divine commission (cf. chs. 3–4).

2:14 Who made you ruler and judge over us? Ironically, this is precisely the role to which the Lord subsequently calls Moses (18:13–26; Acts 7:35). The dismissive response here foreshadows the subsequent negativity Moses experiences some 40 years later (6:9; 14:10–12; 16:2–3; 17:3–4), when the Israelites further and repeatedly challenge Moses’ authority over them (Acts 7:39).

2:15 Pharaoh. Not necessarily the same pharaoh who instigated the oppression (1:8); therefore, there is no reason to insist on a reign of over 40 years for this particular pharaoh (see 2:23; 4:19; Acts 7:23). His identification again depends on which chronology is adopted for the exodus (see Introduction: The Date of the Exodus). fled. Moses instantly lost state protection when he became a fugitive. The NT appears to suggest that faith, not fear, motivated him (Heb 11:27), although that may allude to subsequent events at the time of the exodus (thus understood, Heb 11:28–29 expands on Heb 11:27 rather than reflecting a chronological sequence of events). Midian. Located in the northwestern part of the Arabian peninsula, including the southern part of the Negev (where “Midianite” ware has been found) and some of the Sinai peninsula. Midian was dry, uncultivated land, very different from the Nile delta. Significantly, the escape route chosen by Moses anticipates that of the exodus. Presumably this southeastern itinerary was chosen in order to avoid the chain of Egyptian forts along the more traveled northeastern routes and because there were no oases directly east. Although the Midianites, a nomadic people, were distant relatives of the Israelites (Gen 25:2–4), kinship was probably not a factor here (cf. Gen 27:42–45).

2:16 priest of Midian. Refers to Reuel (see note on v. 18).

2:17 came to their rescue. For the third time within a few verses (vv. 11–12, 13–14), Moses demonstrates concern for the oppressed, a concern God himself shares (v. 25). This nomadic dispute over watering rights was evidently a frequent, if not daily, occurrence.

2:18 Reuel. Means “God’s friend.” He is a priest of Midian and later becomes Moses’ father-in-law. Some infer that Reuel (also called Jethro; see note on 3:1) significantly influences Israel’s subsequent faith. But Exodus suggests that Moses and his testimony of what the Lord has done for Israel influences Jethro’s faith (18:9–12).

2:19 Egyptian. Moses’ mistaken identity—presumably on account of his appearance and language—reflects his assimilation to Egyptian culture.

2:22 Gershom. The play on this name (see NIV text note) encapsulates Moses’ resignation to refugee status. I have become a foreigner in a foreign land. While possibly alluding to Moses’ previous status in Egypt (i.e., “I have been a foreigner in a foreign land”), it more likely describes his current status. Perhaps, however, the ambiguity is intended; whether in Egypt (see 23:9) or in Midian, Moses is an alien: his true home is the land God promised Abraham (Heb 11:26).

2:23–25 This transitional paragraph switches the focus back to the situation in Egypt and signals the most significant change in Israel’s circumstances thus far.

2:23 long period. The story again passes over an undisclosed period of time (but see Acts 7:30) in relative silence. While Moses is making a new life for himself in Midian, oppression in Egypt continues—even after the death of the pharaoh. cried out. For the first time, the story mentions Israelites reacting to their enslavement.

2:24–25 God heard . . . remembered . . . looked . . . was concerned. Finally the tension is relieved. Other than the passing reference in 1:20, this is the first explicit mention of God, who now becomes the central character in the plot. At long last God acknowledges the Israelites’ distress and remembers (i.e., begins to act upon) the covenant (i.e., his sworn promises) he made with Israel’s ancestors (Gen 15:18–21; 17:8; 26:2–5; 28:13–15; 35:11–12). Thus, for the reader at least, this renews hope.

3:1–22 Moses and the Burning Bush. According to Stephen (see Acts 7:23, 30), the next incident took place when Moses was around 80 years old (cf. Exod 7:7), after having lived in Midian some 40 years. Over this period little has changed for Moses; he is still dependent on his father-in-law for his livelihood but seems quite content with his nomadic lifestyle, however alien it once was. He apparently has no intention of returning to Egypt, but this is about to change as God puts the next stage of his plan into action (see Gen 15:14).

3:1 Jethro. Unless this is some kind of title or clan name, Moses’ father-in-law apparently had more than one name (other biblical examples include Abram/Abraham, Jacob/Israel, Joseph/Zaphenath-Paneah, Gideon/Jerub-Baal, Uzziah/Azariah, and Saul/Paul). led the flock. Here the actions of Moses again foreshadow the subsequent experience of the Israelites, whom Moses would likewise shepherd and lead to Mount Sinai. Horeb, the mountain of God. Horeb, meaning “desert” or “desolation,” has been interpreted by some scholars either as just another name for Mount Sinai (19:11, 18–23; cf. v. 12) or as a different mountain peak in close proximity. Biblical usage, however, implies that Horeb refers to a wide area, whereas Sinai refers to both a specific mountain and a specific region within Horeb. It becomes known as “the mountain of God” because God manifests his presence there—first to Moses (chs. 3–4) and subsequently to Israel (chs. 19–40). There is no suggestion that God actually dwells on this mountain (see note on 15:13). The precise location of this mountain is unknown. Its traditional site (Jebel Musa) is in the central southern region of the Sinai peninsula, but more northerly sites (Jebel Serbal and Jebel Sin Bishar) and even a mountain in northwest Saudi Arabia have also been suggested (see map).

3:2 angel of the LORD. As elsewhere in the OT (e.g., Gen 22:11–18; Judg 13), this character is closely identified with God himself, reflected here in the interchangeable use of “the LORD” (vv. 4, 7) and “God” (vv. 4, 5, 6) that immediately follows. His manifestation in flames of fire forms a strong link with the sign of God’s presence elsewhere in the book: the pillar of fire and cloud (13:21–22; 14:24), the fire and cloud on Mount Sinai (19:18; 24:15–17), and the fire in the cloud over the tabernacle (40:38). At the Red Sea this angel protects the fleeing Israelites from the pursuing Egyptians (14:19), and presumably it is this same angel that God promises to send ahead of the Israelites into Canaan (23:20–23; 33:2).

3:3 strange sight. As in most biblical theophanies (divine appearances), flames of fire were a medium of such revelation—on this occasion appearing “within a bush” (v. 2). Attempts to explain the phenomenon naturalistically, however ingenious, strangely miss the point: this sight is so unusual that it catches this seasoned shepherd’s attention and draws him closer to investigate.

3:4 God called. Significantly, it is “the LORD” who sees and calls to Moses “from within the bush.” This could imply that the angel in v. 2 refers simply to the divine manifestation as flames of fire. In any case, from this point onward it is God who converses with Moses.

3:5 Do not come any closer. As was later true for the Israelites (ch. 19), Moses must maintain a safe distance and take appropriate action before approaching a holy God. Take off your sandals. The same instructions are later given to Joshua, Moses’ successor, when he has a similar heavenly encounter (Josh 5:15). As the explanation offered in both texts implies, the removal of footwear was probably to avoid contaminating holy space; significantly, priests may have served barefoot, as the absence of prescribed footwear (28:1–43) strongly implies. holy ground. Not intrinsically sacred but “separated” or “set apart” from other ground because of God’s presence. As elsewhere in Exodus, it is the Lord who makes or declares places and people to be holy, and such a status derives from their association with him, the holy God.

3:6 father. The singular (not “fathers”) is unusual (see also 15:2). Perhaps it refers to Moses’ biological father. In any case, explicitly mentioning Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob makes it clear that the God of his ancestors is addressing him, and Moses knows that standing in his presence is fraught with danger (cf. Gen 32:30). See note on 33:20.

3:7–8 God makes his intentions clear, fleshing out what it means that God “remembered his covenant” (2:24): his plan involves emancipating his people from Egyptian oppression (see Gen 15:14) and sending them to the promised land (Gen 15:16).

3:8 God describes the promised land in terms of a herder’s dream and delineates its parameters with a representative list of its indigenous inhabitants (Gen 13:7; 15:19–21; Num 13:29; Deut 7:1). milk and honey. This is the first occurrence of this phrase, covering both horticultural and pastoral activity, for the fertility of Canaan. milk. Refers to goat’s milk as well as that of cattle. honey. Could be sweet syrup from grapes, dates, and figs, as well as honey from bees.

3:10 Pharaoh. Either Thutmose III (1479–1425) or Rameses II (1279–1213), depending on the precise historical setting (see Introduction: The Date of the Exodus).

3:11 Who am I . . . ? Moses is incredulous of God’s commission, especially since Moses is focusing on himself and not factoring in the most important detail: God will help him (see v. 12 and note).

3:12 I will be with you. Foreshadows the divine name in vv. 14–15, so the outcome will succeed (the rescued people “will worship God on this mountain”). sign. This “sign” may seem a strange means of reassurance, but it is best thought of as a fulfillment sign designed to bolster faith both in the present and future. Its anticipatory nature, however, readily explains why on this occasion it fails to eradicate Moses’ doubts and fears. worship. The Hebrew word can also be translated “serve,” and is used for both the “labor/work” imposed by Pharaoh (1:13–14; 5:18) and the “service/worship” of the Lord (7:16; 8:1, 20; 9:1, 13; 10:3). Its use highlights that both Pharaoh and the Lord were vying for sovereignty over Israel, making a face-off inevitable.

3:13 What is his name? The context suggests that much more is at stake here than merely knowing God’s name, even if that name had possibly fallen into disuse during Israel’s slavery in Egypt. After all, mere acquaintance with God’s name would not prove that a theophany occurred (less incredible explanations are conceivable), still less that God sent Moses on this errand. Even more problematic is the idea that God had not disclosed his name to anyone before now (see notes on 6:2–8). Apart from difficulties in accounting for all the occurrences of “the LORD” (Hebrew YHWH) in Genesis (e.g., Gen. 4:26; 9:26; 12:8; 22:14; 26:25; 28:16; 30:27), this fails to explain how Moses could validate his prophetic credentials by presenting himself in the name of a deity hitherto unknown. But what, then, are we to make of Moses’ question? The answer may possibly be found in the interrogative used: Rather than the idiomatic “Who . . . ?” (cf. Judg 13:17), Moses asks, “What . . . ?” He is probably inquiring about God’s character, not merely his name or title (cf. Neh 9:10; see note on 3:14). This is further suggested by the fact that in ancient cultures, names conveyed essential information and were more than simply a means of identification. Thus understood, whether Moses and his fellow Israelites were familiar with God’s name or not, what both are asking for is further information about this God who has appeared to Moses.

3:14 Rather than simply answering, “My name is the LORD” (as would suffice if Moses asked for only a name), God explains his name to some extent. I AM WHO I AM. This is how most English versions render it; alternatively, “I WILL BE WHAT I WILL BE” (see NIV text note). God’s response is somewhat cryptic and has been interpreted in a variety of ways: (1) God is a self-existent and independent being. (2) God is the creator and sustainer of everything. (3) God is unchangeable and so always reliable. (4) God is eternal in his existence. While such observations about God are certainly true, the immediate context suggests that God’s explanation of his name primarily serves to bolster Israel’s confidence in the message that Moses will deliver. Accordingly, the rest of God’s answer (vv. 16–22) is a statement of his faithfulness in the past and a revelation of what he will do in the future. The Lord’s “name” therefore invites God’s people to trust him fully in anticipation of the fuller revelation of God that Moses and Israel are about to experience through the things they will see the Lord do. I AM. The divine name is now shortened to just one Hebrew word, the verbal form previously used in v. 12 (“I will be with you”). This is then replaced in v. 15 (see note there) with the more familiar form of the divine name, Yahweh, used throughout the OT.

3:15 The LORD. See NIV text note. Like most English versions, the NIV follows the practice of translating the Hebrew word (yhwh) here as “the LORD” (using “small caps” to distinguish it from another Hebrew word often translated “Lord”). The practice of translating yhwh as “LORD” derives from the earliest pre-Christian Greek translation of the OT (the Septuagint) in the third century BC. This significantly influenced the NT, not only in its use of kyrios (“Lord”) in OT quotations but also in the use of this term for Jesus, thus identifying him with the God of the OT. The divine name is also alluded to in the “I am” sayings of Jesus, correctly interpreted by the Jews as a claim to deity (see notes on John 8:58, 59). sent. The Lord emphasizes that he, their ancestral deity, has sent Moses (see also v. 14).

3:16–22 God further unpacks his character and his saving intent that is forever bound up in his name as he reiterates and amplifies Moses’ commission. Through Moses, Israel will actually discover much more about the Lord: he has actually “appeared” (v. 16) as such to Moses (cf. 4:1; 6:2–3), and he not only speaks but saves.

3:16 elders. Recognized leaders in many societies of the ancient world (cf. Gen 50:7 [“dignitaries”]; Num 22:7). They earned respect by their life experience and maturity as well as their position as heads of their tribe, clan, or household.

3:18 the God of the Hebrews. Such a depiction, however ridiculous it would seem to the mighty king of Egypt who had enslaved this people, associates the Lord with the weak and oppressed—those who are utterly dependent on him for deliverance. This is an important idea throughout the Bible. three-day journey. This may seem disingenuous in view of their ultimate destination (vv. 8, 17). Perhaps this was a conventional expression for a short journey, possibly with Egyptian sensitivities in view (8:26), or it may have been a bartering technique, making a fairly small request to determine how much (or little) Pharaoh would concede. to offer sacrifices to . . . our God. Here and throughout the following account (7:16; 8:1, 20; 9:1, 13; 10:3), Israel’s freedom from Egypt has a theological objective: the worship and service of God, their true king, whose relationship with them supersedes all other claims, including Pharaoh’s.

3:19 unless a mighty hand compels him. Mere words will not compel Pharaoh, so God will deliver Israel by striking the Egyptians (cf. 2:12) and performing wonders (see v. 20 and note).

3:20 wonders. The subsequent disasters, or “plagues.”

3:22 plunder. This alludes to the goods that victors take in battle. As well as being emancipated, the Israelite slaves will be enabled by God to receive some measure of compensation for their service (cf. 1:13).

4:1–17 Signs for Moses. Moses continues to focus on how the Israelites might respond to his extraordinary claims, prompting God to validate his testimony with the help of some supernatural phenomena.

4:2–5 The first of these “signs” (vv. 8–9) involves Moses’ staff (see note on v. 2). Transforming this staff into a snake demonstrates that the Lord is sovereign over a creature that Egypt reveres and even uses as a symbol of Pharaoh’s authority. And along with the following two signs (vv. 6–9), it subtly reminds others that the Lord not only has the power to transform but also has authority over life and death.

4:2 staff. A normal shepherd’s crook that becomes “the staff of God” (v. 20) in the sense that God uses this instrument to bolster the Israelites’ faith and demonstrate his power to the Egyptians in the subsequent account of the plagues and the exodus.

4:9 water . . . will become blood. Possibly a graphic description of the water’s extreme discoloration as clean water was poured out upon the ground (i.e., the water turned blood-red in color); the Hebrew word is sometimes used to describe something that simply looked like blood (cf. Gen 49:11; Deut 32:14; 2 Kgs 3:22; Joel 2:31). In any case, only something extraordinary could possibly have the desired persuasive effect on the target audience. This third phenomenon is later used against Pharaoh, albeit on a much larger scale (7:14–24).

4:10 slow of speech and tongue. Moses again appears to shift his focus from the Lord and the Israelites to himself and his personal inadequacies (v. 1; 3:11, 13)—this time his inability to communicate. According to Stephen, before leaving Egypt Moses had been “powerful in speech and action” (Acts 7:22), which makes it unlikely that “slow of speech and tongue” refers to a speech impediment (cf. 6:12, 30). Rather, Moses considers his communication skills inadequate because of a perceived lack of eloquence or quick-wittedness (see Paul’s description of himself in 2 Cor 10:10); he thus perceives that he is not equipped for the task. But whatever the exact problem, Moses is essentially repeating his earlier mistake—focusing on his own abilities rather than the Lord’s.

4:11–12 The rhetorical questions redirect Moses’ gaze to the one who gives human beings their faculties and who is thus able to use whatever faculties are at his disposal.

4:13 send someone else. Excuses exhausted, Moses finally exposes his underlying reason for objecting: he simply does not want to go.

4:14–17 While Moses clearly wants a replacement, the Lord has already dispatched Moses’ older brother (7:7), Aaron the Levite, to assist Moses (v. 27). Aaron’s designation (“the Levite”) probably anticipates the later significance of both him and his tribe in Israel’s worship (28:1; 32:28–29). In the immediate future, however, Aaron will serve as Moses’ mouthpiece, or “prophet” (7:1), and Moses will be like God to Aaron (see v. 16 and note). Moses and Aaron will communicate God’s message together, but God will do the actual work of persuasion (v. 17).

4:14 the LORD’s anger burned. Human disobedience—especially by God’s chosen people (cf. 32:10)—is serious. Though God is “slow to anger” (34:6), disobedience inevitably evokes his wrath, as the Israelites later discover.

4:16 as if you were God to him. Moses will communicate God’s thoughts and will.

4:18–31 Moses Returns to Egypt. While the issue of communication skills later resurfaces after Moses initially fails to persuade Pharaoh (6:12, 30), Moses is finally ready to comply with the Lord’s instructions and return to Egypt.

4:18 Let me return. Moses secures an amicable parting by observing typical etiquette (cf. Gen 31:26–28). my own people. Moses may seem somewhat vague about the goal of his mission (cf. 3:7–10, 16–22), but his words probably allude to his failed attempt to rescue the Israelites, which also began with him going to see “his own people” (2:11). Moses intends to finish the task he previously initiated.

4:19 had said. The past perfect translation is certainly possible, in which case this is a literary flashback. However, since the explanation offered to Moses at this point is new, God may be further nudging Moses along lest he procrastinate. are dead. As well as suggesting that it is now safe for Moses to return since all his enemies are dead, God’s point may be that he has already begun the process of deliverance.

4:20 sons. Although the text has mentioned only one son (2:22) and the enigmatic incident that follows mentions only one son (vv. 24–26), Moses and Zipporah have two sons (18:2–4). Moses sends them back with Zipporah to Jethro at some stage between his “near-death experience” (vv. 24–26) and the family reunion in ch.18. staff of God. As instructed (v. 17), Moses takes with him what becomes the symbol of his divine authority. This staff was used to unleash God’s power, first before the Israelites (v. 30; cf. vv. 1–9) and then against the Egyptians—during which Aaron apparently retained possession of it (7:8–12, 19; 8:5, 16; cf. 7:17; 9:23; 10:13; 14:16). But whether it is associated with Moses or Aaron, it is probably this one staff that is referred to throughout.

4:21 wonders. The extraordinary phenomena that will culminate in the death of Egypt’s firstborn (3:20; 7:8—11:10). There is evidently some overlap with the sign-acts that Moses performs before the Israelites (see note on 7:3). I will harden his heart. The first mention of a recurring theme in chs. 4–14, for which three different Hebrew verbs are used, with different subjects and in a variety of ways, as reflected in “Hardened Heart,” this page.

These data are possibly best explained in terms of a disposition of Pharaoh’s that became his undoing when God stiffened Pharaoh’s resolve (from 9:12) not to let Israel go. And so an inflexible, insensitive, and unresponsive king became even more resistant to the Lord’s will while at the same time ensuring that God’s purpose for Pharaoh (9:16) would indeed be realized. But however we resolve the problem of Pharaoh’s heart, two important points must be remembered: (1) The main concern in this section of the book is to demonstrate that the Lord, not Pharaoh, is ultimately in control, as indicated by the recurring phrase “as the LORD had said” (7:13; 8:15, 19; 9:12, 35). (2) God’s sovereign control of these affairs does not absolve Pharaoh of blame because, like all sinners, he remains fully responsible for his refusal to obey God (Rom 9:16–18).

![]()

![]()

4:22–23 firstborn son. This speech appears to rehearse what God (through Moses) will declare to Pharaoh at the climax of the conflict (ch. 11), just prior to the final blow in the series: the death of Egypt’s firstborn to punish them for refusing to release Israel, figuratively described as the Lord’s “firstborn son.” This draws attention to Israel’s special relationship with God (Jer 31:9; Hos 11:1), which was formalized through the covenant made with Abraham (Gen 15:12–21). Since this relationship obviously predates Israel’s time in Egypt, God’s claims over Israel supersede any claims Egypt could possibly have had to Israel’s service. As God’s “firstborn son,” Israel, and their Davidic king in particular (Pss 2:7; 89:26–28), foreshadows God’s unique Son (Matt 2:14–15; Rom 1:3), in whom God’s plans for Israel are perfectly realized.

4:24–26 This incident is enigmatic. The Lord seeks to kill Moses (cf. v. 19) and/or his son (see note on v. 24), apparently because Moses neglected the covenant sign of circumcision (Gen 17:1–14). Zipporah’s decisive action averts tragedy.

4:24 lodging place. Most likely a nomadic campsite near an oasis. him. Seems to refer to Moses; the original text is ambiguous. It could also refer to Gershom (Moses’ firstborn).

4:25–26 Zipporah resolves the problem by circumcising Gershom and atoning for Moses’ negligence.

4:25 feet. May be a euphemism for genitalia. bridegroom of blood. Understood by some as a derogatory statement expressing Zipporah’s revulsion over the rite of circumcision, but the precise connotation is uncertain. This incident highlights the importance of circumcision for being counted among Israel, God’s firstborn son, and thus escaping the judgment that Egypt’s firstborn will later experience (v. 23). Circumcision becomes a symbol of the inward spiritual change that generates true faith and obedience (Deut 30:6; Rom 2:28–29; Col 2:11).

4:27 This could possibly be a flashback (see v. 14). The reunion takes place at Horeb/Sinai (3:1), evidently located in the wilderness between Midian and Egypt (i.e., somewhere in the Sinai peninsula; see note on 3:1; see also map).

4:29–31 As Moses anticipated, the Israelites need convincing, but belief and grateful adoration quickly displace their initial incredulity.

5:1—11:10 Pharaoh’s Hardness of Heart and the Lord’s Mighty Acts. In this passage a prolonged conflict takes place between the Lord and Pharaoh. Pharaoh sees no reason why he should concede to any of the Lord’s demands, but he and his officials are gradually persuaded by a series of disasters that culminate in the death of Egyptian firstborn.

5:1–21 Bricks Without Straw. The stage is now set for the initial confrontation between the Lord and Pharaoh. The positive responses concluding ch. 4 sharply contrast with Pharaoh’s negative response.

5:1 Pharaoh. See note on 3:10.

5:2 Who is the LORD . . . ? Pharaoh’s confessed ignorance of the Lord becomes a major theme in the ensuing narrative: the Lord makes himself known (the possible consequences of disobedience in v. 3 allude to this). Pharaoh clearly misses this implicit warning.

5:4–5 For Pharaoh, all this talk of the Lord and his demands is simply impeding the royal construction project.

5:6–9 Intensifying their workload was probably a clever ploy to drive a wedge between the Israelites and Moses (vv. 19–21). In any case, by misconstruing their “crying out” (v. 8; cf. 2:23; 3:7) as a symptom of laziness and by dismissing their truthful claims as mere “lies” (v. 9), Pharaoh diabolically dismisses Moses’ claims and Israel’s hopes as false, and he sets himself in direct conflict with the God who has claimed this people as his own.

5:6 slave drivers. Such officials were previously described as “slave masters” (1:11). overseers. These appear to be Israelite supervisors appointed by the Egyptian slave drivers (see v. 14). Possibly, however, the “overseers” mentioned here and in v. 10 are Egyptian and therefore distinguished from the “Israelite overseers” referred to in vv. 14–16. This would explain why the latter requested information from Pharaoh (vv. 15–16) that he had already disclosed to those officially charged with carrying out his edict (vv. 6–9).

5:7 straw. A binding agent to reinforce clay bricks.

5:10 This is what Pharaoh says. This prophetic announcement formula deliberately echoes v. 1 (see also 4:22), further highlighting the competing claims of sovereignty underlying this struggle.

5:15 appealed. Or “cried out.” Once again Israel’s “cries” (see v. 8) come to Pharaoh, who, unlike God (2:23–25), is unmoved by their suffering.

5:18 get to work. The Hebrew could be translated “Go! Serve!” Pharaoh will repeat these exact words later, but in a different tone and with a different focal point (10:8, 24; 12:31).

5:19–21 The Israelites (including Moses, v. 23) did not anticipate such a hostile Egyptian reaction. So in one sense, the way the overseers respond is understandable, however misguided: Moses’ actions may have led to even more intense suffering, but Pharaoh and the Egyptians are responsible for it.

5:22—6:12 God Promises Deliverance. In view of what God had already disclosed to Moses (3:19–20; 4:21), we might expect Moses’ response to be quite different from the negativity of the disillusioned Israelites. Instead, Moses appears simply to follow suit: as the Israelite overseers blame Moses and Aaron (v. 21), so Moses now blames the Lord. Further divine reassurance is thus necessary.

5:22 returned to the LORD. Presumably Moses does not return to Mount Sinai but simply goes somewhere private where he can commune with God (cf. the tent of meeting, 33:7–11).

5:23 Moses never imagined that Israel’s circumstances in Egypt might actually deteriorate.

6:1 my mighty hand . . . my mighty hand. The Lord will deliver Israel not by mere words (4:20–21). Israel could be sure that Pharaoh would eventually capitulate to the Lord’s demands.

6:2–8 To drive home the point of v. 1, the Lord reminds Moses and the Israelites of his covenant commitment to their ancestors. The deity with whom they are dealing, who is assuring them that he will deliver them from Egypt, is none other than “the LORD,” the one who revealed himself to Israel’s ancestors and made a sworn agreement (covenant) to give them the land of Canaan. The time has come for the Lord to fulfill these covenant promises, and thus Moses must assure the Israelites that emancipation from Egyptian bondage is imminent, the Lord is about to formalize his special relationship with them, and he is about to fulfill his territorial promise.

6:3 The interpretation of this verse is controversial: Did God make himself known to Israel’s ancestors as “the LORD” (Yahweh) or simply as “God Almighty” (El-Shaddai)? As illustrated by “The Contribution of Exodus 6:3 to the Revelation of God’s Name,” this page, four significantly different approaches to this issue have been proposed.

The traditional solution is the least complicated, and makes perfectly good sense within the immediate and wider context. Thus understood, in keeping with 3:14, v. 3 is referring not to the revelation of a new name but rather to the way in which God discloses the meaning/significance of his name much more fully in the events of Exodus.

![]()

![]()

6:6–8 I am the LORD . . . I am the LORD. Brackets the anticipated fulfillment of these covenant promises. Israel will appreciate much more about the Lord through what he is about to do for them (“bring . . . free . . . redeem . . . take . . . give”) and to Egypt (“mighty acts of judgment”).

6:6 redeem. This verb links to the concept of guardian-redeemer—implying that a relative seeks justice. See note on 15:13.

6:7 I will take you as my own people, and I will be your God. This oft-repeated divine promise articulates the essence of God’s covenant relationship with his people (Lev 26:12; Deut 29:13; Jer 31:33; Ezek 37:27; Rev 21:3).

6:8 I swore with uplifted hand. An expression of a solemn promise or oath. See Gen 14:22.

6:9 Circumstances blind the Israelites in unbelief. It seems they too need to be persuaded by more than mere words (see 14:10, 21).

6:10—7:7 Exod 6:10–12 may conclude the previous unit, but it could also be read as the introduction to the following section: together with 6:28—7:7, these verses would thus be part of the frame that surrounds the genealogy in 6:13–27. The almost identical 6:10–12 and 6:28–30 serve as a bracketing device, isolating the genealogy in 6:13–27. Most significant, however, is the shift in focus in this unit from what Moses must say to Israel to what he must say to Pharaoh (7:1–5).

6:10–12 The adverse response of the demoralized Israelites (v. 9) evidently brushes off on Moses himself, who again focuses on himself and his perceived inadequacies.

6:12 faltering lips. See NIV text note. Refers simply to Moses’ lack of eloquence or his tendency to get tongue-tied (see note on 4:10). Whatever the particular concern, it explains and necessitates the role of Aaron.

6:13–27 Family Record of Moses and Aaron. This genealogy may seem to disrupt the narrative, but it serves largely to establish Aaron’s credentials and legitimacy as a leader alongside Moses. Such is clear from the introduction (v. 13) and conclusion (vv. 26–27): the usual sequence (“Moses and Aaron,” vv. 13, 27) reverses (“Aaron and Moses,” vv. 20, 26) after the genealogy ends. The genealogy mentions Reuben and Simeon only in passing to get to Jacob’s third-born son, Levi, and it quickly zooms in on his descendants. However, it terminates not with Moses but with the high priestly descendants of Aaron; including both spouses and offspring in vv. 23, 25 (cf. v. 20) highlights this. This again shifts the primary focus to Aaron. Other descendants of Kohath (i.e., Korah and his sons, and Aaron’s grandson Phinehas) are probably included because of their later significance (cf. Korah’s rebellion in Num 16 with Phinehas’s act of faithfulness in Num 25). In any case, the genealogy’s main objective is to demonstrate Aaron’s legitimacy as the mediator of Moses’ words.

6:20 Amram married . . . Jochebed. The fact that Jochebed was Amram’s paternal aunt attests to the text’s historicity; such a marriage was later prohibited (Lev 18:12; 20:19), so it would not have been “invented” by later storytellers. bore him Aaron and Moses. Kohath, born at least 350 years before Moses (Gen 46:11; cf. Exod 12:40–41), is too old to have been Moses’ grandfather, which this verse might otherwise imply (cf. Num 26:59; 1 Chr 6:3). For this reason, it seems likely that some generations are skipped over between v. 18 and v. 20, which may be further suggested by the break signaled at v. 19b. Thus understood, Amram refers to two different people in this genealogy, which has omitted less significant generations in between these two individuals—a practice which is also reflected in some other biblical genealogies (e.g., Matt 1:1–16, where two generations between David and Jesus are clearly omitted [see Matt 1:8, 11 and note on v. 8]).

6:28—7:7 Aaron to Speak for Moses. The repetition of 6:10–12 in 6:28–30 signals a return to the main story line, which continues with God’s solution to both the communication issue that Moses raised and the more significant problems ahead.

7:1 like God. Moses is like God to Pharaoh as Moses is like God to Aaron (see 4:16 and note). prophet. Aaron assumes the role of a prophet by transmitting the divine message to the intended audience (see note on 4:14–17).

7:3–5 Speaking with such divine authority does not guarantee a receptive audience, for God intends to “harden Pharaoh’s heart” (v. 3; 4:21) so that God might make himself known through “mighty acts of judgment” (v. 4) that culminate in God’s striking down Egypt’s firstborn and then destroying Egypt’s elite chariot force. Thus, despite what Pharaoh or others may think, Pharaoh’s refusal to comply ensures that the Lord’s ultimate plans materialize.

7:3 my signs and wonders. Refer to the transformation of Aaron’s staff (vv. 8–12) and in particular, the sequence of phenomena that follow (7:13—10:29; 11:10). Although there is clearly some overlap with the “signs” that Moses had earlier performed before the Israelites (4:1–9, 30), the latter were clearly designed to stimulate faith, whereas these extraordinary events, demonstrating the supremacy of the Lord and the impotence of Egyptian deities such as Pharaoh, primarily function as acts of judgment designed to induce repentance.

7:5 the Egyptians will know that I am the LORD. Addressing Pharaoh’s earlier question and professed ignorance in 5:2 (“Who is the LORD . . . ? I do not know the LORD”), this repeated statement (see 7:17; 8:10, 22; 14:4, 18) explains the rationale behind God’s “signs and wonders” (7:3) and “mighty acts of judgment” (7:4): they were so that God might make himself known to the Egyptians, as well as to the Israelites (6:6–7; 10:2), as Israel’s covenant God (3:14–15; 6:2–8). Centuries afterward, in the context of the Babylonian exile and the prospect of a new exodus, Ezekiel similarly uses the phrase in relation to the Lord’s later acts of judgment and salvation (e.g., Ezek 28:22; 36:23), foreshadowing the personal knowledge (John 17; see Heb 8:10–12) and acknowledgement (Phil 2:9–11) of the Lord that comes through God’s final self-revelation in Jesus.

7:8–13 Aaron’s Staff Becomes a Snake. Though distinct from the following series of phenomena traditionally called “plagues,” this first “wonder” that Moses and Aaron perform before Pharaoh serves as a prelude: the Lord demonstrates his great power, but Pharaoh foolishly refuses to learn from it.

7:9–12 snake . . . snake . . . snake. This translates a different Hebrew word than that translated “snake” in v. 15 and 4:3; the term used in 7:9–12 is apparently a more terrifying reptile, possibly a crocodile. It is most often associated with primordial monsters of chaos (Job 7:12; Pss 74:13; 148:7; Isa 27:1; 51:9), but on two occasions it symbolizes Pharaoh’s own despotic power (Ezek 29:3; 32:2).

7:11 magicians. They are the “wise men and sorcerers,” not a subgroup (cf. Gen 41:8). In Egypt, religious practices were closely linked to magic, and temple libraries included ritual and magical texts studied by the priests. According to the NT, two of these professionals summoned by Pharaoh—Jannes and Jambres (2 Tim 3:8)—seem to have played a leading role. their secret arts. Whether this alludes to magical deception (i.e., sleight of hand) or genuine occult activity is beside the point: Aaron’s staff swallowing up their staffs (v. 12) demonstrates that the Lord is superior. It is a portent of the Lord’s ultimate triumph over Pharaoh when the earth swallows up Pharaoh’s army (15:12).

7:13 as the LORD had said. A recurring refrain in the plague narrative (v. 22; 8:15, 19; 9:12, 35). It further emphasizes that the Lord is sovereign over Pharaoh.

7:14—10:29 God’s striking of the Egyptians, which he anticipates in 3:20, begins with the ten “plagues” (9:14; 11:1). The first nine of these are arranged in three groups of three: 7:14—8:19; 8:20—9:12; 9:13—10:29. The accounts of some of the signs omit certain details, assuming that the reader will fill in these “narrative gaps” from the general pattern described. The first disaster in each group (i.e., the first, the fourth, and the seventh plagues) is introduced by a warning delivered to Pharaoh in the morning as he went out to the Nile (7:15; 8:20; 9:13), whereas the last disaster in each group (i.e., the third, the sixth, and the ninth plagues) comes without any warning to Pharaoh. The trajectory of each group, and of the unit as a whole, thus signals that the Lord’s patience with Pharaoh will run out. See “Structural Features of the ‘Signs and Wonders’ Narrative.”

The catastrophes demonstrate that the Lord, not Pharaoh, is sovereign over Egypt, and they constitute judgment on the Egyptians for refusing to submit to God’s demands. Explanations of their chronology in terms of sequentially related natural disasters (e.g., red silt washed into the Nile River, starting a domino effect on Egypt’s ecology) invariably undermine the miraculous nature and theological significance attached to these events in the biblical account, and they are deeply flawed if the objective is in any way to bolster the text’s historical credibility.

7:14–24 The Plague of Blood. The first plague strikes at the very heart of Egypt’s life and economy: the Nile River.

7:14 Then the LORD said to Moses. All the disasters in the following sequence begin with this phrase (8:1, 16, 20; 9:1, 8, 13; 10:1, 21; see 11:1), signifying that each of them is governed by God’s word to Moses.

![]()

![]()

7:15 in the morning. See “Structural Features of the ‘Signs and Wonders’ Narrative.”

7:17 you will know. See notes on 5:2; 7:5. See also 8:10, 22; 9:14, 29; 11:7. changed into blood. See note on 4:9. Unlike the Israelites (see 4:1–9, 29–31), who were persuaded when similar signs were performed before them (staff to reptile; water to blood), Pharaoh is unimpressed by this ecological crisis that severely impacts Egypt’s fresh water supply (v. 24).

7:18, 21, 24 Egyptians. May imply that the Israelites were somehow sheltered from the immediate effects of this plague. Although 8:22 explicitly mentions such discrimination for the first time, this may not necessarily be a new development; as the impact of the strikes/plagues increases, the issue of discrimination becomes more important.

7:20 Moses and Aaron readily obey God (cf. vv. 6, 10), sharply contrasting with Pharaoh’s defiance.

7:22–24 As before (vv. 11–13), the magicians’ actions foster Pharaoh’s resistance.

7:24 Apparently only the water of the Nile River was unusable.

7:25—8:15 The Plague of Frogs. The scale of the second plague is again widespread: frogs encroach everywhere and on everyone. While the magicians are apparently able to replicate this phenomenon also (8:7), Pharaoh’s reaction is more conciliatory (8:8)—at least until the crisis ends.

7:25 Seven days passed. Pharaoh is graciously given time to repent before further judgment, but he squanders the opportunity (cf. Rev 9:20–21; 16:10–11).

8:2–4 Presumably the frogs abandon the Nile River because it is so contaminated.

8:5–7 As before, the onset of the plague swiftly follows its announcement. While possibly a narrative gap, more probably this indicates that Pharaoh has no intention of changing his mind.

8:8 Rather than hardening his resolve (as previously), Pharaoh for the first time acknowledges the Lord’s power—indeed, his request is a tacit admission of Egyptian impotence (v. 9). I will let your people go. For the first time, Pharaoh mentions the possibility of emancipation, but his subsequent actions do not match his words.

8:9–11 To remove any doubt about this phenomenon and thus the Lord’s supremacy, Moses gives Pharaoh the “honor” (v. 9) of deciding when it should end.

8:12–15 Significantly, when Moses cries out to the Lord on Pharaoh’s behalf, the Lord responds to Pharaoh’s request immediately.

8:13, 31 the LORD did what Moses asked. See Gen 20:7; Jas 5:16.

8:13 The frogs died. Clearly as a result of the Lord’s action, whether or not environmental circumstances were used to bring this about.

8:15 he hardened his heart. See note on 4:21 and “Hardened Heart.” This is the first text that explicitly says that Pharaoh hardens his heart (see also v. 32; 9:34).

8:16–19 The Plague of Gnats. It is impossible to determine what biting insect this is. It is possibly some form of lice. The impact is clearly extensive (vv. 16b, 17b).

8:19 finger of God. For the first time, the Egyptian magicians cannot duplicate the wonder, and thus they acknowledge its divine source using a figure of speech that elsewhere refers to God’s miraculous power (31:18; Luke 11:20). See also the similar use of the Lord’s “hand” (3:19–20; 7:4–5; 9:3, 15; 13:3) and the Lord’s “arm” (6:6; 15:16). While the Egyptians’ use of this phrase is arguably a clever attempt to avoid offending Pharaoh, their divine king, whose hand is all-powerful, it seems more likely that they are conceding that their own expertise and supernatural powers are manifestly inferior to that exercised by Aaron. would not listen. Despite this significant concession by his magicians, Pharaoh remains adamant. But the author reminds us that such obstinacy only amplifies the extent of the Lord’s dominion.

8:20–32 The Plague of Flies. This is the first disaster that explicitly mentions the Lord discriminating between the Egyptians and the Israelites, limiting this infestation to areas that the Egyptians occupy.

8:22 Goshen. The region enjoys immunity, a distinction that cogently illustrates the Lord’s presence in the land as well as his ability to protect his people while judging his enemies (cf. Ezek 9; 2 Pet 2:4–9).

8:24 For the first time in this sequence of wonders, there is no mention of any human agency.

8:25–27 Pharaoh subtly reduces their demand to merely performing religious ritual that they could carry out anywhere. It is ill-conceived in terms of Egyptian sensitivities (the precise nature of which are debatable; see Gen 43:32; 46:34), but more important, it is contrary to what the Lord expressly demands.

8:28 in the wilderness. Pharaoh makes a further concession but still attempts to control the Israelites’ movements. pray for me. Pharaoh is clearly acting out of self-interest: he desires immediate relief from the flies.

8:30–32 As expected, Pharaoh’s accommodating attitude dissipates as soon as the immediate crisis passes. For the second time in the sequence (v. 15), Pharaoh himself hardens his heart in response to the relief the Lord graciously grants.

9:1–7 The Plague on Livestock. The intensity and seriousness of these disasters now appear to increase. Previously these have been little more than a gross inconvenience or irritation. This plague, however, results in the death of Egyptian livestock.

9:1–2 The announcement of the fifth plague again begins with the Lord’s basic demand (see v. 13; 5:1; 7:16; 8:1, 20; 10:3) followed by a conditional threat. A phrase here uniquely augments the conditional element: “continue to hold them back” (see v. 2 and note).

9:2 hold them back. This possibly alludes to Pharaoh’s hardened heart, because different forms of the same Hebrew word describe the hardening of Pharaoh’s heart 12 times (vv. 12, 35; 4:21; 7:13, 22; 8:19; 10:20, 27; 11:10; 14:4, 8, 17).

9:3 hand of the LORD. The first mention since 7:4 (cf. 8:19). This verse uniquely describes the imminent disaster as a “terrible” plague.

9:5 Tomorrow. Now the Lord sets the time (cf. 8:9–10), suggesting that Pharaoh is losing what little control he exercised.

9:6 All the livestock . . . died. Possibly just those outside (see v. 3, which stipulates “in the field”), since the subsequent account (vv. 20–21) clearly shows that at least some Egyptian livestock survive. The main point is that, unlike the Lord, Pharaoh cannot preserve the livestock of his people. This contrast is even more pronounced when it comes to protecting their respective people from death.

9:8–12 The Plague of Boils. In some respects this disaster foreshadows the tenth, seriously impacting both humans and animals.

9:11 could not stand before. The Egyptian magicians, who previously “opposed Moses” (2 Tim 3:8), cannot protect themselves from these boils, still less the Egyptian population as a whole. Their inability further underlines their impotence. Despite this, Pharaoh remains indifferent (v. 12).

9:12 the LORD hardened Pharaoh’s heart. In explicit fulfillment of the earlier declarations (4:21; 7:3), perhaps further indicating that Pharaoh’s reaction is both irrational and unnatural. In any case, events are working out exactly as the Lord planned.

9:13–35 The Plague of Hail. The final triad of plagues is the longest, due mainly to the increased level of interaction between the parties involved. The first of the three also contains additional information about Pharaoh’s role in the plan and purposes of God.

9:14 full force of my plagues. The prospect of fully unleashing the Lord’s wrath against Egypt intensifies the threat. He “could have” (v. 15) already annihilated Egypt.

9:16 This explains why the Lord has not annihilated Egypt (v. 15). I have raised you up. Or “I have caused you to stand.” The ambiguity of the verb allows two interpretations: (1) “I have raised you up” (cf. Rom 9:17), meaning the Lord sovereignly ordains Pharaoh’s circumstances. (2) “I have spared you” (see NIV text note). In either translation, the Lord has not exercised lethal force against Egypt thus far so that he might personally disclose his mighty power and so that his name would be globally proclaimed.

9:17–19 The opportunity given to shelter potential victims from this unprecedented hailstorm highlights not only the escalating scale of these disasters but also God’s concern to preserve rather than extinguish life (see Ezek 18:32; 2 Pet 3:9)—including that of animals (Jonah 4:11).

9:20 The wise actions of a few of Pharaoh’s officials show that some Egyptians are gradually recognizing that the Lord is supreme. This anticipates even greater capitulation (10:7).

9:22–26 As anticipated, the storm destroys everything in its wake. Only Goshen (cf. 8:22) escapes unscathed, further demonstrating that this hailstorm is no ordinary severe weather system or coincidental freak of nature but is an act of God.

9:25 everything. See note on vv. 31–32.

9:28 With his petition for prayer (cf. 8:28) and further promise of freedom, Pharaoh seems defeated. But Moses’ critical appraisal (vv. 29–30) shows that the Lord does not yet give Moses any reason to believe Pharaoh (cf. 11:1).

9:29 spread out my hands. A common posture for prayer (1 Kgs 8:22; Ezra 9:5; Isa 1:15; 1 Tim 2:8). Archaeological excavations have uncovered statues of men praying with elevated arms.

9:31–32 This parenthetical note qualifies v. 25 and explains how the forthcoming locust invasion is so catastrophic even in the aftermath of the hail’s destruction.

9:34 In keeping with the now-familiar pattern, once Moses secures relief, Pharaoh reneges on his promises (vv. 27–28) and transgresses. officials. Presumably those in v. 21 but possibly those in v. 20 as well. hardened their hearts. Further underlines Egyptian (not just Pharaoh’s) culpability.

10:1–20 The Plague of Locusts. Like the account of the previous disaster, this one is considerably longer than others. It further explains Pharaoh’s obstinacy.

10:1–2 so that . . . that . . . that. The Lord hardens the hearts of Pharaoh and his officials for the three purposes mentioned in the text.

10:3 The rhetorical question highlights the underlying problem: Pharaoh refuses to acknowledge his proper place in the created order by asserting that he is sovereign over the Lord. This is the last time the Lord restates his core demand (5:1; 7:16; 8:1, 20; 9:1, 13), which further indicates that this struggle is approaching resolution.

10:5–6 The locust invasion’s anticipated effects and unprecedented nature show that the plagues are escalating in their intensity.

10:7 How long . . . ? Ironically, Pharaoh’s exasperated officials echo Moses’ question in v. 3 before they reiterate the Lord’s basic demand to Pharaoh. Egypt is ruined. Persistent rebellion against God has disastrous consequences for nations as well as individuals.

10:10 The LORD be with you. This bristles with sarcasm. you are bent on evil. Expresses Pharaoh’s true sentiments.

10:11 only the men. Pharaoh’s restriction is a clever ploy to ensure that they return to Egypt. driven out. Patience on either side is wearing increasingly thin (cf. v. 3).

10:13 east wind. Possibly explains how such a huge swarm of locusts came to be in Egypt (cf. v. 19). This may also anticipate the Lord’s final victory over the Egyptians (14:21; 15:10). God’s ability to control even the wind displays his sovereign power (see Ps 135:7; Jer 10:13; Matt 8:23–27).

10:14 Never before . . . nor will there ever be again. This is an idiom meaning, “this is as bad as it gets.” It further highlights the escalating scale of these disasters (cf. 9:18). The impact of this plague in the ancient world is barely imaginable.

10:16–17 The text implies but does not explicitly state that Pharaoh is willing to grant the Lord’s wishes (cf. v. 20).

10:18 Moses does not warn Pharaoh (as in 8:29) or accuse him (as in 9:30) in return. This gives the impression that Moses is resigned to Pharaoh’s stubbornness, which must run its course.

10:19 Red Sea. Behind this name is the Egyptian term for “reed” that was assimilated into the Hebrew of the OT to identify this body of water as the Reed Sea, or the Sea of Reeds (see NIV text note). Apparently not knowing how to translate this term, the Septuagint (the pre-Christian Greek translation of the OT) and later translators wrote “Red Sea.” The Gulf of Suez and other bodies of water bordering the southern Sinai peninsula became known as the Red Sea. In Moses’ time the waters of the Gulf of Suez extended farther north. That, combined with other lakes and man-made canals, formed a boundary between Egypt and the lands to the east. One or perhaps several of these lakes (for which there is no separate word in Hebrew; cf. “Sea of Galilee”) made up the Red (“Reed”) Sea that Israel would cross. It was known to the Egyptians of Moses’ day as the Reed Sea. Whatever its exact location, it was a significant body of water—large (and deep) enough to drown the Egyptian army (ch. 14), which the fate of the locusts here seems to foreshadow.

10:21–29 The Plague of Darkness. Like the third and sixth plagues, the ninth is unannounced. But this one ends with an unexpected twist: Pharaoh bans Moses from any further audiences with him.

10:21 darkness. Egypt’s chief deity, with the most expensive and influential temple (at Karnak), was the sun-god Amun Ra (or Re). Of all the first nine plagues, this one would have held the most obvious challenge to Egypt’s religion. Its duration and intensity (vv. 22–23) suggest that (like the previous two plagues) this is an unprecedented experience in Egypt’s history.

10:22 three days. It is unclear whether Pharaoh summons Moses during this period of darkness or after light is restored. Pharaoh’s track record suggests the former, yet he does not ask Moses to remove the darkness nor does the text explicitly say that the Lord does so. Perhaps Pharaoh breaks off negotiations (v. 28) at the end of the three days once he sees that normality is restored.

10:23 all the Israelites had light. This makes naturalistic explanations for the darkness (e.g., an extremely severe sandstorm or solar eclipse) problematic.

10:24–26 Pharaoh concedes a little more by allowing women and children to go (cf. v. 11). However, as Moses observes, Pharaoh’s restrictions undermine and frustrate the major objective of their departure.

10:27 See note on 4:21. Pharaoh has lost any control over how this conflict with the Lord will work out.

10:28–29 Pharaoh’s threat and Moses’ response may seem strange since Moses does speak to Pharaoh in person in 11:4–8, and a further meeting between them is reported in 12:31–32; the problem of 11:4–8 is resolved by the use of the past perfect (“had said”) in 11:1, 9—interpreting the initial and concluding verses of ch. 11 as literary flashbacks. Accordingly, the words of 11:4–8 were actually spoken during the heated exchange of 10:24–29 rather than subsequently. It is also possible to make sense of the sequence without using the past perfect in 11:1. Since the instructions of 4:21 have been faithfully carried out, Moses is now being told (11:1–2) to implement the instructions of 4:22–23 and 3:22 (cf. 3:20–21). Whatever the case, this heated exchange clearly marks the end of formal negotiations between Pharaoh and Moses, and it demonstrates Pharaoh’s continual disrespect for both Moses and God.

11:1–10 The Plague on the Firstborn. This announces the tenth plague, but its execution and consequences appear later (12:29–36). If vv. 1–3 and 9–10 are literary flashbacks (cf. 3:19–22; 4:21–23), the dialogue between Pharaoh and Moses in vv. 4–8 is simply the tail end of the conversation in 10:24–29 (see note on 10:28–29). Thus understood, having obeyed the instruction of 4:21, Moses now (i.e., as the final part of the conversation with which ch. 10 ends) carries out the instruction of 4:22–23 before negotiations break off entirely.

11:1 had said. Understood in the past perfect, vv. 1–2 reiterate what the Lord told Moses previously. Taken in the simple past, the Lord here announces that the sequence of wonders has run its course and it is now time for the final, deadly blow that had been anticipated from the outset (4:23).

11:2–3 See note on 3:22. For the fulfillment of this prediction (indicating Egypt’s total capitulation and defeat), see 12:35–36.

11:4–8 The narrator returns to the conclusion of the conversation that seemingly ended with 10:29. In keeping with the Lord’s earlier directive (4:21–23), the time has come for executing Egypt’s firstborn. This last plague is retribution for the suffering that Egypt inflicted on Israel, God’s firstborn son (4:22–23): Egypt’s “wailing” (v. 6) echoes Israel’s “crying out” (3:7; the same Hebrew verb is used). Pharaoh’s supposed divinity is once more undermined here by the God who is sovereign over life and death.

11:7 The discriminating effect of this plague (like previous ones) highlights its extraordinary nature and theological significance.

11:8 The anticipated capitulation of Pharaoh’s officials again highlights that the Lord is sovereign and Pharaoh is impotent. Pharaoh may still be issuing orders (cf. 10:28), but the Lord is in control.

11:9–10 A final summary of all that has transpired so far. Pharaoh’s stubbornness has served God’s sovereign purpose.

12:1—13:16 Redemption and Consecration of Israel’s Firstborn. The material in ch. 11 is descriptive, containing information necessary to understand the story. Chs. 12–13 are largely prescriptive, focusing on the ritual involved in that first Passover night as well as the regular celebration of Passover/Unleavened Bread and the consecration of the firstborn by future generations.

12:1–30 The Passover and the Festival of Unleavened Bread. Between the announcement of the final plague and the execution of it are instructions concerning the Passover Festival. The first section (vv. 1–20) contains two subunits: vv. 1–13 relate primarily to the original Passover, and vv. 14–20 concern its annual commemoration. The second section (vv. 21–28) narrates Moses’ communication of these instructions (at least in part) to the people via their elders, followed by a brief description of the scale of the actual destruction (vv. 29–30).

12:2 The exodus marks the start of the process by which Israel became a holy nation, and so it marks the beginning of the nation’s religious calendar. first month. Aviv (13:4); the spring month (corresponding to March–April in the Western calendar); renamed Nisan after the exile (Esth 3:7).

12:3 lamb. The sacrificial animal can be either a lamb or a kid (see NIV text note). Small households are to share an animal (v. 4), which ensures adequate provision without unnecessary waste.

12:5 without defect. While not explained here, this stipulation is elucidated elsewhere in terms of the animal’s acceptability as a sacrifice (Lev 22:18–25; Mal 1:6–14). This requirement clearly foreshadows the sinless perfection of Jesus, the ultimate Passover Lamb, whose death was a substitutionary atonement for human sin (John 1:29; 1 Cor 5:7; 1 Pet 1:19.). Although the connection between the Passover sacrifice and either sin or atonement is not made explicit in Exodus, its substitutionary nature clearly implies that the death of the Passover animal, like that of Jesus, had atoning significance for Israel. This is further suggested by the fact that, unlike in the preceding disasters, God does not simply exempt his people from this destruction. Like Pharaoh, Israel’s sin had to be addressed by a holy God, either through punishment or atonement.

12:6 at twilight. Or “between the evenings”; the period between either (1) early evening and sunset or (2) sunset and nightfall—which has given rise to disputes about when the Sabbath and other holy days begin. Some scholars hold that in the preexilic period the day was reckoned as starting in the morning, but this changes to evening in the postexilic period due to Babylonian influence.

12:7 blood. Represents life (Lev 17:11), thus deliverance through the blood of the Passover animal denotes its substitutionary nature; its life was given in exchange for another. Elsewhere in Exodus blood is used for both atonement (30:10) and consecration (29:19–21; cf. 24:6–8). Both concepts are probably included here: the blood both atones for Israel’s sin (Heb 9:22) and consecrates each household by purifying it with this distinguishing mark. Deliverance through the blood of a lamb prefigures the eternal salvation secured through the Lamb of God by his death (John 1:29).

12:8–9 Regulations governing the meat’s consumption distinguish this rite from analogous rituals in Canaanite practice.

12:8 bitter herbs. A side salad requiring little preparation and not necessarily carrying any theological significance—despite the earlier use of the same word for Israel’s “bitter” service (1:14) and the subsequent association of these two texts in later practice. bread made without yeast. Unleavened bread reflects their hasty departure (vv. 11, 39).

12:10 Do not leave any of it till morning. This regulation, reiterated in 23:18, was probably to prevent using the consecrated meat for normal consumption.

12:11 cloak . . . sandals . . . staff. The Israelites are to eat the meat dressed and ready to leave because there will be little time to pack or prepare for the journey (v. 39). Passover. Refers primarily to the victim, secondarily to the festival. The word is explained by the fact that the Lord “passed over” (v. 27; see vv. 13, 23) Israelite households marked by the sign of the animal’s blood.

12:12 In executing Egypt’s firstborn, the Lord brought “judgment on all the gods of Egypt.” Some infer a subtle critique of Egyptian gods and beliefs throughout the plague narrative. While certain plagues may implicitly expose the impotency of particular Egyptian deities, the text focuses much more on how they demonstrate the Lord’s supremacy over Pharaoh, an unwitting instrument in God’s plan and purposes (Rom 9:17, 22–24).

12:13 sign. Marks the Israelites’ special status as God’s people, those the Lord chose to redeem rather than judge (8:23).

12:14 The focus shifts to how future generations should commemorate this event (cf. Num 9:1–5; Josh 5:10; 2 Kgs 23:21–23; Ezra 6:19–22; Matt 26:17–19; Luke 2:41; John 11:55).

12:15 without yeast. The dough for a day’s bread was normally mixed and left to stand before being baked so that a small quantity of the fermented dough from the previous day’s batch could “leaven” (raise) the new batch. In this instance the Israelites must remove such fermented dough or “leaven” on the first day; God imposes a total ban. Leaven/yeast thus becomes a symbol in the NT for sinful behavior (Luke 12:1; 1 Cor 5:6–8), which must likewise be eradicated, as far as is possible, from the life of the Christian community. cut off. Consuming leavened bread during this seven-day period was a serious matter; in the present context, “cut off from the community of Israel” (v. 19) may elaborate on “cut off from Israel”; i.e., it refers here to exclusion from the annual celebration rather than to some form of execution, as is plainly the case later in the book (see 31:14–15, where the same Hebrew verb is used).

12:17 Unleavened Bread. The name of this week-long (v. 15) festival. Here, as elsewhere in the Pentateuch, its rationale is explicitly tied to the exodus.

12:18 from the evening . . . until the evening. This suggests that the Festival of Unleavened Bread begins on the evening of the 14th day and ceases on the evening of the 21st day. But other passages suggest it begins on the 15th day, the day after Passover (Lev 23:5–6; Num 28:16–17). The simplest solution to this crux is that the 15th day in the latter texts begins with sunrise rather than sunset (see note on v. 6); Lev 23:6 and Num 28:17 do not mention “twilight” or “evening.” While the Jewish day began at sunset in the postexilic period, the dating formula in all Pentateuchal Passover texts could imply that the day starts at sunrise (as with the Egyptians). Thus understood, while Israelites are not to consume any leaven from the beginning of Passover at twilight on the 14th day, the Festival of Unleavened Bread officially begins on the morning of the 15th day and concludes on the evening of the 21st day by sacred assemblies.

12:21–28 Moses imparts the Lord’s twofold set of directives—in the same sequence—to “all the elders of Israel” (v. 21; see note on 3:16). They are “all” involved only twice elsewhere in the book, and each instance is a particularly significant occasion (4:29; 18:12).

12:21 elders. See note on 3:16. Go at once. “Round up and select” possibly explains the idea here. Passover lamb. Jesus fulfills this OT type (see note on v. 5).

12:22 hyssop. This plant (probably from the mint family) had a straight stalk (John 19:29) that, along with the hairy texture of its leaves, made it a natural sprinkling device. Elsewhere in the Bible it is generally associated with purification rituals (Lev 14:4, 6, 49, 51–52; Num 19:6, 18; Heb 9:19; cf. Ps 51:7).

![]()

![]()

12:23 destroyer. Traditionally understood as a destroying angel (cf. 2 Sam 24:15–16; 2 Kgs 19:35; 1 Cor 10:10).

12:26 when your children ask. Cf. 13:14. Celebrating Passover and Unleavened Bread instructs future generations and helps them grasp its ongoing significance for them as the nation the Lord has redeemed.

12:27–28 The Israelites again respond positively to Moses’ message (4:31). Evidently the Lord’s signs and wonders in Egypt eradicated their fears and misgivings (cf. 6:9). The Israelites again serve as a foil to Pharaoh, whose negative response is a refrain throughout the plague narrative.

12:29 struck down. As promised, the Lord has already struck Egypt with several disasters (3:20); however, this blow is the most devastating. As anticipated (11:5), no Egyptian family enjoys immunity, regardless of their social status or category.

12:31–42 The Exodus. After the mixture of initial instructions and regulations for its subsequent celebration, the story of Israel’s escape from Egypt resumes. The Lord makes good on both his threats and his promises.

12:31–32 In view of 10:28, there is some degree of irony here; Pharaoh now summons Moses and Aaron into his presence, despite his previous attempt to break off all communication with a threat of death. as you have requested . . . as you have said. Just as God had predicted (3:20; 11:1), Pharaoh now capitulates entirely.

12:32 bless me. This is the closest Pharaoh comes to acknowledging the power of Israel’s God, although even now he fails to confess the Lord’s universal supremacy (cf. 15:11; 18:11) and displays the same desire for immediate respite that he has demonstrated throughout the plague narrative. Ironically, the blessing Pharaoh asks for might already have been experienced had he dealt with God’s people differently (cf. Gen 12:3; 21:22–24; 26:28–31; 39:5).