Plant in full sun but provide light shade where daytime temperatures exceed 80°F/26.6°C.

Plant in full sun but provide light shade where daytime temperatures exceed 80°F/26.6°C.into a garden and keeping them all happy and growing vigorously is a challenge. When you consider the care that each crop requires to grow well — from raising delicate seedlings to helping transplants adjust to the outdoors to preventing water stress and pest problems — it’s very easy to get caught up in, and overwhelmed by, the details. When is it time to start the lettuce or broccoli seed? Is it too late to plant tomatoes? Will the peppers survive if they’re moved outdoors now, or should I wait a week? What does a ripe eggplant look like? How do I grow a fall crop of kale or cabbage?

While experienced gardeners do keep track of many of the details for each crop, they’re also aware of the similarities these crops share. For one, nearly all of them will grow in well-prepared garden soil that is rich in organic matter. So prepare the soil once for everybody, then plant.

In the pages that follow, you’ll find information that will help you produce a topnotch harvest of the most popular vegetable crops. Each crop entry begins with tricks and tips for starting seedlings and moving transplants to the garden and then goes on to cover essential care during the growing season and how to harvest produce at its prime. You’ll also find a list of essential Tips for Success that summarize the most important techniques for growing each crop like an expert. Problem Patrol guides you through the challenge of averting common pest, disease, and other problems you may encounter with each crop. To make information easy to find, crops that have the same growing requirements and that are grown on similar schedules are grouped together. For example, if you turn to page 210, you’ll find the entry that covers broccoli, cabbage, cauliflower, and their relatives. For more information about USDA hardiness zones and to find out what zone you garden in, go to www.arborday.org/treeinfo/zonelookup.cfm or inquire at your Cooperative Extension Office.

As you gain experience with the crops featured here, you’ll identify tricks that work well in your garden, schedules that make sense for you, and favorite ways to handle chores from trellising to pest prevention. That’s one of the most enjoyable aspects of gardening: It’s personal. Your garden is different from that of every other gardener, as is the way you take care of it. Enjoy the process!

Plant in full sun but provide light shade where daytime temperatures exceed 80°F/26.6°C.

Plant in full sun but provide light shade where daytime temperatures exceed 80°F/26.6°C.

Provide a long growing season with warm days and cool nights.

Provide a long growing season with warm days and cool nights.

Replace plants every 4 or 5 years; in cold climates, grow them as annuals.

Replace plants every 4 or 5 years; in cold climates, grow them as annuals.

Q Can I grow artichokes? Are they annuals or perennials? I live in southeastern Pennsylvania.

A Also called globe artichokes, these Mediterranean perennials can be grown as annuals in the Mid-Atlantic and some other parts of the country provided you select the right cultivars to grow, start them early, and protect them from cold spells. ‘Imperial Star’ is a good choice for annual cultivation. Start seeds indoors 8 to 12 weeks before the last spring frost, and grow them at temperatures between 60-70°F/15.5-21°C. The seedlings need to be exposed to cool temperatures — 50°F/10°C — for at least a week or 10 days in order to flower, so about 2 weeks before the last spring frost, move them to a cold frame or a spot where you can maintain cool temperatures. The plants won’t grow during this cold treatment, but it is essential if they are to produce chokes. Watch the weather carefully, and bring them indoors if colder weather threatens, since artichokes don’t tolerate cold snaps. Move them to the garden about 2 weeks after the last frost.

Although artichokes are hardy from Zone 8 south, they do not tolerate the heat and humidity of Southeast summers well. Outside Northern California they probably won’t produce well when grown as perennials. Try ‘Violetto’ or ‘Texas Hill’ for areas with hot summers and warm winters.

Q How do I grow artichokes as perennials in Northern California?

A From seed, artichoke plants take 110 to 150 days to produce flower buds, which are the edible portion of the plant. Start seeds indoors 8 to 12 weeks before the last spring frost. For faster turnaround, start with divisions, which will begin producing buds about 100 days after planting. Plant seedlings or divisions with the crowns of the plant just above the soil surface; when growing them as annuals, plant them slightly deeper, and mulch with straw or floating row covers until the weather warms up. Space plants 3'/.9 m apart in rows 3'-4'/.9-1.2 m apart. For fat, fleshy flower buds, the soil should be evenly moist but not wet. In warm climates, add a 3"-4"/7.6-10.2 cm layer of compost or other mulch to keep the soil cool. Water monthly with fish emulsion in spring and summer. Plants tolerate drought but won’t flower well in dry soil.

Artichoke flower buds are ready for cutting when they are still green. The bracts (see Glossary) should be tight against the bud. To harvest, cut them with 2"-3"/5-7.6 cm of stem still attached. After harvesting the central stalk, which flowers first, cut it back to about 1'/.3 m to encourage side shoots and more flower buds to form.

Cutting an artichoke bud

Q What care do artichoke plants need at the end of the season?

A In late fall cut the plants to the ground and mulch them. Artichokes are seldom troubled by pests or diseases, but clumps do begin to lose vigor after 4 or 5 years. When that happens, dig the clumps and replace them in spring. In areas where artichokes are not hardy (Zone 7 north), try digging and potting up clumps 1 month before the last frost date. Overwinter them in a cool, frost-free place, and move them back to the garden after danger of frost has passed.

At planting time, pay special attention to soil preparation, along with annual soil improvement, since plants will produce for 15 years or more.

At planting time, pay special attention to soil preparation, along with annual soil improvement, since plants will produce for 15 years or more.

Choose all-male cultivars, which are two to three times more productive than conventional cultivars.

Choose all-male cultivars, which are two to three times more productive than conventional cultivars.

Harvest spears daily once plants are in full production, twice a day if temperatures are in the 80s/26.6-31.6°C.

Harvest spears daily once plants are in full production, twice a day if temperatures are in the 80s/26.6-31.6°C.

Q I live in northern Mississippi. Is asparagus a crop I can grow?

A Yes, you can. Asparagus makes a great perennial crop for gardeners throughout much of the United States and southern Canada. The only areas where asparagus won’t thrive are along the hot and humid Gulf Coast and in Florida. The plants require a dormant period so the crowns can rest before producing new growth for the next season. In California’s Imperial Valley, where temperatures reach 115°F/46°C, heat and drought send plants into summer dormancy.

Q Where should I plant asparagus?

A Plant rows of asparagus alongside, but out of, the main vegetable garden. The perennial crowns and wide-spreading roots are easy to damage accidentally when tilling or replanting annual crops. Site plants along the west or north side of the garden so their ferny, 5"/1.5 m-tall foliage won’t shade other crops. Raised beds are a good choice for asparagus, because they supply well-drained conditions and can be filled with rich soil. For best results start with certified disease-free, 1-year-old crowns, not seeds. Two-year-old crowns are more expensive and suffer more from transplant shock than 1-year-old crowns, so avoid them.

Q Which cultivars are best?

A Asparagus produces both male and female plants (such plants are said to be dioecious). Female plants spend a lot of energy producing berries and seeds. Since all-male hybrids don’t produce seed, they bear more spears than old-fashioned dioecious cultivars. New hybrids also resist or tolerate rust and other common asparagus diseases. Planting them in well-drained soil eliminates most disease problems. Planting all-male plants also eliminates the need to weed out less-productive, self-sown seedlings.

Q What’s the best way to plant asparagus crowns?

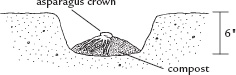

A Well-cared-for asparagus can produce for 15 to 20 years, and good soil preparation pays off. Ideally, have your soil tested, and adjust the pH if necessary before you buy plants. Prepare the soil in fall for spring planting by working in a good dose of compost and well-rotted manure. It’s also important to plant crowns as soon after you purchase them as possible. (Store them in slightly moist sphagnum moss if you can’t plant immediately.) In spring dig a 6"-7"/15.2-17.8 cm-deep trench with a slight mound at the bottom that runs down the center. Spread a handful each of bonemeal and wood ashes where each crown will go, then top that with a 1"/2.5 cm layer of compost. Soak asparagus crowns in compost tea for about 15 minutes before planting. Space out the crowns — just lay them on their sides, without spreading out the roots — 1'/.45 m apart in rows 3'-4'/.9-1.2 m apart. At first, cover them with just 2"/5 cm of soil. Gradually cover them with more soil as the shoots emerge, until the trench is full. The bed should stay moist but not wet.

Q My asparagus crowns never came up. What happened?

A Be sure the soil has warmed to 50°F/10°C before planting, because crowns won’t grow in cold — or wet — soil, which also exposes the plants to diseases. Plant in raised beds if your soil tends to be damp.

Q What do asparagus plants need to stay healthy?

A Asparagus crowns grow up toward the soil surface each year, and this results in smaller, less-tender spears. Prevent this by mounding 1"-2"/2.5-5.0 cm of soil up over the rows each spring. Add a layer of compost at the same time to enrich the soil. Adjust soil pH if necessary. Keep the soil evenly moist during the harvesting season, and cover beds with several inches of weed-free straw, chopped leaves, or grass clippings once the harvest has finished.

SEE ALSO: For more about pH, page 413.

Q Do I need to be careful about weeding my asparagus patch?

A Weeds can easily overrun an asparagus bed and cut productivity, so it’s very important to stay ahead of them. Keep the rows mulched, and pull weeds as regularly as you can. Pull carefully, or just cut weeds off at the soil surface during the harvest season to avoid damaging

These blue-black, yellow-spotted, ¼"/.63 cm-long beetles feed on spears in spring and cause the spears to become misshapen. The beetles and their wormlike gray larvae also defoliate plants in summer, eating leaves and stems once the plants fern out. Fall cleanup — removing foliage and mulch where these beetles overwinter — is the first line of defense. Cover beds in spring with floating row covers; handpick pests. As a last resort, spray with pyrethrins.

Asparagus beetle

emerging spears. In fall, cut down the asparagus foliage after it has yellowed, then cultivate shallowly to eliminate annual weeds. Don’t dig deeper than 2"-3"/5-7.6 cm, since the crowns are at most 6"/15.2 cm down. One option for dealing with weedy, self-sown asparagus seedlings is to dig up female plants (the ones that produce berries) and replace them with male ones, which bear more and don’t self-sow.

Q The first spears have come up in my new asparagus beds! Can I cut them?

A Resist the temptation to harvest from newly planted asparagus. The first year, don’t pick at all: Let the spears “fern out” so they can produce energy to support root growth. The second year, pick no more than two or three of the thickest spears from each crown. Let the rest go. The third year, harvest all the spears for about 4 weeks. The fourth year, once plants are fully established, harvest for 8 to as much as 12 weeks. Stop harvesting when more than half of the spears are less than the thickness of a pencil.

Q What’s the best technique for picking the spears?

A Many gardeners snap spears off, but it’s best to cut them by holding the knife parallel to the ground and cutting just below the soil surface. Be careful not to cut into the crowns.

Q How do I tell when the spears are tender and ready to pick?

A Look at the tips of the spears. Tight tips will be tender; loose ones may have turned woody. Pick spears every 2 or 3 days — daily or even twice a day if temperatures are above about 85°F/29.4°C.

Plunge cut asparagus spears into ice water right away to cool them down, then store them upright in the refrigerator in jars with 1"-2"/2.5-5 cm of water in the bottom. Loosely cover the spears with a plastic bag. They will keep for a week or more at 35°F/1.7°C.

Q My family loves white asparagus. How do I grow that?

A It’s easy to produce this gourmet treat. Start with any green asparagus, and use a hoe to mound loose soil up over the rows. Mix the soil with compost if it seems heavy, since a light, loose covering is best. Pile the soil up over the emerging spears, and continue adding more until they’re ready for harvest, to keep them in the dark. Gently remove the soil to harvest.

Q We never have enough asparagus. Is there any way to spread out the harvest?

A If you have plenty of gardening space, plant twice as many asparagus crowns as you need for your household. You’re going to designate half the plants for spring harvest, and half for fall. In spring, harvest spears as you normally would from the spring half of the bed. Let plants in the other half of the bed “fern out”; then in late July cut down their foliage. Water the bed deeply if the weather has been dry. The plants will produce new spears that can be harvested into the fall. Mulch the soil with chopped leaves or another light mulch so a crust doesn’t form that would be too hard for the spears to break through.

To keep the plants vigorous if you use this method, be consistent and always harvest spears in the spring bed in spring and the fall bed in fall. A fall-harvest schedule is harder on plants than traditional spring harvest, because because fall harvest puts stress on the crowns just before winter arrives. For this reason, fall-harvested plants may need to be replaced before spring-harvested ones will.

Q Are there other perennial vegetables I can plant near asparagus?

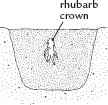

A Although used more like a fruit than a vegetable, rhubarb (Rheum rhabarbarum) is another popular perennial crop. Plantings will last 20 years and, like asparagus, can be hard to fit into a bed with other vegetables. Instead, site rhubarb alongside your vegetable garden, where it won’t suffer root or crown damage when you till or dig your garden.

Q How do I grow rhubarb?

A Plants need full sun to light shade and deeply prepared soil that’s well drained and rich in organic matter. Rhubarb grows best in areas with cool summers — summer highs averaging 75°F/24°C are ideal — and winter temperatures that fall below 40°F/4.5°C (roughly USDA Zones 2 to 8). For quickest results, start with root divisions, also called sets (for a family of four you’ll need about five plants). For each set, dig a site that’s 1½'-2'/.45-.6 m square, and work in plenty of compost and well-rotted manure. Space sets 4'/1.2 m apart and plant them with the buds 1" - 2"/2.5-5 cm below crown the soil surface. Once they sprout, mulch heavily with grass clippings or chopped leaves and water regularly — they need 1"/2.5 cm of water per week. In fall cut back the tops. Top-dress rhubarb plantings annu- Soil enriched with ally in spring and fall with compost.

organic matter

Q How do I harvest rhubarb?

A Don’t harvest any stalks the first year, and harvest only a few stalks the second year. After that, harvest as many as you want for 2 months, beginning in spring when they are about as wide as a finger. To keep the plants producing new leaves, remove flower stalks as they appear. To harvest leaf stalks, either cut or twist and pull them off. Plunge stalks into ice water to cool them, then store in plastic bags in the refrigerator. Be sure to cut off the leaves and compost them. Only the stalks are edible; the leaves are poisonous.

Install a trellis, teepee, or other support for pole beans before sowing seeds.

Install a trellis, teepee, or other support for pole beans before sowing seeds.

Wait to sow until the soil has warmed to at least 55°F/12.7°C.

Wait to sow until the soil has warmed to at least 55°F/12.7°C.

Cover seeded areas with floating row covers to protect seedlings from cold and insect pests.

Cover seeded areas with floating row covers to protect seedlings from cold and insect pests.

Q Which kind of beans should I grow, pole beans or bush beans?

A Many gardeners grow some of each type. Bush beans are easy to grow and produce a crop quickly. They’re self-supporting plants that do not need trellising. Pole beans, which take longer to bear, are climbing, twining plants that must be staked or trellised. Over the long run, they produce heavier yields and bear over a longer season than bush beans. Pole beans also take up less space in the garden; another advantage is that you don’t need to stoop over to pick them.

Q Help! The bean descriptions on seed packets and in catalogs are confusing. What do I need to know?

A Beans are a confusing lot, because catalogs refer to the many different shapes and sizes, along with harvest times. If you experiment a bit, though, you’ll find an interesting array of crops. All require basically the same care in the garden, and unless otherwise noted, all are available as either bush or pole beans.

SNAP BEANS. Also called green or string beans, these are picked when the pods are still young and tender. Some cultivars have yellow pods (these are also called wax beans); others are purple podded.

SNAP BEANS. Also called green or string beans, these are picked when the pods are still young and tender. Some cultivars have yellow pods (these are also called wax beans); others are purple podded.

FILET, OR FRENCH, BEANS. Also called haricots verts, these are snap beans bred to be picked while still very slender.

FILET, OR FRENCH, BEANS. Also called haricots verts, these are snap beans bred to be picked while still very slender.

ROMANO BEANS. These are broad, flat snap beans that have a rich, beany flavor.

ROMANO BEANS. These are broad, flat snap beans that have a rich, beany flavor.

SHELL BEANS. Also called horticultural beans or flageolets, these are beans that are harvested when the seeds have swollen but are still fleshy and the pods are tough and fairly dry, much like lima beans. Shell beans also can be left in the garden and harvested as dry beans.

SHELL BEANS. Also called horticultural beans or flageolets, these are beans that are harvested when the seeds have swollen but are still fleshy and the pods are tough and fairly dry, much like lima beans. Shell beans also can be left in the garden and harvested as dry beans.

Snap bean

Filet bean

Shell bean

Romano bean

DRY BEANS. Also called field beans, these are bush-type beans that are left in the garden until the seeds are hard and the pods are dry. They come in different colors and forms, including black beans, pinto beans, and kidney beans.

DRY BEANS. Also called field beans, these are bush-type beans that are left in the garden until the seeds are hard and the pods are dry. They come in different colors and forms, including black beans, pinto beans, and kidney beans.

Dry beans

Q What about lima beans? How do I grow them? I live near Peoria, Illinois.

A Lima beans (Phaseolus lunatus) are a heat-loving crop, and most experts recommend limas for gardens in Zone 5 and warmer. You’ll find both bush- and pole-type plants offered in catalogs. Bush-type plants begin bearing in 80 days, pole limas in 90. Since Peoria is in Zone 5, stick to growing bush limas; bush types are best in areas with less than 130 days of warm, summer weather. Planting short-season cultivars, warming the soil before planting, and protecting seedlings from cold in spring all help speed production. Both small- and large-seeded lima cultivars are available. Small-seeded limas are commonly called baby limas or butterbeans, while large-seeded ones are sometimes called potato limas.

Q I like to experiment a bit in my garden. Are there other kinds of beans I can try that are easy to grow?

A There’s a wealth of crops closely related to beans that are great choices for home gardens. Unless otherwise noted below, all are grown much like snap or pole beans. In addition to the ones listed here, consider trying adzuki beans (Vicia faba), lentils (Lens culinaris), mung beans (Vigna radiata), or winged beans (Psophocarpus tetragonolobus), also called asparagus peas.

ASPARAGUS BEANS (Vigna unguiculata var. sesquipedalis). Also called yard-long beans, these are heat-loving, subtropical pole-type beans with 1'-1½'/.3-.45 m-long pods with black seeds. Harvest when pods are young and tender, like a snap bean. Look for day-neutral cultivars, like ‘Liana’, which bear best in areas with long summers.

ASPARAGUS BEANS (Vigna unguiculata var. sesquipedalis). Also called yard-long beans, these are heat-loving, subtropical pole-type beans with 1'-1½'/.3-.45 m-long pods with black seeds. Harvest when pods are young and tender, like a snap bean. Look for day-neutral cultivars, like ‘Liana’, which bear best in areas with long summers.

CHICKPEAS (Cicer arietinum). These are also called garbanzo beans and Egyptian peas. They can be harvested when tender and used like a snap bean. To harvest dry garbanzos, pull the entire plant and lay them on a sheet or tarp in a dry, sunny spot until the pods have split to release their seeds.

CHICKPEAS (Cicer arietinum). These are also called garbanzo beans and Egyptian peas. They can be harvested when tender and used like a snap bean. To harvest dry garbanzos, pull the entire plant and lay them on a sheet or tarp in a dry, sunny spot until the pods have split to release their seeds.

COWPEAS (Vigna unguiculata ssp. unguiculata). Also called Southern peas and field peas, these plants thrive in hot weather. They’re also more drought tolerant than other beans and bean relatives: Don’t water them after the plants flower and pods have begun to form. Harvest when young and tender as snap beans, before the pods turn yellow as shell beans, or as dry beans. Blackeyed peas are one type of cowpea, but there are many other colors available. Most are bush-type plants, but pole cowpeas also are available.

COWPEAS (Vigna unguiculata ssp. unguiculata). Also called Southern peas and field peas, these plants thrive in hot weather. They’re also more drought tolerant than other beans and bean relatives: Don’t water them after the plants flower and pods have begun to form. Harvest when young and tender as snap beans, before the pods turn yellow as shell beans, or as dry beans. Blackeyed peas are one type of cowpea, but there are many other colors available. Most are bush-type plants, but pole cowpeas also are available.

FAVA BEANS (Vicia faba). Also called broad or horse beans, these need cool, moist conditions and are grown like peas. Harvest them young, like a snap bean, or at the shell- or dry-bean stage. In hot-summer areas, try sowing in fall for overwintering or harvest in spring or fall.

FAVA BEANS (Vicia faba). Also called broad or horse beans, these need cool, moist conditions and are grown like peas. Harvest them young, like a snap bean, or at the shell- or dry-bean stage. In hot-summer areas, try sowing in fall for overwintering or harvest in spring or fall.

SOYBEANS (Glycine max). Also called edamame beans, soybeans are easy to grow. Treat them as you would any bush beans, harvesting when the seeds are plump and nearly touching in the pods but before the pods begin to turn yellow.

SOYBEANS (Glycine max). Also called edamame beans, soybeans are easy to grow. Treat them as you would any bush beans, harvesting when the seeds are plump and nearly touching in the pods but before the pods begin to turn yellow.

Q How early can I plant beans?

A Beans are a warm-weather crop, and the seeds simply sit and rot if they’re planted in cold, wet soil in spring. Wait to plant until a week or two after the last frost date for your area. The soil temperature should be at least 55°F/12.7°C, but 60°F/15.5°C is better, and seeds germinate even faster in soil that has warmed to 75-80°F/24-26.7°C. (Fava beans are an exception to this rule: They prefer cool weather and are grown like peas.)

Q What’s the best spacing for beans? Are bush and pole beans grown the same distance apart?

A Bush and pole beans are grown at slightly different spacings. Bush beans are normally grown in rows, with seeds spaced 2"-4"/5-10 cm apart. Thin seedlings to 4"-6"/10-15.2 cm apart. Space individual rows 1½'-3'/.45-.9 m apart or, for a higher-density planting, arrange bush beans in wide rows with several plants abreast so each row is about 2'-2½'/.6-.75 m wide (set individual plants at the regular spacing within the row). Leave 2'-3'/.75-.9 m between the wide rows, so you’ll have room for tending the plants. Plant pole bean seeds 4"-6" apart and thin seedlings to 6"-9"/15.2-22.9 cm. Leave 3'-4'/.9-1.2 m between rows. Be sure to install poles or erect trellises before sowing to avoid trampling the soil to do it later.

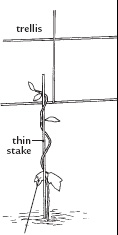

Q I want to grow my pole beans on trellises scattered around the garden. What’s the easiest way to do that?

A Plant your pole beans on hills with teepee-type supports. In this case, the number of plants will depend on how many supports are used to build the teepees. Build a hill large enough to accommodate the entire teepee, and use five to ten supports to build it. Plant two seeds per teepee support, and thin to one plant per support once the seedlings are up and growing. Leave 3'-5'/.9-1.5 m between hills.

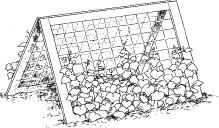

SEE ALSO: For details on how to set up teepees and trellises, pages 46-47.

Q How do I sow the seeds?

A Plant beans 1"/2.5 cm deep to 1½"/3.75 cm deep in light-textured soil that’s rich in organic matter, since it is generally warmer than heavier soil. For a late-summer crop of beans, sow seed slightly deeper than usual, about 2"/5 cm, to ensure they receive adequate moisture for germination. Since beans can take nitrogen from the air and use it to fuel their growth, there’s one other sowing step that you may want to take. If you haven’t grown beans before, purchase bacterial inoculant with your seeds. Beans need certain soil-dwelling bacteria in order for their roots to fix nitrogen, and applying bacterial inoculant ensures that the plants have plenty of bacteria available to form this mutually beneficial partnership. To apply it, moisten the seeds before planting and dust them with inoculant. After the first year, you’ll probably have enough bacteria in your soil to inoculate future crops without dusting the seeds.

SEE ALSO: For more information on inoculants, page 410.

Q How can I keep my garden from producing bushels of beans one week and none the next?

A Anyone who has grown beans before knows that they produce a bumper crop all at once. To spread out the bean harvest — and your picking time — one option is to plant small crops of bush beans every 10 or 12 days. Continue planting up to 8 or 12 weeks before the first fall frost date for your area. As one batch of plants stops producing, begin picking from the next. Or grow both bush and pole types. Bush beans produce a week or two before pole types start bearing, and pole beans continue producing long after the bush-type plants are finished.

Q What care do beans need to stay healthy?

A Beans don’t tolerate drought very well, so keep the soil evenly moist, especially while they’re germinating, flowering, and growing pods. Don’t overwater, though, because wet soil causes root rot and can cause flowers to drop off without producing pods. Once the plants are about to bloom, mulch them with 4"-6"/10.2-15.2 cm of light mulch. Plants don’t need extra fertilizer during the season.

Q How can I encourage my pole beans to climb their trellis?

A Bean seedlings sometimes need a little help to begin climbing a trellis; otherwise they’ll twine around each other or flop on the ground. When plants are still quite small, gently guide the vines around the trellis. Once they’re in contact, they’ll climb on their own. If your trellis starts several inches above the plants, try placing a thin garden stake next to each seedling that bridges the gap from ground to trellis. Then train the seedlings onto the stake to give them a leg up.

pole bean seedling

For the biggest overall harvest, pick beans daily or every few days. If you wait longer between harvests, some pods will mature, which causes the plants to stop producing new ones. Pinch or cut off the pods — pulling at them can uproot the plants.

Q When are beans ready to pick?

A For tender green beans, pick them when they are about as thick as a pencil and the seeds inside the pods are just visible as small bumps. Pick shell beans once the seeds are full size but still tender. With both green and shell beans, the more you pick, the more the plants produce. Leave dry beans on the plants until the seeds are hard and rattle in the pods, or cut the plants once the pods are yellow and hang them in a warm, dry place. Store dry beans in jars with a tablespoon of powdered milk folded in a paper towel to absorb moisture.

Q What do I do once my bush beans stop producing?

A As the plants stop producing new pods, either pull them up and add them to the compost pile or dig them under to enrich the soil where they’ve grown. If you’re digging the plants under, be sure to shred or chop up the foliage and stems first. Otherwise, they’ll take quite a while to break down. Replant the bed with another crop or mulch heavily for planting later in the season.

Q I’ve heard that beans are susceptible to many diseases. What can I do about them?

A The best line of defense is to plant resistant cultivars. Other steps that will reduce problems include:

If possible, don’t plant beans in a spot where other beans have grown in the past 3 years.

If possible, don’t plant beans in a spot where other beans have grown in the past 3 years.

Wait to sow seeds until the soil has warmed up.

Wait to sow seeds until the soil has warmed up.

Soak seeds in compost tea for 20 minutes before planting.

Soak seeds in compost tea for 20 minutes before planting.

To avoid spreading disease spores, don’t touch or work among wet plants.

To avoid spreading disease spores, don’t touch or work among wet plants.

Water moderately; wet soil yields weak, stunted plants and may cause flowers or pods to fall off.

Water moderately; wet soil yields weak, stunted plants and may cause flowers or pods to fall off.

Leave plenty of room between plants to encourage good air circulation.

Leave plenty of room between plants to encourage good air circulation.

Use soaker hoses for watering so leaves stay dry, because wet leaves make it easier for diseases to spread.

Use soaker hoses for watering so leaves stay dry, because wet leaves make it easier for diseases to spread.

If disease strikes, pull up and discard plants; do not compost them. Also, rake up and discard any leaves or mulch around the plants to reduce the possibility of problems in future years.

If disease strikes, pull up and discard plants; do not compost them. Also, rake up and discard any leaves or mulch around the plants to reduce the possibility of problems in future years.

SEE ALSO: For information on specific plant diseases, chapter 4.

Q What pests should I watch out for?

A The list of pests that love beans is long and includes aphids, various beetles — especially Mexican bean beetles — and leafhoppers. Installing floating row covers over bush beans when they’re still small keeps out all of these pests; in addition, they provide protection from cool temperatures early in the season.

SEE ALSO: For other options for dealing with common bean pests, page 153.

Q Help! My bean plants were doing well, but then they stopped producing. What happened?

A Diseases are one reason beans stop producing, but there are a few other causes for stalled pod production. Check the following:

UNPICKED MATURE PODS. Check carefully for missed pods and pick them. Plants stop producing if seeds mature.

UNPICKED MATURE PODS. Check carefully for missed pods and pick them. Plants stop producing if seeds mature.

HEAT AND DROUGHT. Flowers drop if the soil gets too dry or if the weather is too hot. Heat and drought may finish bush-bean production, but pole beans may resume production if you give them time and wait until conditions improve. To give pole beans a jump start, try removing pods and flowers, and cutting plants back to about 6'/1.8 m, then resume watering.

HEAT AND DROUGHT. Flowers drop if the soil gets too dry or if the weather is too hot. Heat and drought may finish bush-bean production, but pole beans may resume production if you give them time and wait until conditions improve. To give pole beans a jump start, try removing pods and flowers, and cutting plants back to about 6'/1.8 m, then resume watering.

RAIN-DAMAGED FLOWERS. Hard, pounding rain can damage flowers, which will cause plants to stop producing. Once they recover from the deluge, the plants will begin flowering and bearing again.

RAIN-DAMAGED FLOWERS. Hard, pounding rain can damage flowers, which will cause plants to stop producing. Once they recover from the deluge, the plants will begin flowering and bearing again.

Provide a spot in full sun for root crops if possible; if not, they’ll tolerate partial shade.

Provide a spot in full sun for root crops if possible; if not, they’ll tolerate partial shade.

Sow seeds in a bed with deeply dug soil free of rocks and roots.

Sow seeds in a bed with deeply dug soil free of rocks and roots.

Thin plants to encourage large roots to develop, but don’t bother to thin if you are growing plants for greens alone.

Thin plants to encourage large roots to develop, but don’t bother to thin if you are growing plants for greens alone.

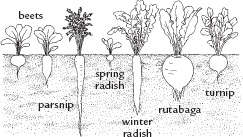

Q I know I can grow radishes in spring. Can I plant any other root crops then?

A Beets, radishes, parsnips, rutabagas, and turnips share a love for cool weather, and growing them when temperatures are cool is the secret to sweet, crisp roots. Start sowing spring radish seeds as soon as the soil can be worked, and plants will be ready for harvest in as little as 3 weeks. Fast, even growth is the secret to a good crop. Sow new crops every week or 10 days until daytime temperatures remain above about 65°F/18.3°C. After that, the roots will be bitter and tough, not spicy and crisp.

Beets and turnips also can be grown in spring, but they take slightly longer than radishes — from seed, beets take 1 to 2 months, turnips 1 to 2 months. Beets germinate in 45°F/7.2°C soil, but you’ll probably get better results if you wait a bit and sow both beets and turnips once the soil is at least 50°F/10°C. If you harvest turnips when they’re still small, you can sow successive crops every 10 days until warm temperatures (daytime highs in the low 70s/21-23°C) arrive to spread out the harvest.

Some long-season or winter radishes also can be sown at the same time as beets and turnips in spring. Look for bolt-resistant cultivars that mature in 40 or 50 days, and sow as soon as the soil can be worked.

Parsnips are the slowpokes of this group. Sow them in early to mid-spring for fall harvest.

Q My mom and dad always grew root crops, but I never paid much attention to how they took care of them. Are root crops hard to grow?

A Root crops certainly aren’t the rock stars of the vegetable garden, but gardeners who grow them love them. They all are easy to grow, need similar conditions, and, with the exception of radishes, are also quite nutritious. Here’s a quick “who’s who” of the root crops.

BEETS (Beta vulgaris, Crassa group. Goosefoot family, Chenopodiaceae). Round or globe-shaped, red beets are best known, but home gardeners also can grow beets with thick, carrot-shaped roots, as well as ones with yellow, white, or red and white flesh. Primarily grown for their sweet-tasting, tender roots, all beets have edible leaves, too.

BEETS (Beta vulgaris, Crassa group. Goosefoot family, Chenopodiaceae). Round or globe-shaped, red beets are best known, but home gardeners also can grow beets with thick, carrot-shaped roots, as well as ones with yellow, white, or red and white flesh. Primarily grown for their sweet-tasting, tender roots, all beets have edible leaves, too.

PARSNIPS (Pastinaca sativa. Carrot family, Apiaceae). These produce long, white, carrotlike roots that are nutty and sweet tasting.

PARSNIPS (Pastinaca sativa. Carrot family, Apiaceae). These produce long, white, carrotlike roots that are nutty and sweet tasting.

RADISHES (Raphanus sativus. Mustard family, Brassicaceae). White-fleshed, red-skinned radishes are the best known, but home gardeners have many other choices. Spring radishes (Radicula group) are fast growing, while long-season or winter radishes (Daikon group) produce larger roots and take longer to mature. Flavor varies from spicy to mild, depending on the cultivar and growing conditions, and both types have edible leaves.

RADISHES (Raphanus sativus. Mustard family, Brassicaceae). White-fleshed, red-skinned radishes are the best known, but home gardeners have many other choices. Spring radishes (Radicula group) are fast growing, while long-season or winter radishes (Daikon group) produce larger roots and take longer to mature. Flavor varies from spicy to mild, depending on the cultivar and growing conditions, and both types have edible leaves.

RUTABAGAS (Brassica napus, Napobrassica group. Mustard family, Brassicaceae). A cross between turnip and cabbage, this little-grown crop is called by a variety of names, including yellow, Canadian, Russian, or Swedish turnip, or just plain swedes. Plants bear edible greens and round yellow- or white-fleshed roots that feature a sweet, mild taste.

RUTABAGAS (Brassica napus, Napobrassica group. Mustard family, Brassicaceae). A cross between turnip and cabbage, this little-grown crop is called by a variety of names, including yellow, Canadian, Russian, or Swedish turnip, or just plain swedes. Plants bear edible greens and round yellow- or white-fleshed roots that feature a sweet, mild taste.

TURNIPS (Brassica rapa, Mustard family, Brassicaceae). This easy-care crop produces rounded roots that are sweet and mild tasting, plus nutritious, edible greens. Roots can be white, red, yellow, black, or bicolor (purple, red and white, or green and white).

TURNIPS (Brassica rapa, Mustard family, Brassicaceae). This easy-care crop produces rounded roots that are sweet and mild tasting, plus nutritious, edible greens. Roots can be white, red, yellow, black, or bicolor (purple, red and white, or green and white).

SEE ALSO: For information on carrots, another favorite root crop, pages 231-237.

Q How do I figure out when to plant root crops for a fall harvest?

A All of the root crops will provide a good fall harvest if you time your planting right. To determine when to start any of these crops for fall harvest, start with the days to maturity, which you’ll find listed on the seed packet or in catalog information. On a calendar, count back that number of days from the first fall frost date in your area to arrive at the date to sow your seeds.

For the best beets and spring radishes, harvest as quickly as they mature. For the best-quality turnips, rutabagas, winter radishes, and parsnips, the objective is to time crops so they are ready to harvest after a couple of light fall frosts, which improve both flavor and texture. That generally means mid- to late-summer sowing, but in warm climates, sow in fall for a winter crop. Keep in mind that while light frost improves texture and flavor, freezing destroys the roots. Dig them before a freeze or mulch heavily to protect the roots and lengthen the amount of time plants can be left in the garden.

SEE ALSO: For information on mulching, pages 105–109.

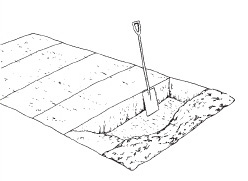

Q What do I need to do to prepare the soil for root crops?

A Root crops have similar soil preferences, and all will grow best in prepared vegetable garden soil that is well drained and rich in organic matter. However, a bit of extra soil preparation is necessary to ensure that the roots develop properly. To prepare the soil for any of these crops, dig deeply and incorporate compost or other organic matter throughout. While spring radishes grow fine in soil tilled to about 8"/20.3 cm, for other root crops dig soil and incorporate organic matter to a depth of 12-15"/30.5-38 cm or 18"-24"/45.7-61 cm for parsnips. Also, remove rocks, dirt clods, and roots, which cause forked or misshapen roots. Soil pH ranging from 5.5 to 6.8 is fine for radishes, while beets, parsnips, turnips, and rutabagas are happy in a pH of 6.5 to 7.5. Since heat and drought generally lead to small, woody roots, mulch is another essential for growing these root crops. Once plants are up and growing, cover the soil around them with organic matter — grass clippings, chopped leaves, or other light, loose mulch is fine — to keep conditions moist and as cool as possible.

Q I’ve tried parsnips before, but the seeds don’t germinate. Any advice?

A Parsnip seed is notoriously slow — it takes 3 to 4 weeks to germinate in 50°F/10°C soil. Try the following to get the seeds up and growing:

Soak seeds in water overnight before sowing.

Soak seeds in water overnight before sowing.

Sow thickly in rows or wide beds when the soil is still cool. In warm climates, from Zone 8 south, sow in fall for an early spring crop.

Sow thickly in rows or wide beds when the soil is still cool. In warm climates, from Zone 8 south, sow in fall for an early spring crop.

Sow parsnip seeds ½"/1.3 cm deep, then lightly sow some spring radishes ¼" deep in the same row or bed. The quick-germinating radishes help keep the soil from crusting and will be ready for harvest about the time the parsnip seedlings emerge. (Sow the radishes farther apart than you would normally, so you will be less likely to uproot any parsnip seedlings as you harvest the radishes.)

Sow parsnip seeds ½"/1.3 cm deep, then lightly sow some spring radishes ¼" deep in the same row or bed. The quick-germinating radishes help keep the soil from crusting and will be ready for harvest about the time the parsnip seedlings emerge. (Sow the radishes farther apart than you would normally, so you will be less likely to uproot any parsnip seedlings as you harvest the radishes.)

Keep the soil evenly moist until seedlings appear.

Keep the soil evenly moist until seedlings appear.

Cover the seeds with screened compost or packaged seed-germinating mix instead of garden soil. Or, cover the area with a very lightweight row cover.

Cover the seeds with screened compost or packaged seed-germinating mix instead of garden soil. Or, cover the area with a very lightweight row cover.

There’s no rule that says your root crops have to be planted in arrow-straight rows, and sometimes other arrangements are easier, faster, and more space efficient. Wide rows are one alternative, but simple block planting is another great option. Simply mark out a square or rectangular space that’s no more than about 3'/.9 m wide, so you can easily reach into the center of the bed to tend plants. Then scatter seed evenly across the entire block. Or mix tiny seeds with a bit of white sandbox sand so you can see where you’ve sown it. If you prefer, mark a grid on the soil surface with a trowel or other small hand tool — 3"x3" to 4"x4"/7.6x7.6 to 10.2x10.2 cm squares are fine — and then sow the same number of seeds in each square. Spread them out according to the proper spacing for the crop you are sowing.

SEE ALSO: For advice about wide rows, page 22.

Q Do I have to thin out root crop seedlings?

A That depends on whether you want roots, greens, or both. If you’re growing for greens only, sow at the rates listed below, and don’t worry about thinning.

If your goal is to harvest sweet, tender roots, be ruthless about thinning to the final recommended spacing. Thin when plants are still small — 2"-3"/5-7.6 cm tall — and cut the plants off rather than pulling them, to minimize damage to the remaining seedlings. All these crops grow well in rows spaced a foot/.3 m or so apart, or plant them in blocks and thin so plants are equally spaced on all sides. Mulch after thinning to suppress weeds and keep the soil cool.

Sow beets, radishes, and parsnips about ½"/1.3 cm deep; rutabagas and turnips ¼"-½"/.63-1.3 cm. Space and thin them as follows:

BEETS. Sow 2"-4"/5-10.2 cm apart in rows, and thin to 4"-6"/10.2-15.2 cm apart while still small. In most cases each beet “seed” is actually a small fruit that contains a cluster of seeds, so no matter how carefully you space them out, you’ll still need to thin. Cultivars described as single-seeded or monogerm bear one seed per “seed.”

BEETS. Sow 2"-4"/5-10.2 cm apart in rows, and thin to 4"-6"/10.2-15.2 cm apart while still small. In most cases each beet “seed” is actually a small fruit that contains a cluster of seeds, so no matter how carefully you space them out, you’ll still need to thin. Cultivars described as single-seeded or monogerm bear one seed per “seed.”

PARSNIPS. Sow seeds thickly, and thin to 4"-6"/10.2-15.2 cm when they are still small.

PARSNIPS. Sow seeds thickly, and thin to 4"-6"/10.2-15.2 cm when they are still small.

RADISHES. Sow seeds 1"/2.5 cm apart. Thin spring radish seedlings to 2"/5 cm; winter radishes 6"/15cm.

RADISHES. Sow seeds 1"/2.5 cm apart. Thin spring radish seedlings to 2"/5 cm; winter radishes 6"/15cm.

RUTABAGAS. Sow seeds 1"/2.5 cm apart and thin to 8"/20.3 cm.

RUTABAGAS. Sow seeds 1"/2.5 cm apart and thin to 8"/20.3 cm.

TURNIPS. Sow seeds 1"/2.5 cm apart and thin to 4"/10cm.

TURNIPS. Sow seeds 1"/2.5 cm apart and thin to 4"/10cm.

Q What else helps root crops to grow quickly?

A Consistently even soil moisture is crucial, since uneven soil moisture yields tough or stringy roots and bitter taste. To encourage fast growth, mulch root crops with several inches of grass clippings, compost, or other organic mulch to keep the soil cool and preserve moisture. Make sure plants get 1"/2.5 cm of water per week.

To keep flea beetles and other insect pests at bay, cover beets, radishes, rutabagas, parsnips, and turnips with floating row covers (see page 134) as soon as the seedlings emerge.

A Radishes, rutabagas, turnips, and parsnips don’t need supplemental feeding, provided they’re planted in well-prepared, compost-rich soil. Beets do benefit from supplemental feeding: Once their first true leaves are fully open, apply a low-nitrogen fertilizer every 3 weeks by sidedressing or foliar feeding. Or water weekly with a dilute solution of fish emulsion and kelp extract.

Q When do I harvest greens from these crops?

A You can harvest greens from all of the root crops except parsnips. Pick leaves when they are still young and tender. If you are growing for greens only, pull entire plants or pick as many leaves as you need. If you want roots, too, take only a few leaves from each plant, so there are enough left to fuel root growth. And don’t forget that as you thin your seedlings, you can save and wash the seedlings you clip to add to salads.

Q How can I tell when the roots are ready?

A Pick spring radishes just before or as soon as they reach full size, since they decline quickly. (To check on the size of any of these root crops, gently brush soil away from around the plant to reveal the top of the root.) Bigger isn’t better for any of the other crops either. Harvest when they are still small and tender: beets, 1"-2½"/2.5-6.3 cm wide; rutabagas, beginning when they are about 3"/7.6 cm across; turnips 1"-2"/2.5-5 cm wide. Harvest size for winter radishes varies depending on the cultivar, but small is best here, too. Dig parsnips anytime they’re large enough to use, but along with turnips, winter radishes, and rutabagas, they’re best if harvested after a few light frosts, so wait to harvest if you can.

Q What’s the best way to harvest?

A For most root crops, pulling them up gently works fine, provided the soil is loose. You’ll need to dig parsnips, which have fairly deep taproots. Dig any of these crops if you feel resistance when you try to pull them or the roots will simply break off in the ground. When digging, start outside the row to avoid bruising the roots. To store beets, parsnips, winter radishes, rutabagas, and turnips in the refrigerator, twist off the greens an inch or two above the root, and store in plastic bags. For longer storage (up to 6 months), pack the roots, dusted off but unwashed, in damp sand, peat, or sawdust at 32°-40°F/0°-4.4°C. (Check regularly, since low humidity causes shriveling.) All of these crops also can be mulched deeply and left in the garden for harvesting, as needed, at least until the ground freezes. You can leave parsnip roots in the ground over winter and harvest before new foliage emerges.

Q What’s wrong with my beets? They’re tough and woody.

A Tough, woody beets, turnips, and other root crops — along with bitter radishes — are all caused by poor growing conditions. Use these tips to ensure a tasty, tender harvest:

Keep the soil evenly moist, never too dry or too wet.

Keep the soil evenly moist, never too dry or too wet.

Harvest root crops when they’re still small and tender.

Harvest root crops when they’re still small and tender.

Incorporate plenty of compost into the soil at planting time.

Incorporate plenty of compost into the soil at planting time.

Time root crops so they either grow entirely or reach harvestable size when temperatures are cool.

Time root crops so they either grow entirely or reach harvestable size when temperatures are cool.

Q Something chewed slimy, winding tunnels in my turnips and radishes! How can I prevent this for the next crop?

A Cabbage maggots probably caused this damage: Look for tiny grubs in the roots. Infested plants often have yellowed leaves and frequently wilt during the heat of the day because the tunneling damages the plant’s root system. Pull and destroy any infested plants growing in your garden. To reduce populations apply beneficial nematodes before planting (follow package directions carefully). Also, at the end of the season make sure you remove all the roots in the garden. Otherwise, any larvae they contain can overwinter there.

Cabbage maggot tunnels in a turnip

Q My root-crop plants have little tiny roots, not big fat ones. What happened?

A Overcrowding is the most common cause when beets and other root crops don’t develop. It’s essential that you thin cut enough seedlings so that remaining roots don’t touch one another. Soil that’s too dry also prevents fleshy roots from developing. Be sure that plants receive 1"/2.5 cm of water per week.

Grow these crops in spring, fall, or whenever temperatures in your area are cool for at least 8 weeks.

Grow these crops in spring, fall, or whenever temperatures in your area are cool for at least 8 weeks.

Provide partial shade if temperatures are likely to be above 80°F/26.6°C during the growing season.

Provide partial shade if temperatures are likely to be above 80°F/26.6°C during the growing season.

Cover transplants with floating row covers to protect them from insect pests.

Cover transplants with floating row covers to protect them from insect pests.

Q What do all these vegetables have in common?

A For one thing, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, cauliflower, collards, kale, and kohlrabi all belong to one species, Brassica oleracea. They’re collectively referred to as brassicas or cole crops, and while the timing is slightly different from crop to crop, all need similar cultural conditions. Some brassicas are easier to grow than others, but all are vegetables that thrive in cool weather and are primarily grown as spring or fall crops throughout much of North America. They all thrive in soil with a pH of 6.0 to 6.8. Brussels sprouts, collards, kale, and kohlrabi tolerate soil that is as acid as pH 5.5, while cauliflower takes soil that ranges up to pH 7.4.

Q Can I grow broccoli, cabbage, and other brassicas in the same spot year after year?

A The downside of the close family tie of these crops is that they also share a variety of pests and diseases. For best results, rotate the location of brassicas every year. Ideally, you want to maintain a 3-year rotation, so you grow a brassica in a particular spot only once every 3 years. Even then, common diseases may be a problem, because they persist in the soil for many years. Brassicas tend to be heavy feeders, so plant them after a legume crop, such as peas or beans, or after a legume cover crop, such as clover.

Q I always grow a spring crop of cabbage. Can I add broccoli and cauliflower to my spring planting?

A Yes, provided you time crops so they’ll be ready to harvest before hot weather arrives. For spring crops it’s also a good idea to select short-season or early cultivars for spring plantings. Although you can direct sow, for best results start seeds indoors. Be sure to harden off all seedlings before transplanting them to the garden.

BROCCOLI. Start seeds 6 to 8 weeks before the last spring frost date; transplant 2 weeks before the last frost.

BROCCOLI. Start seeds 6 to 8 weeks before the last spring frost date; transplant 2 weeks before the last frost.

CABBAGE. Start seeds 6 to 9 weeks before the last spring frost; transplant 1 to 3 weeks before the last frost once the soil is at least 40°F/4.4°C.

CABBAGE. Start seeds 6 to 9 weeks before the last spring frost; transplant 1 to 3 weeks before the last frost once the soil is at least 40°F/4.4°C.

CAULIFLOWER. Start seeds no more than 8 to 10 weeks before the last spring frost; transplant 1 to 2 weeks before the last frost, once the soil is at least 55°F/12.7°C. Younger seedlings transplant best, and transplanting at 4 to 5 weeks is ideal.

CAULIFLOWER. Start seeds no more than 8 to 10 weeks before the last spring frost; transplant 1 to 2 weeks before the last frost, once the soil is at least 55°F/12.7°C. Younger seedlings transplant best, and transplanting at 4 to 5 weeks is ideal.

Q What spacing do brassicas need?

A Unless otherwise noted below, space rows 2'-3'/.6-.9 m apart.

BROCCOLI. In spring, space transplants 15"-18"/38-45.7 cm apart. Plants are a bit larger in fall, so space plants 18"-24"/45.7-61 cm apart.

BROCCOLI. In spring, space transplants 15"-18"/38-45.7 cm apart. Plants are a bit larger in fall, so space plants 18"-24"/45.7-61 cm apart.

BRUSSELS SPROUTS. Space transplants 18"-24"/45.7-61 cm apart.

BRUSSELS SPROUTS. Space transplants 18"-24"/45.7-61 cm apart.

CABBAGE. Space transplants anywhere from 12"-24"/30.5-61 cm apart, depending on the mature size of the head of the cultivar you are growing, in rows 1'-2'/.3-.6 m apart.

CABBAGE. Space transplants anywhere from 12"-24"/30.5-61 cm apart, depending on the mature size of the head of the cultivar you are growing, in rows 1'-2'/.3-.6 m apart.

CAULIFLOWER. In spring, space plants 15"-18"/38-45.7 cm apart. Space fall crops 18"-24"/45.7-61 cm apart.

CAULIFLOWER. In spring, space plants 15"-18"/38-45.7 cm apart. Space fall crops 18"-24"/45.7-61 cm apart.

Q Do spring transplants need any special care? I know they like cool weather, but it’s still really cold outside!

A While brassicas thrive in cool temperatures, they do need protection from really cold weather. Harden off transplants, and cover them with row covers in the garden, which protect them from cold wind and also keep pests at bay. Use a double layer of row covers at first for a bit of extra cold protection, then switch to a single layer for pest control only. Set broccoli, cabbage, and cauliflower transplants slightly deeper than they were growing in their pots to protect their stems.

Q How do I plan for a fall brassica crop? That means starting seeds in summer, right?

A Exact sowing schedules vary, depending on what cultivar you’re growing and where you live. To determine fall planting dates for crops that are to be harvested after the first fall frost, note the number of days to maturity on the seed packet or in the catalog. Also note whether that number is from transplanting or from seed sowing. Count backward that number of days from the first fall frost date in your area. Add 6 to 8 weeks if you are starting from seed and the days-to-maturity given is from transplanting. In general for brassicas, plan on sowing seeds for broccoli, cabbage, and cauliflower about 2½ to 3 months before the first fall frost date. Sow Brussels sprouts seeds indoors 3 to 4 months before the first fall frost. Move transplants to the garden about 6 to 8 weeks later.

Q My broccoli transplants always get so stressed by the heat, and so do the other brassicas. What can I do to ease the transition?

A While hardening off is important for all seedlings, brassicas that are transplanted into the garden in summer need extra TLC to weather the heat. Transplant on a cloudy day or during a spell of rainy weather. Try to look for a spot where the seedlings will be shaded by crops that are nearly ready for harvest so these other crops will be picked and cut down before frost. If you can’t find a naturally shaded spot, it’s a good idea to provide shade by propping bushel baskets over plants, covering them with burlap supported on wire hoops, or putting up temporary shelters of your own devising. Leave these temporary shelters in place for 2 or 3 days to give transplants time to adjust to the harsher conditions outdoors. Since these crops don’t tolerate heat and drought well, and even temporary drought stress can damage the crop, be sure the soil is evenly moist at all times. Test it by sticking a finger into the soil, and water if the top couple of inches feels dry — daily if necessary.

Q I live along the Gulf Coast, and our summers are much too hot for any of these crops. Is there a way that I can still grow them?

A Yes. All the brassicas, from cabbage and broccoli to kohlrabi, are great candidates for growing from winter to early spring in the Deep South. You can try sowing seeds of early or short-season cultivars in late winter, but for best results, start crops in late summer or fall for harvest from winter to very early spring. Since the soil is hot in late summer, it’s best to start seeds indoors and grow transplants. To spread out the harvest, plan on starting several small plantings in succession.

SEE ALSO: For more about succession planting, pages 59–61.

Q My garden is in Maine, and it freezes early here. Can I grow some of these crops in summer?

A Broccoli, cabbage, and other brassicas make fine summer crops in areas where average temperatures stay between 60-75°F/5.5-24°C. Broccoli and cauliflower are especially sensitive to warm temperatures, and probably won’t produce a good crop if exposed to a long bout of temperatures in the 80s/26.5-31.6°C. If your area receives spells of 80°F/26.5°C weather, it’s best to plan on a fall crop and use plastic row covers to protect plants from early freezes.

Q I’ve figured out my planting schedule for brassicas. Do I give all of them the same care after planting?

A Yes, for the most part they all need similar care. The soil should be kept evenly moist. To give your brassica transplants an extra boost, you may want to water them with compost tea once a week. All benefit from floating row covers, which prevent insect pest problems. Read on for special care and harvest tips about each crop.

Q What do I need to know about selecting cabbage?

A Cabbages come in green (white at the center of the head) and red. In addition to smooth-textured types, there also are Savoy cabbages, which have a handsome corrugated texture and great flavor. There are early, midseason, and late cultivars as well. Keep the following distinctions in mind:

EARLY. Also called spring cabbages, these take 50 to 60 days to mature from transplanting. They’re mild tasting, great for fresh use, tend to produce smaller heads, and are perfect for growing a quick crop of cabbage in spring.

EARLY. Also called spring cabbages, these take 50 to 60 days to mature from transplanting. They’re mild tasting, great for fresh use, tend to produce smaller heads, and are perfect for growing a quick crop of cabbage in spring.

MIDSEASO These cultivars take 70 to 85 days from transplanting to mature. They are the most popular main-season cabbages.

MIDSEASO These cultivars take 70 to 85 days from transplanting to mature. They are the most popular main-season cabbages.

LATE. These take at least 85 days to mature from transplanting. They have stronger flavor and are better for storage than early and midseason cultivars.

LATE. These take at least 85 days to mature from transplanting. They have stronger flavor and are better for storage than early and midseason cultivars.

Q What’s the secret to growing good cabbage?

A It’s important to time crops so that the heads develop when the weather is cool. Throughout much of North America, cabbage is grown in spring or fall. In the South and Southwest, it’s a winter crop. Since cabbages are largely water, regular watering is important; the soil should be evenly moist at all times. Watch transplants especially closely in summer (for fall crops) to make sure they aren’t stressed in hot weather. Mulch deeply. Stressed plants grow more slowly and may not form heads. Feed plants with a weak solution of fish emulsion for the first 3 weeks after transplanting or sidedress plants with well-rotted manure 3 weeks after transplanting.

Sidedressing cabbage

Q Is Chinese cabbage the same as regular cabbage?

A Although it’s grown much like regular cabbage, Chinese cabbage is actually more closely related to turnips. (Both belong to Brassica rapa; turnips are Rapifera group, Chinese cabbage is Pekinensis group.) Chinese cabbage is typically planted in fall, although newer hybrids that resist bolting can be sown in spring. Plant seeds outdoors on the last frost date in spring. For an autumn crop, sow 3 months before the first fall frost date. Sow seeds 3"-4"/7.6-10.2 cm apart and thin plants to 1'-1½'/.3-.45 m apart. Thin seedlings when they are still small to minimize stress, and keep in mind that any kind of stress leads to bitter flavor. Plants need plenty of water to thrive (they’re good candidates for soaker hoses or drip irrigation), as well as topdressing with compost manure or a high-nitrogen fertilizer and mulching so the soil will stay moist and cool. Smaller heads generally taste best, so don’t wait too long to harvest. Pick the leaves individually or cut entire heads. Harvest your spring crop before hot weather arrives and your fall crop before the first freeze.

Smooth-leafed cabbage

Chinese cabbage

Savoy cabbage

Q When do I harvest my cabbages?

A Begin to pick them as soon as they are hard and firm, even if the heads are only 5"-6"/12.7-15.2 cm across. Use a knife, and cut just below the firm part of the head. Leave the uncut leaves and stem intact, and your plants may form a second crop of small heads.

Q I don’t have room in my refrigerator for more than a couple of cabbage heads. How can I harvest cabbage at the right time and still have room to store it?

A There are two easy ways to spread out the cabbage harvest: Start small successive crops (as few as two or three plants) every 10 days to 2 weeks. To spread out the fall harvest, grow early, midseason, and late cultivars — the time they take to reach maturity will spread out the harvest for you. You can also plant small succession plantings of all three every 10 days. Close spacing also helps control size: For smaller heads, space cabbage transplants 12"/30.5 cm apart.

Q If I decide to plant broccoli and cauliflower in both spring and fall, do I plant the same cultivars or different ones?

A Cauliflower needs temperatures in the 60s/15.5-20.5°C in order for the heads to mature properly, and cool weather can be hard to come by in many parts of North America by late spring. If you get an early start by prewarming the soil and growing plants under a tunnel of plastic when the weather is still too cold, you may be able to harvest a crop before hot summer weather arrives. It’s far easier to grow cauliflower as a fall crop.

Read catalog descriptions carefully and note their recommendations. You’ll find cultivars recommended for quick or early spring crops that can tolerate a bit of summer heat. Heat-tolerant cultivars aren’t necessarily the best for fall crops, though, where the ability to withstand frost is paramount. There are also cultivars with disease resistance, and these can eliminate major headaches if diseases are prevalent where you garden. If you haven’t grown broccoli before, planting a mix of cultivars may be the best approach, since they perform differently. Nursery catalogs have recognized that this is a good approach, and you’ll find seed of hybrid mixes offered.

Q How do I get cauliflower ready for harvest?

A To produce mild-tasting, snowy white cauliflower, you need to blanch the heads or restrict light. Starting when the heads are about 2"/5 cm across (the size of a chicken egg), gather up the leaves that surround the central head and tie them together with twine. Gather gently, and tie just tightly enough to cover the heads without crushing the leaves completely. Use a bow or a slip knot, because you’ll need to check regularly for maturity. Once heads are 3"-4"/7.6-10.2 cm across, check daily and cut the heads while they are still tight and hard.

Blanching cauliflower

Q When is broccoli ready to pick?

A The heads, which are actually clusters of flower buds, are ready for harvest as soon as they are large enough to use. (Early on, when the head is small and first emerging, it may look yellow or yellowish green. Wait until it turns deep green as it enlarges.) After it has enlarged and turned green, be sure to cut the head before any part of it begins to turn yellow, which indicates the flowers are getting ready to open.

Q When I’m harvesting broccoli, is there a way I can encourage side shoots to form?

A Use a sharp knife to cut about 2"/5 cm below the main head. After that, check plants frequently, and harvest smaller side shoots as soon as they are large enough to use. Frequent harvesting encourages new side shoots to continue to form.

Cutting a broccoli side shoot

Q My grandmother used to grow collards and kale in her garden. Are they easy to grow?

A Both crops are easy and quite forgiving, since they tolerate both heat and cold. Both are best grown in fall. For a spring crop, sow collards outdoors 3 weeks before the last spring frost date; kale, as soon as the soil can be worked. Indoors, start transplants 6 to 8 weeks before the last frost date, and transplant 2 weeks before the last frost. For fall harvest, sow collards or kale outdoors about 3 months before the first fall frost. Thin to 1½'-2'/.45-.6 m apart, and start harvesting as soon as the leaves are large enough to use. Or pull entire plants at any stage, and succession plant new crops every few weeks to keep the supply coming.

Q Kohlrabi is the weirdest looking vegetable I’ve ever seen! Is it hard to grow?

A While it looks something like the vegetable world’s answer to a sea urchin, kohlrabi is actually a cross between a cabbage and a turnip. It’s an easy, fast-growing crop with edible leaves and a crisp, swollen base that’s tender and mild tasting. The bulbous stems are ready to harvest from 38 to 60 days from sowing, and it’s easy to start them right in the garden. In spring, sow seeds outdoors 4 to 6 weeks before the last frost date. They’re ideal fall crops: Begin sowing seed 8 to 10 weeks before the first fall frost. Space seeds 3"/7.6 cm apart, then thin to 6"/15.2 cm when the plants have a couple of true leaves. To spread out the harvest, plant small batches of seed every week or so in spring as long as the weather remains cool, then begin again in fall. In Zones 9 and 10, plant kohlrabi through the winter months.

Harvesting kohlrabi

Q Can I grow Brussels sprouts in spring?

A A touch of frost improves the taste and quality of the sprouts, so Brussels sprouts are best timed to mature after frost. Since they need a long season — they take about 3 months from transplanting — in areas with short seasons, you’ll still need to start plants in spring and transplant to the garden roughly just after tomatoes go into the ground to have them ready in time.

Q I remember Brussels sprouts from my mother’s garden, and they didn’t have leaves along the stems. Mine have lots of leaves. Do I need to pull them off?

A Sprouts form all along the main stem of a Brussels sprouts plant, one sprout just above where each leaf stem is attached. Remove the leaves below the sprouts as sprouts form. Also remove any leaves that turn yellow. It’s best to clip off the leaves with garden shears rather than pull them.

Cut off Brussels sprotus leaves as sprouts form.

Brussels sprouts will continue growing and producing sprouts until temperatures no longer rise above 50°F/10°C, and you can let them just keep growing until then. To encourage plants to ripen all at once, wait until the sprouts on the bottom 1'/.3 m of your plants are about ½"/1.3 cm in diameter, then cut off the top few inches of each plant. The rest of the sprouts will be ready to pick in about 2 weeks.

Q Do I pick all the sprouts at once? How do I tell when they’re ready?

A Sprouts are ready to use when they’re about ¾”/1.9 cm wide, and you can pick them over the course of several weeks. Be sure to harvest sprouts while they are under 1½"/3.8 cm and still hard. Smaller sprouts are likely to be the most tender. You can also cut the entire stalk and store it in a cool spot.

Q I know I’ve seen insects eating my cabbage and broccoli leaves. What kinds of pests and diseases do I need to watch out for?

A Brassicas do have their share of pests, but they are relatively easy to control if you use the tips below.

Use row covers to keep pests off transplants. Tuck the row covers in along the edges with soil to make sure pests can’t crawl underneath.

Use row covers to keep pests off transplants. Tuck the row covers in along the edges with soil to make sure pests can’t crawl underneath.

If your plants aren’t covered, handpick cabbage loopers and other caterpillars regularly.

If your plants aren’t covered, handpick cabbage loopers and other caterpillars regularly.

Clean up the garden thoroughly after each crop to prevent pests and disease organisms from surviving from one crop to the next or over the winter months.

Clean up the garden thoroughly after each crop to prevent pests and disease organisms from surviving from one crop to the next or over the winter months.

Include annuals and perennials with small flowers in your garden or in beds alongside it; these flowers attract beneficial insects that prey on aphids and other pests.

Include annuals and perennials with small flowers in your garden or in beds alongside it; these flowers attract beneficial insects that prey on aphids and other pests.

To prevent diseases, look for brassica crops with built-in resistance or tolerance.

To prevent diseases, look for brassica crops with built-in resistance or tolerance.

Don’t compost plants that show evidence of disease: Discard them in the trash.

Don’t compost plants that show evidence of disease: Discard them in the trash.

SEE ALSO: For more on pests and diseases, pages 146–162.

Q My broccoli plants produced heads, but they were tiny and runty looking. What caused this?

A This condition is called buttoning, and it also can be a problem with cauliflower. Buttoning is caused by seedlings that are exposed to cold temperatures at the wrong time, and fortunately, it’s preventable. Although really small seedlings can usually withstand cold temperatures, once they get larger (when stems are about as thick as a pencil) cold temperatures have a different effect, causing the transplants to produce small flower heads that never grow very large. Since exposure to a few days of temperatures in the 50s/10-15°C can cause buttoning, don’t rush to transplant broccoli or cauliflower if spring weather is especially unsettled. Protect plants that are already out in the garden when cold weather is predicted.

“Button” head on broccoli

Q My cabbage bloomed instead of forming a head. What happened?

A Like cauliflower and broccoli, cabbage seedlings can be accidentally tricked into flowering too soon. Avoid exposing cabbage plants to temperatures that are too cold — below 50°F/10°C. Protect plants already in the garden with hot caps, cloches, or other protection.

Q My cauliflower plants never did anything last summer. The transplants seemed really healthy, but they just didn’t grow. Any idea what happened?

A With all brassicas, it’s important to avoid stressing the plants, because stress slows down growth or causes plants to stop growing altogether. When hardening off transplants, don’t withhold water or nutrients. Instead, gradually expose them to increasing amounts of sunlight. Transplant on a cloudy day, and make sure the soil is evenly moist to minimize transplant shock. If you are aiming for an early start for your crop, plan on shielding transplants with cloches, hot caps, row covers, or other protection.

Q My cabbages were looking perfect, but then the heads cracked open! What happened?

A Too much water can cause heads to crack once they are near maturity. If there’s a spell of rainy weather near harvest time, use a spade to slice about 6"/15.2 cm into the soil halfway around each plant. This cuts the roots and reduces the amount of water the plant takes up. It also slows growth and allows you to postpone harvesting. This trick is also a good one to use on one-third to one-half of your crop if all the heads are maturing at once.

Q Sometimes a head of cauliflower separates into several sections as it develops instead of staying solid. What causes this?

A A period of drought followed by a period of wet conditions can cause cauliflower heads to separate. Keep the soil evenly moist, especially after heads begin to form. Mulch also helps even out soil moisture. (Heat and drought can also lead to bitter-tasting heads.) Or you may have simply waited too long to harvest. Either way, it’s worth it to cut the head and taste it. It is still probably usable. Leaves emerging from the center of the head can be caused by overmaturity, hot dry weather, or soil that contains too much nitrogen.

Q My latest batch of kale was bitter and tough. What’s the secret to the sweet, tender leaves I remember from my grandmother’s garden?

A Fast, even growth is the secret to the best-tasting collards and kale, so water regularly to maintain even soil moisture. Mulch also helps conserve soil moisture and hold weeds in check. One reason fall crops are better than spring ones is that taste improves after the plants are exposed to fall frost, so don’t hurry to harvest if cold weather threatens. In fact, both crops can be harvested in the snow. In areas with severe winters, protect the plants with a deep layer of straw mulch or with heavyweight row-cover fabric. In warm weather cool the leaves quickly after picking them by plunging them into ice water.

Q My kohlrabi has tough, hard stems that are bitter tasting. What did I do wrong?

A Tough kohlrabi stems can be a signal that your soil either is too dry or doesn’t drain well. But if the rest of your crops are thriving, perhaps the problem is hot weather, rather than your soil. Kohlrabi is happiest in cool weather, though it tolerates heat as long as it gets enough water. To make sure your crop isn’t suffering from moisture stress, work in 1" - 2"/2.5-5 cm of extra compost at planting time. Mulching helps preserve moisture, which is critical to a good-quality crop. It’s also important not to wait too long to harvest plants. Watch them carefully, and begin harvesting before the swollen stems become too large. In spring, cut them when stems are about 2"/5 cm in diameter; in fall they can reach 4"-5"/10.2-12.7 cm without being woody.

Prepare the soil deeply, removing rocks, soil clods, and other debris.

Prepare the soil deeply, removing rocks, soil clods, and other debris.

Sprinkle vermiculite, potting soil, or sifted compost over seeds instead of using garden soil when sowing.

Sprinkle vermiculite, potting soil, or sifted compost over seeds instead of using garden soil when sowing.

Keep the seedbed evenly moist, watering twice a day if necessary. Floating row covers also help conserve moisture.

Keep the seedbed evenly moist, watering twice a day if necessary. Floating row covers also help conserve moisture.

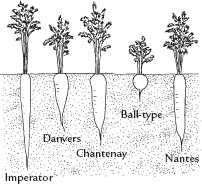

Q I’ve tried to grow long, pointed carrots like you see in the grocery store, but in my soil, they never do well! Any suggestions?

A While Bugs Bunny and many others like to snack on the long, narrow, tapered carrots called Imperators, they are not the best type for most home gardeners to grow. That’s because Imperator cultivars were developed for mechanical harvesting, meaning they not only need deep, perfectly loose soil, but also are tougher or less crisp than other types, so that they don’t break during harvest. Shorter-rooted types are a better choice for most home gardens. Try one or more of these:

NANTES. Nantes carrot cultivars are the most popular for backyard gardens. They are 5"-7"/12.7-17.8 cm long and grow in a somewhat wider range of soils. Nantes carrots are both sweeter and crisper than Imperators.