Rake the seedbed well before planting to remove surface stones and debris and break up clods. Sow seeds shallowly because some types need light to stimulate germination.

Rake the seedbed well before planting to remove surface stones and debris and break up clods. Sow seeds shallowly because some types need light to stimulate germination.TIPS FOR SUCCESS

Rake the seedbed well before planting to remove surface stones and debris and break up clods. Sow seeds shallowly because some types need light to stimulate germination.

Rake the seedbed well before planting to remove surface stones and debris and break up clods. Sow seeds shallowly because some types need light to stimulate germination.

Plant in full sun in cool weather but in light to partial shade during warm weather.

Plant in full sun in cool weather but in light to partial shade during warm weather.

Water deeply once a week in cool weather; water daily during warm and hot weather to prevent wilting and bitter-tasting leaves.

Water deeply once a week in cool weather; water daily during warm and hot weather to prevent wilting and bitter-tasting leaves.

Q How do I figure out what kind of lettuce to grow? There are so many different kinds!

A These days, lettuce can be one of the most beautiful crops in your garden, and it’s much easier and more intriguing to grow than in the days when iceberg lettuce was the salad-bowl staple. Here’s a guide to the full range of lettuce choices.

LEAF. These fast-growing, easy lettuces take only 45 to 60 days from seed to full-size plants and are also called cutting and looseleaf lettuce. Many cultivars are available, and leaf edges can be wavy to curly, very frilly, or lobed (like oak leaves).

LEAF. These fast-growing, easy lettuces take only 45 to 60 days from seed to full-size plants and are also called cutting and looseleaf lettuce. Many cultivars are available, and leaf edges can be wavy to curly, very frilly, or lobed (like oak leaves).

Leaf lettuce

ROMAINE OR COS. These form loose heads of long, broad leaves that mature in 50 to 70 days from seed.

ROMAINE OR COS. These form loose heads of long, broad leaves that mature in 50 to 70 days from seed.

Romaine lettuce

BUTTERHEAD. Also called Boston or bibb lettuce, these form a loose head and have exceptionally tender, succulent leaves. Plants take from 50 to 75 days to mature from seed.

BUTTERHEAD. Also called Boston or bibb lettuce, these form a loose head and have exceptionally tender, succulent leaves. Plants take from 50 to 75 days to mature from seed.

Butterhead lettuce

SUMMER CRISP. Also listed as French crisp lettuce, summer crisp lettuces are intermediate between Butter-head and Crisphead lettuce. They have crisp leaves that eventually form a firm head and generally take 50 to 75 days to mature from seed. Pick the leaves individually, or wait to harvest the entire head.

SUMMER CRISP. Also listed as French crisp lettuce, summer crisp lettuces are intermediate between Butter-head and Crisphead lettuce. They have crisp leaves that eventually form a firm head and generally take 50 to 75 days to mature from seed. Pick the leaves individually, or wait to harvest the entire head.

CRISPHEAD. Also called iceberg lettuces, these produce firm, solid heads of crisp, juicy leaves. Older cultivars need 75 days of cool weather to form heads, but newer ones released for home gardeners make this crop easier to grow. Still, crispheads ideally need about 2 months of days in the 60s/15.6–20.5°C to form a head. Batavian or summer crisp-type cultivars usually form heads (and will not bolt) as long as temperatures don’t exceed about 75°F/23.8°C during the day and stay above 50°F/10°C at night.

CRISPHEAD. Also called iceberg lettuces, these produce firm, solid heads of crisp, juicy leaves. Older cultivars need 75 days of cool weather to form heads, but newer ones released for home gardeners make this crop easier to grow. Still, crispheads ideally need about 2 months of days in the 60s/15.6–20.5°C to form a head. Batavian or summer crisp-type cultivars usually form heads (and will not bolt) as long as temperatures don’t exceed about 75°F/23.8°C during the day and stay above 50°F/10°C at night.

Crisphead lettuce

Q How about Popeye’s favorite treat? What are the best options for spinach?

A Smooth-leaved spinaches are probably the best choice if fresh eating for salads is your goal. The leaves are easier to clean and more tender than savoyed spinaches, which have crinkled and puckered leaves. Savoyed spinach leaves are harder to wash but tend to hold up better for cooking. Savoyed spinach cultivars also tend to tolerate more heat and have more resistance to diseases like downy mildew.

Savoy

Smooth leaf

Q My garden is in Cookeville, Tennessee, and I always have trouble with my spring spinach crop. The plants flower too soon, and that makes the leaves inedible. Is there a way to prevent flowering?

A Two factors cause spinach to bolt quickly in spring: increasing day length and bouts of warm weather (temperatures above 70°F/21.1°C encourage bolting). For a spring crop, try to get as early a start as possible, and look for cultivars that are bolt resistant. Plant spinach in a raised bed to ensure perfect drainage, and sow 8 weeks before the last spring frost date. To protect plants from hot weather that ends the harvest, use shade cloth to protect plants and harvest as soon as possible. The good news in areas with warm climates is that fall is perfect for growing spinach, since days are shorter and cool weather rules. In Zones 9 and warmer, winter is a great time for growing spinach, lettuce, and other cool-weather leafy crops like mesclun.

Q I’ve heard of mesclun. What is it?

A Mesclun, French for mixture, is actually a mix of leafy crops. Ideally, mesclun mixes include plants with a variety of leaf colors and shapes that make a pretty, flavorful salad. You’ll find that seed catalogs offer preblended mesclun mixes, as well as individual packets of a variety of crops that are typically included in mesclun.

In addition to lettuces and spinach, mesclun mixes contain other leafy crops, including the following: arugula (Eruca sativa), beets (Beta vulgaris, Crassa group), bok choy (Brassica rapa, Chinensis group), chervil (Anthriscus cerefolium), corn salad or mâche (Valerianella locusta, V. eriocarpa), endive (Chicorium endivia), garden cress (Lepidium sativum), miner’s lettuce (Claytonia perfoliata), mustard (Brassica spp.), orach (Atriplex hortensis), radishes (Raphanus sativus, Radicula group), sorrel (Rumex acetosa, R. scutatus), and swiss chard (Beta vulgaris, Cicla group).

Q Are mesclun mixes the best way to go, or should I blend my own?

A Seed companies that specialize in vegetables generally offer several mixes, and these may be the best way to go if you haven’t tried growing mesclun before. You’ll find mixes that are blended for taste, from mild to tangy. Other types are customized for growing at different times of year — cold-tolerant mixes for spring or fall and heat-tolerant crops for summertime harvests. Mixes are easiest to sow, and they tend to be less expensive, since you don’t have to buy seed packets of all the different crops in the mix. Try several to see which mixes perform and taste best for you.

You may also want to experiment with buying and growing the individual ingredients separately, and mixing them together after you harvest. This prevents the problem that sometimes occurs with premixed blends when one type of plant outcompetes the others, leaving you with more mustard than you’d like, for example. By buying seeds of the individual crops and planting small blocks of each, you can grow and harvest salads that feature the exact tastes and colors you prefer.

Q How do I plant a mesclun mix?

A It is as easy to grow as lettuce. Ideally, all the crops in a mesclun mix need the same growing conditions: rich, well-prepared soil and full sun or afternoon shade in warm weather. Typically, mesclun mixes are sown in rows, wide rows, or blocks and then harvested all together when the plants are only a few inches tall. Sow thickly — as close as 1"/2.5 cm between plants — and don’t worry about thinning, because you’ll be harvesting them before the plants grow large.

Q What kind of soil do I need for salad crops?

A It’s easiest to prepare soil for all your leafy crops at once. In general, lettuce, spinach, and other leafy crops prefer rich soil that’s evenly moist. If possible, work organic matter into the soil the season before you plan to plant — in fall for a spring crop and in spring for a fall crop. While lettuce is fairly adaptable and grows in a range of soils (pH 6.0 to 6.8 pH is ideal), spinach prefers soil that’s close to neutral (6.5 to 7.5) so testing and adjusting pH the season before is a good idea. Test soil the season before you plant so that amendments you add to adjust pH have time to work their effect. Yellow or brown

MUSTARDS (BRASSICA SPP.) ARE SPICY-TASTING leafy crops perfect for adding a bit of zing to salads. Most are more able to tolerate heat than lettuce and are well worth growing at any season for the tasty bite they add to salads. They can also be included in mesclun mixes. Pungent mustards include broad-leaved types that have large 12"–20"/30.5–50.8 cm-tall leaves that are crinkled or savoyed and tolerate both heat and cold, but there are many others. The mildest of the mustards is mizuna, which produces 1'/.3 m-wide rosettes of deeply cut leaves. Give mustards full sun in spring and fall but partial shade during the summer to help them withstand heat. Ordinary well-prepared vegetable garden soil is fine, and even moisture is essential. Plants grown in soil that is too dry will become very hot tasting.

If you develop a yen for spicy salads, you can turn up the heat by adding some of these crops, too:

Arugula (Eruca sativa)

Arugula (Eruca sativa)

Chives (Allium schoenoprasum)

Chives (Allium schoenoprasum)

Garlic greens (A. sativum)

Garlic greens (A. sativum)

Green onions (A. cepa)

Green onions (A. cepa)

Nasturtium leaves and blossoms (Tropaeolum majus)

Nasturtium leaves and blossoms (Tropaeolum majus)

Sorrel (Rumex acetosa)

Sorrel (Rumex acetosa)

leaf edges signal that plants are growing in soil that is too acid. To sweeten acid soil, follow directions from your soil-test results or dust with lime or wood ashes in fall before spring planting.

Q What’s the best way to plant lettuce?

A You can start lettuce right in the garden or sow plants indoors. Outdoors, sow seeds in a prepared seedbed about 4 weeks before the last spring frost date. Be sure to rake the soil carefully and remove surface clods and rocks, since lettuce seeds are very small. Thin plants once they have two or three leaves. Leaf lettuces generally need to be spaced 8"–10"/20.3–25.4 cm apart, other types 12"–16"/30.5–40.6 cm. Use the thinnings in salads.

Indoors, sow seeds in small flats or pots 3 weeks before the last spring frost date. Transplant seedlings to individual pots about 2 weeks later. Either way, cover the seed very lightly; ¼"/.64 cm is the recommended planting depth, because light aids germination.

Lettuce, spinach, and other leafy crops are perfect candidates for planting in blocks or wide rows, because the plants are fairly small, and it’s easy to reach over the row to tend the plants. You can broadcast seeds in a band and thin them or set seedlings out at their proper spacing.

Q What’s the best way to get my spinach crop growing?

A Spinach is also quite cold tolerant, and you can begin sowing seeds outdoors 4 to 6 weeks before the last spring frost date. Plant in a raised bed if your soil tends to be wet in spring. Since seedlings resent transplanting, it’s usually best to direct-sow outdoors. Soak the seeds in water for several hours before sowing to speed germination, then set them ½"/1.3 cm deep and 1"–2"/2.5–5 cm apart. Once seedlings are about 4"/10.2 cm tall, thin them to 6"/15.2 cm. Use the thinnings in salads. Sow new crops every week to 10 days until 1½ months before temperatures are in the mid-70s/23.3–24.4°C.

Q How do I plant mustards?

A Despite the fact that they’re heat tolerant, mustards are easiest to grow in spring or fall in all but the coolest portions of North America. Or grow them as a winter crop in the South and Southwest. For a spring crop, sow seeds directly in the garden 2 to 3 weeks before the last spring frost date. For fall, sow them in mid- to late summer. Set seeds ½"/.64 cm deep and 1"/2.5 cm apart, then thin when seedlings are several inches tall; the distance depends on the mature size of the cultivar(s) you are

To make salads even more colorful and appealing, plan on using a sprinkling of the many edible flowers commonly grown in gardens. Add them fresh to salads, either whole or as petals. Edible flowers include basil (Ocimum basilicum), borage (Borago officinalis), cornflowers (Centaurea spp.), dill (Anethum graveolens), fennel (Foeniculum vulgare), glads (Gladiolus spp.), honeysuckle (Lonicera spp.), lavender (Lavandula spp.), nasturtiums (Tropaeolum majus), pinks (Dianthus spp.), oregano (Origanum vulgare), marigolds (Tagetes spp.), pansies and violets (Viola spp.), peas (Pisum sativum ssp. sativum), pot marigolds (Calendula officinalis), roses (Rosa spp.), squash and pumpkins (Cucurbita spp.), and thyme (Thymus spp.). Be sure to harvest flowers only from beds where no chemical sprays have been used.

Garnish salads with edible flowers

growing. Add thinned seedlings to salads. You can start harvesting individual leaves as early as 4 weeks after sowing, or pull up entire plants when they reach maturity.

Q Our garden is in northern Pennsylvania, and the growing season ends far too soon! What can we do to extend the lettuce- and spinach-growing season?

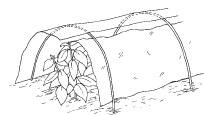

A As weather cools off in fall, lettuce, spinach, and other leafy crops mature more and more slowly, so you won’t have to rush to harvest the way you do when warm summer weather is on the horizon. The cool fall weather offers gardeners a big advantage, since the plants basically stop growing and you can plant a large crop all at once and then harvest over time. Instead of “going by” in a matter of days, as they do in spring and early summer, the plants last for 4 to 6 weeks in the garden, and you can harvest plants as you need them. Once temperatures drop into the low 30s/–1.1–.5°C, plan on protecting plants by covering them with row covers or erecting a plastic tunnel over the rows. Be sure to remove covers on warm days and replace covers at night.

A plastic tunnel extends the growing season

Q What salad crops tolerate summer heat? We still like to eat salad in summer!

A One way to extend the salad season beyond spring is by growing heat-tolerant cultivars of salad greens. (Catalog descriptions are a good guide to appropriate cultivars.) To give them as cool a spot as possible, plant on the north or east side of your house or in the shade of a trellis. Keep them mulched and watered, too. Here are some ideas for summer salad greens:

SWISS CHARD. Perhaps the best candidate for summer culture is Swiss chard (Beta vulgaris, Cicla group). Plants produce clumps of tall leaves on fleshy stems that can reach 2'/.6 m, but the leaves are ready to harvest beginning when they’re only 5"/12.7 cm tall. Either way, the leaves are nutritious and mild tasting. Swiss chard actually prefers cool weather, so sow plants outdoors 1 to 2 weeks before the last spring frost date. Water generously, especially once the weather is warm. Look for cultivars like ‘Rhubarb’ or ‘Bright Lights’ for a colorful addition to salads.

SWISS CHARD. Perhaps the best candidate for summer culture is Swiss chard (Beta vulgaris, Cicla group). Plants produce clumps of tall leaves on fleshy stems that can reach 2'/.6 m, but the leaves are ready to harvest beginning when they’re only 5"/12.7 cm tall. Either way, the leaves are nutritious and mild tasting. Swiss chard actually prefers cool weather, so sow plants outdoors 1 to 2 weeks before the last spring frost date. Water generously, especially once the weather is warm. Look for cultivars like ‘Rhubarb’ or ‘Bright Lights’ for a colorful addition to salads.

SUMMER SPINACH SUBSTITUTES. Other summer-salad crops include malabar spinach (Basella rubra), a tropical vine that can reach 6'/15.2 m and requires a trellis. Harvest new, very young leaves, which have a mild taste. Older leaves become mucilaginous. New Zealand spinach (Tetragonia tetragonioides) also tolerates heat but needs plenty of moisture to produce tasty leaves that are high in vitamin C. Pick young leaves and stem tips, since older leaves become tough and bitter. Finally, try vegetable amaranth (Amaranthus tricolor), which is also called calaloo and resembles coleus. Its nutritious, ovalto pear-shaped leaves taste like spinach. Pick young leaves and pinch plants to encourage branching.

SUMMER SPINACH SUBSTITUTES. Other summer-salad crops include malabar spinach (Basella rubra), a tropical vine that can reach 6'/15.2 m and requires a trellis. Harvest new, very young leaves, which have a mild taste. Older leaves become mucilaginous. New Zealand spinach (Tetragonia tetragonioides) also tolerates heat but needs plenty of moisture to produce tasty leaves that are high in vitamin C. Pick young leaves and stem tips, since older leaves become tough and bitter. Finally, try vegetable amaranth (Amaranthus tricolor), which is also called calaloo and resembles coleus. Its nutritious, ovalto pear-shaped leaves taste like spinach. Pick young leaves and pinch plants to encourage branching.

Q My wife and I can’t wait for our first homegrown salads in the spring. What can we do to have our plants ready to harvest as early as possible?

A Plan on starting some seed indoors and some out. Hardened-off seedlings can go into the garden at the same time you can sow seeds, which gives you a head start on your first crop. Seven or 8 weeks before that last spring frost, sow your first batch of seeds indoors. Sow additional batches indoors each week after that. Transplant your first batch of seedlings — and sow seeds — outdoors about 4 weeks before the last fall frost date. (Lettuce seedlings are fine outdoors provided temperatures remain above 30°F/–1.1°C.)

Lettuce matures fairly uniformly, so all the seeds you sow will be ready to harvest at about the same time. Keep that in mind, and sow small amounts at a time — perhaps a 1'–2'/.3–.6 m row, or a dozen transplants. Continue seeding and sowing until about a month before temperatures are routinely in the 70s/21.1–26.1°C. Plant spinach, mesclun, and other leafy crops the same way. You can use the same system to spread out the fall harvest.

Q What’s the right way to water lettuce and spinach?

A If possible, when the weather is cool, water these crops deeply once a week. Lettuce plants have shallow roots, though, and in warmer weather they probably will need watering every other day — daily in dry climates. The soil should be constantly moist but not wet or soggy. To avoid wetting the leaves, use soaker hoses if you can. Also, try to water in the morning — by midday at the latest — so there is plenty of time for the leaves to dry out before nightfall.

Q Do salad greens ever need fertilizer?

A In well-prepared soil, they probably will do just fine, but to speed growth even further, water with fish emulsion a couple of times during the season.

Q I live in Richmond, Virginia. We have nice spring weather, but the temperature can pop up into the upper 70s/25–26°C without much warning. What can I do to save my lettuce crop during hot spells?

A Hot weather usually brings an end to spring lettuce and spinach harvests, but you can buy your plants a little time nonetheless. Plan to shade plants, especially in the hot afternoons. Erect a framework over the rows with wire or PVC pipe and drape it with shade cloth, which comes in degrees of screening that block 25 to 50 percent of the light and heat. For Zone 7 areas, such as Richmond, try 50 percent shade cloth when temperatures get close to 80°F/26.7°C. Or prop up sheets of lattice or picket fencing on the west side of plantings. For lettuce and spinach that will mature about the time that hot weather arrives, plant on the north or west side of a trellis.

Even if you plan to use shade cloth, also sow bolt-resistant, heat-tolerant cultivars all through the spring season. That way, if a freak hot spell occurs and all your other lettuce bolts, you’ll still have some lettuce to eat. Also, be sure to mulch and water regularly (daily if necessary) to keep the roots moist and cool.

Lattice shading summer lettuce

Q How do I tell when my leaf lettuce and spinach are ready to harvest?

A You can begin harvesting leaf lettuce, spinach, and most other leafy crops as soon as the leaves are large enough to be picked. When picking leaves, pinch them off gently or cut them with scissors. Since the spring season is short, and hot weather causes plants to go from mature to bitter very quickly, pulling or cutting off whole plants is the best course of action in most areas. In fall, picking individual leaves is best, since the plants produce for several weeks. Once temperatures are routinely in the 30s/–1.1–3.9°C, harvest entire plants, since they won’t grow much more. To get lettuce at its best, harvest in the morning, when the leaves are most turgid.

Q When are crisphead lettuces ready for harvest?

A To determine when crisphead, romaine, and summer crisp lettuce is ready to pick, feel the heads. They should be firm and fully formed but probably won’t be as hard as grocery-store lettuce. If hot weather is in the forecast and you need to catch them before they bolt, you may want to go ahead and harvest even if the plants haven’t formed a head yet. Use a sharp knife to cut the heads off just above the soil surface.

A Begin harvesting about 6 weeks after sowing, when the plants are perhaps 6"/15.2 cm tall. Use scissors to cut bunches of leaves 1"/2.5 cm above the ground. After that, water the patch gently with compost tea. The plants will resprout for at least a second, and perhaps a third, harvest.

Q My spinach and lettuce always go to seed before I have a chance to pick them. What can I do to get to them in time?

A Both lettuce and spinach form flowers and go to seed in response to warm temperatures and increasing day length in spring. This is called bolting. Once temperatures exceed 80°F/26.6°C, the plants’ main stems begin to elongate, and flowers form very quickly. Once that happens, pull up your plants and compost them, because bolting causes the leaves to turn bitter. To avoid losing your crop, watch the weather forecast for your area. If hot weather threatens, act quickly to harvest all of your spinach and lettuce (or as much of it as you’ll be able to eat and store).

Q A friend gave me a flat of lettuce seedlings that were large and gorgeous, but they never grew much once I transplanted them to my garden. Is there something wrong with my soil?

A Probably not. The best lettuce seedlings are small — only 3 or 4 weeks old, in fact. Although they look tiny, young seedlings outperform large transplants almost every time.

Q I’ve had problems with slugs eating my lettuce, but what other pests do I need to watch out for?

A Slugs do love lettuce, and the slimy trails and ragged holes they leave in lettuce are none too appetizing. Two other pests to watch for are aphids and thrips. Aphids are small, rounded insects that feed by sucking sap from leaves. Their feeding causes curled leaves and stunted plants. Thrips rasp the leaves, leaving silvery streaks. They are very tiny insects and are hard to see. To check for thrips, hold a piece of white paper under a leaf and tap or shake the leaf. Thrips will show up as tiny black specks on the paper.

SEE ALSO: For tips on slug control, page 151; for thrip control, page 149; for aphid control, page 147.

Q My lettuce plants have been developing dark rusty-looking patches on the bottom leaves; then all the bottom leaves turn slimy and brown. What’s causing this?

A Look carefully at the rusty patches: If they are sunken and oozing, a disease called bottom rot is the culprit. Remove infected plants or pull off outside leaves that show signs of rot, and compost them. To prevent future outbreaks, add extra compost to your soil the next time you plant and/or plant lettuce in raised beds. Bottom rot is caused by a fungus that thrives in poorly drained conditions, and both compost and raised beds improve soil drainage. It also helps to reduce watering, allowing the soil surface to be slightly dry, as well as to water in the morning so plants have dried off by nightfall. Also, water remaining plants with compost tea to encourage beneficial microorganisms.

TIPS FOR SUCCESS

Let the soil and air warm up before planting; both should be at least 70°F/21.1°C, and nighttime temperatures should dip no lower than 60°F/15.6°C.

Let the soil and air warm up before planting; both should be at least 70°F/21.1°C, and nighttime temperatures should dip no lower than 60°F/15.6°C.

Give plants enough, but not too much, water for best flavor: Water if the plants wilt before midday or if the top 4"/10.2 cm of soil dries out.

Give plants enough, but not too much, water for best flavor: Water if the plants wilt before midday or if the top 4"/10.2 cm of soil dries out.

Pinch off shoot tips and extra fruit starting in midsummer to direct the energy of the plants to ripening existing fruit, especially in short-season areas. Melon plants bear about six fruits per vine, maximum; large watermelons, two or three.

Pinch off shoot tips and extra fruit starting in midsummer to direct the energy of the plants to ripening existing fruit, especially in short-season areas. Melon plants bear about six fruits per vine, maximum; large watermelons, two or three.

Q What’s the best kind of melon for a beginning gardener to try growing?

A The most popular melons to grow in backyard gardens are muskmelons — C. melo, Reticulatus group, for readers who want the proper name for these sweet treats. These range from 2–3 pounds/.9–1.4 kg and have tan, netted rinds and usually pale orange flesh. Ideally, start out with a cultivar bred for its resistance to or tolerance of diseases such as fusarium and powdery mildew. (Although muskmelons are also called cantaloupes, true cantaloupes have hard, warty-textured rinds and orange flesh.) Muskmelons mature in 70 to 80 days from transplanting. If you’d like to try some of the other types of melons, look for fast-maturing cultivars that mature in about the same number of days.

Q What about plant size? Are the bush-type plants as good as the full-size ones?

A In general, full-size or long-vined melons and watermelons produce better-quality fruit than compact or bush types. That’s because they generally have more leaves and thus more energy to produce fruit. If you have only enough room for compact or bush-type plants, don’t despair, though. Thin the fruit so that each plant bears only two melons. That ups the ratio of leaves to fruit and also helps plants yield sweeter fruit.

Compact or bush-type cultivars should be spaced about 2'/.6 m apart. Trellising is another option that works well for small-space gardens. For trellising, stick to small-fruited melons and icebox-type watermelons that produce smaller fruit — up to about 10 pounds/4.5 kg. Use strips of soft cloth to tie the vines to a sturdy trellis or fence. If you train melons on a fence, keep in mind that you’ll need to train the vines on the south-facing side of a fence that runs east and west to ensure that they’ll receive enough sunlight.

Q I live in Sacramento, California. With such a long growing season, I’d like to have some fun and experiment. What other kinds of melons can I grow?

A Gardeners in Zones 8 through 10 are the lucky ones when it comes to cultivating melons, because they have a long, warm growing season (temperatures in the 90s/32.2–37.2°C are ideal for melons and watermelons). Most commonly grown melons mature in 70 to about 80 days from transplanting; winter melons (C. melo, Inodorus group) such as casabas and crenshaws require much longer but are still easy to schedule whether you live in Sacramento or anywhere else in Zones 8 to 10. Here’s a rundown of the types of melons you may want to consider. All bear succulent, sweet-tasting fruit:

ANANAS MELONS. These oval, 2–4-pound/.9–1.8 kg melons have white flesh and a yellow-orange rind. Maturity is around 80 days from transplanting.

ANANAS MELONS. These oval, 2–4-pound/.9–1.8 kg melons have white flesh and a yellow-orange rind. Maturity is around 80 days from transplanting.

BUTTERSCOTCH MELONS. These are smooth-skinned melons with pale yellow-green or whitish green rinds and two-toned green and pale orange flesh. Maturity is 75 to 80 days from transplanting.

BUTTERSCOTCH MELONS. These are smooth-skinned melons with pale yellow-green or whitish green rinds and two-toned green and pale orange flesh. Maturity is 75 to 80 days from transplanting.

CASABA MELONS. These winter melons generally weigh 5 pounds/2.3 kg and have yellow rinds that are ribbed and rough with greenish flesh. Maturity is around 110 days from transplanting.

CASABA MELONS. These winter melons generally weigh 5 pounds/2.3 kg and have yellow rinds that are ribbed and rough with greenish flesh. Maturity is around 110 days from transplanting.

CHARENTAIS-TYPE MELONS. Usually weighing in at about 2 pounds/.9 kg, these have a smooth-textured gray-green rind and especially fragrant, extrasweet orange flesh. Maturity is

CHARENTAIS-TYPE MELONS. Usually weighing in at about 2 pounds/.9 kg, these have a smooth-textured gray-green rind and especially fragrant, extrasweet orange flesh. Maturity is

around 80 days from transplanting.

Charentais

CRENSHAW MELONS. A winter melon, crenshaws weigh about 6 pounds/2.7 kg and have smooth-textured, yellow-green skin and pale green or pale orange flesh. Maturity is 90 to 110 days from transplanting.

CRENSHAW MELONS. A winter melon, crenshaws weigh about 6 pounds/2.7 kg and have smooth-textured, yellow-green skin and pale green or pale orange flesh. Maturity is 90 to 110 days from transplanting.

Crenshaw

HONEYDEW MELONS. A winter melon that averages about 3 pounds/1.4 kg, honeydews have smooth, pale green to white rinds and pale green flesh. Maturity is 80 days or more from transplanting.

HONEYDEW MELONS. A winter melon that averages about 3 pounds/1.4 kg, honeydews have smooth, pale green to white rinds and pale green flesh. Maturity is 80 days or more from transplanting.

Honeydew

OTHER TYPES. Once you’ve grown some of the most popular types, you’ll probably want to experiment even further. Look through catalogs or on the Internet a bit, and you’ll find all sorts of melons to try, including white-fleshed Asian-type melons, tennis-ball-size single-serving melons with striped or mottled rinds, and melons that look just like lemons.

OTHER TYPES. Once you’ve grown some of the most popular types, you’ll probably want to experiment even further. Look through catalogs or on the Internet a bit, and you’ll find all sorts of melons to try, including white-fleshed Asian-type melons, tennis-ball-size single-serving melons with striped or mottled rinds, and melons that look just like lemons.

Q I live near Minneapolis, Minnesota, where we have a pretty short growing season. Can I still grow melons or watermelons?

A Provided you start with a short-season or early maturing cultivar — look for a days-to-maturity rating of 70 to 75 days from transplanting — you should be able to grow a crop of either melons or watermelons. Both melons and watermelons can be grown in gardens from Zone 4 south, but to get a jump on the season, gardeners in cooler regions should plan on starting seedlings indoors and prewarming the soil with clear or black plastic for a couple of weeks before moving seedlings outdoors. Cover plants with row covers in spring to keep them warm, and leave them covered as long as possible. If it’s still chilly when the first female flowers form, remove the covers, hand-pollinate by picking a male flower and carrying the pollen to the female flower yourself, and then put the covers back in place.

Q I just moved to northern Louisiana. Can I grow watermelons here?

A Any gardeners living in Zones 8 through 10 — and that certainly includes everyone in Louisiana — have the long, hot summers that watermelons require, and it’s in the South where the walloping big ones are produced. Watermelons typically take a minimum of 70 to 85 days from transplanting, which means at least 110 days overall from seeding to ripe fruit. Gardeners farther north can still grow them, but early maturing or short-season cultivars are easier to grow.

Q I could eat melons or watermelon every day of the year! How can I spread out the harvest?

A First, it’s important to know that all of the melons on a single vine ripen at about the same time, so you need to succession plant to spread out the harvest. Plant your first crop in spring — and start early by prewarming the soil and keeping plants under row covers. Then plant another batch of melons 3 to 5 weeks later. In the South, you have time for more crops. Look at the days-to-maturity listed on the cultivar you’d like to grow, and count backward from the first fall frost date to determine planting time. (It’s best to add a couple of extra weeks to your estimate so you have plenty of time to let the fruit ripen before cold temperatures arrive.)

Wherever you garden, if you have melons ripening in late summer or fall, be sure to cover the plants on cool nights, since temperatures below 50°F/10°C will stress plants. Use a couple of sheets, old blankets, or a tarp.

Q Do I plant seeds out in the garden or start melons and watermelons indoors?

A Anywhere the growing season is long and warm — from about Zone 8 south — sow seeds outdoors directly in the garden. Elsewhere, start them indoors 3 to 4 weeks before it’s time to transplant. Either way, soak seed in compost tea for 20 or 30 minutes before sowing, and plant seeds ½"/1.3 cm deep.

Keep in mind that neither melons nor watermelons transplant well. Since smaller seedlings transplant much more reliably than larger ones, don’t start too early. Ideal transplants have only two or three true leaves, and transplants that have four or more leaves or produce any tendrils have difficulty putting down roots once they’re moved to the garden. To ensure transplants that are the right size, you may want to wait and sow them indoors about 1 week before the last spring frost date. Follow these guidelines to help them make the move with flying colors:

USE INDIVIDUAL POTS to minimize transplant stress.

USE INDIVIDUAL POTS to minimize transplant stress.

SOW SEVERAL SEEDS IN EACH POT. Three-inch/7.6 cm pots are best. Peat or newspaper pots also help minimize transplant trauma.

SOW SEVERAL SEEDS IN EACH POT. Three-inch/7.6 cm pots are best. Peat or newspaper pots also help minimize transplant trauma.

Newspaper pots minimize transplanting stress.

SET SOWN POTS ON A HEAT MAT to maintain soil temperatures at 75°F/23.8°C.

SET SOWN POTS ON A HEAT MAT to maintain soil temperatures at 75°F/23.8°C.

WHEN SEEDLINGS ARE 2"/5 CM TALL, use scissors to clip off all but the strongest one in each pot.

WHEN SEEDLINGS ARE 2"/5 CM TALL, use scissors to clip off all but the strongest one in each pot.

BEGIN TO HARDEN OFF SEEDLINGS a week after the last frost date and transplant to the garden 2 to 3 weeks after the last spring frost date has passed. They’ll tolerate 60°F/15.6°C soil but really appreciate soil that is lots warmer — 85–90°F/29.4–32.2°C.

BEGIN TO HARDEN OFF SEEDLINGS a week after the last frost date and transplant to the garden 2 to 3 weeks after the last spring frost date has passed. They’ll tolerate 60°F/15.6°C soil but really appreciate soil that is lots warmer — 85–90°F/29.4–32.2°C.

COVER SEEDLINGS WITH FLOATING ROW COVERS to keep pests at bay and give them a little protection from cool temperatures. Be sure to remove row covers when flowers appear or hand-pollinate to ensure fruit set.

COVER SEEDLINGS WITH FLOATING ROW COVERS to keep pests at bay and give them a little protection from cool temperatures. Be sure to remove row covers when flowers appear or hand-pollinate to ensure fruit set.

Q What kind of soil prep is best?

A Melons and watermelons prefer well-drained soil that holds moisture well and is rich in organic matter. Since their roots normally reach a depth of 8"–10"/20.3–25.4 cm, dig the soil to at least 1'/.3 m — somewhat deeper than a shallow-rooted crop such as lettuce would require. Gardeners in dry areas should dig even deeper; this encourages roots to delve deeply and makes plants less susceptible to heat and drought. If you’re growing some of the longer-season melons, keep in mind that their roots can tunnel down several feet, so double-digging the soil may be worth the effort. Melons and watermelons do appreciate an extra dose of organic matter — in addition to the amount you apply annually as part of your overall soil improvement plan. Since they don’t go into the garden until late, there’s plenty of time to work 2"–3"/5–7.6 cm of well-rotted manure or compost deeply into the soil in spring before it’s time to plant. In dry regions, try to incorporate 4"–6"/10.2–15.2 cm of organic matter.

SEE ALSO: For information about double digging, pages 234–235.

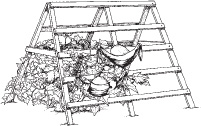

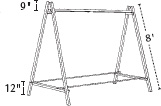

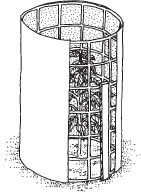

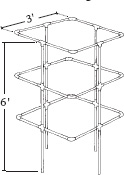

Q I want to trellis my melons. What type of structure would work best?

A Try making an A-frame trellis. Use wood, bamboo stakes, PVC pipe, or galvanized pipe to create the frame, and wire-mesh fencing or sturdy wooden cross-pieces for the surface. Make individual slings to support the fruit. Slings made from old pantyhose are ideal for this purpose, since they expand as the fruit grows. Slings made of mesh bags, bird netting, or old cotton T-shirts also are suitable. Try growing lettuce or other greens underneath it during the summer months, because the shade will help them cope with heat.

A-frame melon trellis

To create an extra-special planting site for melons or watermelons, dig a hole that’s 1'/.3 m deep and 1'/.3 m wide at each spot where you are planning a hill for planting. Fill the hole with compost or well-rotted manure, then use the soil you removed to build a hill on top of the site that’s 1'/.3 m tall and 2'–3'/.6–.9 m wide. Once their roots are long enough to reach down into this special cache, your plants will appreciate the extra dose of organic matter.

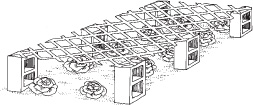

Q I remember that my grandfather always planted melons in hills in his garden. Is that the best way to plant them?

A While they will grow in rows, melons and watermelons are especially happy growing in mounds of rich, loose soil amended with compost and/or well-rotted manure. Sow about six seeds per hill, then thin to the three strongest plants when they are about 2"/5 cm tall. Space hills for melons about 4'–6'/1.2–1.8 m apart. Watermelons need more room — from 6'–12'/1.8–3.7 m. Bush-type melons don’t need quite as much space: Plant them about 2'/.6 m apart. Both crops also perform well in raised beds.

If you live in a dry climate, though, digging down is the best option, since raised mounds of soil dry out more quickly. Whether you grow your melons in hills, raised beds, or sunken beds, cover the plants with floating row covers to prevent pests from attacking the plants. If you prefer to grow in rows, space seedlings 3'–4'/.9–1.2 m apart in rows that are 5'–6'/1.5–1.8 m apart.

SEE ALSO: For planting in sunken beds, page 86.

Q How much water do melons and watermelons need?

A Water crops whenever the top 3"–4"/7.6–10.2 cm of soil are dry — just stick a finger down into the soil to test for moisture. Both crops routinely wilt on hot summer afternoons, but if the plants wilt before noon, they need to be watered. While they need a steady supply of water to grow and set fruit, stop watering about 2 weeks before the fruits are ready to harvest. Holding back water at this point makes the fruits sweeter tasting.

Q My melons don’t seem to be growing as fast as my neighbors’ are. Is there anything I can do to speed them up?

A Melons appreciate amended soil, but they also benefit from feeding during the growing season. From the time transplants or seedlings begin growing vigorously until the first female flowers appear, water plants weekly with a dilute solution of fish emulsion fertilizer (1 tablespoon/14.8 ml per 1 gallon/3.8 L of water).

Q I never know when to pick my muskmelons! What’s the secret?

A Harvesting muskmelons can be tricky. Since they don’t become any sweeter after harvest (they just get softer), it’s important to pick them at the peak of ripeness, not too early or too late. Muskmelons “slip” from the vine when they’re ripe, meaning that the vine naturally detaches from the fruit. Most gardeners pick just before this — at the half-slip stage, about 2 days before full slip — to ensure that the fruit won’t be overripe. To harvest at half slip, pick when gentle pressure at the point where the vine attaches to the melon detaches it. Another clue to ripeness is the color of the melon beneath the netting on the rind. When it turns from green to paler green or yellow, the melon is probably ready.

Q What about watermelons? I’ve tried thumping, but I’m not sure what to listen for!

A Harvesting watermelons is part art and part science. They don’t become any sweeter after they’ve been picked, so it’s crucial to get them out of the garden at just the right time. If you want to try the scientific approach, mark your calendar on the day the female flowers open fully. Then count off 35 days; that’s when the fruit will be ready. Here are some other cues to ripening:

The tendril on the stem nearest the fruit dries up and turns brown.

The tendril on the stem nearest the fruit dries up and turns brown.

The spot on the bottom of the fruit turns from white to yellow or creamy yellow in color. Try pressing a fingernail into the spot on the bottom of the fruit. It’s probably ripe if it doesn’t dent easily, the skin peels back easily with a little bit of scraping, and the flesh under the skin is greenish white.

The spot on the bottom of the fruit turns from white to yellow or creamy yellow in color. Try pressing a fingernail into the spot on the bottom of the fruit. It’s probably ripe if it doesn’t dent easily, the skin peels back easily with a little bit of scraping, and the flesh under the skin is greenish white.

The top of the watermelon turns dull in color and the contrast between the stripes diminishes. Thump your watermelon, and you should hear a deep, hollow sound.

The top of the watermelon turns dull in color and the contrast between the stripes diminishes. Thump your watermelon, and you should hear a deep, hollow sound.

Pay attention, and even make notes in your garden journal, and you’ll gradually become more expert at telling exactly when your watermelons reach the peak of ripeness. Cut the fruit from the plant, and leave a short stem. Pulling or yanking fruit damages the remaining vines.

Your fridge and countertops fill up quickly during harvest time, especially once tomatoes, squash, corn, and other vegetables begin to ripen. A healthy melon and watermelon crop makes the storage dilemma even more critical! Our ancestors stored all their homegrown bounty in the root cellar, which offered ideal cool (45–50°F/7.2–10°C), dark conditions, but suburban homes don’t come equipped with root cellars these days. Instead, consider setting up in a garage or basement an old refrigerator that’s used only during harvest time to keep produce. Or, if you have a cool basement, a set of metal shelving (the kind sold in home stores) makes a good temporary storage spot. A crawlspace may also provide the proper temperatures for storage: If so, add wood pallets or make a frame, and cover it with hardware cloth so you can store produce up off the floor.

Q How can I tell when honeydews, casabas, and true cantaloupes are ripe?

A Unlike muskmelons, most other melons won’t slip from the vine even when they’re fully ripe. Here are some tips to catch these crops at the peak of sweetness:

Watch the skin color. Rind color on honeydews and other melons changes when they are ripe, often to gold or white.

Watch the skin color. Rind color on honeydews and other melons changes when they are ripe, often to gold or white.

These melons generally have small hairs on the fruit that fall off when it’s ripe. Stroke the melon to feel for hairs. The skin should be slightly slippery and smooth.

These melons generally have small hairs on the fruit that fall off when it’s ripe. Stroke the melon to feel for hairs. The skin should be slightly slippery and smooth.

Smell the fruit on the end where the flower was originally located. You should be able to smell the sweet, fruity fragrance.

Smell the fruit on the end where the flower was originally located. You should be able to smell the sweet, fruity fragrance.

Q What can I do to prevent melon diseases?

A Look for cultivars bred for disease resistance or disease tolerance. Powdery mildew resistance is especially important in humid areas, because infected plants produce flavorless fruit. Use soaker hoses or drip irrigation if possible when watering melons so the foliage will stay dry, since this helps cut down on diseases. A thick layer of mulch helps too, and mulch also holds weeds in check and keeps the fruits clean.

Q Help! I’ve got flowers, but I don’t see any female ones! Did I do something wrong?

A Both melons and watermelons bear male flowers first. Be patient, and you’ll eventually see female flowers, which usually follow the males by about a week and have tiny melons formed just below the base of the flower.

Q My plants each formed a dozen or more melons, but most of them shriveled up and died. Why did this happen?

A Each plant generally ripens only three to four melons, and it’s actually best to remove surplus fruit. This directs the plant’s energy into ripening only the amount of fruit the plant can support. In midsummer, remove all immature fruit and flowers to direct the plant’s energy into ripening fruit that is already growing before cool fall weather arrives.

Q Ugh. I tried to harvest my perfect-looking melons, but they’re rotted on the bottom! What can I do to keep this from happening again?

A The easiest and best way to prevent rot is to get the fruit up off the soil surface so it will stay dry. Slip a board, a flat rock, or a piece of paver under each fruit when it is about half grown. This trick also speeds ripening, especially if you choose a prop that absorbs heat during the day and releases it at night.

Ripening melon propped on a board

TIPS FOR SUCCESS

Select a warm, protected site for planting.

Select a warm, protected site for planting.

Soak seeds overnight before sowing, or freeze them for 2 to 3 days to break the seed coat and speed germination.

Soak seeds overnight before sowing, or freeze them for 2 to 3 days to break the seed coat and speed germination.

Pick okra daily or every other day, about 4 days after the flowers fall, when pods are still quite small and tender.

Pick okra daily or every other day, about 4 days after the flowers fall, when pods are still quite small and tender.

Q I’ve never grown or eaten okra. What part of the plant do you harvest, and how do you cook it?

A Okra is one of those love-it-or-hate-it crops. It’s grown for the seedpods that follow the flowers, each of which opens for 1 day. The pods are picked in summer and are an essential ingredient in a traditional stew called gumbo. Okra pods also are served steamed or boiled, pickled, sliced, or breaded and fried. Their taste has been described as a cross between the flavors of green beans and oysters. Their texture is mucilaginous (meaning slimy).

Some gardeners also grow okra plants as an ornamental accent in a flower bed. The handsome plants bear yellow bell-shaped flowers with red centers, and the leaves are attractive, too. Plants range from 3'–6'/.9–1.8 m or more. Keep in mind that some people get a rash from working around okra’s spiny leaves. Plant a spineless cultivar or wear gloves and long sleeves when working around the plants.

okra blossom and pods

Q What are the secrets to success with okra?

A Okra plants appreciate richer soil than most vegetables, so work plenty of compost or well rotted manure into the soil, digging it in to a depth of 8"–10"/20.3–25.4 cm. Soak seed overnight in water and sow it 1"/2.5 cm deep after the soil has warmed up to at least 65°F/18.3°C. The seeds simply sit and rot if the soil is too cold, so don’t be in a rush to plant. Space seeds about 4"/10.2 cm apart in rows that are 18"/45.7 cm apart. Thin seedlings so they are 2'/.6 m apart when they’re about 8"/20.3 cm tall. Cut off the excess seedlings with scissors to minimize root disturbance to the remaining plants. Feed with a balanced organic fertilizer after thinning and again when they begin to form pods.

Q I live in Michigan, on the Upper Peninsula. Can I grow okra?

A There’s no doubt that okra is a heat-loving tropical crop, but as long as your garden is located in USDA Zone 4 or warmer, you can probably manage to fit in a crop. Look for an early- or short-season cultivar that begins to bear about 50 days from transplanting (most cultivars take 70 days to bear). A warm spot protected from winds is the best choice. It’s also best to prewarm the soil by covering it with clear or black plastic for 2 weeks before planting. Your harvest will be smaller than the bumper crops this plant produces in the South, however.

Q Can I start okra seeds inside?

A Yes, start them indoors if you live in the North or want an extra-early crop. Since okra resents transplanting, sow in individual pots 4 to 6 weeks before the last spring frost date. Harden off plants, and move them to the garden after all danger of frost has passed. Space plants 2'/.6 m apart.

Q How do I harvest the pods?

A Use scissors or gardening shears to cut them off when they are 2"–4"/5–10.2 cm long. Leave a short stem on each pod. Don’t wait until they get larger to harvest, because larger pods are tough. Use the pods as soon after you harvest as possible, since they decline quickly. And don’t put them in the refrigerator because the cold temperatures cause them to turn black.

Q I had flowers on my okra plants, but no pods formed. What’s up?

A While okra plants love heat, temperatures above 90°F/32.2°C can cause poor pollination and thus flowers that don’t yield pods. Wait for cooler weather to return. A few other cultural problems can cause poor pollination, including temperatures that dip below 50°F/10°C, dry soil, not enough light, and too much nitrogen.

TIPS FOR SUCCESS

Pay attention to regional schedules: In the South, plant short-day onions in fall; north of Zone 7, plant long-day cultivars in spring.

Pay attention to regional schedules: In the South, plant short-day onions in fall; north of Zone 7, plant long-day cultivars in spring.

Start weed control early, since weedy garden invaders can quickly overtake the delicate foliage of onions and their kin.

Start weed control early, since weedy garden invaders can quickly overtake the delicate foliage of onions and their kin.

Check your crop frequently to harvest at the right time — before the outer skins begin to break down. Dig up bulbs carefully to avoid damaging them.

Check your crop frequently to harvest at the right time — before the outer skins begin to break down. Dig up bulbs carefully to avoid damaging them.

Q I know that onions and garlic are related, but aren’t they grown differently?

A Onions, garlic, leeks, and chives are all alliums. While they’re not all grown exactly the same way, their cultural needs are similar. All are happiest in full sun, but they also tolerate partial shade and need similar soil conditions. The biggest difference is in the scheduling of each crop. Here are the basics on these savory crops:

CHIVES. Allium schoenoprasum. Hardy in USDA Zones 3 to 9, chives produce clumps of thin edible leaves and edible flowers as well. This easy-to-grow perennial is most commonly grown in herb and flower gardens.

CHIVES. Allium schoenoprasum. Hardy in USDA Zones 3 to 9, chives produce clumps of thin edible leaves and edible flowers as well. This easy-to-grow perennial is most commonly grown in herb and flower gardens.

GARLIC. Allium sativum. Grown primarily for its edible bulbs, garlic also produces tasty leaves that can be chopped and used like chives. The best crops of garlic are planted in fall and harvested in midsummer the following year. Plants are hardy from USDA Zones 2 to 10. Although garlic crops are typically harvested each year, they also can be left in the garden and grown as perennials as well.

GARLIC. Allium sativum. Grown primarily for its edible bulbs, garlic also produces tasty leaves that can be chopped and used like chives. The best crops of garlic are planted in fall and harvested in midsummer the following year. Plants are hardy from USDA Zones 2 to 10. Although garlic crops are typically harvested each year, they also can be left in the garden and grown as perennials as well.

LEEKS. Allium ampeloprasum, Porrum group. Another hardy onion-family plant, leeks can be grown in USDA Zones 2 to 10, although there are both hardy and nonhardy cultivars available. They’re planted in spring and harvested the same season. Leeks are biennials.

LEEKS. Allium ampeloprasum, Porrum group. Another hardy onion-family plant, leeks can be grown in USDA Zones 2 to 10, although there are both hardy and nonhardy cultivars available. They’re planted in spring and harvested the same season. Leeks are biennials.

ONIONS. Allium cepa, Cepa group. Biennials that are grown as annuals, onions can be a bit confusing, since there are many different colors and kinds to choose from. They can be grown throughout North America, but planting times and cultivars vary depending on day length. They’re generally planted in spring, although in warm climates they’re grown as a winter crop. Harvest time varies depending on the size and type you are growing.

ONIONS. Allium cepa, Cepa group. Biennials that are grown as annuals, onions can be a bit confusing, since there are many different colors and kinds to choose from. They can be grown throughout North America, but planting times and cultivars vary depending on day length. They’re generally planted in spring, although in warm climates they’re grown as a winter crop. Harvest time varies depending on the size and type you are growing.

Q What kind of soil do onions and garlic need?

A All these crops produce bulbs and thrive in loose, deeply dug soil that drains well but also retains moisture. While they’ll grow in average garden soil, for best results incorporate an extra 1"–2"/2.5–5 cm layer of finished compost. Make a 4"/10.2 cm-deep furrow between your rows and sprinkle about 1 cup/.23 L of a balanced organic fertilizer along 10'/3 m of row. Cover the furrow with soil, then plant; once your onions are large enough to reach the fertilizer, it will give them a boost.

SEE ALSO: For more soil management advice, chapter 2.

Q Anything else to keep in mind when preparing the soil?

A Onions and their kin all have grassy leaves, and since they don’t shade the soil very well, weeds can become a big problem relatively quickly. Remove weed roots and shoots when you prepare soil, and especially avoid tilling grass or other weeds into the soil, because the chopped-up roots will yield many more weeds. Once plants are in the ground, a 2"–4"/5–10.2 cm layer of mulch helps suppress weeds. To avoid causing the necks of the bulbs to rot, don’t push the mulch up closely around the onion-plant stems.

Q I’ve heard that some onions are short-day onions and others are long-day onions. What does that mean?

A Onion-bulb formation is triggered by day length. Short-day onions begin to produce bulbs as soon as they start receiving about 12 hours of daylight per day. Long-day onions need 13 to 16 hours of daylight to trigger bulb formation. Gardeners in the South should grow short-day onions. Long-day onions need to be planted for summertime production in the North — although we might assume differently, summer days are longer in the northern states and Canada than they are in the South. The 35th parallel of latitude is the approximate dividing line between long-day and short-day onion growing. This line runs just south of Raleigh, North Carolina, slightly north of Little Rock, Arkansas, through Albuquerque, New Mexico and near Santa Barbara, California.

There also are intermediate-day length cultivars that can be grown in the regions in between. Keep in mind that wherever onions are growing, it’s important that plants produce plenty of foliage before they receive the trigger to start forming bulbs; otherwise, the bulbs will be puny.

Q Deciding which onions to grow seems complicated! What do I need to know?

A In addition to red, yellow, and white onions, there also are gradations of shape and flavor (from sweet to pungent). For gardeners, though, the place to start is probably based on usage — whether the onions will be put in salads, sliced for hamburgers, or stored for later use. Here are the types you’ll encounter in catalogs:

GREEN ONIONS. Also called scallions and spring onions, green onions have fleshy stems that have little or no bulb or swelling at the bottom. (Most don’t belong to A. cepa, as common kitchen onions do. They’re A. fistulosum or crosses between A. fistulosum and A. cepa.)

GREEN ONIONS. Also called scallions and spring onions, green onions have fleshy stems that have little or no bulb or swelling at the bottom. (Most don’t belong to A. cepa, as common kitchen onions do. They’re A. fistulosum or crosses between A. fistulosum and A. cepa.)

Green onions

STORAGE ONIONS. Not surprisingly, these are hard onions developed especially for their ability to last in storage. They have a pungent taste but actually contain more sugar than milder onions. The pungency cooks away, leaving great taste. They also become milder in storage.

STORAGE ONIONS. Not surprisingly, these are hard onions developed especially for their ability to last in storage. They have a pungent taste but actually contain more sugar than milder onions. The pungency cooks away, leaving great taste. They also become milder in storage.

Storage onion

SLICING ONIONS. These are sweet and mild tasting but have softer flesh than storage types and do not last as long in storage. They’re also called Bermuda or Spanish onions. Slicing onions are usually lighter in color than storage types.

SLICING ONIONS. These are sweet and mild tasting but have softer flesh than storage types and do not last as long in storage. They’re also called Bermuda or Spanish onions. Slicing onions are usually lighter in color than storage types.

Slicing onion

PEARL ONIONS. These are small, mild-tasting onions usually used for pickling.

PEARL ONIONS. These are small, mild-tasting onions usually used for pickling.

Pearl onions

Q What are onion sets?

A Sets are small bulbs grown the previous year, and they produce bulbs quickly after planting, so they’re an easy option for growing a crop of onions. Garden centers and even many grocery stores sell onion sets in spring, but they usually offer only a couple of color choices. (If you live in the South, you’ll have to store sets in the refrigerator for fall planting.) Keep in mind that larger isn’t necessarily better. Sets should be no more than about ½"/1.3 cm in diameter. Larger ones are more likely to bolt, meaning they’ll go to seed rather than produce bulbs.

Starting your own onions from seed allows you a wider selection of varieties. Another option is to order onion transplants from catalogs or through the Internet (especially from onion specialists). They generally come bundled in groups, and they look like skinny scallions.

Q How do I plant sets? What about transplants?

A Plant sets or transplants 2"/5 cm deep and from 3"–6"/7.6–15.2 cm apart, depending on the final bulb size of the cultivar you are growing. Sets go in the ground pointed end up. It’s important to sort them before you plant: Discard any that are soft or have already begun to sprout, because these will likely bolt. Even if you are growing cultivars that produce large bulbs, plant them half the final recommended spacing distance, and then pull every other plant about 5 or 6 weeks later to use as green onions.

Q I live in Iowa. Should I plant onions in the spring?

A Plant onions in early spring north of USDA Zone 7. Start with sets or transplants of long-day cultivars, and set them out as soon as the soil can be worked, about 4 to 6 weeks before the last spring frost. The soil should be at least 40°F/4.4°C. Onions grow best when temperatures are between 55–75°F/12.7–23.8°C. Cool weather promotes healthy foliage growth. As the days grow longer, it signals the plants to start forming bulbs. At that point, the warmer the weather, the faster the bulbs grow.

SHALLOTS (Allium cepa, Aggregatum group) are an easy-to-grow gourmet treat. They’re perennials that are grown as annuals, and producing them is a snap compared to growing a crop of regular onions. Start with sets or transplants 2 to 4 weeks before the last spring frost date — or in fall if you’re located in the South. They need well-prepared moist soil, just like onions do. Space sets or transplants 6"–8"/15.2–20.3 cm apart. You can harvest the tops as you would green onions or garlic greens in 30 days by cutting a few leaves from each plant; don’t cut the new leaves, just the mature ones on the outside of the cluster. Harvest green shallots in about 45 days and mature ones in 90 to 130 days. Cure shallots by spreading them on newspaper in a dry spot out of direct sun for several days. Be sure to set aside the largest and best-quality bulbs for replanting the following year.

Shallots

SEE ALSO: For advice on soil preparation, page 316.

Q I live in South Carolina. When should I plant onions?

A In the South and Southwest, plant sets or transplants of a short-day cultivar in fall for harvest in winter or early spring. When cool winter weather arrives, mulch the plants, then uncover them in late winter or spring. You can also plant intermediate-day onions in early spring.

Q How do I grow onions from seeds?

A You can sow seeds outdoors in spring 3 to 4 weeks before the last spring frost date, but for best results start them indoors 10 to 12 weeks before the last spring frost date in pots. Sow thickly, and dust soil mix over the top of the seeds. Keep the soil moist and warm (above 65°F/18.3°C) until germination occurs. Thin or transplant to 1"/2.5 cm spacing, when the seedlings are still small. The ideal temperature for growth is 40–55°F/4.4–12.8°C, so if you can, move the pots to a cold frame. If the seedlings get too tall (about 5"/12.7 cm) use scissors to cut them back to about 3"/7.6 cm. Harden off the seedlings, and move them to the garden 2 to 3 weeks before the last spring frost date. If you want to plant onions in the fall, start seeds in late summer.

LIKE ONIONS AND GARLIC, leeks are easy to grow. They need well-prepared soil that’s deeply dug and rich in organic matter. As long as you’re following a yearly soil-improvement plan, they’ll probably do just fine. They do best in full sun but also grow in partial shade. If there’s a secret to growing top-quality leeks, it’s producing long white fleshy stems by blanching, or keeping them covered with soil. Blanching makes leeks tender and mild tasting.

There are two kinds of leek cultivars, hardy long-season ones and early or short-season types that aren’t hardy. Short-season leeks are planted in spring for harvest in summer or fall. They have a milder taste than long-season types and also don’t store as well. Long-season cultivars, which take 100 or more days to mature from transplanting, are planted in fall. They store well and also can be overwintered in the garden and harvested any time the soil isn’t frozen.

For spring planting, sow short-season leeks 8 to 10 weeks before the last spring frost date. For fall planting, sow long-season leeks 8 to 10 weeks before the first fall frost. Follow the steps on the next page for a bumper crop:

1. SOW THE SEEDS ½"/1.3 CM DEEP, and sow thickly in pots or flats, then set them on a heat mat or another spot that keeps the soil at 70°F/21.1°C.

2. TRANSPLANT SEEDLINGS TO INDIVIDUAL POTS or thin to 1"/2.5 cm apart when they are 3"/7.6 cm tall. (Deep pots, up to 6"/15.2 cm are best.) Keep them cool (60–65°F/15.6–18.3°C) until it’s time to transplant — around the last spring frost date.

3. THE EASIEST WAY TO TRANSPLANT is to use a broomstick or tool handle to poke holes in the soil — space holes 8"–10"/20.3–25.4 cm apart in rows 12"/30.5 cm apart — then stick individual leek seedlings into the holes. Set the seedlings up to the depth of their stem, just below where the leaves separate.

4. DON’T REFILL THE HOLES. Instead, water the plants gently, and let soil gradually fi ll in the hole around the seedlings. Hill up the soil a bit if too much stem seems to be exposed.

Planting a leek seedling

For fresh use in salads, begin harvesting leeks any time. For full-grown plants, wait until the stems are about 1½"/3.8 cm thick. To dig them, loosen the soil along the row and then pull the plants; otherwise, they’ll break off rather than come up. Cut off all except 2"/5 cm of leaves and store them in the refrigerator. For long-term storage, pack them in damp sand in a cold (32–40°F/0–4.4°C), dark spot.

Unlike onions and garlic, leeks keep well right in the garden for long periods if conditions are right. From the warmer portions of Zone 8 and south, you don’t even need to mulch the plants — simply harvest them as you need them. In colder areas, mulch leeks heavily when cold weather threatens in fall. To harvest, pull back the mulch and dig. From Zone 7 north, either dig the entire crop before the soil freezes or leave the plants mulched over the winter and harvest in late winter or early spring. Don’t delay once spring arrives, though, because the plants will bolt soon after they “wake up” from their winter sleep.

Q I love cooking with garlic. Do I just buy a few cloves at the grocery store and plant them?

A In most cases, garlic sold in grocery stores is treated to prevent sprouting, so you’re better off buying from a local garden center or by mail. If you are an aficionado, ordering by mail is best, since you’ll find a wealth of different cultivars to try. Or ask a friend or neighbor who already grows it to give you a few cloves to start your own patch.

Q What about starting garlic from seeds?

A Most garlic is reproduced vegetatively — that is, by dividing the bulbs — and is not grown from seed. Even the curling flower heads that some garlic bulbs produce in summer rarely produce seeds. Instead, they produce clusters of tiny bulbils, which can be saved and planted much like seeds. Bulbils take 2 years to produce bulbs large enough to use.

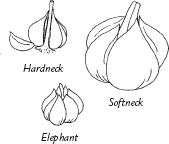

Q How do I decide what kinds of garlic to buy?

A While there are hundreds of cultivars, all fall into two basic types: hardneck and softneck garlic. Bulbs of hardneck garlic have a stiff stem at the center that’s surrounded by one or two rows of cloves. Each bulb produces a flowering stem in early summer that curls at the top. Softneck garlic has a soft stem in the center of the bulb. Softneck garlics store better than hardnecks, but hardneck garlics are hardier. Softneck garlic is the type to buy if you want to make garlic braids. Elephant garlic (Allium ampeloprasum) is a type of bulbing leek that is grown like garlic.

Hardneck Softneck Elephant

Q When’s the best time to plant garlic?

A The best time to plant is in fall, about 6 weeks before the soil freezes for the winter. Depending on where you live, that could be as early as September or as late as November. The plants overwinter and are ready for harvest in midsummer the following year. Fall-planted bulbs produce a larger, better harvest than spring-planted.

A Each bulb is made up of individual cloves. Separate the cloves and plant them pointed end up. If you have more cloves than you need for planting, use the smallest ones for cooking, and plant only the biggest ones. Don’t peel the papery covering off the individual cloves before planting. From Zone 7 south, plant cloves 1"–2"/2.5–5 cm deep; set them slightly deeper in the North — from 2"–4"/5–10.2 cm. Space cloves about 5"/12.7 cm apart. (Plant elephant garlic 3"/7.6 cm deep and 8"–10"/20.3–25.4 cm apart.)

Q Once I get my onions into the garden, what problems do I have to watch out for?

A Keep after weeds, which can quickly overtake onions. If onion maggots have been a problem in previous years, cover the plants with floating row covers until they’re ready to harvest; install wire hoops to support the row covers so they won’t flatten the foliage. If the bulbs push up out of the ground, cover the tops lightly with mulch to protect them from sunscald. Give plants 1"/2.5 cm of water a week.

Q My garlic has produced curving flowering stems. What do I do with them?

A Garlic doesn’t produce pretty flowers like ornamental onions do, and many gardeners simply cut them off, because they take energy away from bulb formation. Don’t just compost them, though. Cut them while they’re still young and tender, chop them up, then mix them with olive oil. Use the mixture to flavor sauces and other foods.

Q How do I know when my onions are ready to dig?

A Begin harvesting green onions or scallions grown from sets when they’re about 6"/15.2 cm tall. On full-size onions, wait until the leaves turn yellow or brown and fall over. (If some of your onions don’t turn yellow and the leaves don’t bend over, harvest them and use them fairly quickly, because this indicates they probably won’t store well.) Once the tops are completely brown, dig or pull the onions. If you have to harvest your onion crop while some plants still have green leaves, go ahead and dig, but be aware that onions that are dug while the leaves are still green won’t store well. Spread harvested onions out and let them dry in a bright spot out of direct sun. For maximum onion storage, cure the bulbs by spreading them out on screens in a well-ventilated spot until the outer skins are papery and the tops are completely brown. Then cut off the tops and store them in a cool (35–40°F/1.7–4.4°C), dry, dark spot.

Garlic produces flat leaves, unlike the round leaves borne by chives and onions. They’re tasty, though — like mild garlic — and can be chopped and used like chives. Harvest only a couple of leaves from each plant, or your plants won’t produce very large bulbs. Or plant a separate patch of garlic for leaf production only, and you can pick all the leaves you need. Dig up the clump in midsummer to divide and replant if it becomes too crowded. Picking foliage is an option if you missed planting your fall crop for some reason — just plant your cloves in spring and pick all the leaves you like, since the spring-planted bulbs won’t enlarge much anyway without the cold treatment that overwintering in the garden supplies.

Q When should I dig garlic bulbs?

A Harvest fall-planted garlic in midsummer, when about three-quarters of the leaves have turned yellow. When digging, start at the outside of the row and dig carefully, since bulbs that are damaged by spades or digging forks won’t store well. It’s best to dig a plant or two and examine the bulbs. If the bulbs are still mostly solid and it’s hard to separate the cloves, leave them in the ground and test another plant in a week or two. Ripe bulbs should have developed skins that separate the individual cloves, but the outer skin should still be quite firm and intact. Set aside the largest cloves from your harvest, and store them for planting the following year.

Q What’s the best way to store garlic?

A All garlic needs to be cured before it can be stored. Spread freshly dug garlic plants on screens or tie them loosely in bunches and hang them. For either method, leave the roots and tops attached, and put the garlic in a warm, dark spot that has good air circulation. The bulbs should be dry in 2 or 3 weeks. After that, cut off the roots and tops, and store them in a cool (40–50°F/4.4–10°C), dry spot.

Q My onion bulbs split while they were still in the ground. What happened?

A Extremely dry soil can cause bulbs to split. For best growth, keep the soil evenly moist, but avoid sopping-wet soil. Ideally, the soil should be moist like a damp sponge that’s been wrung out. Applying a thick layer of mulch — straw or grass clippings are fine — helps keep moisture in the soil and prevents weeds.

Q My plants had loads of leaves, but they have dinky little bulbs. What’s going on?

A Onions appreciate doses of compost or a balanced organic fertilizer early on, but withhold extra fertilizer starting about 2 months before harvest. Otherwise, they’ll keep making leaves and won’t produce bulbs.

Q My onions went to seed, and they didn’t produce bulbs. What did I do wrong?

A Onions that are exposed to cold temperatures tend to bolt (go to seed). In this case, cold means a few days below 50°F/10°C or even a couple of days below 30°F/–1.1°C. Don’t be in a rush to plant if spring weather is unsettled. Onion sets that are too large also tend to bolt. When planting, sort your sets and plant the larger ones all together with the bulbs nearly touching, then harvest them as soon as they’re ready to use as green onions.

TIPS FOR SUCCESS

Choose a site with full sun and good air circulation.

Choose a site with full sun and good air circulation.

Plant in early spring or late summer so plants can grow while the weather is cool.

Plant in early spring or late summer so plants can grow while the weather is cool.

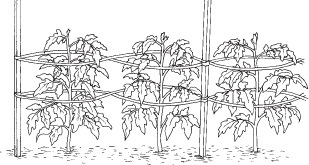

Install a trellis or other supports at planting time.

Install a trellis or other supports at planting time.

Q I want to grow peas, but I’m not sure how to get started. Are snow peas and edible pod peas the same thing as regular peas (the kind I usually buy canned or frozen)?

A Peas are great garden plants, whether you choose old-fashioned shelling types or snap peas, which you eat pod and all. Growing techniques are the same whatever type of pea you decide to grow, but the timing of harvest varies. Whatever you decide to grow, be sure to choose cultivars that offer disease resistance. Here’s a rundown of types to try:

SHELLING PEAS. Also called English and green peas, these have inedible pods. Harvest when the pods are full size and the peas are round and full. Pick before the pods begin to turn yellow, or the peas will be starchy and past their prime. Baby peas, or petit pois, are small-seeded green peas. There are cultivars developed specifically to be harvested as petit pois, but any pea that’s picked early can be used this way.

SHELLING PEAS. Also called English and green peas, these have inedible pods. Harvest when the pods are full size and the peas are round and full. Pick before the pods begin to turn yellow, or the peas will be starchy and past their prime. Baby peas, or petit pois, are small-seeded green peas. There are cultivars developed specifically to be harvested as petit pois, but any pea that’s picked early can be used this way.

SNOW PEAS. Also called sugar or Chinese peas, these should be picked when the edible pods are large and flat, but before the peas inside them have begun to swell.

SNOW PEAS. Also called sugar or Chinese peas, these should be picked when the edible pods are large and flat, but before the peas inside them have begun to swell.

SNAP PEAS. The newest crop in the pea lineup, these originated as a cross between shelling and snow peas. They bear crisp pods and sweet peas, both of which are edible. They are sweetest when the peas inside the pods are round and full.

SNAP PEAS. The newest crop in the pea lineup, these originated as a cross between shelling and snow peas. They bear crisp pods and sweet peas, both of which are edible. They are sweetest when the peas inside the pods are round and full.

DRY PEAS. These are left in the field until the pods are brown, then are shelled, dried, and stored. They’re also known as soup or field peas.

DRY PEAS. These are left in the field until the pods are brown, then are shelled, dried, and stored. They’re also known as soup or field peas.

SEE ALSO: To learn about other types of crops that are sometimes called peas, pages 187–188.

Q I know that peas should be planted early, but how early?

A The standard recommendation — to plant as soon as the soil can be worked in spring — can be confusing. In general, sow seeds about 5 weeks before the last frost date for your area. They’ll germinate, albeit slowly, in 40°F/4.4°C soil but may rot at lower temperatures. Seeds germinate quicker in 50–60°F/10–15.6°C soil. For extra-early planting, warm the soil by covering it with black-plastic mulch for 2 weeks before planting.

Q What’s the best way to plant peas?

A Soak pea seeds in compost tea for 20 minutes before planting, and set seeds 1" - 2"/2.5–5 cm deep and 2"–3"/5–7.6 cm apart in a prepared garden bed or row. Space rows 3'/.9 m apart or plant two rows 6"–8"/15.2–20.3 cm apart with strings or light trellises running down the center. Don’t worry about thinning, since peas don’t mind crowding. Mulch plants when they are about 3"/7.6 cm tall to keep the soil cool.

A Peas have tendrils, which attach themselves to strings, small-gauge wire, netting, and each other. Climbing or vining peas definitely need a trellis or strings to climb on. They make efficient use of garden space and can climb to 8'/2.4 m. A narrow A-frame trellis made from 2×2s/38×38 mm and strung with twine or covered with netting works well.

Dwarf types actually benefit from some support to keep the pods up off the ground. Stick pea stakes — pieces of twiggy brush — along the row, or consider installing short trellises along the rows.