In order to be noticed at the exhibition, one has to paint

rather large pictures that demand very conscientious

preparatory studies and thus occasion a good deal of

expense; otherwise one has to spend ten years until

people notice you, which is rather discouraging.

Frédéric Bazille, 18661

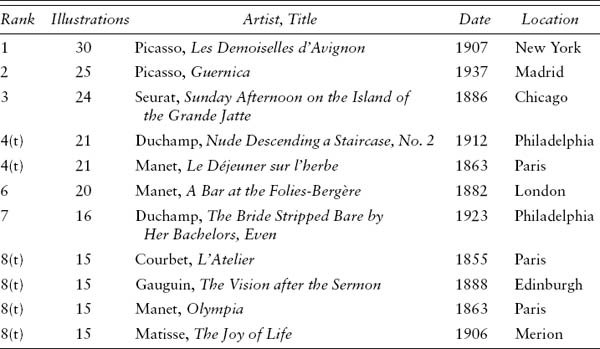

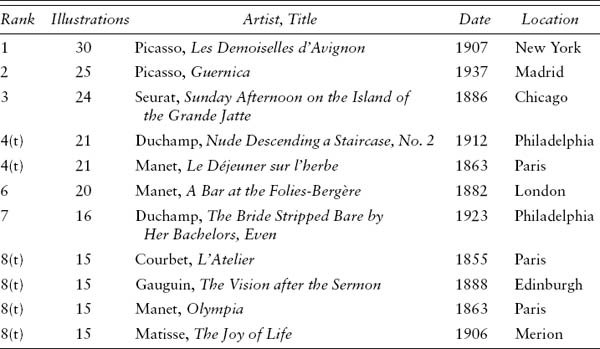

This analysis of artists’ life cycles has implications for many significant issues in the history of modern art. Some of these have long been of interest to art historians, but others have actually not been noticed by historians. One of the latter is posed by tables 4.1 and 4.2. These list the individual paintings, by artists who lived and worked in France during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, that are most often reproduced in the 33 American and 31 French textbooks surveyed earlier in chapter 2. Both lists rank the top 10 paintings by number of illustrations; because of ties, this yields a total of 11 paintings in table 4.1, and 12 in table 4.2. The paintings listed in tables 4.1 and 4.2 are all classic works of modern art, their images immediately familiar to students of art. Their importance is the subject of little disagreement among scholars of different nations; eight paintings appear in both tables, and no painting ranked among the top five works in either table fails to appear in the other table. It might therefore be concluded that these lists hold no surprises.

Yet tables 4.1 and 4.2 do hold a major surprise. Some of the very greatest painters of this era, including Cézanne, Degas, Pissarro, and Renoir, fail to appear on either list. At the same time, a number of artists, including not only Picasso and Manet, but also Courbet and Duchamp, have multiple entries on the lists. The puzzle is considerable: Why does Cézanne, one of the very most important painters of the modern era, have no painting among those works identified by a consensus of art scholars as the most important, while Courbet and Duchamp, who are not generally considered nearly as important, both have more than one painting ranked among the most important individual works by both American and French scholars?

TABLE 4.1

Ranking of Paintings by French Artists, by Total Illustrations in American Textbooks

Source: Galenson, “Quantifying Artistic Success,” table 3, p. 8.

A hint as to the resolution of this puzzle is suggested by an examination of tables 4.1 and 4.2 in light of the two categories of artist defined by this study. The two tables include a total of 15 paintings. Of these, all but one were executed by conceptual artists. Monet’s Impression, Sunrise, which ranks seventh in table 4.2, is the only painting in either table produced by an experimental artist. The other 14 paintings, which fill 22 of the 23 places in the two tables, were all made by conceptual painters.

The puzzle is resolved by combining this recognition of the conceptual origin of nearly all these modern masterpieces with an understanding of the institutions of the art market in France during this period. Throughout the first three-quarters of the nineteenth century, French artists understood that the government’s official Salon was the sole means of having their work presented to the public in a setting that would assure critics and collectors of its worth: the Salon had an effective monopoly of the legitimate presentation of new art to the public. Yet the enormous size of these annual or biennial exhibitions, which typically had thousands of entries, produced a considerable danger that even if an artist succeeded in having his work selected by the Salon’s jury, it would be ignored because it was hung in a bad location. Historian George Heard Hamilton observed that “one way for an artist to avoid such a calamity was to paint a picture so large it could not possibly be overlooked. Such huge ‘machines,’ by reason of their size alone, attracted critical and popular attention quite out of proportion to their merit.”2

TABLE 4.2

Ranking of Paintings by French Artists, by Total Illustrations in French Textbooks

Source: Galenson, “Measuring Masters and Masterpieces,” table 3, p. 54.

Conceptual painters had a decisive advantage in producing large and complex works that, in Bazille’s words, “demand very conscientious preparatory studies.” Six of the paintings in tables 4.1 and 4.2—three each by Courbet and Manet—were initially submitted to the official Salon. Producing these large works was a regular part of these artists’ annual routines. So, for example, late in 1854, Courbet wrote to a friend that “I have managed to sketch my painting, and at the moment it is entirely transferred to the canvas, which is twenty feet wide and twelve feet high. This will be the most surprising painting imaginable: there are thirty life-size figures.” He noted, “I have two and a half months to carry it out . . . so that all told I have two days for each figure.”3 This schedule was dictated by the deadline for submitting works to the Salon of 1855, and Courbet met it. His confidence that he would be able to do this resulted from his knowledge that once he had made a full compositional drawing of a painting, the execution of the work would follow without unforeseen difficulties: “Works of art are conceived all at once, and the composition, once it is well established and firmly outlined in the mind in all its details, casts it into its frame on paper or on canvas in such a way that there is no need to modify it in the course of execution.”4

The importance of the official Salon declined considerably during the final quarter of the nineteenth century, but the importance of great individual works nonetheless persisted. In large part, this was because for the remainder of the century other large-scale group exhibitions continued to be the necessary venues for the legitimate presentation of new art to the public.5 Thus many painters, including Matisse and Seurat, persisted in the practice of regularly planning large, ambitious paintings for display in group exhibitions. But even after exhibiting at group shows ceased to be necessary, the large, complex masterwork continued to be the chief token of success in Paris’s advanced art world. Although Picasso was the first major modern artist who established himself without participating in group exhibitions, his greatest single work was nonetheless prompted by the tradition of the Salon masterwork. Early in his Paris career, the ambitious young Picasso recognized Matisse as his rival for the informal leadership of the advanced art world, and he envied the attention Matisse gained from showing his Joy of Life (listed in table 4.1) at the 1906 Salon des Indépendants. Challenged by Matisse’s painting’s “success within the terms of traditional Salon canvases,” Picasso methodically and deliberately set out to produce a “large salon-type painting” that would be recognized as a masterpiece by the artists, critics, and collectors who made up Paris’s advanced art world.6 He succeeded in producing the work that many art historians consider the most important painting of the twentieth century, as the Demoiselles d’Avignon dominates both tables 4.1 and 4.2.

The importance of group exhibitions in the French art world of the nineteenth century thus profoundly influenced artists’ practices. Ambitious painters devoted disproportionate effort to making large and complicated individual paintings as a means of establishing and advancing their reputations. And this type of competition afforded a great advantage to conceptual artists, whose practices better enabled them to plan and carry out large and complex individual paintings. Ambitious experimental painters struggled under the burden of trying to do this. Recognizing this leads to another important implication of the present analysis for our understanding of the history of modern art.

I shan’t send anything more to the jury. It is far too

ridiculous . . . to be exposed to these administrative

whims. . . . What I say here, a dozen young people of

talent think along with me. We have therefore decided

to rent each year a large studio where we’ll exhibit

as many of our works as we wish.

Frédéric Bazille, 18677

The Impressionists have killed many things, among

others the exhibition picture and the exhibition picture

system. The directness of their method and the clearness

of their thought enabled them to say what they had to

say on a small surface. . . . They introduced the group

system into exhibition rooms, showing that one picture

by an artist, though a detachable unit, also forms a

link in a chain of thought and intention that runs

through his whole oeuvre.

Walter Sickert, 19108

The Impressionists’ decision to secede from the official Salon and hold their own independent group exhibitions is among the most celebrated episodes in the history of modern art. Yet in spite of the vast amount of scholarly attention that has been devoted to describing these exhibitions and their consequences, one basic question that has been surprisingly neglected is why it was Monet and a few of his friends, rather than any others among the great number of other neglected painters in mid-nineteenth-century Paris, who actually undertook to devise an institutional alternative to the Salon. Understanding the differing working methods of conceptual and experimental artists provides a key element of the answer to this question.

A major motivation for the Impressionists’ desire to hold their own exhibitions appears to have been their recognition that, as experimental painters, their procedures were not well suited to fighting for acceptance on the Salon’s terms. The two friends Bazille and Monet first formulated the idea of holding independent group exhibitions in 1867. For Monet, this came at a point when he had failed at two time-consuming attempts to produce major individual paintings for the Salon. During 1865 and early 1866, he had spent months working on a large painting, 15 by 20 feet, that would be his Déjeuner sur l’herbe. He made a number of figure drawings for the painting, a large charcoal sketch of the composition, and an oil sketch of the whole composition before beginning the final canvas. Unable to complete the painting on time, Monet missed the submission deadline for the 1866 Salon. He ultimately abandoned the enormous unfinished work, which he later described as “incomplete and mutilated.”9 Later in 1866, he set out to make a smaller but still ambitious painting, 8 by 7 feet in size, titled Women in the Garden. This painting, made without preparatory sketches or studies, was rejected by the Salon jury in 1867.10 These two unsatisfactory attempts appear to have convinced Monet that it was a mistake for him to try to follow his friends Courbet and Manet in producing large individual paintings for the Salon. Bazille’s account of the two friends’ original plans for a group exhibition in 1867 described a show “where we’ll exhibit as many of our works as we wish,” a format more appropriate for an experimental approach that naturally produced groups of smaller paintings rather than impressive individual works.

Manet’s persistent refusal to stop exhibiting at the official Salon and join his friends at their independent shows is similarly illuminated by the fact that unlike Monet, Degas, Pissarro, Renoir, and Sisley, Manet was a conceptual artist. Despite a number of snubs by the Salon’s jury, including the rejection of his Déjeuner sur l’herbe in 1863, Manet held to the position that “the Salon is the true field of battle—it is there that one must measure oneself.”11 Although his style often created conflict with the Salon’s jury, Manet’s conceptual approach allowed him regularly to create the large and complex individual paintings that were well suited to compete for attention at the great official exhibitions. In contrast, Monet and his Impressionist colleagues appear to have realized that they could create large paintings for the Salon only by sacrificing quality in their art.

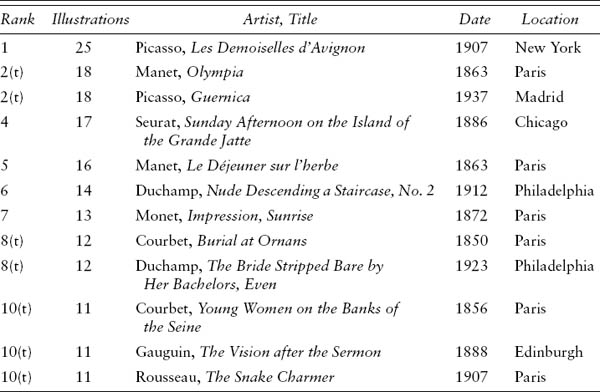

Table 4.3 demonstrates the extent to which the Impressionists adapted their independent exhibitions to their experimental approach, listing the number of paintings by the leading members of the group included in each of the eight shows. Monet exhibited 9 paintings at the first show and at least twice that number in each of the four later shows in which he participated. Five artists—Degas, Monet, Pissarro, Renoir, and Sisley—each displayed 20 or more works in at least one of the exhibitions, and three of them did so more than once. These large numbers of paintings, which were much greater than the artists could ever have hoped to enter in the official Salon, could almost serve effectively to give the leaders of the movement one-man shows in the midst of their group exhibitions. In light of the analysis presented here, the Impressionists’ group exhibitions can thus be seen as the response of a group of ambitious young experimental painters to an official institution that they recognized to be better suited in format to conceptual artists.

TABLE 4.3

Number of Entries by Selected Artists at Impressionist Exhibitions

Source: Moffett, New Painting.

A work of art is a vehicle for the transmission of

information concerning the mental, or physical,

activity of an artist.

Richard Hamilton, 197112

An intriguing phenomenon in modern art is the existence of a number of extremely important individual works that were made by artists who are not themselves considered important. These works, which are often featured more prominently in the canon of modern art than any individual works by much more celebrated artists, dominate our perceptions of the careers of the artists who produced them. Although art historians are aware of each of these masterless masterpieces, they have not recognized a connection among them, for they treat them as isolated anomalies. The analysis presented here implies that this is not the case. Rather, these major works by minor artists appear to form a class, comprising dramatic examples of conceptual innovations, often made quickly and suddenly by very young artists.

Paul Sérusier (1863–1927) is known today as a minor Symbolist painter. A study of 31 French textbooks of modern art published since 1963 confirms Sérusier’s minor status, as table 4.4 shows that these books contain a total of just 14 illustrations of his work, or less than one-fifth as many as they contain of the work of some great masters of the late nineteenth century also listed in the table. Remarkably, however, 11 of the 14 illustrations of Sérusier’s work are of a single painting, and table 4.5 shows that this places that painting above any single work by Cézanne, van Gogh, Renoir, or Degas in frequency of illustration in the French books. How is this possible?

TABLE 4.4

Ranking of Selected Nineteenth-Century Painters by Total Illustrations in 31 French Textbooks

Artist |

Illustrations |

Cézanne |

120 |

van Gogh |

101 |

Renoir |

75 |

Degas |

74 |

Sérusier |

14 |

Source: Galenson, “Measuring Masters and Masterpieces,”pp. 53, 77.

Late in the summer of 1888, in the Breton artists’ colony of Pont Aven, the 25-year-old art student Paul Sérusier introduced himself to Paul Gauguin, who was then generally recognized as the leading Symbolist painter, and spent a single morning painting with the master at the edge of a small forest. Gauguin told Sérusier not to hesitate to use pure colors to express the intensity of his feelings for the landscape: “ ‘How do you see this tree,’ Gauguin had said. . . . ‘Is it really green? Use green then, the most beautiful green on your palette. And that shadow, rather blue? Don’t be afraid to paint it as blue as possible.’ ” Upon Sérusier’s return to Paris, the small painting of the Bois d’Amour that he had made under Gauguin’s supervision electrified a group of his fellow students, including Pierre Bonnard, Maurice Denis, and Édouard Vuillard. The students renamed Sérusier’s little painting The Talisman in recognition of its inspiration for their art, gave themselves the collective name of the Nabis, from the Hebrew word for “prophet,” and began to meet regularly to discuss Gauguin’s Symbolist ideas as transmitted by Sérusier. The Nabis developed Gauguin’s advice on expressive imagery into the doctrine that the artist’s impressions could best be expressed by exaggeration, with distortions of line and simplification of color serving the painter just as exaggerations of language served the poet in creating metaphors. Thus the work of just a few hours, embodied in a painting less than 90 square inches in size, gave rise to one of the leading movements of advanced art of the 1890s.13 This was possible because Gauguin’s lesson was not visual, but conceptual. As Denis later recorded in a eulogy for Gauguin, Sérusier’s painting provided the group of young painters with a liberating new idea, for it “introduced to us for the first time, in a paradoxical and unforgettable form, the fertile concept of the ‘plane surface covered with colors assembled in a certain order.’ Thus we learned that every work of art was a transposition, a caricature, the passionate equivalent of a sensation received.”14

TABLE 4.5

Most Frequently Illustrated Paintings by Artists in table 4.4

Artist, Painting |

Illustrations |

Sérusier, Le Bois d’Amour (The Talisman), 1888 |

11 |

Cézanne, The Large Bathers, 1905 |

9 |

Renoir, Moulin de la Galette, 1876 |

9 |

van Gogh, Père Tanguy, 1887 |

7 |

Degas, L’Absinthe, 1876 |

5 |

Source: Galenson, “Measuring Masters and Masterpieces,” pp. 54, 77.

The Talisman was thus credited with a causal role in Denis’s early and far-reaching statement of formalist art theory declaring the visual autonomy of the work of art, and which would eventually be used to justify the abandonment of representation in painting.15 The fame of The Talisman and the lack of fame of its maker thus forcefully illustrate a consequence of the nature of conceptual innovation: The Talisman was important because it communicated Gauguin’s revolutionary conceptual aesthetic to Denis and the other Nabis, but Sérusier’s unimportance resulted from the fact that he was little more than the scribe who recorded it.

Meret Oppenheim (1913–85) was born in Germany, raised in Switzerland, and went to Paris to study art at the age of 19. She worked informally under the guidance of a number of Surrealist artists she met there, including the sculptor Alberto Giacometti. Oppenheim painted and sculpted forms that were implied by ideas: “Every idea is born with its form. I carry out ideas the way they enter my head. Where inspiration comes from is anybody’s guess but it comes with its form; it comes dressed, like Athena who sprang from the head of Zeus in helmet and breastplate.”16

To support herself Oppenheim began designing jewelry, using the same conceptual approach as in her other artistic activities. One day in 1936 she was sitting in the Café de Flore with her friends Dora Maar and Pablo Picasso when Picasso became intrigued with a bracelet Oppenheim had made by covering metal tubing with fur. Picasso mused that one could cover anything with fur, and Oppenheim replied, “Even this cup and saucer.” Shortly thereafter, when André Breton invited her to contribute to a Surrealist exhibition, Oppenheim bought a large cup and saucer with a spoon, and covered the three objects with the fur of a Chinese gazelle. Breton named the work Déjeuner en fourrure (Luncheon in Fur).17

TABLE 4.6

Ranking of Selected Twentieth-Century Sculptors by Total Illustrations in 25 Textbooks

Sculptor |

Illustrations |

Alberto Giacometti |

39 |

Claes Oldenburg |

36 |

Henry Moore |

34 |

Alexander Calder |

32 |

Meret Oppenheim |

7 |

Source: Adams, History of Western Art; Arnason and Wheeler, History of Modern Art; Bell, Modern Art; Bocola, Art of Modernism; Britsch and Britsch, Arts in Western Culture; Britt, Modern Art; Cornell, Art; de la Croix, Tansey, and Kirkpatrick, Gardner’s Art through the Ages; Dempsey, Art in the Modern Era; Feldman, Thinking about Art; Fleming, Arts and Ideas; Freeman, Art; Gilbert, Living with Art; Hartt, History of Painting, Sculpture, Architecture; Honour and Fleming, Visual Arts; Hughes, Shock of the New; Hunter and Jacobus, Modern Art; Kemp, Oxford History of Western Art; Sporre, Arts; Sproccati, Guide to Art; Stokstad and Grayson, Art History; Strickland and Boswell, Annotated Mona Lisa; Varnedoe, Fine Disregard; Wilkins, Schultz, and Linduff, Art Past, Art Present; Wood Cole, and Gealt, Art of the Western World.

Meret Oppenheim continued to make art past the age of 70, but she never became a famous artist. Table 4.6 shows that her work receives a total of only seven illustrations in 25 textbooks of art history, placing her far below some important sculptors of the twentieth century. Yet because all seven illustrations are of Déjeuner en fourrure, table 4.7 shows that it ranks ahead of any single sculpture by such modern masters as Alexander Calder, Henry Moore, Claes Oldenburg, and Oppenheim’s friend Alberto Giacometti in frequency of reproduction in the 25 texts. Thus an object made by a 23-year-old artist as a result of a chance conversation in a Paris café became an emblem of Surrealism, and one of the most famous sculptures of the twentieth century.

The contemporary artist Jenny Holzer emphasized the conceptual nature of Déjeuner en fourrure: “Although it is wonderful to see, you can carry it in your mind without actually looking at it.”18 Oppenheim’s sculpture was a striking embodiment of two central aspects of Surrealist art, for it was an object with symbolic meaning, lacking in aesthetic quality and craftsmanship, and its symbolism placed it squarely in a line of Surrealist works that represented sexual freedom.19 Thus whereas Holzer recognized that its “nonart materials are appropriate” for the concerns of Déjeuner, Robert Hughes described the work as “the most intense and abrupt image of lesbian sex in the history of art.”20 The fame of the work and the lack of fame of its young maker both stem from the fact that Déjeuner en fourrure dramatically and fully embodied an innovative idea.

TABLE 4.7

Most Frequently Illustrated Sculptures by Sculptors in Table 4.6

Sculptor, Sculpture |

Illustrations |

Oppenheim, Le Déjeuner en fourrure, 1936 |

7 |

Calder, Lobster Trap and Fish Tail, 1939 |

5 |

Moore, Reclining Figure, 1939 |

5 |

Giacometti, Man Pointing, 1947 |

4 |

Giacometti, City Square, 1948 |

4 |

Oldenburg, Clothespin, 1976 |

4 |

Source: See table 4.6.

In London in the early 1950s, Richard Hamilton (1922–) was a member of the Independent Group, a number of young artists who met informally to discuss their interest in mass culture. They shared a fascination with American advertising and graphic design, and wanted to create an art that would have the same kind of popular appeal. They also wanted this art to bridge the growing gap between the humanities and modern science and technology.21 In 1956 the Independent Group organized a joint exhibition, “This Is Tomorrow,” which was designed to examine the interrelationships between art and architecture. Hamilton agreed to create an image that could be used as a poster for the show. The result was a small collage titled Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?

Hamilton began the work by making a list of categories that included Man, Woman, Food, Newspapers, Cinema, TV, Telephone, Comics, and Cars. Hamilton, his wife, and another artist then searched through piles of magazines, many of which had been brought back from the United States by a fellow Independent Group member, cutting out illustrations of objects that could represent the categories on Hamilton’s list. Hamilton then selected an image for each category, according to how they would fit into the fictitious living space he was constructing. Among its images, Just what is it? contains a male bodybuilder, a female pinup, a comic book cover, an insignia for Ford automobiles, and even the word “Pop” on a large Tootsie pop held up by the bodybuilder. The work’s title was itself the caption from a discarded photograph.22

TABLE 4.8

Ranking of Selected Artists of 1950s and 1960s by Total Illustrations in 36 Textbooks

Artist |

Illustrations |

Warhol |

68 |

Rauschenberg |

67 |

Johns |

63 |

Lichtenstein |

54 |

Hamilton |

26 |

Source: Galenson, “One-Hit Wonders,” table 11.

Richard Hamilton has had a long career as a painter, conceptual artist, and art teacher; he has been honored by no less than three retrospective exhibitions at London’s Tate Gallery; and he is considered a leading figure in British Pop Art.23 Yet he has never achieved nearly the same level of fame or critical attention as a number of American artists of his cohort. Thus table 4.8 shows that in a survey of 36 textbooks Hamilton’s work was illustrated less than half as often as that of the leading American artists of the late 1950s and the ’60s. Yet, remarkably, table 4.9 shows that 21 of the 26 illustrations of Hamilton’s work were of Just what is it?, placing it far ahead of any individual work by Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg, or Andy Warhol in frequency of illustration in the 36 textbooks.

Just what is it? has been described as “an icon of early Pop.24 In 1956, several years before Warhol or Lichtenstein had begun to reproduce photographic images or to mimic comic books, a 34-year-old English artist had combined these techniques in a single synthetic work, making it “an extraordinary prophecy of the iconography of Pop.”25 And appropriately for a prototype for a movement that would celebrate commercial culture, Just what is it? was not only made from advertisements, but was itself made to be an advertisement. Just what is it? differed considerably not only from the work Hamilton did before it, but also from that he would do later, for it was an isolated conceptual innovation. The rise of Pop Art did not make Hamilton a famous artist, but it did give Just what is it? a place in the canon of contemporary art for its role as a forerunner of the dominant art movement of the early 1960s.

These three instances of masterpieces without masters are not alone in the history of modern art, and the phenomenon is likely to become more common in the current era of conceptual art. A notable recent example was identified by a survey of 40 textbooks of art history, which found that two works were tied for the distinction of being reproduced more often than any other others made by American artists during the 1980s.26 One of these was Tilted Arc, executed in 1981 by the sculptor Richard Serra, who is widely recognized as one of the most important living American artists. The other was the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, dedicated in 1982, which had been designed by Maya Lin at the age of 21, during her senior year in college.

TABLE 4.9

Most Frequently Illustrated Works by Artists in Table 4.8

Artist, Work |

Illustrations |

Hamilton, Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? 1956 |

21 |

Rauschenberg, Monogram, 1959 |

13 |

Lichtenstein, Whaam! 1963 |

12 |

Warhol, Marilyn Diptych, 1962 |

11 |

Johns, Flag, 1955 |

10 |

Source: Galenson, “One-Hit Wonders,” table 12.

Lin originally made her design for the memorial as an assignment in an architecture seminar she took at Yale. She wanted to see the site, so she and a few friends traveled to Washington, D.C. She later recalled that “it was at the site that the idea for the design took shape”: “I had a simple impulse to cut into the earth. I imagined taking a knife and cutting into the earth, opening it up, an initial violence and pain that in time would heal.”27

Lin’s plan was to have two long walls of polished black granite, arranged in a V shape, placed in the ground to form an embankment. One of the walls was to point to the Lincoln Memorial, the other to the Washington Monument: “I wanted to create a unity between the country’s past and present.” Lin soon realized that the strength of her design lay in its simplicity: “On our return to Yale, I quickly sketched the idea up, and it almost seemed too simple, too little. I toyed with adding some large flat slabs that would appear to lead into the memorial, but they didn’t belong. The image was so simple that anything added to it began to detract from it.”28

Lin’s design was a radical departure from earlier memorial architecture, for the memorial was influenced much more by Minimalist sculpture than by traditional memorials. Her use of abstract forms initially shocked veterans and others who had expected a realistic portrayal of soldiers in combat. Yet when the memorial was completed, it quickly came to be recognized as a moving tribute to the soldiers who had died in Vietnam. Today it not only is the most visited memorial in the capital, but is widely considered to have established a new level of excellence for memorial architecture. So, for example, when the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation held a competition for a memorial to the victims of the 2001 attack on the World Trade Center, Maya Lin was appointed to the five-member jury. When the eight final designs were presented to the public, the architecture critic for the New Yorker remarked that although all of these were intelligent, they received a lukewarm reaction from critics and the public because “in the post-Vietnam-memorial age, we may have come to expect too much of a memorial.” The problem was that Lin had set a new standard: “Lin’s Vietnam memorial set the bar very high.”29

In the two decades since she designed the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Lin has pursued a career as an architect and sculptor. A recent profile observed, “Now a beneficiary of a stream of commissions, this still-young master is riding her good fortune, turning out institutional and private projects while also making the individual sculptures to which she attaches such importance.”30 Yet whereas the Vietnam Veterans Memorial was illustrated in 16 of the 40 textbooks examined for the study cited here, no other work by Lin was reproduced in even a single book. Thus from the vantage point of art scholars, Lin’s contribution consists of a single work, which one scholar described as “one of the most compelling monuments in the United States.”31 That a 21-year-old artist could conceive an innovation that would be fully expressed in a single enormously successful project, and that would be followed by no others deemed significant by art scholars, is a phenomenon unique to conceptual art, and in this Lin’s career resembles those of Sérusier, Oppenheim, and Hamilton. Although their common features have gone unnoticed by art historians, their masterpieces were all achieved quickly, as the result of sudden insights, by young artists. All are prime examples of conceptual innovations.

The young master is a new phenomenon in

American art.

Harold Rosenberg, 197032

The dramatic innovations that many conceptual artists have made early in their careers have often allowed them to gain attention at much younger ages than their experimental counterparts. There were instances of this in the nineteenth century, as Manet became the focal point for controversy in Paris’s advanced art world at the age of 31, when his Déjeuner sur l’herbe was shown at the Salon des Refusés in 1863, and Georges Seurat similarly gained widespread attention at the age of 27, when his Sunday Afternoon on the Island of the Grande Jatte was exhibited in the final Impressionist exhibition in 1886. But this would become much more common in the twentieth century, as critics, dealers, and collectors became more aware of the fact that the paintings that introduced radical innovations often rose sharply in value within as little as a decade after their appearance.

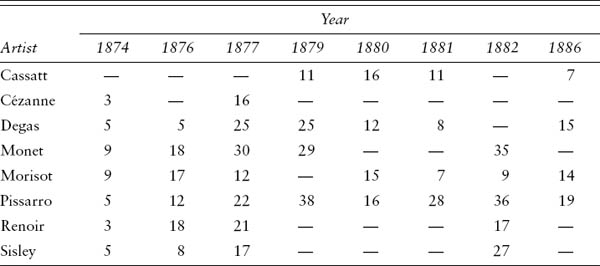

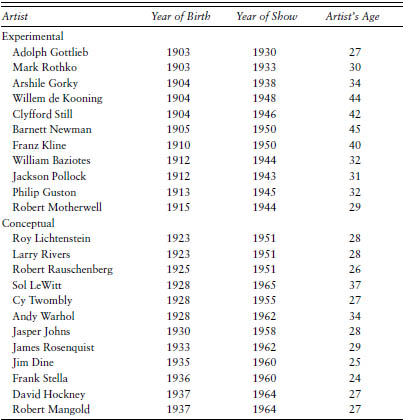

One consequence of this recognition was that many art dealers became more willing to give exhibitions to young and unproven painters. This can be seen in a shift that occurred in New York during the late 1950s and early ’60s, as the experimental Abstract Expressionists gave way to the conceptual artists of the next generation. Table 4.10 shows that the median age at which 11 leading Abstract Expressionist had their first oneman shows in New York was 34, but that this age fell to just 27.5 for a dozen leading members of the next generation. Only two of the 11 Abstract Expressionists had their first shows before the age of 30, compared with 10 of the 12 artists of the following cohort. Three major Abstract Expressionists—de Kooning, Still, and Newman—did not debut in New York until after age 40, whereas all the leaders of the next generation had their first shows in the city well before they reached 40.

When Frank Stella was given a retrospective exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1970 at the age of 33, the critic Harold Rosenberg, who was a prominent supporter of the Abstract Expressionists, was indignant. He observed acidly that “the indispensable qualification of the creators of American art has been longevity.” Nor was this unique to American art, for Rosenberg declared, “It is inconceivable that Cézanne, Matisse, or Miró could have qualified for a retrospective in a leading museum after their first dozen years of painting; certainly Gorky, Hofmann, Pollock, and de Kooning did not.” Rosenberg argued that major artistic contributions required long gestation periods: “Self-discovery has been the life principle of avant-garde art . . . and no project can, of course, be more time-consuming than self-discovery. Every step is bound to be tentative; indeed, it is hard to see how self-discovery can take less than the individual’s entire lifetime.” In closing his scathing review of Stella’s exhibition, Rosenberg protested, “For a coherent body of significant paintings to spring directly out of an artist’s early thoughts, a new intellectual order had to be instituted in American art.”33 Although Rosenberg deplored this situation, his analysis of it was correct. As the experimental methods of the Abstract Expressionists were replaced by a variety of conceptual approaches, the artistic value of experience declined sharply, and the new intellectual order in advanced art gave rise to a new career pattern in which artists would routinely gain fame, and often fortune, at an early age.34

TABLE 4.10

Ages of American Artists at the Time of Their First One-Man New York Gallery Exhibitions

Source: Galenson, Painting outside the Lines, appendix C.

We worked for years to get rid of all that.

Mark Rothko, on Jasper Johns’s first one-man

show, 195835

I’m neither a teacher nor an author of manifestos. I don’t

think along the same lines as the Abstract Expressionists,

who took those sorts of things all too seriously.

Jasper Johns, 196936

The difference in the timing of the careers of experimental and conceptual artists has been capable of causing considerable resentment, as experimental artists who have spent years struggling, often in poverty and obscurity, to make contributions to art have been jealous of younger conceptual artists’ quick commercial success. Yet conflicts between the two types of artist have often arisen from a deeper source than mere jealousy. For although it need not always be manifest, there is a powerful potential for hostility and distrust between artists of the two groups as a result of differences in their philosophies of art, and associated differences in their practices and products.

There is a persistent tendency for conceptual artists to regard experimental painters as mere artisans, lacking in intelligence. The conceptual innovator Marcel Duchamp complained that modern art had been addressed not to the mind, but to the eye: “I was interested in ideas—not merely in visual products. I wanted to put painting once again at the service of the mind.”37 Duchamp explained that his art was a reaction against what he considered an excessive emphasis on appearance: “In French there is an old expression, la patte, meaning the artist’s touch, his personal style, his ‘paw.’ I wanted to get away from la patte and all that retinal painting.” The one modern artist he exempted from his criticism was his fellow conceptual artist Seurat: “He didn’t let his hand interfere with his mind.”38 Duchamp had little regard, however, for those he called retinal painters: “ ‘Bête comme un peintre’ was the saying in France all through the last half of the nineteenth century, and it was true, too. The kind of painter who just puts down what he sees is stupid.”39 Duchamp’s disdain for “la patte and all that retinal painting” was echoed by a number of conceptual artists during the 1960s. So, for example, Frank Stella explained, “I do think that a good pictorial idea is worth more than a lot of manual dexterity.”40

Conversely, experimental painters often consider conceptual artists to be intellectual tricksters, lacking in artistic ability and integrity. So, for example, in 1887 when his former protégé Paul Gauguin began to gain recognition for his conceptual contributions to Symbolism, Camille Pissarro could only conclude that Gauguin was not seriously committed to art: “At bottom his character is anti-artistic, he is a maker of odds and ends.” With bitter irony, Pissarro wrote to his son that Gauguin had gained “a group of young disciples, who hung on the words of the master. . . . At any rate it must be admitted that he has finally acquired great influence. This comes of course from years of hard and meritorious work—as a sectarian!” Several years later, when a journalist praised Gauguin for his innovations, Pissarro again complained of the younger artist’s insincerity: “When one does not lack talent and is young into the bargain how wrong it is to give oneself over to impostures! How empty of conviction are this representation, this décor, this painting!” In what may have been the last meeting between the two former friends, Pissarro attended an exhibition of Gauguin’s paintings at Durand-Ruel’s gallery on the occasion of the younger artist’s return from his first stay in Tahiti in 1893. Pissarro found the work to be dishonest and told his former pupil as much:

I saw Gauguin; he told me his theories about art and assured me that the young would find salvation by replenishing themselves at remote and savage sources. I told him that this art did not belong to him, that he was a civilized man and hence it was his function to show us harmonious things. We parted, each unconvinced. Gauguin is certainly not without talent, but how difficult it is for him to find his own way! He is always poaching on someone’s ground; now he is pillaging the savages of Oceania.

Pissarro noted that his Impressionist friends agreed: “Monet and Renoir find all this simply bad.”41 Gauguin’s remarks to Pissarro at the gallery were prophetic, for his work would in fact influence many of the leading painters of the next generation, including Picasso and Matisse. Yet although these later conceptual artists could find inspiration in Gauguin’s Symbolism and his imaginative use of primitive art, Pissarro and his fellow Impressionists, whose lives were devoted to the painstaking experimental development of a visual art, could see in his work only insincerity, opportunism, and plagiarism.42

The Impressionists’ reaction to their conceptual successors was later echoed by the Abstract Expressionists’ rejection of the conceptual artists who followed them in New York. Thus when Robert Motherwell first saw Frank Stella’s early paintings of black stripes, he remarked, “It’s very interesting, but it’s not painting.”43 And in 1962, Motherwell explained that the new art was not in the true line of descent of fine art: “Immediately contemporary painting seems to be developing in the direction of pop art. Coca-Cola! There will be a tremendous excitement about what, in effect, will be the ‘folk art’ of industrial civilization and thus different from preceding art: i.e., the reference will not be to high art, but to certain effects of industrial society. The pop artists couldn’t care less about Picasso or Rembrandt.” With irony, Motherwell added, “I am all in favor of pop art. . . . I’m glad to see young painters enjoying themselves.”44

Admirers of conceptual art typically praise its brilliance, clarity, and structure; detractors often criticize it as cold, calculated, and superficial. Experimental artists are often praised for their touch, and for the depth of expression that comes with experience; they are often criticized for their lack of discipline, and for their mysticism.

During the era of modern art, experimental painters have been recognized as leaders during relatively brief periods, while conceptual artists have dominated for longer intervals. Thus the experimental art of Impressionism was the central form of advanced modern art for little more than a decade, during the 1870s, then was quickly succeeded by a variety of conceptual approaches, including Neo-Impressionism and Symbolism, which were in turn followed by the conceptual approaches of Fauvism and Cubism. Most of the major movements that followed Cubism were conceptual, though Surrealism included both conceptual and experimental painters among its diverse followers. Some of the experimental Surrealists were an early influence on Abstract Expressionism, which became the dominant movement in the advanced painting of the early 1950s. Yet this experimental art was quickly displaced by a variety of conceptual approaches in the late 1950s and beyond, as Pop, Minimalism, and a number of other innovations captured the attention of the art world. Although it does not appear that there is any necessary pattern or cycle in this alternation between approaches, several factors do appear to exert systematic influences. One is that the perceived excesses of either approach can create an interest in reacting against it, not only on the part of young artists, but also among critics, dealers, and others in the art world who can encourage and help these young artists. Thus, for example, a common theme in the recollections of many of the conceptual innovators of the 1960s is that when they were beginning their careers they found the art and attitudes of the Abstract Expressionists oppressive. These younger artists used humor and irony to combat what they considered the pretentious emotional and philosophical claims of the Abstract Expressionists, and they substituted impersonal execution for what they perceived to be the excessively personal styles of their predecessors.

Reactions against a dominant approach can of course occur in either direction, as experimental artists can equally seek to overthrow dominant conceptual paradigms. Today’s art world, with its frequent complaints against the current extremes of conceptual art, may be ripe for an experimental revolution. Yet considering this possibility points to a different influence that may be a key factor in understanding why the predominantly conceptual phases of the modern era have been longer than the experimental ones. This is simply that because radical conceptual innovations can be made much more quickly than experimental ones, conceptual artists will tend to have an advantage in any situation in which there is a strong demand for innovation. Arthur Danto recently observed, “In many ways, the Paris art world of the 1880s was like the New York art world of the 1980s—competitive, aggressive, swept by the demand that artists come up with something new or perish.”45 The artists who thrive in these situations tend to be the young geniuses who can innovate deliberately and systematically, before giving way to the next cohort of young geniuses; thus the young Seurat emerged as a leader in Paris’s advanced art world in the 1880s, just as young conceptual artists like Julian Schnabel and Jean-Michel Basquiat emerged in the New York art world of the 1980s. In contrast, experimental painters were largely eclipsed in both these eras, perhaps overwhelmed by the urgent demand quickly to produce dramatic new results. So, for example, one of the greatest experimental painters of the nineteenth century largely retreated from Paris during the contentious 1880s, as after 1882 Cézanne lived in relative seclusion in Provence, seeking not only the inspiration of the southern landscape he loved, but also the peace and solitude he felt he needed for the slow and painstaking development of his art. His letters refer to his mistrust of the conceptual debates that were raging in Paris’s cafes, as when he explained in 1889, “I had resolved to work in silence until the day when I should feel myself able to defend theoretically the result of my attempts.”46 We may not yet know the identity of today’s important experimental artists if they are similarly developing their art out of the limelight, away from New York and the other hectic central battlegrounds of the art world where artists feel that “there is this pressure now to be surer, quicker, more confident.”47

When the early conceptual innovations of a young artist are recognized quickly, the reassurance—and income—they provide the artist can be of great value in affording him the freedom to experiment further. It was in recognition of this that Picasso described the critical success of his early blue and rose periods as “screens that shielded me. . . . It was from within the shelter of my success that I could do what I liked, anything I liked.”48 His subsequent radical departure into Cubism may have been a product of this shelter. Yet although they are more likely to gain early acclaim, the greatest danger to conceptual artists may be the dry spells that occur when they run out of ideas.49 Although many experimental painters suffer from chronic uncertainty about the quality of their work, they appear to be less likely to stop working altogether in crises of confidence, for their trial-and-error approach usually presents many possible avenues for further research. And experimental artists can draw some comfort from the realization that their work is more likely to improve over time than that of their aging conceptual counterparts.

It was for me the greatest revelation. I understood

instantly the mechanics of the new painting.

Raoul Dufy, on seeing Matisse’s Luxe,

calme, et volupté, 190550

Just as conceptual innovations can often be created immediately, as the expression of new ideas, so can they often be communicated immediately. Experimental art, with more complex methods and imprecise goals, usually requires direct contact between teacher and student for instruction that leads to real understanding and mastery, but conceptual art, with its less complex methods and clearer goals, can often be transmitted without direct contact between artists, merely through seeing reproductions of works of art, or even simply reading written texts.

This difference in the ease and speed of transmission of the two types of art has had important implications for the changing geographic locus of the production of advanced art during the modern era. Artists who wanted to learn the techniques and philosophy of Impressionism had to spend time talking and working with members of the core group. Pissarro was the most welcoming of them, and Cézanne and Gauguin both spent time working in Pontoise under his guidance during the 1870s and ’80s. In addition, Pissarro appears to have spent time explaining Impressionism to van Gogh in Paris during 1886–87, and to Matisse in the late 1890s.51 Mary Cassatt similarly served an informal apprenticeship with Degas.52 In all these cases, the instruction occurred gradually, for studying Impressionism involved not only learning a variety of techniques, but also understanding a diffuse set of visual goals that were more easily demonstrated than expressed verbally. Artists who wanted to use the methods of Impressionism, or to learn them so they could make them a foundation for new departures, simply had to go to Paris.

Even in the late nineteenth century, the communication of conceptual innovations apparently began to be made more quickly, with considerably less contact. A celebrated instance was discussed earlier in this chapter. Thus Paul Sérusier spent just a few hours working with Paul Gauguin, and during that time produced a painting that inspired not only a new art movement, but a new theoretical formulation of art theory. That Sérusier could accomplish this in so short a time was a direct consequence of the conceptual nature of the art in question: The Talisman was not important for its craftsmanship or its observation of the visual nature of its subject, but because it recorded an idea in a simple form that could be recognized directly by its viewers. When it was seen by a receptive audience of young art students, together with a few sentences of Gauguin’s instructions as reported by Sérusier, its impact on them was immediate.

The first major artistic movements of the twentieth century originated in Paris, as Fauvism and Cubism were both products of collaborations among young painters in the city. Most of the movements that in turn built on Fauvism and Cubism also took their mature form only after their leading members had seen that work at first hand in Paris and had encountered some of the artists who had worked in those earlier movements. Thus before the outbreak of World War I not only the most important French painters of the next generation, but also such major figures from elsewhere in Europe as Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, Umberto Boccioni, Gino Severini, and Piet Mondrian were among the scores of young artists who spent time in Paris working and studying the accomplishments of Picasso, Matisse, and their collaborators.

A major departure from this pattern occurred, however, as Kazimir Malevich made a radical breakthrough to abstract painting in Moscow in 1915 without ever having visited Paris. Malevich’s Suprematism was based on Cubism as well as other western European conceptual advances, but Malevich was able to learn about these without leaving Moscow. Malevich had moved to Moscow from his native Ukraine in 1907. There he met a group of talented young artists, including Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova, with whom he worked and exhibited. In Moscow, Malevich saw the results of recent developments in advanced art in several settings. In 1908 a major public group exhibition organized by Russian artists included a survey of French art from Cézanne to Picasso. For a number of years Malevich was able to see the most recent work of Matisse, Picasso, Braque, and others in the private collection of Sergei Shchukin, a wealthy Russian merchant who was one of the first important collectors of the young French artists. Malevich followed the development of Fernand Léger’s work through photographs carried from Paris to Moscow by a Russian painter, Alexandra Exter, a pupil of Léger’s who divided her time between France and Russia. He learned of the conceptual breakthroughs of Italian Futurism by reading the manifestos and pamphlets published by Boccioni and his colleagues. As John Golding observed in considering the impact of these published articles on Malevich and other young artists, these manifestos “were almost invariably blueprints for art that was about to be produced, . . . and this explains why the influence of Italian Futurism was to be . . . entirely disproportionate to that of its artistic and intellectual achievements: it provided artists all over the world with instant aesthetic do-it-yourself kits.”53

Malevich’s paintings from the years leading up to his 1915 departure into abstraction clearly reveal the direct influence of the most recent innovations of many advanced French and Italian conceptual painters, including Matisse, Picasso, Braque, Léger, Duchamp, and the Italian Futurists, in spite of the fact that he had never worked with, or even met, any of these artists. Even Malevich’s radical leap of 1915, in which he launched the Suprematist movement with an exhibition that included his painting Black Square, demonstrated his understanding of the process of conceptual innovation, as it had developed in western Europe. Thus not only did the flat geometric shapes of his abstract paintings reflect his analysis of the Synthetic Cubist collages of Picasso and Braque, but the paintings were accompanied by the Suprematist Manifesto, which presented an ambitious intellectual rationale for the artworks, reflecting lessons Malevich had learned from the Futurists about the value of published theoretical declarations for new conceptual art movements.54

Later in the twentieth century major geographic shifts occurred in the production of advanced art. The transmission of experimental art, however, initially continued to require direct extended contact between the artists, or groups of artists, involved. The development of Abstract Expressionism benefited decisively from the presence in New York of a number of European artists who came to the United States to escape Fascism. Hans Hofmann, who founded an art school in New York in 1933, had lived in Paris and Munich, and brought with him a deep understanding not only of the art of the School of Paris but also of German Expressionism, which he communicated through his lectures as well as his paintings. The young Chilean Surrealist painter Roberta Matta came to New York from Paris in 1941 and introduced Robert Motherwell, William Baziotes, and Jackson Pollock to the Surrealists’ theory of automatism.55 Even earlier, in 1936 the Mexican muralist David Siqueiros started a workshop in New York to experiment with new techniques and technologies, with the goal of producing large-scale works more quickly and efficiently than could be done with brushes. There Pollock and other young artists sprayed, poured, and spattered new synthetic paints onto canvases in the service of Siqueiros’s desire to use “controlled accidents” in making art.56 Pollock’s experiences with these new methods of applying paint to large surfaces must have contributed to the development of his signature drip method of painting a decade later. Some of the Abstract Expressionists served informal apprenticeships with older American painters. Milton Avery attracted a group of young followers, including Adolph Gottlieb, Barnett Newman, and Mark Rothko, who met for weekly sketching classes in Avery’s apartment. Avery’s simplified forms, flat areas of expressive color, and quiet atmospheric effects influenced these younger painters, and even Rothko’s use of thinned paint in his later work may have resulted from his early studies with Avery. Rothko stressed the importance of this direct contact for his education as an artist in his eulogy for Avery in 1965: “The instruction, the example, the nearness in the flesh of this marvelous man—all this was a significant fact—one which I shall never forget.”57 Whoever their teachers, and whatever the form their lessons took, the Abstract Expressionists’ educations were heavily based on long sessions spent working together in studios, and arguing in cafeterias and bars, for their achievements were based on gradual development rather than sudden breakthroughs.

The same would not be true for the conceptual innovators of the next generation, whose achievements arrived quickly and early. Frank Stella first saw Jasper Johns’s paintings, at Johns’s first one-man show, at Leo Castelli’s gallery in 1958. Stella later recalled his reactions to Johns’s targets and flags: “The thing that struck me most was the way he stuck to the motif . . . the idea of stripes—the rhythm and interval—the idea of repetition. I began to think a lot about repetition.” Stella was then a senior in college. He did not meet Johns, and his teachers at Princeton were hardly sympathetic to his new interest in Johns’s art. (One of them, the artist Stephen Greene, was so amused by one of Stella’s paintings that resembled a flag that he wrote “God Bless America” across the canvas.)58 Yet Stella persisted, and just a year later, during 1959, he painted most of the Black Series, which, as shown earlier in table 2.5, remains the most often reproduced body of work of his celebrated career.59 In 1960, Stella exhibited these paintings at his own first one-man show, also at Leo Castelli’s gallery.

Soon significant instances of borrowing conceptual innovations would occur that did not involve even direct sight of the original art. As a student in Düsseldorf in the early 1960s, Sigmar Polke saw reproductions of early examples of American Pop Art. Polke quickly adapted to his own purposes Warhol’s use of enlarged newspaper photographs and Lichtenstein’s painted imitations of printed Ben Day dots. When Polke showed the resulting paintings in Düsseldorf in 1963, in an exhibition that he and two fellow students presented in the condemned premises of a vacant furniture store, his German version of Pop Art quickly established him, at the age of 22, as a leader of his generation of German artists.60 Polke and his friends had no desire to hide the foreign source of their techniques, as they proudly declared their relationship to the Anglo-American Pop movement, stating in a press release that theirs was “the first exhibition of ‘German Pop Art.’ ”61

Rapid borrowing and utilization of new artistic devices, across ever wider geographic areas, has become increasingly common in recent decades, in which conceptual approaches to art have predominated. One indication of this progressive globalization of modern art is that art historians are finding that they are no longer able to divide their subject as neatly along geographic lines as in the past. There are many published histories of French, or European, modern art from the mid–nineteenth century to World War I or to the mid–twentieth century, and there are many histories of American art from World War II through the 1960s. For more recent periods, however, art historians are finding these geographic restrictions to be more problematic in producing their narratives, not only because it is less clear that there is a single dominant locus of the advanced art of the past half century, but also because artistic influence has spread more rapidly and freely over a wider area in recent times.62

Conceptual innovations can often be borrowed more readily than experimental ones because they are typically less complex, and because they are less tied to specific artistic goals. Thus during recent decades many artists have used earlier conceptual techniques in ironic ways, without concern for their original intent. If the art world continues to be dominated by conceptual approaches, we should expect that the major innovators of the future will not only continue to emerge at very young ages, but that they will also be spread more widely across countries and continents. So, for example, in 1965 the German art historian Werner Haftmann closed his survey Painting in the Twentieth Century with a prediction: “It is quite possible that the fundamental point of view expressed in this book reflects a historical situation that has already begun to change. I have written it as a European historian, about modern Western art. In a few decades such an undertaking may be inconceivable and it may only be possible to write as a world historian about world painting.”63

In 1969, a leading New York dealer in conceptual art named Seth Siegelaub specifically described, and celebrated, the connection analyzed here between globalization and the conceptual nature of contemporary art:

I like the idea of things, information, people, ideas moving back and forth. And now that has much to do with a quality of the art too. It can travel very easily, and it can be seen on a primary level, not just photographs of something but the something itself. The idea of primary information as opposed to secondary or tertiary information. Or hearsay. It’s happening very, very quickly. And it makes communications even quicker. Just send a letter in the mail and you know what it’s about. You don’t have to wait for a painting to arrive, like someone in Europe wouldn’t see a Pollock until the late fifties or early sixties, whenever the show took one over. Those days are over. And the idea that people can make art wherever they live, that they don’t have to necessarily come to New York and be part of the scene, I like that too.64

To date there has been no systematic study of the changing composition by nationality of leading contemporary artists, but there are a number of indications that Siegelaub was correct, and that the globalization of fine art was already progressing rapidly during the 1960s. One source of evidence is published surveys of recent developments in art. So, for example, table 4.11 is based on an analysis of a textbook published in 2002 titled Art since 1960, written by an English scholar named Michael Archer. The analysis of the book for table 4.11 was done by identifying the country of birth of every artist mentioned in the text. The table summarizes the number of different countries of origin of these artists, according to the decades in which the artists were born. The evidence shows a sharp increase in the number of countries represented over time, with approximately a tripling from the birth cohort of the 1910s to those of the 1930s and beyond. Thus, for example, the artists considered in the book who were aged 41–50 in 1960, the book’s starting point, came from a total of just eight different countries, whereas those aged 21–30 in 1960 represented fully 27 different countries. Detailed examination of the evidence reveals that a number of Asian and African countries, including China, India, Iran, Korea, Morocco, and Tunisia, are represented for the first time in Archer’s book by artists born during the 1930s, who were in their 20s and 30s during the 1960s, when conceptual approaches to fine art began to dominate.

TABLE 4.11

Number of Different Countries of Origin of Artists Mentioned in Art since 1960, by Birth Cohort of Artists

Decade of Artist’s Birth |

Number of Countries |

1890–99 |

6 |

1900–1909 |

5 |

1910–19 |

8 |

1920–29 |

18 |

1930–39 |

27 |

1940–49 |

22 |

1950–59 |

26 |

1960–69 |

23 |

Source: Michael Archer, Art since 1960.

Although the evidence of table 4.11 is drawn from a single source, there is little doubt that its substance could be replicated from many others: that there has been a widening of the geographic locus of contributors to fine art in recent decades has become a commonplace among observers of the art world. Thus recent surveys of modern art routinely close their narratives with chapters titled “Global Crosscurrents” or “Issue-Based Art and Globalization.”65 The nature of this globalization is in greater question, as, for example, Michael Archer observes in the final chapter of Art since 1960 that whether there has been “an expansion to accommodate different, often conflicting, attitudes to art, its market and the manner in which it functions socially, or whether it is more properly identifiable as an expansion of a Western model of art into new market areas, is debatable.”66 Yet regardless of the answer to Archer’s question, the dominance of conceptual approaches to fine art in the recent past has clearly served to accelerate the spread of new artistic ideas, and therefore the process of globalization of the production of art in our time.