The preceding chapters of this book have been concerned with defining, elaborating, and applying the analysis of the two types of artistic creativity and their associated life cycles. This chapter will conclude the book by placing this analysis in perspective from several different vantage points. The first of these will consider instances in which important modern artists recognized the distinction between experimental and conceptual practitioners. The second section will then examine the views of a number of other artists on the relationship between age and artistic creativity. The third section will compare my analysis with that of psychologists who have studied the life cycle of human creativity. Finally, a fourth section will consider the implications of my research for understanding creativity more generally.

Years ago Michael Longley wrote an essay on poets from

Northern Ireland in which he made a distinction

between igneous and sedimentary modes of poetic

composition. In geology, igneous rocks are derived from

magma or lava solidified below the earth’s surface,

whereas sedimentary ones are formed by the deposit and

accumulation of mineral and organic materials worked

on, broken down, and reconstituted by the action of

water, ice, wind. The very sound of the words is suggestive

of what is entailed in each case. Igneous is irruptive,

unlooked-for and peremptory; sedimentary is steady-

keeled, dwelt-upon, graduated.

Seamus Heaney1

The distinction between experimental and conceptual innovators is not a new one in the study of the arts. Although it has never been the primary subject of any significant investigation, it has been noted in passing by a number of critics and scholars. Some of these observations have been quoted in the course of earlier discussions in this book.

Yet perhaps more interesting is that aspects of this distinction have also been considered by a number of artists. One instance occurred in an essay by the poet Stephen Spender published in 1946. Spender described differences among poets in methods of composition:

Different poets concentrate in different ways. In my own mind I make a sharp distinction between two types of concentration: one is immediate and complete, the other is plodding and only completed by stages. Some poets write immediately works which, when they are written, scarcely need revision. Others write their poems by stages, feeling their way from rough draft to rough draft, until finally, after many revisions, they have produced a result which may seem to have very little connection with their early sketches.

Spender noted that the first of these types was “the more brilliant and dazzling,” but he was careful to insist that the difference between the two types did not have any implications for the quality of the final product: “Genius, unlike virtuosity, is judged by greatness of results, not by brilliance of performance.” The difference instead involved the artistic process: “One type . . . is able to plunge the greatest depths of his own experience by the tremendous effort of a moment, the other . . . must dig deeper and deeper into his consciousness, layer by layer.”

Spender did not pursue the implications of his distinction, for this analysis merely served as a preamble to a discussion of his own—experimental—process of composition; its real purpose was clearly to preempt potential criticisms of his own plodding procedures. Thus he embarked on a detailed illustration of his struggles with several poems after stressing that although a poet “may be clumsy and slow; that does not matter, what matters is integrity of purpose.”2

On several occasions, William Faulkner used the distinction between experimental and conceptual art in the course of explaining why he considered his own work superior to that of his contemporary and fellow Nobel laureate Ernest Hemingway. In interviews, Faulkner noted that “there were sculptors, there were few painters, there were few musicians, like Mozart, that knew exactly what they were doing, that used their music like the mathematician uses his formula.” Having identified Mozart as the prototype of the artist who worked with deductive certainty, Faulkner then coupled Hemingway with the composer, pointing out that not all artists have “whatever the quality that Mozart, Hemingway had.” Faulkner explained that whereas Hemingway had early learned a style that he had consistently used thereafter, other authors, including Thomas Wolfe and Faulkner himself, had not, because “we didn’t have the instinct, or the preceptors, or whatever it was, anyway. We tried to crowd and cram everything, all experience, into each paragraph. . . . That’s why it’s clumsy and hard to read. It’s not that we deliberately tried to make it clumsy, we just couldn’t help it.” Faulkner acknowledged that Hemingway had “done consistently probably the most solid work of all of us,” because of his early discovery of a method that satisfied him. Yet Faulkner considered Thomas Wolfe the greatest writer of his generation, because of the ambition of his attempt: “He failed the best because he had tried the hardest, he had taken the longest gambles, taken the longest shots.” In contrast, Faulkner ranked Hemingway not only below Wolfe, but also below Erskine Caldwell, John Dos Passos, and Faulkner himself, because Hemingway had stuck to his early method “without splashing around to try to experiment.”

Faulkner wasn’t troubled by failure, since he considered it inevitable: “None of it is perfection . . . and anything less than perfection is failure.” The measure of a writer was consequently not success, but how hard “he tried . . . to do what he knew he couldn’t do.” In simple terms, he stated the experimental author’s creed: “I think that the writer must want primarily perfection. . . . He can’t do it in this life because he can’t be as brave as he wishes he might, he can’t always be as honest as he wishes he might, but here’s the chance to hope that when he has pencil and paper he can make something as perfect as he dreamed it to be.” Appropriately for a great experimental writer whose favorite book was Don Quixote, Faulkner judged artists by the nobility of their quest for the impossible dream: “It was simply on the degree of the attempt to reach the unattainable dream, to accomplish more than any flesh and blood man could accomplish, could touch.”3

In a lecture given in 1951 at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, Wallace Stevens remarked that there was a division between two classes of modern poetry that also existed between the factions in modern painting:

Let me divide modern poetry into two classes, one that is modern in respect to what it says, the other that is modern in respect to form. The first kind is not interested primarily in form. The second is. The first kind is interested in form but it accepts a banality of form as incidental to its language. Its justification is that in expressing thought or feeling in poetry the purpose of the poet must be to subordinate the mode of expression, that while the value of the poem as a poem depends on expression, it depends primarily on what is expressed.

Stevens left little doubt of his identification with this first type when he proceeded to treat the concerns of poets of the second type: “One sees a good deal of poetry . . . in which the exploitation of form involves nothing more than the use of small letters for capitals, eccentric line-endings, too little or too much punctuation and similar aberrations. These have nothing to do with being alive.”4 Stevens’s emphasis on the primacy of subject matter over form was consistent with the experimental nature of his poetry. His message also appealed to the Abstract Expressionist painters as they struggled against the rise of conceptual art later in the 1950s.5

In a lecture given in 1965, the Italian poet and movie director Pier Paolo Pasolini distinguished between two cinematic traditions from the vantage point of semiology. Pasolini explained that the older of the two traditions in film, which he called the language of prose, was concerned with rational, illustrative, logical methods of narrative, and had initially emerged to profit from the availability of an audience of consumers vastly larger than existed for other kinds of art. In contrast, Pasolini observed that the trend of recent cinema had been toward the use of instruments drawn from the irrational world of memory and dreams, which he called the language of poetry: “The principal characteristic of these [recent] indications of a tradition of the cinema of poetry consists in a phenomenon which technicians define normally and tritely as ‘making the camera felt.’ In sum, the maxim of wise filmmakers in force up till the ’60s—‘Never let the camera’s presence be felt’—has been replaced by the opposite.” That Pasolini’s distinction is in fact the same as that between experimental and conceptual films is made clear by his subsequent relation of these two different technical approaches to an underlying philosophical difference of intention. Thus in his view filmmakers who used the language of prose were interested in making statements of truth, while those who used the language of poetry were interested in the process of cognition: “These two opposite points, gnosiological and gnomic, indiscussibly define the existence of two different ways of making films: of two different cinematic languages.”6

What is almost certainly the most influential description of an experimental artist appeared in a work of fiction that has fascinated generations of modern painters. This is the characterization of the aged master Frenhofer created by Honoré de Balzac in his novella The Unknown Masterpiece, published in 1837. Frenhofer has spent years pursuing an aesthetic ideal of beauty: “Form’s a Proteus much more elusive and resourceful than the one in the myth—only after a long struggle can you compel it to reveal its true aspect.” He is tormented by the inadequacy of artistic methods for the goal of capturing reality: “Line is the means by which man accounts for the effect of light on objects, but in nature there are no lines—in nature everything is continuous and whole.” He recognizes that his extended research has had a chilling effect on his achievement: “There’s no escaping it; too much knowledge, like too much ignorance, leads to a negation. My work is . . . my doubt!” Yet he persists in his decade-long effort to produce a single perfect painting: “It’s ten years now, young man, that I’ve been struggling with this problem. But what are ten short years when you’re contending with nature?”

Another painter, Porbus, respectfully offers an analysis of Frenhofer that has since been applied to a number of great experimental painters: “Frenhofer’s a man in love with our art, a man who sees higher and farther than other painters. He’s meditated on the nature of color, on the absolute truth of line, but by dint of so much research, he has come to doubt the very subject of his investigations.” The pragmatic Porbus sympathizes with Frenhofer’s uncertainty, but refuses to be paralyzed by its extremity, and offers more practical advice to a student: “Practice and observation are everything to a painter; so that if reasoning and poetry argue with our brushes, we wind up in doubt, like our old man here, who’s as much a lunatic as he is a painter. . . . Don’t do that to yourself! Work while you can! A painter should philosophize only with a brush in his hand.”7 But Frenhofer himself is beyond help. His uncompromising pursuit of the impossible can have only one outcome, and the final sentence of the novella reveals that he has died after burning all his canvases.

Many modern artists have identified with Frenhofer. The most famous recorded instance of this is contained in Émile Bernard’s account of his visit to Cézanne in Aix in 1904: “One evening I spoke to him of Le chef d’oeuvre inconnu and of Frenhofer, the hero of Balzac’s tragedy. He got up from the table, stood before me, and striking his chest with his index finger, he admitted wordlessly by this repeated gesture that he was the very character in the novel. He was so moved by this feeling that tears filled his eyes.”8

Other examples of artists’ awareness of the distinction between experimental and conceptual approaches to art might be added, but those discussed here are sufficient to demonstrate that the difference has been understood by modern painters, poets, novelists, and movie directors. This is not surprising, for the difference between the two types of artist lies not simply in how they paint, or write, but even more basically in why they make paintings or write texts. In view of the importance of the distinction, and the richness of its implications for our understanding of the history of the arts, it is unfortunate that scholars of art have not followed the leads given to them by Balzac, Stevens, Faulkner, and other important modern artists.

The talent that matures early is usually of the poetic,

which mine was in large part. The prose talent depends

on other factors—assimilation of material and careful

selection of it, or more bluntly: having something to say

and an interesting, highly developed way of saying it.

F. Scott Fitzgerald, 19409

A few modern artists have also devoted more than casual attention to the question of how and why artists’ work changes over the course of their lives. It is perhaps not surprising that the subtlest and most extensive consideration of the life cycles of both experimental and conceptual artists was given by Henry James. At the age of 50, James published a story, “The Middle Years,” which gives a detailed portrayal of an experimental novelist in old age, as he faces his impending death. Having just received in the mail the published text of what he now knows will be his final novel, Dencombe soon takes a pencil and begins to make changes, for he is “a passionate corrector, a fingerer of style; the last thing he ever arrived at was a form final for himself.” In rereading his last book, Dencombe recognizes, with all the qualifications and ambivalence of an experimental artist, that it is his best work: “Never probably had that talent, such as it was, been so fine. His difficulties were still there, but what was also there, to his perception, though probably, alas! to nobody’s else, was the art that in most cases had surmounted them.” With this recognition, however, comes the painful perception of how slowly his talent had grown: “His development had been abnormally slow, almost grotesquely gradual. He had been hindered and retarded by experience, he had for long periods only groped his way. It had taken too much of his life to produce too little of his art.” Dencombe is overwhelmed by regret that he is dying just when he might have begun to use the skills he had acquired so slowly and painstakingly: “Only today at last had he begun to see, so that all he had hitherto shown was a movement without a direction. He had ripened too late and was so clumsily constituted that he had had to teach himself by mistakes.” But his health is such that he will not have time even to transform his last book into a satisfactory demonstration of his ability: “What he dreaded was the idea that his reputation should stand on the unfinished.” James allows Dencombe some relief only on his deathbed, when the insistence of a young admirer prompts him to admit that he had in fact accomplished “something or other,” and to accept that uncertainty was inevitable: “We work in the dark—we do what we can—we give what we have. Our doubt is our passion and our passion is our task. The rest is the madness of art.”10

In the same year James wrote a review of an exhibition of paintings by John Singer Sargent, who was then 37 years old, in which he gave a penetrating analysis of the career of a conceptual artist. James praised Sargent for his clarity of purpose and confident execution: “It is difficult to imagine a young painter less in the dark about his own ideal, more lucid and more responsible from the first about what he desires. In an altogether exceptional degree does he give us the sense that the intention and the art of carrying it out are for him one and the same thing.” James noted, however, that Sargent’s recent work did not demonstrate development: “As he saw and ‘rendered’ ten years ago, so he sees and renders today; and I may add that there is no present symptom of his passing into another manner.” James was disturbed by Sargent’s precocity, for “it offers the slightly ‘uncanny’ spectacle of a talent which on the very threshold of its career has nothing more to learn”; James found himself “murmuring, ‘Yes, but what is left?’ and even wondering whether it be an advantage to an artist to obtain early in life such possession of his means that the struggle with them, discipline, tâtonnement, cease to exist for him. May not this breed an irresponsibility of cleverness, a wantonness, an irreverence—what is vulgarly termed a ‘larkiness’—on the part of the youthful genius who has, as it were, all his fortune in his pocket?” In conclusion, James praised Sargent’s technical skills: “The gift that he possesses he possesses completely—the immediate perception of the end and of the means.” Yet his final words raised his fear that Sargent would never achieve what James called “the highest result,” which “is achieved when to this element of quick perception a certain faculty of brooding reflection is added. . . . I mean the quality in the light of which the artist sees deep into his subject, undergoes it, absorbs it, discovers in it new things that were not on the surface, becomes patient with it, and almost reverent, and, in short, enlarges and humanizes the technical problem.”11

The validity of James’s fear that Sargent’s best work was already a decade behind him even at the early age of 37 is confirmed by a survey of textbooks of art history published since 1960. The 37 texts examined contained a total of 39 illustrations of paintings by Sargent, 24 of which (62 percent) were executed before the age of 30, and 33 of which (85 percent) had been painted by the time of the exhibition that occasioned James’s review. Sargent would work for more than 30 years beyond that date, but his two most often reproduced paintings—both discussed in James’s review—were executed at the ages of 26 and 28. In view of this quantitative evidence, it is not surprising that Sargent worked conceptually, with careful preparation for his paintings, sketching his patrons before painting their portraits, and making preparatory drawings for his outdoor subjects before executing them in his studio.12

Although both of James’s portraits are remarkable descriptions of the type of artist they treat, his analysis of the dangers of the conceptual approach is perhaps the more impressive of the two. James’s awareness not only of the slow growth of an experimental artist’s skills, but also of the pervasive uncertainty that accompanies that growth, could be attributed to introspection about his own career, but his recognition that the precocity of a gifted conceptual artist would be associated with the danger that the artist would not develop the depth of feeling that we often attribute to great experimental painters could only come from careful observation of artists other than himself.

Most often, it appears that artists who examine the life cycle are aware primarily of only one of the two patterns, specifically that which characterizes their own career. Joan Miró was an important experimental painter, who believed strongly in the value of working by trial and error. So, for example, early in his career he reported to a friend, “I have studied a lot this summer. My two paintings have been changed a thousand times. . . . Perhaps this summer’s paintings will be a struggle more than a result—so much the better.” When Miró was 24, in a letter to another young painter he described the kind of artist he admired, who “sees a different problem in every tree and in every bit of sky: this is the man who suffers, the man who is always moving and can never sit still, the man who will never do what people call a ‘definitive’ work. He is the man who always stumbles and gets to his feet again. . . . [H]e is always saying not yet, it is still not ready, and when he is satisfied with his last canvas and starts another one, he destroys the earlier one.” The next year Miró declared that no artist of this type “will begin to know how to paint until he is 45.” Consistent with this characterization, two decades later Miró told an interviewer of his admiration for two experimental artists, the painter Pierre Bonnard and the sculptor Aristide Maillol: “These two will continue to struggle until their last breath. Each year of their old age marks a new birth. The great ones develop and grow as they get older.”13

Virginia Woolf was probably also thinking about her own development in 1923 when, at the age of 41, she reflected on the life of a great English novelist who had died at that age more than a century earlier. In an essay originally titled “Jane Austen at Sixty,” Woolf declared, “She died at the height of her powers. She was still subject to those changes which often make the final period of a writer’s career the most interesting of all,” and went on to speculate about how Austen’s art might have changed had she lived longer: “She would have known more. . . . She would have trusted less . . . to dialogue and more to reflection to give us a knowledge of her characters. . . . She would have devised a method, clear and composed as ever, but deeper and more suggestive, for conveying not only what people say, but what they leave unsaid; not only what they are, but what life is.” Woolf concluded that in this development Austen “would have been the forerunner of Henry James and of Proust.”14 It would appear that only modesty caused Woolf to omit herself from this group, since her analysis of Austen’s hypothetical later work points to Woolf’s understanding of how a great experimental writer gains in knowledge and depth of understanding as she ages, and in turn becomes an influence on the great experimental writers of later generations.

Poetry is one of the intellectual activities most commonly assumed to be dominated by young geniuses. So, for example, the poet Josephine Jacobsen observed that “in our general conception, old age is a period alien, if not fatal, to poetry. The Shelley-Keats image, the youthful figure of the runner fame never outran, lingers.”15 Interestingly, two great conceptual poets of the early twentieth century offered somewhat more complex general thoughts on how poets’ work changes with age. In a lecture given in 1940, T. S. Eliot observed, “It is my experience that towards middle age a man has three choices: to stop writing altogether, to repeat himself with perhaps an increasing skill of virtuosity, or by taking thought to adapt himself to middle age and find a different way of working.” Eliot argued that the third option was a real one: “In theory, there is no reason why a poet’s inspiration or material should fail, in middle age or at any time before senility. For a man who is capable of experience finds himself in a different world in every decade of his life; as he sees it with different eyes, the material of his art is continually renewed.” Yet Eliot’s empirical judgment was that this was unlikely: “In fact, very few poets have shown this capacity of adaptation to the years. It requires, indeed, an exceptional honesty and courage to face the change. Most men either cling to the experiences of youth, so that their writing becomes an insincere mimicry of their earlier work, or they leave their passion behind, and write only from the head, with a hollow and wasted virtuosity.”16

When Eliot delivered this lecture he was 52 years old. Two years later he completed the Four Quartets and told a friend, “I have reached the end of something.” He had little interest in writing poetry in the more than two decades that remained to him, and a biographer observed that it was “as though the Eliot of the great poems was no longer there.”17 When he gave his lecture in 1940 Eliot may have been unaware of the recent progress of his contemporaries Robert Frost, Marianne Moore, Wallace Stevens, and William Carlos Williams, or perhaps the conceptual Eliot was simply unable to appreciate the great achievements in middle age of these experimental poets who lacked his precocity and brilliance. Whichever the case, Eliot’s judgment clearly applies to conceptual poets like himself, who rise quickly to a high level of achievement, are typically unable later to surpass or even match that early peak, and are often mystified by the loss of their creative powers. It is difficult not to hear a personal sense of loss in a statement Eliot made in that 1940 lecture: “That a poet should develop at all, that he should find something new to say, and say it equally well, in middle age, has always something miraculous about it.”18

Several decades earlier, Eliot’s friend and fellow conceptual poet Ezra Pound had offered a somewhat more skeptical view of the association between youth and poetic achievement. Pound began by rejecting the saying that “a lyric poet might as well die at thirty,” noting that although many people are drawn to producing poetry in early adulthood, the results are not necessarily excellent: “The emotions are new, and, to their possessor, interesting, and there is not much mind or personality to be moved.” As the poet ages, the mind “becomes a heavier and heavier machine” requiring “a constantly greater voltage of emotional energy,” but, since “the emotions increase in vigor as a vigorous man matures,” the result is that “most important poetry has been written by men over thirty.”19 Although this is clearly stated as an empirical conclusion, Pound gave only one example in support, and he may not have expected readers to be greatly impressed by his contention that Guido Cavalcanti produced his best work at 50. Rather than constituting the end product of extensive study, this discussion in an essay written when Pound was 28 might be taken as a theoretical argument that his own best work could still be ahead of him.

A number of modern artists have understood that there is a connection between the nature of an artist’s work and the path of that artist’s creativity over the life cycle. Indeed, Henry James and T. S. Eliot both clearly recognized that there are two distinct life cycles of creativity, and that each can be traced in the careers of specific artists.20 In spite of these major artists’ analyses, however, scholars in the humanities have not used the distinction between experimental and conceptual artists to explain differences in the life cycles of individuals, or as a tool in understanding the development of specific arts—painting, fiction, or poetry—over time. This neglect is unfortunate, but the failure of humanists to carry out systematic comparative analysis is not a new development. In his inaugural lecture as professor of art history at Cambridge University in 1933, Roger Fry declared that “we have such a crying need for systematic study in which scientific methods will be followed wherever possible, where at all events the scientific attitude may be fostered and the sentimental attitude discouraged.”21 Fry’s appeal to his discipline fell on deaf ears at the time, but it is to be hoped that humanists will recognize the gains to their disciplines of heeding it now.

Although humanists have not studied the life cycles of innovators, however, there is a discipline that has done this. The next section of this chapter will examine how psychologists have approached this subject, and how my analysis differs from theirs.

Possibly every human behavior has its period of prime.

Harvey Lehman, 195322

Poets peak young.

James Kaufman, director, Learning Research Institute,

California State University, San Bernardino, 200423

In 1953, the psychologist Harvey Lehman published Age and Achievement, which has since become recognized as a landmark work in the quantitative study of creative life cycles. Lehman’s single goal was “to set forth the relationship between chronological age and outstanding performances,” and through the collection and analysis of vast amounts of data, he did just that for practitioners of a wide range of academic disciplines, arts, sports, and politics.24

Lehman’s methods and results can be illustrated through reference to his treatment of several of the arts considered by the present study. In analyzing oil painting, for example, Lehman used 60 lists of great paintings published by European and American critics to identify the most important painters of the past, which he defined as those artists who had at least one picture on 5 or more of the lists. For each of these 67 artists, Lehman identified the artist’s single best painting as that with the largest number of appearances on the 60 lists. He then distributed these 67 paintings by the ages of the artists when the paintings were executed. Inspection of this distribution “revealed rather conclusively that . . . the great oil paintings were executed most frequently at [ages] 32 to 36.”25

With considerable energy and ingenuity, Lehman carried out similar analyses for scores of other activities. In a summary discussion, he presented the age ranges that represented “the maximum average rate of highly superior production” for 80 fields. Among these were oil painting, ages 32 to 36 (as noted earlier); lyric poetry, ages 26 to 31; and novels, ages 40 to 44.26

A number of psychologists have echoed Lehman’s findings in a variety of contexts. A few recent examples can be cited. In 1989, Colin Martindale commented that “in general, a person’s most creative work is done at a fairly early age, and this age of peak productivity varies from field to field. It is fairly early in lyric poetry . . . (ages 25–35). . . . Only a few specialties, such as architecture and novel writing, show peak performance at later ages (40–45).”27 In 1993, Howard Gardner observed, “While other kinds of writing seem relatively resistant to the processes of aging, lyric poetry is a domain where talent is discovered early, burns brightly, and then peters out at an early age. There are few exceptions to this meteoric pattern.”28 In 1994, Dean Simonton explained that “in some fields creative productivity comes and goes like a meteor shower; the peak arrives early, and the decline is unkind. In other creative domains the ascent is more gradual, the optimum point is later, and the descent is more leisurely and merciful. . . . In the arts, for example, the curve for writing novels peaks much later than that for poetry writing.”29 In 1996, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi noted, “The most creative lyric verse is believed to be that written by the young.”30 And in 1998, Carolyn Adams-Price remarked that “lyric poetry tends to be produced early in life.”31

As these statements indicate, Martindale, Gardner, Simonton, Csikszentmihalyi, and Adams-Price follow Lehman in focusing on a single age period in which practitioners of a particular activity tend to produce their most creative work.32 In general, there must be such a period: if we consider any given intellectual activity, and specify an era of interest, a plurality of the most important innovations in that activity will have been made by people who were in some particular range of ages at the time they made their contributions. It is extremely important to remember, however, that this does not mean that all, or even most, of the major contributions were made by people in that age-group; in fact, that age-group may not account for even a majority of those works. Thus, for example, Lehman’s finding that “the maximum average rate of highly superior production” of lyric poems occurred at ages 26 to 31 does not imply that all poets peak young, nor does it imply that most do; it means only that in his sample, more poets peaked in that age span than in any other. The danger of concentrating on a single prime period for poetry, or any other activity, is that this may cause us to lose sight of the variation in the ages at which great innovators can peak, and that we will consequently fail to discover that different kinds of innovations may be associated with different peak ages. And it appears that in fact this may have occurred in psychologists’ analyses of creativity, as generalizations about the single age period when poets, novelists, or other innovators peak appear to have interfered with their ability to understand creativity at the individual level. For the theory and evidence presented in this book suggest that for the arts considered here—painting, sculpture, poetry, novels, and movies—there is no single phase of the life cycle that dominates the production of important contributions, but instead there are two very different distributions of quality of work by age, with very different peaks, within each art.

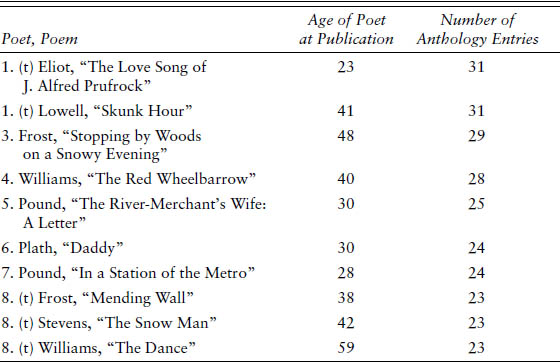

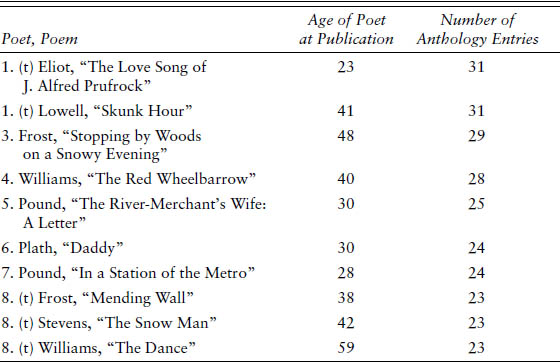

The danger of referring to a single peak age period for an activity can be illustrated with a simple example. Table 7.1 lists the ten poems written by the American poets discussed in chapter 6 that are most often reprinted in the 47 anthologies analyzed for that study. In summarizing table 7.1, we could note that only one age is represented by more than a single entry, and thus conclude that age 30 was the age of maximum production of superior poems by these poets. This is obviously consistent with the results Lehman obtained from a much larger sample, since 30 falls within the range of ages he identified as the best for lyric poets. If we were simply to report that table 7.1 reveals that 30 is the prime age for lyric poets, the psychologists quoted in this section could nod in agreement, secure in their belief that lyric poetry is a young person’s domain.

Yet taking age 30 to represent the evidence in table 7.1 would neglect several important facts. One is that the decade of the 40s has four entries, or more than any other; the 30s have only three entries. And a second is that six of the table’s ten poems were written by poets aged 38 or older, whereas four were written by poets at age 30 or younger. Only if we worried about the significance of these facts would we be prompted to ask why there is such a considerable difference in the ages at which great lyric poets do their best work. Studying this question could then lead us to the conclusion, presented in chapter 6, that Eliot, Plath, and Pound were conceptual innovators, who peaked early, whereas Frost, Lowell, Stevens, and Williams were experimental innovators, who matured more gradually. We would then learn that writing lyric poetry is a more varied and complex activity than Lehman and the other psychologists might believe.

TABLE 7.1

Most Often Anthologized Poems by Poets Listed in Table 6.3

Source: Galenson, “Literary Life Cycles,” table 5.

Recognition of this complexity has been a casualty of the psychologists’ assumption that each activity has a single period of peak creativity. Thus, for example, Dean Simonton offered an explanation for the supposed fact that poets peak at earlier ages than novelists: “Fast ideation and elaboration are characteristic of lyric poetry, whereas writing novels requires more time both for isolating an original chance configuration and for transforming it into a polished communication configuration.”33 Simonton’s concentration on the time required to produce a single poem or novel is misguided, for this simply does not explain the age-creativity profiles of authors. It is true that Sylvia Plath could write a major poem in one day, whereas Mark Twain took almost a decade to complete Huckleberry Finn, but it is also true that Scott Fitzgerald could publish what many critics consider the greatest American novel when he was just 29, and that Robert Frost did not write “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening,” his most frequently anthologized poem, until he was 48. What shapes the age-creativity profiles of writers is not the time required to produce a particular work, but rather the time needed to develop their art. The conceptual approaches of Plath and Fitzgerald, with sudden innovation based on radical departures from existing practices, allowed them to produce great works at early ages, while in contrast the experimental approaches of Twain and Frost, with powers of observation and craftsmanship developed gradually through painstaking trial and error, meant that they reached their greatest heights later in their lives.

Determining whether more poets have been young geniuses or old masters would require extensive quantitative research. Lehman began this process, but his measurements did not allow for possible variation over time in the relative numbers of important practitioners of the two types—not only over long periods, as from one century to the next, but also over shorter ones, from decade to decade. A precise determination would necessarily involve careful time-series analysis, for it is possible that poetry, like painting, has had periods when conceptual approaches dominated, and others when experimental approaches were preeminent; if so, young geniuses may have made the greatest contributions in some periods, and old masters in others.34 Quantitative analysis of this kind has not been done, by Lehman or others. Nor would such studies appear to be a high priority for our understanding of creativity. For what is critically important is not simply to know what single pattern of creativity over the life cycle has been most common in a particular activity, but rather what different patterns have characterized the experience of the greatest innovators, and why. Even if it proved to be the case that young geniuses have been more numerous in poetry than old masters, our understanding of creative genius in modern American poetry would be incomplete if we studied the contributions and careers of Cummings, Eliot, Plath, and Pound and ignored those of Frost, Lowell, Stevens, and Williams. An awareness that both types of poet have made major contributions can lead us to study the differences in the kinds of poetry they produced, yielding a richer understanding not only of modern poetry, but of creativity in general.

At the very least, the identification of a single age period of prime creativity for an activity may cause us to miss the drama of individual variation—the difference, for example, between the 23-year-old Eliot writing “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” while studying philosophy as a graduate student at Harvard, and the 48-year-old Frost writing “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” at the kitchen table of his farm in Vermont. More seriously, however, the assumption that each activity has a single typical life cycle of maximum creativity can lead to a basic misunderstanding of how creativity occurs. Thus, for example, a scholar who works under this belief, and accepts Lehman’s empirical findings for poets, may consider cases like that of Frost as aberrant or, even worse, may not bother to study them at all as a result of the mistaken assumption that they must conform to the general rule that lyric poets peak at early ages. The generalizations of the psychologists quoted here may stem from uncritical acceptance of the findings of Lehman, buttressed by the dramatic examples of Byron, Keats, Shelley, and the other famous young geniuses who died prematurely. Whatever the cause, a mistaken belief that a question has been conclusively studied and answered appears to have led to a failure to notice that the true answer is more complex.

The significance of the difference between the present study and the research of psychologists on creative life cycles concerns the implications of the two approaches for the causal basis of the relationship between the nature, and timing, of the contributions of creative individuals and the activities they pursue. For Lehman and those psychologists who have followed him, the single pattern of creativity over the life cycle that characterizes each activity is effectively assumed to be determined by the activity: poets peak early, novelists later. In contrast, for the present investigation, the pattern of creativity by age is not determined by the activity, but by the approach of the creative individual. It is possible that it is more common for great poems to be written by the young, and great novels by their elders, but it is important to recognize that Frost, Stevens, Williams, and other great experimental innovators have found ways to write great poetry late in their lives, just as Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Melville, and other great conceptual innovators have found ways to write great novels early in theirs.

The difference between my approach and that of the psychologists may have a considerable impact on our ability to understand creativity. The psychologists’ belief that the nature of an intellectual activity determines the pattern of the life cycle of contributors to it appears to be founded on the proposition that some activities are more complex than others. Before a scholar or artist can make a significant innovation, he or she must have a firm knowledge of the most advanced current practice in the relevant field. This knowledge can be gained relatively quickly in activities that deal with more abstract concepts, and requires a longer period in activities in which the central ideas are more concrete. Potential innovators can consequently reach the frontier of creativity more quickly in more abstract, theoretical activities than in more concrete, empirical ones, and they can similarly formulate and develop new ideas that go beyond the frontier more rapidly in more theoretical activities than in more empirical ones.35

It is clear that some activities are more complex than others at any moment. Yet what we learn from studying the careers of great innovators is that the complexity of an activity can be changed, sometimes dramatically, by innovations. The psychologists quoted here implicitly assume that the complexity of a field is exogenous to practitioners of that activity, and that it is effectively immutable. On the contrary, I believe that the complexity of a field is endogenous to important innovators, because major innovations often radically change the complexity of an activity. The artists discussed in this book provide many examples. So, for instance, the Abstract Expressionists dominated the advanced art world of the late 1940s and early ’50s with visual works that were highly complex, and generally required long periods of apprenticeship from important contributors. Within a brief span of time, however, in the late 1950s Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg created new conceptual forms of art that were much less complex, and could be assimilated much more quickly, with very brief required apprenticeships. Thus the contributions of Frank Stella, Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and many others who followed Johns and Rauschenberg were highly conceptual, and were generally made much earlier in their careers than those of Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko, and the other important Abstract Expressionists. The nature of an activity isn’t given to important innovators; it is determined by them.

I believe that recognizing the mutability of activities is crucial for understanding the role of innovators. The psychologists’ view of innovators is that they advance their disciplines or arts. In contrast, my analysis recognizes that innovators not only advance their disciplines, but that they often change them. Great experimental innovators may add substantive content to a previously abstract discipline, while great conceptual innovators may discover ways to simplify previously complex domains.

There is a line among the fragments of the Greek

poet Archilochus which says: “The fox knows many

things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing”. . . .

[T]aken figuratively, the words can be made to yield

a sense in which they mark one of the deepest

differences which divide writers and thinkers, and, it

may be, human beings in general. For there exists a

great chasm between those, on one side, who relate

everything to a single central vision . . . and, on the

other side, those who pursue many ends. . . . The first

kind of intellectual and artistic personality belongs

to the hedgehogs, the second to the foxes.

Isaiah Berlin, 195336

Some of the reasons for attention to the creative

process are practical. . . . [I]nsight into the processes

of invention can increase the efficiency of almost any

developed and active intelligence.

Brewster Ghiselin, 195237

The significance of the analysis presented in this book may be considerable, for I believe it is likely that the distinction between experimental and conceptual innovators exists not only in the arts, but in virtually all intellectual activities. The work involved in testing this hypothesis for academic disciplines may be substantial, but a start has been made in recent research. Thus a study of the life cycles of the Nobel laureates in economics who were born in or before 1926 has found that scholars categorized as conceptual were most likely to publish their most frequently cited work at the age of 43, whereas those categorized as experimental were most likely to publish their most cited work at 61. The study furthermore found that when the conceptual laureates were divided according to the degree of abstraction of their major contributions, those classed as extreme conceptual innovators—that is, those who worked at very high levels of abstraction—published their best work at a mean age of 36, compared with a mean age of 45 for their moderate conceptual counterparts.38 For some very important innovators in economics, this research therefore supports the prediction that scholars who work deductively generally do their most important research considerably earlier in their careers than those who work inductively; it also indicates that among the deductive scholars, those who work at higher levels of abstraction generally produce their major contributions significantly earlier than their counterparts who typically work at lower levels of abstraction.

The possibility that the present analysis is applicable to all intellectual activities obviously increases the importance of pursuing our examination of the implications of the analysis. To conclude this book, this section will summarize some basic characteristics of each of the types that appear to be general to all the activities considered in this study, then examine some ways in which an artist or scholar of either type might increase his or her creativity.

The consideration in this book of the work and careers of experimental and conceptual innovators in a number of arts demonstrates not only that there are clear differences in basic characteristics of the work of the two types of artists, but also that there are significant similarities within each of the categories across the arts. These provide the basis for general descriptions.

Conceptual innovators historically have been those artists most likely to be described as geniuses, as their early manifestations of brilliance and virtuosity have been taken to indicate that these individuals were born with extraordinary talents. Conceptual innovators normally make their most important contributions to a discipline not long after their first exposure to it. These precocious innovators are often perceived as irreverent and iconoclastic: in many cases their lack of respect for earlier work in their disciplines has figured prominently in their ability to make bold departures from existing practices. Many extreme conceptual innovators do not spend long periods acquiring the complex skills common to many practitioners of their disciplines, in some cases because the extreme simplifications they make in their work can allow them to avoid the need for those skills. The central elements of conceptual innovators’ major contributions often arrive in brief moments of inspiration, and they can often be recorded and communicated very quickly. Their innovations often involve radical leaps, producing work that has no relation to their own earlier output. Detractors often consider their work to be naive and simplistic, but admirers perceive that its power lies in its simplicity and generality. A fundamental characteristic of conceptual innovators is certainty; most have great confidence in the validity and significance of their contributions, and this allows them to put forward dramatic new works early in their careers in spite of their knowledge that most practitioners of their disciplines will be hostile to their new ideas.

Experimental innovators are most often praised for their wisdom and judgment. Their major contributions typically involve superb craftsmanship, the result of painstaking effort and experience acquired over the course of long careers. Experimental innovators are celebrated for the depth of their understanding and respect for the traditions of their disciplines. Even their major works are not generally intended as definitive statements, but are provisional, subject to later modification or further development, reflecting their author’s lack of certainty in their accomplishment. Uncertainty is perhaps the most common characteristic of great experimental innovators; if conceptual innovators typically live in a world of black and white, experimentalists instead see only a highly nuanced range of shades of gray. Because of this, detractors often consider their work indecisive and unresolved, while admirers see in it subtlety and realism. Their uncertainty is the basic cause of the gradual nature of the progression normally seen in their work over time, as their styles evolve slowly through cautious and extended experimentation. Their uncertainty is also often directly reflected in their work, for their art often contains explicit or implicit statements of ambiguity and irresolution.

A few examples can make these generalizations more concrete. Robert Frost was an experimental artist who believed in following the traditional rules of his art strictly. He famously denounced a deviation from those rules that was becoming increasingly popular among modern poets by declaring, “I had as soon write free verse as play tennis with the net down.”39 When another poet objected that you could play a better game with the net down, Frost replied that that might be so, “but it ain’t tennis.”40 For Frost, the essence of poetry lay in the craftsmanship that allowed the poet to express himself within the constraints created by traditional meters, and he worked within their discipline throughout his life; as Robert Lowell observed, “He became the best strictly metered poet in our history.”41

Ezra Pound was Frost’s antithesis, a conceptual artist who had no qualms about breaking traditional rules. In a characteristically brash and definite early statement of his credo, Pound declared, “I believe . . . in the trampling down of every convention that impedes or obscures . . . the precise rendering of the impulse.”42 One such convention was traditional meter. Many years later he looked back with satisfaction on the revolution he had promoted in modern poetry in his youth, and remarked, “To break the pentameter, that was the first heave.”43 Pound understood the problem of communication that existed when the brilliant young conceptual artist faced the older and wiser experimentalist: “A very young man can be quite ‘right’ without carrying conviction to an older man who is wrong and who may quite well be wrong and still know a good deal that the younger man doesn’t know.”44

Frost and Pound highlight the contrasting attitudes of the experimental and conceptual artist. To the experimentalist, a conceptual innovation may simply be perceived as cheating; so for Frost free verse was illegitimate, and could have no possible justification. In contrast, to the conceptual innovator, breaking the rules of an art may have a positive value if it achieves a desired end; so for Pound discarding the convention of traditional meter was to be looked on with approval, as the creation of a new and better form. A basic difference underlying this disagreement involves whether the artist believes in the existence of a definite goal that can actually be achieved. For a conceptual artist there is a specific goal that is within reach, and the end of achieving it can justify the means used to do so. In contrast, for the experimentalist the goal is imprecise and probably unachievable, and since the end cannot be reached there can be no justification for attempting to do so with illegitimate means.

Another illustration of the differing vantage points of experimental and conceptual artists is afforded by Virginia Woolf’s account of her difference of opinion with T. S. Eliot over James Joyce’s Ulysses. When Woolf began reading Ulysses shortly after it was published, she reported in her diary that her initial enjoyment of the first few chapters soon evaporated, and that she became “puzzled, bored, irritated & disillusioned as by a queasy undergraduate scratching his pimples.” She puzzled over Eliot’s high opinion of it: “Tom, great Tom, thinks this on a par with War & Peace.” Several weeks later Woolf finished Ulysses and judged it “a misfire. Genius it has I think; but of the inferior water.” She found the book pretentious and questioned Joyce’s judgment: “A first rate writer, I mean, respects writing too much to be tricky; startling; doing stunts. . . . [O]ne hopes he’ll grow out of it; but as Joyce is 40 this scarcely seems likely.” She clearly recognized that Joyce was a fox, and Tolstoy a hedgehog, as she described the experience of reading Ulysses: “I feel that myriads of tiny bullets pepper one & spatter one; but one does not get one deadly wound straight in the face—as from Tolstoy, for instance; but it is entirely absurd to compare him with Tolstoy.”

Eliot, who had completed The Waste Land, his own conceptual masterpiece, just a few months earlier, understood that Ulysses was a conceptual landmark that would have a profound impact on the modern novel. The experimental Woolf could not accept that it was important, however, because she found in it no “new insight into human nature.” For Woolf, a great novelist was one, like Tolstoy, “who sees what we see,” and portrays a real world, “in which the postman’s knock is heard at eight o’clock, and people go to bed between ten and eleven.” Although Eliot defended Joyce as “a purely literary writer,” to Woolf he was little more than a precocious schoolboy who did tricks to attract notice.45

With the understanding that has now been built up of the two types of innovator, it might be useful to turn to what Brewster Ghiselin called the practical reasons for examining the creative process. What implications does the analysis developed here have for increasing the creativity of artistic or scholarly innovators? This discussion must necessarily be speculative, but it does seem possible to use our knowledge of the advantages and disadvantages of the two types of innovator to suggest both the dangers and the opportunities they face in general.

There is a traditional and romantic belief that brilliant young conceptual innovators lose their powers as they age because they have simply used up some natural endowment of ideas or insight that was initially fixed in quantity: when that stock is exhausted, their genius is gone. Late in his life, F. Scott Fitzgerald eloquently expressed this view: “I have asked a lot of my emotions—one hundred and twenty stories. The price was high, right up with Kipling, because there was one little drop of something—not blood, not a tear, not my seed, but me more intimately than these, in every story, it was the extra I had. Now it has gone and I am just like you now.”46 From the vantage point of the present study, however, the inability of Fitzgerald and other aging conceptual innovators to match the brilliant achievements of their youth is not a product of their depletion of a stock of some magical elixir of artistry. Instead, it is caused by the impact of accumulating experience. My analysis implies that the real enemies of conceptual innovators are the establishment of fixed habits of thought and the growing awareness of the complexity of their disciplines. The power of the most extreme conceptual innovations lies in looking at old problems in radically new ways, and in greatly simplifying those problems in the process. Working on a problem long enough to become committed to a single way of approaching it may therefore inhibit new conceptual innovation, and the same may be true for studying a problem long enough to become enmeshed in its details and complications. Conceptual innovators thus face the danger that they will become stuck in a rut, and that they will be able to see no simple way out of it. Even important conceptual innovators may become the captives of an important early achievement and fall into a comfortable but relatively unproductive practice of repeating the same analysis, or effectively continually producing the same product, while adding little new of value.

Picasso and a number of other important conceptual innovators both in art and in scholarship have avoided the danger of this repetition by selecting or posing new problems that differ from their earlier work sufficiently that they are unable to draw on their earlier innovations in tackling them. Conceptual innovators have an advantage in being able to change styles, or problems, quickly, and knowing when to do this can be a key to increasing the number of creative contributions they make over the course of their careers. The more radically they change problems, the greater the potential for large new innovations.

Many successful conceptual innovators have also recognized that their advantage lies in producing simple solutions for old problems. Because the ability to perceive simple generalizations may be progressively reduced in the face of the growing perception of the complexity of a problem, some of these innovators have recognized that it is valuable for them to avoid becoming too thoroughly immersed in detailed empirical evidence or complex methods of analysis. Much of the genius of conceptual innovation lies in being able to absorb enough evidence to allow the formulation of a new solution to a problem, without taking in so much evidence that a simple generalization appears inadequate.

If conceptual innovators are sprinters, important experimental innovators are marathoners. Their greatest successes are the result of long periods of gradual improvement of their skills and accumulation of expertise. Late in his life, Cézanne told Émile Bernard of the benefits and costs of his decades of study: “I believe I have in fact made some more progress, rather slow, in the last studies which you have seen at my house. It is, however, very painful to have to state that the improvement produced in the comprehension of nature from the point of view of the picture and the development of the means of expression is accompanied by old age and a weakening of the body.”47 Old age and illness are not the only obstacles that face experimental innovators, for loss of interest in their work and distractions from it are also common hazards for those whose achievements often come only painfully and slowly. In the face of frustration at this slow pace, it is important to recognize, as Cézanne did, that slow progress is nonetheless progress. Persistence in following a line of research is a virtue for experimental innovators, even when this may be perceived as stubbornness by others.

It is crucial for experimental artists and scholars to recognize what their skills are, so they can select new problems that are sufficiently similar in structure or substance to use to advantage the techniques they have developed and the knowledge they have acquired in the past. Unfortunately, appreciation of their work by others usually comes more slowly, and later in their lives, for experimentalists than for their conceptual peers, but experimentalists have to resist the temptation to try to compete with conceptual practitioners of their own disciplines by changing problems frequently. If they persist, they may find that their reward is a growing mastery of their work as they grow older.

A problem that plagued Cézanne and a number of other great experimental innovators involves deciding when to present their work to the public, by selling or publishing. Many experimentalists have been excessively cautious to show their work. There is a danger that this can slow their progress even further, by effectively limiting the critical reactions to their work that might help them improve it or by reducing the resources they can devote to their work due to lack of professional success. Cézanne was slower than his experimental friend Monet to recognize that it could be valuable to let a piece of his work go when he had achieved something new in it, even though he was not fully satisfied with it, and planned to develop the relevant approach further. Experimentalists tend to be perfectionists, and their enemy is often the belief that each of their works must be definitive. It is important for them to develop the ability to use their uncertainty as a spur to further research, without allowing it to paralyze them. Experimental innovators must learn that unresolved works are not necessarily unfinished, and that even unfinished works can contribute new ideas or approaches to a discipline.

An additional issue of importance for experimental artists and scholars concerns how to react constructively to the advance of age, including the problems caused by what Cézanne called the weakening of the body. As seen in this study, advanced age does not have to reduce creativity: Cézanne was at his greatest after the age of 65, Henry James wrote one of his best novels at 61, and Frans Hals produced his most important painting at 80. More examples could be generated by expanding the study to other great experimental artists. Thus among painters, Pierre Bonnard made his greatest contribution after the age of 65, and Hans Hofmann made his after 80; Elizabeth Bishop wrote “One Art,” one of her greatest poems, at 65; Henrik Ibsen wrote Hedda Gabler and other major plays after the age of 60; and Fyodor Dostoevsky completed his greatest novel, The Brothers Karamazov, at 59, just months before his death.48 Yet these cases appear exceptional, as in all these arts great achievements appear to be relatively rare from the late 50s on. An interesting possibility, however, is suggested by the movie directors examined here, for it is striking that John Ford, Howard Hawks, and Alfred Hitchcock were all at their best during their late 50s and their 60s. Making movies under the Hollywood studio system was obviously a more highly collaborative activity than the other kinds of artistic work considered in this study, and this may have allowed these great directors to use their skills to best advantage without being constrained as severely by their advancing age as they might have been in more solitary activities.

Suggestive evidence in support of this hypothesis comes from another highly collaborative form of art. Thus the great experimental architect Frank Lloyd Wright designed several of his greatest buildings, including Fallingwater and New York’s Guggenheim Museum, after he had passed the age of 65.49 Nor was Wright unique in this respect, for other great modern architects have produced important work at advanced ages: thus Walter Gropius’s Graduate Center at Harvard University was erected when he was 67; Le Corbusier’s Notre Dame du Haut at Ronchamp was erected when he was 63; Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s 860–880 North Lake Shore Drive Apartments in Chicago were erected when was 65; Louis Kahn’s Kimbell Art Museum in Forth Worth was erected when he was 65; I. M. Pei’s glass pyramid at the Louvre was commissioned when he was 64; Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum at Bilbao was erected when he was 68; and Cesar Pelli’s Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur were erected when he was 72.50 A possible lesson for experimental artists and scholars from these great movie directors and architects may involve the benefits of collaboration, for working with younger colleagues or assistants may permit experimentalists to continue to use their valuable skills and expertise to best advantage later in their lives than would otherwise be the case.

I am going on with my research and shall inform you

of the results achieved as soon as I have obtained

some satisfaction from my efforts.

Paul Cézanne to Ambroise Vollard, 190251

The idea of research has often made painting go

astray. . . . The spirit of research has poisoned those

who have not fully understood all the positive and

conclusive elements in modern art.

Pablo Picasso, 192352

Creativity is not the exclusive domain of either theorists or empiricists, nor are major innovations made exclusively by the young or old. In a wide range of intellectual activities, important contributions have been made both by conceptual innovators, who work deductively, and by experimental innovators, who work inductively. The conceptual innovators are most often the young geniuses, who revolutionize their disciplines early in their careers, whereas the experimental innovators are the old masters, whose greatest achievements usually arrive late in their lives.

There is a tension between these two types of innovators, because they differ not only in the methods by which they make their work, but in their conceptions of their disciplines. Conceptual innovators state their ideas or emotions, often summarily and without hesitation, while in contrast experimental innovators think of their careers as an extended process of searching for the elusive means of understanding and expressing their perceptions. The tension between the approaches often causes conflict that is disruptive, but in the long run it can be productive, for conceptual artists and scholars may be forced to take account of new perceptions or evidence generated experimentally, and experimentalists may be forced to increase the scope of their investigations by conceptual discoveries.

This book has shown how the two approaches can be identified in a number of artistic disciplines. It has also demonstrated some of the gains that follow from the recognition of the differences between the approaches. One of the central benefits is a deeper understanding of the role of the life cycle in human creativity.

A basic result that has emerged from this research is the recognition that both conceptual and experimental innovations have played an enormous role in the modern history of each of the artistic activities that have been studied here. The significance of this fact is great, for it implies that aptitude and ambition are more important factors in allowing people to make contributions to a chosen discipline than the ability to think and work in any particular way, either deductively or inductively. And the type of aptitude in question is not necessarily that which has played the greatest role in the discipline in the past, for the results of this analysis demonstrate that innovators do not simply follow, but often change, the approaches that are used productively in their disciplines.

Experimental innovators seek, and conceptual innovators find. Increasing our understanding of the difference can help us gain a better understanding of the development of the disciplines we study, and it may also help us increase our own creativity. For recognizing the difference between experimental and conceptual creativity can serve to give us a better understanding not only of how we think, but also of how we learn.