• • • •

The genomics of extinct humans such as Neanderthals and Denisovans help us understand some very important facets of own species. The inter-breeding scenario aside, comparing those paleogenomes (both mtDNA and nuclear) with our own sheds light on three major aspects of Homo sapiens evolution.

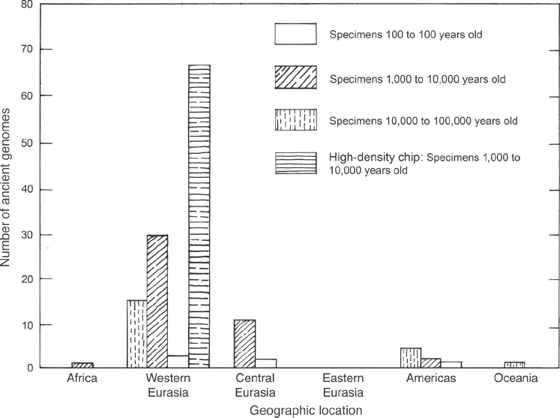

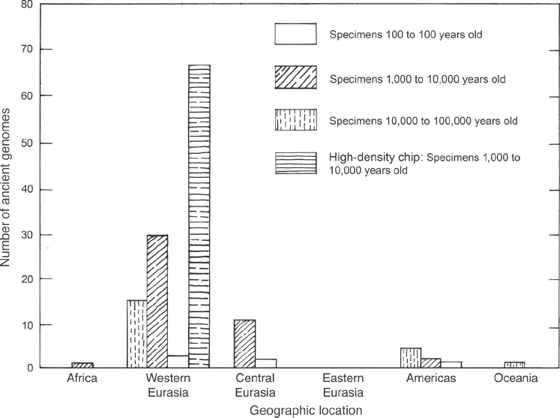

First, it emerges that all living members of our species are very closely related, and distinct from our close extinct relatives. In addition to the genome sequences of members of those extinct species (Denisovan and Neanderthal), and the large-scale genome sequencing studies of large numbers of living humans, many genomes of fossilized Homo sapiens have also been sequenced. Montgomery Slatkin and Fernando Racimo summarized the state of the paleogenomic revolution and counted nearly 150 ancient genomes that have been sequenced since 2008 through either whole-genome sequencing or high-density chip sequencing (figure 10.1).

The figure demonstrates that Europe has been the major focus of ancient genome sequencing and that there is a preponderance of genomes from the one thousand to ten thousand years ago age range. For this reason, the inferences made from paleogenomes are most complete for Europe during the Neolithic (New Stone Age) period. There is a dearth of genomes from almost all other regions of the globe, especially Africa and East Asia. In Africa this is easily explained, as the conditions for preservation of DNA in fossils are not easily met in the sub-Saharan region. And, aside from inhospitable environmental circumstances, Africa and Asia are relatively poorly known, paleoanthropologically. Nevertheless, Rasmus Nielsen and colleagues have recently summarized what we have learned from paleogenomics about how our ancestors moved out of Africa and across the planet.

Figure 10.1 Chart showing the distribution of ancient genomes sequenced from the specified geographic areas. The number of genomes is shown on the y-axis, and the geographic location is on the x-axis. From Slatkin and Racimo (2016).

Since the early 2000s it has been established that what were effectively anatomically modern humans were already living in the eastern African region between about 200,000 and 160,000 years ago. There are claims for “early modern Homo sapiens” in northern Africa before this, but the fossils involved have archaic features, so we can currently put a lower limit of about two hundred thousand years ago for the appearance of our modern species in Africa. Happily, this conclusion agrees pretty well with estimates derived from both genomic and mtDNA data. The genomic information also suggests that our species had a pretty complex history in Africa before spreading out from the continent. In fact, the genomic data indicate that three distinct major African lineages diverged from one another early on, to produce a greatly subdivided population structure. These divergences are of deep (ancient) origin: they are, indeed, the deepest of any of the splits we find encoded in the genomes of modern human populations. A highly detailed study using some three thousand individuals of African ancestry further subdivided these three major lineages into a total of fourteen lineages.

The deepest living human lineage diverged from the ancestral African population between 160,000 and 110,000 years ago, a good 40,000 to 90,000 years before our species started migrating out of Africa. According to Nielsen and colleagues, there were several subsequent events that then shaped the modern structure of human populations in Africa. The biggest migration event within Africa, and one that produced a lot of recontact with other lineages, was a major movement of Bantu-speaking populations from the highlands of Central Africa to other areas of sub-Saharan Africa about four thousand years ago. Two earlier migration events, one at seven thousand years ago and another at five thousand years ago, already had discernible impacts on the structure of African populations. The first dispersal of fully modern people out of Africa had occurred long before these, at around sixty thousand years ago. And while that event probably had negligible impact on the populations remaining in Africa, it led to drastic alterations in the genomic structures of those that migrated.

The fossil record relevant to humanity’s first steps out of Africa is a little hazy. There is some fossil evidence to suggest that anatomically modern humans had made it into the Neanderthal-occupied neighboring Levant more than one hundred thousand years ago; but these people apparently never gained a permanent foothold there. This may have been because they were still behaving in the archaic human manner, for at this period humans were not yet leaving behind archaeological evidence of behaviors related to the radically new form of symbolic reasoning that is such a striking characteristic of Homo sapiens today (such evidence begins to show up in Africa in the one hundred thousand to eighty thousand year time frame). A new fossil date from China suggests that anatomically modern—and potentially symbolically behaving—humans might have made it to the Far East by about eighty thousand years ago; and they were certainly in that region by sixty to forty thousand years ago. Modern humans had reached Europe by well over forty thousand years ago, and shortly thereafter had begun creating the extraordinary tradition of cave art that is the most stupendous and overwhelming early evidence we have for the flowering of the modern human creative spirit.

In 2016, three large studies were conducted using the genomes of people from 270 geographically diverse localities. These studies suggested that the patterns of population divergence of non-African populations can best be explained by an early migration event that ultimately went as far as Oceania and was followed by a further major wave of migration out of Africa. The principal impact on modern human population structures outside Africa was made by the latter wave, but echoes of the earlier migration to Oceania are also detectable in modern genomes. The details of the dispersal routes are hard to infer from current data, but it seems that the first wave traveled to the areas of Australasia and New Guinea, while the second supplied the ancestors of the current Eurasian populations.

The paleogenomic data add very importantly to what we can infer from current genomes. Three fossils, and the inferences made from the comparison of their genomes, are listed in table 10.1. The Mal’ta-Buret paleogenome suggests that twenty-five thousand years ago, a genetic structure existed wherein eastern Asian lineages were already becoming distinct from the western Eurasian ones. The Ust’-Ishim paleogenome indicates that twenty thousand years earlier there had been relatively little genetic differentiation and that the two main lineages had not yet diverged much. These two paleogenomes thus give us between forty-five thousand and twenty thousand years ago as the time range within which the major Asian lineages diverged. Adding the Kostenki 14 paleogenome narrows the range down even further, to between forty-five thousand and thirty-seven thousand years ago.

Fossils and Genomes Weigh in on the Divergence of Asian People from Western Eurasians

| Fossil |

Location |

Age |

Observation |

| Mal’ta-Buret |

Siberia |

25,000 |

Genetic affiliation to both western Eurasians and Native Americans, but a weaker affiliation to East Asians and Siberians |

| Ust’-Ishim |

West Siberia |

45,000 |

Almost equal genetic affinity with western Eurasians, East Asians, and Aboriginal Australians |

| Kostenki |

Russia |

37,000 |

Close affinity to contemporary western Eurasians, but not East Asians |

In the other great surge of people out of Africa and into Asia, fossil evidence pins down the first presence of Homo sapiens in the Oceanian region at about fifity-five thousand to forty-eight thousand years ago. Two separate migrations to the ancient continent of Sahul (Australia, New Guinea, and Tasmania, which were contiguous during the ice ages, when sea levels were lower) are inferred based on fossil, linguistic, and other data. In contrast, paleogenomic data suggest only a single migration to Sahul, followed by divergence due to isolation caused by environmental changes and sea-level fluctuations.

The specifics of the movements of people following these initial great migrations have also been worked out using data from extant human genomes. In Eurasia, two waves of migration had great impacts on population structure. About five thousand years ago, the Yamnaya people migrated both east and west from Siberia, and a thousand years later the Shintashta people migrated east. As figure 10.1 shows, we have no ancient genomes from eastern Asia, so no paleogenomic perspective is possible for this area. However, using the genomes of living Homo sapiens, it is still possible to decipher some of the migrations and movements of people in the region. The Oceanian migration, for example, also subsequently involved submigrations to Polynesia.

The power of the genomic approach here was demonstrated by Jianjun Liu and colleagues (Chen et al. 2009), who looked at 350,000 SNPs in over 6,000 individuals living in China. These researchers were interested in the dynamics of movement of the dominant Chinese Han populations, and their analysis shows a clear north versus south population structure, with more derived genomes in the south, and more ancestral ones in the north. Samples from cities like Beijing and Shanghai did not fit the pattern—understandably enough, given the large numbers of people from all over China who have migrated to these mega-urban centers.

In another study, David Reich and colleagues analyzed 132 individuals in 25 Indian populations, using more than 500,000 SNPs. Their analysis suggested the existence of two major ancient human lineages on the Indian subcontinent: “Ancestral North Indian” (ANI) and “Ancestral South Indian” (ASI). These lineages are very distinct from each other, or, as the authors put it, the ASI population “is as distinct from ANI and East Asians as they [ANI and Eurasians] are from each other” (Reich et al. 2009, 489). The researchers also showed that the ancestral ANI lineage is closely related genetically both to Middle Easterners and to Europeans and suggested that, because of extensive interbreeding, there may not be any individuals left in mainland India who have only ASI ancestry. One offshore exception to this general rule is the Andaman Islanders, who are ASI-related, with no ANI ancestry. Extensive cross-breeding has resulted in most Indian groups having only 40 to 70 percent ANI ancestry. Also in the southern Asian region, John C. Chambers and numerous colleagues (Kooner et al. 2011) examined a sample of over 150 South Asian individuals from Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka using low-coverage whole-genome sequencing and confirmed the basic divergence and the genomic differences of the ANI and ASI lineages.

Paleogenomics has made it much easier to analyze the population structures and migrations of people in the past; and Europe is the best studied of the continents when it comes to paleogenomes. As we write, more than one hundred Eurasian paleogenomes have been generated from a broad range of dates up to around forty-three thousand years ago, the age of the oldest Homo sapiens fossil in Europe. The earliest of these paleogenomes thus shed light on the first modern humans who entered Europe. Based on the genomes available, the best estimate is that there were three major waves of modern immigration into Europe that occurred at different times. The first wave included the “Cro-Magnons,” who left such an extraordinary record of Ice Age cave art and other creative expressions. The second began at the end of the Ice Age some 11,000 years ago; and the third started about 4,500 years ago.

The pre-Neolithic genetic history of Europe is complex, but it appears to have been dominated by a major wave of people who probably contributed rather little to present-day European genomes. The genomic signature of this wave is best detected in the paleogenomes of individuals from the pre-Neolithic period. The second (Neolithic) wave started eleven thousand years ago, with the introduction of agriculture, animal breeding, and a move away from the ancestral hunting-gathering lifestyle. Appropriately enough, the genomes of these early European agriculturalists came from the Fertile Crescent of the Near East, one of the main centers of this economic revolution. Specifically, they seem to have originated in the Anatolian region of modern Turkey. The many paleogenomes available from this time period indicate that a rapid westward movement of people out of Anatolia toward the Iberian Peninsula was complete by about seven thousand years ago and that the northern regions of Europe (Scandinavia and England) were populated by an extension of this wave around six thousand years ago. The third genomic wave saw people from the Ponto-Caspian area migrating into Europe about 4,500 years ago. As we pointed out in chapter 8, John Novembre and his colleagues suggest that genomic structure within Europe is strongly correlated with geography. The underlying genetic content came mostly from the last two waves of migration into Europe, which, as Rasmus Nielsen and colleagues put it, “can explain much of the genetic diversity found in present day Europe” (Nielsen et al. 2017, 305).

The rather tardy peopling of the Americas was also complex and was also clearly accomplished in several waves. The exact timing of the initial entry into the Americas is enigmatic, but more than likely it was accomplished between about fifteen thousand to twenty-three thousand years ago. Among living populations, Siberians are thought to be the closest to Native Americans. But there is also strong evidence that Native Americans were partially founded by populations that were closely related to the Mal’ta paleogenomic lineage (table 10.1). The ancestry of Native Americans also apparently involved input from an as yet unidentified East Asian lineage. This means that, at some time in the past, these two lineages (Mal’ta and unknown) interbred to give rise to the ancestral lineage of Native Americans. It is estimated that the interbreeding or admixture of these lineages took place about 12,500 years ago. This date is interesting, because it almost exactly coincides with the calculated splitting date of the two major lineages of Native Americans at around thirteen thousand years ago, when today’s northern Native Americans appear to have diverged from those Native Americans who migrated south. Amerindians of the far north, such as the Inuit and the paleo-Eskimo, were founded by later migrations that took place three thousand and five thousand years ago, respectively. There is also some evidence of possible Polynesian migration to South America in the past three thousand years, but this latter migratory event needs more study.

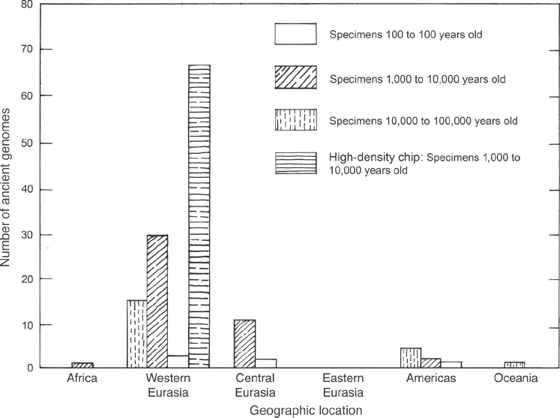

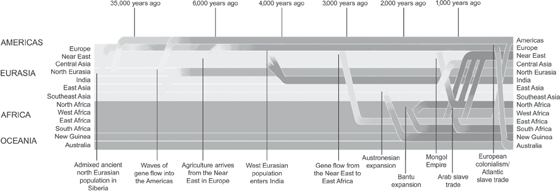

Use of both the genomes of living people and the expanding library of available paleogenomes to infer ancestry and population history has uncovered several unexpected patterns of migration and admixture. And if we wanted to summarize the major lesson that has emerged from this work, we could do no better than to quote Joseph Pickrell and David Reich, two geneticists who have been at its forefront: “Empirical data have shown that the current inhabitants of a region are often poor representatives of the populations that lived there in the distant past” (Pickrell and Reich 2014). To illustrate this, Pickrell and Reich offer one of the clearer examples—the Americas. The current genomic profile of the Americas has been hugely impacted in the last five hundred years by the migration of Europeans and by the horrible practice of importing slaves that produced the movement of Africans to the Americas. These extremely recent events have shifted the modern genomic makeup of the Americas so much that it very little resembles the situation ten thousand years ago. This theme of replacement has arisen repeatedly across the planet, as shown in figure 10.2.

These observations beg for a model to explain how humans moved around the globe, and the “go-to” model for how humans moved out of Africa is what is called “serial founder effect.” A founder effect occurs when a single individual, or multiple closely related individuals, migrate to a new area and “found” a new population. Since we are dealing here with sexually reproducing organisms, you might query that word “single,” but in fact some animals and plants can migrate long distances while fertilized. The Hawaiian Islands, for example, harbor large numbers of insect species that apparently arose as the result of the migration of a single gravid (pregnant) female. When such an event happens, if it survives, the population is inevitably propagated through inbreeding. This inbreeding is also known as a “bottleneck,” because genomic variability is dramatically reduced in the new population relative to what had been present in the parent population. While possible for humans, this kind of super-extreme founder event probably never happened in our species. But our ancestors were nonetheless very thinly spread on the landscape, and bottlenecks involving small groups of closely related individuals would not have been uncommon in human history.

Figure 10.2 Diagram showing the complex migratory patterns of human populations in the last fifteen thousand years. Thirteen current populations are represented in the figure with different colors. The migratory patterns of these populations involve all thirteen populations and involve at least seventeen discernible events. From Pickrell and Reich (2014). See plate 8.

Serial founder events are inferred where genomic analysis reveals a decline in heterozygosity (also inferred as more and more inbreeding) as one goes from the center of origin (in our case, Africa) to increasingly remote regions of the globe. This appears to apply to Homo sapiens, and it makes interpretation of our genomes relative to our dispersal histories relatively simple, because as Pickrell and Reich point out, discovering where our species originated is largely a matter of finding where on the planet genetic diversity is the highest. The serial founder effect has also been used to interpret linguistic and physical anthropological data; but as with any model, the more generalized it is, the less realistic it probably is in practice. And there are other models available to explain what we see.

Specifically, two other models also show a smooth gradual loss of heterozygosity with increasing distance from Africa. The first involves at least two founder events, producing severe bottlenecks along with large amounts of migration between populations that resulted in admixture. The second model does not require bottlenecks, but invokes admixture with another species (Neanderthals, Denisovans) early in the penetration of Homo sapiens beyond Africa. This latter model would also require a lot of recent admixture; but since there is some evidence for both Neanderthal and/or Denisovan admixture (chapters 8 and 9) and recent population admixture (figure 10.2), this model also might also have its appeal. And that is not the limit, for there are other possible versions of our history that incorporate aspects of all three models. Still, regardless of which model is correct, or more accurate, the lesson is the same: our current genomic variability is the product of a past that was rich with interbreeding and admixture. The degree of ancient admixture remains debatable, of course; but the degree to which it occurs today is unarguable.