12

The Extreme Female Brain:

Back to the Future

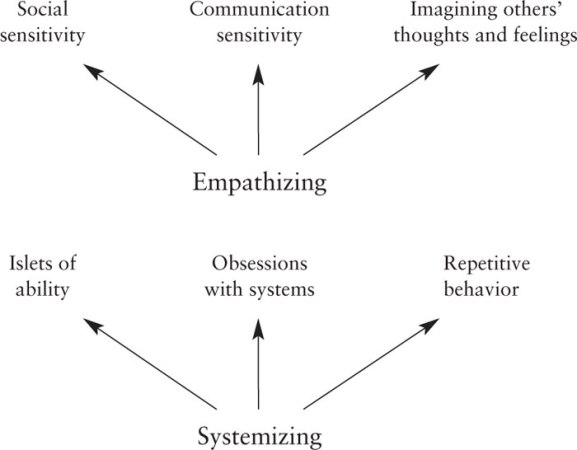

By now we are almost at the end of our journey, at least in terms of the known terrain. We have seen that, according to the model in Figure 8, about 95 percent of the population have one of the following three brain types: the balanced brain (type B), the male brain (type S), or the female brain (type E). A small percentage (about 2.5 percent) have the extreme male brain.

And then we get to the unknown terrain. There is a small percentage (another 2.5 percent) who presumably have the extreme female brain. The what? This is something that I have barely mentioned until this point. But this is the place to discuss it, as it is a topic for future exploration.

The Extreme Female Brain

All scientists know about the extreme female brain is that it is predicted to arise, as we can see from the model in Figure 8. Scientists have never got close up to these individuals. It is a bit like positing the existence of a new animal on theoretical grounds, and then setting out to discover if it is really found in nature.

The existence of chronic pain suggests to neurologists that there might be people in nature who experience no pain. The existence of phobias suggests to psychiatrists that there might be people in nature who experience no anxiety. Neither of these is the sort of problem that turns up in clinics— maybe because people with these problems do not survive very long. Someone who experiences no pain would not learn about things that could burn them, or falls that could injure them, and might not avoid such hazards in the environment. Someone who experiences no anxiety would not learn about other kinds of dangers, and might comfortably stand on a cliff edge or go into a dark alley alone. In evolutionary terms, these individuals may not have survived long enough to pass on their genes, and therefore at this time they may only exist in theory, or at most very rarely. But they might still exist.

Similarly, the map we used to find the extreme male brain suggests that there should be a mirror opposite: the extreme female brain. So what would such people look like?

People with the extreme female brain would fall in the upper left-hand quadrant of the graph in Figure 8, the dark grey area. Their empathizing ability would be average or significantly better than that of other people in the general population, but their systemizing would be impaired. So these would be people who have difficulty understanding math or physics or machines or chemistry, as systems. But they could be extremely accurate at tuning in to others’ feelings and thoughts.

Would such a profile carry any necessary disability? Hyperempathizing could be a great asset, and poor systemizing may not be too crippling. It is possible that the extreme female brain is not seen in clinics because it is not maladaptive.

We saw that those with the extreme male brain do experience a disability, but only when the person is expected to be socially able. Remove this expectation, and the person can flourish. Unfortunately, in our society this social expectation is pervasive: at school, in the workplace and in the home. So it is hard to avoid.

But for those with the extreme female brain, the disability might only show up in circumstances where the person is expected to be systematic or technical. The person with the extreme female brain would be systemblind. Fortunately, in our society there is considerable tolerance for such individuals. For example, if you were a child who was systemblind, your teachers at school might simply allow you to drop mathematics and science at the earliest possible stage, and encourage you to pursue your stronger subjects. If you were a systemblind adult and your car didn’t work, you could just call the mechanic (who is likely to be at least type S). If your computer needs putting together, and you can’t work out which lead goes into which socket, there are phone numbers that you can ring for technical support. And in evolutionary terms, there were in all likelihood equivalent people that a systemblind person could turn to for help when that person’s home was destroyed in strong winds, or when their spear broke.

But what about hyperempathy? Is this invariably a good thing to have, or might it be a problem?

Candidates for the

Extreme Female Brain

You might think that being hyperempathic could lead to difficulties. For example, if you are constantly trying to ascertain the mental states of others, you could attribute intentions to people that they do not have; you might verge on the paranoid, or certainly display an oversensitivity. Could it be that oversensitive or paranoid individuals have the extreme female brain?

Other contenders might be people with hysterical personality disorder, a diagnosis given to individuals who are overwhelmed by emotions (their own and others) to such an extent that they can no longer reason clearly. So are individuals with these psychiatric conditions (for that is what paranoia and personality disorders are) revealing the extreme female brain?

This cannot be the case. If someone is over-attributing intentions, or has become preoccupied by their own emotions, then by definition they are not exhibiting hyperempathy. Hyperempathy is the ability to ascertain the mental states of others to an unusually accurate and sensitive degree, and it can only occur if one is appropriately tuned in to the other person’s feelings. A paranoid person, or someone who is easily inflamed into aggression by suspecting that others are hostile, has a problem. But their problem is not hyperempathy.

Equally, a psychopath may be exceptionally good at figuring out other people’s thoughts and how to dupe them, but this is not hyperempathy because the psychopath does not also have the appropriate emotional response to someone else’s emotional state (recall our original definition of empathy). They might even feel pleasure at someone else’s pain, which is hardly empathic.

Nor would any of the personality disorders easily qualify for the privileged status of an extreme female brain, since a characteristic of the personality disorders is that they are profoundly self-centered. If anything, empathy deficits are also likely to characterize these groups.1

Finally, some people have wondered whether Williams’ Syndrome might be an example of the extreme female brain, as individuals with this syndrome demonstrate good or even superior attention to faces, and can chat easily, despite other aspects of their learning and cognition being impaired. But such sociability can be quite superficial—they may be good at keeping a conversation going, but not really pick up with any special sensitivity what you are feeling and thinking—so again this may not qualify as the extreme of brain type E.2

So we have a good idea what the extreme female brain (or extreme type E) is not. We can draw such conclusions because Williams’ Syndrome, personality disorders, psychopaths and paranoia are all part of the known terrain. But to say what the extreme female brain is requires a best guess about what we might find in the unknown terrain ahead.

New Contenders

One suggestion is that people who are more prone to believe in telepathy might qualify as having the extreme female brain.3 These are not individuals who are prone to believe in any old parapsychological phenomenon (such as ghosts or telekinesis), nor do they have some mild variant of psychosis or schizotypy. Rather, these individuals would need to be healthy and normal in every way except for having this remarkable belief that others’ minds are more transparent to them. And critically, their accuracy in such mindreading would need to be very good, since otherwise their belief in their own telepathy could simply be a delusion.

A second, and to my mind more likely, contender for who might have the extreme female brain would be a wonderfully caring person who can rapidly make you feel fully understood. For example, an endlessly patient psychotherapist who is excellent at rapidly tuning in to your feelings and your situation, who not only says he or she feels a great sadness at your sadness or great pleasure at your pleasure but also actually experiences these emotions as vividly as if your feelings were theirs.

However, the contender for the extreme female brain would also need to be someone who was virtually technically disabled. Someone for whom math, or computers, or political schisms, or do-it-yourself projects held no interest. Indeed, someone who found activities requiring systemizing hard to follow. We may all know people like this, but it is likely that they do not find their way into clinics, except perhaps as staff in the caring professions.

Throughout this book I have explored these two dimensions, empathizing and systemizing, and yet there is still much to be discovered. What are some of the questions and issues that I hope we will have answers to in the next few years? They tend to fall into three key areas: the model, the autistic mind, and society’s options and responsibilities. Let’s briefly look at each of these.

The Model

Are there are some essential sex differences in the mind that are not encompassed by the model shown in Figure 8? Is it really the case that the only important differences between the brains of the average man or woman can be reduced to these two dimensions of empathizing and systemizing? The more familiar examples of sex differences, such as aggression or language skills, have already been discussed in Chapter 4, where we concluded that reduced empathizing in men could give rise to increased aggression, and better empathizing in women could give rise to better communication skills. A challenge for the future will be to identify psychological sex differences that are not easily accommodated by this model.

For example, some people suggest that fear is another sex difference (men being less fearful). But this could still boil down to better systemizing skills in men (in other words, a careful and detached analysis of the risks of flying a plane, or a logical analysis of how to track and trap and kill a predator).

One might also wonder what the two processes of empathizing and systemizing are really like. Are they separate modules in the brain? Are they really independent dimensions? As I mentioned earlier, there seems to be a trade-off for many people, so that a higher ability in one process tends to be accompanied by a lower ability in the other process. Why?

It could be that these two processes reduce to something more general. We can glimpse this possibility by stepping back and reflecting on the nature of the two processes. Systemizing involves exactness, excellent attention to local detail, an attraction to phenomena that are in principle treated as lawful, and context-independence. In other words, what one discovers about the laws relating to buoyancy or temperature should hold true from one context to another. Empathizing, on the other hand, involves inexactness (one can only ever approximate when one ascertains another’s mental state), attention to the larger picture (what one thinks he thinks or feels about other people, for example), context (a person’s face, voice, actions and history are all essential information in determining that person’s mental state), with no expectation of lawfulness (what made her happy yesterday may not make her happy tomorrow). Future research will need to examine the possibility that these two processes are not defined by their topic, but instead by these more general features.

The Autistic Mind

In this book you have come across one model of autism, that of empathizing and systemizing. But it would be improper of me not to refer to other models that have also attempted to explain the riddle of autism. Future work will entail the use of critical scientific experiments to test these competing models against each other, but let’s have a brief look at these alternative models.

It is said that people with autism have “executive function” deficits, for example deficits in planning skills.4 Executive function is shorthand for the control centers of the brain that allow not just planning but also attentionswitching and the inhibition of impulsive action. It is certainly true that individuals with autism with some degree of learning disability (or below average IQ) have executive function difficulties, but it is not yet clear if this extends to what might be considered as “pure” cases of autism, such as those with completely normal or above average IQ.

Executive dysfunction has been found in individuals who are said to have “high-functioning autism” (HFA) but this term can be very misleading. HFA is used to describe any individual with autism whose IQ is higher than 70, since this is the accepted point at which one is able to diagnose general learning difficulties (mental retardation) and average intelligence. In fact, an IQ of around 70 is still likely to lead to considerable educational problems.

It is often said, for example, that someone with an IQ of 70 would be unlikely to pass the exams required to complete mainstream secondaryschool education, or that someone with an IQ of much less than 100 would be unlikely to be selected for a place at a university.5 So an individual with an IQ of around 70 is only “high-functioning” relative to the other individuals with autism whose IQ is even lower than this, and who have clearly recognized learning difficulties or mental retardation. To discover that such individuals have some executive dysfunction may be no surprise, and may be linked to their relatively low IQ.

Indeed, if autism involves an intact or superior systemizing ability, and if systemizing requires an ability to predict that input X causes output Y in a system, then this suggests that those with autism are capable of some executive function (planning). Richard Borcherds, who we met in the last chapter, has terrific systemizing skills (when it comes to math), considerable difficulties in empathizing, but not a trace of any executive dysfunction. So it may be that executive dysfunction is not a necessary or universal feature of autism.

It is also said that people with autism have “central coherence” deficits, such that they spend more time processing local detail, rather than getting the larger picture. But if autism involves an intact or superior systemizing ability, then those with autism must be able to see the larger picture, at least where systems are involved. Input X may be quite distant from output Y, and yet they can keep track of these contingencies. Again, how are these two accounts related?6 Indeed, it may even be that good systemizing would resemble weak central coherence. Good systemizing would lead the individual to focus on one possible domain as a system, and that individual would start with very local details in case these turned out to be variables that followed laws. At the point when the individual had worked (systematically) through all the local details in that domain, that individual would end up with a good picture of the larger system, which is not what the weak-central-coherence theory would predict.

Are there facts about autism that are inconsistent with the extreme male brain theory? For example, if there is reduced lateralization for language in the left hemisphere of the autistic brain, as has been suggested by some studies, is this what would be expected of the extreme male brain? Further work is needed to understand the relationship between sex and laterality at the extremes.7

A potential criticism of the extreme male brain theory of autism is that the sex ratio of many conditions (not just autism) is biased toward males, so the account may lack specificity. For example, stuttering affects boys more than girls, and attention deficit with hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is also more common among boys. So is conduct disorder. Are we just witnessing some biological vulnerability among males that puts them at increased risk for everything going?

This is unlikely. There are some developmental conditions (such as anorexia, or teenage depression) that affect girls more often than boys. For this reason we need specific explanations for the sex ratios in each condition. Moreover, the sex ratio in Asperger Syndrome—estimated to occur in at least ten males for every female—far outnumbers the sex ratio seen in other developmental conditions (these are usually of the order of two or three males to every female). Note that the extreme male brain theory does not specify that the sex ratio in autism should be of a particular magnitude. It may be that the sex ratio in autism is lower than 10:1, but that females with AS get by more often without requiring a diagnosis because of better acting skills, or because they are more accepted by society.

It is also possible that there are important associations between the autism spectrum conditions and some of the other developmental conditions that affect males more often than they do females. Language delay and disorder may well involve a similar neurobiological mechanism to autism. Some genetic studies have already found that they may share an abnormality on the long arm of chromosome 7, though these results are very new and will need independent replication.8 Other studies have also shown that levels of pre-natal testosterone affect not only social development but also language development.9 Therefore, common mechanisms are a possibility. One must also take into account the fact that similar psychological processes may cut across different diagnoses. For example, reduced empathizing is not an exclusive feature of autism spectrum conditions but is also seen in conduct disorder. So far from the existence of these other conditions creating a problem for the model, they may actually help us understand things more clearly, and add new twists and complexity.

What empathizing and systemizing can explain

fig 12.

The attraction of the empathizing-systemizing model of autism is that it has the power to explain the cluster of symptoms seen in this condition (both the social and the non-social). The model can also make sense of some symptoms in autism that were previously neglected, such as repetitive behavior—also sometimes described as “purposeless”—for example, spinning a bottle over and over again. These relationships are shown in Figure 12.

The Nobel Prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman is said to have spent his afternoons during his Ph.D. in the university canteen spinning plates, but nobody described this as purposeless repetitive behavior. Feynman was behaving in a way that he couldn’t resist, like a spider that can’t help but spin a web. He was systemizing. Whether he did it on paper with equations or with a plate in the canteen, he was captivated and engrossed by the pattern of information—the laws, the regularities—that one can test and retest when one plays with variables systematically.

We should be wary of saying that a child with autism who shows echolalia (repeating everything you say in your exact intonation) or who plays a musical sequence over and over again, or who puts his eyes inches away from a spinning fan, is engaged in purposeless behavior. Such a child may be trying to systemize human behavior (speech) or mechanical motion, or auditory strings of input, at a level that is consistent with or higher than you would expect from their overall IQ.

A case in point is the art of Lisa Perini, an Italian artist who had classic autism as a child. As a five-year-old girl she filled every page with the identical, repetitive shape of the letter “W.” It was as if she had isolated this variable as a feature or input to the writing or drawing process. She then operated on this in a highly systematic way, varying only the angle of this shape, until she had mastered her motor control and achieved the pleasing effect she was striving for. Later she did the same thing with the repeating motif of flowers, producing thousands of superficially similar flowers, in reality each comprising a mini-experiment in manipulating one tiny variable. As an adult, her technical skill as an artist is outstanding, and she retains this systematic approach to creativity. Sabina Maffei, the Italian graphologist who introduced me to Lisa’s work, told me that if Lisa sees some broken red indicator-light glass from a car accident lying in the street she will pick up the pieces, study the shapes, and ask other people to send her similar fragments of colored glass that they might come across, so that she can find the perfect shapes for her art. Systemizing creatively.

The systemizing-empathizing model of autism can also encompass the “islets of ability” that previously were studied as if separate from the other aspects of autism itself. Calendrical calculation, or gifted drawing ability, or a facility to calculate prime numbers, or an excellent musical memory, was seen as an oddity that occurred in autism more often than in other conditions, but defied explanation. In the model presented in this book such islets of ability are simply well-developed examples of what all people with autism do without trying. They systemize.

The model can also explain the unusual attention to detail seen in autism. Why does the child notice those tiny numbers on the backs of lamp posts? Or remember the number of the seat in the theater they visited eight years ago? Or spot that an ornament on the mantlepiece has moved? Or that Auntie Becky has new earrings? Or that Mr. Hackett lives in house number 106? This unusual attention to detail is a prerequisite for good systemizing, and the brain in these examples is taking any feature and treating it as an anchor point, to see if this could be the basis of a new law or rule. Is seat H24 the same or different to seat H23 in this theater? Are the silver and red earrings a reliable way to recognize that this is Auntie Becky? Do the light bulbs in the lamp posts in our street tend to burn out in a particular order? Who else goes into house number 106, and since it is an even number, is it necessarily on the left-hand side of the street?

Finally, other models paint an essentially negative view of autism by concluding that the brains of those with autism suffer from executive dysfunction. It is true that damage to your frontal lobes can produce executive dysfunction, and that this is not uncommon in those individuals with autism who have a below-average IQ. Indeed, low IQ might even be a marker for such executive dysfunction. But a model of autism has to be able to explain not just those who have such pervasive problems but also those—like Richard Borcherds—who have reached supreme heights of achievement, despite their difficulties in empathy, with no trace of executive dysfunction. The empathizing-systemizing model bestows some dignity on those with the diagnosis of autism by identifying both their talents (at systemizing) as well as difficulties (in empathizing), suggesting that people on the autistic spectrum are simply different from others in their abilities. As one young man with AS said to me in Denmark:

People with AS are like salt-water fish who are forced to live in fresh water. We’re fine if you just put us into the right environment. When the person with AS and the environment match, the problems go away and we even thrive. When they don’t match, we seem disabled.

Keep the salt- and fresh-water metaphor in mind. I think it is very powerful.

Society’s Responsibilities:

To Intervene or Not to Intervene?

One upshot of this book might be that teachers need worry less about boys when it comes to the development of systemizing, and need worry less about girls when it comes to the development of empathizing. Rather, they could target their teaching on areas where each sex is likely to need more direction and support. This may come as welcome news to some readers, who might have assumed that if there is evidence that biology partly determines an individual’s profile, there is nothing teachers or parents can do to change that individual. Such a conclusion would be a mistake. In all likelihood, biology may be pushing an individual down one track in development, but there is plenty of evidence that the brain can be resculptured by experience.10 But should we really attempt intervention at all? Should society strive to make an average male more empathic, or an average female more focused on systemizing?

We should recall that although the sexes do differ, these individual differences in most people are at a level that do not cause either them or anyone else any distress. In which case, the grounds for any intervention are weak. Rather, the hope is that laying out what we understand about essential differences in the minds of men and women may lead to greater acceptance and respect of difference. Targeted teaching is, of course, still desirable, but this should always be based on an assessment of each individual’s strengths and weaknesses.

But then there is the specter of medical intervention, with all the ethical issues this raises. If autism is linked to high levels of fetal testosterone (and this has not yet been shown), would a form of estrogen therapy in the womb reduce the risks of autism? Or is there some other kind of pharmacological treatment that could mediate the effects of high testosterone? Certainly, as we saw in Chapter 8, a few less drops of this precious stuff can lead you to make more eye-contact and to have better communication abilities. But, ethically, would one really wish to intervene? To do so might be to lose what is special and valuable about the extreme male brain. As one person with autism put it in a recent email to me: “Without autism, we might not have fire and the wheel.” Certainly, if good systemizing leads to innovation, as we hinted at in Chapter 11, we might be losing something priceless if the medical profession tried to alter fetal brain development through biochemical treatment.

Issues relating to pre-natal screening for autism are unlikely to arise for a good while yet, as biological markers for autism have not yet been reliably demonstrated. All we have are clues. But even when such markers are available, it is likely that the autism community will be divided on the issue of prevention or intervention. Some will say:

If I could have been helped as an infant so that I could have had my autism taken away, I would have wanted that. My autism has been an enormous daily struggle.

These are the words of Ros Blackburn, a woman with autism who gives talks publicly about what it is like to live with the condition. Yet other people with the condition advocate the opposite view. A Web page asserts with dignity: http://groups.yahoo.com/group/AS-and-Proud-of-it.

Equally, parents of children with an autism spectrum condition, and who are at risk of having another child with autism for genetic reasons, may be divided on the issue. Some parents will (and do) say:

The idea of having to cope with another child with severe autism is just too much for us to bear. The difficult behavior, the lack of any acknowledgement, the disinterest in other people’s feelings, and the extremely limited life that autism has forced on the family is overwhelming. Since he was born, neither he nor we have had more than two hours of sleep a night. And the way he bites his own hand and hits his head against the wall is overwhelmingly distressing. If we were offered a cure, or if prevention had been available, we would have taken it.

Yet other parents, while acknowledging the difficulties, assert their child’s right to be different, and would not want to force them to be like everyone else. They admire their child’s independence of mind, their lack of conformity, their unusual intellect, and protect them fiercely from any suggestion that this should be medicalized, treated, or prevented.

Clearly, individuals with the condition, and their parents, deserve the freedom to make their own choices if and when the time comes for medical science to face these big societal decisions.

Misconceptions

I would weep with disappointment if a reader took home from this book the message that “all men have lower empathy” or “all women have lower systemizing skills.” Hopefully, I have made clear that when we talk about the female brain or the male brain, these terms are shorthand for psychological profiles based upon the average scores obtained when testing women as a group, or the average scores obtained when testing men as a group.

Such group statistics say nothing about individuals. I am fortunate enough in my research group at Cambridge University to work with women who have far more systemizing skill than I will ever have, and as a result they do wonderful science. Equally, I am fortunate enough to have some male friends who go against the norm, and have what we have been calling the female brain. It may be no coincidence that they work in the caring professions, and their clients appreciate how emotionally connected they are to their needs. However, the model in the book still stands: in order to explain why these particular women have a gift for systemizing, or why these particular men are talented at empathizing, we must refer to their particular biology and experience.

Some may think that the small but real differences between men and women (on average) mean that there is never going to be any hope for relationships working well. Again, I think this worry is overstated. In the majority of opposite-sex couples or friendships, there is sufficiently good communication to enable people not only to understand each other but also to respect each other’s differences. And, after all, the age-old solution to the need for a like-minded companion has always been to have same-sex friends outside of any primary relationship involving someone of the opposite sex. A girls’ night out, or a night out with the guys, has always been a need for most people.

Some may worry that the view of the male and female brain offered in this book risks portraying the male brain as more intelligent than the female brain. Systemizing sounds like the sort of thing that might come in useful on an IQ test, while empathizing may not figure in such a test at all. I do not think this risk is real, however, because both processes give rise to different patterns of “intelligence.” Systemizing may be useful for parts of the non-verbal (“performance”) IQ test, while empathizing might be useful for the more verbal aspects of the IQ test.

Some may worry that portraying autism as hyper-male will trigger associations of people with autism as super-macho. Again, this would be a misconception, as machismo does not overlap with any exactness with the dimensions of empathizing and systemizing. Indeed, the negative connotations of being macho, such as aggression, are far from a good characterization of many people with autism spectrum conditions. Aggression is determined by many factors, and reduced empathy may be just one of them. And even then, reduced empathy does not invariably lead to aggression. It may not even lead to this in the majority of cases. Many people with autism spectrum conditions are gentle, kind people, who are struggling to fit in socially and care passionately about social justice: not the stereotype of a macho male at all.

Respect

When we find someone with the extreme female brain, my guess is that we will also find that society has made it easy for them to find a niche and a value, without that person having to feel that they must in some way hide their systemblindness. I hope that at least one benefit of this book is that society might become more accepting of essential sex differences in the mind, and make it easier for someone with the extreme male brain to find their niche and for us to acknowledge their value. They should not feel the need to hide their mindblindness (as many currently do).11

A central tenet of this book is that the male and female brain differ from each other, but that overall one is not better or worse than the other. Hopefully, in reading this book, men will also experience a resurgence of pride at the things they can do well, things like being able to work out confidently how to program a new appliance in the home, being able quickly to discover how to use a new piece of software, or how to fix something with whatever available tools and materials are around. All these need good systemizing skills.

Society needs both of the main brain types. People with the female brain make the most wonderful counselors, primary-school teachers, nurses, carers, therapists, social workers, mediators, group facilitators, or personnel staff. Each of these professions requires excellent empathizing skills. People with the male brain make the most wonderful scientists, engineers, mechanics, technicians, musicians, architects, electricians, plumbers, taxonomists, catalogists, bankers, toolmakers, programmers, or even lawyers. Each of these professions requires excellent systemizing skills. (People with low systemizing but good empathizing could apply for the public relations and communication aspects of these jobs.) And people with the balanced brain make the most wonderful medical doctors, as comfortable with the details of the biological system as with the feelings of the patient. Or they can be skilled as communicators of science, not just understanding systems but being able to describe them to others in ways that do not presume the same degree of knowledge—that is, adapting language to the needs of the listener. People with the balanced brain can be excellent architects if they not only understand buildings but also understand their client’s feelings, and the needs and feelings of the people who will be inhabiting the space they are designing. Or talented company directors, grasping the mathematical details of economics and financial planning while building a strong team around them based on their sensitive way of including each and every individual in the team.

Society at present is likely to be biased toward accepting the extreme female brain and stigmatizes the extreme male brain. Fortunately, the modern age of electronics, science, engineering, and gadgets means that there are more openings now for the extreme male brain to flourish and be valued. My hope is that the stigmatizing will soon be history.