2.3 Market Demand: What the Market Wants

We’ve focused so far on the buying decisions of individuals. Now it’s time to pan back and take a broad view, analyzing market demand—the purchasing decisions of all buyers taken as a whole. As a manager, you’ll find this broad view useful because it’s total market demand that tells you how much business is up for grabs. And of course, it’s not just businesses that need to know market demand: Nonprofits seeking donations, universities seeking applicants, and YouTube wanna-be stars seeking subscribers all benefit from being able to estimate market demand for what they’re selling. In each case, you’re interested in assessing the total quantity demanded—across all people—at each price. The market demand curve provides exactly this information: It plots the total quantity of a good demanded by the market (that is, across all potential buyers), at each price.

From Individual Demand to Market Demand

Let’s explore how real-world managers estimate the market demand curve for their products. As we’ll see, individual demand curves are the building blocks of market demand.

Market demand is the sum of the quantity demanded by each person.

For each price, the market demand curve illustrates the total quantity demanded by the market. This means you’ll need to figure out the total quantity demanded when the price is $1, then $2, then $3, and so on. At each specific price, the total quantity of gas demanded is simply the sum of the quantity that each potential consumer will demand at that price.

Managers use survey data to figure out their market demand curves.

One way to get this information is to survey your potential customers. In fact, there’s a simple four-step process that many managers follow to estimate the market demand curve for their products.

Step one: Survey your customers, asking each person the quantity they will buy at each price.

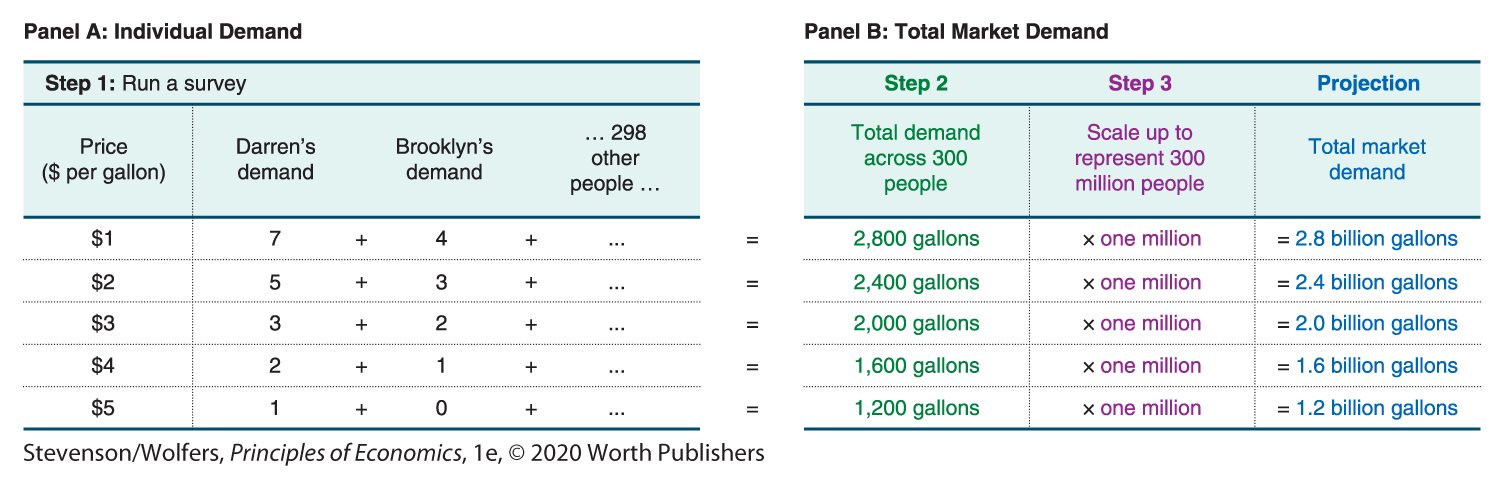

When Darren was surveyed about his gas-purchasing behavior (in Figure 1), it was as part of a broader survey that was sent to a representative sample of 300 potential customers, asking each of them about the quantity of gas they plan to buy at each price. Their responses are shown in Panel A, on the left of Figure 6, with each person’s response shown in a different column. I’ve only shown you the responses of the first two people to respond—Darren and Brooklyn—but in the full spreadsheet, there are another 298 columns.

Figure 6 | From Individual Demand to Total Market Demand

Step two: For each price, add up the total quantity demanded by your customers.

For each price, you should add up the quantity demanded by each person in the survey. The top row shows that when the price is $1 per gallon, Darren demands 7 gallons, Brooklyn demands 4 gallons, and you also need to add up the quantities demanded by each of the other 298 potential customers who were surveyed. This is calculated on the full spreadsheet, and it adds up to 2,800 gallons.

I repeated these calculations for each price from $1 to $5—once for each row—and the results are shown in the first column of Panel B, presented on the right of Figure 5. This is where you can see that at a price of $1 per gallon, the survey respondents would collectively buy 2,800 gallons of gas, and at $2 per gallon, this would fall to 2,400 gallons.

Step three: Scale up the quantities demanded by the survey respondents so that they represent the whole market.

If the total market for gas consisted of just the 300 people we surveyed, then these numbers would represent the market demand. But in reality, there are around 300 million potential customers in the United States. The idea of market research is that our survey of 300 people is intended to be representative of those 300 million potential customers. This means that the total quantity demanded by the entire population will be one million times larger than the total quantity demanded by the 300 survey respondents. Thus, you need to scale up the quantities so that they represent the whole market. (This works well if the 300 people in your survey are representative of the broader population of 300 million Americans.)

In practice, this means that when the price of gas is $1 per gallon, and the 300 people surveyed collectively say that they would buy a total of 2,800 gallons of gas, you can project that the entire market of 300 million consumers would buy 2,800 million gallons of gas (that is, 2.8 billion gallons) per week. Consequently, the projected market demand at each price, shown in the final column of Figure 6, is one million times the total quantity demanded by our survey respondents.

The market demand curve plots the total quantity demanded by the market at each price.

Okay, now that we’ve figured out the total quantity demanded by the market, at each price, all that remains is to draw the market demand curve.

Step four: Plot the total quantity demanded by the market at each price, yielding the market demand curve.

The graphing conventions for market demand curves are the same as when graphing individual demand curves: Price is on the vertical axis, and quantity on the horizontal axis. For each price listed in the first column in Figure 6, you plot the corresponding total quantity demanded by the market, which is listed in the last column. Each row in the table is represented by a purple dot in Figure 7. We then connect these dots to arrive at our estimate of the market demand curve for gasoline in the United States. In fact, this figure is quite similar to the statistical estimates of demand curves that major gasoline executives actually rely on.

Figure 7 | Estimating Market Demand