13.4 The Debate About Income Redistribution

Given everything you’ve read so far, do you think that the government needs to do more redistribution to combat inequality and poverty, or do you think that it redistributes too much? This question is at the root of many of our fiercest political debates, and it separates left-wing or liberal politicians, who typically advocate more redistribution, from right-wing or conservative politicians, who usually advocate less.

The Economic Logic of Redistribution

Let’s begin with the simple logic of redistribution, and explore how it can raise total benefits, or well-being. Money is a means to an end, so when we consider whether redistribution of money is a good idea, it’s useful to ask how money affects people’s well-being. Economists refer to your level of well-being as your utility. The marginal principle reminds you to think at the margin, and the idea of diminishing marginal benefit also applies to money. That is, your 50,000th dollar—which you might use to pay for entertainment—yields a smaller boost to your utility than your 10,000th dollar—which you will likely spend on food or shelter. To be precise, marginal utility is the boost to utility you get from an extra dollar. And because each additional dollar yields a smaller boost to your well-being, you have diminishing marginal utility. This means that your marginal utility may be large when you are poor, but it gets smaller as you get richer.

To be concrete, consider Alison Stine, a single mother in Ohio who struggles to pay for her and her son’s allergy and asthma medicine. If she had another $100 she could afford to purchase another asthma inhaler. Now imagine instead what billionaire Michael Jordan might do with an extra $100. He likes fine cigars, so perhaps he’ll buy another $100 cigar. Who do you think has higher marginal utility from the extra $100?

Who would benefit the most from an extra $100? Billionaire Michael Jordan? Or this family?

Redistribution can increase total well-being.

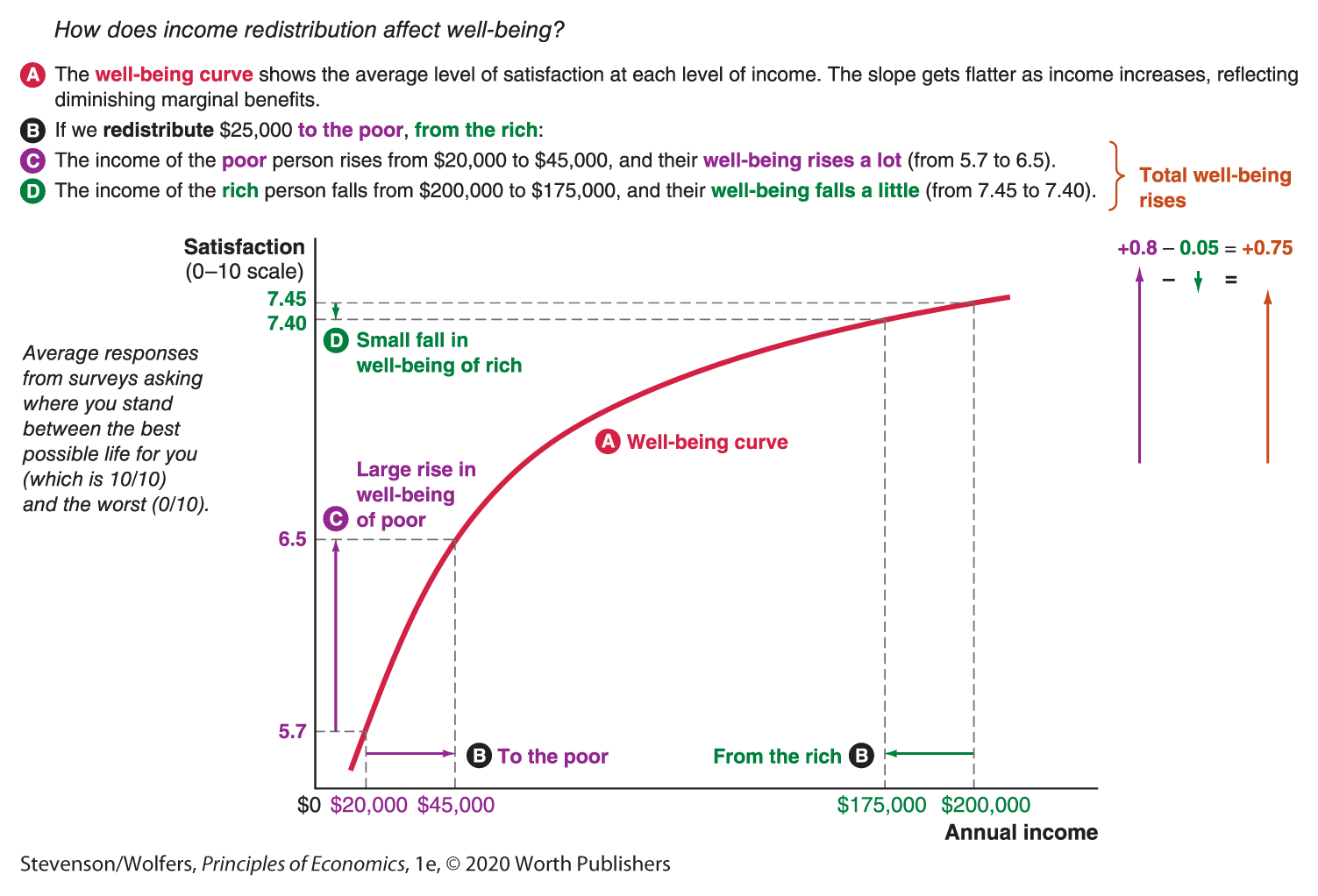

To find out the role of money in shaping well-being, researchers have asked thousands of Americans to rate their well-being on a 0–10 scale. Figure 14 shows a line of best fit illustrating the average level of well-being reported (on the vertical axis) at each level of income (on the horizontal axis). The fact that the line is upward-sloping shows that people with more income are happier than those with less income. More importantly, focus on the slope of this curve. The slope illustrates the change in well-being associated with a change in income—the extra benefit from extra income. This curve flattens out as income rises—the slope gets smaller and smaller—which means that the extra benefit of an extra dollar is higher the poorer you are (the slope is larger at low incomes but is smaller at high incomes). That is, these data illustrate a pattern of diminishing marginal benefit from extra dollars.

Figure 14 | Income and Well-Being

Now that we’ve measured the extent of diminishing marginal benefits, we can use Figure 14 to analyze the gains from redistribution. Consider someone in the top fifth of the income distribution earning $200,000, and someone from the bottom fifth, earning $20,000. The well-being curve suggests that we might expect their well-being scores to be 7.45 and 5.7 respectively, which adds up to 13.15. If you redistribute $25,000 from the high-income person to the low-income person, the well-being of the high-income person will fall by 0.05, while the well-being of the low-income person will rise by 0.8. Consequently, this redistribution causes total well-being to rise by 0.75 (from 13.15 to 6.5 + 7.4 = 13.9).

The idea of maximizing total well-being comes from utilitarianism.

The political philosophy that government should try to maximize total utility in society is known as utilitarianism. This belief holds that government redistribution is beneficial because transferring $100 from someone with a lot of resources—like Michael Jordan—to someone with fewer resources—like Alison Stine—will lead to a society with a higher level of well-being, or utility. That gain arises because taxing $100 of Michael Jordan’s income reduces his utility by only a little compared to the utility gain that Alison Stine would enjoy from receiving that $100. As such, government can raise total utility by redistributing resources from the rich to the poor.

The Costs of Redistribution: The Leaky Bucket

Even if you consider yourself a utilitarian you face a problem: There’s no easy way to redistribute money from the rich to the poor. Redistribution can be like moving money using a leaky bucket—some of the money gets lost along the way. Let’s turn to examining the costs of redistribution to see why some of the money gets lost.

A leaky bucket makes redistribution less effective.

Administrative costs subtract from what you can redistribute.

The first cost is the bucket itself. There’s overhead involved in running social insurance and safety net programs. New applications for benefits must be processed; auditors make sure that no improper payments are made; policies must be enforced; and payments must be made. All of this is done by government workers, who must be paid. While these administrative costs are the most obvious financial costs of redistribution programs, they’re relatively small. As we’ll see in a moment, the more important costs arise from how the social safety net distorts work incentives.

Taxes and means-tested programs reduce the incentive to work.

Some of the leakage is actually money lost before it is even collected. The problem is that we raise the money to pay for redistribution through income taxes. As you learned in Chapter 11, higher income taxes reduce the rewards from working. When you get a smaller reward for working, you might choose to work less. That’s why when the government tries to redistribute money by taxing high earners, those high earners might respond by working less, leaving less money available to be redistributed.

The presence of a leaky bucket also reduces the incentive to work. The opportunity cost principle reminds you that an important cost of working is what you must give up in order to work. All of us give up time to work: Your opportunity cost of work is the benefits you get from whatever you would be doing instead—studying, hanging out with friends, taking care of kids or someone else who needs care. The benefit of work is the wage you earn from working. The safety net means that when you work, the relevant opportunity cost is not only your time, but also the potential that you might lose cash or in-kind benefits. If you use the cost-benefit principle to decide whether to take a job, the presence of the safety net will make you more likely to turn down a job.

The safety net can also reduce the incentives for people to seek higher paying work. The problem comes from the fact that means-tested benefits are taken away from people as they earn more. That means that recipients not only pay taxes from every extra dollar earned, but they also lose benefits. The sum of higher taxes and reduced benefits accruing from each dollar you earn is called your effective marginal tax rate. As the following example shows, those with low incomes can face such high effective marginal tax rates that even though they are earning more through work, their living standards hardly improve at all.

EVERYDAY Economics

When earning extra money doesn’t pay off

One economist tells the story of meeting a low-income woman who taught him about the problems of high effective marginal tax rates:

She had moved from a $25,000 a year job to a $35,000 a year job, and suddenly she couldn’t make ends meet any more. She showed me all her pay stubs. She really did come out behind by several hundred dollars a month. She lost free health insurance and instead had to pay $230 a month for her employer-provided health insurance. Her rent associated with her Section 8 voucher [housing assistance] went up by 30% of the income gain (which is the rule). She lost the ($280 a month) subsidized child-care voucher she had for after-school care for her child. She lost around $1,600 a year of the EITC. She paid payroll tax on the additional income. Finally, the new job was in Boston, and she lived in a suburb. So now she has $300 a month of additional gas and parking charges.

This woman lost more than $10,000 in benefits by earning $10,000 more! With her payroll taxes also added in, her effective marginal tax rate was well above 100%. The fact that she was better off earning $25,000 a year than $35,000 is known as a poverty trap. It’s a trap because neither earning a higher nor a lower income will improve her situation by much.

Higher taxes mean more tax avoidance, tax evasion, and fraud.

Because safety net payments are based on your income, there’s an incentive to try to make your income appear as low as possible. Likewise, the higher taxes required to fund redistribution provide a strong incentive to engage in complicated accounting tricks to lower your tax bill. These incentives lead to both legal but wasteful tax avoidance (doing things explicitly to try to reduce the taxes you owe by taking advantage of loopholes in the tax system), and illegal tax evasion (which means not honestly reporting all your income, such as being paid “off the books” and not reporting the income to the IRS). When benefits are available only to particular groups, this creates further incentives for wasteful and fraudulent behavior, such as searching for a doctor willing to classify you as unable to work, or claiming benefits for your kids who actually live with an ex-spouse. To continue the leaky bucket analogy, the problem isn’t just that the bucket leaks, it’s that some people are actively trying to punch holes in it.

How leaky is the bucket?

Okay, so we’ve surveyed four different ways in which redistribution programs are costly. The first—administrative costs—is fairly small. The remaining three costs are more important. And they are all linked by a common theme—they arise because redistribution distorts incentives. The more that people respond to these incentives, the greater the cost of redistribution. Thus much of the debate about redistribution is between those who believe the costs are high because people are strongly influenced by these financial incentives, and those who believe that the costs are low because people only respond a little to these incentives.

The Trade-Off Between Efficiency and Equality

Let’s take stock. Efforts to equalize the distribution of income may help put dollars in the hands of those who value the dollars most, which raises total well-being. But tax and redistribution programs are costly because they distort incentives, thereby reducing work effort. As such, more equal incomes may come at the cost of lower average incomes. Economists refer to this as the equality-efficiency trade-off.

To understand the trade-offs, consider the extremes.

What would happen if the government redistributed until we all got the same income no matter what? There would be no incentive to work hard, start a new business, or even bother to work since none of your efforts would be rewarded with a higher income. As a result, total production in the economy would plummet. Ultimately we would all be entitled to an equal-sized slice of a pretty small pie.

Would you choose a bigger pie? Or more equal slices?

At the other extreme, imagine a world with no income redistribution. With no safety net programs to finance, taxes would fall, increasing your incentive to work hard, invest, and start new businesses. The size of the pie may grow, but with no redistribution, many of those who are sick, disabled, elderly, or unemployed would be destitute. A larger pie is little solace to those surviving on the crumbs.

So extreme efficiency comes at a cost of terrible inequality, while perfect equality comes at a cost of terrible inefficiency. In reality, no one thinks either extreme makes sense. Instead, our political debates are typically about how much pie to trade off in order to give everyone a fairer share.

Greater equality doesn’t always mean less efficiency.

But this trade-off isn’t a hard and fast rule, and there are cases where there’s no efficiency cost to increasing equality. For instance, studies show that societies with greater income inequality typically exhibit less trust, tolerance, and community involvement and more crime. The resulting violence and political unrest can be costly to manage, diverting resources to policy, prisons, security systems, and other unproductive pursuits.

Income inequality also concentrates political power, which can lead to policies that further increase inequality, such as tax cuts for the rich. These forces may make it difficult for the government to make good policy, by undermining public support for public investment in education, infrastructure, and a clean environment. These adverse outcomes may ultimately lead to weaker economic growth.

There are also instances where social benefits can encourage greater long-term investment among individuals. For instance, paid maternity leave has been shown to increase women’s labor force participation. Closing racial gaps in learning may increase long-term economic growth by encouraging further investment in education among a wider group of people. More generally, government investment in both early childhood education and education through college increases worker productivity.

Okay, while it is possible in some cases to make our economy both more equal and more efficient, these cases present the easy choices. But after we exhaust these easy choices, we’ll then be stuck with the difficult trade-offs. How do you feel about these trade-offs?

Do the Economics

Let’s return to our earlier thought experiment to help you sort out your views about income inequality. Recall that in Figure 14 we evaluated a policy that redistributed $25,000 from each family in the top quintile (earning $200,000) to a family in the bottom quintile (who earned only $20,000). But we didn’t account for the leaky bucket. In reality, poor families will receive less than $25,000, and so greater equality comes at a cost.

- Suppose that 20% leaks out; this would leave a $20,000 grant to the poor families. Do you think society as a whole would be better off?

- What if 40% leaks out, so each poor family receives only an extra $15,000?

- What if 60% leaks out, so each poor family receives only an extra $10,000?

- What if 80% leaks out? Does an extra $5,000 benefit a poor family more than $25,000 benefits a rich family?

- Where would you draw the line?

It’s an interesting thought experiment. If you were to follow the utilitarian logic of maximizing total well-being as in Figure 14, even 90% leakage would increase total utility in society. What’s your answer? Compare the answer you gave with that of your friends, and it will give you a sense of just how different people’s views are about inequality.

Fairness and Redistribution

As much as economists debate things in terms of total costs and benefits, the debate about redistribution is also a debate about fairness. In fact, economists often talk about the trade-off between equity—what’s fair or just—and efficiency. But that debate requires settling on a notion of fairness and there are many competing notions of fairness. Your sense of fairness is likely shaped by many different intuitions. It’s important to understand these intuitions, because they guide the real-life decisions that you confront every day. As we investigate these different ideas, try to recognize how each of them shapes your own choices. Bear in mind that these different ideas can coexist and each may be important to you, to a greater or lesser degree, or in some settings more than others.

Is fairness about equality of outcomes?

Are they offering you a fair share?

One common belief is that more equal outcomes are fairer. The following simple experiment demonstrates this. Imagine that I give your friend $10, and I tell them to split it with you in whatever way they see fit. But there’s one condition: If you don’t agree to the deal they offer, neither of you will get anything. What will you do if they offer you only $1? Go ahead, and think about it before reading the next paragraph. Have you decided how to respond? Okay, read on.

Your accountant would urge you to accept the offer of $1—after all, it’s more than the $0 you’ll get if you reject the offer. But if you’re like most people, you will reject the offer. Experiments repeatedly show that many people reject offers that are below what they regard as a fair share. For most people this idea of fairness is so important that they’ll give up what they view as a too small share, rather than accept an an outcome they regard as too unequal. What about you? Would you accept $1? $2? $3? The higher your cut-off, the greater is your willingness-to-pay for fairness. The same reasoning you use in this experiment might lead you to advocate for policies that redistribute income to the poor.

Is fairness about equality of opportunity?

An alternative view of fairness emphasizes equality of opportunity, rather than equality of outcomes. The basic idea is that fairness requires a level playing field that ensures that people with the same native talents and ambition can compete on equal terms for higher incomes. Consequently, fairness requires eliminating discrimination on the basis of race, gender, or ethnicity. It also requires ensuring that children from low-income families and disadvantaged communities can compete on equal terms with children whose families provide them with private schools, tutors, and family connections. Typically, this requires redistributing resources—such as through support of public schools—to ensure that all kids get a fair shot.

Is fairness about the process?

Your sense of fairness may also depend on how fair you find the process by which inequalities are generated. For instance, think about grading. Most students argue that if the process is fair—the exams are clear, the grading is consistent, and no one cheats—then it’s fair that those who did well earn higher grades than those who didn’t. These differences are okay when they are the result of a fair process. If you have this sense of fairness, you may think that income differences are okay, unless an unfair process—such as when someone gets rich by stealing—generates them.

Is fairness about what you deserve?

Some people think of fairness in terms of what you deserve, or what you contribute to society. Unfortunately, the most highly-rewarded people are not always the most deserving. For instance, let’s consider the stories of two millionaires. Paris Hilton is a high school dropout with a criminal record. She’s rich, because her great-grandfather founded Hilton hotels, and she inherited some of that wealth.

Is Paris Hilton a deserving millionaire?

What about Alexa von Tobel?

By contrast, Alexa von Tobel took a very different path to financial success. After graduating from Harvard in 2006, she worked in investment banking for two years, working long hours. While in business school she won a prestigious business plan competition for young entrepreneurs. Her idea was a website to provide personal finance advice targeted at young women. She invested her savings in founding her new firm, and put in long hours. She still works long hours, but she’s now CEO of a successful startup called LearnVest.

Do both Paris Hilton and Alexa von Tobel “deserve” their riches in equal measure? The big difference between them is the role of luck versus hard work in determining their success. If Paris Hilton is representative of those with a lot of money, how much should we redistribute from the rich to the poor? Would you feel differently if Alexa von Tobel were more representative of those with a lot of money?

Interpreting the DATA

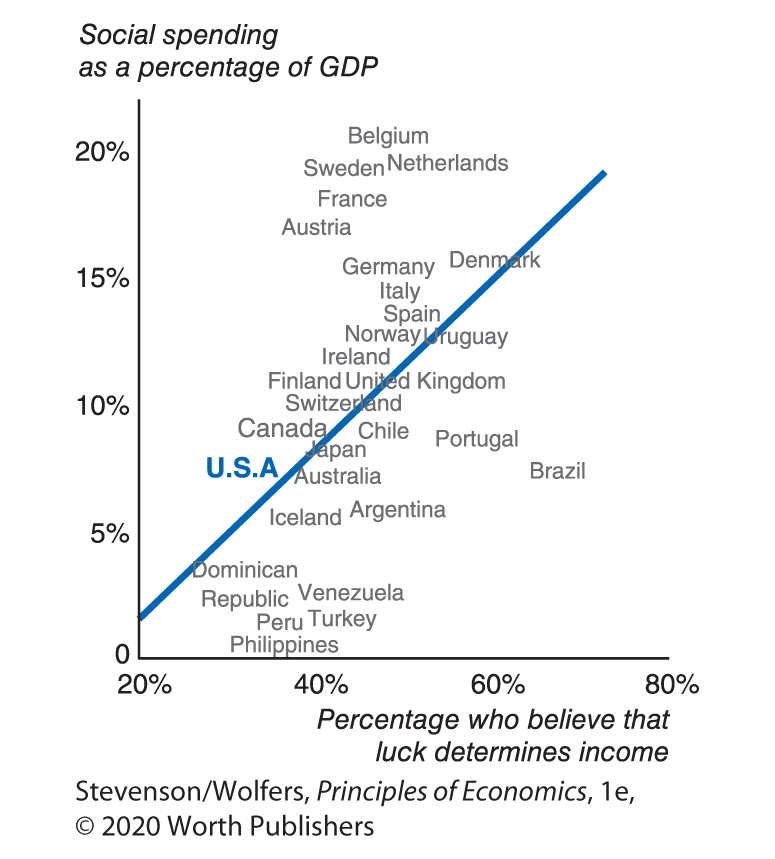

What explains differences in social spending?

In most developed countries a large share of the population believes that luck plays an important role in determining income. In comparison in the United States less than 40% of the population holds that belief and Americans are more likely to attribute success to hard work. As shown in Figure 15, researchers have found a clear relationship between social spending and the proportion of the population that believes that luck determines income. The more people believe in luck, the more the country tends to redistribute.

Figure 15 | Beliefs Determine Social Spending

Data from: Alberto Alesina and George-Marios Angeletos (2005), “Fairness and Redistribution.”

Is fairness best judged behind the veil of ignorance?

There’s no telling what your circumstances will be.

As remarkable as Alexa von Tobel’s success is, perhaps it is due to a different kind of luck. She was lucky to be born with intelligence, drive, and entrepreneurial spirit; to be born into a family and community who helped her develop those talents; and in a time and place where her particular skills are highly rewarded. Without this luck, she might be a poor beggar in Mumbai; a struggling single mom in Fargo; or a nomadic tribesman in Africa. The billionaire investor Warren Buffet describes this type of luck as “winning the ovarian lottery.” Buffett says his great wealth is due to his luck in being born not just a financial whiz, but also a male, in a supportive family that developed those skills, and in a society that rewards them.

Before you are born, you haven’t done anything to deserve a good or a bad life, and indeed, you don’t know what life circumstances you’ll be born into. If you could choose, many of you would choose to be born with fortunate circumstances. But you don’t get to choose. One way to think about whether society should be more or less equal is to ignore the circumstances you happen to have been born into. Instead, ask yourself what you would want if you didn’t know what circumstances you would be born into, what philosophers call behind the “veil of ignorance.” It’s a powerful way of thinking clearly about what makes for a just society. Behind the “veil of ignorance,” what kind of redistribution would you choose?

Is fairness about power and class differences?

While economists tend to focus on individuals, sociologists broaden the lens to consider class and group structures. This permits them to analyze how “power” may reside in particular groups, and how inequalities in the distribution of power both cause and result from income inequality. By this view the upper class—the wealthy, the well-connected, those in positions of power—have a lot of control over the political process, and they use this to further their own interests. Even if you don’t buy this argument, the deeper point is that your choices and your sense of fairness are likely shaped by your identification with your socioeconomic class, your race, ethnicity, religion, gender, or where you are from.

Okay, so of these different perspectives on fairness, which are “right” or “wrong”? Unfortunately, there’s no simple answer, and philosophers and others still debate these issues. So it’s up to you to decide how much emphasis to put on different notions of fairness.