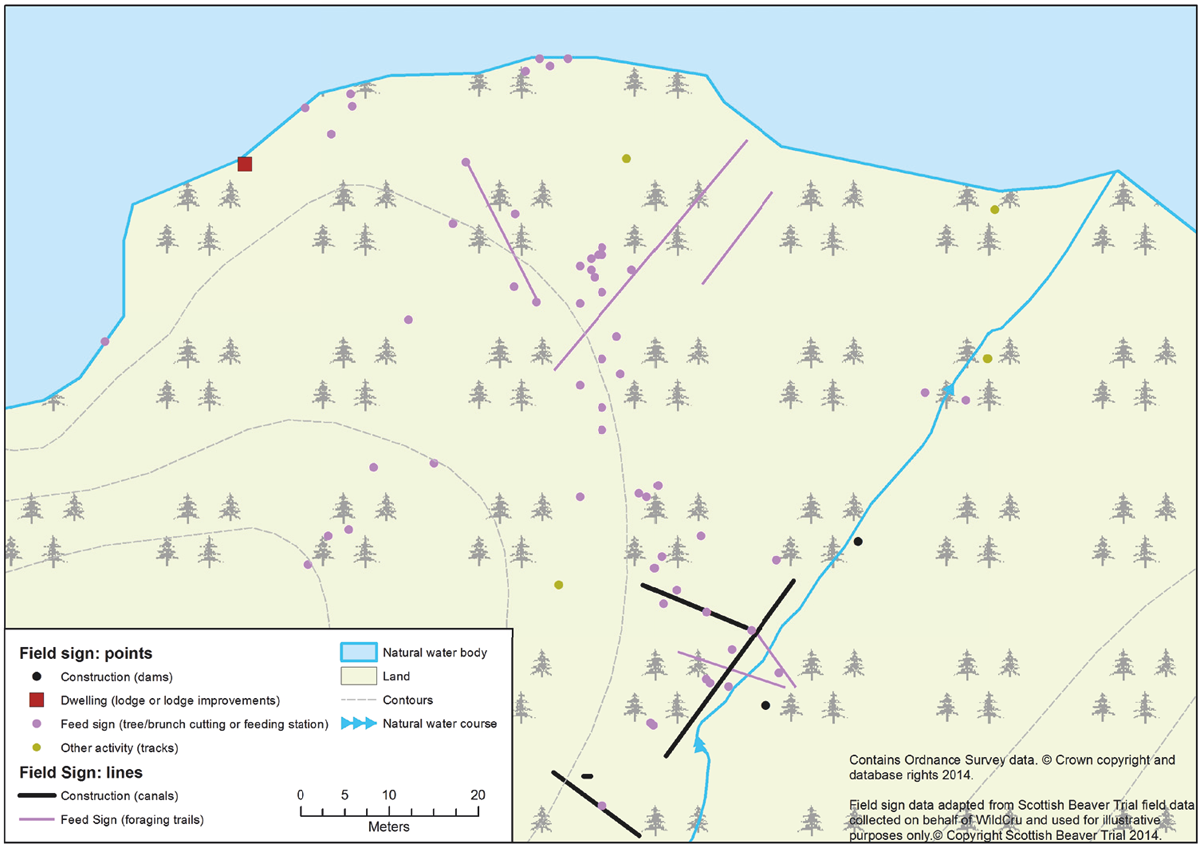

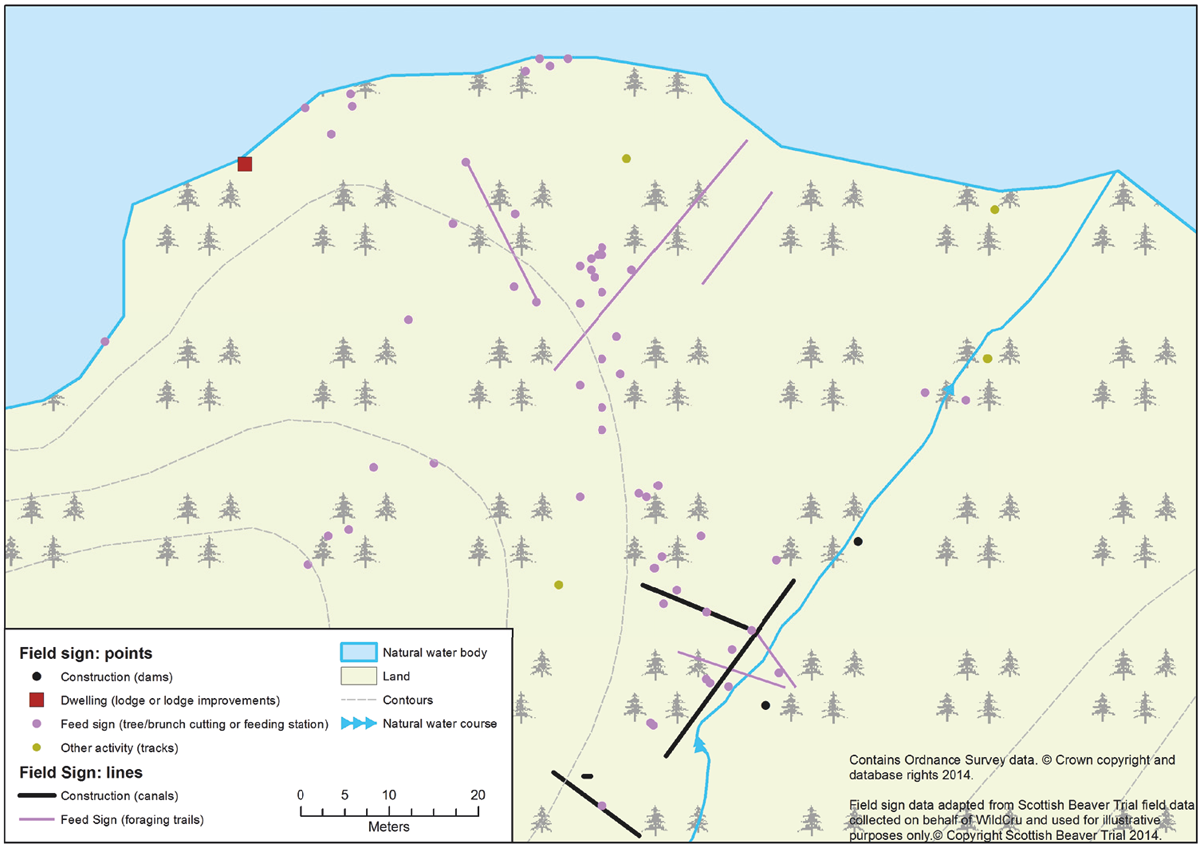

Figure 7.1 GIS mapping of beaver field signs to monitor habitat use and activity type. (K. Hill)

Beaver surveys will vary according to their objectives, resources and employed methodologies. While a simple survey might be appropriate at a local level to determine whether beavers are present or absent, more extensive studies will be required to determine their status on a landscape scale. Repeating standard surveys at regular intervals can identify changes in abundance, distribution and the effects of any applied management strategies. While regular visual observations of beavers can be undertaken on bodies of open water, their various field signs are uniquely distinct. With experience, their freshness can be readily assessed.

More detailed population or individual surveys can also be undertaken using live capture traps. The trapping and handling of beavers requires specialist knowledge, training and equipment (Campbell-Palmer and Rosell 2013). Trapping in Britain currently must be undertaken with the prior permission of the landowners and cannot proceed without an appropriate licence from the relevant Statutory Nature Conservation Organisations. Live trapping affords the opportunity for mark-and-release monitoring, as well as sample collection for health or genetic studies (Campbell-Palmer et al. 2014). Individual tags, biologgers or biotelemetry devices can be attached to study beaver movements and to assess territorial sizes, habitat use, and behavioural and social interactions (e.g. Campbell et al. 2005; Graf et al. 2015).

7.1 Non-invasive monitoring techniques

Several non-invasive techniques can be used to monitor beaver presence. These include carrying out a simple questionnaire survey of landowners and stakeholders in the area. Statutory organisations may also hold publicly accessible records. Aerial surveys using small planes or helicopters have been used to identify potential areas of beaver activity. For example, SNH undertook an aerial survey within the River Tay and River Earn catchments to identify potential beaver-occupied areas which were then subject to further detailed surveying on foot and by canoe (Campbell et al. 2012a). The use of drones is also becoming increasingly common. These surveys have revealed that it is possible to identify areas of beaver-felled trees from the air, while other large structures, such as ponds and dams, are also likely to be seen, though lodges may prove more difficult to identify from the air and require further foot- or water-based surveying, especially at times of year with high vegetation cover.

As beavers leave clear physical signs of their presence, the most straightforward way to survey is to look for field signs (see Appendix A) of beaver activity on foot or by canoe. Direct visual observation or using camera traps may be useful to confirm the presence of beavers as well to enable behavioural data to be collected (Rosell et al. 2006).

7.2 Habitat suitability/habitat-use survey

Consulting Ordnance Survey or electronic maps is an essential component for planning any survey. As more information becomes available regarding beavers’ distribution, mapping data from previous surveys can be utilised to complement larger-scale projects. Beaver surveys may be appropriate in any water’s-edge environment where vegetation is readily available. While most can be undertaken on foot along navigable watercourses, surveys may be carried out from an open canoe or small boat. An important consideration for the planners of surveys is an assessment of hazards and risks, and it is advisable to complete an appropriate risk assessment (see Appendix C for an example). The basic field equipment needed to carry out a survey for field signs of beaver activity should include:

•Hand-held GPS

•Camera

•Maps

•Notebook/field sheet/field-sign mapping device

•Guide to field signs (see Appendix A)

•Binoculars

•First-aid kit and mobile phone

Although surveys can be carried out at any time of the year, beaver field signs are commonly obscured by vegetation in the summer months. The beavers’ seasonal preference at this time for vascular plants rather than more obvious woody vegetation also makes evidence of their presence harder to detect. Snow may conceal field-signs and beaver activity can be reduced in winter. For these reasons, field-sign surveys are best undertaken in early spring or autumn.

While most signs of beaver activity are generally found within 10–20 m from the water’s edge, some foraging trails or canals may lead inland away from the main water body (distances of 30–40 m are not uncommon, depending on habitat). These features should be followed, and often lead to clusters of further field-sign activity. Surveys are best undertaken in a systematic fashion by following the edge of waterways looking for signs, and investigating any subsidiary trails leading out into the wider environment. For a variety of reasons, some stretches of watercourse may be inaccessible, and their location should be identified for future reference. Photographs and descriptions of beaver field signs are shown in Appendix A.

When a sign of beaver activity is discovered, the following information could be recorded:

•Date

•Type of field sign/activity

•GPS coordinates

•Photograph/sketch

•Age of sign (a subjective assessment of whether it is old or recent)

•Area of sign and distance from water

•Width of river/stream and approximate depth (metres)

Figure 7.1 GIS mapping of beaver field signs to monitor habitat use and activity type. (K. Hill)

By plotting field signs, habitat-use maps can be created which may show seasonal variation and distribution spread over time. The type and abundance of vegetation can provide an indication of food availability. By looking at habitat use in relation to topography and nearby land-use practices, current and potential beaver impacts on the physical environment may be assessed. The River Habitat Survey (http://www.riverhabitatsurvey.org/rhs-doc/the-survey/) provides a standardised method for collecting this type of information along a set length of river of 500 m. In-stream and margin features are recorded, including channel dimensions, sediment size, river bed and bank form, features and vegetation content and morphology. Specific features of relevance to beavers include the extent of trees, shrubs and dead wood (Environment Agency 2003).

Particular field signs, such as the presence of scent mounds along territorial boundaries can be a useful clue to identify different territories and therefore family groups (Rosell and Nolet 1997; Rosell et al. 1998). In addition, lodges are robust features which remain visible in the environment long after they have been abandoned by beavers. As such, they should not be presumed always to indicate current beaver presence without evidence of fresh activity. It should be noted that beaver families often have more than one lodge in their territory. During autumn and winter, the presence of a food cache, the top of which is often visible from the bank, is a good indication that the lodge is currently in use and should be observed for new kits the following summer. These food caches are located directly in front if an active lodge or burrow.

7.3 Monitoring beaver population size and development

Precise counts of beavers for monitoring and management purposes are difficult to obtain (Rosell et al. 2006), with the most accurate determination of family size and composition being achieved through removal trapping (Hay 1958) and/or mark–recapture observations (Busher et al. 1983). Both methods require significant resource investment and effort. Signs of previous beaver activity remain visible for many years, and it is therefore possible during an autumn census to map both presently and previously occupied sites (Parker et al. 2002a), leading to a potential overestimate of abundance. If the location of a beaver lodge is known, sitting and watching quietly with binoculars from the opposite bank is one of the most effective ways of seeing beavers. Observation of beaver lodges to count family size and assign individuals to age classes (bank counts) can produce data representative of actual lodge occupancies (McTaggart and Nelson 2003). However, many factors, including the weather, the number of watches, the time and season at which observations are undertaken, and the experience of observer, can affect results, so should be viewed with caution (Rosell et al. 2006). It is very rare for all family members to be observed simultaneously, and it can be difficult to count them in sequence as they leave or enter the lodge. As a management technique for large areas, e. g. catchment scale, bank counts are normally too time consuming, require multiple observations and often may not count every individual. Bank counts can be much more useful for smaller areas, especially for beaver families that are regularly observed, over a number of seasons, e.g. during scientific trials or on nature reserves.

In larger, more open and stiller water bodies, beavers may be relatively easy to observe and will largely ignore viewers who are quiet and still. Observations are more difficult in small, narrow stream systems, marshes or densely vegetated ponds. Generally, viewing beavers is best done about an hour before dusk, continuing until the light fades, or about an hour before sunrise in an effort to see returning individuals (Rosell et al. 2006). Pregnant or lactating females can be identified from the presence of protuberant nipples between their front legs. Although with experience observers may be able to determine the age-classes of beavers, the identification of individuals is often impossible unless they have obvious deformities such as tail injuries, or on rarer occasions a difference in coat markings. Variance in visible body length and width of head can help to distinguish the ages of individuals in a family. Adults have broad heads; and, while swimming, their backs are generally not visible above the water line, unless they are floating. Kits (<1 year) appear higher in the water and are quite buoyant. Their backs are completely visible above the water line, and their fur seems to be almost dry. Beavers over the age of ~3 years are usually very similar in size to adults. When out of the water, feeding along a shoreline for example, any differences in size become much easier to see. Although familiarity gained from regular observations will increase the ability to recognise any individual differences these tend to be slight and can be hard to observe. One benefit of watching an active lodge at emergence times is that it may be possible to count the occupants as they come and go (being careful not to double-count returning animals!). The reproductive status of the family can also be determined, as more than two animals may indicate either the presence of offspring or an active breeding pair. Beavers may dive and stay submerged for some time; and, when a beaver is disturbed, it may be possible to hear the characteristic slap of its tail on the water surface that precedes a dive. Their distinctive gnawing on woody vegetation can be heard on still evenings over a considerable distance. Spotlighting beavers from boats at night is also a common method of observation to which they will become habituated when the process is repeated over time.

Figure 7.2 (Left) Camera trap placed on freshly used feeding station, with metal pole marked by reflective tape at 10 cm intervals for comparative purposes to distinguish size differences between beaver family members. (Right) Camera traps can monitor trap (unset) use by beavers. (Scottish Beaver Trial)

Camera traps are a very popular aid for wildlife studies. There is a broad range of information available on specifications of different models and designs. Camera traps are particularly useful in studies of beavers to confirm presence, e.g. occupancy of a lodge. They can be the most effective tool for recording more secretive beaver behaviours such as scent-marking, canal-excavation, or lodge- and dam-maintenance. Cameras have been used to monitor beaver-trap use, determine the presence of kits, assess the number of individuals present at a specific location, identify their age class, identify pregnant/lactating females, and monitor behaviours. Permission from the landowner should always be obtained before cameras are placed at a specific location. Their positioning should be carefully considered to ensure that images of people are avoided and to reduce the chances of theft or damage. Fresh feeding stations along the shoreline, or obvious foraging trails, are likely to afford the best results, as these features may be used by more than one individual on a regular basis. During the autumn, beavers tend to be more active in and around their lodges, engaging in lodge-maintenance and food-caching behaviours.

7.4 Distribution mapping and population estimates

The mapping of field signs can be relatively straightforward; however, to get an accurate indication of distribution, consideration should be given to the area and scale of interest (distribution within a particular area, within a catchment, etc.), and over what timescale (snapshot in time, or how/if a population is spreading). These factors, along with resources available, are likely to determine how distribution mapping will be used and what it can tell you. Distribution mapping, if not repeated, may be misleading in some areas, particularly if trying to determine whether beavers are colonising new areas or simply moving through an area leaving signs of activity but may not be resident. Repeated surveys over time, and determining where clusters of field signs are of mixed age, may indicate active territories as opposed to areas through which dispersers have passed.

Figure 7.3 Scent-marking along the shoreline at the end of a well-used forage. (R. Campbell-Palmer)

One way to obtain a more accurate assessment of distribution and population size is to estimate beaver abundance by attempting to identify the number of family groups along a stretch of river (e.g. Campbell et al. 2012a). In a recently colonised area, these groups may be quite well separated; but, as the population becomes established, gaps may then become occupied, with scent mounds providing indications of shared territorial boundaries between groups (see below). As beavers are highly territorial, their density is self-limiting. The number of family groups along a stretch of river will also depend on the quality of the habitat, particularly the amount of food available. Signs of beaver activity will tend to cluster around the home lodge or burrow, although a complicating factor is where a family group uses more than one lodge or burrow.

Undertaking repeated, successive lodge observations and recording individual animal counts (at dusk and dawn), after the kit-emergence period (July–September), can provide important information on the number of individuals occupying a lodge, and their age-classes (Rosell et al. 2006). Scaling up from family groups to a number of individuals is usually done by assuming an average number of individuals in a family group (e.g. adult male and female, and 1–3 offspring). For example, the size of an average beaver family, from a review of 13 beaver studies in Europe and observations of beavers living at high densities in Norway, is estimated at 3.8 ± 1.0 individuals (Rosell and Parker 1995; Rosell et al. 2006; Parker and Rosell 2012).

Figure 7.4 Mapping of different beaver family territories over several years through a combination of animal observation, trapping, radiotracking and location of scent mounds, River Lunde, Norway. (Campbell 2010)

7.5 Habitat assessment prior to beaver release

Where further reintroductions of beavers are planned in Britain, habitat assessments of potential release sites will be required to assess the suitability of these locations. Methods for identifying the suitability of habitat for beavers have been published by Allen (1983), with modified methods in Halley et al. (2009), and by Macdonald et al. (1997). Full protocols are currently available on the SNH website; the IUCN (2013) and Scottish National Species Reintroduction Forum guidelines (2014) should also be considered.

The main features to consider in any site assessment for beavers are:

•The composition and structure of the vegetation within 30 m of the water’s edge

•The distribution and abundance of palatable riparian trees

•The character of the riparian edge habitat

•The available range of emergent or submerged aquatic plants

•The hydrology of the water bodies available to the beavers, including flow speeds, level stability and shoreline features

•Topography – gradient of land, substrate type, valley shape

•Associated land-use – disturbance, infrastructure, water use

However, it should be noted that Habitat Suitability Index models are good for species with specific needs, such as capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus), but tend to be much less suited for beavers which can adapt the habitat to their needs. Previously some of these models have been applied to areas and deemed them unsuitable for beavers, and which are now supporting healthy beaver populations – hence, caution and common sense should also be applied. Map based models need to take into consideration the spatial scale at which beavers select habitat. For example, riparian woodland less than 10 m deep may provide sufficient woody resources for a beaver family but is unlikely to mapped at anything other than fine scale. In time, and with growing population densities, beavers can occupy even the most modified landscapes if no other options are available.

Key concepts

•Beaver monitoring and surveying requires ecological knowledge, particularly to locate all the resting sites, to age the field signs and to determine the number of animals present.

•Trapping and handling requires some specialised knowledge, training and equipment. This is likely to require a licence; and landowner permission should be sought in advance.

•Field signs are unique and obvious, though population estimates based on these are difficult due to persistence in the environment, seasonal use/patchy feeding, population densities, habitat quality and multiple resting sites.

•Beaver scent mounds mark territorial boundaries; these mounds have a distinctive smell which is easily recognisable once learnt.

•Beaver observations are possible at dusk and dawn; look for water movement and sounds (gnawing).

•Camera traps are very useful to identify habitat use, different individuals, the presence of pregnant females/kits and secretive behaviours.

•Population size for an area is typically estimated during winter when active lodges/burrows can be identified through the presence of a food cache. Each active territory is then multiplied by 3.8 (representing the average number of family members) to obtain the population size.