Throughout research of the sort involved here, one needs to be continuously conscious, as already pointed out, that it is impossible to get more than approximations of the fact on the incidences and frequencies of various types of human sexual behavior. Memory cannot be wholly accepted as a source of information on what has actually happened in an individual’s history. There is both deliberate and unconscious cover-up, especially of the more taboo items; and in dealing with people of diverse mental levels and educational backgrounds, there are differences in their ability to comprehend and to answer questions with any precision in an interview.

Moreover, it is difficult for a person who has not kept a diary, and especially for one who is not accustomed to thinking in statistical terms, to know how to average events which occur as irregularly as sexual activities usually do. The mass of the population is not often called upon to estimate the frequencies with which they engage in any sort of activity, sexual or otherwise. This is most obvious in dealing with poorly educated persons, and with mentally low grade individuals. Most persons are inclined to remember frequencies for periods when the activities were regular, and to forget those periods in which there was material interference with activity. In marital intercourse, for instance, there are menstrual periods, periods of illness, periods of travel when spouses are apart, periods of preoccupation with special duties which, affecting either of the two partners, interfere with the regularity of intercourse for both of them. While other sources of outlet may fill in some of these gaps, there are situations in which no kind of sexual outlet is readily available; but these blank periods are not always taken into account by a subject who is estimating averages for a history.

It has, therefore, been important to secure some measure of the size of the error for which allowance must be made on the calculations in the present volume. A number of techniques have been used for these tests, and a considerable body of information is now available on the validity of the data. We shall want to continue with these tests as the study expands.

In Chapter 2 it was pointed out that the techniques of the interviewing have provided a considerable control against exaggeration, but that there is a greater likelihood of understatement and cover-up getting by without being detected. In Chapter 3 the relation of validity to size of sample has been discussed. The present chapter covers the special devices which have been used to test the significance of the calculated data.

In order to test the constancy of memory, re-takes of whole histories have been made on 162 of the males and females who have contributed to the present study. It is unfortunate that a larger series is hot now available, and this is one of the programs that should be expanded in the future progress of the research. In every case there has been a minimum lapse of eighteen months between the original history and the re-take, and in many cases three to seven years have intervened. The mean lapse has been 38.5 months. Re-takes, of course, cover activities which had not been engaged in until after the time of the original history; but with allowance for that fact, correlations have been made between the two records, for a diverse list of representative items. The results are shown in Table 13. There are no calculations of reliability which are more illuminating than these, and the table merits detailed study.

The analysis indicates that memory and/or cover-up, or other chance factors, introduce errors on certain items and on certain whole groups of items, while there is greater validity on other items. The incidence data are the most consistent. The coefficients of correlation (tetrachoric) on incidences are better than 0.9 in every case and better than 0.95 in all but three of the cases. The number of identical responses is better than 90 per cent, in every instance. The differences between the means calculated for the original histories, and the means calculated for the re-takes, are less than 2.4 per cent in most cases. The differences are larger only in regard to masturbation and to the homosexual, where the error is about 4 per cent. Throughout this volume, the incidence figures may, therefore, be accepted as very reliable. Many persons will find it difficult to believe that the high incidences shown for several types of sexual activity are not exaggerations of the fact, but every calculation indicates that they are understatements, if they are in error at all.

The next most accurate material covers the vital statistics of the population. There are data on the age of the subject, his marital status, the ages of his parents, the number of his brothers and sisters, his educational and religious background, etc. The coefficients of correlation (Pearsonian) are higher than 0,8 in every instance, and in six cases out of eight they are higher than 0.9. There are identical responses on the original histories and re-takes for better than 80 per cent of the subjects, on eight out of twelve items. The lowest scores concern the ages of the mother, of the father, of the wife at marriage, and of the husband at marriage—in that descending order. The differences between the means for the original histories, taken as a group, and the means for the re-takes are, however, immaterial, and the averages shown throughout the present volume can be accepted with little reservation. On the other hand, wherever the vital statistics on an individual history are to be used in a calculation, there should be allowances of a year, plus or minus.

Table 13. Comparisons of data on original histories and re-takes

108 males and 54 females are involved. The lapse between originals and re-takes ranged between 18 and 88 months (7 years and 4 months). The mean lapse is 38.5 months. The more than 200 “cases” in the frequency data depend on the fact that a single history may contribute data on more than one 5-year period.

Reports on ages of first experience in each type of sexual activity are much less accurate. The coefficients of correlation vary between 0.5 and 0.8. The number of precisely identical responses is quite low, ranging from 13 per cent to 57 per cent on most items. The number of responses that are identical within one year, plus or minus, is much higher, lying between 70 and 87 per cent on more than half of the items. However, in spite of the inadequacies of individual histories, the means for the whole population may be accepted with less question. The differences between the means for the originals and the means for the re-takes ordinarily constitute 5 per cent or less of the quantity involved. The lowest scores on memory of first experience pertain to the pre-adolescent sex play and to the first experiences in nocturnal emissions and heterosexual petting. These items are more indefinite and therefore more difficult to remember than such things as first ejaculation, first coitus, or first experience in other socio-sexual activities.

Reports on frequencies of sexual activity give correlations which run close to 0.6 on all of the items. This is a significant correlation, but not as reliable as that obtained on incidences or on many of the other items. The percents of identical responses are low, lying between 25 and 50 percent, and the percents of identical responses plus or minus one unit of measurement are still less than 65 per cent in most cases. The error on the means lies between 5 and 10 per cent on most items, and that much allowance should be made on any statement in this volume concerning frequencies of sexual activity. While the frequency data on any individual history are undoubtedly approximations to the fact, they are not accurate enough to be pushed in detail.

The poorest memory applies to the ages at which the individual first learns particular things, e.g., the age at which he first learns there is such a thing as intercourse, pregnancy, prostitution, etc. Even when a leeway of two years is allowed as identity, the coefficients of correlation are no higher than 0.4 and 0.5, and the number of identical responses is under 50 per cent. If an additional allowance is granted of plus or minus two more years, the number of identical responses is brought up to something over 80 per cent on most items. This means that a five-year allowance must be made for any answer in this area, i.e., an allowance of plus or minus 2.5 on the given answer. Here again, however, the means calculated for whole populations are much better, and a correction of something between 1 and 5 per cent seems a sufficient allowance.

There is no way of knowing whether the responses are more accurate on the first histories or on their re-takes, or whether either of them represents identity with the fact. Re-takes test the constancy of memory and the constancy of the degree of cover-up, rather than the validity of the record. There is reason for believing that memory which stays as fixed as it does on most of the items in this study is not wholly capricious, but allowance must be made for the fact that one may come to believe in a fiction on which he has decided at some time in his life. In general, the re-takes raise the incidence figures and, strikingly enough, they raise the record of age of first experience, first knowledge, etc. This suggests that as the individual grows older the period of beginning any type of activity seems to him to move up, to some degree. These are matters of broad import in psychology, but their more extensive examination has not yet been possible within the confines of the present study.

The histories of the two spouses in any marriage should contain a certain number of identities, and comparisons of such pairs of histories have given some insight into the validity of memory. Therefore, in this study, especial attention has been given to securing histories from spouses, and 231 pairs of spouses are the bases of the comparisons shown in Table 14. The items analyzed in the table include some vital statistics, the record of coital frequencies, and details concerning the foreplay, positions, and other techniques employed in the marital coitus. On the whole, the record shows an amazing agreement between the statements of the husbands and of the wives in each marriage, although allowance must be made for the possibility that there may have been collusion between some of the partners, and a conscious or unconscious agreement to distort the fact.

The coefficients of correlation between the replies of the husbands and the replies of the respective wives have the following values:

Correlations in Replies of Spouses

In regard to three-quarters of the items, the coefficient of correlation between the replies of the husbands and of the wives is 0.7 or better; for nearly half of the items it is 0.8 or better; and for more than a quarter of the items it is 0.9 or better. These are very high scores, as correlations go in social and psychological studies.

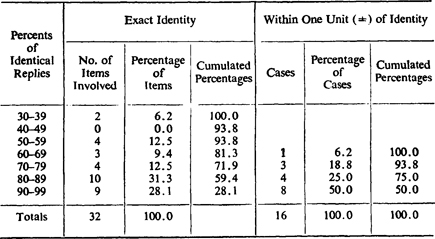

The number of identical replies received from the two spouses in each marriage is as follows:

In regard to nearly 60 per cent of the items, the replies were identical for 80 per cent or more of the couples. In regard to three-quarters of the items, they were within one unit of identity for 80 per cent of the couples. These close identities are particularly impressive when it is remembered that in many instances there were intervals of two to six years or more between the interviews with the two spouses. On half of the items, there is near identity in something between 90 and 100 per cent of the histories. In most instances, near identity is about all that a student of behavior is interested in; it rarely matters whether the age of the spouse is a year one way or the other of the reported age, whether the other spouse has had six years or eight years of schooling, whether the male is a semi-skilled or a more skilled mechanic. Allowances are also to be made for the fact that some persons calculate their ages as from the last birthday, and some persons from the forthcoming birthday, and that a difference of a year in two reports may, in actuality, mean identity.

Averages for the entire group of histories are still closer than the correlations on individual histories. The differences between the means calculated for all the males and the means calculated for all the females are quite insignificant on all but a few items, as an examination of Table 14 will show.

The coefficients of correlation and the percentages of identical replies are low only in regard to the frequencies of marital coitus, and in regard to the percentage of the time in which the female reaches orgasm during the marital coitus. On the latter point, the male believes that his female partner experiences orgasm more often than she herself reports; but it is to be noted that the wife sometimes deceives her husband deliberately on that point. In regard to the frequencies of marital intercourse, there is an interesting psychological element involved. It is often the female who reports the higher frequencies, and this is undoubtedly related to the fact that females often complain of their husbands’ desire for more coitus. Consequently, the females may be overestimating the actual frequencies. Similarly, the husbands regularly complain of their wives’ lack of desire for coitus and, in consequence, are probably underestimating the frequencies with which they do have it. On individual histories, errors on this particular point may be expected in as many as two-thirds of the cases; but in regard to averages for whole populations, the correction is, again, remarkably small.

For most items of the sort covered in this study, it may be expected that something between 80 and 99 per cent of the subjects will give replies that will be verified, independently, by the partners in their marriages.

In addition to re-takes and pairs of histories from spouses, a variety of other cross-checks have provided some further measure of the accuracy of memory. For instance, the internal consistency of a history, as it is pieced together in an interview, is of considerable significance as a test of validity. In each case, the subject is asked to supply a great many dates and records of ages in a sequence which is far from chronologic. Nevertheless, there is usually considerable coherence in the chronology that comes out of such a tabulation. Some time, it may be possible to reduce this matter to more precise calculation.

In Chapter 2, in connection with a discussion of interviewing techniques, it was pointed out that a skillful interviewer develops a certain ability to recognize falsification and cover-up when taking a history, and does have a considerable measure of the validity of the record he is getting, even though it may not be possible to reduce such a measure to statistical terms.

In Chapter 2 it was also pointed out that the trained interviewer must have a considerable fund of information concerning patterns of sexual behavior in different segments of the population. The constancy with which such patterns are followed in individual histories is very high, as later chapters (particularly Chapter 10) in the present volume will show. While it may be questioned whether a subject sometimes reports what he thinks is usual and acceptable in his social group, it should be emphasized that exceedingly few subjects have any idea of the patterns of behavior of other persons in their group. The histories cover such a mass of detail as few persons have ever discussed with their friends, and they simply do not know how those friends or any other persons in the same group are answering such questions. When 90 to 95 per cent of the persons in any social level report histories which agree with the patterns shown in Chapter 10, they not only establish the nature of the group patterns, but establish the validity of their own reports as well.

Further cross-checks are provided by sexual partners other than spouses. Whether they are involved in heterosexual or homosexual relations, each partner may supply some information about the other individual’s history. The cross-references have been kept, and it may be possible to subject the material to statistical comparisons when the series are large enough. Now it can be reported that the secondhand information secured in this way has proved to be surprisingly accurate in most cases where there has been a chance to check it. Although none of this secondhand material has been used in any of the calculations in the present volume, it has been of value as a means of testing the accuracy of the related histories. Within the confines of the present chapter, a single example of this sort will have to suffice.

This example concerns the accuracy of the incidence data on the homosexual experience had by men in penal institutions and reported by them while they are under confinement in such institutions. This is material about which it is especially difficult to secure information, although in nearly all prisons there is a continuous undercurrent of gossip concerning such activity. The gossip reflects a mixture of desire for experience and bitter condemnation of such activity—a conflict between the individual’s personal needs, and his training in the social traditions on matters of sex. There is, of course, official condemnation of such activity; and this may involve, especially in institutions for men, severe corporal punishment, loss of privileges, solitary confinement, and often an extension by a year or more of the sentence of an inmate who is discovered, suspected, or merely accused of homosexual relations. To persuade such an inmate to contribute a record of his activity while he is still in prison, is a considerable test of the ability of an interviewer. Nonetheless, we have gotten such records from something between 35 and 85 per cent of the inmates of every institution in which we have worked.

In one prison, a male who was well acquainted with the institution agreed to take the list of three hundred and fifty men who had contributed histories to this study, and to indicate which of them were, to his knowledge, currently having homosexual relations. About most of these men he knew nothing, but from the list he picked 32 with whom he claimed to have had relations, or whom he had actually seen in such relations. The informant never knew how his record compared with the data we had secured in the interviewing, but the histories showed that 27 of the 32 men (i.e., about 85 per cent!) had admitted their experience when they were first interviewed. Two of the others had left the institution before they could be interviewed again, but the remaining three readily admitted their activity when they were called back for a second conference. This provided a check on the validity of secondhand reports and, incidentally, gave some measure of the extent of the cover-up that we are getting in the histories. Considering the nature of the item involved, this 15 per cent failure probably approaches the maximum which will be found anywhere in this study.

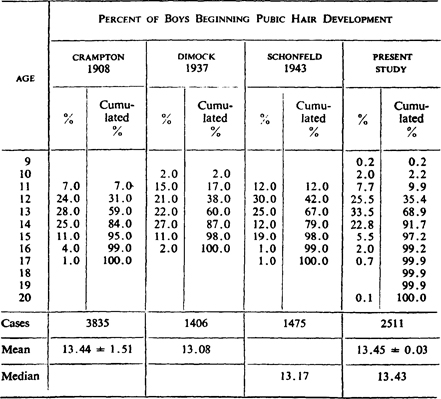

It is possible to make comparisons of certain of the data obtained by interviews in the present study, and data obtained in some other studies from direct observations on similar groups of males. The readiest body of such material concerns adolescent developments. In Figure 15, data on pubic hair development, drawn from three of the observational studies (Crampton 1908, Dimock 1937, Schonfeld 1943), are compared with data contributed by the subjects in the present study, on the basis of recall. The near identity of the recall curve and the other curves is remarkable, especially in consideration of the fact that many subjects protest that such an item as pubic hair development is recalled with less certainty than most other items. The larger series in the present study gives a growth curve which is smoother and more usual in type than the curves which some of the smaller series give. It is to be noted, again, that though this comparison goes a long way to justify recall as a source of averages for whole groups, it does not demonstrate how accurate the memory of any particular individual may be concerning his own individual history.

Table 15. Comparisons of data obtained in four studies on pubic hair development

The data from the Crampton, Dimock, and Schonfeld studies were based upon physical examinations of young boys. The present study has been dependent upon the memory of older persons recalling their adolescent experiences.

There are a number of other observational studies of adolescent developments (cited in Chapter 5), but unfortunately none of them provides data which can be used in comparison with data from the present study. Some of these other studies are based on populations which are too small to be significant. Some of them appear to involve gross errors. In several cases, the other studies have used definitions of adolescent characters which are different from those used in the present study, e.g., voice change is defined in some of the studies as the first sign of deepening voice (which is in reality often a pre-adolescent development), and pubic hair is defined as kinky hair (which may not appear until sometime after the first distinct but straight hair develops in the pubic area). It will, therefore, be necessary to wait until further observational data are available for further testing of the validity of recall on these characters.

Figure 15. Comparison of memory with observational data

Record for age of onset of growth of pubic hair. The Crampton, Dimock, and Schonfeld studies based upon physical examinations of boys. The present study based on memory of older persons recalling adolescent experience.

It is to be said again that a major portion of the present volume is concerned with incidence figures and with average frequencies of the various types of sexual activity, calculated for groups which represent whole portions of the total population. In many instances the data have been calculated for series of such groups, as, for instance, successive age groups, groups representing successive levels of educational attainment, groups representing series of social levels, etc. In such series the incidence data and the means for the successive groups fall into straight lines or into curves which are remarkably smooth. This is to be seen in many of the charts shown in this volume. It is to be noted again that all of these curves are based on raw data and have not been smoothed by any statistical device. Some striking instances of such smooth trends are shown in the following charts:

| Fig. 35. | Age and number of sources of outlet. |

| Fig. 37. | Age and incidence of impotence. |

| Figs. 38-88 (in part). | Age and mean and median frequencies of total outlet, and of particular sources of outlet. |

| Figs. 38-88 (in part). | Age and active incidence data on various sources of outlet. |

| Figs. 14-24. | Age and accumulative incidence of various sources of outlet. |

| Figs. 98-105. | Social levels and mean frequencies of various sources of outlet. |

| Figs. 136-160. | Individual variation in frequencies of various sources of outlet. |

While irregularly shaped curves are not to be ruled out as necessarily inaccurate, there is some warrant for considering that smooth trends in such curves are evidence of their approach to reality. The population on which each point in such a curve is established is usually quite different from the population on which each other point is established. The individuals in each population come from a diversity of geographic and social backgrounds. They have been contributing now over a period of nine years. For the most part, no individual has had any way of knowing what other persons in the same group have done in their lives or reported in their interviews. In the majority of cases the subjects in this study have not known enough about the statistical breakdown of the population to have any precise idea of the confines of the groups to which they themselves belonged. When data obtained under such circumstances give averages which show such smooth trends, there is considerable warrant for believing that the vagaries of capricious memory have not been involved as often as the realities, namely the biologic and social factors which operate with steadily increasing or steadily diminishing force at successive points on the curve.

When the cases which establish particular points on these curves become too few, the points no longer fall within the smooth trend, and this exposes the extent of the deviations which too small samples may introduce.

When a study of everyday people discloses such unexpected behavior as the present study has disclosed, it is natural enough that one should wonder whether there has been some bias in the investigator’s choice of subjects or his emphasis in interviewing. On this point, it has already been explained (Chapter 3) that the persons who have contributed histories have represented considerable samples and, whenever possible, hundred percent samples of each group that has been involved in the study. There has been next to no selection of subjects on the basis of anything that was previously known about their histories. The only exceptions have come in regard to a few extreme items which, as already explained (Chapter 3), could not have been obtained by way of hundred percent samples; and most of the histories have come from unselected individuals in whole groups. Such unselected series have been the prime bases for the incidence figures in this volume. See the preceding chapter for more detailed comparisons of the data obtained from hundred percent samples, and from the remainder of the population.

One of the questions most frequently raised about the present research, and a thoroughly legitimate question about any research, concerns the possibility of another investigator duplicating the results. Moreover, in any project which has involved two or more investigators, it is important to compare the results obtained by each, before one can fairly add together the data obtained by the several interviewers. In consequence, throughout the years of this investigation repeated comparisons of that sort have been made.

Comparisons of the data obtained by different investigators can be significant only when the persons contributing histories to each investigator belong to the same sex, race, marital status, age, educational level, rural-urban group, religious group, etc. It is meaningless to compare data drawn from quite different sorts of groups. Even when comparisons are made for groups that are the products of six-way breakdowns, which is the limit possible with the sample now at hand, there are certainly many other factors which affect variation within each group. Consequently, it is not to be expected that the material obtained by two interviewers working with two different populations, even after a six-way breakdown, should be quite identical.

Table 16 compares the data obtained by the three authors of the present volume. The table includes all of those groups from which each of the interviewers has obtained at least 300 histories. To compare smaller populations would have introduced errors consequent on size of sample (Chapter 3). The senior author began accumulating histories some years before the other two authors were involved; and on the chance that the first investigator’s techniques of interviewing and his methods of recording may have varied in that time, the comparisons in Table 16 are confined to the data obtained by each of the three interviewers during the same period of time, namely, the more recent four years of this study.

Table 16. Comparisons of data obtained by different interviewers

Comparisons confined to groups with over 300 histories, of same background for sex, race, marital status, educational level (all of college level), and age. Based on histories taken during last four years of the research.

The most important conclusions to be drawn from these comparisons are:

1. Three different interviewers have obtained very similar data from three different populations. Out of the 75 sets of calculations which appear in Table 16, 35 are so similar that the differences are immaterial—closer than any person could calculate about his own history. Such identity is amazing. There seems no reason to doubt that any other group of investigators could duplicate these results if their scientific objectivity and their methods in interviewing were comparable to those which have been used in the present study. In about 10 of the 75 sets of calculations, there are more or less material differences between the lowest and the highest figures.

2. The incidence data are more nearly identical for the three interviewers than the frequency data. There is close identity in incidences even for such a taboo item as the homosexual where, it will be noted, the active incidence figures in each of the five-year periods prove to be five to ten times as high as any which have previously been published. Whether the actual incidence figure for the homosexual in any particular group is 17.5 per cent or 21.3 per cent is of no great moment. The fact remains that the general locus of this, and of all the other figures, is established by the independent interviewing of three persons drawing their samples very largely at random, or from hundred percent groups which (especially in the case of the college level) constituted a considerable portion of the sample.

3. Some selection has been involved in assigning subjects to interviewers. Older persons, persons with more promiscuous histories (whether heterosexual or homosexual), and persons who were expected to prove reticent because of socially unusual items which were known to be in their histories, have more often been interviewed by the senior investigator, especially during the early years in the training of the younger members of the staff. This undoubtedly accounts for some of the differences between interviewers: for the lower homosexual incidence and frequency figures for the third interviewer, for the higher frequency data on pre-marital intercourse for the first interviewer, etc.

4. The frequency data for masturbation and for pre-marital intercourse (and in consequence for total outlet) are highest in every age group for the first interviewer and lowest for the second interviewer. The incidence and the frequency data on all of the other items and the incidence data even on masturbation and pre-marital intercourse are very closely duplicated by the two interviewers. On the item which is most difficult to uncover, namely, the homosexual, the two interviewers secured almost exactly the same results. The differences in their findings on masturbation and premarital intercourse may be due to some selection of the subjects who have contributed the histories, or to real differences in the populations with which the two interviewers dealt; but this does not seem a sufficient explanation. On this point, further investigation needs to be made.

Table 17. Comparisons of data obtained by different interviewers, on masturbation

Based on males of the college level.

Figures 16-18. Comparing accumulative incidence data obtained by different interviewers

Data on masturbation, nocturnal emissions, and intercourse of any sort.

Table 18. Comparisons of data obtained by different interviewers, on nocturnal emissions and on heterosexual coitus

The coitus data include intercourse from any source, pre-marital, marital, extramarital, or post-marital, with companions or with prostitutes.

Table 19. Comparisons of data obtained by different interviewers, on pre-marital intercourse and on intercourse with prostitutes

Total pre-marital intercourse includes the coitus had with companions and with prostitutes. Total intercourse with prostitutes includes pre-marital, extra-marital, and post-marital data.

Table 20. Comparisons of data obtained by different interviewers, on total homosexual outlets

Based on males of the college level. Includes pre-marital, extra-marital, and post-marital experience in the homosexual.

Figures 19–21. Comparing accumulative incidence data obtained by different interviewers

Data on pre-marital intercourse, intercourse with prostitutes, and homosexual outlets.

Table 21. Comparisons of data obtained in two successive four-year periods

Comparing results obtained by the same interviewer (Kinsey) in the earlier half and in the later half of the study. All data from groups of college level (“educational level 13+”).

5. The accumulative incidence curves (Chapter 3), derived from the data gathered by the three interviewers (Tables 17–20, Figures 16–21), provide a striking demonstration of the capacities of different investigators to secure similar results, even on such intangible material as must be dealt with in the study of human sex behavior. In most cases, the incidence data obtained by the several interviewers are so nearly in accord that the curves lie precisely on top of each other. In those cases where there are differences, the general loci of the data are still confirmed, although there may be some question of the precise position of the fact between the two calculations, or to one or the other side of the extreme calculations.

The question involved here concerns the capacity of an interviewer to obtain uniform results over any long period of years. Is there a possibility that one’s methods of recording change, particularly in regard to evaluations of items that are not strictly measurable? Is there a possibility that changes have entered in the methods of calculating from the raw data, since the first procedures were devised nine years ago? As a study of these problems, comparisons are shown in Table 21 between the data obtained by the senior author during the first four years of the research (1938–1942), and the data obtained by the same interviewer in the last four years (1943–1946). The two junior authors have not been involved in interviewing long enough to make such comparisons possible. Table 21 includes calculations on every group for which 300 or more cases were available from the interviewing done by the senior author in each and both of the periods. Comparisons of the accumulative incidence curves for masturbation, nocturnal emissions, pre-marital intercourse, and the homosexual in the two periods are shown in Tables 22 and 23, and Figures 22–24.

A study of the data leads to the following conclusions:

1. The active incidence data are phenomenally close in the two successive four-year samples. They leave no doubt of the general locus of the fact for every type of sexual behavior, and they even suggest that there can be considerable precision in determining these facts.

Table 22. Comparisons of data obtained at two different periods, on masturbation and nocturnal emissions

Accumulative incidence data based on the pre-marital histories of males of the college level, taken by one interviewer (Kinsey) in two successive four-year periods.

Figures 22–24. Comparing accumulative incidence data obtained by one interviewer in successive four-year periods

Data on nocturnal emissions, pre-marital intercourse, masturbation, and homosexual contacts. All calculations based on males of college level (13+).

Table 23. Comparisons of data obtained at two different periods

Accumulative incidence data based on histories of males of the college level, taken by one interviewer (Kinsey) in two successive four-year periods. Total pre-marital intercourse includes relations with companions and with prostitutes.

2. The accumulative incidence data are so nearly identical for the two different periods that it is highly Improbable that two groups obtained in the same period would ever compare more closely. There is practically identity in regard to masturbation, nocturnal emissions, and the homosexual. The curves for pre-marital intercourse are about a year and a half apart during most of their rise, but reach nearly identical levels.

3. The conformance of frequency data, in the successive four-year samples, is quite close. In general, the medians are closer than the means. Since the values of means are affected by a few high-rating individuals, as the values of medians are not, this greater constancy of the medians indicates that the frequencies of persons with unusually high rates of outlet vary in successive samples, while the frequencies of the individuals in the mass of the population do not vary so much. This is obviously due to the fact that there are fewer extreme individuals and that they are not picked up in any process of sampling as regularly as the more average persons in the population. Only large samples can smooth out the effects of high-rating cases.

4. Some of the differences that do exist between the successive four-year samples may be the product of instability in the techniques of recording and calculating data, but it is just as likely that they are due to actual differences in the samples which have been involved. The comparisons in Table 21 have been made for populations resulting from a five-way breakdown (sex, race, marital status, age, and educational level), but there are many other factors that can modify the picture for particular groups.

5. The differences in calculations on successive four-year periods are not consistently higher nor lower. This means that no consistent bias has entered into the processes of the study,

6. There was, inevitably, some experimentation and some trial and error in developing the techniques of interviewing and in the manipulation of the data in the early years of the research. However, the errors that may have entered in this way do not appear to have been so large that the earlier histories need be eliminated from calculations which are based on the total body of histories. Throughout the present volume the data from the two four-year periods have, of course, been combined in all of the calculations, and the consequent statistics may (or may not) be nearer the realities of behavior than either of the sets of calculations shown in Table 21.

7. The comparisons in Tables 21–23 seem to indicate that methods of securing subjects, proficiency in interviewing, skill in using the code in which the data are recorded, and calculations and judgments which the data undergo in their statistical treatment, can be maintained at such uniform levels as many persons would have considered impossible in a case history study which is liable to error from so many sources, and which deals with as taboo a subject as sex.

Any consideration of the validity of case history data involves the question of the relative accuracy of immediate memory versus remote recall. Does the subject, in an interview, give a more accurate record of his more recent or of his more remote activities? Since the subjects were of various ages when they contributed their histories, the data shown for any particular age period have been obtained partly from the more immediate recall of younger persons, and partly from the more remote—sometimes the quite remote—memory of older persons. Can data obtained by such different processes fairly be added together?

It has not been possible to undertake any study which would go into all of the complexities of this situation, although we have some measurements toward such a study. In the course of the interviewing, we have acquired certain impressions that may be worth recording in anticipation of the time when there will be enough material to make more precise determinations. These impressions cover the following points:

1. More recent events seem, in general, to be recalled more easily, and more remote events are recalled with greater difficulty. This seems reasonable enough, but it proves nothing concerning the validity of the recall. It seems reasonable to believe that more immediate and more easily recalled events would be reported with, greater accuracy, but there are at least certain circumstances where that is clearly not so.

2. Pre-adolescent children, as young as three or four years of age, are ordinarily capable enough of recalling very immediate events, but often fail to recall activities and knowledge acquired only a few months or a year or two before. How much of this forgetting is a simple lapse of memory, and how much is psychologic blockage, is not readily determined. The psychoanalysts are undoubtedly correct in seeing considerable significance in the sometimes deliberate but more often unconscious repressions that develop in these early years, but they do not sufficiently allow for the simple failures of memory which seem sufficient explanation of some of the inadequacies of recall among younger subjects. There is no doubt that the analysts are correct in believing that more of this early experience is lost to memory than of the experience of any other segment of the life cycle.

3. Older persons seem to recall remote events, in many cases in minute detail, while forgetting what happened in recent weeks. This is rather generally accepted, and our own experience seems to confirm this. There are some psychologic studies that show the poor quality of the immediate recall of the aged (Thorndike 1928, Gilbert 1941), but apparently no precise studies on the validity of their remote recall.

4. While the quality of memory may show some degree of correlation with intelligence and with the extent of the individual’s formal education, there appears to be considerable accuracy of memory among some less intelligent and many poorly educated persons. Illiterate persons may remember such an amazing amount of detail about dates, names, and places, as is rarely found among educated persons whose minds are continually preoccupied with what they read in newspapers, magazines, and books. We still need precise measures of the accuracy of memory among these lower levels, but the data secured on the histories from such persons show consistencies in the chronology that are often remarkable. On the other hand, some professionally trained persons, for some reason still to be analyzed, may be much confused in attempting to construct a chronology of their own activities, and the most extreme and absurd disparities secured on any of our re-takes have come from graduate students and university instructors who had especial interest in the research and were doing their best to cooperate.

5. As usual, incidence figures are more accurate than frequency data. Estimates of average frequencies are especially difficult for children, for individuals of low mentality, and for most poorly educated individuals. Frequencies are more difficult to estimate when they concern remote periods of time.

6. The possibly greater accuracy of recent memory is at least partially offset by the greater extent of cover-up on recent events. Legal statutes of limitation are in line with the general human tendency to forgive something that is more remote, while reacting violently to more recent happenings. Consequently many subjects in a case history study will admit participation in the more taboo sexual activities at some time in the past, while insisting that such activities are no part of their current histories, or that the frequencies are now very much reduced. An undue number of persons have discontinued masturbation, pre-marital coitus, extra-marital coitus, mouth-genital contacts, homosexual activities, prostitution, or animal intercourse the year before they contributed their histories—or a few months or even weeks before! Re-takes have subsequently shown that the year of the first history was in actuality involved, although the activities are again supposed to have terminated before the date of the re-take.

7. Certain items are minimized, certain items played up, depending upon the immediate mental state of the subject. Re-takes, especially series of re-takes on the same person, and histories which can be compared with the precise records of a diary, show that these reactions fluctuate, rather than erring always in the same direction. For instance, the pre-marital heterosexual experiences which were reported on the first history may be minimized on the re-takes, while the report of the homosexual experience may be extended. A second re-take on the same individual may play up the heterosexual and minimize the homosexual experience, especially if the subject is now in the army and conscious of official attitudes on that subject. Six months after being released from the army, the homosexual record may again be obtained in something like the form which was reported on the earlier histories.

The generalization to be drawn from these several impressions is that the memory of more recent events may be more accurate (except in the aged), but its accuracy is more or less offset by a considerable amount of cover-up on more immediate activities. What is the final effect on the quality of the individual record, and on the averages calculated for whole groups of individuals? The quality of the individual record is the clinician’s constant problem, but one on which we, unfortunately, can contribute nothing more at this time. That the individual record is not wholly specious, the data elsewhere in this chapter, especially the data on re-takes, definitely show. We shall hope to make still further studies on this point as soon as we have the large series of histories which such a study will demand.

As a further comparison of more immediate versus remote recall, the data in Chapter 11 bear on this point. The tables and charts in that chapter compare the younger half with the older half of the population which has entered into this study. The younger half is, of course, reporting more immediate experience. The older half, averaging about 22 years older than the first group, is recalling its early years from a distance which is that much more remote. While these data were originally calculated to study possible changes in behavior in successive generations, they also provide one more test of memory of recent versus more remote events. An examination of Chapter 11 will show that the incidence data for the two groups are, in most cases, almost precise duplicates. The frequency data are further apart in some groups but, again, precise duplicates in other groups. The factors involved in these diverse results are discussed in Chapter 11.

Throughout the whole period of this study, a variety of techniques has been employed to test the effectiveness of the methods of interviewing, the validity of the data which are obtained in an interview, and the appropriateness of the statistical techniques by which the data have been manipulated. It is unfortunate that these studies of method are not yet complete and, indeed, that they could not have been completed before the central problems of the research were laid out and their study initiated. But such investigations of method often demand more material than is needed to solve the problems which are central to the main study. In order to determine the necessary size of sample, for instance, it has been necessary to study some samples that were larger than those that have ultimately proved adequate. In order to compare results obtained by different interviewers, it is necessary that each interviewer have secured a sample as large as may be needed in the combined sample from all the interviewers.

Moreover, finished studies of method have to be made with populations which are homogeneous for at least the major items on the twelve-way breakdown used in this study; and the methodological investigations which are reported here in Chapters 3 and 4 are still restricted to a certain few segments of the population, chiefly to the college groups, because we do not yet have enough histories from other groups to make studies there. It will be highly important to secure some measure of the differences in validity of the data obtained from persons of different ages, of different educational and social levels, of different mental capacity, and different in still other respects. To that end, we shall continue this study of method as this research progresses.

The materials now in hand seem to justify the following conclusions concerning the validity of data obtained through personal interviewing in a case history study:

1. The accuracy varies considerably with different individuals. The inaccuracies are the product of simple forgetting, the deliberate or unconscious suppression of memory, and deliberate cover-up. Definite allowances must be made for such errors on individual histories obtained in the concentrated, relatively short interviews which have been used in the present investigation. Careful studies of the effectiveness of other types of interviewing—for instance, of the effectiveness of the psychoanalytic technique, with its two hundred or more hours spent on each individual—have never been made; and it is as yet impossible to make comparisons of the relative effectiveness of the methods used in the present study and in these other types of interviewing. It is not sufficient to depend upon the optimistic claims of each clinician for his own technique; and we hope, in time, to make joint studies with some other groups that will throw more light on these problems of interviewing.

2. In the present study, the validity of the individual histories varies with particular items and for different segments of the population. On the whole, the accuracy of the individual history is far greater than might have been expected, with correlation coefficients ranging above 0.7 in most cases, and percents of identical responses ranging between 75 and 99 on particular items. There are some low correlations which are highly significant because they give some insight into the factors which are responsible for errors and falsifications in reporting.

3. It is unfortunate that there is, as yet, insufficient experience to allow us to identify, in more than a part of the cases, those individuals who are least accurate in their reporting. The clinician needs this information, for he is most often concerned with the validity of the individual history, and less often with the validity of the data from any group of individuals. But further studies will need to be made before we are able to say how one can identify those particular individuals who are more accurate, and those who are less accurate as reporters of the events that have occurred in their lives.

4. The accuracy of the averages calculated for whole groups of individuals is definitely higher than the accuracy of the individual histories, as statisticians will readily understand. Where there is no bias which accumulates errors in a particular direction, errors on one side will compensate for errors on the other side and the averages come nearer the fact, as the various tests in this chapter indicate.

5. For all types of sexual activity, in all segments of the population, the incidence data are more accurate than the frequency data. The incidence data are the most accurate of all. The actualities must lie within 1 to 10 per cent, plus or minus, of the published incidence figures, and within 1 to 5 per cent of most of them. In regard to nearly all types of sexual activity there has undoubtedly been some cover-up, and the actual incidences are probably higher than the published figures. This applies especially to masturbation at lower social levels, to pre-marital and extra-marital intercourse at upper levels, and to the homosexual and animal intercourse at all levels. There is little likelihood that the calculated figures on any of these items are too high. There are abundant social reasons why an individual should deny or minimize the frequency of any activity which is taboo and, in the last analysis, all sexual activities except marital intercourse may, in some social groups, fall under that head.

6. Data concerning such individual and social statistics as age, education, events concerned with marriage, parents, siblings, etc., are the next most accurate. The averages for whole groups are so close to the averages obtained by direct observation that they may be accepted as precise statements of fact, although they are not so dependable on individual histories.

7. The frequency data are much less accurate than the incidence data. On individual histories they may be removed by as much as 50 per cent from the reality. Nevertheless, mean frequencies and median frequencies calculated for whole groups will not need more than a 5 to 10 per cent allowance, plus or minus. Since differences in frequencies of sexual behavior in different segments of the population may amount to something between 100 and 800 per cent, the comparisons will not be materially affected by the necessary corrections. The statements made concerning mean and median frequencies for whole groups are much more accurate than the best trained individual could be in reporting his own individual frequencies.

8. The least accurate data are those that concern an individual’s first knowledge of an event. This is true of the individual histories, but the averages calculated for whole groups are still reliable. The inaccuracies on these points are obviously dependent upon the indefinite nature of the educational processes by which one finally becomes conscious of the fact that he has definite knowledge on some subject. On individual histories an allowance of 2.5 years, plus or minus, should be made on the reported data. The means calculated for whole groups will not need more than a 4 or 5 per cent correction, plus or minus, on these items.

9. Again it should be emphasized that most of these calculations of validity have been based on the college segment of the population, which is the only group represented now by large enough series to warrant such examination. Comparable studies are needed to determine the validity of the data obtained from other segments of the population, and we plan to undertake such studies as soon as sufficient re-takes, pairs of spouses, series from different interviewers, etc., are available. Preliminary examinations of data from lower social levels suggest that variations in the quality of such reports are wider than the variations among college males. Consequently quite large series will be needed before it will be possible to make satisfactory validity studies on the more poorly educated groups.

Throughout the remainder of this volume, the raw data and the calculations based on the raw data are treated with a precision that must not be misunderstood by the statistically inexperienced reader. It has not been practical to carry this warning in every paragraph of every chapter. Neither has it been possible to qualify every individual statistic, as every statistic in any study of the human animal should be qualified. For the remainder of the volume it should, therefore, be recognized that the data are probably fair approximations, but only approximations of the fact.