Table 80. Relation between educational level and occupational class of subjects in present sample

Based on those males in the present sample who have finished their educational careers.

The sexual behavior of the human animal is the outcome of its morphologic and physiologic organization, of the conditioning which its experience has brought it, and of all the forces which exist in its living and nonliving environment. In terms of academic disciplines, there are biologic, psychologic, and sociologic factors involved; but all of these operate simultaneously, and the end product is a single, unified phenomenon which is not merely biologic, psychologic, or sociologic in nature. Nevertheless, the importance of each group of factors can never be ignored.

Without its physical body and its physiologic capacities, there would be no animal to act. The individual’s sexual behavior is, to a degree, predestined by its morphologic structure, its metabolic capacities, its hormones, and all of the other characters which it has inherited or which have been built into it by the physical environment in which it has developed. Two of the most important of these distinctively biologic forces, age and the age at onset of adolescence, have been examined in the earlier chapters of the present volume.

But through all of the previous chapters, constant consideration has been given to the significance of the psychologic factors which affect sexual behavior, and it should be apparent by now that the experience of the individual, the satisfactory or unsatisfactory nature of that experience, the conformance or non-conformance of that experience with the individual’s personality, attitudes, and rational thinking, and a great variety of other factors make the psychologic bases of behavior even more important than the biologic heritage and acquirements.

It is evident, however, that psychologic processes depend, to a considerable degree, upon the way in which external forces impinge upon the animal. For a creature with as highly organized a central nervous system as is found in the human animal, the most important external force is the social environment in which it lives. In the human species, the environment consists of one’s family, his close friends, his neighbors, his business associates, and his mere acquaintances. It also includes the thousands of other persons whom he has never seen but whose attitudes, habits, expressed opinions, and overt activities constitute the culture in which he moves and lives. These are the social forces which contribute to the individual’s behavior. There is, of course, no part of the individual himself which is social in nature, in quite the way that morphologic, physiologic, or psychologic capacities may be identified and localized in an organism. Occasionally social forces provide physical restraints on individuals, or facilitate their physical activities; but more often they operate only as they affect the individual psychologically.

Table 80. Relation between educational level and occupational class of subjects in present sample

Based on those males in the present sample who have finished their educational careers.

The present chapter and the three chapters which follow are concerned with the relation of the individual’s pattern of sexual behavior to patterns which are followed by other persons in the same social group—in the group in which the individual is raised, or into which he moves and establishes himself in the course of his lifetime.

The data now available show that patterns of sexual behavior may be strikingly different for the different social levels that exist in the same city or town, and sometimes in immediately adjacent sections of a single community. The data show that divergencies in the sexual patterns of such social groups may be as great as those which anthropologists have found between the sexual patterns of different racial groups in remote parts of the world. There is no American pattern of sexual behavior, but scores of patterns, each of which is confined to a particular segment of our society. Within each segment there are attitudes on sex and patterns of overt activity which are followed by a high proportion of the individuals in that group; and an understanding of the sexual mores of the American people as a whole is possible only through an understanding of the sexual patterns of all of the constituent groups.

These social levels are, admittedly, intangible divisions of the population which are difficult to define; but they are recognized by everyone as real and significant factors in the life of a community. In the present study, the social level of each subject has been measured by three criteria: 1. The educational level, in years, which the individual has reached by the time he terminates his formal education (Chapter 3). 2. The occupational class to which the individual belongs (as such classes have been defined in Chapter 3). 3. The occupational class of the individual’s parents at the time that he lived in the parental home.

There are, of course, certain correlations among these three criteria. The educational level ultimately attained determines, to some degree, the occupation which an individual follows. The nature of the correlation is shown in Table 80, where it will be observed that certain educational levels send people into several of the occupational classes, while other educational levels (e.g., the one which includes those who have done graduate work in a university) send nearly all of their members into a single occupational class. It is understandable, therefore, that analyses of sexual behavior made on the basis of ultimate educational level give results which are close to those obtained by the use of a system of occupational classes.

The ultimate educational level attained by an individual shows a limited correlation with intelligence quotients (Lorge 1942). The correlations have been shown to run about 0.66, which may mean that there is some trend for the more intelligent students to continue in school. It also indicates, however, that there are some perfectly intelligent individuals who stop school long before they have reached the limits of their capacities; and that there are some less intelligent individuals who, by dint of work or fortuitous circumstance, manage to get further along in school than their capacities would predicate. Since there may be some correlation between mental capacity and the nature of the occupation which an individual chooses, here is another reason for one’s educational level correlating with his occupational class.

Educational Level as a Criterion. The educational level attained by an individual by the time he terminates his schooling has proved to be the simplest and the best-defined means for recognizing social levels (see Chapter 3 for details of the way in which this criterion has been used). Social level is not necessarily controlled by the amount of schooling that an individual has had, but the amount of schooling does provide a measure of more basic factors which determine one’s social level.

Each level has its own attitudes toward education and, consequently, a high proportion of the persons in any level go to about the same point in school. One group allows its children to terminate their schooling at the eighth grade, or as soon thereafter as the law allows; and in that group there is a general acceptance of the idea that it is a waste of time to send children further along in school when they might be earning wages and contributing to the family income. There is no community action which formalizes these things and some individuals in the community may disagree with the general attitude; but by and large the children hear the group opinion so often expressed that they come to accept it and look forward to the time when they will be allowed to quit school. The individuals in another social level believe that their children should go part way, or perhaps fully, through high school. Going to college is the expected and more or less inevitable thing for the children of other social groups.

Persons who depart from the educational trends of their particular level do so against the community opinion and must be ready to defend themselves for their independent action. This is as true of the professor’s son who decides to go to work at the end of high school as it is of the lower level boy who strikes out for a college education. The boy or girl who departs from the custom is quickly made aware of the fact that he has done something as unusual as wearing the wrong kind of clothing to a social event, or using his table silver in a fashion which is recognized as not good manners in that group. There are no penalties attached to departures from the custom, except those of being made to feel different from the community of which one has previously considered himself a part. Such penalties, however, may control behavior as effectively as though they were physical restraints.

During the past thirty or forty years, there has been a considerable departure of younger generations from the educational levels attained by their parents (Table 106); but almost always this has been in the direction of an increase in the amount of education which the younger persons receive. The idea of a boy or girl being satisfied with less education than his parents had is so abhorrent as to be rarely accepted, and most people are startled when they find an individual case of such regression.

Educational level is a convenient criterion for statistical use because it provides a well-defined, simple figure which is discrete and does not vary in the individual’s lifetime, after he has once finished his schooling. Educational level cannot be used for studying the histories of persons who are still in school, since there is no certainty how far they will go before they finally terminate their education. Educational level is not a satisfactory basis for analysis when the individual changes his social level in the course of his life.

Occupational Class as a Criterion. It has been pointed out (Chapter 3) that a modification of the Chapin and Lloyd Warner schemes of occupational classes (Chapin 1933, Hollingshead 1939, Warner and Lunt 1941, 1942, Warner and Srole 1945) is the basis for the analyses made in the present study. In brief, the following classes are recognized:

0. Dependents

1. Underworld

2. Day labor

3. Semi-skilled labor

4. Skilled labor

5. Lower white collar group

6. Upper white collar group

7. Professional group

8. Business executive group

9. Extremely wealthy group

Occupational classes are more poorly defined than educational levels. Whether an individual belongs in one occupational group or the next not infrequently calls for a judgment in which equally skilled investigators might disagree, although experience in the present research indicates that the judgments are not often more than one occupational class apart. Whether a person is a laborer or a semi-skilled workman, whether he is a semi-skilled or a skilled workman, is not always possible to say; but in most cases it is possible to make a definite classification. Labor unions often define the occupational qualities of their members. Whether a person is a mechanic or a white collar worker is rarely in dispute; but whether the white collar worker belongs to class 5 (the lower white collar group) or class 6 (the upper white collar group), is sometimes more difficult to say. This makes occupational class less precise than educational level for measuring social status.

On the other hand, classifications by occupation probably show a closer correlation with the intangible realities of social organization, since this classification is designed to express the social prestige of the work with which the individual is occupied. The use of occupational class provides the best opportunity, and the only opportunity we have had, to take into account the migrations of an individual from one social level to another within his lifetime; and all of the data given in the next chapter on the relation of such migration to changes in patterns of sexual behavior have been derived from this source. With younger persons who are still at home, it will be recalled that their occupational class is derived from that of their parents (their “ascribed status” as some anthropologists have put it). Younger individuals who are just beginning to establish themselves away from their parents’ home are often involved in more menial occupations, and sometimes in occupations totally different from those which they will ultimately work into (the latter is “the achieved status” in the anthropological terminology); and in this case, occupational class is not a good means of measuring social level.

In this and the next chapter, references to occupational class are usually made as double entries which include the parental class in which the subject originated, and the ultimate class into which the subject independently migrated.

Realities of Social Levels. If there were invariable correlations between education, occupation, and the social organization of our society, “social levels” would be recognized as realities which could easily be delimited. That there is no invariable relation means that such levels are difficult to define; but that does not prove that they are not realities. Quite on the contrary, each child soon becomes aware of the social classification to which he belongs, and learns the boundaries of the group within which he is allowed to move. Each adult lives and moves and does his thinking, to a considerable degree, in accord with the movements and the thinking of other persons who have about the same education and who usually belong to the same occupational class. While there are no sharp boundaries to social levels, there are obstacles to the crossing of those boundaries.

Social levels are hierarchies which are not supposed to exist in a democratic society, and many people would, therefore, deny their existence. In this country we make it a point that there should be no physical barriers nor legal codes which forbid people to move with almost any social group. But while there are, admittedly, a few persons who do move between groups, most persons do not in actuality move freely with those who belong to other levels. Each group recognizes its unity, and its distinction from every other group.

In their occupations or professional activities, persons of different social levels may have a certain amount of daily contact, but their close friends and companions are more likely to come from their own groups. The white collar executive and the office force may work only a few feet away from the factory laborers and mechanics, but they do not really work with them; and in their recreations, after hours, the two groups rarely intermingle. Persons in the one group do not invite persons from the other group to their homes for dinner, or for an evening of conversation, games, or other activities. One’s companions in a card game or around a fireplace are a better test of one’s social position than are one’s business contacts, or even one’s verbalization of his social philosophy.

Within the white collar groups, for instance, there are several levels of social organization. Store clerks and office staffs do not move freely with the business executive groups, outside of their business relations. Persons in professional groups have few intimates among any but the better business and professional men. Doctors may serve persons on both sides of the tracks, but in off hours they visit and find their recreations with other doctors, with some business men, or with college professors. The professional group is not particularly at home with financially successful business men, nor with persons from the Social Register and the top social strata, unless the professional persons themselves happen to have inherited such financial or social backgrounds. These social stratifications are very real, even though they are difficult to define.

Social levels are not necessarily determined by the economic status of an individual. School teachers belong to a white collar class which is generally looked up to by working classes although the working classes may have considerably higher incomes than school teachers ever will have. The fact that the janitor in the school may earn more than the teacher in the same building does not admit him to the social activities of the teacher’s group. Conversely, the lesser salary of the teacher does not give her the entree into the group with which the janitor finds his recreation. For such reasons, neither the current income nor the general economic status of an individual has been used in the present study as a criterion for establishing social levels.

It is, moreover, difficult to know what an income may be worth in a particular instance. An income of a couple of thousand a year would provide a very comfortable living for certain families, although it might spell poverty for the next family whose esthetic and cultural ideals demand much more to satisfy them. Moreover, the dollar has a different purchasing power in different cities and towns in different parts of the country, and it may vary within a single community, depending upon the standards of dress, of entertainment, and of social front which one must maintain in the particular social level to which he belongs. There are economic rating scales which are designed to take these many items into account; but any such scale, in order to be effective, needs to be so detailed that its use in anything but an economic survey is prohibitive. The better economic rating scales take about as long to administer as the entire interview on which the present case history study has been based.

The U. S. Department of Labor has used a job classification (U. S. Dept. Labor 1939) which assigns each individual in accord with the inherent nature of the occupation or profession in which he engages. Specifically, the classification is as follows:

1. Professional and managerial occupations

2. Service occupations

3. Agricultural, forestry, fisheries, and kindred occupations

4–5. Skilled occupations

6–7. Semi-skilled occupations

8–9. Unskilled occupations

There is obviously a certain amount of agreement between this arrangement and the occupational classes used in the present study, i.e., an economic classification does coincide with one like the Chapin and Warner classification which is based on the social prestige of one’s occupation. There are, however, considerable departures between the two systems. For instance, the professional group in the job classification includes college presidents and professors, accountants, actors, newspaper reporters and copy men, all teachers, all social workers, and all trained nurses. The list includes persons who have advanced degrees for several years of university post-graduate work, persons who have had no more than twelfth grade education and, in some cases, those who have had nothing more than grade schooling. Socially the group is not a unit. The persons included do not come together in their strictly social activities. Grade school and high school teachers do not move in the same social groups as college professors. Business managers, who, in many cases, are economically much better off than college professors, are not ordinarily included in the social activities of the professional groups. Trained nurses in most instances have no more than twelve grades of regular schooling. In the same fashion, the several manufacturing groups and the agricultural groups in this classification include persons who are day laborers and persons who are foremen and managers; and these several groups do not mingle socially. Economic and job classifications are set up, of course, to serve a totally different purpose from the one with which a student of the social organization or of the mores is most often concerned. It is unfortunate that so many social studies, including army surveys and most other governmental studies, and even some of the public opinion polls have used this job classification where a social level rating of the sort employed in the present study would have served much better.

The reality of this intangible unit called a social level is further attested by the fact that each group has sexual mores which are, to a degree, distinct from those of all other levels. Most people realize that each group wears clothing of a particular quality and of a particular style, that the styles of their clothing differ especially at social events, that there are differences in food habits, in table manners, in the forms of their social courtesies, in vocabularies and in pronunciations, and in the sorts of things to which they turn for recreation. Among social scientists there has been some recognition of these differences, more particularly in European countries where the social hierarchies are older and more fixed and even legally recognized; but there has been scant recognition of the possibility that the sexual patterns of different social levels might differ in any particular way. The remarkably distinct patterns of sexual behavior which characterize these social levels are the subject of the analyses which follow in the present chapter. It is to be noted that the analyses are made for each criterion, educational level, and occupational class, separately. The close identities of the sexual records thus independently arrived at constitute some of the best evidence yet available that social categories are realities in our Anglo-American culture.

In the present chapter and the one that follows, comparisons of patterns of sexual behavior in different social levels are made for educational levels and for occupational classes of the parent and of the subject. Comparisons are made for three educational groups: grade school, high school, and college. The sample now at hand is not large enough to allow a finer classification. Preliminary analyses on a two-year educational breakdown indicate that a smoothly graded series lies between each of the three groups utilized in this chapter, but the data are insufficient for final publication. We do have a college population which is large enough to break down into finer educational levels, but it became available at too late a date to be included in the present volume.

The occupational classes utilized in the present analyses are 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7, as defined above. Class 0, the dependents, should not rate as a separate group in such analyses, and classes 1, 8, and 9 are not represented by large enough series in the sample to allow the six-way breakdown needed here.

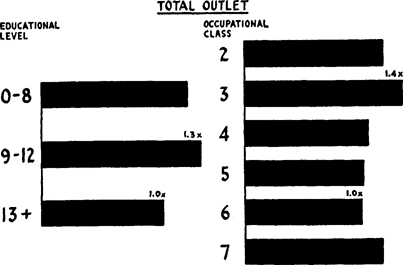

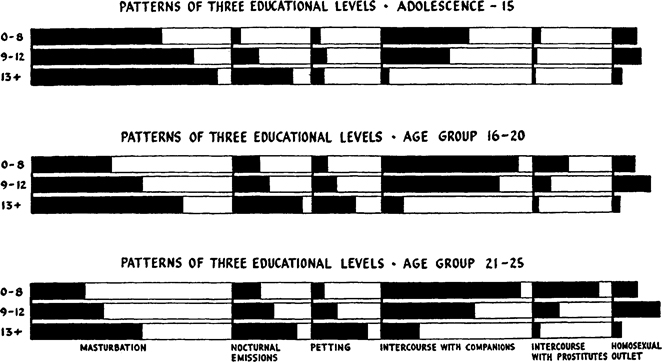

Total Outlet. The frequencies of total sexual outlet vary somewhat with the educational level to which an individual belongs (Table 81, Figure 97), although they do not differ as much as the frequencies for the several sources of outlet. Among single males, at all ages, and whether the calculations are made as means or as medians, the highest total outlets are found among those boys who go into high school but never beyond. This is true while they are still in grade school, while they are in high school, and after they have left high school. While they are in grade school they may associate with boys who will stop school at every level. Nevertheless, during these school years their outlets average 10 to 20 per cent higher than the outlets of the boys who will stop by the eighth grade, and 20 to 30 per cent higher than the outlets of the boys who will ultimately go to college. It is obvious that such differences are not the product of something that the school contributes or fails to contribute, for the same school is supporting three very different patterns of sexual behavior at the same time. The differences must be dependent upon something which the boy has acquired from the community in which he was raised before he went to school, in which he lives while he is attending school, and in which he will continue to live after he quits school; or else these higher frequencies must be dependent upon some physical or physiologic capacity which these particular boys have and which is correlated with the progress of their schooling. Either social or biological factors, or both, might conceivably be operating.

A finer educational breakdown than the one which is shown in Table 81 suggests that the sexually most active group is the one that goes into high school but not beyond tenth grade. Since the laws in many states set a minimum age which must be attained before a boy or girl can stop school, it often happens that there is a considerable exodus of students who attain the age of sixteen (or whatever other age the particular state requires), somewhere about the middle of their high school careers. The boys who leave school at that time may represent a group that is not particularly studious, whatever its mental ability may be, and a group which is impatient of such confinement as the school offers and energetic in its pursuit of physical activity and social contacts. These are, however, merely hypotheses which need further investigation.

The single males who have the lowest frequencies of total sexual outlet are those who belong to the college level. The boys who never go beyond eighth grade in school stand intermediate between the high school and the college groups, as far as the calculations in Table 81 show. It is to be recalled, however, that the breakdown in Chapter 9 indicates that early-adolescent males of this lower educational level actually have higher outlets than any other group in the population, in practically every age period. The over-all averages shown for the grade school males as a group are probably pulled down by the large number of undernourished, physically poor, and, therefore, late-maturing males who are in this class. It includes most of the feeble-minded and mentally lower individuals in the population, and many of these are physically poor and sexually inactive. But the physically well-developed and mentally normal individuals among these grade school boys are more active than the boys of any other educational level.

The social level picture for total outlet among married males is quite the same as for single males. The married males who have the highest total outlet are those who went into high school but not beyond. This is true for every age group between 16 and 40 years of age, and may be true at older ages; but the data beyond 45 become too scant for significant calculation. It is impressive to find that what is true of populations in their teens usually holds true for those same populations at later ages, throughout the life span. Only a very few individuals ever depart from their original patterns.

If the record for total outlet is analyzed on the basis of occupational classes (Table 107), it will be seen that there is as sharp and as consistent a differentiation of groups as there is on the basis of educational level. The highest rates of total outlet are to be found among the males who belong to occupational class 3. This is as true of these males when they are boys living at home with their parents as it is of the same persons at older ages, when they are independent of their parents. On the other hand, males who belong to class 3 have about the same rates of total outlet, irrespective of whether their parents belonged to classes 3, 4, or 5. Since occupational class 3 is the one that includes semi-skilled workers, it contains a great many persons who do not go beyond grade school, and almost none of them go beyond high school (Table 80); and the generalizations based on occupational classes agree very well with the generalizations based upon educational levels. Since the occupational classes are not as sharply defined as educational levels, the frequency series are not quite as consistent as the frequencies shown by the educational breakdown.

Figure 97. Total outlet, by educational level and occupational class

For single males of the age group 16–20. Relative lengths of bars compare mean frequencies for the groups.

The lowest rates of total outlet are to be found in occupational class 4. This is the group which includes the skilled mechanics. The group has very diverse educational backgrounds (Table 80), and in Chapter 11 it will be pointed out that it is the most unstable of all occupational classes. Members of this group often aspire to move into higher levels, and they send a high proportion of their children to college.

In general, the white collar groups (classes 5, 6, and 7) are low in their rates; but of these class 7 shows the highest rates. This is the professional group. It usually has 17 to 20 years of schooling. The group has not been calculated separately in the educational breakdowns made in this volume, and it will be interesting to see what such a breakdown ultimately gives.

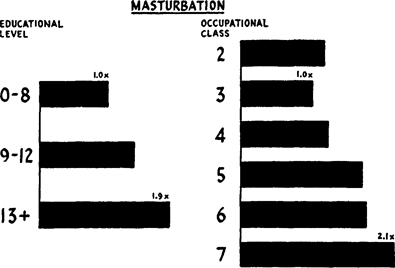

Masturbation. Ultimately, between 92 and 97 per cent of all males have masturbatory experience (Tables 82, 132, Figures 98, 136). The accumulative incidence figures are hardly different for the high school and college groups, but the lower figure (92%) belongs to the grade school group. The highest active incidence between the ages of adolescence and 15 is to be found among the boys who never go beyond high school. In later age periods the college males have the highest incidence.

The highest frequencies of masturbation among single males, in all age periods, are in the college level, whether the calculations are made for total populations or for the active portions of the populations (that portion of the population which is actually utilizing this source of outlet). Between 16 and 20, for instance, masturbation among the single males of college level occurs nearly twice as frequently as it does among the boys who never go beyond grade school, and the differential is still higher in the twenties. This is the great source of pre-marital sexual outlet for the upper educational levels. For that group, masturbation provides nearly 80 per cent of the orgasms during the earlier adolescent years, as against little more than half the outlet (52%) for the lower educational level. In the late teens it still accounts for two-thirds (66%) of the college male’s orgasms, while the lower level has relegated such activity to a low place that provides less than 30 per cent of the total outlet. In all later age periods the relative positions of these groups remain about the same.

Differences in incidences and frequencies of masturbation at different educational levels are even more striking among married males. At the grade school level, there are only 20 to 30 per cent who masturbate in their early marital years, and the accumulative incidence figure climbs only a bit during the later years of marriage. The frequencies are very low. The high school group closely matches the grade school group in this regard. On the other hand, among the married males who have been to college, 60 to 70 per cent masturbate in each of the age periods.

In the grade school group of married males, only 1 to 3 per cent of the total sexual outlet is derived from masturbation. The proportion of the total sexual outlet derived by college males from this source begins at 8.5 per cent during the early years of marriage, and rises to as much as 18 per cent in the later years. The college group stands out as perfectly distinct on this score.

Among occupational classes, the professional group masturbates most frequently (Table 108, Figure 98). This is true whether the persons in that class originate from parental class 7, or whether they come from parental classes 3, 4, or 6. Since essentially all professional persons have an educational rating of 17+ these data from an occupational class analysis are quite in line with the data based on educational levels. The distinctions between occupational classes are, however, even more extreme than the differences between educational levels, as far as masturbation is concerned. Between the ages of 16 and 20, for instance, the males of occupational class 7 have average frequencies of masturbation which run 2.12, 2.17, 2.21, and 1.60 per week, varying with the parental occupational class from which they came. The corresponding groups of occupational classes 2 and 3 have masturbatory frequencies which run very close to 1 per week—sometimes a bit more, sometimes a bit less in the various breakdowns. The educational breakdown for the same age period shows the college level masturbating with frequencies which are about 1.9 times the frequencies of the grade school males. Differences in the frequencies of the occupational classes are more nearly of the order of 2.2 to 2.5. Differences in attitudes on masturbation, pre-marital intercourse, and prostitution are among the most marked of all the distinctions between social levels, and this is true whether the calculations are made by educational levels or by occupational classes.

Figure 98. Masturbation, by educational level and occupational class

For single males of the age group 16–20. Relative lengths of bars compare mean frequencies for the groups. Note similarity of data based on educational levels and data based on occupational classes.

The professional males who originated in parental class 5, becoming members of class 7 as a result of their university training, have masturbatory rates which are 25 per cent lower than those of class 7 males who are derived from any other source. It is a striking situation for which we have no explanation at this time.

Nocturnal Emissions. Masturbation may appear to be volitional behavior, and one may question whether the pattern in masturbation represents the individual’s choice, rather than something that has been imposed upon him by the mores of his group. It is, therefore, particularly interesting to find that there are still greater differences between educational levels in regard to nocturnal emissions—a type of sexual outlet which one might suppose would represent involuntary behavior.

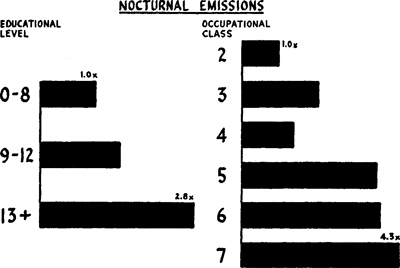

Figure 99. Nocturnal emissions, by educational level and occupational class

For single males of the age group 16–20. Relative lengths of bars compare mean frequencies for the groups. Note similarity of data based on educational levels and data based on occupational classes.

Nocturnal emissions occur most often in that segment of the population that goes to college (Table 83, Figure 99). Among males of the college level the emissions begin at earlier ages than among males of lower educational levels. About 70 per cent of the boys who will go to college have such experience by age 15, whereas only about 25 per cent of the grade school group has started by then. Between 16 and 20 years of age, 91 per cent of the single males of the college level experience nocturnal emissions, while only 56 per cent of the lower level boys have such experience in the same period. The active incidence figures are highest for the college males in every other age group. Ultimately, nearly 100 per cent of the better educated males have such experience, whereas the accumulative incidence figure is only 86 per cent for the high school group, and only 75 per cent for the grade school group.

Between adolescence and age 15, upper level males average nocturnal emissions nearly seven times as frequently as the boys of lower educational levels. Between 16 and 20 the frequencies among the upper level males are nearly three times those for the lower level, if the whole population is involved in the calculation. For the active populations the frequencies for the college group are still twice as high. About the same differences hold in the older age periods, at least up to 30 years of age.

Figure 100. Petting to climax, by educational level and occupational class

For single males of the age group 16–20. Relative lengths of bars compare mean frequencies for the groups. Note similarity of data based on educational levels and data based on occupational classes.

In marriage there are only minor differences between the educational levels in frequencies of nocturnal emissions, but the highest incidence figures at all ages are to be found among the males who have gone to college. Before marriage, college-bred males draw between 12 and 15 per cent of their outlet from nocturnal emissions, while the males of lower educational levels draw only 5 or 6 per cent of their outlet from that source. After marriage the college males draw 3 to 6 per cent of their outlet from emissions, but the lower educational levels never draw over 3 per cent from that source.

While it is clear that higher frequencies of nocturnal emissions are correlated with more extended educational histories, the explanation of this correlation is not so apparent. It is evident that nocturnal dreams are not the product of the education in itself, for two groups of boys of different social levels, working together in the same class in grade school or in high school, may have totally different histories of emissions. Is this a measure of some difference in the psychologic or physiologic capacities of the two groups which correlates in some way with factors which determine their educational careers? These are problems which the physiologist and the psychologist will want to investigate in more elaborate detail.

We do know that the frequencies of nocturnal dreams show some correlation with the level of erotic responsiveness of an individual. The boys of lower level are not so often aroused erotically, nor aroused by so many items as the boys from the upper educational levels. Nocturnal dreams may depend upon an imaginative capacity, in something of the same way that daytime eroticism is dependent upon the individual’s capacity to project himself into a situation which is not a part of his immediate experience. It may be that the paucity of overt socio-sexual experience among upper level males accounts both for their daytime eroticism and for their nocturnal dreaming.

The record on frequencies of nocturnal emissions in different occupational classes is fully as striking as the record based on an educational breakdown, and the two bodies of data lie in exactly the same direction (Table 109, Figure 99). The lowest average frequencies of nocturnal emissions, averaging not more than 2 or 3 per year, are to be found among the males of occupational class 2, which is the group that includes the day laborers, and the frequencies are only a bit higher for the semi-skilled workmen of occupational class 3. The frequencies for occupational classes 6 and 7 (the college and graduate school groups), on the contrary, run nearer once in 2 weeks at practically every age level and irrespective of the nature of the parental occupational class from which these individuals come. This means that there are 10 to 12 times as frequent nocturnal emissions among males of the upper occupational classes as there are among males of the lower classes.

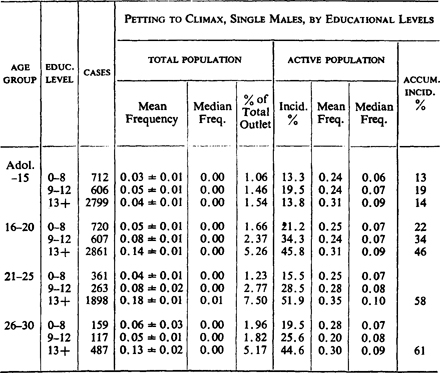

Heterosexual Petting. Petting is pre-eminently an occupation of the high school and college levels. For all social levels, it may begin in high school or even before; but from 16 years of age, the males and the females who are most often involved are the ones who go into high school or ultimately into college (Table 84, Figure 100). About 92 per cent of the males of the high school and college levels engage in at least some kind of petting prior to marriage, and nearly as many (88%) of the grade school group has such experience. These figures are not very far apart, but there are greater differences in the limits to which the petting techniques go in these several groups. In general, males of the grade school and high school levels are more restricted in their petting behavior than males of the college level.

Unfortunately, the data secured in this study do not allow a statistical calculation for each degree of petting experience, but there are precise data on the frequencies of petting which extends to the point of orgasm (Table 84, Figure 100). In the pre-marital histories of college males, about 61 per cent reach orgasm by that means. It is only about 32 per cent of the high school males who ever have such experience, and only about 16 per cent of the grade school group.

Table 84. Heterosexual petting to climax, and educational level

In regard to the frequencies of petting to climax, the differences between educational levels are even more extreme. In the later teens, this source provides nearly three times as frequent orgasm for the males who go to college; and between 21 and 25, there is nearly 5 times as much orgasm from this source for the college males as there is for the males who never go beyond grade school. The lower level males derive something between 1 and 2 per cent of their total outlet from petting in their pre-marital years. The college males derive between 5 and 8 per cent of their outlet from that source.

Analyses of the record by occupational classes confirm the statement made above that petting is most characteristic of the upper social levels. The differences by occupational class (Table 110, Figure 100) are not notable in the early adolescent years, but they become greater between 16 and 20, at which age classes 6 and 7 pet to the point of climax twice as often as classes 2 or 3. In the early twenties there is a 3 to 1 difference between the two ends of the occupational scale, and the distinctions are more or less true irrespective of the occupational classes of the parents.

Pre-marital Intercourse. Pre-marital intercourse may be had either with companions or with prostitutes. In every social level coitus with girls who are not prostitutes is more frequent. In younger age groups there is a 10 to 1 or still higher difference in favor of the non-prostitutes. In older age groups, males of the lower educational level who are not yet married turn to prostitutes more often than they did when they were younger; but non-prostitutes still provide a larger part of the coitus. At the college level, contacts with companions exceed the prostitute relations by some factor which lies between 20 and 100 in every age group, including the older groups.

Pre-marital intercourse, whatever its source, is more abundant in the grade school and high school levels, and less common at the college level (Tables 85–87, Figures 101–102). Even in the period between adolescence and 15 the active incidence includes nearly half (48% and 43%) of the lower educational groups, but only 10 per cent of the boys who will ultimately go to college. In the later teens, 85 per cent of the grade school group and 75 per cent of the high school group is having pre-marital intercourse, while the figure for the college group is still only 42 per cent. In later years the differentials are not so great but, compared with the grade school group, it is still only about two-thirds as many of the college males who have such intercourse.

The accumulative incidence figures for pre-marital intercourse show much the same differences. About 98 per cent of the grade school level has experience before marriage, while only 84 per cent of the high school level and 67 per cent of the college level is involved (Table 136, Figure 145).

The frequency figures show still greater differences between educational levels. In the age period between 16 and 20, the grade school group has 7 times as much pre-marital coitus as the college group. There is not much drop in the differential even in the older age groups. The mother who is afraid to send her boy away to college for fear that he will be morally corrupted there, is evidently unaware of the histories of the boys who stay at home. Moreover, nearly half of the males who have intercourse while in college had their first experience while they were still at home, before they started to college (Table 136, Figure 145). Varying with the age period, the college group derives 4 to 21 per cent of its pre-marital outlet from intercourse; the high school group derives 26 to 54 per cent of its outlet from that source; but the grade school group depends on coitus for 40 to 70 per cent of its total pre-marital outlet.

The number of college-bred males who have some pre-marital intercourse is high enough to surprise many persons, but the frequencies with which they have it are very much lower than anywhere else in the population. Between a third and a half of the males at college level have intercourse only once or twice, or half a dozen times, or a matter of two or three times a year for a few years before they marry. It is about 15 per cent of the college males who have pre-marital intercourse with weekly regularity for any period of years before marriage. A good many college males never have pre-marital intercourse with more than the one girl whom they subsequently marry, and very few of them have pre-marital intercourse with more than half a dozen girls or so. College males are very slow in arriving at their first pre-marital intercourse (Figure 146), and a comparison of the accumulative incidence curves (Table 136, Figure 146) indicates that, on an average, they do not have their first experience until five or six years after the lower level males start.

Figure 101. Total pre-marital intercourse, by educational level and occupational class

For single males of the age group 16–20. Relative lengths of bars compare mean frequencies for the groups. Note similarity of data based on educational levels and data based on occupational classes.

The pre-marital coital pictures for the grade school and high school groups are much alike. They both differ from the college group in starting their intercourse at a much earlier age—in many cases in pre-adolescence, and in a large number of cases coincidentally with the onset of adolescence. Within two or three years after the onset of adolescence nearly all of those who will ever be involved have started heterosexual relations. Ultimately, 10 to 15 per cent more of the grade school group is involved than of the high school group.

As analyzed by occupational classes, pre-marital intercourse is much more frequently had by males of class 3, which is the group of semi-skilled workmen (Table 111, Figure 101). Between adolescence and 15 years of age there may be 15 times as much intercourse among males of class 3 as there is among the boys who will ultimately go to college and whose occupational ratings will ultimately be in class 6 or 7. If the parental occupational class is 5 (the lower white collar group), there is 122 times as much premarital intercourse among the boys who regress to class 3 as there is among those boys who will ultimately go into the professional group. Between 16 and 20, the differences between the extreme groups are somewhat less, but the boys who will end up in occupational class 3 are still having intercourse 4 to 9 times as often as the boys who will move into occupational classes 6 and 7. Even during the twenties, when intercourse becomes more common at the upper levels, there is still 4 times as much of it among the males of occupational class 3.

The males of occupational class 2 have high frequencies of pre-marital intercourse at all age levels, but they do not rate as high as the males of class 3. Just as was pointed out for the lower educational levels, this lower rate of the lowest class is certainly due to the higher incidence of feeblemindedness, to the low physical state, and to the low social prestige of many of the individuals in the group. It is quite possible that this lower occupational class includes some groups who have very much higher rates than the average for the whole class. They are probably the lower level boys who became adolescent first (Chapter 9). Since class 2 as a group is quite unrestrained sexually, any male in the group who does have any amount of sexual drive would be likely to have relatively high frequencies of pre-marital intercourse.

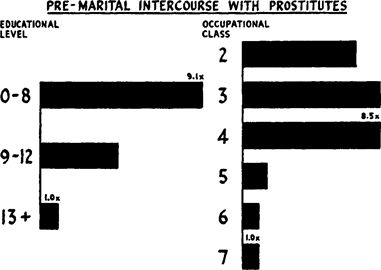

Intercourse with Prostitutes. Among those males who are not married by age 25, pre-marital intercourse with prostitutes has been had by 74 per cent of the grade school level, and by 54 per cent of the high school group, but by not more than about 28 per cent of those who belong in the college level (Table 87, Figure 102). These striking differences between educational levels were as true in a past generation as they are in the present day (Chapter 11). The active incidence figures in each of the five-year periods indicate that lower level males start relations with prostitutes at a much earlier age, and that three to four times as many of them are having intercourse with prostitutes in each age period.

The percentage of the total sexual outlet which is derived by unmarried males from intercourse with prostitutes steadily rises in all educational levels with advancing age. Between 16 and 40 the percentage for males in the grade school level rises from about 6 to 23 per cent. For the high school level the figures at the same ages rise from less than 3 per cent to about 11 per cent; and for the college males they start at a fraction of 1 per cent and rise no higher than 3 per cent in the later age periods. At 16 years of age, the grade school males derive seven times as much of their outlet from prostitutes as the college males do; and high school males get three or four times as much of their outlet from prostitutes as college males get from that source. Among those who are still unmarried between 31 and 35, the lower level individuals have 36 times as much contact with prostitutes as the college males do.

Figure 102. Pre-marital intercourse with prostitutes, by educational level and occupational class

For single males of the age group 16–20. Relative lengths of bars compare mean frequencies for the groups. Note similarity of data based on educational levels and data based on occupational classes.

Except for these lower level males of older ages, the actual frequencies of contacts with prostitutes are relatively low. In spite of some opinion that the college male depends primarily on paid contacts for his pre-marital socio-sexual experience, this is the least significant part of all his sexual activities (except for the incidental outlet that he derives from intercourse with animals). The mean frequency of prostitute contacts for the entire male population of all ages and of all educational and occupational groups is 0.093 per week, or approximately 5 times per year. For the lower level groups it may average as high as 0.50 per week (25 times per year) between 31 and 35 years of age. For the unmarried college males taken as a group, it never averages higher than 0.08 per week (4 times per year) in any age period.

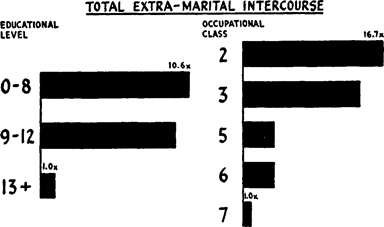

Extra-marital intercourse with prostitutes is a still less important item, at all social levels. In any age period, it never constitutes more than 1.5 per cent of the outlet of the grade school level, 1.7 per cent of the outlet of the high school level, and 0.5 per cent of the outlet of the married males of college level.

Figure 103. Extra-marital intercourse, by educational level and occupational class

For married males of the age group 21–25. Relative lengths of bars compare mean frequencies for the groups. Note similarity of data based on educational levels and data based on occupational classes.

A breakdown of the population by occupational classes shows that most of the high frequencies of intercourse with prostitutes occur in occupational classes 2 and 3, which are the day labor and semi-skilled workmen groups. The skilled workmen of class 4 show quite as high frequencies in those few instances where we have sufficient material to make calculations. Frequencies even in the lower occupational classes are not more than once in 6 weeks in any particular age group; but the frequencies are rarely more than once or twice in a year in occupational classes 5, 6, and 7. These rates, which represent averages for total populations, are, of course, much lower than the rates for the active members of those populations; but if the analyses are made on the active populations, the differences are still 2 to 1 in most cases, and in some cases nearly 8 to 1, with the higher frequencies occurring in occupational classes 2 and 3. This breakdown by occupational classes is a strict parallel to the breakdown by educational levels.

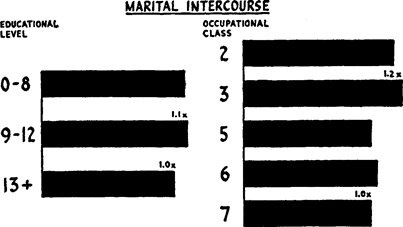

Marital Intercourse. At all social levels, practically one hundred per cent of the married males have intercourse with their wives (Table 88, Figure 104). There are a few exceptions among the aged, among persons who are married for only brief periods of time, among spouses between whom there are insurmountable incompatibilities on questions of sex, in an occasional case where one or both partners are completely homosexual, or in a very few cases of persons who are religiously much restrained. There are exceedingly few such cases of abstinence, and the number is too small to show any trend by social levels.

There are social differences, however, in regard to the percentage of the total sexual outlet which is derived from marital intercourse. In the age period between 16 and 20, among males of the grade school level, only about 80 per cent of the total sexual outlet comes from marital intercourse, while extra-marital intercourse accounts for another 11 per cent of the total outlet (Table 86, 97, Figure 103). However, the portion of the outlet coming from marital intercourse in this grade school group rises to approximately 90 per cent in the late forties and early fifties. Among males of the high school group, marital intercourse in the early years accounts for 82 per cent, but rises to 91 per cent of the total outlet by the late forties. For the college level, marital intercourse starts out as a higher portion of the total outlet—nearly 85 per cent; but it drops steadily through the successive years until by the middle fifties it accounts for only 62 per cent of the outlet of these males (Table 97, Figure 133). In comparison with males of the college level, males of the grade school level, in their middle fifties, derive 26 per cent more of their total outlet from intercourse with their wives.

In the course of his marriage, the outlet of the married male of the college level has increasingly included masturbation and nocturnal dreams and, strikingly enough, extra-marital intercourse. On the other hand, the lower level males never have much masturbation in their marital histories, and the amount becomes less in the later years. During their teens and early twenties, lower level males find a considerable outlet in extra-marital intercourse, but with the advancing years they become increasingly faithful to their wives. In short, lower level males take 35 or 40 years to arrive at the marital ideals which the upper level begins with; or, to put it with equal accuracy, upper level males take 35 to 40 years to arrive at the sexual freedom which the lower level accepts in its teens. Some persons may interpret the data to mean that the lower level starts out by trying promiscuity and, as a result of that trial, finally decides that strict monogamy is a better policy; but it would be equally correct to say that the upper level starts out by trying monogamy and ultimately decides that variety is worth having. Of course, neither interpretation is quite correct, for the factors involve differences in sexual adjustment in marriages at the different levels, as well as the force of the mores which lie at the base of most of these class differences.

Figure 104. Marital intercourse, by educational level and occupational class

For married males of the age group 21–25. Relative lengths of bars compare mean frequencies for the groups. Note similarity of data based on educational levels and data based on occupational classes.

Unfortunately, the available data are not sufficient for any detailed analysis of the frequencies of marital intercourse by occupational classes. There are only a few instances where comparisons can be made. It is rather notable, however, that even in those instances there is a differentiation in the direction of slightly higher frequencies and higher percentages of the total outlet derived from marital intercourse among those males who belong to class 6, and slightly lower figures for class 7. If the calculations are based upon the active members of the population, the differences between these two classes are a bit more marked.

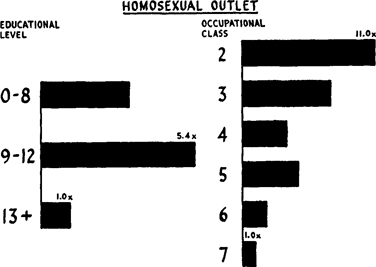

Homosexual Contacts. Among single males homosexual relations occur most often in the group that goes into high school but not beyond, and least often in the group that goes to college.

The active incidence figures for single males of the high school group begin at 32 per cent in the early adolescent years and rise to 46 per cent by age 30 (Table 90, Figure 105). The accumulative incidence figure is 54 per cent for those who are not married by age 30. Allowing for the fact that males of this high school group usually marry early, it is something less than 50 per cent which has experience in the homosexual, to the point of orgasm, between the onset of adolescence and marriage. It should be noted that a high proportion of the males in the Army, Navy, Merchant Marine, CCC camps, and other such organizations belong to this educational level. During the age periods in which these men are actually in these services, about 40 per cent have at least incidental homosexual relations. After marriage, the high school level continues to have homosexual relations in something between 9 and 13 per cent of the cases. The active incidence figures during marriage gradually drop in successive age periods.

Among single males of the high school level, frequencies in the homosexual (for the total group) average about once in three weeks between the ages of adolescence and twenty. The averages for that portion of the population which is actually having experience range from a little under once a week in the teens, to about three times in two weeks if the males are still unmarried by their thirties. In early adolescence this high school group draws nearly 9 per cent of its total outlet from the homosexual, and the percentage increases in subsequent age periods until it accounts for a quarter of the total sexual outlet of the high school males who are still unmarried at age 30. While considerable attention has been given to the amount of sexual activity which males in general, and this high school group in particular, have with prostitutes, comparisons of Tables 87 and 90 will show that the sexual outlet which is provided by homosexual relations amounts to three or four times the outlet which is provided by prostitutes.

Among the males who ultimately go to college, homosexual relations are less frequent, but they are still a material part of the total sexual picture. Between adolescence and 15 years of age, 21 per cent of the single males of the college level is actively involved, at least in incidental experience to the point of orgasm. The active incidence figure drops to 17 per cent by age 30. The number of college-bred males who ultimately have experience is 40 per cent, if they are not married by age 30.

Frequencies for the college males are much lower than for any of the other educational levels. They average only about once in ten weeks for the population as a whole, and less than once in two weeks for the active population. For those males who are not yet married by 30, the mean frequencies rise to as much as 1.3 per week for the active portion of the population. Only about 3 per cent of the outlet of the college males is derived from the homosexual between adolescence and age 25, but in the next age period they derive nearly 9 per cent of their outlet from such contacts.

After marriage only 2 or 3 per cent of the college males engage in homosexual relations, according to the histories that are now available. There is no doubt, however, that this is one of the points on which there has been considerable cover-up, and it is certain that a good many married males who are having homosexual relations have deliberately avoided contributing their histories to this study. The 3 per cent incidence figure and the low frequencies shown here are, consequently, absolute minima, and they should be increased by some unknown quantity if they are to represent the reality.

The data on the incidence, frequency, and total significance of homosexual relations among grade school males are intermediate between the data for the high school and the college males. In any single age period, about one-fourth of all the males of grade school level have some homosexual relations. This is true for all the years between adolescence and 30. Ultimately, about 45 per cent of the grade school group is involved. Frequencies of homosexual contacts are about once in four weeks for the group taken as a whole, and nearly once a week for those who are actively involved between the ages of 16 and 20. In marriage, the grade school group continues its homosexual relations in 10 per cent of the cases, but the incidence figures drop to about 3 per cent by age 45. The frequencies of homosexual contacts for homosexually active married males of the grade school level begin at about 1.4 per week and drop to a few times per year, or once in a year or two, in the older groups.

A breakdown of the homosexual data for the several occupational classes does not show marked or consistent differences between occupational classes 2, 3, and 5 (Table 114, Figure 105). On most items of sexual activity class 5 is closer to classes 6 and 7, but in regard to the incidences and frequencies of the homosexual, it is closer to the semi-skilled and skilled labor groups. The active incidence figures for homosexual contacts among the lower occupational classes may be as high as 35 or 40 per cent in different groups at particular age periods, but they never go higher than 14 per cent for the males of class 7, except during the period of earliest adolescence for that portion of class 7 which originates from parental class 5.

Figure 105. Homosexual outlet, by educational level and occupational class

For single males of the age group 16–20. Relative lengths of bars compare mean frequencies for the groups.

The frequencies of homosexual activity among the males of class 6 are a bit lower than the frequencies in the lower occupational levels. Class 7 is the most distinct. Its frequencies are very much below those of every other occupational class. In practically every age group, and irrespective of the parental occupational class from which these class 7 males may have come, the frequencies average only about one-fourth or one-fifth of those for the lower occupational classes. If the calculations are made only for those males who do become actively involved, the mean frequencies for class 7 are still only half as high as the mean frequencies for the active males of classes 3 and 5. Males of occupational class 6 are intermediate between the males of the lower levels and those of class 7.

The situation portrayed by frequencies in the homosexual is more or less paralleled by the calculations showing the percent of the total sexual outlet which is derived from this source in each of the occupational classes. An average of 10 per cent or more of the total sexual outlet may be derived from the homosexual by males of classes 2 and 5, while among males of class 7 the average of the total outlet which is so derived is never more than 2 per cent. The males of class 6 are rather intermediate in this regard, or more nearly approach the males of class 5 in deriving upward of 10 per cent (in one group slightly more than 10 per cent) of their orgasms in contacts with other males.

Animal Intercourse. Intercourse with animals other than the human is almost entirely confined to males raised in rural areas. Only an occasional contact is had by city boys, unless they visit farms in vacation periods. Consequently, averages of animal contacts for the total American population are so low that they cannot be calculated with an accuracy which means anything in terms of the actualities of human behavior. For the rural males who are actively involved in such contacts, animal intercourse is more significant (Table 91).

Table 91. Animal contacts, as related to educational level

The active population is almost wholly rural and the active frequencies are essentially those for that portion of the rural population which has animal contacts. Median frequencies for the total populations are uniformly 0.00.

The accumulative incidence figures for animal intercourse go to about 14 per cent for the farm boys who do not go beyond grade school, to about 20 per cent for the group which goes into high school but not beyond, and to 26 per cent for the males who will ultimately go to college. The boys of college level who are ever involved in animal intercourse number nearly twice as many, relatively, as the boys who never go beyond grade school.

On the other hand, the boys of lower educational levels who are actually involved are the ones who have the highest frequencies in animal contacts (Table 91). For them the frequencies average close to once in two weeks, plus or minus. The frequencies for the boys of the college level who are actually having any animal contacts average nearer once in three weeks.

In addition to differences in frequencies and sources of sexual outlet, social levels differ in their attitudes on other matters of sex. Their sources of erotic interest, attitudes toward nudity, and techniques utilized in coitus are the items on which we have sufficient data to warrant some treatment here.

Sources of Erotic Arousal. The upper level male is aroused by a considerable variety of sexual stimuli. He has a minimum of pre-marital or extra-marital intercourse (Tables 96, 97). The lower level male, on the other hand, is less often aroused by anything except physical contact in coitus; he has an abundance of pre-marital intercourse, and a considerable amount of extra-marital intercourse in the early years of his marriage. How much of this difference is simply the product of psychologic factors and how much represents a community pattern which can be properly identified as the mores, it is difficult to say. The very fact that upper level males fail to get what they want in socio-sexual relations would provide a psychologic explanation of their high degree of erotic responsiveness to stimuli which fall short of actual coitus. The fact that the lower level male comes nearer having as much coitus as he wants (Table 92) would make him less susceptible to any stimulus except actual coitus.

The higher degree of eroticism in the upper level male may also be consequent on his greater capacity to visualize situations which are not immediately at hand. In consequence, he is affected by thinking about females, and/or by seeing females or the homosexual partner, by burlesque shows, obscene stories, love stories in good literature, love stories in moving pictures, animals in coitus, and sado-masochistic literature. Upper level males are the ones who most often read erotic literature, and the ones who most often find erotic stimulation in pictures and other objects. None of these are significant sources of stimulation for most lower level males, who may look on such a thing as the use of pictures or literature to augment masturbatory fantasies as the strangest sort of perversion.

While these group differences may be primarily psychologic in origin, there is clearly an element of tradition involved. Each community more or less accepts the idea that there will be or will not be erotic arousal under particular sorts of circumstances. The college male who continuously talks about girls does so with a certain consciousness that the other persons in his group are also going to be aroused by such conversation, and that they accept such arousal as natural and desirable. The homosexual male, and the heterosexual male who does not approve of such deliberately induced eroticism, considers this public display of elation over females as a group activity which is more or less artificially encouraged. The lower level male who talks about girls quite as frequently, or even more so, is less often aroused by such talk and may be inclined to consider a listener who is so aroused as somewhat aberrant. There is an element of custom involved in these styles of erotic response.

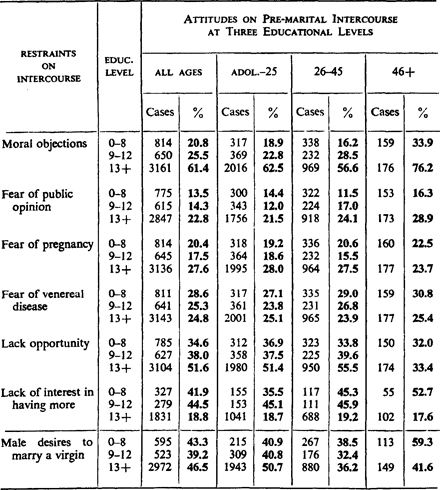

Table 92. Attitudes on pre-marital intercourse, at three educational levels

Nudity. In many cultures, the world around, people have been much exercised by questions of propriety in the public exposure of portions or the whole of the nude body. There are few matters on which customs are more specific, and few items of sexual behavior which bring more intense reactions when the custom is transgressed. These customs vary tremendously between cultures and nations, and even between the individual communities in particular countries. The inhabitant of the Central American tropics has one custom, the Indian who comes down from his mountain home to trade in the lowland has totally different customs. There is neither rhyme nor reason to the custom—there is nothing but tradition to explain it. The mountain Indian of the warmer country of Southern Mexico is thoroughly clothed, the mountain Indian of the coldest part of Northern Mexico is more completely nude than the natives of the hottest Mexican tropics. But there are probably no groups in the world who are free of taboos of some sort on this point. The history of the origin of clothing is more often one of taboos on nudity than a story of the utility of body coverings.

The English are more or less justly reputed to be the most completely clothed people in the world, and Americans have been slow in breaking away from the English tradition. The American visitor to foreign lands is often amazed at the exposure which is allowed in some other cultures, and he criticizes it on moral grounds. The nudity of the French burlesque is ascribed to the “low morality” of Frenchmen as a group; and although an approach is made to the same sort of display in American burlesque, the institution here does not achieve the same free acceptance of complete nudity which the original French has. The German nudist movement is assumed by the average American to be immoral in intent, and its counterpart in this country survives only after considerable public discussion and continual wrangling in court over the obscenity of such activity. Although Anglo-American law has tried for six or seven centuries to define indecent exposure, there is no legal agreement on the decency or indecency of nude art, nor on the rights of art schools, photographers, magazines, and books to portray the nude human form. Public sentiment, backed by sporadic police action, has dictated the styles of bathing suits, from the gay nineties down to the present. It is only within the last decade or two that the male’s right to appear in swimming trunks without tops has been established for public swimming beaches and pools.

More definite limits may be set on nudity than on more overtly sexual activities. The kissing which is commonplace in American films is considered most immoral in some of the foreign countries to which the films are distributed. A completely nude art production may be shown in a Latin American moving picture theatre to an audience which takes the film complacently, for its artistic value, although it will hiss the next picture off the screen because it contains a Hollywood kissing scene.

The acceptance of nudity may even vary with the hour and the place of the exposure. The costume which is accepted on the swimming beach is strictly forbidden in most other places. In the middle of the day, the female may safely expose her arms in public, although she is then limited in regard to the exposure of her back. At the formal affair in the evening, she may expose the whole of her back, but she is then most proper if she covers her arms with long gloves. In a Latin American tropic town, inside a public building, there may be considerable objection when one rolls his shirt sleeves to the elbow, even on the hottest summer day; but out of doors both men and women may go stripped to the waist through the streets of the town, and all of them may come together for nude bathing in the nearby stream. It would require a considerable treatise to portray the reactions of the peoples of the world to nudity, and a larger treatise to explain the origins of those customs.

Most amazing of all, customs in regard to nudity may vary between the social levels of a single community. In our American culture, there is a greater acceptance of nudity at upper social levels, and greater restraint at lower social levels. Compared with previous generations, there is a more general acceptance of nudity in the upper social level today (Table 95). There is an increasing amount of nudity within the family circle in this upper level. There is rather free exposure in the home for both sexes, including the parents and the children of all ages, at times of dressing and at times of bathing. Still more significant, there is an increasing habit among upper level persons of sleeping in partial or complete nudity (Table 95). This is probably more common among males, though there is a considerable number of upper level females who also sleep nude. Among the males of the college level, nearly half (41%) frequently sleep nude, about one-third (34%) of the high school males do so, but only one-sixth (16%) of the males of the grade school level sleep that way.

Finally, the upper level considers nudity almost an essential concomitant of intercourse. About 90 per cent of the persons at this level regularly have coitus nude (Table 95). The upper level finds it difficult to comprehend that anyone should regularly and as a matter of preference have intercourse while clothed. This group uses clothing only under unusual circumstances, or when variety and experimentation are the desired objectives in the intercourse. On the other hand, nude coitus is regularly had by only 66 per cent of those who never go beyond high school, and by 43 per cent of those who never go beyond grade school.

This intercourse with clothing is not a product of the inconveniences of the lower level home, nor is it dependent upon the difficulties of securing privacy in a small home, as too many sociologists have gratuitously assumed. It is primarily the product of the lower level’s conviction that nudity is obscene. It is obscene in the presence of strangers, and it is even obscene in the presence of one’s spouse. Some of the older men and women in this group take pride in the fact that they have never seen their own spouses nude.

Many persons at this level strictly avoid nudity while dressing or undressing. They acquire a considerable knack of removing daytime clothing and of putting on night clothing, without ever exposing any part of the body. This is less often true of the younger generation which has been exposed to the mixture of social levels encountered in the CCC camps, the Y.M.C.A., and the Army and the Navy. Exposure of the upper half of the male body on swimming beaches started as an upper level custom, but the democracy of the public beach has fostered a much wider acceptance of nudity among lower social levels today. Compare the three generations of the educational level 0–8 in Table 95. Younger males, even of the laboring groups, are often seen at work, out of doors, in public view, while stripped to the waist; but older males of the same social level still keep their arms covered to the wrist, even on the hottest of days and while engaged in the most uncomfortable of jobs. These inroads on the traditions against nudity are reflected in the sleeping and coital customs of younger persons of these lower levels, but the older members of these groups still observe the traditions. There are some cases of lower level males who have been highly promiscuous, who have had intercourse with several hundred females, and who emphasize the fact that they have never turned down an opportunity to have intercourse except “on one occasion when the girl started to remove her clothing before coitus. She was too indecent to have intercourse with!”

Manual Manipulation. At upper social levels there may be considerable manual petting between partners, particularly on the part of the male who has been persuaded by the general talk among his companions, and by the codification of those opinions in the marriage manuals, that the female needs extended sensory stimulation if she is to be brought to simultaneous orgasm in coitus. Upper level petting involves the manual stimulation of all parts of the female body.

Manual manipulation of the female breast occurs regularly in 96 per cent of the histories of the married males of the upper level, and manual manipulation of the female genitalia is regularly found in about 90 per cent of the histories (Table 93). The upper level believes that this petting is necessary for successful coital adjustment; but preliminary calculations indicate that the frequency of orgasm is higher among lower level females than it is among upper level females, even though the lower level coitus involves a minimum of specific physical stimulation (Table 93).

The manual manipulation of the female breast occurs in only 79 per cent of the married male histories at lower levels, and the manipulation of the female genitalia occurs in only 75 per cent of the cases (Table 93). Even when there is such stimulation, it is usually restricted in its extent and in its duration. The lower level female agrees to manipulate the male genitalia in only 57 per cent of the cases. The record is, therefore, one of more extended pre-coital play at the upper levels, and of a minimum of play at the lower levels. Many persons at the lower level consider that intromission is the essential activity and the only justifiable activity in a “normal” sexual relation.

Oral Eroticism. Many persons in the upper levels consider a certain amount of oral eroticism as natural, desirable, and a fundamental part of love making. Simple lip kissing is so commonly accepted that it has a minimum of erotic significance at this level. The college male may expect to kiss his date the first time they go out together. Most college students understand there will be good night kisses as soon as their dating becomes regular. Many a college male will have kissed dozens of girls, although he has had intercourse with none of them. On the other hand, the lower level male is likely to have had intercourse with hundreds of girls, but he may have kissed few of them. What kissing he has done has involved simple lip contacts, for he is likely to have a considerable distaste for the deep kiss which is fairly common in upper level histories.