In the broadest sense, the mores may become systems of morals and systems of morals are formalizations of the mores. It is no accident that the two words, mores and morals, stem from the same Latin root. Throughout history all peoples have defended their mores as stoutly as they have defended their religions, and their moral systems have determined the custom of the land. Sexual mores and systems of sexual morality are no exceptions to this general rule.

This means that there is nothing in the English-American social structure which has had more influence upon present-day patterns of sexual behavior than the religious backgrounds of that culture. It would require long research and a complete volume to work out the origins of the present-day religious codes which apply to sex, of the present-day sex mores, of the coded sex laws, and to trace the subtle ways in which these have influenced the behavior of individuals (Northcote 1916, Angus 1925, May 1931). Our particular systems certainly go back to the Old Testament philosophy on which the Talmud is based, and which was the philosophy of those Jews who first followed the Christian faith. In many details, the proscriptions of the Talmud are nearly identical with those of our present-day legal codes governing sexual behavior. Baek of the Jewish formulations were the older codes of such peoples as the Hittites (Barton 1925), Babylonians (Harper 1904), Assyrians (Barton 1925), and Egyptians (Budge 1895), all of whom probably had a part in shaping the sexual systems of the early Jews. Several Roman ascetic cults had a considerable influence on the asceticism of the early Christian church, and Greek philosophy in a more general way contributed to Christian ethics, both in the early days of the church and in the middle ages.

Ecclesiastic law governing sexual matters set the pattern from which the sex law of English common courts was derived between the twelfth and fifteenth centuries, and irrespective of the specific statutes which the several states have written to control sexual behavior, the decisions of American criminal courts today are primarily based upon the precedents of those common courts. This is no place to work out the details of the historic development, but it is important at this point to realize that these present-day codes are quite ancient, that they are the product of still older religious systems, and that throughout their history they have been the bases for the law which has formally expressed society’s interest in controlling human sexual behavior.

It has already been pointed out (Chapter 6) that average frequencies of sexual outlet for the human male are distinctly below those which are normal among some other anthropoids and which would probably be normal in the human animal if there were no restrictions upon his sexual activity. Averages for the single males begin at 3.3 per week and drop with old age, and averages for the married males begin at 4.8 per week and drop with age; but the averages in non-restrained human animals would probably be nearer 7 per week, and in 10 to 15 per cent of the population would probably run higher than that (Chapter 6). It has been stated (Chapter 8) that the differences between these higher figures and the actual rates of the male population provide some measure of the effectiveness of the social pressures, of the specific laws, and of the attitudes, ideals, esthetic values, physical interferences, and other restraints which the social organization imposes upon the sexual activity of the individual.

That these social pressures are primarily religious in their origin is confirmed by the comparisons which can now be made between the frequencies of total sexual outlet and the incidences and frequencies of outlet from the various sexual sources, among persons who are actively concerned with religious organizations, and among persons who are less closely concerned with the teachings and practices of any church group.

In attempting to measure these present-day influences of the church on the sexual behavior of the American population, three religious groups, Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish, are recognized in the present chapter. These faiths embrace most of those Americans who recognize any church affiliation. Within each group a still more important classification has, however, been made. This involves the degree of adherence of the individual to the doctrines and to the activities of the religious group in which he is at least nominally placed. Of course, every degree of adherence exists among various individuals, and as the data have been recorded in our original histories, several such degrees have been recognized (Chapter 3). However, the limited size of the present sample has made it necessary to base the analyses in the present chapter on two groups of Protestants, two groups of Catholics, and two groups of those of the Jewish faith. These groups have included, on the one hand, the less active (or less devout) members of each faith, and on the other hand the more active (or more devout) members of those same faiths. Active or devout in this classification has been taken to mean regular attendance and/or active participation in organized church activities, and/or frequent attendance at the Catholic confessional or the Jewish synagogue. Inactive or non-devout in the immediate analysis has been applied to all persons who have not qualified as active or devout under the above definitions.

It is hardly necessary to add that all comparisons made in the present chapter are based on a preliminary breakdown of each population for sex, race, marital status, age, and educational levels. With the additional breakdowns on the religious group and on the degree of adherence of each subject to that religious group, all of the calculations given in the present chapter are based on 7-way breakdowns. Any analysis short of this would have proven inadequate; but it is only a limited list of religious groups for which we have samples that are adequate for such elaborate treatment (Chapter 3). All conclusions which are drawn in the present chapter should be limited to these particular groups. In the interest of scientific fact and of such social and moral applications as others may wish to draw from the scientific fact, it is to be hoped that religious groups which are not yet sufficiently represented may be included in the future development of this survey.

Considering the frequencies of total sexual outlet (Table 125), the sexually least active individuals in any age and educational group are the Orthodox Jews (who are the least active of all), the devout Catholics, and the active Protestants (in that order). Conversely, the sexually most active individuals are the non-church-going Catholics, with the inactive Protestants and the inactive Jewish males intermediate in the system. At various educational levels and in different age groups there is some variation in this ordering, but there is only one group, namely the single males of the college level, where the data are abundant enough to compare all six religious classifications.

Between adolescence and 15 years of age, the boys who will ultimately go to college are arranged in the following religious groups, beginning with those who are sexually least active and building the list in the direction of those who are most active:

| Jewish Orthodox |

| Catholic devout |

| Protestant active |

| Jewish inactive |

| Catholic inactive |

| Protestant inactive |

This order remains constant whether the calculations are made as means or as medians, and whether for total populations or for active populations. The order is somewhat different when it is based on the number of persons involved in sexual activity (the active incidence figures). In this latter case, the smallest number of sexually active individuals (91%) is to be found among the Orthodox Jews, while the largest number of active individuals (98%) is to be found among the devout Catholics.

Between 16 and 20 years of age the boys who will go to college, or who are already in college, are arranged in the following order, beginning with the sexually least active group and building the list in the direction of the most active group:

| Jewish Orthodox | Catholic inactive |

| Catholic devout | Protestant inactive |

| Protestant active | Jewish inactive |

This order varies somewhat with the calculations as means or as medians, and for total populations and for active populations.

Between 21 and 25 years of age, the single males who have gone to college are arranged in the following order, beginning with the sexually least active group and ending with the most active group:

| Catholic devout | Catholic inactive |

| Protestant active | Jewish inactive |

| Protestant inactive |

This order is more or less constant, whatever the method of calculating.

For the less adequate series of religious groups among males of other educational levels the story appears to be much the same. In both grade school and high school groups, the persons most actively connected with church activities are, again, the least active sexually, and the males who are sexually most active are those Catholics who have least to do with their church.

The differences between the frequencies of these several religious groups are, in most instances, not large but rather constant. There is a 25 per cent difference between groups at certain ages in certain educational levels, and in some instances the most extreme groups have rates of total outlet which are 75 per cent higher than the rates of the least active groups of the same age and educational levels. To put it another way, devout acceptance of the church’s teaching is correlated with sexual frequencies which are two-thirds or less than two-thirds of the frequencies which are found among males of corresponding age and educational levels who are not actively connected with the church. Either this is the direct effect of church teachings, or else those individuals who become most actively associated with the church are a select group which would not have had high frequencies of sexual outlet if they had never belonged to a church. It will take more elaborate analyses of a much larger series of histories to determine which explanation is correct, but there is some evidence now at hand (Chapter 6) that some portion of the devoutly religious individuals have repressed rather than sublimated sex histories.

At various places in the foregoing chapters it has been pointed out that masturbation and intercourse are the chief sources of pre-marital outlet. It is, therefore, to be expected that there should be certain correlations between the frequencies of masturbation and the frequencies of inter course, and thus indirectly of total sexual outlet. In upper and lower social levels (Chapter 10) the frequencies of masturbation do bear an inverse relation to the frequencies of pre-marital intercourse, and it might be anticipated that the suppression of one of these activities by the rules of any religious group would provide some direct impetus to the development of the other activity.

This, however, proves not to be so. The least frequent experience in masturbation is found among the more devout members of each and every one of the religious groups (Table 126), and these are the very groups which have the lowest rates of total outlet. The incidence figures for masturbation are not constantly different, but the mean frequencies are always lower for the more devout groups. This is true for both single and married males of every age group on which there are sufficient data and, strikingly enough, it is true of every educational level in each religious group. In some age and educational groups the masturbatory rates of the active Protestants, the devout Catholics, and the Orthodox Jews do not average more than two-thirds or three-fourths as high as the rates of the inactive members of those same churches. Even in those segments of the population where the differences between devout and inactive groups are more minor, it is significant that they always stand in the same order: the religiously active persons masturbate less frequently than the persons who arc less concerned with their religion. At the other end of the picture, the males who most often masturbate arc the religiously inactive Protestants, sometimes the nonchurch-going members of the Catholic faith, and in some cases the inactive Jewish males.

The objections to masturbation have originated from religious creeds which go back to the most remote beginnings of our Western European- American civilization. Elsewhere in the world masturbation may be looked upon as a childish performance, or as evidence of the incapacity of an individual to make socio-sexual adjustments (Chapter 14); but few other peoples have condemned masturbation as severely as the Jews have. The Talmudic references and discussions make masturbation a greater sin than non-marital intercourse. There were excuses for pre-marital intercourse and for extra-marital intercourse with certain persons under the Jewish code, but no extenuation for masturbation (Bible, Talmud passim). The logic of this proscription depended, of course, upon the reproductive motive in the sexual philosophy of the Jews. This made any act which offered no possibility of a resulting conception unnatural, a perversion, and a sin. Whatever other sources may have contributed to the Christian church’s objections to masturbation, certainly the Jewish traditions must have provided a considerable impetus to the perpetuation of this taboo in the Christian religion. In the Orthodox church today, the Jewish boy is definitely affected by the old-time Hebraic laws on this point, and the often lower rates of the religiously inactive Jewish boys indicate that even they are not entirely free of the ancestral codes.

The Catholic boy is told that masturbation is a carnal sin, particularly because it is so often accompanied by erotic fantasies which represent an improper use of functions which should be reserved for contacts which might lead to reproduction (Davis 1946). Some priests go to considerable lengths to impress a confessant with the idea that masturbation is one of the more serious sins, and earlier church writers sometimes specifically declared it more sinful than fornication (Northcote 1916).

Through most of its past history the Protestant church has been as severe in its condemnation of “self-abuse” as either the Jewish or the Catholic groups, and some Protestant clergymen maintain such attitudes today. However, many Protestant clergymen now accept medical, psychologic, and biologic opinion that masturbation does no physical harm. Perhaps as a result of this, we find the religiously active Protestants of the better educated groups more often involved in masturbation than the devout Catholics or Orthodox Jews. Some Protestant groups now lay less emphasis upon the physical harm supposed to result from masturbation, and attach more importance to the undesirability of allowing oneself to become subject to such a habit. Whatever the issues, however, the record is clear that religious influences do succeed in reducing both the incidence and the frequency of masturbation among the more devout members of each church group.

Nocturnal emissions represent the one type of sexual outlet to which there is a minimum of religious objection. One might, therefore, have anticipated that there would be higher frequencies of nocturnal emissions among males who are more closely allied to the church; but this is not consistently so. What differences there are between the frequencies and the incidences of emissions among religiously more active and religiously less active groups, are quite minor (Table 127). The means differ from the medians calculated for the same groups, nearly as often as the averages for devout groups differ from the averages for inactive groups.

This result is significant. Persons who are interested in moral interpretations in sex education insist that the frequencies of nocturnal emissions rise to sufficient heights to provide all of the necessary sexual outlet for a boy who abstains from other sexual activities. But although the record indicates that those who have been most interested in the church have actually reduced their total outlets, the frequencies of nocturnal emissions in these groups have not been raised (Chapter 15). The relative importance of the emissions is raised by the reduction of the rates of total outlet, but the absolute frequencies of the emissions are not altered.

There are some slight differences in the incidences and frequencies of pre-marital petting in the several religious groups (Table 128) but, as we have already seen, there are much greater differences between the several social levels (Tables 84, 110, Figure 100). The deliberate elaboration of pre-marital petting first emerged as an activity of a particular educational level (the college group), and religious backgrounds seem to have had little to do with the individual’s acceptance or rejection of such activity. Many individuals in lower level groups, whatever their religious connections, consider that petting is a perversion because it is a substitute for actual coitus. At the college level, however, petting is much more often accepted, with little distinction on account of the religious background of the group. There may be some tendency for the more devout Catholics of the college level to avoid petting during the younger adolescent years, but there is no consistent trend in the arrangement of religious groups at any older age level.

In all religious groups, older persons have been disturbed over this petting behavior. In Catholic philosophy, the general principles concerning venial and carnal sins certainly apply to many of the techniques that are utilized in petting (Davis 1946). It is surprising, therefore, that there has not been more specific religious objection to petting, and that young people of all faiths have so uniformly ignored what objections they have heard. That petting is not still more abundant must, however, depend upon the more general inhibitions on sex which religious teachings have built into the very body of our culture.

As already pointed out (Chapter 10), there are material differences between the attitudes on pre-marital intercourse in lower social levels and the attitudes in better educated segments of the population. There may be 7 times (700 per cent) as much pre-marital intercourse among lower social levels as there is in the group that goes to college (Tables 85–87, Figures 101–103). But within any particular social level, the differences between Protestants, Catholics, and Jews, and the differences between the most active and least devout members of each of these religious groups, are very much less (Table 129). Rarely do they amount to more than 50 or 100 per cent. Lower level, religiously active Protestants average only two-thirds as much pre-marital intercourse as religiously inactive Protestants of the same level; but the same lower level Protestants average 6 or 8 times as much pre-marital intercourse as the religiously inactive Protestants of the college level. It is true that within each and every educational level it is the religiously devout group which has the least pre-marital intercourse; and the differences in incidence and frequency figures are enough to appear significant if they were not dwarfed by the differences which are effected by the mores of the social groups which are involved.

Heterosexual coitus is, in many ways, the most important aspect of human sexual behavior. Its occurrence in non-marital histories has been condemned by every religious group, practically without exception, in our Western European-American culture. But this is one more type of sexual activity where religious restraints have had less direct effect than the mores of the several groups which constitute our society.

On the other hand, the origins of these sexual mores must be credited to the long-time effects which religious teachings have had through the many hundreds of years in which our cultural patterns have been developing. Religiously active members of the upper social level know that they are rejecting pre-marital intercourse on purely moral grounds (Chapter 10). Religiously inactive persons at this same level reject pre-marital intercourse almost as often, but they insist that they do so as a matter of plain decency. There is, however, little difference in meaning between these two verbalizations of what are basically the same religious philosophies.

Among males of the lower social levels, those who are least active in the church rather freely accept pre-marital intercourse without conflicts of conscience. The religiously more devout individuals at the same level may accept coitus almost as often, although they “know that it is a sin,” and they may occasionally be disturbed by their recognition of its moral significance. Nevertheless, both church-going and non-church-going males of the lower social levels continue to have pre-marital coitus with frequencies that average far above those of any upper level group, because all lower level groups, whatever the degree of their religious affiliation, believe that it is human nature to have intercourse, and an inevitable activity for man as he is made.

The church may even have more influence on the masturbatory behavior of a male than it does upon his pre-marital coital behavior. The acceptance or rejection of masturbation is not so difficult an issue to so many persons; but the very fact that coitus is a more significant activity socially makes its acceptance or rejection a matter of greater importance in the mores of a group. It would appear that in order to go further in changing overt behavior in regard to pre-marital intercourse, the church will have to affect the thinking of whole social levels; and that is a long-time process.

The available data are inadequate for analyzing the frequencies of marital intercourse in more than a few of the religious groups which have contributed to this study. It is interesting to note, however, that in these particular groups marital intercourse is consistently affected by the degree of church affiliation. In practically every instance the religiously active groups engage in marital intercourse less frequently than the religiously inactive groups (Table 130). There are frequencies in the inactive groups which are between 20 and 30 per cent higher than the frequencies in the religiously active groups of the same age and educational level. What effect this may have upon the quality of marital adjustments among religiously active persons is a matter that will merit further investigation.

There is much more homosexual activity among males of lower educational levels than there is among males of the college level (Table 90, Figure 105). Within any particular educational level the differences between religious groups are not so great (Table 131). Between grade school and college males of the same religious group there may be a 200 to 500 per cent difference. Between religiously active and religiously inactive groups of the same denomination in the same educational level, the differences are ordinarily not more than 50 to 150 per cent, and sometimes they are not even 10 per cent. Such differences as do occur lie in the direction of less homosexual activity among devout groups, whether they be Protestant, Catholic, or Jewish, and more homosexual activity among religiously less active groups.

The Hebrews, in contrast to some of their neighbors, attached a severe religious condemnation to homosexual activity (May 1931, Westermarck 1936, Genesis 19, Leviticus 18: 7, 22, Leviticus 20: 13, Judges 19,1 Kings 22:46, II Kings 23:7, Romans 1:27,1 Corinthians 6:9, I Timothy 1:9-10, Talmud passim). There has, in consequence, been a continuous history of condemnation of the homosexual in the Christian church from its very beginning. Nevertheless, there has not been so frequent or so free discussion of the sinfulness of the homosexual in religious literature as there has been of the sinfulness of masturbation and of pre-marital intercourse. Consequently, it is not unusual to find even devoutly religious persons who become involved in the homosexual without any clear understanding of the church’s attitude on the subject.

In general, however, the highest incidences of the homosexual are among the non-devout groups, and the lowest incidences are to be found among the more devout groups. In upper educational levels, among religiously inactive groups, something between 10 and 50 per cent more individuals may be involved than in the active groups; and in lower educational levels the differences in incidences are even greater. The differences in frequencies between the devout and non-devout groups are ordinarily much less, except that the homosexual among Orthodox Jewish groups appears to be phenomenally low.

There are only minor differences in the emphases which the several religious groups have placed upon sexual morality. The strictly Orthodox Jewish code and the strict Catholic interpretations differ somewhat, but both of them accept the reproductive philosophy of sex, and both of them consider sexual activities which do not offer the possibility of fruition in reproduction as morally wrong. Consequently both of them vigorously condemn masturbation, and both of them attach a tremendous importance to the value of virginity at the time of marriage. The Jewish church maintains its stand on the basis of Biblical and Talmudic interpretations. The Catholic church more often bases its interpretations on a natural philosophy which may be re-interpreted from time to time but which has always emphasized the abnormality or the perverseness of sexual behavior which occurs outside of marriage.

These restraints on sexual activities are well recognized among devout Catholics, and often have major effects on the personalities of these individuals. Devout Catholics are restrained in regard to the frequencies of their total outlet, and in regard to their acceptance of any variety of sexual outlets. Non-devout Catholics are much more active sexually. As the church might well contend, the Catholics who are most active sexually are those who are not good Catholics. There will be persons who will suggest that the higher rates of sexual activity among non-devout Catholics depend upon the fact that many poorly educated and immigrant groups belong to that church; but it should be pointed out again that all comparisons between religious groups have been made for populations that are homogeneous in regard to five other biologic and social items, and that Catholic groups of particular educational levels have been compared only with other groups of exactly the same levels. We have no sufficient data for explaining these high rates of sexual activity among the non-devout Catholic groups.

The intermediate positions of the Protestant groups are again in line with our understanding of the intermediate effectiveness of the control which the Protestant church attempts to exercise on sexual behavior. There are, of course, considerable differences between Protestant sects on this matter and often greater differences in the interpretations of sexual moralities among clergymen of the same sect. In general, the more literal groups of the Protestant church make sexual appraisals which are close to those of the Talmud and of the Catholic natural law; but a more liberal portion of the Protestant clergy is inclined to re-interpret all types of sexual behavior in terms of the total social adjustment of the individual.

Even though the differences between the sexual philosophies of these three religious groups are not great, one might have expected greater differences than those which actually exist between the histories of the adherents of the three groups. With one exception, there are surprisingly few differences between the behavior of equally devout or non-devout members of the three religious faiths. The one exception lies among the Orthodox Jewish males. Of all religious groups they are the sexually least active, both in regard to the frequencies of their total sexual outlet, and in regard to the incidences and frequencies of masturbation, nocturnal emissions, and the homosexual. They are closer to the males of other groups in regard to pre-marital petting and pre-marital intercourse.

This relative inactivity of the Orthodox Jewish males is especially interesting, in view of the diametrically opposite opinion which recently stirred a considerable portion of Europe against the Jews as a race. It is further significant to note here that while the non-Orthodox are much more active than the Orthodox Jewish males, the sexually most active groups are religiously non-active Protestants or Catholics as often as they are Jewish.

These data on the lower frequencies of sexual activity among the Orthodox Jews will occasion no surprise to those who understand the pervading asceticism of Hebrew philosophy. Non-devout Jewish groups, even including those who observe none of the Orthodox customs and who may be removed by several generations from ancestors who ever attended the synagogue, may still be controlled to a considerable degree by the Talmudic interpretations of sexual morality. There is a general opinion that Jewish groups discuss sexual matters publicly with less restraint than most other groups, and this opinion may provide some basis for the general impression that Jews are sexually more active. It has been notable, however, in a high proportion of our Jewish histories, that the freedom with which they record the details of their own sexual activities and the freedom with which they discuss those details, not only with us but with many of their fellows and with utter strangers, has surprisingly little relation to the extent of the overt activity in their individual sexual histories. The influence of the several thousand years of Jewish sexual philosophy is not to be ignored in the search for any final explanation of these data.

The differences between religiously devout persons and religiously inactive persons of the same faith are much greater than the differences between two equally devout groups of different faiths. In regard to total sexual outlet the religiously inactive groups may have frequencies that are 25 to 75 per cent higher than the frequencies of the religiously devout groups. Among religiously inactive males there are definitely higher frequencies of masturbation, pre-marital intercourse, marital intercourse, and the homosexual.

The church, however, exerts a wider influence on even non-devout individuals, by way of the influence which it has had throughout the centuries upon the development of the sexual mores of our Western European-American culture. The religious codes have always and everywhere been the prime source of those social attitudes which, in their aggregate, represent the sexual mores of all groups, devout or non-devout, church-going or non-church-going, rational, faithful to a creed, or merely following the custom of the land. It is, of course, often contended that social attitudes are the product of experience and that the wisdom thus acquired becomes the basis of the formalized systems of ethics which are recognized by various religious bodies. In theological terms, such systems are ascribed to divine revelation. Whether the religious, social, and legal systems came before the social experience, or the social experience before the formulations of the rules of behavior, is, however, a matter that needs careful historical investigation before any final conclusions are reached.

In an older day, when church courts had authority over the life and death of each and every individual, departures from the expressed sexual codes made the culprit painfully aware of the source of the sexual mores. In the present day, when most of the population refuses to recognize the jurisdiction of religious courts, the influence of the church is more indirect; but the ancient religious codes are still the prime sources of the attitudes, the ideas, the ideals, and the rationalizations by which most individuals pattern their sexual lives.

No social level accepts the whole of the original Judaeo-Christian code, but each level derives its taboos from some part of the same basic religious philosophy. Whether sexual acts are evaluated in terms of what is right or wrong (as the upper social level puts it), or of what is natural or unnatural (as the lower social level considers it), the Hebraic and Christian concept of the reproductive function of sex lies back of both interpretations. The lower social level’s taboo on nudity (Chapter 10) has a long history in Jewish codes and in Catholic church rulings, and the upper level’s freer acceptance of nudity is in direct violation of church opinion. On the other hand, the upper level accepts the church’s restrictions on pre-marital and extra-marital intercourse (Chapter 10), while the lower level largely ignores the religious objections on those items. Particular individuals may come nearer to accepting the whole of the sexual code of the particular religious group to which they belong, but the patterns of every social level depart at some point from every church code.

These apparent conflicts between the religious codes and the patterns of sexual behavior may lead one to overlook the religious origins of the social patterns. Nevertheless, the individual who denies that he is in any way influenced by church rulings still stoutly defends the church’s system of natural law, recognizes certain behavior as normal and other activities as unnatural, abnormal, and perverse, or considers that certain things (but only certain things) are fine, esthetically satisfactory, socially expedient, and decent for a mature and intelligent male to engage in. In so contending, he perpetuates the tradition of the Judaic law and the Christian precept.

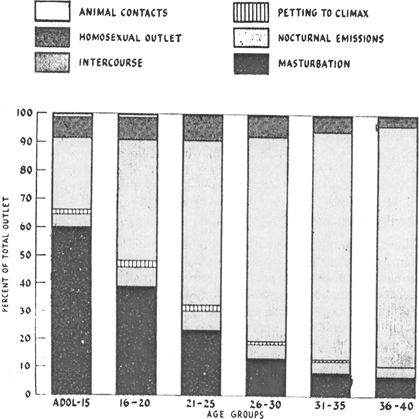

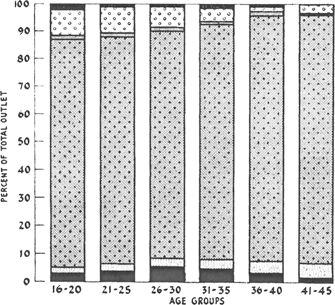

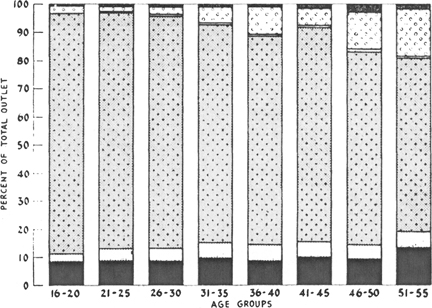

Figure 126. Sources of orgasm for total U. S. population, by age groups

Summary data, corrected for distribution of age, marital status, and educational level shown in U. S. Census of 1940. Figures 126–133 on same scale, so percents of total outlet derived from each source may be seen by direct comparisons of all these figures.

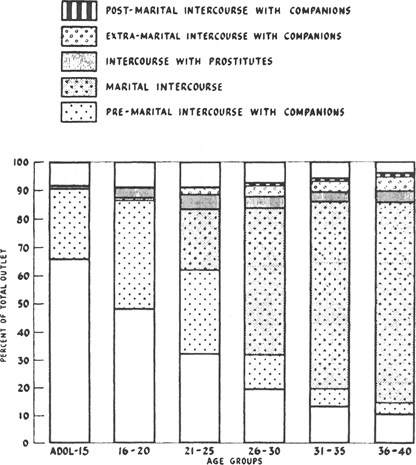

Figure 127. Types of heterosexual coitus contributing to outlet of total U. S. population in each age period

Summary data, corrected for distribution of age, marital status, and educational level shown in U. S. Census for 1940. Identical with Figure 126, except that the area of the total heterosexual intercourse is subdivided into its several sources. Figures 126 and 127 on same scale, so direct comparisons can be made between figures.

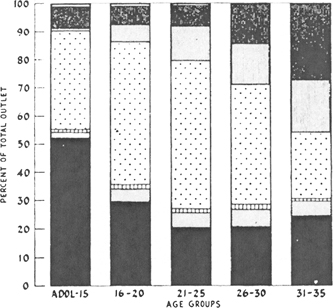

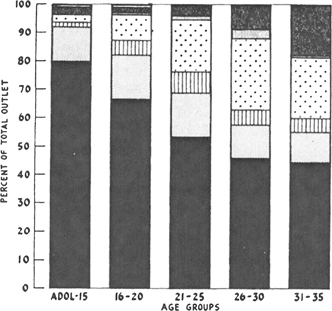

Figure 128. Sources of orgasm for single males of the grade school level, by age groups

Figures 126–133 on same scale, so percents of total outlet derived from each source may be seen by direct comparisons of all these figures.

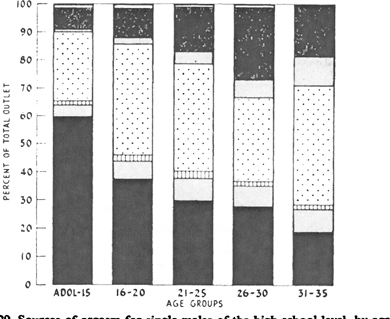

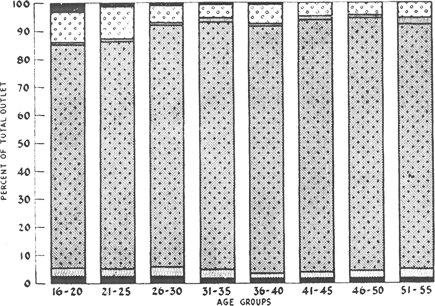

Figure 129. Sources of orgasm for single males of the high school level, by age groups

Figures 126–133 on same scale, so percents of total outlet derived from each source may be seen by direct comparisons of all these figures.

Figure 130. Sources of orgasm for single males of the college level, by age groups

Figures 126–133 on same scale, so percents of total outlet derived from each source may be seen by direct comparisons of all these figures.

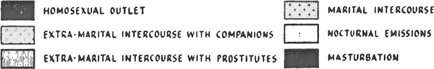

Key to Figures 128-130

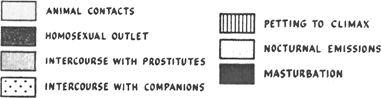

Figure 131. Sources of orgasm for married males of the grade school level, by age groups

Figures 126–133 on same scale, so percents of total outlet derived from each source may be seen by direct comparisons of all these figures.

Figure 132. Sources of orgasm for married males of the high school level, by age groups

Figures 126–133 on same scale, so percems of total outlet derived from each source may be seen by direct comparisons of all these figures.

Figure 133. Sources of orgasm for married males of the college level, by age groups

Figures 126–133 on same scale, so percents of total outlet derived from each source may be seen by direct comparisons of all these figures.

Key to Figures 131-133