Among the social factors affecting sexual activity, marital status is the one that would seem most likely to influence both the frequencies and the sources of the individual’s outlet. The data, however, need detailed analyses.

In social and religious philosophies, there have been two antagonistic interpretations of sex. There have been cultures and religions which have inclined to the hedonistic doctrine that sexual activity is justifiable for its immediate and pleasurable return; and there have been cultures and religions which accept sex primarily as the necessary means of procreation, to be enjoyed only in marriage, and then only if reproduction is the goal of the act. The Hebrews were among the Asiatics who held this ascetic approach to sex; and Christian sexual philosophy and English-American sex law is largely built around these Hebraic interpretations, around Greek ascetic philosophies, and around the asceticism of some of the Roman cults (Angus 1925, May 1931).

A third possible interpretation of sex as a normal biologic function, acceptable in whatever form it is manifested, has hardly figured in either general or scientific discussions. By English and American standards, such an attitude is considered primitive, materialistic or animalistic, and beneath the dignity of a civilized and educated people. Freud has contributed more than the biologists toward an adoption of this biologic viewpoint.

Since English-American moral codes and sex laws are the direct outcome of the reproductive interpretation of sex, they accept no form of socio-sexual activity outside of the marital state; and even marital intercourse is more or less limited to particular times and places and to the techniques which are most likely to result in conception. By this system, no socio-sexual outlet is provided for the single male or for the widowed or divorced male, since they cannot legally procreate; and homosexual and solitary sources of outlet, since they are completely without reproductive possibilities, are penalized or frowned upon by public opinion and by the processes of the law.

Specifically, English-American legal codes restrict the sexual activity of the unmarried male by characterizing all pre-marital, extra-marital, and post-marital intercourse as rape, statutory rape, fornication, adultery, prostitution, association with a prostitute, incest, delinquency, a contribution to delinquency, assault and battery, or public indecency—all of which are offenses with penalties attached. However it is labelled, all intercourse outside of marriage (non-marital intercourse) is illicit and subject to penalty by statute law in most of the states of the Union, or by the precedent of the common law on which most courts, in all states, chiefly depend when sex is involved. In addition to their restrictions on heterosexual intercourse, statute law and the common law penalize all homosexual activity, and all sexual contacts with animals; and they specifically limit the techniques of marital intercourse. Mouth-genital and anal contacts are punishable as crimes whether they occur in heterosexual or homosexual relations and whether in or outside of marriage. Such manual manipulation as occurs in the petting which is common in the younger generation has been interpreted in some courts as an impairment of the morals of a minor, or even as assault and battery. The public exhibition of any kind of sexual activity, including self masturbation, or the viewing of such activity, is punishable as a contribution to delinquency or as public indecency.

There have been occasional court decisions which have attempted to limit the individual’s right to solitary masturbation; and the statutes of at least one state (Indiana Acts 1905, ch. 169, § 473, p. 584) rule that the encouragement of self masturbation is an offense punishable as sodomy. Under a literal interpretation of this law, it is possible that a teacher, biologist, psychologist, physician or other person who published the scientifically determinable fact that masturbation does no physical harm might be prosecuted for encouraging some person to “commit masturbation.” There have been penal commitments of adults who have given sex instruction to minors, and there are evidently some courts who are inclined to interpret all sex instruction as a contribution to the delinquency of minors. In state controlled penal and mental institutions, and in homes for dependent children, the administrations are authorized to establish rules of sexual behavior which go beyond the definitions of courtroom law It is the usual practice in such institutions to impose penalties, including physical punishment, for masturbation, and we have histories from at least two institutions which imposed equally severe penalties for nocturnal emissions. The United States Naval Academy at Annapolis considers evidence of masturbation sufficient grounds for refusing admission to a candidate (U. S. Naval Acad. Regul, June 1940). It is probable that the courts would defend the right of the administrators of institutions to impose such ultimate restrictions upon the sexual outlets of their charges.

Concepts of sexual perversion depend in part on this same reproductive interpretation of sex. Sodomy laws are usually indefinite in their descriptions of acts that are punishable; perversions are defined as unnatural acts, acts contrary to nature, bestial, abominable, and detestable. Such laws are interpretable only in accordance with the ancient tradition of the English common law which, as has already been indicated, is committed to the doctrine that no sexual activity is justifiable unless its objective is procreation.

Official church attitudes toward contraception and abortion similarly stem from the demand that there be no interference with reproduction. They are consistent in denying the use of contraceptives in marriage and in intercourse which is outside of marriage, for intercourse outside of marriage is illegal and not a legitimate source of procreation. Medical and presumably scientific data which are adduced in support of the objections to contraception and abortion, are rationalizations or confusions of the real issue, which is the reproductive value of any kind of sexual behavior.

In addition to establishing restrictions by way of the statutory and common law, society at large, and each element in it, have developed mores that even more profoundly affect the frequency of sexual activity and the general pattern of behavior. Some of the community attitudes fortify certain of the legal interpretations, even though no segment of society accepts the whole of the legal code, as its behavior and expressed attitudes demonstrate (Chapter 10). Often the social proscriptions involve more than is in the law, and the individual who conforms with the traditions of the social level to which he belongs, is restricted in such detail as the written codes never venture to cover. Group attitudes become his “conscience,” and he accepts group interpretations, thinking them the product of his own wisdom. Each type of sex act acquires values, becomes right or wrong, socially useful or undesirable. Esthetic values are attached: limitations are set on the times and places where sexual relations may be had; the social niceties (and the law) forbid the presence of witnesses to sexual acts; there are standards of physical cleanliness and supposed requirements of hygiene and sanitation which may become more important than the gratification of sexual drives; the forms of courtesy between men and women may receive especial attention when sexual relations are involved; the effect of the relations upon the sexual partner, the effect upon the subsequent sexual, marital, or business relations with the partner, the effect upon the subject’s own self esteem or subsequent mental or physical happiness, or conflict—may all be involved in the decision to have, or not to have, a socio-sexual relation. While the decision seems to rest upon personal desires, ideals, and concepts of esthetics, the individual’s standards are very largely set by the mores of the social level to which he belongs. In the end, their effect is strongly to limit his opportunity for intercourse, or for most other types of sexual activity, especially if he is unmarried, widowed, separated, or divorced.

A lower level male has fewer esthetic demands and social forms to satisfy. By the time he becomes an adolescent, he has learned that it is possible to josh any passing girl, ask for a simple social date, and, inside of a few minutes, suggest intercourse. Such financial resources as will provide a drink, tickets for a movie, or an automobile ride, are at that level sufficient for making the necessary approaches. Such things are impossible for most better educated males. Education develops a demand for more elaborate recreation and more extended social contacts. The average college male plans repeated dates, dinners, expensive entertainments, and long-time acquaintances before he feels warranted in asking for a complete sexual relation. There is, in consequence, a definitely greater limitation on the heterosexual activities of the educated portion of the population, and a higher frequency of solitary outlets in that group. Upper level males rationalize their lack of socio-sexual activities in terms of right and wrong, but it is certain that the social formalities have a great deal to do with their chastity.

In any case, at any social level, the human animal is more hampered in its pursuit of sexual contacts than the primitive anthropoid in the wild; and, at any level, the restrictions would appear to be most severe for males who are not married. One should expect, then, that the sexual histories of unmarried males would contrast sharply with the histories of married adults; and that, at the end of two thousand years of social monitoring, at least some unmarried males might be found who follow the custom and the law and live abstinent, celibate, sublimated, and wholly chaste lives. Scientists will, however, want to examine the specific data showing the effect of marital status on the human male’s total sexual outlet, and on his choice of particular outlets (if he has any) in his single, married, or post-marital states.

The mean frequencies of total sexual outlet for the married males are always, at all age levels, higher than the total outlets for single males; but, as already pointed out (Chapter 6), essentially all single males have regular and usually frequent sexual outlet, whether before marriage, or after being widowed, separated, or divorced. Of the more than five thousand males who have contributed to the present study, only 1 per cent has lived for as much as five years (after the onset of adolescence and outside of old age) without orgasm.

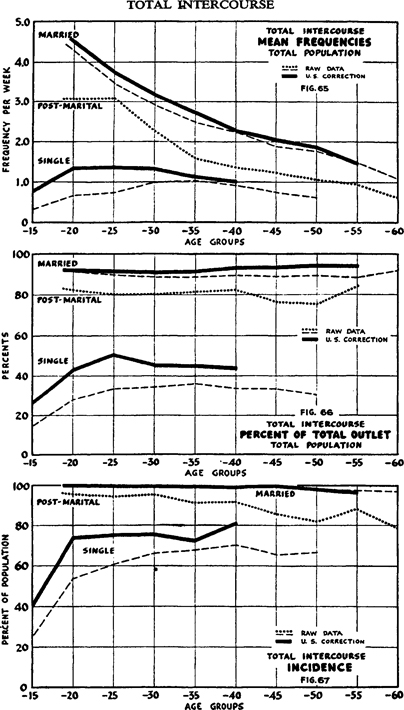

As previously recorded, the mean frequency of the total outlet for the single males between 16 and 20 is (on the basis of the U. S. Corrections) about 3.3 per week (Table 60, Figures 50–52). The mean frequency of total outlet for the married male is about 4.8 per week, which is 47 per cent above the average outlet of the single male At 30, the frequencies for the married males are about 18 per cent above those of the single males, and approximately this relation holds for some period of years. Beyond 40 years of age, the single males may actually exceed the married males in their sexual frequencies. In adolescent years, the restrictions upon the sexual activity of the unmarried male are greatest. He finds it more difficult to locate sources of outlet and he has not learned the techniques for approaching and utilizing those sources when they are available. Nevertheless, his frequency between adolescence and 16 does average about 3.0 per week and between 16 and 20 it amounts to nearly 3.4 per week. This represents arousal that leads to orgasm on an average of about every other day. By the time he is 30, the single male has become much more efficient in his social approaches and does not lag far behind the married individual in his performance. Considering the physical advantage which the married individual has in securing intercourse without going outside of his own home, it is apparent that the older single male develops skills in making social approaches and finding places for sexual contacts which far exceed the skills of married persons. Beau Brummels and Casanovas are not married males. A few of the married males who are involved in promiscuous extra-marital activity are the only ones whose facilities begin to compare with those found among unmarried groups. It is notable that in the male homosexual, where long-time unions are not often maintained and new partners are being continually sought, there are many persons who preserve this same facility for making social contacts for long periods of years.

The differences that exist between the total activities of the younger married male and the younger unmarried male are, to some degree, a measure of the effectiveness of the social pressures that keep the single male’s performance below his native capacity; although the lower rates in the single males may depend, in part, upon the possibility that less responsive males may not marry so young, or may never marry. On the other hand, the fact that the single male, from adolescence to 30 years of age, does have a frequency of nearly 3.0 per week is evidence of the ineffectiveness of social restrictions and of the imperativeness of the biologic demands. For those who like the term, it is clear that there is a sexual drive which cannot be set aside for any large portion of the population, by any sort of social convention. For those who prefer to think in simpler terms of action and reaction, it is a picture of an animal who, however civilized or cultured, continues to respond to the constantly present sexual stimuli, albeit with some social and physical restraints.

In addition to the differences in frequencies of total outlet between married and single males, there are minor differences in incidence and in range of variation in the groups. Between adolescence and 15 years of age, 95 per cent of the unmarried boys have some sort of sexual outlet. From 16 to 35 years of age, 99 per cent or more of these males are engaging in some form of sexual activity (Table 60). Among the married males, a full 100 per cent is sexually active between 16 and 35 years of age. Beyond 35, the incidence figures drop for single males, and at a somewhat faster rate than for married males. The differences are not great.

The range of variation in frequency of outlet in any particular age group is also nearly identical for single and married males. In both populations (Table 49), there are individuals who engage in sexual activity only a few times a year, and there are some who engage in sexual activities regularly 3 or 4 or more times per day (29 or more per week). The lower average rates for single males are not dependent upon the fact that there are no high-rating individuals in that group, but upon the fact that there is a larger number of the single males who have lower rates, and a larger number of married males who have higher rates. At least half of the younger married males have outlets which average 3 or more per week, whereas only a third of the single males fall into that category.

Throughout both single and married histories, there is a steady decline in total sexual outlet in successive age groups (Figures 50–52) is very nearly as great as the differences between married and single males of the same age group. Age is eventually as important as all of the social, moral, and legal factors which differentiate single from married histories.

Every one of the possible sources of sexual outlet is to be found in both single and married histories, except as the activities are limited by definition (as in the case of pre-marital intercourse and extra-marital intercourse). The primary forces determining which particular outlets are utilized are the mores of the social level in which the individual is raised (Chapter 10). Nevertheless, marital status is a prime factor in regard to certain of the outlets.

Masturbation, although it is found in practically all male histories, is very much restricted by the conventions of particular social groups, in all groups, however, it is much more frequent in single histories. It provides about three-quarters (71%) of the sexual outlet for about 85 per cent of the single males below 15 years of age (Table 61, Figures 53–58). The figure is lower for lower educational levels (52.3% for boys who never go beyond eighth grade) and higher (79.6%) for boys who will ultimately go to college (Chapter 10). Between 16 and 20, the incidence begins to go down for all levels, although up until marriage masturbation remains the chief source of sexual outlet for unmarried males who belong to that portion of the population that goes to college. The unmarried males who are actually in college draw nearly two-thirds of their total sexual outlet from masturbation, while pre-marital intercourse accounts for little more than a tenth of the outlet of the group (Table 64). On the other hand, for boys who never get beyond the eighth grade in school, masturbation provides a little more than a quarter (29.2%) of the sexual outlet in their late teens. As soon as marriage occurs, the incidence and frequency of masturbation drop considerably in all social levels. Among college-bred males over two-thirds (69%) of the married men have some self masturbation in their histories. The frequencies in married histories are, however, definitely low, and there are few individuals who have rates that exceed once or twice per week. At lower educational levels only about a third of the married males (29% to 42% in various groups) ever masturbate, and the frequencies are much lower than in upper levels, averaging not a quarter as high as in the corresponding group of single males.

Nocturnal emissions

vary in frequency in different social levels, the figures being higher for upper level males and lower for more poorly educated males. They reach their highest incidence in single males between 21 and 30 years of age. About 85 per cent of the single males have at least some experience with nocturnal dreams that lead to climax (Table 133, Figures 138–139). Hardly more than half of the married males (58.4%) have nocturnal emissions in any particular age group. In younger single males (of the total population), the emissions occur twice as often as among married males of the same age (Table 62, Figures 59–64). In older groups, the incidences and frequencies of nocturnal emissions in married males are about two-thirds of what they are in single males. This, in conjunction with the higher rates of total sexual outlet in the married groups, means that nocturnal dreams provide 5 to 15 per cent of the outlet of the single males, but only 2 to 6 per cent of the outlet of the married males. The lower percentages are in lower educational levels, the higher percentages in upper educational levels (Chapter 10).

Pre-marital petting

as a source of outlet is, by definition, restricted to the single male. The incentives for petting to the point of climax are chiefly those of avoiding pre-marital intercourse (at the social levels where such intercourse is taboo), and initiating sexual relations by way of an activity which is simpler than actual coitus (Chapter 16). There are some married males who engage in such petting to the point of climax with their wives, and there are some upper level males who engage in extra-marital petting with women other than their wives. At lower social levels, pre-marital petting to the point of climax is relatively rare, and there are few records of the occurrence of such behavior in marriage among the poorly educated groups.

Heterosexual intercourse. is the chief pre-marital outlet of the lower social level, although it is a lesser source of outlet for the college-bred portion of the population. Between 16 and 20, it occurs in about 85 per cent of the pre-marital histories of the males who never go beyond eighth grade in school, but it occurs in only 42 per cent of the males who go to college (Table 85, Figure 101). Between 20 and 30, pre-marital intercourse accounts for about two-thirds (57.6% to 68.2%) of the outlet of the males who have not gone beyond eighth grade, although in that same period it accounts for only a fifth (19.4% to 21.4%) of the outlet of the college males.

In marriage, practically 100 per cent of the males of all social levels engage in heterosexual intercourse, except as advancing age limits the activity of some individuals after 45 (Table 56). Among married males of lower educational levels, more than 95 per cent of the total outlet (at 31 to 55 years of age) is derived from intercourse with the spouse or with other females (Table 97, Figures 131–133). Among college-bred males of the same ages, little more than 80 per cent of the total outlet comes from that source. The average for the total married population is about 87 per cent between 31 and 55 years of age. The frequencies of marital coitus are two or three times as high as in the intercourse of the single male (Figures 65–70).

For the total married population, of all social levels, about 85 per cent of the sexual outlet comes from the intercourse with the wife (Table 56, Figures 44–49). It will surprise most people that this figure is not higher. Masturbation, nocturnal emissions, heterosexual intercourse with persons other than the wife, homosexual contacts, and animal intercourse provide the remaining 15 per cent of the activity. The proportion derived from marital intercourse varies from 81.4 per cent between 16 and 20 years, to 88.3 per cent at 45 years of age, after which it again drops. In view of the rather high frequency of extra-marital intercourse among lower social levels, it is interesting to find that the highest percentage of outlet derived from the intercourse with the wife (95.5%) is found among those persons who have not gone beyond the twelfth grade in school, and the lowest percentage (61.9%) among older males who have gone to college (Table 97). Whether or not it is true, as some students contend, that marriage as an institution has resulted from the demand for regular intercourse, it is apparent that marriage does provide a more convenient source of sexual activity than is to be had in any other state.

A part of the heterosexual intercourse of the married males is with females other than their wives. This provides 5 to 10 per cent of the total sexual outlet of the married population taken as a whole (Table 64, Figures 71–76). In the youngest age groups, 37 per cent of the males are having extra-marital intercourse, but this figure cuts down to 30 per cent by 50 years of age.

Among single males, in the population as a whole, prostitutes provide 8.6 per cent of the heterosexual intercourse between 16 and 20 years of age. In successive five-year periods, the percentage rises to 13.3, to 22.0, to 28.9 per cent, and (by age 40) to 38.7 per cent. There is some rise in significance of prostitutes among older males of all social levels, although the group that goes to college never derives as much as 1 per cent of its total outlet from this source, while single males who never go beyond high school ultimately get more than 10 per cent of their outlet from prostitutes. The older single males who have never gone beyond grade school may draw nearly a quarter (23.4%) of their outlet from females whom they pay for intercourse (Figures 77–82).

Among married males (as a whole group), prostitutes never provide more than one or two per cent of the total sexual outlet. This is true of all social levels and all age groups. Married males are much like single males in finding, as they advance in age, an increasing portion of their heterosexual, non-marital outlet with prostitutes. Between 16 and 20, prostitutes provide 10.8 per cent of the extra-marital intercourse and in successive five-year periods the percentages rise to 11.1, to 16.5, to 17.6 percent (at 35 years of age) and to 22.3 per cent by 55 years of age. Among those married males who go to prostitutes at all (the “active population”), an increasing percentage of the total sexual outlet comes from this source; the figure is 3.6 per cent of the total sexual outlet from prostitutes at 20 years of age, with a steady rise in the figures in older groups, until 18.4 per cent of the total outlet of the 55-year old, prostitute-frequenting, married male is derived from the commercial sources.

The single males at all ages have more frequent paid contacts than the males who have wives. The reported frequencies of intercourse with prostitutes for the single males between 16 and 25 (total population) are three or four times as high as among married males of the same age. Between 46 and 50, they are 15 times as high as the frequencies reported by the married males. Marriage is clearly a factor of considerable importance in reducing the frequency of intercourse with prostitutes.

It should, however, be said that we are not entirely confident of the accuracy of these data on extra-marital intercourse, especially among older males from upper social levels. Where social position is dependent upon the maintenance of an appearance of conformity with the sexual conventions, males who have had extra-marital intercourse are less inclined to contribute to the present study. Consequently, it is not unlikely that the actual incidence and frequency figures exceed those given here.

Homosexual contacts

, as might be expected, are most frequent among unmarried males. The lowest incidence, about 27 per cent, occurs between adolescence and 15 years of age (Table 66, Figures 83–88). The figures steadily rise in older groups of single males. Between 36 and 40 years of age, over a third (38.7% is the corrected figure for the total U. S. population) of the unmarried males are having some homosexual experience, and uncorrected figures indicate that about half of the unmarried 50-year olds are so involved.

In marriage, the highest recorded incidence is 10.6 per cent, between 21 and 25 years of age. After that, the incidence in the married groups drops to about 2 per cent at 45 years of age, and still lower in still older married groups. Social factors, particularly the physical and social organization of the family, make it difficult for the married individual to have any sort of sexual relation with anyone except his wife. However, the incidence of the homosexual is probably higher than the available record on the married group shows. Married males who have social position to maintain and who fear that their wives may discover their extra-marital activities, are not readily persuaded into contributing histories to a research study. While it is possible to secure hundred percent samples from younger males, which make the incidence figures for homosexual contacts fairly reliable there, it is rarely possible to get as good a representation of older married males. There are hundreds of younger individuals in the histories who report homosexual contacts with these older, socially established, married males, and the post-marital histories of males who are widowed or divorced include the homosexual in 28.3 per cent of the teen-age group, and still in 10.8 per cent of the 31-35-year old histories. These data make it appear probable that the true incidence of the homosexual in married groups is much higher than we are able to record.

Homosexual relations, both among single and married males, are sometimes a substitute for less readily available heterosexual contacts. This is true at all social levels and at all age groups, especially among isolated, morally restrained, or timid males who are afraid to approach females for sexual relations. On the other hand, it must be recognized that the homosexual is in many instances, among both single and married males, deliberately chosen as the preferred source of outlet; and it is simply accepted as a different kind of sexual outlet by a fair number of persons, whatever their marital status, who embrace both heterosexual and homosexual experiences in the same age period. Consequently, the high incidence of the homosexual among single males is not wholly chargeable to the unavailability of heterosexual contacts. The increased incidence and frequency among older single males are, as previously noted, partly dependent upon the freer acceptance of a socially taboo activity as the individual becomes more experienced and more certain of himself. The very high incidence among the still older males may depend upon the fact that those persons who are not exclusively or primarily homosexual are ordinarily married when younger, and those who have no interest in heterosexual contacts are left in higher proportion in the older, unmarried populations.

Animal contacts

in the northeastern quarter of the United States are largely confined to rural populations and are primarily activities of preadolescent and younger adolescent boys. Social taboos quickly lead the older individual to cover up his activity, to deny it in giving us a history and, in actuality, to stop such contacts at a rather early age. There are differences in incidences and frequencies in different social levels, the activity being highest among those rural boys who ultimately go to college. In this latter group, about 28 per cent has intercourse with animals between adolescence and 15 years of age and 17 per cent engages in the activity sometime between 16 and 20 years of age (Table 59). In this farm population, the incidence drops so rapidly for older single males that we are not warranted in calculating averages on the basis of our present data. Similarly, the active cases are too few to warrant calculations for married males in the northeastern quarter of the United States. Limited data which we have from more western and southwestern portions of the country indicate that such animal intercourse continues as a part of the sexual activity of not a few married adults.

Many of the pre-marital sources of sexual outlet are, to a degree, substitutes for less readily available heterosexual coitus. This is particularly true of masturbation, the homosexual, and intercourse with animals of other species. Sexual activities after marriage are concentrated on heterosexual intercourse and chiefly, but by no means wholly, on marital intercourse. Nevertheless, it would be a mistake to consider that differences in the availability of sources are the sole factors which distinguish the premarital from the marital record. It is to be recalled that the younger male, who is in most cases the unmarried male, is the sexually most active individual; and the intensity and frequency of his response to any situation which comes along, particularly if that situation is novel and unexpected, lead to his involvement in more kinds of sexual activity, whether he be single or married. Similarly, among married males it is the younger ones who have the highest frequencies of masturbation, extra-marital intercourse, homosexual relations, and animal contacts. Marriage is undoubtedly an overwhelming force in focusing sexual activity; but the similar concentration of the activities of the older single male upon his particular forms of outlet, particularly intercourse with prostitutes and the homosexual, indicates that marriage is not the only factor involved. It is also a matter of conditioning which leads to a centering of attention on those activities which have proved most satisfactory. It is a matter of a loss in interest in variety, after an initial experimentation with its charms, of concentrating upon the outlets that are most available in our society as it is set up, and of avoiding those things which are most likely to cause social disturbance.

Throughout the record, the effects of marital status are modified and mitigated by the age of the individual (Chapter 7). In spite of all the social and legal distinctions between the rights and privileges of married as opposed to unmarried individuals, age is, at many points, a more significant factor than marital status in determining the frequencies and, indirectly, the sources of sexual outlet.

The sexual lives of previously married males who are no longer living with wives, have been a closer secret than the lives of single or married adults. We now have the post-marital histories of 433 white males. The sample is too small to warrant analyses even by age; and it is to be noted that there are not enough cases to allow corrections in accordance with the age, marital status, and education distribution shown in the U. S. Census. Uncorrected figures based on our particular sample are, therefore, the only ones available on these post-marital histories. Nevertheless, the data do seem to indicate general trends in regard to each of the sources of outlet.

The post-marital histories are, in general, an interesting combination of items which are characteristic of both single and married groups. The total sexual outlet of the previously married males between the ages of 16 and 30 is about 85 to 95 per cent as high as among married males, which means that it is between 40 and 50 per cent higher than among single males (Table 60, Figures 50–52). At these ages, there is little effect on the frequency of the previously married individual’s sexual activity when he is deprived of a legalized source of outlet. With advancing age, after 30, however, the post-marital frequencies drop more rapidly than those in marriage, to about three-quarters (69% to 76%) of the marital rates; and this actually places them below the rates of even the single groups after age 30. It is not immediately apparent what is responsible for these differences, but the data should be kept in mind.

Many males who dropped masturbation in marriage, return to it after they have become widowed, separated, or divorced. Masturbation is found in a smaller percentage (56% at 16–20 years, 33% at age 45) of the post-marital cases than was true of the single histories; but the post-marital incidence is somewhat higher than it was in marriage (Table 61, Figures 53–58). The frequency of the post-marital masturbation (total population) is about a quarter to one-half of what it was in the single histories, but a little higher than it was in the married histories. For those persons who engage at all in masturbation, the percentage of the total outlet which comes from this source (17% to 36%) in the post-marital period is about twice as high as it was in marriage; but this is only a half to two-thirds as much as it was in the pre-marital period. As in all other populations, advancing age brings some decline in the incidences and frequencies; but the portion of the outlet which is derived from masturbation increases with the years, among these men who live without wives.

Nocturnal emissions (Table 62, Figures 59–64) occur in approximately the same number of persons in pre-marital, marital, and post-marital histories. The incidence is only slightly higher in single histories. The frequencies are highest among single males, two-thirds as high among married males, and somewhere between the two among previously married persons (where the frequencies range from about 0.26 per week at 16-30, to 0.19 at age 55). Nevertheless, while the incidences and actual frequencies go down, the percentage of the total outlet which is derived from nocturnal dreams (among previously married males who have any at all) rises more or less steadily from 10 per cent or 11 per cent between 16 and 25, to 21 per cent at age 50. Only after that does the significance of the dreams in the post-marital picture show any considerable drop.

Heterosexual intercourse is most important in the marital histories, least important in the histories of single males, and midway or higher in importance in the post-marital group (Table 63, Figures 65–70). The number of previously married males involved in intercourse ranges from about 96 per cent in the younger ages to 82 per cent by age 50. The drop in frequency is a bit faster than among married males. With advancing age, prostitutes provide an increasing part of the intercourse, companions a decreasing part of the post-marital intercourse (Tables 64–65, Figures 71–82).

The actual frequencies and the proportion of the total outlet which is derived from intercourse similarly lie between those of the married and single groups. They lie closer to those of the married males when the post-marital group is younger, and are nearly identical with those of married males when the group is older. Males who have ever become accustomed to the coital activities of marriage, keep coitus as their chief source of outlet (80% to 85% of their outlet) even after their marriages are terminated by the spouse’s death, or by separation or divorce. Nearly all males (about 95%), after they have once been initiated into regular coital experience, whether as older single males or as previously married persons, repudiate the doctrine that intercourse should be restricted to marital relations. Nearly all ignore the legal limitation on intercourse outside of marriage. Only age finally reduces the coital activities of those individuals, and thus demonstrates that biological factors are, in the long run, more effective than man-made regulations in determining the patterns of human behavior. The picture probably differs for different social levels, but this breakdown cannot be made with the present-sized sample.

Homosexual activity occurs among many of the males who have been previously married (Table 66, Figures 83–88). It is in 28 per cent of the younger histories, and in a smaller number of the older histories (5.2% at 45 years of age). This group is larger than the group that had homosexual relations during marriage. While the incidence among the younger-single and post-marital histories is about the same, it is eight times higher among the older males who have never been married. It is evident in a few of the individual histories that marriages sometimes break up because of the male partner’s developing preference for relations with other males; in a few cases the male is induced by the breakdown of the heterosexual marriage to accept his first homosexual experience; but in a larger number of cases it is a matter of the individual returning to the sort of outlet that he had before he was ever married. The mean frequencies of the homosexual contacts (in the active population) among these previously married males are a bit lower than, or of the same order as among single males; and they are twice as high as among those married males who are having homosexual relations. The percentage of the previously married male’s total outlet which is derived from the homosexual (19 per cent, rising to 22 per cent at older ages) is similarly double that found among married males, but not nearly so high as is found among older single males (where the figure rises to nearly half of the total sexual outlet). With advancing age, the homosexual in the post-marital group definitely drops in incidence, stays more or less constant in frequency, and slightly increases in its significance as a part of the total sexual outlet.

* * *

In summary, it is to be noted that the average male who is widowed or divorced is not left without sexual outlet, as the mores of our society and legal codes would have him. On the contrary, and in spite of customs and laws, he continues to have almost as active a sexual life as when he was married. He depends to a somewhat greater degree upon masturbation and nocturnal dreams, and at younger ages he turns to homosexual activity about as often as the single, previously unmarried male, but in most cases this widowed or divorced individual depends upon heterosexual intercourse for most (80%) of his not inconsiderable outlet. His is not the picture of the single male, unless it be the oldest group of the single males with which the comparison is made. Once married, a male largely retains the pattern of the married male, even after marriage ceases to furnish the physically convenient and legally recognized means for a frequent and regular sexual outlet. These data are in striking contrast to those available for the widowed or divorced female who, in a great many cases, ceases to have any socio-sexual contacts and who, very often, may go for long periods of years without sexual arousal or further sexual experience of any sort.