During the past few decades, particularly at upper social levels, premarital physical contacts between males and females have been considerably elaborated without any increase in the frequency of actual intercourse (Chapter 11). These contacts may go far beyond the hugging and kissing which occurred in older generations. In their maximum extensions they may involve all of the techniques of the pre-coital play in which sophisticated married partners engage.

In general this behavior is known to the younger generation as petting, although other terms are applied to certain types of contacts. Those which are confined to latitudes not lower than the neck are sometimes known as necking, and petting is distinguished from the heavy petting which involves a deliberate stimulation of the female breast, or of the male or female genitalia. While most of the younger generation of high school and college-bred males and females more or less accepts petting as usual and proper in pre-marital behavior, some of those who have doubts about the morality of their activities ease their consciences by avoiding the term petting for anything except the more extended forms of contact.

In the present volume the term “petting” has been applied to any sort of physical contact which does not involve a union of genitalia but in which there is a deliberate attempt to effect erotic arousal. Accidental touching is not petting, even though it may bring an erotic response. Simple lip kissing may or may not be petting, depending on the intent and earnestness of the procedure. Petting is not always effective in achieving an arousal, but if there has been a deliberate attempt it satisfies the definition. Soul kissing, smooching, necking, mild petting, and heavy petting are basically one thing, even though there may be differences in the limits to which the techniques are carried. The extent of the petting is not necessarily related to the degree of arousal. Relatively simple contacts—which in some cases may not involve more than a touch or a kiss—may be as effective for certain individuals, under certain circumstances, as the most extreme genital manipulations. If the erotic significance is being considered, a classification of petting should be based on the degree of arousal and the success of the activity in effecting orgasm, rather than upon the nature of the mechanics employed. Obviously, the psychic components are, again (Chapter 15), more important than the physical in this sort of sexual activity.

Until quite recently the deliberate elaboration of petting techniques has been confined largely to pre-marital and marital relationships, and all of the data which are given in the present chapter apply to the pre-marital petting activities of single males. Within much more recent years there has been an increasing tendency to accept petting as an extra-marital relationship among persons who would not think of having extra-marital intercourse, and who more or less persuade themselves that they are still faithful to their spouses if they engage in nothing but petting with other partners. At many an upper level social affair, at cocktail parties, at dances, during automobile rides, after dinner parties, and on other occasions, married males may engage in such flirtations and physical contacts with other men’s wives, sometimes quite openly and often without being restrained by the presence of the other spouses. Unfortunately, the extent of this extra-marital petting was not comprehended in the earlier years of the present study, and we have not yet accumulated sufficient material for reporting on this aspect of human sexual behavior.

Specific data on the incidences and frequencies of pre-marital heterosexual petting have already been given in the following tables and charts, and in earlier discussions in this volume, as follows:

In pre-adolescence there is, in actuality, very little behavior which can properly be classified as petting; but with the onset of adolescence the boy increasingly realizes the significance of sexual arousal and, with the example set by his older companions, he is likely to begin more specific manipulation of the girls with whom he has social contact. Petting provides the first ejaculation for only one-third of one per cent of the boys at the turn of adolescence, but by the age of 15 a number (8.4%) find a specific sexual outlet in such activity. There is a steady increase in the amount of petting that is done in the later teens.

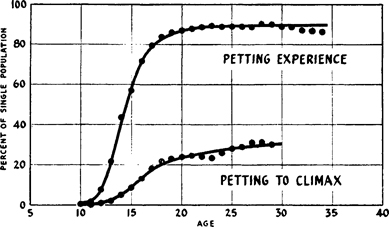

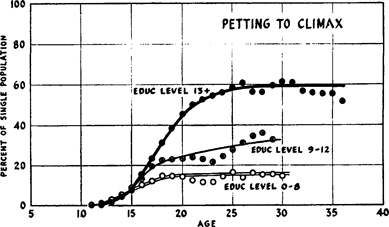

On the exact incidences and frequencies of petting, few data have been available (Hamilton 1929, Willoughby 1937, Bromley and Britten 1938, Wile 1941, Ramsey 1943, Seward 1946). The histories in the present study show that about 88 per cent of the total male population has engaged in some sort of petting, or (in the case of the younger males) will engage in at least some petting prior to marriage (Table 134, Figure 141). The activity is extensive enough to result in orgasm for the males in over a quarter (28%) of this population prior to the time of marriage. However, since petting is more extensive in the present generation than it was in the older generation, the more significant accumulative incidence calculations on males of the college level show over 85 per cent of the younger groups with some petting experience, and something over 50 per cent of the younger males petting to climax prior to marriage (Table 135, Figure 143).

Something between 18 and 32 per cent of the younger population may be involved in petting which leads to climax in each age period prior to marriage (Table 53, Figure 40). The highest active incidence occurs between the ages of 16 and 20. At that time, about a third of the males are securing a portion of their outlet through petting.

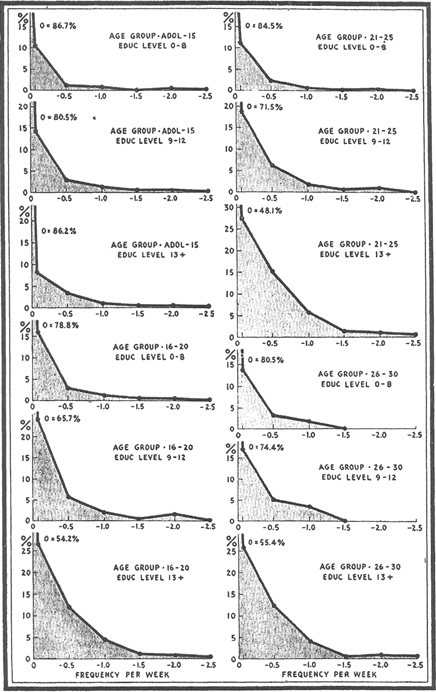

Among those who engage in petting, the frequencies vary considerably (Figure 144). There are males who have petting experiences practically every night in the week and on other occasions in the day. The most active male in the series averaged orgasm about 7 times per week throughout the five-year period between 21 and 25. There are, of course, males who go for weeks and months without dating girls with whom they may engage in petting, and there are some males who may have lapses of a year or two or more between such dates. There are some males who have petting experience with dozens or even hundreds of girls prior to marriage, and there are a few males who have such experience with only two or three girls, and sometimes with no more than the one whom they subsequently marry. These are tremendous differences to be found in any sort of behavior; and since the social significance of petting is much greater than the social significance of masturbation or of some other types of sexual activity, one who attempts to understand human society must allow for wide variations between males on this point.

Figure 141. Pre-marital petting experience (of any kind), and petting to climax: accumulative incidence among single males

Showing percent of the single males that has ever had petting experience by each of the indicated ages. Based on pre-marital histories of population corrected for U. S. Census distribution.

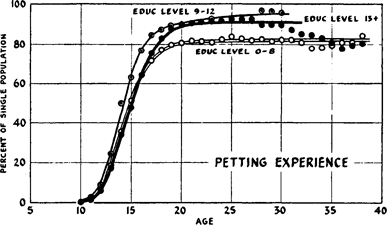

Figure 142. Pre-marital petting experience of any kind: accumulative incidence in three educational levels

Showing percent of each population that has had any kind of petting experience by each of the indicated ages. All data based on unmarried males.

Petting is pre-eminently an activity of youth of the high school and college levels. In both of these groups about 92 per cent of all the males are involved before marriage (Table 135, Figure 142), and the figure is still higher for the younger generations. It is only a slightly smaller number (84%) of the males of the grade school level which has experience of the sort, but this level is restricted in the nature of its activity. Such petting as does occur in the grade school group is often incidental, confined to a few minutes of hugging and kissing prior to actual coitus, and quite without the elaborations which are usual among college students. Petting at upper social levels may be indefinitely prolonged, even into hours of intensive erotic play, and usually never arrives at coitus. Orgasm as a product of petting occurs among 16 per cent of the males of the grade school level, 32 per cent of the males of the high school level, and over 61 per cent of the college-bred males who are not married by the age of 30. The social issues involved in petting are, therefore, matters that chiefly concern the high school and college groups.

Figure 143. Pre-marital petting to climax: accumulative incidence in three educational levels

Showing percent of each population that has ever engaged in pre-marital petting to the point of climax, at each of the indicated ages. All data based on unmarried males.

Thirty years ago, petting involved fewer persons and was a less highly elaborated activity than it often is today. In regard to most other types of sexual activity, the behavior of the older generations (during their youth) was so nearly identical with the behavior of the present-day youth that no significant differences are shown in statistical analyses of the data obtained from the two groups (Chapter 11). The records for petting, however, show actual differences between the generations (Table 102, Figures 117, 118, 121). Even at the college level petting has increased within these thirty years. In the older generation of this group, about 87 per cent of the males were involved; nearly 95 per cent has such experience today. Moreover, the younger generation of college males is starting its petting activity at an earlier age. Among those males who never go beyond grade school, only 78 per cent of the older generation had any petting experience, in contrast to 94 per cent in the present day.

Figure 144. Pre-marital petting to climax: individual variation in frequencies, in four age groups, at three educational levels

Showing percent of each population (vertical line) which engages in pre-marital petting to the point of climax, with each type of frequency (horizontal line). Based on unmarried males.

The frequencies of petting activities reach their height between the ages of 21 and 25 (Table 53, Figures 38, 41). Calculating averages for the total population, including both those who do and those who do not engage in petting, the mean frequency of orgasm from this source, between 21 and 25, is about once in six weeks. For those males who are actually reaching orgasm, the average frequencies are something more than once in three weeks. It is, of course, only a small part of the petting which actually reaches climax, and the frequencies of petting without climax are many times higher than the frequencies of petting to climax. Males who remain unmarried into still older age periods pet to climax less frequently, partly because they carry more of their heterosexual contacts through to coitus, partly because some of them are sexually apathetic, and partly because some of them have homosexual histories.

Petting never accounts for more than 3 per cent of the total outlet for any segment of the total male population (Table 53, Figures 39, 42). This is in the age period between 21 and 25. Considering only those who do reach orgasm in petting (the active population), about 6 per cent of the total outlet is derived from this source during the late teens. While the incidence and frequency figures in the total population drop in later years, the frequencies for those who go as far as orgasm gradually increase. In this active population, among those males who are still unmarried in their thirties, as much as 10 per cent of the outlet is derived from petting.

Petting provides somewhat fewer orgasms than nocturnal emissions, and only animal intercourse is less important as a source of outlet. The real importance of petting, however, lies in the education it provides in making socio-sexual contacts. On this score, pre-marital petting is one of the most significant factors in the sexual lives of high school and college males and females.

Among all urban groups, of all educational levels, petting to climax occurs 2 to 3 times as often as it does among rural boys of the same levels (Table 119). This is one of the most marked distinctions between rural and urban populations. These differences are more marked than the differences between the social levels within each area.

While there has been a fair amount of moral objection to petting, it has already been shown (Chapter 13) that religiously devout males are involved as often as those who are religiously inactive. The differences in patterns of petting in the several social levels outweigh any religious influences within any single social level.

Petting techniques may include all the conceivable forms of physical contact between two individuals of the opposite sex, except that they do not include the actual union of genitalia. Petting usually starts with general body contacts, and with kissing. While kissing under any circumstances is more or less taboo for some individuals of the lower social levels (Chapter 10), it is the most widely distributed form of contact among males and females of the high school and college levels. In these groups it may occur among casual acquaintances who are having their first date. So common is kissing at this level that it has relatively little sexual significance unless it becomes specifically elaborated. Simple lip kissing may be extended into a deep kiss (a French kiss or soul kiss, in the college parlance) which may involve more or less extensive tongue contacts, contacts of the inner lips, and a considerable stimulation of the interior of the mouth by the other individual’s tongue. From the reptiles, down through the birds and the mammals, such tongue and mouth contacts are common concomitants of other sexual activities (Beach 1947). For the other vertebrates, tongue contacts are definitely erotic, and they are naturally so for the human animal that is not too inhibited by its esthetic and cultural backgrounds. Deep kissing may effect orgasm, even though no other physical contacts are involved.

Petting techniques usually expand in a more or less standard sequence, as the partners become better acquainted. Beginning with general body contact, lip kissing, and the deep kiss, it advances to a deliberate manipulation of the female breast, to mouth contacts with the female breast, to manual stimulation of the female genitalia, less often to the manual stimulation of the male genitalia, to the apposition of naked genitalia, to oral stimulation of the male genitalia, and finally to oral stimulation of the female genitalia (Tables 93, 94). Petting techniques at the grade school level rarely go beyond incidental breast and genital contacts; but a goodly portion of the petting at high school and college levels does arrive at more specific genital manipulation. A great many engaged couples go that far before they marry. It is a smaller portion of the population which includes mouth-genital contacts in its pre-marital history (Table 94).

Most of the action in a petting relationship originates with the male. Most of it is designed to stimulate the female. It is doubtful if a sufficient biologic basis could be shown for such a one-sided performance, and it may be that this great difference in the activity of the male and the female is, at least in part, another outcome of the patterns by which females are raised in our culture. The male in the petting relationship derives his stimulation through his own activity in contact with the female, and this is often sufficient, as already indicated, to lead to spontaneous ejaculation.

The astonishment of the lower level at the petting behavior of the better educated groups has been recorded in Chapter 10. As there noted, petting is the particular activity which has led many persons to conclude that college students are sexually wild and perverted. On the other hand, the college level disapproves of the heterosexual intercourse which the lower level has, in some abundance, before marriage. The conflict is obviously one between two systems of mores, between two cultural patterns, only one of which seems right to a person who accepts the traditions of the group in which he has been raised. With the better educated groups, intercourse versus petting is a question of morals. For the lower level, it is a problem of understanding how a mentally normal individual can engage in such highly erotic activity as petting and still refrain from actual intercourse.

There is some indication that younger generations have become freer in making these contacts. They also seem to be becoming freer in petting in public places. On doorsteps and on street corners, and on high school and college campuses, general body contacts and more specific hugging and kissing may be observed in the daytime as well as in the evening hours. Similar contacts may be observed in automobiles, on double dates, at cocktail parties, at parties of other sorts, in taverns and in restaurants, in drug stores and inns, in reception rooms in college dormitories, in high school corridors, in the homes of many of the students, and wherever else young people congregate. More specific contacts may call for more privacy. On occasion, some nudity may be involved, and there are a few records of males who sleep nude with partners with whom they become involved in intensive petting, while never having genital intercourse. Sometimes naked genitalia are placed in apposition, again without effecting coitus.

To some extent, petting is the outcome of the upper level’s attempt to avoid pre-marital intercourse. The condemnation of petting on the ground that it may lead to something that is worse is quite unfounded, for there is no evidence that the frequency of pre-marital intercourse has increased during recent generations (Chapter 11), even though petting has increased. In a number of cases, the specific record indicates that there would have been intercourse if petting had not supplied an outlet.

The physical outcome of petting has been a matter of some concern to educators, to parents, and to high school and college students themselves (as in Elliott and Bone 1929, Butterfield 1939, Rice 1946, Frank 1946). There is probably no sex question which is asked more often by the younger generation than this one concerning the physical outcome of their petting behavior. Consequently, it has been important to secure data on this point. The evidence is now clear that such arousal as petting provides may seriously disturb some individuals, leaving them in a more or less extended nervous state unless the activity has proceeded to the point of orgasm. If orgasm results, there seem to be no after-effects other than those which follow any other type of sexual activity. On the other hand, there is a portion of the males, perhaps as many as a third of those in the present sample, who may become involved in extensive petting which stops short of orgasm, and who are able to calm down without the specific release that sexual climax would provide. Many males who do not reach orgasm while in contact with the female resort to masturbation soon after they leave the girl. Pain which is ordinarily said to occur in the testes or in the groin (but which probably involves some other structures instead) is not uncommonly experienced by the male who fails to reach climax during the petting. It occasionally happens that a male who has gone through a prolonged period of arousal, extending perhaps for an hour or more, finds difficulty in achieving orgasm or, if that point is finally reached, may find that there is an insufficient nervous release, or that there is some localized pain following ejaculation.

Throughout the animal kingdom, and to some extent in the plant kingdom as well, it is normal for an organism to respond to physical contact by pressing against the stimulating object. Unless high temperatures are involved, or pain is adduced by some other quality of the situation, pressure by an object normally leads the animal or some part of its body to move toward that object. The human babe so responds from the time of birth, and it soon learns that such responses are rewarded by the warmth of a contact with another human body, by additional satisfaction which it may receive from the petting and cuddling which its mother or others may give it, sometimes by food, and sometimes by protection from unpleasant situations. These early contacts bring such arousal as would be called erotic in an adult, and which are undoubtedly so in the younger animal (Chapter 5).

Throughout the first years of its life, most parents provide a considerable amount of stimulation for the child, and aid and abet the development of its emotional responses. To love a babe and to teach it to love in return is an accepted part of the mores. But as the child grows still older, most parents in our English-American culture begin to restrain its physical contacts, whether with themselves or with other persons. The small girl is taught that she should not allow contacts if they come from persons who are not relatives and, in particular, that she should avoid contacts with males. The boy learns that he is not supposed to touch girls, at least “until he gets older.” Any show of affection is deliberately controlled, and the growing boy is taught not to expect mothering or much sympathy when he faces difficult situations. As some of the psychiatrists (e.g., English and Pearson 1945) have pointed out, the child is brought into a world that is filled with affection and physical love; but as it grows up it is taught to resist its biologically normal responses and to pull away when it is touched by any other person. After fifteen or twenty years of such training, a marriage ceremony is supposed to correct all of the negative responses which have been drilled into the boy or girl, and in their marital relations they are supposed to become as natural and unrestrained as when they were babes. This, of course, is just too much to expect, and it is not surprising that a considerable portion of the best drilled persons in the population (males and females of the college level) is awkward and ineffective in developing affectional relations after marriage.

The female is, on the average, slower in developing sexually, and less responsive than the male. She is, in consequence, more easily affected by this training in the niceties of restraint. It is, therefore, not surprising to find sexually unresponsive wives in a startlingly high proportion of the marriages, especially in the better educated segments of the population.

Within recent years, younger generations have come to realize something of the significance of pre-marital restraint. Although there is, of course, no doubt that many of the boys and girls who engage in petting do so for the sake of the immediate satisfaction to be obtained, a surprising number of them have consciously considered the relation of such experience to their subsequent marital adjustments. Their understanding of the situation has been helped by the numerous marriage manuals that have been published within the last twenty years, and by courses in psychology, home economics, marriage, and child development, and in other fields of the social sciences. This explains, at least in part, why this younger generation has been more or less oblivious to the not inconsiderable criticisms made by older persons about its petting behavior (Jefferis and Nichols 1912, Forbush 1919, Liederman 1926, Meyer 1927, 1929, 1934, 1935, Eddy 1928a, 1928b, Elliott and Bone 1929, Kirsch 1930, Weatherhead 1932, Edson 1936, Bruckner 1937, Dickerson 1937, Clarke 1938, A Catholic Woman Doctor 1939, Kirkendall 1940, Kelly 1941, Bowman 1942, Moffett 1942, Morgan 1943, Moore 1943, Popenoe 1943, Sadler and Sadler 1944, Fleege 1945, Griffin 1945, 1946, Davis 1946, Rice 1946, Boys Club Amer. 1946, Tanner 1946, A Redemptorist Father 1946, H. Frank 1946, R. Frank 1946, McGill 1946a, 1946b, Gartland 1946).

It is amazing to observe the mixture of scientifically supported logic, and of utter illogic, which shapes the petting behavior of most of these youths. That some of them are in some psychic conflict over their activities is evidenced by the curious rationalizations which they use to satisfy their consciences. They are particularly concerned with the avoidance of genital union. The fact that petting involves erotic contacts which are as effective as genital union, and that it may even involve contacts which have been more taboo than genital union, including some that have been considered perversions, does not disturb the youth so much as actual intercourse would. By petting, they preserve their virginities, even though they may achieve orgasm while doing so. They still value virginity, much as the previous generations valued it. Only the list of most other activities has had new values placed on it.

The younger generation considers that its type of behavior is more natural than the restrained courting of the Victorian generations. It sees logic in the Freudian interpretations of the outcome of such restraint on the total personality of an individual. And it is impressed by the evidence which marriage counselors and psychiatrists have that the long periods of premarital restraint are the source of some of the difficulties which many persons find in making sexual adjustments in marriage.

While our data on the sexual factor in marital adjustment must be presented in a later volume, it may now be stated that there are always many factors which are involved in the success or failure of a marriage. It is usually difficult to understand which factors came first in the chain of events, and the persons immediately concerned in any discord are often the ones least capable of understanding the sources of the difficulties in which they find themselves. Sexual adjustments are not the only problems involved in marriage, and often they are not even the most important factors in marital adjustments. A preliminary examination of the six thousand marital histories in the present study, and of nearly three thousand divorce histories, suggests that there may be nothing more important in a marriage than a determination that it shall persist. With such a determination, individuals force themselves to adjust and to accept situations which would seem sufficient grounds for a break-up, if the continuation of the marriage were not the prime objective.

Nevertheless, sexual maladjustments contribute in perhaps three-quarters of the upper level marriages that end in separation or divorce, and in some smaller percentage of the lower level marriages that break up. Where the sexual adjustments are poor, marriages are maintained with difficulty. It takes a considerable amount of idealism and determination to keep a marriage together when the sexual adjustments are not right. Sexual factors are, in consequence, very important in a marriage.

Specifically, the sexual factors which most often cause difficulty in the upper level marriages are (1) the failure of the male to show skill in sexual approach and technique, and (2) the failure of the female to participate with the abandon which is necessary for the successful consummation of any sexual relation. Both of these difficulties stem from the same source, namely, the restraints which are developed in pre-marital years, and the impossibility of freely releasing those restraints after marriage. On this point Freud, the psychoanalysts, and the psychiatrists in general are largely agreed. On this point, our own data provide abundant evidence. The details of the several thousand marital histories that substantiate this conclusion must be given later, but the matter needs to be brought up at this time because of its bearing on the significance of pre-marital petting.

The male’s difficulties in his sexual relations after marriage include a lack of facility, of ease, or of suavity in establishing rapport in a sexual situation. Marriage manuals are mistaken in considering that the masculine failure lies in an insufficient knowledge of techniques. Details of techniques come spontaneously enough when the male is at ease in his own mind about the propriety of his sexual behavior. But as an educated youth he has acquired ideas concerning esthetic acceptability, about the scientific interpretations of actions as clean or hygienic, about techniques that should be effective, mechanically, when he has intercourse. He has decided that there are sexual activities which are right and sexual activities which are wrong, or at least indecent—perhaps abnormal and perverted. Even though these things may not be consciously considered at the moment of intercourse, they are part of the subconscious which controls his performance. Few males achieve any real freedom in their sexual relations even with their wives. Few males realize how badly inhibited they are on these matters. In extreme cases these inhibitions may result in impotence for the male; and most instances of impotence (prior to old age, and outside of those few cases where there is physical damage to the genitalia) are to be found among upper level, educated males. The psychiatrist well understands that such impotence is the product of inhibitions. The hesitancy of the inhibited male even to try to secure coitus is reflected in the fact that marital coitus in the more religiously inclined males (Chapter 13) and among upper level males in general (Chapter 10) occurs with significantly lower frequencies than marital coitus in the lower educational levels.

The inhibitions of the upper level female are more extreme than those of the average male. There are some of these females who object to all intercourse with their newly married husbands, and a larger number of the wives who remain uninterested in intercourse through the years of their marriage, who object to each new technique which the male tries, who charge their husbands with being lewd, lascivious, lacking in consideration, and guilty of sex perversion in general. There are numerous divorces which turn on the wife’s refusal to accept some item in coital technique which may in actuality be commonplace in human behavior. The female who has lived for twenty or more years without learning that any ethically or socially decent male has ever touched a female breast, and the female who has no comprehension of the fact that sexual contacts may involve a great deal more than genital union, find it difficult to give up their ideas about the right and wrong of these matters and accept sexual relations with any abandon after marriage. The girl who, as a result of pre-marital petting relations, has learned something about the significance of tactile stimulation and response, has less of a problem in resolving her inhibitions after marriage.

There is, then, considerable evidence that pre-marital petting experience contributes definitely to the effectiveness of the sexual relations after marriage. The correlations will be given in a later volume. Some of those who have not had pre-marital petting experience do make satisfactory marital adjustments, but in many cases they make poorer adjustments. Although this conclusion is contrary to the usual statements in the sex education literature (e.g., Dickerson 1930,1937, 1944, Popenoe 1938), it is in line with Terman’s findings (Terman 1938), and there have been some others (e.g., Rice 1933, 1946, Taylor 1933, Himes 1940, Laton and Bailey 1940, Corner and Landis 1941, English and Pearson 1945, Adams 1946) who have arrived at more or less the same conclusion. Whether pre-marital petting is right or wrong is, of course, a moral issue which a scientist has no capacity to decide. What the relations of pre-marital petting may be to a subsequent marital adjustment, is a matter that the scientist can measure.