The present volume is concerned, for the most part, with the record of the frequency and sources of sexual outlet in the biologically mature male, i.e., in the adolescent and older male. This chapter, however, will discuss the nature of sexual response, and will show something of the origins of adult behavior in the activities of the younger, pre-adolescent boy.

The sexual activity of an individual may involve a variety of experiences, a portion of which may culminate in the event which is known as orgasm or sexual climax. There are six chief sources of sexual climax. There is self stimulation (masturbation), nocturnal dreaming to the point of climax, heterosexual petting to climax (without intercourse), true heterosexual intercourse, homosexual intercourse, and contact with animals of other species. There are still other possible sources of orgasm, but they are rare and never constitute a significant fraction of the outlet for any large segment of the population.

Sexual contacts in the adolescent or adult male almost always involve physiologic disturbance which is recognizable as “erotic arousal.” This is also true of much pre-adolescent activity, although some of the sex play of younger children seems to be devoid of erotic content. Pre-adolescent sexual stimulation is much more common among younger boys than it is among younger girls. Many younger females and, for that matter, a certain portion of the older and married female population, may engage in such specifically sexual activities as petting and even intercourse without discernible erotic reaction.

Erotic arousal is a material phenomenon which involves an extended series of physical, physiologic, and psychologic changes. Many of these could be subjected to precise instrumental measurement if objectivity among scientists and public respect for scientific research allowed such laboratory investigation. In the higher mammals, including the human, tactile stimulation is the chief mechanical source of arousal; but the higher mammal, especially the human, soon becomes so conditioned by his experience, or by the vicariously shared experiences of others, that psychologic stimulation becomes the major source of arousal for many an older person, especially if he is educated and his mental capacities are well trained. There is an occasional individual who comes to climax through psychologic stimulation alone.

Erotic stimulation, whatever its source, effects a series of physiologic changes which, as far as we yet know, appear to involve adrenal secretion, typically autonomic reactions, increased pulse rate, increased blood pressure, an increase in peripheral circulation and a consequent rise in the surface temperature of the body; a flow of blood into such distensible organs as the eyes, the lips, the lobes of the ears, the nipples of the breast, the penis of the male, and the clitoris, the genital labia and the vaginal walls of the female; a partial but often considerable loss of perceptive capacity (sight, hearing, touch, taste, smell); an increase in so-called nervous tension, some degree of rigidity of some part or of the whole of the body at the moment of maximum tension; and then a sudden release which produces local spasms or more extensive or all-consuming convulsions. The moment of sudden release is the point commonly recognized among biologists as orgasm.

The person involved in a sexual situation may be more or less conscious of some of the physiologic changes which occur although, unless he is scientifically trained, much of what is happening escapes his comprehension. Self observation may be especially inadequate because of the considerable (and usually unrecognized) loss of sensory capacities during maximum arousal. The subject’s awareness of the situation is summed up in his statement that he is “emotionally aroused”; but the material sources of the emotional disturbances are rarely recognized, either by laymen or by scientists, both of whom are inclined to think in terms of passion, a sexual impulse, a natural drive, or a libido which partakes of the mystic more than it does of solid anatomy and physiologic function.

The most important consequence of sexual orgasm is the abrupt release of the extreme tension which preceded the event and the rather sudden return to a normal or subnormal physiologic state after the event. In the mature male, ejaculation of the liquid secretions of the prostate and seminal vesicles, through the urethra of the penis, is a usual consequence of the convulsions produced by orgasm in those particular organs; and such ejaculation usually provides the most ready proof that the individual has passed through climax. But orgasm may occur without the emission of semen. This latter situation is, of course, the rule when orgasm occurs among pre-adolescent males and among females. It also occurs among a few adult males (11 out of 4,102 adult males in our histories) who either are afflicted with ejaculatory impotence (6 cases: 2 operative, 2 hormonal, 1 after severe illness, 1 in an apparently normal individual), or who deliberately constrict their genital muscles (5 cases) in the contraceptive technique which is known as coitus reservatus, These males experience real orgasm, which they have no difficulty in recognizing, even if it is without ejaculation.

Among pre-adolescent boys, however, and among younger females, orgasm is not so readily recognized, partly because of the lack of an ejaculate, and partly because the inexperienced individual is without a background from which to judge the event. In the younger boy there is no ejaculate because the prostate and seminal vesicles are not yet functionally developed, and in the female those glands are rudimentary and never develop. Nevertheless, erotic arousal and orgasm where it occurs among younger boys and among females appears to involve the same sequence of physiologic events that has been described for the older, ejaculating males; and many of the younger boys and most of the older females who have contributed to the present study have been able to supply apparently reliable records of such experience.

While climax is thus clearly possible without ejaculation, it is doubtful if ejaculation can ordinarily occur without a preceding climax. There are some (the implication is in Reich 1942; also in Wolfe 1942) who consider that this latter situation does occur, and not infrequently, among some males. Subjects are quoted who have had erections and who have ejaculated under conditions which they insist brought them no satisfaction. But in our histories there are many subjects who make similar statements. There are husbands who report unsatisfactory intercourse with unresponsive wives; there are other males who so characterize their intercourse with prostitutes; and there are males who insist that they are “not at all aroused” in the stray homosexual relations which they have. Most of these individuals do, however, erect and ejaculate in such situations; and these reports probably amount to little more than records of varying degrees of physiologic disturbance during arousal and orgasm; or they are merely evidence of minimal psychic components with good enough physical responses, or, sometimes, of good enough psychic reactions that are inhibited, disguised, or rationalized in order to evade moral responsibility for socially taboo behavior. To repeat: the biologist thinks of ejaculation as the product of the convulsions which result from the physiologic event commonly known as orgasm; and, except under laboratory experimental conditions (as in the direct, electrical stimulation of erectile centers in the spinal cord) it is difficult to understand what mechanisms could produce ejaculation without a precedent orgasm. The confusion in the literature seems to be the result of making the term orgasm and orgastic pleasure synonymous. It is, of course, quite possible to recognize many degrees of physiologic change, and many degrees of satisfaction among sexual experiences, and there are admittedly occasions when there is little pleasure accompanying an ejaculation. But we have no statistics on the frequencies of physiologic differences, or of the various degrees of satisfaction, and, in the present study, all cases of ejaculation have been taken as evidence of orgasm, without regard to the different levels at which the orgasms have occurred.

Behavior during orgasm varies considerably with different individuals just as all other aspects of sexual behavior differ in any population (Chapter 6). The descriptions of orgasm in clinical texts, marriage manuals, and other literature are, however, remarkably uniform, partly because of each author’s limited experience, and chiefly because of his failure to search for variation in securing data from clinical subjects. In consequence, there has been little comprehension of the complexity of the problem involved in advising different persons about their sexual adjustments, and about sexual techniques in marriage. There is great variety among adult males; and, it is interesting to note, there is as great variety and the same sort of variety among pre-adolescent boys. One of our subjects, who has had contacts with certain males over long periods of years (as many as sixteen years in some cases), from their early pre-adolescence into their late teens and twenties, states that the particular type of orgasm experienced by a younger boy remains as his particular type into his adult years. The variation in pattern of orgastic response thus seems to depend, at least to some degree (and in the limited number of cases so far studied), on inherent differences in the biologic constitution of different individuals.

Our several thousand histories have included considerable detail on the nature of orgasm; and these data, together with the records supplied by some older subjects who have had sexual contacts with younger boys, provide material for describing the different sorts of reactions which may occur. In the pre-adolescent, orgasm is, of course, without ejaculation of semen. In the descriptions which follow, the data supplied by adult observers for 196 pre-adolescent boys are the sources of the percentage figures indicating the frequency of each type of orgasm among such young males. While six types are listed, it should be understood that all gradations occur between the situations which are herewith described.

1. Reactions primarily genital: Little or no evidence of body tension; orgasm reached suddenly with little or no build-up; penis becomes more rigid and may be involved in mild throbs, or throbs may be limited to urethra alone; semen (in the adult) seeps from urethra without forcible ejaculation; climax passes with minor after-effects. A fifth (22%) of the pre-adolescent cases on which there are sufficient data belong here, and probably an even higher proportion of older males.

2. Some body tension: Usually involving a tension or twitching of one or both legs, of the mouth, of the arms, or of other particular parts of the body. A gradual build-up to a climax which involves rigidity of the whole body and some throbbing of the penis; orgasm with a few spasms but little after-effect. This is the most common type of orgasm, involving nearly half (45%) of the pre-adolescent males, and perhaps a corresponding number of adult males.

3. Extreme tension with violent convulsion: Often involving the sudden heaving and jerking of the whole body. Descriptions supplied by several subjects indicate that the legs often become rigid, with muscles knotted and toes pointed, muscles of abdomen contracted and hard, shoulders and neck stiff and often bent forward, breath held or gasping, eyes staring or tightly closed, hands grasping, mouth distorted, sometimes with tongue protruding; whole body or parts of it spasmodically twitching, sometimes synchronously with throbs or violent jerking of the penis. The individual may have some, but little, control of these involuntary reactions. A gradual, and sometimes prolonged, build-up to orgasm, which involves still more violent convulsions of the whole body; heavy breathing, groaning, sobbing, or more violent cries, sometimes with an abundance of tears (especially among younger children), the orgasm or ejaculation often extended, in some individuals involving several minutes (in one case up to five minutes) of recurrent spasm. After-effects not necessarily more marked than with other types of orgasm, and the individual is often capable of participating in a second or further experience. About one sixth (17%) of the pre-adolescent boys, a smaller percentage of adult males.

4. As in either type 1 or 2; but with hysterical laughing, talking, sadistic or masochistic reactions, rapid motions (whether in masturbation or in intercourse), culminating in more or less frenzied movements which are continued through the orgasm. A small percentage (5%) of either preadolescent or adult males.

5. As in any of the above; but culminating in extreme trembling, collapse, loss of color, and sometimes fainting of subject. Sometimes happens only in the boy’s first experience, occasionally occurs throughout the life of an individual. Regular in only a few (3%) of the pre-adolescent or adult males. Such complete collapse is more common and better known among females.

6. Pained or frightened at approach of orgasm. The genitalia of many adult males become hypersensitive immediately at and after orgasm, and some males suffer excruciating pain and may scream if movement is continued or the penis even touched. The males in the present group become similarly hypersensitive before the arrival of actual orgasm, will fight away from the partner and may make violent attempts to avoid climax, although they derive definite pleasure from the situation. Such individuals quickly return to complete the experience, or to have a second experience if the first was complete. About 8 per cent of the younger boys are involved here, but it is a smaller percentage of older boys and adults which continues these reactions throughout life.

It has been assumed that the development of sexual attitudes and the first overt sexual activities occur in the early history of the infant, but there have been few specific data available. Recently we have begun the accumulation of information through conferences with quite young children and with their parents; and in addition we now have material obtained by some of our subjects through the direct observation of infants and of older preadolescents. These histories emphasize the early development of the attitudes which largely determine the subsequent patterns of adult sexual behavior; but this material must be analyzed in a later volume, after we have accumulated a great many more specific data. For the time being we can report only on the specifically genital play and overt socio-sexual behavior which occurs before adolescence.

We are not in a position to discuss the developing child’s more generalized sensory responses which may be sexual, but which are not so specific as genital activities are. Freud and the psychoanalysts contend that all tactile stimulation and response are basically sexual, and there seems considerable justification for this thesis, in view of the tactile origin of so much of the mammalian stimulation. This, however, involves a considerable extension of both the everyday and scientific meanings of the term sexual, and we are not now concerned with recording every occasion on which a babe brings two parts of its body into juxtaposition, every time it scratches its ear or its genitalia, nor every occasion on which it sucks its thumb. If all such acts are to be interpreted as masturbatory, it is, of course, a simple matter to conclude that masturbation and early sexual activity are universal phenomena; but it is still to be shown that these elemental tactile experiences have anything to do with the development of the sexual behavior of the adult. There is now a fair list of significant and in many cases observational studies of this “pre-genital” level of reaction among infants and young children (Bell 1902, Blanton 1917, Hattendorf 1932, Isaacs 1933, Dudycha 1933, Halverson 1938, 1940, Campbell 1939, Conn 1939, 1940, Levy 1940. See Sears 1943 for a summary).

Adult behavior is more obviously a product of the specifically genital play which is found among children, and on which we can now provide a statistical record. Our own interviews with children younger than five, and observations made by parents and others who have been subjects in this study, indicate that hugging and kissing are usual in the activity of the very young child, and that self manipulation of genitalia, the exhibition of genitalia, the exploration of the genitalia of other children, and some manual and occasionally oral manipulation of the genitalia of other children occur in the two- to five-year olds more frequently than older persons ordinarily remember from their own histories. Much of this earliest sex play appears to be purely exploratory, animated by curiosity, and as devoid of erotic content as boxing, or wrestling, or other non-sexual physical contacts among older persons. Nevertheless, at a very early age the child learns that there are social values attached to these activities, and his emotional excitation while engaged in such play must involve reactions to the mysterious, to the forbidden, and to the socially dangerous performance, as often as it involves true erotic response (Sears 1943). Some of the play in the younger boy occurs without erection, but some of it brings erection and may culminate in true orgasm.

In pre-adolescent and early adolescent boys, erection and orgasm are easily induced. They are more easily induced than in older males. Erection may occur immediately after birth and, as many observant mothers (and few scientists) know, it is practically a daily matter for all small boys, from earliest infancy and up in age (Halverson 1940). Slight physical stimulation of the genitalia, general body tensions, and generalized emotional situations bring immediate erection, even when there is no specifically sexual situation involved. The very generalized nature of the response becomes evident when one accumulates a list of the apparently non-sexual stimuli which bring erection. Ramsey (1943) has published such a list gathered from a group of 291 younger boys which he had interviewed, and his histories provide part of the data which we have used in the present volume. A complete tabulation, based on the total sample now available on all cases, is as follows:

Among these younger boys, it is difficult to say what is an erotic response and what is a simple physical, or a generalized emotional situation.

Specifically sexual situations to which the younger boys respond before adolescence include the following:

|

SEXUAL SOURCES OF EROTIC RESPONSE AMONG 212 PRE-ADOLESCENT BOYS |

|||

| Seeing females | 107 | Physical contact with females | 34 |

| Thinking about females | 104 | Love stories in books | 32 |

| Sex jokes | 104 | Seeing genitalia of other males | 29 |

| Sex pictures | 89 | Burlesque shows | 23 |

| Pictures of females | 76 | Seeing animals in coitus | 21 |

| Females in moving pictures | 55 | Dancing with females | 13 |

| Seeing self nude in mirror | 47 | ||

The above table is based on the histories of 212 boys who were preadolescent at the time of interview. Since the questions were not systematically put in all the pre-adolescent cases, the figures represent frequencies of answers in particular boys, and should not be taken as incidence figures for the population as a whole.

The record suggests that the physiologic mechanism of any emotional response (anger, fright, pain, etc.) may be the basic mechanism of sexual response. Originally the pre-adolescent boy erects indiscriminately to the whole array of emotional situations, whether they be sexual or non-sexual in nature. By his late teens the male has been so conditioned that he rarely responds to anything except a direct physical stimulation of genitalia, or to psychic situations that are specifically sexual. In the still older male even physical stimulation is rarely effective unless accompanied by such a psychologic atmosphere. The picture is that of the psychosexual emerging from a much more generalized and basic physiologic capacity which becomes sexual, as an adult knows it, through experience and conditioning.

The most specific activities among younger boys involve genital exhibition and genital contacts with other children. Something more than a half (57%) of the older boys and adults recall some sort of pre-adolescent sex play. This figure is much higher than some other students have found (e.g., Hamilton 1929); but it is probably still too low, for 70 per cent of the pre-adolescent boys who have contributed to the present study have admitted such experience, and there is no doubt that even they forget many of their earlier activities. It is not improbable that nearly all boys have some pre-adolescent genital play with other boys or with girls. Only about one-fifth as many of the girls have such play.

Most of this pre-adolescent sex play occurs between the ages of eight and thirteen (Table 24, Figure 25), although some of it occurs at every age from earliest childhood to adolescence. For a quarter of the boys who have such play, the activity is limited to a single year (24.3%) or two (17.9%) or three (10.4%) in pre-adolescence (Table 25). For many of them there is only a single experience. A third of the active males (36.2%) continue the play for five years or more. That the activity does not extend further is clearly a product of cultural restraints, for pre-adolescent sex play in the other anthropoids is abundant and continues into adult performance (Bingham 1928). Most of the play takes place with companions close to the subject’s own age. On the other hand, the boy’s initial experience is often (although not invariably) with a slightly older boy or girl. Older persons are the teachers of younger people in all matters, including the sexual. The record includes some cases of pre-adolescent boys involved in sexual contacts with adult females, and still more cases of pre-adolescent boys involved with adult males. Data on this point were not systematically gathered from all histories, and consequently the frequency of contacts with adults cannot be calculated with precision.

Homosexual Play. On the whole, the homosexual child play is found in more histories, occurs more frequently, and becomes more specific than the pre-adolescent heterosexual play. This depends, as so much of the adult homosexual activity depends, on the greater accessibility of the boy’s own sex (Table 26). In the younger boy, it is also fostered by his socially encouraged disdain for girls’ ways, by his admiration for masculine prowess, and by his desire to emulate older boys. The anatomy and functional capacities of male genitalia interest the younger boy to a degree that is not appreciated by older males who have become heterosexually conditioned and who are continuously on the defensive against reactions which might be interpreted as homosexual.

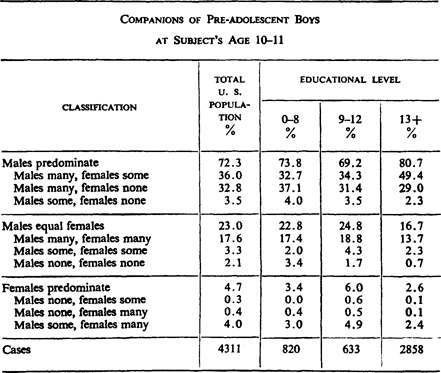

Table 26. Sex of companions of pre-adolescent boys

A record of the boy’s associates, in his play and social activities, when he is 10-11 years of age.

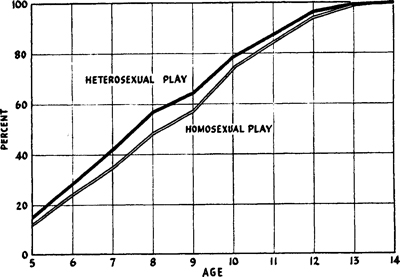

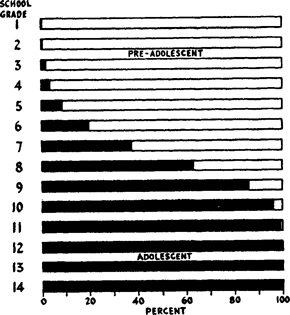

About half of the older males (48%), and nearer two-thirds (60%) of the boys who were pre-adolescent at the time they contributed their histories, recall homosexual activity in their pre-adolescent years. The mean age of the first homosexual contact is about nine years, two and a half months (9.21 years) (Table 28, Figures 25, 26).

The order of appearance of the several homosexual techniques is: exhibition of genitalia, manual manipulation of genitalia, anal or oral contacts with genitalia, and urethral insertions (Table 27). Exhibition is much the most common form of homosexual play (in 99.8 per cent of all the histories which have any activity). It appears in the sex play of the youngest children, where much of it is incidental, definitely casual, and quite fruitless as far as erotic arousal is concerned. The most extreme development of exhibitionism occurs among the older pre-adolescents and the younger adolescent males who have discovered the significance of self masturbation and may have acquired proficiency in effecting orgasm. By that time there is a social value in establishing one’s ability, and many a boy exhibits his masturbatory techniques to lone companions or to whole groups of boys. In the latter case, there may be simultaneous exhibition as a group activity. The boy’s emotional reaction in such a performance is undoubtedly enhanced by the presence of the other boys. There are teenage boys who continue this exhibitionistic activity throughout their high school years, some of them even entering into compacts with their closest friends to refrain from self masturbation except when in the presence of each other. In confining such social performances to self masturbation, these boys avoid conflicts over the homosexual. By this time, however, the psychic reactions may be homosexual enough, although it may be difficult to persuade these individuals to admit it.

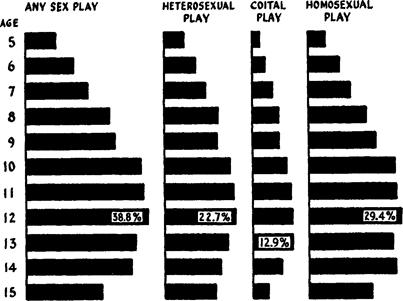

Figure 25. Percent of males involved in sex play at each pre-adolescent age

Data all corrected for U. S. Census distribution.

Exhibitionism leads naturally into the next step in the homosexual play, namely the mutual manipulation of genitalia. Such manipulation occurs in the play of two-thirds (67.4%) of all the pre-adolescent males who have any homosexual activity (Table 27). Among younger pre-adolescents the manual contacts are still very incidental and casual and without any recognition of the emotional possibilities of such experience. Only a small portion of the cases leads to the sort of manipulation which does effect arousal and possibly orgasm in the partner. Manual manipulation is more likely to become so specific if the relation is had with a somewhat older boy, or with an adult. Without help from more experienced persons, many preadolescents take a good many years to discover masturbatory techniques that are sexually effective.

Table 27. Techniques in pre-adolescent sex play

In order to determine the percent of the total pre-adolescent male population which has experience with any particular technique, multiply the figure in Column 3 (which shows the percent of the total population which has any kind of heterosexual or homosexual experience) by the incidence figure for the. particular technique under consideration.

Anal intercourse is reported by 17 per cent of the pre-adolescents who have any homosexual play. Anal intercourse among younger boys usually fails of penetration and is therefore primarily femoral. Oral manipulation is reported by nearly 16 per cent of the boys (Table 27). Among younger boys, erotic arousal is less easily effected by oral contacts, more easily effected by manual manipulation. The anal and oral techniques are limited as they are because even at these younger ages there is some knowledge of the social taboos on these activities; and it is, in consequence, probable that the reported data are considerable understatements of the activities which actually occur.

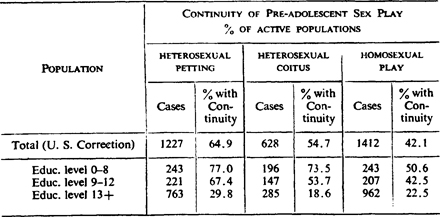

Pre-adolescent homosexual play is carried over into adolescent or adult activity in something less than a half of all the cases (Table 29). There are differences between social levels. In lower educational levels, the chances are 50–50 that the pre-adolescent homosexual play will be continued into adolescence or later. For the group that will go to college, the chances are better than four to one that the pre-adolescent activity will not be followed by later homosexual experience. In many cases, the later homosexuality stops with the adolescent years, but many of the adults who are actively and more or less exclusively homosexual date their activities from preadolescence. In a later volume these data will be examined in more detail, in connection with an analysis of the factors involved in the development of a heterosexual-homosexual balance.

Figure 26. A g e of first pre-adolescent sexual experience

Each curve an ogive, where 100 per cent is the total number of boys who ever have such experience.

Heterosexual Play. The average age for beginning pre-adolescent heterosexual play is about eight years and ten months (a mean of 8.81 years) (Table 28, Figures 25, 26). This is approximately five months earlier than the average age for the beginning of homosexual play; but heterosexual activity, nonetheless, does not occupy quite as much of the attention of the preadolescent boys. It is found in 40 per cent of the pre-adolescent histories.

Just as with the homosexual, the heterosexual play begins with the exhibition of genitalia; and of those pre-adolescent boys who have any sex play with girls, about 99 per cent engage in such exhibition (Table 27). For nearly 20 per cent of the boys, this is the limit of the activity. There is considerable curiosity among children, both male and female, about the genitalia of the opposite sex, fostered, if not primarily engendered, by the social restrictions on inter-sexual display. The boy is incited by the greater care which many parents exercise in covering the genitalia of the girls in the family—a custom which reaches its extreme in some other cultures where the boys may go completely nude until adolescence, while the girls are carefully clothed at least from the ages of four or five.

Of those pre-adolescent boys who have any heterosexual play, 81.4 per cent carry it to the point of manually manipulating the genitalia of the female (Table 27). For many of the youngest boys this is even more incidental than the manual manipulation which occurs in homosexual contacts. Among certain groups, particularly in upper social levels, the children sometimes lack information on coitus, and there may be no comprehension that there are possibilities in heterosexual activity other than those afforded by manual contacts. There are vaginal insertions which involve objects of various sorts, but most often they are finger insertions. Pre-adolescent attempts to effect genital union occur in nearly 22 per cent of all male histories, which is over half (55.3%) of the histories of the boys who have any pre-adolescent play. On this point, there are considerable differences between social levels (Table 27). Three-quarters (74.4%) of the boys who will never go beyond eighth grade try such pre-adolescent coitus, but such experience is had by only one-quarter (25.7%) of the pre-adolescent boys of the group which will ultimately go to college (Chapter 10).

The lower level boy has considerable information and help on these matters from older boys or from adult males, and in many cases his first heterosexual contacts are with older girls who have already had experience. Consequently, in this lower level, pre-adolescent contacts often involve actual penetration and the children have what amounts to real intercourse. The efforts of the upper level boys are less often successful, in many cases amounting to little more than the apposition of genitalia. With the lower level boy, pre-adolescent coitus may occur with some frequency, and it may be had with a variety of partners. For the upper level boy, the experience often occurs only once or twice, and with a single partner or two. These differences between patterns at different social levels, even in pre-adolescence, are of the utmost significance in any consideration of a program of sex education (Chapter 10).

Oral contacts with females occur in only 8.9 per cent of the boys who have pre-adolescent heterosexual play. Oral contacts are more likely to occur where the girl is older, or where an adult woman is involved. There is considerable evidence that oral contacts are recognized as taboo, even at pre-adolescent ages.

Table 29. Continuity of pre-adolescent sex play with adolescent activity

Pre-adolescent heterosexual play is carried over into corresponding adolescent activities in nearly two-thirds of the cases (Table 29). There is a somewhat higher carry-over of heterosexual petting, a lesser carry-over of heterosexual coitus. Again there are tremendous differences between social levels. If coitus is had by a pre-adolescent boy who will never go beyond eighth grade in school, the chances are three to one that he will continue such activity, without any major break, in his adolescent and adult years. If the boy who has pre-adolescent coitus belongs to the group that will ultimately go to college, the chances are more than four to one that the activity will not be continued in his adolescent years. Community attitudes on these matters are already exerting an influence on the preadolescent boy.

Animal Contacts. Animal contacts are largely confined to farm boys. Of the boys who will ever be involved, a third have had their first contacts by nine years of age; but between 10 and 12 there is a more rapid increase in the active incidence figures. The level which is reached in these years is never again equalled, either in pre-adolescence or in adolescent or in later years. In about a third of the cases, there is direct continuity between the pre-adolescent and the adolescent experiences with animal intercourse.

In the technical literature there seem to be only a few references (e.g., Moil 1912, Merrill 1918, Moses 1922, Krafft-Ebing 1924, Rohleder 1921, Hamilton 1929:427) to the possibility of the pre-adolescent child experiencing orgasm. But, as we have already indicated, orgasm is not at all rare among pre-adolescent boys, and it also occurs among pre-adolescent girls. Since this significant fact has not been well established in scientific publication, it will be profitable to record here the nature of the data for the male in some detail.

Table 30. Pre-adolescent eroticism and orgasm

All data based on memory of older subjects, except in the column entitled “data from other subjects.” In the later case, original data gathered by certain of our subjects were made available for use in the present volume. Of the 214 cases so reported, all but 14 were subsequently observed in orgasm (see Table 31).

Pre-adolescent boys, since they are incapable of ejaculation, may be as uncertain as some inexperienced females in their recognition of orgasm. In consequence, the record on such early experience is incomplete in most of the histories, and it is as yet impossible to make any exact calculation of the incidence or frequency in the population as a whole. Nevertheless, some of the younger boys who have contributed to the present study have described what is unmistakably sexual orgasm in their pre-adolescent histories, and a larger number of adults remember such experience (Table 30).

Table 31. Ages of pre-adolescent orgasm

Based on actual observation of 317 males.

Better data on pre-adolescent climax come from the histories of adult males who have had sexual contacts with younger boys and who, with their adult backgrounds, are able to recognize and interpret the boys’ experiences. Unfortunately, not all of the subjects with such contacts in their histories were questioned on this point of pre-adolescent reactions; but 9 of our adult male subjects have observed such orgasm. Some of these adults are technically trained persons who have kept diaries or other records which have been put at our disposal; and from them we have secured information on 317 pre-adolescents who were either observed in self masturbation, or who were observed in contacts with other boys or older adults. The record so obtained shows a considerable sexual capacity among these boys. Before presenting the data, however, it should be emphasized that this is a record of a somewhat select group of younger males and not a statistical representation for any larger group. These records are based on more or less uninhibited boys, most of whom had heard about sex and seen sexual activities among their companions, and many of whom had had sexual contacts with one or more adults. Most of them knew of orgasm as the goal of such activity, and some of them, even at an early age, had become definitely aggressive in seeking contacts. Most boys are more inhibited, more restricted by parental controls. Many boys remain in ignorance of the nature of a complete sexual response until they become adolescent.

Orgasm has been observed in boys of every age from 5 months to adolescence (Table 31). Orgasm is in our records for a female babe of 4 months. The orgasm in an infant or other young male is, except for the lack of an ejaculation, a striking duplicate of orgasm in an older adult. As described earlier in this chapter, the behavior involves a series of gradual physiologic changes, the development of rhythmic body movements with distinct penis throbs and pelvic thrusts, an obvious change in sensory capacities, a final tension of muscles, especially of the abdomen, hips, and back, a sudden release with convulsions, including rhythmic anal contractions—followed by the disappearance of all symptoms. A fretful babe quiets down under the initial sexual stimulation, is distracted from other activities, begins rhythmic pelvic thrusts, becomes tense as climax approaches, is thrown into convulsive action, often with violent arm and leg movements, sometimes with weeping at the moment of climax. After climax the child loses erection quickly and subsides into the calm and peace that typically follows adult orgasm. It may be some time before erection can be induced again after such an experience. There are observations of 16 males up to 11 months of age, with such typical orgasm reached in 7 cases. In 5 cases of young pre-adolescents, observations were continued over periods of months or years, until the individuals were old enough to make it certain that true orgasm was involved; and in all of these cases the later reactions were so similar to the earlier behavior that there could be no doubt of the orgastic nature of the first experience.

While the records for very young boys are fewer than for boys nearer the age of adolescence, and while the calculations for these youngest cases are consequently less reliable, the data do show a gradual increase, with advancing age, in the percentage of cases able to reach climax: 32 per cent of the boys 2 to 12 months of age, more than half (57.1%) of the 2- to 5- year olds, and nearly 80 per cent of the pre-adolescent boys between 10 and 13 years of age (inclusive) came to climax. Half of the boys had reached climax by 7 years of age (nearly half of them by 5 years), and two-thirds of them by 12 years of age. The observers emphasize that there are some of these pre-adolescent boys (estimated by one observer as less than one-quarter of the cases), who fail to reach climax even under prolonged and varied and repeated stimulation; but, even in these young boys, this probably represents psychologic blockage more often than physiologic incapacity.

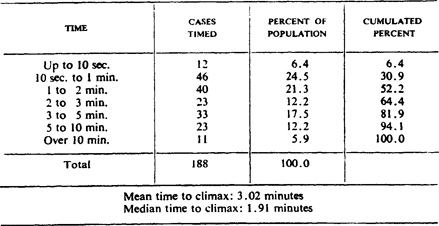

Table 32. Speed of pre-adolescent orgasm

Duration of stimulation before climax; observations timed with second hand or stop watch. Ages range from five months of age to adolescence.

In the population as a whole, a much smaller percentage of the boys experience orgasm at any early age, because few of them find themselves in circumstances that test their capacities; but the positive record on these boys who did have the opportunity makes it certain that many infant males and younger boys are capable of orgasm, and it is probable that half or more of the boys in an uninhibited society could reach climax by the time they were three or four years of age, and that nearly all of them could experience such a climax three to five years before the onset of adolescence.

Erection is much quicker in pre-adolescent boys than in adults, although the speed with which climax is reached in pre-adolescent males varies considerably in different boys (Table 32), just as it does in adults. There are two-year olds who come to climax in less than 10 seconds, and there are two-year olds who may take 10 or 20 minutes, or more. There is a similar range among pre-adolescents of every other age. The mean time required to reach climax was almost exactly 3 minutes, and the median time was under 2 minutes. From earliest infancy until the middle twenties there is no effect of age on this point, although beyond that older males slow up in speed of response (Chapter 6).

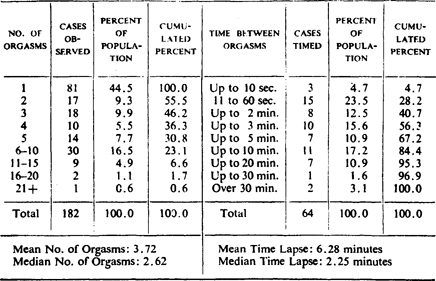

Table 33. Multiple orgasm in pre-adolescent males

Based on a small and select group of boys. Not typical of the experience, but suggestive of the capacities of pre-adolescent boys in general.

The most remarkable aspect of the pre-adolescent population is its capacity to achieve repeated orgasm in limited periods of time. This capacity definitely exceeds the ability of teen-age boys who, in turn, are much more capable than any older males (Tables 33, 34, 48, Figure 36). Among 182 pre-adolescent boys on whom sufficient data are available, more than half (55.5%, 138 cases) readily reached a second climax within a short period of time, and nearly a third (30.8%) of all these 182 boys were able to achieve 5 or more climaces in quite rapid succession (Tables 32–34). It is certain that a higher proportion of the boys could have had multiple orgasm if the situation had offered. Among 64 cases on which there are detailed reports, the average interval between the first and second climaces ranged from less than 10 seconds to 30 minutes or more, but the mean interval was only 6.28 minutes (median 2.25 minutes) (Table 33). There are older males, even in their thirties and older, who are able to equal this performance, but a much higher proportion of these pre-adolescent males are so capable. Even the youngest males, as young as 5 months in age, are capable of such repeated reactions. Typical cases are shown in Table 34. The maximum observed was 26 climaces in 24 hours, and the report indicates that still more might have been possible in the same period of time.

About a third of these boys remain in erection after the first orgasm and proceed directly to a second contact. There is another third that stays in erection but experiences some physical and erotic let-down before trying to achieve a second orgasm. In another third, the erection quickly subsides and there is a complete disappearance of arousal as soon as orgasm is reached. Any repetition depends upon new arousal, and that may not be possible for some minutes or hours after the original experience. Among adult males, more individuals belong to this last class, and a much smaller number remains in erection until there is a repetition of the sexual contact.

Table 34. Examples of multiple orgasm in pre-adolescent males

Some instances of higher frequencies.

These data on the sexual activities of younger males provide an important substantiation of the Freudian view of sexuality as a component that is present in the human animal from earliest infancy, although it gives no support to the Freudian concept of a pre-genital stage of generalized erotic response that precedes more specific genital activity; nor does it show any necessity for a sexually latent or dormant period in the later pre-adolescent years, except as such inactivity results from parental and social repressions of the growing child. It would seem that analysts have been correct in considering these capacities for childhood sexual development, or their suppression, as prime sources of adult patterns of sexual behavior and of many of the characteristics of the total personality. There are, of course, some who have questioned the truly sexual nature of the child’s experiences. Moore, for instance, remarks (1943, p. 45): “One would think that psychoanalysts would have confirmed their theories of infantile emotionality by a careful observation and study of large numbers of children … but I have been unable to find any such study by a member of the psychoanalytic school.” And again (p. 48): “As to the presence of specific sexual experience in infancy and early childhood, we shall never be able to solve the problem by appealing to the introspection of the infant and the child. Neither does the memory of the adult reach back to those early years so that he can tell us whether or not it is really true that in infancy and early childhood he experienced specific sexual excitement, and that this was repressed and became latent, as Freud maintained.”

Moore leans heavily on Bridges (1936) and Búhler (1931) to argue (pp. 46–48) that the earliest manifestations of emotion may be labelled distress or delight; but that, although young children may perform “acts similar to masturbation” and seek a partner for genital manipulation, “there is no evidence … that these acts are accompanied by specific sexual pleasure … even though there are signs that the child in some manner enjoys them.” The conclusion is that although the child is capable of a tender personal love, it is of a non-erotic character and has nothing to do with the beginnings of sexuality. Adding data from endocrinologic sources, he concludes that specifically sexual behavior is the product of biologic growth and of experience.

Complying with the scientifically fair demand for records from trained observers, and answering Moore’s further demand (p. 71) that “writers … test their theories … by empirical study and statistical procedures,” we have now reported observations on such specifically sexual activities as erection, pelvic thrusts, and the several other characteristics of true orgasm in a list of 317 pre-adolescent boys ranging between infants of five months and adolescence in age. Adding the records based on the memories of older subjects concerning their own, and often clearly established, early experiences, there is a record of orgasm in 604 pre-adolescent boys (Tables 30 and 31 combined). The existence of such an early capacity is exactly what students of animal behavior have reported for other mammals (Beach 1947), and it is, therefore, not surprising to find it in the human infant. Important as learning and conditioning may be in the later development of specific types of sexual techniques and in the socio-sexual adjustments of the adolescent and adult, it must be accepted as a fact that at least some and probably a high proportion of the infant and older pre-adolescent males are capable of specific sexual response to the point of complete orgasm, whenever a sufficient stimulation is provided.

While the sexual history of the human male thus begins in earliest infancy and develops continuously to its maximum activity somewhere between the middle teens and twenty years of age (Chapter 7), the steady progress of the development is, among primates, accelerated in a period of growth which is known as adolescence.

During adolescence the young male rather suddenly acquires physical stature and adult conformation, and he begins to produce an ejaculate which contains mature sperm and which can, therefore, effect fertilization when in contact with the egg of a mature female. These are the most obvious and the biologically significant developments of the period; but the student of human sexual behavior is concerned with adolescence, and must consider its physical signs and stigmata, not because the physical developments are in themselves of prime importance, but because adolescence marks what is, in most individuals, a considerable break between the patterns of sexual activity of the pre-adolescent boy and the patterns of the older boy or adult. The sexual life of the younger boy is more or less a part of his other play; it is usually sporadic, and (under the restrictions imposed by our social structure) it may be without overt manifestation in a fair number of cases. The sexual life of the older male is, on the other hand, an end in itself, and (in spite of our social organization) in nearly all boys its overt manifestations become frequent and regular, soon after the onset of adolescence.

In a portion of the cases the pre-adolescent sexual activities have provided the introduction to adult activities: simple heterosexual play turns into more sophisticated petting; pre-adolescent attempts at intercourse lead to adult coitus; some of the pre-adolescent homosexual play leads into similar adult contacts. This is true in about 50 per cent of all male histories which include any pre-adolescent play (Table 29). In an equal number of the cases the pre-adolescent play ends well before or with the onset of adolescence, and adolescent and more adult sexual activities must start from new points, newly won social acquirements, newly learned techniques of physical contact, in many cases the newly adolescent boy’s capacity to ejaculate, his newly acquired physical characters of other sorts, do something to him which brings child play to an end and leaves him awkward about making further socio-sexual contacts. The psychologic and social factors involved in this break between pre-adolescent sexuality and adult sexual activity are questions that will deserve considerable study by some qualified student. Those boys in whom child play does merge directly into adult activity are more often from less inhibited, lower social levels (Table 29).

For all boys, the experiences of pre-adolescence, whether directly continued or not, must provide considerable conditioning which encourages or inhibits their sexual development in adolescent and in more adult years.

Adolescence is a period of time, and not a particular point in the life of the growing boy. It involves a whole series of developmental changes, some of which come earlier, some later in the course of events. Individuals differ materially in the ages at which they experience the first of these events, and somewhat in the sequence in which the other transformations follow (Table 35, Figure 27).

Among most boys, the physical changes of adolescence come on more or less abruptly, usually between the ages of 11 and 14, and in that period their sexual activities are suddenly stepped up until, within another few years, most of them reach the maximum rate of their whole lives (Chapter 7). Among most females, as the data in another volume will show, sexual development comes on more gradually than in the male, is often spread over a longer period of time, and does not reach its peak until a good many years after the boy is sexually mature.

Chiefly within the past decade, several studies based on physical examinations of boys and girls have given precise information on the variation and average ages involved in the developmental changes of adolescence. Some of the studies (Baldwin 1916, Crampton 1908, 1944, Dimock 1937, Kubitschek 1932, Schonfeld 1943) have been cross-sectional, based on examinations of numbers of children of each age group; some, utilizing a longitudinal approach, have involved the more exact task of following the development of individual cases over a period of successive years (Boas 1932, Dearborn and Rothney 1941, Greulich et al. 1938, Jones 1944, Meredith 1935, 1939, Shuttleworth 1937, 1939). The latter, however, are not always the more fruitful studies, for such observations are tedious, and long-time contacts so often fail that only a few subjects can be followed through to conclusion.

The studies which are based on direct physical examinations may be accepted as more accurate than our own, for we have relied for the most part on the memory of persons who were removed by various and sometimes long periods of years from the events which they were recalling; but it is interesting to find that our records give averages and total curves which are not significantly different from the data in the observational studies (Chapter 4, Table 15, Figure 15). According to the memory of our subjects, physical changes in the adolescent boy usually proceed as follows: Beginning of development of pubic hair, first ejaculation, voice change, initiation of rapid growth in height, and, after some lapse of time, completion of growth in height (Table 35, Figure 27). Similar data have been previously published from our laboratory (Ramsey 1943a) for a small sample of 291 younger males who were in or near the beginning of adolescence at the time of the study. Our present, larger sample gives curves that are in most respects in close agreement with the Ramsey series; but his records show voice change beginning sooner after the onset of pubic hair growth and before the first ejaculation (also see Jerome 1937, Curry 1940, Pedrey 1945). The Ramsey data indicate that “breast knots,” or subareolar nodes which are homologous to those which regularly occur in the female, are found in a t least one-third of these boys between the ages of 12 to 14 (Jung and Shafton 1935, Ramsey 1943). Physical examinations (Meredith 1935, 1939) on limited and selected series of males have shown that sudden body growth may begin nearer the time of pubic hair development than our older subjects recall. There are many individual differences in the sequence of events.

The published studies of younger boys almost completely lack data on the most significant of all adolescent developments, the occurrence of the first ejaculation. There have been several attempts to secure information by indirect methods, including a technique of examining for sperm in early morning samples of urine (Baldwin 1928). These methods will not soon supply any quantity of data; and the only other sources of information on this point have been the records obtained from the recall of subjects in the previously published case history studies. This material is now augmented by a considerable record based on the memory of persons who have contributed to the present study, and on an important body of data from certain of our subjects who have observed first ejaculation in a list of several hundred boys.

The earliest ejaculation remembered by any of our apparently normal males was at 8 (three males). We have the history of one unusual boy (a Negro, interviewed when he was 12) who fixed 6 as his age at first ejaculation. The boy had been diagnosed by the clinician as “idiopathically precocious in development.” In the literature (e.g., Ford and Guild 1937, Young 1937, Weinberger and Grant 1941) there are clinical cases for still younger ages, most of them involving endocrine pathologies. Pubic hair has been recorded for one year of age and non-motile sperm in urine after prostate massage at four and a half years. Eight, however, is the earliest age of first ejaculation known for apparently normal males.

Except for the 6 cases of life-long ejaculatory impotence referred to earlier in the present chapter, the latest ages of first ejaculation reliably recorded in the histories are 21 for two apparently healthy males, 24 for a religiously inhibited individual, and 22 and after 24 for two males with hormonal deficiencies. The spread between the youngest and the oldest non-endocrine case is 16 years. A variety of educational and social problems arise out of these differences between chronologic and sexual age. For instance, an occasional boy in third or fourth grade is sexually as mature as an occasional senior in college (Table 36, Table 36, Figure 28).

Table 36. School grade at adolescence

Most of the boys reaching adolescence in the lowest grades are retarded individuals of more advanced age than the average in the grade.

In spite of this spread in the population as a whole, the record shows (Table 35, Figure 27) that about 90 per cent of the males ejaculate for the first time between the ages of 11 and 15 (inclusive). This is an age range of 5 years. At the end of the seventh grade in school, about a third (37.5%) of the boys are adolescent; by the end of the tenth grade, nearly all of them (96.5%) are so (Table 36, Figure 28). The average boy turns adolescent in the eighth grade (a mean grade of 8.33).

The mean age of first orgasm resulting in ejaculation is 13 years, 10 1/2 months (13.88 years). On this point, the male data are in striking contrast with preliminary calculations on the female. By 15 years of age, 92 per cent of the males have had orgasm, but at that same age less than a quarter of the females have had such experience; and the female population is 29 years old before it includes as high a percentage of experienced individuals as is to be found in the male curve at 15. Precise data on the female must await the publication of a later volume.

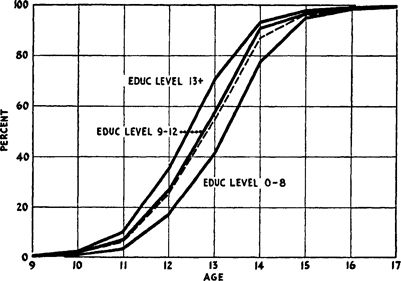

Figure 28. Percent of adolescent boys in each school grade

In the male the age of first ejaculation varies by nearly a year between different educational (social) levels: the mean is 14.58 for boys who never go beyond eighth grade in school, 13.97 for boys who go into high school but not beyond, and 13.71 for boys who will go to college (Table 37). The differences are probably the outcome of nutritional inequalities at different social levels, and they are in line with similar differences in mean ages of females at menarche, where nutrition is usually considered a prime factor effecting variation.

Table 37. Ages at onset of adolescence

Comparing development for three groups defined in accordance with the years of schooling ultimately attained. Figures for the U. S. population are based on the figures for the sample population corrected for the educational distribution shown in the U. S. Census for 1940.

Since so many developments are involved, it is difficult to mark a single point at which an individual may be said to have begun adolescence. In the case of the male, it is not customary to attach that distinction to the very first appearance of any adolescent change, but to pay more attention to the time of first ejaculation, or to evidence that the boy would be capable of ejaculation if the proper opportunity were at hand. We have, to a large degree, followed this convention, in order that the calculations may be compared with other published figures. If the year of first ejaculation coincides with the year in which the pubic hair first appears, with the time of onset of growth in height, or with other developments, there is no question involved. If first ejaculation follows these other events by a year or more, the record must be examined to see whether there was overt sexual behavior which would have provided previous opportunity for orgasm, and the reliability of the record on the other adolescent characters must be checked. First ejaculation which is derived from nocturnal dreams usually occurs a year or more after the onset of other adolescent characters and after ejaculation would have been possible by other means, if circumstances had allowed. Taking these several things into account, “adolescent ages” have been assigned to each of the subjects in the present study, and the distribution is shown in Table 37, Figure 29. When computed thus the average age of onset of adolescence in the white male is about 13 years and 7 months.

Figure 29. Age at onset of adolescence, by three educational levels

Curve for total population, on the basis of the U. S. Correction, is shown in the broken line.

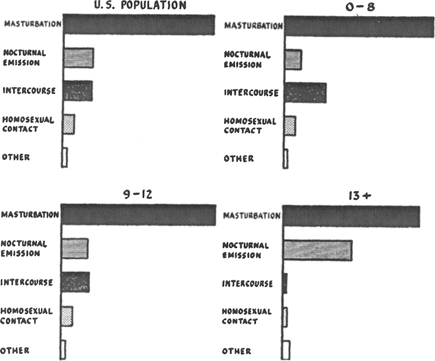

For the U. S. population, the sources of first ejaculation (Table 38, Figure 30) are, in order of frequency, masturbation (in about two-thirds of the males), nocturnal emissions (in an eighth of the cases), heterosexual coitus (in one boy out of eight), and homosexual contacts (in one boy out of twenty), with spontaneous ejaculation, petting to climax, and intercourse with other animals as less frequent stimuli for the initial experience (cf. Rohleder 1921). There are considerable differences in first sources in different educational levels. The highest incidence of masturbation as the first source of ejaculation occurs among the boys who will leave school between the ninth and twelfth grades, the highest incidence of nocturnal emissions as the first source occurs among the boys who will subsequently go to college, and the highest incidence of heterosexual intercourse as the first source occurs among the boys who never get beyond the eighth grade in school.

Table 38. Sources of first ejaculation

The final column shows percent involved if each educational level were represented in the proportions shown in the 1940 Census.

While “spontaneous” ejaculation, meaning ejaculation without specific genital contact, is the first source of experience for only a small percentage of the boys (0.81%), the items which stimulate such response constitute an interesting list which includes non-sexual and more definitely sexual emotional situations, and a variety of circumstances which involve physical tension. In a number of cases (e.g., wrestling, prolonged sitting while reading a book) both physical tension and psychologic stimulation are probably involved. The list includes a number of the non-sexual sources of erotic stimulation listed earlier in this chapter, but the following tabulation shows items which are responsible for actual ejaculation among these early adolescent boys.

| SOURCES OF FIRST SPONTANEOUS EJACULATION | |

| Chiefly Physical Stimulation | |

| Sitting at desk | Sliding on chair |

| Sitting in classroom | Sliding down a bannister |

| Lying still on floor | Tension in gymnastics |

| Lying still in bed | Chinning on bar |

| Urination | Climbing tree, pole or rope |

| At toilet | (A rather common source) |

| General stimulation in bath | Wrestling with female |

| Moving water in bath | Wrestling with male |

| General stimulation with towel | Riding an automobile |

| General skin irritation | Tight clothing |

| Vibration of a boat | |

| Chiefly Emotional Stimulation | |

| Day dreaming | Milking a cow |

| Reading a book | When scared at night |

| Walking down a street | When bicycle was stolen |

| In vaudeville | A bell ringing |

| In movies | An exciting basketball game |

| Kissed by female | Trying to finish an examination in school |

| Watching petting | Reciting in front of class |

| Peeping at nude female | Injury in a car wreck |

| Sex discussion at YMCA | |

Beyond earliest adolescence, it is a rare male who ejaculates when no physical contact is involved. Many teen-age and even older males come to climax in heterosexual petting that may not involve genital contacts; but general body contact, or at least lip contact, is usually included in such situations. There are stray cases of males of college age ejaculating under the excitement of class recitation or examination, in airplanes during combat, and under other rare circumstances. There are two cases of older males who could reach climax by deliberate concentration of thought on erotic situations; but such spontaneous ejaculation is almost wholly confined to younger boys just entering adolescence.

After the initial experience in ejaculation, practically all males become regular in their sexual activity. This involves monthly, weekly, or even daily ejaculation, which occurs regularly from the time of the very first experience. Among approximately 4600 adolescent males, less than one per cent (about 35 cases) record a lapse of a year or more between their first experience and the adoption of a regular routine of sexual activity. This means that more than 99 per cent of the boys begin regular sexual lives immediately after the first ejaculation. In this respect, the male is again very different from the female, for there are many women who go for periods of time ranging from a year to ten or twenty years between their earlier experiences and the subsequent adoption of regularity in activity. The male, in the course of his life, may change the sources of his sexual outlet, and his frequencies may vary through the weeks and months, and over a span of years, but almost never is there a complete cessation of his activity until such time as old age finally stops all response.

Figure 30. Sources of first ejaculation

Calculated for total population corrected for U. S. Census distribution, and for boys of the grade school (0–8), high school (9–12), and college (13+) levels.