In physiology, endocrinology, genetics, and still other fields, biologists often go to considerable pains to restrict their experimental material to animals of particular species, to particular age groups, and to individuals that are reared on a uniform diet and kept under strictly controlled laboratory conditions. Different hereditary strains of a single species may give different results in a physiologic experiment; and, in many laboratories, stocks are restricted to the progeny of particular pairs of pedigreed ancestors. In studies of human behavior, there is even more reason for confining generalizations to homogeneous populations, for the factors that affect behavior are more abundant than those that affect simpler biologic characters, and there are, in consequence, more kinds of populations to be reckoned with. Nevertheless, restrictions of psychologic and sociologic studies to clearly defined groups have rarely been observed (McNemar 1940), perhaps because we have not, heretofore, known what things effect variability in a human population and how important they are in determining what people do.

There are at least eleven factors which are of primary importance in determining the frequency and sources of human sexual outlet. They are sex, race, age, age at onset of adolescence, marital status, educational level, the subject’s occupational class, the parental occupational class, rural-urban backgrounds, religious affiliations, and the extent of the subject’s devotion to religious affairs. The effects of these factors on the sexual histories of white males are discussed in the present volume. In view of the conclusions that these analyses now afford, it becomes apparent that generalizations concerning any aspect of human sexual behavior are uninterpretable unless they are limited to populations which are clearly defined in regard to the more important of the eleven items listed above.

In the sexual history of the male, there is no other single factor which affects frequency of outlet as much as age. Age affects the source of sexual outlet only indirectly, by way of its relation to marital status, to the availability of social contacts, to the liability to physical fatigue, and to the psychologic fatigue that comes as a result of the repetition of a particular sort of activity. But age more directly affects frequency of outlet. Age is so important that its effects are usually evident, whatever the marital status, the educational level, the religious background, or the other factors which enter the picture. It is logical, therefore, to begin the present analyses with a consideration of this factor.

As we have previously indicated (Chapter 5), there is sexual activity in the pre-adolescent male which may involve definite erotic arousal and actual orgasm; but the onset of regular sexual performance is usually coincidental with the onset of adolescence. Throughout the remainder of this volume, descriptions of sexual activity will apply to age periods that begin with adolescence and which extend, in the first instance, through 15 years of age, and which are five year periods from that point through the remainder of the individual’s history.

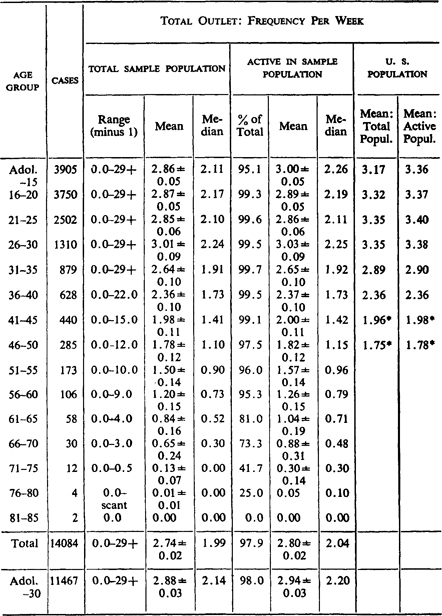

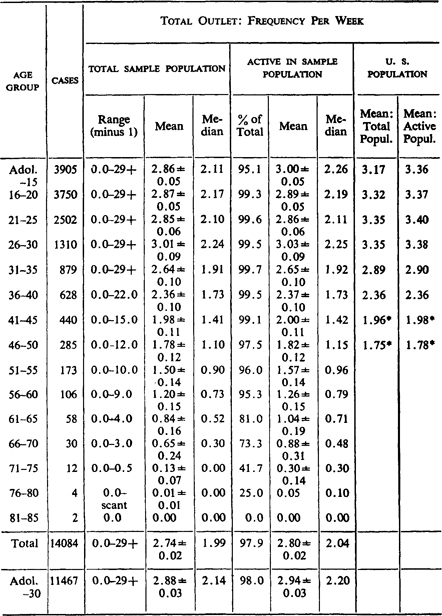

Over 95 per cent of the adolescent males are regularly active by 15 years of age (Table 44). Over 99 per cent of the adolescent and older males are active throughout the whole period from 16 to 45. In those 30 years, only 1 or 2 per cent of the male population is without regular and usually frequent outlet. After 45 there is a gradual but distinct drop in the number of active cases. These generalizations apply to all white males, whether single or married, and whatever their educational level or social background.

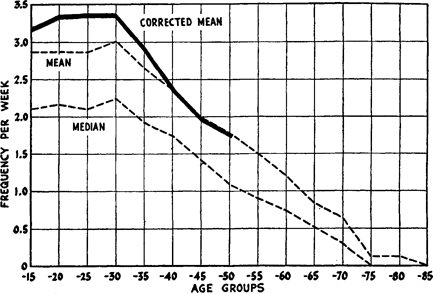

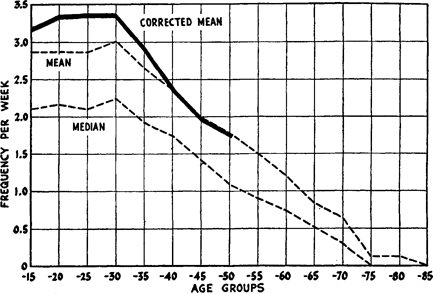

Maximum Activity. The maximum sexual frequencies (total outlet) occur in the teens. Frequencies then drop gradually but steadily into old age (Figure 34). Considering the active, single males in the population, the maximum mean frequencies are almost 3.4 per week (calculated for the U. S. population), which is almost exactly every other day in the week, month, or year (Figures 50–52). This rate is reached between adolescence and 20 years of age.

The means for the married males begin at their highest point, 4.8 per week, between 16 and 20 (Figures 50–52). Few males are married prior to 16, and there is not enough material to calculate statistically significant averages for any married group prior to that age. It is probable that in a population which married at an earlier age, the highest frequency on the curve would come in the earlier adolescent group; but, in our society as it is, the high point of sexual performance is, in actuality, somewhere around 16 or 17 years of age. It is not later. The data which have already been given on the sexual capacity of the pre-adolescent boy (Chapter 5) indicate that the peak of capacity occurs in the fast-growing years prior to adolescence; but the peak of actual performance is in the middle or later teens.

The earliest serious attempt to determine the age of maximum sexual activity, and the effect of age on sexual performance in the human male, was made by Pearl (1925). For his study, he had data from 213 men (average age 64.53 years) who felt they could recall the frequencies of marital intercourse in their earlier histories. The point of maximum sexual activity for this population was located in the 30–39 year period. For the younger ages, Pearl recorded definitely lower frequencies; but he concluded, as we have with our own data, that “the low frequency exhibited in this [younger] age period is in part and probably mainly an expression of an essentially social factor—lack of opportunity—rather than of anything physiological.” Of the men who were married in their twenties, 67 essayed to recall frequencies in that period; and 9 of the men who were married in their teens supplied data for that age. On these limited bases, Pearl concluded that “with approximate equality of opportunity at the different ages the peak of activity is in the 20–29 decade and that thereafter there is a steady decline”; but after inspecting the curve, he theoretically adds that “with unrestricted legitimate opportunity the peak of sex activity is prior to age 20.” Our own abundant data push the peak of the curve back, as Pearl predicted, into the late teens. Unfortunately, the conclusions which are more often quoted from the Pearl study are those based on his total population, with its maximal frequency between 30 and 39 years; whereas the curve which he derived from the smaller sample of married males, and his prediction that the maximum activity occurs before the twenties, prove to be the more correct.

Table 44. Total sexual outlet in relation to advancing age

These data are based on the total population, including single, married, and previously married groups. For each group calculated separately, see Table 60. Data for the U. S. population are based on a theoretic group with the marital status and educational levels shown in the U. S. Census for 1940. *Starred items are corrected for marital status only.

Figure 34. Frequency of total outlet in relation to age

Based on total population, including single, married, and previously married groups. Broken lines represent raw data; the solid black line represents the mean corrected for the U. S. Census distribution.

Social Significance. The identification of the sexually most active period as late adolescence will come as a surprise to most persons. General opinion would probably have placed it in the middle twenties or later. Certainly the average college student and the town boy of corresponding age will be startled to learn that their younger brothers who are still in high school surpass them in capacity and ofttimes in performance. By law, society provides a source of regular sexual outlet in marriage, in part because it recognizes the sexual need of the older male; but it fails to recognize that the teen-age boys are potentially more capable and often more active than their 35-year old fathers. Even among physicians and biologists, there has been a general opinion that sexual capacity develops gradually in early adolescence, reaches its maximum in the thirties or forties (the “prime of life”), passes a peak somewhere in a period which is considered a male climacteric, and drops abruptly into the inactivity and complete impotence of old age. It so happens that much of this picture is correct for the female, but it is certainly not the pattern in the male. The preoccupation of so many of the previous sex studies with the female has too often led to interpretation of the male by analogy, rather than by way of data taken directly from him.

This considerable activity and greater potentiality of the adolescent male pose a number of sociologic problems. In the normal course of events, the primitive human animal must have started his sexual activities with unrestrained pre-adolescent sex play, and begun regular intercourse well before the onset of adolescence. This is still the case in the other anthropoids (Hamilton 1914, Kempf 1917, Bingham 1928, Nowlis 1941), in some of the so-called primitive human societies which have not acquired particular sex taboos (Malinowski 1929, Ford 1945), and among such of the children in our society as escape the restrictions of social conventions (Chapter 5). The near-universality of adolescent sexual activity in our own Western European civilization down through the eighteenth century is poorly understood by those who have not made a study of earlier literature; but there is every indication in that literature, both sober and erotic, that the high capacity of the younger male was recognized and rather widely accepted until near the Victorian day in England. The problem of sexual adjustment for the younger male is one which has become especially aggravated during the last hundred years, and then primarily in England and in America, under an increasing moral suppression which has coincided with an increasing delay in the age of marriage. This has resulted in an intensification of the struggle between the boy’s biologic capacity and the sanctions imposed by the older male who, to put it objectively, is no longer hard-pressed to find a legalized source of sexual contact commensurate with his reduced demand for outlet.

The fact that the unmarried male still manages to find an outlet of 3.4 per week demonstrates the failure of the attempt to impose complete abstinence upon him. The sources of this outlet must be a matter of bewilderment to those who have supposed that most males remained continent until marriage. Nocturnal emissions do not provide any considerable portion of the orgasms (Chapter 15), in spite of the fact that many persons have wished that to be the case. Masturbation is a more frequent outlet among the upper social level males where, during the last two or three decades, it has been allowed as a not too immoral substitute for pre-marital intercourse; but most of the less-educated 85 per cent of the population still consider masturbation neither moral nor normal. For the mass of the unmarried boys, intercourse still provides the chief sexual activity (Chapter 10). This means that the majority of the males in the sexually most potential and most active period of their lives have to accept clandestine or illegal outlets, or become involved in psychologic conflicts in attempting to adjust to reduced outlets. With the data now available, biologists, psychologists, physicians, psychiatrists, and sociologists should be enabled to make better analyses of the problem which has heretofore been imposed on this unmarried male in his middle and late teens, and in his twenties.

The situation is complicated by the fact that the average adolescent girl gets along well enough with a fifth as much sexual activity as the adolescent boy, and the frequency of outlet of the female in her twenties and early thirties is still below that of the average adolescent male. As mothers, as school teachers, and as voting citizens, women are primarily responsible for the care of these boys; and, to a large degree, they are the ones who control moral codes, schedules for sex education, campaigns for law enforcement, and programs for combating what is called juvenile delinquency. It is obviously impossible for a majority of these women to understand the problem that the boy faces in being constantly aroused and regularly involved with his normal biologic reactions.

The mean rate of outlet for the women who are young mothers and high school teachers lies between 0.7 and 2.1 per week (as indicated by preliminary calculations from our unpublished material on the female). Many of these women, including some high school biology teachers, believe that the ninth or tenth grade boy is still too young to receive any sex instruction when, in actuality, he has a higher rate of outlet and has already had a wider variety of sexual experience than most of his female teachers ever will have. Whether there should be sex instruction, and what sort of instruction it should be, are problems that lie outside the scope of an objective scientific study; but it is obvious that the development of any curriculum that faces tht fact will t e a much more complex undertaking than has been realized by those who think of the adolescent boy as a beginner, relatively inactive, and quite capable of ignoring his sexual development.

Institutional Problems. The legal approach to this problem is, as usual, even less realistic. By making illegal all pre-marital sexual activities except nocturnal emissions and solitary masturbation, English and American law forces most boys, as indicated above, into illicit activity. The chief exceptions are largely in that group that goes on to college, and which, coincidentally, accepts masturbation as a chief source of outlet. Precise incidence figures for the various types of sexual behavior which are illegal are given in later chapters of the present volume. On a specific calculation of our data, it may be stated that at least 85 per cent of the younger male population could be convicted as sex offenders if law enforcement officials were as efficient as most people expect them to be. The stray boy who is caught and brought before a court may not be different from most of his fellows, but the public, not knowing of the near universality of adolescent sexual activity, heaps the penalty for the whole group upon the shoulders of the one boy who happens to be apprehended. This situation presents a considerable dilemma for law enforcement officials and for students of the social organization as a whole.

The problem of sexual adjustment for a younger male who is confined to a mental, penal, or other sort of institution is even more difficult than the problem of the boy who lives outside in society. Administrators who have these younger males in their care are generally bewildered and at a loss to know how to handle their sexual problems. In many cases, the situation is simply tolerated or ignored, and the administrator would prefer not to be aware of the actualities. For this, many people would condemn him; but the problem in an institution for teen-age boys is far more complex than the public or the administration or scientific students have realized. It is obvious that lifetime patterns of sexual behavior are greatly affected by the experiences of adolescence, not only because they are the initial experiences, but because they occur during the age of greatest activity and during the time of the maximum physical capacity of the male. This is the period in which the boy’s abilities to make social adjustments, to develop any sort of socio-sexual contacts, and to solve the issues of a heterosexual-homosexual balance, are most involved. Since younger boys have not acquired all of the social traditions and taboos on sex, they are more impressionable, more liable to react de novo to any and every situation that they meet. If these adolescent years are spent in an institution where there is little or no opportunity for the boy to develop his individuality, where there is essentially no privacy at any time in the day, and where all his companions are other males, his sexual life is very likely to become permanently stamped with the institutional pattern. Long-time confinement for a younger male is much more significant than a similar period of confinement for an older adult.

The situation is aggravated by the more recent development of the juvenile court. Abundant as the merits of such an institution may be, there are complications involved when a court assumes control of a juvenile for a long period of years, until he is twenty or twenty-one, without, at the same time, considering the problems of sexual adjustment for its ward. The practice of the juvenile court is based on a realization that a child may need long-time training; but it ignores these other aspects of the child’s development. The juvenile court protects many a boy from the more severe sentences of the adult laws; but it sometimes holds a juvenile for several years in a correctional institution, or under probation with the court, when the crime involved would have brought only a few months’ sentence on an adult criminal charge. Adult institutions often have young inmates who have falsified their age in order to draw the lesser time of a penal commitment. The juvenile court structure is disguised by a verbiage which avoids references to “convictions,” “sentences,” “penalties,” “years to serve,” “prisons,” or “penal institutions.” But in spite of the legal fiction, the fact remains that teen-age boys may, by order of a court, be held in custody, sometimes for several years, in institutions which may be no less repressive and punitive than the average of adult prisons. It is doubtful if many of these committing judges ever consider the juvenile’s sexual adjustment when he is sent to such an institution. Within recent years there has been a movement to extend the jurisdiction of the juvenile court to persons as old as eighteen or twenty. There are commendable objectives back of such moves, but no one seems to have considered the sexual problems that will arise from the commitment of a still larger portion of the teen-age population to what are in essence long-time institutions.

The problem is not solved by the common practice of releasing juveniles from institutions on long-time parole; for the terms of the parole are, in most states, practically as strict in regard to sexual activities as the rules of the institution itself. We have numerous histories of boys who have been paroled from such institutions to elderly persons, often on farms, who have no understanding of the problems of sexual adjustment of a younger boy, who do not comprehend the significance of his socio-sexual development during that period, and who believe that such a boy should be kept from making even the simplest sort of social contacts with individuals of the opposite sex. If any large portion of the male population had been raised under such conditions, the implications of the situation would be apparent to everyone; but since the boys who get into institutions represent a small portion and a socially limited portion of the whole population, most people do not have firsthand contacts with them, and have not, therefore, considered the problem of sexual adjustment for institutionalized boys.

Boys who live in private boarding schools, and even boys who attend public or private day schools that are restricted to the single sex, face some of the same sexual problems as the boys in a penal institution.

Having reached its peak in adolescence, sexual activity in the male drops steadily from then into old age (Figures 34–37). As far as human sexuality is concerned, aging begins at least with the onset of adolescence; and if the capacity (rather than the performance) of the pre-adolescent is taken into account (Chapter 5), it seems more correct to think of aging as a process that sets in soon after the initiation of growth. The sexagenarian—or octogenarian—who suddenly becomes interested in the problems of aging is nearly a lifetime beyond the point at which he became involved in that process.

Table 45. Total sexual outlet, marital status, and age

For explanations, see the legend with Table 51 on masturbation.

It will be interesting to know how many of the other physical and physiologic functions of the human animal reach their prime before the twenties. There are a few studies of physiologic aging, and the data (just as with sexual aging) show a steady degeneration of capacities from the age of the youngest child studied. This, for instance, has been shown for such phenomena as basal heart rate, resting oxygen intake and intake during maximum work, respiratory quotient, and carbon dioxide and lactic acid relations during work (data and references in Robinson 1938). In everyday affairs, it is to be noted that armies and navies, and others who depend on manpower to accomplish work, know that the male in his late teens has physical quality, nervous coordination, and capacity for recovery that are beyond those of the even slightly older man. But research on aging has concerned itself primarily with very old individuals, and too often failed to consider such fundamentals as might be seen only in the beginnings of the processes. Aging studies need to be re-oriented around the origins of biologic decline, and that will mean around pre-adolescence or early adolescence in regard to at least some aspects of human physiology.

From the early and middle teens, the decline in sexual activity is remarkably steady, and there is no point at which old age suddenly enters the picture. The calculations become more significant when the single and married males are analyzed separately (Figures 50–52). There are no calculations in all of the material on human sexuality which give straighter slopes than the data showing the decline with age in the total outlet of the single males, or the similar curve showing the decline in outlet for the married males. Starting from a high point of 3.2 for the single males, or 4.8 for the married males, in the middle teens, the mean for both groups drops steadily to about the same point, 1.8 per week at 50 years of age, to 1.3 per week at 60 years, and to 0.9 per week at 70 years of age.

Individual males may show variations from this picture, but departures from a steady decline are exceptions in the population as a whole. There are some clinical studies (Norbury 1934, Mead and Stith 1940, Heller and Myers 1944, Bauer 1944, Werner 1945, et al.) which seem to show that some males reach a period in middle life that may be recognized as a climacteric, accompanied by an abrupt reduction in the frequency of sexual activity; but our own data show no such phenomena for the population as a whole, nor for most of the individuals in the population.

The decline in sexual activity of the older male is partly, and perhaps primarily, the result of a general decline in physical and physiologic capacity. It is undoubtedly affected also by psychologic fatigue, a loss of interest in repetition of the same sort of experience, an exhaustion of the possibilities for exploring new techniques, new types of contacts, new situations. Evidence of this is to be found in numerous cases of older males whose frequencies had dropped materially until they met new partners, adopted new sexual techniques, or embraced totally new sources of outlet. Under new situations, their rates materially rise, to drop again, however, within a few months, or in a year or two, to the old level. How much of the over-all decline in the rate for the older male is physiologic, how much is based on psychologic situations, how much is based on the reduced availability of contacts, and how much is, among educated people, dependent upon preoccupation with other social or business functions in the professionally most active period of the male’s life, it is impossible to say at the present time.

Table 46. Age and number of sources of outlet

Effect of age on the number of different kinds of sexual outlet (masturbation, dreams, intercourse, etc.) utilized in each age period. Based on the whole population involved in the study. Calculations of means for the U. S. population are based on a theoretic population with the age distribution found in the U. S. Census for 1940.

Figure 35. Number of sources of outlet in relation to age

In addition to the decrease in frequency of total outlet, there is a more or less corresponding decrease in frequency for each type of outlet (Figures 38–49, 53–88).

The number of sources contributing to the total outlet is highest in the 16–20 year period. After that, some of the sources of outlet are abandoned in some of the histories. From the teens into old age there is a steady decline in number of sources utilized (Figure 35). The mean number of sources of outlet for the older teen-age males is 2.9 (a median of 3.4), and there is a fair number of individuals (6.7%) of that age who have five or six kinds of outlet By 60 years of age, the mean number of sources has dropped to 1.6 (the median is 1.9), and none of these 60-year olds has more than four sources of outlet.

Throughout the life span, there is a steady decline in erotic responsiveness (Table 47). As measured by reactions to particular stimuli, each history in the present study has been rated on a scale which allows some comparison of persons of different degrees of responsiveness. Ratings for the entire white male population average, for instance, 16.4 at 26–30 years of age. The ratings then steadily drop, until they reach a median erotic rating of 3.6 between 66 and 70 years of age.

Frequencies of morning erection show some decline from younger to older age groups (Table 47). The frequency is probably highest in preadolescent or early adolescent boys, where we do not have sufficient data. The highest recorded median frequency is 2.05 per week between 31 and 35 years of age. By age 70 the median frequency is down to 0.50, and it drops still lower in older groups. There are a number of cases of persons who were able to record the amount of decrease in frequency of morning erections in their individual histories. There are some data that indicate that the frequency of morning erection is correlated with general physical vigor and, consequently, with frequency of sexual activity (e.g., Hamilton 1937), and that the steady decline in morning erections over the life span is therefore some measure of the decline in intensity of the sex drive in the male.

Table 47. Age affecting physiologic capacities

Data for angle of erection and for mucous secretion were coded, and calculations based on the figures so obtained.

There is evidence of greater speed in reaching full erection during earlier years, and slower erection during later years, although this has been a difficult matter on which to secure calculable data. We have already drawn attention to the high sensitivity of pre-adolescent boys (Chapter 5). Older adults are definitely slower than youths in their teens and twenties. A number of our adults were able to estimate the changes which had occurred in the course of their lives. This gradual loss in speed of erection of the male becomes evident ten or twenty years before he becomes totally impotent.

The length of time over which erection can be maintained during continuous erotic arousal and before there is an ejaculation, drops from an average of nearly an hour in the late teens and early twenties to 7 minutes in the 66–70 year old group (Table 47). Under prolonged stimulation, as in heterosexual petting or group activities or in protracted homosexual activities, many a teen-age male will maintain a continuous erection for several hours, even when the physical contacts are at a minimum and, in some cases, even after two or three ejaculations have occurred. Very few middle-aged males, and no older ones, are capable of such a performance. A considerable loss in ability to maintain an erection becomes evident some years before the onset of complete impotence.

In any age group there is considerable variation in the angle at which the erect penis is carried on the standing male. The average position, calculated from all ages, is very slightly above the horizontal, but there are approximately 15 to 20 per cent of the cases where the angle is about 45° above the horizontal, and 8 to 10 per cent of the males who carry the erect penis nearly vertically, more or less tightly against the belly. The angle of erection is, in general, higher for males in the early twenties, and lower in more advanced ages (Table 47). Average angles become definitely reduced in males past fifty. It has been difficult to secure quite dependable estimates of angles from the subjects in this study, and it is probable that the changes in medians shown in the table do not express the full extent of the change with advancing age. There are records of 106 older males who recalled a change through the years of their own histories; and these cases indicate a more considerable drop in angle, even from near the vertical to the horizontal or, at later ages, to something below a horizontal position.

With advancing age there is a steady reduction in the amount of precoital mucus which is, in a portion of the population, secreted from the urethra during sexual arousal and before ejaculation. In each age group there are about a third of the males who do not secrete such a mucus. Usually the secretion forms only a single clear drop; but for some males it amounts to several drops, or it is enough to wet the whole glans of the penis, or enough to drip. The greater abundance is found in the twenty-year old males, and there is a steady decline among the older males (Table 47). There are a few males who have been able to indicate the amount of reduction in their histories; but the record accumulated for the current ages (at time of reporting) gives a more definite picture of the decline The amount of mucus varies in any individual with the intensity of the erotic arousal, and it is probable that the lessened secretion of the older male is as much a measure of a reduction in the degree of arousal, as it may be of degenerating glands.

Table 48. Multiple orgasm and age

Capacity to have multiple orgasm in each sexual contact rapidly decreases with age the capacities of the pre-adolescent males and males in their teens being far beyond those of older adults. Table includes 380 males who regularly have multiple climax in intercourse.

The capacity to reach repeated climax in a limited period of time definitely decreases with advancing age. Occasional multiple climax occurs in most of the histories, but regular multiple climax is characteristic of only a smaller number of males. The capacity is highest among those preadolescent boys (55.5%) who have sufficient sexual contact to test their capacities (Chapter 5), but multiple climax is still frequent among males (15% to 20%) in their teens and twenties (Table 48). While a few males (perhaps 3%) retain this capacity until they are 60 or older, most men lose it by 35 or 40 years of age.

Figure 36 Capacity for multiple orgasm in relation to age

Individuals differ in the way in which they age just as they differ in their frequencies and in their choices of sexual outlet Generalizations which are based on averages of any sort must always be tempered with an understanding of the range of variation in each age group Data on means and medians must not be confused with data on particular individuals, many of whom represent wide departures from any average.

It is important to note that the range of variation in physical and behavioral characters is greatest in the youngest groups and is gradually reduced in successive periods (Table 49). This means that older populations are more homogeneous than younger groups. This is true in regard to the frequency of total sexual outlet, and in connection with most but not all of the individual sources of outlet.

Masturbation, nocturnal emissions, total pre-marital intercourse, and animal intercourse follow the general picture in having their maximum range of variation in the youngest years, and narrower ranges in the older years. On the other hand, pre-marital petting, pre-marital intercourse with prostitutes, homosexual activity, and extra-marital intercourse reach their maximum range of variation ten or more years beyond adolescence. The magnitudes of the ranges in these latter cases increase through the first age groups (in spite of reductions in sample size). The latter cases, it is to be noted, include more or less taboo activities. In these cases, the restriction of these ranges in the younger groups is probably due to the impact of the social tradition; and the achievement of maximum range and maximum mean frequency at a later period represents the gradual emancipation of the individual from the social tradition, and his final acceptance of a pattern which suits him (Chapter 21). Many of the individual histories support such an interpretation. After reaching the maximum range, each of these outlets then follows the rule in having the range of variation drop in successive age periods.

Table 49. Range of variation and age

Data based on histories of single (unmarried) males, except for marital and extra-marital intercourse. The lower limits of the ranges are 0 or near 0, and the maximum case is therefore a measure of the range of variation in each case. Differences between the least active and most active individuals in each age group decrease with advancing age, i.e., the range of varaition becomes less, the homogeneity of the population increases, with advancing age. Only the last 4 sources have the maximum cases in anything but the youngest groups.

We have the histories of 87 white males (and 39 Negro males) past 60 years of age. The number is too small to allow statistical analyses of the sort employed for the other age groups. Nevertheless, there is such interest in the sexual fate of the older male that it seems valuable to summarize the data even for these few cases.

The most important generalization to be drawn from the older groups is that they carry on directly the pattern of gradually diminishing activity which started with 16-year olds. Even in the most advanced ages, there is no sudden elimination of any large group of individuals from the picture. Each male may reach the point where he is, physically, no longer capable of sexual performance, and where he loses all interest in further activity; but the rate at which males slow up in these last decades does not exceed the rate at which they have been slowing up and dropping out in the previous age groups. This seems astounding, for it is quite contrary to general conceptions of aging processes in sex. The mean frequencies of these older white males who are still active range from 1.0 per week in the 65-year old group to 0.3 in the 75-year olds, and less than 0.1 in the 80-year old group (Table 44).

At 60 years of age, 5 per cent of these males were completely inactive sexually. By 70, nearly 30 per cent of them were inactive. From there on, the incidence curve (as far as our few cases allow us to judge) continues to drop. There is, of course, tremendous individual variation. There is the history of one 70-year old white male whose ejaculations were still averaging more than 7 per week. Among the Negro males, there was one aged 88 who was still having intercourse with his 90-year old wife, with frequencies varying from one per month to one per week. In the latter case, both of the spouses were still definitely responsive.

Heterosexual intercourse continues longer than any other outlet, but masturbation still occurs in some of the histories of men between 71 and 86 years of age, and nocturnal dreams with emission persist into the 76–80 year period. Among these cases, there is no male over 75 who has more than a single source of outlet. Erotic response at age 75 has a rating which is one-quarter of the mean rating for age 65.

Among these particular males, the mean frequency of morning erections had been 4.9 per week in the earlier years of their lives. In the 65-year period, it had dropped to 1.8, and at 75 years of age it had dropped to 0.9 per week. Morning erections usually persist for several years, even as long as five or ten years, after a male has become completely impotent in other situations.

Table 50. Age and erectile impotence

An accumulative incidence curve; based on cases which are more or less totally and, to all appearances, permanently impotent.

Figure 37. Age of onset of impotence

Percent of total population which is impotent is shown for each age.

The data on impotence will command especial interest. True ejaculatory impotence (incapacity to ejaculate even when aroused and in erection) is a very rare phenomenon (in 6 out of 4108 cases). Erectal impotence, on the other hand, is not uncommon. It appears occasionally in younger cases and is, of course, the ultimate outcome of the sexual picture in a portion of the older histories. Early erectal impotence occurs in only a few cases (0.4 per cent of the males under 25, and less than 1 per cent of the males under 35 years of age). In only a small portion of these is it a lifelong and complete incapacity. Sometimes the situation is complicated by a normal development of erotic responsiveness without an ability to perform. In some of these males, ejaculation may occur without erection as a result of the utilization of special techniques in intercourse. In many older persons, erectile impotence is, fortunately, accompanied by a decline in and usually complete cessation of erotic response.

Out of 4108 adult males on whom adequate data are available, there are 66 cases which have reached more or less permanent erectile impotence. Ruling out instances of temporary incapacity in younger individuals, the ages involved in onset of permanent impotence and the incidence data for each of the subsequent age groups are shown in Table 50 and Figure 37.

It will be seen that there are stray cases of impotence between adolescence and 35 years of age. Between 45 and 50, more males become incapacitated, and after 55 the number of cases increases rapidly. By 70 years of age, about one-quarter (27.0%) of the white males have become impotent; by 75 more than one-half (55.0%) are so; and 3 out of the 4 white males in the 80-year group are impotent. Two Negro males were still potent at 80. We have three histories of Negroes 88 years of age, and one aged 90. One of these males had been impotent for fifteen years. Two had not tried to have intercourse for some years, but morning erections made them believe they would still be potent if aroused; they were, however, no longer responding to erotic stimulation. The oldest potent male in our histories was the 88-year old Negro, who was still having regular intercourse with his 90-year old wife. Only a portion of the population ever becomes impotent before death, although most males, but not all of them, would become so if they all lived into their eighties.

A problem which deserves noting is that of the old men who are apprehended and sentenced to penal institutions as sex offenders. These men are usually charged with contributing to delinquency by fondling minor girls or boys; often they are charged with attempted rape. Among the older sex offenders who have given histories for the present study, a considerable number insist that they are impotent, and many of them give a history of long-standing impotence. A few of these men may have falsified the record, and many courts incline to the belief that all of them perjure themselves. We find, however, definite evidence in the histories that many of these men are in actuality incapable of erection. The usual professional interpretation describes these offenders as sexually thwarted, incapable of winning attention from older females, and reduced to vain attempts with children who are unable to defend themselves. An interpretation which would more nearly fit our understanding of old age would recognize the decline in erotic reaction, the loss of capacity to perform, and the reduction of the emotional life of the individual to such affectionate fondling as parents and especially grandparents are wont to bestow upon their own (and other) children. Many small girls reflect the public hysteria over the prospect of “being touched” by a strange person; and many a child, who has no idea at all of the mechanics of intercourse, interprets affection and simple caressing, from anyone except her own parents, as attempts at rape. In consequence, not a few older men serve time in penal institutions for attempting to engage in a sexual act which at their age would not interest most of them, and of which many of them are undoubtedly incapable.

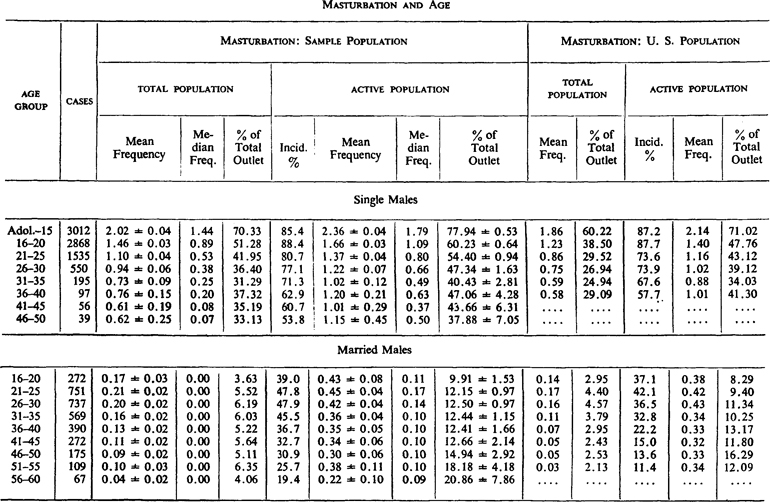

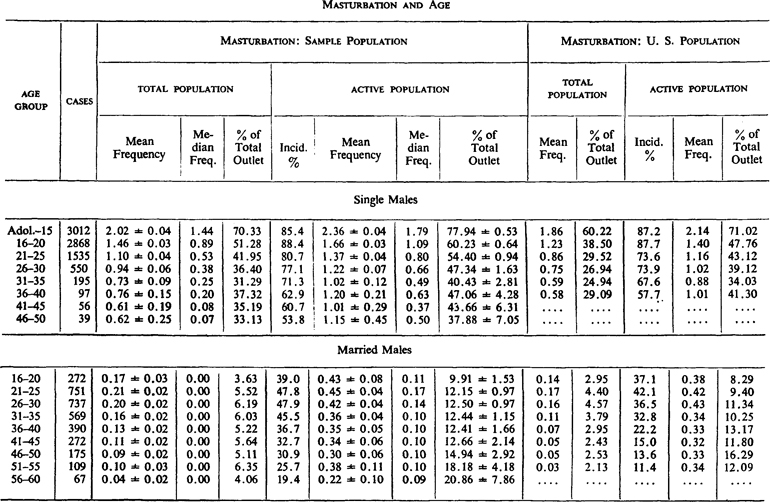

Masturbation is primarily a phenomenon of younger and unmarried groups, although it does occur in a fair number of the married histories. Later analyses will show that the incidence and frequency of masturbation are particularly affected by social backgrounds and correlated with educational levels and occupational status (Chapter 10).

The highest incidence for masturbation among single males (in the population taken as a whole) lies between 16 and 20 years of age, when 88 per cent is involved (Table 51, Figures 53–58). If the population is broken down into three groups on the basis of the amount of schooling they receive before they finally leave school (Table 82), it becomes apparent that the highest frequencies of masturbation really occur in the period between adolescence and age 15. The incidence steadily drops from that point. About half of the single population (53.8%) is still masturbating at 50 years of age. Among married males, the highest incidence (42.1%) occurs between 21 and 25 years of age, and the figures for these males similarly drop steadily into old age. In the middle fifties, hardly more than a tenth of the married males (11.4%) is involved. Masturbation is the first major source of outlet to disappear from the histories. A stray male is still involved at 75 years of age, but there is no complete masturbation to orgasm in any of the older histories.

Individuals differ tremendously in the frequencies with which they masturbate. There are boys who never masturbate. There are boys who masturbate twice or thrice in a lifetime; and there are boys and older youths who masturbate two and three times a day, averaging 20 or more per week throughout periods of some years. The population is most variable (the range of masturbatory frequencies is greatest, the differences between the least active and most active males are greatest) in the 11–15-year old group (Table 49). From this point on, the population becomes more homogeneous (there is a steady decline in range of frequencies) with advancing age. The highest rating individual at 15 years of age has a masturbatory rate which is two and a half times that of the highest rating individual at 30 years of age, and four times the rate of the highest individual at 50 years of age.

For the single population, the maximum average frequencies of masturbation are in the very youngest group (Table 51, Figures 53–58). In this group the boy who is masturbating at all ejaculates more than twice a week from this source (a mean of 2.1 and a median of 1.8 for the active population). By the middle teens the frequencies have dropped to approximately two-thirds of the figures in the younger group, and they continue to drop steadily into old age. By 50 years of age, there is about half as much masturbation among single males as in the younger adolescent boys. The decline in frequencies is dependent upon the fact that masturbation is, to a certain extent, a substitute for heterosexual or homosexual intercourse which replaces it in older groups; but it is to be emphasized that throughout the lives of many males, including married males especially of upper social levels, masturbation remains as an occasional source of outlet that is deliberately chosen for variety and for the particular sort of pleasure involved. Among the married males who do masturbate the frequencies are usually not high, averaging about once in three weeks for the active population as a whole. The frequencies are much higher for married males of upper educational levels. For the total married population, the mean frequencies are highest in the youngest age groups, dropping steadily into old age; but in the active portion of the married population, the frequencies hardly vary between 16 and 55 years of age. Here the effect of age is not in the direction of reducing rates among individuals who do masturbate, but by way of reducing the number of males who are involved.

In the youngest adolescent group, considering the population as a whole, the average boy is drawing nearly two-thirds (60.2%) of his total sexual outlet from masturbation. The figures drop steadily into old age. By 50, the average unmarried male who has any masturbation in his history derives only about a third (37.9%) of his outlet from that source. Among the married males who draw at all on this outlet, about 8 per cent of the total number of ejaculations comes from masturbation between 16 and 20 years of age; and, interesting to note, the figure rises in the later married years until it reaches 16 per cent at 50 years of age.

Table 51. Masturbation and age

In this, and in the succeeding charts in this and the following chapter, means and medians represent average frequencies per week.

“% of Total Outlet” in the TOTAL POPULATION shows what portion of the total number of orgasms is derived from masturbation in the total population. A total of such figures for all the possible sources of outlet equals 100% which is the total outlet of the group.

“% of Total Outlet” for the ACTIVE POPULATION represents the mean of the figures showing the percentage of the total outlet which is derived from this source by each individual who has any masturbation in his history, in that particular age period. The percents for the several possible outlets do not total 100% because different individuals are involved in the population utilizing each type of outlet.

U. S. population figures are corrections of the raw data for a population whose age, marital status, and educational level are the same as those shown in the U. S. Census for 1940.

Table 52. Nocturnal emissions and age

For explanations, see the legend with Table 51 on Masturbation.

Age is, obviously, a factor which affects masturbation in most of its aspects. Its influences are to be noted in the steady reductions in the numbers of persons involved (the incidences); in similar reductions in the frequencies (rates per week) with which masturbation occurs, both in the single and in the married portions of the population; in the reduction in the range of frequency. The percentage of the total outlet which is supplied by masturbation is reduced in the total population, both single and married; but among those who continue to draw on this source, masturbation remains a fairly constant portion of the outlet during the single years, even if they extend into old age. For the married males who masturbate it is an increasingly important source of orgasm with the advancing years.

Nocturnal emissions enter the picture somewhat later than other sources of sexual outlet (Table 52, Figures 59–64). In only a small number of cases do they appear at the very beginning of adolescence. Even in those cases where dreams provide the first source of ejaculation, pubic hair and other physical characteristics usually indicate that the individual became adolescent a year or more before the first emission. There are 4 cases of persons who were past 40 before they had their first nocturnal emission. Nevertheless, dreams to climax are primarily a phenomenon of the teens and the twenties.

The highest incidence of nocturnal emissions is about 71 per cent among single males 21 to 25 years of age. By 50, only about a third of the males still experience such dreams. By 60 years of age only 14 per cent still has them. It is interesting to note that dreams as an occasional source of ejaculation still appear in the histories of men as old as 86.

In the youngest age group there are a few individuals who dream to climax with average frequencies which run as high as 12 per week, although there are many males who average only a few times per year. The maximum frequencies drop rapidly in successive age groups. At 30 years of age, the maximum is only a third as high, and by 50 years of age it is only a twelfth as high, as at age 15.

Among single males of the active population, nocturnal emissions occur with the highest frequency between adolescence and 30 years of age. Among the married males the highest frequency is between 16 and 30 years of age. The highest average frequency, for those single males who have any nocturnal emissions at all, is about once in three weeks (0.3 per week); for the married males, it is once in four weeks (0.23 per week). In both groups there is a decline in frequencies after thirty. Beyond 50 years of age, nocturnal emissions do not average more than four or five per year, for those individuals who have any at all.

Table 53. Petting to climax, and age

For explanations, see the legend with Table 51 on Masturbation.

In the early twenties, the average single male (total population) derives about one-twelfth (8.3%) of his total outlet from nocturnal dreams. From there on, this outlet is of decreasing importance in the total picture. For those single males who have any dreams at all (active population), they are of greatest importance (21.5% of the total outlet) in the middle thirties. Among married males they are of lesser significance, accounting for about 3 per cent of the total ejaculations of the total population throughout the life span. They steadily rise in importance among the males in the active portion of the married population, representing 5 per cent of the outlet of the younger married males, and 10 per cent of the outlet of the older married males who ever do dream to the point of climax.

Pre-marital heterosexual histories often involve a considerable amount of physical contact without actual intercourse. About 88 per cent of the total male population has such petting experience prior to manage (Table 134, Figure 117). There are some males (and a smaller number of females) who respond to such stimulation, whether generalized or more specifically genital, to the point of complete orgasm. Such petting, as it is usually called, is not entirely new with the younger generation; but frank and frequent participation in physical stimulation that is openly intended to effect orgasm is definitely more abundant now than it was among older generations. A great deal of the petting does not proceed to orgasm, but more than a quarter of all the males (28%) pet to that point prior to marriage (Table 135, Figure 118). The incidence of the phenomenon is still higher at upper educational levels (Chapters 10 and 16) where more than half of the males (58%) are ultimately involved. The highest incidence in any single age period is 31.8 per cent during the 21 to 25-year period, and the figures drop steadily from there until the time of marriage—or until they disappear in the old age of still unmarried males.

The highest frequencies recorded for any individual male average 7.0 per week, in the 21 to 25-year group, after which the maximum cases drop quickly to 0.5 per week after 35 years of age (Table 49).

The frequencies with which males reach orgasm in pre-marital petting are relatively low, in all age groups (Table 53, Figures 38–43). This is one phenomenon where frequencies are not highest in the youngest group. Calculated in any way (as means, or medians, for the total, or for only the active portion of the population) the maximum performance is in the 21 to 25-year old group, where the mean of the active population is about once in three weeks (0.30 per week). The averages (means for the active population) then drop a bit from 26 to 40 years of age, and more abruptly thereafter.

Figures 38–40. Relation of age to frequency, incidence, and significance of petting to climax

Solid lines represent the U. S. Corrections.

Figures 41–43. Relation of age to frequency and significance of petting to climax

Solid lines represent the U. S. Corrections.

Table 54. Non-marital intercourse with companions, and age

Showing pre-marital intercourse for single males, extra-marital for married males. For the additional intercourse which those same males have with prostitutes, see Table 55. For further explanations, see the legend with Table 51 on Masturbation.

Between 21 and 25 years of age, the average male (total population) derives 3.0 per cent of his total sexual outlet from petting to climax. Leaving out the males who never do reach orgasm in petting, the statement can be made that about 6 per cent of the total outlet is so derived by the average male between 16 and 20 years of age, and this figure builds up to 17.5 per cent at 40 years of age. Since this source drops steadily in importance for the total single population, but rises in importance for individuals who are actively engaged in this activity, it is evident that the percentage of the population which is involved steadily decreases in older age groups. Petting is less important as a source of outlet than any other sexual behavior except intercourse with animals of other species. It is much more significant as a means of education toward the making of socio-sexual adjustments.

The low incidence and frequency of petting to climax in the older single groups may be correlated with the usually low rates of all sexual activities at that age, and with the fact that a large number of older, single males are apathetic, sexually inhibited, socially timid, or heterosexually disinclined. The present data, however, may be merely an expression of the fact that petting as a source of outlet has acquired vogue only in more recent decades. It is possible that some years hence those members of the present younger generation who are still unmarried may account for an increase in the frequency of this activity at older levels.

It is probable that heterosexual intercourse would provide the major source of pre-marital outlet if there were no restrictions on the activity of the younger male. There is, however, no other sort of activity that is so markedly affected by the tradition of the social level in which the individual is raised (Chapter 10). The incidence and frequencies of pre-marital intercourse are very low for the more educated portion of the population; but for lower educational levels this remains as the chief source of outlet before marriage. Data on pre-marital intercourse must, therefore, be interpreted in connection with the other factors which are treated in the present volume.

The highest incidence of pre-marital intercourse comes in the late teens, where nearly three-quarters (70.5%) of the total U. S. population is involved (Table 54, Figures 71–76). From that point the incidence drops, but still stays high. In every age group between 16 and 50, more than half (from 70.5% down to 51.3%) of the single males engage in heterosexual intercourse.

The variation in frequency of pre-marital intercourse in any group is at its maximum between adolescence and 25 years of age (Table 49). From that point, the range becomes increasingly restricted in each older population. At 15 years of age, the most active male is having pre-marital intercourse with ejaculation on an average of 25 times per week. At 30 years of age, the extreme male still has a rate of 16 per week; but by 50 years of age, the maximum frequency is down to 3.5 per week.

Table 55. Intercourse with prostitutes, and age

For explanations, see the legend with Table 51 on Masturbation.

For the total population, the highest frequency of pre-marital intercourse occurs in the 16–20 year group, where the mean is about one and a third times (1.32) per week. If the calculations are made on the active males only, the highest average frequency is in the youngest group, between adolescence and 15 years of age, where the corrected figure is almost exactly 2 per week. It again becomes evident that the youngest boy has the greatest capacity and the highest frequency of activity if he has the opportunity to exercise it. From age 16 on, the frequencies drop, and those males who are still unmarried at 50 engage in intercourse only a quarter as often (0.5 per week) as the active teen-age boys.

With advancing age, the average unmarried male draws a somewhat decreasing proportion of his total outlet from pre-marital intercourse. The average teen-age boy (of the active population) derives nearly half of all his outlet from intercourse. The average 50-year old, unmarried male derives nearer a third of his outlet from heterosexual intercourse (the data based on interpolations from the uncorrected figures in Table 54). This follows the now familiar pattern of each outlet beginning at its peak in the middle teens, and going down in rate with advancing age.

Pre-marital intercourse may be had either with companions or with professional prostitutes. Among unmarried males, an increasing portion of the intercourse is derived in later years from paid contacts (Table 55, Figures 77–82). In the adolescent to 15-year group, less than 1 per cent of the boys with pre-marital intercourse depend solely upon prostitutes, and 14.6 per cent have intercourse with both companions and prostitutes. By 50 years of age, a seventh of the males (14.3%) who have pre-marital intercourse depend entirely upon prostitutes, and more than a half of them (62.0%) have intercourse with both companions and prostitutes.

The individual males who have the highest frequencies of pre-marital intercourse with prostitutes are found in the group between 21 and 25 years of age (Table 49). In both younger and older age groups, the maximum frequencies are lower (i.e., the range of variation in those populations is less).

For this active portion of the population, the frequency of intercourse with companions is greatest between adolescence and 15, after which the frequencies drop steadily into the oldest ages; but intercourse with prostitutes increases in frequency until it reaches its maximum (over 0.6 per week) between 26 and 35 years of age. This increase in frequency is not an effect of aging, but a social effect. Younger males find it easier to secure intercourse with girls of their own age and social level. The older male finds it more convenient and less dangerous to secure intercourse from professional sources. This custom may not be followed by succeeding generations, who have been less accustomed to going to prostitutes at any age (Chapter 11).

Table 56. Marital intercourse and age

For explanations, see the legend with Table 51, on Masturbation.

For the younger males, between 16 and 20, prostitution provides only 4 per cent of the total outlet for the population as a whole, and about 11 per cent of the outlet for those who actually frequent prostitutes. But by 50 years of age, prostitutes provide nearer a sixth (approximately 16%) of the total outlet for the still single males, and more than half (about 53%) of the total outlet for the males who do go to prostitutes. Since payment for sexual contacts is much more frequent among males of particular social levels, the data need the breakdown which will be given them in subsequent chapters on social factors affecting patterns of sexual behavior.

Marital intercourse is the one activity which is least affected by any of the social factors except marital status itself. The data given here are based on males who are living with either legal or common-law wives.

Between 16 and 40 years of age, practically all of the males (more than 99%) who are married find some outlet in marital intercourse (Table 56, Figures 44–49). From 45 on, there are a few males who discontinue such intercourse even though they remain wedded and live with their wives. By 60 years of age about 6 per cent of the married males are no longer active. Our limited series of older histories shows 83 per cent of the males having intercourse with their wives at ages 60–65, and 70 per cent having it between 66 and 70. We have so few histories of still older married males that we cannot make a further statement.

In all the age groups between 16 and 30, there are individuals who have intercourse with frequencies as high as 25 or more per week (Table 49). Such high frequencies are not found in older groups. There the range of variation becomes narrower; and by 50 years of age the maximum average rate for any individual is 14 per week. By 60 the maximum has cut down to 3 per week.

It is particularly instructive to compare average frequencies in marital intercourse for successive age groups (Table 56, Figures 44–49). Between 16 and 20, the boy who is married has a higher rate of total sexual outlet (4.8 per week) than the males of any other group, and most ofthat outlet (over 85%) is derived from his marital intercourse. The frequencies of the intercourse in this teen-age group average near 4 (3.9) per week. From there on, the mean frequencies drop in each successive five-year period. The decline is at an astonishingly constant rate, from the youngest to the oldest ages. By 60 years of age, the average frequency is about once (0.9) per week.

Figures 44–46. Relation of age to marital intercourse

Solid lines represent the U. S. Corrections.

Figures 47–49. Relation of age to marital intercourse

Solid lines represent the U. S. Corrections.

Table 57. Total heterosexual intercourse and age

For explanations, see the legend with Table 51, on Masturbation.

On the other hand, the average male draws a nearly constant proportion of his total outlet throughout his life from marital intercourse. He gets from 85 to 89 per cent of his outlet from that source between 16 and 55, after which there is only a slight drop in the significance of marital intercourse. Since his rate has gone down while he continues to draw a constant portion of his total outlet from the intercourse, it is obvious that the decline in frequency of this activity must occur at precisely the same rate as the decline in the frequency of his total outlet.

Although biologic aging must be the main factor involved, it still is not clear how often the conditions of marriage itself are responsible for this decline in frequency of marital intercourse. Long-time marriage provides the maximum opportunity for repetition of a relatively uniform sort of experience. It is not surprising that there should be some loss of interest in the activity among the older males, even if there were no aging process to accelerate it.

Extra-marital intercourse, partly with companions and partly with prostitutes, occurs among 23 to 37 per cent of the males in each of the five-year periods. It is highest among the teen-age males, where 36.8 per cent of the population is involved (Table 54, 55, Figures 71–76). The accumulated number of males who have such intercourse at any time in their lives is, of course, much higher (Chapter 19). The active incidence figure stays remarkably constant between 21 and 60 years of age, with only a slight trend toward a decline in the older years. The absence of an aging effect on the incidence of the outlet is unique among all kinds of sexual activity.

The range of variation in any five-year population is greatest between 21 and 25 years of age (18 per week for the most active individuals), and the maximum goes down rapidly after that (Table 49). By 60 years of age, the most active individual has extra-marital intercourse only twice per week.

Mean frequencies for the males who are actively involved in extramarital intercourse go down more or less steadily from about 1.3 per week in the late twenties to about once in four weeks for the sixty-year olds.

The percentage of the total outlet which is derived from extra-marital intercourse is highest in the 16–20-year period (9.6 per cent of the outlet of the total population), after which there is a drop at least to age 45. Then, only about 5 per cent of the outlet of the total married population comes from this source. Considering only the males who are having some extramarital intercourse, the figures first drop and then rise—18.4 per cent of the outlet in the teen-age group, 12.3 per cent of the outlet in the 30-year group, and possibly 41 per cent of the outlet in the 60-year group comes from this intercourse with females not their wives. The rise in significance of extra-marital intercourse, both in the total population and particularly among males who are actually having such experience, is matched only by the increased significance which pre-marital intercourse plays in the lives of the older single males. Among married males, the rise in importance of extra-marital intercourse is chiefly at the expense of marital intercourse which contributes less and less to the total picture. The other outlets, masturbation, nocturnal dreams, and the homosexual, are not so modified by the extra-marital intercourse.

From about 7.5 per cent to 14.5 per cent of the extra-marital intercourse is had with prostitutes (Table 55, Figures 77–82). The figures on the available histories fluctate from group to group, without a discernible aging effect, at least up to age 60. The percentage of married males involved with prostitutes drops steadily from 19.5 per cent among the young 20-year olds, to 7.9 per cent at age 50. The frequencies among the active males stay quite constant (between 0.18 and 0.27) at all ages, without any definite trend. For males who have any extra-marital intercourse with prostitutes, the contacts account for about 3.6 per cent of the total sexual outlet at earlier ages. The significance of such intercourse increases with advancing age among these males who are actively involved. It finally approaches a figure which is nearly a fifth (18.4%) of the total outlet of these males in their fifties. This increase in percent of total outlet derived from extramarital intercourse with prostitutes is in striking contrast with the lowered incidences, frequencies, and significances, with advancing age, of most other types of sexual activity. The meaning of this will be discussed in Chapter 20.

The individuals who have extra-marital intercourse with prostitutes most frequently are in the youngest age group, 16 to 20 years of age; but since the percentage of the total sexual outlet which is drawn from that source is lowest in the youngest group, and rises gradually to 50 years of age, it is apparent that prostitutes are important in replacing other sources of outlet among older males.

Homosexual activity in the human male is much more frequent than is ordinarily realized (Chapter 21). In the youngest unmarried group, more than a quarter (27.3%) of the males have some homosexual activity to the point of orgasm (Table 58, Figures 83–88). The incidence among these single males rises in successive age groups until it reaches a maximum of 38.7 per cent between 36 and 40 years of age.

High frequencies do not occur as often in the homosexual as they do in some other kinds of sexual activity (Table 49). Populations are more homogeneous in regard to this outlet. This may reflect the difficulties involved in having frequent and regular relations in a socially taboo activity. Nevertheless, there are a few of the younger adolescent males who have homosexual frequencies of 7 or more per week, and between 26 and 30 the maximum frequencies run to 15 per week. By 50 years of age the most active individual is averaging only 5.0 per week.

Table 59. Animal contacts and age

For explanations, see the legend with Table 51 on Masturbation.

For single, active populations, the mean frequencies of homosexual contacts (Table 58, Figures 83–88) rise more or less steadily from near once per week (0.8 per week) for the younger adolescent boys to nearly twice as often (1.7 per week) for males between the ages of 31 and 35. They stand above once a week through age 50.

In the population as a whole, among boys in their teens, about 8 per cent of the total sexual outlet is derived from the homosexual. Calculating only for the single males who are actually participating, the average active male in his teens gets about 18 per cent of his outlet from that source, and the figure is increasingly higher until, at 50 years of age, the average male who is still single and actively involved gets 54 per cent of his outlet from the homosexual. This, and pre-marital intercourse with prostitutes, are the only sources of outlet which become an increasing part of the sexual activity of single males. For most other kinds of outlet, as we have shown, the figures drop with advancing age. Since there is a steady decline in frequency of total sexual outlet for the average male, and since there is an increase both in frequencies and in percentage of total outlet derived from the homosexual, it is obvious that this outlet acquires a definitely greater significance, and a very real significance, in the lives of most unmarried males who have anything at all to do with it. There is considerable conflict among younger males over participation in such socially taboo activity, and there is evidence that a much higher percentage of younger males is attracted and aroused than ever engages in overt homosexual activities to the point of orgasm. Gradually, over a period of years, many males who are aroused by homosexual situations become more frank in their acceptance and more direct in their pursuit of complete relations (Chapter 21), although some of them are still much restrained by fear of blackmail.

Homosexual contact as an extra-marital activity is recorded by about 10 per cent of the teen-age and young 20-year old married males. By 50 years of age, it is admitted by only 1 per cent of the still married males, but this latter figure is undoubtedly below the fact. Average frequencies fluctuate between once a week to once in two or three weeks for the married males who have any such contacts; and there is no distinct age trend. From 4 to 9 per cent of the total outlet of these married males is drawn from the homosexual source, but again there is no apparent age trend.

Contacts between the human and animals of other species are largely confined to the rural portions of the male population. Rural-urban backgrounds are, consequently, the most important factors in determining the incidence and frequency of this sort of outlet. Animal contacts include the usual type of heterosexual intercourse and also anal and oral techniques which provide orgasm for the human males. The present calculations include all three types of relations.

There are some data which indicate that the frequency of animal contacts varies tremendously in different parts of the United States. The figures given here apply primarily to the northeastern quarter of the country.

About 6 per cent of the total male population is involved in animal contacts during early adolescence (Table 59). This is the highest incidence figure at any age. The figure drops to about 1 per cent in the single population over 20 years of age. If only the unmarried rural population is considered, the incidence figures range from 11 per cent at 11–15 years of age to 4 per cent at 25 years of age. Differences in social level affect this activity, and the figures need further analyses on that basis (Table 124).

The maximum frequencies in animal intercourse (for the most active individual) go up to 8.0 per week for the population between adolescence and 15 years of age (Table 49). The most active cases in the next age group drop to 4.0 per week, and to 0.1 per week by 30 years of age.

Animal intercourse has the lowest frequencies of all the sources that contribute to sexual outlet. For the total population (including persons who never engage in the activity) the average never rises above once or twice in a year; but for those who actually utilize this source of outlet, the frequency is about twice in three weeks (0.69 per week) in the late teens. There are too few active cases to generalize for older groups. The average boy who is having animal intercourse draws 7 per cent of his total outlet from that source in his early teens, and nearly 15 per cent of his outlet from that source between ages 21 and 25. There are cases of animal intercourse that extend with some frequency into the fifties, and in one case past 80 years of age. In general, the picture is one of decreasing incidence, decreasing frequency, and decreasing significance in the later years; but the cases are so few and the rural-urban factors are so significant, that these data are not readily interpreted without further breakdown.

Among the males who have been married, but whose marriages have been terminated by death, separation, or divorce, there is sexual activity which in frequency is considerably above that of the single male, and nearly as high as among the married males. The effects of aging are, of course, apparent in this group. The detailed record is given in Chapter 8 on Marital Status and Sexual Outlet.