In the history of most human cultures, extra-marital intercourse has more often been a matter for regulation than has intercourse before marriage. Frequently this has taken the form of denying the married female intercourse with anyone except her husband; less often it has included a restriction of the male’s right to have intercourse outside of his home. While various issues have been involved, such regulations have been particularly concerned with the property rights which the male has had in his wife, and there is no question that the extra-marital activities of the female became objects of concern in such early codes as the Babylonian (Harper 1904), Hittite (Barton 1925), Assyrian (Barton 1925), Jewish (Bible, Talmud), and others, because of these property rights, rather than because moral issues were recognized.

In so-called primitive groups in various parts of the world today much the same distinctions are made between intercourse before and after marriage, and between the male’s right and the female’s right to have such relations (Malinowski 1929, Hartland 1931, Thurnwald 1931, Wissler 1922, Fortune 1932, Murdock 1934, Blackwood 1935, Linton 1936, Lips 1938, Reichard 1938, Mead 1939, Schapera 1941, Chappie and Coon 1942, Bryk 1944, Ford 1945). Similar distinctions have been made throughout the history of Western European civilization, and the rights of the male in the female who is married to him have been a basic part of English and American law. It is only within the last few decades that material changes have been effected in this country in legal viewpoints on the relationship of the husband and wife.

In line with these ancient distinctions, there are still various segments of our population in this country today which more or less freely accept premarital relations, while objecting strenuously to extra-marital intercourse. In fact it may be said that there is no segment of our American population which, as a whole, really accepts extra-marital activities in anything like the way that masturbation is accepted at upper social levels, or in the way that pre-marital intercourse is accepted at lower social levels. In some segments of the population, relatively little attention is paid to the pre-marital intercourse which occurs among young people; but at all social levels, extra-marital intercourse is a subject for gossip—often malicious gossip—often for peremptory and outraged community reaction, and quite often for legal penalties. The offended spouse who takes the law into his or her own hands, and assaults and even murders the competitor in the sexual relation, is, in many parts of the country today, likely to be backed by a certain amount of public sympathy. Juries are loath to convict in such cases. It does not alter the fact that society knows that extra-marital intercourse does occur, and that it occurs with some frequency; and it seems not to matter that it is generally known that such intercourse usually goes unpunished. Society is still outraged when confronted with the specific case on which it is challenged to pass judgment.

These social attitudes are particularly interesting in view of the fact that a considerable proportion of those who react most violently against the known instances of extra-marital relations, may have similar experience in their own histories. Nearly three-quarters (72%) of the males in the Terman study (Terman 1938) admitted that they wished on occasion to have extramarital intercourse, and a similarly high proportion of the males in our present study have expressed the same desire. Furthermore, many of them actually have such extra-marital relations. The pretense that these persons make in defending the codes clearly indicates a conflict in their own minds concerning the social significance of such relations. If our society is ever to act more intelligently on these matters, it will need more factual data. Even the scant data that we can offer here may prove of some significance.

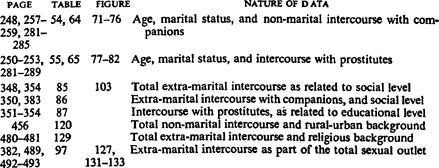

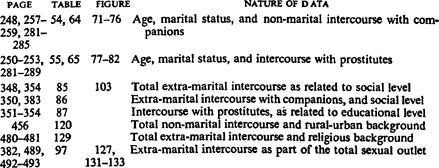

Specific material on the occurrence of extra-marital intercourse in various age groups and in various social divisions of the population, has already been given in tables and charts, and in earlier discussions in the present volume, as follows:

We have found a great many persons who would like to know how many males have extra-marital intercourse. Obviously this considerable interest depends upon the fact that most of the married males who ask the question have already had such experience, or would like to have it if they could reconcile it with their consciences and if it could be managed without involving them in legal difficulties or public scandal.

At the same time, this considerable interest also indicates that many individuals fear that their extra-marital histories may become known. In consequence, it has been peculiarly difficult, in the present study, to secure anything like adequate data on this aspect of human sexual activity. There is probably nothing in the histories of older married males who belong to better educational and social levels that has more often been responsible for their refusal to contribute to the present research. Many of the persons who have contributed only after some months or years of refusal to do so, prove to have nothing in their histories that would explain their original hesitancy except their extra-marital intercourse. Even those who have contributed more readily have probably covered up on this more often than on any other single item. We have reason for believing that most of the persons who have criticized the adequacy of the present study, on the ground that they were able to go through a history “without telling everything,” were individuals who failed to record their own extra-marital experience. Considering that the legal penalties for such sexual activity are rarely enforced, and that most males feel that such activity is highly desirable and not exactly wrong, it is particularly interesting to observe this considerable disturbance over the issue. Only the fear of the social (as opposed to the legal) consequences can explain this reticence about extramarital sexual performance.

It has so far been impossible to secure hundred percent samples from men of the type that belongs to business organizations, business executive groups, and service clubs; and we have every reason for believing that extra-marital intercourse is the source of the hesitance of many of the individuals in such groups to cooperate. Consequently, the incidence and frequency figures which are given here must represent the absolute minimum, and it is not at all improbable that the actuality may lie 10 to 20 per cent above the figures now given.

Hamilton (1929) found 28 per cent of his hundred men with records of extra-marital intercourse. His figure would have been higher if he had dealt with older men. In the present study, something over a third (27% to 37%) of the married males in each of the five-year age periods have admitted some experience in extra-marital intercourse (Table 64, Figure 73). Since these are active incidence data, the accumulative figure must amount to something more than that. Because of the inadequacy of the record it has been impossible to construct accumulative incidence curves by the usual techniques (Chapter 3), and we can only estimate from these active incidence figures.

On the basis of these active data, and allowing for the cover-up that has been involved, it is probably safe to suggest that about half of all the married males have intercourse with women other than their wives, at some time while they are married.

About 40 per cent of the high school and college males have admitted extra-marital relations (Tables 85, 86). For the grade school group, a higher percentage of the younger males have given such records, but only a smaller percentage (19%) of the older males. There are several possible explanations of this discrepancy, but there is so much likelihood of cover-up here that the question cannot be resolved at this time.

The most striking thing about the occurrence of extra-marital intercourse is the fact that the highest incidences for the lower social levels occur at the younger ages, and that the number of persons involved steadily decreases with advancing age (Table 85). Lower level males who were married in the late teens have given a record of extra-marital intercourse in 45 per cent of the cases, whereas not more than 27 per cent is actively involved by age 40 and not more than 19 per cent by age 50. In striking contrast, the lowest incidences of extra-marital intercourse among males of the college level are to be found in the youngest age groups, where not more than 15 to 20 per cent is involved, and the incidence increases steadily until about 27 per cent is having extra-marital relations by age 50.

Similarly, the highest frequencies of extra-marital intercourse are to be found among the younger males of the lower educational levels, but the frequencies drop steadily with advancing age (Tables 85, 97). Between 16 and 20, males of the lower educational level who are actually involved in extra-marital intercourse average such contacts more than once (1.2) per week; but by age 55 the frequencies have dropped to hardly more than once in two weeks (0.6 per week). On the other hand, college males of the active population begin with frequencies of a little more than once in two or three weeks between the ages of 16 and 30, but finally arrive at frequencies that are nearer once a week by the time they are 50.

We have previously suggested (Chapters 10, 18) possible explanations for these diverse patterns in the extra-marital intercourse of different social levels, of which explanations the most likely is the fact that lower level males have an abundance of pre-marital intercourse, and there is some carry-over of that type of promiscuity after marriage. On the other hand, upper level individuals are the ones with the most restrained pre-marital histories, and they lose that restraint only gradually and do not so often embark on extra-marital relations until later years. We cannot explain why there should be a cessation of extra-marital activity among so many older males of the lower level. It cannot be entirely due to their generally poorer physical condition at older ages, for it is the percent of their total outlet from extra-marital relations which has dropped, from an original of 12 per cent to 6 per cent. Meanwhile, among males of the college level, the percent of the total outlet which is derived from extra-marital intercourse has increased from an original 3 per cent in the earlier years to 14 per cent by age 50 (Table 97).

Between 16 and 20, married males of the grade school level have 10.6 times as much extra-marital intercourse as males of the college level. To make another comparison, married males of occupational classes 2 and 3 (the laborers and semi-skilled workmen) have 16.7 times as much extramarital intercourse during their late teens as males of occupational class 7 (the future professional group).

For most males, at every social level, extra-marital intercourse is usually sporadic, occurring on an occasion or two with this female, a few times with the next partner, not happening again for some months or a year or two, but then occurring several times or every night for a week or even for a month or more, after which that particular affair is abruptly stopped. The averaged data may show mean frequencies of once a week or two, but the whole of the year’s total is likely to have been accumulated on a single trip or in a few weeks of the summer vacation. There are extreme instances of younger males whose orgasms, achieved in extra-marital relations, have averaged as many as eighteen per week for periods of as long as five years; but these are unusual cases. Lower level males are the ones who are most likely to have more regularly distributed experience, often with some variety of females. Among males of the college level extra-marital relations are almost always infrequent, often with not more than one or two or a very few partners in all of their lives, and usually with a single partner over a period of some time—in some cases for a number of years.

Extra-marital intercourse occasionally accounts for a fair portion of the outlet of the married males of certain segments of the population. It accounts for 11 per cent of the outlet of married males of the grade school level during their late teens (Table 86). But more often it is a smaller part of the total picture. It ultimately accounts for something between 5 and 10 per cent of the total orgasms of all the married males in the population (Table 64).

Prostitutes supply something between 8 and 15 per cent of all extramarital intercourse (Chapter 20). Obviously, most of the extra-marital activities are had with companions. For lower level males, these may be semiprofessional pick-ups, but are often married women of their own class. For the upper level males, the contacts may be had with females of any social level, but many of them are had with their own social level.

Extra-marital intercourse occurs most frequently among males who live in cities or towns; less frequently in rural populations (Table 120). At the grade school level, the number of urban males involved may be 20 to 60 per cent higher than the number of rural males who are having extra-marital experience, and the frequencies in this lower educational level are higher among urban males, especially in the early twenties. Among the college-bred males, the city-raised individuals are involved two or three times as often as the rural males, but the frequencies seem to be higher in the rural group.

To judge from those few groups on which religious data are available (Table 129), extra-marital intercourse seems to occur much more frequently among those who are less actively concerned with the church, and much less frequently among males who are devoutly religious. The differences between devout and inactive members of any religious group are, however, nowhere near so great as the differences between social levels. The community acceptance or non-acceptance of extra-marital intercourse is much more effective than the immediate restraints provided by the present-day religious organization. But since the sex mores originated in religious codes (Chapter 13), it is, in the last analysis, the church which is the origin of the restrictions on extra-marital intercourse.

There seems to be no question but that the human male would be promiscuous in his choice of sexual partners throughout the whole of his life if there were no social restrictions. This is the history of his anthropoid ancestors, and this is the history of unrestrained human males everywhere. The human male almost invariably becomes promiscuous as soon as he becomes involved in sexual relations that are outside of the law. This is true to a degree in pre-marital and in extra-marital intercourse, and it is true of those who are most involved in homosexual activities.

The human female is much less interested in a variety of partners. This is true in her pre-marital and extra-marital histories and, again, it is strikingly true in her homosexual relations. The easy explanation that the female is basically more moral, and the male less moral, does not suffice. These differences must be more dependent upon differences in the sexual responsiveness of males and females, and particularly upon differences in the conditionability of the two sexes. The average female is not aroused by nearly so many stimuli as is the male, and finds much less sexual excitement in psychic associations or in any sensory stimulations outside of the purely tactile. These differences are similar to those found between males and females in the lower mammals, and there is a good deal of evidence (Beach 1947) that they depend upon differences in the nervous organization on which sexual behavior depends.

In practical terms this means that there are a great many human females who find it incomprehensible that so many human males should look for sexual relations with women other than their wives. On the other hand, most males see some force to the argument that variety is attractive in any sort of situation, whether it concerns the literature that one reads, the music that one hears, the recreation in which one engages, the food which one eats, the type of sex relations which one has, or the sexual partners with whom the relations are had. This philosophy has been frankly expressed by a considerable number of males who have contributed histories to the present study, even though some of them immediately add that for moral and social reasons they have not had extra-marital intercourse and will not have extra-marital intercourse, however much they may desire it.

There is, of course, a smaller portion of the females, the number of whom we have not yet calculated, who find variety in sexual relations as interesting as any of the males find it.

Extra-marital intercourse, then, may occur irrespective of the availability or frequency of other sorts of sexual outlet, and without respect to the satisfactory or unsatisfactory nature of the sexual relations at home. Most of the male’s extra-marital activity is undoubtedly a product of his interest in a variety of experience. On the other hand, there is certainly a portion of his extra-marital intercourse which is the product of unsatisfactory relations with his wife. When she fails to be interested in sexual relations with her husband, when she is less interested than he is, when she refuses to have intercourse as frequently as he would like it, when she refuses to allow the variety in pre-coital techniques that the male would like to have, or when she accedes to such techniques without evidencing an interest equal to that of the male, she is encouraging him to find extra-marital relations. The wife’s refusal of mouth-genital contacts (Chapter 18) with her husband is a factor in sending some males elsewhere for such experience.

All of these same factors may, of course, operate to lead a sexually responsive wife into extra-marital intercourse; but that is not so often true as is the reverse situation.

It is not yet clear how much relation there is between experience in premarital intercourse and experience in extra-marital intercourse. Exact correlations will have to be published later. Certainly there are histories of males who had an abundance of pre-marital intercourse and who never have any sort of extra-marital intercourse; and there are histories of males who had no pre-marital intercourse but who begin a considerable amount of extra-marital intercourse as soon as they are married. There are histories of males who are examples of every other type of relationship between these two phenomena. A multiplicity of factors must be involved, and it will take careful analyses to identify what correlations may exist.

It is true, as just noted, that males of the lower educational levels are the ones who have the most pre-marital intercourse, and they are the ones who have the most extra-marital intercourse in early marriage. And it is also true that the college level males have the least pre-marital intercourse, and the least extra-marital intercourse in early marriage. But the correlations lie in the basic attitudes of the social groups which are involved, and they are not a direct effect of pre-marital behavior on extra-marital patterns.

Throughout the literature of the world, extra-marital intercourse has provided an overwhelming abundance of material for biography, drama, fiction, and serious essay. There is probably no sexual theme that has appeared more often in the world’s literature, both great and small, in all ages and among all nations. Most often the relationships have been portrayed as highly desirable, intrinsically sinful, certain of obstruction by a conspiracy of social forces, and doomed to tragic failure which becomes most tragic when it appears that the illicit relations would have been the higher destiny if social conventions had not interfered. That extra-marital relations are generally desired has, evidently, been known to all men throughout the ages. That they seldom work out in society as it is constructed has been at least believed by the writers of all ages.

Current sociologic, clinical, sex educational, and religious literature repeats, for the most part, this conviction that extra-marital intercourse always does damage to marriages (e.g., Armitage 1913, Forel 1922, Meyer 1927, Eddy 1928, Hamilton 1929, Lindsey and Evans 1929, Amer. Soc. Hyg. Assoc. 1930, Rice 1933, 1946, Ruland and Rattler 1934, Robinson 1936, Ellis 1936, Clark 1937, Benjamin 1939, Popenoe 1943, Rockwood and Ford 1945, Seward 1946). In this literature, the judgment against extramarital intercourse is almost uniform. Only an occasional writer suggests that there may be values in such experience which can be utilized for human needs.

The public record is replete with instances of marital infidelities which have wrecked homes and destroyed individuals. The counselor and clinician see a stream of cases in which marital difficulties turn around the extra-marital activities of the husband or of the wife. The scientist can add little that is new in the record of such cases, and he cannot minimize their significance in our social organization.

There is, nevertheless, room for a scientific examination of the real bases of the difficulties that develop out of extra-marital sexual relations. Is it inevitable that extra-marital intercourse should lead to difficulties, or do the difficulties originate in the mores of the group? What proportion of all extra-marital relations lead to marital disturbances? The publicly known clinical cases may, like clinical cases of other sorts, represent only the disturbed segment of the group that has extra-marital experience, and may not adequately represent the situation as a whole. Do extra-marital relations ever contribute to the effectiveness of a marriage? What effect does such activity ultimately have upon the personalities of those who are involved? Certainly society may be concerned with securing objective answers to these questions.

In gathering the thousands of married histories which have entered into the present study, we have begun the accumulation of a considerable body of material on the factors that contribute to marital stability and, conversely, to marital discord. With the further continuation of this study, analyses of these data will be undertaken in a later publication. For the present, only fragments can be offered that bear on the social significance of extra-marital intercourse.

Certainly many different sorts of situations are involved. There are many factors that may affect the outcome of the extra-marital activities, and the record is much more diverse than has generally been believed.

At lower social levels, where the most extra-marital intercourse occurs, wives rather generally expect their husbands to “step out,” and some of them rather frankly admit that they do not object provided they do not learn of the specific affairs which are carried on. Nevertheless, extramarital intercourse is the sexual factor which is most often involved in marital discord at that level. Diversion of the interest and affection of the spouse who has the extra-marital relation results in jealousy and bitter hatreds, and these lead to endless quarrels and vicious fighting with, occasionally, murder as the outcome. A portion of the non-support which is so common at this level is the result of the male’s distraction by females other than his wife. Desertions, separations, and divorce, in this group, are frequently the outcome of these extra-marital attractions.

Nevertheless, a portion of the extra-marital intercourse at lower levels is had without apparent interference with the affection between the spouses, or with the stability of the marriage. The data are as yet insufficient to warrant a statistical measure of the frequency of each type of situation.

Extra-marital intercourse is less often accepted in middle class groups. While it may not involve as much quarreling and fighting, it often leads to divorce. How often it occurs without causing trouble is a matter that still needs to be determined.

The extra-marital intercourse of the upper social level much less often causes difficulty, because it is usually unknown to anyone except the two persons immediately involved. On occasion it does become known and causes marital discord and divorce. On the other hand, it is sometimes had with the knowledge of the other spouse who may even aid and encourage the arrangement. Such a frank and open acceptance of the partner’s non-marital sexual relations is practically unknown at lower social levels, and at all levels is a source of astonishment to persons with strict moral codes.

Wives, at every social level, more often accept the non-marital activities of their husbands. Husbands are much less inclined to accept the non-marital activities of their wives. It has been so since the dawn of history. The biology and psychology of this difference need more careful analysis than the available data yet afford.

The significance of extra-marital intercourse may more often depend upon the attitudes of the spouses and of the social groups to which they belong, than upon the effect of the actual intercourse upon the participating individuals. Few difficulties develop out of extra-marital intercourse when the relationships are unknown to anyone but the two persons having the intercourse. There are histories of long-continued extra-marital relationships which seem to have interfered in no way with the marriages, until the other partner or partners discovered the infidelity. Then they immediately filed suit for divorce.

Extra-marital intercourse most often causes difficulty when it involves emotional and affectional relations with the new partner who takes precedence over the spouse. Conversely, the extra-marital contacts most often avoid trouble when they are social affairs without too much emotional content. There are a few males who can carry on emotional relationships with two or more partners simultaneously, but there are many more who do not succeed at such an arrangement.

There are some individuals among our histories whose sexual adjustments in marriage have undoubtedly been helped by extra-marital experience. Sometimes this depends upon their learning new techniques or acquiring new attitudes which reduce inhibitions in their marital relations. Some women who have had difficulty in reaching orgasm with their husbands, find the novelty of the situation with another male stimulating them to their first orgasm; and with this as a background they make better adjustments with their husbands. Extra-marital intercourse has-had the effect of convincing some males that the relationships with their wives were more satisfactory than they had realized.

There are a few cases of married couples who have ceased sexual relations with each other, but who maintain happy and socially successful homes while each of the partners finds the whole of his or her sexual outlet outside of marriage. There are cases of males who are totally impotent with their wives, although they are successful in extra-marital relations which they may carry on throughout the whole of their marital histories, while the wives similarly maintain lifelong relations with men other than their husbands.

In both lower and upper level histories, there are cases where the children in the home are the offspring of the extra-marital relationships. Both spouses may accept the situation, and it may cause no difficulty as long as the neighbors and the law are unaware of the fact.

The histories of persons born and raised in Continental Europe usually involve a great deal of extra-marital intercourse, and such histories should be carefully studied in any scientific analysis of the outcome of such relations.

By and large, it is not a large proportion of the population that accepts an unlimited amount of extra-marital intercourse. Even those individuals who publicly defend the desirability of such relationships usually have notably few experiences in their actual histories. Whether this is a tribute to the effectiveness of the mores in controlling the behavior of persons who think that they are emancipated, or whether it is evidence that extra-marital intercourse entails difficulties that they did not anticipate, or whether it merely indicates that successful extra-marital relations are carried on with difficulty under our present social organization, it is impossible to say at this time. Certainly the psychologist and social scientist, and society in general, need a great many more specific data before there can be any final evaluation of the effects of extra-marital intercourse on individuals and on their relations to their homes and to the society of which they are a part.