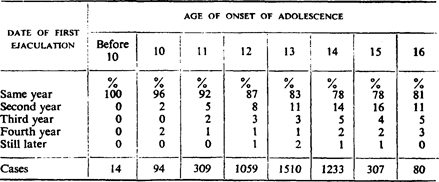

Table 67. Lapse between onset of adolescence and first ejaculation

For many centuries, men have wanted to know whether early involvement in sexual activity, or high frequencies of early activity, would reduce one’s capacities in later life. It has been suggested that the duration of one’s sexual life is definitely limited, and that ultimate high capacity and long-lived performance depend upon the conservation of one’s sexual powers in earlier years. The individual’s ability to function sexually has been conceived as a finite quantity which is fairly limited and ultimately exhaustible. One can use up those capacities by frequent activity in his youth, or preserve his wealth for the fulfillment of the later obligations and privileges of marriage.

Medical practitioners have sometimes ascribed infertility to wastage of sperm. Erectal impotence is supposed to be the penalty for excessive sexual exercise in youth (e.g., as in Vecki 1901, 1920; Liederman 1926, Efferz in Bilderlexikon 1930 (3):118, Robinson 1933, pp. 61, 135, 142, et al., Rice 1946). The discovery of the hormones has provided ammunition for these ideas, and millions of youths have been told that in order “to be prepared” one must conserve one’s virility by avoiding any wastage of vital fluids in boyhood (Boy Scout Manual, all editions, 1911-1945; W. S. Hall 1909; Dickerson 1930:109ff; 1933:15ff; U. S. Publ. Health Serv. 1937). Through all of this literature, an amazing assemblage of errors of anatomy, physiology, and endocrinology has been worked together for the good of the conservationist’s theories. Why the ejaculation of prostatic and vesicular secretions should involve a greater wastage of gonadal hormones than the outpouring of secretions from any of the other glands—than the spitting out, for instance, of salivary secretions—is something that biologists would need to have explained. The authors of various popular manuals, however, seem able to explain it “so youth may know,” and conserve their glandular secretions.

The Greek writers Empedocles and Diocles, and others including Plato after them, are said (Allbutt 1921, May 1931) to have believed that semen came from the brain and spinal marrow and that excessive copulation would, in consequence, injure the senses and the spine. Today, it is not unusual to find exactly the same superstitions about the origin of semen, and the consequently debilitating effects of ejaculation, among adolescent boys and among certain of their elders who want to believe such things. Many teen-age boys, on the contrary, have held to the equally unproved opinions that the exercise of one’s sexual functions, either in masturbation or in intercourse, may develop genital size and increase one’s erectal capacity, and that abstinence for any long period of time may impair one’s capacities for subsequent performance.

There have been few scientific data available to answer these questions, but that has not interfered with their being answered. It not infrequently happens that the volume of discussion on a subject bears an inverse relation to the amount of exact information which is available. The assurance with which generalizations and conclusions are drawn, may reach its maximum when the least effort has been made to investigate the data which are basic to an understanding of the situation. If, as in the present instance, a whole system of moral philosophy is involved, the conclusions become foregone and by dint of much repetition assume the status of axioms which are accepted by laymen and scientists alike. But this is a question of the physical and physiologic outcome of physical and physiologic activities, and as such it is a question which can be investigated only by scientific procedures.

Table 67. Lapse between onset of adolescence and first ejaculation

Early in the course of the present study, Dr. Glenn V. Ramsey, while securing the histories of younger boys, noted differences in their then current sexual frequencies which seemed to be correlated with the degree of maturity of each boy. Following that lead, we have subsequently examined the histories of the whole population involved in the present study, and find that there is, in actuality, a relationship between the age at onset of adolescence, the age of first sexual performance, the frequencies of early sexual activity, the frequencies of sexual activity throughout most of the life span of the individual, and the sources on which he depends for his sexual outlet. While chronologic age is of prime importance in determining the mean frequencies of sexual activity for populations in different age groups (Chapter 7), the biologic factors which account for variation in the age of onset of adolescence seem to be of definite importance in effecting variation within any single group. The data which substantiate these generalizations should provide one more instance of the difference between a priori reasoning and conclusions based on statistically accumulated fact.

Any consideration of the age of onset of adolescence is made difficult by the fact that there is no single criterion by which that age can be recognized. In Chapter 5, in presenting the statistical data on adolescent developments, it was pointed out that there are a good many physical characters involved, and that they do not all appear and develop at exactly the same time. In the same chapter, it was pointed out that the designation of a particular year, in any individual’s history, as the age of onset of adolescence, must, therefore, depend upon judgments which may sometimes be arbitrary and not exactly in accord with all of the details of the fact.

In the present study, the time of onset of adolescence has been fixed as the date of the first ejaculation, unless there has been evidence that ejaculation would have been possible at an earlier age if the individual had been stimulated to the point of orgasm. When the year of first ejaculation coincides with the year in which the first pubic hair appears, and with the time of onset of rapid growth in height, and/or with certain other developments, there is no question that that year may be accepted as the first year of adolescence. Eighty-five per cent of all male histories fall into this category. On the other hand, if the first ejaculation follows these other events by a year or more, and if it is clear that there was no test of the individual’s sexual capacity prior to the first ejaculation, and if there seems to be no question of the reliability of the memory in regard to the dates of the other adolescent developments, then the age of onset of adolescence is better established by events other than ejaculation. Where first ejaculation occurs as a nocturnal emission, it usually (though not always) does not come until a year or more after the appearance of the other adolescent developments, and the onset of adolescence should be set a year or more before the first ejaculation.

To define the time of onset of adolescence by any single criterion does not satisfy the reality as well as a judgment based on all of the pertinent data. Even hormones and the 17-ketosteroids cannot be accepted as the sole criteria for determining this event, or any other event. The history of systematic botany and systematic zoology is replete with attempts to discover significant and diagnostic characters which might provide clear-cut and absolute bases for systems of classification; but the modern taxonomist finds that the use of a single character inevitably provides a classificatory system which is artificial and, at least at certain points, in direct conflict with data from other sources. Every aspect of a situation is part of the reality which one must take into account, if one is to understand that reality. In the present instance, the onset of adolescence must be recognized whenever there is any development of any physiologic or physical character that pertains to adolescence. The ages of onset of adolescence used for statistical analyses in the present chapter, and throughout this whole volume, are based upon this use of the multiple characters which are concerned.

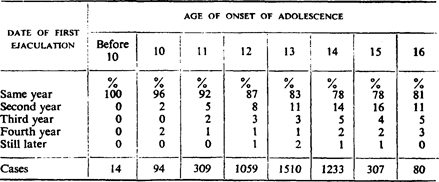

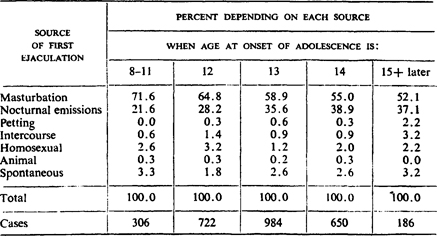

Table 68. Sources of first ejaculation in relation to age at onset of adolescence

Figure 89. Sources of first ejaculation in relation to age at onset of adolescence

The use of multiple characters in a taxonomic classification inevitably calls for a certain exercise of subjective judgment, and this is the most serious objection to such a procedure; but the errors introduced by judgment are not likely to be as misleading as the artificialities introduced by the use of a single set of criteria in a classification.

In this study, the determination of the age of onset of adolescence has been further complicated by the necessity for depending on the subject’s memory for a report of what is supposed to have happened. Considering the indefinite nature of the event itself, and this difficulty of obtaining accurate records by way of memory (Chapter 4), it is surprising that it has been possible to demonstrate correlations between this phenomenon and any aspects of sexual behavior.

It will be recalled that the average age of onset of adolescence for the white male population has been calculated as 13 years and 7 months (Chapter 5). There are very few boys who reach adolescence prior to age 10, and few even before age 11. Consequently, in most of the tables accompanying the present chapter, the males who were adolescent prior to age 11 have, for purposes of calculation, been included in one group with those who began adolescence at 11. In a few instances, the small number of available cases has made it necessary to put all those adolescent before 12 into the 12-year group. Those who were adolescent after age 15 are grouped with those who became adolescent at 15.

In order to make significant comparisons, it has been necessary to confine the analyses to groups that are homogeneous for sex, race, marital status, and educational level, as well as for the age of onset of adolescence. The tables in the present chapter cover all of those segments of the population which are now represented in the sample by enough cases to warrant statistical treatment. There has been no other basis for selecting the groups which are included.

The first difference to be observed between the males who become adolescent at an earlier age, and the males who become adolescent at an older age, is the fact that the younger-adolescent boys begin regular sexual activity of some sort, and begin having a regular outlet, more or less coincidently with the onset of adolescence. Some of them, as a matter of fact, had already experienced regular orgasm in pre-adolescence. On the other hand, the older-adolescent males, despite the fact that they have taken four or five years more in reaching adolescence, often delay a year or two beyond that before they ejaculate for the first time. Sometimes it is still longer before they acquire anything like regular rates of outlet. Early adolescent males ejaculate in the same year in which they become adolescent in 92 to 100 per cent of the cases (Table 67). The older-adolescent males ejaculate in their first year of adolescence in only about 80 per cent of the cases. Nearly every one (99.5%) of the younger-maturing boys acquires a regular sexual outlet between the time of adolescence and age 15.

There is an interesting correlation of the source of first ejaculation and the age of onset of ejaculation (Table 68, Figure 89). For the boys who become adolescent by 11 years of age, masturbation provides the first ejaculation in nearly three-quarters of the cases (71.6 per cent); but for the boys who become adolescent last, masturbation is the source of the first outlet in only about half of the cases (52.1 per cent). Nocturnal dreams, on the contrary, are the first source for only 21.6 per cent of the younger adolescent boys, but for 37.1 per cent of the late-adolescent males. The boys who mature first more often act deliberately in going after their first outlet; the boys who mature last more often depend upon the involuntary reactions which bring nocturnal emissions.

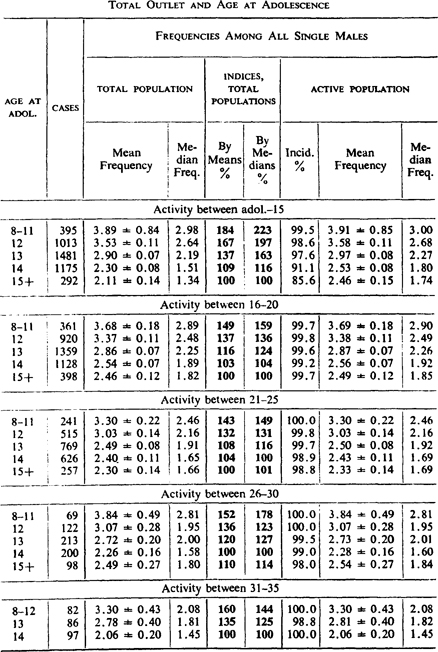

Table 69. Total sexual outlet, in single males, as related to age at onset of adolescence

Based on total white male population, including all education levels. The relative sizes of the frequencies are shown in the boldface columns as indices, with the lowest frequency in each 5-year period equalling 100 per cent.

The sexual activities of these boys who start the earliest are far from incidental. Between adolescence and 15 years, their rates are higher than the rates of any other group of single males, of any age, in any segment of the white population. Consequent on their quicker start, there are 16 per cent more of the early-adolescent boys than there are of the late-adolescent boys, who are active between adolescence and 15. Early-adolescent boys have four or five years in which to make a start in that period, while the later-adolescent boys have only one year in the period; but the higher incidence of activity among the early-adolescent boys must depend, in part, upon the generally higher level of performance in the group. This is confirmed by the fact that in all subsequent age periods there is still a slight but consistent difference in incidence in favor of the boys who became adolescent earliest.

The younger-adolescent and the older-adolescent males differ most in respect to the frequencies with which they engage in sexual activities. Tables 69 and 71 give the data for single and married males respectively.

Upon examining the record for the single males it will be seen that the boys who became adolescent first (by 11 years of age) have, on an average, about twice as much sexual outlet per week as the older-adolescent boys have during their early teens. If the means for the total populations are compared, the early-adolescent boys have 1.84 times as high frequencies as the slower males. If the medians are compared, the younger-adolescent boys have 2.23 times as much outlet. This is a material difference, and it is a real difference, since the averages for this age period between adolescence and 15 are calculated for the active years only, and not averaged with the pre-adolescent years (page 110).

These younger-adolescent boys constitute the most active group of single (unmarried) males in the whole population. In Chapter 7 it was concluded that out of all single males, taken as a group, the sexually most active are the 16-20-year old group; and that among the married males the highest frequencies are also in the 16-20-year period. While boys below 16, taken as a group, do not have frequencies as high as do the boys in their late teens, we now find that the activities of the early-adolescent individuals of this early teen-age group surpass those of the 16-20-year olds.

The mean frequencies of total outlet for the late teen-age boys, taken as a whole group, are 3.2 per week. The mean frequencies for the early-adolescent boys during the period between 11 and 15 average 3.9 per week. If this early-adolescent population is broken down into three educational levels (Table 70), the mean frequencies become 5.1 per week among the boys who never go beyond eighth grade in school, 4.2 per week for the boys who go into high school but not beyond, and 3.3 per week for the boys who will ultimately go to college. For each educational level, the maximum frequencies for the early-adolescent boys are in the earliest age period (except for the grade school group, where there is a slight increase in rate in the next two age periods; but the samples on these grade school boys are too small to be accepted as final). This location of the peak of sexual activity in the earlier adolescent years is scientifically most interesting, and it may have considerable social significance. The data emphasize the importance of a breakdown by age of onset of adolescence, in any final analysis of the problems of sexual behavior.

Not only do these earlier-developing boys have four years head start, and not only do they have higher rates of activity in those initial years, but they continue to have higher rates throughout the subsequent age periods. In the fifteen years that lie between ages 16 and 30, the younger-developing boys have about half again as much outlet as the later-developing boys. There is still a discernible difference in the age group 31 to 35, which is 20 to 25 years after the time of onset of adolescence! Considering the multiplicity of other factors that may modify the frequencies of sexual activity, it is surprising to find such a long-time correlation with the age of onset of adolescence. In spite of their early start, and in spite of their much higher expenditure of energy in sexual activity, these early-maturing males remain more active than those who were delayed in their adolescence.

In the histories of married males, the age of onset of adolescence proves to be as significant as in the histories of single males (Table 71). This is astounding! It might have been expected that the frequency of sexual activity for a married male would depend, to at least some degree, upon the wife’s interest and willingness to engage in marital intercourse; and certainly individual histories provide abundant examples of marital partners having to adjust their rates in accordance with each other’s wishes. Nevertheless, during the 16- to 20-year period, the outlets of the married males who were adolescent at an early age are about twice as high as the outlets of the males who were not adolescent until a later age—and this is exactly the difference that would have been found if they had remained unmarried. The effect persists throughout the lives of the married males, as far as data are available. While the differential between the groups decreases with advancing age, the rates of the younger-maturing group in the 46- to 50-year old period are still about 20 per cent higher than the rates of the slower-maturing group. Thirty-five years after the onset of adolescence, there is still a discernible effect, which persists in spite of marriage and in spite of all of the other events that affect sexual frequencies!

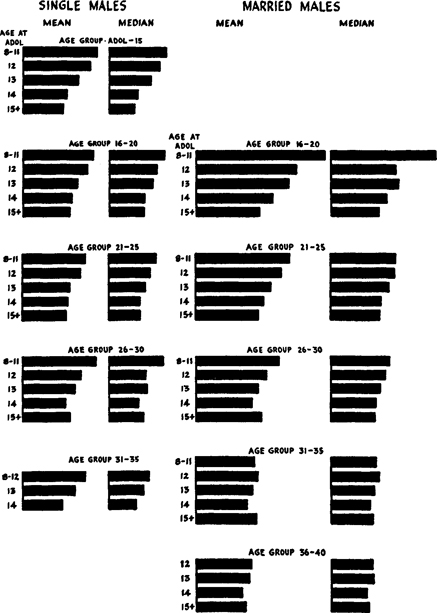

Figure 90. Relation of age at onset of adolescence to frequency of total outlet

Based on the total population. Relative lengths of bars show mean and median frequencies for each adolescent group. Single males in columns 1 and 2 ; married males in columns 3 and 4, Effects shown as continuing up to 30 years after onset of adolescence.

While the data in Tables 69 to 71 indicate a definite correlation between the ages of adolescence and the frequency of sexual activity, it must not be concluded that a simple causal relationship exists. Such misinterpretations of correlations are too commonly made, both in popular thinking and in technical scientific experiment. In many cases, more basic factors are involved, and two sets of correlated phenomena may be simply end products of the same forces. In the present instance, several basic factors may be operating. It is possible that the fact that an early-adolescent individual becomes sexually mature and erotically responsive at an earlier age, is the significant item. This gives him more years to become conditioned toward sexual experience before he reaches the teen-ages where social restraints become more significant. To put the matter in another way, the boy who becomes adolescent at 10 or 11 has not had as many years to build up inhibitions against sexual activity as the boy who does not mature until 15 or later; and it is quite possible (but not specifically demonstrable from the available data) that the younger boy plunges into sexual activity with less restraint and with more enthusiasm than the boy who starts at a later date. Moreover, it is possible that the patterns which are established by the earliest sexual activity, meaning patterns of higher frequency for younger-maturing boys, and patterns of lower frequency for older-maturing boys, are the patterns by which the individual’s subsequent life is ordered. At least part of the long-time effects may depend upon psychologic learning and conditioning.

But it is also probable that there are physiologic bases for the differences. It is difficult to know just what these may be, for, unfortunately, there are next to no studies of physiologic capacities in relation to the age at which individuals become adolescent. There are studies of younger children, adolescents, and older adults which show correlations between their absolute ages and their physiologic performances (Robinson 1938, and the references therein). There is at least one study (Richey 1931) which shows that there is some correlation between age at the onset of adolescence and blood pressures (systolic, diastolic, and pulse), the heights and weights that are ultimately attained, and some anatomic developments. Most significantly, these characters distinguish the various adolescent groups as much as six years before the onset of adolescence, and for at least six years after the beginning of adolescence. Further investigation of a larger number of physiologic characters operating over a longer period of years seems not to have been made. On the psychologic side, Terman (1925), in his study of geniuses, found that the individuals with the highest IQ’s were more often those who became adolescent first. It can, therefore, be suggested that the frequency of sexual activity may, to some degree, be dependent upon a general metabolic level which the individual maintains through much of his life. One who functions at a higher level at one period in his life is likely to function at a higher level through most of his life, barring illness and physical accidents that produce permanent incapacities. Casual observation would suggest that such an individual is not worn down by his quicker and more frequent responses to everyday situations, and there would seem to be no more reason for his being exhausted by his frequent sexual responses. Moreover, it is possible that the factors accounting for these other evidences of high metabolic level also account for early adolescence. Whether this is the correct interpretation is a matter which will have to be investigated through extensive research on the physiologic qualities of sexually high and low rating individuals.

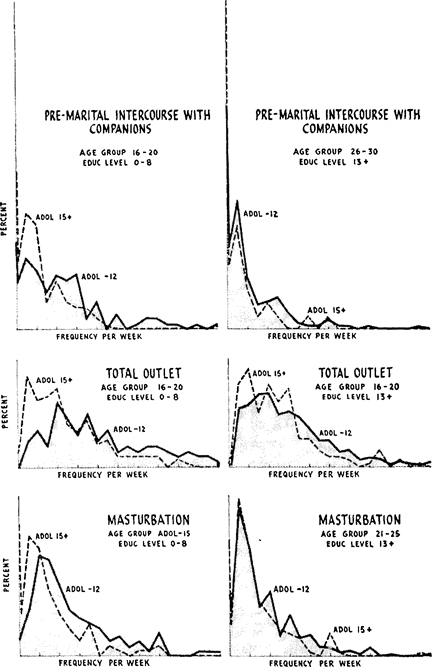

Figure 91. Relation of age at onset of adolescence to frequencies of masturbation, pre-marital intercourse with companions, and homosexual outlet

Based on single males. Relative lengths of bars show mean frequencies for each adolescent group. Effects shown as continuing up to 10 years for a grade school group (0–8); and up to 20 years for a college group (13+).

An examination of the sources of outlet of the younger adolescent males indicates that their higher rates of total outlet are not consequent upon an increased frequency in each and every kind of sexual activity. On the contrary, nearly all of the increased frequency comes from masturbation, premarital intercourse, and the homosexual (Tables 72–78).

Masturbation. While 90 per cent of the younger-maturing boys are involved in masturbation during their early teens, only 60 per cent of the late-maturing boys are involved in that same period. In successive five-year periods the number of earlier-adolescent males who are masturbating is 10 per cent to 115 per cent higher than the number of later-adolescent males who are so involved. Ultimately, nearly 99 per cent of the younger-adolescent boys have some experience in masturbation, while only 93 per cent of the later-adolescent boys are ever involved (Table 73, Figure 92). The younger-maturing boys have about twice as much masturbation as the late-maturing males during the early adolescent years, and 50 to 60 per cent more masturbation between 16 and 25 years of age, if they remain single. The frequencies calculated for the active population (i.e., for that portion of the population that is involved in this activity at all) are definitely higher in every age period for the males who matured first (Table 72). At this college level, these higher frequencies in masturbation are the chief source of the higher total outlets of the younger-maturing males.

Pre-marital Intercourse. In their earlier adolescent years, the younger-maturing boys are also much involved in pre-marital intercourse. Their frequencies are much higher than the frequencies for the late-adolescent group in this period (Table 74). In subsequent age periods, the frequencies among the boys who became adolescent first remain 50 per cent to 75 per cent higher.

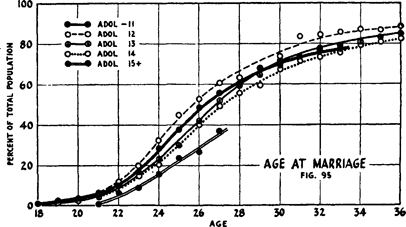

During this early adolescent period, the younger-maturing boys of the college level are involved in pre-marital intercourse in 11.8 per cent of the cases, while the older-maturing boys are involved in 7.0 per cent of the cases. The active incidence figures beyond 15 years of age are more or less the same for each of the adolescent groups; but the accumulative incidence figures (showing the number of males from each adolescent group who are ever involved, in the course of their lives) show some striking differences between the adolescent groups (Table 75, Figure 93). Ultimately 95 per cent of the early-adolescent boys of this college group obtain experience in heterosexual intercourse, either through pre-marital or marital relations, by age 30; but hardly more than 80 per cent of the late-adolescent males have arrived at such experience in intercourse by that age. For the males who become adolescent at intermediate ages, i.e., at 12, 13, or 14 years of age, the accumulative incidence curves are intermediate (Table 75, Figure 93). Ultimately the curves for the groups which are adolescent at 12 to 14 reach the same level (that is, 95%) which is obtained by the earlier-adolescent boys, but the group which does not become adolescent until 15 or later shows no evidence that it will get much beyond the 80 per cent mark. It is amazing that there should be nearly 20 per cent of these late-adolescent males who have not had some sort of heterosexual coitus by age 35. Most of the late-adolescent males who still lack coital experience in their thirties, have depended upon masturbation and nocturnal dreams rather than upon any other socio-sexual source for their outlet. An unusual proportion of these late-adolescent males is introvert and socially timid, and a considerable number is not yet married at 35 years of age (Table 76, Figure 95).

Homosexual Outlet. During the early adolescent years, twice as many of the early-maturing boys of this college level are involved in homosexual activities (Table 78). During subsequent age periods, the differences in incidence are not so great. Ultimately about 45 per cent of the early-adolescent boys of this college level have some homosexual experience, while less than 25 per cent of the late-adolescent males are ever involved. On the other hand, the frequencies with which homosexual contacts occur (Table 77) remain at about twice the height for these single males who first became adolescent, at least through the period between adolescence and 25. As a factor in the development of the homosexual, age of onset of adolescence (which probably means the metabolic drive of the individual) may prove to be more significant than the much discussed Oedipus relation of Freudian philosophy.

Other Outlets. Apart from masturbation, heterosexual coitus, and the homosexual, the other possible sources of sexual outlet are utilized to about an equal degree by the unmarried males from different adolescent groups. A single instance of such conformance is shown in Table 79, which covers the data for nocturnal emissions. Similarly, there are no fundamental differences between the incidences and frequencies in regard to heterosexual petting, and in regard to that part of the heterosexual intercourse which is had with prostitutes. There is some suggestion in the data that the farm boys who became adolescent first have more animal intercourse, but the number of active cases is too small to allow dependable calculations.

For the married males, the rates of total outlet among the early-adolescent individuals are definitely higher. There is some indication that most of this comes from marital intercourse, but the necessity for a six-way breakdown of the population before correlations can be run puts such a strain on the relatively smaller samples now available for married males, that further analyses cannot be made at this time.

Figure 95. Relation of age at onset of adolescence to age at marriage

Based on males of the college level. A social phenomenon is correlated with the factors which control onset of adolescence.

It would be of considerable interest to know whether an early onset of sexual activity and a lifetime of higher frequencies among the early-adolescent males show any correlation with the age at which individuals become sexually unresponsive or impotent, and at which they cease sexual activity altogether.

Some information on these points may be had from Table 71 where the record for married males is shown up to the age of 50. At that time, 100 per cent of the early-adolescent males are still sexually active, and their frequencies are still 20 per cent higher than the frequencies of the later-maturing males. Nearly forty years of maximum activity have not yet worn them out physically, physiologically, or psychologically. On the other hand, some of the males (not many) who were late adolescent and who have had five years less of sexual activity, are beginning to drop completely out of the picture; and the rates of this group are definitely lower in these older age periods.

It is unfortunate that the number of histories now on hand from still older males is too small to allow further calculations on these points. It has, however, been possible to calculate correlations between the age of onset of adolescence and the age of onset of impotence for a small group of 69 older males. For these cases, the coefficient of correlation proves to be 0.30. If the results can be trusted on a sample of this size, the low coefficient indicates that there is in actuality no significant correlation. In other words, the fact that an individual has started sexual activity in early life and has had frequent activity throughout a long period of years is not necessarily responsible for the onset of impotence in his old age. Impotence is as likely to occur at the same age among those males who did not start activity until late and whose rates of sexual activity were always low. The ready assumption which is made in some of the medical literature that impotence is the product of sexual excess, is not justified by such data as are now available. Impotence is clearly the product of a great diversity of physical, physiologic, and psychologic factors, and in each individual case a multiplicity of factors is likely to be involved.

It will be recalled (Chapter 7) that impotence is in actuality a relatively rare phenomenon. The clinicians, especially the urologists and endocrinologists, see so many individuals who are badly upset by impotence that they may find it difficult to believe that the incidence of the phenomenon is as low as we find it in the population at large; but again it should be pointed out that a clinic is no place from which to get incidence data.

Impotence in a male under 55 years of age is almost always the product of psychologic conflict, except in those exceedingly few cases where there has been mechanical injury of the genitalia or of the portions of the central nervous system which control erection, or in those similarly few cases where venereal or other disease has interfered with nervous functions. There is even some evidence that much of the impotence which is seen in old age is psychologic in its origin. In a larger number of cases than has ordinarily been realized, there are psychologic problems involving sex which may not develop until the later years of an individual’s marriage, either in connection with his marital intercourse, or in connection with other sexual activities which the male begins in his more advanced years. Psychologically, impotence is also predicated among older persons because they so often expect it; and the psychologic fatigue which follows long years of sexual experience is a prominent factor in the development of incapacity in old age. It will be recalled (Chapter 7) that only 27 per cent of the male population becomes impotent by 70 years of age, and that much older histories would be needed to .secure any large number of cases for a study of the relation of impotence to the age of onset of adolescence. Certain it is that among persons who become impotent by 70, there are histories of males who became adolescent at each and every age; but there are also histories of males who are still active after sixty or more years of sexual activities which were maintained at a maximum rate from the time they first turned adolescent at 10 or 11.

Figure 96. Comparisons of individual variation among early-adolescent and late-adolescent males

Based on single males. Solid lines show frequency distributions for males who became adolescent by 12. Broken lines and shaded areas show frequency distributions for males who did not become adolescent before 15.

In fine, the data add up as follows:

1. The males who are first adolescent begin their sexual activity almost immediately and maintain higher frequencies in sexual activity for a matter of at least 35 or 40 years.

2. The factors which contribute to this early adolescence apparently continue to operate for at least these 35 or 40 years.

3. Exercise of the sexual capacities does not seem to impair those capacities, at least as they are exercised by most of the persons who belong in the highest-rating segment of the population. While it is theoretically conceivable that very high rates of activity might contribute to physical impairment, or indirectly to diseased conditions, or to other difficulties in certain cases, the actual record includes exceedingly few high-rating males whose activities have had such an outcome.

4. Those individuals who become adolescent late, however, more often delay the start of their sexual activities and have the minimum frequencies of activity, both in their early years and throughout the remainder of their lives. If any of these individuals have deliberately chosen low frequencies in order to conserve their energies for later use, they appear never to have found the sufficient justification for such a use at any later time. It is probable that most of these low rating individuals never were capable of higher rates and never could have increased their rates to match those of the more active segments of the population.

5. In general, the boys who were first mature are the ones who most often turn to masturbation and, interestingly enough, to pre-marital socio-sexual contacts as well. They engage in both heterosexual and homosexual relations more frequently than the boys who are last in maturing.

There is some reason for thinking that these early-adolescent males are more often the more alert, energetic, vivacious, spontaneous, physically active, socially extrovert, and/or aggressive individuals in the population. Actually, 53 per cent of the early-adolescent boys are so described on their histories, while only 33 per cent of the late-adolescent boys received such personality ratings. Conversely, 54 per cent of the males who were last adolescent were described as slow, quiet, mild in manner, without force, reserved, timid, taciturn, introvert, and/or socially inept, while only 31 per cent of the early-adolescent boys fell under such headings. There are, of course, some individuals who do not fall clearly into either of these classifications. Prior to analyzing these data for the present chapter, we had no indication that we would find this sort of correlation and, consequently, all of the personality notations on the original histories were made without regard for the ages at which adolescence had occurred.

There is, of course, much individual variation on all of these matters, and there is no invariable correlation between personalities and rates of sexual activity. There are some very energetic and socially extrovert individuals who rate low in their sexual frequencies, and there are quiet and even timid individuals who have considerable socio-sexual activity. Behavior is always the product of a multiplicity of factors, no one of which can be identified as the exclusive or predominant agent in more than some small portion of the cases which one studies.

There is evidence that the late-maturing males have more limited sexual capacities which would be badly strained if, through any circumstance, they tried to raise their rates to the levels maintained by the sexually more capable persons. If further studies show that some physiologic quality, such as metabolic rate, works together with or through the hormones to determine the time of onset of adolescence, it may become a matter of clinical importance to exercise some control over that event. If this were done, would the subsequent sexual performance then be affected? Parents and clinicians may properly be concerned with such questions.