CHAPTER 14

FIELD OF SCHEMES

. . . as much the pride of Brooklyn as the Piazza San Marco is the pride of Venice and the Place de la Concorde is the cynosure of Paris.

—ROBERT MOSES

Had Rip Van Winkle slept a couple of centuries longer and awakened in Brooklyn circa 1945, he might well have declared it the mightiest city in the land. Brooklyn reached its apogee of power and population during World War II and its immediate aftermath. The war itself was arguably Brooklyn’s finest hour. No place in America contributed more blood, sweat, and toil to defeating the Axis powers—nor more lives. Some 325,000 Brooklyn men and women served in the armed forces during the war, 11,500 of whom died; tens of thousands more labored in the borough’s booming defense industry, churning out everything from helmets, searchlights, and bombsights to battleships and ingredients for the atomic bomb (Brazilian monazite sand, a rare-earth ore, was processed in Bushwick for the Manhattan Project). Brooklyn was the largest war-staging base in the United States. From the New York Port of Embarkation, headquartered at the Brooklyn Army Terminal, fully half the troops that fought in the war sailed overseas—three million in all. A third of all material and equipment used to defeat the enemy was also directed abroad from there, thirty million tons out of New York Harbor alone.1

Floyd Bennett Field also joined the fight, and long before the United States formally entered the war. Between January and November 1939, a huge fleet of Lockheed-Hudson patrol bombers for the Royal Air Force was flown from California to the airfield, where the airplanes—250 in all—were disassembled and crated for shipment to the British Isles. Flying boats from the base patrolled the coast for German U-boats, guarding merchant ships and convoys steaming for Great Britain under the Lend-Lease Program. So vital was the Brooklyn field to keeping Germany at bay that Nazi agents set up a secret surveillance outpost just a stone’s throw from its runways shortly after the British bomber shipments began. From a fishing shack on Gerritsen Creek equipped with powerful binoculars and a shortwave transmitter, agents of the massive Duquesne spy ring kept close tabs on operations at the base. The espionage ring, the largest ever caught on American soil, was broken in June 1941, but not before the spies (thirty-three in all) had spirited off classified plans from Brooklyn’s own Sperry Gyroscope Company and—more damaging still—from the Norden Company, whose bombsight was among the most closely guarded military secrets of the war. The same month as the spy ring bust, Floyd Bennett Field was formally acquired by the navy and renamed Naval Air Station–New York. The failed city airport was soon the busiest airfield in America, serving all through the war as a certification and overhaul facility for aircraft, and handling hundreds of transcontinental delivery flights each month as headquarters of the Naval Air Ferry Command and the eastern terminus of the Military Air Transport Service. More than sixty-five hundred personnel were based at Floyd Bennett at the height of the conflict. All told, some forty-six thousand warplanes were tested, certified, and readied for battle in Brooklyn during the war. Among these were a trio of aircraft most credited for the Allied victory in the Pacific air war—Grumman’s Long Island–made Avenger torpedo bomber and Hellcat fighter, which outdid the Mitsubishi Zero in speed and agility; and the muscular, gull-winged guardian angel of the Marine Corps grunt, the Connecticut-made Chance-Vought F4U Corsair.2

US Coast Guard Sikorsky HNS-1 at Floyd Bennett Field, c. 1949. Rudy Arnold Photo Collection, Archives Division, National Air and Space Museum.

The airfield also trained men and women to fly all these airplanes. In the summer of 1940, students from a dozen colleges and universities in the region—women from Adelphi; men from Brooklyn Polytechnic and Pratt institutes, Brooklyn College, Fordham, Columbia, and New York University—began enrolling in a Civil Aeronautics Authority pilot-training program at the field. Before long, Floyd Bennett was the busiest flight training center on the Eastern Seaboard. When entry requirements were lowered that December to meet soaring demand for aviators, more than a thousand aspiring fliers showed up for testing. By April 1941 some six hundred pilots had already earned their wings at the old airport. The field also became the first helicopter training facility in the world, schooling not only Americans but the first whirlybird pilots in the British army, Royal Air Force, and Royal Navy. So grateful was the crown for its new wings that instructor Frank A. Erickson, a coast guard captain, was granted an honorary knighthood by King George VI. Erikson himself made a number of breakthroughs at the Brooklyn airfield. He was the first to outfit a helicopter for medevac use, to demonstrate that a cable hoist could be effective in air-sea rescue, and—in September 1944—the first to pluck a man by helicopter from a life raft (floating in Jamaica Bay).3

These flying credentials were impressive, but they were nothing next to the firepower and muscle Brooklyn unleashed on the seven seas. Opened in 1801, the New York Naval Shipyard on Wallabout Bay—the Brooklyn Navy Yard—had been laying keels since 1817 and launched some of the most fabled ships in American history. The list is long and impressive: the sloop Vincennes (1826), first navy vessel to circumnavigate the globe; the Lexington (1826), which accompanied Matthew C. Perry on his 1854 Japanese expedition; the steam frigate Niagara (1853) that laid the first transatlantic cable; the armored cruiser Maine (1890) that sank with most of its crew after a mysterious explosion in Havana Harbor, an incident that—blown out of proportion by the press—helped ignite the Spanish-American War; and the battleship Arizona (1915), destroyed by a Japanese torpedo at Pearl Harbor, killing more than a thousand crewmen and precipitating America’s entry into World War II. The loss of the Maine was tragic enough, but the gloves came off in Brooklyn with the sinking of the Arizona. Shipbuilding at the yard was already in high gear, where soaring demand for labor opened shop doors for the first time to women in 1942 (twenty thousand applied for the first two hundred jobs). With several hundred buildings and thirty miles of railroad track, the Navy Yard had long been Gotham’s largest industrial plant; now it was also its greatest war machine. A city unto itself, its labor force rose to seventy thousand employees in twenty-seven trades and professions. They worked like demons, churning out an astonishing seventeen vessels between 1940 and 1945. These were no little boats but some of the most powerful warships ever built, including five aircraft carriers—the Bennington, Yorktown, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Kearsarge, and Oriskany—and three immense battleships: the North Carolina; the Iowa (launched seven months ahead of schedule); and the Missouri, last and largest battleship commissioned by the US Navy. It was on this vessel that Japan surrendered on September 2, 1945—poetic closure of a sort: World War II began with the sinking of a Brooklyn ship; it ended on another’s deck.4

Brooklyn Navy Yard, 1918. US Naval History and Heritage Command.

USS Arizona on the East River, 1918. Photograph by Robert Enrique Muller. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

In the months after V-J Day, Brooklyn was a city in the full flush of life renewed. It was a tough and scrappy town, still the butt of jokes, though mockery of the borough’s thick patois and immigrant ways was done a bit more cautiously now—rarely to the face of this polyglot place that had just helped save the world from fascism. And Brooklynites played as hard as they fought and worked. All through the war years, Coney Island was thronged by the largest crowds in its history—despite having its lights dimmed purple and blue to keep German U-boats from silhouetting ships against a glowing skyline. Soldiers and sailors on shore leave spent freely at the beach seeking respite from the war. They came for the girls and the games of chance, and for a thrilling new ride with military roots of its own. In the fall of 1940 George C. Tilyou’s eldest son and heir, Edward, brought to Steeplechase Park what would be its most celebrated ride since the namesake horse coaster—a 250-foot-tall, “parachute drop.” It was designed by a retired naval air commander, James H. Strong, who had seen primitive timber jump towers in Russia in the 1920s. In 1936 he developed a taller, steel-frame structure with patented safety mechanisms for the US Army, which continues to operate two similar towers at Fort Benning, Georgia. In 1939 Strong created a curvaceous civilian version for the Life Savers Candy Company exhibit at the New York World’s Fair. Its twelve twin-seat chairs were winched by motor to the top of the 170-ton tower and released by a “spider” mechanism to free-fall some twenty feet before being slowed in their descent by an opening parachute—itself secured by an array of guide cables. Though there was never a serious accident on the parachute jump, the ride was sensitive to wind and rain, required constant maintenance, and needed several strapping men to handle each chute. A money loser from the start, the jump nonetheless fixed Coney Island on the New York skyline and gave Brooklyn an icon as cherished and enduring as the Eiffel Tower.

The largest crowd to ever descend upon Coney Island’s beaches came on the Fourth of July 1955, the zenith of an unforgettable Brooklyn summer. The Brooklyn Dodgers were in Philadelphia that day, giving the Phillies a drubbing in a doubleheader. The team had brought home the National League pennant five times since 1941 but failed to win a single World Series championship. In each one of their previous division victories—1941, 1947, 1949, 1952, and 1953—the Dodgers were defeated by their perennial crosstown nemeses, the New York Yankees. But this time things were different. Powered by the pitching arms of Don Newcombe and Carl Erskine and the bats of Duke Snider, Carl Furillo, and Roy Campanella (a Most Valuable Player that year), the Dodgers muscled their way to the National League pennant, ending the season thirteen victories ahead of the Milwaukee Braves. On September 28, they once again met their old rivals at Yankee Stadium. Bronx won that day, despite a stunning home-plate steal by Jackie Robinson. But Lady Luck stuck by Brooklyn’s side and soon the series was tied at three games apiece. In Game 7 on October 4, Johnny Podres quieted both Yankee bats and Yankee fans with a 2–0 shutout victory. It was the first and only World Series the Brooklyn Dodgers would ever win.5

But even as Brooklyn shouted its home team to victory, winds of trouble and change were in the air. The borough’s titanic industrial sector was already beginning to falter, as companies struggled with cramped facilities, worsening traffic congestion, rising taxes, escalating utility costs, and infrastructure worn to the bone. Brooklyn’s once-dazzling port facilities were effectively obsolete by 1945, hobbled more than ever by that perennial problem of rail connectivity to mainland America. Its antiquated docks could not berth the increasingly large vessels of the postwar era, and the port was wholly unable to handle containerized shipping—an especially painful irony given that intermodal containerization, as we saw in chapter 9, was first proposed in the United States as part of the ill-fated Great Port of Jamaica Bay scheme. Now John Henry Ward’s brilliant, neglected idea came back to haunt the very place that inspired it. The end of the war also brought a tsunami of labor trouble. Pressed by the National War Labor Board, America’s unions had pledged against striking for the duration of the war (though there were numerous wildcat strikes). With the end of hostilities, however, the gloves came off. Four years of deferred demands by the rank and file, salted by soaring postwar inflation, precipitated a series of crippling union walkouts from coast to coast in 1946. In just the first six months of the year, nearly three million US workers took part in strikes; the Bureau of Labor Statistics called it “the most concentrated period of labor-management strife in the country’s history.” By year’s end, 10 percent of the nation’s workforce—4.6 million people—had struck.6

Aerial view of Coney Island looking west, April 1930, with Steeplechase Park and pier at center. Photograph by Fairchild Aerial Surveys, Inc. Collection of the author.

In New York, a quarter of a million workers walked off their jobs citywide in 1946 alone. Striking longshoremen paralyzed the docks; communications workers silenced telegraphy for a week; twelve thousand striking Teamsters choked off the flow of goods; even house painters struck, with ten thousand of them laying down their brushes. The most devastating action that year came from an unlikely corner—tugboat operators, thirty-five hundred of whom walked off the job in February. Just how vital these men and their boats were to daily life quickly became evident: Gotham was brought shivering to its knees within days. Schools, factories, libraries, museums, restaurants, and theaters were all ordered closed to save dwindling supplies of coal and heating oil. Sympathy for the men evaporated as the mercury fell. The New York Times called the tugboat stoppage “the most drastic disruption in the city’s life since the Civil War draft riots,” blaming the strikers for “eighteen hours of unparalleled confusion and staggering economic losses.” To many, the great postwar strike wave represented a heroic victory for New York City’s manual laborers, the men and women whose hands literally helped win the war. “Culturally, socially, and politically, blue-collar workers loomed larger at the end of World War II than at any time before or since,” writes historian Joshua B. Freeman, and the “size, strategic importance, and demonstrated power of the working class allowed it to play a major role in determining what kind of city New York would become in the postwar era.” What they and union leaders failed to anticipate was the increasing mobility of capital in the postwar era—the growing ability for industry and manufacturing to simply pull up stakes and leave what was becoming a very costly, very complicated town to run a business in. The increasingly contentious, often ugly clashes between labor and management were not the only cause of industry’s exodus from Brooklyn after World War II, but for many firms it was an especially compelling one.7

One by one, Brooklyn’s cornerstone industries began leaving for places with more modern infrastructure, more space, lower taxes, and less militant unions—or no unions at all. At first they went elsewhere in the metropolitan region, then to states where land was dirt cheap and labor unorganized—Virginia, North Carolina, Mississippi, Nevada. Many firms would eventually leave American shores altogether. Others simply shut down, such as the famed Continental Ironworks of Greenpoint, builders of the Civil War ironclad Monitor—archrival of the Merrimack and hero of the Battle of Hampton Roads. Sperry Gyroscope was one of the first “runaway shops,” vacating its Flatbush Avenue headquarters for Nassau County immediately after the war. In 1947 the E. W. Bliss Company—a tool and die works and developer of the first self-propelled torpedo—moved its operations to New Jersey and the Midwest after ninety years in Brooklyn. American Safety Razor, a leading maker of shaving products, departed for Virginia in 1954 after repeated strikes by the United Electrical Workers. Drug giant Squibb pulled up stakes for New Jersey two years later, after a century in Brooklyn. The company was founded in 1858 by Edward Robinson Squibb, a naval ship’s surgeon who ran a medical supply depot at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. His first laboratory was on Furman Street, by today’s Brooklyn Bridge Park (and just below Squibb Playground at the foot of Middagh Street). Close on Squibb’s heels was another giant of industrial Brooklyn—Mergenthaler Linotype, manufacturer of typesetting equipment that revolutionized the printing industry in the 1890s. After seventy-five years and a 114-day strike at its Ryerson Street complex, the company left Brooklyn for Long Island. Labor unrest at the borough’s many breweries—a legacy of Brooklyn’s once-huge German population—opened the doors to fatal competition from beyond the Hudson. A citywide walkout of seven thousand brewery workers in 1949, launched at the Rheingold plant in Brooklyn, created a suds gap that was obligingly filled by Anheuser-Busch. Three Brooklyn breweries closed as a result of the walkout; the rest soon followed. Brooklyn had forty-five breweries at the turn of the century, and even after Prohibition shuttered most of these, the borough was still producing 10 percent of all beer in America. By the mid-1970s there wasn’t a single brewery left in Brooklyn.8

Striking truck drivers prepare to deliver the goods after reaching an accord with the George Ehret Brewery, 1948. The company closed a year later, one of scores of Gotham breweries driven out of business by labor disputes after World War II. Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn Collection.

If the dying industrial sector sapped Brooklyn’s muscle and wealth, the closure of its beloved newspaper—the Brooklyn Eagle—stilled its voice and broke its spirit. Founded in 1841, the Eagle had been published without a break for 114 years and was one of New York’s oldest and most storied institutions. One of its early editors was none other than Walt Whitman. But the postwar years had been brutal. Circulation was falling, and by 1954 the paper was running in the red. Publisher Frank D. Schroth had nearly sold the entire operation to the Herald Tribune the year before, but the deal was dropped owing to fierce union resistance. Schroth fought a pitched battle with his large editorial and office staff—writers, reporters, copyeditors, advertising and circulation managers—who wanted higher wages and more benefits. Then, at midnight on Friday, January 28, 1955, the Newspaper Guild of New York called a strike. Though it was called on behalf of the paper’s 315 white-collar employees, the shop floor struck in sympathy; photo engravers, typesetters, press operators, and other “craft union” members all stayed home, making it impossible to publish even a skeleton edition. The strike dragged on all of January and February. By March it was clear the Eagle would never fly again. The end came on March 16, when a bitter Schroth declared that he was closing the Eagle permanently. He slammed the striking workers and their “malignant” guild for having “silenced forever” the Eagle by insisting on wages equal to those at Manhattan’s big dailies. The paper’s end dealt a stunning blow to Brooklyn. More than 650 people lost their jobs. The Times called the Eagle’s demise “a civic disaster”; to borough president John Cashmore it was “unthinkable” and a “great misfortune.” Brooklyn was now the largest community in America without a paper of its own, “doomed,” Schroth lamented, “to be cast in Manhattan’s shadow.” When the Dodgers beat the Yankees that fall, it was—horror of horrors—the Manhattan press that got to tell the world of sporting Brooklyn’s finest hour.9

Even if postwar relations between labor and management had been sweetness and light, there were many other daunting problems confronting Brooklyn’s industrialists. One of the most vexing was space. Downtown Brooklyn and its industrial zone west of the Navy Yard (today’s Dumbo) was overbuilt and terribly congested. The utility infrastructure, much of it dating from before the Civil War, could hardly keep pace with the needs of modern industry. State-of-the-art aircraft instruments were being made on streets paved in the age of clipper ships. What manufacturers needed in the booming postwar era was plenty of flexible space in which to grow—ideally all on the same floor—with ample water and sewer service and an electric grid robust enough to deliver the heavy amperes needed for big machines. Downtown Brooklyn could hardly meet any of these. Neither could it provide easy access to the nation’s road and rail networks, a problem that—as we have seen—had long been a thorn in Brooklyn’s industrial side. The problem was hardly limited to Brooklyn. There were some thirty-seven thousand manufacturing firms in New York City at the end of the war, mostly small, with just twenty-five workers on average, but together employing close to a million workers—“more manufacturing jobs,” writes Freeman, “than Philadelphia, Detroit, Los Angeles, and Boston put together.” Just ten years later, forty-two thousand of those jobs were gone. Gotham’s industrial age was over; but all was not doom and gloom, for a new service economy was rising. Even as manufacturers closed down, the city gained twenty-eight thousand jobs in banking, law, real estate, and insurance between 1947 and 1955 alone. And while industrial-sector jobs “dropped by 49 percent between 1950 and 1975,” writes Suleiman Osman, “employment in finance, insurance, and real estate increased by 25 percent, in services by 52 percent, and in government by 53 percent.”10

Gotham’s age of smokestacks may have been ending, but City Hall did much to hasten its industrial sector to the exit door. Labor strife and lack of space were vexing issues for American Safety Razor, but the straw that broke the company—and sent it packing to Virginia—came in the form of city plans to condemn its vast complex of buildings on Jay and Lawrence streets for an urban renewal project. That fourteen thousand employees—85 percent of them women—lost their jobs when the company left town was particularly egregious given that the city later changed its plans and spared the buildings (they were subsequently occupied by Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute). It was a drama that played out all over New York as the juggernaut of urban renewal gathered steam. In their efforts to fortify and renew New York, postwar planners helped push out the very businesses New Yorkers needed to stay employed and out of poverty. Urban renewal cleared out urban jobs as rapidly as it did urban blight. As Joel Schwartz revealed in The New York Approach, projects on both sides of the East River caused the elimination of some 17,900 jobs by 1955, nearly half of which were in downtown Brooklyn alone, lost to the same urban renewal project that pushed American Safety Razor out. Given the manifold challenges of the postwar period, the very last thing firms needed was the threat of eviction by a city that should have treasured their presence. With so tenuous a foothold, mere rumors could send a firm over the edge. “Once forced to move,” writes Freeman, “many companies left the city entirely,” while others, “fearing inclusion in a future redevelopment site, refrained from expanding or modernizing their buildings.”11

For all its good intentions, urban renewal did what the Axis enemy failed to do during the war—pulverize American cities. With the help of the federal government, urban renewal cleared some fifty-seven thousand acres of land nationwide by 1966, displacing more than 300,000 families. It was made possible in large part by Title I of the 1949 Housing Act, which provided vast sums of federal aid to help municipalities eliminate blighted neighborhoods and free valuable center-city land for upscale residential and commercial redevelopment. The objective “was not to wipe out the slums in order to build decent housing and pleasant neighborhoods for low-income families,” writes Robert Fogelson; “Rather it was to curb decentralization—to induce the well-to-do to move back to the center by turning slums and blighted areas into attractive residential communities—and, by so doing, to revitalize the central business district to ease the cities’ fiscal plight.”12 Redevelopment authorities were formed to carry out this work, armed with broad powers to condemn land and sell or lease it to developers at below-market value (the federal government would pay up to two-thirds of land-clearing costs). Urban blight, the putative enemy, proved conveniently elastic in meaning. The widely used appraisal standards from the American Public Health Association defined blight as a matter of not only substandard buildings but “neighborhood deficiencies, including high population and building density, extensive non-residential land use, inadequate educational and recreational facilities, dangerous traffic, and unsanitary conditions.”13 That effectively described Brooklyn’s oldest, poorest, most congested wards—everything from Brooklyn Bridge south to Borough Hall and west to the Navy Yard.

This aging quarter of Gotham sat squarely in the bombsights of that Lord Shiva of urban landscape, Robert Moses. Moses exploited Title I as effortlessly as he had the various New Deal programs to assemble the largest portfolio of urban renewal projects in the United States. “Between 1949 and 1961,” writes Sandy Zipp in Manhattan Projects, “New York City alone accounted for 32 percent of all construction activity under the federal law.” No city would suffer more in the name of urban renewal than New York, and nowhere was the devastation greater than Brooklyn. There, as we will see, Moses carried out the largest, most complex and costliest urban redevelopment program in city history. But Title I was only part of the picture in this frayed and aging part of town. From 1945 to 1965, the vast swath of urban ground south and east of the Brooklyn Bridge endured an unprecedented campaign of metropolitan modernization. Hundreds of structures were blown away to make room for new parks, courthouses, and a variety of civic and institutional buildings. A major arterial, the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, was punched through the district, hooked up to the Brooklyn and Manhattan bridges with sprawling coils of access ramps. The benighted Sands Street community just west of the Navy Yard was rubbed out to make way for the Farragut Houses, while twenty-two blocks to its south were razed for the Fort Greene Houses—the largest public housing complex ever built in the United States (subject of chapter 15). “No other part of New York,” marveled the Times in 1955, “has undergone as much outward change since World War II as the area spreading south and east of the Brooklyn Bridge.”14

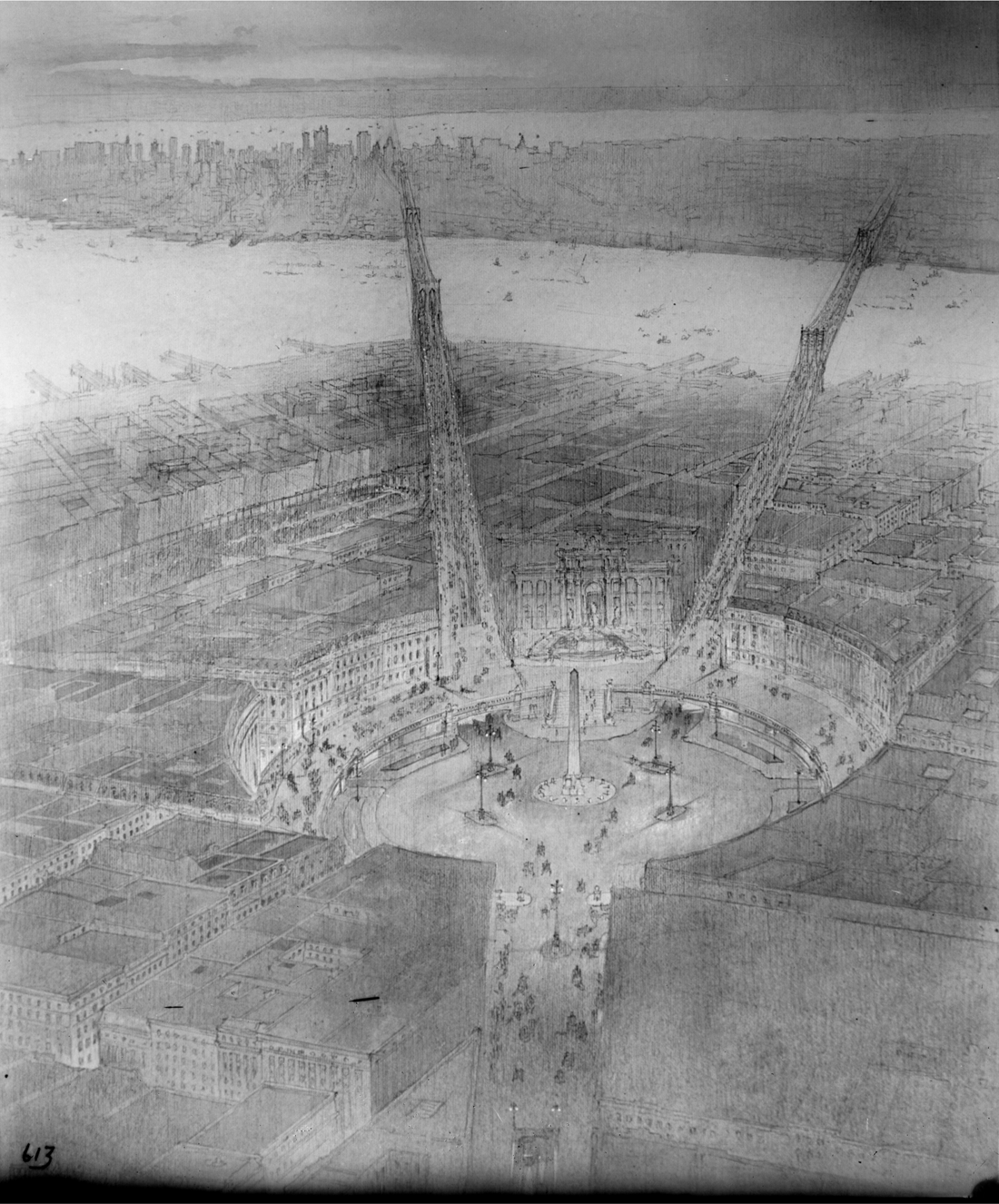

Much of this urban upgrading had been schemed, dreamed, and fantasized about decades before Moses came on the scene. Creating a formal open space at the foot of the Brooklyn Bridge—a kind of majestic foyer to Brooklyn—was a perennial subject of debate. Even before the span was completed, calls were made for “a sort of plaza” at Washington and Sands streets, and to extend Flatbush Avenue north from Fulton Street to create a visual axis between Grand Army Plaza and the bridge towers—a grand gesture of linkage straight out of Haussmann’s Paris playbook. By 1895, the Brooklyn end of Roebling’s bridge was pure chaos—a helter-skelter jumble of tracks and catenary dominated by the looming hulk of the Sands Street depot—a colossal elevated structure, nearly four hundred feet long, that was meant to be temporary but endured for half a century. The depot brought together a Medusan tangle of rapid transit and streetcar lines—several leading over the bridge to Manhattan. With outrigger support columns resembling the legs of a great arachnid, the els extending out from the depot were collectively known as “Brooklyn’s Black Spider.” There were moral hazards, too, with no fewer than forty saloons within a short walk of the bridge. All told it was “horribile dictu,” remarked Brooklyn columnist Cromwell Childe; “If you want to get a New Yorker to invest in Brooklyn real estate,” he suggested, “the best method is to blindfold him until you have reached several blocks past the City Hall.” Improvement plots came and went like the robins of spring. The delightfully named Tree Planting and Fountain Society of Brooklyn advanced an “ingenious scheme” by Albert E. Parfitt in 1895 to beautify the Brooklyn end of the bridge, promising “a very park like prospect.” Not long after, Whitney Warren, one of the architects of Grand Central Terminal, proposed a great circular plaza (discussed in chapter 10) to receive both the Brooklyn and Manhattan bridge ramps and distribute traffic to all points of town via a plexus of radiating avenues. With an obelisk anchoring its center, his Brooklyn-baroque piazza would have pleased Sixtus V, the planner-pope of sixteenth-century Rome.15

After 1900, pressure mounted from real estate, business, and civic groups to rid downtown of its unsightly mat of elevated tracks. These groups were well represented in the leadership of the Brooklyn Beautiful movement, which made creating “a proper and dignified entrance” to the borough a priority. One of the first things Daniel Burnham recommended on his 1911 visit with the Brooklyn Committee on City Plan was eliminating the Sands Street train depot to open views to the East River bridges. The movement’s guiding light—preacher-planner Newell Dwight Hillis—urged city bridge commissioner Arthur J. O’Keeffe to help make this happen. “We have a good deal of pride in our borough,” he professed, “but we have been going into Brooklyn through the back door and the kitchen for a great many years.” A blue-ribbon commission headed by Frederic B. Pratt in 1913 echoed the sentiment, pressing that “no city can hope to improve and brighten itself and still neglect its front door.” O’Keeffe’s successor, Frederick J. H. Kracke, committed himself to embellishing that front door, presenting plans to Mayor John Purroy Mitchel for not just a plaza at the bridge terminus but a municipal center in full-blown City Beautiful mode—itself an idea batted around for years. In truth, little could be done until downtown Brooklyn’s elevated transit lines were replaced with subways, a process that began in earnest with signing of the Dual Contracts of 1913.16

The Piazza del Popolo in Brooklyn: Whitney Warren’s 1905 plan for an obelisk-anchored baroque plaza with avenues leading to the Brooklyn and Manhattan bridges. New York City Municipal Archives.

Brooklyn Terminal of the Brooklyn Bridge, 1903. Detroit Publishing Company Photographic Collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Negotiated by zoning pioneer and Brooklyn Committee executive Edward Murray Bassett, the Dual Contracts vastly expanded subway service throughout the city, establishing the system we know today and giving Gotham a new set of acronyms—IRT, BRT, BMT. As part of the deal, Brooklyn was connected to Manhattan by three new rapid transit tunnels under the East River—infrastructure that made rail service over the Brooklyn Bridge superfluous, thus allowing for removal of the much-loathed Sands Street terminal. But it took another twenty years and the fusion administration of Fiorello La Guardia to bring all this about. Within weeks of his inauguration, La Guardia began negotiating with the BMT to remove the terminal and Fulton Street el, collaborating with newly elected borough president Raymond V. Ingersoll to jump-start the long-stalled bridge plaza. Frederick Kracke, now commissioner of plant and structures, was asked to dust off his 1914 plans. On June 14, 1935, the Board of Estimate voted unanimously in favor of the project. Help came, oddly enough, by way of far-off Bergen Beach, where fraudulent condemnations for the Jamaica Bay port project—the result of “collusive activities by former city officials,” including Mayor Jimmy Walker—had cost the city $3.2 million in excess awards. Recovered, the funds “saved in Brooklyn,” announced La Guardia, “should be spent in Brooklyn.” The money enabled the city to acquire a ten-square-block area between the bridge ramp and Borough Hall. Demolition began within weeks, and by early 1936 the site was cleared of everything but the elevated station and tracks. That August, park commissioner Moses sent a force of two hundred WPA workers to transform the site with lawn, gardens, and shade trees. The first public event planned for the new space was a “community sing” on New Year’s Eve 1936, with an appearance by Metropolitan Opera soprano Martha Atwood and song lyrics projected on a Washington Street building façade. Two years later the vast plaza was officially named after the late Brooklyn Heights minister and social reformer S. Parkes Cadman. The honor very nearly went to Brooklyn’s famous, flawed abolitionist minister Henry Ward Beecher.17

G. W. Peters, “The New Terminal in Brooklyn of the New York and Brooklyn Bridge.” From Harper’s Weekly, June 15, 1895.

Though the Sands Street depot still loomed heavily over the space, its days were numbered. Demolition of the Fulton Street el, which ran along the plaza’s west side, commenced on June 17, 1941, with Mayor La Guardia personally making the first cut of steel with a welder’s torch. A crowd of three thousand gathered to watch the rusty structure’s “tentacles” come down. At a luncheon that afternoon, the Downtown Brooklyn Association toasted its demise; no longer would the el “cast a shadow over the heart of Brooklyn.” Fulton Street had long been the flagship of Brooklyn retail, even if encumbered overhead. With the street basking in sunshine for the first time in fifty-three years, the sky was quite literally now the limit: Fulton Street could well become one of the nation’s “swank shopping centers.” Pratt Institute architecture students offered sketches of what the rejuvenated thoroughfare might look like. There would be shiny buses instead of rattletrap trolleys and streetlights—vowed association president Henry J. Davenport—“similar to those on 5th Ave., Manhattan.” For the rest of that summer, Brooklyn delighted in the “mammoth production” staged on its downtown streets as the Fifth Avenue and other sections of elevated track fell. The Eagle called the show “Slaying of the Black Spider,” and pronounced that as pure spectacle, “Billy Rose or any other Broadway impresario couldn’t have done a better job.”

Demolition of BMT Fulton Street elevated at Lafayette Avenue, c. 1940. Collecton of George Conrad.

The fiery sting of the acetelyne [sic] torches against the antiquated steel structure sends sprays of colorful, glowing sparks downward and keeps the thousands of watchers enthralled in the performance of the iron workers . . . star performers in this show as they scamper along their precarious perches atop the steel trusses, applying the flaming “death ray” to the tentacles of the spiderish framework.18

The Sands Street station complex came down at last in 1943, ending its fifty-year run as a “temporary” structure. Cadman Plaza had shed its last encumbrance and was entirely opened to the sky. In a few years only the Myrtle Avenue line—stubbed off at Jay Street—remained of the once-vast network of downtown Brooklyn els. Removal of all this heavy infrastructure was also a Herculean recycling effort. The section of the Fulton Street el between Court Street and Lafayette Avenue alone yielded three thousand tons of scrap steel. Rumors swirled that the steel was sold to Japan, perhaps destined to be returned in the form of artillery shells. In truth, nearly all of it was purchased for reuse by Bethlehem Steel. Some of it might well have come back to Brooklyn to help build a warship in the Navy Yard.

Removing the dark maze of elevated tracks from downtown Brooklyn had long been seen as an essential first step toward creating a new civic and administrative center at the heart of the borough. As discussed earlier, the idea for a civic center had been batted about since the 1900s and was taken up with particular enthusiasm by Newell Dwight Hillis and his circle of patrician improvement advocates. His Chicago pal, Daniel Burnham, endorsed placing “a proper civic center” between the Brooklyn Bridge and Borough Hall. In an April 1913 letter to Frederic B. Pratt, city comptroller William A. Prendergast avowed that “there should be a civic center in Brooklyn,” suggesting he form a committee of citizens to study the problem. Pratt tapped nine of his Brooklyn Beautiful cronies—Alfred T. White and Edward Murray Bassett among them—to spend the next two months drafting a plan. Working closely with Edward Bennett, Pratt’s Committee of Ten recommended placing the long-anticipated new Kings County courthouse behind Borough Hall, and a new municipal office building just opposite to the north, on the triangular site occupied today by the Korean War Veterans Park. From the air the scheme resembled a great hourglass or bow tie. The Eagle’s January 1914 special section on the Brooklyn City Plan featured Bennett’s rendering of the projected civic center on the front page.19

Demolition of blocks around Sands Street and Brooklyn Terminal, August 1937. New York City Municipal Archives.

Of course, not everyone agreed that this was the best way forward. A young New York society architect named Charles S. Peabody proposed an alternative scheme, which the New York Times called “daring and original” and treated to a full-page article—the result more likely of Peabody’s family connections than of a sudden interest in Brooklyn on the part of the paper (Charles was the nephew of banker and philanthropist George Foster Peabody, benefactor of the Peabody Awards). Charles Peabody was a graduate of Harvard and the École des Beaux-Arts who had designed the Delaware and Hudson train station in Lake George and Mayborn Hall at Vanderbilt University. His civic center proposal featured a single megastructure for both the county courts and borough offices. He placed the courtrooms in a six-story perimeter building wrapping the full block behind Borough Hall and creating a great courtyard from which a twenty-six-story municipal tower rose. He positioned the tower to backstop a visual axis from the Brooklyn Bridge to Borough Hall, anchoring the view of Brooklyn as seen by anyone coming over from Manhattan. The committee rejected Peabody’s scheme outright, claiming that combining two separate government entities in a single building—an arranged marriage of sorts—would lead to constant quarrels over management and upkeep. Moreover, Brooklyn was a city of churches and homes, not skyscrapers. “There is,” the Eagle laconically noted, “opposition to high buildings in Brooklyn.” Though a much smaller municipal building was eventually built on the site, not until 1926 would anything in Kings County reach the height of Peabody’s Priapus. Senior Brooklyn architect Frank J. Helmle—designer of the Prospect Park Boathouse and the recently restored Hotel Bossert in Brooklyn Heights—delivered the slap-down, berating Peabody’s scheme as ill-considered and extravagant: “a Manhattan architect’s idea of what Brooklyn needs.”20

Edward H. Bennett, Proposed Sites for Courthouse and Municipal Building, 1913. From “Brooklyn City Plan,” special supplement to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 18, 1914. Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn Collection.

It wasn’t until the 1930s that real headway was made on the long-anticipated Brooklyn Civic Center. By now, the City Beautiful generation of Brooklyn improvers had faded from the scene, and it was an outside entity—the Regional Plan Association—that jump-started efforts to revitalize the heart of Brooklyn. The second volume of its landmark Regional Plan of New York and Its Environs—the first long-range plan for the metropolitan region—included proposals for a Brooklyn Civic Center. With removal of the elevated lines and creation of the bridge plaza already well under way, the RPA team—led by British town planner Thomas Adams—shifted the entire civic center north of Borough Hall, just as city bridge commissioner Frederick Kracke had suggested years before. They offered two schemes. The first, favored plan called for widening Washington Street (now Cadman Plaza East) into a grand Parisian-style boulevard similar in scale and appointment to Boston’s Commonwealth Avenue. The street was chosen because it lined up perfectly with Borough Hall in one direction and the south tower of the Manhattan Bridge in the other, creating a symbolic link between New York’s most populous and most powerful boroughs. A formal plaza at the foot of the Brooklyn Bridge anchored the north end of this axis, with grand civic and institutional buildings set in big perimeter blocks just west of Washington Street—where Cadman Plaza and the Korean War Veterans parks are today. The second RPA scheme, clumsy and impractical, drove an axis from Borough Hall down a realigned Liberty Street to a grand municipal tower much like the Municipal Building on Chambers Street.21

Though neither of these schemes was adopted, the Regional Plan Association effectively rekindled interest in Brooklyn for a civic center of its own. It also made clear that focusing solely on a grand administrative complex would do little to solve the many interlocking problems in this “least developed and most disordered part of the borough.” Adams and his team stressed that downtown Brooklyn should be approached as a whole. “The civic and business center, the residential district of Brooklyn Heights, the approaches to Brooklyn Bridge and the waterfront development on the northern end of the Upper Bay,” he wrote, “must be dealt with together in a bold scheme to make Brooklyn’s center one of appropriate dignity and distinction.”22 It was Brooklyn’s most widely read daily—the Eagle—that took up this call. Over the next twenty years it published a barrage of articles and editorials calling for downtown renewal. Leading the crusade was no scion of Anglo-Dutch Brooklyn, but a Dixie transplant named Cleveland Rodgers. Raised by a single mother in Greenville, South Carolina, Rodgers aspired to be a playwright but paid the bills working as a typesetter. He came to New York in 1909 with a panama hat in hand and dreams of Broadway fame, taking a job with the City Club investigating overcrowding on the Third Avenue Elevated. He didn’t even have enough money to buy the newspaper, and recalled fishing a copy out of the trash to read about the shooting death of Stanford White.

Rodgers eventually found a job setting linotype at the Eagle, and before long was writing drama reviews, articles, and editorials for the paper. He moved from the composing room to the editorial office, becoming associate editor in 1920 and succeeding Arthur M. Howe in the Eagle’s top job a decade later. Rodgers had a keen interest in city planning, sparked by a boyhood visit to the 1901 Charleston Exposition. “There I glimpsed the possibilities of man-made beauty for the first time,” he recalled; “It was a beautiful exposition, Spanish Renaissance buildings with red tile roofs, under clear blue skies.” Strings of electric lights came on as the sun dipped behind the moss-bearded oaks, setting aglow the buildings, courts, and colonnades. To Rodgers, the Charleston Exposition was a signal moment in his youthful education: “It gave me the first ideas I ever had of great buildings in landscaped areas.” One of the first big stories Rodgers covered as an Eagle reporter was the destruction by fire of the old Equitable Assurance Building in lower Manhattan, and its replacement by a forty-two-story tower that obliterated nearly all sunlight from surrounding streets. Outrage over the structure led to the formation of the Committee on the Limitation on the Height and Bulk of Buildings. It was this group, led by Brooklyn’s Edward Murray Bassett, that drafted the city’s first zoning resolution—“the beginning,” wrote Rodgers, “of comprehensive city planning in the United States.”23

Downtown Brooklyn looking toward the Brooklyn Bridge, 1935. The Fulton Street elevated runs across the left side of image. The Brooklyn General Post Office on Tillary Street, center right, is among the few buildings in this scene that would survive the demolitions of the coming decade—and just barely. New York City Municipal Archives.

Same view, 1938. The el and Brooklyn Bridge Terminal at Sands Street would survive for another five years before being cleared to make way for Cadman Plaza. New York City Municipal Archives.

As editor of the Eagle, Rodgers had no little sway over the course of civic affairs. But it was his appointment in 1938 to the New York City Planning Commission that gave him real authority to shape the built environment of both Brooklyn and the city at large. The commission was created by the 1936 New York City Charter “to advise and report on all questions affecting the growth of the city.” Advisory to the mayor and Board of Estimate, it was charged with drafting the city’s master plan, reviewing citywide subdivisions of land and conducting public hearings to gauge public support for and opposition to projects. The first commissioners were appointed two years later, and included Rodgers; Lawrence M. Orton, a Cornell graduate whom Rodgers considered “the best qualified technical planner on the Commission” (he had worked with Thomas Adams at the RPA); Board of Estimate engineer Vernon S. Moon; Edwin A. Salmon, later planning consultant to Brooklyn borough president John Cashmore with expertise in hospitals and health care; and Arthur V. Sheridan, namesake of the Sheridan Expressway. New Dealer Adolf A. Berle, Jr., was the commission’s first chair, succeeded shortly after by another of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “Brain Trust,” Rexford Guy Tugwell. That Rodgers lacked a background in design or planning was hardly debilitating; rather, it enabled him to maintain an objectivity that transcended the particulars of any one profession. He took to heart Tugwell’s remark that the commission’s main business was “to think about the City of New York,” keeping the big picture in sight when others got lost in the weeds. Rodgers authored the commission’s first annual report and later published a book—New York Plans for the Future (1943)—about the city’s development history and the challenges it faced.24

As Brooklyn’s voice on the commission, Rodgers did all he could to bring its declining downtown to the promised land of urban renewal. He found his Moses—literally—when Mayor La Guardia appointed the master builder to the planning commission in 1941. Rodgers deeply admired Moses, later authoring a book about him and ghostwriting much of his autobiography; Moses felt similarly about Rodgers, whom he described as “a most valuable public servant.” Rodgers’s seat on the Planning Commission and bromance with Moses enabled him to move the Brooklyn Civic Center to the very top of New York’s postwar public-works agenda. Though he had formally severed ties to the Eagle once he joined the Planning Commission in 1938, Rodgers continued to enjoy a free pass to its editorial page. Thus did “Creation of a Civic Center” become part of a ten-point “Program for Brooklyn” rolled out to mark the newspaper’s centennial in October 1941. “It is the conviction of this newspaper,” began a piece almost certainly authored by Rodgers, “that nothing would do more to increase the self-respect of Brooklynites and their pride in their home town than the creation of a real civic center of the general type boasted by every other city of any size in the nation.” The Eagle commissioned a plan of its own for the Cadman Plaza area, prepared by the firm of Slee and Bryson and proposing a rampart of municipal offices, courthouses, and educational buildings on both sides of Cadman Plaza. It was presented in a full-page feature article by state supreme court justice and former chair of the Joint Legislative Committee on Housing Charles C. Lockwood, in which readers were admonished that in order “to regain and maintain its prestige, Brooklyn must plan and act now.” Published fatefully on December 7, 1941, the day Japanese forces attacked Pearl Harbor, the plan was completely ignored.25

City planning commissioner Cleveland Rodgers (in white) cuts a ribbon, 1939. Robert Moses is second from left; former governor Al Smith on right. Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn Collection.

Not until nearly the war’s end was anything significant done again on the Brooklyn Civic Center. The catalyst for action this time was not a cluster of new buildings, but an open space—Cadman Plaza, now selected as the site for a memorial to the 11,500 Brooklyn souls lost in the war. Prompted by Moses’s call for “one impressive memorial in each borough,” Eagle publisher Frank Schroth announced a design competition for a Brooklyn War Memorial on June 6, 1944—the day of the Normandy invasion and over a year before the war actually ended. The winners of the Brooklyn War Memorial competition were announced in late May 1945. The competition jury—including borough president John Cashmore, Board of Education chief Mary E. Dillon, and Edward C. Blum of the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences—sorted through some 243 entries from all quarters of the country. But despite a blind review process, the first- and second-place teams were suspiciously dominated by some of Moses’s closest confederates.26 Moses was quietly steering the effort, for he had by now become heavily invested in the future of downtown Brooklyn. Fed up with the bewildering array of plans and proposals advanced for the civic center over the years, he admonished Brooklyn to be “realistic about the future” and stop paying attention to “Buck Rogers” plans by “visionaries with crackpot ideas who would have streamliner landing fields on every corner.” But Moses’s plans were themselves hardly modest. With the Planning Commission increasingly under his thumb, plans for the Brooklyn Civic Center swelled in scope and scale in step with the titanic Moses ego. No longer was the project about erecting a new municipal center at Cadman Plaza; instead, it expanded to swallow up most of old Brooklyn—from the Columbia Heights waterfront east to Pratt Institute; from the crowded slums of the Navy Yard south to Atlantic Avenue. It would become the largest and most complex project in Moses’s long career—“the biggest piece of redevelopment,” wrote Lewis Mumford, “the municipality has ever attempted.”27

Brooklyn War Memorial campaign poster, 1946. Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn Collection.

The Planning Commission report on the Brooklyn Civic Center, written by Rodgers, was released in March 1945 and made officially part of the city’s master plan just weeks before the war memorial competition results were announced. It was based largely on a new study of downtown Brooklyn by Moses’s most trusted urban designers—Gilmore D. Clarke and his gifted understudy, Michael Rapuano. Clarke—adviser to the ill-fated Marine Park design competition many years before—was now the most prominent landscape architect in the United States, with an honorary doctorate from Yale and the Architectural League’s coveted Gold Medal. Clarke was running a busy practice in the city, chairing the US Commission of Fine Arts and also serving as dean of the College of Architecture at Cornell University, spending three days a week in Ithaca. By this time, Moses and Clarke had known each other for twenty-five years. They first met when the latter was supervising construction on the Bronx River Parkway. Moses, then a young staffer with the Bureau of Municipal Research, was sent to investigate a suspected case of corruption—a bridge was being built over a dry meadow near Scarsdale. Moses was led to Clarke, who explained that it was wiser to erect the bridge over dry land and divert water back under it than to build within the existing channel, which would require pumps and coffer dams. When newly elected Mayor La Guardia appointed Moses citywide commissioner of parks in 1934, he made Clarke his consulting landscape architect.28

Proposed cenotaph and reflecting pool at Cadman Plaza, Brooklyn War Memorial competition, 1945. Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn Collection.

One of the 243 entries in the Brooklyn War Memorial competition for Cadman Plaza, 1945. Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn Collection.

Distinguished guests discuss an architectural model for the Brooklyn War Memorial, 1945. Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn Collection.

Their ensuing reconstruction of the city’s aging parks infrastructure was run more like a military operation than like a public-works project. “Major” Clarke, as he was known, had experience with both. As an officer with the Sixth Engineers of the US Army’s Third Division, he had built bridges and roads at the front during World War I. Moses entrusted Clarke with great authority at the Arsenal, the Parks Department’s offices in Central Park, giving him veto power over all park design work; no bids or blueprints left the building without Clarke’s signature. Clarke was also authorized to hire an officer corps and did so by recruiting to New York the best of his former staff from the Westchester County Park Commission. Well into the 1960s, a plurality of the “Moses Men” could claim a connection to Clarke and Westchester.29 Michael Rapuano was first among them. A working-class son of Italian immigrants, Rapuano attended Cornell on a football scholarship, graduating in 1926 and winning the Rome Prize in landscape architecture the following year. Clarke recruited Rapuano to Westchester upon his return from the American Academy in Rome in 1930, where the young man quickly became Clarke’s aide-de-camp. As he spent more and more time in Washington and Ithaca, Clarke delegated much of his responsibility to Rapuano, deputizing him to head the Parks Department’s landscape design team. In this role Rapuano prepared new plans for City Hall, Washington Square, and Madison Square parks, reworked Charles Downing Lay’s extravagant scheme for Marine Park, and drafted designs for Orchard Beach, Randall’s Island, and Jacob Riis parks. He worked closely with Clarke and Aymar Embury III on the Central Park Menagerie and Prospect Park Zoo; with M. Betty Sprout on the Central Park Conservatory Garden; and with Clarke and fellow Westchester alumnus Clinton F. Lloyd on the renewal of Riverside Park. Clarke and Rapuano formed a professional partnership in 1939; among their first projects was the master plan for the 1939 New York World’s Fair.

It’s hardly surprising that Moses would look to this capable pair—on their way to becoming the most influential American landscape architects since the Olmsteds—to realize his vision for downtown Brooklyn. Their first task was to reconfigure the war memorial into something more to Moses’s liking. Given the enormous sacrifices made by Brooklyn families for the war effort—no community in America lost more of its own in the conflict—the war memorial project was taken very seriously in Brooklyn. Much of the money for construction came by way of public subscription and from fund-raising efforts at the neighborhood level and in the borough’s innumerable churches, synagogues, and schools. But there was a shortfall, and the project had to be scaled back and started over, allowing Moses to hand it to a team led by Clarke and Rapuano. Not surprisingly, the new scheme was nearly identical to what Clarke and Embury had proposed in their own competition entry—a “great wall facing the Plaza, which may be suitably embellished with sculptural bas-relief.”30 The memorial itself was designed by Otto Eggers and Daniel Higgins, whom Clarke knew well from Washington. Eggers and Higgins were the architects of the Jefferson Memorial and the West Building of the National Gallery of Art, both begun by their late partner, John Russell Pope. Indeed, their Brooklyn memorial would have fit well on the National Mall—an austere classical sarcophagus, clad in limestone and framed by heroic figures representing military victory and family. These were among the final works of New York sculptor Charles Keck, a student of Augustus Saint-Gaudens whose commissions included a likeness of Huey Long in Baton Rouge, the Booker T. Washington Memorial at Tuskegee University, and—in New York—the Alfred E. Smith statue on the Lower East Side and the figurative pylons flanking Columbia University’s Broadway gate (he also designed a commemorative plaque to the USS Maine, cast from metal salvaged from the ship). It was Rapuano who really made the war memorial a distinguished piece of work. Drawing from his studies of Renaissance spatial design twenty years earlier at the American Academy in Rome, he created at Cadman Plaza one of New York City’s finest urban parks. He skillfully adapted a baroque spatial design trick to the trapezoidal site, splaying the sides of the green to manipulate the sense of perspective—creating an illusion of foreshortened or extended depth: from the south end of the space, the war memorial appears to loom just a bit, while the view from its steps toward Borough Hall seems ever so slightly more distant. Rapuano enclosed the space with a great grid of London plane trees, a move itself inspired by Italian precedent—the centuries-old boschetto of Oriental planes at the Villa Aldobrandini in Frascati, just outside Rome.

Perspective rendering of the Brooklyn War Memorial as built, 1949. The last sigh of monumental classicism in New York City, designed by the architects of the Jefferson Memorial and National Gallery of Art in Washington. Parks Photo Archive, New York City Department of Parks and Recreation.

Cadman Plaza and the Brooklyn War Memorial, c. 1958, with the newly planted boschetto of London plane trees. Parks Photo Archive, New York City Department of Parks and Recreation.

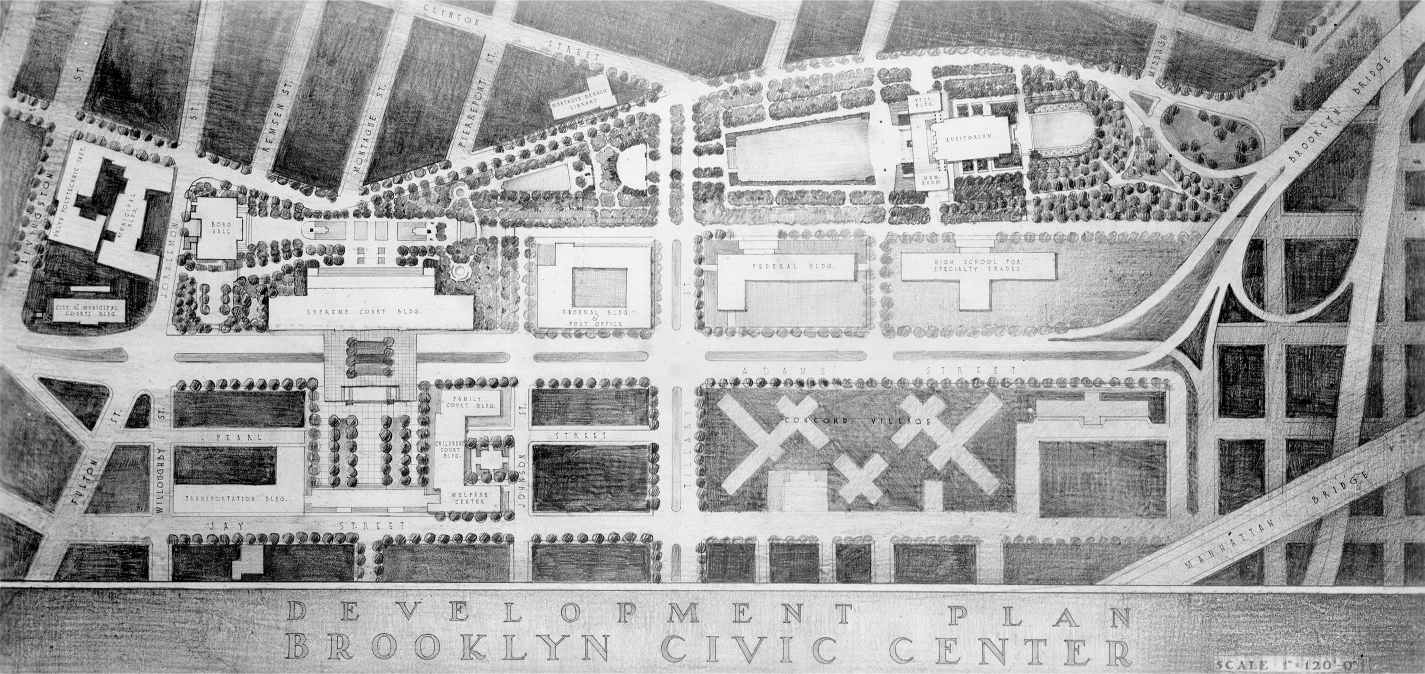

Clarke and Rapuano plan for Brooklyn Civic Center, 1951, showing federal courthouse, relocated Brooklyn High School for Specialty Trades, and the unbuilt Mies van der Rohe scheme for the Concord Village. Parks Photo Archive, New York City Department of Parks and Recreation.

Aerial perspective, Brooklyn Civic Center, 1952. The building adjacent to the post office is today the Theo-dore Roosevelt Federal Courthouse at 225 Cadman Plaza East. American Red Cross Building at center. Parks Photo Archive, New York City Department of Parks and Recreation.

With its imposing memorial and soaring plane trees, Cadman Plaza was a glorious centerpiece about which to arrange the Brooklyn Civic Center. Moses predicted that it would be “what the great cathedral and opera plazas are to European cities . . . as much the pride of Brooklyn as the Piazza San Marco is the pride of Venice and the Place de la Concorde the cynosure of Paris.”31 Unfortunately, nothing that came afterward matched its high standard. Nor could even this jewel of an open space compensate for the urban design failures of the larger subsequent project. What doomed the civic center was the postwar emphasis on isolated object buildings that ignored the street and did nothing to create the kind of cohesive fabric that even the clunkiest of the earlier City Beautiful schemes—with their block-defining perimeter buildings—took as essential to good urbanism. The civic center devolved into a loose assembly of dull modernist buildings, each more forgettable than the next, all orbiting Cadman Plaza like space junk about a star. The brochure produced for a 1952 exhibition on the Brooklyn Civic Center at Borough Hall unwittingly emphasized the project’s greatest failings, featuring on its cover an abstract expressionist plan drawing absent any context, in which the various civic center buildings appear like free-floating architectural flotsam. Of existing buildings in the vicinity, only Borough Hall, the Brooklyn Municipal Building, and Mifflin E. Bell’s glorious Romanesque Brooklyn General Post Office—nearly razed by Moses and today home to the US Bankruptcy Court—are shown. The principal civic center components included a federal complex at Tillary Street and Cadman Plaza East (today occupied by César Pelli’s superfortified US District Courthouse, opened in 2006) and—marooned on the north edge of Walt Whitman Park—a small headquarters for the Brooklyn chapter of the American Red Cross, designed by Eggers and Higgins and renovated after 9/11 as the city’s new crisis command center. To the east of this was Concord Village, a towers-in-the-park housing cooperative that was originally assigned to one of the pillars of modernism—Mies van de Rohe. On the west side of Cadman Plaza Park, Clarke and Rapuano had themselves recommended a set of well-defined perimeter buildings. But redevelopment of those blocks—filled with hundreds of century-old buildings including the shop in which Walt Whitman typeset Leaves of Grass—was not carried out until the mid-1960s. With superblock urbanism then all the rage, it’s no surprise that these blocks—the “fruit streets” between Henry Street and Cadman Plaza West—ended up like something torn from a Corbusian sketchbook.

Closer to Borough Hall was the one building everyone hoped would be the flagship of the civic center—the sprawling, $16 million Supreme Court Building. Replacing an earlier courthouse built during the Civil War at the corner of Adams and Joralemon streets, its prime site—fronting Columbus Park and visible for blocks all around—called for an architectural tour de force. And this is what the architects should have delivered; they were, after all, one of the city’s top firms—Shreve, Lamb & Harmon—designers of the Empire State Building. Instead they produced a banded gargantua that is neither modernist fish nor beaux arts fowl, whose bleak limestone façade is relieved by so few windows that it more closely resembles a prison than a hall of justice. It was on the other side of this building, between Adams and Jay streets, that the civic center nearly achieved a second note of grand spatial sensibility. Extending from the Supreme Court Building’s rear façade to Jay Street was to be a spacious formal plaza with a parking garage below, flanked to the north by the Welfare Building (demolished) and the Domestic Relations Court at 283 Adams Street (now a public school) and to the south by the civic center’s best modernist work, the Board of Transportation Building—“well conceived, straightforward in design,” wrote Mumford, “the very model of an efficient office building” (today home to New York University’s Center for Urban Science and Progress).32 Reminiscent of Lincoln Center, this pedestrian-friendly composition was envisioned by two Department of Public Works architects—A. Gordon Lorimer and Victor Chiljean. Mumford cheered it as an example of the kinds of pedestrian gathering places—“human catchment basins,” as he called them—that would bring vitality and life to the civic center. By placing Adams Street in an underpass beneath the plaza, their plan fused the core of the civic center to Myrtle Avenue and the populous neighborhoods east of downtown. This was an essential move, for Adams Street had been widened from 60 to 160 feet and was now carrying all motor traffic to and from the Brooklyn Bridge. The once-ordinary street was now a busy ten-lane arterial barrier that threatened to isolate the civic center from its context. Unfortunately, the Adams Street underpass was eliminated, thus piercing the civic center “in defiance,” noted Mumford, “of every canon of sound civic design” and nullifying “most of the aesthetic and social qualities this center might have possessed.” The underground garage was built, but with a park on its roof rather than a plaza. Never well used, the space was eliminated altogether in 1996 for the Renaissance Plaza redevelopment, which erected an office tower and hotel on the site—the first in the borough since the 1930s (today the New York Marriott at the Brooklyn Bridge).33

Lorimer and Chiljean plan for Brooklyn Supreme Court plaza, c. 1953. Local History Research Collection, Brooklyn College Library Archives and Special Collections.

American Red Cross Building, Eggers & Higgins, architects, 1952. Extensively altered, the structure is today the Emergency Operations Center of the New York City Office of Emergency Management at 165 Cadman Plaza East. New York City Department of Parks and Recreation.

The Brooklyn Civic Center was so vast in scope, so hydra-headed in its administrative and bureaucratic complexity that it seemed to generate political weather all its own. It dragged on for three decades and four mayoral administrations, outlasting not only Moses but nearly all of its most vocal proponents, ultimately becoming a symbol of all the promise and failure of the postwar welfare state. In the end, it yielded not a masterpiece of civic urbanism but a sad Orwellian cluster of unloved institutional buildings, enframed by superblock housing estates and entangled by expressway ramps. In a tragically poetic twist of fate, the Mosaic juggernaut consumed even the extravagant old nest of the Brooklyn Eagle—a building designed by George L. Morse and once lauded as “one of America’s most perfect newspaper establishments,” the aerie from which Cleveland Rodgers had so tirelessly called for the comprehensive renewal of downtown Brooklyn, beckoning the very winds of creative destruction that would sweep it all away.34

End of an era: the Brooklyn Eagle block falls to the wrecking ball, 1955. Photograph by William M. Schouten. Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn Collection.