HISTORY

HISTORY

GLOSSARY

alpha acids Resinous components of hops that, during the boiling stage in the brewing process, add bitterness to balance the natural sweetness of the beer. The percentage of alpha acids in different varieties of hops is a measure of the bittering potential of the hop variety, or batch.

Bohemia A historic region of central Europe, now forming the western part of the Czech Republic.

cask ale Ale that has been matured and conditioned in a cask without having been pasteurized and with little or no filtration. As live yeast remains, the beer continues to ferment slowly, providing a light, natural carbonation when the beer is served. It is not dispensed using carbon dioxide (CO2), as is the case with other draught beer, but drawn through pipes running from pub cellar to bar, by means of a piston pump system. It may also be served using a tap inserted directly into the cask. Often also called real ale.

cold fermentation Fermentation using yeast adapted to working at temperatures of around 7–13°C (45–55°F), compared to 17–22°C (62–72°F) for warm fermentation. Cold fermentation yeasts tend to sink, so the process is often called bottom fermentation. Warm fermentation yeasts tend to produce a foamy cap of yeast, hence ‘top fermentation’. Cold-fermented beers (generally lagers) are often less fruitily aromatic compared to warm-fermented beers.

craft brewery Essentially, an independent brewery, typically a small one that is wholly or largely independently owned, and often (but not always or exclusively) producing beer styles influenced by modern American breweries. In the USA, the Brewers Association defines a craft brewer as ‘small, independent and traditional’. It stipulates maximum levels of annual production and no more than 25% ownership or control by an individual or business that is not itself a craft brewer. There is no formal definition outside the USA and this has been a source of contention, especially in the UK.

enzyme A type of naturally occurring protein that acts as a catalyst, driving and accelerating chemical reactions. In beer making, Enzymes present in barley are activated in the mashing process, where, in the presence of water at about 67°C (153°F), they convert unfermentable starches into fermentable sugars.

hybrid beer A beer made with a combination of fermentation methods and/or ingredients, such as used for both lagers and ale types, showing characteristics of more than one style of beer.

Industrial Revolution The rapid development of industry that began in Britain in the late eighteenth century, brought about by the introduction of machinery.

IPA Stands for India Pale Ale; a stronger version of the pale ale style.

keg beer Beer dispensed from a keg, characterized by using carbon dioxide or nitrogen pressure to force the beer out of its container. Typically, keg beers are served cooler and are more carbonated (fizzy) than cask beer. Keg beer is far more common than cask beer.

pump clip A small removable label, usually of plastic, wood or metal, attached to a beer-dispensing tap in a pub or bar; it identifies the beer being served, and usually the brewery. Pump clips are an important part of the brand identity. The name, in the UK at least, originates from its use on the handpump handles used to dispense cask ale.

Trappist Denoting beers brewed at a Trappist monastery recognized by the International Trappist Association. Trappist beers are often strong (7–10% ABV) and usually conform to styles originating in Belgium. Beers brewed in similar styles but not at one of these monasteries are known as Abbey-style beers.

THE ORIGINS OF BEER

the 30-second beer

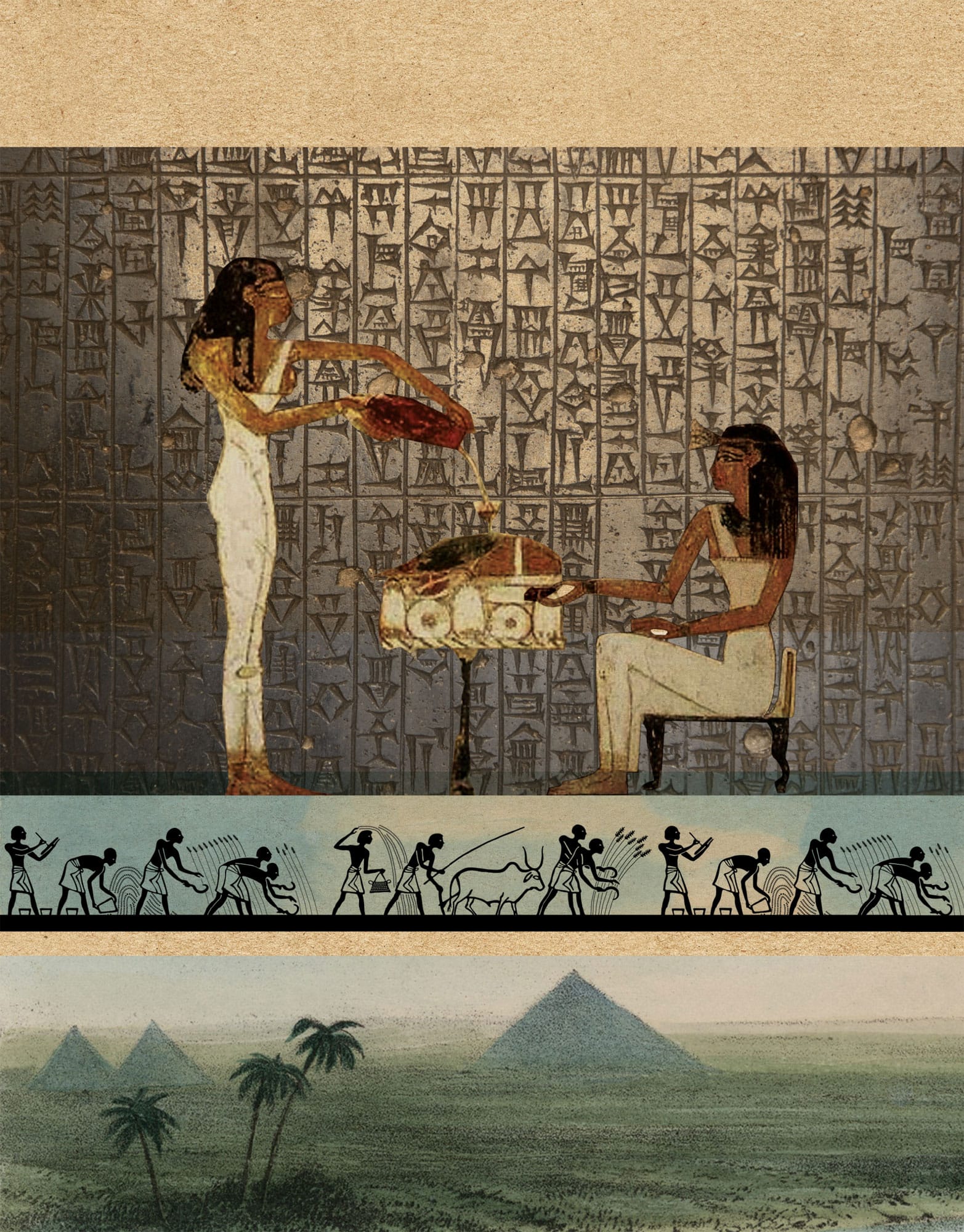

Historians can’t agree what came first: civilization or beer. Some say that nomadic tribes settled down specifically so they could set up agrarian systems to grow large quantities of grain and thus brew seriously. Others are not so sure. What they do agree on is that the malting process might have been triggered by wild grain being left out in the rain. Collected up and heated to make bread, the grain’s starches would have begun the conversion to sugar. Add in a bit more rain plus wild yeasts, and fermentation could have taken place. Molecular archaeology traces beer back to the ancient Sumerians, over 5,000 years ago. Located in what is now Iraq, Sumeria is often called the cradle of civilization, being where nomads first put down roots. Beer swiftly became embedded into the culture, as it did with the Babylonian and Egyptian empires that followed. With their preference for wine, the Greeks and Romans were less enthused. As Catholicism took hold in much of Europe, the monasteries arrived, embracing brewing with fervour. From the start, beer’s celebratory potential was well recognized along with its nutritional value. Alongside baking bread, brewing became the responsibility of women, which it remained until the Middle Ages. While the grains used might have varied, before 1000 CE the flavour came from herbs rather than hops.

3-SECOND TASTER

First ‘discovered’ by the Sumerians over 5,000 years ago and for millennia often more hygienic to drink than water, beer’s pleasurable and nutritious properties swiftly made it popular for all.

3-MINUTE BREW

The first beer laws arrived in Babylonian times. The famous Hammurabi Code not only defined 20 varieties of beer, but it also specified ration laws based on social standing and laid down purity and price regulations. From peasants to pharaohs, Egyptians embraced beer throughout society. Great grain stores were established and large breweries were built. Workers were paid with beer, taxes on beer were brought in and records speak of the ‘beer of eternity’ and ‘garnished beer’.

RELATED ENTRIES

See also

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHY

DR PATRICK E. MCGOVERN

1944–

Known as ‘the Beer Archaeologist’, Dr McGovern is the Scientific Director of the Biomolecular Archaeology Project for Cuisine, Fermented Beverages and Health at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; he recreated award-winning ancient beers with Sam Calagione at Dogfish Head Brewery, Delaware, USA

30-SECOND TEXT

Susanna Forbes

For both its pleasurable and nutritional value, beer became an integral part of culture in the Sumerian, Babylonian and Egyptian empires.

WOMEN & BEER

the 30-second beer

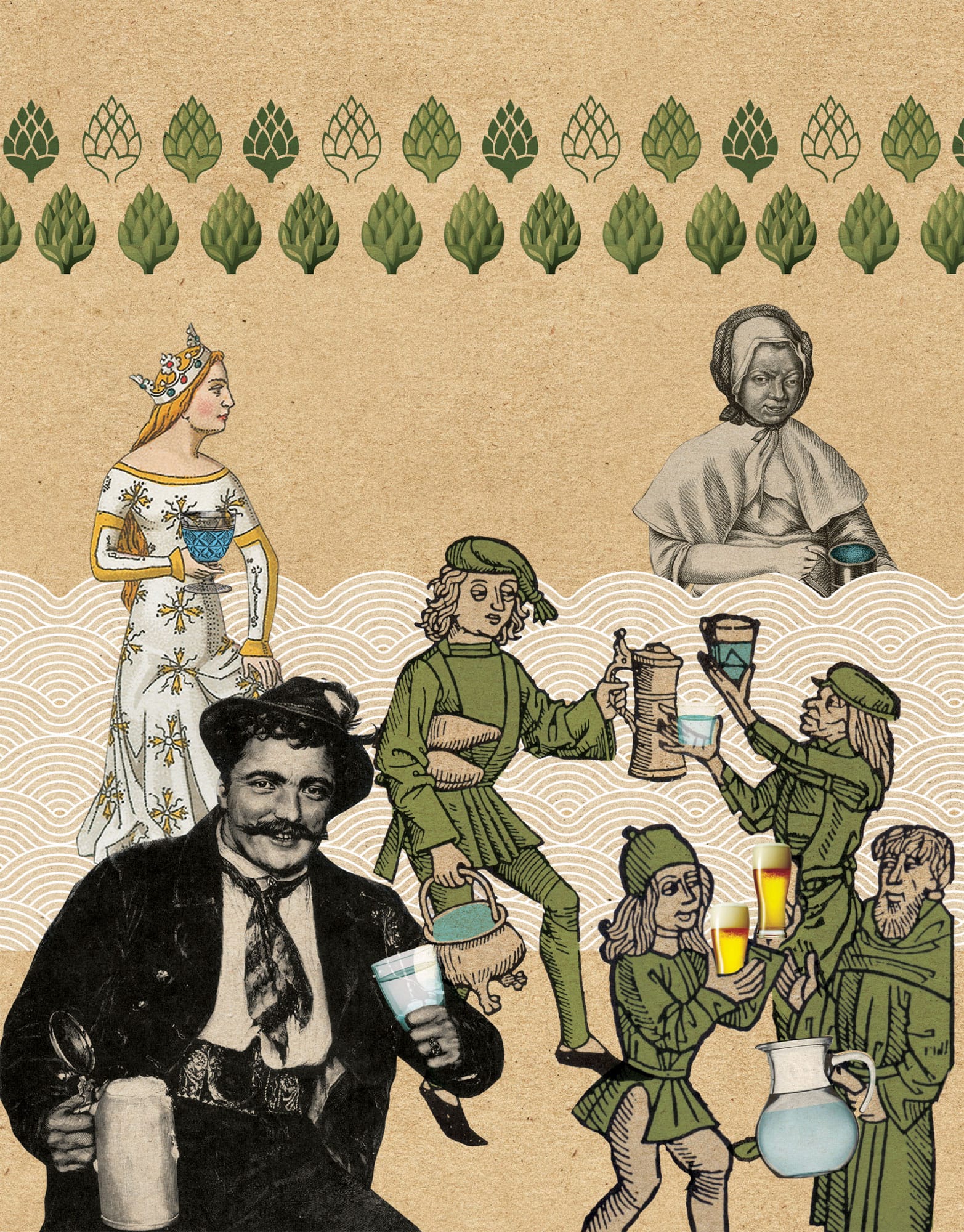

In the earliest brewing civilizations, Sumeria, Babylon and Ancient Egypt, beer was made mostly by women. Fast forward a few thousand years and evidence from medieval England tells a similar story: brewing was women’s work. They produced beer in the manner of a cottage industry, selling it from their homes or hawking it in the streets, but they were also brewing on a more commercial scale. Yet, in parallel with other historical examples of sex discrimination, as brewing became more profitable and industrialized, women were pushed out. There’s also a correlation between women being expected to inhabit only the private space of the home, while men occupied public space – including the public house. It may not be the most important element in the battle for equality, but beer is a feminist issue. Not only was women’s freedom to produce it curtailed, but public attitudes dictated they ought not to drink it either. Marketing, from advertising campaigns through to sexist beer names with pump clips to match, has done its best to promote the idea that beer is a man’s drink. This is daft considering women make up half the population. Happily things are coming full circle. Growing numbers of women brewers, a glut of organizations representing women in the beer industry and increased interest among female drinkers show beer is a drink for all.

3-SECOND TASTER

Women were the first brewers and publicans – only in more recent times has beer been presented as being for men.

3-MINUTE BREW

In the 1970s Irish feminists staged a pub-based protest. Around 30 women each ordered a brandy, which they were served. They then asked for a pint of Guinness but were refused. They drank the brandy and left without paying. It was apparently legal to refuse to pay if there was an error with your order. Not allowing a woman her beer was clearly a grave error.

RELATED ENTRY

See also

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

HILDEGARD VON BINGEN

1098–1179

Abbess of a Benedictine convent. She brewed beer and was probably the first person to write about hops in a scientific way. She also wrote about barley

SARA BARTON

1965–

Founder and head brewer of Brewster’s Brewery, Lincolnshire. As well as naming her brewery after the term for female brewers, Sara’s brewing ethos is to make beer appealing to all. She also brews a range of beers named after famous women

30-SECOND TEXT

Sophie Atherton

Women’s relationship with beer dates back thousands of years.

SAFER THAN WATER

the 30-second beer

Beer has many attributes that make it appealing, but some of the most surprising are its health benefits. If you were living somewhere with unreliable water quality, beer could actually be safer to drink than water, for several reasons. First, alcohol itself is anti-bacterial – which is why it’s used for swabbing in medicine. Second, the alpha acids in hops are also anti-bacterial, which allows beer to stay clean of harmful micro-organisms even at low alcohol strengths. And third, beer is boiled during its production, sterilizing the water in the brew. Because of all this, it’s commonly asserted among brewing historians that beer was widely drunk because it was a safer alternative to drinking water. But the generality of this assertion has been questioned. Throughout history, supplies of drinkable water were not difficult for most people to obtain (outside of urban slums). Also, sterilization through boiling has long been understood – why not simply boil the water rather than go to the expense of brewing? The answer was likely the same then as it is now: people preferred beer because of its flavour, drinkability and ‘buzz’. When life was so much harder, these attributes were even more important than they are today.

3-SECOND TASTER

For most of our history beer has been safer to drink than water, but that’s not necessarily the main reason our ancestors drank so much of it.

3-MINUTE BREW

Beer doesn’t necessarily have to be boiled during production. It takes much more fuel and energy to boil water than it does to get to the warm temperature required for the enzymes in the malt to break down sugar ready for fermentation. It seems boiling only entered the picture when hops became the dominant flavouring in beer, around the fifteenth century – further undermining the theory that beer was an essential alternative to water.

RELATED ENTRIES

See also

30-SECOND TEXT

Pete Brown

Because the brewing process includes boiling water, and – later – because of the antiseptic properties of hops, beer was considered a hygienic drink.

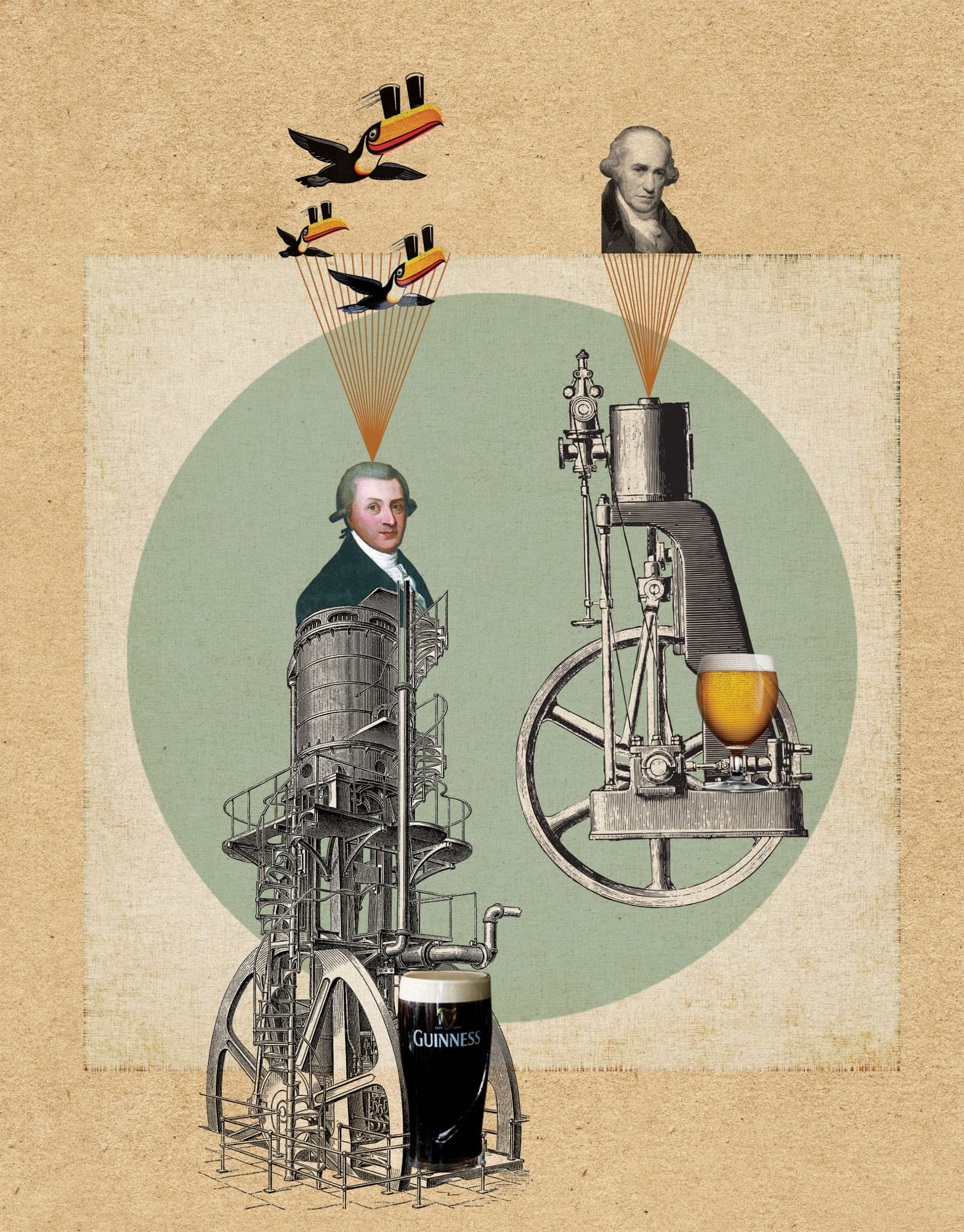

BEER & THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

the 30-second beer

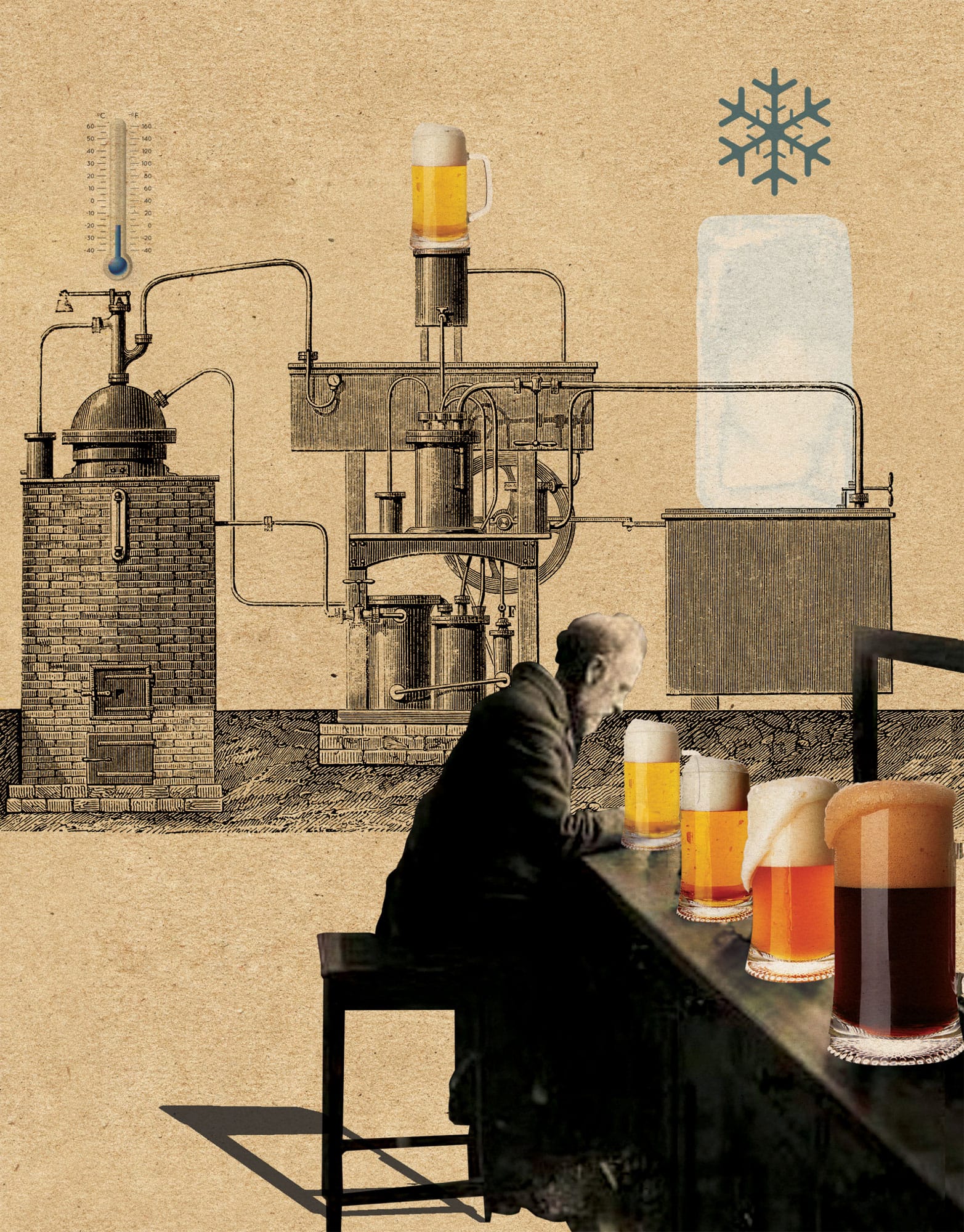

It’s hard to believe in an age of pale ales and golden lagers, but until the Industrial Revolution all beers were brown. Malt was kilned or heated over smoky wood fires and the result was brown malt. When coke replaced wood it was possible to produce much paler malt with a higher level of enzymes in the grain that turn starch into fermentable sugar. The result was pale ale and stronger India Pale Ale (IPA) in England. European brewers rushed to England to see how pale ale was made then returned home to fashion pale lager. The major breakthrough was in Bohemia – now the Czech Republic – where the first golden lager was brewed in Pilsen. It was called Pilsner Urquell or Original Pilsner and it took the world by storm. Brewing for centuries had been seasonal and couldn’t take place in summer as high temperatures turned beer sour. Production was transformed in the nineteenth century by ice-making machines and refrigeration that allowed beer to be stored in cool cellars. In the Carlsberg laboratories in Copenhagen, a scientist called Emil Hansen isolated a pure strain of ‘bottom-fermenting’ yeast that enabled beer to be brewed that was both clear and free from infection. Carlsberg allowed other brewers to use its yeast and lager beer went on to conquer the world.

3-SECOND TASTER

Before the technological advances of the Industrial Revolution, all beer was dark and summer brewing turned beer sour.

3-MINUTE BREW

You can enjoy dark lagers in Germany and the Czech Republic but most lager beers today are pale gold and account for around 90% of all beer brewed worldwide. In spite of the popularity of lager, brewers in Britain and Ireland remained faithful to ale, including stout. Ale is made with a different type of ‘top-fermenting’ yeast that creates rich, fruity aromas and flavours. Today, with the popularity of IPA, ale is enjoying greater appreciation.

RELATED ENTRIES

See also

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHY

MARTIN STELZER

1815–94

Founder of the Burghers’ Brewery in Pilsen; he recruited brewer Josef Groll who would go on to become the father of modern lager

30-SECOND TEXT

Roger Protz

The technical progress brought about by the Industrial Revolution is responsible for the golden beers we know today.

ORIGINS OF MODERN ALES

the 30-second beer

The Industrial Revolution wrought two changes to brewing. First, it introduced new technologies that allowed brewers a much greater degree of quality control over their beers. Second, it allowed those who invested in brewing to benefit from economies of scale: the more beer they brewed, the cheaper it became. Brewing changed from an artisanal to an industrial activity, and that dramatically affected the style of beer brewed. Britain – the first industrialized country – was the first to experience this brewing revolution, and the first to develop new, industrial styles. The first industrial beer was porter, which was aged in wooden vats. The bigger the vats, the cheaper and more consistent the beer. Porter became hugely popular in London, brewed by new, industrial brewers such as Whitbread and Barclay Perkins. Arthur Guinness took the recipe home with him to Dublin, where his son, Arthur II, created a richer, ‘extra stout’ version that eventually became known simply as ‘stout’. Coke smelting allowed greater control over malting barley, which allowed greater consistency in pale malt. Pale ales grew in popularity, particularly when exported to India, where they were perfect for the climate. By the 1820s, ‘India Pale Ales’, along with curry and silks, were the height of fashion in London, and pale ales began to rival and eventually overtake porter in popularity.

3-SECOND TASTER

Our most legendary ale styles have their roots in a similar time and place: London, in the heat of the Industrial Revolution, where beer met science and technology for the first time.

3-MINUTE BREW

Beer styles aren’t created – they evolve. That’s why there are no accurate dates or places for when they were first brewed, only times when they became commonly referred to by these names. Strong pales ales were being sold in India for at least a hundred years before the earliest known use of the term ‘India Pale Ale’ in press advertisements. IPA and porter are still evolving today, if anything, faster than ever.

RELATED ENTRIES

See also

BEER & THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHY

SAMUEL WHITBREAD

1720–96

Brewer and politician whose Chiswell Street brewery pioneered many modern industrial brewing techniques

30-SECOND TEXT

Pete Brown

The changes brought about by the Industrial Revolution dramatically changed the beer world.

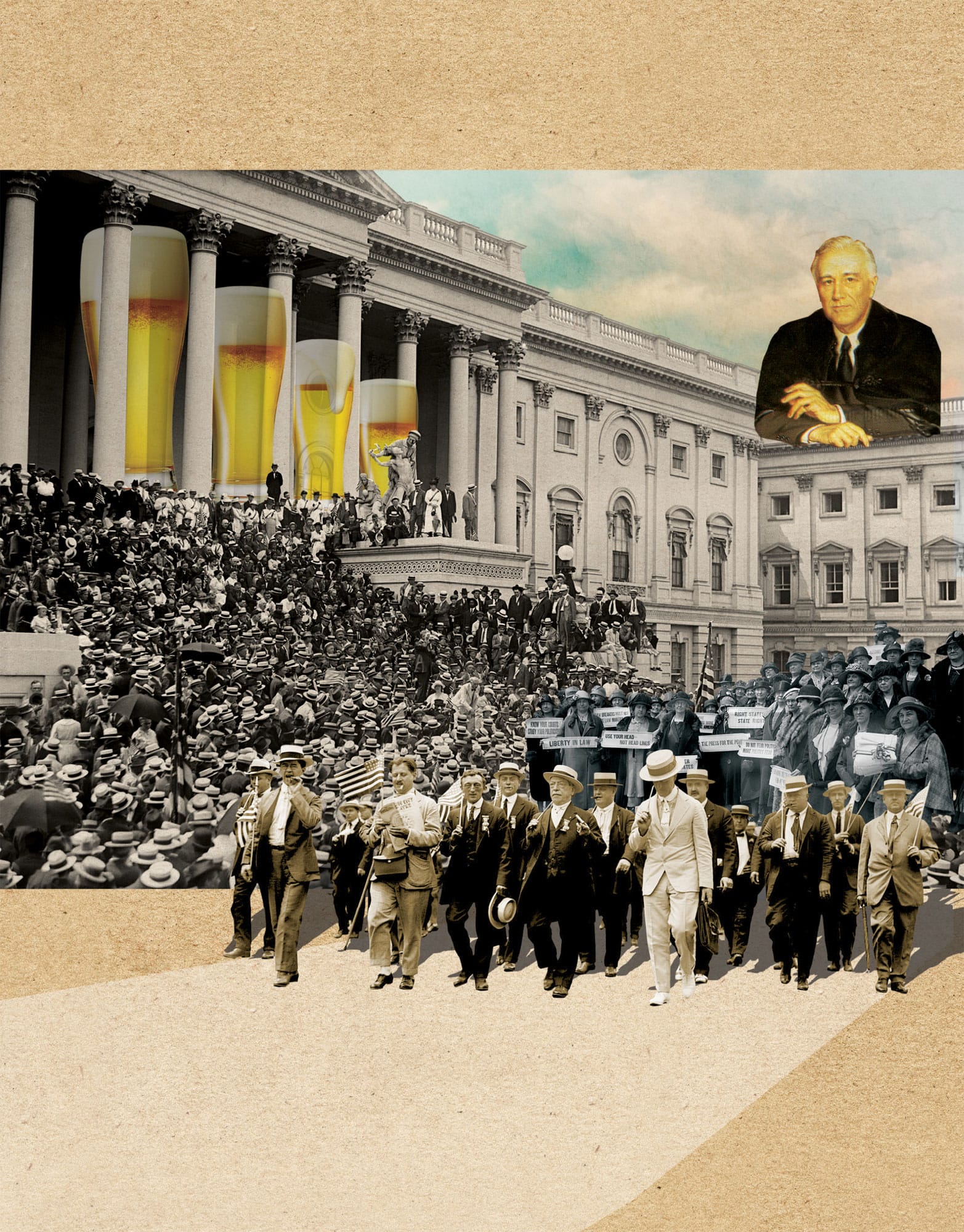

BEER IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

the 30-second beer

The twentieth century began badly for beer. The deprivations of the First World War saw restrictions on malt supply, leading to weaker beers and the decline of stronger styles such as barley wines, old ales and strong stouts. In the USA, Prohibition’s ban on the production and sale of alcohol led to the destruction of the American brewing industry. Elsewhere, mergers and acquisitions meant widescale rationalization, with hundreds of breweries closing. As brewing companies became bigger and more powerful, the way in which beer was produced and marketed also changed. In the UK, pasteurized, filtered and pressurized keg beer was promoted in place of cask ale, a move that led to the consumer fighting back, with the foundation of the Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA) to push for the revival of traditional beer. Its success, in turn, was partly the inspiration for a new generation of craft breweries in the USA; their adventure and expertise went on to change the face of beer production internationally. In particular, their use of boldly flavoured American hops encouraged others to bring the hop more to the fore and encouraged hop breeders to deliver new varieties. Along with the rediscovery of forgotten beer styles and the creation of new hybrid styles, this has given beer new status as a connoisseur drink and resulted in thousands of new breweries opening around the world.

3-SECOND TASTER

After an initial severe decline, beer ended the twentieth century in good shape, ready to take the world by storm in the new millennium.

3-MINUTE BREW

The Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA) was founded in 1971 by four friends appalled by the deteriorating quality of beer in the UK. Big breweries were removing traditional cask ales from pubs and replacing them with more profitable, but less flavoursome, keg beers. The four decided to take a stand and soon found there were thousands of like-minded people ready to join them. A powerful consumer movement was born.

RELATED ENTRIES

See also

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT

1882–1945

32nd President of the USA, who repealed Prohibition, reviving the US economy, reducing crime and bringing beer back to the people

JIMMY CARTER

1924–

39th President of the USA, who legalized the right to homebrew in 1978, a move that opened up the sector, providing a catalyst for the birth of craft brewing

30-SECOND TEXT

Jeff Evans

It was a challenging period for beer, but also the time when the seeds of future revolutions were sown.