BREWING

BREWING

GLOSSARY

alpha acids Resinous components of hops that, during the boiling stage in the brewing process, add bitterness to balance the natural sweetness of the beer.

bottle conditioned Beer that continues to ferment in its bottle owing to the presence of yeast. Must be stored upright and, unless a yeasty or hazy style, poured carefully so as not to disturb the sediment.

brewpub A pub or bar containing brewing equipment of sufficient capacity to make beer for sale on the premises.

carboy A glass or plastic cylindrical container often used in homebrewing for fermenting beer. Typical capacity is 5 imperial gallons (22.7 litres).

enzyme A type of naturally occurring protein that acts as a catalyst, driving and accelerating chemical reactions. Enzymes present in barley are activated in the mashing process, where, in the presence of water at about 67°C (153°F), they convert unfermentable starches into fermentable sugars.

ester A chemical compound produced in beer as a by-product of fermentation, especially of ales. In moderate quantities esters can be desirable because of the aromas they impart.

farmhouse beer A family of ales originally from northern France and parts of Belgium, brewed as seasonal beers in farmhouses in the cooler months then stored to provide refreshment for farm workers in the summer.

Gose A wheat beer flavoured with coriander and brewed using salt or salty water. Originating from the Leipzig area of Germany, its popularity has increased in recent years.

gruit A blend of hedgerow herbs used to flavour and season ales before the use of hops became widespread.

isinglass A substance extracted from the swim bladders of fish, it is used to speed up the clarification (fining) of beer, by causing yeast particles to clump together and settle at the bottom of the cask.

keeping quality An approximate measure of how well a beer can remain fresh and palatable. Beer can rapidly acquire undesirable flavours when subjected to light and temperatures above about 11°C (52°F).

Lambic Acidic-tasting (sour) wheat beers from the Brussels area of Belgium, fermented by wild yeasts and bacteria allowed to settle on the wort cooling in open vessels in a process known as spontaneous fermentation.

lupulin Resinous powder from the lupulin glands of a hop cone that contains the alpha acids and other flavour compounds used in brewing.

Reinheitsgebot German for ‘purity decree’, commonly known as the beer purity law. The original decree, declared in Bavaria in 1516, stated that beer could only be made with barley, hops and water. It was thought necessary to guard against adulteration of beer with inferior ingredients. Yeast was added to the list after its discovery.

single-strain yeast Yeast used for fermentation that consists of just one variety, as opposed to a mixture of strains.

terroir French for territory. A term borrowed from the wine industry to denote the properties of beer or hops that are specific to the geographical, climate and other physical characteristics of the area of production or growth.

wild yeast Yeast other than brewer’s yeast present in the brewery environment. Produces beers with characteristics often reported as barnyard aromas, or as giving goaty or cheesy flavours.

wort The sugary liquid that results from the mashing process, in which, in the simplest case, the milled grains are soaked in water at about 67°C (153°F) for 90 minutes or so and then drained.

Yorkshire square A fermenting vessel invented in Yorkshire, in north-east England, and still in use in some traditional ale breweries. Originally consisting of a square base and a lower and upper deck, which helps separate the yeast from the beer. Said to produce dry, yet fruity beers.

HOW BEER IS MADE

the 30-second beer

Any alcoholic drink is made by extracting fermentable sugar from fruit, grain or other substances such as honey, and giving yeast the right conditions to ferment that sugar into alcohol. For beer, the main grain used is barley, although any cereal can be used – wheat, maize and rice are also popular. Malted barley is steeped in hot water, which prompts enzymes in the grain to break down starch into fermentable sugars. These sugars, along with flavour compounds and other attributes, are rinsed out from the grain husks and dissolved into the water to create ‘wort’. Hops are then added to the filtered wort and it’s brought to the boil. This causes ‘isomerization’, a reaction in the hops’ alpha acids that gives beer its bitterness as well as some anti-bacterial protection. More hops are added at the end of the boil so their essential oils aren’t boiled off, and these add aroma and flavour that balance and complement the sugars and flavours of the malted barley. The hopped wort is then allowed to cool, before yeast is added. Over the next few days, yeast ferments most of the sugar to alcohol as well as adding its own flavour contribution. Other flavourings and adjuncts – such as herbs, fruit and spices – are sometimes used, but this is the basic template for beer.

3-SECOND TASTER

Beer is made from malted barley, water, hops and yeast, in a multi-stage process that can seem confusing, but has a beautifully simple logic to it.

3-MINUTE BREW

Each stage of the brewing process usually takes place in large, specialized vessels: water and malted barley are combined in the ‘mash tun’, and the resulting ‘wort’ is then run off into the ‘kettle’ or ‘copper’. The hopped wort runs through a heat exchanger and then into fermentation vessels that are designed to keep yeast happy. But the basic process can be done on a stove top with a couple of large saucepans.

RELATED ENTRIES

See also

30-SECOND TEXT

Pete Brown

Beer can be made from just four ingredients: water, barley, hops and yeast, using appropriate vessels for each stage of the brewing process.

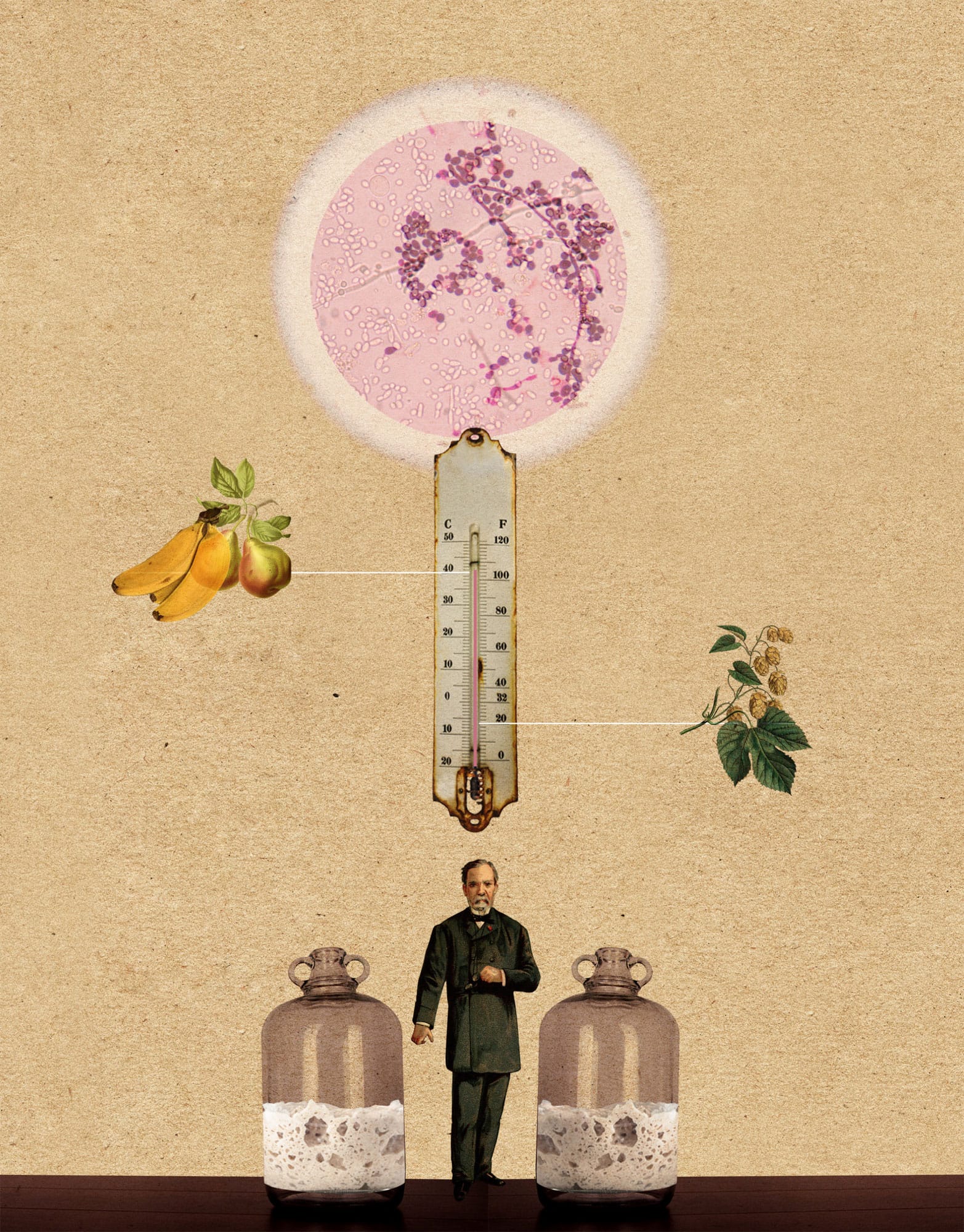

FERMENTATION

the 30-second beer

Humankind has harnessed fermentation’s beneficial properties for millennia, most notably in food production – bread, sauerkraut and cheese – and drinks making – beer, cider and wine. Sugars get gobbled up by the microbe responsible, be it yeast or bacteria, and this transforms both ingredients and flavours. Whether carboy or cask, Yorkshire square or conical fermenter, byproducts of yeast in brewing include carbon dioxide, heat and, of course, our friend alcohol. Yeasts are hungry little fungi, but they are picky about their environment: the liquid must be the right temperature, not too acidic and with just the right levels of salts and nutrients. While there are dozens of yeasts commercially available, historically brewers tend to opt for a few species: the warmth-loving Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which creates ales, and a couple of cooler kids, including S. pastorianus and carlsbergensis, responsible for lagers. There’s also Brettanomyces, Brett for short, renowned for the edgy, often sour flavours it creates. Brewers can also leave it to nature, as the Belgians have done for centuries with their Lambic beers. Fermentation lasts anything from a week to several months. Once this phase has finished, there’s the option of a secondary fermentation, often called conditioning, with or without additional yeasts and priming sugar.

3-SECOND TASTER

Fermentation converts sugar into alcohol, and with yeast in the driving seat it converts cooled wort into fresh beer, transforming flavours and creating a vast array of different beer styles.

3-MINUTE BREW

So what affects beer’s flavour? Of course, the original wort. Then the yeast. Yeast breaks down simple sugars before tackling more complex ones. Along the way, it creates a range of flavour compounds, including esters, glycerol, phenols and so-called higher alcohols – there are over 40 of these in beer alone. Temperature is key: higher temperatures favour fruitier esters while cooler ones allow the hop fragrance to shine. Finally, adding dry hops during fermentation adds a whole new dimension.

RELATED ENTRIES

See also

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

LOUIS PASTEUR

1822–95

As well as discovering how heat treatment could prevent spoilage, Pasteur convinced the scientific establishment that the cause of fermentation was yeast’s action on sugars

DR JOHN EWALD SIEBEL

1845–1919

Brewing and educational pioneer who set up what became the Siebel Institute of Technology in 1872 in Chicago, designed ‘to promote the progress of the industries based on fermentation’

30-SECOND TEXT

Susanna Forbes

Higher temperatures during fermentation promote fruitier esters.

CONDITIONING & MATURATION

the 30-second beer

Beer is too good to rush. It needs care and attention to present it in the finest condition and this varies according to style. Ale is made faster than lager – but still needs time in the brewery before packaging. After fermentation, this ‘green beer’ needs to rest for several days in conditioning tanks while the beer purges itself of rough flavours that would leave yeasty and vegetable-like tastes. Beer may be treated differently after fermentation depending on how it will be packaged. Keg beer is often filtered and pasteurized to remove yeast and protein and is served using CO2 pressure when it reaches pub or bar. But many modern craft keg brewers avoid these methods, which is why their beers are often served slightly cloudy. Pasteurization can leave a ‘cardboard-like’ flavour. Cask-conditioned beer (real ale) leaves the brewery unfinished. It undergoes secondary fermentation in the pub cellar, taking several days for the yeast to settle before it’s ready to serve. Natural carbonation takes place to give the beer its sparkle, but real ale has to be served within two or three days or it will go flat. Bottled beer is usually filtered, but bottle-conditioned versions contain live yeast and may age over time, like wine. Many modern global lager brands are produced as quickly as ale but traditional lagers get several months conditioning at temperatures close to freezing.

3-SECOND TASTER

Beer needs time and care to reach perfection; even after fermentation it must be allowed to condition and mature – rushing it risks compromising quality and flavour.

3-MINUTE BREW

Conditioning and maturation relate to visual presentation but consumer attitudes are changing, and cloudy beer is becoming acceptable. Crystal-clear beers can be achieved by using ‘finings’ or isinglass, made from swim bladders of fish, which doesn’t find favour with vegetarians and vegans. Many brewers have turned to alternatives, like Irish moss – a type of seaweed – or silica gel. The brewing faculty at Nottingham University in the UK is analysing hops to see if they can be used as a clearing agent.

RELATED ENTRIES

See also

30-SECOND TEXT

Roger Protz

Beer needs to take its time, even after fermentation, before it is ready for you to drink.

HOPS

the 30-second beer

Spice, pine, herbs, citrus, peaches, flowers – just some of the flavours and aromas given to beer by hops. And it’s all down to the rosebud-sized hop cone. Lupulin glands cling on the underside of tightly woven hop petals containing sticky, pollen-like grains packed with bittering alpha acids and fragrant essential oils. Part of the cannabis family, hops grow best between 35° and 55° latitude, preferring lengthy sunlight hours and well-drained soils. Every spring, the hop bines wind up the web of poles and wires, growing up to 10cm (4in) a day. Come autumn, skilled harvesters cut down the bines, separating off the cones before drying and packing them into hop bales weighing up to 65kg (143lb). Just like grapes and wine, hops have terroir. English bitter is synonymous with the earthy, spicy, grassy notes of Fuggles and Goldings; the herbal, floral fragrance of Saaz signifies Czech pilsner, while the bold citrus and pine flavours from Pacific Northwest hops suggest American pale ale. Globally, the acreage of hops planted is gently rising, with production figures fluctuating according to harvest conditions. The USA recently overtook Germany as the world’s largest hop-growing region. While research used to focus on disease-resistant strains, now, thanks to the craft beer revolution, new aroma hops share the limelight.

3-SECOND TASTER

Hops play a three-fold role in brewing, most importantly adding bitterness but also preserving the beer, and infusing it with a rich tapestry of flavour and fragrance.

3-MINUTE BREW

Hops originated in China over a million years ago, with three species emerging. Two headed east while the other spread west to Europe. Central Europe was the first to realize hops’ preservative potential in brewing. Hop gardens were first described in the eighth century in Hallertau, Germany, with the first recorded use in brewing being 822 CE, in Picardie, France. While Britain was slow to embrace hops, it soon became linked with several key beer styles, including bitter and IPA.

RELATED ENTRIES

See also

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

REGINALD SCOTT

1538–99

The first to write in depth on the English hop industry, his book A Perfite Platform of a Hoppe Garden (1576), covers every stage of cultivation

DR PETER DARBY

1956–

Developed numerous hops, including First Gold, Pilgrim and aphid-resistant Boadicea; revolutionized hop growing with breeding of hedge hop varieties

30-SECOND TEXT

Susanna Forbes

For such tiny little ‘flowers’, hop cones can imbue beer with an incredible array of flavours, over and above their preservative and bittering properties.

MALT

the 30-second beer

Alcohol is made when yeast eats sugar. Broadly speaking, ferment fruit and you get wine; ferment grain and you get beer. But before you can brew, you need to malt the grain, basically tricking it into activating enzymes that will convert its starch into fermentable sugar. At the end of malting, the grain is dried in a kiln. Lightly kiln it and you get pale malt. Apply more heat and you get darker malts, but go too dark and you kill the enzymes and the grain won’t ferment. But you do get lots of luscious flavour: crystal malt is chewy and granola-like, and dark malts have hints of berry fruit, coffee, chocolate or tobacco. Most beers consist of 90% pale malt to provide the sugar that ferments to alcohol, and the remaining mix determines whether you get pale and crisp or darker, chewier beers. You can make beer with other grains such as wheat, oats or spelt, but barley is king. And while the malting process gives beer its style and character, the strain of barley that goes into malting makes a big difference, too. Barley varieties are carefully bred for their character and yield. Maris Otter, first bred in 1964, is considered to be peerless by many ale brewers for its superb flavour.

3-SECOND TASTER

Beer’s core ingredient is malted barley – the malting process is vital for getting fermentable sugar, but it also creates a rainbow of different flavours.

3-MINUTE BREW

Technically, beer is the result of fermenting any grain. Every civilization in history was founded on achieving a supply of one of the noble grains known as cereals. Coincidence? I don’t think so. Humans figured out how to malt barley for brewing roughly 10,000 years ago, by pure trial and error, with no knowledge of enzymes or how the process activated them. That’s determination for you.

RELATED ENTRIES

See also

BEER & THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHY

EDWARD SLOPER BEAVEN

1857–1941

Pioneer of modern barley breeding, Beaven’s work at Warminster maltings in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century led to the first commercial barley varieties and essentially gave birth to modern malt

30-SECOND TEXT

Pete Brown

The sugars that are needed to make the alcohol in beer are often provided by malted barley, although other cereals are sometimes used.

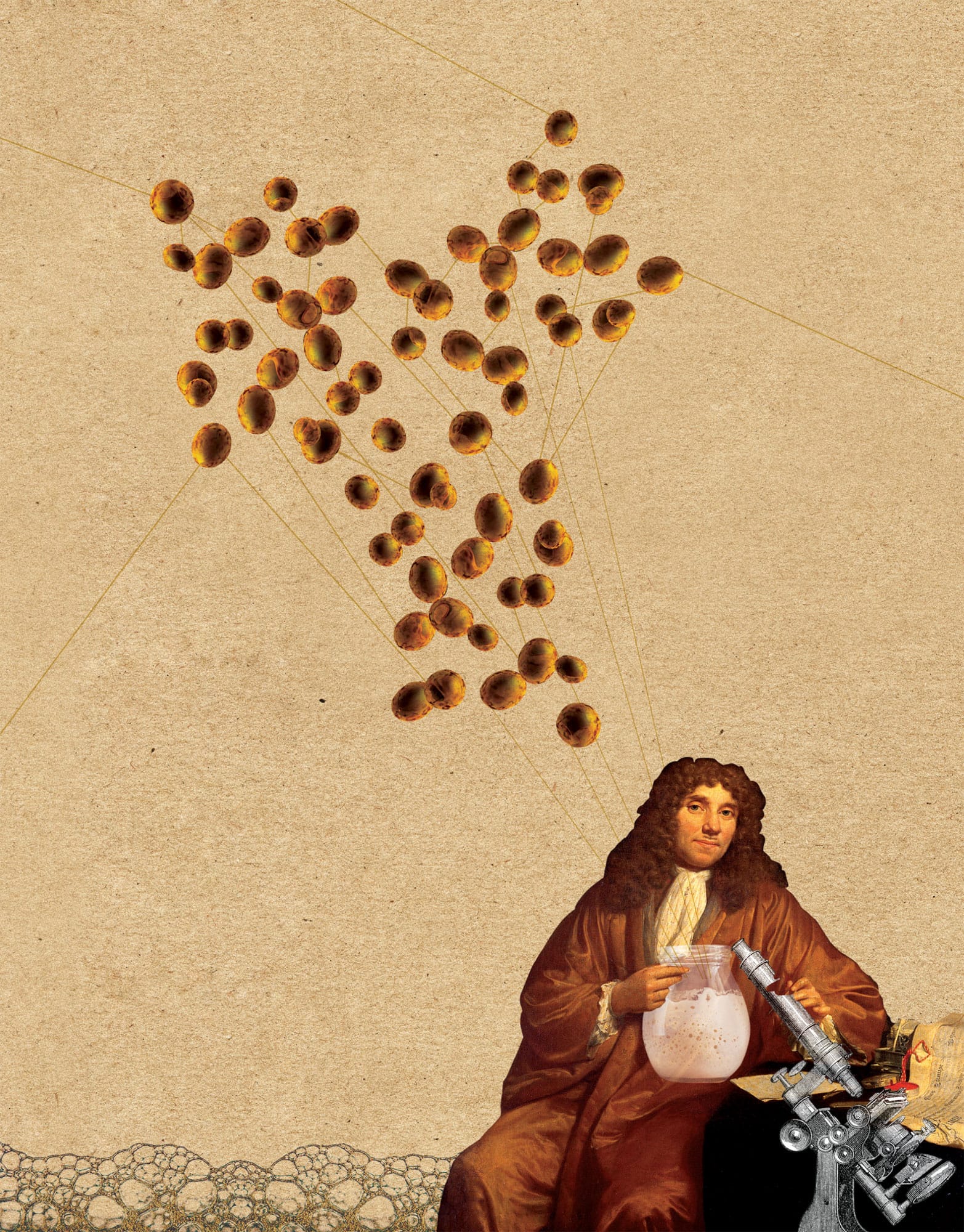

YEAST

the 30-second beer

Yeast is a single-celled organism that is neither plant nor animal, but part of the fungus kingdom. Yeasts are some of the earliest living organisms on earth. About 1,500 different species have currently been identified, and these are estimated to account for just 1% of all fungus species. From beer’s point of view, the most important species is Saccharomyces (a literal translation of the words ‘sugar fungus’ into Latin), which is known for converting sugar into alcohol and carbon dioxide. There are several species of Saccharomyces, which each in turn contain many strains. Saccharomyces cerevisiae (usually written more handily as S. cerevisiae) is the dominant species used for brewing beer as well as for fermenting grapes into wine and baking bread. As well as making this apparently simple conversion, yeast can also contribute flavour compounds, some of which are seen as desirable, others less so. In the wild, a yeast sample will contain many different strains or species within it. The work of Louis Pasteur and Emil Christian Hansen led to the cultivation of single-strain yeasts in laboratories that ensure consistent, controllable flavour. But there’s now increasing interest among craft brewers in so-called ‘wild yeasts’ such as Brettanomyces (‘British fungus’), which can contribute dry, earthy, sharp or sour flavours to beer.

3-SECOND TASTER

Yeast is the most important element in brewing, the agent that converts all the other ingredients into beer.

3-MINUTE BREW

Given its microscopic nature, the discovery of yeast – and its role in fermentation – took centuries. Early brewers used to think of fermentation as a magical process, and the foamy deposit that grew on top of fermenting ale was referred to in Britain as ‘godisgoode’. Even after yeast was first identified and described, it took over 200 years to conclusively prove that these microscopic blobs were responsible for fermentation.

RELATED ENTRIES

See also

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHY

ANTONIE VAN LEEUWENHOEK

1632–1723

Dutch draper who revolutionized lens technology and became known as the ‘Father of Microbiology’. He was the first to identify and draw yeast cells in beer, but didn’t know what they were, or what they contributed

30-SECOND TEXT

Pete Brown

It took humans a very long time to understand yeast and what it does; Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (pictured) was the first to draw yeast cells in beer, but he had no idea what they were.

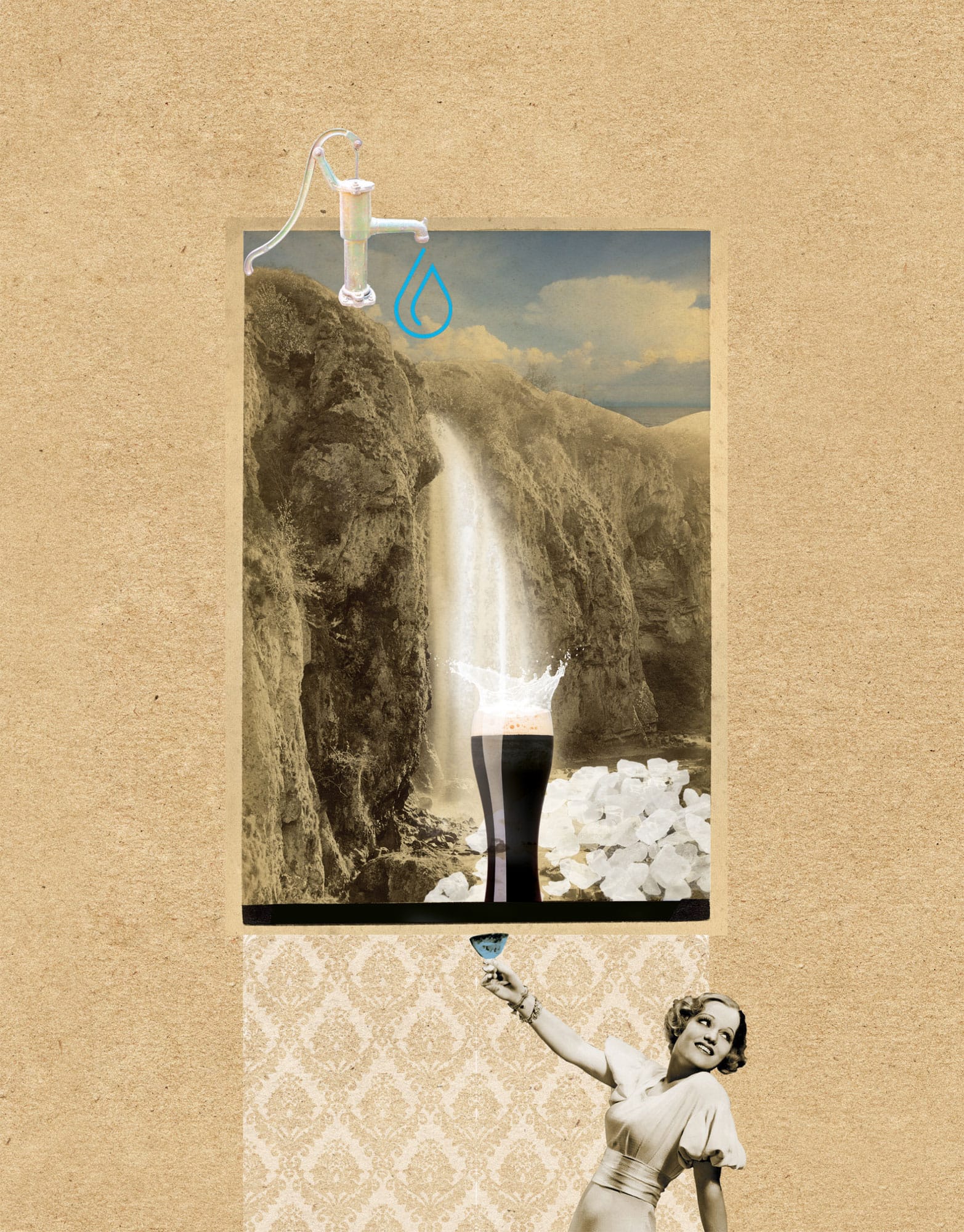

WATER

the 30-second beer

When you raise a glass of beer to your lips, are you aware that around 90% of the liquid is water? Water is often overlooked by drinkers but not by brewers, who treat it with due reverence. They don’t call it water – that’s used for washing vessels and floors. The liquid that plays a crucial role in the brewing process is called liquor. Water is the result of rain falling on the earth and percolating through soil and rock until it settles on a water table. During that journey, the water absorbs mineral salts, and the level and type of salts have an important impact on the beer being brewed. Modern lagers are based on the first golden version of the style brewed in Pilsen in Bohemia in the nineteenth century – hence pilsner. These have a satiny smoothness and are made with water with a low level of salts: the level of salts in the water in Pilsen is 30.8 parts per million. In sharp contrast, the waters of the Trent Valley in England are rich in salts: 1,226 parts per million. The area is home to Burton-on-Trent, world-famous as the town where pale ale and IPA were created in the nineteenth century. Today brewers worldwide who brew pale ale ‘Burtonize’ their liquor, adding gypsum and magnesium salts to replicate the true pale-ale style.

3-SECOND TASTER

Water is critical for brewing and varies according to geography – soft water is ideal for lager; hard water, rich in mineral salts, is ideal for pale ale.

3-MINUTE BREW

One of the great brewing myths is that Guinness in Dublin uses water from the River Liffey to make its famous stouts. The Liffey is tidal and would need to be heavily filtered and cleaned to remove waste. In fact, the brewery uses pure water drawn from the Wicklow Mountains. Brewers who use public water clean and filter it to remove impurities and unwanted chemicals.

RELATED ENTRIES

See also

30-SECOND TEXT

Roger Protz

Differences in water used for brewing can affect the flavour and mouthfeel of the finished beer much more than many drinkers realize.

SPECIALITY BREWING

the 30-second beer

After brewers discovered hops and got the hang of consistent fermentation, beers not made with time-honoured ingredients and methods started to die out. In recent years, interest in such beers has rekindled, as modern brewers look to expand their repertoires. Something has to balance beer’s natural sweetness. Before hops took over, herbs and spices were used. Now, sweet gale, heather, spruce tips and herb blends (gruit) add exciting flavours. Coriander seeds are widely used in Belgian wheat beers and Gose, while cinnamon, chilli and coffee regularly find a home in stouts and porters. Demand for sour beers is increasing. Here, fermentation is by various mixes of yeasts: brewer’s yeast, wild yeasts and bacteria strains, such as Lactobacillus and Pediococcus, which produce a lactic acid tartness, while wild yeasts add an attractive mustiness. For Belgium’s classic sour Lambic beers, the souring micro-organisms are allowed in from the atmosphere for ‘spontaneous fermentation’. Other brewers add them by hand. All kinds of fruit and honey are added to beers so yeasts can feast and leave behind added flavour in Lambics, American IPAs and pale ales, and British ales. You name it, it’s been added to beer. Even old-fashioned milk stout, sweetened with unfermentable lactose, has been re-invented as pastry beer, with added flavours for dessert-like effects.

3-SECOND TASTER

Brewers are updating old brewing methods and ingredients in a quest to innovate, proving there’s nothing new under the tun.

3-MINUTE BREW

Farmhouse beers were once widespread across northern Europe and are re-emerging, but rarely commercially. Norwegian ‘raw’ beers are brewed using unboiled wort and fermented by ‘kveik’ yeasts. Finnish sahti uses few or no hops but strains the wort through juniper twigs. Swedish Gotlandsdricka is similar. The limits of beer are being pushed by Sweden’s Omnipollo and others. Creative use of grains and natural flavour essences and ingredients such as marshmallows and lactose make dessert-like beers.

RELATED ENTRIES

See also

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

JEAN-PIERRE VAN ROY

1942–

Third-generation brewer at Belgian Lambic brewery, Cantillon

HENOK FENTIE

1980–

Swedish former homebrewer and joint founder of Omnipollo, a ‘phantom’ brewery that uses breweries in Belgium, the UK and the USA, often to make beers that are the antithesis of the Reinheitsgebot beer ‘purity’ law

30-SECOND TEXT

Jerry Bartlett

Brewers love to stretch the notion of what a beer can be to bring us new flavours and styles.