BEER STYLES

BEER STYLES

GLOSSARY

ABV Alcohol By Volume. Usually expressed as % ABV. The percentage of alcohol by volume in a beer.

barley wine An ale of British origin, usually amber to bronze in colour. Named because of its wine-like strength, around 8–12% ABV, and predominant malted barley flavour. (Usually less bitter than equivalent strength IPAs.)

bière de garde Originally, brewed in farmhouse breweries in northern France in the cooler months to sustain farm workers in the summer months when, in the days before refrigeration, no brewing took place. Usually malty and relatively strong.

Bock A malty, sweetish lager of around 6–7% ABV, blond to chestnut in colour, originally from Einbeck, Germany. There are stronger versions (Doppelbock and Eisbock) as well as seasonal variations including Maibock (for May). Weizenbock is a warm-fermented variant.

craft beer A term that originated in the USA and which meant beer produced by the small, independent breweries founded since the late 1970s – as opposed to mass-produced lagers. Now used far beyond the USA. Usually (but not exclusively) denotes beer in the style of, or inspired by, American craft brewers. Confusingly, it is also increasingly employed as a marketing term by larger established breweries for sub-brands (some of which are made using separate, smaller brewing facilities) to give the impression of being an independent brewery. The definition of craft beer is contentious, especially in the UK, but many beer enthusiasts see it as being about the ethos and intent of the brewer, especially one dedicated to making beer that puts quality before market share.

double Also called ‘dubbel’ (from the Flemish), a Belgian beer style the invention of which is attributed to Trappist brewery Westmalle but is now widespread. The name derives from its supposed relative strength to standard beers. Most examples are around 6–8% ABV, dark red-brown in colour with rich malt, restrained hops and yeast-influenced character.

Dunkel German for dark. Denoting a brown, to dark brown beer, as compared to a Helles, which is pale to golden.

Gose A wheat beer flavoured with coriander and brewed using salt or salty water. Originating from the Leipzig area of Germany, its popularity has increased in recent years.

gruit A blend of hedgerow herbs used to flavour and season ales before the use of hops became widespread.

IPA Stands for India Pale Ale; a stronger version of the pale ale style.

Lambic Acidic-tasting (sour) wheat beers from the Brussels area of Belgium fermented by wild yeasts and bacteria allowed to settle on the wort cooling in open vessels in a process known as spontaneous fermentation. A blend of Lambics of different ages is called ‘Gueuze’.

Märzen A stronger lager, traditionally brewed in March (März in German) before the once-decreed brewing close season that lasted from 23 April to 29 September and often associated with Munich’s Oktoberfest.

saison An ale style (belonging to the farmhouse ales family) originating from Belgium, where it was historically brewed as a seasonal beer to refresh the farm workers. Saisons are characterized as refreshing, dry, and highly carbonated.

Schwarzbier German for ‘black beer’. A dark lager, ranging in colour from very dark brown to almost black because it contains dark roasted malts that give it a toasted, slightly burnt flavour.

session IPA An ale that has the hoppy bitterness of a modern American-style IPA, but which is not as strong in alcohol, making it more suitable for drinking several in one sitting – a session.

Trappist Denoting beers brewed at a Trappist monastery recognized by the International Trappist Association. Trappist beers are often strong (7–10% ABV) and conform to styles originating in Belgium. Beers brewed in similar styles but not at one of these monasteries are known as Abbey-style beers.

triple Another Trappist invention, stronger than a double, but at around 8–10% ABV, not triple the standard strength. Golden in colour, drier and hoppier than a double. Also known as tripel, from the Flemish.

wild yeast Yeast varieties that live in the natural environment and have not been cultivated for use in breweries or bakeries. Some breweries use them to ferment their beers because they impart unusual but often desirable flavours.

PALE ALES

the 30-second beer

Pale ale revolutionized brewing not only in Britain but throughout the world in the nineteenth century. The style was made possible by the new technologies of the Industrial Revolution, when commercial coke production on a large scale led to it replacing wood as the fuel used in maltings. The result was pale rather than brown malt. India Pale Ale (IPA) was developed in London and Burton-on-Trent to meet a demand from the British in India for a more refreshing beer than dark milds, porters and stouts. IPAs were strong in alcohol and a lower gravity version – pale ale – was developed for the domestic market. Both IPA and pale ale were brewed using just pale malt and brewing sugar, and were heavily hopped. They were also aged before they were ready for consumption but when brewers started to build large pub estates they wanted beer that could be brewed and served quickly. The result was ‘running beer’ that had just a short conditioning in the pub cellar. It was dubbed ‘bitter’ by drinkers and it remains the most popular British beer style. While pale ale and bitter are low in strength they are well hopped, giving the beers fine floral, peppery or spicy aromas and flavours, balanced by juicy and honeyed malts.

3-SECOND TASTER

Pale ale and its big brother India Pale Ale changed the face of brewing in the nineteenth century and it even influenced lager brewing in central Europe.

3-MINUTE BREW

In the late twentieth century a number of British brewers developed golden ale, a new style of pale beer. Unlike modern bitters and pale ales, which often blend darker crystal malt with pale malt, golden ales are as pale as lager. Many brewers use American, European and Australasian hops in golden ale and as a result it has a fruity/citrus character quite different to pale ale.

RELATED ENTRIES

See also

BEER & THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

30-SECOND TEXT

Roger Protz

Pale ales were groundbreaking when first invented and are still making waves in the world of beer today.

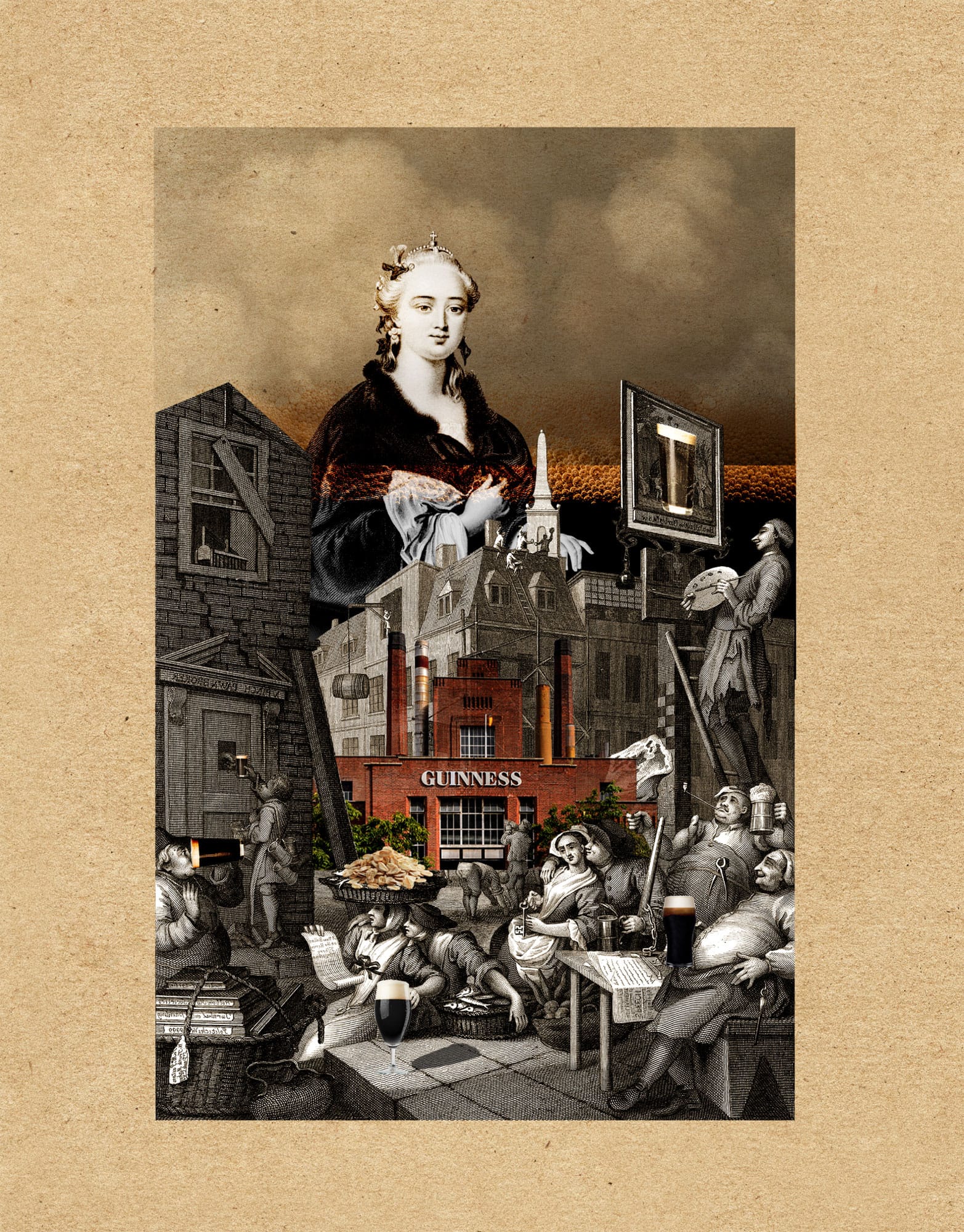

STOUT & PORTER

the 30-second beer

In eighteenth-century London, drinkers developed a taste for beers with a smoky character, made using malt dried over open flames. This beer was often aged to allow smoke to diffuse but ageing also turned the beer sour. For balance, a mix of aged sour beer and fresh smoky beer went on sale and became popular, it seems, with the porters of London who lent their name to the drink. Stronger versions of ‘porter’ were called stout porter – stout for short. The development of smoke-free pale malt – which also provided more brewing sugar than smoky malts – saw pennywise brewers switch ingredients, using mostly pale malt and maintaining the dark colour and roasted notes with a small amount of dark malt or roasted, unmalted barley. Hence, the nature of both stout and porter changed over time, especially as the ageing process became less significant. Today, stouts and porters – the names are now largely interchangeable – come in a variety of styles. Irish stout has a dry, bitter note from roasted barley, while milk stout includes lactose for creaminess and extra body. Oatmeal stouts feature oats for a silky character and imperial Russian stouts are both strong and well hopped – a legacy of the days when these beers were exported across the Baltic, and alcohol and hops helped keep the beer fresh.

3-SECOND TASTER

Stout and porter are related beers that have changed character considerably since their early popularity in eighteenth-century London.

3-MINUTE BREW

A story is told about a wily brewer named Ralph Harwood who, it is said, invented porter. Noting that drinkers often enjoyed a mix of beers and, seeing publicans racing from cask to cask to meet their request, Harwood reportedly invented a beer served from one cask that achieved the same effect. However, while the idea of blending beers seems accurate, there is evidence that the term ‘porter’ existed some time before Harwood’s possible intervention.

RELATED ENTRIES

See also

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHY

CATHERINE THE GREAT

1729–96

Beer-loving Empress of Russia whose courtiers in St Petersburg were big consumers of exported strong British stout, which thus became known as ‘imperial Russian stout’

30-SECOND TEXT

Jeff Evans

Guinness may be the most famous example of the style, but it wasn’t the first – and it isn’t the last word on stout or porter.

STRONG BEERS

the 30-second beer

Want to show off? Choose and share a high ABV beer with a friend! Barley wines, and old and vintage ales give the brewer the canvas with which to display a wonderful depth and variety of flavours. To raise the alcohol levels in a beer, as well as additional malts, brewers need to help the yeast. Either they add in more yeast, or they find one that can cope with a higher alcohol environment, or, as with Eisbock, they ‘jack’ the beer, partially freezing it, removing some water and concentrating it. While care is needed to avoid contamination, wild yeasts can often ferment further than their conventional cousins, adding in unusual flavours, too. Colours in old, strong beers can range from deep gold through to midnight black and the flavour spectrum is almost limitless. Think rich Christmas cake-filled aromas with sultanas and plums, vanilla and spices in an aged barley wine, or vinous, tangy, almost sour notes in a beer that’s been barrel matured. Sometimes there’s a savoury, umami flavour from time spent on the lees, and if there are dark malts, expect coffee, nuts and dark chocolate, too. Originally a ‘must’ for all fashionable aristocracy in Great Britain, barley wines in Britain tend to be mostly about the malt whereas hops are more prominent in America. With a carefully selected recipe each year, beers like the highly prized Fuller’s Vintage Ale repay careful cellaring.

3-SECOND TASTER

With their fabulous richness, strong beers offer a chance to celebrate the brewer’s skill and, like wine, the chance to cellar and age them for drinking at a later date.

3-MINUTE BREW

Cornish Brewery Company kicked off the world’s strongest beer wars in 1986 using three different yeasts to reach 16%. Sam Adams’ Utopias arrived in 2002. Now 28%, its multi-yeast strategy includes a ‘Ninja’ yeast, able to withstand high ABV conditions, plus a range of barrels for ageing. In the late 2000s, German brewer Schorschbräu took on BrewDog as both began ‘jacking’ (fractional freezing) their beers. In 2011, Schorschbock 57 (57%) won, just ahead of BrewDog’s End of History (55%).

RELATED ENTRIES

See also

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

JOHN KEELING

1956–

Former head brewer at Fuller’s. Established Fuller’s Vintage Ale as one of the world’s finest, most age-worthy beers

MENNO OLIVIER

1963–

Founder of de Molen in the Netherlands, the brewery behind Bommen & Granatan, an extraordinary barley wine

30-SECOND TEXT

Susanna Forbes

Strong ales offer some of the richest, most intense flavour experiences.

LAGERS

the 30-second beer

Over 90% of the world’s beer consists of variations on one style: pale, golden ‘pilsner’ lager. Pilsner Urquell (literal translation, the ‘original pilsner’) was created by Josef Groll in the Czech town of Plzen in 1842, and the style spread rapidly, spawning so many imitators, that ‘pilsner’ or ‘Pilsener’ became the world’s dominant beer style by the end of the nineteenth century. Most big commercial brands in countries across the globe are blander interpretations of the style than the original, noted for being cold, crisp and refreshing, with a very light, delicate flavour. This is what most people regard as beer, certainly as lager. But in its heartland of central Europe, there’s much more to lager than this commercialized juggernaut. A true pilsner from the Czech Republic or Germany still has a clean, subtle character, but has a satisfying dryness and a distinct grassy or citrus hop character. Munich-style Helles looks similar to pilsner but is slightly sweet, with lower bitterness. And lager existed long before pilsner. Vienna-style lagers are amber, with slightly more caramel character. Märzen and Bock are stronger and seasonal, while German Dunkel and Schwarzbier can be dark brown or almost black, have a fuller flavour, but still retain some of lager’s crisp lightness.

3-SECOND TASTER

Lager is much-maligned and abused, but beyond the obvious brands there’s a wonderful variety of style and character to discover.

3-MINUTE BREW

Because good-quality lager should ideally be stored at low temperatures for several weeks, it’s more expensive to brew than ale and requires more equipment. This, plus mainstream lager’s poor reputation among discerning drinkers, means that the range of lager styles hasn’t yet been fully explored by craft brewers and drinkers. But lager’s delicacy leaves nowhere for faults to hide, making lager an intriguing and increasingly attractive challenge for ambitious craft brewers.

RELATED ENTRIES

See also

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHY

GABRIEL SEDLMAYR

1772–1839

Brewer at the Spaten Brewery in Munich, who copied British pale-ale brewing techniques and applied them to lager for the first time, creating the basis for what Josef Groll then developed into pilsner lager

30-SECOND TEXT

Pete Brown

Lager is one of brewing’s nomadic migrants, starting life in Europe, travelling across the Atlantic and spreading throughout the world.

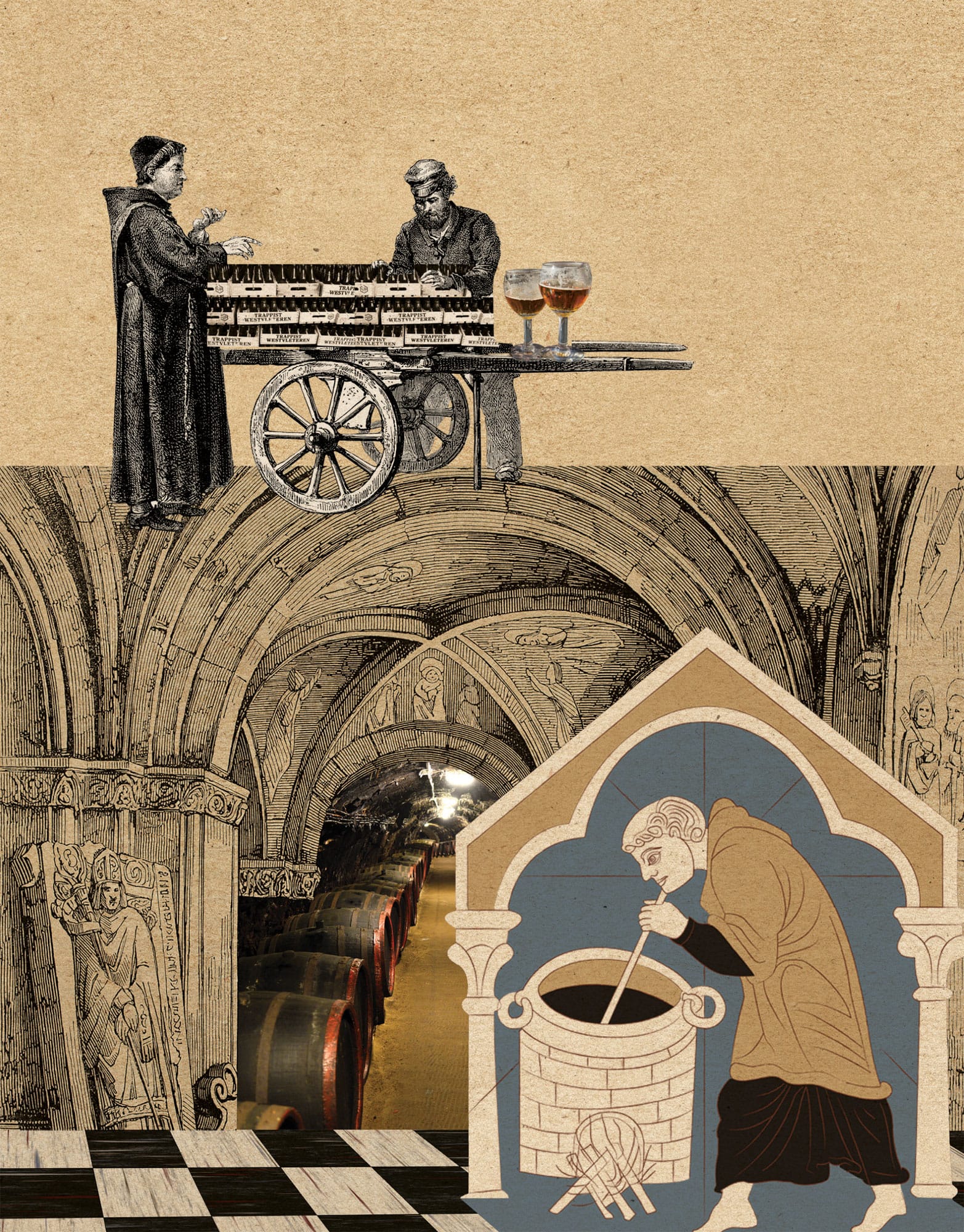

BELGIAN STYLES

the 30-second beer

That a small country like Belgium is considered a great brewing nation is down to the diversity of beer styles it has managed to preserve. Britain and Germany may have hundreds of beers, but they are variations on a few themes. Belgium has perhaps 12 distinct families, most of which could be subdivided. Belgian beers sometimes use sugar, fruit or spices, but everything, even hops, takes a back seat to fermentation. Belgian styles capitalize on yeasts that produce a complex range of flavours, and warm fermentation in various, often intricate procedures: multi-stage warm fermentation, long barrel ageing, cool conditioning, bottle conditioning, as well as spontaneous fermentation. Belgium’s Trappist monasteries and abbeys produce strong, flavourful brews fermented multiple times to produce dark, rich ‘doubles’ and pale, dry ‘triples’. Wallonia’s saisons are originally farmhouse-brewed seasonals, as were Bière de Garde in French Flanders. Saison yeast produces highly carbonated, crisp and refreshing beers compared to their maltier French cousins. There are strong golden ales, some of ordinary strength. Strong, malty scotch ales are often produced for Christmas. All styles are dominated in quantity by golden lagers, which might have eradicated all in their path if it hadn’t been for the persistence of a couple of foreign beer writers championing their cause.

3-SECOND TASTER

Belgium’s diverse range of styles includes many strong and flavourful beers that gain their distinctiveness from special yeasts and often complex fermentation.

3-MINUTE BREW

After touring Belgium in the 1970s, British beer writer Michael Jackson and later, Tim Webb, eulogized Belgian beer beyond its borders. Exports increased, especially to the USA, establishing as world class the Trappist breweries Orval, Chimay and Westmalle, and the classic saison producer Dupont. Undoubtedly, this helped small Belgian breweries survive and prosper. Then, as part of the craft beer movement, American breweries such as New Belgium emerged to produce their own interpretations of Belgian styles.

RELATED ENTRIES

See also

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

PETER CROMBECQ

1956–

Belgian beer and genealogy writer and founder of consumer organization De Objectieve Bierproevers (The Objective Beer Tasters), and champion of beers of the Benelux region

TIM WEBB

1956–

British writer known for his expertise on the beers of Belgium

30-SECOND TEXT

Jerry Bartlett

Belgium’s wide range of traditional beer styles has influenced many a modern brewer.

WHEAT BEERS

the 30-second beer

Wheat beer is an ancient and venerable member of the ale family that dates back to antiquity. Some 6,000 years ago wheat beers were brewed in Egypt, Mesopotamia and Sumeria. Wheat beer is most closely associated today with Bavaria in southern Germany, where it’s the most popular style with drinkers. In the sixteenth century, wheat beer production became a royal monopoly: the masses were allowed to drink barley-based beer while the nobility consumed paler and more refined wheat beer known as ‘weiss’, meaning white. The monopoly was gradually relaxed, and commercial wheat beers were brewed from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The style went into steep decline with the rise of lager beer but enjoyed a remarkable recovery in the late nineteenth century when it was taken up by young drinkers who saw it as a healthier style than lager. As a result of the yeast used, Bavarian wheat beer has a pronounced aroma and flavour of cloves and Juicy Fruit bubblegum. The beers are lightly hopped. Wheat beer is also popular in Belgium, where sales took off as a result of the popularity of one brand, Hoegaarden. The beer is a blend of malted barley, unmalted wheat, hops, coriander and curaçao orange peel. Other Belgian brewers add fruit and spice to their interpretations of the style.

3-SECOND TASTER

Wheat beer is an ancient style that dates back to the time of the pharaohs. The main producers of wheat beer today are found in Bavaria and Belgium.

3-MINUTE BREW

Wheat beer is something of a misnomer, as it’s brewed with a blend of malted barley and wheat. Wheat doesn’t have a husk and can cause problems when used in brewing: barley, with its tough husk, prevents wheat from clogging pipes. In Bavaria, drinkers prefer the naturally cloudy, unfiltered version of wheat beer known as ‘hefeweisse’ – with yeast – though there are filtered versions called Kristall.

RELATED ENTRY

See also

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHY

PIERRE CELIS

1925–2011

Revived wheat beer in Belgium. He had worked at the last wheat beer brewery in Hoegaarden and when it closed, he bought some brewing equipment and recreated the beer with enormous success. When a fire destroyed the brewery, Celis accepted financial support from Stella Artois to rebuild the plant

30-SECOND TEXT

Roger Protz

Wheat beer has a long history, including falling out of fashion, then a revival into an iconic style.

SOUR BEERS

the 30-second beer

Your first taste of an intentionally sour beer can be a shock, if all you’ve ever tried is conventional beers. But really, a sour beer is just more acidic, like dry white wine or cider. Over the centuries, where most other brewing countries got rid of the sourness in their beers, Belgium turned sour beers into an art form. Its Lambic beers from the Brussels area are spontaneously fermented by the airborne wild yeasts and bacteria allowed to drift into the brewery and set to work on the cooling, unfermented beer left open to the winds. The sourness in the red ales of West Flanders and the brown ales of East Flanders comes from the mixed yeast and microbial culture added physically/deliberately to the unfermented beer. The art in sour beer making comes in maturing the beer, usually in oak barrels. Young Lambics are too sharp and older ones too flat, so different ages are blended and bottled to become Gueuze, getting a Champagne-like spritz from fermentation in the bottle. If cherries are added to a Lambic it becomes Kriek; raspberries make Framboise. Two old German styles are becoming popular again, both mildly tart, light, easy-drinking wheat beers: Berliner Weisse, often flavoured with fruit or spices, and Gose, distinctive because of the addition of coriander and salt.

3-SECOND TASTER

Sour beers are making a comeback, having just about survived in Belgium and Germany, because of interest from modern brewers in Europe and the USA.

3-MINUTE BREW

Craft breweries are now emulating Belgium and Germany’s classic sours. Gueuze producers Cantillon and Boon inspire Allagash’s (USA) Coolship series. Wild Beer’s (UK) Modus Operandi is inspired by Flanders: Old Brown styles and Rodenbach red. Denmark’s Mikkellers have two fruit-flavoured series: ‘Ich bin ein Berliner Weisse…’ and ‘Sponta…’, which uses Belgian-produced Lambic. Brekeriet’s (Sweden) whole output is based on wild fermentation. For a modern Gose, try Magic Rock’s (UK) Gooseberry Salty Kiss for summer refreshment.

RELATED ENTRIES

See also

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

EUGÈNE RODENBACH

1850–1889

Grandson of Pedro Rodenbach, one of the founders of the Rodenbach brewery in West Flanders, Belgium, famed for its sour red beers. He took over the brewery in 1878 and introduced the huge oak vats (foeders), used to mature beer

PAUL CANTILLON

c. 1880–1952

Founder of the Cantillon brewery in Brussels, in 1900. Initially, he bought and sold Lambic beers and blended them to make Gueuze. By 1938 Cantillon started brewing its own beers. Cantillon is one of the world’s most significant producers of sour beers

30-SECOND TEXT

Jerry Bartlett

Refreshing tartness is the goal in sour beers, often balanced by fruit and other flavours.

AMERICAN CRAFT BEERS

the 30-second beer

If a love of traditional European beer styles ignited the American craft beer movement in the late 1970s, it was the creation of American IPA that turned it into a revolution. The seeds of this revolution came from new American hop varieties like Cascade, with its intense flavours of grapefruit and pine resin. When Sierra Nevada used Cascade in its pale ale, a new style was born. In turn, the American version of IPA was stronger, bolder, more bitter and more aromatic than contemporary British versions. Emerging around 1985, by the turn of the millennium, American IPAs dominated the craft scene as the perfect style to show off the flavours and aromas offered by an ever-increasing range of hops: Chinook, Citra, Amarillo, Simcoe, and so on. Brewers never lost sight of other styles. The Great American Beer Festival’s competition runs to almost 100 categories – 20 containing ‘American-style’ in the name. Beer rating sites show a fascination for big styles like imperial stouts and porters and using barrel ageing to impart flavours to the beer from the barrels’ previous contents (whiskies, wines, and so on). Breweries sprang up to create American interpretations of Belgian sour styles, and used exotic yeasts like Brettanomyces. American craft beers reflect both a desire for beer style authenticity and a compulsion to push frontiers.

3-SECOND TASTER

American brewers created their own take on pale ale and IPA to showcase American-grown hops and kick-started a worldwide craft beer movement.

3-MINUTE BREW

Because of the near ubiquity of IPAs in the USA, sub-genres and regional variations create diversity. East Coast IPAs are rounder and not as mouth-puckering as West Coast ones, while soft, hazy, New England IPAs pack their huge fruitiness from massive amounts of dry hopping. Then there are double (or imperial) and even triple IPAs, which ramp up alcohol levels, while session IPAs dial them down.

RELATED ENTRIES

See also

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

KEN GROSSMAN

1954–

Founded the Sierra Nevada Brewing Company in Chico, California, now one of the top 10 craft breweries in the USA

SAM CALAGIONE

1970–

Founded Dogfish Head in 1995 in Delaware. Known for creating ‘extreme’ beers: unusually strong or which use unusual ingredients. His ideas have become widespread in craft beer

30-SECOND TEXT

Jerry Bartlett

The hop-fuelled craft beer revolution in the USA has made it arguably the world’s leading beer nation.

OTHER SIGNIFICANT STYLES

the 30-second beer

The USA-based Beer Judge Certification Program (BJCP) identifies well over 100 different styles of beer – and acknowledges it doesn’t cover every style! Nevertheless, its widely used guidelines help illustrate how many types of beer there are. Within each style are hundreds of individual interpretations of the given type of beer. The most notable and prevalent styles are covered in the preceding pages. Get to know these and you can go on an incredible voyage of discovery within them. Beyond that there’s a world of speciality, seasonal and other beers to explore. Those described as ‘speciality’ usually involve ingredients that add flavour in addition to hops. Chilli beers might sound whacky but can be a marvellous match for food. Coffee beers, often brewed in collaboration with independent roasteries, are a widespread phenomenon. Genuinely seasonal beers are only made at the time of year that the relevant ingredient is harvested. Pumpkin and green hop beers are two good examples. The autumnal squash forms part of the mash of pumpkin beers, with spices added later. Hops are usually dried at harvest time for use throughout the year ahead. Green hops (also referred to as ‘wet’ or ‘fresh’) must go into the brew just hours after being picked and create a characteristic light freshness in the beer.

3-SECOND TASTER

There are more than 100 different styles of beer and hundreds of versions of each style are brewed around the world.

3-MINUTE BREW

Even though the barley used in beer is naturally low in gluten, many brewers use enzymes to make gluten-free versions, safe for coeliacs. There are also beers made from alternative, gluten-free grains such as sorghum, buckwheat and millet. Not a fan of hops? Although very niche, there are brewers who still make beers flavoured with a mixture of herbs and spices known as ‘gruit’, which usually includes bog myrtle and yarrow among its ingredients.

RELATED ENTRY

See also

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

DEREK GREEN

1940–

The man behind Green’s, one of the early pioneers of commercially available gluten-free beer. In 2004, after teaming up with a Belgian professor, he released a beer made with alternative grains. The range also includes brews made with de-glutenized barley

BRUCE WILLIAMS

1960–

Founded Williams Bros Brewery, which makes famous heather ale, Fraoch, essentially a gruit (although it includes some hops). He got the 4,000-year-old recipe from a woman who came to his Glasgow homebrew shop in the late 1980s; she agreed to share the recipe in return for learning how to brew it

30-SECOND TEXT

Sophie Atherton

Much of beer’s versatility as a drink stems from the wide variety of styles.