THE BEER INDUSTRY

THE BEER INDUSTRY

GLOSSARY

beer garden Garden or outdoor area of a pub, especially in the UK, used as area to drink and eat. (Equivalent to Biergarten in Germany.)

beer hall A large pub where the predominant beverage served is beer. Beer halls are commonly associated with Germany.

craft beer A term that originated in the USA and which meant beer produced by the small, independent breweries founded since the late 1970s – as opposed to mass-produced lagers. Now used far beyond the USA. Usually (but not exclusively) denotes beer in the style of, or inspired by, American craft brewers. Confusingly, it is also increasingly employed as a marketing term by larger established breweries for sub-brands (some of which are made using separate, smaller brewing facilities) to give the impression of being an independent brewery. The definition of craft beer is contentious, especially in the UK, but many beer enthusiasts see it as being about the ethos and intent of the brewer, especially one dedicated to making beer that puts quality before market share.

cuisine à la bière French term for a style of cooking, not limited to French or Belgian, that gives prominence to beer as an ingredient.

Industrial Revolution The rapid development of industry that began in Britain in the late eighteenth century, brought about by the introduction of machinery.

malt extract A syrup or powder derived from malted barley containing the fermentable sugars required for brewing. Mainly used by homebrewers to simplify the brewing process by replacing or supplementing malted grains.

Märzen A lager traditionally brewed in March (März in German) before the once-decreed brewing close season that lasted from 23 April to 29 September. Brewed stronger than is standard to keep better until brewing was permitted again.

Oktoberfest The largest beer festival in Germany, and probably the world, is part of a fayre, which takes place in Munich every year. Lasting 16 to 18 days, depending on the calendar, it ends on the first weekend in October and so is often mostly in September. Beer is served in large tents or marquees seating thousands of guests and is supplied only by the half-dozen large breweries situated within Munich’s boundaries.

one-vessel brewing A beer-brewing system that consists of a single container in which all the stages of the beer-making process take place, as opposed to the traditional system that uses three separate containers for the distinct stages.

pubco A pub company, that is, a company set up to own and run a chain of pubs, without owning any brewery that supplies beer to its pubs. The company leases the pub to be run by tenants/licensees rather than employees. Beer is sold by the pubco at fixed prices to its pubs. The practice is widespread in the UK.

real ale Also known as cask ale, a term coined by UK consumer group CAMRA (the Campaign for Real Ale). Real ale undergoes the final stages of its maturation in a container – a cask – without having been pasteurized and with little or no filtration. As live yeast remains, the beer continues to ferment slowly, providing a light, natural carbonation when served. To conform to the definition, the beer must undergo this secondary fermentation in the vessel from which it is served and cannot be dispensed using carbon dioxide (or other gas). Similarly produced beer matured in a bottle can also be real ale.

stein Glazed, kilned stoneware drinking vessel traditionally used to serve beer in Germany. Derives from ‘stone’ in German.

taproom A bar either in or close to a brewery, that predominantly serves the beers brewed by that brewery.

CORPORATE BREWING

the 30-second beer

For most of its history, brewing was small-scale and highly localized. The Industrial Revolution allowed brewers with money and vision to grow rapidly, but they still mostly dominated their local areas. Then, in the late nineteenth century, rail travel and refrigeration allowed a big brewer to potentially sell its beer across the world, and the biggest companies floated on the stock market to fund further expansion. The twentieth century saw a long, gradual decline in beer consumption in mature western markets. Big brewers were obliged to keep corporate shareholders happy by delivering ever-better returns. The only ways to do this in a shrinking market were: reduce costs, take share from the competition, or acquire that competition by merger or takeover. Beers became blander so they would offend no one. Investment went into marketing to create powerful brands but cost-cutting meant beer was commoditized and distinctions between big brands disappeared. The early twenty-first century therefore saw a rapid consolidation of brewers operating in a global market, with fewer names dominating more territories. The world’s biggest brewer, Anheuser Busch, now controls a third of the entire world’s beer supply. Together with Molson Coors, Heineken, Carlsberg and Diageo, a handful of companies now own more than 90% of the world’s beer.

3-SECOND TASTER

Most of the world’s beer is owned by five companies, all trying to deliver ever-increasing growth from a market that’s in long-term volume decline.

3-MINUTE BREW

Interest in craft beer is, in part, a reaction against corporate hegemony, driven by a desire to support small businesses as much as a yearning for flavourful, interesting beer. But big corporations are inevitably acquiring craft brewers to attempt to control this small but rapidly growing sector of the market. Such acquisitions are met with howls of outrage from the craft beer community – but corporates facing ever-intensifying pressure wouldn’t be doing their jobs if they ignored craft.

RELATED ENTRIES

See also

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHY

CARLOS BRITO

1960–

Brazilian businessman who oversaw a series of mergers and acquisitions that saw Brazilian brewer Brahma become Ambev, then Inbev, then Anheuser-Busch Inbev (AB-Inbev), the world’s biggest brewer; he focuses on delivering higher returns through a programme of relentless cost-cutting

30-SECOND TEXT

Pete Brown

Despite the advent of craft brewing, 90% of the world’s beer is still owned by just a handful of multinational companies.

CRAFT BEER

the 30-second beer

The beer world was turned upside down in the twenty-first century as a result of the craft revolution – driven by young brewers with passion and zeal, partly inspired by small-batch food producers who value provenance and the finest natural ingredients. Craft beer, too, is centred on beers the brewers themselves want to drink, using the best malts and hops, in sharp contrast to the cheap ingredients used by global producers. The thrust of the craft beer movement comes from the USA and UK. The UK has a long tradition of making beer slowly and naturally – best illustrated by cask-conditioned beer (or real ale), which is neither filtered nor pasteurized. CAMRA saved cask beer, paving the way for the growth of new small breweries, of which there are now some 2,000 in Britain. In the USA, the growth of craft is fuelled by consumer opposition to the bland products of global giants. There are now more than 5,000 American craft breweries producing an amazing range of beers. There are close to 800 small breweries in Italy, and craft production is growing in such countries as China, Hungary and Japan. Down Under, there are close to 400 small independents in Australia and 150 in New Zealand. There is no slowing down in the demand for craft, which is now a worldwide phenomenon.

3-SECOND TASTER

The buzz word of the beer world is ‘craft’ – thousands of brewers have sprung up to offer greater choice to drinkers and challenge the power of global giants.

3-MINUTE BREW

In the USA, the Brewers Association, which speaks for the independent sector, defines a craft brewer as one producing up to six million barrels a year and must be no more than 25% owned by a company that is itself not a craft brewer. There is no such definition in the UK but the term may be taken to mean an independent brewer that pays lower rates of duty under the government’s Small Brewers Relief scheme.

RELATED ENTRY

See also

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHY

BERT GRANT

1928–2001

A key player in the American craft beer movement. In 1982 he established the first US brewpub since Prohibition in Yakima Valley, Washington State. He upgraded to a full brewery in 1990, producing pale ale, IPA, Scots Ale and stout and helping to highlight the potential of Pacific Northwest hops

30-SECOND TEXT

Roger Protz

Craft beer emerged from a desire to make and drink more flavoursome brews than those already available.

HOMEBREWING

the 30-second beer

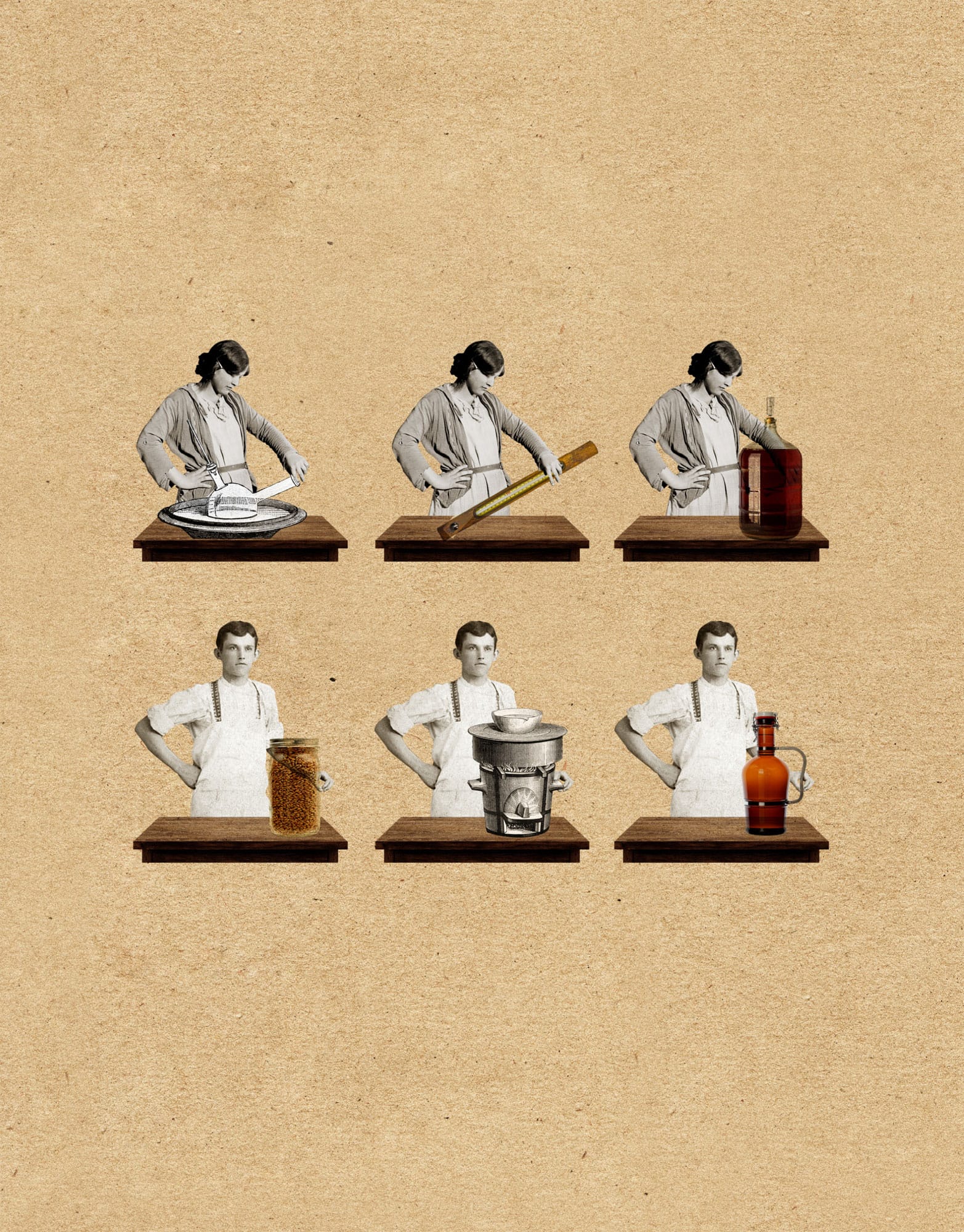

Before the Industrial Revolution, homebrewing was where most beer came from. After, almost nobody homebrewed, either for legal reasons, or because they were too busy working at the mill. It was legalized in the UK in 1963, but the homebrew produced was often poor quality. Legalization in the USA in 1979 turned out differently, effectively kick-starting the American craft beer movement that inspired the world. Superstar brewers Ken Grossman (Sierra Nevada), Denmark’s Mikkel Borg Bjergsø (Mikkeller), Australian David Hollyoak (Redoak) and many others, all started as homebrewers. Now, homebrewing is popular almost everywhere beer is. In 2017 in the USA, an estimated 1.1 million homebrewers made 1.7 million barrels of homebrew. The hobby is supported by a worldwide homebrew supplies industry, with online and local shops providing a vast range of equipment and ingredients. The market in the UK is worth around £25m. A homebrewer’s path can easily go from a stove-top beginner, brewing from a couple of cans of malt extract, to advanced, brewing sophisticated recipes with exotic malts, hops, yeast and other boundary-pushing ingredients. Even if you don’t intend to go pro, and just want to impress your friends with an authentic Märzen lager for your own Oktoberfest, your homebrewed beer can rival the quality of commercial beers, not just the price.

3-SECOND TASTER

Homebrewing has progressed beyond a way of making cheap beer – professional-quality beer is possible and many commercial brewers hone their skills before turning pro.

3-MINUTE BREW

A malt extract kit is the homebrewer’s typical starting point. The malt comes pre-processed into a concentrate with added hop extract. Stepping up to doing an all-grain full mash needs more equipment and work, but gives freedom of choice over malts and hops. Serious hobbyists might progress to a one-vessel brewing system, which does the mash and the boil. Add a mini-fermenter and you have a professional kit for a couple of grand.

RELATED ENTRIES

See also

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

DAVE LINE

1942–80

Pioneering British writer of homebrewing books, such as Brewing Beers Like Those You Buy. Influenced a generation of homebrewers and writers, helping make homebrewing respectable

ANDY HAMILTON

1974–

British author, broadcaster and industry adviser on homebrewing and a wide range of drinks-related subjects, often making use of wild or home-grown ingredients.

30-SECOND TEXT

Jerry Bartlett

Once the province of the bootlegger or cheapskate, homebrewing can produce seriously good beers.

TRADE ORGANIZATIONS

the 30-second beer

There are so many important issues related to the business of brewing – from taxation and licensing laws to environmental matters and the health lobby – that there is a clear logic in brewers banding together to fight their corner. In the USA, the body that helps promote the work of brewers and challenges legislators is the Brewers Association, which also stages the Great American Beer Festival and has played a fundamental part in the remarkable growth of the American craft brewing sector. In the UK, there are two organizations that fulfil this role. The British Beer & Pub Association (BBPA) largely represents the biggest breweries along with long-established regionals, while the Society of Independent Brewers (SIBA) provides a voice for most of the smaller concerns. Similar associations are in place around the world, including the Brewers Association of Australia, Unionbirrai in Italy and the Brewers Association of Japan. The over-arching Brewers of Europe brings together 26 member bodies from within the EU, plus three associate members, to work on a supranational level. Related industries also have representative bodies, like the Maltsters’ Association of Great Britain and Hop Growers of America, as do pubs and bars, with the Association of Licensed Multiple Retailers (now UK Hospitality) and the British Institute of Innkeeping prominent in the UK.

3-SECOND TASTER

‘No man is an island,’ declared English poet John Donne, and the brewing industry with its numerous, important trade associations recognizes that only too well.

3-MINUTE BREW

Depending on their needs, some breweries belong to more than one association. The Independent Family Brewers of Britain, for instance, is a grouping of some of the country’s oldest breweries that still have founding family members involved in the business. These brewers understand that such personal involvement is an asset that needs to be promoted, and also recognize that there are particular issues relevant to their shared heritage and company structures that are best addressed collectively.

RELATED ENTRIES

See also

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

CHARLIE PAPAZIAN

1949–

Founder of the Association of Brewers (later the Brewers Association) and its president for 37 years, overseeing the rise of craft brewing in America

MIKE BENNER

1966–

Former chief executive of CAMRA, who became managing director of the Society of Independent Brewers in 2014

30-SECOND TEXT

Jeff Evans

The brewing industry recognizes the power of collective action.

PUBS, BARS & BEER GARDENS

the 30-second beer

Beer has always been sociable. The drink that everyone can enjoy – and afford. Whether relaxing and chatting, celebrating or commiserating, plotting or planning, pubs and bars provide the perfect setting to gather and share a pint. In Europe, while monasteries offered hospitality through the Dark and Middle Ages, inns date back to pre-Roman times. In Britain, the pub was the only place to enjoy fresh cask beer, and breweries built up vast pub estates. These morphed into pub companies (or ‘pubcos’), often to the detriment of selection and quality. By contrast, a free house is unfettered in what beer it can offer. Today’s threats to pubs revolve around the availability of good beer in shops, but drinking on the premises remains popular – with many types of place to do so. Often more industrial chic than cosy havens, brewery taprooms are on the rise, offering brewers the chance to serve their beers just how they want. Community and micro-pubs are also springing up. Globally, pubs and bars are the social hub of many communities. Bavaria has gemütlichkeit, that sense of true conviviality, and beer gardens and halls cater for thousands. While homely Czech restaurants proudly sport beer tanks, Belgium has cuisine à la bière. With the craft beer revolution in full swing, US bars and brewpubs are thriving, and restaurants embrace beer with a new-found confidence.

3-SECOND TASTER

The world over, beer has been at the heart of a thriving bar and pub culture since the beginning of time – today it’s reaching the restaurant scene, too.

3-MINUTE BREW

While beer gardens and beer halls are popular all around the world, in Bavaria they are legendary. Beginning as spaces next to the town’s lagering cellars or the brewery itself, often in the shade of gigantic, sprawling trees, they soon became an institution. Sitting at communal tables, drinkers are encouraged to bring food, even sometimes their own steins. Munich in particular embraces the outdoors, boasting 80 beer gardens, the largest of which, Hirschgarten, seats 8,000.

RELATED ENTRIES

See also

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

DAVID BRUCE

1948–

Serial entrepreneur who reignited brewpub culture in the UK in late 1970s with his Firkin group of brewpubs

TIM MARTIN

1955–

Founder of UK high street pub chain J D Wetherspoon – now something of a British institution.

30-SECOND TEXT

Susanna Forbes

Originally springing up outside breweries or a town or city’s lagering cellars, Bavarian beer gardens are renowned for their spirit of enjoyment.

SPECIALIST RETAILERS

the 30-second beer

With the number of breweries rising and competition for space in pubs and bars increasingly tough, brewers have turned to the bottle and can as a means of finding a way to market. This in turn has developed a new retailing sector – the speciality beer outlet, the growth of which is well illustrated by the experience in the UK. There, pioneering beer shops opened their doors in the 1970s but the idea has really taken over in recent years, with hundreds of shops now offering excellent selections of beers. This variety – combined with lower prices than in pubs and other social trends that have made home consumption more appealing – means that ‘off-trade’ sales – helped along by online traders and subscription clubs – now surpass ‘on-trade’ sales in the UK. In the USA, the position is even more advanced, with some 80% of beer sales ‘off-premise’, delivered by a mixture of specialist beer outlets, off-licences, supermarkets and petrol stations. In Ireland, too, the long-standing preference for pub drinking is being eroded, and the scenario is similar elsewhere in the world, as established Australian ‘bottle-os’ and newer dedicated venues such as Empório Alto dos Pinheiros in São Paulo, Brazil – to give just two examples – increasingly turn drinkers’ heads.

3-SECOND TASTER

Not long ago, the choice of beers available in shops was limited – now it is astonishing, and the number of specialist outlets has rocketed.

3-MINUTE BREW

A by-product of the craft brewing revolution is the bottle shop and bar. The concept is simple but effective. The retailer stocks a huge range of interesting bottled and canned beers which customers can peruse while enjoying a draught beer from the bar, or a bottle from one of the fridges. With clients relaxed and having more time to choose, and the venue selling beer to them while they’re deliberating, everyone’s a winner.

RELATED ENTRY

See also

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

DON YOUNGER & JOY CAMPBELL

1942–2010 & 1948–

Co-founders of Belmont Station in Portland, Oregon, in 1997 – one of the first destination beer stores in the USA. Now run by beer writer Lisa Morrison

MARTIN KEMP

1957–

Acquired the Two Brewers off-licence in London in 1982 and transformed it into a magnet called The Beer Shop that finally closed in 2005

CHRIS MENICHELLI

1986–

Set up Slow Beer in Melbourne, a pioneer among Australia’s specialist retailers, in 2009

30-SECOND TEXT

Jeff Evans

Shops dedicated to beer are often owned and staffed by knowledgeable enthusiasts.