Introduction

Visual Culture in the Victorian Mediascape

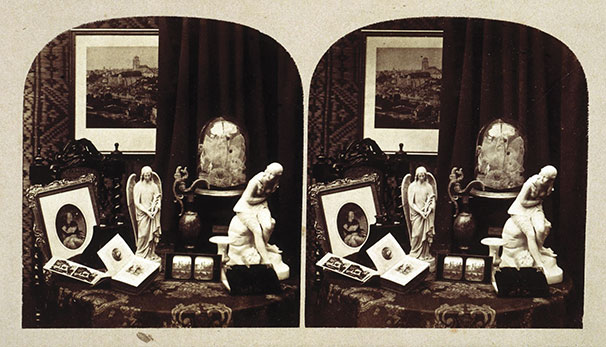

A photograph held in the Victoria and Albert Museum opens onto the idealized world of the Victorian parlor (Fig. 0.1). On the display table, luxurious commodities signal the tasteful sphere of middle-class consumption: a stereoscope with stereographic cards, an illustrated book opened upon its pictures, a photographic album, a framed engraved portrait, a statuette of an angel, an erotic sculpture of a girl bashfully concealing her nudity. The nineteenth-century viewer would have perused this doubled photograph through a stereoscope, making the image burst forth into an illusion of three-dimensional depth. In the scene of Victorian visual pleasure, the body of the spectator entered imaginatively into the volumetric space of picture, texture, and art. The photographed scene sustains Walter Benjamin’s description of the parlor as a supreme expression of the nineteenth-century self, constellating “the universe of the private individual.”1

Fig. 0.1 Unknown artist, Still Life. Stereographic photograph. Albumen print mounted on glass, c. 1860–70. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Benjamin theorized the parlor as an insular refuge from the chaos of urban modernity, an upholstered, curtained shell devoted to protective self-fashioning. Yet the parlor was not quite the hermetic casing that Benjamin envisioned, I will suggest here, nor was it a site of mere idle luxury. With its profusion of visual objects, the parlor can also be seen as a portal. It was home to the picture-world of the nineteenth century, in the form of the mass-printed photographs, advertisements, cartoons, and illustrations—ephemeral and often disposable—that flourished in the era of mechanical reproduction. These alluring objects were miniaturized spectacles that served as portals onto phantasmagoric versions of “the world.” In the world-interactive site of the parlor, mediating between private and public, families received visitors and displayed objects as evidence of a certain cosmopolitanism: maps, globes, cabinets of stereographs with views of faraway places, an illustrated Bible on a stand with scenes from the Holy Land, illustrated newspapers and magazines on a table, prints and portraits on the wall depicting figures from religious and political history.2 The parlor’s objects did not merely represent burnished collectibles; they also consisted of the daily or weekly objects of new media, flowing through in the form of news, visual fashions, up-to-date entertainments, or obsolete trends. Objects in the parlor space were dynamic, mutable, and contemporary, taking into themselves many worlds over time. Tom Gunning writes that the parlor falls “under the dominion of the image and semblance,” as “the optics of interior space take on the complexity of the phantasmagoria.”3 He points to the presence of optical toys like stereoscopes, kaleidoscopes, and magic lanterns, but his account also opens onto a broader metaphorics of world-making and illusionism via the image. Benjamin, writing of the interior’s assemblage of heterogeneous times, places, and memories, concludes of its possessor: “His living room is a box in the theater of the world.”4 This thought indicates a more permeable sense of the parlor’s enclosure, phantasmagoric but also scopic, opening onto a series of shifting views. The illustrated Bible serves as an exemplary object to anchor this space, as it mediated between tradition and modernity, the near and the far, the rare and the popular. Many of the multiform works of new Victorian visual media opened onto worlds-within-the-world, animating fantastical leaps across space and time while concretizing and literalizing a Victorian world picture.

This book studies the modern media world as it came into being in the nineteenth century. Machines were harnessed to produce texts and images in unprecedented numbers; in the visual realm, new industrial techniques generated a deluge of affordable pictorial items, consumed at intimate scale. These early forms of a widely shared media culture transformed the nineteenth-century experience of everyday life. “New media” today might bring to mind cyberspace, hypertext, and other digital innovations. But media invention itself is not new, and every epoch has had to confront the unruly and transformative effects of new communications technologies.5 Picture World turns to the small-scale printed matter of the Victorian media revolution, the mass-printed photographs, posters, cartoons, and illustrations typically designated by scholars as ephemera. Though “ephemera” implies objects existing on the margins of a weightier dominant culture, I relocate these items to a central role, using them to illuminate Victorian ideas about aesthetics, art, and visual value. The book brings together objects from across the cultural spectrum, from fine-art paintings to penny cartoons, from canonical novels to advertising copy, in order to capture the chaotic reality of the nineteenth-century cultural landscape.

I argue that nineteenth-century aesthetic ideas spring into a startling new account when considered through the lens of the century’s new visual media. Each of the book’s chapters explores a keyword in Victorian aesthetics, a familiar term whose meanings are disrupted when paired with a new media object. “Character” shows new dimensions when considered with caricature, in the new comics and cartoons appearing in the mass press in the 1830s; likewise, the book understands “realism” through pictorial journalism; “illustration” via illustrated Bibles; “sensation” through carte-de-visite portrait photographs; “the picturesque” by way of stereoscopic views; and “decadence” through advertising posters. These juxtapositions capture the book’s methodology, which finds deep meaning in ephemeral objects typically excluded from categories of high art. Picture World uses the relics of the nineteenth century’s cultural life to interrogate its deeply held values, arriving at insights still relevant in our own media age.

This method braids together high philosophy with lowbrow or middlebrow culture. It brings together the vast intellectual currents responding to modernity with the similarly massive proliferation of conventionalized material cultures. At the heights, we can ponder Martin Heidegger’s claim that “the fundamental event of the modern age is the conquest of the world as picture.”6 Heidegger speaks of the tendency to render experience in visual form, transforming “the world” into an artificial schema of representation enabling human conquest and mastery. Modernity, for Heidegger, presents itself as “the age of the world picture.” While he focuses on the conditions giving rise to modern science, his terms seem especially apt to characterize developments in nineteenth-century Britain—describing not merely Britain’s imperial activities around the globe, but also limning its advances in professionalized science, its refinements of philosophical empiricism, its creation of new forms of objectivity, its insistent technologization of culture. The tremendous production of machine-made images—in books, prints, photographs, and newspapers—functioned, through technology, to grasp the world as a picture in many dimensions. W. J. T. Mitchell frames a similar point to Heidegger in “Showing Seeing,” an essay theorizing the study of visual culture. “Visual culture is the visual construction of the social, not just the social construction of vision,” he writes. “It is not just that we see the way we do because we are social animals, but also that our social arrangements take the forms they do because we are seeing animals.”7 Mitchell’s claim serves as a useful hinge between Heidegger’s grand philosophical account of modern visuality and current scholarship on the more humble, granular works of image culture, whose aggregate comes to constitute the understandings of larger social bodies and ideas. While Heidegger’s phrase “the world picture” is singular and monolithic, Mitchell’s concept gestures toward the nineteenth century’s myriad world pictures, constructed and refracted across a range of new visual media.

Visual culture designates an innovative field that brings together cultural studies, art history, textual studies, critical theory, philosophy, and anthropology—all the interdisciplinary breadth necessary to encompass the diverse phenomena of “the visual” in modern life. In fact, the word “visuality” itself has a Victorian origin, coined by Thomas Carlyle in 1840 to describe a potent and revelatory form of seeing.8 Likewise, visual culture as a concept also has nineteenth-century roots. One of its earliest theorists was the rebellious dandy poet, Charles Baudelaire. His essay “The Painter of Modern Life” (1863), though usually remembered for its indelible figure of the flâneur, also offers a profound meditation on the nineteenth-century’s mechanization of the image. Baudelaire mocks the stultifying world of museums, high art, and unmemorable paintings. True art, he insists, is found not in museums but on the streets; and not in paintings but in machine-made items such as engravings, fashion plates, and the sketches of a contemporary magazine illustrator, Constantin Guys. It is Guys who is “the painter of modern life,” who captures modernity in all its vibrant, urban manifestations. Baudelaire celebrates lithographs and other new visual media for their speed and cheapness; they are the objects best suited to contribute “to that vast dictionary of modern life” documenting the new urban scene.9 While the modern artist’s task, tracking the ebb and flow of “the daily metamorphosis of external things,” might seem “trivial,” Baudelaire asserts that this “relative, circumstantial element” constitutes the most important aspect of beauty (4). Quick and quickly obsolescent media, unlike more eternal works of high art, bespeak a transcendent present-ness: representations of modern life are pleasurable for their “essential quality of being present” (1). And so Baudelaire famously hails “the ephemeral, the fugitive, the contingent” aspects of modernity, whose fleeting truths are best conveyed by the evanescent forms of visual culture (13). Fashion plates, newspaper illustrations, or printed lithographs all lose value over time; they are fragile, cheaply made, quickly outmoded, and eminently disposable. Yet the cultural critic moves against the grain to recover these obsolescent objects, a striking move in an era whose aesthetic canons tended to cherish old-master painters and poets. “The Painter of Modern Life” proposes a quite radical theory of aesthetics, embracing not the lasting monuments of the ages but the flimsy debris of modernity. The essay is one of the first manifestoes to declare the aesthetic and historical value of visual culture, working to redeem such doubtful traits as reproducibility, circulation, and democratic access.

More than a century after Baudelaire was writing, the nascent field of visual culture studies emerged in the 1990s to examine the rise of modern image culture. “The image, which stands at the centre-point of contemporary visual culture,” write Jessica Evans and Stuart Hall,

presents itself as a simple, singular, substantive entity—a sort of ‘fact’ or punctuation point (punctum), as Roland Barthes once called it, in its own right, whose capacity to index or reference things, people, places and events in the ‘real’ world appears palpable, irreducible and unquestionable.10

W. J. T. Mitchell, in “The Pictorial Turn,” says that the picture is “a complex interplay between visuality, apparatus, institutions, discourse, bodies and figurality.”11 He also notes, though, that “we still do not know exactly what pictures are,” pointing to the difficulty facing any theoretical attempt to unify the visual culture field and its objects.12 Svetlana Alpers, looking back on the method of her influential art-historical study The Art of Describing: Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century (1983), observes the cluster of interests that for her constituted visual culture. They included “notions about vision (the mechanism of the eye), … image-making devices (the microscope, the camera obscura), and … visual skills (map making, but also experimenting) as cultural resources related to the practice of painting.”13 Though Alpers still subordinates all of these interests to “the practice of painting,” her diverse account of Dutch visuality limns a method concerned equally with paintings and with less elevated forms of cultural expression across a range of institutions, practices, and objects.

In the 1990s, visual culture studies bore the wrath of some art historians who circled the wagons to protect their traditional bailiwick.14 Today, the divide between a conservative art history and a radical visual culture studies is more muted, as some departments have reconfigured themselves under a broader mantle of “visual studies,” and art historians often consider a wide array of visual media, including the mass-produced objects of print culture. Picture World positions itself at the forefront of a new art history, one that encompasses design history, the history of photography, and the history of visual ephemera. Art history’s expanded visual field is apparent, for example, in the Victoria & Albert Museum’s blockbuster 2011 show The Cult of Beauty: The Aesthetic Movement 1860–1900, which featured posters, wallpaper, and domestic crafts alongside canonical paintings and sculptures. In seeing Britain as a vital site of nineteenth-century visual cultural production—in a field that has traditionally favored France—Picture World participates in some of the newer trends opening up the art-historical field.15

Having said this, readers will observe that many of art history’s traditional disciplinary techniques are absent from the book. The chapters contain few discussions of artists, schools, periods, provenance, archives, or any analysis evincing what W. J. T Mitchell describes as the discipline’s “forensic skills of connoisseurship and authentication.”16 My method takes its cues from literary and cultural history, resulting in an approach to the image that is occult, sideways, deliberately estranging. Influenced by cultural critics like Walter Benjamin and Roland Barthes, I privilege philosophical and conceptual analysis, crossing genres and bridging the word–image divide. In fact, Picture World enacts a radical interdisciplinarity, bringing together a broad range of different humanistic and technological fields. Visual culture studies, media history, art history, literary history, and cultural history number among the book’s disciplines. The chapters move across media to study novels and poems alongside photographs and illustrations.17 The analysis never presumes a vague equivalence between different kinds of sign-making; each medium moves according to its own distinct generic rules and expectations. But no single medium is ever consumed in a vacuum. The book weaves together both visual and textual strands to present a revisionist, multidisciplinary approach to “culture” as it was lived and experienced in the nineteenth century. Modern-day academic divides between disciplines have obscured the cross-media connections studied in the book. This approach speaks to a certain historical reality: in the nineteenth century’s turbulent media moment, the bounds of high art and mass culture were not yet fixed, and words and images mingled indiscriminately in the cultural field.18

A key aspect of Picture World’s interdisciplinarity is its theorization of aesthetic ideas by way of cultural studies. Scholars have typically explored concepts such as realism or the picturesque by looking to novels, paintings, or other vaunted objects in today’s aesthetic canon.19 The people who actually lived in the nineteenth century, however, would have experienced a proliferation of new visual media in their daily lives, whose codes and ideologies intersected with the fine arts to create intense fantasies of time and space, self and other. My approach breaks down the boundaries that have typically divided high art from mass culture; it produces a new way to study aesthetics, describing art values according to an expanded array of objects. Familiar concepts become new to us when we explore their simultaneous appearance in objects of high art and more popular, conventionalized visual forms. For example, I argue that the “sensation” phenomenon of the 1860s—usually associated with scandalous crime novels—had a visual component, in the photographic carte-de-visite portraits of actresses, courtesans, and female criminals. Though scholars have typically understood sensational artworks to offer bodily thrills and forms of unmediated experience, my turn to photography uncovers how sensation was in fact a deeply mediated and insistently visual aesthetic. The tendency of the modern disciplines to focus tightly around particular objects, forms, and genres has obscured the actual cultural expression of nineteenth-century aesthetic phenomena, in media both high and low. In recovering the multimedia dimension, my account reflects the actual complexity of Victorian aesthetic ideas, observing their expression across a range of objects and formats.

These chapters take Victorian Britain as the epicenter of the nineteenth century’s new visual media. (And, within Britain, London inevitably dominates as a cultural producer, though other terrains make an appearance as well.) This centering on Britain is not coincidental: as the cauldron of the industrial revolution, Britain was a key innovator in the visual technologies that transformed techniques of printing and distribution. The British Empire, too, was a motor of visual culture production, from illustrated Bibles printed to evangelize in the colonies to illustrated newspapers reporting on imperial conquests abroad. Having said this, the book’s chapters also reflect the geographical porousness of the nineteenth-century picture world, as influential words and images flowed across borders without regard for national traditions. Gustave Doré, the French Bible illustrator, was more popular in England and America than he was at home in France. Oliver Wendell Holmes, the American photography theorist, modeled his account on British aesthetic categories and adopted a British-style imperial worldview. And aesthetic movements from realism to decadence began in France before taking on distinctive British formations. The aesthetic categories studied in the book, while particularized to Britain, speak with a resonance beyond Britain, characterizing the broader values of industrializing nations in the nineteenth century.

The chosen categories in Picture World are not random: each one speaks especially and uniquely to the nineteenth century. Raymond Williams, in Keywords, writes of how certain key vocabulary words register problems of meaning over time, waxing and waning in their usages, serving as palimpsests into a culture’s “ideas and values.” Certain prismatic keywords are prone to “innovation, obsolescence, specialization, extension, overlap, transfer,” or radical changes in their meanings across history.20 The categories studied in Picture World, while dominant in the nineteenth century, have each since been depreciated according to certain modernist or postmodernist sensibilities. The picturesque has been seen as derivative tourist kitsch; realism, as deceptive illusionism; illustration, as a descriptive mode fit for children’s books; character, as an outmoded investment in traditional concepts of personhood; sensation, as a crowd-pleasing, titillating formula; and decadence, as an elitist love of frivolous opulence. Each of these modes was in fact defined by the rise of mass culture in the nineteenth century, a popularization that in many ways still casts a shadow over them. My goal is not to recuperate these aesthetic modes—whose political attachments are often suspect and fantastical—but to study them for the light they shed on nineteenth-century thought, values, politics, and desires. Taken together, these keywords capture a penetrating snapshot of aesthetic values distant from us, but also, as the chapters pursue, still familiar in lingering ways.

The objects studied in Picture World could credibly be labeled as popular culture, mass culture, kitsch, or ephemera. I choose to use “mass culture” or “mass-produced, machine-made” objects as descriptors. Popular culture has often been taken to name the inexpensive items marketed to the working classes, while mass culture has been seen to target a more heterogeneous audience, mixing together different constituencies near the middle.21 Many of the new media studied here defy classification in terms of audience, since they could be purchased at a variety of price points. For example, consumers of limited means could view cheap stereocards using cardboard stereoscopes, while wealthier consumers could view glass stereographs using polished wood stereoscopes. This latter group might own grand cabinets holding thousands of views. Likewise, illustrated Bibles were sold inexpensively in parts with advertising wrappers, but wealthier families might choose to collect all of the parts into a single book, binding them in customized leather and displaying the resulting work on a fancy stand. Caricatures are the most low-cost items studied in this project; but even there, the first “Galleries of Comicalities” appeared in sporting newspapers targeting an audience of both working- and middle-class men. Generally speaking, the intimate objects of Victorian visual culture were consumed by bourgeois readers from high to low, families in or near the middle who could perhaps afford to pay sixpence for the Illustrated London News or who collected photographs of their friends and favorite celebrities in thick albums. Pictures often entailed some small amount of expense, which means that this book does not examine culture pitched to the most destitute of Victorian audiences. All of these objects appeared on the tides of visual fashion, obeying trends of intensity and obsolescence, as technological advances enabled the circulation of affordable objects to ever-greater numbers of people.

Mass culture has been targeted by a range of hostile critics and theorists over the years. In the mid-twentieth century, Adorno and Horkheimer attacked “the culture industry” for making art into a soulless capitalist enterprise, enslaving the masses from above. They preferred the Kantian object of autonomous high art, which promotes individualism by inspiring complicated acts of aesthetic judgment. By contrast, the new mass culture prefabricates experience for the viewer, making him (inevitably “him”) into a manipulable zombie: “[I]ndustry robs the individual of his function. Its prime service to the customer is to do his schematizing for him.” The critics denounce “aesthetic barbarity” in everything from Hollywood films to jazz music.22 Similarly, Clement Greenberg, in “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” (1939), disdained kitsch as the “rear-guard” of art; its origin in machine production served as a perfect metaphor for its consumers’ mechanistic mindlessness. “Kitsch is mechanical and operates by formulas. Kitsch is vicarious experience and faked sensations.”23 These critiques today seem slightly old-fashioned for their dismissive accounts of culture consumption—as though uneducated people, less at home within the rarified confines of high culture, are inherently ill-equipped to bring their own imaginative individualism to the objects they consume.

Scholars working with the theories of Michel Foucault have also seen visual culture as depriving modern subjects of agency, although for different reasons. Foucault theorizes modernity as a prison-house of visuality, in which subjects live under a constant state of surveillance and control. Images have played a key role in enforcing state hegemony—the mug-shot photograph, standardized in 1888, being a classic example.24 Foucault’s narrative has dominated the study of Victorian visual culture. Scholars have rightly observed the myriad ways that new visual technologies, especially photography, enforced a regime of power over Britain’s “others,” whether these were the impoverished, the racially marked, the foreign, the criminal, or the insane.25 Jonathan Crary’s Techniques of the Observer (1990) follows Foucault in arguing that new nineteenth-century devices such as stereoscopes functioned to discipline viewers into docile modern workers.26 Foucault’s dark link between vision and power belongs to a longer twentieth-century philosophical strain denigrating the visual sense for its hegemonic, imperial connotations, as Martin Jay has traced.27 For critics following in the wake of either Adorno or Foucault, visual culture is inherently reactionary, inhibiting social progress, enforcing hierarchies and solidifying the status quo.

While these approaches seem fitting for a certain subset of Victorian visual media—the photographic archive of empire seems especially stark—the objects considered in Picture World open onto more ambiguous terrain, and invite a different set of questions.28 Foucault’s singular model of correction and control ultimately feels too limiting to encompass the sheer variety and complexity of nineteenth-century media effects.29 I instead look to a multifaceted Victorian archive premised on qualities of desire, imagination, magic, and memory, all the fantastical elements harnessed by a rising consumerism and commodity culture. Notions of desire and fantasy are invoked here not in a psychoanalytic sense, and without any intention to discover universal imaginings based on innate qualities of mind. My understanding follows more in the line of Raymond Williams when he writes, in Marxism and Literature, that “all consciousness is social.” Williams chooses the word “feeling”—after rejecting “world-view” or “ideology”—to designate his sense of the individual’s intimate relationship to culture and its objects. “We are concerned,” he says, “with meanings and values as they are actively lived and felt.”30 It is in this sense that I approach the Victorian photograph collector or Bible owner, the maker of a cartoon scrapbook or the reader of an illustrated newspaper.

This method also takes it cue from Walter Benjamin, whose unfinished Arcades Project (1927–40) offers a vast archaeology of nineteenth-century Parisian visual culture. Benjamin takes objects as diverse as dolls, dioramas, and shopping arcades as the basis for philosophical meditations about work, aesthetics, and the industrial economy. He acknowledges the role played by capitalism, profit, inequality, and labor exploitation in the creation of the world of commodities. But he also finds meaningful purpose in delving into the appeal of those commodities, trying to understand the wellsprings of human desire and visual pleasure.31 For Benjamin these fantasies are often utopian, the “dream wish” of a society freed from capitalist and militaristic oppression, imagining forms of collectivism, equality, and abundance for all. While I don’t follow Benjamin into his more mystical flights, I share his mixed assessment of visual culture objects, deserving of both skepticism and abiding interest, as they serve as avenues into the profound cultural imaginary of the industrial age. All the contradictory elements of Victorian desire are bound up in these images: empire, the will to power, xenophobia, racism, religious stereotypes, patriarchy—crossed with curiosity, desire for contact, ambivalence, anxiety, exposure, eccentricity, transgression, and boundary-crossing of every kind. In studying the Victorian picture world, I take seriously the nineteenth-century desire to be elsewhere and otherwise.32

Nineteenth-century media studies have been diverse and divergent, and Picture World attaches itself to some scholarly strands, while pushing away from others. One dominant approach, pioneered by Friedrich Kittler, studies the era’s new machines and technologies enabling mass communications—from the typewriter, to the telegraph, to the telephone.33 By contrast, Picture World focuses on images rather than machines. The book contributes to what is now a growing field of humanistic media studies interested in questions of aesthetics, including histories of photography, illustration, periodicals, and other machine-produced modes of visual representation.34 This project was born out of the current academic interest in new media, one embracing “the relativity of the new,” in the words of Jussi Parikka.35 Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin, in Remediation: Understanding New Media (1999), describe how media transitions are never abrupt or definitive; new media constantly recycle or “remediate” the effects of the old, juxtaposing both familiar and novel ways of seeing and knowing. While Remediation focuses largely on contemporary media, its method serves as a powerful model for earlier media studies, especially those focusing on the nineteenth century, when mechanically reproduced objects often imitated the effects of earlier, singular, auratic artworks.36

This fact touches on one of Picture World’s recurring themes, as each chapter describes how Victorian visual culture courted forms of inauthenticity and fakery.37 From new iron-ribbed buildings clad in medieval-styled stonework, to mass-printed books decorated with Gothic tracery, to illustrated newspapers purporting to offer panoramic views of “the world”: examples abound here of deluded, fallacious visual accounts of space and time. Yet my analysis aims to exceed mere critique. I want to try to think deeply and generously about the fake and the fraudulent, eschewing a reflexive ironic stance. To be deluded is to be human, a state from which no one is excluded. The book thus locates sites of authentic feeling in some very inauthentic places, from clichéd destinations on the tourist track, to the faddish relics of celebrity culture, to the fabricated ancient world of an illustrated Bible. Each chapter traces out, in its conclusion, ways that our contemporary culture still pursues some of the same, recognizable desires through new media: the carte-de-visite album of photographic portraits anticipates Facebook, a modern-day book of faces; the search for the picturesque view in painting or photography anticipates the Instagram lifestyle, documenting a patently artificial, yet still pleasurable, assembly of picture-worthy “Kodak moments.” Postmodern theory, following Baudrillard, might suggest that these media effects of the past and the present are simulacra, hollow imitations offering nothing real or redeemable. Picture World resists this move. Feeling is where we find it, even when it is generated by objects that are patently manufactured, erroneous, or irrational.

The temporality within each chapter, moving from the nineteenth century to the twenty-first, suggests an analysis not quite linear. History is understood as a constellation rather than an arrow, following Walter Benjamin.38 The method is especially important for the objects studied in this book, which have often been lined up in a tidy row by scholars tracking the pre-history of cinema. To label an object as “pre-cinema” inherently privileges the more modern medium, predetermining our gaze to search only for qualities appropriately “cinematic.”39 Instead, I want to pause with the “present-ness” of an object, to use Baudelaire’s concept, entering imaginatively into the fantasies it furnishes. Stereoscopy thus appears not merely as a precursor to the cinema, but also as a technology looking back to Romanticism, expressing a nostalgic yearning for authentic feelings in nature. In fact, new technologies are not always necessarily futuristic or forward-facing, despite modern-day assumptions. Picture World avoids a teleological account, attending to the worldedness of each object, the unique formal and cultural effects immanent to an object’s particular history. I attempt to understand the object’s “essential quality of being present” (again, Baudelaire) for both the nineteenth century and for ourselves.

An understudied aspect of that presence, I argue here, is the human body. One crucial aim of this project is to re-corporealize the Victorian image-world, bringing the body back to an understanding of the illusion and consumption of images.40 This emphasis pushes against postmodern accounts that have taken Victorian media as early instantiations of the virtual, the abstract, and the immaterial—all qualities germane to an internet age. Postmodern media theory today emphasizes the posthuman, the self-as-machine, the automatized and decentered subject, aligning new technologies with an incipiently robotic humanity.41 In Picture World, however, I conclude that this theory is anachronistic to the deep embodiments of the nineteenth century. While the Victorian era is notorious for prudery and puritanical attitudes toward the body, these viewpoints coexisted with an overwhelming and almost delirious investment in physical life and physical pleasure. All of the media objects studied in this book drew upon bodily pleasures for their appeal. These carnalities were usually packaged within a safely educational or moralistic framework. The stereocard is a perfect example: on one side, the doubled photograph generated a three-dimensional illusion—voyeuristic, tactile, presenting the scene in fetishistic detail. On the card’s flip side, the printed label provided salient historical and ethnographic factoids, quotes from a local authority, or a few lines from Wordsworth or Scott. Though the stereoscope was deemed safe for use by women and children, its educational bent did not obviate its grounding in the body, its vertiginous pleasures based in the physical facts of vision and sensation. Victorian culture today is stereotyped for its ascetic disavowals of corporeality, but the nineteenth-century explosion of commodity culture points in a different direction, as all of the objects I study proffered embodied pleasures, from cartes de visite portraits of courtesans and opera singers to the violent, nudity-laced illustrations of Gustave Doré’s illustrated Bible.

Critiques of mass culture and critiques of Victorian media technologies in fact share a striking commonality. All of these propose that mass media usage entails a form of passivity, mindlessness, or evacuated agency. Friedrich Kittler writes that the advent of the typewriter, with its forms of “mechanized writing,” brought to an end the “dream of writing as the expression of individuals or the trace of bodies.”42 Kittler uses media history to attack Romanticism’s exquisite humanistic subject, tracking instead the nineteenth century’s techno-inspired states of human automatism. Jonathan Crary, in Suspensions of Perception (1999), aligns mass culture with “states of distraction, reverie, dissociation, and trance.”43 Susan Zieger assigns a more positive valence to mass culture’s states of “reverie,” “enchantment,” and “daydreaming,” which occur beyond “the rational mind taken up with egoistic cognition.”44 But all of these assessments ultimately resonate with Horkheimer and Adorno’s culture-dazed zombies, aligning mass culture with a depletion of agency. For scholars trained in forms of aesthetic high culture, mass-cultural items or technologies are often consigned to a denigrated realm of “guilty pleasures.” This book takes a different view. I suggest that culture consumption does not take place away from the self, or beyond identity, merely in off-hours or apart from truly important matters. The very concept of ephemera, locating certain forms of culture at the margins, is incommensurate with its import in conjuring aspects of self and identity. We are often purposeful in choosing our mass-produced worlds, in whatever forms these materialize. Victorian users actively collected photographic cartes de visite, carefully arranging the portraits in albums to mirror the hierarchical world they occupied. In this, they anticipated the large number of people today who spend hours arranging and presenting identity on social media. The Kantian bias of humanities scholars toward complicated, autonomous artworks is perhaps incongruous with the way that many of us actually live our lives, surfing the net, browsing, collecting, studying, arranging, digesting, assembling many of the raw materials of the self.

*

Picture World makes an idiosyncratic choice by compressing many different visual media into a single study. In a university culture inviting hyper-specialization, the book goes against the grain by opening onto a series of worlds, expansive and investigatory rather than sharply definitive. I cannot make any claims to comprehensiveness: a complete account of the Victorian mass-produced image would overfill the bounds of any reasonably sized study. Instead, each chapter offers a methodology, a suggestive pairing of object and concept, an investigation into a rich world that might be developed by other scholars in future studies.

The book progresses in a loosely historical sequence. The first chapter examines notions of “character,” which, in nineteenth-century studies, has often connoted the rounded, deep, psychological self of the realist novel. Yet the chapter traces an alternative history by looking to caricature, in some of the earliest comics (“Galleries of Comicalities”) appearing in sporting newspapers in the 1830s. These caricatures portrayed an idea of character that was grotesque, masculinist, and brilliantly exteriorized, especially in depictions of “the cockney,” the urban mischief-man whose subversive masculinity hovered at the borderlands of class, respectability, and propriety. Cartoons featuring the cockney often combined crude racism and misogyny with anti-authoritarian, carnivalesque humor. Character in these images manifested in grotesque renderings of bodies deformed by the economic pressures of the new urban economy. Cockney male figures expressed a wild, mock-violent energy, giving voice to some of the explosive frustration felt by working- and lower-middle-class men after the failures of the Reform Bill of 1832. The chapter shows how Reform-era visual culture was deeply influenced by the young Charles Dickens, whose earliest themes were in turn taken from an extant caricature culture. With roots in sporting cartoons, The Pickwick Papers (1836–7) mocks the “great man” theory of character while celebrating the urban male rogue, Sam Weller. In the character dynamism of post-Reform London in the 1830s, grotesque, ingenious physicality gave expression to fundamental instabilities of social class and economic precarity. Caricature’s ephemeral images undercut any classical stability of self, producing an idea of character that was messy, funny, rebellious, grotesque, and improper.

The second chapter turns to the complex topic of “realism,” which scholars have typically limned using novels, paintings, or photography. But I expand our notion of the style by turning to the illustrated newspaper. The hand-drawn, hand-engraved images of this Victorian new medium hovered in the borderland between fact-based journalism and illusionistic art. The chapter focuses on reportage of the Crimean War (1853–6), often called the first “media war”: this was the first international conflict to be documented by independent war correspondents, on-the-spot sketch artists, photographers, and illustrated newspapers at home. New media technologies allowed the British public to see the war as an immediate reality, especially in journalistic exposés of the war’s mismanagement. The chapter argues that the Crimean War prompted a representational crisis demanding a new visual vocabulary, one that pictorial journalists addressed using four kinds of reality effects. I designate these effects as the descriptive, the authentic, the everyday, and the plausible, and I track them through the Crimean War’s distinctive journalistic imagery, including “the Valley of Death,” scenes in the trenches, the battle’s aftermath, the war reporter, the amputee, and the nurse. This expanded realist history links new journalistic practices to the new realist novel, focusing on George Eliot’s Adam Bede (1859), published just a few years after the war, and famous for its realist manifesto. The decade witnessing Britain’s first dedicated war reportage also saw the first use of “realism” as a term of literary criticism, showing how the mid-century realist aesthetic emerged from transforming representational norms across media and genres. The chapter’s conclusion pursues mid-Victorian reality effects into a contemporary BBC war documentary series, Our War (2011–12), arriving at a sense of realism’s moral complexity: the style might work to highlight the world’s political problems, even while its techniques serve to affirm the established status quo.

Chapter 3 looks to “illustration,” a crucial keyword in Victorian aesthetics, reflecting the rise and golden age of the mass-printed illustrated book. I turn to the vast but understudied body of religious illustrated books. The illustrated Bible, newly affordable and profusely illustrated, typically served as the centerpiece of the Victorian parlor. An illustrated Bible amplified all of the aesthetic ambiguity surrounding illustration more broadly. The age-old subject matter—images of Moses and Esther, Jesus and Mary—evoked an aura of pre-industrial authenticity and artistry, even while religious publishing thrived on new media networks and new kinds of print technologies. While the concept of illustration might imply that images are subordinated to a controlling text, the illustrated Bible—likely the single most ubiquitous Victorian illustrated book—proposed a different view. Illustration here served as a form of world-building, presenting a fantastical yet empiricist vision that drew upon recent discoveries in history and archaeology. Bible illustrators worked to make the Bible “British,” despite its Middle-Eastern roots, and in doing so upended some typical Victorian markers of identity. British artists created a complicated world picture in Bible illustrations by leaping across time and space, encompassing dualities of East and West, ancient and modern, Jewish and Christian, patriarchal and democratic, magical and rational, and self and other. The chapter considers Bible illustrations by Gustave Doré and John Everett Millais, among others, as well as the depictions of Jewish customs by the Pre-Raphaelite artist Simeon Solomon. I conclude that the Victorian illustrated Bible created a template for the modern mass-marketed religious experience, from epic Hollywood Bible movies to biblical theme parks.

Chapters 4 and 5 turn to the quintessential new visual technology of the nineteenth century, photography. Each chapter looks to a mass-produced type of photography that has been less studied by art history. In Chapter 4, I show how the emergence of tremendously popular cartes de visite, small photographic portraits, contributed to the so-called “sensation” craze of the 1860s. Scholars have largely focused on sensation novels, known for their lurid crime plotlines and outrageous villainesses. Yet, as the chapter shows, sensation was a multimedia phenomenon that encompassed both novels and photographs. More than merely a literary aesthetic, sensation was in fact was a broader response to new forms of spectacular female celebrity—as seen in the wild popularity of photo portraits of actresses, opera divas, prostitutes, even Queen Victoria, all wielding unprecedented cultural power via their pictorial publicity. The carte-de-visite medium, circulating women’s portrait photographs in millions of paper copies, perfectly encapsulated sensation’s dialectic between embodiment and mediation, and between individual celebrity and the democratized mass. These themes drive the plots of sensation novels, especially Wilkie Collins’s The Woman in White and M. E. Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret. The chapter ultimately pursues imagery of the “technosexual woman” into the present day. A 1997 London art show titled “Sensation” strikingly recapitulated 1860s themes with its spectacular display of erotic, mediatized female figures. I conclude that carte-de-visite culture can claim many new-media descendants, from Facebook’s digitized book of faces to queens and porn stars appearing side-by-side in the same tabloid magazines.

Most middle-class Victorian parlors would have contained an illustrated family Bible, an album of photographic cartes, and, as Chapter 5 explores, a stereoscope with which to view a collection of stereographic cards. When viewers peeped into the device, the stereoview’s dual photographs leapt into startling three-dimensionality, making the stereoscope the perfect vehicle for virtual travel. Destinations ranged from Egypt to Niagara Falls. Scholars have interpreted stereoviews either as avatars of scientific realism or as forbears of a postmodern, human–machine interface (especially in the influential work of Jonathan Crary). Yet the chapter diverges from both of these accounts by seeing the stereoview as extending the mode of the picturesque, the high-art landscape aesthetic of the eighteenth century. The picturesque featured artful scenes in nature, but it was also deeply imbricated in new visual technologies, with devices that ranged from the Claude glass, to the camera obscura, to the stereoscope. Though postmodern accounts have taken the stereoscope to inaugurate abstract, even robotic sensibilities, I show how the device actually worked to remediate Romantic ideals: it was a kind of organic machine and prosthesis attached to the spectator’s body that enabled an extraordinary, humanistic experience. The chapter pursues the stereoscope’s embodied picturesque from Wordsworth’s Tintern Abbey to Ruskin’s Gothic cathedral. I show how the visual technology enabled corporeal fantasies across space and time, reflecting an imperial power dynamic of global visual mastery. The conclusion finds that the modern 3-D film also reproduces some of the same fantasies, as seen in James Cameron’s blockbuster Avatar (2009): here, too, a new, organic technology offers a heightened sensory experience that enables a natural pathway back to an authentic self.

Chapter 6 moves to the confounding artistry of fin-de-siècle advertising posters. Posters were mass-produced, disposable, and advertised commodities like cocoa and the circus. But they also starred in major art exhibitions in London and Paris and were attacked for their “decadent,” avant-garde styles. Our usual idea of the Decadent movement in the 1890s connotes literary authors like Oscar Wilde and Joris-Karl Huysmans, spinning visions of an aristocratic, countercultural lifestyle. Yet decadence, as the chapter shows, also manifested in visual media, and was reacting to the rise of a middle-class consumer culture of which it was very much a part. The graphic designer Aubrey Beardsley created advertising posters using decadent visual styles, shocking critics even while successfully marketing consumer goods. More broadly, pictorial posters became metaphysical symbols that were seen to embody the rise of commercial modernity. This turn was celebrated by decadent theorists but attacked by conservative critics, who saw the advent of multicolored posters blanketing city spaces as a sign of imminent cultural decline. Pictorial posters adopted new visual methods of surrealism and mysterious indirection that reflected late-Victorian theories of self and mind. I conclude by tracing a line from Aubrey Beardsley to another graphic designer, Andy Warhol, whose advertisements for Absolut Vodka recapitulated the transgressive decadent embrace of commodity culture. Warhol’s poster arts show how the combination of high and low culture, packaged in striking visual form and communicated with an ironic tone, still works as a modern-day advertising technique—pointing to, more broadly, the way that avant-garde shock strategies are still called upon as persuasive commercial forces.

The book’s conclusion examines the early cinema of the 1890s, to look at the ways it invoked and transformed earlier Victorian visual traditions. The earliest films were shown at fairgrounds and mass entertainment venues, and thus differ from the more parlor-oriented objects studied in this book. Yet all of the visual culture items found in the Victorian parlor opened onto “the world” and public life in fantastical and phantasmagoric ways. Seen from this perspective, the eye-tricking pleasures of early cinema were a logical extension of previous mass visual phenomena. No wonder that some of the earliest films imagined the nineteenth-century picture-world come magically to life, from enchanted albums, to animated caricatures, to figures in advertising posters throwing foodstuffs at passersby. The Victorian picture world contained a visual storehouse of fantasy and desire, whose legacies extended into the twentieth century and beyond.

Picture World: Image, Aesthetics, and Victorian New Media. Rachel Teukolsky, Oxford University Press (2020). © Rachel Teukolsky.

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198859734.001.0001