Chapter 14

Bird Communities

Russell S. Greenberg

Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center

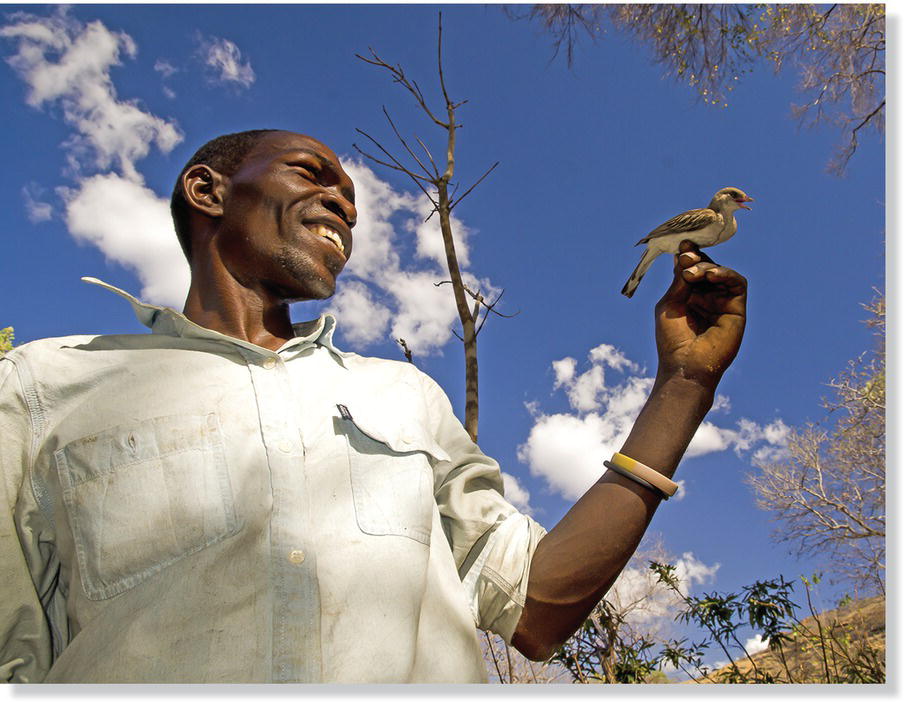

(Photograph by Esther J. Horwich.)

On a walk through any habitat you might encounter a single chirping songbird, large flocks of a single species, or a vibrant diversity of birds of many species. This extravagant variation in bird diversity naturally leads to questions such as why are there so many bird species in some places and so few in others? How do different assemblages of species interact? Do different groups of birds compete? Do they cooperate? How do birds interact with other aspects of their environment?

There are many definitions of biological communities and many approaches to studying them. A typical definition of a biological community is “any group of organisms belonging to a number of different species that co‐occur in the same habitat or area and interact through trophic and spatial relationships” (Lincoln et al. 1998). Note that this definition does not include any particular taxonomic limits, and birds are just one component of any group of potentially interacting organisms. However, some biologists argue that the groups we term communities are artificial human constructs (Box 14.01). The term community includes only a subset of the organisms that influence the lives of birds, so the term species assemblage is often preferred when referring to only the avian component of a community. Moreover, biological communities are often discussed without the numerous non‐biological factors that affect populations, such as climate and other environmental variables. An ecosystem is perhaps a more familiar and inclusive term that describes both the collection of species and physical environment in which they interact.

It is often challenging to delineate the most appropriate scale for defining a particular community, because the distributions of individual bird species often change from season to season and from place to place. Furthermore, the number of bird species that occur within an assemblage changes relative to the size of the area that is sampled. Community ecologists therefore usually adopt a pragmatic definition of the community they study that reflects the specific interactions that are of interest to that particular researcher. Despite conflicts in how we formally define a community, we focus in this chapter on the central theme of avian community ecology: the interactions among different bird species.

14.1 Classifying bird species assemblages

Scientists who study plants have been particularly concerned about developing rigorous ways of defining communities, and avian community ecologists often rely upon the classifications developed by botanists, with the proviso that major physiographic features—such as bodies of water—can form the basis for additional types of avian communities.

Biomes are the broadest way of dividing the terrestrial parts of the globe into regions that differ in the prevailing climax vegetation type (such as tropical/subtropical, temperate, dry, and polar/montane, as well as aquatic). Biomes are usually defined by structure rather than species so that similar habitats in two different regions can be grouped together. The major terrestrial biomes, as defined by the World Wildlife Fund’s current dataset of 825 global ecoregions, include: flooded grasslands and savannas; coniferous forests; dry broadleaf forests; grasslands, savannas, and shrublands; moist broadleaf forests; broadleaf and mixed forests, deserts and xeric shrublands; Mediterranean forests, woodlands, and scrub; boreal forests/taiga; rock and ice; and tundra. As they overlap with terrestrial ecosystems, lakes and mangroves are included as well. Some of these biome types repeat under broader categories (such as coniferous forests, which occur in both tropical and temperate climates) (Fig. 14.01).

Biome: an ecological community of organisms that occurs across a broad geographic region defined by its location, biogeographic history, and climate.

Fig. 14.01 Major biomes of the world. This map depicts the currently recognized terrestrial biomes, based on biodiversity patterns for 825 ecoregions.

(© 2012 The Trustees of Columbia University in the City of New York. CC‐BY‐3.0.)

For example, a characteristically scrubby type of vegetation occurs in areas with climates of cool, moist winters and hot, dry summers. This plant community is dominated by bushy, drought‐resistant, aromatic species that are well adapted to survive despite frequent fires. Although it has different names in different places, this Mediterranean scrub biome occurs across the globe, including the west coast of California, USA (where it is termed chaparral), coastal Chile (matorral), the area surrounding the Mediterranean Sea (maquis), the coast of South Africa (fynbos), and the southeast coast of Australia (kwongan). These distant regions all host structurally similar plant communities, but they are embedded in continents with very different bird species, representing different families and orders. No bird species is found across similar plant communities around the globe; instead, the different birds in these areas often have converged in many aspects of their biology. For example, in a classic comparison of the birds of these habitats in Chile and California, Martin Cody (1974) found that the two areas were very similar both in their overall number of bird species and in the relative abundances of the particular birds that filled different ecological roles, such as foliage gleaners, nectarivores, ground feeders, sallying flycatchers, and so on. Cody went so far as to identify several species that independently evolved such similar ecologies that they could be considered “replacement” species for each other in these two Mediterranean scrub habitats. These comparisons indicate that bird assemblages can converge to become quite similar in ecology when faced with similar environmental conditions.

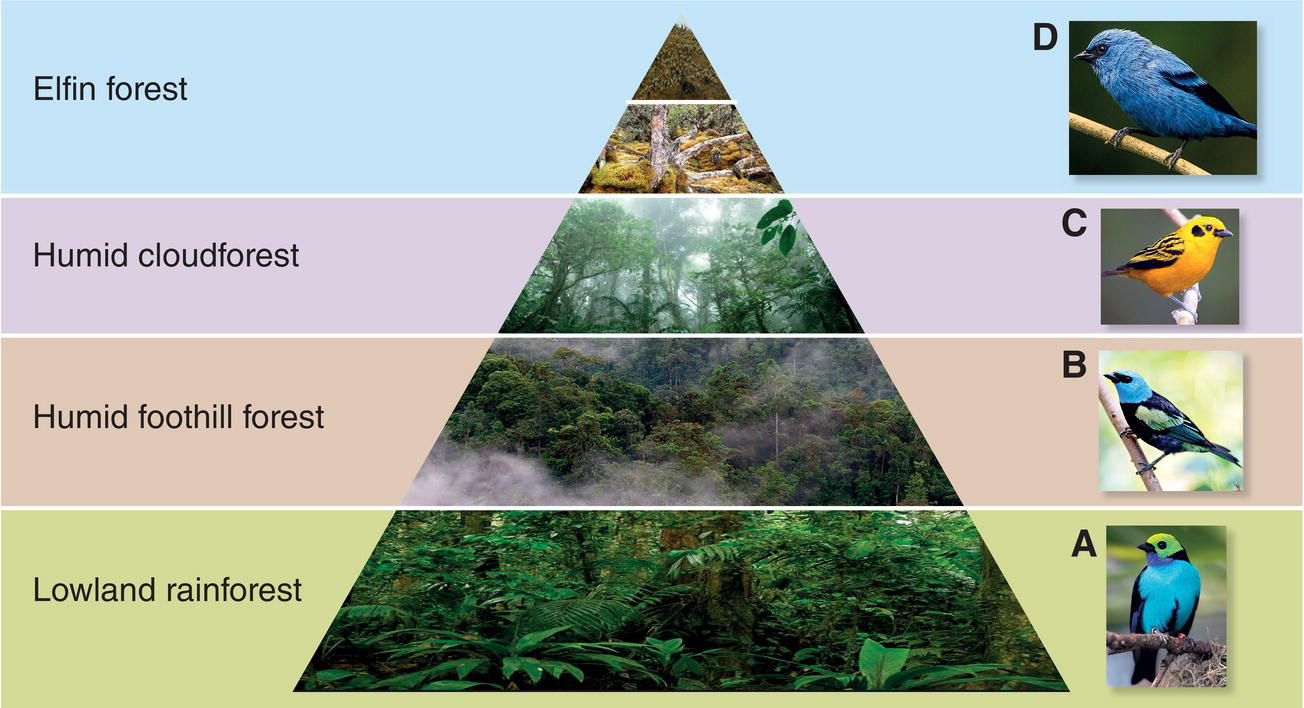

A different habitat classification system is generally used for mountainous regions, where major climate‐driven changes occur over a range of elevations. Life zones recognize these transitions of plant and animal species encountered along an elevational gradient. For example, in tropical regions with high rainfall, the life zones you encounter as you travel up a mountain often change from tall tropical forests at low elevations to stunted and moss‐covered cloudforests at higher elevations, with treeless habitats at the highest elevations (Fig. 14.02). In some cases, bird communities track these elevational life zones closely, with the bird assemblage changing in composition at ecotones, the boundaries between two successive life zone habitats. Elsewhere, bird assemblages may also be sensitive to elevation even in the absence of abrupt changes in habitat types. For example, bird surveys across a range of elevations in the Udzungwa Mountains of Tanzania found that most species fell within one of two distinct assemblages (with a notable switch at 1200 meters) despite apparently similar habitat across the gradient (Romdal and Rahbek 2009) (Fig. 14.03).

Fig. 14.02 Life zones. In the Ecuadorian Andes, different tanager species occupy distinct habitat‐ and climate‐driven strata along an elevation gradient: (A) Paradise Tanagers (Tangara chilensis) in lowland rainforest, (B) Blue‐necked Tanagers (Tangara cyanicollis) in humid foothill forest, (C) Golden Tanagers (Tangara arthus) in humid cloudforest, and (D) Blue‐and‐black Tanagers (Tangara vassorii) in high‐elevation elfin forest.

(Photographs by: A, Bill Fleites; B, Timothy Wong; C, Peter Hawrylyshyn; D, Francesco Veronesi; pyramid habitats, Alexandra Class Freeman.)

Fig. 14.03 Community assembly shifts along a montane elevational gradient. Each horizontal bar represents a different bird species surveyed on a mountain slope in Tanzania. Bars are ordered by the midpoint of each species’ elevational range. Black bars represent species with ranges that occur above or below 1200 meters at least 75% of the time. These species belong to either the highland (blue box) or lowland (red box) community. Black bars represent widespread species that do not distinctly belong to either assembly. Richness (number of species) recorded at each elevation is denoted below. In this case, complex dynamics among species appear to influence community assembly more than do sharp environmental ecotones.

(From Romdal and Rahbek 2009. Reproduced with permission from John Wiley and Sons.)

In other places, bird species have even more subtle and variable distributions across elevations. Elevational zonation, a pattern in which related bird species replace one other at different bands of elevation, is particularly common in tropical regions. This type of distribution pattern helps explain why tropical regions with extensive topography have notably high diversities of birds—and why birders wishing to see the largest number of species within these regions need to divide their time across a range of elevations. In some cases, elevational replacement species meet one another only in a very narrow band that does not correspond with any obvious habitat change. Here, competition and aggression between the species may be the main forces keeping them from overlapping, as seen in a group of thrush species in Costa Rica. Experiments in which researchers played recordings of the songs of these species and then recorded the birds’ responses show an intriguing pattern: each species is more aggressive towards the song of the other species at locations nearest their shared elevational boundary, suggesting that aggression plays a direct role in keeping the species separated into distinct elevational zones (Jankowski et al. 2010).

14.2 Ways of describing communities

14.2.1 Species diversity

Scientists and birders alike know that the number of bird species found in a particular habitat or region is a simple but useful number. Species diversity can be looked at in two ways, depending on whether we prioritize just tallying the total number of species present or also consider their relative abundances. If we think of a particular bird species assemblage as a jar of jelly beans, and we want to buy the jar with the most flavors, we could empty the jar completely and simply determine the total number of different kinds. Applied to birds, this count would represent species richness, the number of different species present. However, we might find a jar that has a variety of different flavors but a preponderance of lemon‐flavored jelly beans; if we grab a handful, the chances of getting more than a couple of types of beans is small, because there are so many yellow ones. The chance of getting the most types of beans in a jar, or bird species in a particular survey, depends both on the total number of different types/species and their pattern of relative abundance. This combination of bird community attributes—the number of species plus their relative abundances—is what most avian ecologists consider when they refer to species diversity.

14.2.2 Patterns of species abundance and estimating species richness

In practice, species richness almost always grows with increased effort on the part of the people searching an area, and with a greater number of individual birds identified. A plot with the number of species detected on the y‐axis and the number of survey samples or individuals observed on the x‐axis is known as a species accumulation curve (Fig. 14.04). Most species accumulation curves first rise sharply, then rise more gradually, and finally level off at a maximum number known as the asymptote. On one extreme, assemblages with few but common species will reach an asymptotic number of species rapidly. In assemblages with many species, particularly many rare or transient species, the accumulation curve will be long and gradual, and tremendous surveying effort may be needed to reach the asymptote. Because most bird surveys are not complete but instead provide a snapshot of the total number of possible species, a simple comparison of species totals may be very misleading. For example, an equivalent survey effort may produce a similar species total for two assemblages, but in one assemblage all the species present were sampled, whereas in the other only a fraction of the total possible species was detected in the same amount of time. Similarly, if two survey sites differ in the overall abundance of birds of different species, a similar survey effort will result in a higher species list for the habitat that contains more birds. Statistical programs now are available that estimate the asymptotic species richness of an assemblage from different kinds of field surveys.

Fig. 14.04 Species accumulation curves. More species are discovered as sampling effort (hours) increases, but discovery rate decreases with increased effort. Researchers can approximate species richness in an area by fitting the start of a species accumulation curve to a mathematical function. For areas with many rare species (blue plot), the curve has a long, gradually increasing tail; this represents the considerable sampling effort necessary to discover most of a region’s species. For areas with relatively few and abundant species (red plot), the curve does a better job of rapidly approximating species numbers.

(© Cornell Lab of Ornithology.)

14.2.3 Species–area curves

It is a general truism that larger areas contain more bird species. The richness of bird species seen or heard in any survey is therefore always highly dependent on the area surveyed. A graph of the number of species found in a survey versus the area being surveyed is termed a species–area plot. Curves based on increasing sampling areas—from a hectare to a square kilometer to 100 square kilometers to thousands of square kilometers—nearly always show a steady increase in species totals because more habitats are sampled and more local and rare bird species are detected.

Species–area relationships are most clearly visible in archipelagos of islands of different sizes, which share a few nearly universal patterns. First, islands generally have fewer species than areas of similar size on a nearby continent. The number of species on an island also is strongly related to its distance from the mainland (which presumably affects how readily birds can colonize the island) and the size of the island. Avian ecologists have surveyed the number of bird species on most of the world’s islands and have found that, in general, the number of species roughly doubles with every 10‐fold increase in island area. For example, within the Lesser Antilles Archipelago in the Caribbean, the relatively small island of St. Kitts (168 square kilometers) has 37 resident breeding bird species, whereas the larger nearby island of Guadeloupe (1713 square kilometers) has 72 species (Ricklefs and Bermingham 2008).

The reasons that small islands support fewer bird species than do larger islands are similar to those that cause small areas on a continent to have fewer birds than larger continental areas, with one twist: for many species, the small population size that can be supported on a small island, coupled with the lack of other places to go when local conditions become stressful, leads to higher extinction rates on islands. The Theory of Island Biogeography developed by Robert MacArthur and E. O. Wilson (1967) was groundbreaking when it was introduced because it provided an elegantly simple model for predicting the number of species on islands based on an equilibrium between colonization rates (which decline with distance from a source of new species, such as a nearby continent) and extinction rates (which decline with increasing island size, since large islands can support larger bird populations than smaller islands). Under this simple theory, we would expect to see the greatest avian diversity on large islands that are close to a continent or other source of potential colonists, and the lowest diversity on small, remote islets (Fig. 14.05).

Fig. 14.05 Theory of Island Biogeography. MacArthur and Wilson observed that (A) distance from a source population and (B) area are both good predictors of species richness. (C) Gradual species loss on Barro Colorado Island, an island in the Panama Canal that was first surrounded by rising waters in 1913, provides an opportunity for biologists to test the MacArthur–Wilson model.

(A and B, from Simberloff 1974. Reproduced with permission from Annual Reviews. C, courtesy of Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute.)

Similarly strong relationships between habitat size and bird species richness occur in other settings where either natural or man‐made habitat “islands” occur (Chapter 15). For example, a team of ornithologists working in central Panama surveyed the bird species in 18 forest fragments of varying sizes, from 21 to more than 15,000 hectares (Robinson et al. 2004). As expected under the island biogeography theory, they found a strong relationship between forest patch size and bird species richness: the smallest fragment supported only 10 species of forest‐dependent birds, whereas the most expansive sites contained more than 150 such species.

14.2.4 Understanding abundance and rarity

Most bird assemblages have a few common (dominant) species and many uncommon to rare species. Assemblages differ considerably in the number of rare species they contain, but, particularly in the tropics, some avian assemblages contain a large number of individually rare species. For example, Peter Pearman (2002) used mist nets to survey the understory bird community on 23 small study plots in the Amazonian forest of Ecuador. Of the 93 total species he captured, only the nine most common birds were found at more than half of the plots, whereas 39 rare species were captured only on one or two plots.

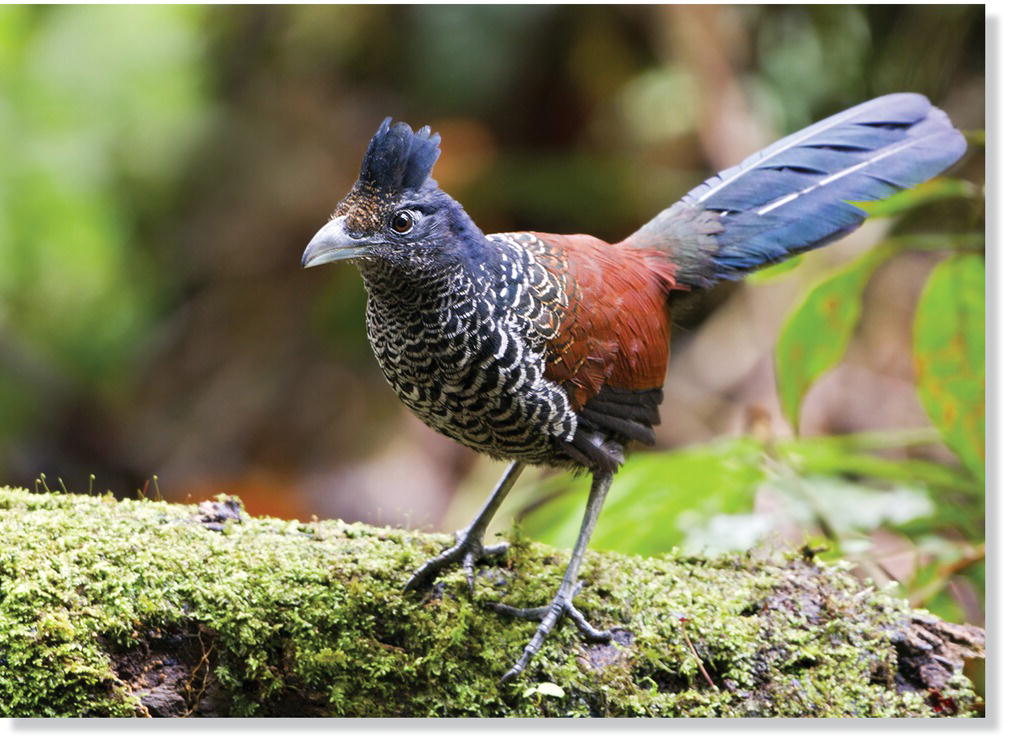

Determining the factors that explain why some species are rare (Fig. 14.06) is both an interesting academic challenge and important for conserving rare species. Reasons that a species might be rare in a particular assemblage include: (1) the site is at the edge of the species’ range or the site is in suboptimal habitat, but the species is common elsewhere in suitable locations; (2) the species is large bodied or high on the food chain, and hence few individuals can persist in any one area; (3) the species has specialized habitat requirements; (4) the species has suffered from human activities that have reduced its abundance; (5) the species is at a low point in a long‐term population cycle; or (6) the species is globally rare without any identifiable limiting factors.

Fig. 14.06 A notably rare neotropical forest bird. Factors thought to influence the rarity of the Banded Ground‐Cuckoo (Neomorphus radiolosus) include low fecundity, particular habitat requirements (intact, primary, humid, mid‐elevation tropical forest), dependence on large prey, and hunting by humans. Much of its original range has been destroyed via logging and habitat alteration.

(Photograph by Glenn Bartley.)

14.2.5 Three kinds of diversity

Community ecologists have defined three types of diversity that are easily applied to bird assemblages. Alpha diversity is the count of the number of species present in a single habitat or location. The alpha diversity of birds is most often assessed using a simple species list, a species diversity index, or a more sophisticated estimate of the number of species present that factors in the amount of effort put into the survey. Beta diversity is the additional accumulation of species that occurs across different habitats or sites within a region. The beta diversity of birds is most often estimated using indices that focus on the turnover of species among habitats. Gamma diversity is the total number of species within a region, summing together the different birds found at any site or any habitat. It is most commonly based on a simple regional species list.

Patterns of alpha diversity can be explored and compared using standardized censuses focused on single habitat types. For example, small plots of forest in eastern North America generally support 18–23 bird species, whereas similarly sized forest plots in western North America have only 15–16 species. However, the overall abundance of birds on these plots is quite similar. Marshes support few species (averaging 8.5 per site) but have among the highest total abundances, and western riparian woodlands support both a large number of species (21) and the highest overall abundances of birds of all North American habitats.

A return to the comparison of the landbirds of Chile and the California coast (USA) shows how the three types of diversity interact. Although far apart, these two regions are strikingly similar in their physical geography and climate: both are isolated from the rest of their continent by a long range of tall mountains, both have substantial areas of desert, and both have coastal regions with a similar Mediterranean‐type climate. The total species lists (gamma diversity) of breeding landbirds in these regions are also very similar, as are the alpha diversities of individual habitats within them. However, the species turnover between habitats is much lower in Chile than in coastal California; that is, individual species in Chile are less habitat‐specific, and thus different habitats in that region tend to share more of the same species. Chile’s overall diversity is comparable with that of coastal California because Chile’s species are more geographically restricted, so there are more subregions with large differences in the composition of their species.

14.3 Patterns of species diversity

Species richness follows some well‐documented worldwide patterns often referred to as species diversity gradients. Overall, bird species richness decreases markedly with distance from the equator, at higher elevations in mountains, and on smaller and more isolated islands and land masses.

14.3.1 Latitudinal gradients

Overall, bird species richness is much greater in the tropics than in the temperate zone and Arctic (Box 14.02). For example, Colombia holds the record for the country with the greatest number of birds: with nearly 1900 species, it has about twice the number of species as the USA and Canada combined. Likewise, Cameroon has a species list of more than 900 birds, whereas Sweden, a country with a similar land area, has only about 480 (Fig. 14.07).

Fig. 14.07 Avian species richness around the world. This heat map depicts bird diversity with a color gradient: warm colors for high richness and cool colors for low (less than 10 species in dark blue areas, around 150 in lime green areas, and over 950 in deep red).

(From Orme et al. 2006. © 2006 Orme et al. CC‐BY‐2.5.)

The general latitudinal gradient in species diversity seen in birds is found in many other groups of organisms, including mammals, trees, and ants (to name a few), but it is not universal. Seabirds, for example, tend to reach their peak diversity at mid‐latitudes. Likewise, many shorebirds and other species that thrive in coastal and estuarine habitats tend to reach their breeding season peak diversity in the far north and their peak winter diversity at mid‐latitudes. Despite these exceptions, the increase in diversity towards the tropics is dramatic in most avian groups, and particularly pronounced in forested habitats.

Many hypotheses have been advanced to explain the greater species richness in the tropics. These ideas can be divided into two general groups: (1) those that propose long‐term evolutionary explanations for how the processes of speciation, extinction, and dispersal generate higher tropical diversities; and (2) those that propose ecological explanations for how tropical habitats can allow more species to coexist at any one time. These explanations are not mutually exclusive, because many of these evolutionary and ecological factors likely act in concert to increase tropical diversity.

Among the evolutionary explanations, one possibility is that tropical environments have been more stable over the past several million years, in comparison with the more dramatic climatic shifts experienced by temperate regions during the glacial cycles of the Pleistocene. This stability of tropical habitats might reduce the extinction rates of the birds in these areas. However, the stability of the tropics is only relative: the tropics, too, have experienced large swings in precipitation and even in temperature. Under cooler, drier conditions, when savanna prevailed in many more tropical areas than it does today, remnant regions of forest (termed Pleistocene refugia) remained intact. Because these forested refugia were isolated from one another, they may have allowed many tropical bird populations to start the process of speciation (Chapter 3). The Pleistocene refugia hypothesis was popular for several decades in the late 1900s, but it has fallen somewhat out of favor as the prime driver of high tropical bird diversity, primarily because DNA‐based estimates of the ages of tropical birds often show that closely related species began to split long before the Pleistocene.

Some researchers have argued instead that speciation may proceed more rapidly in the tropics, perhaps because the sedentary lifestyle of many tropical birds leads to reduced dispersal and hence reduced gene flow (which tends to work against species formation). Indeed, experiments have shown that many tropical forest species, particularly understory species, are hesitant to cross even the smallest barriers (such as rivers); this tendency also might promote their speciation (Moore et al. 2008). In contrast, some genetic studies have countered this hypothesis by demonstrating that avian speciation sometimes occurs faster in temperate zone groups of birds. Tropical diversity may still be higher if extinction rates are also disproportionally higher in the temperate zone, so that tropical diversity builds up relative to temperate environments where there is more turnover of species over time (Weir and Schluter 2007).

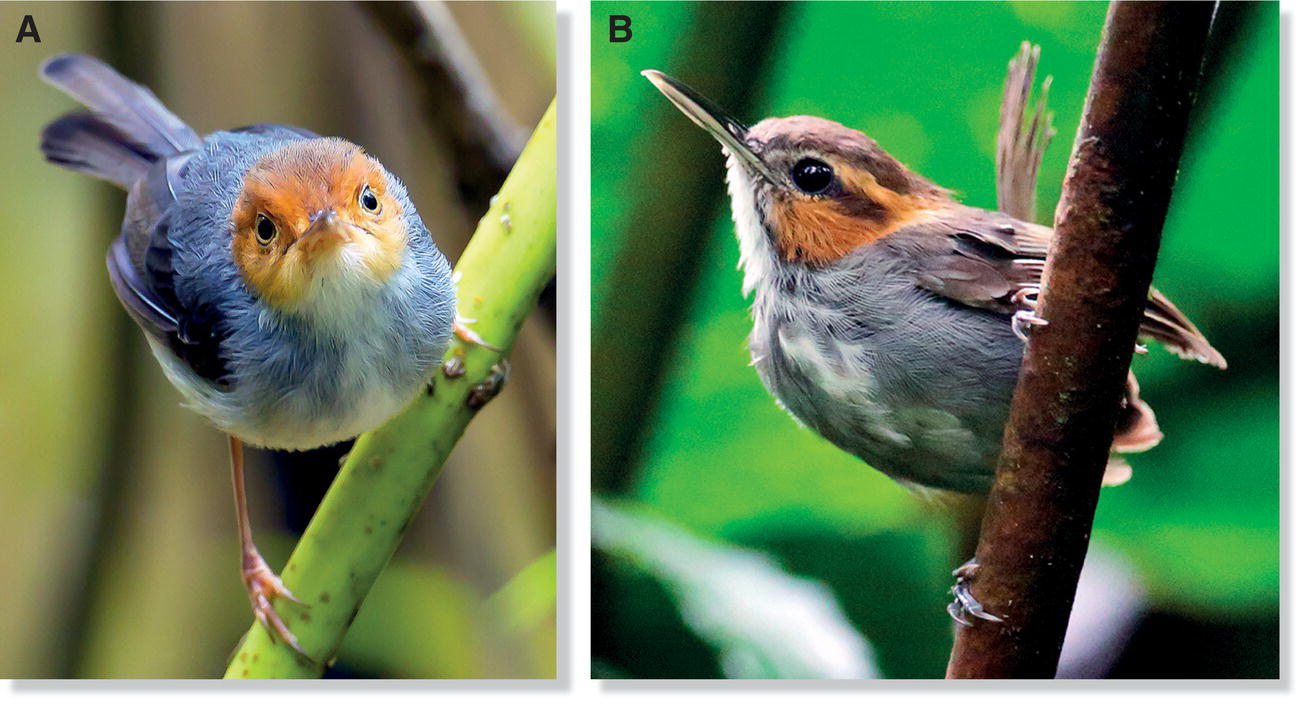

These evolutionary considerations can explain how a greater number of species might occur in a tropical region, but they do not provide insights into how so many species can coexist in a single habitat or at a single site. Several ecological factors in tropical forests seem to contribute to their high local diversities of birds. First, the physical structure of a tropical forest is highly complex. The high diversity of forest tree species contributes to this complexity, but perhaps even more important is the abundance and diversity of epiphytic plants and lianas. Entire groups of bird species specialize on microhabitats that are present only in the tropics, such as the deep vine tangles used by the Ashy Tailorbird (Orthotomus ruficeps) in Southeast Asia (Fig. 14.08A) and the Tawny‐faced Gnatwren (Microbates cinereiventris) in the neotropics (Fig. 14.08B)—the two species look similar but are only distantly related.

Fig. 14.08 Tropical microhabitat specialists. (A) The Ashy Tailorbird (Orthotomus ruficeps) of Southeast Asia and (B) the Tawny‐faced Gnatwren (Microbates cinereiventris) of the neotropics both occupy dense vine tangles, a microhabitat found commonly in tropical forests.

(Photographs by: A, Jason Tan; B, Nicholas Athanas.)

More generally, the food resources available in the tropics often allow birds to evolve highly specialized ecologies. For example, many tropical forest plants have fruits that are dispersed and flowers that are pollinated by birds, and in many tropical habitats, fruit and nectar are available throughout the year to specialized avian frugivores and nectarivores. Similarly, the year‐round activity of army ants provides a foraging opportunity for another specialized set of birds (Chapter 8).

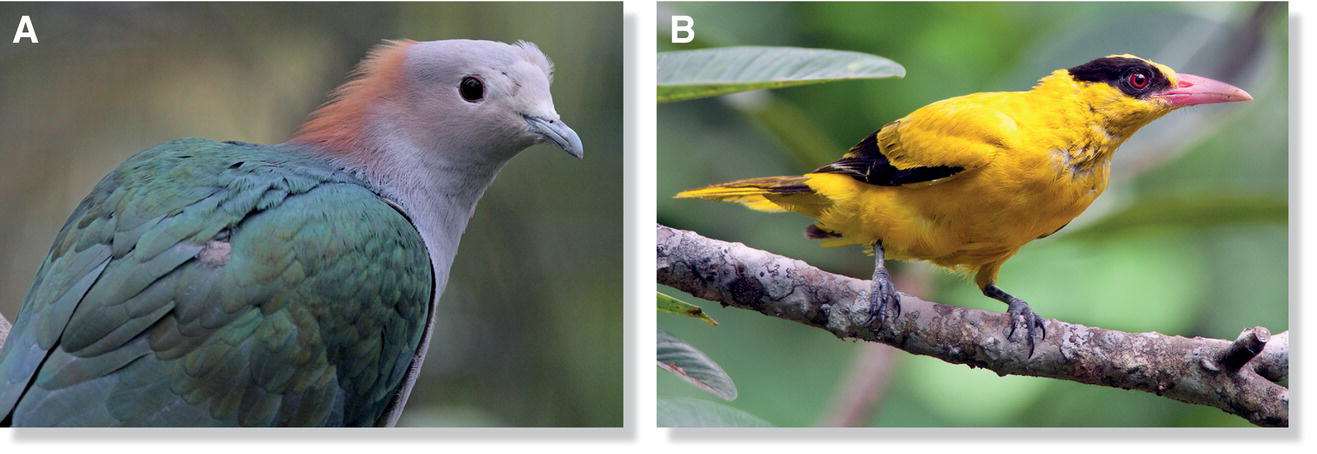

14.3.2 Habitat change and avian communities

Biological communities change in structure and composition in predictable ways as they develop on newly available land or reform after a major disturbance. For example, at most latitudes, a forested area cleared for agriculture and later abandoned progresses from an old field dominated by grasses and forbs, to a shrub or sapling stage, and finally to a forest. Even at the forest stage, fast‐growing but less competitive tree species eventually give way to old‐growth species. Many other kinds of disturbance, such as periodic fires, are natural components of ecosystems; some bird species thrive in certain stages of a habitat’s successional cycle (Fig. 14.09).

Fig. 14.09 Post‐disturbance colonizers. (A) Green Imperial‐Pigeons (Ducula aenea) and (B) Black‐naped Orioles (Oriolus chinensis) often colonize regenerating successional habitat on Asian islands where natural disasters—such as volcanic eruptions, floods, and fires—have wiped out most or all existing flora and fauna.

(Photographs by: A, Dick Daniels, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Green_Imperial_Pigeon_RWD5n.jpg. CC BY‐SA 3.0; B, Mohamad Zahidi.)

Where human‐caused or natural disturbances are common, bird species that rely on mature habitats will be extirpated. Similarly, bird species that thrive in early successional habitats will not occupy the same area once it passes a desired successional stage. For example, the endangered Kirtland’s Warbler (Setophaga kirtlandii) of North America can breed only in jack‐pine stands that are 5–20 years old (Fig. 14.10). This warbler underwent a disastrous decline during a long period of active fire prevention during which its required young pine habitat grew too old to provide good breeding conditions for the warbler. Other bird species that are restricted to flammable habitats likewise rely on fire to regenerate essential resources. For example, surveys across hundreds of points in western conifer forests have shown that in this part of its range, the Black‐backed Woodpecker (Picoides arcticus) is an extreme fire specialist that very rarely is found far from recently burned stands of timber (Hutto 2008).

Fig. 14.10 An early successional habitat specialist. Kirtland's Warblers (Setophaga kirtlandii) require newly regenerating jack‐pine forests to breed. Natural forest fires historically kept trees in an early successional stage. However, the Kirtland’s Warbler is now endangered, in large part due to the recent suppression of fires in north‐central North America.

(Photograph by James D. Ownby.)

14.3.3 Landscape effects on bird diversity

Similar habitats can host different numbers of bird species, depending on factors such as the size and shape of the habitat patch and the nature of the surrounding area. To a large degree, this landscape effect stems from the general species–area curves discussed earlier in this chapter: larger patches support more birds and/or a greater diversity of habitat, and for both reasons they are more likely to contain rare species. Individual bird species also show varying degrees of area sensitivity, as they are not able to persist in habitat patches below a certain size. The effects of area sensitivity are apparent in most areas of the world where small habitat remnants hold only a subset of the birds that would be expected to occur there if those patches were instead part of a more continuous block of intact habitat.

Some of the best evidence for how birds respond to habitat reductions comes from experimental studies of fragmentation, such as long‐term research in a series of artificial forest fragments near Manaus, Brazil. Starting in 1980, a team of scientists subdivided the previously continuous forest at this site into a series of smaller forest patches ranging in size from 1 to 100 hectares. They then closely monitored the bird communities within each patch. As expected, the smaller patches suffered much greater levels of bird extinction than the larger patches, starting almost immediately after their fragmentation and continuing on through the next several decades (Stouffer et al. 2009).

Fragmentation effects on birds vary in intensity in different regions. Although they generally are severe in tropical forests around the world, they tend to be less of an issue in Eurasian than in North American forests, and less severe in boreal coniferous forest than in deciduous forests. Fragmentation effects are not restricted to forest, and have been documented for a variety of habitats from desert to salt marsh. For example, in a region of southern France where the landscape is a mix of pine forests and savanna patches, grassland specialists such as the Sky Lark (Alauda arvensis) and Northern Wheatear (Oenanthe oenanthe) show strong declines when their habitat is fragmented, whereas habitat generalist bird species are less affected (Caplat and Fonderflick 2009).

Fragmentation is not always bad for birds, and many habitats are naturally fragmented. Where the avifauna has evolved in a natural habitat mosaic, the effect of human‐caused fragmentation may be less drastic. For example, the bird assemblages in cloudforests of Central America and the Andes—which often occur in isolated patches on mountain slopes—are thought to be more resilient to fragmentation than the assemblages of nearby lowland tropical forests.

14.4 The niche: a fundamental unit in community ecology

The ecological niche concept was first introduced in the early 1900s by Joseph Grinnell, an influential California ornithologist (Grinnell 1917). It holds that the ecological niche is the ultimate distributional or spatial unit occupied by a species, to which the species is held by limitations such as climate, kind (and amount) of food, nesting sites, and cover. The niche concept became widely used by ecologists, leading to the now famous (but far less poetic) definition that a niche is an “n‐dimensional hypervolume of viable interactions between organisms and their environments” (Hutchinson 1959).

The ecological niche thus comprises the place where birds live and the resources they use. Biological considerations take the niche concept beyond this simple level of description and imbue it with additional complexity. A bird species might be capable of making a living in a broader range of habitats or of consuming a broader diet were it not for the presence of predators, competitors, and parasites—both avian and non‐avian. The complete potential niche, unaffected by these interactions with other species, is referred to as the fundamental niche. A bird species’ real‐world niche that is circumscribed by all its interactions with other species is known as the realized niche.

14.4.1 Niche overlap and niche breadth

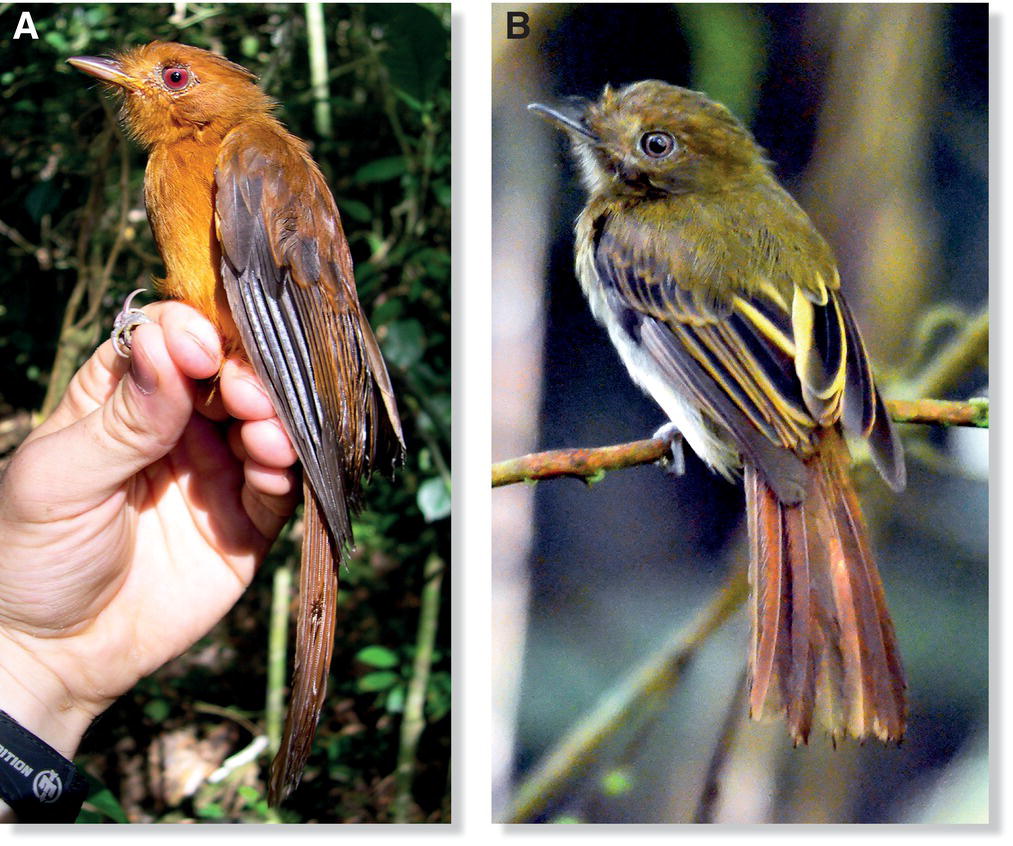

Niche breadth is a measure of a bird’s level of ecological specialization. A species with a narrow niche breadth is a specialist, and one with a broad niche breadth is a generalist. Niche breadth can be measured for a particular resource (for example, diet), and a bird species can be a specialist in one area and a generalist in others. Most commonly, this spectrum is used to describe the variety of foods eaten by a certain bird species (Chapter 8), or the range of habitats in which it occurs. Closely related bird species can differ notably in their level of specialization; for example, the rare Rufous Twistwing (Cnipodectes superrufus) of Peru, Bolivia, and Brazil is an extreme habitat specialist that is only found in dense Guadua bamboo patches (Fig. 14.11A). In contrast, a close relative, the Brownish Twistwing (Cnipodectes subbrunneus), is a habitat generalist common throughout much of Central and South America (Tobias et al. 2008) (Fig. 14.11B).

Fig. 14.11 Close relatives can differ in niche breadth. (A) The rare Rufous Twistwing (Cnipodectes superrufus) is a habitat specialist restricted to mature bamboo patches, while (B) the closely related Brownish Twistwing (Cnipodectes subbrunneus) is a common habitat generalist found across most of Amazonia.

(Photographs by: A, Daniel J. Lebbin; B, Yvonne Stevens.)

The specialist/generalist concept does not necessarily account for how readily birds change resource use in response to changed conditions. So the specialist/generalist contrast is related to—but is not the same as—a contrast between plastic and stereotyped behaviors. A behaviorally plastic bird species will readily change its foraging behavior, nest site preference, or some other aspect of its ecology in the face of habitat or climate change, whereas a behaviorally stereotyped species remains relatively constant in its preferences. The Cocos Finch (Pinaroloxias inornata) discussed in Chapter 8 is a classic example of a species with highly plastic foraging behavior, in which individual finches adopt a range of foraging behaviors even within the same habitat.

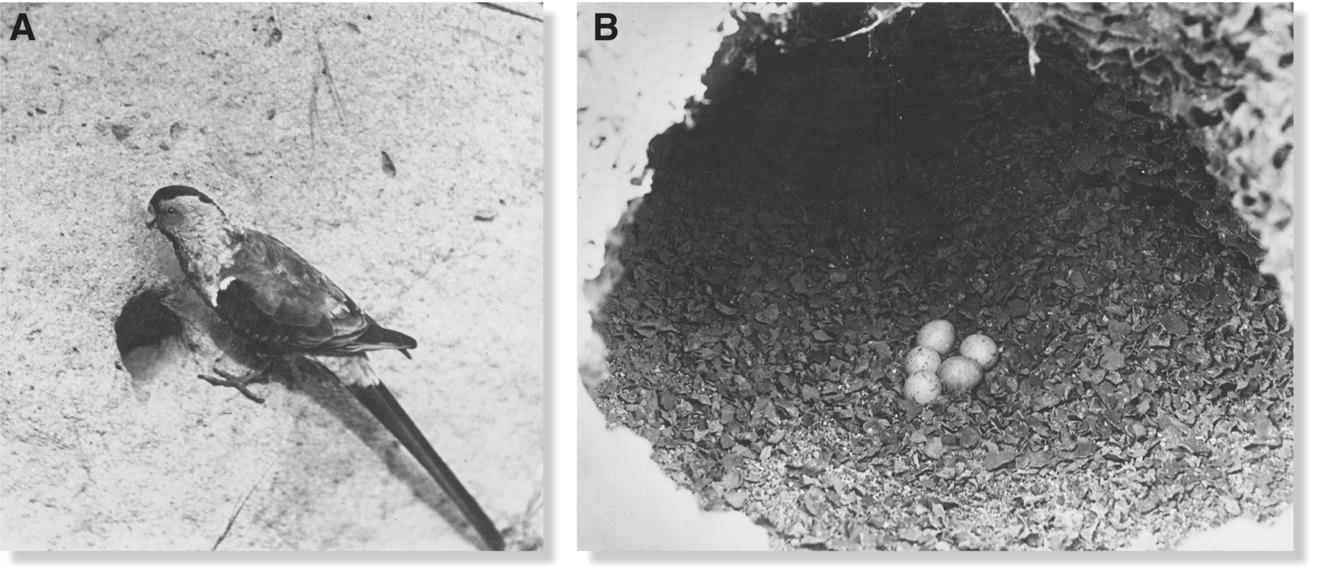

No single niche breadth strategy is intrinsically better than another. Under appropriate conditions, specialist birds may outcompete other species by being very good at what they do. If conditions change, however, a decline in their preferred food item or essential habitat feature may place specialist species at high risk of local or complete extinction. There are many unfortunate examples of specialized birds that have gone extinct following human‐caused changes to their environment. For example, the remarkable Huia (Heteralocha acutirostris) specialized on digging grubs from decaying trees in old‐growth forest; the clearing of most of the New Zealand forest contributed to its extinction in the 1900s (Chapter 8). Last seen in 1927, the Paradise Parakeet (Psephotus pulcherrimus) (Fig. 14.12A) of south‐central Queensland and northern New South Wales (Australia) is considered extinct due to its obligate dependence on a specific grassland community and specialized nesting substrate. Human habitat alteration through altered burn regimes, cattle grazing, and agriculture destroyed the wild grasses that provided the species’ principal food (grass seed) and altered the landscape such that old termite mounds (necessary for breeding) were no longer available (Fig.14.12B). Hunting for the colorful plumes of this species exacerbated the population decline.

Fig. 14.12 Presumed extinction of an Australian grassland specialist. (A) This is the last known photograph of the extinct Paradise Parakeet (Psephotus pulcherrimus), taken in the wild at Burnett River, Queensland in 1922. The individual is perched at (B) its nest entrance located in a hollowed‐out termite mound, a very specialized substrate. Humans are largely to blame for destroying its breeding habitat.

(Photographs by Cyril Henry H. Jerrard, courtesy of the National Library of Australia: A, nla.pic‐vn3124459; B, nla.pic‐vn3125063.)

Generalists are “jacks of all trades and masters of none.” However, the ability to move readily between habitats and consume a wide variety of foods allows generalists to persist under conditions where specialists perish. Habitats with a greater number of relatively constant resources will tend to support more specialists than habitats with fewer resources that fluctuate markedly in their availability. Some of the most impressive avian generalists are urban invasive species such as the Rock Pigeon (Columba livia), House Sparrow (Passer domesticus), and European Starling (Sturnus vulgaris), which have all spread around the world and now occur in thousands of cities with highly variable climates and food resources.

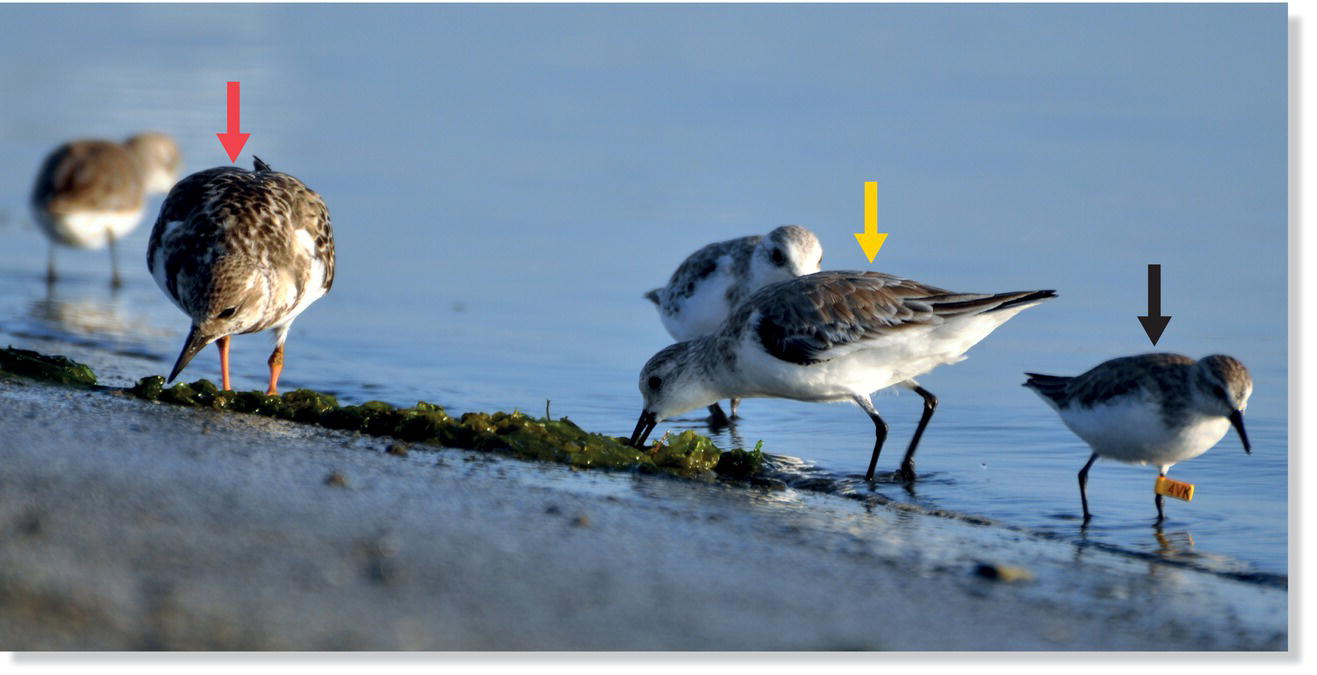

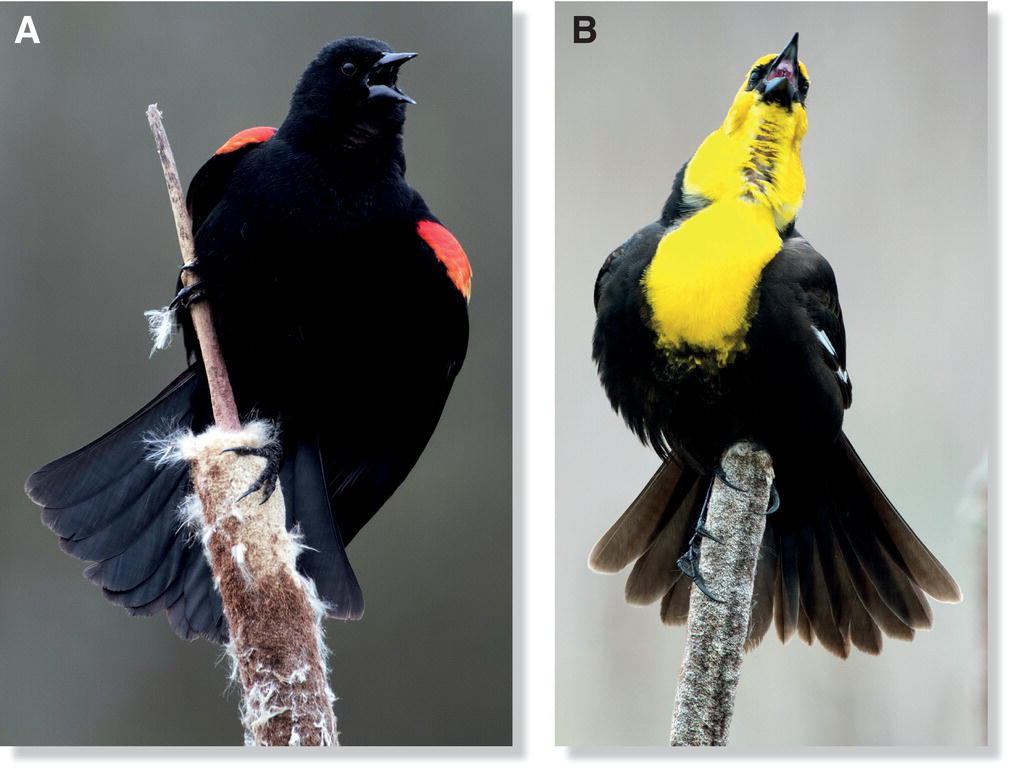

The degree to which two species share resources (as compared with their total potential resource use) is known as their niche overlap. Species that have high niche overlap are likely to compete for similar resources (Box 14.03). This pattern of partially overlapping niches occurs, for example, on mudflats where several different shorebird species forage together (Fig. 14.13). In these instances, the dominant species often occupies a niche that is wholly contained within the niche of the subordinate species. For example, in western North America, the nesting habitat of the Yellow‐headed Blackbird (Xanthocephalus xanthocephalus) is wholly contained within the preferred nesting habitat of the Red‐winged Blackbird (Agelaius phoeniceus) (Fig. 14.14). In places where both species occur, the Yellow‐headed Blackbird dominates the Red‐winged Blackbird, excluding it from the best nesting sites: cattail marshes with standing water. The male Yellow‐headed Blackbirds, perhaps because of their larger size (80 versus 64 grams), are able to dominate and exclude both sexes of the other species (Orians and Willson 1964).

Fig. 14.13 Niche overlap and resource competition. Ruddy Turnstones (Arenaria interpres; red arrow), Sanderlings (Calidris alba; yellow arrow), and Semipalmated Sandpipers (Calidris pusilla; black arrow) actively hunt for insects, crustaceans, and worms on the same crowded Peruvian shoreline. Each species has a slightly different foraging morphology and behavior, reducing their competition for resources.

(Photograph by Eveling Tavera Fernández.)

Fig. 14.14 Competitive dominance in overlapping niches. Where their ranges overlap, (A) Red‐winged Blackbirds (Agelaius phoeniceus) are outcompeted for nesting habitat by (B) Yellow‐headed Blackbirds (Xanthocephalus xanthocephalus), which are larger and more aggressive.

(Photographs by Richard Cameron.)

In competition for resource exploitation, the impact that one species has on another is strongly related to their niche overlap. However, developing a standardized way of estimating niche overlap between species has vexed avian ecologists for decades. Birds seldom compete over resources along a single, easily described range (such as prey size or foraging height). Instead, they can share or differentiate the resources they use by a huge variety of variables, including habitat, vegetation level, microhabitat searched, plant type preferred, prey type preferred, prey size, and many more. These variables often are referred to as niche axes. Examined from this perspective, niche overlap is a measure of similarity along one or many of the possible axes. Researchers most commonly calculate niche overlaps using statistical approaches that incorporate many variables at once, as in the comparison of the foraging niches of three penguin species on Ardley Island in Antarctica (Wilson 2010) (Fig. 14.15). Careful tracking of foraging penguins showed that although the three species feed on similar prey, they generally do so at different times and places, and hence their niche overlap in time and space is surprisingly low: they forage together in ways that might lead to direct competition less than 10% of the time.

Fig. 14.15 Foraging niche overlap. Although Adelie (Pygoscelis adeliae), Chinstrap (Pygoscelis antarcticus), and Gentoo (Pygoscelis papua) Penguins hunt similar prey, they partition foraging effort in space and time to decrease resource competition. (A) These maps illustrate the relative time spent foraging (diving) per location for each species. All three breed on Ardley Island, located at point 5, 5. (B) This graph demonstrates that each species has a different diving strategy based on time of day.

(From Wilson 2010. Reproduced with permission from John Wiley and Sons.)

14.4.2 Competitive exclusion and limiting similarity

The competitive exclusion principle, which holds that no two species can occupy identical niches indefinitely without one going extinct, is an important extension of the niche concept. This principle has had many proponents since the beginning of the twentieth century, but California ornithologist Joseph Grinnell proclaimed it succinctly in 1917: “It is, of course, axiomatic that no two species regularly established in a single fauna have precisely the same niche requirements.”

The competitive exclusion principle did not initially lead to especially productive insights into avian ecology, for two reasons. First, for birds and other mobile organisms with complex life histories, the important components of the niche must be measured at the particular time of year when the population is most limited. Additionally, the degree to which populations experience limitation or regulation (Chapter 13) varies from year to year in response to fluctuations in climate, food supply, and predator populations. Accordingly, some ecologists believe that competition may be important only rarely, when conditions are particularly bleak. Second, observant ornithologists are almost always able to detect some ecological difference between two bird species, and the question then becomes how similar two species really must be to violate this principle. Nonetheless, in the decades following the introduction of the competitive exclusion principle, many field studies focused on the patterns of niche differentiation in coexisting bird species, and this work generated many interesting insights into just how crudely or finely birds divide up their habitats and resources.

The competitive exclusion principle focuses on competitive interactions between species in its definition of a species’ ecological niche. Another approach is to define the niche in terms of the critical aspects of the bird’s environment by examining which of the many possible environmental factors seem to define a species’ distribution and abundance across a number of different habitats. For example, Fran James and her colleagues carefully analyzed the distribution and density of Wood Thrushes (Hylocichla mustelina) on study plots distributed over a large portion of the species’ breeding range in eastern North America (James et al. 1984). The researchers were able to identify common features of the niches that supported the highest densities of Wood Thrushes, including a low density of understory shrubs, a tall tree canopy, and a well‐developed layer of leaf litter on the forest floor.

14.4.3 Ecological guilds

Groups of birds with similar niches are known to ecologists as guilds, a concept developed by Richard Root (1967) as part of his studies of the Blue‐gray Gnatcatcher (Polioptila caerulea) in a Californian oak woodland. Root wanted to compare that species’ foraging ecology with the foraging behavior of other local birds that might be its potential competitors. Previous studies of avian competitors had generally focused on birds within the same taxonomic family, but Root reasoned that more distantly related birds may compete over their use of the same resources. Borrowing the concept of the trade guild (organizations of craftsmen doing the same job), he defined an ecological guild as a group of species that share the same basic foraging strategies and resources. At Root’s California study sites, various species of wood warblers and vireos—distantly related groups of small, foliage‐gleaning birds—were grouped together with the gnatcatcher in a “foliage‐gleaning” guild of insectivores.

The guild idea has since been broadened to include other aspects of habitat use, such as nest sites. For example, the hole‐nesting guild in a well‐studied primeval forest in Poland comprised 31 bird species, of which nine species (mostly woodpeckers) excavated their own cavities and the remaining species adopted pre‐existing cavities (Wesołowski 2007). One benefit of defining guilds in this way is that studies of ecological interactions can be undertaken for a logically selected subset of species within an entire assemblage. For example, a complete guild approach to the study of canopy foliage‐gleaning birds in a North American spruce forest would not be arbitrarily restricted to a single genus of wood warblers (as in Box 14.04), but also would include local species of kinglets, vireos, and chickadees. Divvying up species into guilds also provides researchers with a quick assessment of overall diversity, abundance, and biomass of the birds consuming different food resources. Habitats can be characterized by their dominant guilds as well: forests are often dominated by foliage‐gleaning birds, whereas grasslands are likely to host many ground‐foraging granivores.

14.5 Interspecific competition

Interspecific competition occurs when individuals of two or more bird species simultaneously use a resource—such as food or nest sites—that are in short supply. Competition can occur when one species simply is better at obtaining the resource and thereby reduces the availability of the resource below the level that can sustain the less proficient species. Ecologists refer to this process as exploitation competition. In contrast, interference competition occurs when one species interferes with the ability of other species to gain access to a critical resource, usually through aggression and dominance.

14.5.1 Exploitation competition

Through efficient resource use, one bird species may reduce the abundance of a resource to a level that is too low to support a less efficient species. However, if the species have different specializations, each may be able to concentrate on and competitively exclude potential competitors from a particular set of resources.

Flower nectar is one type of food that is particularly susceptible to exploitation competition when the first bird to visit a flower takes most of the nectar and leaves little for later visitors (Box 14.05). Nectar is relatively easy to measure in real flowers and to provide experimentally using artificial feeders. Researchers have taken advantage of these attributes to explore how nectivorous birds such as hummingbirds and sunbirds respond to exploitation competition. For example, Long‐tailed Hermits (Phaethornis superciliosus) in Costa Rica change their foraging strategy depending on the level of exploitation competition: when competitors are few, individual hermits visit particular flowers at long intervals, thereby allowing the flowers to replenish their nectar. In contrast, when competing hummingbirds are more of a threat, the hermits visit the flowers much more often to increase their access to new nectar (Gill 1988).

Exploitation competition may involve other kinds of animals with similar resource requirements. For example, researchers working in Sicily (Italy) found that breeding Eurasian Blue Tits (Cyanistes caeruleus) compete with a small rodent, the common dormouse, for ownership of artificial nest boxes. Particularly in places where boxes were rare, tit breeding success was low in years when dormice were abundant, and vice versa: the dormice did badly in years when tits were abundant (Sarà et al. 2005), because each nest box could be used by only one breeding animal at a time. In the Negev desert of Israel, several species of seed‐eating gerbils (small rodents) compete with Crested Larks (Galerida cristata) for seeds. Although the gerbils are more efficient than the larks at finding and eating seeds, the larks can coexist with these small mammals because their ability to fly allows them to cover a larger area of sandy habitat to find ephemeral patches of seeds uncovered by the wind (Garb et al. 2000).

14.5.2 Interference competition

When more than one species occurs in an aggregation feeding on the same type of food, the dominant species may gain access to the best food or feeding site by displacing subordinate species. This type of interaction often can be witnessed at a bird feeder, where dominant (usually larger) species can supplant subordinate species from a pile of seeds or a suet ball. The interaction may be subtle, with the subordinate leaving just before the dominant arrives, but the lack of overt fighting probably is an adaptive response by the subordinate to avoid unnecessary injury.

Contrary to what you might expect, dominants do not always try to get first access to a feeder. After a predator (or in the case of a human disturbance, a potential predator) disturbs a feeder, subordinates may return first. In this case, the dominant is ultimately assured of access to the best feeding site but uses the subordinate to “test the waters” for further danger. The subordinate takes the risk to gain access it otherwise would not have when the dominant species is at the feeder.

Interference competition at bird feeders has been particularly well studied in European locations where several species of tits occur. These tit species usually differ conspicuously in their ranks in an interspecific dominance hierarchy (Chapter 9), with some species able to displace others from preferred feeding sites. In one such study site in the mountains of Spain, researchers provided the five local tit species with peanut‐filled feeders hung at either safe locations (near dense vegetation with potential hiding places for tits) or dangerous locations (exposed sites with no nearby refuge from predators) in the forest (Carrascal and Alonso 2006). The most dominant species, the Great Tit (Parus major), used only the safe feeders; the most subordinate species, the Long‐tailed Tit (Aegithalos caudatus), most frequently used the unsafe feeders. Interference competition among these species explains this pattern, with the more dominant tit species displacing the less dominant species from the best foraging sites.

In birds, some of the most extreme cases of behavioral dominance of one species over another involve interspecific territoriality. As in the much more common intraspecific territoriality (Chapters 9 and 13), interspecific territoriality involves the active defense of a specific place. The area defended by one species against another can vary from a large plot of land to a single food plant, and the number of excluded species can range from one to many.

The defense of patches of habitat usually occurs between related species. With no strong divergence in foraging behavior or nest ecology, the species may not be able to persist except though excluding the other species from the entire area. Such interactions tend to be found in habitats with relatively simple structure (grasslands, marshes, or shrubby second growth) or when the species involved are closely tied to a specific stratum within a more diverse habitat (such as ground or bark foragers) (Orians and Willson 1964). Usually there is some habitat segregation, and interspecific territories are defended at the border between habitats. For example, the various species of North American Empidonax flycatchers are extremely similar in morphology and behavior, often bedeviling birders trying to identify them. Although most Empidonax species have distinct ranges and habitat preferences, some species defend interspecific territories where their preferred habitats come together. For example, the Dusky Flycatcher (Empidonax oberholseri) occurs in mixed coniferous woodland in the mountains of California, and the Gray Flycatcher (Empidonax wrightii) prefers scrubbier habitats with only scattered trees characteristic of the Great Basin of western North America. At habitat edges, however, the two exceedingly similar species exclude each other from their territories (Johnson 1966).

Interspecific territoriality may play an important role in enforcing sharp distributional boundaries. Among the more than 300 species of birds that occupy vegetation along the Manu River in the Peruvian Amazon, from shoreline pioneer scrub communities to primary forest (Box 14.06), Scott Robinson and John Terborgh (1995) found 20 pairs in which related species were divided strikingly between early and late successional habitats. Using song playbacks, they showed that often the larger species approached the playback aggressively, but the smaller species shied away. The pairs of species showing these dominance‐related behaviors had the lowest distributional overlap, suggesting that interspecific territoriality allowed the dominant larger species to control the more productive habitat.

As discussed earlier in this chapter, interspecific resource defense is particularly prevalent among flower‐feeding birds: defending the energy‐rich and renewable nectar resource against all potential competitors often may be worth the energy cost it entails for the territory‐holding bird. Fruiting plants also may be defended against birds of other species, although this behavior is less common. In the highlands of Papua New Guinea, Thane Pratt (1984) monitored the interactions of all birds visiting several species of fruiting trees and found that birds in four different families (a bird‐of‐paradise, a cuckoo, a pigeon, and a wattlebird) each attempted to drive off all competitors from its respective tree. In North America, the Northern Mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos) similarly may attempt to dominate dogwood and other fruiting trees in the fall and winter (Moore 1978). Although most interactions are with neighboring mockingbirds, the birds aggressively chase away other birds too. Mockingbirds are largely successful in excluding individual birds, but they generally fail when confronting large flocks of American Robins (Turdus migratorius) or Cedar Waxwings (Bombycilla cedrorum).

Interspecific site defense by birds can have large ecological consequences that go far beyond the birds themselves. For example, some Australian woodlots suffer from a syndrome known as “Bell Miner‐associated damage.” The highly aggressive Bell Miners (Manorina melanophrys) defend eucalyptus trees infested with a small, plant‐sucking insect known as a psyllid. The psyllids excrete a sugary liquid that hardens into “lerp,” a rock‐candy‐like layer. The Bell Miners feed on lerp and chase away a host of smaller insect‐eating birds, thus allowing the psyllids to achieve a great abundance, sometimes to the point that they kill the trees on which they feed (Loyn et al. 1983).

Some cases of extreme interspecific aggression defy the simple dichotomy between interspecific territoriality and resource defense. For example, in snow‐melt lakes in the foothills of the southern Andes in Argentina, Flying Steamer‐Ducks (Tachyeres patachonicus) attack and occasionally kill a wide variety of ducks and other aquatic birds (Nuechterlein and Storer 1985). These lakes are relatively unproductive, so this interspecific aggression may reserve precious food for the aggressive steamer‐ducks. An alternative possibility is that the aggressive behavior is a way for a feisty male duck to show off to females.

14.6 Evidence for interspecific competition

The importance of interspecific competition in shaping species assemblages remains a hotly debated issue in ecology. Simply finding overlap between two species in the type of food they eat or the habitat they use does not automatically mean that the species are competing with one another. To detect competition, researchers must show that the resources are limited and that the activities of one species reduce the fitness of individuals of another species. Although documenting these outcomes might seem straightforward, it can be challenging to do in field studies. For example, resource competition might be strong when two species first occur together but then declines as the species evolve differences in foraging behavior or other traits. Ecologists sometimes refer to these evolved differences in resource use as “the ghost of competition past,” a phrase that captures the idea that some of the ecological and behavioral differences we see today among species might be the result of former competitive interactions that no longer are occurring.

Even present‐day competition can be surprisingly challenging to document. Interference competition would seem the easiest to demonstrate, because aggression, dominance, and territoriality between species often can be readily observed. Even in these cases, however, the long‐term effects on individuals and populations need to be measured carefully, because not all aggression is really competition in the ecological or evolutionary sense of the term.

14.6.1 Density compensation and ecological release

If interspecific competition is an important ecological force, then anything that reduces the abundance or diversity of a competing species should increase resources for the remaining species. Density inflation occurs when one species increases in number when its competitors are absent. This phenomenon often is particularly striking on islands that are dominated by a few—but very common—bird species. For example, the island of Bermuda, located in the Atlantic Ocean 960 kilometers from the coast of eastern USA, has been colonized by several North American bird species. Three of those species—the Gray Catbird (Dumetella carolinensis), Northern Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis), and White‐eyed Vireo (Vireo griseus)—comprise more than 80% of the individual birds found on Bermuda. The densities of each of these species are substantially higher than in similar habitats on the mainland. For example, cardinal densities on the island range from 62–67 birds per 40‐hectare plot, whereas similar areas on the continent have only 3–35 cardinals (Crowell 1962).

Although reduced competition for food resources is a common explanation for density inflation, other factors can cause or contribute to this phenomenon. Nest predation often is lower on islands, so birds living there may produce more young (George 1987). In addition, islands provide a natural barrier to dispersal, so that surplus birds may not be able to move to other sites as their population on an island increases beyond normal levels. This phenomenon, known as the “fence effect,” was first discovered in experiments with meadow voles (Microtus species), where the simple act of fencing off an area contributed to a tremendous increase in vole populations. It is likely that the same effect applies to birds, especially those with populations trapped on small, remote islands.

Under certain circumstances, the high populations of a few species of island birds can increase total bird density to the levels found in equivalent mainland habitats, a phenomenon known as density compensation. The degree to which a low‐diversity island fauna reaches full density compensation depends upon how similar the island’s habitats are to the original mainland source habitat for the colonizing species and on the diversity of island species: the more species there are, the greater is the overall degree of compensation (MacArthur et al. 1972). In some situations, overcompensation in bird numbers can occur when larger species are underrepresented on the island and the smaller species therefore have proportionately more resources. Density compensation can be striking on islands where the few birds present have extraordinarily high densities. For example, the Bananaquit (Coereba flaveola) is an uncommon resident of tropical habitats throughout much of Central and South America. In contrast, it often is the most abundant bird on islands in the West Indies, especially on small islands that have few other songbird species (Cox and Ricklefs 1977).

In the absence of competing species, birds may widen their habitat use and increase their population size, a pattern termed ecological release. For example, the Barred Antshrike (Thamnophilus doliatus)—a 30‐gram bird with a long, hooked bill (Fig. 14.16) and a penchant for eating katydids and other large insects—is restricted to second‐growth scrub on Trinidad, where it is part of a diverse insectivore guild. However, this species occupies a much broader array of habitats on the nearby island of Tobago, which lacks many of the other Trinidadian insectivores (Keeler‐Wolf 1986). Ecological release can involve a broadening of foraging niches as well as an expansion in occupied habitats. For example, a team of researchers compared the foraging behavior of a variety of white‐eyes (Zosterops species) in high‐diversity faunas on Australia and New Zealand and on low‐diversity islands nearby (Scott et al. 2003). The island white‐eye populations consistently showed a much greater range of feeding behaviors, indicating that in the absence of competitors on those islands they used a broader range of food resources.

Fig. 14.16 Ecological release. On the island of Trinidad, the Barred Antshrike (Thamnophilus doliatus) must forage in less‐preferred habitat (second‐growth scrub) due to fierce competition for large insect prey. However, many of these competitors do not occur on the nearby island of Tobago, where the Barred Antshrike is “released” from competition and forages in a wider array of habitats.

(Photograph by William H. Atwood, Jr.)

14.6.2 Character displacement

As we have seen, if two species are similar in their requirements for a limiting resource, theory suggests that one of two things should occur: either one species will go extinct (at least locally), or one species will diverge in its requirements and in its behavioral and morphological features to adapt to the new resources. This latter process is termed character displacement and it leads to the prediction that two similar species should show the greatest morphological divergence where their ranges overlap, and should be more similar to one another where they occur alone (Brown and Wilson 1956).

Clear‐cut examples of character displacement in birds are surprisingly rare, perhaps because of the great challenges of documenting a subtle set of changes that occurred in the past. Observing the evolution of character displacement between two ecologically similar bird species is even more unusual. For decades, scientists hypothesized that the number of species of Darwin’s finches that could co‐occur on a single island in the Galápagos was governed by limiting similarity, so that two species with similar bills could not co‐occur. Peter Grant and Rosemary Grant (2006) had the exceptional opportunity to document the process of character displacement over a 22‐year period when the Large Ground‐Finch (Geospiza magnirostris) invaded a small island already occupied by the Medium Ground‐Finch (Geospiza fortis) (Chapter 3). The bill size of the Medium Ground‐Finch species declined after the arrival of the larger species, especially during droughts when the birds depleted most of the available food and the larger finches were able to outcompete the smaller birds in seeking large seeds. Selective pressure favored Medium Ground‐Finches with smaller bills, which could survive by eating smaller seeds. This study illustrates how competition and natural selection can shape traits such as bill size over even short periods of time.

14.6.3 Community structure, competition, and assembly rules

Avian community ecologists have long been interested in how competition and other interspecific interactions influence the composition of bird assemblages. In a classic paper, ecologist G. Evelyn Hutchinson argued that limiting similarity is important in structuring animal assemblages, and that many show corresponding patterns of morphological diversity (Hutchinson 1959). He focused on the diets of species that could be positioned along a size gradient of prey items, in which each species eats prey in only part of the overall size range. In these situations, one often finds a series of increasingly large animals that differ from one another in size ratios of around 1.1 to 1.3. In birds, this pattern has been applied to bill‐length ratios in flycatchers feeding on different‐sized insects and in kingfishers feeding on different‐sized fish (Fig. 14.17). This regular spacing of birds along a size gradient is indirect evidence that the species in these assemblages are constrained by limiting similarity.

Fig. 14.17 Kingfisher bill‐length ratios demonstrate limiting similarity. As overall body size decreases, these morphologically similar kingfisher species show a remarkable stepwise difference in bill lengths. Each bill proportionally corresponds to the size of the fish its owner can catch, handle, and consume.

(© Cornell Lab of Ornithology.)

Of course, most birds and their prey do not differ along one simple size gradient, so an examination of size ratios does not allow an ecologist to determine whether an entire bird assembly is structured by competition. In a series of bird studies on the Bismarck Archipelago in the southwest Pacific, Jared Diamond proposed that the species assemblage on any specific island (which is always a subset of the bird species found across an island group) is determined largely by competitive interactions (Diamond 1975; Sanderson et al. 2009). Diamond formulated these interactions into a set of assembly rules. These rules have been hotly debated among ecologists because demonstrating patterns that conform to them is statistically very tricky. The most important (and contentious) of these rules is what Diamond aptly termed a “checkerboard” distribution pattern, in which each island hosts only one of several ecologically similar birds (Fig. 14.18). Diamond suggested that these checkerboards arise from the presence of limiting similarity: certain combinations of species will not occur because of their inability to coexist.

Fig. 14.18 Checkerboard pattern of species distributions. The Black‐billed Cuckoo‐Dove (Macropygia nigrirostris) and Mackinlay’s Cuckoo‐Dove (Macropygia mackinlayi) require similar resources and segregate spatially. Though both species occur in the Bismarck Archipelago, each island has only a single species: M. mackinlayi (gold) occupies small and/or remote islands, while M. nigrirostris (blue) occupies larger islands (New Britain and New Ireland). In the Solomon Islands, however, where M. nigrirostris is absent, M. mackinlayi occurs on all islands, regardless of size.

(From Mayr and Diamond 2001. Reproduced with permission from Oxford University Press, USA.)

Whenever an ecological pattern such as checkerboard distribution is proposed, it is important to determine through statistical analysis if the pattern differs from what one might see if species distributed randomly from the source pool without selective pressure. In any real set of species assemblages, there always will be combinations of species that do not occur simply because of chance. The random model of species composition is referred to as the “null hypothesis” for community structure. Searching for patterns that cannot be generated from a null hypothesis has been a major activity of community ecologists for the past few decades. For example, much of the debate over checkerboard patterns has centered on the best ways to test whether such patterns differ from what might be expected by chance if competition plays no role in influencing which species can co‐occur on the same island.

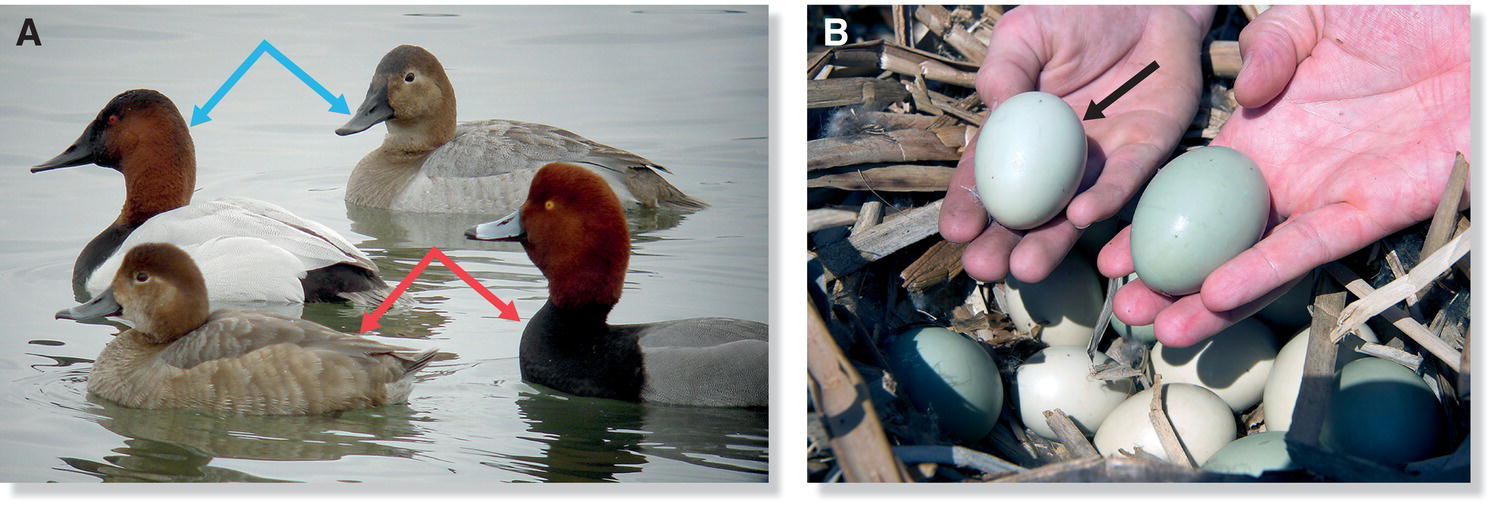

Studies of other avian assemblages also have found that species occur in non‐random patterns. In North America, the massive glaciers that receded at the end of the Pleistocene (about 18,000 years ago) left behind landscapes dotted with small ponds and lakes. These areas, including the prairie potholes and the Canadian Shield regions of subarctic boreal forest, often are referred to as the “duck factories of North America” because of the abundance of waterfowl that breed in these wetlands. Most ducks are readily divided into two foraging guilds (Chapter 8): dabbling ducks that feed in shallow water for insects and submerged vegetation, and diving ducks that plunge into deeper water for invertebrates and fish. In a single region of subarctic ponds, in theory, as many as a half‐dozen dabbling duck species could co‐occur during the breeding season, but in fact only a few dabbling species generally breed along any single body of water. Ecologists have used the combinations of ducks breeding on a series of ponds to test the hypothesis that competition determines which combinations of species occur (Toft et al. 1982; Gurd 2008). Combinations comprising duck species that have a similar breeding schedule or habitat preference were less likely to occur than would be expected by chance, suggesting that competition has a role in determining duck community structure.

14.6.4 Phylogenies and the history of communities

Recent advances in phylogeny analysis (Chapter 2) provide tools for comparing how assemblages form and allow a different kind of test of the role of competition and other forces. In these studies, real assemblages are often compared with computer‐generated random assemblages to see if the real assemblages contain birds that are more closely or distantly related than one would find by chance. For example, armed with a phylogeny of hummingbirds, Catherine Graham and her colleagues (2009) calculated the average relatedness of species at different sites across Ecuador. They found that in the lowland tropics, species were less related than would be expected by chance, but the opposite was true for highland assemblages. They inferred that competitive exclusion of close relatives is important in the lowlands, whereas “ecological filtering” selects for particular clades of hummingbirds adapted to the more climatically challenged environment in the highlands (Box 14.07). Continent‐wide comparisons of breeding assemblages of North American wood warblers similarly show that closely related species tend to occur together less often than expected by random chance (Lovette and Hochachka 2006).

14.6.5 Competition experiments in birds

As with the birds of the Bismarck Archipelago in Papua New Guinea and dabbling ducks in prairie potholes, the effects of competition on patterns of avian niche displacement, expansion, and contraction most often are inferred from natural patterns and correlations. However, a controlled experiment is the gold standard for establishing any form of causation in science. For example, a researcher might infer character displacement when she finds that the foraging ecology of two species varies more in the areas where they occur together. However, every site can have numerous uncontrolled (and sometimes unsuspected) ecological differences that influence patterns in unknown ways. Carefully designed and executed experiments eliminate confounding variables and provide a more definitive evaluation of the competition hypothesis.

Although it might sound ruthless, the most obvious experimental manipulation for testing the effects of competition is to remove a potential competitor and then track any subsequent niche shift, increase in survival, or change in reproductive output (fitness effects) in the remaining bird species. Such manipulations often are very difficult to accomplish in practice, so relatively few experimental removal studies have been conducted in avian assemblages. In the forests of Scandinavia, two species of tits, the Willow Tit (Poecile montanus) and the Coal Tit (Periparus ater), form winter flocks with the Goldcrest (Regulus regulus). The Coal Tit and Goldcrest restrict their search for insects to the outer branches of conifers, and the Willow Tit explores the larger, inner branches. On islands where the Willow Tit is absent, the Coal Tit shifts its foraging to include both the outer and inner portions of the trees. This observation suggested that either exploitative competition (perhaps Willow Tits are better at foraging in the inner branches and make it unprofitable for Coal Tits to shift) or interference competition (perhaps Willow Tits are dominant to Coal Tits) restricts the Coal Tits to the outer branches when both species are present. To test this idea, Rauno Alatalo and his co‐workers successfully captured and removed Willow Tits at the beginning of the winter from mainland sites and carefully measured the foraging behavior of the remaining Coal Tits (Alatalo et al. 1985). They found that, just as on islands lacking Willow Tits, the Coal Tits shifted to forage towards the trees’ centers in the absence of Willow Tits. This study was one of the first to demonstrate clearly the role of competition in shaping a songbird species’ foraging niche.

Although field experiments that add or remove species are logistically difficult, researchers sometimes can measure the effects of competition by taking advantage of so‐called “natural experiments” in which species change in abundance for other reasons. For example, ornithologists already working on the island of Hawaii monitored native bird populations before, during, and after a dramatic population increase in an introduced species, the Japanese White‐eye (Zosterops japonicus), which became ultra‐abundant at some study sites around the year 2000 (Freed and Cann 2009). As the white‐eye population increased, the native Hawaiian honeycreepers suffered, declining both in overall numbers and in the body condition of the remaining individuals, with juvenile honeycreepers doing particularly poorly. These native birds showed no such decline at nearby study sites where Japanese White‐eyes remained uncommon. White‐eyes are successful generalist feeders, so it seems likely that food resources became limiting for honeycreepers when they had to compete with large numbers of white‐eyes. White‐eyes suffered less from the reduced food because they moved more freely to and from disturbed habitats outside the forest and, as generalists, had greater diet flexibility.

Although community ecologists have focused primarily on competition over food, other limiting resources also can cause intense interspecific strife. Competition for the best nest sites can occur between species that build their own nests as well as among cavity‐nesting species. For example, Orange‐crowned Warblers (Oreothlypis celata) and Virginia’s Warblers (Oreothlypis virginiae) often breed at the same sites in the southwestern USA. The experimental removal of Virginia’s Warblers did not affect where Orange‐crowned Warblers nested, but it did result in lower losses to nest predation, presumably because the reduced overall density of warbler nests attracted fewer nest predators to the area (Martin and Martin 2001). In contrast, the removal of Orange‐crowned Warblers led Virginia’s Warblers to shift their nest sites to those previously used by Orange‐crowned Warblers, allowing them both to feed nestlings at a higher rate and to suffer less nest predation. Here too, competition was asymmetrical, with the Orange‐crowned Warblers dominating Virginia’s Warblers and maintaining access to better sites.

14.6.6 Competition between birds and other animals

Ecological guilds can include animals of various kinds. For example, the nectar‐feeding guild in a tropical forest in southern Mexico includes many hummingbirds; other nectivorous birds such as the Bananaquit (Coereba flaveola), Red‐legged Honeycreeper (Cyanerpes cyaneus), and migratory Chestnut‐sided Warbler (Setophaga pensylvanica); various species of nectar‐feeding bats; a medium‐sized nectar‐feeding mammal called a Kinkajou; and hundreds of species of bees, flies, and other nectar‐feeding insects. Although these various animals have preferences for certain types of flowers, they are all potential competitors for nectar resources.