Chapter 15

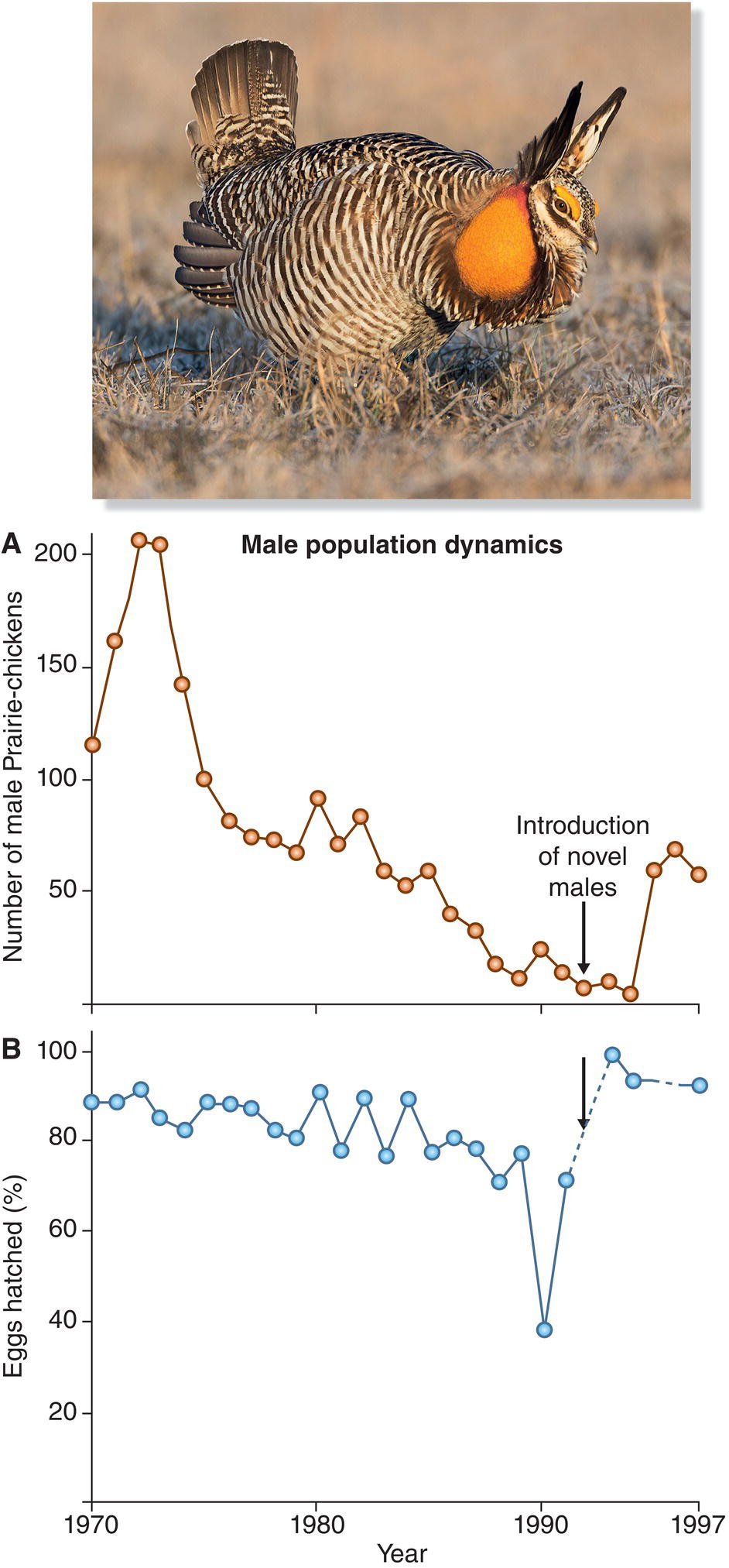

Bird Conservation

John W. Fitzpatrick and Amanda D. Rodewald

Cornell Lab of Ornithology

(Photograph by Gerrit Vyn.)

Until the mid‐1800s, travelers in the springtime woods of eastern North America would marvel as multitudes of large, long‐tailed doves swirled into dark clouds overhead during the spring migration. Millions of beating wings resonated like strong winds through pine boughs while the immense horde streamed northward. The passage of such a flock might continue all day, with straggler flocks following thereafter for weeks.

The Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) was then almost certainly the most abundant bird on earth (Fig. 15.01). Accounts of their numbers written between 1630 and 1880 read like science fiction (Schorger 1955). John James Audubon wrote of a flock passing for three successive days near Louisville, Kentucky (USA) in 1813, stating that “the light of the noonday sun was obscured as by an eclipse.” He estimated the mile‐wide flock to contain a minimum of 1.1 billion birds. Alexander Wilson, often called the father of North American ornithology, considered his own 1806 estimate of a single flock—2,230,272,000 birds—to be well below its actual number.

Fig. 15.01 Passenger Pigeons (Ectopistes migratorius). At the time of the European settlement of North America, this species was considered to be the most abundant bird on earth. Audubon reported a flock estimated to contain over 1 billion individuals. Flocks once migrated across eastern North America, settling to breed in huge colonies where they found bounties of tree‐nuts (such as acorns, chestnuts, and beechnuts).

(Illustration by N. John Schmitt.)

How many Passenger Pigeons existed across the entire range of the species? Nobody knows for sure, but the number may have been 5 billion or more. For perspective, only one wild bird species in the world today, the Red‐billed Quelea (Quelea quelea) of sub‐Saharan Africa, likely reaches 1 billion individuals. Yet by 1914 the Passenger Pigeon was extinct, just 100 years after Audubon and his contemporaries wondered at its incredible abundance. Accounts of Passenger Pigeons provide deeply moving glimpses of a world that was very different from today, yet existed only a few generations ago. This contrast reminds us of the astonishing changes caused by humans across the world’s landscapes and across bird populations.

No doubt exists about why Passenger Pigeons disappeared. As for so many other species, this gregarious dove was extinguished by the deadly one‐two‐three punch that already had become a signature of human expansion across the world: (1) uncontrolled exploitation (in this case, hunting for food); (2) advances in technology that aided exploitation as numbers decreased (firearms and railroads); and (3) large‐scale alteration of the landscape for agriculture and human settlement (clearing of mature, seed‐producing oak and beech forests).

Many contemporary accounts of Passenger Pigeon nesting colonies emphasized the frenzied slaughter of the birds by hunters more than the natural wonder of the birds themselves. Even at the last large colony documented—in 1878 near Petoskey, Michigan (USA)—300 tons of Passenger Pigeons killed by professional market hunters were shipped by railroad to restaurants in Chicago, New York, and Boston. Because the species nested in dense colonies and nestlings were easy and delicious prey, a colony’s entire reproductive output could be wiped out during a single season. Last‐ditch efforts to avert the Passenger Pigeon’s extinction in the 1890s through publicity and legal protection came too late: Martha, the world’s last individual Passenger Pigeon, died at the Cincinnati Zoo (USA) on September 1, 1914.

Preserved as a specimen at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, DC, Martha invites reflection on humans’ relationship with the earth. She died just as the global conservation movement was being born. This new movement would go on to establish the revolutionary laws, organizations, and actions that serve to protect birds and other emblems of wildness today.

15.1 History of bird conservation

The roots of bird conservation lie in the many past tragedies of overexploitation that are exemplified by the Passenger Pigeon. The earliest bird protection laws were efforts to curb overuse of hunted species. Laws establishing hunting seasons and regulations for particular groups of birds, such as upland game birds, were passed in the early 1700s in North America. Likewise, in both Britain and Newfoundland (now Canada), some of the first laws protecting birds were passed in 1775 to stem the exploitation of the Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis). In response to an already staggering level of market hunting in eastern North America, the state of New York passed legislation in 1791 to restrict hunting seasons for Heath Hen (Tympanuchus cupido cupido), and Massachusetts (USA) passed an Act to Protect Useful Birds in 1818. As early as the mid‐1800s Michigan passed several laws attempting to limit the hunting of Passenger Pigeons, although they were weakly enforced.

New Zealand enacted its first law to protect native birds with the Wild Birds Protection Act of 1864 (earlier misguided regulations had instead protected introduced bird species). Shortly thereafter, the UK passed the Sea Birds Preservation Act of 1869, which restricted shooting and egg collecting during the breeding season. This act was followed by a series of Wild Birds Protection Acts in the UK between 1880 and 1896 that prohibited harvesting outside of certain seasons and taking the eggs of wild birds. These initial legislative efforts proved insufficient to curtail the loss of certain species but did fuel a more organized and widespread conservation movement.

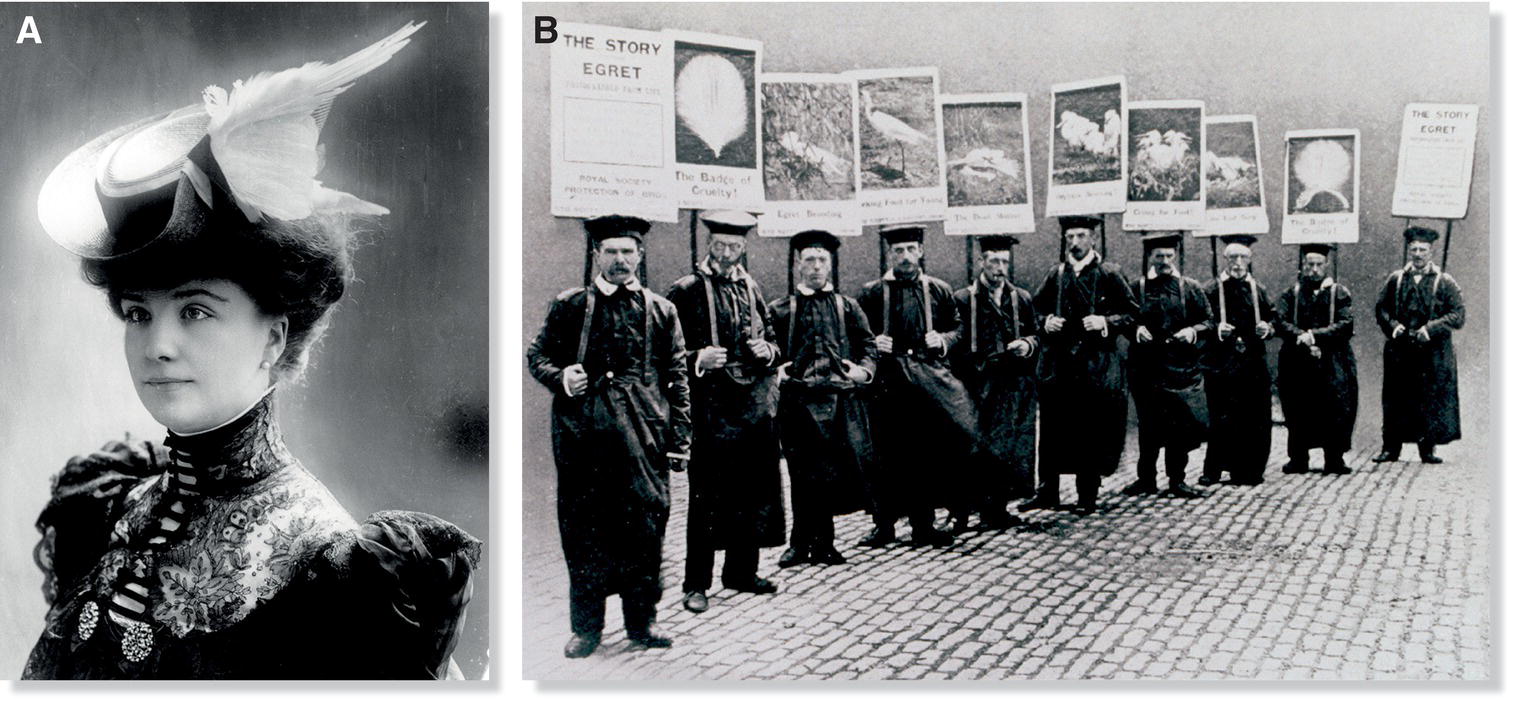

Commercial plume hunting in the late 1800s was a turning point for early bird conservation. At this time, feathers (and sometimes entire birds) were considered fashionable adornments on women's hats (Fig. 15.02). Gaudiest were the plumes of several herons, such as the Great Egret (Ardea alba) and Snowy Egret (Egretta thula), which bred in large rookeries. By the 1890s, the scale and biological effects of commercial plume hunting rivaled the wholesale slaughter of Passenger Pigeons two decades earlier. In North America, concern over plume hunting and the decline of birds led, in part, to the founding of the American Ornithologists’ Union (AOU) in 1883, along with its influential Bird Protection Committee. In 1886 a charter committee member, George Bird Grinnell, established the Audubon Society dedicated to the protection of birds. In 1889 in the UK, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) was similarly created in response to the feather trade; today the RSPB is one of the world’s largest conservation organizations.

Fig. 15.02 Feathers as fashion accessories. The widespread use of feathers—and sometimes entire birds—as fashion accessories (A) led to the near extinction of some populations of egrets and other charismatic birds, thereby sparking some of the earliest bird conservation movements such as these early supporters of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds in the United Kingdom (B).

(Photographs courtesy of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds.)

Despite laws regulating the commercial harvest of certain birds, widespread hunting and trading continued largely unchecked around the world until the early 1900s, when activists began focusing on trade rather than harvest. Catapulted by the social activism of local Audubon societies, the US government passed the landmark Lacey Act, which banned interstate shipments of birds killed in violation of any state or local law. Revisions to this act ultimately gave rise to the Migratory Bird Treaty Act in 1918, which implemented elements of the International Migratory Bird Convention Act signed in 1916 by Great Britain, Canada, and the USA. Later, other international treaties were incorporated into the act, including the Migratory Bird and Game Mammal Treaty with Mexico (1936), and the Convention on Nature Protection and Wildlife Preservation in the Western Hemisphere (1940). International treaties that protect birds continued to be ratified around the world throughout the twentieth century; among the most important were the African Convention on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (1968) and the Agreement on the Conservation of African‐Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (1995).

Expanding the targets of conservation beyond the regulation of hunting and trade, major efforts to conserve birds by protecting their habitats came in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Preserves were created in many countries around the globe; in the late 1800s, for example, several New Zealand islands were named as sanctuaries for native birds such as the Kakapo (Strigops habroptila) and Kiwi (Apteryx species).

This period also saw the birth of broader, organized systems of protected areas. Partly in response to the plume trade, Theodore Roosevelt designated the first federal refuge in 1903 at Pelican Island, Florida, thereby launching the National Wildlife Refuge System within the USA. Not long afterward, Mexico’s first wildlife refuge was established at Isla Guadalupe. The National Park concept remains a foundation of habitat conservation around the globe. In the USA, after establishment of the first National Park in Yellowstone (1872), a trove of other areas received similar protection through the newly created system of National Forests, National Parks, and National Monuments. Australia followed (1879), then Canada (1885), and New Zealand (1887). Today nearly 100 countries boast internationally recognized national parks. Among the most recent is Afghanistan, which created its first national park, Band‐e‐Amir, in 2009.

Habitat protection remains among the most important elements in bird conservation and involves every level of society. In addition to government‐led efforts, a variety of non‐governmental organizations promote protection and management of habitats for birds. An increasing number of places around the world are officially recognized for their international importance to birds. The Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance and the UNESCO World Heritage List are two examples of multinational conventions that have identified places of global importance for conservation. BirdLife International now recognizes more than 11,000 Important Bird Areas (IBAs) around the globe, although legal recognition and protection of these areas vary widely among countries.

Bird conservation in the twentieth century was shaped profoundly by the public’s increasing awareness of environmental problems and growing sense of collective responsibility for environmental protection. In an influential collection of essays titled A Sand County Almanac, Aldo Leopold (1949) established both a philosophical and a practical framework for treating the natural landscape as a long‐term resource to be used carefully and held in safekeeping for future generations. Leopold introduced the concept of the “land ethic,” whereby natural resources are seen to warrant the level of ethical consideration typically given to humans and human culture. A few decades later, the book Silent Spring by Rachel Carson (1962) exposed the devastating environmental effects of pesticides, which later were confirmed to be the cause of drastic declines in Peregrine Falcons (Falco peregrinus) and other raptors (Chapter 13).

In the 1970s, growing environmental concerns spawned the landmark legislation and international treaties that today provide strong legal mechanisms for bird protection. In 1973, the USA enacted its most far‐reaching piece of environmental legislation, the Endangered Species Act (ESA). For the first time, individual species were legally recognized as possessing intrinsic value and rights to protection under law, regardless of how trivial or irrelevant any species might seem to human society. In 1972 the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment helped frame environmental policies and global treaties that eventually led to the Kyoto Protocol for greenhouse gas emissions. Conservation legislation in the European Union also continues to be shaped by milestone legislation that occurred in the 1970s, when the Birds Directive (1979) established a framework for conserving all birds throughout the European Union, banned activities that directly threaten birds, required that hunting be managed sustainably, eliminated non‐selective and large‐scale killing, and closely regulated the trade of live and dead birds.

Today, the most important global treaty for bird protection is the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), drafted in 1973 by the World Conservation Union (now the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, IUCN). This international agreement, to which 175 countries now voluntarily subscribe, binds participating parties to monitor, regulate, or prohibit the international import and export of species deemed in need of global protection. The legal framework for enforcement within each participating country is provided by domestic laws. The heart of CITES lies in three appendices constituting the list of species for which international trade is restricted. Appendix I includes the most endangered species (including for example all macaws, many other parrots, and a few falcons), for which all commercial trade is strictly prohibited and special import/export permits are required for scientific transport. Appendix II lists species that are not in immediate danger of extinction but that could become so in the absence of regulation (for example, all parrots, hawks, and falcons not in Appendix I). Species may be added to or removed from Appendices I and II, or moved between them, only via discussion and vote at periodic CITES conferences. Appendix III lists species added by individual countries that, for any reason, request international assistance in regulating their trade. Without doubt, the international protection afforded by being listed as a CITES species has prevented many birds species from going extinct: until the loss of the last wild Spix’s Macaw (Cyanopsitta spixii) in 2000 (Fig. 15.03), not a single bird species regulated by CITES had become extinct in the wild as a result of international trade.

Fig. 15.03 CITES regulations help preserve wild birds. One of the main benefits of CITES regulations is to ban the import and export of protected bird species. The Spix’s Macaw (Cyanopsitta spixii) is one of the few CITES‐protected bird species that has been extirpated in the wild owing to the captive bird trade. Hope remains that regulated captive breeding of this species will allow its future reintroduction into its former range.

(Photograph by Alain Breyer.)

15.2 Conservation biology

As the disciplines of ecology, population biology, evolutionary biology, animal behavior, and genetics matured during the twentieth century, scientists also began to study the human‐generated threats and biological attributes that were causing many species around the world to decline and go extinct. Gradually, these disciplines coalesced into efforts to derive solutions to conservation problems, giving rise to the applied science now known as conservation biology. Today the field of conservation biology continues to grow in its number of practicing professionals, in the breadth and scope of its research, and in the global importance of its contributions to conservation issues.

Applied sciences like conservation biology generally combine basic principles of several fields to solve everyday problems and to accomplish specific, real‐world tasks. Just as engineers use mathematics, physics, and chemistry to design bridges or fuel‐efficient automobiles, conservation biologists employ basic biological disciplines in the effort to stabilize ecosystems and restore wild populations. Conservation biologists often face grim realities of impending disaster, and they work within ecological systems that differ vastly from one another and contain hundreds or even thousands of species that are engaged in myriad physical and biological interactions. The complexity of interactions among natural populations and the relative youth of the sciences engaged to understand them help explain why so many bird species went extinct between the sixteenth and twenty‐first centuries, before humans could fully recognize the underlying problems and work to ameliorate the threats.

Successful bird conservation involves five integrated steps: (1) understanding the native functions and fluctuations characterizing bird populations, species, and ecological communities; (2) determining whether and how these natural conditions have been, or could be, perturbed by human impacts; (3) projecting how the desired conditions could be restored; (4) taking action for protection and management; and (5) measuring the consequences of alternative management scenarios. Understanding the decline of a bird population requires knowing basic facts about the species’ evolutionary history, its degree of habitat specialization, and what regulates its populations. At the most basic level, all population declines fundamentally reflect changes in birth rates, death rates, and the area of available habitat, or combinations of these three parameters. The task of conservation biology is to pinpoint what has changed for the worse and to devise strategies for eliminating or mitigating those changes.

15.3 Recent avian extinctions

Bird species have been evolving and going extinct throughout their existence (Chapter 2). These past origins and disappearances have been driven by naturally occurring, long‐term processes across the earth’s surface. Continents split apart and came together. Volcanic islands arose from the sea and then eroded away. Earth’s climate fluctuated between hot and cold, wet and dry. Such slow but enormous events made the extinction of species a natural feature of evolutionary change, as local environments shifted and species of different regions encountered and competed with one another. In fact, it is estimated that 99% of all bird species that have ever lived on earth are now extinct. So, why should we be concerned about bird species becoming extinct today?

The answer is simple: the wave of extinction currently underway is occurring at a pace and scale fully comparable to the five greatest extinction episodes in the earth’s history, but this sixth mass extinction is directly caused by human activities across the globe. The physical and biological changes humans have caused on earth are so profound and widespread that a new expression—the Anthropocene—has been coined to describe this epoch in geological terms (Ellis 2011; Steffen et al. 2011). The worldwide spread of modern Homo sapiens has resulted in the extinction of about 8000 species of landbirds, according to recent estimates based on fossil deposits (Martin and Steadman 1999). Most biologists agree that human‐caused extinctions now rival those associated with the events that extinguished the dinosaurs about 65 million years ago (Chapter 2). Such enormous ecological impact is outside the bounds of natural processes and therefore should be a matter of intense concern for all people who care about the natural environment.

15.3.1 Avian extinctions in the Anthropocene

On an evolutionary timescale, modern humans have spread across the globe only very recently from our origins in Africa, but we have had enormous impacts on birds everywhere we have colonized. A great wave of extinctions in Australia, for example, coincided with the arrival of humans on that continent about 50,000 years ago, apparently resulting in part from vastly increased fire frequency (Miller et al. 2005). Similar extinction patterns occurred near the time of human colonization on every land mass on earth except Africa. We cleared forests, replaced grasslands with crops, built towns, drained marshes, filled swamplands, irrigated dry areas, and suppressed natural fire in some places and increased its frequency in others. Everywhere we went, we hunted birds for food, clothing, and ornamentation. In each newly colonized area we encountered birds that had evolved no defenses against our evermore advanced hunting techniques and our steadily increasing numbers. On remote islands filled with uniquely adapted species, we introduced new avian diseases and new predators. On the continents we did the reverse, systematically destroying the largest predators—wolves, bears, and big cats—and thereby releasing cascades of herbivores and middle‐sized predators that altered ecosystems in numerous ways (Prugh et al. 2009). Everywhere, we introduced domesticated herbivores into habitats that had evolved without them. By steadily making the world more accommodating for ourselves, we profoundly altered every natural system we encountered. The effects on birds have been devastating.

Humans began documenting the world’s birds in modern scientific terms—with written records, paintings, and preserved specimens—around AD 1500. By that time, tropical islands the world over already had been ravaged, resulting in the loss of many hundreds of bird species now known only from a few bones or descriptions by early explorers. Many birds on predator‐free islands had lost the need for flight, resulting in the evolutionary reduction of their wings. Included among the pre AD 1500 extinctions are some of the most unusual and spectacular birds ever to have evolved, including the 400‐kilogram Elephant Bird (Aepyornis maximus) on Madagascar (the largest modern bird known) (Fig. 15.04), at least 10 species of moas in New Zealand (Chapter 2), flightless ibises on Hawaii, flightless owls on Caribbean islands, flightless pigeons on Indian Ocean islands, and probably thousands of other island‐dwelling bird species, including numerous flightless rails, worldwide.

Fig. 15.04 The extinct Elephant Bird (Aepyornis maximus) of Madagascar. This was the largest known bird in history, and it briefly coexisted with humans: Elephant Bird remains have been found with traces of human butchery and many eggshells have been found in archaeological fire pits. Single eggs could feed entire human families, and this may be one reason this species went extinct around 1000 years ago—eggs would have been the most vulnerable stage of an Elephant Bird’s life. An Elephant Bird (right) is shown next to an Ostrich (Struthio camelus) (left) for scale.

(© Cornell Lab of Ornithology.)

Humans began populating North and South America less than 20,000 years ago and reached the Caribbean Islands around 6500 years ago. These earliest Native Americans spread rapidly across the hemisphere, introducing wholly new ecological forces that coincided with a spectacularly swift and catastrophic disappearance of animals. Most dramatic was the nearly complete extinction of the New World megafauna, a varied assemblage of large mammals that included horses, camels, giant sloths, mammoths and mastodons, glyptodonts, gomphotheres, saber‐toothed cats, and many others. Why such a large and diverse animal fauna disappeared so suddenly between 12,000 and 8000 years ago remains hotly debated. The tight coincidence between human arrival and the disappearance of the megafauna strongly suggests that humans were a primary cause, perhaps setting in motion a cascade of extinctions compounded by rapid habitat changes, disappearance of keystone species, direct predation by humans, and human‐borne diseases to which the native fauna had no immunity.

Extinction of the western hemisphere megafauna included dozens of species of birds as well as mammals. The most spectacular of these birds included many species of scavengers that lived on the carcasses of large mammals, as African vultures do today. These extinct vultures, condors, and teratorns (giant, soaring scavengers apparently only distantly related to vultures) included some of the largest flying birds ever to have lived. They once occurred throughout the western hemisphere and dwarfed today’s raptors (Fig. 15.05).

Fig. 15.05 Wingspan of Merriam’s Teratorn (Teratornis merriami) compared with living raptors. Similar to modern vultures, the teratorn group (now extinct) scavenged carcasses in open landscapes. However, when the prehistoric megafauna that composed the teratorn diet went extinct around 10,000 years ago, teratorns soon followed. Here, the wingspan of Merriam’s Teratorn is compared with the wingspans of some modern raptors and vultures (three bottom species).

(Illustration by N. John Schmitt.)

Until a few thousand years ago the Caribbean Islands also harbored remarkably diverse assemblages of now‐vanished landbirds, including crows, large flightless owls, numerous macaws, giant parakeets, and nightjars. Bones of these species are found at human archaeological sites dating back only 3000–4000 years (Pregill et al. 1994). Just as they did later across the islands of the Pacific, humans caused a steady disappearance of birds in these fragile tropical islands, both by cutting down the forests and by killing and eating the birds directly. Today, only a small fraction of the original bird fauna persists in the Caribbean, and many of these—including parrots, doves, nightjars, woodpeckers, thrashers, and orioles—are among the most seriously threatened in the world.

15.3.2 Historical extinctions on oceanic islands

As of 2014, the IUCN Red List for birds tallied 130 bird species known to have gone extinct since AD 1500, plus four species classified as “extinct in the wild.” The 198 additional species classified as Critically Endangered include many that have not been sighted in recent decades and which also may be extinct. These modern extinctions demonstrate much about the impacts of humans on the world’s birds. The most obvious pattern is that all but a handful of extinct species were restricted to oceanic islands where the earlier absence of humans and other mammals had left birds especially vulnerable to predation and habitat change.

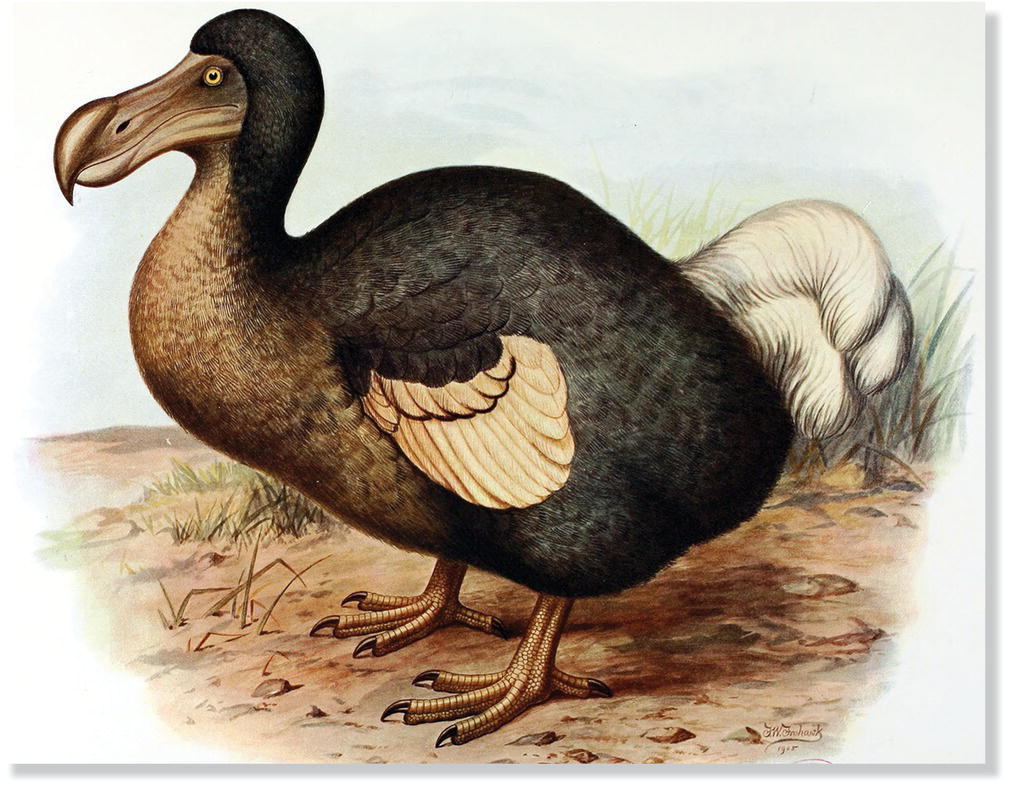

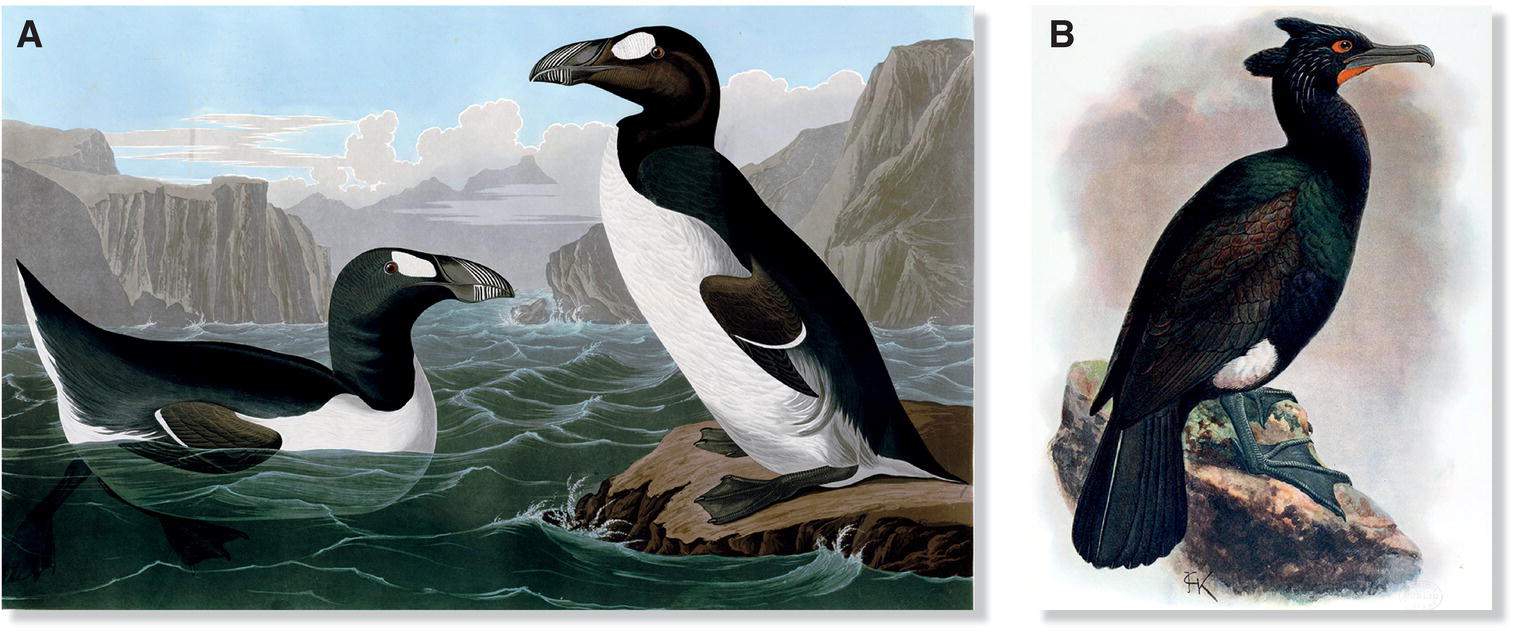

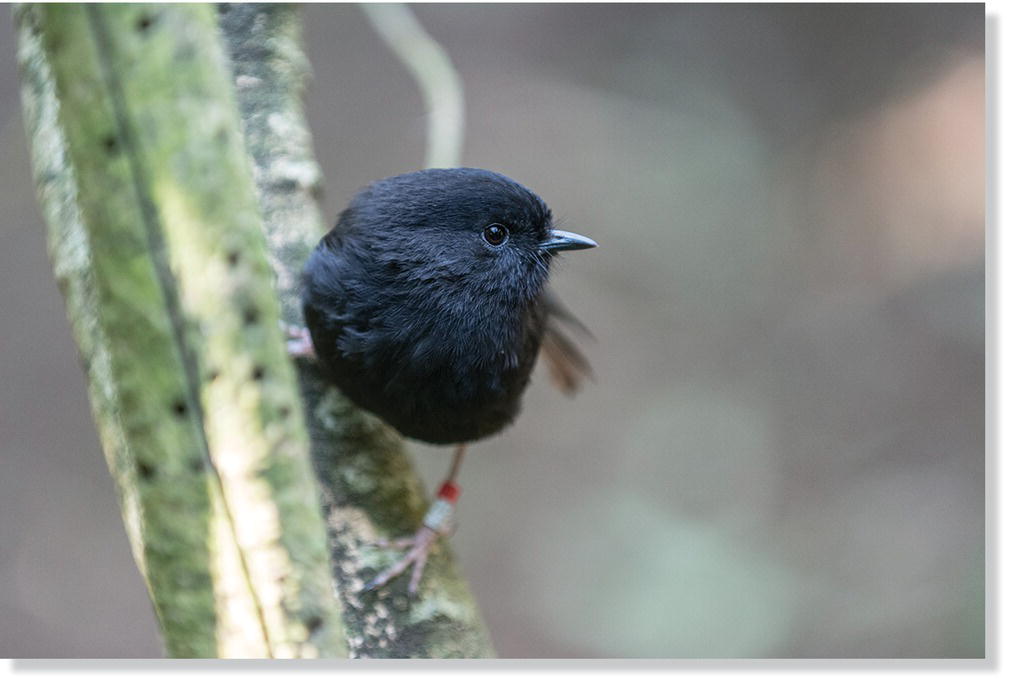

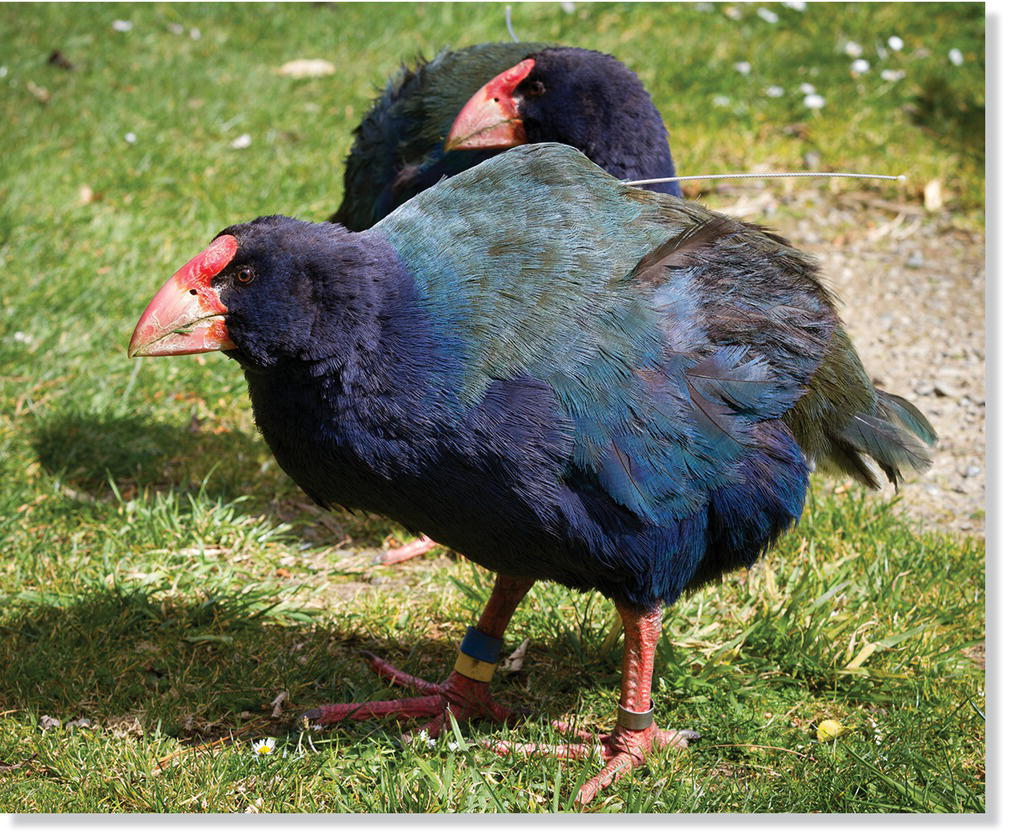

Flightless birds were especially easy prey for humans and their domesticated cats. For example, on Mauritius Island in the Indian Ocean, sailors drove the naïvely fearless Dodos (Raphus cucullatus) (Fig. 15.06) aboard their ships to serve as food for ensuing weeks at sea. The species was last observed in 1662, and not a single whole specimen has been preserved. A close relative of the Dodo, the Rodrigues Solitaire (Pezophaps solitaria), met a similar fate. On another nearby island lived a large and poorly documented bird once called the Reunion “Solitaire” (Threskiornis solitarius); recently uncovered bones show that this extinct bird was not related to the Dodo but rather was an ibis (Mourer‐Cauviré et al. 1995). In the North Atlantic, sailors feasted on the abundant Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis) (Fig. 15.07A), and fishermen even chopped them up to use as bait; the last Great Auk was killed in 1844. In the Bering Sea, Pallas’s Cormorant (Phalacrocorax perspicillatus) (Fig. 15.07B), the largest member of its family, vanished at about the same time, and for similar reasons as the whaling industry expanded across the North Pacific. In the islands of the South Pacific, numerous species disappeared as introduced mammals spread among the islands. Notable among the dozens of species lost from Pacific islands were several species of New Zealand wren (suborder Acanthisitti), an ancient and enigmatic lineage of tiny insectivorous songbirds that had included three flightless species (Fig. 15.08).

Fig. 15.06 Dodo (Raphus cucullatus). This flightless inhabitant of Mauritius Island was an easy target for hungry sailors and the introduced pigs, cats, and rats they left behind. Dodos, along with now‐extinct native tortoises, may have dispersed and enabled the hard‐shelled seeds of several trees to germinate, as their digestive tracts scoured the hard seed exteriors. Introduced tortoises are now employed to help conserve native tree species in place of these extinct species.

(Artwork by Frederick William Frohawk, from Rothschild 1907, public domain.)

Fig. 15.07 Extinct seabirds. (A) Prehistoric Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis) bones, recovered from middens and caves in much of northwest Europe, suggest that they were heavily hunted long before sailors and fisheries destroyed populations off northeastern North America starting in the 1700s. The Great Auk was extinct by 1844. (B) Pallas’s Cormorant (Phalacrocorax perspicillatus), the largest species of cormorant ever known, met a similar fate. Whalers and fur trappers began overhunting populations off the northeastern Russian coast and Rocky Islands around 1750. The species became extinct about 100 years later.

(Artwork by: A, John James Audubon, from Audubon 1827–38, public domain; B, John Gerrard Keulemans, from Rothschild 1907, public domain.)

Fig. 15.08 Bush Wren (Xenicus longipes). Once widespread across New Zealand, populations crashed by the early twentieth century owing to introduced mammalian predators. Small numbers of a distinct subspecies persisted into the 1960s, but the final attempt to relocate them to a predator‐free island failed in 1972.

(Artwork by John Gerrard Keulemans, from Buller 1888, public domain.)

The full list of modern extinctions is dominated by rails, parrots, pigeons, and Hawaiian honeycreepers (Box 15.01). This highly non‐random taxonomy of avian extinction is largely a consequence of the propensity for certain bird groups to colonize oceanic islands and evolve into unique—and vulnerable—island endemics.

15.3.3 Historical extinctions on continents

Continents largely have been spared the massive wave of recent avian extinctions that have occurred on islands, although this trend may be reversing (Butchart et al. 2006b). Avian extinctions are so rare on continents that it is possible to list them all here.

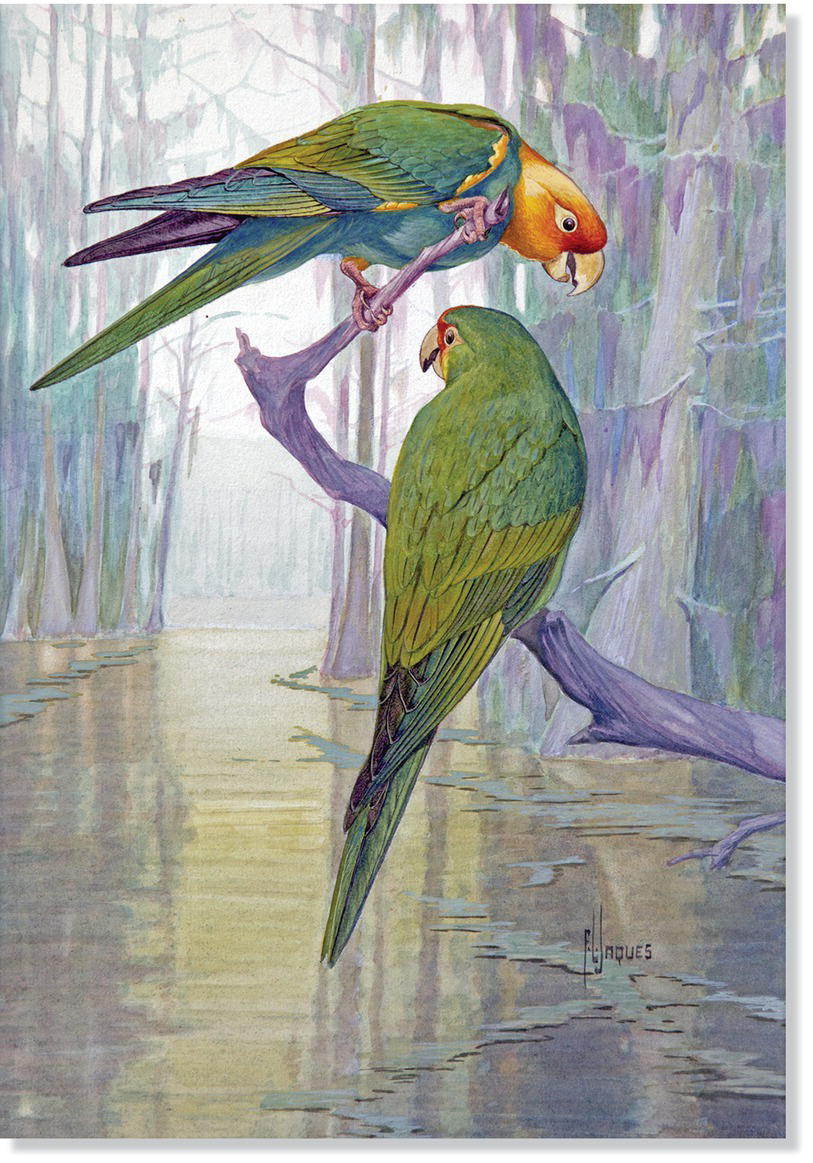

North America has lost the most bird species among continental land masses, with at least three and probably five or six species disappearing since 1850. The Labrador Duck (Camptorhynchus labradorius) apparently bred on rocky islands off the Gulf of St. Lawrence, where it was exposed to plume hunting, egg robbing, and introduced mammalian predators. The last Labrador Ducks were shot in the 1870s, just as Passenger Pigeons (Ectopistes migratorius) were becoming history’s most spectacular example of overexploitation. The Carolina Parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis) declined rapidly throughout the 1800s because of forest clearing and hunting (Fig. 15.09). By 1890 only the most remote forests of central Florida harbored a few parakeets; small flocks were seen through 1915, but reliable reports ceased in the early 1920s. Immense flocks of Eskimo Curlews (Numenius borealis) migrated north through the Great Plains in spring and then southeastward in fall across eastern Canada and the Atlantic Ocean to winter in Patagonia. During spring migration curlews depended on prairie insects, especially in areas recovering after wildfires or bison trampling. By the late 1800s such critical habitat patches were virtually eliminated by agricultural conversion, suppression of wildfire, and annihilation of the great bison herds. Some accounts suggest that migrating Eskimo Curlews relied on enormous swarms of Rocky Mountain grasshoppers, which also mysteriously went extinct around 1900 (Lockwood and DeBrey 1990). A few Eskimo Curlews were collected in South America through the early 1920s, and the last documented occurrence was a single bird photographed near Galveston, Texas in 1962.

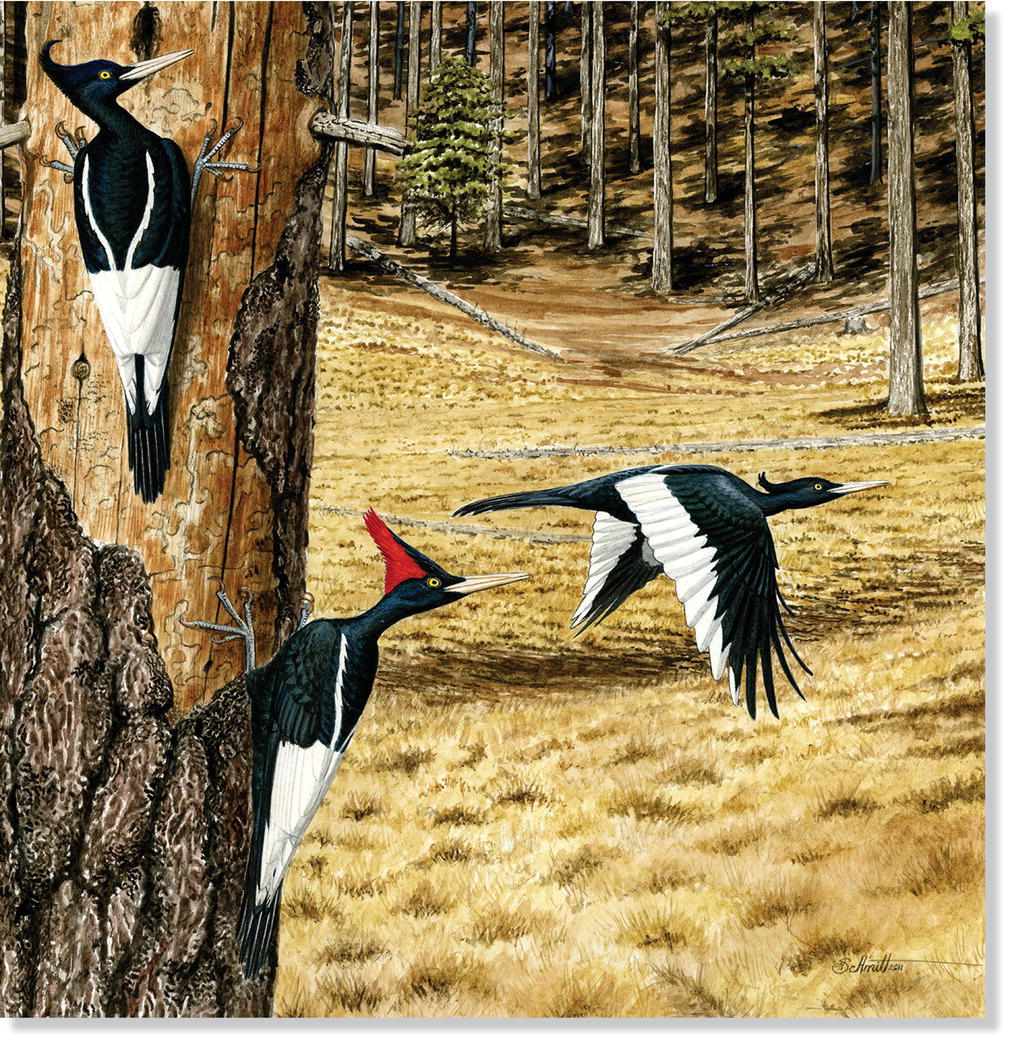

Hopes are now dim for the continued survival of two specialized denizens of the forests and bottomlands of southeastern North America, the Ivory‐billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) and Bachman’s Warbler (Vermivora bachmanii). Ivory‐billed Woodpeckers lived in the treetops of old‐growth pine and bottomland hardwood forests, foraging on beetle larvae by chipping the bark from large, dying trees. These great forests experienced wildfires, floods, hurricane damage, and destruction by massive wintering colonies of Passenger Pigeons, thereby providing copious dead and dying wood, the critical resource for this powerful woodpecker. By the early 1900s the old‐growth forests had been logged, fires were being suppressed, and remnant Ivory‐billed Woodpeckers were being collected as specimens whenever spotted. No Ivory‐billed Woodpecker nest has been found in North America since the 1930s, and the last photographic record from Cuba was in 1956. Credible reports did persist, however, and an intriguing series of encounters in 2004/2005 (Fitzpatrick et al. 2005) spawned a multi‐year, range‐wide search involving hundreds of participants. Nevertheless, no indisputable evidence exists that the species survives today. Bachman’s Warblers preferred dense forest openings and cane thickets, perhaps favoring habitats regenerating after hurricanes. The species declined as forests were converted to farmlands, and the rich floodplains were channelized and drained. Bachman’s Warbler experienced double jeopardy because its sole wintering grounds (Cuba and the Isle of Youth) also underwent rapid habitat conversion into sugar cane plantations. The last confirmed Bachman’s Warbler was a singing male that returned to the same location in South Carolina for three successive breeding seasons in 1958, 1959, and 1960.

Fig. 15.09 Carolina Parakeets (Conuropsis carolinensis). The Carolina Parakeet was the only species of parrot native to the USA and Canada. Though the precise reasons for its extinction remain unknown, extensive hunting, deforestation, and disease are all implicated as potential factors.

(Watercolor by Francis Lee Jaques, courtesy of Madelyn Morey.)

Avian diversity reaches its global peak in Central and South America, but together these continental land masses are known to have lost only five bird species: one resulting from habitat destruction, one from illegal trade, and three from degradation of local wetland ecosystems. The colossal‐sized Imperial Woodpecker (Campephilus imperialis) (a close relative of the Ivory‐billed Woodpecker) occupied old‐growth pine forests of the Cordillera Occidental in western Mexico until these forests were obliterated by logging (Fig. 15.10). The species has not been documented since 1956. The Colombian Grebe (Podiceps andinus) was endemic to a wetland system near Bogotá (especially Lake Tota). Systematic drainage, increased concentration of pollutants, dramatically altered aquatic vegetation, and introduced rainbow trout combined to cause a grebe population collapse in the mid‐twentieth century, and the last individuals were seen in 1977. The flightless Atitlan Grebe (Podilymbus gigas), endemic to Lake Atitlan, Guatemala, met a similar fate during the same time period, apparently accelerated by competition for food from introduced bass. The Slender‐billed Grackle (Quiscalus palustris) was endemic to marshlands in a tiny area of central Mexico which over hundreds of years have been systematically ditched and drained for agricultural uses and urban development. The last free‐flying Spix’s Macaw (Cyanopsitta spixii) disappeared from southeastern Brazil in 2000 (Fig. 15.03). Its decline throughout the twentieth century began with widespread clearing of its forest habitat but was hastened by persistent capturing for illegal trade. Fortunately, this spectacular species persists in captivity, providing hope that someday it can be successfully reintroduced into its native habitat.

Fig. 15.10 Imperial Woodpeckers (Campephilus imperialis). Now extinct, this was the world’s largest woodpecker. The species depended on large tracts of mid‐montane pine‐oak forests in western Mexico. Before the mid‐twentieth century, small social groups were seen foraging on dead trees, although the species was poorly known. The last confirmed birds were observed before logging operations destroyed much of their preferred habitat; hunting and harvesting young were additional factors leading to their extinction.

(Illustration by N. John Schmitt.)

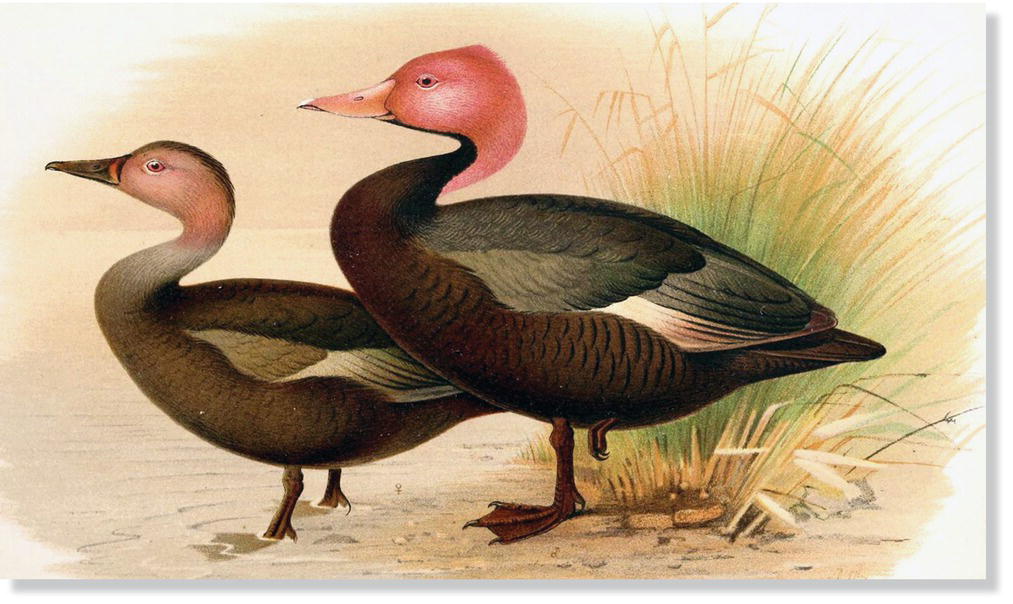

Remarkably, the continental mainlands of Europe, Asia, Africa, and Australia appear to have lost only two bird species among them during recorded history. The mysterious, non‐migratory Pink‐headed Duck (Rhodonessa caryophyllacea) was always rare across the marshlands of the Indian subcontinent (Fig. 15.11). Wetland drainage throughout its limited range hastened its disappearance. Although occasional unsubstantiated reports continue, reliable sightings ceased after 1935. The colorful Paradise Parakeet (Psephotus pulcherrimus) (Chapter 14) once was common in grassy woodlands within a limited range in northeastern Australia but began declining rapidly near the end of the nineteenth century as a result of land clearing, overgrazing, hunting, and predation by introduced mammals. The bird was believed to be extinct for a time and then was rediscovered, but the last confirmed sighting was in 1927. Similarly, the mysterious, nocturnal Night Parrot (Pezoporus occidentalis) of Australia has been reported only a few times in recent decades, and has long hovered around the list of modern avian extinctions. Recent evidence suggests the existence of at least a tiny population in western Queensland (Fig. 15.12).

Fig. 15.11 Pink‐headed Duck (Rhodonessa caryophyllacea). Always considered rare, this species was native to India, Bangladesh, and Myanmar; the last confirmed sighting was in 1935.

(Artwork by Henrik Grönvold, from Wall 1908, public domain.)

Fig. 15.12 Night Parrot (Pezoporus occidentalis). This is an extremely rare, nocturnal parrot that inhabits grasslands and swamps of western Queensland (Australia), feeding mainly on grass seed. Its population status remains a mystery, but a few live birds have been observed recently.

(Photograph by Peter W. Lindenburg.)

15.4 Causes of avian population declines

Except through cataclysmic geological events, extinctions do not happen overnight. Instead, species decline from forces acting over time—from just years in exceptional cases, as with naïve or flightless island birds faced with introduced predators, to decades or longer when the cause is slow conversion of essential habitat. Bird populations are extremely sensitive to changes in the composition, function, and stability of their natural communities and ecosystems. Devising conservation solutions requires first identifying the forces that are causing the declines, most of which fall into two interacting categories: extrinsically imposed stressors or threats (nowadays mostly brought about by humans) and intrinsic biological attributes that provide evolutionary advantages under natural conditions but can make a species vulnerable as environmental conditions change.

15.4.1 Demography, habitat, and life histories

All populations fluctuate year to year, but average numbers can remain stable over time because average birth rates and death rates are balanced. As covered in more detail in Chapter 13, the scientific study of birth rates and death rates, called demography, plays an enormous role in conservation biology. Age‐specific birth rates and death rates specify, for individuals at each age, their average number of offspring produced and their probability of dying. Age‐specific death rates compound to produce a schedule of survivorship, the probability of being alive at a given age. Population stability over any given time period requires that, on average, the total accumulated reproductive output from all age classes matches the number of deaths occurring during that same period. Therefore, understanding the factors that affect birth rates and death rates is essential in conservation research.

The word habitat also holds a crucial place in conservation biology and refers to the comprehensive range of physical, biological, and geographic conditions required by individuals of a given population in order to survive and/or reproduce. As discussed later, bird species vary considerably in their tolerance limits for environmental conditions. Conservation biologists devote enormous effort to understanding in detail the extent and nature of these habitat tolerances. Conservation practitioners devote similarly huge efforts to ensuring that sufficient habitat area exists and is properly managed.

All bird populations have an evolutionary history. In adapting to the range of environmental conditions characterizing its habitat, every population evolves numerous life history traits that provide survival and reproductive advantages within that habitat (Chapter 13). For birds, some of the most important variables relevant to conservation are the period of nest dependency, period of juvenile dependency, age at first breeding, mating system, age‐specific clutch size, reproductive lifespan, and dispersal/migration pattern. Understanding long‐term changes in population numbers requires identifying how environmental changes interact with these life history attributes to cause changes in birth rate, death rate, and distribution of suitable habitat, or a combination of these factors.

15.4.2 Habitat specialization and the six forms of rarity

Outright habitat loss obviously leads to population decline for any species that depends on that habitat, but not all species are affected equally. Certain species are more vulnerable than others when native habitats disappear. Rare species generally are more vulnerable than common ones, but what exactly does “rare” mean? Most species thought of as naturally rare actually are (or once were) reasonably common in one or a few localized areas and may have very specific habitat requirements. Protecting their local geographic centers or special habitats may be sufficient to ensure these species’ survival, but if these primary centers of occurrence have been destroyed, then protecting such species is extremely challenging. Identifying the nature of a target species’ rarity is a critical step in designing its protection and recovery.

Three features of a species’ distribution affect its vulnerability: its overall geographic distribution (range size); the overall numbers of the species within its range (population density); and the spectrum of habitats in which the species can live and breed (habitat specificity). Deborah Rabinowitz et al. (1986) categorized British plants according to these three variables to produce a simple framework for identifying seven different forms of rarity, six of which are relevant to birds (Fig. 15.13). Below we describe these six forms of rarity and give examples of endangered birds that fit each category:

Fig. 15.13 Six forms of rarity in birds. Geographic distribution (large or small), local abundance (high or low), and habitat specialization (generalist or specialist) are all factors that influence vulnerability. Species in category 6—which are highly specialized with small populations and a narrowly local range—typically have the greatest risk of extinction.

(From Rabinowitz 1981. Reproduced with permission from John Wiley and Sons.)

Rarity form 1: Widely distributed, small local populations with broad habitat tolerance

Most continental raptors fit this category, which explains why few other than the very largest eagles appear on endangered lists. Being at the top of the food chain, hawks and owls generally have large home ranges and consequently low population densities. The Crowned Hawk‐Eagle (Stephanoaetus coronatus) (Fig. 15.14) of sub‐Saharan Africa is the second largest eagle on that continent and recently was moved to a higher risk category by the IUCN because, although the bird occurs across a wide range of forested habitats, its populations suffer persecution from local farmers. The Lesser Kestrel (Falco naumanni) breeds in a variety of open habitats across Europe and Asia, and winters broadly across Africa. Once listed as Vulnerable because intensifying agriculture and pesticide use caused sharp declines across its entire breeding range, the species has rebounded since 2000 and recently was reclassified as Least Concern (BirdLife International 2016a).

Fig. 15.14 Crowned Hawk‐Eagle (Stephanoaetus coronatus). As one of the largest and most powerful eagles of Africa, the Crowned Hawk‐Eagle is a species of increasing concern because of habitat destruction, hunting, and trapping. Although this species is a widespread, generalist predator, its population density is low even in patches of preferred habitat, which makes it vulnerable.

(Photograph by Peter R. Steward.)

Rarity form 2: Widely distributed, large local populations with narrowly specialized habitat requirements

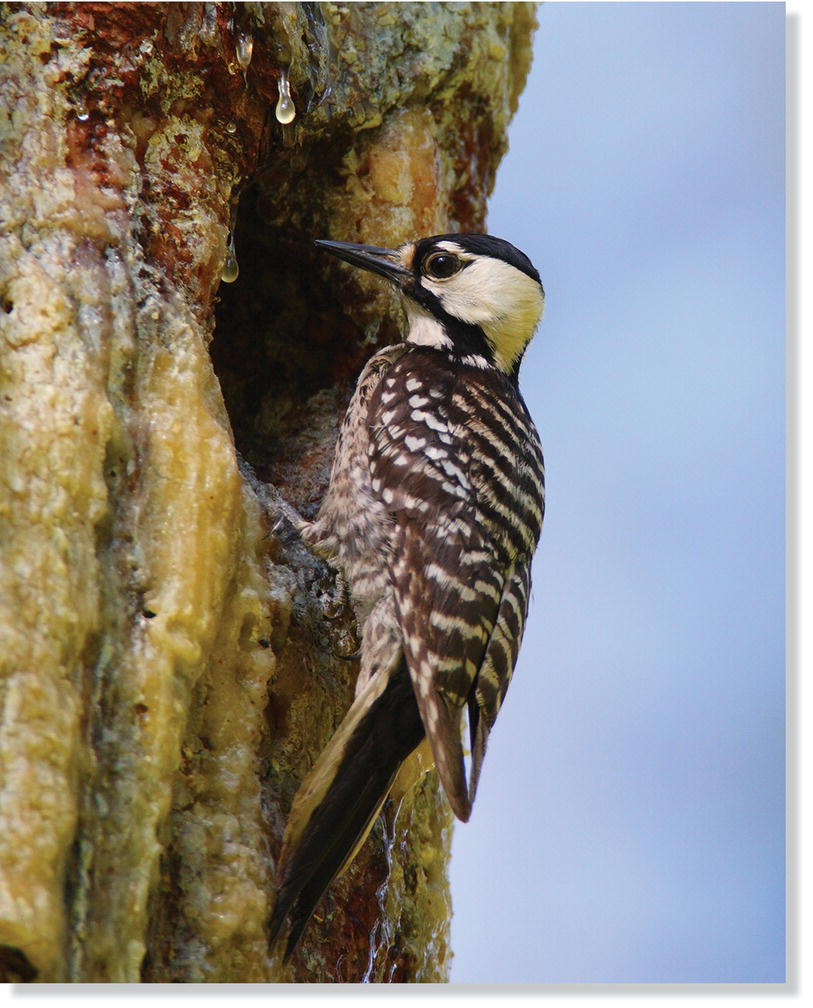

Numerous declining bird species fit this category as humans reduce and fragment populations of once‐widespread ecological specialists. Red‐cockaded Woodpeckers (Picoides borealis) originally were common in old‐growth pine savannas across the entire southeastern USA (Fig. 15.15). This cooperative‐breeding woodpecker nests in cavities excavated high on the trunks of living pines and protects its nests from predation by snakes and small mammals by drilling tiny “resin‐wells” into the surrounding bark, producing a barrier of sticky pine pitch. Red‐cockaded Woodpeckers nest almost exclusively in mature long‐leaf pine stands in which fungus renders the center of certain trunks soft enough to hollow out. They also require an open, grassy understory and gradually disappear from pine forests that are not burned regularly. Therefore, populations persist today only in well‐managed locations where mature pine stands remain uncut and are burned every 2–3 years. Oilbirds (Steatornis caripensis) are found broadly across the tropical forested regions of northern South America, but they are locally common only at their widely scattered breeding colonies. These nocturnal birds have a highly specialized breeding habitat, as they nest only within large, dark caves (Chapter 12).

Fig. 15.15 Red‐cockaded Woodpecker (Picoides borealis). An endemic of the southeastern USA, this species is locally common, but highly specialized on long‐leaf pine forests that depend on frequent burn cycles to remain healthy. As primary cavity excavators, Red‐cockaded Woodpeckers provide a service to numerous other secondary cavity‐nesting species.

(Photograph by Juli Wells.)

Rarity form 3: Widely distributed, small local populations with narrowly specialized habitat requirements

Small population size combined with habitat specialization render species in this category vulnerable despite their broad geographic ranges. Piping Plovers (Charadrius melodus) (Fig. 15.16) breed on barren sandy beaches from central Canada and the Great Lakes east to the Atlantic coast of North America, but even the largest of these beaches rarely harbors more than two or three pairs. Its narrow habitat tolerance places the species directly in competition with humans, who also love sandy beaches. Consequently, Piping Plovers always will be vulnerable simply because of insufficient breeding habitat free of human disturbance, and the species now depends on active protection of nest sites by humans. A recent analysis suggests that this species will be particularly vulnerable to rising sea levels and storm surges resulting from climate change (Seavey et al. 2011). The endangered White‐headed Duck (Oxyura leucocephala) (Chapter 3) breeds in scattered populations across Europe and western Asia on small, semipermanent or temporary lakes that have extensive areas of shallow water with fringes of dense emergent vegetation and pondweeds. Numbers have plummeted because of wetland draining, pollution, and hybridization with Ruddy Ducks (Oxyura jamaicensis) introduced from North America (Muñoz‐Fuentes et al. 2007) (Chapter 3).

Fig. 15.16 Piping Plovers (Charadrius melodus). A recently hatched Piping Plover nestling is guarded by its parent. This species exists only in small, local populations. It prefers to nest in sparsely vegetated sandy beaches, making it vulnerable to coastal development, introduced predators, and rising sea levels related to climate change.

(Photograph by Brendan Toews Photography.)

Rarity form 4: Small geographic range, large local populations with broad habitat tolerance

This form of rarity is often seen in bird species that are restricted to islands, where they may have small global population sizes despite being common within their restricted range. For example, the Gray Trembler (Cinclocerthia gutturalis), an odd member of the mockingbird family that gets its name from its habit of quivering its body and tail while singing, is found only on the islands of Martinique and St. Lucia in the Lesser Antilles (Fig. 15.17). The global range of the Gray Trembler is therefore small, but within those islands the species is relatively common across a range of habitat types, from lowland dry scrub to high‐elevation tropical forest.

Fig. 15.17 Gray Trembler (Cinclocerthia gutturalis). Island species like the Gray Trembler may be quite common in their native range and occupy a variety of habitats, but they are vulnerable because their global range is small.

(Photograph by Ed Schneider.)

Rarity form 5: Small geographic range, large local populations with narrowly specialized habitat requirements

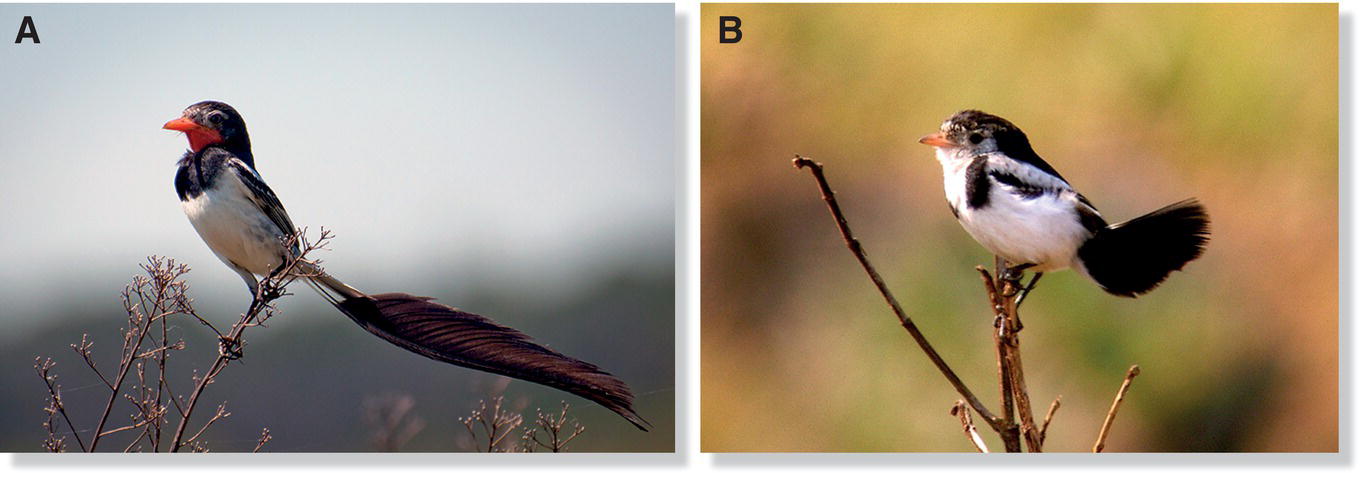

This category probably contains the largest proportion of at‐risk bird species around the world. Most geographically restricted species, even those with narrow habitat tolerances, can be locally common in places where their specific habitat needs are met. However, they easily become threatened if those habitats are altered. For example, the spectacular Strange‐tailed (Alectrurus risora) and Cock‐tailed (Alectrurus tricolor) Tyrants remain locally common within their limited ranges in grasslands of southeastern South America (Fig. 15.18). However, global numbers of both species are plummeting, as are those of many other grassland specialists, because of agricultural conversion and persistent burning of grasslands for livestock foraging (Di Giacomo et al. 2011). All around the world, bird species in this important category of rarity depend on the protection and long‐term management of habitat patches within their respective native ranges.

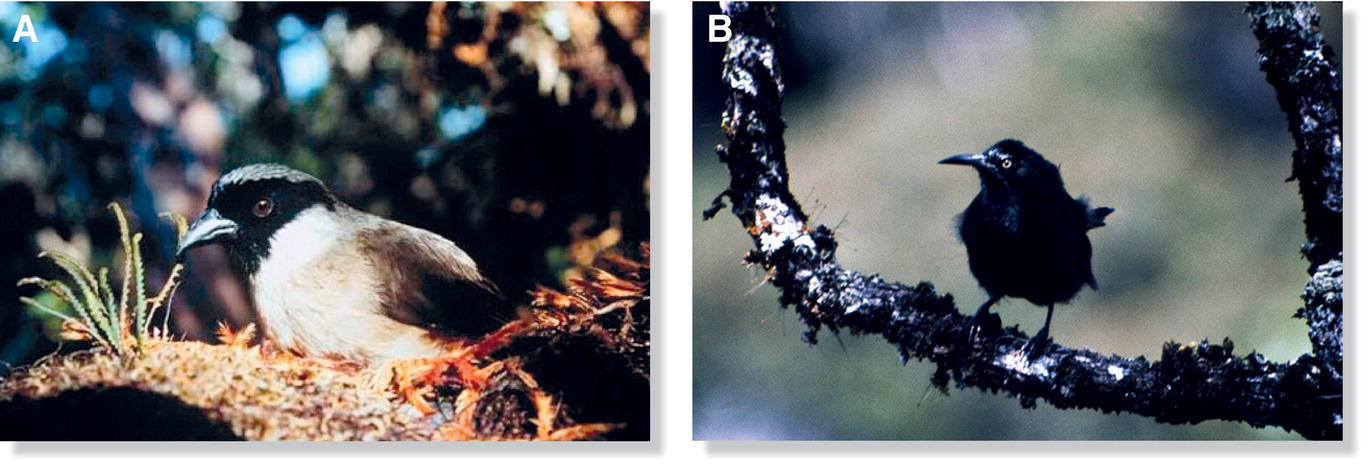

Fig. 15.18 Two at‐risk South American flycatchers. Species around the globe are vulnerable to extinction when they are locally common but highly specialized and limited to a small geographic range. (A) The Strange‐tailed Tyrant (Alectrurus risora) requires tall‐grass marsh habitat. (B) Similarly, the Cock‐tailed Tyrant (Alectrurus tricolor) occurs in limited areas of humid and seasonally dry tall‐grassland habitats. Both are threatened by rapid agricultural and grazing habitat conversion.

(Photographs by: A, Cláudio Dias Timm; B, Scott Olmstead, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Cock‐tailed_Tyrant_(Alectrurus_tricolor)_perched.jpg. CC‐BY‐SA 2.0.)

Rarity form 6: Small geographic range, small local populations with narrowly specialized habitat requirements

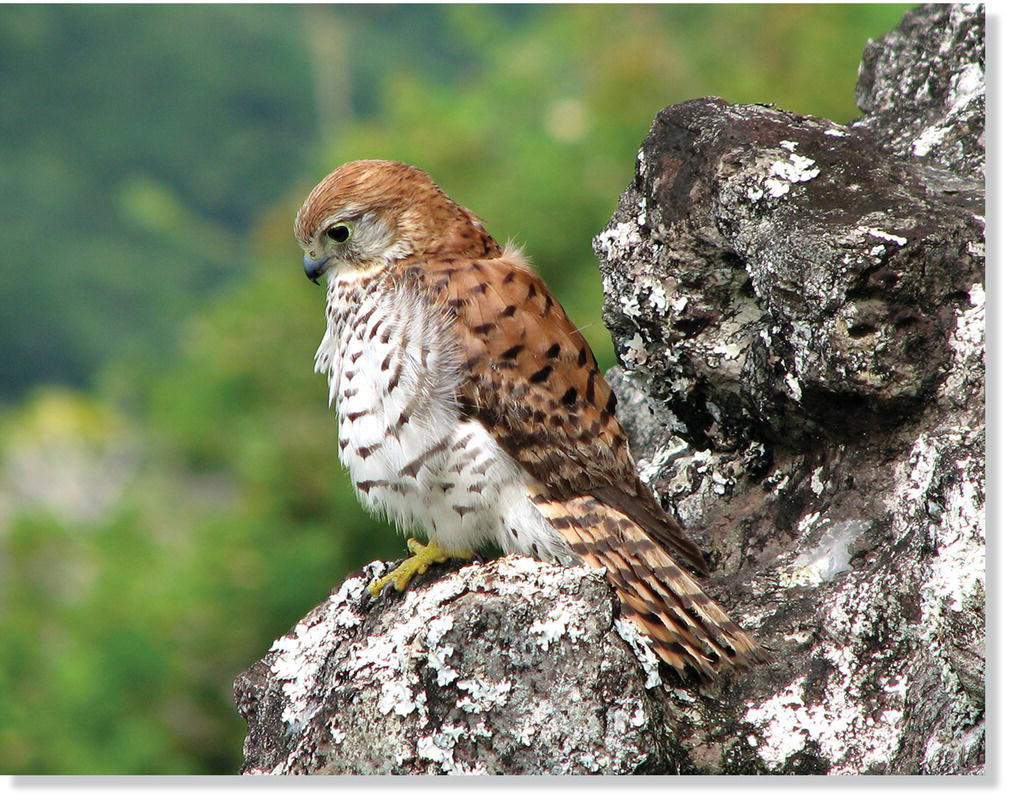

Species in this category are the world’s most vulnerable, because local perturbations or catastrophes can extinguish them immediately. Temperate zone habitats of North America and Eurasia contain few avian examples, because most birds on these large continents have large ranges compared with other, more sedentary and vulnerable groups of organisms such as plants, stream fishes, freshwater mollusks, and cave‐dwelling arthropods (Stein et al. 2000). Throughout the world’s tropical realms, however—both on islands and on continents—many ecologically specialized and locally endemic birds also have naturally low population densities. Such species are vulnerable to every threat discussed in this chapter. Examples include numerous island‐endemic species of hawks, owls, and nightjars, such as the Mauritius Kestrel (Falco punctatus), Seychelles Scops‐Owl (Otus insularis), and Puerto Rican Nightjar (Antrostomus noctitherus). Many bird species similarly occupy tiny ranges on isolated mountain ridges across the world’s tropics, and those having low population densities, such as Bannerman’s Turaco (Tauraco bannermani) (Fig. 15.19) of western Cameroon, are especially at risk as forests are cleared.

Fig. 15.19 Bannerman’s Turaco (Tauraco bannermani). Among the rarest and most vulnerable species in the world, Bannerman’s Turaco is range restricted, locally rare, and highly specialized. Tropical species such as this turaco are particularly at risk because of their dependence on habitats that occur only in a single geographic area, which are easily lost to habitat conversion.

(Photograph by Paul Ellis.)

15.5 Major threats to bird populations

The IUCN recognizes 11 categories of threats facing the world’s living species (IUCN 2012). These IUCN categories differ widely from one another in how and where they affect birds (Box 15.02). Several of the IUCN categories lump extremely important human‐caused threats to birds together under a single designation. For example, direct hunting and killing are lumped together with timber extraction, under the heading “Biological resource use.” Here we describe the most important threats causing bird population declines.

15.5.1 Habitat loss

The most pervasive cause of avian population declines worldwide is loss of suitable habitat. All birds have unique adaptations that allow them to take advantage of specific and predictable features of their habitat. Humans have continually changed the structure, composition, and distribution of habitats, eliminating some and grossly changing others, but we cannot change the fundamental requirements of the bird species that use these habitats. For example, across North America, Europe, and Asia native prairies and steppes have been converted to grow grain crops or introduced forage grasses, thereby reducing population sizes of the grassland larks, pipits, shrikes, sparrows, and buntings that rely on native grassland habitats. By draining wetlands to create more areas for grazing or cultivation, humans similarly have reduced the total number of ducks, grebes, and shorebirds. Forests have been cleared for timber, agriculture, and livestock; coastlines and shorelines have become centers for residential and commercial development; and native scrubs have been replaced with pines and eucalyptus. All such cases of widespread habitat modification have resulted in dramatic declines among the birds adapted to the orginal habitats.

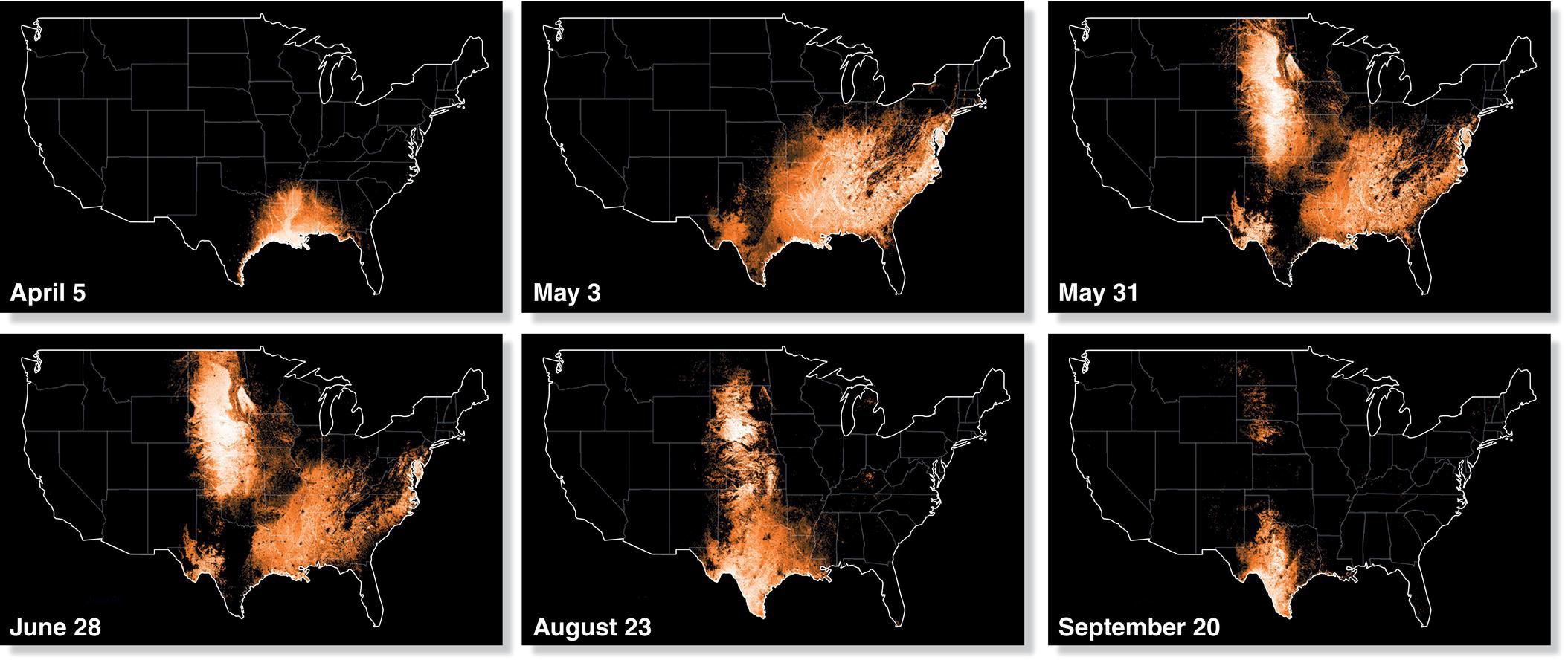

Worldwide, forest habitat continues to be lost at an unsustainable rate, especially in the tropics, and the loss of forest is a particularly prominent conservation concern (Fig. 15.20). Indonesia, for example, supports the third‐largest expanse of tropical forest in the world, at almost 100 million hectares; only the forests of Amazonia and the Congo Basin are larger. A recent report found that Indonesia's rates of forest clearing and conversion to oil palm plantations are accelerating, placing it among the five countries with the highest percentage of primary forest loss (Wich et al. 2011). Indonesia’s numerous tropical islands harbor hundreds of locally endemic forest birds, almost all of which are declining as their habitat is converted. On Madagascar a number of birds are similarly poised on the brink of extinction because of the centuries‐long conversion of the island’s habitats into vast grazing lands and rice paddies. The Madagascar Serpent‐Eagle (Eutriorchis astur) (Fig. 15.21), suspected to be extinct since the 1930s, was rediscovered in the early 1990s but exists only as a tiny population in a remote forest tract at the northeastern corner of the island. Owing to the evolutionary uniqueness of the flora and fauna of Madagascar (Chapter 3), considerable international assistance has been focused on helping its government identify the best remaining patches of native habitat and secure them as ecological preserves. Today, however, a tremendous increase in illegal logging threatens to undermine these efforts (Randriamalala and Liu 2010).

Fig. 15.20 Forest turnover worldwide. Using high‐resolution satellite imagery, this map characterizes forest extent (green), gain (blue), loss (red), and both gain and loss (magenta) from 2000 to 2012. During this 12‐year study, 2.3 million square kilometers of forest were lost, and 0.8 million square kilometers were gained (through regrowth and planting initiatives). Deforestation in the tropics is of particular conservation concern; the extent of tropical forest at the turn of the twentieth century was twice that of today.

(From Hansen et al. 2013. Reproduced with permission from AAAS.)

Fig. 15.21 Madagascar Serpent‐Eagle (Eutriorchis astur). This rare eagle persists only because some of its important lowland Madagascar forest habitats have been protected by international conservation efforts. Unfortunately, illegal logging continues throughout Madagascar, leaving this bird’s future uncertain.

(Photograph by Russell Thorstrom.)

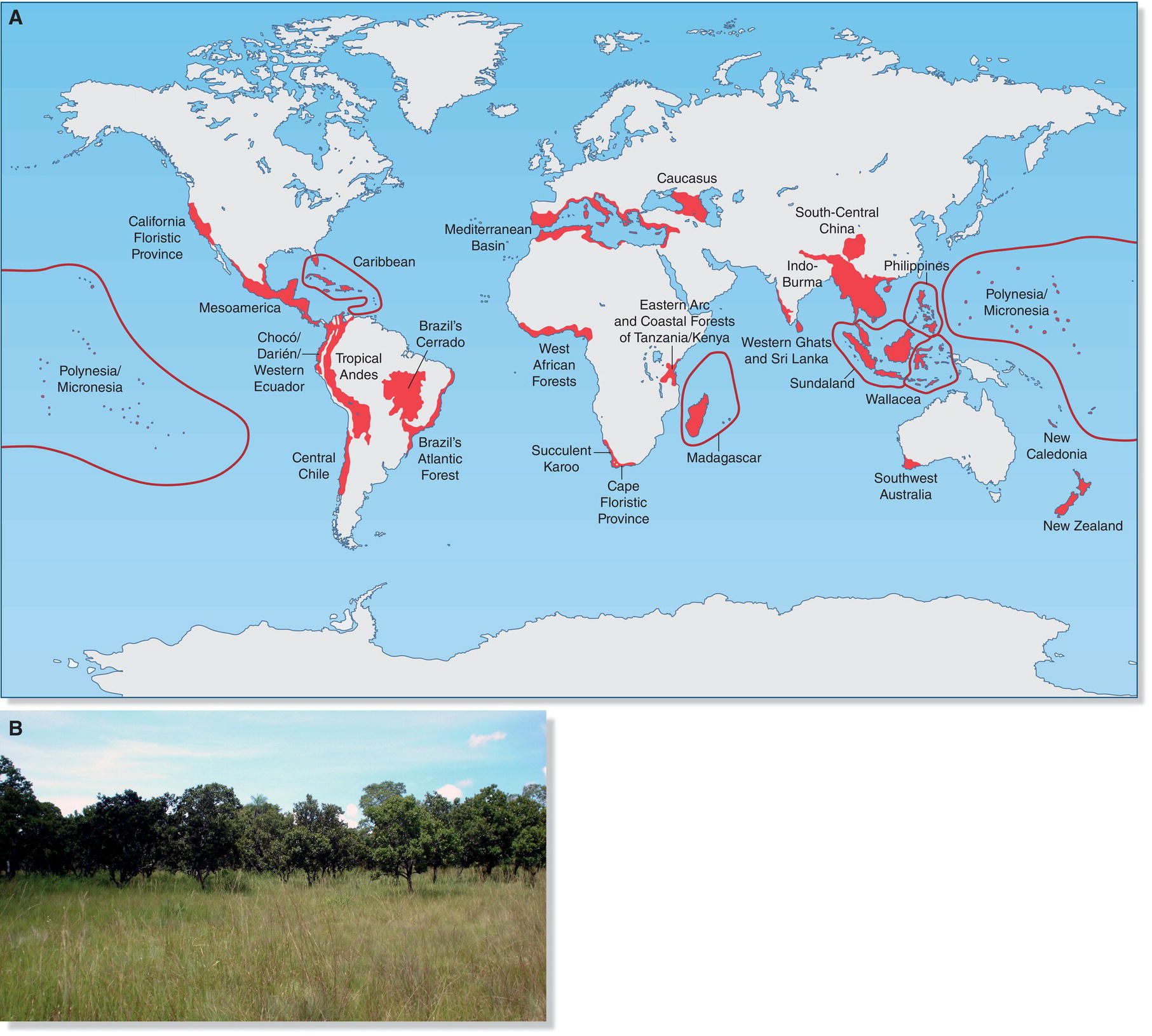

Non‐forest habitats are mentioned less frequently than forest in most discussions of habitat loss, but many such habitats are also at the highest level of conservation concern. For example, arid habitats in the wheatbelt region of Western Australia, part of which is recognized formally as a National Biodiversity Hotspot, face continued pressure from agriculture and other stressors that threaten its many endemic species. The Brazilian cerrado similarly ranks among the 25 global biodiversity hotspots (Myers et al. 2000), and almost 5% of its more than 770 bird species are endemics (Fig. 15.22). Two‐thirds of the cerrado’s original extent has been converted to agriculture (mainly soybeans) over the past 40 years (Cavalcanti and Joly 2002). Estimates suggest that the cerrado could be gone entirely by 2030, and progressive extinctions of its avifauna will have detrimental effects on the functional ecology of central Brazil (Batalha et al. 2010).

Fig. 15.22 Biodiversity hotspots. (A) Habitats with a large proportion of endemic species—those found nowhere else on earth—are considered the highest priority for conservation action. Saving these hotspot habitats protects species that are at high extinction risk. (B) Many hotspots, including this Brazilian cerrado, are threatened because of agricultural conversion and human encroachment.

(A, from Myers et al. 2000. Reproduced with permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd. B, photograph by Benjamin G. Freeman.)

15.5.2 Habitat fragmentation

One of the most widespread patterns in nature is that larger islands hold more species than smaller islands, in part because population size tends to mirror island size, and because small populations tend to go extinct from random fluctuations more easily than large ones. In addition, larger islands contain a greater diversity of habitat types than smaller islands, thereby providing niches for more kinds of species. The importance of this species–area relationship (Chapter 14) goes far beyond its explanatory power for biodiversity on islands: virtually all continental habitats around the world now are subdivided into a mosaic of island‐like patches.

By converting native forests, grasslands, scrubs, and deserts into patchworks of landscapes designed for our own use, humans create habitat islands of different sizes, at differing distances from one another, and separated by different intervening habitats than would occur naturally. Persisting as islands, remnant patches of native habitat can be isolated as thoroughly as if they were surrounded by water. Just as on oceanic islands, habitat islands inevitably begin to lose their bird species.

Loss of species from habitat patches following isolation has been demonstrated by hundreds of studies around the world over the past 50 years. One of the most consistent patterns is that species with the smallest populations disappear first. In Java, for example, after the Bogor Botanical Garden arboretum had been isolated for 50 years, it had lost 75% of the bird species with originally small populations, but the species that were more common largely persisted (Diamond et al. 1987). In Panama, nearly 50% of the original bird community disappeared from the island of Barro Colorado after it was formed by the flooding of Gatun Lake during construction of the Panama Canal (Chapter 14). The birds that disappeared first were those with naturally low population density, such as ground‐cuckoos, raptors, and woodpeckers (Willis 1974; Robinson 1999).

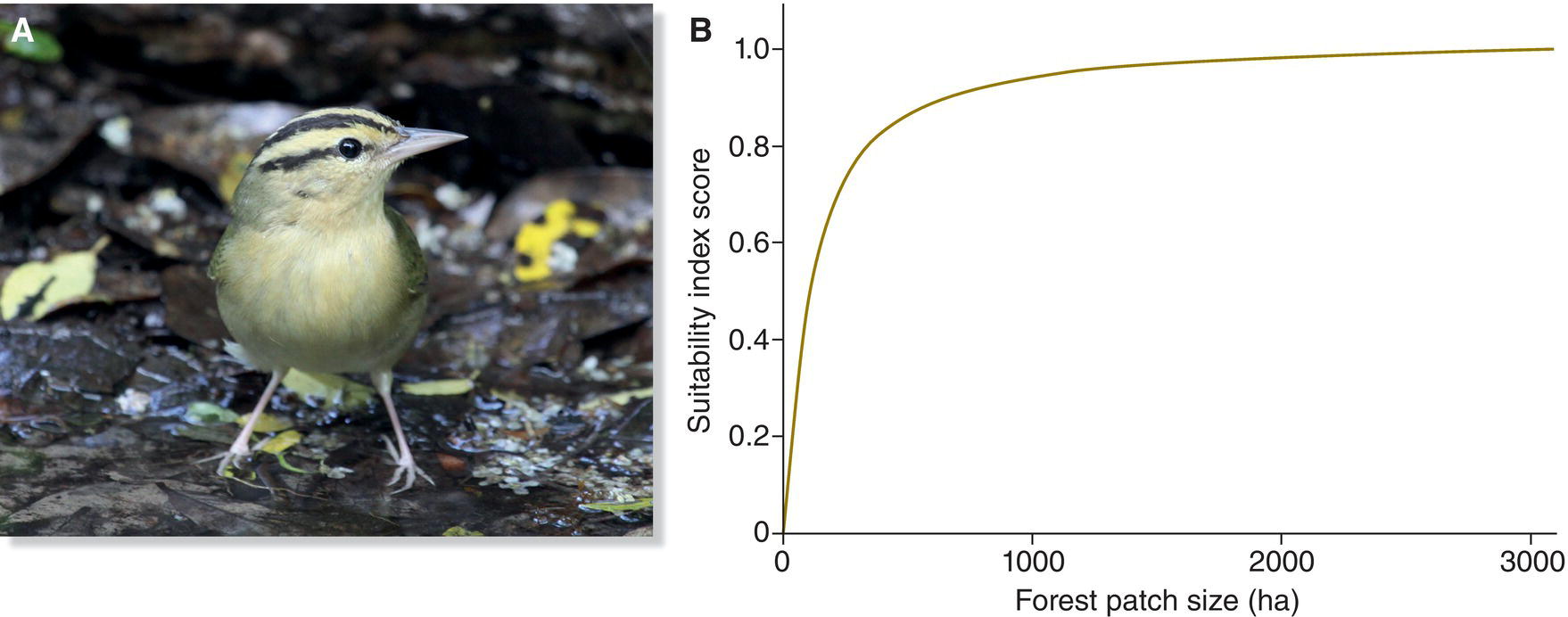

Species that require the largest tracts of habitat in order to breed successfully and persist are termed area‐sensitive species. In eastern North American forests, Wood Thrushes (Hylocichla mustelina), Eastern Wood‐Pewees (Contopus virens), and Red‐eyed Vireos (Vireo olivaceus) are sensitive only in regard to tracts below about 20 hectares and occur in most tracts above this size. In contrast, species such as Pileated Woodpeckers (Dryocopus pileatus) and Worm‐eating Warblers (Helmitheros vermivorum) require much larger tracts, and their frequency increases steadily with patch size, even above 1000 hectares (Fig. 15.23). Therefore, tracts of considerable size are required to preserve the complete community of woodland bird species.

Fig. 15.23 Some species require large forest tracts. (A) The Worm‐eating Warbler (Helmitheros vermivorum) is one of many species that requires large areas of intact, primary forest to sustain healthy breeding populations. (B) The larger the area, the greater the habitat suitability index for this species.

(A, photograph by Andrew Jordan. B, from Tirpak et al. 2009.)

Grassland birds also exhibit area sensitivity. In agricultural regions, remnant patches of native grassland may form habitat archipelagos amid encroaching oceans of alfalfa, grain crops, or soybeans. As a result, grassland species all over the world are deeply threatened. Species having the lowest population densities are threatened most severely, a problem compounded by the fact that density itself is area sensitive—that is, many grassland birds occur at the highest densities within the largest tracts of good habitat (Ribic et al. 2009). Birds such as stone‐curlews and sandgrouse in Europe (Goriup et al. 1991), prairie‐chickens and Sprague’s Pipits (Anthus spragueii) in North America, and seriemas and rheas in South America are failing to persist in any but the very largest islands of native grassland. Almost all the world’s bustards (Fig. 15.24) and other birds of the Asian shrub‐steppes are declining, even in areas where they are protected (Bota et al. 2005). Protecting the largest remaining expanses of native grassland has emerged as an urgent global priority for bird conservation.

Fig. 15.24 Grassland birds are declining worldwide. This Indian Bustard (Ardeotis nigriceps) is one of the many bustards that face extinction due to hunting and habitat destruction. Fewer than 250 individuals of this species remain in the wild.

(Photograph by Nitin Vyas.)

Compounding problems of habitat fragmentation are edge effects, or factors causing habitat near the edge of a patch to be less suitable for survival or reproduction than habitat in the middle. For birds, the most important edge effects are: (1) changes in microclimate (sunlight, temperature, and humidity) near a habitat edge, which can affect plant composition, habitat structure, and prey abundance; (2) introduced plants and animals, which penetrate habitat fragments and alter their characteristics near the edge; (3) increased frequency of habitat disturbance such as fire or wind damage; (4) greater numbers of generalist or edge‐using mammalian and avian predators; and (5) elevated brood parasitism, especially by cuckoos (in the Old World) and cowbirds (in the New World). For example, in forest fragments of southern Illinois (USA), 50–100% of songbird nests are parasitized by cowbirds, and 70–99% are destroyed by predators before hatching (Brawn and Robinson 1996). Edge effects are especially pronounced in tropical forests, where they can be the dominant influence affecting community composition in fragmented habitats (Laurance 2008).

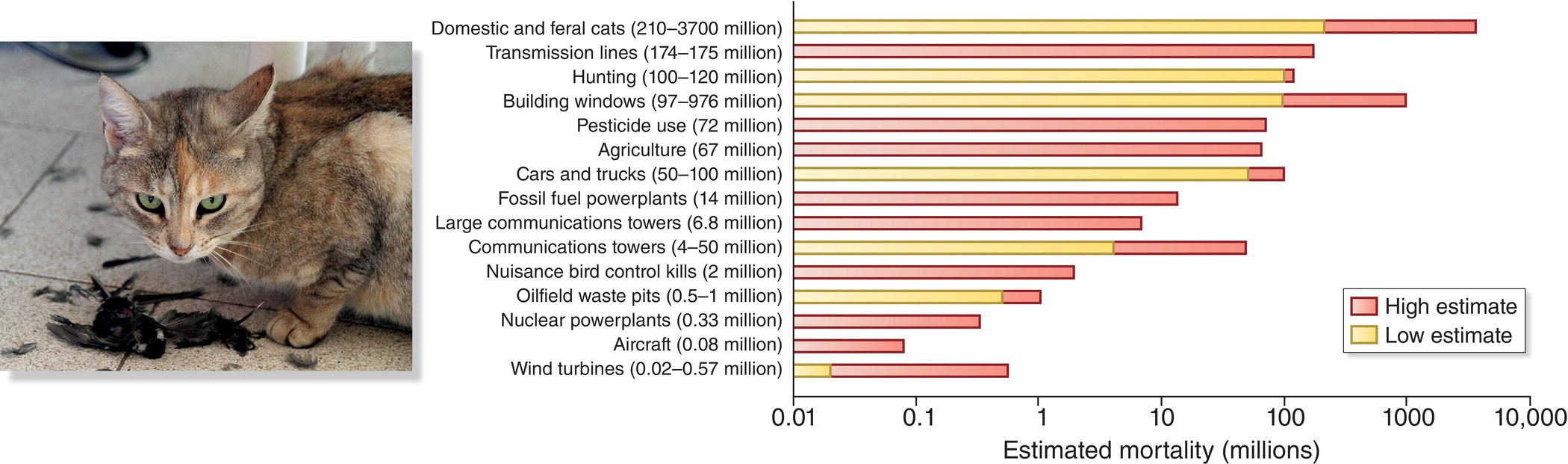

15.5.3 Introduced predators

The introduction of new predators into habitats previously lacking them ranks among the most pervasive threats to birds all over the world. Rats, cats, mongooses, stoats, and ferrets are the most widespread and notorious culprits, but the full list is long and even includes reptiles such as monitor lizards and snakes. As noted elsewhere, the problem is especially acute on islands where many native birds evolved flightlessness, have few defensive behaviors against predators, or nest on the ground. Even on continents, however, non‐native predators (especially domestic cats) kill millions of birds annually, causing population declines and local extirpations (Loss et al. 2013).

Oceanic islands across the Pacific once provided predator‐free breeding places for millions of seabirds comprising dozens of species of petrels and shearwaters, albatrosses, terns, boobies, frigatebirds, tropicbirds, and cormorants. During recent decades, huge populations of invasive rats and cats have caused precipitous population declines, endangerment, and extinction on these islands. On Kiritimati (formerly called Christmas Island), cat eradication measures have failed, and black rats recently arrived. Seabird numbers have dropped by half, and the largest remaining population of the endangered Phoenix Petrel (Pterodroma alba) is in grave danger of extinction (BirdLife International 2016b). A comprehensive analysis of seabird–rat interactions worldwide shows that storm‐petrels and other burrow‐nesting seabirds are by far the most vulnerable, and that gulls and other ground nesters are less so (Jones et al. 2008).

In Madagascar, the introduction of exotic fish into Lake Aloatra is blamed for the loss of the endemic Alaotra Grebe (Tachybaptus rufolavatus), which has not been seen since 1985 and was declared extinct in 2010. A similar fate appeared to befall the Madagascar Pochard (Aythya innotata), but a tiny population was rediscovered in 2006 on Lake Matsaborimena in northern Madagascar, and a captive‐rearing program has been undertaken to restore its numbers.

15.5.4 Direct exploitation

The most blatant cases of human‐induced population declines are those in which adults were killed at such a scale that the birth rate of new recruits could not compensate for the death rate imposed by humans. Familiar examples involved killing of adults for food—as for the Dodo (Raphus cucullatus), Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius), and Eskimo Curlew (Numenius borealis)—or ornamentation, as for egrets and herons. At least 857 bird species are currently at risk from direct hunting or trapping (IUCN 2012).

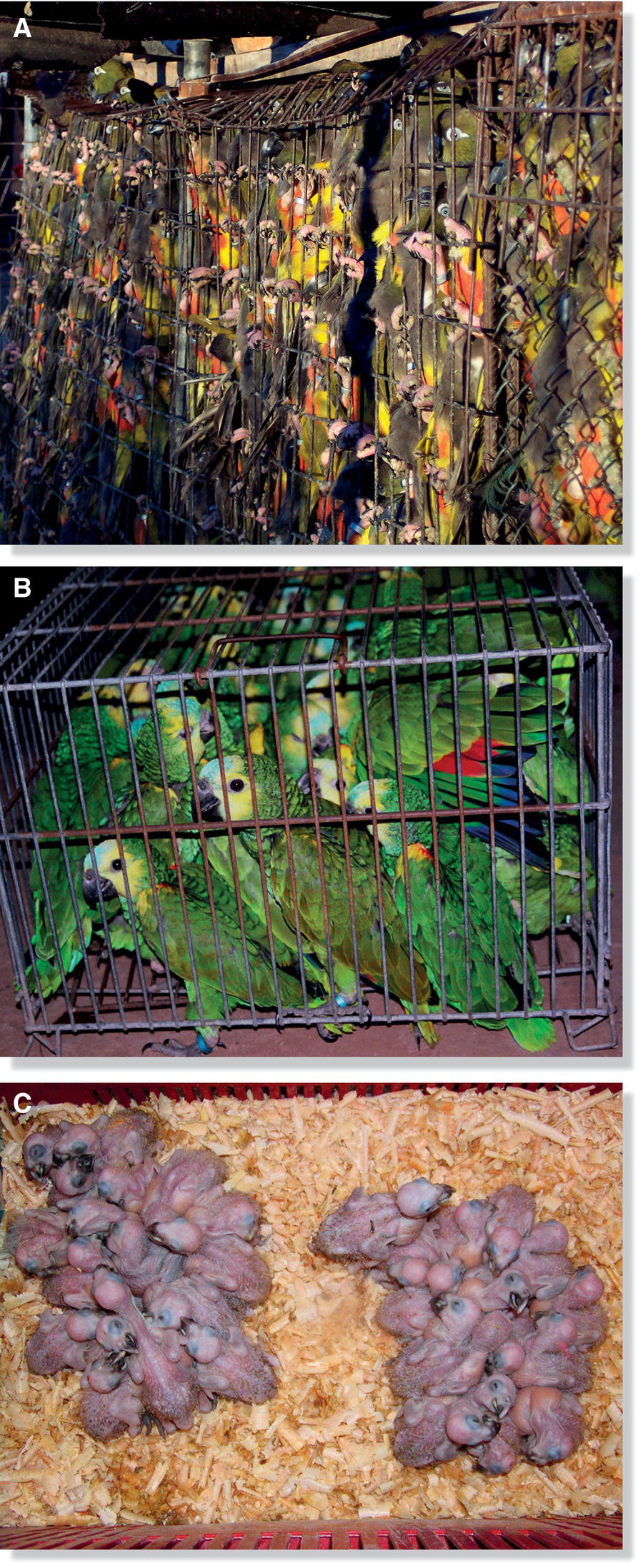

During the late twentieth century, global trade in exotic pets introduced a new element to the birth rate–death rate story. Many large tropical parrots became extremely rare in their native ranges because humans were stealing young parrots from their nests. This predation did not change the biological birth rate, because surviving adults continued to produce chicks, but it vastly reduced the effective birth rate, because most chicks were stolen from the wild and smuggled out to foreign countries. In the Lesser Antilles, for example, the illegal sale of Imperial Parrots (Amazona imperialis) (Fig. 15.25) reduced the effective birth rate to nearly zero in the mountaintop forests of Dominica. In 1979 the population of this spectacular parrot dropped further to about 50 individuals after a devastating hurricane. In the decades since, organized guarding of parrot nest sites and protection of mountaintop forests across Dominica has allowed offspring once again to recruit into the breeding population, effectively reversing the decline; as of 2008 the Imperial Parrot population had increased to about 350 individuals (Reillo and Durand 2008). Similar actions have greatly reduced the illegal parrot trade throughout the other islands of the Lesser Antilles.

Fig. 15.25 Imperial Parrot (Amazona imperialis). This species is found only on the island of Dominica in the West Indies. Populations were already in sharp decline from the illegal parrot trade when tropical storms killed many adults in 1979. This event galvanized efforts to more actively guard the species’ preferred nesting areas. Populations are now beginning to recover.

(Photograph by Mikko Pyhälä.)

The beautiful, somewhat nomadic Red Siskin (Spinus cucullatus) originally was common in open, semiarid areas of northern South America but has fallen to critically low numbers as a result of massive pressure from trappers for global trade (Fig. 15.26). This species has a pleasant song, and captive siskins will mate with domestic canaries to produce highly sought‐after rose‐colored hybrids. Tiny siskin populations persist in northern Venezuela, where it is among the country’s four bird species with the highest priority for conservation (Rodríguez et al. 2004). A recently discovered population in Guyana supplies additional hope, although it too is under pressure from illegal trapping (Robbins et al. 2003).

Fig. 15.26 Red Siskin (Spinus cucullatus). This species is prized in the pet trade because it will breed readily with domestic canaries. A common sight in the grasslands of Venezuela and Colombia during the early twentieth century, it now is endangered, as entire populations have been extirpated by illegal capture.

(Photograph by Siskini, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Cucullatamachocolombia.jpg.)

15.5.5 Chemical toxins and pollution

The publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring in 1962 alerted the world to the ecological dangers of chemical herbicides and insecticides, and her fears proved well‐founded when many raptor species began disappearing from long‐occupied habitats all over the world. Declines were especially pronounced for Bald Eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), Ospreys (Pandion haliaetus), and Peregrine Falcons (Falco peregrinus) in the USA and for Eurasian Sparrowhawks (Accipiter nisus) in Europe. The primary cause turned out to be reproductive failure from eggs being crushed in the nest. The resulting flurry of studies became some of the most famous in the history of conservation biology. By comparing the fragments of crushed eggs with egg specimens stored in museum collections (Chapter 13), scientists discovered that modern eggshells were up to 30% thinner than normal (Ratcliffe 1967; Hickey and Anderson 1968; Cade et al. 1988). The problem was traced to contamination of adult birds by chlorinated hydrocarbon pesticides, in particular the common organic pesticide DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) and its stable form DDE. At that time, DDT had become one of the most widely used pesticides in the world. Migratory birds of prey were eating birds, mammals, and fish that had been accumulating DDE in their tissue, thereby accumulating even higher concentrations of DDE than did species lower in the food chain. Physiological effects on raptors included higher death rates among adults, but the reduced birth rate from eggshell thinning was an even bigger problem. Populations of most northern hemisphere hawks and falcons plummeted in places where DDT use was widespread, but they began to recover almost immediately in places where DDT was banned.

Vast quantities of organic pesticides continue to be used around the world, and their long‐term effects on birth rates and death rates among birds remain poorly documented. The toxic insecticide monocrotophos is now banned in the USA, much of Europe, and Australia because of its impact on birds. Highly publicized deaths of nearly 6000 Swainson's Hawks (Buteo swainsoni) in Argentina during the late 1990s (Goldstein et al. 1999) brought global attention to its dangers, but monocrotophos remains widely used in many countries.

Vultures are especially susceptible to environmental toxins (Box 15.03). Many factors contributed to the steady decline of California Condors (Gymnogyps californianus) throughout the twentieth century, but the chief cause was lead poisoning. Virtually all condors found dead in the wild had numerous lead pellets in their crops, and the species is unusually sensitive to elevated levels of lead in its blood. In 1982 all 21 remaining wild condors were captured in order to protect the species from further exposure to environmental lead and to launch a captive‐breeding program. Today, lead poisoning continues to be the chief cause of illness and death among free‐flying condors, and experts agree that the species’ true recovery depends on elimination or substantial reduction of lead in the environment (Finkelstein et al. 2012).

The release of sulfur‐containing compounds into the atmosphere as a by‐product of coal‐fueled power plants and steel manufacturing causes a widespread form of environmental pollution. Acid rain is caused by the condensation of water droplets that incorporate atmospheric gases such as hydrogen sulfide in areas downwind of major industrial centers in North America and eastern Europe. The environmental effects of acid rain vary geographically, depending largely on the availability of chemical buffers in the soil such as calcium carbonate from dissolving limestone. In particular, in granitic landscapes that lack buffers, lakes and soils can become acidified, causing zooplankton and mollusks to become scarce. The ensuing ecological chain reaction often culminates in the loss of snail‐eating and fish‐eating birds such as loons, ducks, and raptors. Acid rain also is correlated with widespread deposition of methylmercury, an extremely toxic form of mercury produced by burning fossil fuels for power generation. The combination of food‐chain disruption and mercury accumulation is blamed for dramatic declines in the reproductive success of Common Loons (Gavia immer) in both North America and Europe (Burgess and Meyer 2008).

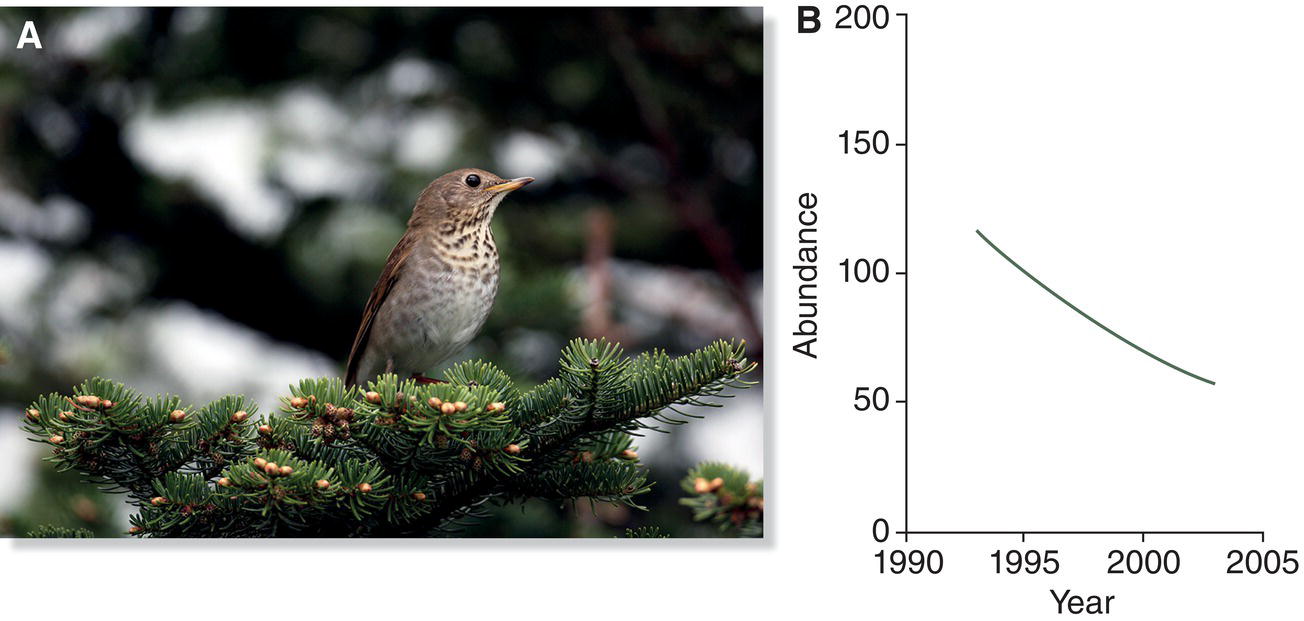

Declines in calcium uptake as a consequence of acid rain deposition have been linked to significantly impaired reproductive success among European songbirds, in part because they cannot obtain enough calcium to produce viable eggs (Graveland 1998). In the northern Appalachian Mountains of the USA, acid rain has caused a 10‐fold reduction in land snails, and Bicknell’s Thrush (Catharus bicknelli) numbers are declining within otherwise intact forest (Lambert et al. 2008) (Fig. 15.27).

Fig. 15.27 Population decline due to acid rain. (A) Bicknell’s Thrush (Catharus bicknelli) breeds exclusively in dense spruce‐fir thickets in northeastern USA and adjacent Canada. (B) Surveys of the species over the last few decades have revealed strong declines in abundance, particularly in the White Mountains of Vermont. Since their forest habitat remains largely intact, researchers believe these declines are due to acid rain.

(A, photograph by Gerard R. Dewaghe. B, from King et al. 2008. Reproduced with permission from Springer Science + Business Media.)

Since the late 1800s, environmental pollution from human sewage, manufacturing plants, oil refineries, coal‐powered energy plants, and agricultural fertilizers has changed the chemistry of the air, water, and soils throughout the industrialized and agricultural worlds. Pollution reduces prey diversity and alters vegetation structure in lakes, marshes, rivers, and streams, in turn reducing the reproductive success of aquatic birds such as ducks, grebes, bitterns, and loons. Some of the worst effects are caused by eutrophication, when excess nutrients in the water allow one or a few species of algae or cyanobacteria to explode and take over the entire system, reducing dissolved oxygen and choking out the native food web.

15.5.6 Introduced disease

By the time of Captain Cook’s arrival in the Hawaiian Islands in 1778, the resident Polynesians already had caused the extinction of numerous large bird species, but about 70 species of small native birds continued to occupy the forests from sea level to mountaintop. During the second half of the 1800s, a baffling wave of disappearances overtook Hawaiian songbirds, island by island. In 1902, ornithologist H. W. Henshaw described the phenomenon: “large areas of forest, which are yet scarcely touched by the axe save on the edges and except for a few trails, have become almost absolute solitude. One may spend hours in them and not hear the note of a single native bird. Yet a few years ago these areas were abundantly supplied with native birds.” Across the entire archipelago, dozens of bird species went extinct almost simultaneously, and throughout the twentieth century additional species steadily met the same fate.

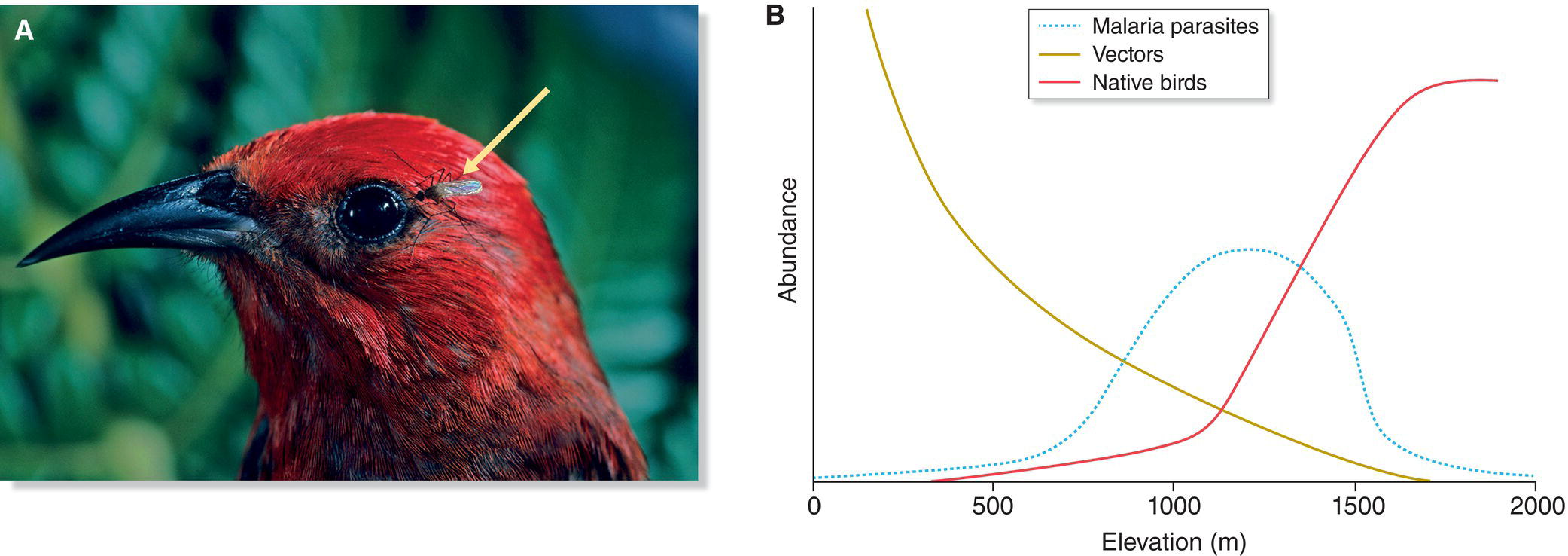

Many factors were responsible for these losses, but the introduction of disease‐bearing mosquitoes on Maui in 1826 certainly was the single‐most devastating event for Hawaii’s bird fauna since the original arrival of humans 1000 years earlier. Avian malaria and avian pox are the two most virulent agents. Both are carried and transmitted by a complex of mosquito species originally brought to Hawaii from Mexico in the water casks of merchant ships. These two diseases occur worldwide among continental birds, which have evolved resistance, and no doubt were carried annually to Hawaii by migratory birds for hundreds of thousands of years. Before the mosquito’s introduction, however, no vector existed to transfer these deadly pathogens from resistant migrants to naïve native birds. Consequently, no native Hawaiian bird had evolved resistance to malaria or pox (Fig. 15.28).

Fig. 15.28 Hawaiian birds and avian malaria. (A) Mosquito vectors (arrow), which transmit avian malaria to birds, are relatively recent introductions to Hawaii. Endemic Hawaiian birds like this Apapane (Himatione sanguinea) lack resistance to the disease. (B) Their highland habitat keeps birds isolated from the vectors that prefer warmer, lower elevations. Many lower‐elevation endemic birds of Hawaii have gone extinct because of avian malaria and compounding factors including habitat destruction, invasive species, and other diseases. Global warming puts all remaining species at risk as the mosquitoes that transmit malaria are able to move into higher elevations.

(A, photograph by Jack Jeffrey Photography. B, from van Riper et al. 1986. Reproduced with permission from the Ecological Society of America.)