Chapter 11

Breeding Biology of Birds

David W. Winkler

Cornell University

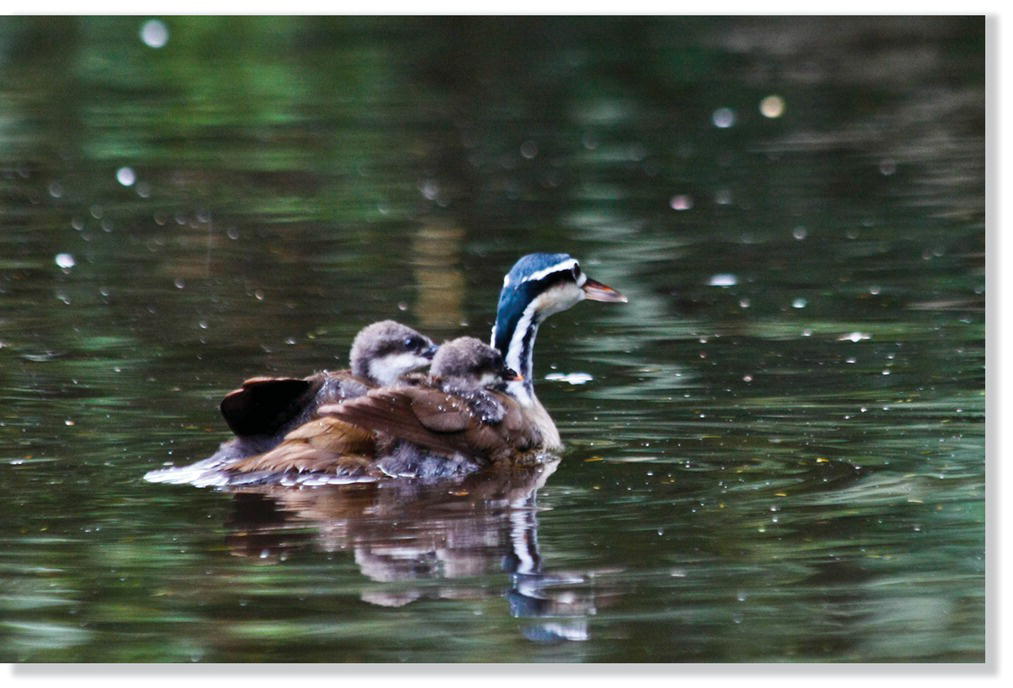

(Photograph by Wim Boon.)

Birds are adapted to breed in an amazing diversity of habitats, and avian breeding biology is correspondingly varied and complex. To appreciate some of this wonderful diversity in how birds reproduce, consider for a moment the lives of three kinds of birds from very different environments around the globe.

First, imagine that it is the middle of the winter just outside the French antarctic station in Terre Adélie. A group of male Emperor Penguins (Aptenodytes forsteri) stands huddled together in the freezing, howling wind. These birds will remain at this location for over 100 days, each incubating his single egg atop his feet within a thick insulated flap of flesh and feathers. The egg will hatch just as sunlight is returning in the antarctic spring, giving the new penguin chick most of the highly productive summer to grow, develop, and fledge before the sun disappears again.

Next, imagine yourself in a wet coastal forest as you watch a male Australian Brush‐Turkey (Alectura lathami) poking its bill into the top of a giant pile of dirt and leaves. This male is the builder, tender, and protector of this impressive mound. Inside, the process of decomposition generates heat to incubate the eggs that female brush‐turkeys have laid and buried within the mound. As soon as they hatch, these eggs will produce the most self‐reliant of young birds, chicks that will walk, or fly, off into the forest for a life on their own.

Finally, imagine that you are in a grove of fan palms on the bank of an African river, where you see an African Palm‐Swift (Cypsiurus parvus) returning to its unusual nest. The female palm‐swift has used her sticky saliva to glue a shallow shelf of plant fluff and feathers to the side of a down‐hanging palm leaf, and then she has similarly glued her eggs into this minimal nest. She and her mate take turns incubating these eggs by snuggling up next to them on the palm frond. As soon as they hatch, the chicks will grasp onto this precarious nest and remain there for weeks; meanwhile, their parents will return hundreds of times to provision the chicks as they grow mature enough to forage for flying insects on their own.

These are just three of the many ways that different birds have evolved to raise their offspring in different environments. We arguably know more about the breeding biology of birds than about any other single aspect of their lives, and this chapter outlines some of the generalities shared by all breeding birds along with some of the fascinating variation in the reproductive strategies of different avian groups.

11.1 Timing of breeding

Most birds breed within a limited window of time that depends on the seasonality of the local environment and on aspects of that bird species’ natural history such as its diet, predators, nest type, and habitat. Most birds in temperate regions must breed within the resource‐rich period in the spring that is driven by a seasonal flush in vegetation, the hatching of insects, and the oncoming summer warmth. Seasonal temperature fluctuations become less dramatic towards the equator, and in many tropical habitats it is seasonal variation in rainfall that drives annual cycles in resource availability. Therefore, timing of breeding is often less constrained for birds that breed in the tropics, where some species breed exclusively during a dry season, others find optimal conditions during the transition between dry and wet seasons, and a few are able to breed year‐round.

The timing of availability of food for their young is the factor that seems to have the greatest overall influence on when birds breed. Ideally, nestlings will hatch just when those food resources are most plentiful. Birds often must lay eggs while food supplies are still rising, especially in environments with strong seasonal changes in resource availability. Since many species—particularly passerines—feed primarily insects to their nestlings, these avian parents often lay eggs just before peak insect abundance. In the most extremely seasonal locations towards the earth’s poles, the breeding season of avian insectivores may last only a month or so due to the correspondingly brief period of insect abundance in arctic habitats.

Bird species that feed their chicks on food other than insects often breed at different times than insectivores in the same avian community. For example, American Goldfinches (Spinus tristis) of North America rely almost exclusively on thistle seeds to feed their young (Fig. 11.01), and this species therefore breeds in mid‐summer when thistle seeds ripen, rather than earlier in the spring. Elsewhere, many honeyeater species in Australia breed when and where they can find the abundant blossoms of key Eucalyptus tree species. Likewise, Eleonora’s Falcons (Falco eleonorae) in the eastern Mediterranean lay eggs in late summer, insuring that the peak food demands of their nestlings coincide with the parents’ prime hunting season during the fall landbird migration (Chapter 13).

Fig. 11.01 Breeding season and food availability. American Goldfinches (Spinus tristis) breed later in the summer than most insectivorous birds occupying the same habitat, as they rely on the ripening seeds of thistles and other plants to build their nests and feed their young.

(Photograph by Stan Tekiela, www.NatureSmart.com.)

The more regular the seasonal changes, the easier it is for a potentially breeding bird to predict them. In most environments, year‐to‐year fluctuations are minor enough that the breeding season falls within a predictable period within each year. Most birds’ reproductive systems are primed to be active only during these months. The avian internal clock relies on changes in day length, or photoperiod, which cue a cascade of physiological preparations for breeding (Chapter 7). Birds generally use photoperiod to establish their general breeding period, but often rely on other cues to fine‐tune the initiation of breeding. For example, in the wet forests of Panama, the presence of live insects helps stimulate male Spotted Antbirds (Hylophylax naevioides) into high breeding condition (Hau et al. 2000). The more closely an environmental cue relates to a critical environmental feature, the better it serves as the basis for reproductive scheduling. For example, many birds that nest in arid environments, such as the Red‐billed Quelea (Quelea quelea) of Africa (Chapter 12), are driven to breed after a heavy rainfall (Cheke et al. 2007). The same is true for many desert‐nesting birds, such as Zebra Finches (Taeniopygia guttata) of central Australia and several species of ground finches in the arid lowlands of the Galápagos Islands (Chapter 3). For all of these species, rainfall is a cue that predicts the future availability of seeds and insects related to plants that grow only when water is available.

A few non‐insectivorous birds have evolved to avoid regular breeding seasons altogether. Although they breed most commonly in the spring and summer, Rock Pigeons (Columba livia) of many cities worldwide can breed year'round on a diverse diet of seeds and city scraps. The crossbills of the northern hemisphere initiate reproduction based on the availability of their key resource—pine and spruce seeds. Because the seed production of these trees varies greatly from place to place and from year to year, crossbills may breed as soon as they find an adequate food supply (Hahn 1998), no matter what month of the calendar it happens to be. Birds like crossbills that remain ready to breed upon encountering favorable conditions must pay the costs of maintaining their reproductive systems throughout the year. In contrast, the majority of birds, particularly those in strongly seasonal environments, shut down their reproductive system during the non‐breeding season (Chapter 7).

11.2 Breeding territories

Nearly all birds defend some kind of territory during the breeding season (Chapter 13). Although expensive in terms of time, energy, and personal risk, the benefits of defending a territory often outweigh these costs. The size and richness of a territory’s resources frequently influence mate choice and subsequent breeding success. Males of many species therefore defend large, multipurpose territories to attract one or more females and supply enough food for chick rearing. For example, females of both marsh‐nesting warblers in Eurasia and blackbirds in North America may choose mates on the basis of a male’s territory size. Similarly, female Purple‐throated Caribs (Eulampis jugularis) of the Lesser Antilles prefer males with a higher availability of nectar on their territories. Males in this hummingbird species defend much more nectar than they need for their own use, reserving parts of their territories for females (Temeles and Kress 2010).

Territories also reduce the chance that other individuals of the same species will interfere with the territory owner’s breeding activities. This kind of breeding interference is a large problem for some species. For example, male bowerbirds of Australia and New Guinea craft elaborate structures to attract females, often by stealing rare bower materials from bowers made by neighboring males; if left unguarded by its male owner for just one day, a bower may disappear entirely (Pruett‐Jones and Pruett‐Jones 1994). Many birds may also attempt to destroy the eggs of nearby competitors. For example, in North America, both Marsh Wrens (Cistothorus palustris) and House Wrens (Troglodytes aedon) routinely puncture the eggs of conspecifics and other potential nest‐site competitors; Crimson Rosellas (Platycercus elegans) do the same in Australia (Krebs 1998). Breeding birds often mitigate the risk of this kind of disturbance by guarding their nests. For example, in northern South America, Green‐rumped Parrotlet (Forpus passerinus) pairs guard their eggs diligently. To test the rate of clutch destruction without parental defense, researchers set up experimental nest boxes filled with replicas of this species’ eggs. These false nests were undefended, and nearby Green‐rumped Parrotlet groups destroyed 40% of these clutches within 3 days. By comparison, invading parrotlets destroyed only 5% of clutches in real nests that were actively defended (Beissinger et al. 1998).

11.3 Nests and nest building

Only insects surpass birds in the diversity and sophistication of their nests. A tremendous amount of literature, mostly from the nineteenth century, describes the nest‐building behavior of birds. Yet across the entire spectrum of bird species—from common backyard birds to exotic species in far‐off lands—aspects of the nesting biology of most species have yet to be studied. In terms of construction and placement, each type of bird nest incurs its own costs (such as parental effort and risk of predation or sabotage) and benefits (including greater nest safety and thermoregulatory efficiency). To explore these various costs and benefits, it is necessary to appreciate the functions that nests serve and the diversity of ways these aims are achieved.

11.3.1 Functions of nests

Most birds construct nests primarily to hold and protect their eggs, and to keep them together so that a parent bird can incubate them at the proper temperature for development. A simple scrape in the ground can serve as an adequate nest for some birds. A few birds that lay only one egg at a time have forgone nests altogether and incubate their single egg in other ways. However, most birds build some kind of nest. Nests sometimes serve additional functions: a few birds roost in their nests even beyond the breeding season, whereas others construct nests as a type of display to attract mates. For some species, mutual nest building is a common component of pair formation and bonding (Chapter 9). Nevertheless, nearly all nests must primarily provide a safe haven from predators and the elements.

A successful nest usually thwarts predators via its concealment and/or inaccessibility. The nests of most bird species are therefore purposefully difficult to find. For example, the risk of nest predation is particularly high in many tropical forest habitats, and many tropical passerines accordingly construct notably small nests that are inconspicuous when not attended. Most birds construct nests with common materials, generally avoiding brightly colored substances. To further enhance camouflage, some species affix lichens or bits of bark to a nest’s exterior. The nests of some passerines include a long, trailing pendent, perhaps to break up the visual profile of the nest shape. Most bird species are also quite adept at constructing out'of‐reach nests. For example, birds in groups as diverse as vireos, broadbills, and herons often prefer to nest precariously on the tips of long, high branches—places that most climbing predators like rodents or snakes are unable to reach. Other birds commonly build nests in tree cavities, within cliff nooks, or high on the walls of buildings.

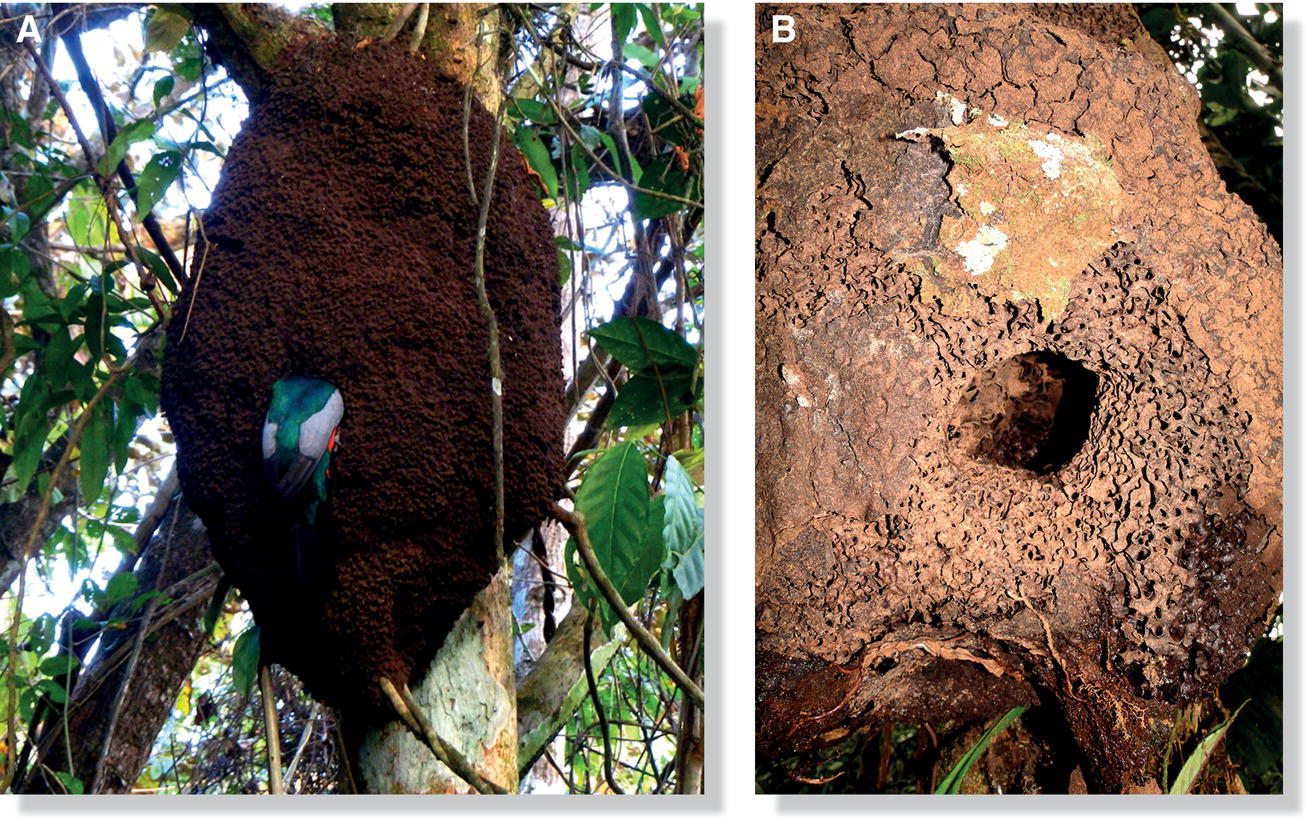

Among the most interesting nest locations are those constructed near animals that deter predators (Chapter 14). Many tropical birds lay their eggs within or very near the nests of aggressive wasps (Joyce 1993) or ants (Young et al. 1990), both of which will attack an approaching predator. In the neotropics, some species of trogons, kingfishers, and parrots dig nest tunnels within active termite or ant mounds (Fig. 11.02). How (or why) these nesting birds are spared the insects’ attacks remains a mystery.

Fig. 11.02 Cavity nesting within active wasp and termite nests. Some birds dig cavities within social insect nests, most likely a strategy to deter predators. (A) A Slaty‐tailed Trogon (Trogon massena) entering a nest hole within an arboreal termite nest. (B) The entrance of a Black‐tailed Trogon (Trogon melanurus) cavity that the birds have excavated within an active arboreal termite nest.

(Photographs by: A, Jenn Sinasac; B, Rebecca Brunner.)

Nests also provide shelter from the elements. The microclimate around and within many nests is much more favorable for eggs and nestlings than is the surrounding environment. For example, temperate‐nesting hummingbirds often choose nest sites under overhanging trees to minimize heat loss at night (Calder 1973). Some gulls place their nests in the shade to reduce the risk of their nestlings overheating or becoming dehydrated (Winnett‐Murray 1980). Similarly, in the desert, where vegetation is scarce and solar radiation intense, many birds build enclosed nests to provide shade for their eggs and themselves. Nests may also prevent eggs and young from rolling out. New World orioles and oropendolas, Old World weavers, and Asian broadbills all build deep, enclosed nests at the tips of long, thin branches. This combination of nest structure and site works in tandem: the structure keeps the eggs from falling out as the nest swings wildly in the wind, and the location prevents access by predators like monkeys.

11.3.2 Diversity of nest locations and nest‐site selection

Birds nest in almost every terrestrial and shallow‐water habitat on Earth—from the surfaces of lakes to rock niches above the timberline, from the howling, frozen barrens of Antarctica to forests and deep caves in the tropics. The sites that birds occupy within these habitats are similarly diverse. Featureless cliff faces, holes and cracks of every type, branches of all diameters, bare ground, and myriad human constructions (skyscrapers, bridges, telephone poles, signs, oil pumps, old boots and hats, and even active ferries)—nearly anything that can support a nest has been used by birds at some time.

Beyond protection from predators and the elements, birds often choose nest sites that are close to a food supply. Nesting sites generally correspond with the ecology of the parent. For example, Crab Plovers (Dromas ardeola) nest in burrows in the sand, not far from the sandy tidal flats on the Indian Ocean where this species prefers to feed; the treeswifts of Asia nest high on thin branches in the midst of their aerial habitat. However, there are many exceptions: both the Secretary‐birds (Sagittarius serpentarius) of Africa and the two long‐legged seriema species of the South American savanna nest atop small trees, despite spending most of their lives running and walking on the ground. Similarly, the Black‐and‐white Warbler (Mniotilta varia) of North America nests on the ground, despite being a specialized forager on the surfaces of tree trunks and branches.

Although some birds have very specific requirements for their nest sites, others show substantial flexibility. Ospreys (Pandion haliaetus) generally nest in treetops, but on islands free of predators they will nest on the ground if no trees are available. Many species with long breeding periods build nests in different sites as their breeding habitat changes across the season. For example, American Robins (Turdus migratorius) breeding in North America often place their first nests of the season low in protected evergreen trees, whereas robins breeding later usually choose higher sites in newly leaved deciduous trees (Sallabanks and James 1999). As the weather becomes progressively hotter in the Arabian Desert, Greater Hoopoe‐Larks (Alaemon alaudipes) similarly shift their nesting preferences from open areas to shadier, shrubby sites (Tieleman et al. 2008).

Increasing evidence suggests that birds pay a great deal of attention to the disturbance and predation risks associated with a given habitat. For example, Rufous‐bellied Thrushes (Turdus rufiventris) in Argentina build a greater proportion of their nests in protective bromeliads when nesting in sites disturbed by human traffic (Lomáscolo et al. 2010). Birds must balance the benefit of a well‐hidden spot with the risk that the same mode of concealment may obscure an approaching predator from view. Playback experiments have shown that when exposed to the recorded calls of larger nest predators, Siberian Jays (Perisoreus infaustus) in northern Sweden chose nest sites in denser vegetation than those chosen by control birds that were not exposed to such recordings (Eggers et al. 2006). Some host species respond similarly to the presence of brood parasites (Chapter 13) that might lay eggs in their nest. For example, in an experiment in Montana (USA), researchers played calls of brood‐parasitic Brown‐headed Cowbirds (Molothrus ater) during the territory establishment periods of their potential host species. The hosts responded by settling in lower densities, compared with other areas where the cowbird calls were not played. Non‐hosts, to whom the presence of cowbirds offered no threat, established territories of equivalent density in both the test and control areas (Forsman and Martin 2009).

Closely related and ecologically similar bird species often compete for nest sites at least as much as they compete for food. Competition for nest holes can be particularly intense in some habitats. Moreover, nest predators often develop a search image after finding multiple nests with similar attributes. Thus, within any given patch of habitat, competition persists both within and among bird species to build nests in less occupied locations.

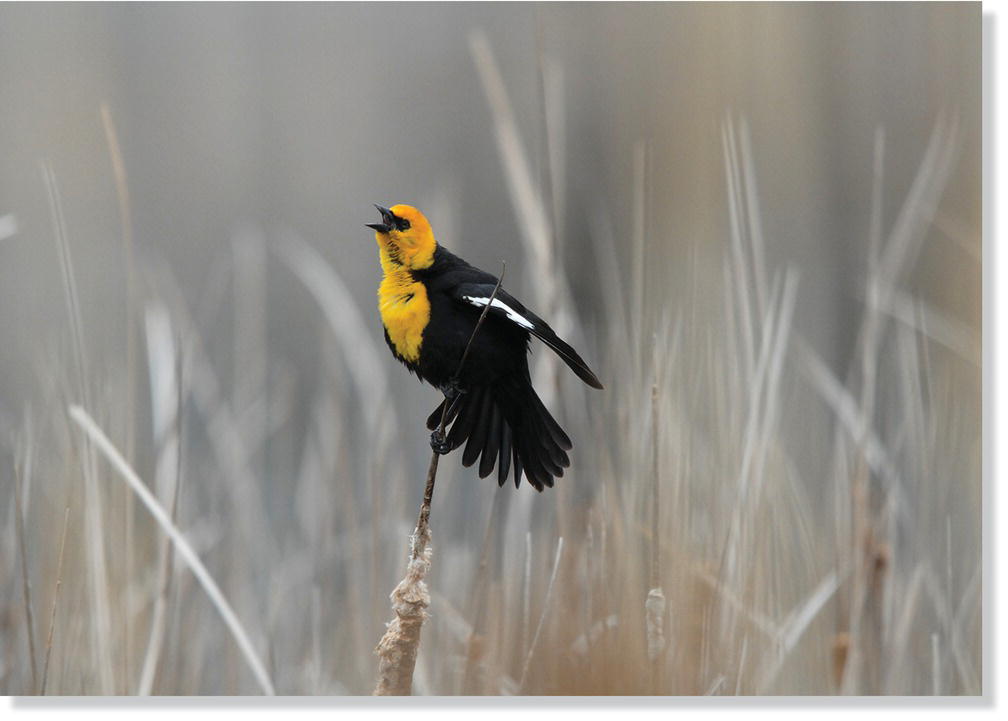

The males of some species display for a mate from a potential nest site, as do many weavers, herons, and wrens. Others display on a territory where the male has identified likely nest sites, as do marsh‐nesting blackbirds (Fig. 11.03). Species that exhibit these behaviors generally build nests that are demanding to construct or defend, or must nest within sites that are limited in space or resources. In other species, such as gulls, many passerines, and even some polyandrous birds such as jacanas, choosing a nest site appears to require a negotiation between the male and female; each considers sites identified by its mate. This early decision stage of the nesting cycle is hard to study because birds tend to be less committed towards the beginning of a breeding attempt, and slight disturbances caused by human observers may cause the pair to abandon a potential nest site. Therefore, ornithologists do not yet understand as much about this establishment stage of nesting as they do about later parts of the breeding cycle.

Fig. 11.03 Display on a breeding territory. Male birds like this Yellow‐headed Blackbird (Xanthocephalus xanthocephalus) attract mates by defending a high‐quality territory with many potential nest sites.

(Photograph by Herman H. Giethoorn.)

11.3.3 Diversity of nests

Nests vary wonderfully in composition and structure. They can be classified in many different ways; each nest type described below is classified primarily by its shape.

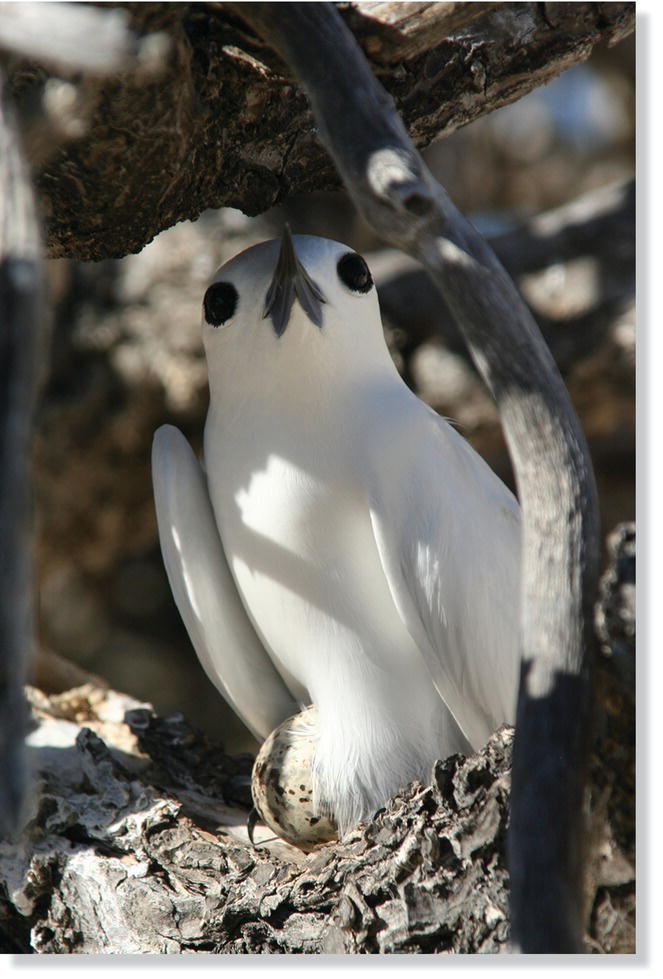

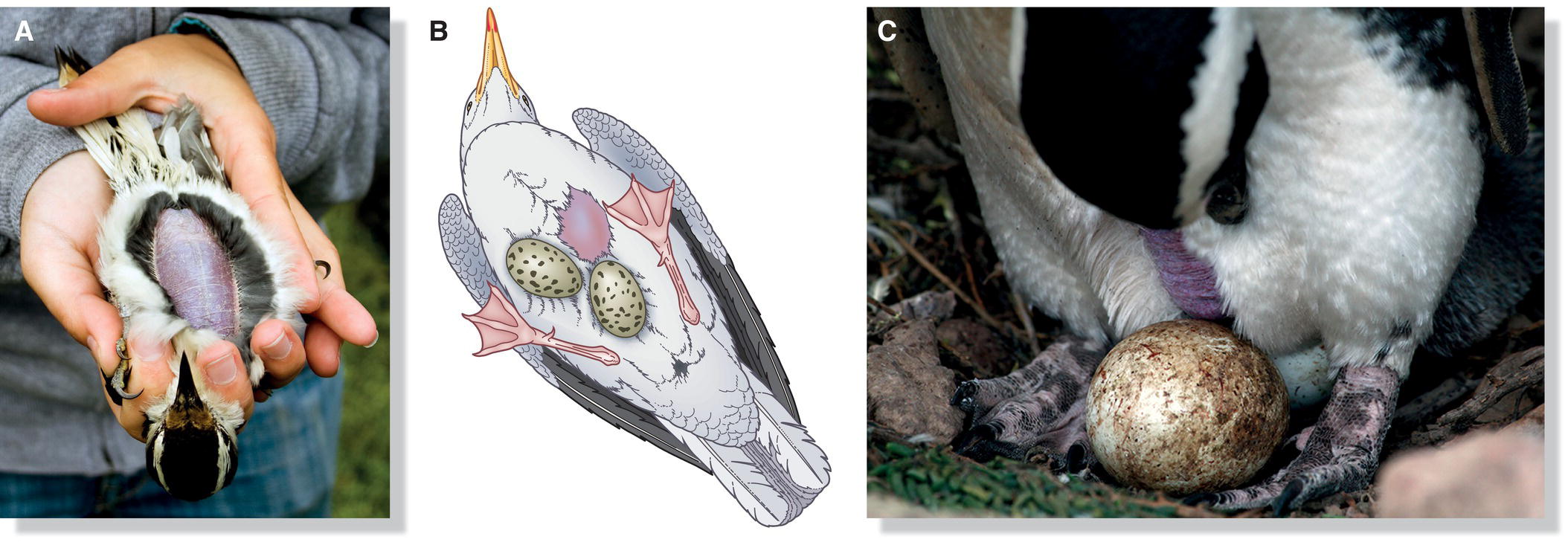

In a number of species, nesting involves site selection but no further nest construction whatsoever. Murres lay their single eggs directly on exposed rock ledges, and New World vultures and condors lay their eggs on the bare floors of shallow caves. White Terns (Gygis alba) of tropical seas lay a single egg on bare branches (Fig. 11.04), as do the potoos of the neotropics. The absence of a nest may be advantageous to these species for different reasons: parents need not waste time and effort nest building, exposed eggs may be less conspicuous to predators, and ectoparasites may be less of a problem when chicks are not restricted to the same soiled spot. Male Emperor Penguins (Aptenodytes forsteri) build no nest, and instead have evolved an incubation pouch that is formed by a loose bulge of skin above their feet; after a female lays her single egg for the season, she passes it to her mate for safe keeping while she leaves for a long period to feed in the distant ocean. All brood parasites also fall into the “nestless” category, as they lay their eggs in nests built by other birds.

Fig. 11.04 Some birds do not build nests. White Terns (Gygis alba) precariously lay a single egg on bare branches.

(Photograph by Duncan Wright, US Fish and Wildlife Service.)

The nests of some species consist of a simple scrape, in which birds displace loose gravel or sand on the ground to provide a slight depression for the eggs (Fig. 11.05). For example, many plovers, terns, and skimmers nest in a very shallow scrape, perhaps lined with a few flat pebbles or nothing at all. Some scrape‐nest species do not even create a depression at all if the substrate at their nesting site is too hard, but they may still arrange flat pebbles and twigs to create a very rudimentary nest.

Fig. 11.05 Scrape nest. Some species like this Ladder‐tailed Nightjar (Hydropsalis climacocerca) scrape an indentation in the substrate for their eggs. In these cases, the incubating adult generally blends in well with its surroundings. Here, the nightjar has just barely modified its nest site, placing this nest type at the boundary between a scrape nest and no nest at all.

(Photographs by Rebecca Brunner.)

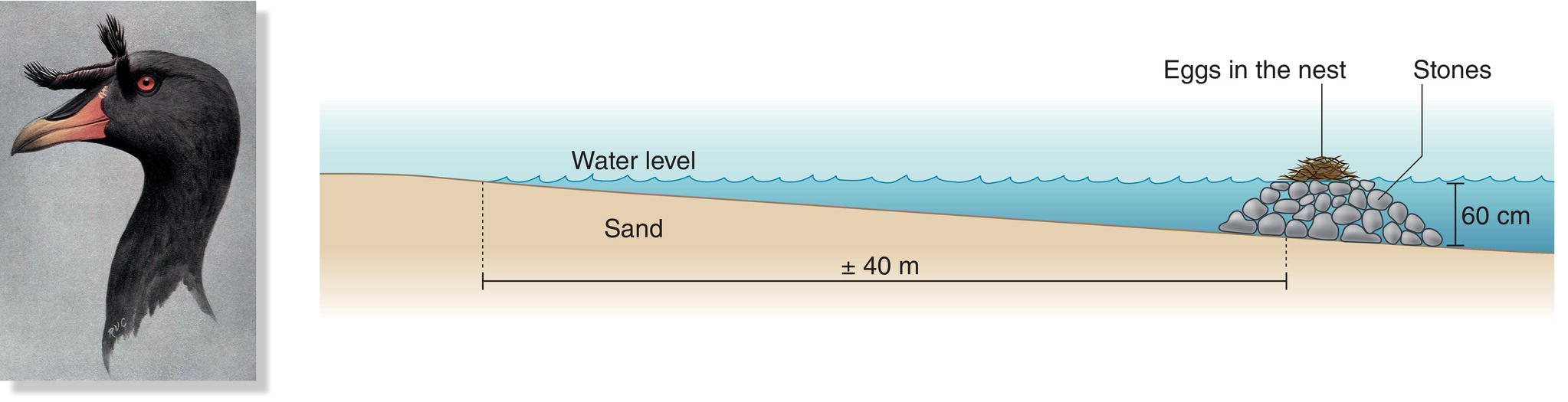

Platform nests consist of a mound with a very shallow depression on top. Different birds build platforms on the ground, floating in water, or within trees or shrubs. Platform nests vary tremendously in complexity, from the flimsy platforms of twigs thrown together by most doves (Fig. 11.06) to massive structures—sometimes containing thousands of large sticks—built by storks or large birds of prey like Ospreys (Pandion haliaetus) and eagles. Birds may build platform nests anywhere they find a strong enough support. Many herons, cormorants, storks, and raptors build platform nests in trees, but will use the same types of sticks to nest on the ground if no trees are available. Oilbirds (Steatornis caripensis) build platform nests inside South American caves (Box 11.01). Flamingos build short pedestals of mud, and grebes and some terns build floating rafts of aquatic vegetation to support their shallow nests (Fig. 11.07). The Horned Coot (Fulica cornuta) of South America builds an interesting variant of this type of platform nest: occupying high Andean lakes with limited aquatic vegetation, these birds pile stones in the water, building a shallow nest of vegetation upon the stones at the surface (Fig. 11.08). The accumulation of stones built up by several pairs over a few years can reach up to 1 meter high and 4 meters in diameter, weighing up to a metric ton (Ripley 1957).

Fig. 11.06 Platform nest. Most dove species, such as this Wompoo Fruit‐Dove (Ptilinopus magnificus), build flimsy platform nests made of sticks.

(Photograph by Deane Lewis, http://dl.id.au.)

Fig. 11.07 Vegetation raft nest. Grebes and other aquatic species, like this Black Tern (Chlidonias niger), construct floating rafts of vegetation to support their nests.

(Photograph by Jean Troalen.)

Fig. 11.08 Elevated nesting mounds. Horned Coots (Fulica cornuta) create nest mounds in shallow Andean lakes. These birds gather hundreds of stones until the top of their mound rises above the water surface; they then place debris and vegetation on top as a cushion for their eggs.

(Artwork by Robert V. Clem, from Ripley 1957.)

The majority of bird species build cup nests, structures with depressions on their top surfaces that are at least half as deep as they are wide. Birds place cup nests in a broad variety of sites: on the ground, in trees, beneath waterfalls, and within nest cavities of all kinds. Cup nests come in an equally diverse array of sizes and materials, although they are most commonly made of small twigs, dried grass, or mud. Crows and ravens build the largest cup nests; hummingbirds construct the smallest, often by securing lichens and soft fibers from seeds together with carefully collected spider webs (Fig. 11.09). As outlined below, ornithologists often categorize cup nests based on the nature of their support.

Fig. 11.09 Cup nest. Rufous Hummingbirds (Selasphorus rufus) gather spider webs, lichens, and “vegetable down” from seeds (A) to construct tiny, insulated cup nests (B).

(Photographs by: A, Penny L. Hall; B, David H. Wong, Vancouver, Canada.)

Simple, hard surfaces—the ground, a niche on a cliff, or, most commonly, tree branches—support “statant cups,” structures supported primarily from below. Oftentimes, gravity alone holds the nest in place. Bobolinks (Dolichonyx oryzivorus) of the New World build statant cups directly on the ground. Horned Larks (Eremophila alpestris) do the same in open country, with a slight twist: in order to keep their eggs slightly below ground surface to avoid foot traffic from large mammals, Horned Larks commonly build their statant cups within hollows of hardened cow or horse hoofprints. Most nests built in shrubs and trees are also statant cups, ranging from the loose piles of twigs and grass built by some songbirds to the heavy mud nests built by the Magpie‐larks (Grallina cyanoleuca), White‐winged Choughs (Corcorax melanorhamphos), and Apostlebirds (Struthidea cinerea) of Australia (Fig. 11.10).

Fig. 11.10 Statant cup nest. Constructed with mud, this Apostlebird (Struthidea cinerea) statant cup nest is supported by the tree branch from below.

(Photograph by Irby Lovette.)

“Pensile cups” hang by their rims, which are often securely attached to thin branch tips or reedy vegetation in marshes. New World blackbirds, vireos, and many other songbirds in Australia and Asia build pensile cups. The nest’s belly hangs unsupported, and the lack of sturdy structures surrounding pensile cups often minimizes predator access from below. Pensile nests with deeper centers are considered “pendulous cups.” Birds enter from the top of such nests, which are usually woven from plant strips or fibers. Pendulous cups are characteristic of New World orioles (Fig. 11.11), oropendolas, and caciques, as well as some Old World weaver species.

Fig. 11.11 Pendulous cup nests. The long, sock‐like nest of this Altamira Oriole (Icterus gularis) represents an extreme example of a pensile cup, supported only by its rim.

(Photograph by Greg Page.)

Usually made mainly of mud and/or saliva, “adherent cups” attach securely to vertical surfaces. Barn Swallows (Hirundo rustica), which breed throughout the northern hemisphere, build adherent cups by mixing mud with straw. Asian treeswifts use saliva to glue their tiny nests to the sides of branches (Fig. 11.12). The African Palm‐Swift (Cypsiurus parvus) even goes so far as to glue its eggs to a pad‐like vertical nest, incubating in a vertical position. White‐nest Swiftlets (Aerodramus fuciphagus) of Southeast Asia build perhaps the most extreme adherent cups, which often consist entirely of saliva. As their former common name “Edible‐nest Swiftlet” suggests, the nests of this species are the main ingredient in an Asian delicacy called “bird’s‐nest soup.” People have long harvested these nests in vast caves, climbing rickety skyscraper‐like scaffolds of bamboo to reach them. More recently, harvesters have instead constructed artificial caves for these birds—these structures resemble human houses, with the upper floor open to the air and the comings and goings of swiftlets. A swiftlet pair will often hurriedly build another nest if the first is removed, but these replacement nests usually contain bits of vegetation (as well as saliva) and are thus much less desirable as human food.

Fig. 11.12 Adherent cup nest. Grey‐rumped Treeswifts (Hemiprocne longipennis) and many other treeswift species use saliva to attach their minuscule nests, containing just one egg, to the sides of branches. After hatching, the nestling must balance in the nest or on the adjoining branch for several weeks.

(Photograph by Johnny Wee.)

Some bird species, especially those that nest on the ground amid vegetative cover, build domed nests. The woven dome, integrated with the woven cup, conceals the eggs or nestlings. In North America, meadowlarks build domed nests in grassy areas, and wood‐warblers called Ovenbirds (Seiurus aurocapilla) build them in forests (Fig. 11.13). In the Old World, many grass‐nesting species similarly build domed nests.

Fig. 11.13 Domed nest. The Ovenbird (Seiurus aurocapilla) is named for the domed shape of its nest, which resembles an old‐fashioned oven.

(Photographs by: left, Peter Caulfield; right, Scott R. Loss.)

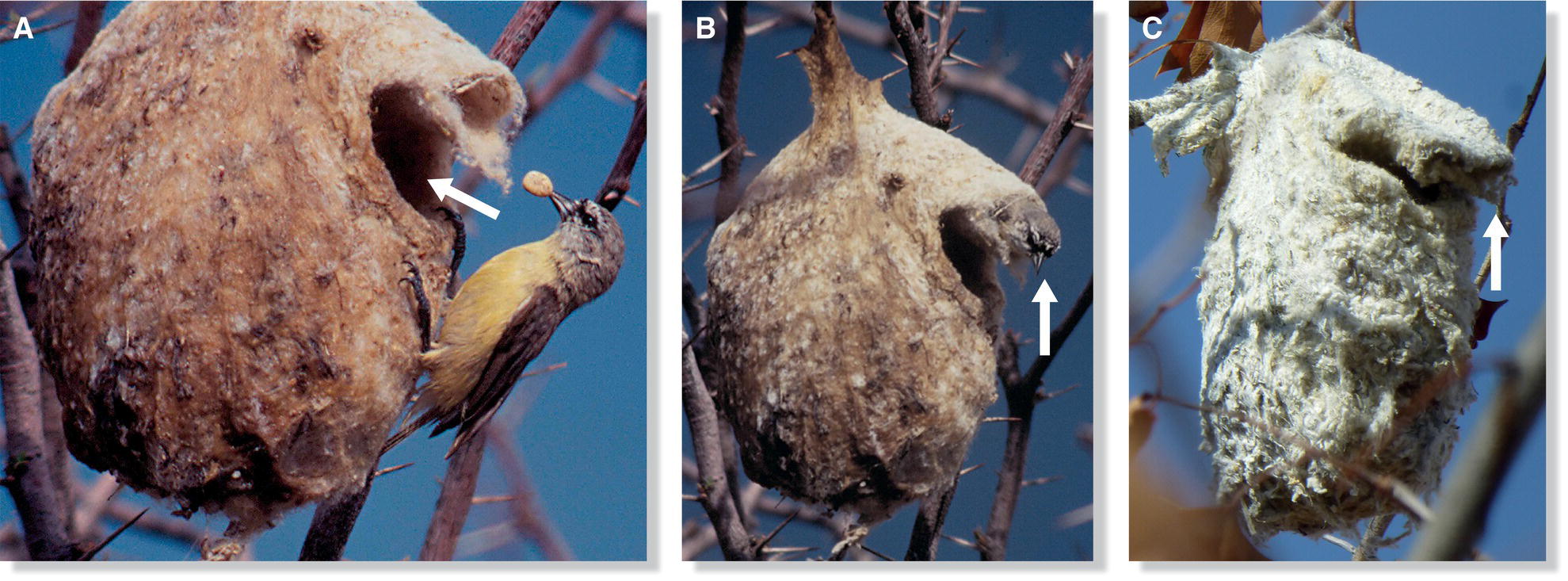

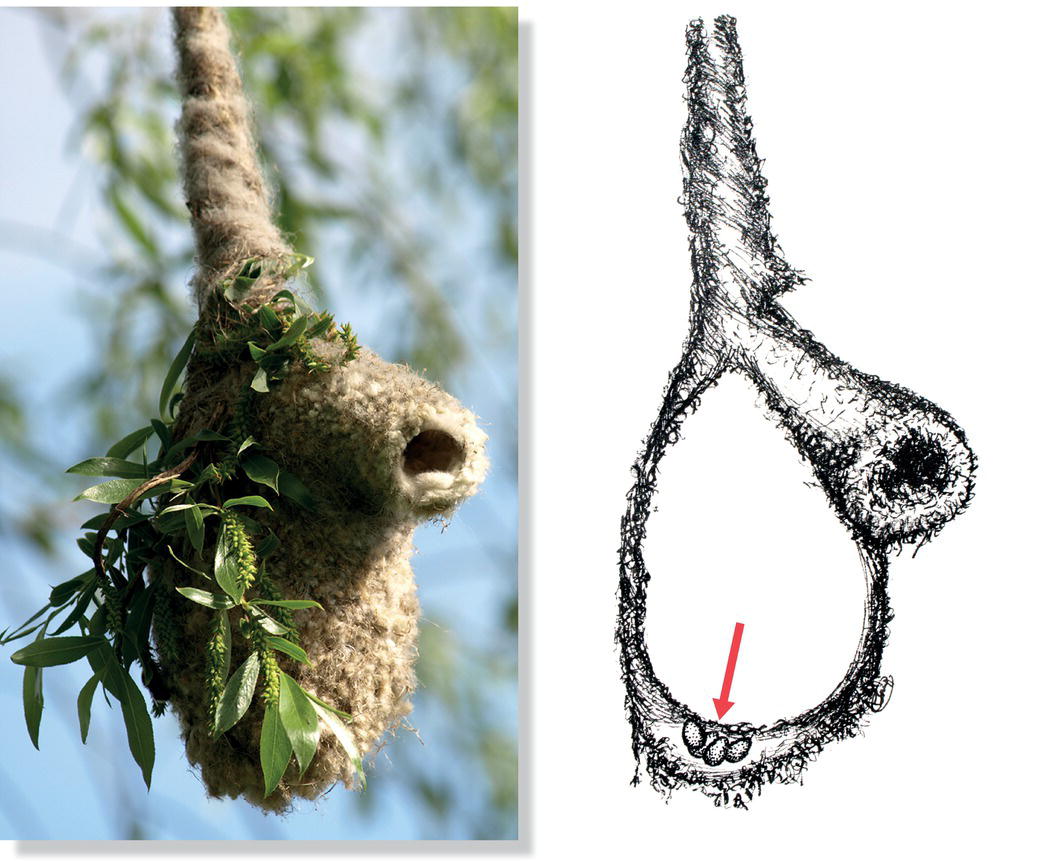

Globular nests are completely enclosed (with the exception of a small side entrance). Built in shrubs or trees, these nests are characteristic of most wrens. For example, Cactus Wrens (Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus) of North America build grassy spheres, often within the spiny arms of a cholla cactus. In the same desert habitats, Verdins (Auriparus flaviceps) build smaller globe nests with spiny twigs, orienting the spines to the outside for extra protection. Black‐billed (Pica hudsonia) and Eurasian (Pica pica) Magpies build larger globular nests of thorny twigs, sometimes inserting short strands of barbed wire. Broadbills in Asia and some New World flycatchers and South American ovenbirds deter predators by building their globular nests at the ends of long vines or tendrils. Southern Penduline‐Tits (Anthoscopus minutus) of Africa build pendent globular nests with a false entrance to foil predators. A prominent hole on the side of the nest is actually a fake entrance leading to a dead‐end chamber; the true entrance is a concealed slit in the roof of the false entrance that closes behind the parent as it enters and exits the real nest chamber (Fig. 11.14).

Fig. 11.14 Globular nest with false entrance. (A) Southern Penduline‐Tits (Anthoscopus minutus) build nests in which the larger, more obvious nest opening (arrow) is actually a false entrance. (B) The real nest chamber entrance is located above the false one (arrow). (C) When not occupied, the entrance tunnel lies flat, ending in a concealed slit (arrow).

(Photographs by: A and B, Mike Soroczynski; C, Peter LaBelle.)

A globular nest with an entrance tunnel is called a retort nest (Fig. 11.15). These nests are common among the mud‐nesting swallows, many African weavers, and some swifts. The lengths of these tunnels can vary from a few centimeters to more than a meter. Retort nests built with mud, especially those with very thick‐walled tunnels, can be very difficult for all predators except snakes to access.

Fig. 11.15 Retort nest. Birds like this Baya Weaver (Ploceus philippinus) build retort nests, which have a globular nest chamber with a distinct entrance tunnel.

(Photograph by Con Foley.)

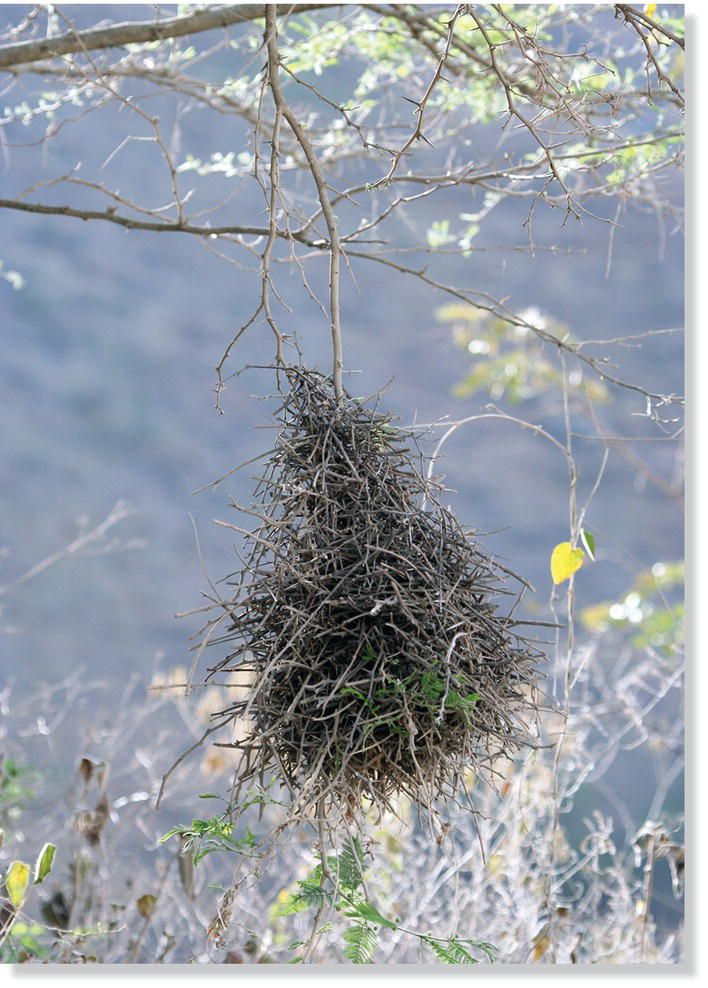

A few species build mound nests, which generally consist of large piles of nest material on the ground or in large trees. Megapodes—the most famous mound nesters—are the only birds that use the nest itself, rather than a parent’s body, as the source of heat for developing embryos (Box 11.02). Only a few passerine species build true mounds: Palmchats (Dulus dominicus) on the island of Hispaniola and several species of African social weavers build colonial mound nests—resembling large, suspended haystacks—in palms or trees. Monk Parakeets (Myiopsitta monachus) use sticks to build colonial mound nests in their native Patagonia. The odd, heron‐like Hamerkop (Scopus umbretta) of Africa builds an enormous nest mound more than 2 meters high and wide, usually in a large tree (Fig. 11.16). Hamerkop nests may contain up to 8000 sticks and weigh up to several hundred kilograms. The nest chamber lies in the center of the mound, connected to the outside by a mud‐lined tunnel.

Fig. 11.16 Mound nests. This Hamerkop (Scopus umbretta) mound nest is in the process of being built in a tree. When finished, these nests can span more than 2 meters. (Batra, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hammerkop_Nest_Kenya_2012.jpg. CC‐BY‐SA 3.0.)

A tree hole is likely the most familiar sort of cavity nest. All woodpeckers are capable of excavating their own nest cavities (Fig. 11.17), sometimes even in healthy tree trunks, thanks to a host of adaptations (Chapter 6). Although woodpeckers are adept at creating nest cavities in trees, many species of parrots, barbets, toucans, nuthatches, and tits are capable of modifying pre‐existing holes to suit their needs. As mentioned earlier, some trogons and other tropical birds dig nest cavities within arboreal termite nests.

Fig. 11.17 Cavity nest. Woodpeckers like this Red‐headed Woodpecker (Melanerpes erythrocephalus) are able to excavate their own nest cavities, sometimes even in healthy trees. Other cavity‐nesting species must find pre‐existing holes (sometimes drilled by a woodpecker in the past); competition over these valuable nesting cavities can be intense.

(Photograph by Stephen Patten.)

When cavities in the ground are longer than they are deep, they are generally termed burrow nests. Numerous species in many different avian families excavate burrows in sandy soil or moist sand. In contrast to the physical characteristics required to excavate in wood, soil excavators do not usually have specialized adaptations for this task. Examples from the temperate zone include the Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia) and the Common Kingfisher (Alcedo atthis); both loosen soil with their bills and clear a tunnel with their weak feet (Fig. 11.18).

Fig. 11.18 Burrow nest. This Common Kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) excavates its nest in a clay bank by loosening soil with its bill and clearing the resulting tunnel with its feet.

(Photograph by Andy Holt.)

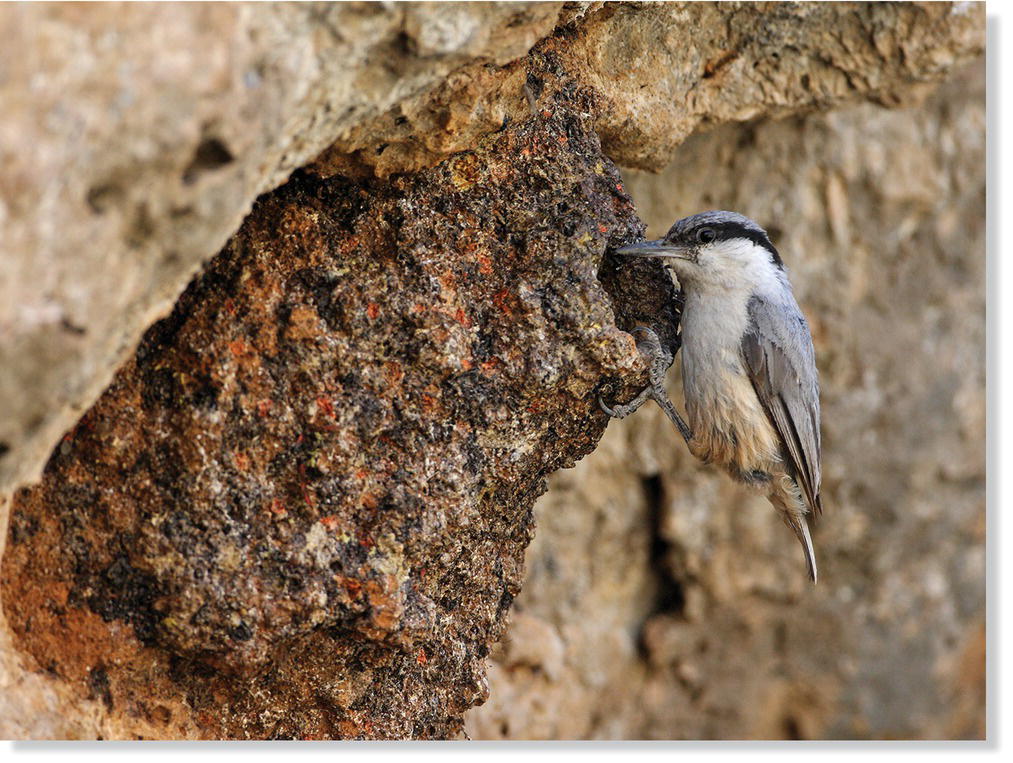

Cavity adopters occupy nest cavities created by other animals or through forces such as decay or erosion. Most cavity adopters throughout the world nest in naturally occurring tree holes or rock niches. Some birds that nest in adopted tree cavities rely on other species, usually woodpeckers, to create their holes (Chapter 13). Most artificial nest boxes placed out by humans are intended for cavity‐adopting species that typically nest in old woodpecker cavities. Australia has a particularly high proportion of cavity adopters even though no woodpeckers are found there; the Eucalyptus trees that dominate the Australian landscape develop natural cavities through fungal activity on scars resulting from dropped limbs. All nuthatches are cavity adopters, and many nuthatch species use mud to narrow the entrance to a hole in a tree branch or under a flap of tree bark. True to their name, Rock Nuthatches (Sitta neumayer), and the closely related Persian Nuthatch (Sitta tephronota), nest in rock face niches rather than trees. For added protection, these nuthatches construct a large mud nest within their rock cavity (Fig. 11.19). Many other birds also use mud to modify adopted cavities, and most design the entrance so that the parents may enter and exit with ease. In most hornbill species of Africa and Asia, females use mud and feces to seal themselves inside a nest cavity and remain there for months (Box 11.03). The male is solely responsible for supplying food to the female and their nestlings through a small slit in the mud wall of the cavity opening. In some hornbill species, mother and young emerge together; in others, the female emerges after the chicks are fairly well developed—in which case the nestlings seal themselves back in while both parents continue to feed them.

Fig. 11.19 Cavity adopters. Rock Nuthatches (Sitta neumayer) construct their nests in natural cliff crevices that they expand and enclose using clay and mud. Most other cavity adopters are less capable of modifying their nest sites, requiring fully formed cavities created by woodpeckers or natural weathering.

(Photograph by Amir Ben Dov, Israel.)

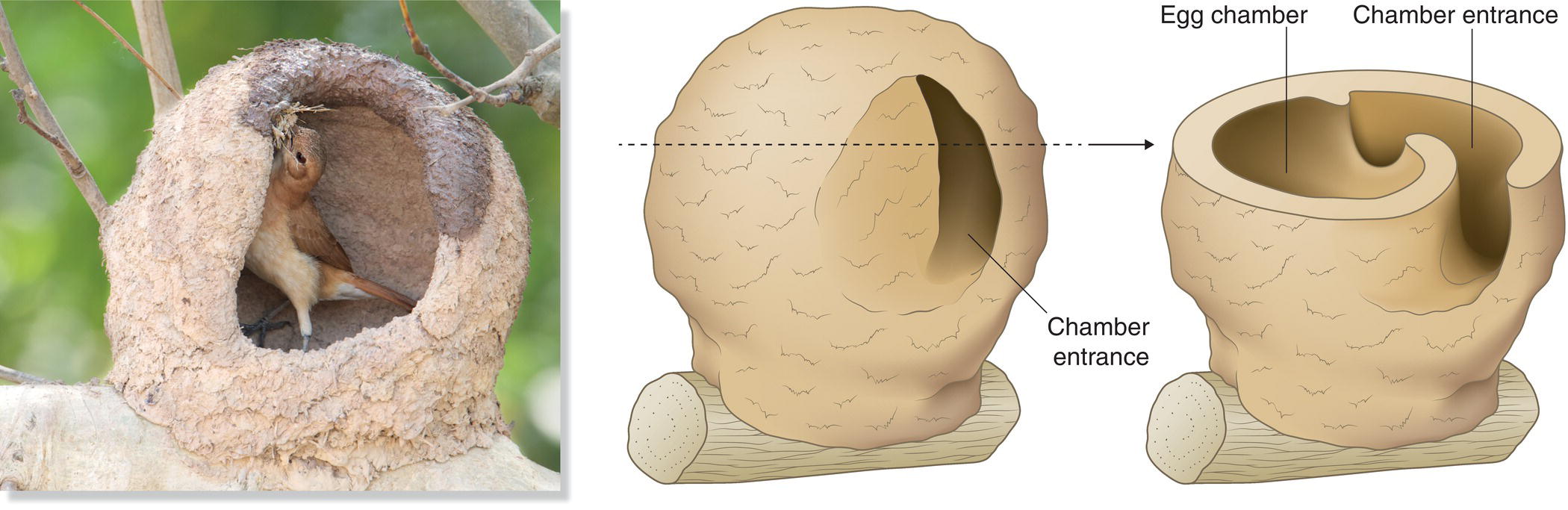

Some unusual birds build nests that do not fall cleanly within a single category of nest type. For example, the Rufous Hornero (Furnarius rufus) from South America builds a cup nest of grasses enclosed within a snail‐shaped sphere of hardened mud, complete with separate entrance and egg chambers (Fig. 11.20). In central Africa, Forest Swallows (Petrochelidon fuliginosa) build mud retorts within tree cavities. The Common House‐Martin (Delichon urbicum) of Eurasia builds the walls of its mud cup all the way up to an overhanging surface, incorporating the overhang as the top of its nest. The extremely small entrance presumably limits predator access.

Fig. 11.20 A Rufous Hornero (Furnarius rufus) nest under construction. This species builds a cup nest of grasses enclosed in a statant sphere of hardened mud, creating a separate entrance and egg chambers. These nests often harden to the consistently of cement; they generally last for many years and are sometimes occupied by cavity‐adopting species in subsequent years.

(Photograph by David W. Winkler. Illustration © Cornell Lab of Ornithology.)

11.3.4 Nest linings

Many, if not most, bird nests are lined with materials different than those used in constructing the outer structure. Birds use a great many kinds of materials to line their nests. A bowl of sticks is usually lined with softer materials, such as plant fibers, mammal hair, or dried grass. A tree cavity may have fur, bark strips, moss, or feathers covering the bottom. The likely primary function of most nest linings is to help insulate the nest and its living contents and prevent chicks from getting tangled in the coarser outer nest materials.

Many species line their nests with various combinations of natural materials. Most thrushes build a nest of twigs, grass, and leaves cemented together with mud and lined with soft, fine grasses. The Song Thrush (Turdus philomelos) of Eurasia forms the mud portion of its nest into a hard, smooth lining—sometimes using rotten wood, dung, or peat. Most of the wood‐warblers of the New World line their nests with fine dried grasses, but the Worm‐eating Warbler (Helmitheros vermivorum) of North America lines its nest with the spore capsule stalks of hair moss (Vitz et al. 2013). A surprising number of bird species worldwide line their nests with thin, hair‐like fungus fibers (Fig. 11.21): one survey found filaments of horse‐hair fungus (Marasmius) in the nests of 98 bird species, spanning 27 families throughout tropical and nearctic regions (Aubrecht et al. 2013). Some previous reports citing the use of “animal hair” in nests likely mistook horse‐hair fungus as real animal hair—an easy mistake, given how closely they resemble one another (McFarland and Rimmer 1996).

Fig. 11.21 Nest lining with fungus fibers. (A) Horse‐hair fungus is one of the most common nest lining materials worldwide. (B) For example, Bicknell’s Thrush (Catharus bicknelli) nests are often lined with filaments of this fungus.

(Photographs by K. P. McFarland, Vermont Center for Ecostudies.)

Many birds also use feathers to line their nests. Most female waterfowl line their nests with down plucked from their own breasts, while several songbird species line their nests with feathers that are not their own. The Long‐tailed Tits (Aegithalos caudatus) of Europe could be considered the champions of feather collecting, often lining their oval nests with between 1000 and 2000 feathers (Fig. 11.22).

Fig. 11.22 Feather nest lining. (A) This Long‐tailed Tit (Aegithalos caudatus) has collected the feather of another species to line its nest. (B) A nest of this species has been torn open by a predator, revealing the great number of feathers incorporated into its lining.

(Photographs by: A, R. Zap; B, Ros Wood, LRPS.)

A variety of species, ranging from raptors to starlings, line or adorn their nests with green plant material. Early biologists, failing to see a function for this “decoration,” wondered if these birds simply might be expressing an aesthetic sense. However, research on European Starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) suggests that the green plants used as nest lining contain chemicals that repel or kill avian ectoparasites (Wimburger 1984; Clark and Mason 1988). Subsequent research on Spotless Starlings (Sturnus unicolor) suggests that the compounds in these plants may affect the hormones of the attending female, and perhaps even the sex ratio of the offspring reared in the nest (Polo et al. 2010).

11.4 Nest‐building behaviors

Nest‐building behaviors vary based on the complexity of the nest structure, the availability of materials, and the number of birds involved in the construction of the nest. Clearly some nest types involve more investment and skill to construct than do others. For example, scrape nesters probably spend much more time locating a suitable site than in forming the simple nest depression itself.

When building platform nests, most birds lay a foundation of coarse sticks across branches or another supporting substrate, then add additional sticks until the bulk of the platform is built, and finish with finer sticks and a lining, if any. Building a cup nest often requires more specialized techniques. As in platform construction, birds often start with coarse material for the nest foundation, adding finer materials as they work upward and inward toward the cup. To pack and solidify the nest, the building bird may sit and turn in the center, thrusting its legs and pressing its breast against the surrounding materials. Once the cup is coherent and strong, the bird will often add lining—either by packing it down via continued breast lunges, body rotations, and belly quivers, or by using its bill to weave the lining into existing materials. The aptly named Common Tailorbird (Orthotomus sutorius) of Southeast Asia adds an extra step at the beginning of this process by sewing a funnel‐shaped cradle, and then building its soft cup nest inside, under its cover: first, it pierces a series of small holes near the edges of two large, living leaves. Then, it inserts plant fibers, cobwebs, or cocoon silk through the holes and draws the leaves together (Fig. 11.23).

Fig. 11.23 The stitchwork nest of the Common Tailorbird (Orthotomus sutorius). This bird builds a cup nest within a “cradle” of one or more large leaves, which it sews together using pliable grasses, cobwebs, or silk. In the left photo, note how the bird stitches through the leaf, much as a person using a sewing needle would stitch through a piece of cloth.

(Photographs by: left, Anton Croos, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nest_of_tailorbird.jpg. CC‐BY‐SA 3.0; right, Adityamadhav83, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:(Orthotomus_sutorius)_Common_Tailorbird_nests_at_Madhurawada_04.JPG. CC‐BY‐SA 3.0.)

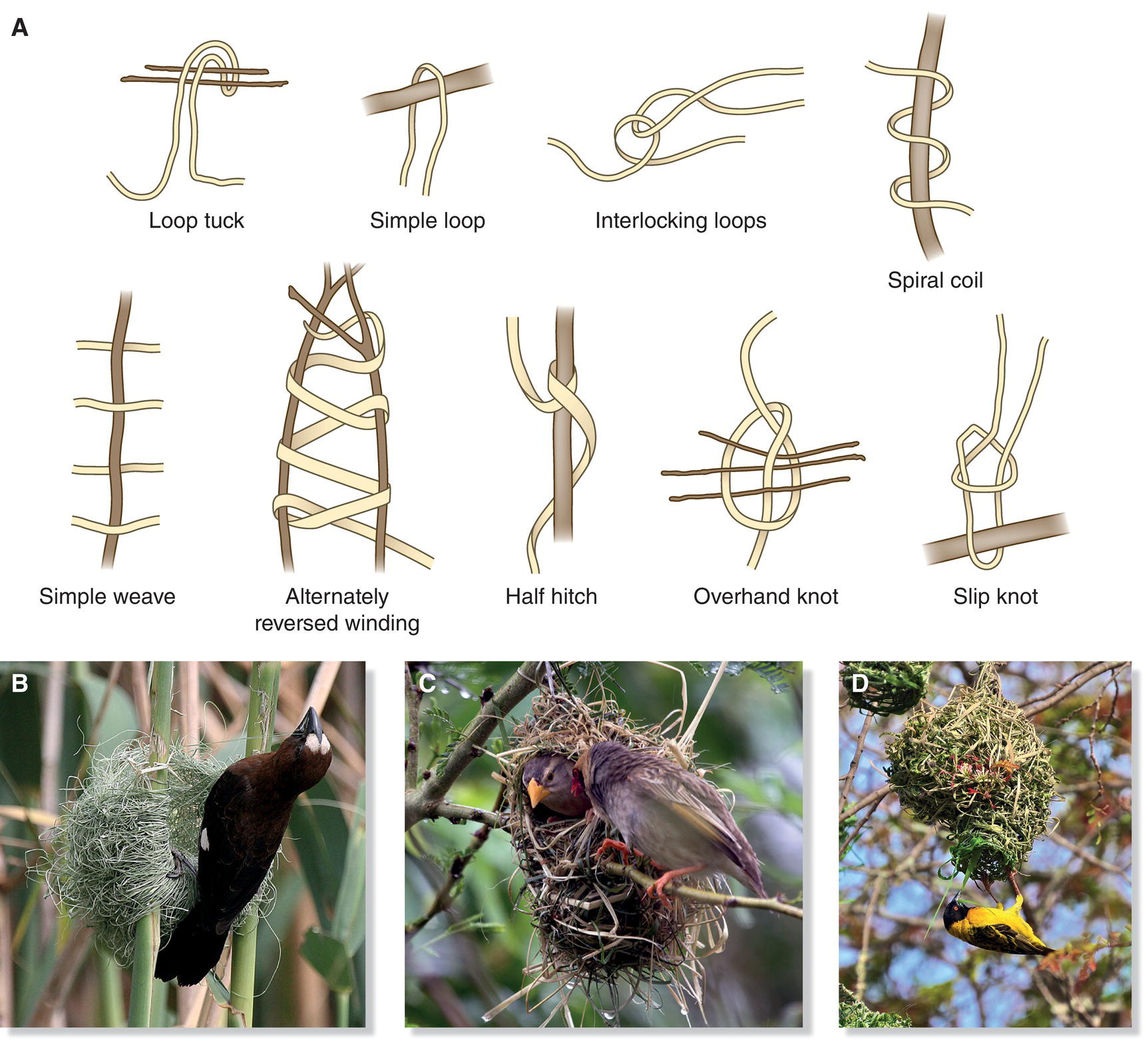

Pendulous cup nesters exhibit even more intricate building behaviors. With incredible dexterity, these avian weavers often hold onto structural material with their feet, using their bills to weave strands together and form knots. These expert builders flit their heads back and forth, over and under, meticulously positioning supple fibers—usually freshly gathered grass or other green and pliant plant fibers—into a pendent formation. As the fibers dry, the nest walls solidify with considerable integrity and tensile strength. The globular and retort nests of African weavers are created using perhaps the most impressive and elaborate of all avian weaving techniques. These birds use a variety of knots in their constructions, producing nests of remarkable durability and unrivaled intricacy (Fig. 11.24). The orioles and oropendolas of the western hemisphere—quite distant relatives of the African weavers—use most of the same knots (Heath and Hansell 2002).

Fig. 11.24 Avian weaving techniques. (A) African weavers employ a variety of patterns and knots during nest construction. (B) The Grosbeak Weaver (Amblyospiza albifrons) constructs its nest with simple loops and tucks. (C) Red‐billed Queleas (Quelea quelea) use spiral coils in their crudely woven nests. (D) The Village Weaver (Ploceus cucullatus) uses more sophisticated stitches, including alternately reversed winding, simple weaves, and half hitches. Overhand and slip knots are even more complex.

(A, from Collias and Collias 1964. Courtesy of Karen Collias Whilden. Photographs by: B, Robert Lewis; C, Susan Knodle; D, Alexander Yates.)

Mud‐nesting birds also employ a great variety of construction methods. The most common technique involves dipping dried vegetation into mud before applying it to the inner nest layers. Many species incorporate mud in this way. Certain swallow species represent the only birds that build adherent nests solely of pure mud (Fig. 11.25). Selecting the right consistency of mud to meet the extraordinary engineering demands of these nests must require considerable discernment.

Fig. 11.25 Mud nests. Cliff Swallows (Petrochelidon pyrrhonota) transport mouthfuls of mud to build and attach their nests to walls and cliffs. Most other mud‐nesting birds use a combination of mud and vegetation.

(Photographs by: left, Cameron Rognan; right, Mike's Birds, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cliff_Swallow_building_a_nest_(4737045414).jpg. CC‐BY‐SA 2.0.)

11.4.1 Sex roles in nest building

Males and females play various roles in nest construction, depending on the species. However, responsibilities tend to be fairly consistent within certain groups. For example, in hummingbirds and most other lekking avian groups in which there is strong sexual selection on males (Chapters 3 and 9), the female builds the nest entirely on her own. The opposite is true for polyandrous species, such as phalaropes and jacanas, in which the male builds the nest. In many sexually dimorphic species with brighter males, the female often assumes responsibility for most of the nest construction, perhaps because her duller colors help avoid detection of the nest location by predators. When the male and female are similar in appearance, they often each take a nearly equal share in nest building—as in many gulls, corvids, and herons. In these species, the male may gather most of the material while the female builds the nest. In other birds, males take the lead in nest building and the female then adds the lining when the nest is finished.

Many male wrens, and some raptors and weavers, construct surplus nests on their territories. Although the function of these extra nests is open to debate, they may allow rapid re‐nesting if a first nest is lost to predators or competitors. Extra nests may also help attract females: a study of Eurasian Wrens (Troglodytes troglodytes) in the UK showed that the more nests a male had on his territory, the more likely he was to obtain multiple mates—a few such males with multiple nests attracted as many as five females (Evans and Burn 1996). In other species, females evaluate males based on the craftsmanship of their nests. Red‐billed Queleas (Quelea quelea) establish nests and pairs at about the same time, forming enormous colonies very rapidly. To attract a mate, a male builds the first half of a nest and displays from it; if a female deems the half‐nest worthy, the pair builds the rest together.

11.4.2 Duration of nest building

The amount of time required for nest building depends on the type of nest (more elaborate nests take longer), the stage of the breeding season (construction often takes less time as the season progresses), and the weather (rain and snow often cause delays). A songbird in a temperate zone typically spends about 6 days building its simple cup nest—3 days on the outer layer and 3 days on the lining. With shorter breeding seasons, temperate birds must generally build faster than their counterparts in the tropics. For example, a tiny antwren in Panama may spend 10–15 days to build a comparable cup nest. Great Kiskadees (Pitangus sulphuratus), a type of neotropical flycatcher, build bulky, domed nests over several weeks; Chestnut‐headed Oropendolas (Psarocolius wagleri) require about a month to construct their long, pendulous nests. While building a nest, birds also forage, familiarize themselves with their territory and/or mate, and interact with neighbors. Hamerkop (Scopus umbretta) pairs can build their enormous nests in as little as 20–25 days, but they typically spend only a few hours intensively nest building on each of those days (Wilson and Wilson 1986).

11.4.3 Nest appropriation and reuse

Most birds construct a new nest every year, especially if a previous nest supported young all the way through to fledging. After a single use, constructed nests often become flattened and misshapen. Used nests may also be littered with feces, uneaten food, the debris of nestling feather sheaths, and perhaps even the carcass of a chick that did not survive to fledging. These components produce odors that might attract nest predators; used nests also support a wealth of bacteria and invertebrates, some helpful and others harmful. Even most woodpeckers, whose cavities take much effort to excavate, usually create new nests every year. However, starting from scratch each year is not a universal rule; for example, raptors and other large birds with exposed nests may reuse them for generations, and many seabirds will return to the same rock ledge or burrow for their entire lifetimes.

Reusing old nests must provide an advantage for some birds, because many species appropriate the used nests of other species. For example, small gulls and some sandpipers that nest in northern boreal forests appropriate the old nests of landbirds in small spruce trees. Great Horned Owls (Bubo virginianus) of North and South America often adopt large nests of other species such as hawks, crows, or even squirrels. The large, thorny nests of South American thornbirds (Fig. 11.26) are known to be re‐used by at least 11 other bird species (Lindell 1996). Sometimes an old nest is simply used as a physical support for a new nest: in North and Central America, Mourning Doves (Zenaida macroura) may place their flimsy stick nests on almost any elevated support, including the old nests of robins, grackles, or thrashers. The Little Swift (Apus affinis) of Africa adopts old mud retorts originally constructed by swallows, often affixing white feather “decorations” around the entrance.

Fig. 11.26 The well‐defended nest of the Chestnut‐backed Thornbird (Phacellodomus dorsalis). Thornbirds build large globular nests out of sticks; later, these nests are often reused by other species.

(Photograph by Fabrice Schmitt.)

11.5 Eggs

Birds are the only major vertebrate group without at least one live‐bearing species: fish, amphibians, reptiles, and mammals each include at least a few live‐bearing species. Exactly why no live‐bearing birds have evolved remains a bit of a mystery, but one compelling idea is that bearing live young would weigh down the female bird throughout gestation, and thereby either hinder her flight ability or limit her brood size. However, the fact that female bats successfully bear live young while flying competently through their entire pregnancy presents an argument against this hypothesis. Laying external eggs also allows both avian parents to at least potentially aid in their care, as well as the opportunity to abandon the eggs if conditions or circumstances are adverse—thus providing a chance for the parents to survive and rear broods in the future.

All avian eggs have the primary function of protecting the embryo inside as it develops. Yet the eggs of various bird species differ extensively in size and shape, shell coloration and structure, and the relative proportions of albumen and yolk. From the smooth white of some domestic chicken (Gallus gallus) eggs to the granulated, avocado‐like capsule of the Emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae), bird eggs present a dazzling array of diversity. The study of egg diversity is a specialized branch of ornithology termed oölogy (Chapter 13).

11.5.1 Egg structure

The eggs of fish and most amphibians can survive only in water, tying these animals to an existence dependent upon aquatic environments. Bird eggs, in contrast, are able to retain their aqueous contents and develop on dry land across a great range of environmental conditions. Ancestral archosaurs (Chapter 2) first evolved a hard‐shelled egg with internal membranes. Because their eggs contained the watery medium required by embryos to develop, these animals no longer needed to live in or near water; thus began the long evolution of one large branch of land animals, including birds.

Bird eggs are large, especially when compared with shell‐less human eggs, which are about the size of the period at the end of this sentence. The only mammals with eggs at all similar to birds are the monotremes—the four species of echidnas (spiny anteaters) and the Platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus)—that lay soft, leathery eggs instead of giving birth to live young. Embryos contained within the large external eggs of birds, reptiles, and monotremes must be entirely resource‐independent during early development—unlike all other mammals, whose mothers internally provide sustenance to the embryo. Thus, a bird egg must be packed with all of the protein, carbohydrates, fats, and water that the embryo will need until it hatches.

One way to understand the structure of an egg is to follow it through the developmental process (Chapter 6). Initially, the ovum is pushed out of its surrounding follicle cells in the ovary, and it is generally fertilized by a sperm as it begins its journey across the infundibulum into the oviduct. As the egg moves down through the oviduct, it passes through a succession of glandular cells that secrete successive layers of albumen and shell membranes; the shell is added last, very near the terminus of the oviduct. Because not one of these added layers involves the addition of new cells with their own nuclei, the egg of an Ostrich (Struthio camelus)—with its single nucleus protected by layers of non‐cellular material—is one of the largest living cells we can observe today.

To acquaint yourself with the major features of an egg, envision or explore a chicken egg from your kitchen (Fig. 11.27). As you crack a chicken egg, notice how a thin membrane holds the brittle mineral shell together, adhering to its inner surface, somewhat akin to the layers of auto safety glass. This membrane sticks tightly to the shell. Another membrane surrounds the albumen, or egg white; this layer can be frustrating to peel off a hard‐boiled egg. Once you have broken through these two outer membranes, you are able to spill the contents of the egg into a bowl; you can see the yolk surrounded by the white, now released from its membrane. Although difficult to see, the yolk itself is surrounded and held together by the vitelline membrane; this membrane is what you rupture if you “break” a yolk. You may notice that the yolk rotates so that a circular, white spot on its surface is upward in the dish. This tissue, termed the blastoderm, would develop into the embryo if the egg were fertilized. If you ever have tried to separate a yolk from the white of a broken egg, you have encountered the gelatinous, stringy parts of the albumen that often are twisted and milky white in color. Hard to separate from the yolk, these tissues are the chalazae. Before the egg was cracked open, the chalazae were connected to the inner face of the shell at the distant ends of the egg, thus suspending the yolk in the center of the albumen, protecting it and holding it in place within the egg.

Fig. 11.27 Basic egg anatomy. This cross‐section schematic shows some of the major internal components of an avian egg.

(Illustration by Andrew Leach © Cornell Lab of Ornithology.)

Now we will consider the structure and function of each component in greater detail, beginning with the yolk. The yolk contains all of the lipids (fats) and most of the protein needed to nourish the developing embryo until it hatches. The relative sizes of the yolk and white vary among groups of birds: yolks tend to make up a larger proportion of the total egg mass in species with precocial chicks, which are very well developed at hatching (such as waterfowl, shorebirds, and pheasants), compared to species with altricial young (such as passerines) in which the yolks are smaller. This difference arises from the fact that precocial chicks usually develop in the egg for a longer period of time and therefore require more sustenance, and thus a larger yolk.

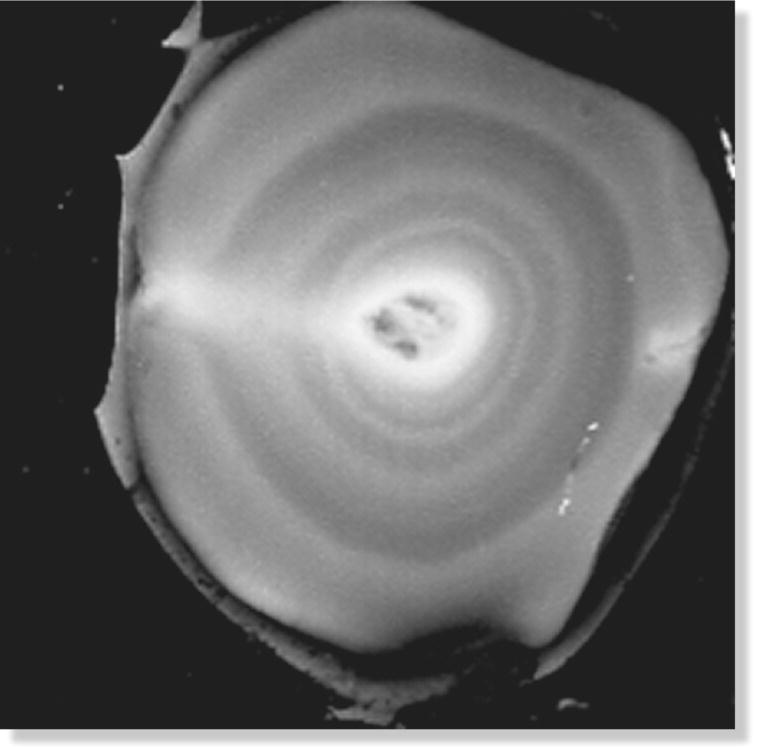

The yolk is the first part of the egg produced by the laying female. Before the yolk passes down the oviduct for the addition of albumen and shell, it undergoes rapid growth over a period of about 5 days to 2 weeks. However, many birds—especially songbirds—usually lay one egg per day (and never more). Because yolk preparation requires more than a day, females often prepare yolks in enough ova for a complete clutch before laying their first egg. During this preparation period—sometimes called the “yolking up” stage—the yolk is deposited within the vitelline membrane in alternating bands of darker and lighter yolk, producing a structure that resembles growth rings in a tree when viewed under special laboratory conditions (Fig. 11.28). Because these bands alternate on a daily cycle (dark bands are deposited during the day, when the female ingests food rich in pigments), the yolk ring structure reveals how long each female needs to prepare its yolks for laying. The only structure that interrupts these concentric rings is a cylinder of light‐colored yolk that stretches from the yolk’s core to its surface, where the germinal spot sits. The embryo will develop here, beginning as the flattened disk‐like blastoderm. Since the germinal spot and its column are lighter than the rest of the yolk, the developing embryo always floats to the top, no matter which way the egg is turned.

Fig. 11.28 Yolk rings. Over the course of several days, the yolk is deposited within the vitelline membrane in alternating bands of darker and lighter color. In this cross‐section image through a yolk, the paler band cutting across the rings terminates at the germinal spot on the yolk surface, where the embryo will eventually develop.

(Photograph by David W. Winkler.)

The yolk would float up against the shell if the chalazae did not suspend it at the center of the egg. The albumen, which varies in viscosity depending on the proportion of water and protein within it, consists of a series of layers around the yolk. A very thin layer of viscous albumen surrounds the yolk and extends into the chalazae, followed by a thin layer of watery albumen, a thick layer of more viscous and variably fibrous albumen (the largest component), and finally a thin layer of watery albumen right beneath the shell. In addition to providing nearly all of the water and much of the protein for the developing embryo, these layers of albumen serve admirably to protect the embryo from physical damage, provided the shell is not broken.

The shell is the developing embryo’s outer line of defense (Fig. 11.29). Avian eggshells are much thicker and stronger than the shells of other egg‐laying vertebrates. However, this increased thickness renders gas exchange across the shell more difficult. The growth and respiration of a developing embryo require oxygen and produce carbon dioxide. The egg cannot contain all of the oxygen needed to fuel the embryo’s metabolism, nor can it hold all of the carbon dioxide and wastewater produced by the embryo before it hatches. Therefore, the developing embryo must be able to “breathe” through pores in its shell. An egg loses, on average, 18% of its mass between laying and hatching (Rahn and Ar 1974), mostly from water loss across the shell.

Fig. 11.29 Eggshell composition. This micrograph of an eggshell, paired with an enlarged schematic, shows the location of pores and the internal shell membrane.

(Micrograph courtesy of University of Colorado Museum of Natural History Paleontology Eggshell Collection UCM # HEC 563‐C; illustration by Shaena Montanari.)

The eggshell’s porosity also can put the embryo at risk. Pollutants such as oil can enter the egg and poison the embryo or coat the egg’s surface, cutting off gas exchange. Over 90% of Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) embryos died when their eggshells were exposed to only one‐tenth of a drop of crude oil (Hoffman 1978).

If you were to open a fertile chicken egg at an advanced stage of embryonic development, the entire inner surface of the shell would be covered with a membrane engorged with blood vessels that facilitate gas exchange. This chorioallantoic membrane (Fig. 11.30) is formed by the fusion of two embryonic sacs, the chorion and the allantois, which are both connected to the core inner organs of the developing embryo—very much analogous to a human embryo’s connection to its mother’s placenta via the umbilical cord. The chorion is the outer membrane that surrounds the entire avian embryo; it is evolutionarily homologous to the membrane of the same name in mammals, which forms much of the mammalian placenta. The allantois holds any metabolic waste that cannot evaporate through the shell, such as uric acid crystals. As a fusion of these membranes, the chorioallantoic membrane serves as the functional equivalent of the embryo’s lungs throughout its development within the egg.

Fig. 11.30 Membrane anatomy changes as the embryo develops. Infused with blood capillaries, the chorioallantoic membrane is connected to the inner organs of this chicken (Gallus gallus) embryo. The air space at the top of the egg gradually expands as water content decreases via consumption by the embryo and evaporation through the permeable shell.

(Illustration by Andrew Leach © Cornell Lab of Ornithology, adapted from Murray et al. 2013.)

The chorioallantoic membrane covers more and more of the shell’s inner surface as the embryo develops. In a newly laid egg, the membrane enclosing the albumen adheres directly to the membrane just below the shell—except at the blunt end of the egg, where a small air space occurs. This is the same air space you may encounter while peeling a fresh hardboiled egg. As the water within the egg evaporates through the shell or is consumed by the developing embryo, this air space between the two membranes gradually expands (Fig. 11.30). The buoyancy imparted by this growing air space is valuable to field ornithologists who need to check the developmental progress of an egg: the extent to which the egg floats or sinks when placed in water often indicates how much longer the embryo must develop before hatching.

11.5.2 Egg size

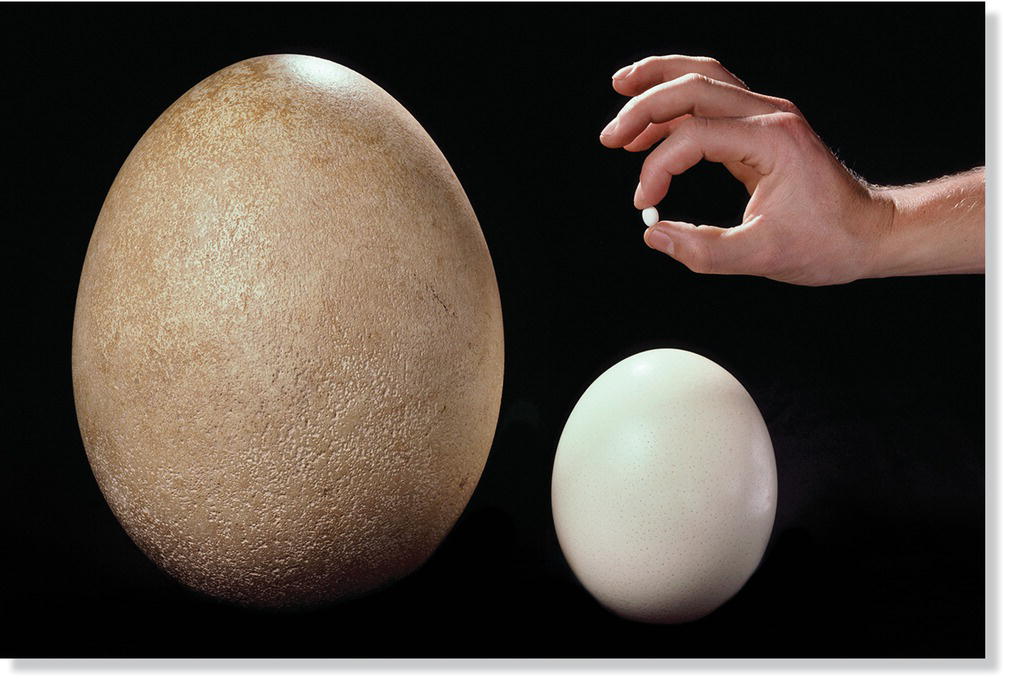

The egg of the Ostrich (Struthio camelus)—measuring roughly 18 by 14 centimeters and weighing about 1.4 kilograms—is the largest of any living bird. However, Ostrich eggs seem small compared with those of the extinct Elephant Bird (Aepyornis maximus) that roamed Madagascar until only a few hundred years ago—its eggs measured up to 37 by 24 centimeters and weighed as much as 12 kilograms. By way of comparison, at least 150 domestic chicken (Gallus gallus) eggs could have fit inside one Elephant Bird egg. The eggs of the smallest bird in the world, the Bee Hummingbird (Mellisuga helenae) of the West Indies, are only 10–13 millimeters in length and weigh less than 1 gram; approximately 75 of these hummingbird eggs could fit inside one large chicken egg (Fig. 11.31).

Fig. 11.31 Egg size extremes. The largest egg shown here is from the recently extinct Elephant Bird (Aepyornis maximus). To its right is an Ostrich (Struthio camelus) egg, the largest of all bird species living today. The tiny white egg is from the smallest of living birds, the Bee Hummingbird (Mellisuga helenae).

(© Frans Lanting, www.lanting.com.)

As a general rule, larger birds tend to lay larger eggs. However, when comparing egg size with adult body size, the eggs of larger species are proportionally quite small: an Ostrich egg is only 1.7% of the weight of an adult female Ostrich, whereas a wren’s egg is 13% of the female’s weight. The kiwis of New Zealand lay the largest eggs by relative size, with single eggs that are 25% of the female’s body weight. Not surprisingly, female kiwis generally only lay one egg per season, although on very rare occasions they may lay up to three. Conversely, some brood parasites—the Common Cuckoo (Cuculus canorus) of Eurasia, for example—lay very small eggs relative to their body size. This may be advantageous for multiple reasons: smaller eggs may more closely resemble those of their hosts; it may increase the likelihood that the parasitic chick hatches first, since larger eggs usually take longer to develop; and it may enable brood parasites to lay more eggs per season, increasing the likelihood that some of their young will hatch and survive.

Egg size also varies among birds in other ways. In general, birds that lay large clutches generally produce small eggs relative to their body size. During their first nesting attempts, females of many species lay eggs that are smaller than those of more experienced breeders. The eggs of precocial birds tend to be larger than altricial ones, even when the adults are similar in size. For example, adult cranes and eagles weigh about the same, but the eggs of cranes, which have precocial young, are about 4% of the adult female’s body weight, whereas the altricial eggs of eagles are about 2.8% of the adult’s weight.

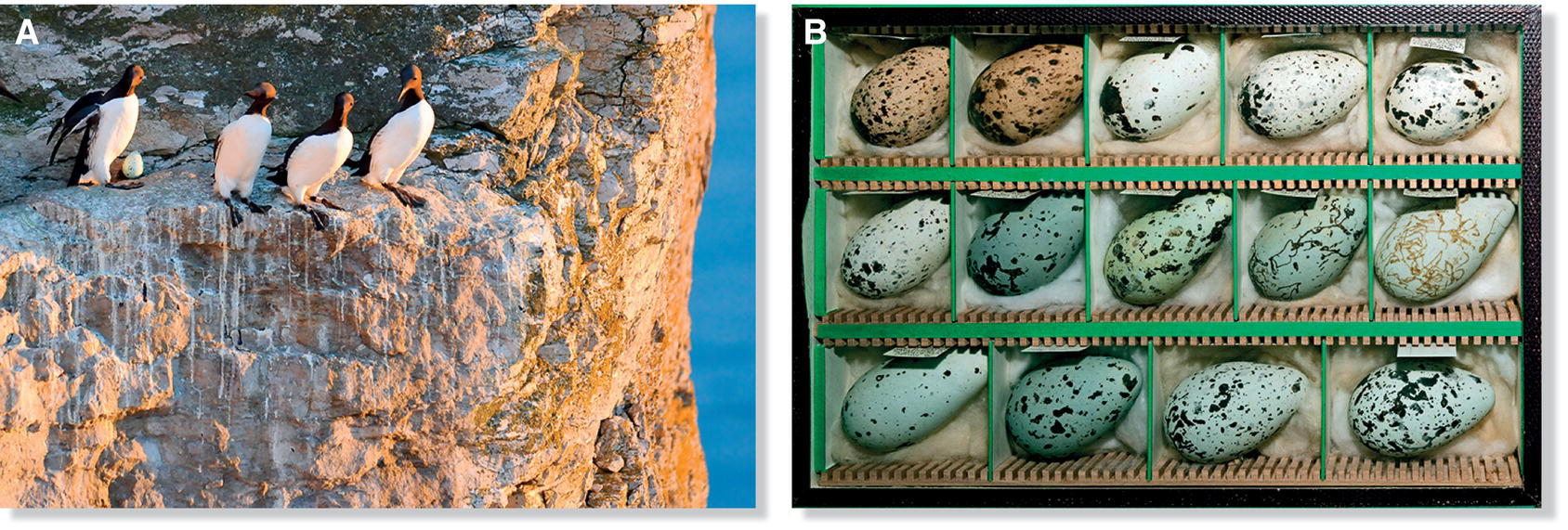

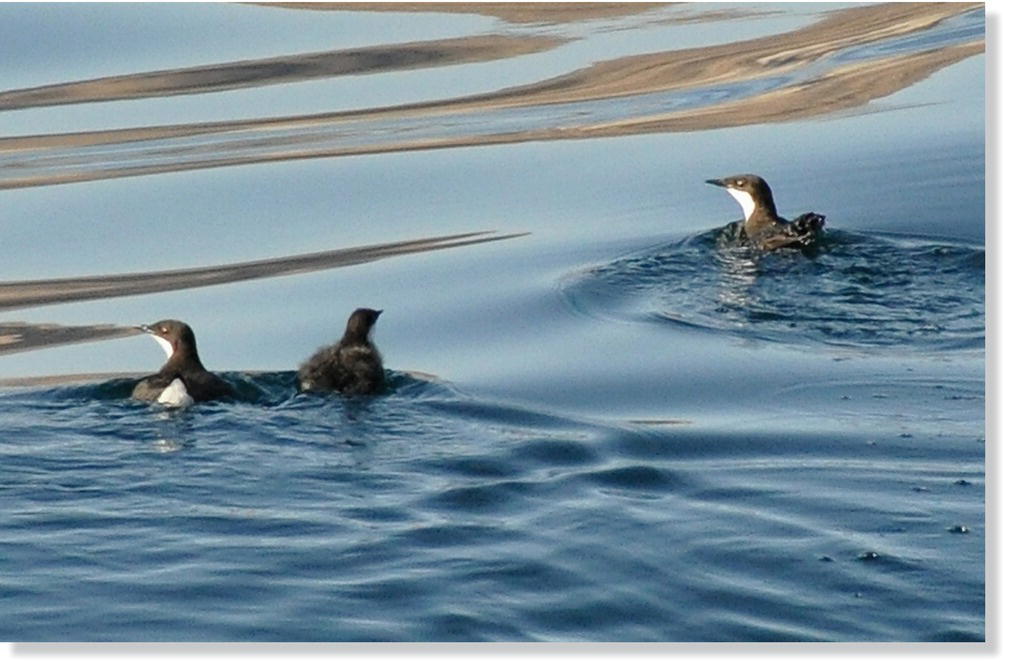

11.5.3 Egg shape

Although bird eggs are usually approximately oval, their shapes vary from long and pyriform (pear‐shaped) in some species to nearly spherical in others. The diameter and muscular tension of the oviduct during eggshell formation determine the egg’s shape. Oviducal dimensions and contractions have presumably evolved to match egg shape with the environmental needs of each species. Owls often lay near‐spherical eggs, which may allow efficient packing within their often deep nest cavities. Murres place their single eggs directly on narrow, often slanting, ledges high above the sea. Their eggs are long, with an almost straight side; one end is remarkably pointed, the other forms an obtuse arc. This strange shape ensures that the eggs always roll in a tight circle—a distinct advantage for eggs vulnerable to rolling off perilous ledges (Fig. 11.32). All shorebird eggs also have a pointed shape, even for species nesting in flatlands where the eggs are not in danger of rolling away. This pointed shape may increase incubation efficiency: shorebirds usually lay four eggs, which fit symmetrically and compactly when the pointed ends align toward the center of the clutch. If the eggs become disheveled, the parent shorebird points them all inward again before resuming incubation. Considering that shorebirds lay large eggs in proportion to their body size, and that many nest in cold environments, efficient heat transfer from parent to eggs may be particularly important for these birds.

Fig. 11.32 Eggs of cliff‐nesting murres. (A) Common Murres (Uria aalge) nest close together on precarious cliff ledges and lay eggs that are sharply tapered, a shape that serves as a safeguard against rolling off narrow ledges. (B) Murre eggs are also remarkably variable in color and pattern, which may be an adaptation that helps parent murres recognize their own eggs in a tightly packed nesting environment.

(Photographs by: A, David Thyberg, Shutterstock.com; B, Didier Descouens, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Uria_aalge_MHNT_Box_Rouzic.jpg. CC‐BY‐SA 4.0.)

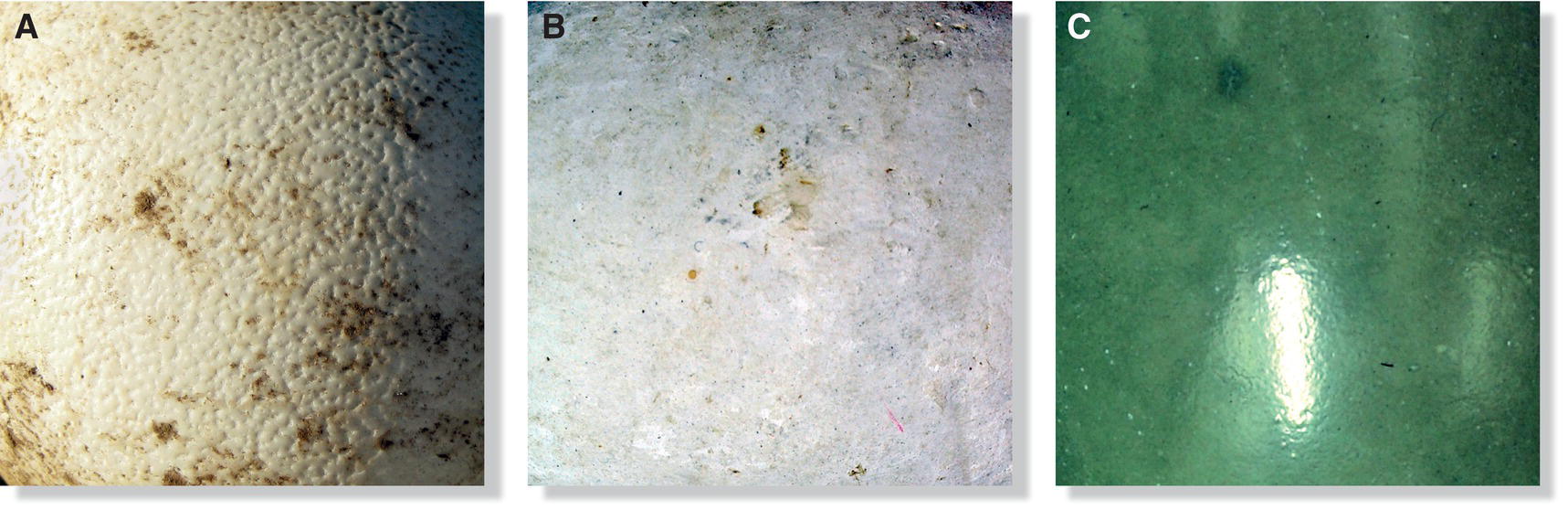

11.5.4 Eggshell color and texture

After the eggs of most species leave the female’s shell gland, pigment glands in the walls of the oviduct deposit successive layers of color on them. The background color of the egg is usually deposited first; any spots, streaks, or other darker markings are added later. The variation in egg coloration and pattern across species is usually correlated with breeding environment. Many birds, particularly those that nest in the open, lay cryptically colored eggs to avoid detection by visual predators. In North and Central America, for example, the color and speckled markings of Killdeer (Charadrius vociferus) eggs, together with the small, flat stones or wood chips used to line the nest, help the nest and its contents blend into the surroundings (Fig. 11.33). In the tropics, Chilean Tinamous (Nothoprocta perdicaria) lay glossy, chocolate‐colored eggs with a purple hue; cassowaries of Australia and New Guinea lay pitted, avocado‐colored eggs. Although striking when seen out of context, these colors actually blend in quite well in their nests on the forest floor.

Fig. 11.33 Well‐camouflaged eggs. Killdeers (Charadrius vociferus) and other birds that nest in the open often lay eggs with colors and patterns that blend in with the surroundings.

(Photograph by William Sproul Sweet.)

Colorful eggs do not always provide camouflage, however. Although tinamou eggs are among the most beautiful in the world (they are shiny and come in many colors), those of some tinamou species do not blend in well with their surroundings. For example, the Great Tinamou (Tinamus major) of Central and South America lays bright, blue‐green eggs that stand out against the generally dark ground. It has been hypothesized that such conspicuous egg coloration deliberately heightens vulnerability to predation or brood parasitism in order to incentivize the male to incubate more attentively. Alternatively, vibrant egg coloration may have evolved to provide benefits to the developing embryo, possibly involving protection from ultraviolet radiation, mediation of photoperiodic synchronization, or antimicrobial defense.

Some birds lay white eggs without any other markings. These species generally nest in dark holes (such as petrels, kingfishers, and woodpeckers), begin incubation with the first egg (such as hawks and owls), or cover their eggs when they leave the nest (such as grebes and some ducks). Because these eggs are hidden from predators hunting by sight, they do not need colors for camouflage. Additionally, pigments may be metabolically expensive to produce or may require dietary precursors that are hard to obtain. For hole‐nesting birds, the white color may provide the added advantage of helping the eggs be more visible to the parents in their dark setting.

Egg coloration and markings are fairly consistent in most bird species. However, there are a few species in which egg color varies considerably—even dramatically—among individuals. Individual Common Murres (Uria aalge), for example, may produce eggs that are deep blue‐green, bright pinkish, warm ocher, pale blue, cream, or white; their egg patterns vary from blotches to lines, with splashes of light yellow‐brown, bright red, dark brown, or black, to no markings whatsoever (Figure 11.32). This variation may help each murre to recognize its own egg among dozens of others within their densely packed breeding colonies. Similarly, the females of several species of African weavers lay eggs in a great variety of colors and spot patterns. This variety seems to facilitate discrimination among a female’s own eggs and those of another of her own species (Jackson 1992) or a brood parasite, such as a cuckoo (Lahti and Lahti 2002).

Bird eggs also vary in texture. Most eggshells have a smooth, matte finish like that of a chicken egg, but there are numerous exceptions. Cassowary and stork eggs are deeply pitted (Fig. 11.34A); grebe and flamingo eggs are chalky (Fig. 11.34B); tinamou eggs are glossy, resembling glazed porcelain (Fig. 11.34C). The greasy surface of most duck and goose eggs may be water resistant. The eggs of the Greater Ani (Crotophaga major) of the neotropics have a chalky white covering that abrades away during incubation to reveal a deep blue color underneath (Fig. 11.35). Anis live in groups in which multiple females lay and incubate eggs in a communal nest, so this change in egg appearance over time provides a ready mechanism by which the incubating caregivers might recognize eggs recently laid by another group member (Riehl 2010).

Fig. 11.34 Variation in egg texture. Although most avian eggshells are smooth, some species lay eggs with (A) pitted, (B) chalky, or (C) glossy surfaces.

(Photographs by: A, Paul André Betancourt; B, Klaus Rassinger and Gerhard Cammerer, Museum Wiesbaden, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Phoenicopterus_roseus_MWNH_0940.JPG. CC‐BY‐SA 3.0; C, Klaus Rassinger and Gerhard Cammerer, Museum Wiesbaden, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tinamus_major_MWNH_0076.JPG. CC BY‐SA 3.0.)

Fig. 11.35 Chalky eggs of communally nesting Anis. (A) Freshly laid Greater Ani (Crotophaga major) eggs appear completely white; the chalky covering abrades away during incubation to reveal a blue shell underneath. (B) Unrelated females form breeding groups and lay eggs around the same time in one communal nest, sharing incubation duties. Egg color change over time is likely an adaptation that allows incubating individuals to discern new eggs from older ones, which in turn helps them identify eggs laid by other females in the group. Based on color, the eggs in this nest have been incubated for roughly the same amount of time—except for the fresh white one, which was added more recently to the nest.

(From Riehl 2010. Reproduced with permission from Elsevier.)

11.5.5 Egg laying

Once all the membrane layers have been deposited and the shell and pigmentation are complete, the egg passes through the cloaca. Although precise laying times for most species are not known, a pattern seems to hold: the larger the egg, the longer the laying process. Brood parasites have evolved to lay their eggs remarkably quickly, before the host returns to its nest. Common Cuckoos (Cuculus canorus), for instance, can lay an egg in another bird’s nest and disappear in less than 10 seconds (Seel 1973).

The time required for the oviduct to secrete the layers around the ovum determines the interval between laid eggs. Small shorebirds, domestic chickens, woodpeckers, rollers, and most passerines lay eggs about 24 hours apart. In contrast, birds such as ostriches, rheas, herons, storks, cranes, bustards, gulls, doves, owls, hummingbirds, swifts, kingfishers, as well as some accipiter hawks and cuckoos, generally lay eggs every other day. Larger species tend to need more time between eggs, perhaps because the secretion processes in the oviduct take longer for larger eggs. Among waterfowl, for instance, many duck species lay eggs every day, whereas large geese and swans lay every other day. Parrots, even the smaller species, lay their eggs 1–3 days apart. Penguins take 3–6 days between eggs, and the Masked Booby (Sula dactylatra) of tropical seas worldwide lays its two eggs as much as a week apart. Species that lay very large eggs for their size also tend to need longer intervals between eggs: megapodes wait 4–8 days between eggs, whereas kiwis, in the rare event that they lay multiple eggs within a season, need 14–30 days. Most bird species appear to lay successive eggs at approximately the same time of day, usually in the early morning—although some herons, bitterns, and parrots lay at intervals that are decidedly not multiples of 24 hours.

11.6 Clutch size

A clutch is the total number of eggs laid in an uninterrupted series, during a single nesting period, by one female bird. In the early days of ornithology, egg collectors from all over the world amassed large collections of bird eggs (Box 13.04). Clutch size is therefore often the only core avian life history trait for which any quantitative data exist; as a result, there has been considerable interest for almost a century in trying to understand patterns of variation in clutch size. During the 1940s, David Lack at Oxford University (UK) began studies on the clutch sizes and life histories of several local bird species. Many of these studies continue to the present day, providing contributions to avian life history theory that are covered in Chapter 13.

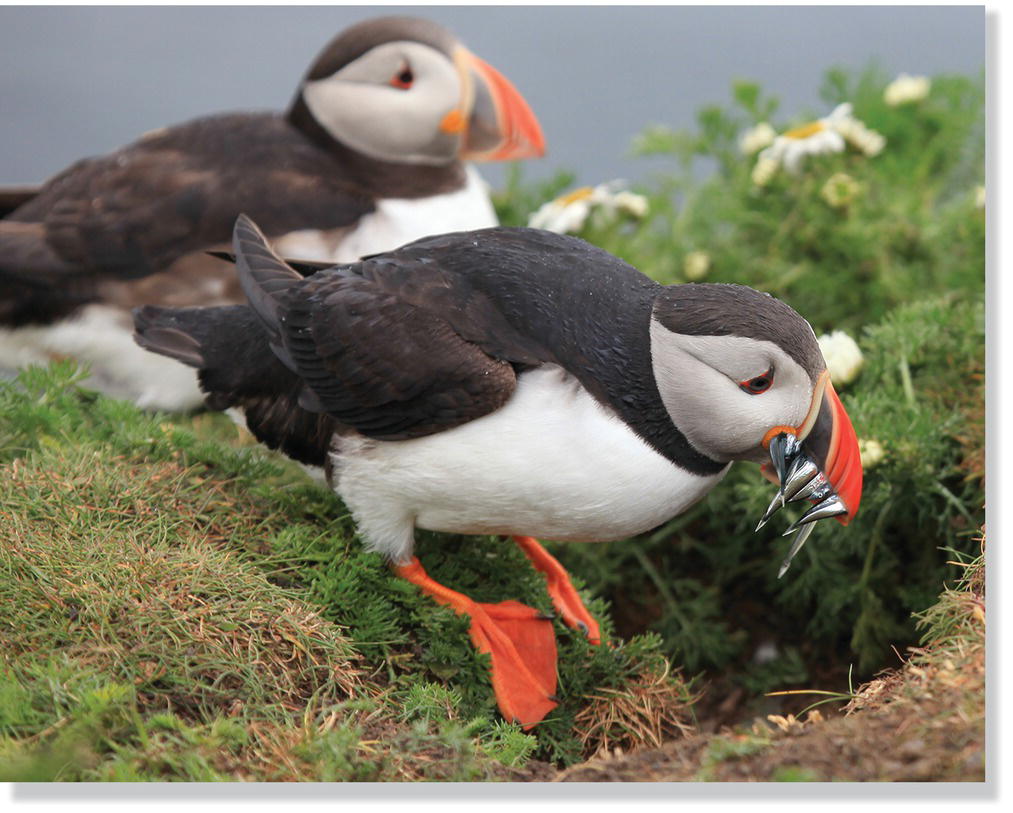

Closely related birds tend to have clutches of similar size. For example, all tubenosed seabirds (such as albatrosses and petrels) lay a single egg, virtually all hummingbirds lay two eggs, shorebirds do not lay more than four eggs, and so forth. Most songbirds lay between two and six eggs, although some tits in Eurasia lay extraordinarily large clutches of up to 17 eggs.

11.6.1 Clutch size and food availability

Food availability may be the most important factor influencing clutch size. Among non‐passerines, birds that feed their young (such as gulls and storks) tend to lay fewer eggs than those whose young forage on their own (such as pheasants, grouse, quail, megapodes, and most shorebirds and waterfowl). The availability of food for the laying female is often an important limitation; since laying an egg is energetically costly for the female—even in places with abundant resources—doing so without an adequate food supply threatens a female’s survival or her subsequent reproductive efforts. Thus, even though females are still physiologically capable of laying more eggs, they often limit their egg production (and thus clutch size) when food is scarce.