Chapter 6

Avian Anatomy

Howard E. Evans

Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine

Much of the thrill we experience when watching and learning about birds centers around their collective ability to sing, to fly and dive, to attract mates, to build nests, to forage, and to produce and care for young. Yet rarely do we consider just how the bird’s body actually accomplishes these wonders. Exactly what are the various parts and pieces that work together to make a bird?

Birds come in a variety of shapes and sizes. Yet compared to other classes of vertebrates, birds are all rather similar to one another—built on the same basic plan, with the same basic parts. Even birds as distinctive as ostriches, hummingbirds, ducks, and penguins have the same anatomical foundation: a rigid beak, a relatively long neck, two wings, at least partially fused vertebrae, strong hindlegs, and a short tail. No living bird varies from this basic design.

Similarly, just about everything relating to a bird’s anatomy has been shaped by the demands of flight—all birds come from flying ancestors, even the species that do not fly today. Flight is extremely demanding and creates strong anatomical and physiological constraints. Therefore, birds have lightweight, rigid bodies with extremely efficient internal systems, particularly those that facilitate motion and respiration.

In this chapter we discuss the important features that are mostly “inside” a bird, considering the internal organ systems one by one to understand the component parts. Keep in mind that these systems rarely function independently, and that their interaction and integration are of vital importance. Much of the pleasure in understanding avian anatomy lies in discovering how these systems work together to allow birds to live such varied lifestyles.

The anatomical terms used in this chapter were agreed upon by an international committee of avian anatomists, who deliberated for several years at meetings of the World Association of Veterinary Anatomists. The resulting illustrated list was published as the Handbook of Avian Anatomy: Nomina Anatomica Avium (Baumel et al. 1993), and it remains the standard reference for avian anatomical terminology.

6.1 Skeletal system

The skeletal system is composed of bone and cartilage, which support and protect the soft structures of the body (Box 6.01). Birds have lightweight skeletons, an adaptation that allows them to minimize the energetic costs of flight, carry heavy eggs, and later incubate those eggs without breaking the shell. Species that do not engage in flight often or at all, typically have thicker, heavier bones. However, contrary to popular belief, bird skeletons contribute proportionately as much to their total body and soft‐tissue mass as do the skeletons of terrestrial mammals (Prange et al. 1979). Yet bird bones are indeed lightweight with respect to their strength and stiffness per unit of bone mass when compared with mammals (Dumont 2010).

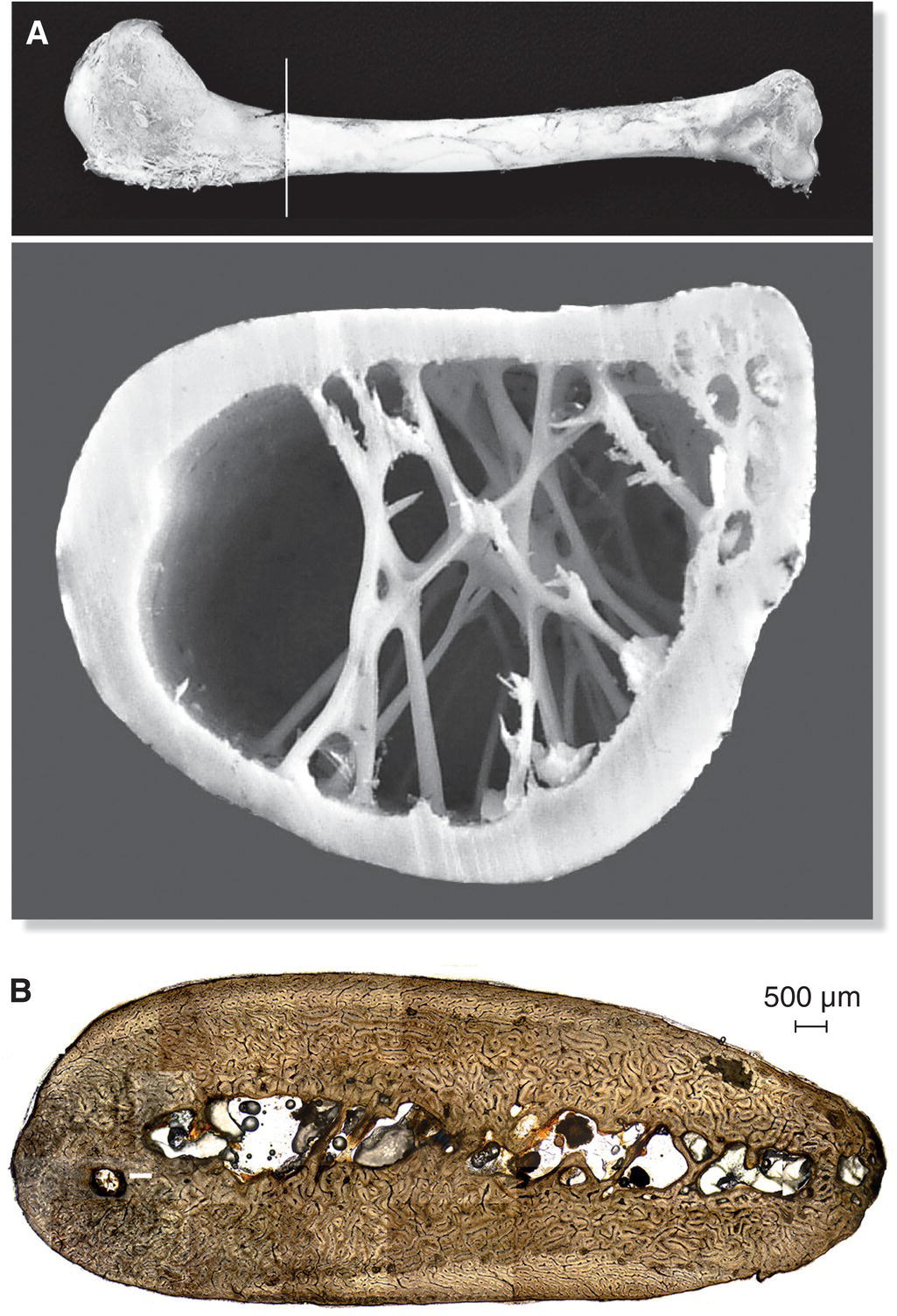

Like the bones of other vertebrates, bird bones contain marrow, which consists of blood‐forming cells and fatty tissue. However, most bones in a bird’s skeleton are pneumatic, meaning they also include spaces filled with air that keep the weight of their bones minimal for efficient flight (Fig. 6.01). Air spaces in a bird’s skull bones usually connect with nasal passageways; the air spaces in the humerus, vertebrae, sternum, ribs, pelvis, and femur are connected either directly to the lungs or to air sacs (which connect bone cavities with the lungs). Although some other vertebrates have air cavities in their bones, birds are the only ones in which bone cavities are connected to the air sacs and lungs. The largest and most efficient flying birds, such as albatrosses and frigatebirds, even have interconnected air spaces passing through their joints (such as from the humerus of the wing into the digits), further reducing their weight. The connection between the respiratory system and air cavities within bones comes at a price, however: injury to a pneumatic bone—such as a gunshot—allows blood from broken vessels to enter air passageways and the lungs, often resulting in death.

Fig. 6.01 Internal bone structure in flying versus flightless birds. (A) Flying birds typically have lightweight, pneumatic bones for weight efficiency in flight. Despite being mostly hollow, internal struts—as seen here in this cross‐section of a Whooper Swan (Cygnus cygnus) humerus—provide structure and strength. (B) In contrast, flightless birds often have heavy, less pneumatic bones, as seen in this cross‐section of a Chinstrap Penguin (Pygoscelis antarcticus) humerus.

(A, from Pennycuick 2008. Reproduced with permission from Elsevier. B, photograph by Laura E. Wilson.)

Bones provide sites for the attachment of muscles, which move the skeleton. Bones act mechanically like levers for the action of muscles, and continued use results in the formation of a bump—or process—where the muscle attaches. These features are so characteristic that they often serve as landmarks in fossil bones, helping researchers precisely identify a particular bone type, discern the presence of a muscle long since decayed, or even identify the species of the bird.

One might assume that once fully formed, adult bones are dead structures that remain the same throughout life—similar to coral or seashells—but this is not the case. Bone is a tissue composed of living cells in a matrix called osteoid, a gelatinous substance made of fibrous protein. It has a blood supply that constantly deposits or moves mineral components from one place to another. Bones are therefore very much alive, constantly changing shape and composition in response to fluctuations in diet and physical stress caused by movement. When a muscle contracts and pulls on a bone, it activates resorption (breaking down/taking away) or deposition (provision) of calcium. The calcium residing in one bone in the morning may move to another bone by the afternoon, or to an eggshell if the bird is in the process of completing a clutch (Chapter 11). The transfer of calcium occurs constantly, but it is especially important during the healing process and can serve as a buffer of sorts when abnormal pressure is placed on a bone.

Cartilage is also composed of living tissue with cells and a blood supply; it is capable of growth and resorption as well as ossification (transformation into bone). During development, cartilage becomes bone very rapidly. As a bird grows older, this process slows down. Bone also can be formed directly without going through a cartilage stage. Such direct ossification occurs in skull bones in most birds, and tendons of the leg muscles in some species.

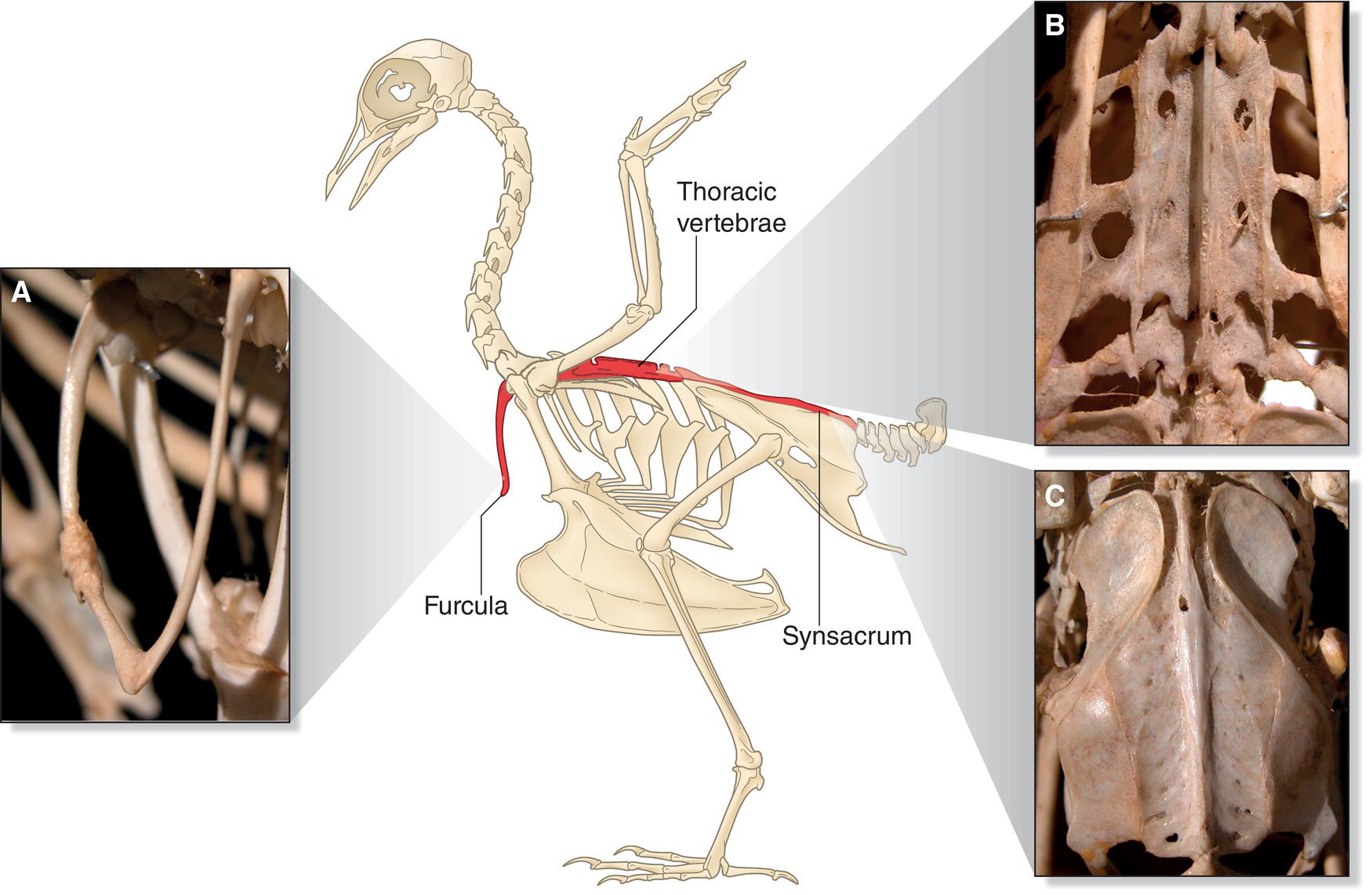

Birds are unlike most other vertebrates in having several fused vertebrae as well as regions of fusion in their collarbones and in the pelvis (Fig. 6.02). This fusion makes these structures more rigid, thereby strengthening the avian skeleton so it can handle the stressful actions of landing, jumping, and flying. The skull bones of a bird are fused to one another as well, which helps prevent damage that might occur from the impact of using the beak like a chisel and hammer, as exemplified by woodpeckers. Although this fused skeleton does not allow for as much overall body mobility in birds compared with many other vertebrates, birds partially compensate by having unusually long, flexible necks.

Fig. 6.02 Avian skeletal fusion. Fused bones support several large muscle‐bearing regions, allowing birds to maintain lightness without sacrificing the strength necessary to make powerful movements (like wingstrokes). The three main regions of fusion occur in: (A) the clavicle bones, fused into the singular furcula (where the major flight muscles attach), (B) the thoracic vertebrae that support the ribs and air sacs, and (C) the synsacrum, formed by the fusion of the sacral and pelvic bones, which aids in shock absorption during landing and jumping.

(Illustration adapted from Proctor and Lynch 1993. Reproduced with permission from Yale University Press. Photographs by Renn Tumlison, Henderson State University.)

By convention, the avian skeleton is divided into an axial skeleton (the head, neck, trunk, and tail) and an appendicular skeleton (the pectoral and pelvic girdles, wings, and legs).

6.1.1 Axial skeleton

The skull is composed of a cranium (braincase) that incorporates the ear opening on the lower rim of each side (Fig. 6.03). In adult birds, most of the cranial bones are fused so completely that any sutures (seam‐like junctions between two bones) or boundary lines are virtually undetectable. Therefore, the presence of skull sutures indicates that a bird is still young.

Fig. 6.03 Avian skull. The cranium of an adult Budgerigar (Melopsittacus undulatus) does not have notable sutures, the joints found in the skulls of most non‐avian vertebrates and in young birds. The large eye orbit, smaller ear opening, and jaw bones (maxilla, dentary, quadrate, articular) are all evident in this side (lateral) view.

(Adapted from Evans 1996. Reproduced with permission from Howard E. Evans.)

The large orbits—or eye sockets—of the avian skull are so deep that the eyes almost meet on the midline of the skull. Only a thin, sometimes incomplete, interorbital septum separates them. Aside from the bill, the orbits are the most prominent feature of the bird skull. Attached to each side of the skull, the lower jaw, or mandible, consists of two bones on each side, the dentary and the articular. The dentary bones almost meet at the tip of the bill, though there is a V‐ or U‐shaped (depending on the species) space between the two bones. The upper jaw is often referred to as the maxilla and is embedded into the forehead and the sides of the skull via the three‐pronged intermaxillary bone. Both jaws are attached to a movable, rectangular, quadrate bone on each side of the skull (Fig. 6.03).

The terms bill and beak are often used synonymously in referring to bird anatomy; both refer to the rostrum, or external part of the mouth. Bird’s beaks (and talons) are composed of a bony core, followed by a thin vascular layer of tissue with nerve endings and blood vessels, and covered with a sheath of keratinized integument called the rhamphotheca (Fig. 6.04). In many birds, such as passerines, the rhamphotheca is dry, hard, and horn‐like; in others, such as waterfowl, it is soft and supple.

Fig. 6.04 Rostrum of the bill. Vascularized, nerve‐rich tissue covers the bones forming the bill (and talons). It is coated with rhamphotheca, a protective, keratinized integument that can be soft or stiff, depending on bill function.

(Illustration by N. John Schmitt.)

A bird’s cranium joins the bones of the jaw at a semiflexible craniofacial hinge, which is apparent in any skull (Fig. 6.05A). This hinge articulates with numerous other bones in the jaw, as well as both mandibles, when birds open and close their bills. The bill opens (Fig. 6.05B) when the quadrate bone pivots forward, pushing on the jugal arch and palatine, which lifts the frontal portion of the maxilla, called the premaxilla. This, in turn, rotates the maxilla up at its junction, the craniofacial hinge. When the bill begins to close again (Fig. 6.05C), the actions are reversed: the craniofacial hinge rotates down, the premaxilla and maxilla drop, and the quadrate rotates back. This ability to move both jaws (as opposed to one of the jaws remaining stationary, as in most mammals) is called cranial kinesis. Such movement or kinesis allows the bill to grasp food with forceps‐like precision. Cranial kinesis also allows a bird to manipulate food within its mouth to aid in swallowing. In some bird species, the upper and lower bills are also flexible, due to bony units called elastic zones. Movement of the bill in this region is known as rhynchokinesis (Fig. 6.06); diverse species of shorebirds, snipes, and woodcocks demonstrate this ability (Chapter 8).

Fig. 6.05 Cranial kinesis. (A) The closed, resting position of a bird’s jaw shows that the maxilla and dentary are in contact. The cranium sits on the craniofacial hinge in a neutral position. The articular and the quadrate are also in neutral positions, held in place by the slight pressure of the jugal arch and palatine bones. (B) When the quadrate bone pivots forward, it begins to push on the jugal arch and palatine, lifting the premaxilla and opening the jaw from the craniofacial hinge. (C) When the bill begins to close again, the actions are reversed: the craniofacial hinge rotates down, the premaxilla and maxilla drop, and the quadrate rotates back.

(Adapted from King and McLelland 1975. Reproduced with permission from Elsevier.)

Fig. 6.06 Rhynchokinesis. Elastic zones of both the upper and lower bill permit some species, like this Bar‐tailed Godwit (Limosa lapponica), to flex the tips of their bills, as in the top image. When the bird is probing in the mud, this ability allows such species to grip slippery prey.

(Photographs by Jon Irvine.)

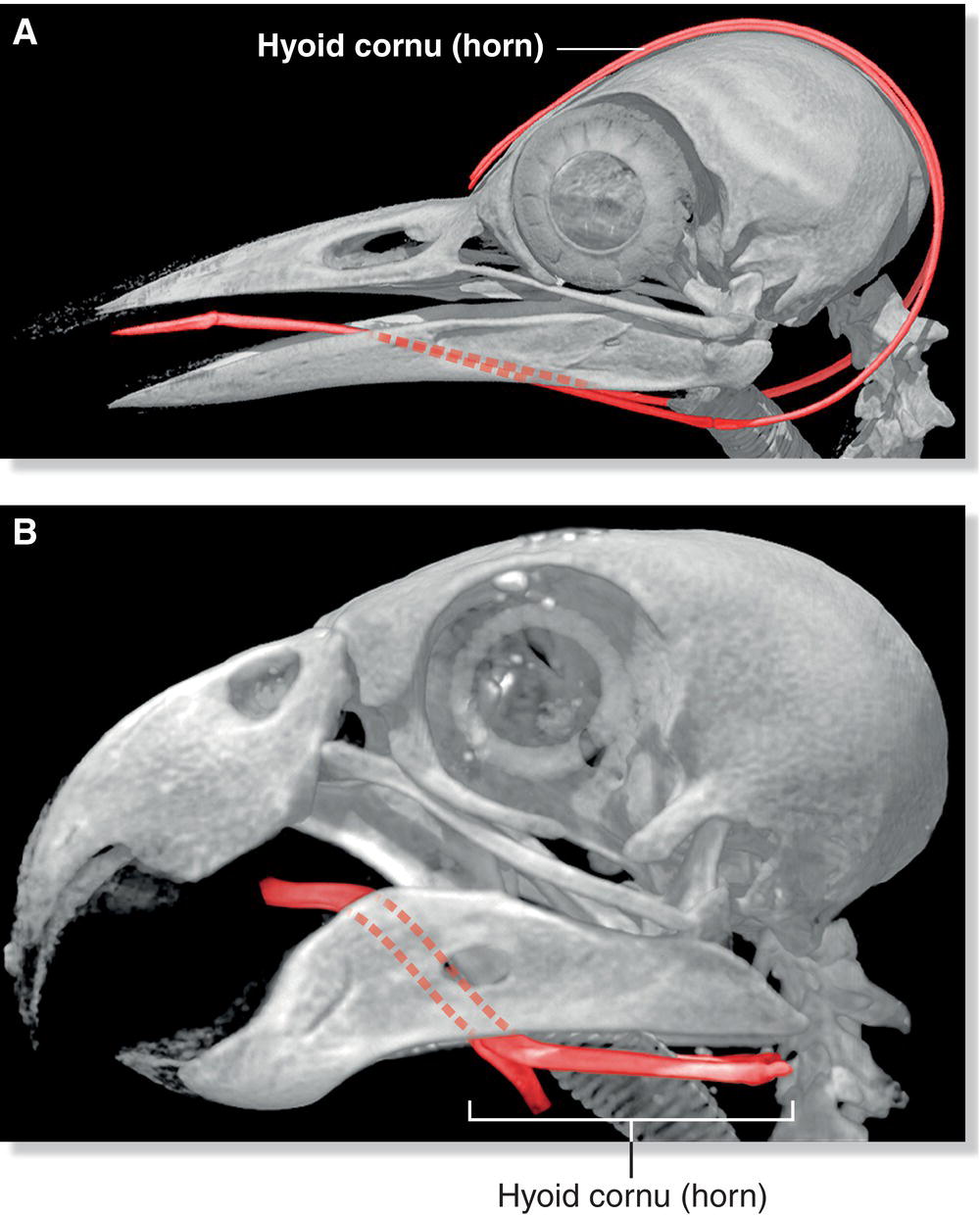

Positioned between the lower jaws, a series of articulated bones called the hyoid apparatus supports the tongue. (More generally, the term “apparatus” refers to a collection of the bones and cartilages that forms a particular structure.) The muscles that attach to the hyoid bones extend and retract the tongue. Each cornu or horn of the hyoid is composed of two bones that curve around the back of the skull. These cornua are particularly long in woodpeckers (Fig. 6.07A) and other birds that are able to protrude their tongues (Chapter 8). Many birds, especially granivores and carnivores, cannot protrude their tongues; these birds have shorter hyoid horns and use their tongues to manipulate food within their oral cavity instead (Fig. 6.07B).

Fig. 6.07 Hyoid apparatus. The bones that support the tongue and aid in manipulating food are anatomically distinct in different groups of birds, reflecting their dietary needs. (A) The hyoid apparatus of the Eurasian Green Woodpecker (Picus viridis) is exceptional, with cornua bones wrapping around the back of the skull to house the long, protruding tongue. (B) Many granivorous and frugivorous birds like the Golden‐winged Parakeet (Brotogeris chrysoptera) have non‐protruding tongues and small hyoids, as food is processed in their mouth.

(Courtsey of DigiMorph.org.)

No living bird has teeth, although several birds, particularly fish‐eaters like mergansers, have serrated bills to grip fish. Ancient Jurassic birds, such as Archaeopteryx (Chapter 2), had teeth, as did most birds throughout the Cretaceous—although various lineages lost their teeth independently of Neornithines, the line leading to modern birds.

6.1.2 Vertebral column

The avian vertebral column, or backbone, consists of a series of articulating or fused vertebrae that vary in number depending on the species. As in other vertebrates, the vertebrae are named and numbered for each region: cervical in the neck, thoracic in the ribcage, lumbar in the lower back, sacral in the pelvic region, and caudal in the tail (Fig. 6.08). In birds, however, various fusions of bones blur some of these distinctions.

Fig. 6.08 Avian vertebral column. Fused in various areas but articulated in others, avian vertebrae are distinguished by their location and vary in number depending on the species. The cervical vertebrae begin at the skull attachment site, followed by the thoracic vertebrae supporting the ribcage, the lumbar vertebrae extending through the lower back, the sacral vertebrae—fused bones of the pelvis—and finally the caudal vertebrae, including the fused pygostyle tail‐supporting vertebrae.

(Adapted from Proctor and Lynch 1993. Reproduced with permission from Yale University Press.)

Most birds have 14 or 15 cervical vertebrae, but this number varies: cuckoos and most passerines have 12, while swans have 25. Surprisingly, however, the number of cervical vertebrae in a given bird species does not generally correlate with neck length, and several kinds of long‐necked birds have fewer cervical vertebrae than some short‐necked species. Overall, the relatively large number of cervical vertebrae in birds allows for a marked suppleness of the neck and easy turning of the head; birds have no trouble looking behind themselves. Some species with unusually short necks (such as woodcocks) compensate by having a large field of vision, facilitated by the special position and size of their eyes, which eliminates the need to turn their head.

The atlas, or first cervical vertebra, is small and articulates with the single occipital condyle on the base of the skull (Fig. 6.09). The second cervical vertebra, or axis, has a peg‐like process that extends through the atlas and attaches to the skull via a ligament. The remaining cervical vertebrae have fused rib remnants called pleuropophyses, residual from the period when every tetrapod vertebra had associated ribs. When cervical vertebrae support ribs, which may not reach the sternum (breastbone), it is difficult to distinguish them from thoracic vertebrae; therefore, the term cervicodorsal vertebrae is sometimes used for this entire region.

Fig. 6.09 Attachment sites and movement of the skull. These views of the skull and first three cervical vertebrae of a Ruffed Grouse (Bonasa umbellus) show how these bones fit together to allow almost full rotation of the head. The occipital condyle is a small bulge extending from the posterior base of the skull. The first cervical vertebra—the atlas—fits into the occipital condyle via peg‐like processes, which permit spinal movement while maintaining head and neck support. The second cervical vertebra, the axis, similarly connects with the atlas. (A) The bones articulated in their natural orientation; (B) the first three cervical vertebrae from above (dorsal), side (lateral), and below (ventral) views; and (C) the back of the skull.

(Illustration by Misaki Ouchida © Cornell Lab of Ornithology.)

When a rib articulates with the sternum, either directly or by a ligament, the associated vertebra is considered a thoracic vertebra. Most birds have four to six thoracic vertebrae. In chickens, pigeons, herons, flamingos, and many other birds, some of the thoracic vertebrae fuse with one another to form a notarium, which provides even more rigidity to the backbone.

The ribs, together with the thoracic vertebrae above and the sternum below, form a bony thoracic cage enclosing the heart, liver, and lungs as well as the thoracic air sacs. Each thoracic rib has a dorsal and a ventral part connected by a cartilaginous hinge. The upper or vertebral rib articulates with a thoracic vertebra; the lower segment or sternal rib articulates with the sternum. Because a bird has no diaphragm to produce negative pressure for drawing in air, this hinged arrangement allows the thorax to act as a bellows. The sternum moves downward and forward to expand the thorax during inhalation, then upward and backward for compression during exhalation. The inhaled air enters the air sacs, which expand. The lungs remain the same size during inhalation and exhalation because they are fixed between the ribs and vertebrae within the thoracic cavity.

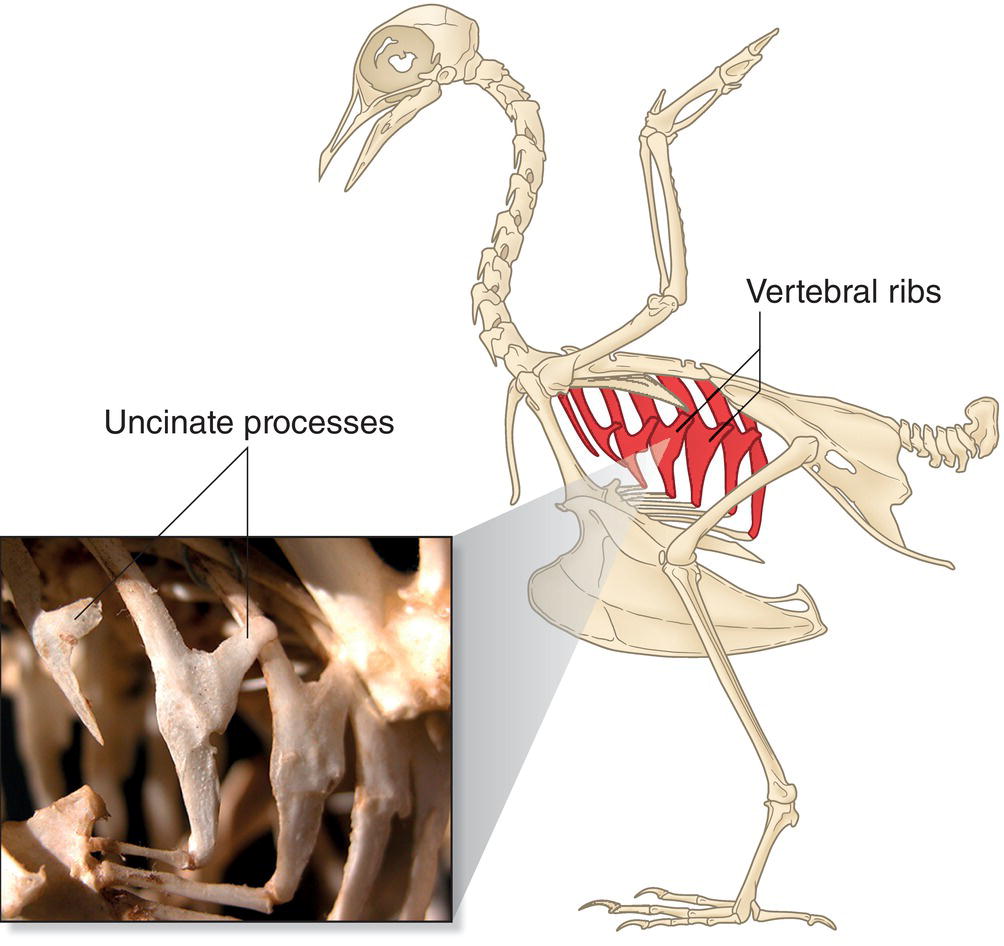

Unique to birds and some reptiles, flat extensions of bone called uncinate processes project caudally from the vertebral ribs. Each process overlaps with the rib behind it, providing more secure attachment sites for the muscles, which in turn strengthen the rib cage (Fig. 6.10).

Fig. 6.10 Uncinate processes of vertebral ribs. These structures provide an increased surface area for muscle attachment, strengthening the ribs. They exist only in birds and some reptiles.

(Illustration adapted from Proctor and Lynch 1993. Reproduced with permission from Yale University Press. Photograph by Renn Tumlison, Henderson State University.)

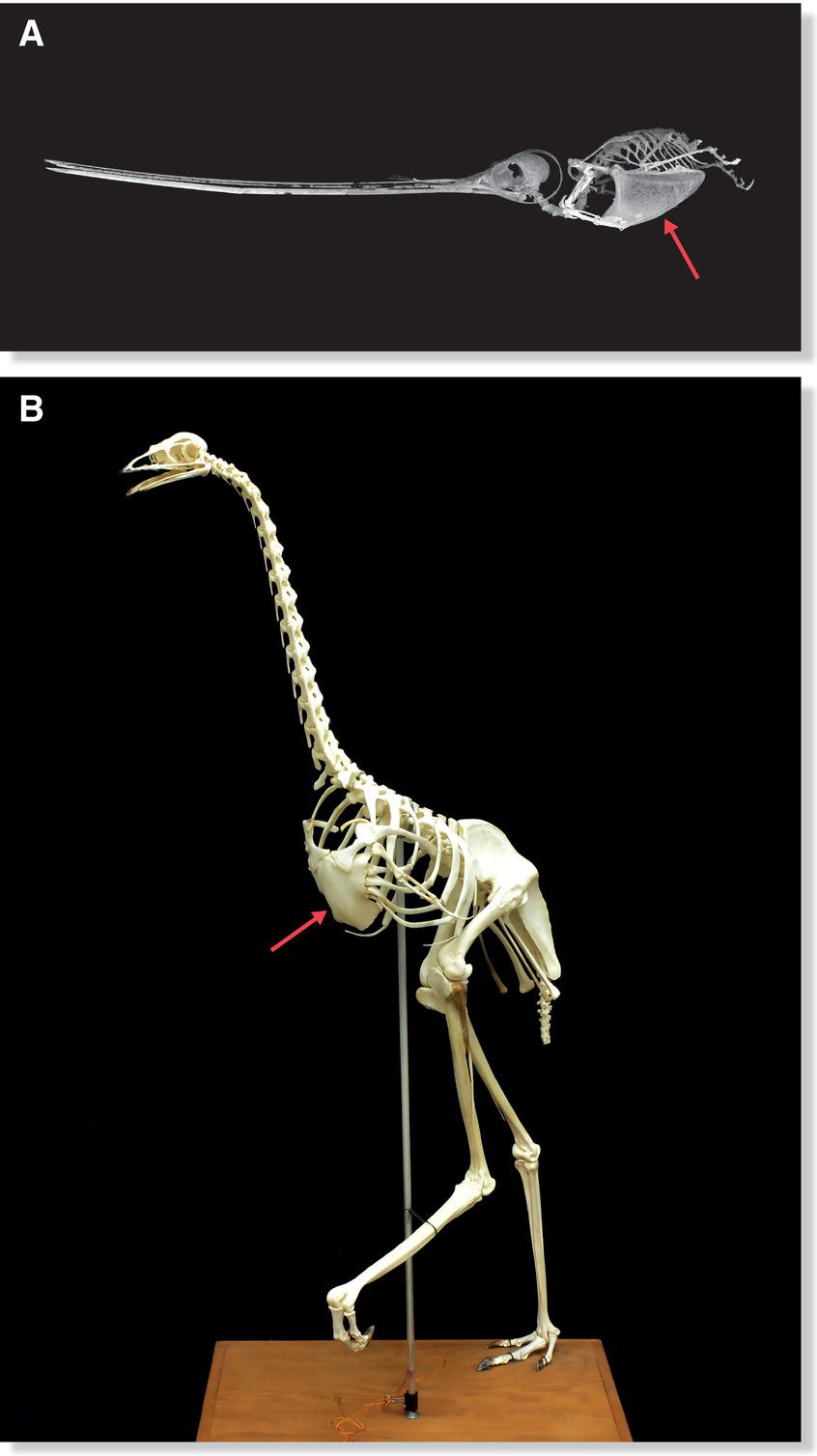

Some birds, called carinates, have a ridge along their sternum called the mid‐ventral keel, or carina. The pectoralis and supracoracoideus muscles, which provide power for each wing stroke during flight or swimming, attach to the carina and constitute about one‐fifth of the muscle weight of most birds. By looking at a bird’s sternum, one can judge the relative size of its pectoral muscles and consequently its flying ability. Hummingbirds, which are agile fliers, have the largest keel of any bird relative to body size (Fig. 6.11A). Large, flightless birds such as the Ostrich (Struthio camelus) of Africa, Emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae) of Australia, rheas (Rhea species) of South America, and cassowaries (Casuarius species) of New Guinea have flat, raft‐like sternums with no carina (Fig. 6.11B).

Fig. 6.11 Carinates and ratites. (A) Flying birds have a keel or carina (arrow), a broad and sturdy attachment site for robust flight muscles, protruding from their sternum. The Sword‐billed Hummingbird (Ensifera ensifera) has one of the largest carina‐to‐body‐size ratios, an indication of its powerful flying ability. (B) Large, flightless birds like this Emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae) have no need for a carina; ratite sternums are therefore flat (arrow).

(A, photograph courtesy of Slater Museum of Natural History, University of Puget Sound. B, photograph by Barry K. Rhoades, Wesleyan College.)

Although a solid sternum is more functional for breast muscle attachment, notches and openings exist on the sternum of some bird species. In birds like chickens and turkeys, long processes called xiphisternal horns protrude from each side of the sternum. Covered by a sheath of fibrous tissue called fascia, they serve as attachments for breast muscle. In other birds, such as pigeons, the sternum may have only a notch. If the notch closes as the bird ages, as it does in parrots, only an opening, or sternal foramen, may be left.

A unique feature of the avian vertebral column is the synsacrum (Fig. 6.02C). It consists of a fusion of a few lower thoracic vertebrae with all of the lumbar, all of the sacral, and the first few caudal vertebrae. This rigid segment is fused in turn with the ilium, the upper part of the pelvis. The number of vertebrae involved in the bird’s synsacrum varies from 10 to 23, depending on the species.

A bird’s tail consists of four to nine non‐fused caudal vertebrae and a terminal triangular bone called the pygostyle, which is formed by several fused vertebrae (Fig. 6.08). The rectrices, or tail feathers, attach to the pygostyle. In woodpeckers, a shield‐like disk on the caudal margin of the pygostyle serves as a special attachment for the muscles that depress their rectrices for balance while climbing a tree.

6.1.3 Appendicular skeleton

The avian appendicular skeleton consists of the wing and leg bones, along with their supporting pectoral (shoulder) and pelvic (hip) girdles (Fig. 6.12).

Fig. 6.12 Appendicular skeleton. Consisting of the bones that protrude laterally from the axial skeleton, the appendicular skeleton (shaded) supports movements associated with flying, running, swimming, and jumping.

(Adapted from Proctor and Lynch 1993. Reproduced with permission from Yale University Press.)

Three bones on each side of the body—the clavicle, the coracoid, and the scapula—form the shoulder or pectoral girdle (Fig. 6.13), which provides anchorage for the wing to pivot upon. In nearly all birds, an interclavicle fuses the right and left clavicles to form the furcula, a single V‐shaped bone popularly known as the “wishbone.” In most birds, the ventral end of the furcula is attached to the sternum by a ligament, but in a few birds, such as pelicans, the two bones are actually fused together. In frigatebirds, the coracoids fit tightly to the sternum, but the actual bone‐to‐bone fusion occurs between the coracoid and the furcula. The Budgerigar (Melopsittacus undulatus) and most other parrots have only small remnants of the clavicle on each side; some parrot species have lost the clavicle completely.

Fig. 6.13 Pectoral girdle. The upper part of the appendicular skeleton is the pivot point for powered flight. Major bones in the pectoral girdle include the clavicles (typically fused into a single furcula, or “wishbone”), coracoids (strong bones that hold the shoulder away from the body), and scapula (which meets the coracoid via the glenoid fossa and forms the canalis triosseus with the clavicle).

(Adapted from Proctor and Lynch 1993. Reproduced with permission from Yale University Press.)

Coracoids, the stoutest and strongest bones of the pectoral girdle, hold each shoulder away from the body. The coracoid and scapula meet to form a shallow depression, the glenoid fossa or shoulder joint, in which the head of the humerus wing bone articulates (Fig. 6.13). The broad base of each coracoid bone fits into a groove on the anterior end of the sternum, while each upper end articulates with the scapula and clavicle. This forms an opening called the canalis triosseus, or supracoracoid foramen. In penguins, this foramen (a general term for opening) is very wide, allowing the correspondingly large supracoracoideus muscle to pull the wing forward and upward—a difficult task in swimming, as the upstroke occurs against the force of the water. Similar to a bowsprit, which projects from the front of a sailboat to provide support for the mast’s ropes, the coracoid projects from the sternum to provide the wing with a fixed pivot point away from the body.

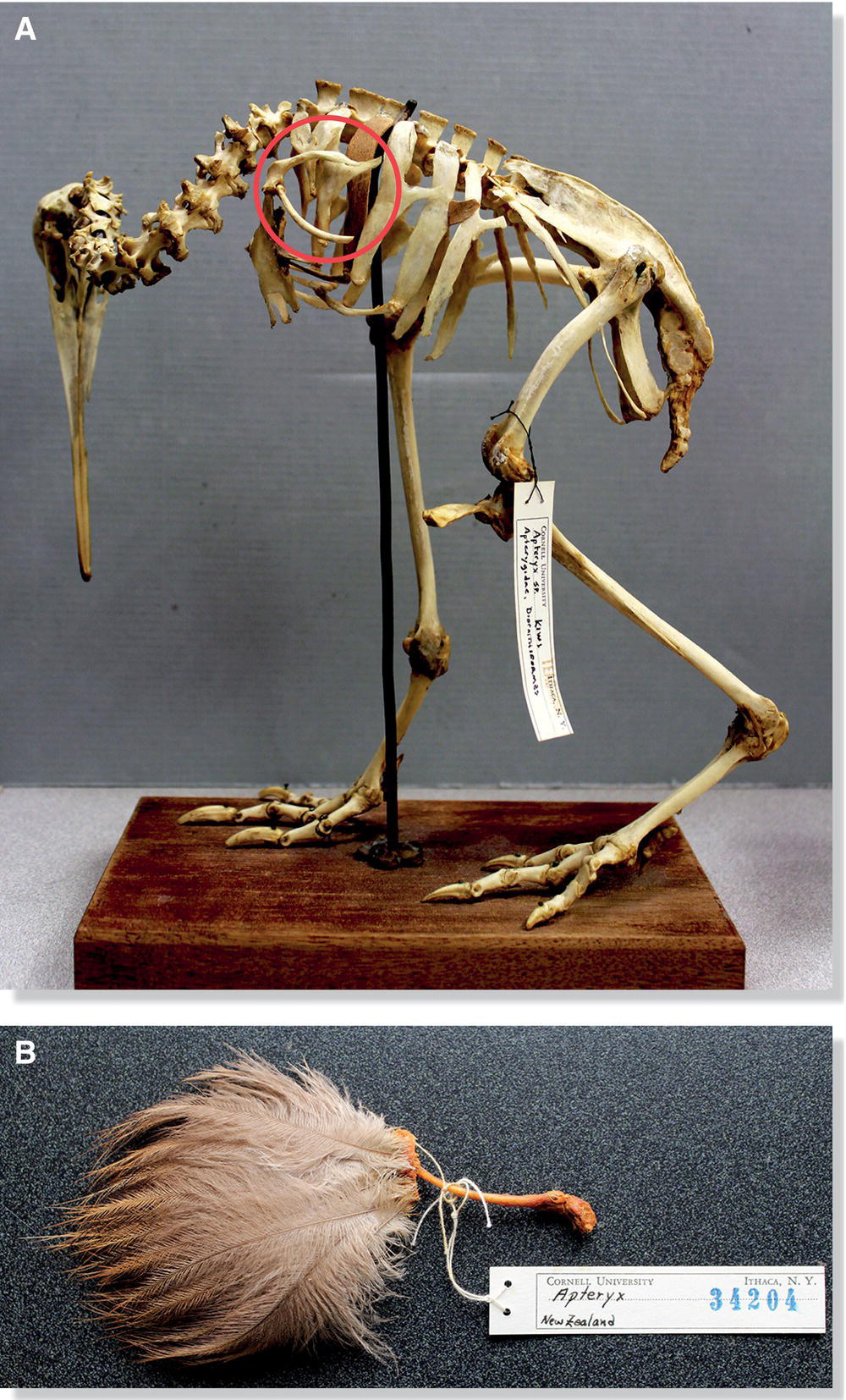

Modern flightless birds show the same basic arrangement of the wing skeleton as flying birds. Wing bones in penguins are simply shortened, flattened, and generally strengthened in a collectively blade‐like manner, forming a flipper to suit the requirements of swimming underwater. Ratite wing bones are also substantially reduced in size and strength. This is especially true for the kiwis of New Zealand, whose tiny wings are hidden beneath their hair‐like feathers (Fig. 6.14).

Fig. 6.14 Reduced wing bones of the flightless kiwis. (A) Fully grown kiwis (genus Apteryx) have proportionally small wing bones (circled). (B) This is an entire kiwi wing; hair‐like feathers attach to the primary wing bones.

(Photographs by Alexandra Class Freeman, courtesy of Cornell University Museum of Vertebrates.)

The metacarpals (hand bones) and digits of birds’ forelimbs (wings) are short and small in number. Several carpal and metacarpal bones have been fused together to form the carpometacarpus, leaving only two carpals in the wrist. All birds have three short fingers, which consist of one phalanx or two phalanges (finger bones) (Fig. 6.15).

Fig. 6.15 Homologies in forelimb bones of three tetrapod vertebrates. Birds are unique in that they have reduced wrist and digit bones compared with other tetrapods.

(Top, adapted from Proctor and Lynch 1993. Reproduced with permission from Yale University Press. Bottom, © Cornell Lab of Ornithology.)

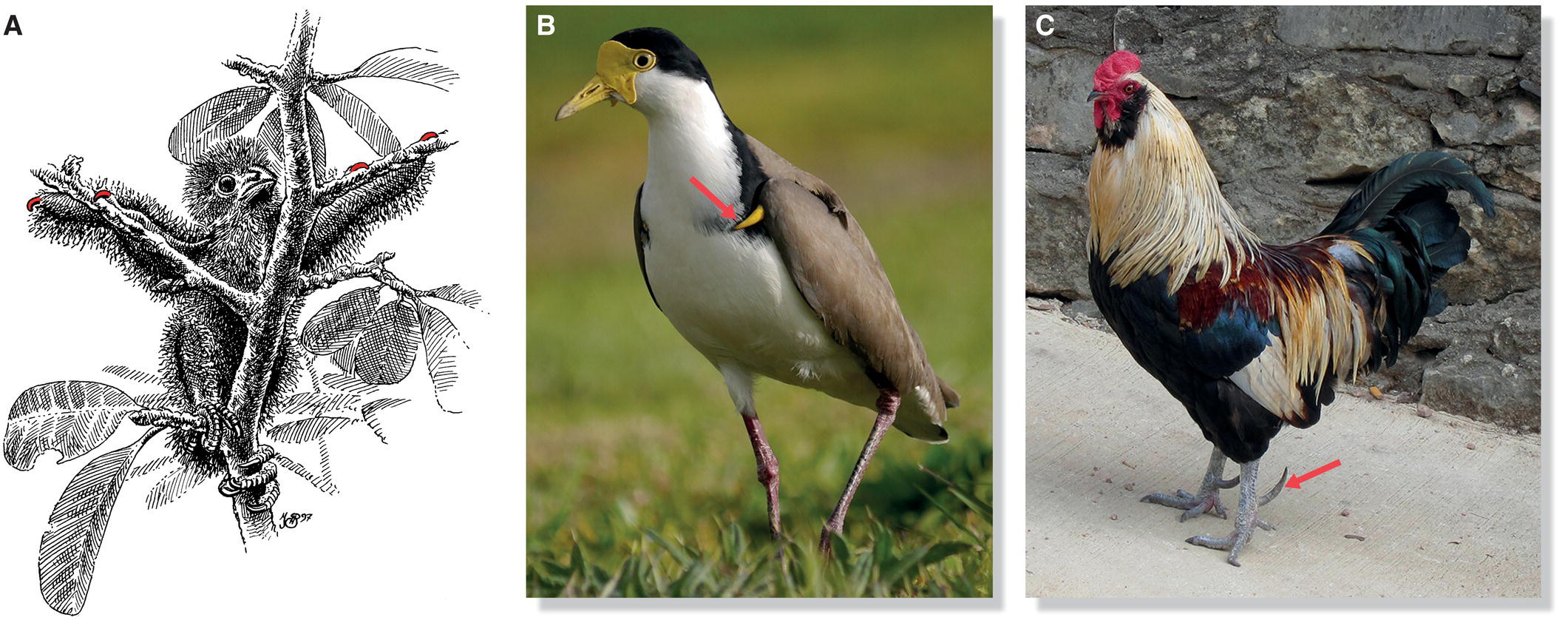

In a variety of birds—swans, ducks, cranes, rails, owls, some passerines, and others—claws may extend from the terminal phalanges. Young Hoatzins (Opisthocomus hoazin), pheasant‐like birds of the Amazon Basin, have temporary claws on their wing digits. When threatened by a predator, Hoatzin nestlings leap from their nests—usually built above water—and use their wing claws to climb back up after the danger has passed (Fig. 6.16A). However, the wing claws on embryos or the young of most living species are likely vestigial, holdover structures from ancestral species that have lost their function. Many ancient groups of birds had claws, including the Enantiornithes (Chapter 2). Claws are associated with digits and are not synonymous with spurs (although some birds have both).

Fig. 6.16 Wing claws versus spurs. (A) Fledgling Hoatzins (Opisthocomus hoazin) leap from their nests to escape predators and subsequently use their wing claws (colored, two per wing)—which grow out like nails from their digits— to climb back into their nests. (B) Wing spurs (arrow) grow from bone that is surrounded by a keratinized sheath, as demonstrated in this Masked Lapwing (Vanellus miles). (C) Leg spurs (arrow) develop in a similar way to wing spurs, and are prominent in roosters and other territorial birds that employ them as weapons.

(A, illustration by N. John Schmitt. Photographs by: B, Kaylene Helliwell; C, Wayne D. Roth.)

Spurs are bony outgrowths that can occur anywhere on the appendicular skeleton. Birds with wing spurs include cassowaries, screamers, some plovers, sheathbills, and jacanas (Fig. 6.16B). In male fowl and pheasants, bone growth is stimulated around a spur papilla on the skin of the tarsometatarsus (Fig. 6.16C). Wing and leg spurs are often employed in aggressive disputes. Indian Peafowl (Pavo cristatus) use their spurs to fight for territories and mates; domestic chicken (Gallus gallus) cocks sometimes fight to the death, causing much bloodshed with their leg spurs.

Transitioning to the hip and leg region, the pelvic girdle has three bones on each side: the ilium, ischium, and pubis (Fig. 6.17). The right and left ilia are fused to the synsacrum, forming a rigid support for each half of the pelvis. In all birds except rheas (whose pubic bones connect ventrally), the pelvis is open below, which facilitates the laying of large eggs (Fig. 6.18).

Fig. 6.17 Bones of the pelvic girdle. Three bones—the ilium, ischium, and pubis—are fused to the synsacrum and provide stability to the hips.

(Adapted from Proctor and Lynch 1993. Reproduced with permission from Yale University Press.)

Fig. 6.18 An open pelvis facilitates egg laying. As shown in this X‐ray, kiwis lay exceptionally large eggs relative to their body size, a feat made possible by their open pelvic bones.

(Photograph courtesy of Otorohanga Kiwi House, New Zealand.)

The femur is relatively short in all birds. The easily visible, usually unfeathered part of the leg is called the tarsus by most ornithologists, but this designation is a bit of a misnomer. That area is composed mostly of fused metatarsal bones, homologous with the human foot between the ankle and the base of the toes. The distal portion of the tibia fuses with the proximal tarsal (ankle) bones to form the tibiotarsus. The tibiotarsus is generally the longest leg bone in birds, double the length of the femur in large wading birds. The fibula is a splint‐like bone that articulates with the lateral condyle (a round bump on a bone that forms a joint) of the femur. The distal end of the fibula has been reduced over evolutionary time. The second, third, and fourth metatarsals fuse with the distal tarsal bones to form the tarsometatarsus, where the toes attach (Fig. 6.19).

Fig. 6.19 Leg bone homology in birds versus humans. Colored bones are homologous in birds (left) and humans (right). Birds have several fused bones that are composites of separate bones in humans. For example, the tibiotarsus in birds is essentially a combination of the knee joint, tibia, and upper tarsus bones in humans. Similarly, the tarsometatarsus in birds is a fusion of the lower tarsus and metatarsal bones in humans.

(Adapted from Brooke and Birkhead 1991. Reproduced with permission from Cambridge University Press.)

The small head of the femur fits deeply into the hip joint or acetabulum. At the lower end of the femur, a patella or kneecap glides in a deep trochlear groove, adding stability to the knee joint. The patella is a bone embedded within the tendon of the quadriceps muscle, a major extensor of the knee joint. In several birds, the patella fuses with the cnemial crest, a ridge at the head of the tibiotarsus for muscle attachment that serves as a projecting lever arm for more rapid extension of the leg. The area that appears to be the knee of a bird is actually the intratarsal joint, which is homologous with the ankle in humans (Fig. 6.19). Thus, birds are digitigrade, walking only on their toes.

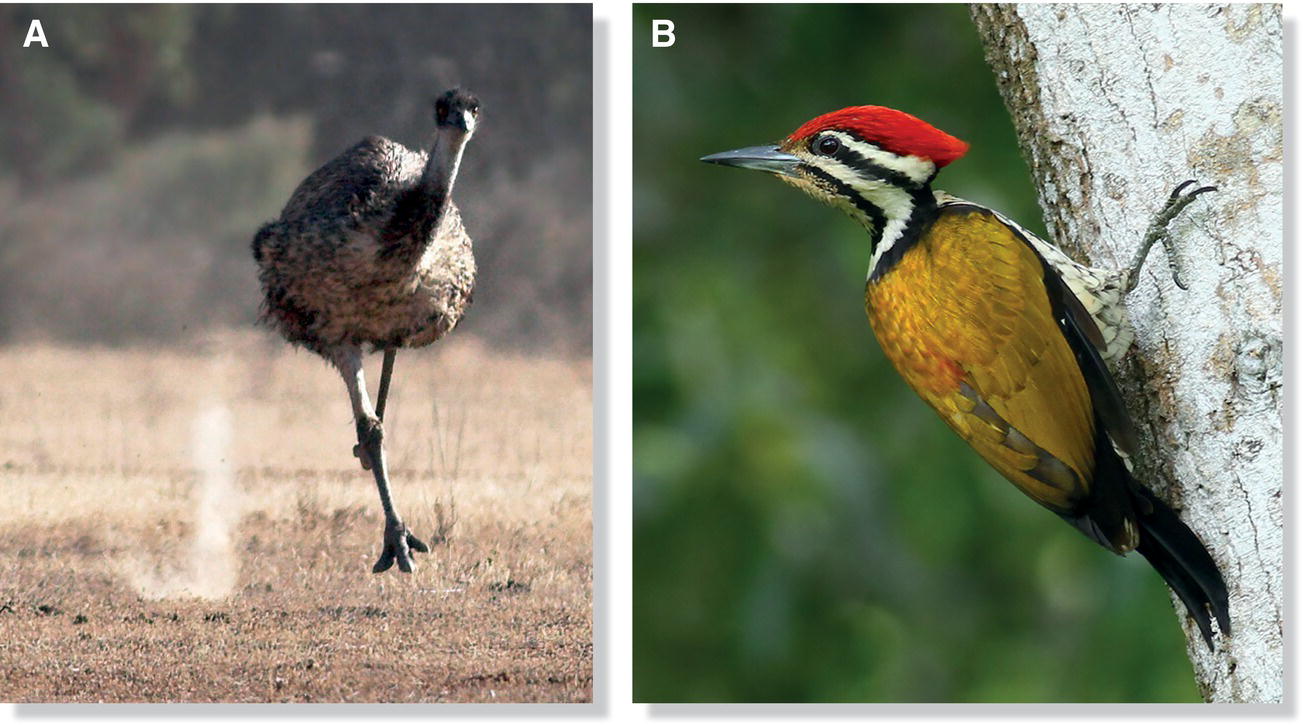

Most birds have four toes on each foot, although some have three. The Ostrich (Struthio camelus) is unique among living birds in having only two toes. Groups with only three toes include most of the other ratites (Fig. 6.20A), some shorebirds such as most plovers and the Sanderling (Calidris alba), some tree‐climbing insectivorous birds including several woodpeckers (Fig. 6.20B), and some birds known for their ability to swim underwater, such as diving‐petrels, auks, murres, and puffins. Several different configurations of toes exist among birds, with whole orders and families often exhibiting a particular configuration (Box 6.02).

Fig. 6.20 Birds can have different numbers of toes. Although most birds have four toes, some species only have three, including (A) the Emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae) and (B) the Olive‐backed Woodpecker (Dinopium rafflesii).

(Photographs by: A, Julian Robinson; B, Eddy Lee Kam Pang.)

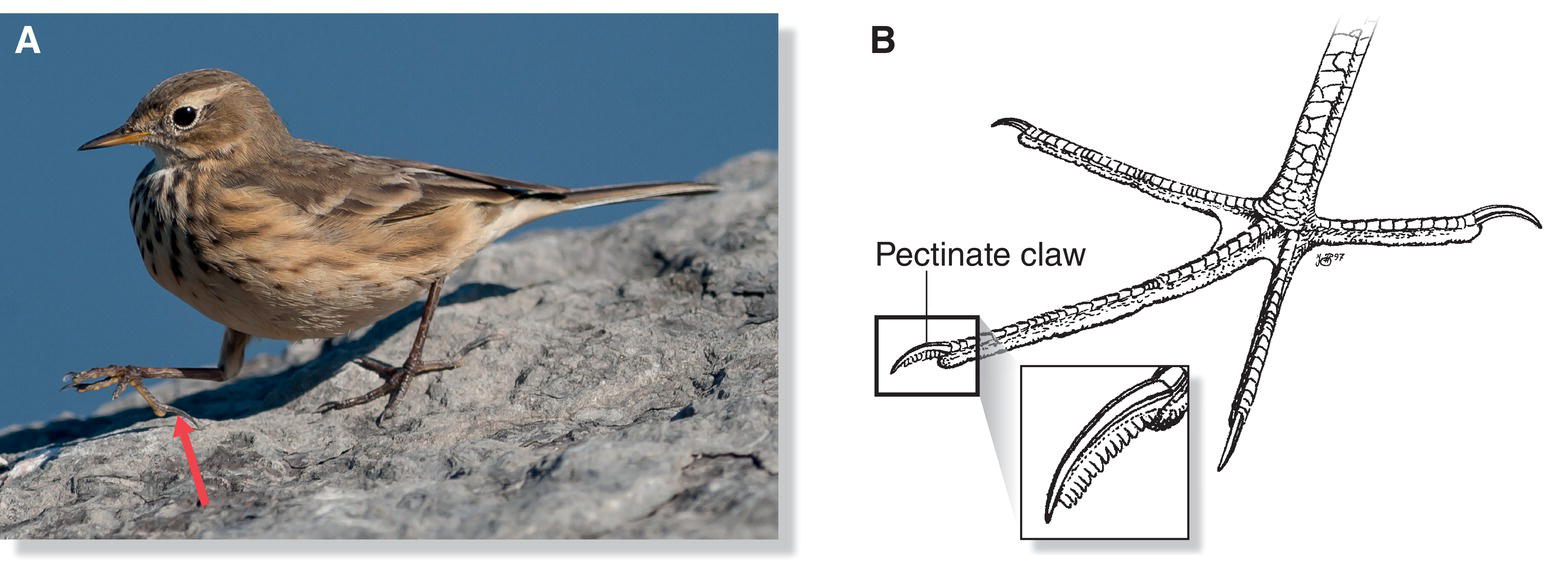

The claws extending from each terminal foot phalanx often reflect a bird’s habits. Species that climb tree trunks, such as nuthatches and creepers, usually have strongly curved claws that help them grasp irregularities on bark without impairing their ability to perch. Many ground‐dwelling songbirds such as larks and pipits are noted for their long hind claws (Fig. 6.21A), which may help them avoid sinking into mud, sand, or other soft surfaces. In a few birds, including Barn Owls (Tyto alba), nightjars, and herons, the claw of the third digit has a comb‐like, serrated edge (Fig. 6.21B). This pectinate claw (sometimes called a “feather comb”) likely functions as a preening or parasite‐removal tool.

Fig. 6.21 Functions of the avian claw. Different groups of birds use the claw on their terminal digit in various ways. (A) American Pipits (Anthus rubescens) are thought to use their elongated hind claw (arrow) to balance on soft substrates as they walk along the ground. (B) A few birds, including herons and some owls, have a pectinate claw on their third digit, a serrated edge that may preen or remove parasites when combed through the feathers.

(A, photograph by Bill Reid; B, illustration by N. John Schmitt.)

6.2 Muscular system

The major role of any skeleton is to facilitate locomotion, but bones cannot move themselves or maintain posture without muscles. Muscle is a tissue composed of contractile fibers that shorten when stimulated by a nerve impulse. When muscles contract, they produce both movement and heat. Tendons attach muscles to bones, transmitting the force of muscles as they contract. Due to the centralization of muscles, the route between a muscle and its eventual insertion into a bone can be long and complex. For example, muscles in the upper leg of birds flex the toes after passing over the intervening ankle and digit joints.

Skeletal muscles—which often have names that indicate their function, location, shape, or derivation—move the skeleton, while smooth muscles are associated with the digestive tract and blood vessels. The heart is made of a special kind of involuntary muscle called cardiac muscle.

6.2.1 Skeletal muscles

Skeletal muscles move the bones and constitute what we generally term the “meat” of an animal (Fig. 6.22). The actions of skeletal muscles are under conscious control and they are therefore often referred to as voluntary muscles. Each muscle consists of several hundred to several thousand muscle fibers bound together by a thin and shiny connective tissue called a fascia. Bridging one or more joints, these bundles of fibers attach to the bone in order to produce movement at the joint when the muscles contract. Connecting fasciae may form a tendon (which in bird limbs may ossify, especially in the legs). Shiny, broad sheets of fasciae that do not form tendons are called aponeuroses.

Fig. 6.22 Skeletal muscles. The major voluntary skeletal muscles of a bird are labeled. Each skeletal muscle consists of several hundred to several thousand individual muscle fibers, bound together by thin connective tissue. Bundles of skeletal muscle fibers attach to bones, producing movement at the joints when the muscles contract. Layers of thin connective tissue form fascia, which in turn form tendons connecting to bone.

(Adapted from Evans 1996. Reproduced with permission from Howard E. Evans.)

Skeletal muscles that move the wings and legs act antagonistically: when one contracts, the other relaxes in a continuous fashion, producing smooth movements. An example of this muscular antagonism occurs during powered flight or wing‐propelled swimming. The pectoralis muscle is responsible for powering the downstroke and the supracoracoideus powers the upstroke. The muscles are positioned on top of one another on the sternum. On the downstroke, the pectoralis muscles contract, pulling the wing bones down (Fig. 6.23A). Simultaneously, the supracoracoideus tendon—which passes through the supracoracoid foramen like a pulley—relaxes, allowing the muscles to extend and release the humerus downward. On the upstroke, the pectoralis muscles stretch, allowing the supracoracoideus to contract and pull the humerus upward via a foramen (passage through the bone) called the canalis triosseus (Fig. 6.23B). The tips of the furcular then return to their relaxed position. More force is required to produce lift from the downbeat of the wing; the pectoralis muscle is therefore the largest muscle in flying birds. Among birds that can fly, relative flight muscle weight often correlates with flying ability: for example, the weight of the pectoralis and supracoracoideus muscles in hummingbirds—swift and maneuverable fliers—may equal 21–34% of their total weight, while these same muscles account for only about 8% of total weight in reluctant fliers like rails.

Fig. 6.23 Skeletal muscle opposition powers flight. (A) The downstroke is powered by the contraction of the large pectoralis muscles (red), which work to pull the humerus down as the supracoracoideus stretches (blue). (B) During the upstroke, the supracoracoideus contracts, enabling its tendon to pull the humerus up while the pectoralis muscles stretch.

(© Cornell Lab of Ornithology.)

6.2.2 Smooth muscle

Smooth muscle, also known as involuntary (visceral) muscle, is composed of spindle‐shaped cells with a central nucleus. Smooth muscles are normally not under voluntary control. These muscles are found in the walls of hollow organs, such as the stomach, as well as in the walls of smaller blood vessels—arterioles and arteries that distribute the heat produced by muscle contraction.

Cardiac muscle is a special category of smooth muscle that forms the bulk of the heart. The muscle fibers are arranged in a network or syncytium of nerve fibers with central nuclei. Cardiac muscle is capable of rhythmic contractions under involuntary control.

6.3 Respiratory system

The avian respiratory system is unique among vertebrates: birds have relatively small, non‐inflatable lungs and nine air sacs that play an important role in ventilation but are not directly involved in the exchange of gases. The air sacs are thin walled and opaque, extending throughout the body cavity and into the hollow bones of birds. Air flows in through the nostrils and mouth of a bird and then travels through its trachea and a series of smaller and smaller tubes (the bronchial system) into the lungs and air sacs.

In large part due to an extremely efficient respiratory system—which, for example, delivers oxygenated air during both inhalation and exhalation—many birds can seamlessly move between normal atmospheric pressures and areas of low oxygen. A Swainson’s Thrush (Catharus ustulatus) might depart from sea level in Florida (USA) on its fall migration, and fly at altitudes of over 2000 meters on the way to its South American wintering grounds; a King Penguin (Aptenodytes patagonicus) might routinely reach depths of 200 meters during a series of 4‐minute dives. These species and many others accomplish such feats via adaptations in their respiratory and circulatory systems.

6.3.1 Nostrils and nasal cavities

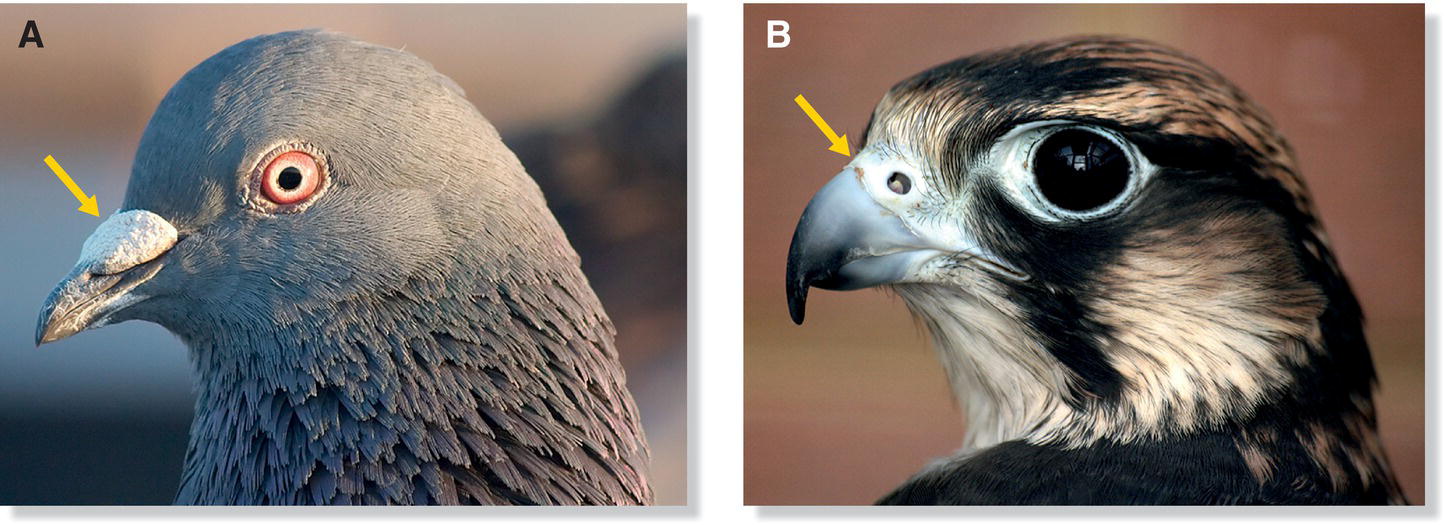

In birds, the nostrils—or nares—usually occur at the base of the bill and open into the nasal cavities. Nares occur in different shapes and sizes, depending on the species. Many ground‐feeding birds, such as starlings, pigeons, and domestic chickens, have independently evolved a protective flap called an operculum. This structure partially covers the nares, presumably to keep out debris (Fig. 6.24A). Some diving species also have opercula, which keep water from entering the nostrils. The nares of raptors, curassows, and some parrots are located in a leathery band of skin known as the cere, a structure that extends across the base of the maxilla (Fig. 6.24B). Ceres often serve as sexual signals, indicating a bird’s sex and/or condition. Kiwis, which have an unusually keen sense of smell and extremely large olfactory bulbs in the brain, are the only birds with nostrils near the tip of the bill—presumably to smell invertebrates while rummaging through leaf litter on the forest floor. The nares are completely closed in adult gannets, frigatebirds, cormorants, and anhingas; a functional secondary nare is formed by a gap at the base of the bill, allowing these birds to breathe through their mouths with a closed bill (MacDonald 1960). Albatrosses, petrels, and other ocean‐living members of the Procellariiformes have nares encased in extended tubes. The function of the tubes is still under debate, but they may help in detecting the direction of odors; this order has the most developed sense of smell known in birds, and they use olfaction for finding food and for navigation to nesting islands (Chapter 7).

Fig. 6.24 Variation in naris anatomy. Some species have evolved nasal coverings to keep out debris, food, and water (depending on their ecology). (A) Ground‐feeding birds like this Rock Pigeon (Columba livia) have a protective skin flap called an operculum that extends partially over their nares, potentially to keep out debris. (B) Like most birds of prey, Saker Falcons (Falco cherrug) have ceres, protective skin over the maxilla, to protect the nares.

(Photographs by: A, Dori, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pigeon_portrait_4861.jpg. CC‐BY‐SA 3.0; B, Keven Law, Los Angeles, USA, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Saker_Falcon_profile_shot.jpg. CC‐BY‐SA 2.0.)

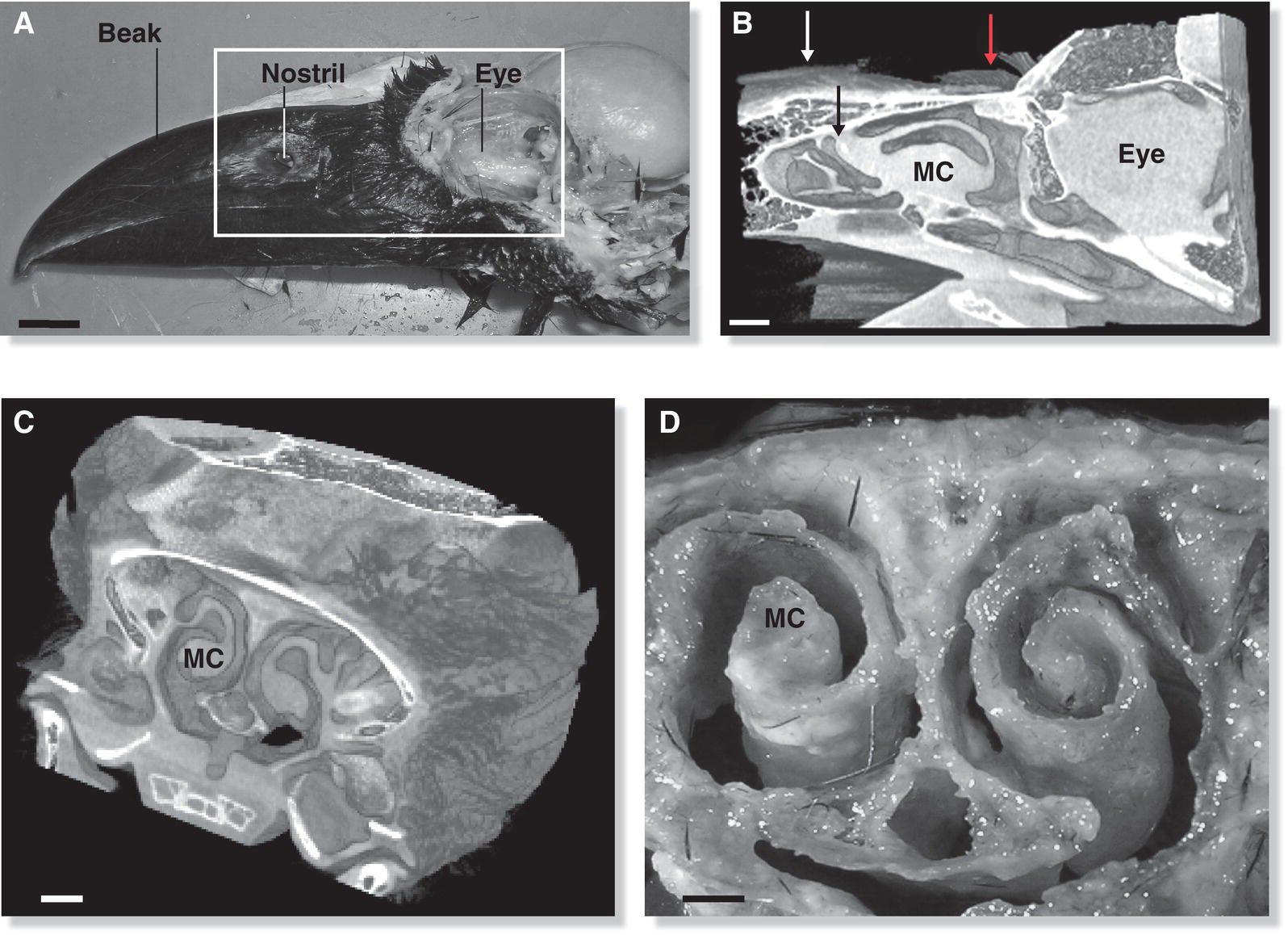

Internally, a medium septum usually divides the nasal cavity in half, although in many bird species the nares are completely open and daylight can be seen through the bill. The two nasal cavities lead back, opening into the roof of the mouth through a single slit, the choana (Fig. 6.25). A large infraorbital sinus, in communication with the nasal cavity and an air sac behind the skull, is usually present on each side beneath the eye. Each cavity filters inhaled air via mucus and small hair‐like structures called cilia. Vascularized, scroll‐like projections called conchae (Fig. 6.26) occur within each nasal cavity as well and are covered by a mucous membrane. Embedded with olfactory neurons, this membrane allows the bird to smell when air passes over the conchae.

Fig. 6.25 The choana. The choana is a single slit on the roof of the mouth that, when open, allows air to enter through the nares, and when closed, seals the oral cavity. This schematic depicts the choana in a Budgerigar (Melopsittacus undulatus), with the infraorbital sinus situated posterior to the choana, and the pharynx (where digestive and respiratory functions meet) below.

(Adapted from Evans 1996. Reproduced with permission from Howard E. Evans.)

Fig. 6.26 Nasal conchae. (A) The boxed area on this head of a Large‐billed Crow (Corvus macrorhynchos) is depicted in (B) a CT scan of the nasal region, including the large maxillary conchae (MC) inside the nares. (C) A CT scan of the skull also reveals these scroll‐like MC pairs. (D) A cross‐section shows the conchae structure; the nasal septum (st) bisects highly vascularized tissue that enables a bird to smell. Scale bars A–C = 10 mm, D = 1 mm.

(From Yokosuka et al. 2009. Reproduced with permission from Oxford University Press.)

A duct from the salt gland, located in a shallow depression (fossa) above or within the eye socket, extends onto the sides of both nasal cavities. This gland, which is largest in marine birds, helps expel excess salt from the body. Albatrosses and other “tubenoses” excrete large amounts of excess salt in a fluid that travels into the nasal cavities, out the nostrils, and into grooves that extend to the bill tip. Salty fluid then drips away or evaporates far from the nostrils, reducing the possibility of residual salt clogging the entrances, perhaps because these birds rely so heavily on their sense of smell (Chapter 7).

6.3.2 Pharynx

The pharynx begins at the back of the tongue. Here, the pathways for food and air cross (Fig. 6.27A). Folds on the roof of the pharynx surround the openings to the nasal cavities and auditory tubes. From the middle ear cavity, the auditory tube enters the pharynx on the midline of the palate and allows air pressure to be balanced on both sides of the tympanic membrane. In the floor of the pharynx, laryngeal folds border the glottis, the entrance to the trachea. The entrance to the esophagus is behind the glottis.

Fig. 6.27 Passageways into the throat. The avian pharynx is a dual passage for air and sustenance. (A) Nasal passageways bring air into the oral cavity (solid arrows), while food enters through the mouth and proceeds back to the esophagus (dashed arrows). In the floor of the pharynx, the slit‐like glottis (shaded area) serves as the entrance to the larynx and trachea. (B) The larynx, a valve that allows air into the trachea, is composed of cartilaginous rings.

(A, adapted from Evans 1996. Reproduced with permission from Howard E. Evans. B, adapted from Bock 1978. Reproduced with permission from Wilson Ornithological Society.)

6.3.3 Larynx

Situated above the trachea, a bird’s larynx (Fig. 6.27B) does not contain vocal chords as it does in mammals. Rather than producing sound, its primary function is to serve as a valve, regulating the flow of air into the trachea. The slit‐like glottis, or opening to the larynx, is behind the tongue, formed by two pieces of cartilage covered with a mucous membrane.

6.3.4 Trachea and syrinx

The trachea, or windpipe, is a tube that conducts air from the glottis of the larynx into the lungs and air sacs. A series of cartilaginous rings holds the trachea open for the passage of air. These rings telescope into or away from one another when a bird bends, extends, or shortens its neck. In most birds, the trachea follows a straight course from the glottis to the forking of the bronchi.

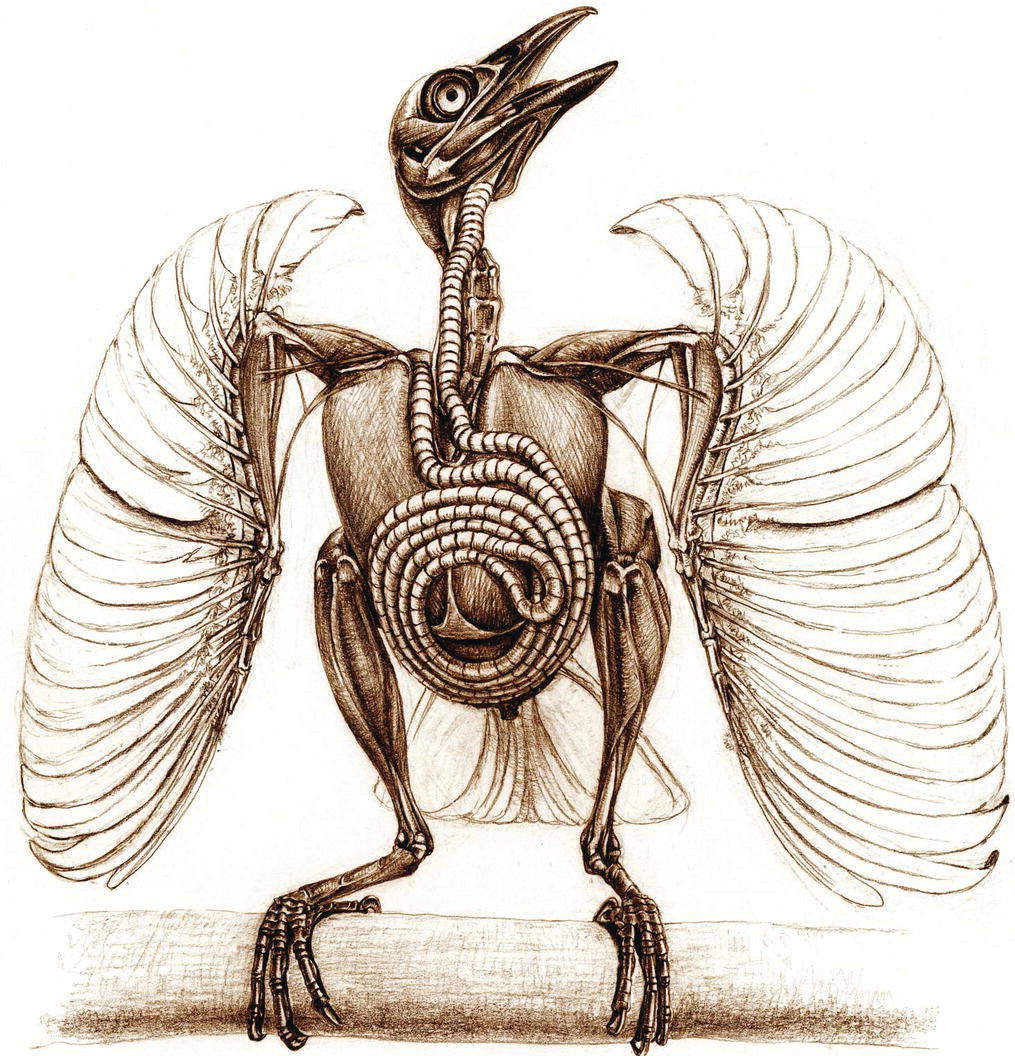

Some birds have unusually long trachea, an enhancement that may improve the resonance of their calls. In North America, the tracheas of the Trumpeter Swan (Cygnus buccinator), Tundra Swan (Cygnus columbianus), and Whooping Crane (Grus americana) enter the carina of the sternum and pass caudally within it before looping back to their point of entry, where they make another bend to enter the thoracic inlet. A few passerines, such as the Trumpet Manucode (Phonygammus keraudrenii) of Australia and New Guinea, have coiled tracheas (Fig. 6.28). Emus (Dromaius novaehollandiae) have several open tracheal rings that allow air to exit into a sac beneath the skin on the lower portion of the neck. Many ducks have a trachea expansion (bulb or bulla) on one side at the lower end just before the syrinx. These specializations modify the sounds produced.

Fig. 6.28 Coiled trachea. The Trumpet Manucode (Phonygammus keraudrenii) has an exceedingly long and coiled trachea, an adaptation that enhances the resonance of its call.

(From van Grouw 2013. Reproduced with permission from Princeton University Press.)

The syrinx is the vocal sound‐producing organ in birds (Chapter 10). A cartilaginous expansion covered by muscles, the syrinx lies at the lower end of the trachea where it branches into two bronchi before entering the lungs. The syrinx is formed by modifications of tracheal rings, bronchial half‐rings, or a combination of both. Thus birds can have a tracheal syrinx (Fig. 6.29A), separate bronchial syrinxes as in the cave‐dwelling Oilbird (Steatornis caripensis) of northern South America (Fig. 6.29B), or, most commonly, a tracheobronchial syrinx (Fig. 6.29C).

Fig. 6.29 Anatomy of the syrinx in three different birds. The syrinx is located at the lower end of the trachea, above the bronchial entrances. (A) Birds can have a tracheal syrinx, as in parrots; (B) separate bronchial syrinxes, as in the Oilbird (Steatornis caripensis); or (C) a tracheobronchial syrinx, as in the domesticated Island Canary (Serinus canaria) and many other birds. (Adapted from Suthers 2004. Based on illustrations in King and McLelland 1989, Suthers and Hector 1985, and Nottebohm and Nottebohm 1976. )

Reproduced with permission from Elsevier.

In the avian syrinx, highly elastic tympanic membranes stretched between specialized syringeal cartilages and muscles vibrate to produce sound waves when air is forced past them. The syringeal muscles produce the different sounds within a bird’s song or call by changing the tension of the membranes and the diameter of the constricted passage in the syrinx. An increase in the frequency of vibrations raises the pitch; an increase in the diameter of the passageway increases the volume.

Some species can control the two sides of the syrinx independently, allowing them to produce two different sounds at once (Chapter 12). Songbirds have an extremely complicated syrinx. In addition to complex muscle arrangements, songbirds have additional syringeal structures: a median cartilage called the pessulus at the bifurcation of the bronchi and a semilunar membrane extending from the pessulus into the cavity of the syrinx.

6.3.5 Lungs

In simple terms, bird lungs are masses of interconnecting air tubes (Fig. 6.30). Two small, non‐inflatable lungs lie in contact with the vertebral column and ribs. The trachea splits into two bronchi; as each bronchus enters its respective lung, the half‐rings of cartilage disappear. Each continues as the primary bronchus or mesobronchus through the lung, gradually decreases in diameter, and ends at the entrance to the abdominal air sac. Many secondary bronchi branch off the mesobronchus and pass into the lung. Most of these secondary bronchi branch again to form parabronchi, which are the major respiratory units of the lung. Air moves to the ventrobronchi after passing through the parabronchi.

Fig. 6.30 Anatomy of the avian lung. Bird lungs are non‐inflatable and relatively stiff. The trachea splits into dual bronchi on opposite sides of the bird. Primary bronchi shrink in diameter as secondary bronchi branch off in numerous locations before passing into the lung. Small and abundant, secondary bronchi branch further into parabronchi, the main respiratory unit of the lungs.

(Top, illustration of a cast of these air spaces, courtesy of Howard E. Evans. Bottom, adapted from Proctor and Lynch 1993. Reproduced with permission from Yale University Press.)

The parabronchi are tightly packed, thick‐walled tubes; parabronchial walls contain hundreds of air vesicles within the tissue, sometimes called air capillaries, which intertwine with a network of blood capillaries (Fig. 6.31). These stem from the numerous pulmonary arteries and veins that are also embedded in the parabronchial walls. As blood flows through the capillaries—supplied by the pulmonary artery and drained by the pulmonary vein—oxygen and carbon dioxide are exchanged via the surrounding air vesicles. In mammals, this respiratory exchange takes place in dead‐end alveoli at the termination of bronchioles, which do not exist in birds.

Fig. 6.31 Function of parabronchi. (A) Parabronchi supply fresh oxygen via air vesicles (capillaries) for the air exchange that occurs in capillary networks that run through the lungs. (B) After carbon dioxide is exchanged for oxygen within the air capillaries, it is transported into the arterioles. Deoxygenated blood flows back out through the pulmonary venules.

(A, adapted from Brooke and Birkhead 1991. Reproduced with permission from Cambridge University Press. B, © Cornell Lab of Ornithology.)

Rather than a diaphragm, birds use their hinged thoracic cage and extensive system of air sacs (Fig. 6.32)—with flexible walls as thin as soap bubbles—to force air in and out of their stiff lungs. These air sacs do not contain blood vessels and play no part in the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide. Instead, they expand and contract to facilitate airflow and serve as holding chambers for air before it passes through the bronchi and into the parabronchi of the lung.

Fig. 6.32 Anatomy of air sacs. This diagram of a Budgerigar (Melopsittacus undulatus) depicts the arrangement of the lungs and major air sacs in relation to the air passageways that connect them.

(Adapted from Evans 1996. Reproduced with permission from Howard E. Evans.)

Most birds have nine air sacs. At the thoracic inlet, the clavicular air sac surrounds the branching point of the trachea. In addition to a large central sac, the clavicular air sac also consists of smaller extensions that connect to the air spaces within the coracoid, cervical vertebrae, humerus, and sternum. Cervical air sacs connect to the cervical vertebrae as well. Two thoracic air sacs surround the lung in a fixed position; two abdominal air sacs sit adjacent to the posterior thoracic air sacs and can shift their position within the abdominal cavity. Although the pairing is difficult to illustrate, each of these air sacs (with the exception of the clavicular and sometimes the cervical air sac) occur on both sides of a bird’s body.

As a bird inhales, air passes through the trachea and down through the mesobronchus (Fig. 6.33). Half of the incoming air moves to the lungs while the other half is stored directly in the caudal air sacs. At the same time, deoxygenated air moves from the lungs into the cranial sacs. Upon exhalation, air from the lungs and the cranial air sacs moves out via the trachea while fresh air stored in the caudal air sacs moves into the lungs. This system allows birds to receive fresh, oxygenated air during inhalation and exhalation—which means that oxygen and carbon dioxide are exchanged continuously via the blood and air capillaries. Air flows through the lungs in one direction only; air is not “mixed” with higher and lower levels of oxygen, as in mammals. This mechanism allows more oxygen to reach the blood, which in turn facilitates a higher metabolic rate, as well as the ability to fly at higher altitudes with less oxygen (Chapter 7). The practice leading to the expression “canary in a coalmine” is a tribute to the efficiency of the avian respiratory system. Well into the 20th century, workers would bring caged canaries into coalmines to test for carbon monoxide; since the birds breathed in the poison while exhaling as well as inhaling, they would react faster than the human miners, allowing the workers to escape before it was too late (Chapter 15).

Fig. 6.33 Airflow through the air sacs. Air sacs connect the primary bronchial passages to each lung and hold air as it flows through the air passageways and out again. From start to finish, a single packet of air would take two cycles of breath to leave the body. (A) In the first inhalation, air (yellow) enters the passageways. Expanding air sacs pull the air in, which opens passageways into the posterior thoracic and abdominal air sacs. (B) As the bird exhales, the air sacs contract, pushing the same air (yellow) into open parabronchial spaces not closed off by valves (circles around air passageways). (C) In the second inhalation, new air (blue) is pulled into the expanding thoracic and abdominal air sacs while air from the first inspiration (yellow)—still in the parabronchi—travels into the intraclavicular and cranial thoracic sacs. (D) The second exhalation pushes the old air (yellow) out of the mouth of the bird as new air (blue) is simultaneously drawn back into the posterior thoracic sacs and the process repeats.

(Courtesy of John Ludders and Michael Simmons, Cornell University.)

6.4 Digestive system

Digestion involves the ingestion of food, the uptake of nutrients, and the elimination of wastes. Birds do not chew their food. The act of swallowing involves grasping (and sometimes crushing) food with the bill, manipulating it with the tongue, and passing it into the alimentary canal (Fig. 6.34).

Fig. 6.34 Avian alimentary canal. This diagram shows the alimentary canal of a Budgerigar (Melopsittacus undulatus) in relation to its skeleton. As food enters the esophagus, it is pushed by muscular action to the crop, a pouch‐like extension of the esophagus where food is stored and softened. From there, food travels to the proventriculus and gizzard—the two parts of the avian stomach—then though the small and large intestine, and finally exits through the cloaca via the vent.

(Adapted from Evans 1996. Reproduced with permission from Howard E. Evans.)

6.4.1 Tongue

Although most of a bird’s taste buds do not occur on the tongue, the tongue does facilitate taste, and some birds also use their tongue to detect texture and temperature. However, birds mainly use their tongues to secure, manipulate, and swallow food.

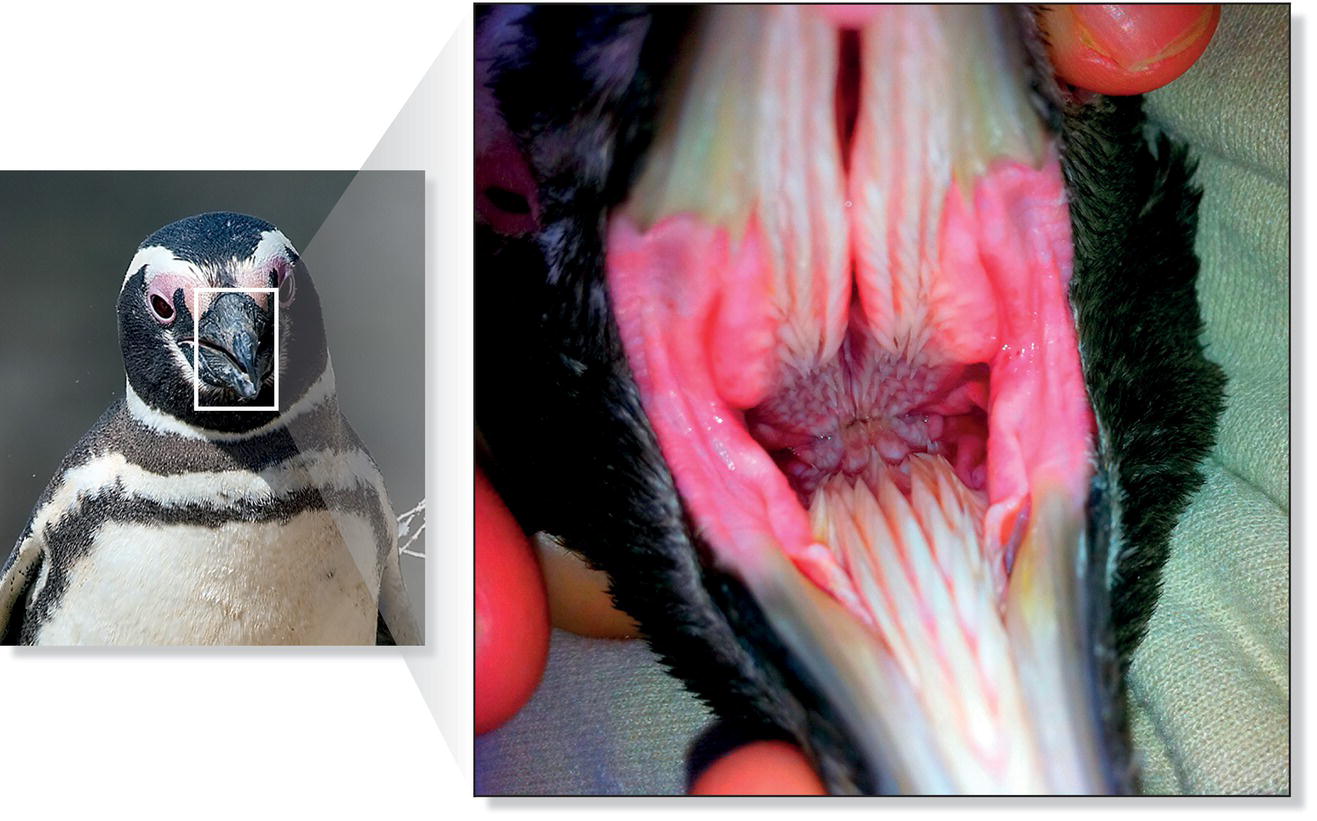

Bird tongues assume many forms. Rectangular, cylindrical, lance‐like, flat, cupped, grooved, spoon‐shaped, or forked tongues—often enhanced with specialized spines or hair‐like structures—function as probes, brushes, sieves, or coarse files. Like the bill, the structure of the tongue corresponds to feeding specialty (Chapter 8). For example, penguin tongues have sturdy spines to force fish, which often vigorously wiggle to escape capture, into the esophagus (Fig. 6.35). Hummingbirds tend to have forked tongues with folded edges—this configuration creates small troughs that channel nectar from flowers into the mouth. Many bird tongues also have horny, spiny, fleshy, or brush‐like tips. When woodpeckers project their tongues into a bark crevice or an excavation, the backward‐projecting barbs at the tips help snag insects and insect larvae. The tongues and hyoid bones of woodpeckers and hummingbirds are so long that they curve around the skull, in some cases reaching the nostrils. The shorter tongues of sapsuckers are equipped with forward‐projecting, hair‐like structures to collect sap. Since pelicans, gannets, ibises, spoonbills, storks, and some kingfishers swallow their food whole, their tongues are very small.

Fig. 6.35 Tongue and mouth of a penguin. Magellanic Penguins (Spheniscus magellanicus) have evolved a specialized posterior‐facing mouth and tongue barbs, which aid in the capture of slippery prey.

(Photographs by: left, David, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Magellanic_penguin,_Valdes_Peninsula,_e.jpg. CC‐BY‐2.0; right, Anthony Brown.)

Salivary glands secrete saliva to moisten food in the mouth. The presence of salivary glands in a bird is generally correlated with the kinds of food it eats. Species that eat seeds, plants, and insects have well‐developed salivary glands. Birds that obtain their food from the water have little need to moisten it; thus, birds such as the Anhinga (Anhinga anhinga) do not have salivary glands.

Some groups of birds have specialized saliva. The Chimney Swift (Chaetura pelagica) of eastern North America, the Common Swift (Apus apus) of Europe and southern Africa, and the Glossy Swiftlet (Collocalia esculenta) of the western Pacific and Asia use their saliva as an adhesive, firmly securing their nests to walls (Chapter 11). The salivary glands of woodpeckers secrete a special sticky fluid onto the tongue, which allows them to extract insects—which stick to the tongue—from deep burrows.

6.4.2 Alimentary canal

The alimentary canal begins with the esophagus, a relatively straight and thin muscular tube. Most birds can temporarily expand their esophagus to hold large quantities of food. Some gulls, for example, are capable of holding one end of a large fish in the esophagus while digesting the other end in the stomach. Avian esophageal walls contain mucus‐secreting glands that moisten incoming food.

Muscular pouches called diverticula serve various roles within the esophagus of most birds. Redpolls and other finches use them to store seeds. Other outpockets serve as resonance chambers for sound signals in courtship displays, as in pigeons. Grouse and prairie‐chickens have esophageal air sacs that externally inflate to produce both auditory and visual signals as part of a display for females. These sacs, generally covered with brightly colored skin, emit loud sounds when air vibrates within them (Fig. 6.36). Pigeons, doves, gallinaceous birds, and some passerines have a permanent dilatation of the lower esophagus called the crop (Fig. 6.34). This special area allows a bird to consume food quickly and then move to safety, as it serves as a holding chamber until the bird is ready to pass it to the stomach or regurgitate the food to its young. In some birds—such as pigeons, flamingos, and some penguins—a sloughing of cells from the crop lining produces “crop milk,” a lipid‐rich material that the parent regurgitates to feed its young. A thin muscle over the surface of the crop aids in the swallowing of food.

Fig. 6.36 Esophageal air sacs as sexual signals. This male Greater Sage‐Grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus) inflates its bizarre skin sacs—outpockets of the esophagus—to produce auditory and visual displays for females, which assess male quality based on his performance in the lek.

(Photograph by Gerrit Vyn.)

The Hoatzin (Opisthocomus hoazin), a pheasant‐sized bird from the Amazon, has an exceptionally large, thick‐walled crop (Fig. 6.37). It is the only bird that digests food within its crop and lower esophagus instead of its stomach. The Hoatzin eats food that is uncharacteristically fibrous for a bird, as 85% of its diet is thick leaves. Like many other foregut‐fermenting herbivores (such as cows), the Hoatzin retains food in its foregut where it is digested by microbes. Microbial digestion enhances the detoxification of plant defenses, production of amino acids, and extraction of nutrients. While most birds only require 1 or 2 hours for digestion in the stomach, microbial digestion in the crop requires about 20 hours. Since plant tissue breaks down within the Hoatzin’s specialized crop, its stomach is much smaller.

Fig. 6.37 Anatomy of the Hoatzin (Opisthocomus hoazin) digestive system. This strictly herbivorous bird digests food in its exceptionally large, thick‐walled crop rather than its stomach, which is greatly reduced. Its diet of thick leaves can require 20 hours of microbial digestion.

(Adapted from Grajal 1995. Reproduced with permission from American Orthithologists’ Union. Photograph by Morten Ross.)

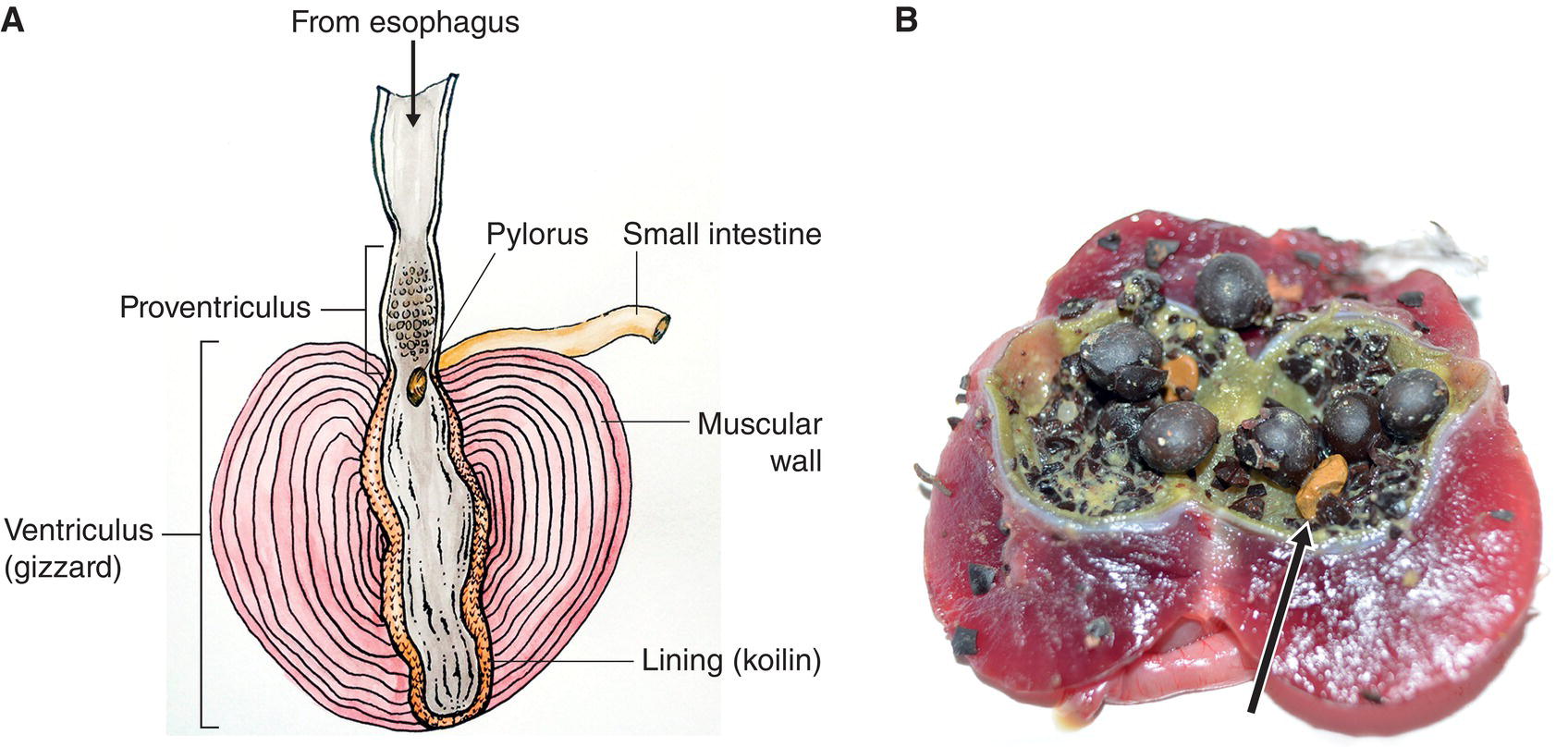

All birds have a two‐part stomach. The elongated first portion is called the proventriculus; its gastric glands secrete digestive enzymes, including pepsin and hydrochloric acid, which break down the proteins in food. A few types of birds (including petrels, cormorants, herons, gulls, terns, some hawks, and some woodpeckers) can expand the proventriculus to hold food temporarily for later feeding, either for themselves or their young. The ventriculus, or gizzard, is the second part of the avian stomach. The gizzard grinds food by contracting its thick muscular walls. Seed‐eating birds with well‐developed gizzards, such as grouse and turkeys, ingest pebbles and gravel to augment this grinding process (Fig. 6.38). Glands within the gizzard secrete a protective, leathery lining called gastric cuticle or koilin, a mixture of carbohydrates and proteins. Since koilin is constantly worn away by the grinding action of the walls, its secretion is continuous.

Fig. 6.38 Granivore gizzards. (A) The alimentary canal of a domestic turkey has well‐developed muscular walls around the ventriculus (gizzard), which is lined with koilin. The pylorus leads into the small intestine. (B) This cross‐section of a White‐winged Dove (Zenaida asiatica) gizzard reveals the contents of its last meal: hard, waxy seeds and some bright yellow rocks (arrow) that were ingested to help crush the seeds. The white lining is the koilin and the lime green is the muscle wall interior.

(A, © Cornell Lab of Ornithology. B, photograph by Jace G. Stansbury.)

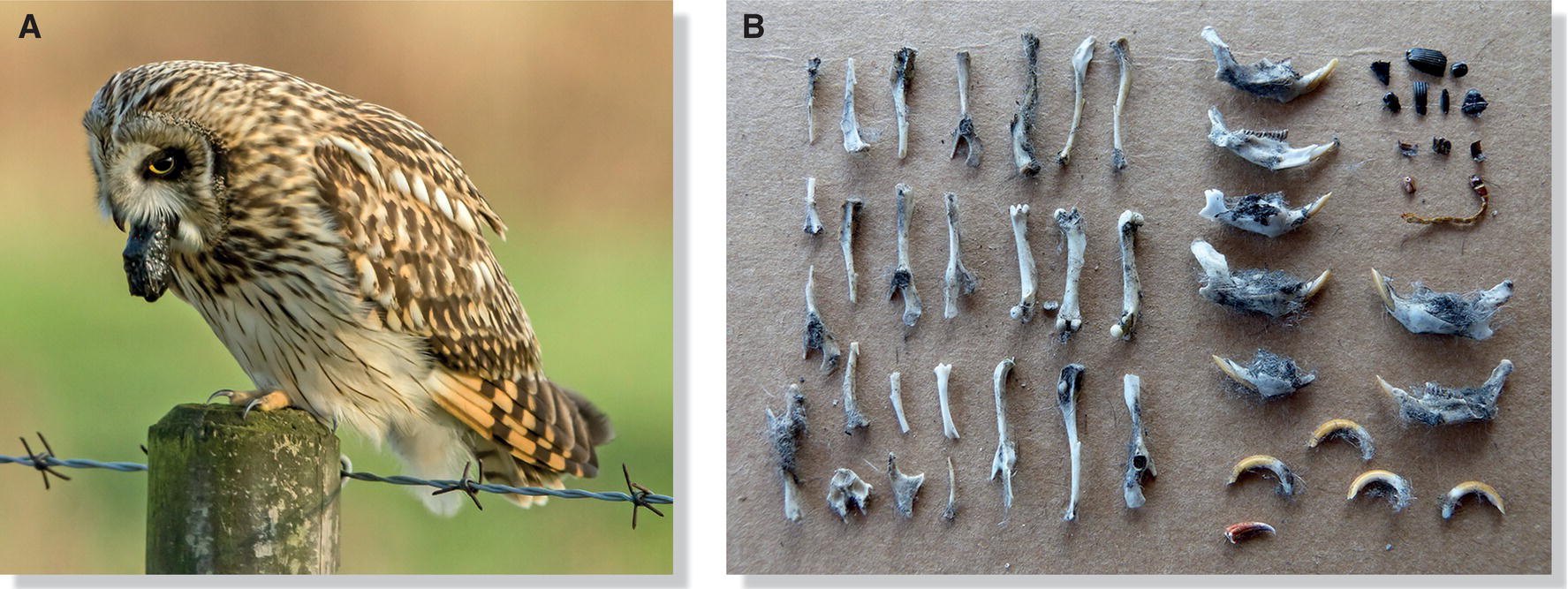

After a carnivorous bird swallows a prey item, the indigestible parts (such as bones, teeth, feathers, fur, and exoskeletons of some insects) form a pellet within the gizzard. The bird may regurgitate the pellet hours later, after digesting the flesh. Pellet formation is characteristic of owls, hawks, grouse, nightjars, swifts, and many passerines (Fig. 6.39). Grebes are thought to swallow their own feathers to slow the rate of digestion and protect the stomach from sharp fish bones. After the stomach acid dissolves the bones, grebes regurgitate pellets that consist mainly of feathers and indigestible plants.

Fig. 6.39 Indigestible remains. Many carnivorous and insectivorous birds cannot digest the hard parts of their prey since their proventriculus is small and lacks muscular walls. (A) Thus, they must regurgitate pellets, as demonstrated by this Short‐eared Owl (Asio flammeus). (B) Skeletal remains of small mammals within these pellets reveal the identity of the owl’s principal prey species.

(Photographs by: A, David Newby; B, Adam Tilt.)

The final processes of digestion take place in the small intestine—named for its small diameter, not length. The inner surface of the small intestine has longitudinal folds and minute finger‐like projections in carnivores, and flattened leaf‐like structures in many birds that eat seeds and other parts of plants. It consists of three externally indistinguishable parts: the duodenum, the jejunum, and the ileum (Fig. 6.40). Most nutrients absorb through the intestinal wall lining and into the blood stream, while metabolized fat passes into the lymphatic system—the network of vessels through which white blood cells drain from tissues into the blood (Box 6.03).

Fig. 6.40 Posterior digestive anatomy. The primary parts of the digestive system include the major arteries and veins, liver and associated ducts, small intestine (duodenum, jejunum, ileum), pancreas (and ducts), cecae, large intestine (relatively small in most birds), cloaca, ureters, and vent.

(Adapted from Proctor and Lynch 1993. Reproduced with permission from Yale University Press.)

The small intestine is the longest part of the digestive tract in every bird except the Ostrich (Struthio camelus). Typically, birds that eat foods that are difficult to digest or that are low in nutritional value have longer digestive tracts. For example, the Dusky Grouse (Dendragapus obscurus) and the Spruce Grouse (Falcipennis canadensis) of western North America mainly feed on low‐nutrient conifer needles; their small intestines are therefore about 28% longer than similarly sized birds with a more nutrient‐rich diet. This phenomenon can even occur within the same species, as in the California Quail (Callipepla californica). The small intestines of quail that live along the humid coast of northern California are about 11% longer than those of quail inhabiting the arid interior, since the former eat considerably more green food (Leopold 1953).

Within the intestinal walls, small glands secrete fluids to aid in digestion. Bile, an alkaline fluid secreted by the liver, splits fats into tiny particles and neutralizes the acid passing into the intestine from the stomach. Several bile ducts from the liver and gall bladder drain into the duodenum, the first U‐shaped loop of the small intestine (Fig. 6.40). The duodenum is very similar in all birds, beginning at a circular band of muscle called the pylorus. The pancreas, which secretes insulin, glucagon, and various digestive enzymes to break down proteins and fat, is situated within the duodenal loop. The remainder of the small intestine continues to loop and coil as the jejunum and later the ileum. A remnant of the yolk sac—a small pouch called the vitelline diverticulum—occurs at the junction of the two.

Long pouches called colic cecae (singular, cecum) mark the end of the ileum and the beginning of the large intestine (Fig. 6.40). Often paired, they hold material for bacterial digestion, eventually refluxing the contents into the large intestine. Herons and bitterns have a single cecum, while the Secretary‐bird (Sagittarius serpentarius) has two pairs; cecae are absent or barely present in anhingas, parrots, pigeons, kingfishers, swifts, woodpeckers, and some hummingbirds. Diet plays a large role in this variation: herbivorous birds tend to have longer cecae than their seed‐eating relatives, probably to enhance breakdown of the cellulose in tough plant fibers.

In most birds, the large intestine is a short, straight tube extending from the colic cecae to the cloaca. After reabsorbing the remaining water, the large intestine passes waste contents to the cloaca, which also receives semisolid uric acid from the kidneys and eggs from the ovary (Chapter 7).

The liver processes digestive products into useful substances for the body, neutralizes harmful substances in the blood, and produces bile to aid in digestion. The largest internal organ of the avian body, the liver, has two lobes; usually the right lobe is larger than the left (Fig. 6.40). Several bile ducts lead directly into the duodenum from each lobe. Many birds have a gall bladder, which serves as a reservoir for the storage and concentration of bile; depending on the species, the gall bladder may be oval, sac'like, or long and tubular. Other birds—such as parrots, cuckoos, hummingbirds, pigeons, and some woodpeckers, falcons, and passerines—lack a gall bladder altogether.

6.5 Urogenital system

The urinary and reproductive systems function together as the avian urogenital system (Fig. 6.41). The urinary system, which removes toxic nitrogenous wastes from circulation, develops first. In young birds, the cloacal bursa opens into the roof of the cloaca and produces B cells that populate lymphatic tissues (Chapter 7).

Fig. 6.41 Avian urogenital system. Since the urinary and reproductive systems function together in birds, the major components include the gonads, kidneys, ureters, and cloaca. Although their urogenital anatomies are similar, (A) males have testes and an ejaculatory duct, and (B) females have an ovary and oviduct.

(Adapted from Evans 1996. Reproduced with permission from Howard E. Evans.)

Unlike other systems in the bird’s body, the reproductive system is active only part of the year in many bird species. The gonads of seasonally breeding birds shrink after breeding; for example, the testes of the European Starling (Sturnus vulgaris) decrease in length from 19 millimeters during breeding to 2.5 millimeters in winter (a change in volume of over 1000×) (Bissonnette and Chapnick 1930). Gonads enlarge in resident seasonal breeders as well; testes in Spotted Antbirds (Hylophylax naevioides) grew to a maximum of 3 × 5 millimeters while breeding, compared to a minimum of 0.8 × 0.8 millimeters during other times (Wikelski et al. 2000).

Ovary size and condition vary during the breeding season even more dramatically than do testes. The ability to lay eggs facilitates efficient flight, eliminating the need for females to carry young while they develop. Female birds develop and lay eggs one at a time, and most develop only a left ovary, possibly another weight‐saving adaptation.

6.5.1 Excretory organs and ducts

The avian urinary system, sometimes called the excretory system, includes a pair of kidneys and their excretory ducts (Chapter 7). The kidneys control fluid and ion levels while removing nitrogenous waste products from the blood.

With the exception of the South American rheas, birds do not have urinary bladders. The liver produces uric acid rather than urea. Uric acid is more concentrated and is not as water soluble; the kidneys reabsorb most of the water before the toxic waste is excreted. The excretory ducts, called ureters, conduct a thick white slurry of uric acid to the cloaca, where it either mixes with or surrounds the feces. Reflux of urine into the lower part of the digestive tract allows reabsorption of water.

6.5.2 Male and female gonads

Male gonads are termed testes. Oval or elliptical in shape, avian testes are paired and lie within the body cavity at the anterior end of each kidney (Fig. 6.41A). Generally, testes produce one of two sperm cell types, depending on the species: a short, simple type in non‐passerine orders, and a longer, spiral‐shaped type in passerines (Fig. 6.42A). With the approach of the breeding season, avian testes increase greatly in size. Deferent ducts carry sperm from the testes to the cloaca. The configuration of each duct creates the illusion of striations. In most birds, a spindle‐shaped terminal swelling at the end of each duct, called the ampulla, opens as a papilla into the cloaca. When the male everts its cloaca during copulation, this papilla enters the female cloaca and may even contact the opening of the oviduct. During the breeding season, the cloacal region of male passerines swells so much that the protuberance serves as an indicator of a bird’s breeding condition (and by proxy, its sex) (Fig. 6.42B).

Fig. 6.42 Sperm and male cloacal swelling. (A) Passerines and non‐passerines generally have different sperm types. Compare the spiral‐shaped sperm of the European Greenfinch (Chloris chloris) (above) with the shorter, simpler domestic chicken (Gallus gallus) sperm (below). (B) Checking the cloacal protuberance size in a male passerine involves lightly blowing away the lower abdominal feathers and measuring the girth and length of the swelling with calipers. Reproductively receptive males have much larger cloacal protuberances during the breeding season.

(Illustrations by: A, Christi Sobel © Cornell Lab of Ornithology; B, N. John Schmitt.)

The female gonad, or ovary (Fig. 6.41B), contains many ova. In this context, the term “egg” is confusing, as it may refer to the female reproductive cell in general or the shelled version of the same cell after it has passed through the reproductive tract. To avoid confusion, in this chapter we use the term “ovum” (plural ova) while these cells are still within the female ovary, versus “egg” after it has been laid. Most female birds only have one functional ovary, the left. During ovulation, an ovum breaks out of the ovary and into the abdominal cavity (Fig. 6.43).

Fig. 6.43 Ovulation and the passage of an ovum through the reproductive tract. Most female birds only have one functional ovary. To initiate ovulation, the infundibulum temporarily opens to permit the entry of an ovum. From there, it travels to the magnum, where albumen (egg white) is secreted around the yolky ovum. In the isthmus, more watery albumen and shell membranes are deposited. The shell forms as the ovum passes through a short isthmus and into the uterus, where the shell and pigments are added. The ovum then typically rotates 180 degrees in the vagina to be laid with the blunt end first, via the cloaca.

(© Cornell Lab of Ornithology.)

Suspended from the dorsal body wall by a ligament, the oviduct begins as a flattened, funnel‐shaped opening called the infundibulum. The infundibulum then “swallows” the ovum. After entering the infundibulum, a long glandular region called the magnum secretes albumen (protein‐rich egg white), which protects the ovum and eventually serves as the embryo’s water supply. The shell membranes form as the ovum passes through a short isthmus. The ovum then travels to the well‐vascularized uterus, or shell gland. Here, secretory papillae deposit mineral calcium, which forms the shell. Depending on the bird, this gland may secrete pigments as well. An ovum typically spends most of its time (18–20 hours) in the shell gland. In the last portion of the oviduct, most birds rotate the ovum 180 degrees before passing it blunt‐end‐first into the cloaca.

6.5.3 Copulation and fertilization

Insemination occurs when male sperm enter a female’s cloaca. In this process, the male bird usually stands on the female’s back while both birds evert their cloacas and press them together. Sperm is transferred when the papilla of the male deferent duct contacts the lining of the female cloaca or, in some cases, enters the opening of her oviduct. Often referred to as a “cloacal kiss,” this contact between a mating pair is brief.

Ostriches, rheas, tinamous, ducks, and geese have a more advanced copulatory organ, the cloacal phallus (Fig. 6.44). Although often called a “penis,” this structure differs from the mammalian equivalent: since it lacks an internal urethra, sperm must travel along the external surface of the phallus.

Fig. 6.44 Cloacal phallus. A few bird species have a cloacal phallus, an adaptation that mitigates morphological or ecological situations that make mounting and copulation difficult (such as mating in water). Some ducks have unusually long cloacal phalluses; this Lake Duck (Oxyura vittata) holds the record for the longest avian phallus at 42.5 cm.

(From McCracken et al. 2001. Reproduced with permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd.)

Since many female birds store sperm in tubules located within the oviduct, sperm generally survive longer within birds than in mammals (Chapter 7). Sperm are likely released from these tubules following the passage of an ovum. A female turkey may lay as many as 15 fertile eggs following a single insemination; even after 30 days, 83% of her eggs may be fertile. In contrast, species that lay a single egg each season, such as the Eurasian Griffon (Gyps fulvus) of Europe and Africa, may copulate frequently for a month before laying (Margalida and Bertran 2010). An extended copulation period may provide more opportunities for sperm competition (Chapter 3), pair bonding, and/or paternity assurance (Chapter 9).

Sperm deposited into the female cloaca enter the oviduct and swim to the infundibulum, where fertilization takes place before albumen covers the ovum. The nuclei of the sperm cell and the ovum unite to form the zygote. Cell division proceeds as the fertilized ovum travels down the oviduct. After the female lays an egg, zygote growth ceases until incubation begins.

6.6 Circulatory system

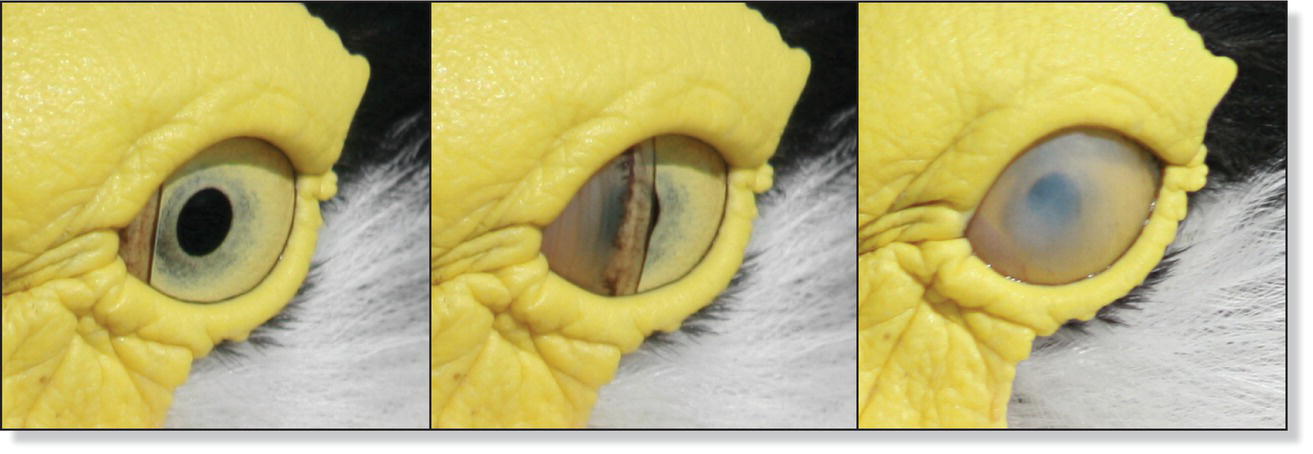

A vast network of organs and vessels, the circulatory system distributes oxygen and nutrients to cells throughout the body, removes waste products such as carbon dioxide, and distributes heat produced by muscles. It also circulates antibodies to prevent and fight infection as well as hormones produced by the endocrine glands. Blood facilitates this transport via the heart to pump it, arteries to distribute it, and veins to return it to the heart.