Chapter 9

Avian Mating and Social Behavior

John Alcock

Arizona State University

Opening image: A male Andean Cock‐of‐the‐rock (Rupicola peruvianus) displays in a sunspot. This species is known for its lekking behavior; the most beautifully plumed male with the most appealing display area secures the most matings.

(Photograph by Jason Rothmeyer.)

Imagine that it is springtime in central Arizona (USA), and you are watching a male and female Abert’s Towhee (Melozone aberti) in a suburban backyard (Fig. 9.01). With luck, you will see the female towhee exercising mate choice when she comes around to forage for seeds. She likely will arrive with a male companion by her side, because adult Abert’s Towhees often form long‐lasting social partnerships, and this pair is typical in that regard. The female appears practically attached to her partner as they hurry to the spot where scattered seeds await them. Once the birds have had their fill and have begun to hop toward the nearby shrubs, the female may stop and raise her long tail straight in the air. The male responds promptly to this signal by rushing to his partner and mounting her in a flurry of wing beats. After he succeeds in pressing his cloaca against hers for a few seconds, the mating is over. The two towhees then scurry off together under the shrubbery.

Fig. 9.01 A pair of Abert’s Towhees (Melozone aberti). This species often forms long‐lasting social partnerships.

(Photograph by John Alcock.)

This sequence of social behaviors, which is typical of many songbirds, illustrates the topics covered in this chapter. First, the female towhee clearly takes an active role in determining which male will fertilize her eggs. She does not merely accept the sexual advances of a partner passively, but instead signals her receptivity by elevating her tail, facilitating cloacal access for the male that she has selected as a partner. Abert’s Towhees are representative of birds in general in that females typically accept sperm only from particular males; such choices by females generate a host of questions, such as what are the attributes that females prefer in their mates, and what do they gain from their choices? These questions are at the heart of the first section of this chapter, which addresses the interrelated topics of behavioral mate choice and sexual selection.

Second, birds overall exhibit extremely diverse mating and social behaviors; these towhees provide an example of social monogamy, one of the most common avian mating systems. In Abert’s Towhees, one male associates closely with one female throughout an entire breeding season (if not longer) in a pair‐bond relationship that appears to restrict his reproductive options. Would a male be better off (that is, leave more surviving descendants) if he sought out several sexual partners in each breeding season? Males that fertilize the eggs of more than one female each spring would seem likely to pass on more of their genes than strictly monogamous males in the population. If so, monogamous tendencies in males would be eliminated over time in favor of a different mating system in which some males have several partners rather than only one at a time. This dilemma provides a starting point for the second section of the chapter, which explains why bird species range from purely monogamous to highly polygynous.

Third, these towhees also illustrate issues associated with social behavior in general. The birds clearly are social in the sense of remaining in each other’s company and interacting regularly. They cooperate in the defense of their territory, their private real estate from which they expel other Abert’s Towhees. Both members of this pair feed their young during the breeding season. Furthermore, they permit each other to feed freely on seeds offered to them, but frequently show aggression to the local House Sparrows (Passer domesticus) and other visitors that attempt to eat at the same bird table. What determines why the birds are cooperative in some contexts, but exhibit antisocial aggression in others? This question, along with other key puzzles linked to avian social behavior, is considered in the third and final part of the chapter.

9.1 Female mating preferences

Given what we know now about the sexual give‐and‐take between female and male birds, it is hard to believe that until the mid‐1900s, many biologists believed that females in general (even in our own species!) lacked preferences for particular attributes in their potential mates (Milam 2010). The standard view used to be that males controlled the mating game by competing among themselves for passive females. Charles Darwin, in contrast, argued that females of many bird species had what he termed “aesthetic sensibilities” that they employ when considering would‐be mates. Darwin knew that in pairs of birds where the sexes differed in traits such as singing ability, display dances, or the vividness of their plumage, the male would almost invariably be the sex with the greater capacity for song, the more bizarre courtship displays, and the more striking plumage. Darwin (1871) asked somewhat rhetorically whether “every male of the same species equally excite[s] and attract[s] the female? Or does she exert a choice, and prefer certain males?” He asserted that females do indeed have preferences for certain males.

In recent years, an explosion of research has demonstrated that Darwin was entirely correct in his observation that females are far from neutral bystanders when it comes to selecting mates (Jones and Ratterman 2009). Consider, for example, experiments that have shown how female Zebra Finches (Taeniopygia guttata) assess males via their songs (Woolley and Doupe 2008). When Zebra Finch males are singing in the presence of a female, they tend to produce songs that are faster and more standardized than the songs they sing when no females are nearby. By using two speakers to play back faster and slower songs, researchers can assess which of these variants the females prefer. It turns out that when female Zebra Finches are given this choice, they generally approach the speaker playing the faster song type, thereby demonstrating their preference for this kind of song. The underlying presumption of such an experiment is that under natural conditions, female Zebra Finches seeking mates would tend to approach and choose males able to sing the preferred song quality. This assumption also has been tested in experiments with captive finches: females given a choice between two caged males gave more raised‐tail copulation‐solicitation displays to the individual they visited more often (Witte 2006). In other words, a female’s association preference reveals her sexual preference as well.

Many other experiments on how females respond to the sexual signals of males have shown that females often pay close attention to even subtle differences in male behaviors or other traits. Male vocalizations (Chapter 10) frequently are a component of the sexual displays that female birds use to assess their mates. For example, female Swamp Sparrows (Melospiza georgiana) in eastern North America are attracted to unusually fast trilling songs (Ballentine et al. 2004), whereas female European Serins (Serinus serinus), a small Eurasian finch, prefer songs that incorporate notes of exceptionally high frequency (Cardoso et al. 2007). The speed of sound production correlates with male mating success in the Magnificent Frigatebird (Fregata magnificens) of the tropical Atlantic, a species in which males attract females by generating a drumming sound via bill clacking that then resonates into an inflated, bright red gular pouch, which itself is a sexual signal (Madsen et al. 2007) (Fig. 9.02). In the Brown Skua (Stercorarius antarcticus) of Antarctica, males try to produce calls with many notes per second while also generating notes over a relatively broad range of sound frequencies; it is particularly difficult to do both things at once, and the males best able to call near the upper limits of this performance trade‐off have higher reproductive success than their less adept rivals (Janicke et al. 2007). These and other cases outlined in Chapter 10 illustrate the general rule that female birds prefer vocal performances that are challenging to produce.

Fig. 9.02 Displaying male Magnificent Frigatebird (Fregata magnificens). Males of this species use both visual (inflated red pouch) and auditory signals (calling and bill clacking) to compete for access to reproductively active females.

(Photograph by Gerrit Vyn.)

Although male song in general is a very common sexual signal in many groups of birds, the precise song traits preferred by females vary widely from species to species: some female birds assess males on the basis of their speed of signal production, others by the presence of favored sound frequencies. Still others prefer male vocalizations with a wide frequency range or a large total number of song types in a male’s repertoire. None of these song attributes is favored universally across all birds. More remains to be learned about how a particular kind of signal preference by females of a given species translates into reproductive benefits for those females.

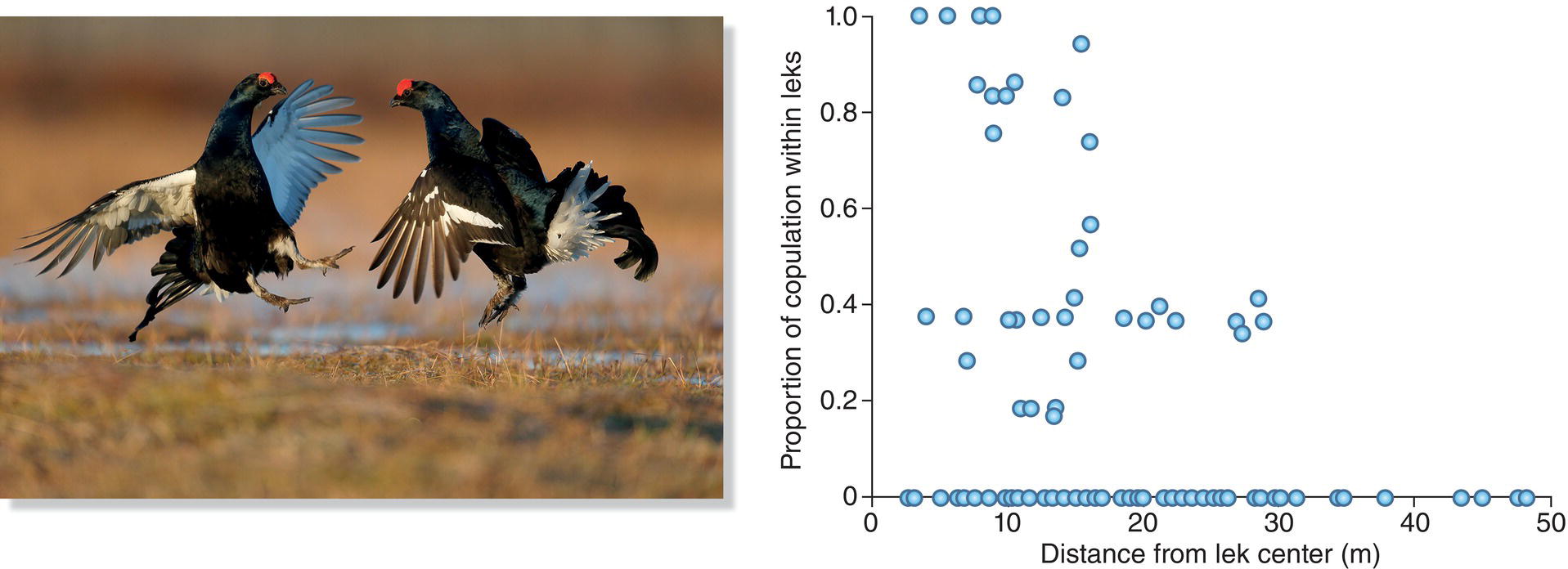

Just as no one acoustic element predominates in female mate preferences, so too no one visual aspect of courtship does the job across all bird species. In some birds, female preferences revolve around the intensity and frequency with which males perform visual displays that show off tail plumes, or wing feathers, or throat pouches. So, when Black Grouse (Tetrao tetrix) gather in groups in Finnish fields to compete for display territories visited by selective females, males differ in their overall activity, and the frequent displayers in relatively large central territories secure more mates than less active, peripheral males (Rintamäki et al. 1995) (Fig. 9.03). This finding suggests that the females evaluate their mates in part by the properties of their visual displays, which determine a male’s territorial success and his ability to stimulate female observers.

Fig. 9.03 Lekking display of a male Black Grouse (Tetrao tetrix). Males compete for access to mates by displaying their bright ornaments in groups termed leks. In this species, males that have display sites near the center of the lek tend to have higher mating success.

(From Rintamäki et al. 1995. Reproduced with permission from Elsevier. Photograph by Mike Lane.)

For other species, the size of a special male ornament most strongly affects female mate choice. For example, some researchers have found a relationship between the length of the Indian Peafowl’s (Pavo cristatus) amazing train and male reproductive success (Loyau et al. 2008). Peahens may attend to this aspect of the male or some other component of the train, such as the density of eye‐spots, when making a decision about which of several males to select as a mate. Peahens are not the only females with such preferences. In the Eurasian Penduline‐Tit (Remiz pendulinus), choosy females prefer males that have larger dark eye‐stripes (“masks”) over males with less prominent masks. As a result, males with large masks pair off more quickly than their less‐well‐masked rivals (Pogány and Székely 2007).

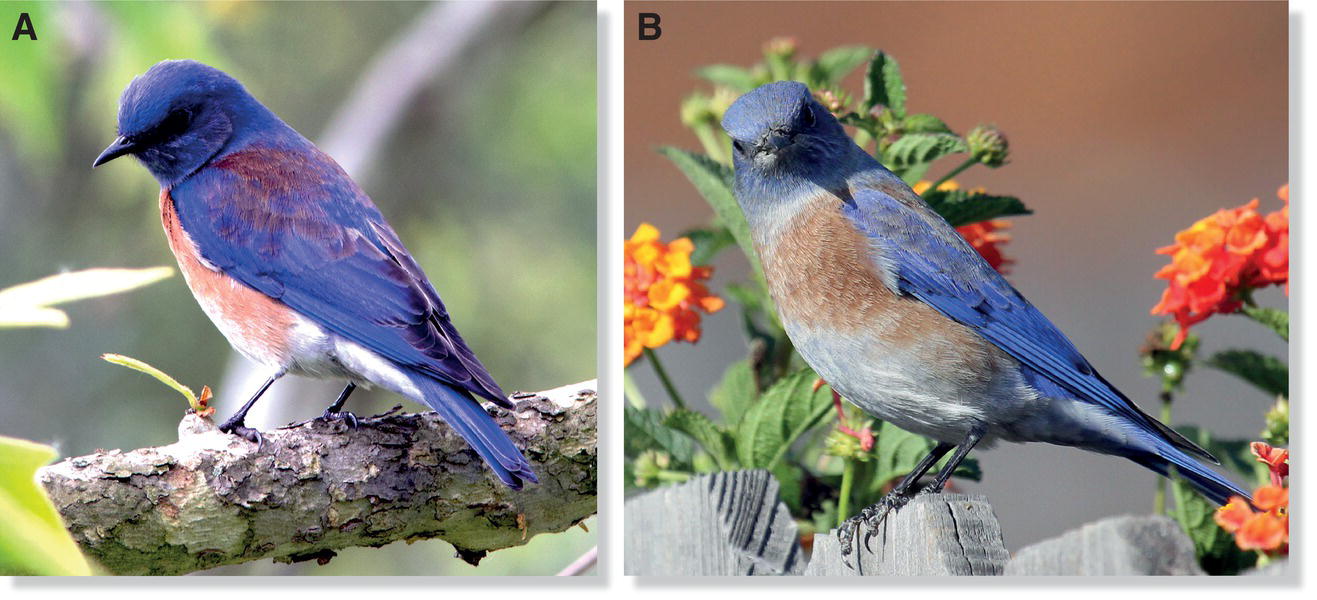

For other species, female mate choice may revolve around the extent to which a feathered body part reflects ultraviolet (UV) radiation, the yellowness of a patch of feathers, or the redness of a throat pouch (Chapter 4). In particular, carotenoid pigments, which make feathers appear yellow or red, are now believed to be a cue that females of many bird species use to evaluate the attractiveness of potential mates (Hill and McGraw 2006). The general rule—“the brighter, the better”—applies, for example, to the American Redstart (Setophaga ruticilla), an attractive wood‐warbler that breeds across much of northern North America. In this species, males with more brightly colored reddish feathers on their flanks sire more of their mate’s offspring than those with paler flank plumage (Reudink et al. 2009). Females of these songbirds sometimes exercise the option of seeking out redder neighboring males for extra‐pair copulation, a widespread attribute in birds, as we shall see (Westneat et al. 1990). Likewise, when some House Finch (Haemorhous mexicanus) males were artificially made redder by the application of hair dye, these extra‐bright males paired off with females more rapidly than those whose feather color had been made a paler red (Hill 1991) (Fig. 9.04). Studies of this sort make it clear that female mate choice occurs widely in birds (Box 9.01).

Fig. 9.04 House Finch (Haemorhous mexicanus) color variation. Although male House Finches generally have red plumage (left), yellow males (right) also occur in the wild. Color differences are due to dietary carotenoid variation; redder males are directly signaling to females that they have had better access to dietary carotenoids and are in better condition. Females therefore prefer red males over dull or yellow males.

(Photograph by Kevin McGraw.)

9.2 Pair bonds, courtship, and divorce

The sexual signaling that goes on when males court females may serve to induce a female to mate right away, but signals of this sort also can help establish a pair bond between a male and a potential mate as a prelude to eventual copulation and reproduction. In many birds, males and females form a social partnership that lasts for at least one breeding season, and sometimes for many more than one. In the Little Penguin (Eudyptula minor) of Australia and New Zealand, for example, some pairs remain together for as many as 13 years (Nisbet and Dann 2009).

One behavior that in some birds helps form and maintain a pair‐bond relationship is courtship feeding, in which a male brings food to a female during courtship. These gifts may provide information that influences the intensity of the bond between the male and female and thus the female’s sexual receptivity. The quantity of food delivered can have these effects on females, as studies in Poland have shown for the Northern Shrike (Lanius excubitor) (Tryjanowski and Hromada 2005). Male shrikes that offer their partners a large gift of food—that is, a sizeable sparrow or lizard rather than a small cricket—are more likely to be rewarded by a copulation. Likewise, long‐term studies of Black‐legged Kittiwakes (Rissa tridactyla) on the coast of France have found that in successive years females are more likely to re‐pair with males who did a better job of courtship feeding in the previous year (Helfenstein et al. 2003).

Although often it is popularly thought that many pairs of birds “mate for life,” pairs in most species often break up between or even within breeding seasons. These breakups may happen after one member of the pair dies or when one or both members subsequently pair with a different individual. Behavioral ecologists generally refer to this switching between pair‐bonded mates as divorce, and in birds the female usually takes the lead in switching mates. Female birds can initiate a split even in mid‐season, as shown by an experiment involving Black‐capped Chickadees (Poecile atricapillus) in Ontario, Canada. Two researchers, Ken Otter and Laurene Ratcliffe (1996), captured females that had paired with high‐status (dominant) or low‐status (subordinate) males. These females were held in captivity long enough to permit seven neighboring females to abandon their current mate and move to territories with the experimentally “widowed” males. Six of the seven divorcees paired off with a high‐status male; only one accepted a member of the subordinate group. This elegant experiment shows that female birds often are aware of the dominance status of various nearby males, or perhaps are alert to the quality of their territories, and are prepared to divorce their current, lower quality mate should a better opportunity present itself.

In other species, females may eschew divorce, but make the number of eggs they lay dependent upon the physiological state of a male. This is known to occur in Black Wheatears (Oenanthe leucura) (Fig. 9.05), a species found in southwestern Europe and northwestern Africa. In this species, females appear to wait until they have observed their partners carrying stones to their nest cavities before deciding how many eggs they will lay (Soler et al. 1996). Females produce more eggs when their mates have carted in many heavy rocks during the nest‐building period, whereas males that cannot—or are unwilling to—carry large rocks to the nest caves are on average given fewer copulation attempts. Thus, a given male Black Wheatear’s reproductive success appears to depend on his mate’s decisions, which in turn are influenced by his behavioral performance.

Fig. 9.05 Nest stones as an indicator of male quality. As the mating season begins, Black Wheatear (Oenanthe leucura) males carry hundreds of stones to build the base of a nest mound. Females gauge a male’s parental provisioning potential based on the quantity and quality of stones at a nesting site, laying more eggs with males that carry heavier stones.

(Photograph by Manuel Soler.)

Additional evidence helps explain why female wheatears cue in on stone carrying as an indicator of male quality. Males that carry very heavy stones have stronger immune systems (Chapter 7) than do males that only carry smaller stones (Soler et al. 1999). A healthy male may be able to help the female rear a larger clutch. Alternatively, a female with a healthy male may gain by working harder in a year when she has acquired a mate with “good genes” rather than holding back to increase the odds that she will survive to reproduce again in a future year. However, this pattern in which females paired with top males lay more eggs also might arise if the females in the best condition were to acquire stronger males as partners. This outcome would leave the females that are unable to produce a large clutch with lower quality males (Lebigre et al. 2007).

Female birds exhibit many other forms of mate choice, some of which are quite subtle. For example, Sjouke Kingma and colleagues (2009) have found that female Eurasian Blue Tits (Cyanistes caeruleus) at their study site near Groningen in the Netherlands adjust the amount of testosterone they contribute to their eggs in relation to the intensity of the UV coloration of their mate. Eggs containing the sons of high‐UV males receive more testosterone from their mothers. These hormonal adjustments by egg‐laying females may affect the attractiveness of their sons, in turn influencing the reproductive success of their mates, that is, the number of descendants that their partners contribute to the next generation. Females forced to accept lower quality males may gain by withholding testosterone from their eggs if the hormone is expensive to produce and if the sons of these males would be unable to use the biochemical in a developmentally advantageous manner.

At the most general level, we now know that any of a very broad spectrum of male attributes can affect the likelihood that a male will succeed in attracting a mate or in inducing her to lay more eggs, or eggs of higher quality. The cues used by females may even vary between populations of the same species. As described in more detail in Box 3.03, a comparison of mate choice in the North American and European subspecies of the Barn Swallow (Hirundo rustica) showed that females in different populations may focus on different male ornaments. In North American populations of Barn Swallows, males whose ventral plumage is more heavily pigmented secured mates more rapidly than their duller rivals (Safran and McGraw 2004). In contrast, in Europe the males most attractive to females are those with unusually long and symmetrical tail streamers, and differences in plumage coloration play little role in mate choice (Møller 1988). This example illustrates that although female mate choice, broadly defined, may be standard practice in birds, the nature of the preferences can vary markedly from species to species and sometimes from population to population within the same species (Box 9.02).

9.3 Male mating preferences

Many fewer studies have considered whether male birds, like females, are choosy about their partners. As Darwin himself noted, this relative lack of attention to mate choice by males stems from the fact that males are much more likely to court females than the other way around. Therefore, it has made general sense to focus first on the cues females use when evaluating courting males rather than to investigate the intuitively less likely phenomenon of mate choice by males.

Nonetheless, theoretical reasons exist for thinking that male mate choice happens too. Social monogamy is extremely common among birds, and to the extent that males limit themselves to one social and sexual companion per breeding season, they certainly could gain by selecting a superior partner, one with whom a male is likely to rear an above‐average number of surviving offspring. In an impressive diversity of birds, monogamous males cooperate with their mates in sharing most or all of the tasks associated with reproduction (except, of course, egg laying). For such a male to maximize the return on his paternal investments, he may benefit by identifying an especially fertile female or one that is an unusually good parental partner. For example, in the European Pied Flycatcher (Ficedula hypoleuca) population in central Spain, only some females have a white patch on the forehead, and these individuals raise more fledglings on average than do females that lack this patch (Morales et al. 2007) (Fig. 9.06). If males preferred white‐patched females, they might well derive a reproductive benefit from their preference.

Fig. 9.06 Plumage variation as a signal of female quality. In some populations of the European Pied Flycatcher (Ficedula hypoleuca), variation in forehead patch size is a signal of individual quality. For example, females with white forehead patches (right) occupy better territories, where they face fewer parasites and have higher chances of producing more offspring.

(Photographs by Judith Morales‐Fernaz.)

In a good many bird species, females do look rather like males, and this resemblance suggests that the sexes may be engaged in mutual mate choice based on appearance cues. This statement may be particularly true when males vary greatly in their attractiveness so that some males have the option of rejecting certain females in favor of others. One experiment that definitively documented male preferences explored the mating patterns in the Eurasian Blue Tit (Cyanistes caeruleus), whose males tend to associate more with females whose crown feathers reflect UV radiation and associate less with females whose UV plumage has been experimentally diminished (Hegyi et al. 2007). Males in this species therefore select females on the basis of a plumage trait, just as females often choose males with special feather ornaments. Likewise, another study—this one on the Rock Petronia (Petronia petronia), a relative of the exceedingly widespread and more somber House Sparrow (Passer domesticus)—documented that females with an experimentally reduced yellow breast patch were courted less often, and mated at a significantly later date than those with a larger breast patch (Griggio et al. 2005). Such studies demonstrate that male mate choice is a reality in at least some bird species and suggest that overall it is more common than generally realized.

9.4 Adaptive value of mate choice

What might choosy females (and choosy males) gain from their preferences for partners capable of providing them with attractive songs, ornaments, displays, and the like? This question really concerns the adaptive value of mate choice and addresses the long‐term evolutionary causes of a choosy female’s or male’s behavior, not the immediate short‐term physiological causes of a given individual’s behavior. The distinction is considered essential by most behavioral biologists, who distinguish between two kinds of questions (Box 9.03): namely, proximate questions that deal with the internal mechanisms that enable individuals to carry out certain actions, versus ultimate questions that examine the longer term evolutionary explanations for behaviors.

The remainder of this chapter focuses primarily on the ultimate causes of bird behavior; on why, for example, individuals that prefer certain attributes in their partners are more likely to leave surviving descendants than if they had different preferences. Research on the adaptive value of animal characteristics complements—but does not replace—studies on the proximate causes of behavior. Both are needed to paint a complete picture of animal behavior (Box 9.04).

9.4.1 Genetic benefits from mate choice

There are many reasons why a female might derive reproductive benefits from her choice of a partner or partners. When studying female mate choice, we must consider the possibility that female preferences are not actually adaptive, but instead arise via selection that favors those males best able to persuade females to mate with them. This “empty advertisement hypothesis” suggests that females are lured into accepting sperm from persuasive partners that really have nothing of value to offer them, only courtship that activates the proximate mechanisms (Box 9.03) underlying female mating behavior. However, under this scenario, even if the females gain nothing directly from a sexual partner, the females that prefer the most stimulating males may tend to have sons that have inherited that preferred trait and that therefore are especially capable of acquiring mates in the next generation. Given these conditions, the empty advertisement hypothesis is converted into the more widely accepted sexy son hypothesis, with choosy females gaining attractive sons (even if nothing else) from their mate preferences (Weatherhead and Robertson 1979). One example that supports the sexy son hypothesis comes from European Starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) studied in southern Germany, where the sons of polygynous fathers defend more nest boxes and produce more courtship songs than the sons of monogamous fathers (Gwinner and Schwabl 2005). In other words, the sons’ apparent inheritance of their fathers’ mating behaviors would enable females to produce sexy sons by mating with males that are able to acquire several mates rather than just one social partner.

The sexy son hypothesis is not the only adaptive explanation for mate choice that focuses on a possible hereditary benefit from the behavior. For example, a choosy female could get sperm from a hereditarily healthy male whose genes—when passed on to his offspring—will help them develop a strong immune system. Females that made mate choices based on cues of male health could give their progeny a genetic benefit.

Likewise, when male plumage coloration is reflective of the carotenoid content of foods consumed, a female preference for bright reds or yellows in potential partners would lead females to mate with birds that are good foragers. If this ability has a hereditary component, selective females might be securing partners with genes that promote skillful foraging in their offspring.

Some of the clearest evidence for genetic benefits comes from species in which males provide no parental care after mating with the female. Females in these species often are highly selective about which males they choose as mates, presumably to obtain the best genes for their offspring. In the Black Grouse (Tetrao tetrix) of Europe, for example, females carefully observe many displaying males before choosing one to fertilize their eggs (Fig. 9.03). The same male often is chosen by several females, whereas most males in the display area are never selected by any visiting females. The most reproductively successful males are those that dominate other males while keeping their tail ornaments from being damaged in fights. They usually are also the males that occupy central display territories, an achievement that often requires years of intense competition (Höglund et al. 1994; Rintamäki et al. 2001).

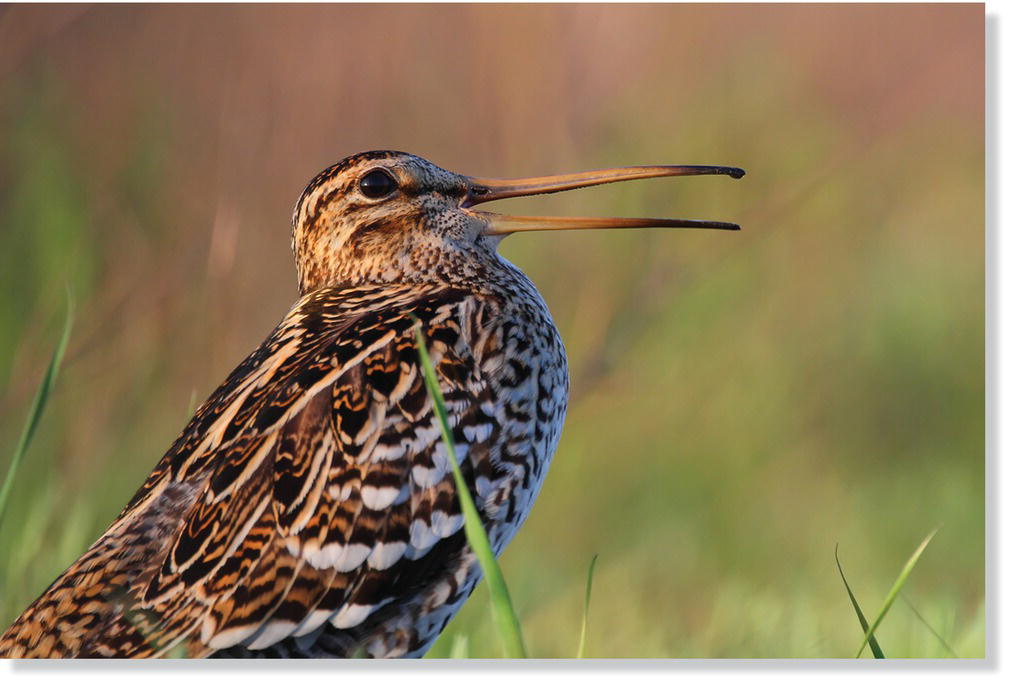

The female preference for central‐territory grouse strongly suggests that they gain good genes for their offspring from these males, genes that promote the development of attractive and/or healthy offspring. In the Great Snipe (Gallinago media), a shorebird of Europe and northern Asia, the males chosen most often by females have a stronger immune response than their less successful neighbors, suggesting that they are in the best overall body condition (Ekblom et al. 2005) (Fig. 9.07). Once again, this result suggests an indirect (genetic) benefit from mate choice, although the finding does not absolutely rule out a direct (material) benefit in the form of a reduced risk of acquiring a contagious disease or parasite from preferred sexual partners.

Fig. 9.07 Male Great Snipe (Gallinago media) display. Leks of polygamous species like this one may have 5–30 males competing for females simultaneously.

(Photograph by Dmitry Yakubovich.)

With respect to the benefits to males from mate choice, recall that, as described earlier in this chapter, male Eurasian Blue Tits (Cyanistes caeruleus) prefer females with relatively intense UV‐reflecting crowns. In one study, females of this sort survived better than those with less UV reflectance in their feathers (Doutrelant et al. 2008). Moreover, female Eurasian Blue Tits with brighter yellow (carotenoid‐based) plumage produced larger clutches and had higher fledging success than females with duller yellow coloration. To the extent that males have a choice between bright and dull females as mates, this study suggests that a male preference for brighter females would translate into more progeny for the male. This conclusion also may apply to the Rock Petronia (Petronia petronia), in which females with a larger yellow breast patch weighed more and had more broods per year than conspecifics with a naturally smaller yellow patch (Griggio et al. 2005). Male mate preferences, like mate selection by females, appear to have the potential to raise the reproductive success of choosy individuals.

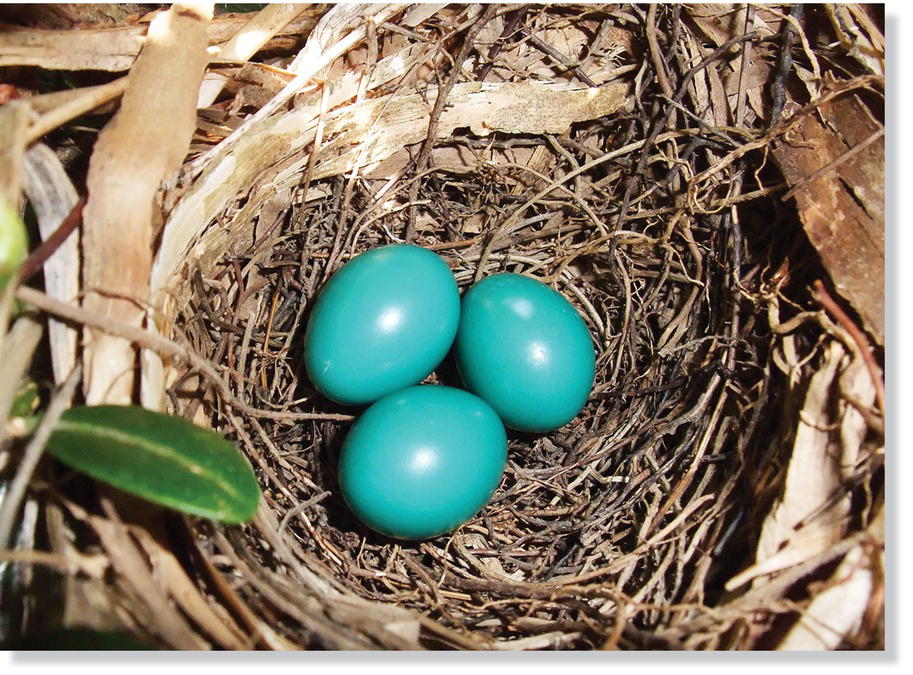

Moreover, just as females can exercise a kind of mate choice after pairing with a male by modifying their investment in offspring depending on the quality of their partner, so too some male birds appear to adjust their investment in parental care in relation to the quality of their mate. For example, variation in the color of eggs laid by female Spotless Starlings (Sturnus unicolor) in Spain affects male decisions about the care of the resulting offspring. Female starlings that have had some wing feathers removed—thus lowering their condition by making it more difficult for them to fly—lay paler blue eggs than do control birds with a full complement of primaries. Males paired to females that laid pale eggs were less active parents when they started to provision their brood (Soler et al. 2008). Similar male responses to egg color have been documented in the Gray Catbird (Dumetella carolinensis), a North American species that also lays blue eggs (Hanley et al. 2008) (Fig. 9.08). Females in these and other species probably are under pressure to provide signals that encourage their social partners to work hard for their progeny.

Fig. 9.08 Egg color signals mate quality. In the Gray Catbird (Dumetella carolinensis), males are more likely to provide parental care to their offspring when eggs are a vibrant shade of cerulean‐blue (a sign of female condition).

(Photograph by Elizabeth A. Sellers.)

9.4.2 Material benefits from mate choice

In the realm of mating decisions, direct benefits are those that return an advantage directly to the choosy individual. For example, females might prefer males that give them greater nutritional gifts via courtship feeding. In the case of the Yellow‐legged Gull (Larus michahellis) studied on islands off northwestern Spain, females that had been consistently well fed by their courtship partner were less likely to move during copulation, so the male was more likely to transfer sperm during the mating and thus was more likely to sire the offspring of that female (Velando 2004). By making effective copulation contingent upon her mate’s ability to provide her with food, a female could use mate choice to acquire a material benefit, namely, the calories and nutrients needed to enhance her personal condition or her capacity to produce offspring. Likewise, in British Columbia, Canada, the rate at which male Ospreys (Pandion haliaetus) provide their partners with fish during the courtship phase is related to the probability that the female will lay a clutch (Fig. 9.09). Moreover, the frequency of courtship feeding by the male, which is a function of his fish‐catching ability, is correlated with the rate at which he later provisions his offspring. Thus, by evaluating the nature of a male’s courtship feeding, female Ospreys can secure a competent forager as a partner in the feeding of their offspring (Green and Krebs 1995).

Fig. 9.09 Courtship feeding. Particularly common in species for which food resources are inconsistent or hard to find, courtship feeding—a pair‐bonding activity before nestlings hatch—demonstrates to females that a mate is capable of providing food to future young. Here, a male Osprey (Pandion haliaetus) returns with a fish for his mate.

(Photograph by Barbara Rich.)

Moreover, a highly successful forager is likely to be in generally good health and therefore unlikely to pass a contagious debilitating disease to his partner or her offspring. Depending on the bird species, a male’s appearance, the quality of his plumage ornaments, the brightness of the reds and yellows in his feathers, the intensity of his behavioral displays, the number of large rocks he carries to his partner, the nature of his songs, and even the size of the nest he builds for his partner all provide potential indicators of his past, current, and even future physiological condition, and thus of his health and capacity for parental care. For example, in American Kestrels (Falco sparverius) studied in Saskatchewan, Canada, males with bright orange skin (the product of high levels of carotenoids) about the base of the bill (Fig. 9.10) are less likely to have blood parasite infections later during the breeding season when male parental care becomes important to offspring survival. Therefore a preference for males with this coloring would help females acquire capable partners (Dawson and Bortolotti 2006). Likewise, in an experiment in which male House Finches (Haemorhous mexicanus) were inoculated with an infectious bacterial pathogen, birds with redder plumage recovered more quickly than birds with paler, yellower feathers (Hill and Farmer 2005). Because female mate choice in this species is biased in favor of redder males, females could pair off with males able to be better parents because they were resistant to certain diseases.

Fig. 9.10 The Cere can indicate mate quality. In American Kestrels (Falco sparverius), males with the brightest orange cere (bill skin, arrow) are most likely to be the best providers late into the nestling period, when offspring survival is critical but food can be harder to find.

(Photograph by Patricia Donald.)

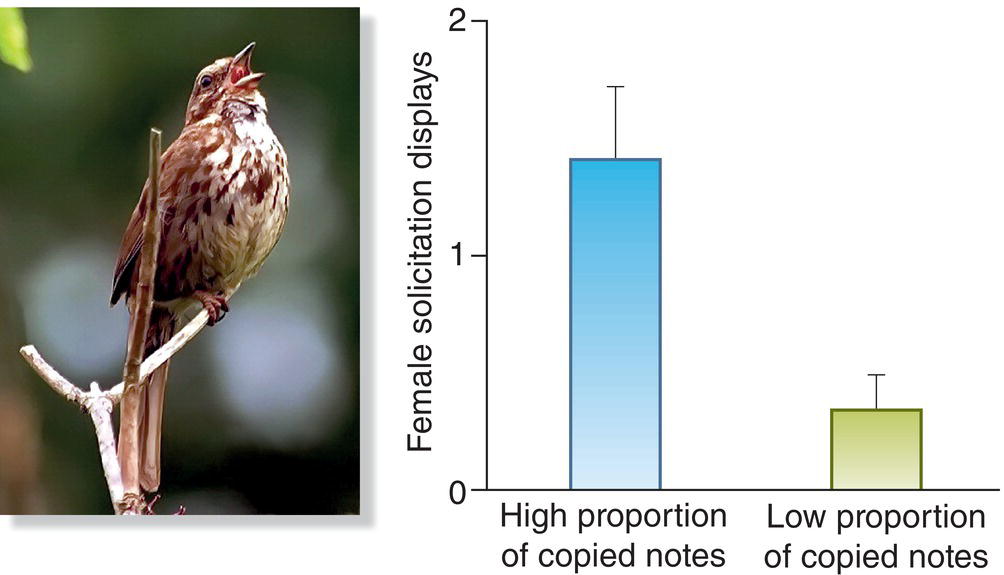

The quality of a male’s song sometimes serves as another potential indicator of his paternal ability. In this context, it is striking that a male’s ability to learn songs early in his life often is very sensitive to the conditions experienced at that time (Chapter 10). For example, nestlings that receive relatively little food might be handicapped when it comes to imitating their species’ song(s). As a result, a female listening to an adult male sing might learn something about his past developmental history, which in turn might influence his current health and capacity for competent paternal behavior. In this regard, a series of careful laboratory studies have shown that young Song Sparrow (Melospiza melodia) males that are in good condition learn and copy the songs they hear more accurately than do young sparrows that are in poor condition. These better songs later provide information to mating females: when adult female Song Sparrows that have been dosed with hormones to make them sexually responsive listen to taped songs, they are more likely to elevate their tails into the precopulatory position when they hear accurate copies of their species’ song than when they hear the poorer imitations made by disadvantaged males (Nowicki et al. 2002) (Fig. 9.11). This kind of preference could lead the female to mate and bond with a better‐than‐average male, one with a good copy of his species’ song, which correlates with his ability to provide better‐than‐average assistance to the female and her brood.

Fig. 9.11 Song production reveals male quality. Male Song Sparrow (Melospiza melodia) nestlings that experience stress during song learning in early development will produce poorer quality songs (with a low proportion of copied notes) compared with non‐stressed males (that produce a high proportion of copied notes). Females prefer songs that are reproduced with accuracy, regardless of the tutor song structure.

(From Nowicki et al. 2002. Reproduced with permission from the Royal Society. Photograph by Hector Chu‐Joy.)

9.5 Sexual selection and mating systems

Mate choice, whether by females or by males, has evolutionary consequences if the differences among the individuals subject to choice are hereditary. Individuals with the favored hereditary attributes may experience greater reproductive success than others of their species. Over time, the genetic basis of the ability to sing a particular kind of song, or to exhibit a particular ornament, or to engage in certain courtship displays, or to supply mates with their favored foods can spread through the species.

Sexually appealing traits generally come with costs: songs can attract predators as well as mates, ornaments make individuals more conspicuous to their enemies, animals focused on displaying to potential partners are less alert to danger, and individuals that offer food to their mates expend valuable time and energy in collecting what they later give away. Charles Darwin (1871) realized that such survival‐reducing traits required a special explanation, which he supplied in the form of his theory of sexual selection. He argued that elaborate ornaments, for example, might put a male at special risk of attack by predators and thus might be thought to be maladaptive, but if these ornaments also increase the odds that a male will acquire a mate and reproduce successfully, then sexual selection favoring the ornaments could trump natural selection against them. The same argument can be applied to any attributes that appear to function strictly in terms of the competition among individuals for mates, whether these are sexually attractive characteristics or traits that enable individuals to prevail over others of the same sex in mating‐related struggles.

As covered in more detail in Chapter 3, sexual selection now is generally considered to be one component of natural selection, in that the conditions required for both forms of selection are fundamentally similar. Both natural and sexual selection act on hereditary variation among individuals in their ability to pass on their genes, but sexual selection does so in the narrow context of competition for access to mates. Nevertheless, sexual selection theory is valuable because it helps focus attention on the significance of pure reproductive competition (Andersson 1994). One of the benefits of this perspective is that researchers alert to the theory can identify puzzles that they otherwise might ignore, particularly those when males or females appear to behave in ways that on first glance might seem to reduce their chances of acquiring mates. As discussed earlier in the chapter, monogamy by males is one example of this sort of puzzle, because the truly monogamous male appears to forego opportunities to mate with more than one female.

9.5.1 Solving the puzzle of male monogamy

Bird mating systems are wonderfully diverse, ranging from monogamy (one male mates with one female) to polyandry (one female mates with several males) to polygyny (one male mates with several females) (Box 9.05). One would think that sexual selection would favor polygynous males, those that acquire more than one mate in a breeding season and thereby increase their chances of fertilizing eggs and leaving many descendants. Because most birds appear to be monogamous, behavioral researchers have wondered whether, under certain special conditions, polygyny actually might reduce, rather than increase, a male’s reproductive success.

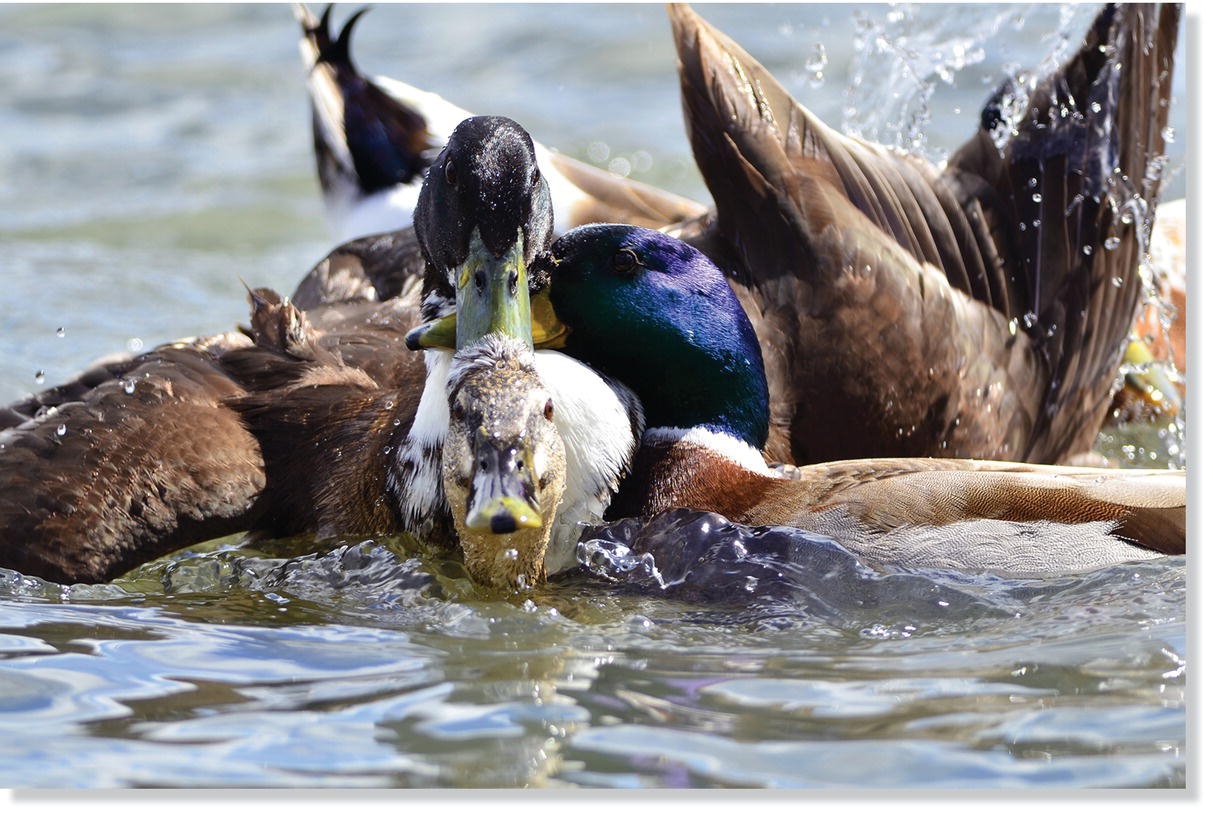

One such condition involves reproductive retaliation by abandoned females so that if a male were to leave one partner in order to secure another, his original mate might copulate with another individual. In keeping with this hypothesis, females of many species of birds are sexually receptive to males other than their partners. Indeed, one of the most significant findings in behavioral ornithology during the past several decades is that most bird species previously assumed to be strictly monogamous are not nearly so faithful as researchers had thought. Not so long ago, the British ornithologist David Lack (1968) famously stated, “Well over nine‐tenths (93%) of all passerine subfamilies are normally monogamous … Polyandry is unknown.” Now, however, we know from genetic investigations that in about 90% of all birds, at least some females mate with males other than their social partners. This behavior is termed extra‐pair copulation, with the outcome sometimes resulting in extra‐pair fertilization of eggs (Box 9.06).

Given the generally high prevalence of extra‐pair mating, it is the rare cases of true monogamy that require special explanation. Monogamy would likely be rarer still if males of some species did not attempt to monitor and control their partner’s behavior in order to reduce her opportunities to copulate with other males. Active mate guarding is a common feature of male behavior in many birds, with males following their partner closely, especially during the female’s fertile phase. The fact that male Abert’s Towhees (Melozone aberti) (from the introduction to this chapter) remain so close to their mates is consistent with a guarding function: when the male stays within centimeters of his partner, it must be hard for her to slip away for a clandestine meeting with another male.

The consequences of mate guarding have been assessed experimentally in field studies of many bird species. If active guarding by males does reduce the probability that the female partner will engage in extra‐pair copulations, then temporary removal of the male social mate should lead to a higher probability that his mate will go elsewhere to copulate. This generally turns out to be the case, as shown by experiments on Bluethroats (Luscinia svecica), an attractive Eurasian songbird. When Bluethroat males were held in a cage for only one morning during their mate’s fertile period, the proportion of extra‐pair offspring in her next clutch was twice that of females whose males had not been prevented from guarding their mate (Johnsen et al. 2008).

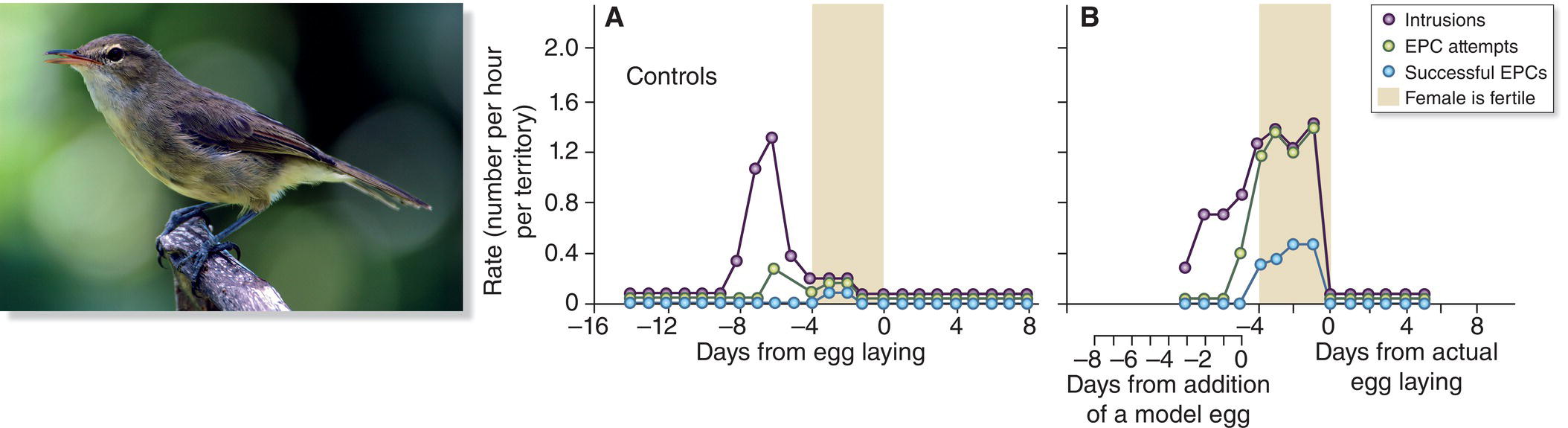

Jan Komdeur and his colleagues (2001, 2007) have used similar experiments to show that male mate guarding is highly effective in the Seychelles Warbler (Acrocephalus sechellensis). In this island species, the male typically remains vigilant and close to his mate for several days before egg laying, in the period when an egg can be fertilized. Female Seychelles Warblers lay only a single egg, and therefore if a male can sexually monopolize his partner as that egg is being formed and laid, he greatly improves his chances of fertilizing it. Once the egg is laid, however, males no longer guard their partners and instead may attempt to find a neighboring female with whom to mate. Komdeur and company put false eggs into the nests of females that had yet to lay, duping their mates into relaxing their mate guarding even though their females were still fertile. Neighboring males were quick to take advantage of the situation by sneaking into the territory of the unguarded female and copulating with her (Fig. 9.12). As a result, the rate of extra‐pair copulations was much higher for poorly guarded females than for those with an alert protector.

Fig. 9.12 Pre‐breeding mate guarding and extra‐pair copulation (EPC). Male Seychelles Warblers (Acrocephalus sechellensis) fiercely mate guard during the female fertile period to avoid EPCs. (A) In control pairs, the rate of territorial intrusions by other males, EPC attempts, and successful EPCs drops off during the female fertile period, as expected. (B) When males were experimentally fooled into thinking that their mate was past her fertile period (via the addition of a model egg in a newly lined nest), they left her unguarded, allowing other males to engage in more territorial intrusions and gain more EPCs.

(From Komdeur et al. 1999. Reproduced with permission from the Royal Society. Photograph by Jonathan Hornbuckle.)

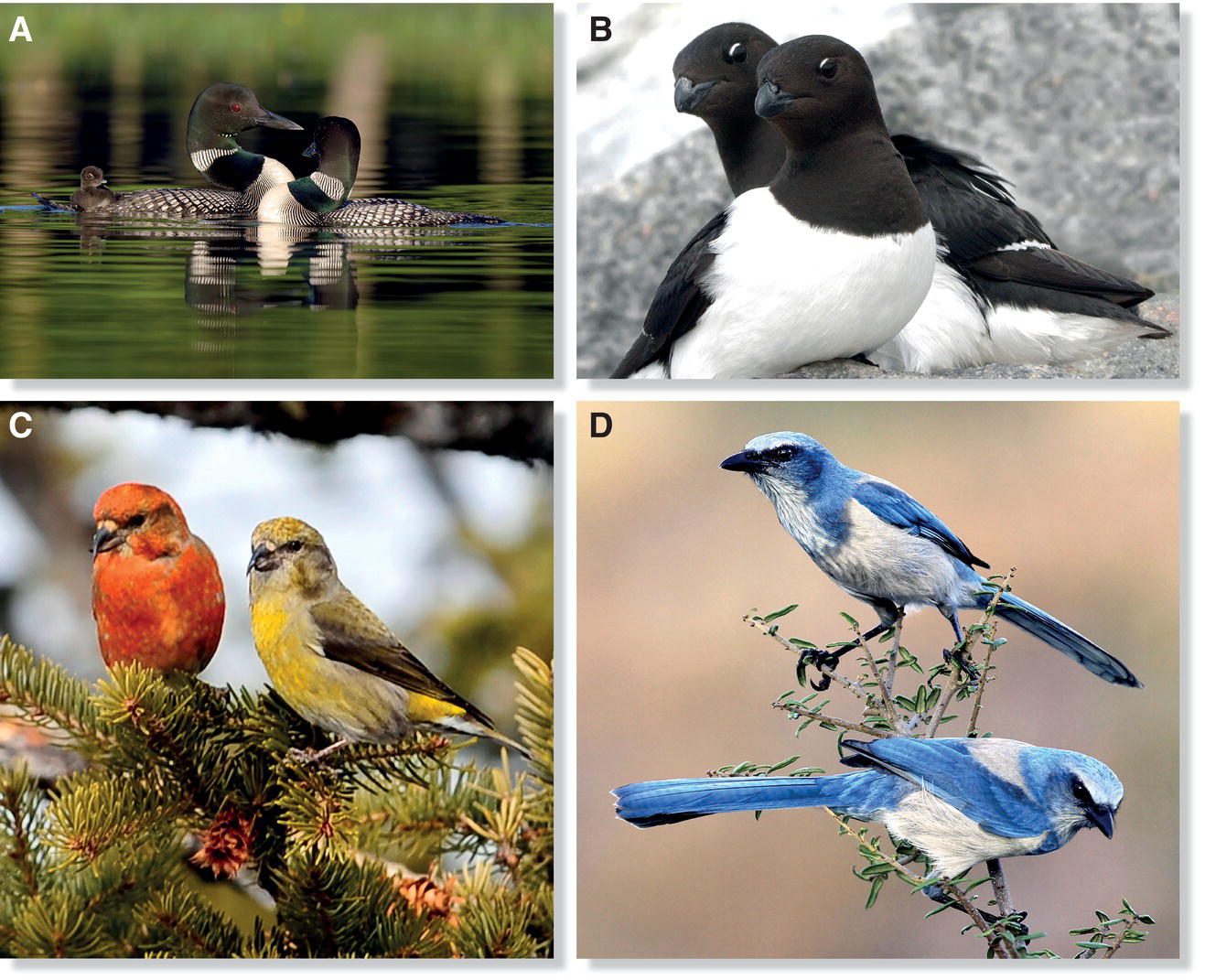

One point to consider here is that when mate guarding is necessary and effective, the potential for female infidelity can push males towards monogamy, because they must forgo opportunities to mate with other females while guarding their own mates. Another point is that social monogamy—the pair bonding typical of so many birds—does not always, or even often, equate with genetic (true) monogamy in which a socially monogamous couple only has offspring of their own. Such genetic monogamy does occur sometimes, however (Fig. 9.13). For example, Common Loons, the widespread bird known in Eurasia as the Great Northern Diver (Gavia immer), apparently never engage in extra‐pair copulations (Piper et al. 1997). Likewise, in the colonial Dovekie (Alle alle), the species known as the Little Auk in Eurasia, males occasionally attempt an extra‐pair copulation with a neighboring female, but these females make cloacal contact all but impossible and almost never produce offspring with a male other than their social partner (Wojczulanis‐Jakubas et al. 2009). A few songbirds also are represented in the small truly monogamous contingent; for example, a genetic study of a Norwegian population of the Red (aka Common) Crossbill (Loxia curvirostra) found that all offspring were sired by the male that was socially bonded to their mother (Kleven et al. 2008). Similar genetic monogamy occurs in the Florida Scrub‐Jay (Aphelocoma coerulescens), a species whose complex social behavior is discussed later in this chapter (Townsend et al. 2011).

Fig. 9.13 Reproductively monogamous bird species. The following species are among those that form socially and genetically monogamous pair bonds: (A) Common Loons (Gavia immer), (B) Dovekies (Alle alle), (C) Red Crossbills (Loxia curvirostra), and (D) Florida Scrub‐Jays (Aphelocoma coerulescens).

(Photographs by: A, Mary Anne Pfitzinger; B, Leo Roos; C, Christine Pentecost; D, Matthew Studebaker.)

Far more common, however, is the finding that a number of the offspring produced by pair‐bonded males and females have a father other than the female’s social companion. In some species, extra‐pair paternity is relatively low; for example, in a Finnish population of Eurasian Three‐toed Woodpeckers (Picoides tridactylus), fewer than 10% of the nestlings sampled had been sired by a male other than the female’s social partner (Li et al. 2009). On the other hand, fewer than 50% of Reed Bunting (Emberiza schoeniclus) chicks possessed the genes of their mother’s social partner (Dixon et al. 1994). Although not quite so eager for extra‐pair copulations as Reed Buntings, female California Towhees (Melozone crissalis)—a socially monogamous species in which males and females stay in close contact, like their relatives the Abert’s Towhees (Melozone aberti)—nevertheless engage frequently in extra‐pair copulations, with more than 40% of all nests having at least one egg sired by an extra‐pair male (Benedict 2008). In such cases the puzzle of male monogamy can be partly resolved by noting that monogamous males actually are would‐be polygynists who readily take advantage of opportunities to sire additional offspring by mating with extra‐pair females (Box 9.07).

Nonetheless, in explaining why males of so many birds spend most of their time and energy associating with a single female in a pair‐bonded relationship (instead of trying to mate with as many females as possible), we need hypotheses that focus on the benefits of social monogamy. The mate‐guarding hypothesis is not the only such explanation, which is fortunate because it cannot explain, for example, why male Purple‐crowned Fairywrens (Malurus coronatus) in Australia remain close to their females at all times, whether they are fertile or not (Fig. 9.14), nor why they fail to court other females that they happen to encounter (Hall and Peters 2009). In this species and others, monogamy seems driven by the female’s voluntary fidelity to a social partner, not by the male actively preventing his partner from engaging in extra‐pair copulations.

Fig. 9.14 Purple‐crowned Fairywren (Malurus coronatus) pair. Males of this species guard their partners despite the negligible risk of extra‐pair copulation.

(Photograph by Alwyn Simple.)

Let us consider still another explanation for monogamy, that a pair‐bonded male can boost the production of his own surviving offspring by helping his social partner rear a brood of baby birds. This hypothesis makes intuitive sense, because many male birds clearly have the potential to be helpful parents by building a nest, incubating eggs, brooding nestlings, or feeding fledglings. The “mate‐assistance hypothesis” for monogamy generates a number of predictions, one of which is the expectation that the paternal male will have sired a least some of the offspring he helps rear. Genetic studies have upheld this prediction for the great majority of socially monogamous bird species, in which the female’s social partner typically has sired at least some of the offspring of his mate.

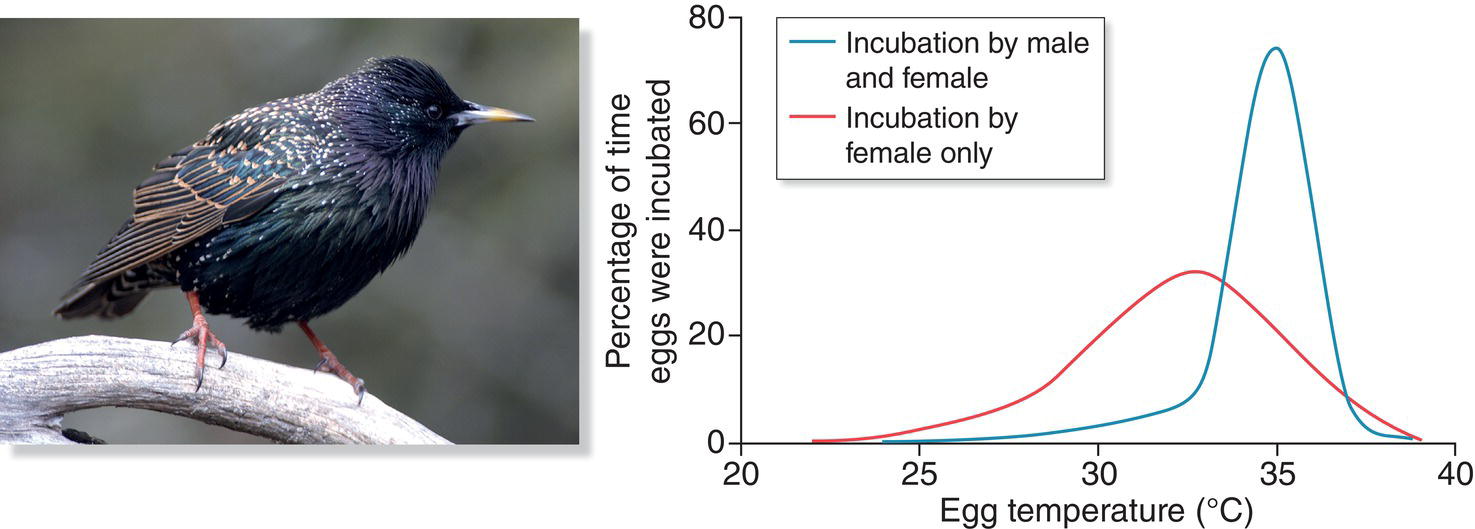

A second prediction of the mate‐assistance hypothesis is that females who lose part or all of the assistance of their pair‐bonded partner will rear fewer surviving progeny than females who retain their helpmate through the breeding season. This prediction also has broad support, because the male’s contribution to parenting has been shown to be valuable in many cases. In European Starlings (Sturnus vulgaris), for example, males vary in how much they contribute to the incubation of their mate’s eggs, with some males incubating much of the time and others less so. The males that are the most faithful incubators help their mates keep the eggs at a higher average temperature during the incubation period. These higher egg temperatures promote more rapid development of the embryos within, which is advantageous for the offspring and therefore for both parents (Komdeur et al. 2002).

The importance of males to their mates also has been shown through experimental removal of the partner, which often has a negative effect on the number of fledglings produced at nests cared for by widowed females. If, for example, the male partners of Snow Buntings (Plectrophenax nivalis), a bird of the Arctic, are removed early in the incubation period when males often feed their mates, the widowed females rear fewer offspring than those that are widowed late in the incubation phase (Lyon et al. 1987).

Another kind of test of the mate‐assistance hypothesis for social monogamy comes from a comparative study of a group of European warblers in the genus Acrocephalus. In this genus, monogamous species tend to occupy poor habitats where rearing offspring is difficult, whereas polygynous species occur in resource‐rich environments (Leisler et al. 2002). These trends suggest that, when social monogamy has evolved in this group, it is because having a helpful male partner substantially increases the production of surviving offspring when birds occupy a challenging habitat.

Generally speaking, findings of this sort indicate that paternal males derive benefits from their social monogamy, although it often remains difficult to tell whether these benefits (including reduced partner infidelity and increased offspring production) really outweigh the overall costs (a smaller number of females inseminated).

9.5.2 Polygyny: the puzzle of female participation

It makes intuitive sense from the female perspective to have a socially monogamous, paternal male around to assist in various ways, perhaps especially in the feeding of nestlings and fledglings. In the European Starling (Sturnus vulgaris) and in other species such as the House Wren (Troglodytes aedon) (Soukup and Thompson 1998), females lose paternal care for their offspring when their social partner acquires an extra‐pair mate (Fig. 9.15). Therefore, in the starling and other socially monogamous species, females often react aggressively toward prospecting females that enter their territory. In fact, female European Starlings and House Wrens have been observed destroying the eggs of other females that attempt to breed with their partner. In so doing, a female can try to force monogamy on her partner, making it advantageous for him to care only for her own brood. Given the successful attempts of females of many bird species to monopolize the paternal care offered by a social partner (Slagsvold and Lifjeld 1994), it seems odd that in other species females accept a polygynous male even though the female must share her male’s parental care with his other sexual partners or even lose his assistance altogether.

Fig. 9.15 Offspring gain a developmental benefit from attentive fathers. When male European Starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) contribute to incubation, eggs spend more time at temperatures optimal for development (blue line) compared with instances in which only the female incubates (red line).

(From Reid et al. 2002. Reproduced with permission from Springer Science + Business Media. Photograph by Carrie L. Johnson.)

Of course it is possible in some cases that polygynous males may not alert some partners that they have already acquired another mate. For example, this “deceit hypothesis” may apply to the European Pied Flycatcher (Ficedula hypoleuca), in which males that have established a territory and attracted a mate sometimes attempt to acquire a second territory with a second female. These dual territories can be up to 3 kilometers away from one another, and the secondary female may not know that her new‐found male already has a mate elsewhere. Once she begins to lay eggs and incubate, her now polygynous partner typically returns to his primary mate, whose offspring will be the beneficiaries of all or most of his parental care. The secondary female and her brood lose out (Alatalo and Lundberg 1984). Perhaps secondary females are not really deceived by their partners but instead are simply making the best of a bad situation arising from their late arrival on the breeding grounds. Alternatively, they may voluntarily accept a polygynous male whose special attractiveness increases the odds that they will produce sons that inherit his appeal, thereby increasing their number of grand‐offspring (the sexy son hypothesis discussed earlier in the chapter) (Huk and Winkel 2006).

In any event, polygyny is not surprising from the male perspective. Males that can inseminate more than one female successfully typically fertilize more eggs than they would if they restricted themselves, or were restricted by aggressive partners, to a single mate. What conditions enable males to practice polygyny successfully despite the apparent costs to their mates?

Consider the Montezuma Oropendola (Psarocolius montezuma), a Central American species in which several to many females build their long hanging nests from the same tree (Webster 1994) (Fig. 9.16). Under these circumstances, some males can acquire a number of mates by monopolizing the group of females at a nest tree. Indeed, males compete with one another to prevent rivals from approaching the nest tree. Successful males presumably gain more through polygyny than they could by guarding one female or assisting a single partner in the rearing of her brood. To the extent that powerful territorial males can pass their attributes on to their sons, females could gain by accepting top males as their partners, thereby increasing the odds of having reproductively successful sons. The result of male competition for pre‐existing groups of females has been labeled female defense polygyny, a mating system that is common in mammals but relatively rare among birds.

Fig. 9.16 Montezuma Oropendula (Psarocolius montezuma) nest colony. To court females, males spread their wings and make a series of loud trickling‐sounding calls before hanging upside‐down near one of many pendulous nests.

(Photograph by William David Grimes.)

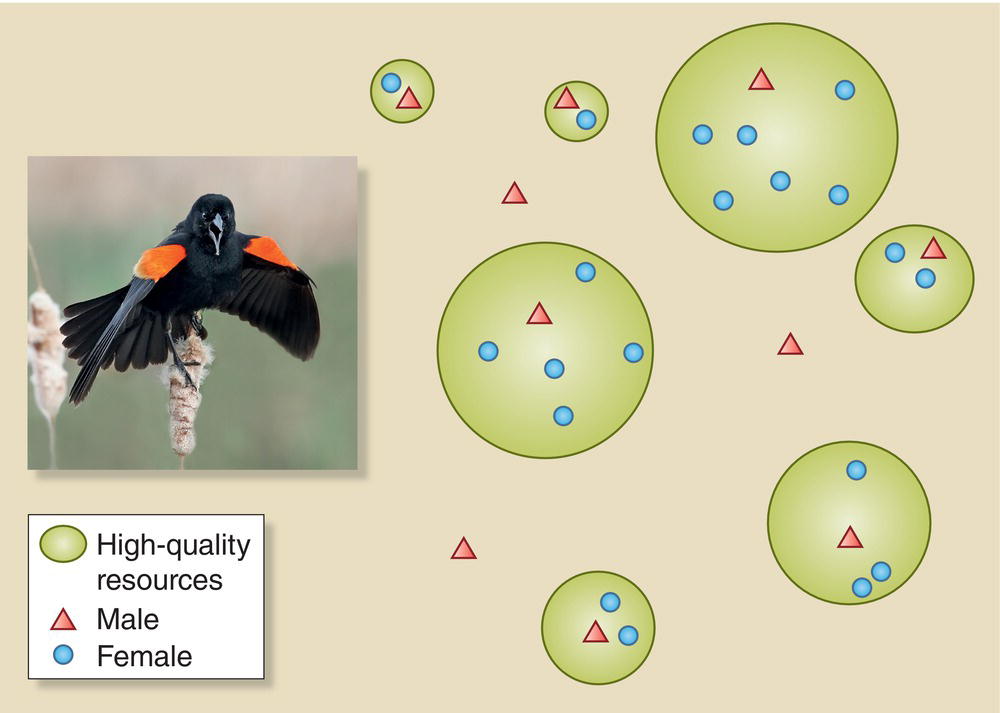

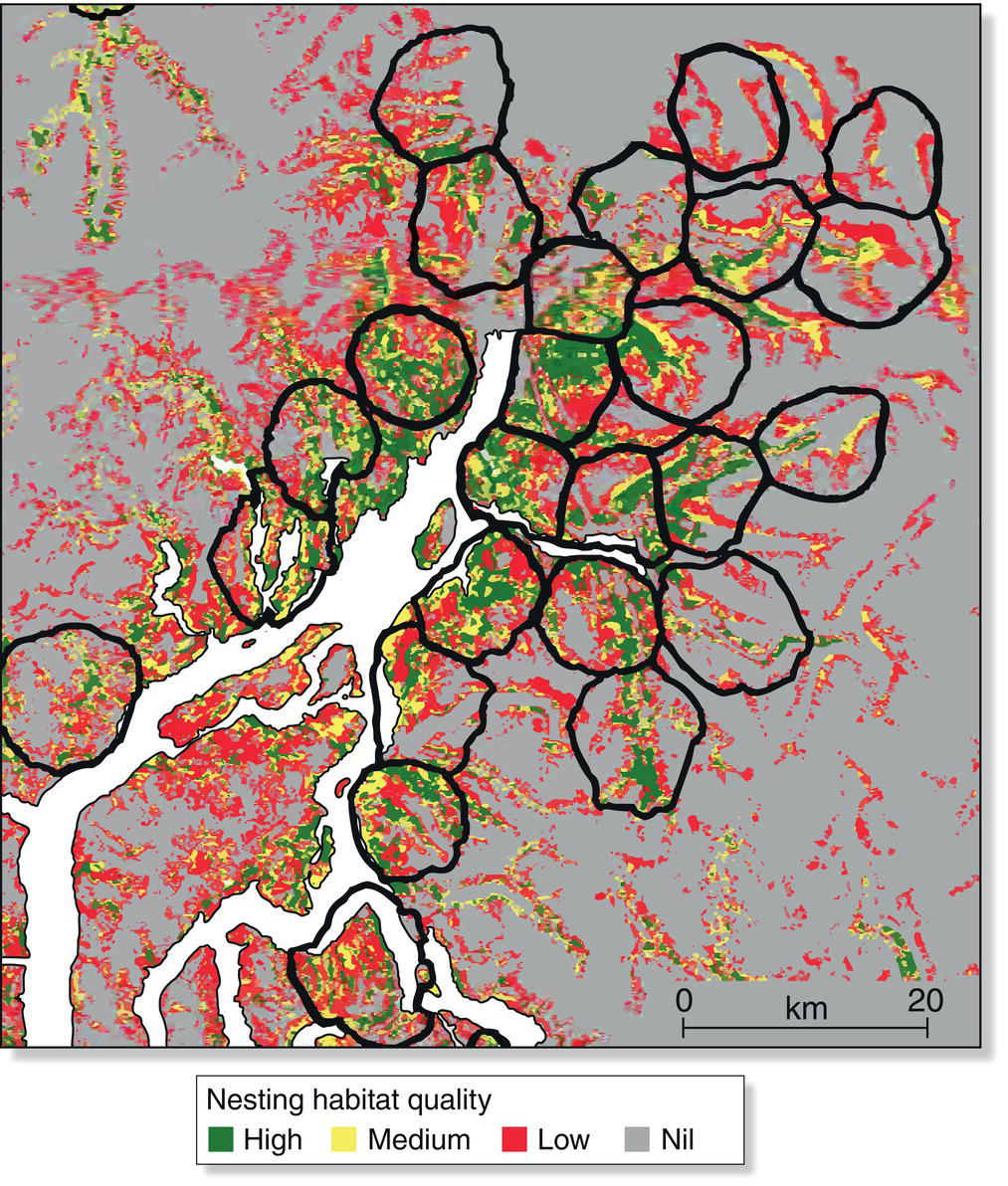

A far more common kind of avian polygyny can occur if some males invest in the defense of resources rather than in direct parental care. Resource defense polygyny is practiced, for example, by the Red‐winged Blackbird (Agelaius phoeniceus) of North America (Fig. 9.17). As males divide up a marsh or abandoned farm field into a set of breeding territories, some individuals may be able to acquire real estate of exceptional value; that is, a territory with unusually large amounts of insect food that could be supplied to nestling blackbirds, or one with unusually safe, well‐concealed nest sites. Unmated female Red‐winged Blackbirds then can be faced with options that include joining an unpaired male who holds a territory with only modest resources or joining an already‐paired male whose territory is of considerably higher quality. Under these circumstances, it can pay for the female to enter into the polygynous arrangement if the difference between the territories of the two males is sufficiently great (Orians 1969).

Fig. 9.17 Resource defense polygyny. This mating system arises in Red‐winged Blackbirds (Agelaius phoeniceus) and other species that occupy a patchy nesting habitat with limited resources. Males (red triangles) occupying superior territories with better nest sites and resources (green circles) generally secure more mates (blue circles), while males on inferior territories attract few or none. Some males do not have territories at all as good habitat is limited. This mating system offers a trade‐off between resources and parental care: females on better territories have access to more food but get less help from their mate.

(© Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Photograph by Nick Saunders.)

This explanation for why female Red‐winged Blackbirds often accept polygynous partners has been tested experimentally. Researchers gave some males extra cattail reeds placed over water and others a reed supplement of the same size placed over dry land. Faced with a choice between a safer over‐water location in a territory that already had attracted one female and a less safe one owned by a male without a mate, the female blackbirds in this study almost universally chose the safer over‐water option, even though they had to share a territory with another female and also share whatever parental care was offered by their partner (Pribil and Searcy 2001).

9.5.3 Lek polygyny

The most striking form of polygyny exhibited by birds and other animals occurs at leks, places where males gather in display arenas or guard small display territories, often very close to those of their rivals, in order to court and mate with visiting females. The polygynous males are the fortunate ones that acquire multiple sexual partners during one breeding season. Although only a small fraction of bird species have a lek‐based mating system, this mating behavior has evolved independently in many avian lineages. Lekking species include the Black Grouse (Tetrao tetrix) and Great Snipe (Gallinago media) mentioned earlier in this chapter, as well as some other grouse, sandpipers, and hummingbirds. Lekking also has evolved among the songbirds, where it is exhibited by many manakins, birds‐of‐paradise, bowerbirds, cotingas, and tyrant flycatchers, among others. In leks, the male’s display territory does not contain any resource of direct value to the female: it has no nesting site, no food—only the male himself. Because the only thing a male has to offer a given female is his genes, sexual selection via male–male competition (Chapter 3) generally is acute in lekking species, which in turn have evolved some of the most dramatic and spectacular physical ornaments and display behaviors.

Leks can have many spatial configurations. Males in some species gather only in loose aggregations; in these exploded leks males usually display in the same general area but not necessarily within view of one another. The Satin Bowerbird (Ptilonorhynchus violaceus) (Box 9.01) is an example of this kind of lekking species. Males of that species generally build their bowers about 250–300 meters apart (Reynolds et al. 2009).

At a classic lek, the displaying males are very close together and spend considerable time and energy behaving aggressively toward one another as they compete for spots within the lek favored by visiting females. Black Grouse offer an example of this sort of mating system. In this European species, 10 or 20 males may attend a single display site, with the nearest neighbors spaced only a few meters apart. When female birds visit classic leks, they generally watch the males interacting and displaying before sometimes moving toward a particular individual. As a female approaches a male, he responds with elaborate courtship, often combining both visual and acoustic components. These courtships often involve demonstrations of the extraordinary feather ornaments that many lekking species possess: Greater Sage‐Grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus) in North America fan their tails and puff out the breast feathers that surround their brilliantly orange vocal sacs; Victoria’s Riflebirds (Ptiloris victoriae) in eastern Australia wave their extended wings from one side to the other in a carefully timed ritual; and the Blue Bird‐of‐Paradise (Paradisaea rudolphi) of New Guinea hangs upside down from a limb while shimmering a fan of blue body feathers (Fig. 9.18).

Fig. 9.18 Blue Bird‐of‐Paradise (Paradisaea rudolphi). Males of this species hang upside down and fan out their feathers as part of a lekking courtship display.

(Photograph by Fabien Pekus.)

Subtle differences among males may have big effects on the reproductive success of lekking individuals. In the male Golden‐collared Manakin (Manacus vitellinus), the brightness of the yellow collar greatly affected male reproductive success in one population studied in Panama (Fig. 9.19). Here, as in other brilliantly plumaged birds, the intensity of feather colors is linked to physiological condition, with brighter males tending to be in better physical condition (Stein and Uy 2006). Perhaps because they are in such good shape, bright males may be better performers for visiting females. Indeed, some male Golden‐collared Manakins are faster than others in getting their “beard” of throat feathers extended upon landing on a perch after a period of energetic bouncing from a sapling to the ground and back. In one study, the fastest males resumed their extended throat feather pose in 43 milliseconds, but the slowest males required 63 milliseconds to adopt the correct posture (Schlinger et al. 2001). Needless to say, these and other behavioral differences are tiny in absolute terms, but some ornithologists believe that female manakins can detect the differences as males run through their routines and that they use this information to make decisions about who does and who does not get to mate.

Fig. 9.19 Golden‐collared Manakin (Manacus vitellinus). Males display by rapidly flaring out their golden throat feathers. Females assess males based on their display, throat color (which indicates condition), and position in the lek.

(Photograph by Marie Read.)

There is no question that behavioral differences among males play a critical role in female mate choice in other lekking species. For example, the way in which male Satin Bowerbirds engage in courtship clearly determines their success with females. Males that dance very vigorously, even aggressively, before the female are more likely to mate than those whose actions are less intense. In addition, males that are able to moderate the degree to which they charge at the female do better than males less capable of adjusting their display in response to whether the visiting female flinches, crouches down, or remains in place during a male performance (Patricelli et al. 2002).

From the male’s perspective, lekking represents an investment in courting many females with the possibility of fathering a great many offspring. At most leks, most or all females choose the same male to inseminate them, conferring very high reproductive success on the favored male. The corollary is that the reproductive output of the other, less attractive males is very low (during a given year). For example, at leks of the Golden‐collared Manakin in Panama, three to eight males competed for the attention of visiting females, but only one or two of these males secured almost all the copulations during one breeding period (Schlinger et al. 2008). This pattern of great variation in mating success among individuals is termed high reproductive skew (the alternative pattern where all members of a given sex have equal mating success is termed low reproductive skew). One review of this kind of variation among lekking bird species found that 10–20% of the males at leks customarily account for 70–80% of all matings (Mackenzie et al. 1995) (Box 9.08).

Given that a tiny fraction of the males at most leks monopolize most mating opportunities in any given year, what can the other males do to secure at least some copulations? Males of some species have evolved a behavioral flexibility in which low‐status males employ alternative tactics that help them make the best of a bad situation. For example, at study sites in Sweden, Great Snipe (Gallinago media) males that are excluded from prime territories by highly dominant, highly attractive males sometimes establish territories immediately adjacent to the sites held by their superior rivals. These satellite males occasionally may get a chance to intercept and mate with a female headed toward a prime male on his super‐territory (Höglund and Lundberg 1987).

Another tactic has evolved in the Ruff (Caladris pugnax), a large Eurasian sandpiper, in which actively lek‐displaying males have brightly colored plumage in a variety of color morphs. Other Ruff males lack this distinctive plumage and instead mimic the drab appearance of females. By posing as females, these sneaker males may be permitted to enter a very attractive male’s domain. Yet a third kind of male adopts male plumage but does not hold a territory on the lek; these satellite males linger on the periphery and attempt to mate with females as they are passing by (Fig. 9.20). All three of these strategies are sometimes successful, though the lekking males generally sire the most offspring (Jukema and Piersma 2005).

Fig. 9.20 Reproductive morphs of male Ruffs (Calidris pugnax). Satellite males do not engage in lekking behavior or territory defense. Instead, they linger near the periphery of the lek and try to mate with females as they pass through, or when the lekking males are busy displaying or fighting. Here, the satellite (left) was detected and must suffer the consequences as the dark‐plumed male (right) fiercely defends his territory.

(Photograph by Dominique Halleux.)

Still another tactic that males can use under certain circumstances is to associate with relatives who may concede a few matings to their brothers or nephews. In the Satin Bowerbird, for example, males tend to build their bowers fairly close to that of a relative. These birds avoid attacking the bowers constructed by relatives in favor of going after those owned by unrelated males (Reynolds et al. 2009). The generous behavior exhibited by relatives toward one another makes evolutionary sense in the context of kin selection (Chapter 3). When males help relatives, they help the portion of their own genes present in these other kin.

A final reason why low‐ranking males may participate in lek mating systems requires us to take a long‐term perspective. Males may copulate rarely, if ever, when they are low‐ranking members of a lek, but if they are fortunate to survive a number of years, they eventually may secure an alpha position and all the mating opportunities that go with being a dominant male. However, only males that persistently participate in the lek have a chance to move up the ladder to the top. This argument has been demonstrated to be correct for lekking Long‐tailed Manakins (Chiroxiphia linearis). In this species, some males display to help others attract females. The subordinate males often wait years for the payoff that comes when the more dominant individual dies, enabling the patient helper to move up to the top spot. Only then do they have a chance to leave copies of their genes to the next generation (McDonald and Potts 1994).

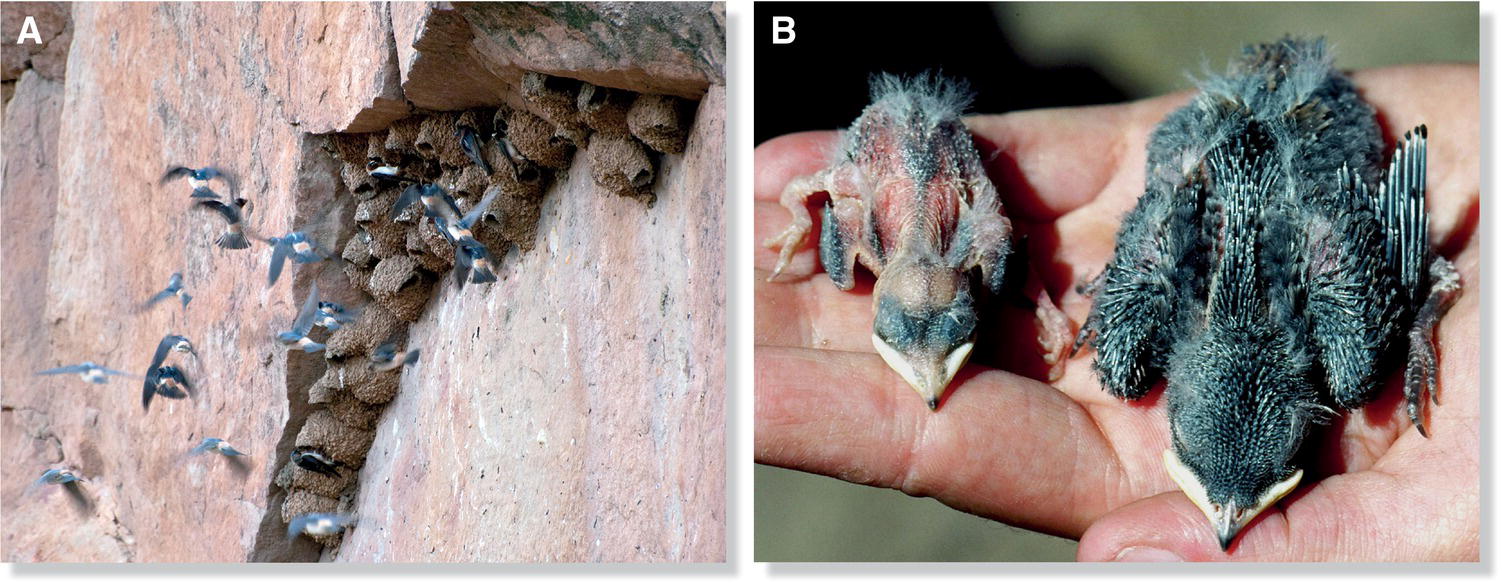

9.5.4 Absence of male parental care and the lek paradox

Male Golden‐collared Manakins (Manacus vitellinus) spend many months each year at their lek, with individual manakins returning year after year to exactly the same set of saplings where they reconstruct their display arena. Should a male be so fortunate as to mate, he does not accompany that female when she departs; instead he returns to the dance floor to continue his efforts to persuade other females to copulate with him. The mated females are left to do the hard work of nest building, incubation, nestling feeding, and fledgling chaperoning completely on their own.

Why do male manakins, and males of the many other lekking species, not help their sexual partners rear their offspring? Why do female birds choose to mate with males whose only contribution to the next generation is their sperm? One possibility is that lekking tends to evolve in species in which biparental care is not essential or even is harmful, and hence male care would do little or nothing to boost the reproductive output of either the male or female. This possibility could apply to species such as grouse and sandpipers with precocial offspring (Chapter 11) that are not fed directly by their parents after hatching. Biparental care may be a handicap in some tropical forests and other situations where predators that raid nests are abundant, and where the increased number of visits by an attendant male would increase the chances of a predator finding the nest.

Given that lekking males and their territories provide no parental care or food for females or their offspring (Höglund and Alatalo 1995), it seems reasonable to assume that female mate choice in these birds probably revolves around securing good genes, although, as previously mentioned, females also might benefit from mating with healthy, non‐parasitized, non‐infectious partners. If the ecology of the species is such that male assistance either has little benefit for females or provides few benefits for males, then females may be forced to participate in a system in which the best that they can do is to choose a healthy mate or one with good genes.

The good genes theory, however, does generate a major puzzle, which goes as follows: if females select mates on the basis of their genetic makeup, then in relatively short order, genetic variation in the male population will be drastically reduced. Why? Because if only a small group of males gets to pass on their genes, soon the gene pool will be filled with the particular genetic variants possessed by the small number of popular males of the past. In the absence of hereditary variation among males, females gain nothing by being choosy. But in avian leks today, females of most species continue to be highly selective about their choice of sexual partners. This conundrum is known as the lek paradox.

Many solutions to this paradox have been suggested (Kotiaho et al. 2008), most of which are based on rather arcane mechanisms that could maintain genetic variation in a population even when females consistently choose males with a particular genetic makeup. For example, if female choice favors males that are heterozygous (that is, males that have two different forms of many different genes rather than two copies of the same allele of these genes), then by choosing the most intrinsically diverse males, females select for the maintenance of genetic variation among males over time.

9.5.5 Polyandry: why do males accept polyandrous mates?

Another puzzling feature of avian mating systems involves the rare cases in which males voluntarily participate in polyandrous mating systems in which males mate with females that have more than one sexual partner. Particularly surprising are the instances in which several males act as helpers to the same female, whose sexual favors they must share. In the Galápagos Hawk (Buteo galapagoensis), for example, as many as eight unrelated males may pair bond with a single female on a territory, which all defend jointly. The polyandrous female copulates with all her partners more or less equally, meaning that the males are essentially taking part in a fertilization lottery (DeLay et al. 1996). Why might male Galápagos Hawks tolerate this competition within their territory rather than trying to defend a territory on their own? One possible answer is that suitable hawk territories are in very short supply on some islands in the Galápagos, and generally there are many males competing for each suitable location. If several males join together and cooperate in defending valuable real estate that a female will accept, they can win out over single males that try to defend a solo territory. Under these constraining circumstances, a male in a group has at least some possibility of fertilizing an egg and thus does better than a solo male without a suitable territory.

The Galápagos Hawk is unusual but not unique among birds in engaging in social polyandry, with more than one male behaviorally pair bonded with the same female. An even better known example of polyandry in birds involves the phalaropes, three species of small shorebirds that breed primarily in the Arctic. In the phalaropes, a sex‐role reversal has occurred so that females compete aggressively with one another for mates while courting males (Fig. 9.21). The males they court in turn assume all parental duties once the eggs have been laid in their nests. Some female phalaropes achieve sequential polyandry by abandoning an initial partner after supplying him with a clutch and then securing another mate that will care for a second batch of eggs. When polyandrous females leave their partners, the male’s only good option is to continue to accept the parental role because he can incubate a clutch of eggs successfully by himself. Later, the newly hatched, precocial chicks feed themselves on an abundance of insect food (Reynolds 1987). Males that retaliate against female abandonment by also abandoning their nests would leave no descendants at all. As we might predict given the unusually high male parental investment by phalaropes, genetic studies have shown that only a very small percentage (<2%) of all phalarope chicks are sired by a male other than their caretaker (Schamel et al. 2004). The paternal male phalarope thereby enjoys a direct genetic payoff in return for his attentiveness to his nest.

Fig. 9.21 Sex‐role reversal in Wilson’s Phalaropes (Phalaropus tricolor). In this species, females (right) exhibit brighter plumage and aggressively compete for males (left), which incubate eggs and provide parental care without female help.

(Photograph by Larry Jordan.)

One of the ways male Red Phalaropes (Phalaropus fulicarius) increase the odds that they will produce offspring with their own genes is to increase the frequency with which they copulate with their one partner during her fertile period (Schamel et al. 2004). Male birds that provision offspring also generally make this activity contingent upon sexual access to the mother of those offspring, a fact that some polyandrous females use to “encourage” paternal behavior on the part of all their mates. For example, the Dunnock (Prunella modularis) is a drab little European bird that exhibits a rich diversity of mating systems (Davies 1985). In some cases, a polyandrous female lives with two male partners with whom she copulates at frequent intervals. Socially polyandrous Dunnock females tend to solicit matings from the male that thus far has had fewer copulations, thereby activating the male’s psychological mechanisms that push him (unconsciously of course) toward paternal behavior when the nestlings have hatched and need to be fed. Because copulation frequency correlates with egg fertilizations, males that mate often with a female are likely to have sired at least some of her offspring. A polyandrous female that skillfully partitions matings between two males gains two caretakers for her progeny, a clearly advantageous consequence for the female in this species in which the additional paternal care increases the number of offspring they can rear in a breeding season.

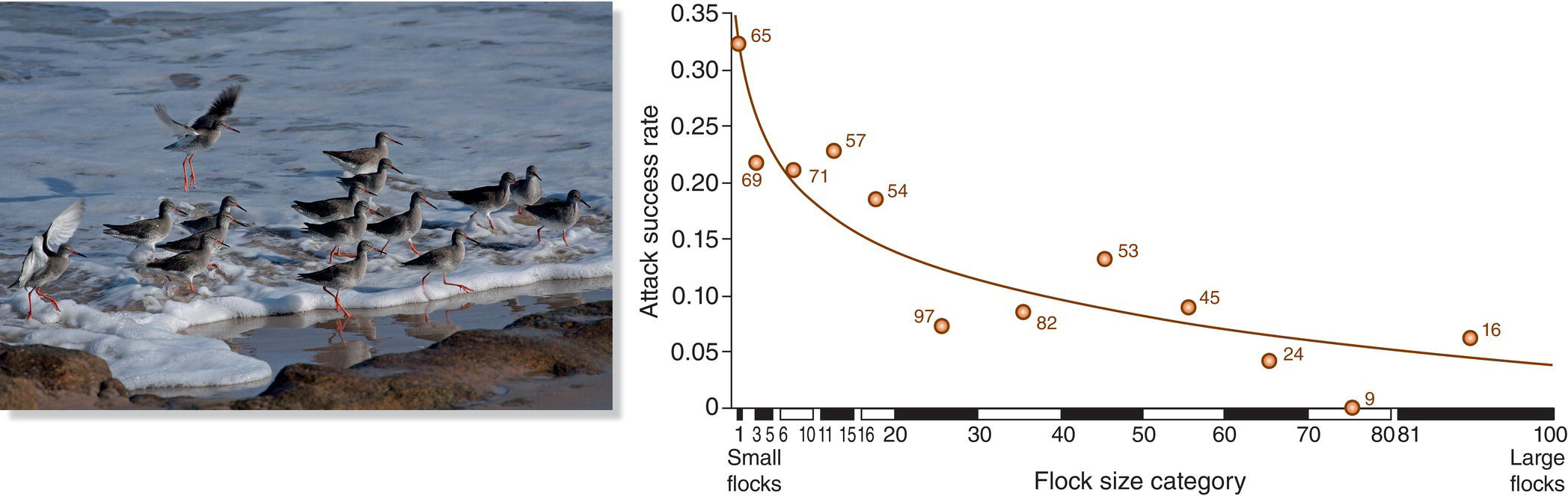

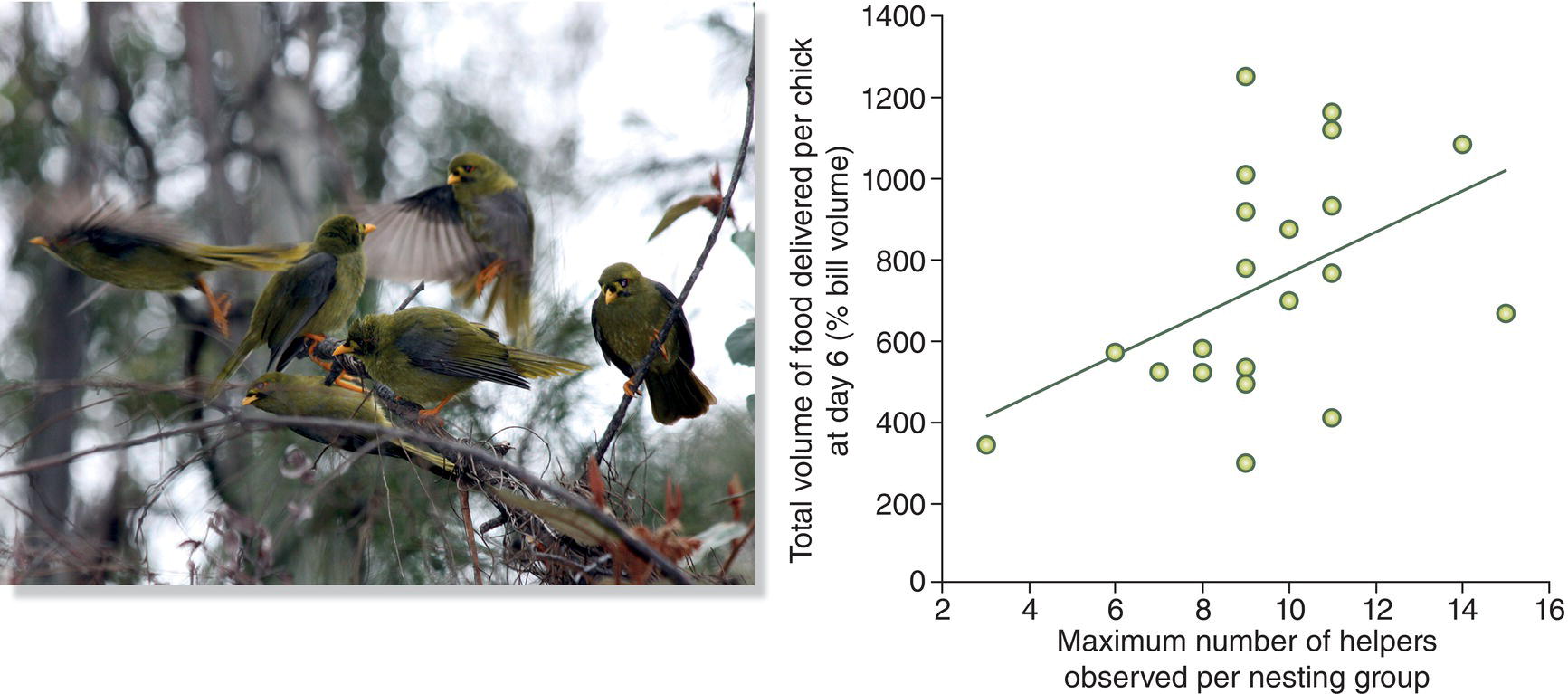

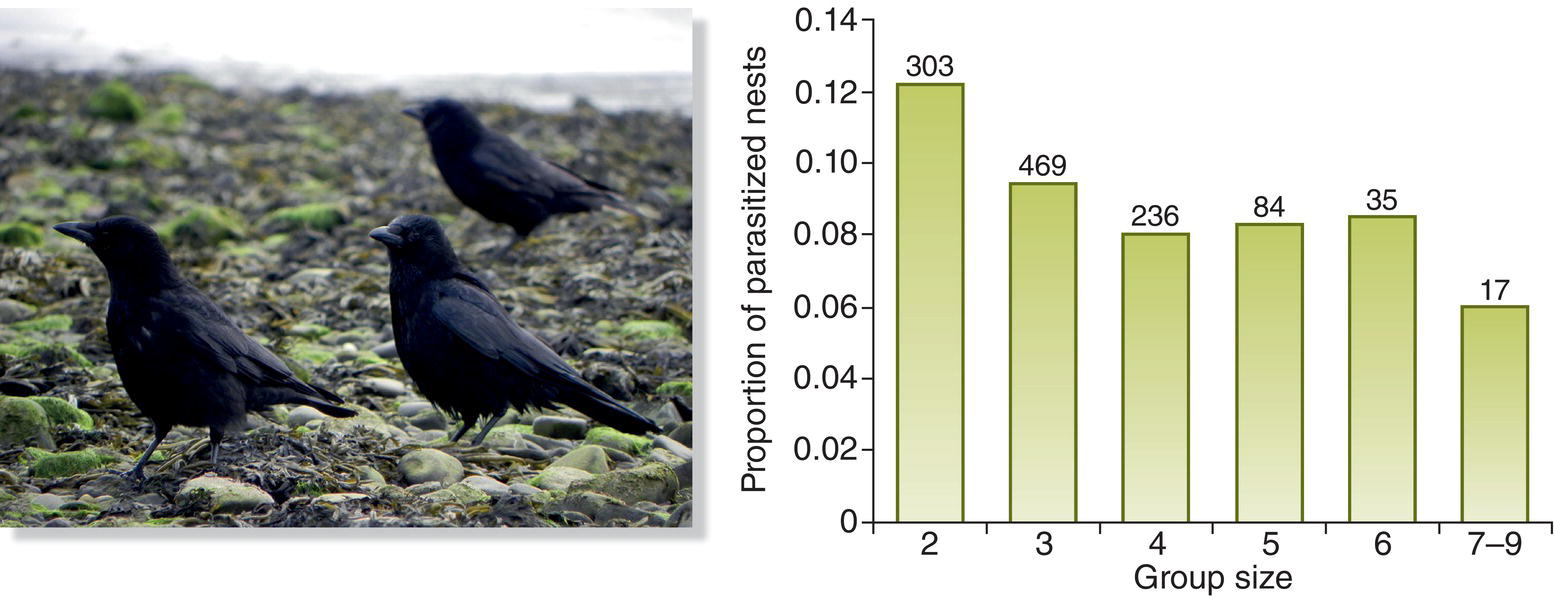

When a polyandrous female gets her partners to care for her offspring, she derives an obvious material benefit from copulating with more than one male. However, many socially monogamous females solicit extra‐pair copulations from males that cannot or will not be available when the eggs hatch. The added parental care hypothesis for polyandry does not apply to these situations. A reproductive benefit that could lead females to mate with multiple partners is that receiving sperm from several males provides fertility insurance against the possibility that their social partner’s sperm are inadequate or defective. Studies of a few species have found that a small but measureable percentage of male songbirds are infertile; the mates of these individuals certainly would benefit by receiving sperm from a fertile extra‐pair partner. Thus, although 2–4% of Eurasian Blue Tit (Cyanistes caeruleus) and related Great Tit (Parus major) males tested in one study were infertile, the females mated to these individuals nonetheless produced six to nine offspring, demonstrating that their extra‐pair copulations provided them with plenty of viable sperm (Krokene et al. 1998).