Musculoskeletal/Rheumatology

ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY

Bone: Bone formation begins with osteoblasts producing osteoid, which is composed primarily of type I collagen. The osteoid matrix acts as a scaffold onto which minerals from the blood deposit to form hydroxyapatite crystals and eventually rigid bone. Osteoclasts migrate from the bone marrow and are responsible for bone remodeling. Remodeling functions to repair bony microdamage and maintain calcium homeostasis. Remodeling is under hormonal control, so when calcium is high, calcitonin is released to inhibit osteoclast function directly. When calcium is low, parathyroid hormone (PTH) is released, which induces osteoblasts to activate osteoclasts. Osteoclasts then resorb bone and release calcium into the circulation. Osteoblasts will eventually produce more osteoid to replace the resorbed bone.

Mnemonic: OsteoBlasts Build bone osteoClasts Consume bone. Calcitonin “tones down” calcium.

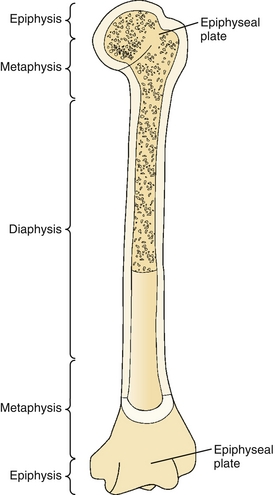

Long bone: Weight-bearing bones important for skeletal mobility, such as the tibia and femur. These bones grow via endochondral ossification (cartilage-dependent growth) at the epiphyseal plate (growth plate). Long bones are divided into the epiphysis, epiphyseal plate, metaphysis, and diaphysis (Fig. 12-1).

Figure 12-1 A long bone can be divided into the epiphysis, epiphyseal plate, metaphysis, and diaphysis. (From Rakel RE, Rakel DP. Textbook of Family Medicine. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2011.)

Flat bone: These bones provide broad flat surfaces for muscle attachment or protection. Examples include the pelvis and skull. Growth is through intramembranous ossification (cartilage independent growth).

Cartilage: Produced by chondrocytes; composed primarily of type 2 collagen, ground substance, and elastin. Hyaline cartilage provides a compressible, low-friction, high-strength material ideal for cushioning joints. Elastic cartilage contains relatively more elastin and forms structures such as the pinna of the ear and epiglottis. Because cartilage is avascular, chondrocytes must rely on diffusion to obtain nutrients. Cartilage has only a minimal capacity for regeneration because of the low numbers of highly specialized chondrocytes.

Ligament: Fibrous connective tissue composed of collagen that connects bone to bone.

Fascia: Fibrous connective tissue composed of collagen that connects muscle to muscle.

Tendon: Fibrous connective tissue composed of collagen that connects muscle to bone. The points at which tendons insert into bone are called entheses.

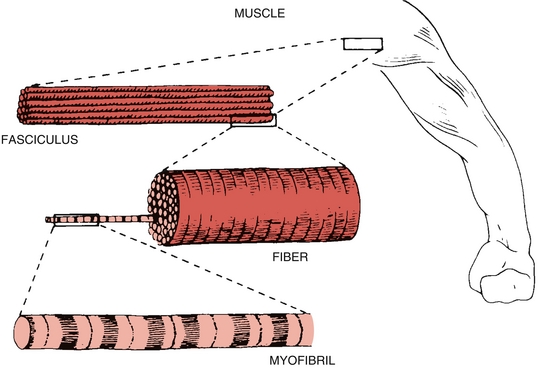

Skeletal muscle: Voluntarily controlled muscle tissue innervated by the somatic nervous system. Individual muscles are composed of bundles of fascicles, which are comprised of bundles of muscle fibers. The muscle fibers are the “muscle cells” referred to as myocytes. At the subcellular level, muscle fibers contain bundles of myofibrils (Fig. 12-2). Each myofibril consists of proteins (e.g., actin, myosin) that form thick and thin filaments that repeat along the myofibril. These repeating units are called sarcomeres.

Figure 12-2 Constitutive parts of skeletal muscle. (From Berne MN, Levy BA, Koeppen BM, Stanton RM. Physiology. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2003.)

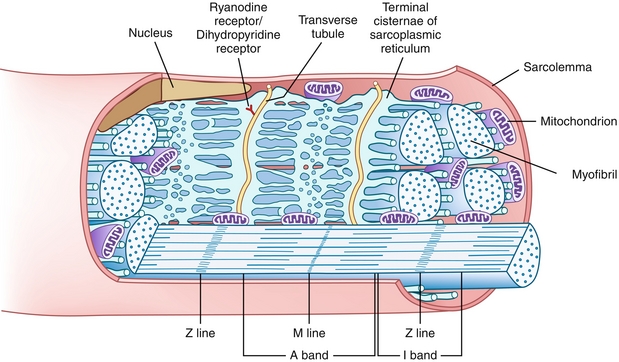

Sarcomere: This basic contractile unit of muscle is composed of actin and myosin (Fig. 12-3). The A band contains thick myosin filaments. The M line bisects the center of the A band and contains proteins that link the myosin filaments together. The I bands fall on either side of the A band and contain thin actin filaments. Contraction occurs when the actin and myosin fibers overlap in the presence of Ca2 + and ATP, allowing cross-bridge cycling.

Figure 12-3 Sarcomere, the basic contractile unit of muscle composed of actin and myosin. (From Gartner LP, Hiatt JL. Color Textbook of Histology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007.)

Type 1 fibers: Slow twitch muscle is red because of its dense concentration of capillaries, mitochondria, and myoglobin. These fibers specialize in the aerobic metabolism needed for sustained muscle contractions.

Type 2 fibers: Fast twitch muscle is white because of relatively sparse mitochondria and myoglobin. These fibers specialize in anaerobic bursts of activity for fast, forceful muscle contractions.

Action potentials release acetylcholine from the presynaptic neuron into the neuromuscular junction.

Action potentials release acetylcholine from the presynaptic neuron into the neuromuscular junction.

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors open ligand-gated ion channels, allowing Na+ to rush in and generate a depolarizing endplate potential.

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors open ligand-gated ion channels, allowing Na+ to rush in and generate a depolarizing endplate potential.

Transverse tubules (T-tubules), which form invaginations in the sarcolemmal (muscle cell) membrane, carry the depolarizations deep into the myofibers to cause a conformational change of the voltage-sensitive dihydropyridine receptors. Dihydropyridine receptors are in the sarcolemmal membrane, but thanks to the T-tubules, are positioned next to the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR).

Transverse tubules (T-tubules), which form invaginations in the sarcolemmal (muscle cell) membrane, carry the depolarizations deep into the myofibers to cause a conformational change of the voltage-sensitive dihydropyridine receptors. Dihydropyridine receptors are in the sarcolemmal membrane, but thanks to the T-tubules, are positioned next to the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR).

The dihydropyridine receptor’s conformational change opens the ryanodine receptor on the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) and allows the large Ca2 + stores of the SR to diffuse into the cytoplasm.

The dihydropyridine receptor’s conformational change opens the ryanodine receptor on the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) and allows the large Ca2 + stores of the SR to diffuse into the cytoplasm.

Calcium binds troponin C, causing a conformational change of tropomyosin and exposing the myosin-binding site of actin.

Calcium binds troponin C, causing a conformational change of tropomyosin and exposing the myosin-binding site of actin.

Myosin heads can now form cross bridges with actin to allow cross-bridge cycling (Fig. 12-4).

Myosin heads can now form cross bridges with actin to allow cross-bridge cycling (Fig. 12-4).

Figure 12-4 Cross-bridge cycling and muscle contraction of skeletal and cardiac muscle. (From Costanzo LS. Physiology. 4th ed. New York: Elsevier; 2009.)

As long as Ca2 + is bound to troponin and ATP is present, cross-bridge cycling will continue. Once the Ca2 + ATPase sequesters Ca2 + back in the SR, there is no longer sufficient Ca2 + to bind troponin C. Tropomyosin then returns to its resting position, blocking the formation of actin-myosin cross-bridges, and resulting in muscle relaxation. If, on the other hand, Ca2 + remains present and ATP is absent, the muscle will enter a state of rigor (prolonged contraction).

As long as Ca2 + is bound to troponin and ATP is present, cross-bridge cycling will continue. Once the Ca2 + ATPase sequesters Ca2 + back in the SR, there is no longer sufficient Ca2 + to bind troponin C. Tropomyosin then returns to its resting position, blocking the formation of actin-myosin cross-bridges, and resulting in muscle relaxation. If, on the other hand, Ca2 + remains present and ATP is absent, the muscle will enter a state of rigor (prolonged contraction).

Smooth muscle: Nonstriated muscle under involuntary control of the autonomic nervous system. Smooth muscle provides vascular tone within blood vessels and is the contractile force for involuntary movements throughout the body including the gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and respiratory tracts.

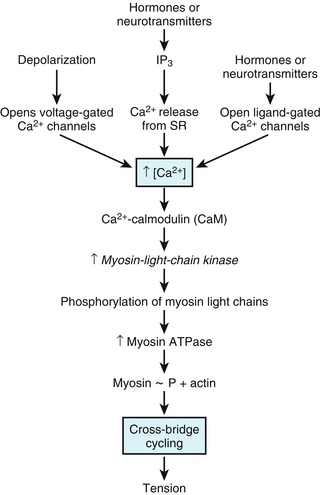

Smooth muscle contraction (Fig. 12-5):

Figure 12-5 Smooth muscle contraction. (From Costanzo LS. Physiology. 4th ed. New York: Elsevier; 2009.)

Action potentials depolarize smooth muscles, which open voltage-sensitive Ca2 + channels in the sarcolemma.

Action potentials depolarize smooth muscles, which open voltage-sensitive Ca2 + channels in the sarcolemma.

Ca2 + flows into the cell down its concentration gradient and binds calmodulin.

Ca2 + flows into the cell down its concentration gradient and binds calmodulin.

The Ca2 +calmodulin complex activates myosin light-chain kinase (MLCK).

The Ca2 +calmodulin complex activates myosin light-chain kinase (MLCK).

Activated MLCK phosphorylates myosin light-chains and increases their ATPase activity. Increased ATPase activity promotes cross-bridge cycling.

Activated MLCK phosphorylates myosin light-chains and increases their ATPase activity. Increased ATPase activity promotes cross-bridge cycling.

Myosin light-chain phosphatase eventually inhibits contraction by dephosphorylating myosin-light chains.

Myosin light-chain phosphatase eventually inhibits contraction by dephosphorylating myosin-light chains.

Individual smooth muscle cells are connected via gap junctions. This means one neuron can stimulate one smooth muscle cell, but an entire group of cells will depolarize and contract together.

Individual smooth muscle cells are connected via gap junctions. This means one neuron can stimulate one smooth muscle cell, but an entire group of cells will depolarize and contract together.

Cardiac muscle: Provides the contractile force of the myocardium and is composed of cardiac myocytes. Cardiac muscle has some properties of striated muscle and some of smooth muscle. Like skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle is striated, with sarcomeres of actin and myosin. Contraction is very similar to skeltal muscle contraction; Na+ influx induces depolarizations, which spread down T-tubules. Unlike skeletal muscle, however, depolarization of cardiac myocytes triggers extracellular calcium to flow inward through L-type calcium channels, which triggers ryanodine receptors to release Ca2 + from the SR (calcium-induced calcium release rather than dihydropyridine receptor–induced calcium release).

Cardiac muscle is like smooth muscle in that in is under involuntary control, and cells are linked together via gap junctions, which allow coordinated contraction.

Of note, cardiac muscle contains a unique type of troponin that functions in a similar manner to skeletal muscle troponin. This protein is leaked during cardiac myocyte damage and is very sensitive for detecting myocardial infarction.

Upper Extremity Anatomy

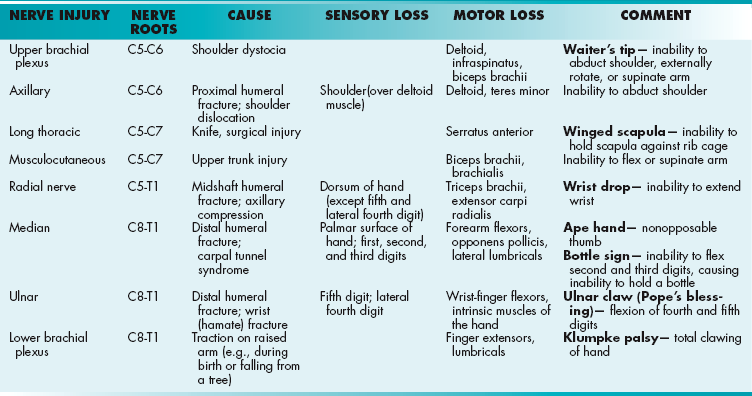

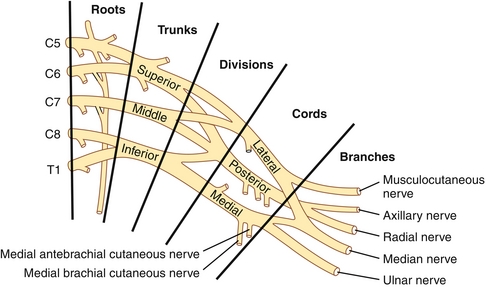

Brachial plexus: Bundle of nerve fibers responsible for sensory and motor innervation to the upper extremity. For the purposes of Step 1, it is valuable to know all roots, trunks, divisions, cords, branches, and associated lesions (Figs. 12-6 and 12-7). The muscular and sensory innervation of nerves should also be memorized (Table 12-1).

Figure 12-6 Roots, trunks, divisions, cords, and nerves of the brachial plexus. (From Miller RD: Miller’s Anethesia. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2005.)

Figure 12-7 Tips for memorizing the brachial plexus anatomy. A, Draw two headless arrows to the right and one headless arrow to the left. B, Draw a “W” on the right. C, Draw an “X” above and a “Z” below. D, Label C5-T1 and the major nerves.

Mnemonic: Robert Taylor Drinks Cold Beer.

Axillary nerve: Composed of nerve roots C5-C6, the axillary nerve provides sensory innervation from the shoulder (over the deltoid muscle). It innervates the deltoids and teres minor (shoulder abduction). Injury is usually from a proximal arm injury (e.g., proximal humeral fracture, shoulder dislocation).

Long thoracic nerve: Composed of nerve roots C5-C7, the long thoracic nerve innervates the serratus anterior muscle, which pulls the scapula forward with relation to the thorax. Damage causes winged scapula (Fig. 12-8). Injury may occur from a stab wound or surgical procedure.

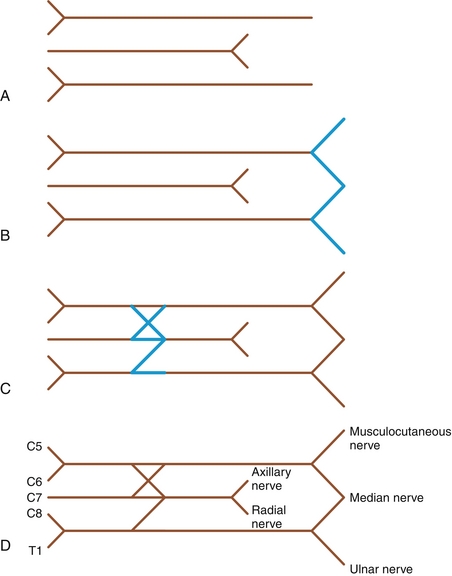

Figure 12-8 Sensory innervation to the hand. Consider tracing this image on your hand while you study. (From Marsland D, Kapoor S. Crash Course: Rheumatology and Orthopaedics, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2008.)

Musculocutaneous nerve: Composed of nerve roots C5-C7, the musculocutaneous nerve innervates the biceps brachii and brachialis muscle, which are responsible for elbow flexion and supination. Injury may occur because of forced stretching between the shoulder and head, damaging the upper trunk.

Median nerve: Composed of nerve roots C8-T1, the median nerve provides sensory innervation from the palmar surface of the hand and the first 3½ digits (Fig. 12-8). It innervates all the forearm flexors except the flexor carpi ulnaris (ulnar nerve). It is also responsible for flexion of the lateral digits (lateral lumbricals) and opposition of the thumb (opponens pollicis) muscle. Proximal injury causes inability to oppose the thumb, so-called ape hand. Distal injury causes the bottle sign (inability to flex second and third digits, resulting in inability to hold a bottle). Damage may be caused by fracture of the distal humerus or compression from carpal tunnel syndrome.

Ulnar nerve: Composed of nerve roots C8-T1, the ulnar nerve provides sensory innervation from the fifth digit and lateral fourth digit (Fig. 12-8). It innervates some of the wrist and finger flexors and the intrinsic muscles of the hand. Injury may be caused by fracture of the distal humerus or wrist (hamate) fracture.

Radial nerve: Composed of nerve roots C5-T1, the radial nerve provides sensory innervation from the dorsum of the hand, except the fifth and lateral fourth digits (Fig. 12-8). It is responsible for extension of the elbow (triceps brachii), wrist (extensor carpi radialis), and fingers. For this reason it is called the “great extensor” of the arm. Damage causes wrist drop. Injury may occur because of a midshaft humeral fracture or axillary compression (e.g., poorly fitted crutches or drooping one’s arm over the edge of a bar).

Brachial Plexus Syndromes

Winged scapula: Damage to the long thoracic nerve (C5-C7) causes paralysis of the serratus anterior muscles and a winged scapula because of inability to hold the scapula against the rib cage (Fig. 12-9). This injury is more pronounced when the patient presses the hands against a wall.

Figure 12-9 Winged scapula from damage to the long thoracic nerve. (From Douglas G, Nicol F, Robertson C. MacLeod’s Clinical Examination. 11th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005.)

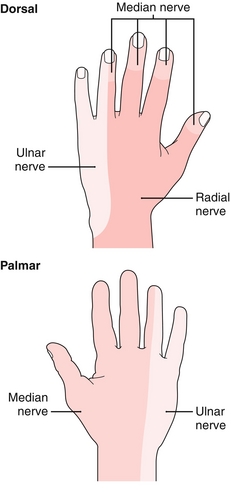

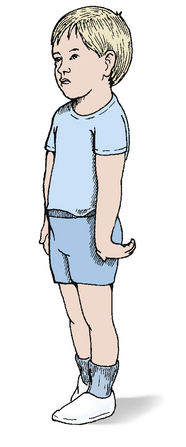

Erb’s palsy (Waiter’s tip): Damage to the upper brachial plexus roots causes weakness of abduction from deltoid paralysis (C5), weakness of external rotation from infraspinatus paralysis (C5), and loss of flexion from biceps paralysis (C6). The internal muscles of the hand are unaffected. Think of it as damage to the roots supplying the axillary and musculocutaneous nerves. The result is an arm that hangs limply by the side in extension and internal rotation (Fig. 12-10). Injury is usually caused by shoulder dystocia, in which the infant’s shoulder cannot pass the maternal pubic symphysis during birth. The result is traction on the shoulder, which damages the upper brachial plexus roots.

Figure 12-10 Erb’s palsy (waiter’s tip) from damage to roots C5-C6 of the brachial plexus. (From Dandy DJ, Edwards DJ. Essential Orthopaedics and Trauma, 5th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2009.)

Klumpke palsy: Injury to the lower roots of the brachial plexus (C8-T1) causes total clawing of the hand because of paralysis of the lumbricals and finger extensors (Fig. 12-11). Injury occurs when the raised arm is forcibly pulled upward, as may occur during birth or, for example, if a patient catches himself or herself by a branch while falling from a tree. Thus, the lesion can be remembered by the phrase “Klumpke the monkey fell from a tree.”

Figure 12-11 Klumpke palsy, total clawing of the hand caused by trauma to the lower brachial plexus. (From Pope BA, Painter MJ. Neurologic sequelae of birth, 2008 http://www.glowm.com/ section_view/item/198/recordset/18975/value/198.)

Thoracic outlet syndrome: Compression of the brachial plexus above the first rib, causing numbness and weakness of the affected arm, especially after protracted usage or reaching overhead (common in weight lifters). On physical exam, the patient’s radial pulse may disappear on tilting the head toward the unaffected side (Adson sign) because of compression of the subclavian artery at the thoracic outlet.

Peripheral Nerve Lesions of the Upper Extremity

See Table 12-1.

Ulnar claw (Pope’s blessing): Damage to the ulnar nerve at the medial epicondyle or wrist, causing lumbrical weakness and flexion (clawing) of fourth and fifth digits.

Wrist drop: Compression of the radial nerve results in unilateral wrist drop because the radial nerve innervates the finger and wrist extensors. Compression may be in the axilla because of the use of crutches or at the midshaft of the humerus because of a fracture. Lead poisoning can lead to wrist drop through its effect on the radial nerve. Wrist drop also classically occurs when a patient becomes drunk and falls asleep with his arm draped over the bar. This compresses the radial in the axilla and is called Saturday night palsy.

Ape hand (nonopposable thumb): Median nerve injury, causing weakness of the opponens pollicis muscle and inability to abduct or oppose the thumb.

Bottle sign: Distal median nerve injury causes weakness of the lateral lumbricals and inability to flex the second and third digits. Patients are therefore unable to hold a bottle.

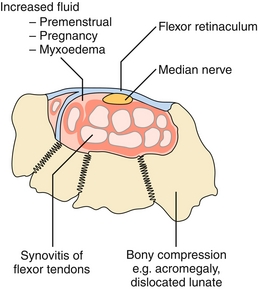

Carpal tunnel syndrome: The carpal tunnel is a narrow tunnel of the anterior wrist. The carpal bones form the floor, and the flexor retinaculum (transverse carpal ligament) forms the roof. The tunnel contains nine flexor tendons and the median nerve (Fig. 12-12). Compression of the median nerve causes pain and numbness in the lateral palmar surface of the hand. Chronic compression may also cause weakness of palmar abduction and thenar atrophy. Patients may have a positive Tinel sign (paresthesia with percussion of carpal tunnel) or Phalen maneuver (paresthesia with forced wrist flexion). Conservative treatment is a night splint. Medical treatment involves steroid injections. Surgical treatment, which is definitive, occurs when the flexor retinaculum is released. Anything that compresses the median nerve may cause this syndrome, including myxedema from hypothyroidism, fluid compression within the carpal tunnel (during pregnancy), compression from synovitis secondary to constant wrist flexion (during sleep or while typing), or inflammation (rheumatoid arthritis).

Lower Extremity Anatomy

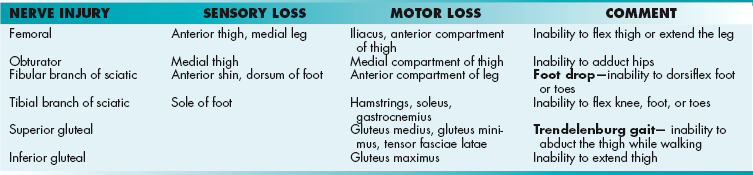

Lumbosacral plexus: Unlike the brachial plexus, it is probably not high yield to memorize the lumbosacral plexus in detail. The muscular and sensory innervation of major nerves should be known, however (Table 12-2).

Femoral nerve: Composed of nerve roots L2-L4, the femoral nerve provides sensory innervation to the anterior thigh and medial leg. It innervates the iliacus and all the muscles of the anterior compartment of the thigh (quadriceps and sartorius). It is therefore responsible for thigh flexion and leg extension (the motion of a high kick). Injury may occur because of fracture of the pelvis.

Obturator: From the Latin “to close.” Composed of nerve roots L2-L4, the obturator nerve provides sensory innervation from the medial thigh. It also innervates the muscles of the medial compartment of the thigh (gracilis, adductors, and obturator externus). It allows for hip adduction (i.e., closing the thighs).

Fibular (peroneal) branch: Composed of nerve roots L4-S2, the fibular nerve provides sensory innervation to the anterior shin and dorsum of the foot. It innervates the anterior compartment of the leg and is responsible for foot and toe dorsiflexion. Injury causes foot drop.

Fibular (peroneal) branch: Composed of nerve roots L4-S2, the fibular nerve provides sensory innervation to the anterior shin and dorsum of the foot. It innervates the anterior compartment of the leg and is responsible for foot and toe dorsiflexion. Injury causes foot drop.

Tibial branch: Composed of nerve roots L4-S3, the tibial nerve provides sensory innervation to the sole of the foot. It innervates the hamstrings, soleus, and gastrocnemius muscles and allows for knee, foot, and toe flexion.

Tibial branch: Composed of nerve roots L4-S3, the tibial nerve provides sensory innervation to the sole of the foot. It innervates the hamstrings, soleus, and gastrocnemius muscles and allows for knee, foot, and toe flexion.

Superior gluteal: Composed of nerve roots L4-S1, the superior gluteal nerve innervates the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and tensor fasciae latae muscles (thigh abduction). Injury causes inability to abduct the thigh while walking, which can cause Trendelenburg gait.

Inferior gluteal: Composed of nerve roots L5-S2, the inferior gluteal nerve innervates the gluteus maximus muscle (hip extension).

Peripheral Nerve Lesions of the Lower Extremity

See Table 12-2.

Foot drop: Compression of the common fibular (peroneal) nerve at the head of the fibula causes weakness of the anterior tibialis muscle and inability to dorsiflex the foot. Patients may present with a steppage gait, where they lift the affected thigh high enough to prevent their toes from dragging on the ground. Nerve compression is most frequently caused by simply crossing the legs in a way that causes pressure on the fibular head. Fibular head and neck fractures are also occasionally implicated. Sensory loss may be concurrent and occurs in the anterolateral shin and dorsum of the foot (superficial peroneal nerve distribution).

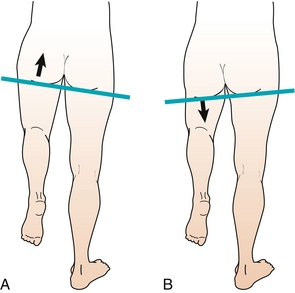

Trendelenburg gait: Injury to the superior gluteal nerve causes weakness of the gluteal muscles and inability to abduct the thigh. On exam, patients will have drooping of the affected buttock on raising the affected leg (Trendelenburg sign; Fig. 12-13). When walking, they will compensate by leaning their trunk over the affected side (Trendelenburg gait).

Figure 12-13 Injury to the superior gluteal nerve results in drooping of the affected buttock on raising the affected leg (Trendelenburg sign). A, Normal physical exam. B, Trendelenburg sign. (From Moore NA, Roy WA. Rapid Review Gross and Developmental Anatomy. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2010.)

Joints

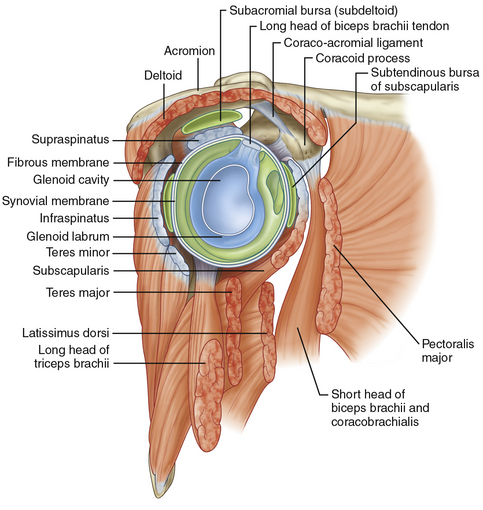

Shoulder: The shoulder is formed mostly by the humeral head as it sits in the glenoid fossa. The rotator cuff is a group of four tendons that support the glenohumeral joint.

The muscles involved can be remembered by the mnemonic: SItS—Supraspinatus (abduction), Infraspinatus (external rotation), teres minor (abduction), and Subscapularis (internal rotation; Fig. 12-14).

Figure 12-14 Muscles of the rotator cuff. (From Drake RL, Vogl AW, Mitchell AWM. Gray’s Anatomy for Students. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2009.)

Rotator cuff tear: Most frequently affects the supraspinatus and may be detected by a positive drop arm test (inability to keep arm abducted below 90 degrees).

Impingement syndrome: Occurs when the supraspinatus tendon becomes inflamed as it passes between the acromion process and the head of the humerus. Symptoms include shoulder pain and weakness, especially with overhead movements. Physical exam may reveal a positive Hawkin’s test.

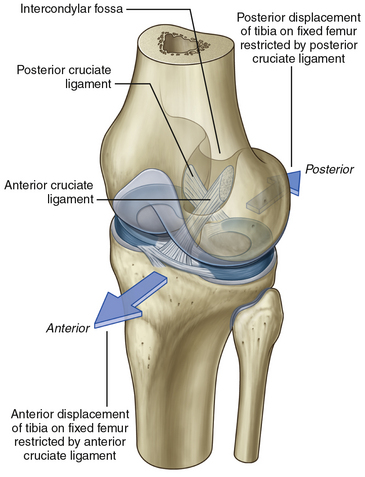

Knee: The ligamentous structures of the knee add stability to the joint. Extracapsular ligaments include the lateral and medial collateral ligaments, which resist valgus and varus forces, respectively. The patellar ligament connects the patella to the tibial tuberosity. Intracapsular ligaments are described later (Fig. 12-15).

Figure 12-15 Ligaments of the knee. (From Drake RL, Vogl AW, Mitchell AWM. Gray’s Anatomy for Students. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2009.)

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear: The ACL originates on the posterior surface of the femur and travels to the anterior surface of the tibia. It functions to prevent anterior translation of the tibia in relation to the femur. Injury often occurs secondary to forced hyperextension or noncontact injury during pivoting (e.g., while skiing). Patients will report an immediate “pop” sensation and inability to bear weight, followed by swelling of the affected knee (secondary to hemarthrosis). Physical exam will reveal joint instability, with a positive anterior drawer and Lachman test (forced anterior translation of the tibia on the femur). X-rays are nondiagnostic, but magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) will reliably reveal a tear. Treatment may be conservative or surgical.

Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) tear: The PCL originates on the anterior surface of the femur and travels to the posterior surface of the tibia. It functions to prevent posterior translation of the tibia in relation to the femur. Physical exam will reveal a positive posterior drawer test (forced posterior translation of the tibia on the femur) and posterior sag test (posterior translation of the tibia on the femur due to gravity).

Medial and lateral menisci tear: These C-shaped fibrocartilage rings provide structural support to the knee and reduce friction within the joint. Physical exam of meniscal tear may reveal decreased range of motion and joint line tenderness.

Unhappy triad: Refers to simultaneous injury of the ACL, medial collateral ligament, and lateral meniscus, which may occur with lateral impact to the knee when the foot is planted on the ground.

Ankle sprains: Ankle sprains are most common after “rolling” the ankle (forced ankle inversion). The weakest ligament, the anterior talofibular ligament, is the most frequently involved. Medial ankle sprains are quite rare (forced ankle eversion) because of the strength of the medial deltoid ligament. This is intuitive by simply noting the ease of ankle inversion compared with the difficulty of ankle eversion.

PATHOLOGY

Neuromuscular Junction Disorders

Myasthenia gravis (MG): Autoimmune condition in which antibodies attack postsynaptic nicotinic acetylcholine receptors at the neuromuscular junction (NMJ). The result is muscle weakness and easy fatigability that worsens throughout the day and with repetitive movement. Muscles of the face are particularly affected, and patients often present with ptosis or difficulty keeping their eyes open by the end of the day. Myasthenic crisis occurs when weakness significantly affects the muscles of respiration. Diagnosis of myasthenia gravis can be suggested by the ice pack test. Because NMJ transmission is more efficient at lower temperatures, an ice pack applied to the eyes improves ptosis. Injection of edrophonium, a short-acting acetylcholine esterase inhibitor, also improves ptosis by increasing acetylcholine at the NMJ. This is rarely used as a diagnostic tool anymore, however, since the surge of acetylcholine can also cause bradycardia and bronchospasm. It is still tested on Step 1 though because it addresses the underlying pathophysiology of MG. Diagnostic lab tests reveal the presence of anti–acetylcholine receptor antibodies. The thymus is often the culprit in the production of these antibodies. Computed tomography (CT) or MRI of the chest should be performed to investigate for thymoma. A therapeutic thymectomy may halt progression of the disease. Additionally, acetylcholine esterase inhibitors (e.g., pyridostigmine) provide symptomatic improvement by increasing the concentration of acetylcholine at the NMJ. Finally, immunosuppressants may decrease the autoimmune response.

Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS): Autoimmune condition in which antibodies attack presynaptic voltage-gated calcium channels at the NMJ, thereby decreasing release of acetylcholine. Unlike MG, symptoms are less likely to involve facial muscles and more likely to involve proximal muscles. Proximal muscle weakness presents as difficulty climbing stairs or rising from a chair. Unlike MG, symptoms will improve with repetitive movements (Lambert sign). LEMS is a paraneoplastic syndrome highly associated with small cell lung carcinoma. Treatment with pyridostigmine and immunosuppressants is similar to MG. Treatment should also be aimed at any underlying malignancy.

Muscular Dystrophy

Duchenne muscular dystrophy: X-linked recessive mutation of the dystrophin gene. Dystrophin connects the myocyte cytoskeleton to the surrounding extracellular matrix. Because dystrophin is the longest human gene, it is susceptible to spontaneous mutations. Without functional dystrophin, myocytes undergo damage and cell death. The result is progressive muscular weakness and atrophy, usually beginning before age 5 years. Patients are usually wheelchair-bound by age 12. The hips, pelvis, and thighs are affected first. Patients may present with pseudohypertrophy of calf muscles (calf enlargement caused by muscle tissue being replaced by fat and fibrous tissue) and Gower sign (patients rise to stand upright by walking their hands up their legs). Patients usually die in their 20s because of cardiac and diaphragmatic involvement. Elevated serum creatine kinase levels and characteristic findings on muscle biopsy are diagnostic.

Becker muscular dystrophy: Milder form of muscular dystrophy caused by dysfunctional, but not absent, dystrophin protein. Also inherited in an X-linked recessive pattern. Onset is later, and patients may survive to adulthood.

Mechanical Injuries

Sprain: Ligamentous injury as a result of forceful stretching, especially of the ankle, knee, and wrist. In severe forms, ligamentous rupture may occur producing a popping sound. Physical exam may reveal joint instability, ecchymoses, and effusion.

Strain: Muscle injury as a result of forceful stretching; colloquially known as a pulled muscle.

Shoulder dislocations: In general, there is a tradeoff between range of motion around a joint and stability of that joint. It is not surprising then that shoulder dislocation is the most commonly dislocated joint because of the phenomenal range of motion and relative instability of the glenohumeral joint. Anterior dislocation accounts for 95% of cases. It is caused by pressure to the abducted, externally rotated, extended arm, as may occur during a fall on an outstretched hand. Anterior shoulder dislocations can potentially damage the axillary nerve. Posterior dislocations only account for about 5% of shoulder dislocations and are caused by violent contractions as in seizures or electrocutions. An incredibly rare cause of shoulder dislocation (but sometimes tested) is luxation erecta, which is an inferior shoulder dislocation. This results in the patient’s arm being stuck in the raised position, as if raising their hand to ask a question.

Hip dislocation: Rare because of the relative stability of the femoral head within the acetabulum. Posterior hip dislocation accounts for 90% of all cases. They are often caused by car accidents, in which the knee is forced against the dashboard, pushing the femoral head posteriorly against the acetabulum.

Epicondylitis: Repetitive use injury causing tendon damage leading to pain and tenderness of the lateral epicondyle (tennis elbow) or medial epicondyle (golfer elbow).

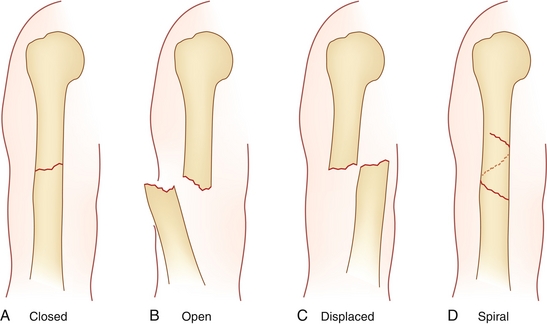

Fracture: Simply a break in the continuity of bone (Fig. 12-16). There are a number of high-yield facts that can be remembered about fractures. As a general rule, fractures should be reduced to anatomic position and immobilized.

Closed, simple: Uncomplicated fracture in which the bone does not pierce the overlying skin.

Closed, simple: Uncomplicated fracture in which the bone does not pierce the overlying skin.

Open, compound: The bone is exposed to the environment through the wound so is at risk for infection. Procedural washout and antibiotics should be used in the treatment of these fractures.

Open, compound: The bone is exposed to the environment through the wound so is at risk for infection. Procedural washout and antibiotics should be used in the treatment of these fractures.

Displaced: The bone is separated in a nonanatomic position. It must be reduced before healing.

Displaced: The bone is separated in a nonanatomic position. It must be reduced before healing.

Pathologic: Bones break after trivial trauma. Although osteoporosis often is the pathology underlying these fractures, underlying malignancies or bone cysts should also be considered.

Pathologic: Bones break after trivial trauma. Although osteoporosis often is the pathology underlying these fractures, underlying malignancies or bone cysts should also be considered.

Spiral: When torque is applied as the bone fractures, it may break in a spiral pattern. These are significant because they may indicate child abuse in the appropriate clinical scenario (e.g., fracture from twisting the child’s arm or leg). The spiral fracture of the distal tibia (toddler’s fracture) is less concerning because it may occur with rotational force during normal activity.

Spiral: When torque is applied as the bone fractures, it may break in a spiral pattern. These are significant because they may indicate child abuse in the appropriate clinical scenario (e.g., fracture from twisting the child’s arm or leg). The spiral fracture of the distal tibia (toddler’s fracture) is less concerning because it may occur with rotational force during normal activity.

Stress (hairline fracture): Fracture caused by constant or repeated stress instead of acute severe stress. Often of weight-bearing bones, including the tibia and metatarsals. X-ray may not immediately reveal the fracture, so other modalities (e.g., CT) may be necessary. Treatment or immobilization based on clinical suspicion is often reasonable.

Stress (hairline fracture): Fracture caused by constant or repeated stress instead of acute severe stress. Often of weight-bearing bones, including the tibia and metatarsals. X-ray may not immediately reveal the fracture, so other modalities (e.g., CT) may be necessary. Treatment or immobilization based on clinical suspicion is often reasonable.

Basilar skull fracture: Usually secondary to trauma and may present as periorbital ecchymoses (raccoon eyes), mastoid ecchymoses (Battle sign), cerebrospinal fluid leakage through the ears (otorrhea), or nose (rhinorrhea with salty, metallic taste).

Basilar skull fracture: Usually secondary to trauma and may present as periorbital ecchymoses (raccoon eyes), mastoid ecchymoses (Battle sign), cerebrospinal fluid leakage through the ears (otorrhea), or nose (rhinorrhea with salty, metallic taste).

Scaphoid fracture: Often secondary to a fall on an outstretched hand. Patients will have pain at the anatomic snuffbox, but x-ray is usually unremarkable during the first week. Patients still must be splinted or the proximal scaphoid may undergo avascular necrosis.

Scaphoid fracture: Often secondary to a fall on an outstretched hand. Patients will have pain at the anatomic snuffbox, but x-ray is usually unremarkable during the first week. Patients still must be splinted or the proximal scaphoid may undergo avascular necrosis.

Hip fracture: Proximal femoral fractures notable for the association with osteoporosis and extremely high mortality in older adults.

Hip fracture: Proximal femoral fractures notable for the association with osteoporosis and extremely high mortality in older adults.

Nonaccidental trauma: In children, a handful of fractures are highly suspicious for nonaccidental trauma. These include rib fractures, spiral fractures (other than toddler’s fracture), and multiple fractures of different ages. In shaken baby syndrome, subdural hematomas and retinal hemorrhages may also be found. Child services should always be notified.

Nonaccidental trauma: In children, a handful of fractures are highly suspicious for nonaccidental trauma. These include rib fractures, spiral fractures (other than toddler’s fracture), and multiple fractures of different ages. In shaken baby syndrome, subdural hematomas and retinal hemorrhages may also be found. Child services should always be notified.

Complications of Fracture

Fractures that cause reduced mobility may predispose patients to deep vein thromboses and pulmonary emboli. Anticoagulation should be considered in at-risk patients.

In long bone fractures, fat emboli can occur if bone marrow leaks into local venules and embolizes to the lung. Patients present with hypoxia, altered mental status, and petechial rash.

Tissue swelling or bleeding after a fracture may also increase local pressure because the surrounding fascial compartment may not stretch. Compartment syndrome occurs when this increased pressure compromises the vascular supply to the extremity. The forearm and leg are the areas most often affected. Patients will experience severe pain, and exam will reveal a tense, woodlike compartment. Diagnosis can be confirmed by measuring the intracompartmental pressure. Treatment is fasciotomy (surgical incision of the fascia). Mnemonic: History and physical reveals the five Ps: Pain, Pallor, Paresthesias, Pulselessness, Paralysis.

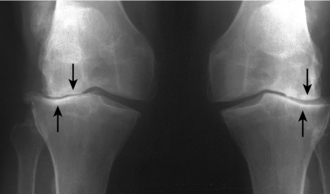

Osteoarthritis: Degenerative joint disease caused by mechanical wear and tear. Damage manifests as breakdown of cartilage, injury of subchondral bone, and changes to all articular structures. It is the most common type of arthritis. It presents as pain in weight-bearing joints that worsens with use. It may also be associated with decreased range of motion, a “cool” (noninflammatory) effusion, crepitus, and bony deformities (e.g., Heberden’s or Bouchard’s nodes). The joints most commonly affected are the distal interphalangeal, proximal interphalangeal, knees, hips, toes, and spine. Radiography reveals (1) osteophytes, (2) joint space narrowing, (3) subchondral cysts, and (4) subchondral sclerosis (Fig. 12-17). Treatment involves weight loss (to decrease stress on all joints), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), acetaminophen, physical therapy, and/or intraarticular injections of steroids or hyaluronic acid. Surgery may also be indicated.

Figure 12-17 Radiographic image of osteoarthritis with joint space narrowing (arrows), sclerotic bone, osteophytes, and subchondral cysts. (From Kelly IC, Bickle BE. Crash Course Imaging. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2007.)

Charcot joint: Neuropathy, usually secondary to diabetes, reduces pain sensation and proprioception in the affected joint. Without these protective senses, joint destruction can be rapid and profound.

Disease of Bone

Osteomyelitis: Infection of bone caused by (1) direct inoculation (e.g., penetrating trauma), (2) contiguous spread (e.g. cellulitis), or (3) hematogenous spread. Osteomyelitis is diagnosed by plain films or MRI.

Of note, it is one of the few conditions that can raise an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) higher than 100 mm/hr. Overall, Staphylococcus aureus is the most common causative organism, but some populations deserve special mention:

Patients with sickle cell anemia: Salmonella

Patients with sickle cell anemia: Salmonella

Diabetic foot infections: Pseudomonas or polymicrobial

Diabetic foot infections: Pseudomonas or polymicrobial

Osteoporosis: Decreased bone density with normal bone architecture. Defined as a T score > 2.5 standard deviations below peak bone mass measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan. Patients may be asymptomatic but are prone to fractures.

Of note, vertebral compression fractures may lead to loss of height, kyphosis, and possibly back pain, with or without radiculopathy. Hip fractures are of particular concern because of their high mortality rate. Risk factors include age, smoking, female gender, and glucocorticoid use. Weight-bearing exercise is protective. Treatment may involve adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D. Bisphosphonates inhibit osteoclast resorption of bone and are first-line pharmacotherapy.

Osteomalacia: Adult-onset vitamin D deficiency causing bony pain, “soft bones,” and fractures. Low vitamin D leads to decreased serum calcium, which causes elevated PTH. PTH, in turn, raises serum calcium at the expense of mineralized bone. Patients with fractures accompanied by malnutrition, malabsorption, or intestinal bypass should be considered for osteomalacia. Pertinent lab values can be deduced: low vitamin D → low calcium → elevated PTH → low phosphate (caused by decreased renal reabsorption).

Rickets: Vitamin D deficiency in childhood, leading to defective mineralization at the growth plate. Compromised bony stability may cause bowing of long bones (genu varum; Fig. 12-18).

Figure 12-18 Rickets, bowing of long bone secondary to vitamin D deficiency in childhood. (From Kelly IC, Bickle BE. Crash Course Imaging. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2007.)

Osteogenesis imperfecta: Autosomal dominant disorder of type I collagen leading to blue sclerae (Fig. 12-19), brittle bones, and hearing loss (ossicle damage). The severity of the disease is highly variable, ranging from being fatal in utero to a mildly increased risk of fractures. Because these patients present with multiple fractures of different ages, your goal on Step 1 may be to distinguish this condition from child abuse (look for blue sclerae as a hint).

Figure 12-19 Blue sclerae of a patient with osteogenesis imperfecta. (From Lissauer T, Clayden G. Illustrated Textbook of Paediatrics. 4th ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2011.)

Achondroplasia: Autosomal dominant form of dwarfism caused by mutation of fibroblast growth factor receptor-3. This receptor becomes constitutively active and results in paradoxic inhibition of longitudinal bone growth, making the limbs comparatively shorter than the near- normal skull and trunk. Pituitary dwarfism, by comparison, causes proportional decrease in size caused by lack of growth hormone secretion.

Paget disease of bone (osteitis deformans): Disorganized bone remodeling from increased osteoclast and osteoblast activity, which results in overgrowth of affected bone. The cause is unknown; however, viral infection and/or genetic predisposition may play a role. Most patients are asymptomatic. They may be diagnosed incidentally based on elevated alkaline phosphatase levels and radiographic abnormalities. Symptoms include pain and deformity of affected bones. Complications include fractures, nerve compression (e.g., hearing loss), and high-output heart failure (from increased vascularity of bone). Patients are also at increased risk for osteosarcoma. Treatment is with bisphosphonates. Radiography may reveal cotton wool appearance of bone (Fig. 12-20).

Figure 12-20 Paget’s disease of bone. Shown is the cotton wool appearance of bone on a skull radiograph (arrows). (From Lawlor MW. Rapid Review USMLE Step 2. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2006.)

Osteopetrosis (marble bone disease): Defective osteoclast resorption of bone secondary to carbonic anhydrase deficiency. Unopposed osteoblast activity leads to thickened, brittle bones that are prone to fracture. Invasion of bone marrow leads to pancytopenia and splenomegaly secondary to extramedullary hematopoiesis.

Osteitis fibrosa cystica: Elevated parathyroid hormone overstimulates osteoclasts to resorb bone. Lab values can be deduced—primary hyperparathyroidism → elevated PTH → elevated calcium, elevated alkaline phosphatase (from bone resorption), and low phosphate (from renal wasting). Substantial resorption of bone causes cystlike brown tumors within the bone, consisting of fibrous tissue and woven bone without matrix.

Polyostotic fibrous dysplasia: Problem of osteoblastic maturation, in which fibrous tissue forms instead of medullary bone. The result is painful swollen bones that are prone to pathologic fractures. The ribs and femur are most commonly affected. These lesions can be confused with the brown tumors of osteitis fibrosa cystica, but the pathophysiology is different.

McCune-Albright syndrome: Triad of polyostotic fibrous dysplasia, precocious puberty, and unilateral café-au-lait spots.

Rheumatology

Inflammatory Arthritis

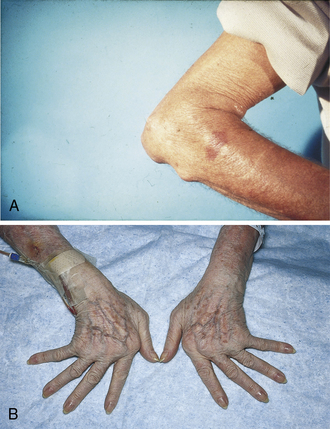

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA): Autoimmune condition causing symmetric joint destruction. It presents as joint pain and stiffness, particularly of the metacarpophalangeal, metatarsophalangeal, proximal interphalangeal, and wrist joints. Large joints and the cervical spine may also be involved. Symptoms are worse in the morning and improve with use. Decreased range of motion, effusions, and muscle atrophy may be present, along with swan neck deformity, boutonniere deformity, ulnar deviation (Fig. 12-21B), or arthritis mutilans (bag of bones deformity). There is a genetic association with HLA-DR4. Diagnosis is clinical, but rheumatoid factor and anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) antibody may be helpful. Later in the disease, radiography reveals deformity joint space narrowing and erosions. Treatment is based on DMARDs (disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs), particularly methotrexate. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors are also commonly used. Flares can be treated with NSAIDs and/or steroids. Systemic manifestations include fever, fatigue, anemia of chronic disease, and rheumatic nodules (subcutaneous nodules on extensor surfaces; Fig. 12-21A).

Figure 12-21 Physical findings of rheumatoid arthritis. A, Rheumatoid nodules. B, Ulnar deviation. (A from Talley NJ. Clinical Examination. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005; B from Swartz MH. Textbook of Physical Diagnosis, History and Examination. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2009.)

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): Relapsing and remitting autoimmune disease in which antibodies directly damage tissues (type II hypersensitivity) or form destructive immune complexes (type III hypersensitivity). Patients have a collection of symptoms, which can include arthritis, fevers, malar rash (Fig. 12-22), oral and nasal ulcerations, photosensitivity, pleuritis, pericarditis, seizures, and psychosis. Immune deposits can also cause lupus glomerulonephritis and renal failure. Like many rheumatic conditions SLE predominantly affects women (90%). African Americans are especially at risk.

Figure 12-22 Malar rash of SLE, sparing the nasolabial folds. (From Lim E, Loke YK, Thompson A. Medicine and Surgery. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2007.)

Diagnosis is based on a combination of clinical and laboratory findings that can be remembered by the mnemonic SOAP BRAIN MD: Serositis (pleuritis/pericarditis), Oral ulcers, Arthritis, Photosensitivity, Blood (anemia/leukopenia/thrombocytopenia), Renal disorders, + Antinuclear antibody (ANA), Immunologic phenomena (anti-dsDNA, antiphospholipid, anti-Sm antibodies), Neurologic (psychosis or seizures), Malar rash (“butterfly rash”), Discoid rash.

SLE causes a false-positive Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test (VDRL) result. Don’t assume syphilis.

SLE causes a false-positive Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test (VDRL) result. Don’t assume syphilis.

A negative ANA is very sensitive (rule out) and a positive dsDNA is very specific (rule in) for SLE.

A negative ANA is very sensitive (rule out) and a positive dsDNA is very specific (rule in) for SLE.

Drug-induced lupus: A mild lupus syndrome with positive ANA and antihistone antibody can occur as a result of certain drugs, including hydralazine (antihypertensive) and procainamide (antiarrhythmic).

Drug-induced lupus: A mild lupus syndrome with positive ANA and antihistone antibody can occur as a result of certain drugs, including hydralazine (antihypertensive) and procainamide (antiarrhythmic).

Sjögren’s syndrome: Autoimmune lymphocytic inflammation of joints and exocrine glands causing arthritis, xerophthalmia (dry eyes), xerostomia (dry mouth), and parotid gland enlargement. Additionally, lack of salivary protection predisposes to dental caries, and chronic inflammation predisposes to lymphoma. Diagnosis of Sjögren’s Syndrome is supported by the presence of anti-SSA (Ro), anti-SSB (LA) antibodies, and rheumatoid factor. On biopsy, lymphocytic salivary gland infiltrate is also suggestive.

Scleroderma: Rheumatic condition characterized by dysregulated matrix synthesis causing collagenous deposition in tissues and blood vessels (luminal narrowing). Tissue is damaged directly by matrix deposition and by subsequent inflammation. Skin becomes thickened and taut, causing sclerodactyly and contractures (Fig. 12-23).

Figure 12-23 Calcinosis and sclerodactyly of scleroderma. (From Talley NJ. Clinical Examination. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005.)

Diffuse systemic sclerosis: Diffuse skin and organ involvement, including skin, kidneys (scleroderma renal crisis), gastrointestinal (GI) tract (dysmotility), and the most severe—lungs (interstitial lung disease). There is an association with anti-SCL70 antibody.

Diffuse systemic sclerosis: Diffuse skin and organ involvement, including skin, kidneys (scleroderma renal crisis), gastrointestinal (GI) tract (dysmotility), and the most severe—lungs (interstitial lung disease). There is an association with anti-SCL70 antibody.

Limited systemic sclerosis (CREST): Calcinosis (subcutaneous calcium hydroxyapatite deposition), Raynaud phenomenon, Esophageal dysmotility, Sclerodactyly, and Telangiectasias. Anticentromere antibody may be present. There is also a risk for pulmonary disease.

Limited systemic sclerosis (CREST): Calcinosis (subcutaneous calcium hydroxyapatite deposition), Raynaud phenomenon, Esophageal dysmotility, Sclerodactyly, and Telangiectasias. Anticentromere antibody may be present. There is also a risk for pulmonary disease.

Seronegative Spondyloarthropathies

These conditions share common features of rheumatoid factor negativity, asymmetry, oligoarticular involvement, and association with the HLA-B27 allele. They have common extraarticular manifestations, including uveitis, rashes, and occasional GI symptoms. They are remembered by the acronym PAIR.

Psoriatic arthritis: An inflammatory peripheral arthritis may arise in addition to the skin findings of psoriasis (silver plaques and nail bed pitting). Distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints are particularly affected; fingers take on a characteristic sausage digit appearance (dactylitis). Radiography reveals a so-called pencil in cup deformity. See Chapter 3 for details on skin manifestations and management.

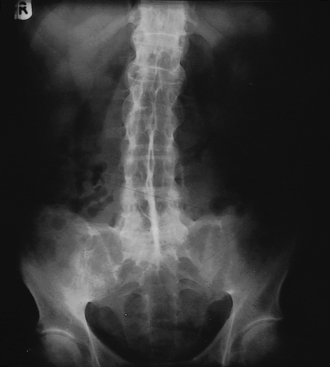

Ankylosing spondylitis: Greek for “bent spine,” this condition begins as sacroiliac joint stiffness and progresses up the spinal column. The pathophysiology involves inflammatory cells causing cartilage destruction and pannus formation, leading to joint space fusion (ankylosis). Uveitis is the most common extraarticular manifestation. Diagnosis is made based on sacroiliac tenderness, lower back pain that improves with exercise, and decreased range of motion. Radiology may reveal a “bamboo spine” from ankylosis (Fig. 12-24). Complications may result from fracture of fused spinal segments, which can lead to cord impingement.

Figure 12-24 Radiograph demonstrating so-called bamboo spine in a patient with ankylosing spondylitis. (From Kumar P, Clark M. Clinical Medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2002.)

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): Of patients with IBD, 2% to 20% may have an inflammatory arthritis in addition to GI symptoms (see Chapter 10).

Reactive arthritis: Inflammatory arthritis as a reaction to prior infection. Pathogens include Chlamydia trachomatis and GI pathogens (Salmonella, Shigella, and, Campylobacter). Clinically, patients present days to weeks after an instigating infection with the triad of urethritis, conjunctivitis (or uveitis), and arthritis remembered by the mnemonic—“can’t pee, can’t see, can’t climb a tree.” Previously referred to as Reiter’s syndrome.

Table 12-3 reviews the antibodies and laboratory findings associated with these rheumatologic conditions.

Table 12-3

Autoantibodies and Laboratory Findings Associated with Various Rheumatic Conditions

| Study | Condition |

| Antinuclear antibody (anti-smith and anti–double-stranded DNA) | Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) |

| Anti–histone antibody | Drug-induced lupus |

| Anti-SSA (Ro) | Sjögren’s Syndrome, SLE |

| Anit-SSB (La) | Sjögren’s syndrome |

| Anti–centromere antibody | CREST syndrome (limited systemic sclerosis) |

| Scl70 | Scleroderma (diffuse systemic sclerosis) |

| Anti–topoisomerase antibody | Scleroderma (diffuse systemic sclerosis) |

| Anti–Jo antibody | Polymyositis |

| Voltage-gated calcium channel antibodies | Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome |

| Anti–acetylcholine receptor antibody | Myasthenia gravis |

| Anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| Rheumatoid factor | Rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren’s syndrome |

| HLA-DR4 | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| HLA B27 | Psoriasis, ankylosing spondylitis, inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis |

Monoarticular Disease

Infectious Arthropathy

Septic arthritis (acute): Given the severity of this condition, all arthritides affecting a single joint should be considered septic arthritis until proven otherwise. It is the result of joint space invasion by an infectious organism, with subsequent inflammation. Infection typically spreads hematogenously, but direct inoculation may also occur (e.g., trauma). Septic arthritis presents as a red, swollen, hot joint with loss of motion and inability to bear weight. Fever may also be present. S. aureus and streptococcal subspecies are the most common pathogens. A synovial fluid aspiration is always necessary and will reveal more than 50,000 neutrophils. Gram stain or culture may reveal the causative organism. Treatment is with surgical joint washout and IV antibiotics. Failure to treat promptly results in permanent functional impairment and may also lead to sepsis and death.

Disseminated gonococcus: Gonorrhea may produce a migratory monoarthritis associated with tenosynovitis and dermatitis. Urethritis may also occur. It is less severe but is treated similarly to nongonococcal septic arthritis, including antibiotics and a possible need for joint washout. Do not confuse this with reactive arthritis, which presents with ocular symptoms.

Chronic infectious arthritis: Disseminated tuberculosis, Lyme disease, and fungal infections may cause chronic monoarticular joint disease. Systemic signs will often point to these infections.

Crystal Arthropathy

Gout: Uric acid crystal (monosodium urate) deposition in joints, causing swelling and recurrent bouts of inflammation. The first metatarsophalangeal joint is commonly affected (podagra; Fig. 12-25), but any joint may be involved. Gout is associated with hyperuricemia through decreased renal excretion of uric acid or increased ingestion of purines (e.g., red meat, shellfish, wine). Acute changes in uric acid level precipitate flares. Diagnosis is made with needle aspiration of crystals that demonstrate negatively birefringent, needle-shaped crystals. Negative birefringent crystals are blue when perpendicular and yellow when parallel. Treatment of acute flares involves NSAIDs and colchicine. Long-term management involves dietary modification (decreases purine intake), allopurinol (decreases uric acid production), and probenecid (increases uric acid renal excretion). Thiazide diuretics should be avoided because they decrease excretion of uric acid. Chronic gout may lead to uric acid deposition in tophi and joint destruction.

Figure 12-25 Podagra, painful swelling of the first metatarsophalangeal joint. (From Luqmani R, Robb J, Porter D. Textbook of Orthopaedics, Trauma, and Rheumatology. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2008.)

Of note, Lesch-Nyhan syndrome is caused by an X-linked recessive mutation of hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HGPRT), an enzyme of the purine salvage pathway. Without purine salvage, uric acid builds up in the blood and urine, which presents as gout, mental retardation, self-mutilation, and uric acid crystal formation in the urine (orange-colored crystals found in a baby’s diaper).

Pseudogout: Presentation identical to gout, but caused by deposition of calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystals (CPPD). Aspiration reveals positively birefringent, rhomboid-shaped crystals.

Pediatric Conditions

Transient synovitis: Joint pain and inflammation (often of the hip) causing limited range of motion. Often occurs after a viral infection. The difficulty of this benign condition is that it may mimic septic arthritis. In transient synovitis, unlike septic arthritis, patients are unlikely to have fever, leukocytosis, or elevated ESR. These patients can be treated with NSAIDs; however, if septic arthritis cannot be ruled out, a joint aspiration should be performed.

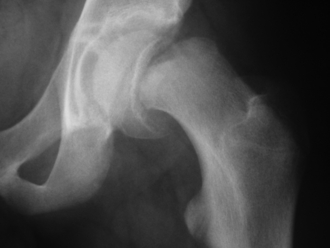

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE): Typically occurs in obese children between 11 and 15 years of age. Typically presents as hip pain and altered gait secondary to slippage at the epiphyseal plate (growth plate), in which the epiphysis remains in the acetabulum and the metaphysis becomes displaced. On AP and frog-leg lateral x-rays, this appears as a so-called ice cream scoop slipping of the cone (Fig. 12-26). Treatment involves surgical stabilization with pinning. If untreated, patients are at risk for avascular necrosis of the femoral head.

Figure 12-26 Radiograph demonstrating slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Note the appearance of “ice cream slipping of the cone.” (From South M, Isaacs D, Roberton DM. Practical Paediatrics. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2007.)

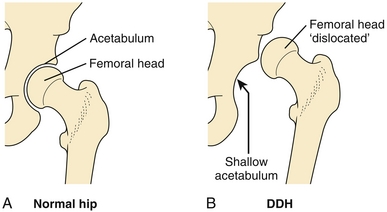

Developmental dysplasia of the hip: Congenital instability of the femoral head within the acetabulum leading to hip dislocation (Fig. 12-27). Screening should be performed on physical exam of all neonates and may reveal asymmetry of leg creases. Clicks and clunks on forced adduction or abduction of the hip indicate positive Barlow and Ortolani maneuvers. Risk factors include female gender, family history, and breech presentation. Patients are often managed with splinting. If left untreated, patients may slowly develop hip pain, gait abnormalities, or leg length discrepancies.

Figure 12-27 A, Normal hip. B, Developmental dysplasia of the hip. The femoral head is easily dislocated from the shallow acetabulum. (From Marsland D, Kapoor S. Crash Course: Rheumatology and Orthopaedics. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2008.)

Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease: Idiopathic avascular necrosis of the femoral head causing hip pain and inability to bear weight. Patients are usually between the ages of 5 and 7 years. Don’t forget that hip pain can be referred to the knee or groin in any condition. X-rays may be normal in early disease, so MRI may be indicated.

Osgood-Schlatter disease: Avulsion of the patellar tendon (Fig. 12-28) causing pain and tenderness at the tibial tuberosity. Avulsion is secondary to repetitive stress on the patellar tendon from sports or exercise. The typical patient is an athletic adolescent boy. Treatment is conservative and braces or casts are rarely required.

Other Conditions

Sarcoidosis: Condition characterized by noncaseating granulomas in various tissues. More common in African American women. Pulmonary sarcoidosis is the most common presentation, which can manifest clinically as shortness of breath and cough. Patients also frequently present with erythema nodosum. Chest x-ray reveals bilateral hilar adenopathy (Fig. 12-29), and labs may reveal elevated serum levels of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE). Symptoms may remit spontaneously, but severe cases can be treated with corticosteroids. Although almost every organ can be affected in sarcoidosis, the information in this section should suffice for your Step 1 exam.

Figure 12-29 Bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy of sarcoidosis. (From Kelly B, Bickle IC. Crash Course Imaging. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2007.)

Polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR): Autoimmune condition of adults characterized by pain of proximal muscles (hips and shoulders) that is worse in the morning. Pain must also be accompanied by ESR > 40 mm/hr and/or elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) level. It is one of the few conditions in which the ESR may be greater than 100 mm/hr (also consider osteomyelitis and temporal arteritis). Treatment is with prednisone. There is a strong association with temporal arteritis, so ocular symptoms and headaches may necessitate temporal artery biopsy.

Polymyositis: Connective tissue disease of muscle characterized by weakness in proximal muscles. Polymyositis may present as difficulty ascending stairs or rising from a chair. Labs reveal an elevated creatine kinase (CK) level and positive anti–Jo antibody. Muscle biopsy is diagnostic. Treatment is with steroids. There is an association with internal malignancy.

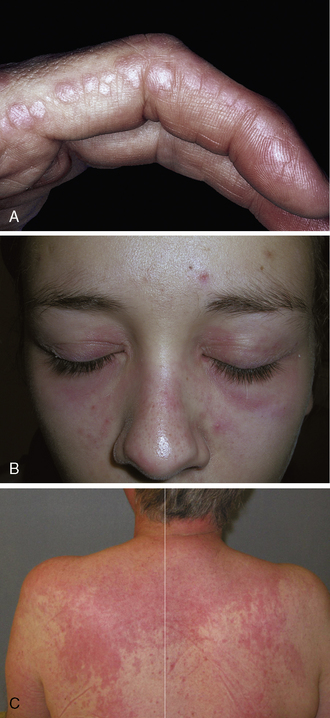

Dermatomyositis: Connective tissue disease similar to polymyositis, but with dermatologic manifestations, including Gottron papules (Fig. 12-30A), heliotrope rash (Fig. 12-30B), and shawl sign (erythematous rash in the distribution of a shawl; Fig. 12-30C). As in polymyositis, there is an elevated CK level, and muscle biopsy is diagnostic. Compared with polymyositis, there is an even stronger association with internal malignancy.

Figure 12-30 Physical exam findings in a patient with dermatomyositis. A, Gottron papules. B, Heliotrope rash. C, Shawl sign. (A from Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology. 5th ed. London: Elsevier; 2009. B from Rakel RE, Rakel DP. Textbook of Family Medicine. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2011; C from Hochberg MC, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, et al. Rheumatology. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2010.)

Mixed connective tissue disease: Overlap disease that may have features of scleroderma, lupus, RA, and polymyositis, but does not fit specifically into one diagnostic category. Associated with the anti-RNP antibody.

Fibromyalgia: Trigger point tenderness, fatigue, and joint stiffness thought to be caused by abnormal processing of painful signals. On Step 1, look for a patient with persistent pain despite lack of diagnostic findings, except for tenderness over multiple trigger points.

Neoplasms of Bone

Benign

Osteochondroma: Most common benign tumor of bone. Cartilage-forming tumor that presents between 10 and 20 years of age. Described as mushroom-shaped because of its cartilage-capped outgrowth on a bony stalk. Most commonly presents in the metaphysis of the distal femur. Malignant transition is rare, and management involves simple excision.

Osteoma: Benign tumor of bone that presents between 10 and 20 years of age. It most frequently protrudes from the skull, and symptoms are related to their interference with surrounding structures. Osteomata are also found in Gardner’s syndrome accompanied by multiple colonic polyps.

Osteoblastoma, osteoid osteoma: Benign tumor of bone that presents between 10 and 20 years of age as localized and severe bony pain caused by prostaglandin production. The pain is relieved with aspirin. Tumors most often occur in the cortex of the tibia or femur. Radiography reveals a central radiolucent nest (nidus) representing osteoid, with surrounding reactive sclerotic bone.

Giant cell tumor: Benign tumor, which appears histologically as spindle cells with multinucleated giant cells. Its most distinguishing feature is a soap bubble appearance on radiography, a large lytic (bone-destroying) lesion without calcification.

Malignant

Metastases: The most common malignancy of bone is from metastatic disease, especially of the breast, lung, thyroid, kidney and prostate.

Mnemonic: BLT with a Kosher Pickle.

Breast, lung, thyroid, and renal cell carcinomas tend to be lytic. Prostatic metastases are blastic. In addition, multiple myeloma may present as multiple, punched-out lytic bone lesions characteristic of the condition (Fig. 12-31).

Figure 12-31 Multiple punched-out lytic bone lesions of multiple myeloma. (From Lawlor MW. Rapid Review USMLE Step 2. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2006.)

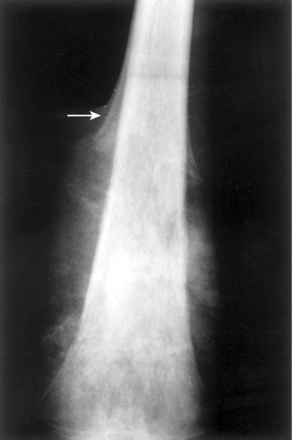

Osteosarcoma: Accounts for about 35% of primary bone malignancies. Patients often present between 10 and 20 years of age with pain or swelling, especially of the distal femur. The tumor is composed of osteocytes surrounded by osteoid. Radiography reveals a characteristic sunburst pattern (spiculated calcifications) and Codman triangle (raised periosteum in triangular shape) (Fig. 12-32). Because the bone is weak, it may also present as a pathologic fracture. The tumors are fast-growing and have a 60% 5-year survival rate. They frequently metastasize to lung. Paget’s disease is a risk factor.

Figure 12-32 Osteosarcoma of the distal femur with sunburst pattern of spiculated calcifications. Note the white arrow pointing to raised periosteum in a triangular shape (Codman triangle). Step 1 may ask that you recognize the diagnosis based solely on a similar image. (From Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster J. Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 8th ed. New York: Elsevier; 2009.)

Chondrosarcoma: Accounts for about 30% of primary bone malignancies. Slow-growing malignant tumor of cartilage, most frequently occurring in the proximal femur or pelvis. Patients are typically males older than 45 years. Radiography reveals bony destruction with calcified spots. Histology reveals gelatinous lobules of cartilage with local necrosis and calcification.

Ewing sarcoma: Accounts for about 15% of primary bone tumors. Primitive neuroectodermal malignancy that often presents between 10 and 20 years of age. It manifests with localized pain and swelling, especially of the diaphysis of the femur. It is one of the few bone tumors that is more common in females. It is distinguished radiographically by its periosteal onion skinning appearance. Histology reveals anaplastic small blue cells. A combination of surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy is often indicated.

Neoplasms of Soft Tissue

Lipoma: This benign proliferation of mature adipocytes is the most common soft tissue neoplasm. It presents as a soft subcutaneous nodule. Malignant transformation is very rare, so excision is solely for cosmetic purposes.

Liposarcoma: Rare malignant tumor of fat cells.

Rhabdomyoma: Benign tumor of striated muscle. Cardiac rhabdomyomas are associated with tuberous sclerosis.

Rhabdomyosarcoma: Rare malignant tumor of striated muscle found in the pediatric population.

PHARMACOLOGY

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs

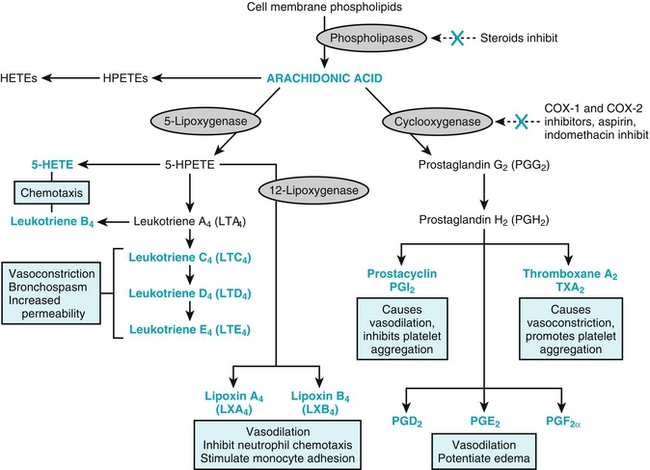

NSAIDs interfere with the arachidonic acid inflammatory pathway (Fig. 12-33) by nonselectively inhibiting cyclooxygenase-1 and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-1, COX-2). COX is an enzyme that converts arachidonic acid into prostaglandin G2 (PGI2), which is eventually converted into the prostanoids (prostaglandins, prostacyclin, and thromboxane [TX]). By inhibiting this pathway, the inflammatory, vasoactive (PGI2, TXA2), pyrogenic (PGE2), and painful (PGE2) effects are also inhibited. NSAIDs include ibuprofen, naproxen, ketorolac, indomethacin, and diclofenac. Side effects include gastritis, gastric ulcers, and GI bleeds secondary to inhibition of mucosa-protecting prostaglandins. Renal failure may also occur secondary to inhibition of prostaglandins that physiologically vasodilate the glomerular afferent arterial. NSAIDs are contraindicated in pregnancy because they may prematurely close the ductus arteriosus.

Figure 12-33 Inflammatory cascade of arachidonic acid. 5-HETE, 5-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid; HETE, hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid; HPETE, arachidonic acid 5-hydroperoxide (5-hydroperoxy- eicosatetraenoic acid. (From Kumar V, Cotran RS, Robbins SI. Basic Pathology. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2002.)

Aspirin (ASA): Unique among NSAIDs in that it covalently and irreversibly binds COX. It also preferentially inhibits COX-1 over COX-2. Because most cells in the body can simply produce more COX enzymes, the overall effects are similar to those of other NSAIDs (antipyretic, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic). Platelets, however, contain no nuclei and are unable to produce more COX. Inhibition therefore limits their ability to form TXA2 to become activated. This antiplatelet effect lasts for the lifetime of a platelet (≈ 5 to 9 days). ASA is therefore used prophylactically in patients at high risk for thrombotic events and used acutely for the management of myocardial infarction. Toxicity is similar to other NSAIDs, but bleeding is more common. ASA is also contraindicated in children with viral illnesses out of fear of Reye’s syndrome (liver failure and encephalopathy).

COX-2 inhibitors: Although COX-1 is a ubiquitous constitutively expressed enzyme, COX-2 is a facultatively expressed enzyme found in inflammatory cells (COX-1 is maintenance and COX-2 is reactive). COX-2 inhibition theoretically has the anti-inflammatory benefits, with less risk of GI side effects from prostaglandin inhibition. COX-2 is also found in vascular endothelium and produces the antithrombotic PGI2. Selective inhibition puts patients in a prothrombotic state because of unopposed action of the prothrombotic TXA2.

Acetaminophen: Analgesic and antipyretic that functions by inhibiting cyclooxygenase in the central nervous system. Its anti-inflammatory activity is limited, however, because it is not active peripherally. It is preferentially used in the pediatric population to prevent Reye’s syndrome. Acetaminophen overdose is the most common cause of acute liver failure because of its toxic metabolite. The antidote is N-acetylcysteine (see Chapter 7).

Glucocorticoids

Anti-inflammatory steroid hormone that functions by forming a complex with glucocorticoid receptors and activating nuclear transcription of anti-inflammatory mediators. Ultimately, they interfere with phospholipase A2’s production of inflammatory cytokines. Glucocorticoids include hydrocortisone, prednisone, prednisolone, and dexamethasone. There are abundant side effects to steroids, including hyperglycemia, weight gain (central obesity, buffalo hump, purple striae), osteoporosis, adrenal insufficiency, cataracts, and immunosuppression.

Osteoporosis Medications:

Calcium and vitamin D: Adequate consumption of these compounds may result in positive calcium balance and may slow or reverse bone loss. Supplementation is indicated for those with osteoporosis and inadequate dietary intake. The active form, vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol), is preferred to its precursor, vitamin D2. Calcium supplementation may be falling out of favor with some practitioners.

Bisphosphonates: First-line therapy in the treatment of osteoporosis. This class of medications becomes concentrated in bone and ingested by osteoclasts. Bisphosphonates then prevent bone remodeling by inducing osteoclast apoptosis or inhibiting resorption of hydroxyapatite. Medications have the suffix “-dronate” (e.g., alendronate, ibandronate). Bisphosphonates can also be used to prevent the pathologic remodeling of Paget’s disease. They are known to cause pill esophagitis, so patients should ingest with water and remain upright afterward.

Skeletal Muscle Relaxants

Centrally acting class of medication that reduces muscle tone. These are used in combination with NSAIDs to decrease acute muscle spasm. Examples of this class of medication include baclofen and cyclobenzaprine. Baclofen functions as a gamma-aminobutyric acid B (GABAB receptor agonist in the central nervous system and acts analogously to benzodiazepines while producing less sedation. The mechanism of action of cyclobenzaprine is less clear. Side effects include sedation and dizziness.

Gout Medications

Colchicine: Used in acute flares of gout. It acts by binding tubulin, which prevents microtubule formation and therefore neutrophil motility. Its action is thus anti-inflammatory. Because microtubules are essential for mitotic spindles, this drug is also considered a mitotic poison. This can lead to side effects such as bone marrow suppression and hair loss. GI upset, however, is more common.

Allopurinol: Used to prevent flares of gout by reducing serum uric acid concentration; not useful in acute flares. Allopurinol is a xanthine oxidase inhibitor, which prevents the conversion of hypoxanthine to xanthine and eventually uric acid. Allopurinol is also used prophylactically in patients with lymphoma and leukemia who are undergoing chemotherapy to prevent tumor lysis syndrome. Febuxostat is a newer xanthine oxidase inhibitor that can be used for patients intolerant of allopurinol.

Probenecid: Used to prevent flares of chronic gout by reducing serum uric acid concentration, but not useful in acute flares. It functions by inhibiting the nephron’s organic anion transporter, thereby inhibiting the renal reabsorption of uric acid.

Methotrexate: Used in the treatment of malignancies, methotrexate acts as an inhibitor of dihydrofolate reductase. It is also used, however, as a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug. (See Chapter 11 for details).

TNF inhibitors: These biologic agents are used in the treatment of autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriasis, and Crohn’s disease. They act by blocking TNF-α, an inflammatory cytokine secreted from monocytes. Side effects are related to impaired immunity; they include opportunistic infections and malignancies.

Etanercept: Functions as a decoy TNF receptor, thereby decreasing the level of circulating functional TNF-α.

Infliximab, adalimumab: Monoclonal antibodies that directly target TNF-α, thereby decreasing its circulating levels.

The mechanism of action of these biologic agents is hidden in their name. Etanercept is a decoy receptor. Infliximab and adalimumab are monoclonal antibodies.

The mechanism of action of these biologic agents is hidden in their name. Etanercept is a decoy receptor. Infliximab and adalimumab are monoclonal antibodies.

Rituximab: Anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (anti–B cell) used in the treatment of autoimmune conditions, often after an inadequate response to TNF-α inhibitors.

Botulinum toxin (Botox): Interferes with presynaptic release of acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction. Without acetylcholine to stimulate the endplate, the muscle is paralyzed. Botox is used not only for cosmetic purposes, but also to relieve muscle spasms and dystonias.

Botulinum toxin is produced by the gram-positive rod Clostridium botulinum. Infant botulism occurs when infants ingest the microbe (typically in honey), leading to colonization of the immature GI tract. The subsequent toxin formation leads to floppy baby syndrome. The adult GI flora is resistant to C. botulinum colonization, but the microbe may colonize wounds or form preformed toxins in home-canned foods (in which anaerobic conditions permit bacterial growth). Foodborne botulism begins with GI upset and proceeds to flaccid paralysis, especially of the cranial nerves.

Botulinum toxin is produced by the gram-positive rod Clostridium botulinum. Infant botulism occurs when infants ingest the microbe (typically in honey), leading to colonization of the immature GI tract. The subsequent toxin formation leads to floppy baby syndrome. The adult GI flora is resistant to C. botulinum colonization, but the microbe may colonize wounds or form preformed toxins in home-canned foods (in which anaerobic conditions permit bacterial growth). Foodborne botulism begins with GI upset and proceeds to flaccid paralysis, especially of the cranial nerves.