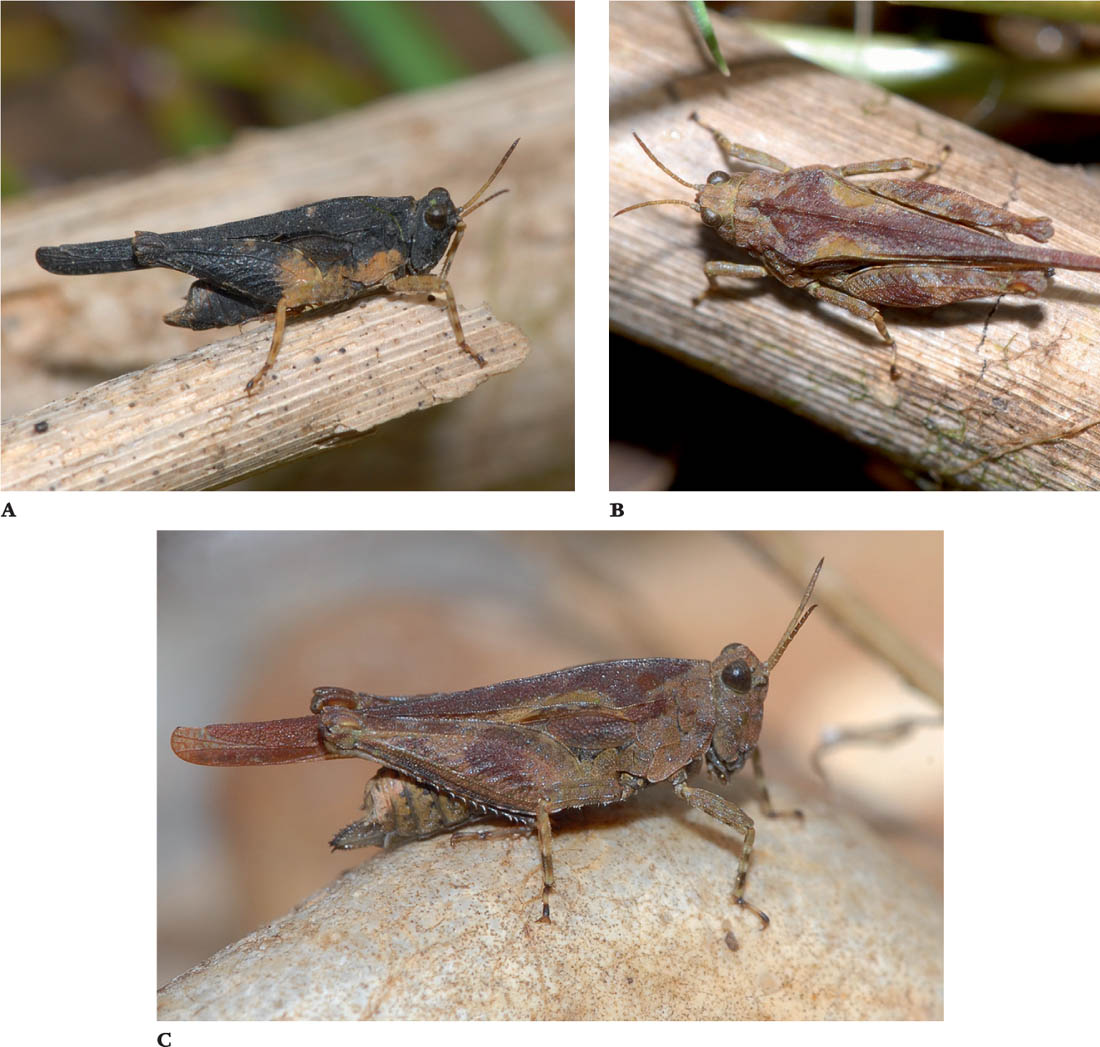

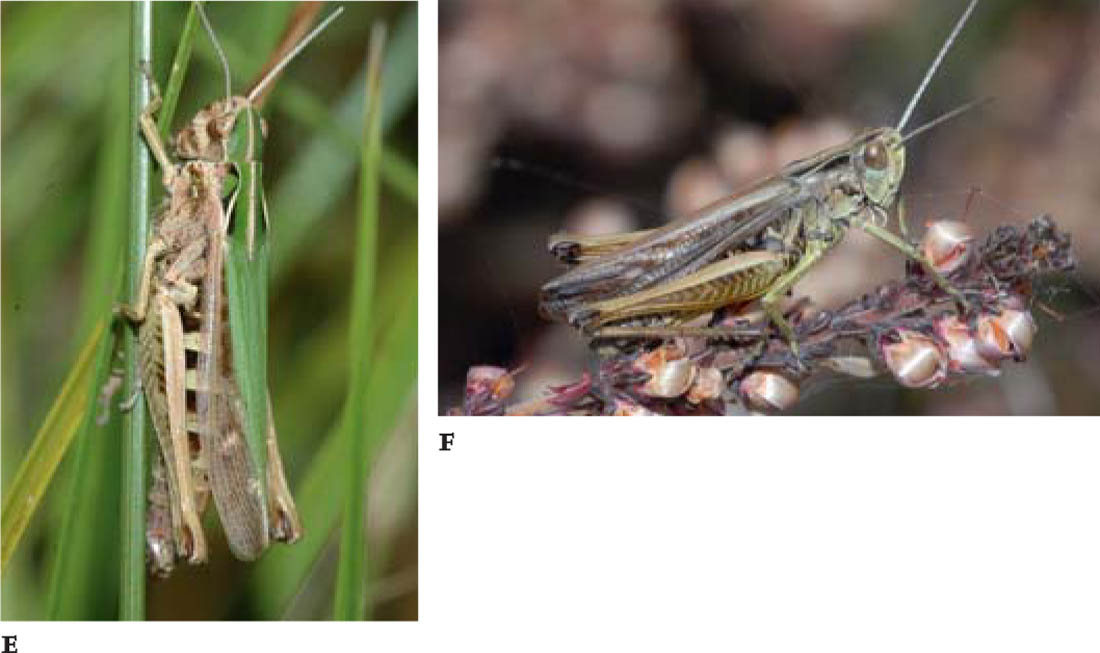

Slender groundhopper (© Tim Bernhard)

The British species, part 2: Caelifera

Groundhoppers and grasshoppers

GROUNDHOPPERS (TETRIGIDAE)

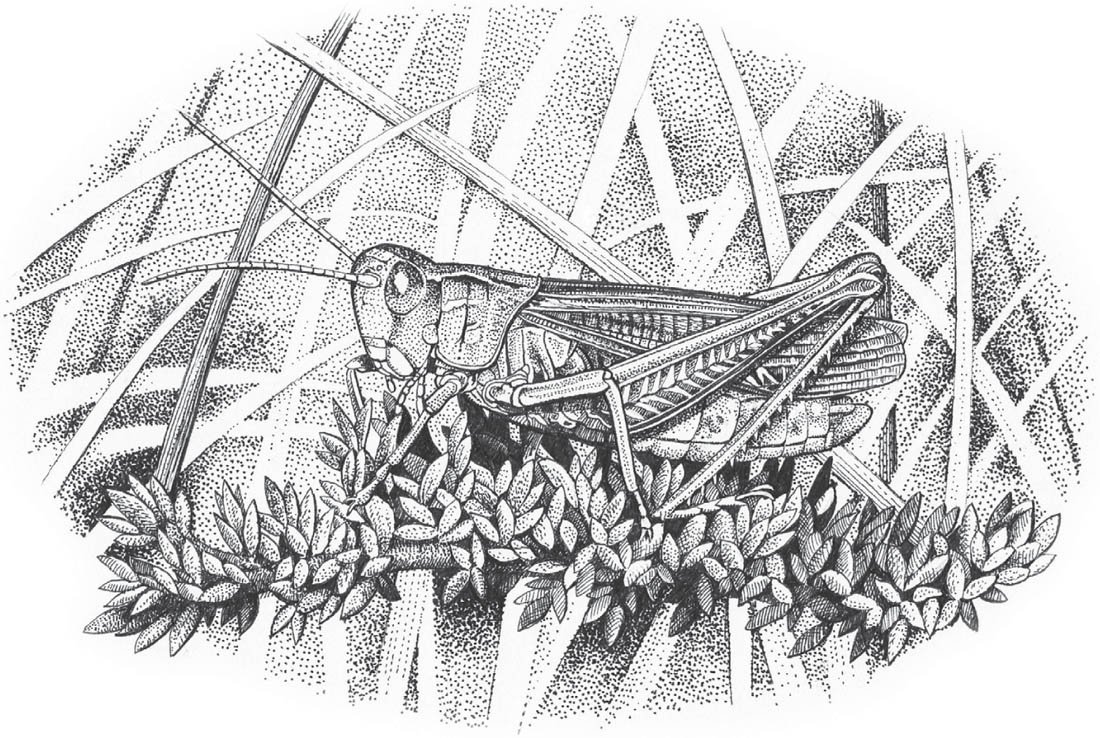

These are sometimes referred to as ‘pygmy grasshoppers’ or ‘grouse locusts’. They are believed to have changed relatively little from the evolutionary ancestors of today’s Orthoptera, and their preference for relatively simple plants such as soil algae and mosses as food sources can be understood as a legacy of their evolutionary ancestry (Blackith, 1987; Paranjape et al., 1987).

There are only three British species of this fascinating group. They superficially resemble tiny grasshoppers, but on closer inspection one can see significant structural differences. The most obvious is that the pronotum section of the thorax projects back over the abdomen, tapering towards or beyond its tip. The tarsi of the fore and mid legs have only two segments (three in grasshoppers). The male genitalia and the female ovipositor are structured very differently from those of grasshoppers.

Slender groundhopper (© Tim Bernhard)

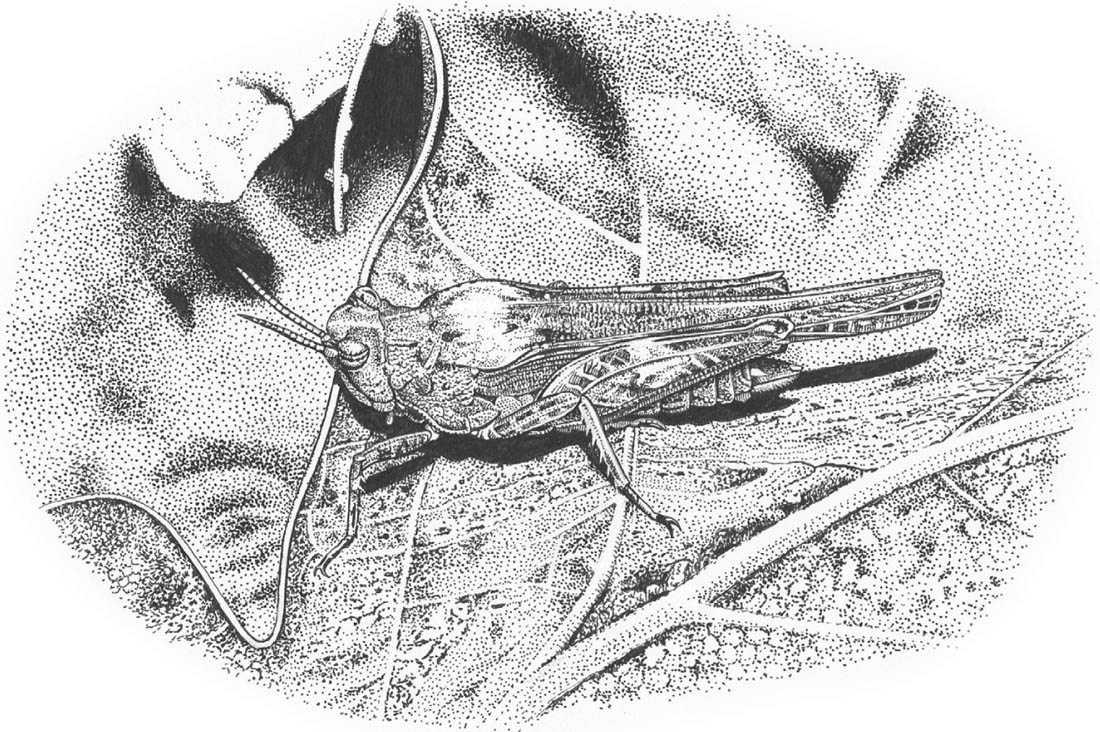

CEPERO’S GROUNDHOPPER

Tetrix ceperoi (Bolivar, 1887)

MEASUREMENTS: Male: 9.5–10.5 mm in length; female: 11–13 mm in length.

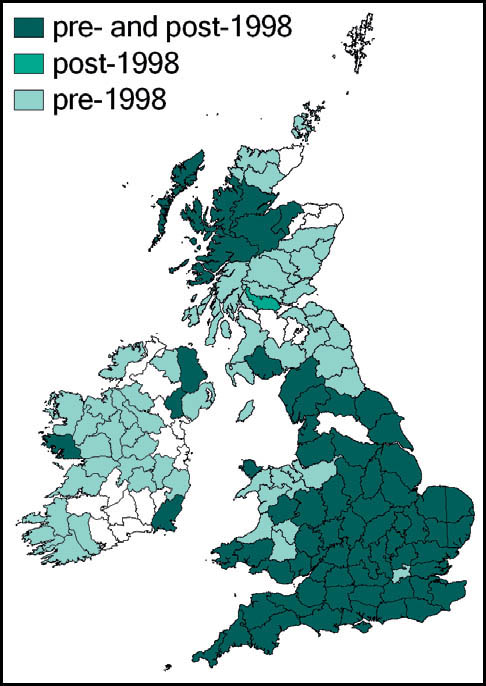

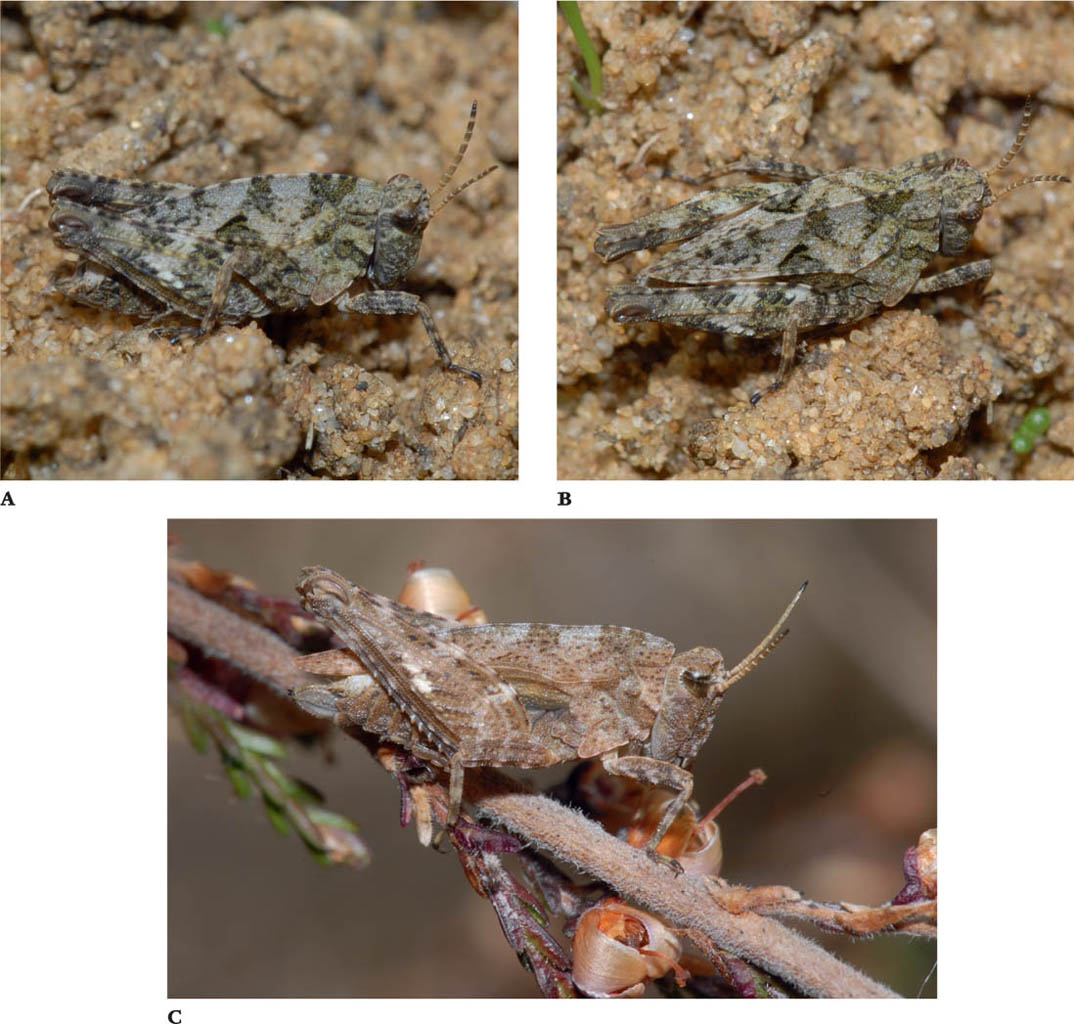

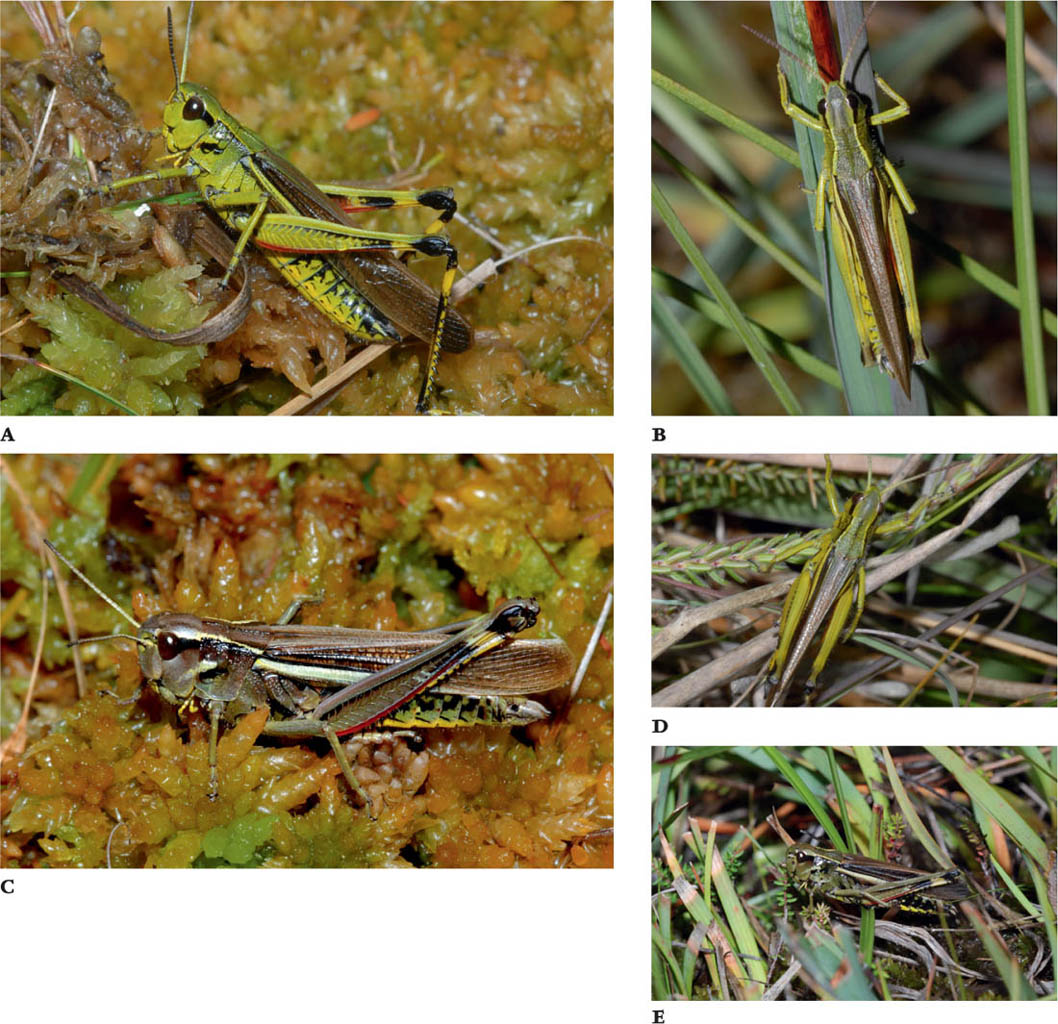

FIGS A–C. Male; dorsal view; female

Description

Like the other groundhoppers, T. ceperoi is small and inconspicuous. The pronotum has a fine median ridge running along it and tapers back, usually reaching 2.5 mm to 4 mm beyond the tip of the abdomen. The fan-shaped hind wings are kept folded under the pronotum, and usually terminate just beyond the tip of the pronotum. The fore wings are vestigial and take the form of small pads at the side of the insect’s body, just below the pronotum. The mid femora have wavy edges dorsally and ventrally, and the anterior edge of the vertex (front of the head) is approximately continuous with the front of the eyes.

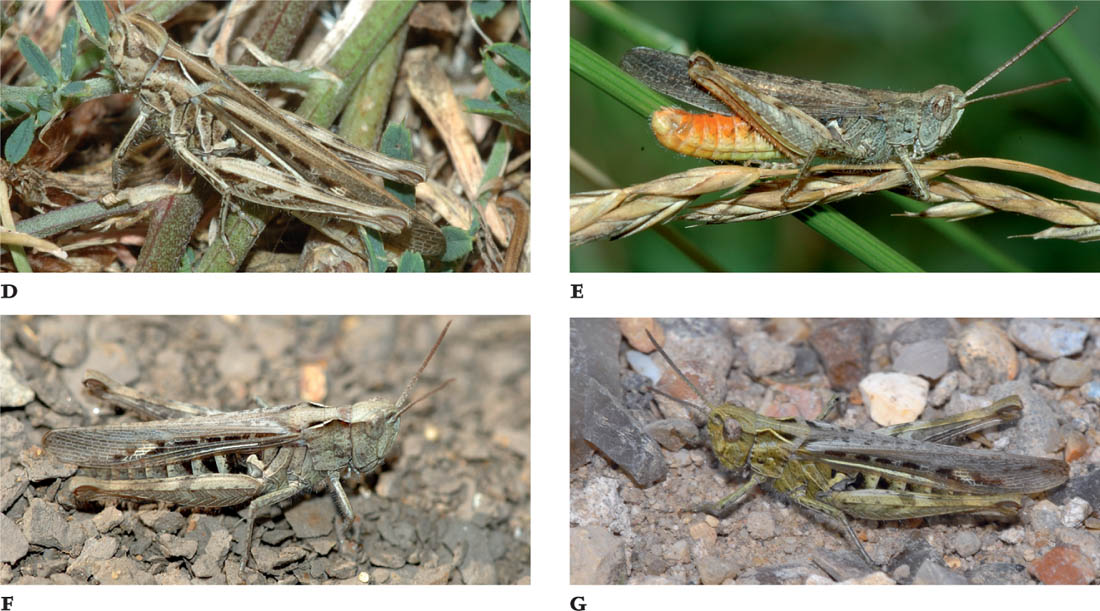

Variation

Although they are generally quite cryptically coloured, there is considerable individual variation in both the ground colour and the patterning on the dorsal surface of the pronotum. Combining ground colour and pattern variation, Paul (1988) distinguished 10 varieties, while Hochkirch et al. (2007) distinguished 20 different colour forms, which they were able to reduce to a simpler 6-fold classification: light brown, dark brown, black, mottled green, red-brown and grey. Elsewhere, Hochkirch et al. (2008a) distinguished nine different pronotal patterns.

The colour forms are classified according to a mix of basic colour and pattern into nine categories, although some defied classification in such a simplified way:

These variant colour patterns coexist in many populations, but differ in their relative frequency. Previous discussions in the literature have usually proposed explanations of the persistence of this diversity in terms of assortative mating, differential selective pressures and various genetic mechanisms on the assumption that colour patterns are strictly under genetic control (Nabours, 1929; Paul, 1988; Caesar et al., 2007). A recent study by Hochkirch et al. (2008a) showed that some aspects of adult coloration are influenced by substrate colour during individual development, but their results are contested by Karlsson et al. (2009) (see Chapter 3 for more details).

FIGS D–K. Brown with pale median dorsal stripe; green with pale dorsal stripe; grey-brown; mottled green with pale shoulders; mottled green; red-brown mottled; red-brown mottled with green; rust brown.

Similar species

T. ceperoi could be confused with either of our other two groundhoppers.

T. undulata is larger bodied (more ‘stocky’ in appearance), and has a relatively much shorter pronotum, which reaches back approximately to the tip of the abdomen (significantly further in T. ceperoi). In addition, T. undulata has a more prominent raised keel down the middle of the dorsal surface of the pronotum.

The slender groundhopper, T. subulata, is very similar to T. ceperoi and careful examination is needed to separate them.

There are five main features.

In T. ceperoi the width of the vertex is approximately 1.3 to 1.5 times the width of the eye. In T. subulata it is relatively wider, 1.5 to 1.8 or more times the width of the eye. These differences are, of course, difficult to determine with living insects in the field – but with experience the general impression of T. ceperoi is that its eyes are more prominent than those of T. subulata, when viewed from above.

In T. ceperoi the vertex does not project significantly in front of the eyes (giving the impression of a smoothly curved front edge when viewed from above). In T. subulata the vertex projects a small distance in front of the eyes. In profile, the front of the face is more vertical in T. subulata but curves back towards the top in T. ceperoi. One way of determining this is by observing (from the side) the angle formed by the meeting of the front of the face and the vertex. This is usually slightly obtuse in T. ceperoi, and acute in T. subulata.

In all, it is probably advisable to check several characters – and, even better, several specimens – for confident identification. (See the Key, Figs K12–16.)

Life cycle

The main period for mating and egg-laying in Britain is May and June. Eggs are laid in clusters held together by a sticky secretion, in damp ground or among low vegetation. They hatch in 3 to 4 weeks and the resulting nymphs pass through five (male) or six (female) instars, usually reaching adulthood by autumn. The winter is spent as either a late instar nymph or an immature adult. They may be active on warm days from early spring onwards, and reach full maturity by May.

Habitat

Despite its very restricted distribution in Britain, T. ceperoi occurs in a wide variety of habitats. These include the landward side of dune systems, on muddy or stony edges of ponds or lakes, on seepages from sea cliffs, on bare peat at the edge of streams and ponds, in wet sand pits and on muddy edges of drainage ditches. What all these habitats have in common is patches of damp or wet bare ground, interspersed with vegetation cover. The presence of soil algae, mosses or other small, delicate plants is also necessary. Most known sites in Britain are close to the coast.

Behaviour

Both sexes are inactive in dull or cool weather. In warm, sunny spells they graze on young shoots of mosses, on algae, or on decaying plant material. As they do so, their palps are continually in action, probing and ‘testing’ the substrate on which they feed. Females are relatively static, usually either feeding or occasionally moving around over mud, pebbles or larger plants. The males are more active, presumably in search of potential mates, and spend less of their time feeding. Hochkirch et al. (2007) showed that males spent more time than females did on bare ground and mosses, with greater intensity of incident sunlight. Females spent more time among leaf litter and higher plants than males did. There was a related difference in the frequency of two colour forms: black males were much more common than black females, and mottled-green females much more common than males with that background colour. Black males would be better camouflaged on a muddy background, and females on their less exposed, more vegetated preferred microhabitat. Tentative evidence that males might also be more exposed to predation was the greater incidence of missing legs in the males. In the absence of stridulation, males find mates by visual searching, and it is supposed that the clear view they get by occupying bare ground enhances their chances of success, the resulting behaviour representing a ‘trade-off between natural and sexual selection.

Males of T. ceperoi have a distinctive ‘courtship’ display, referred to by Hochkirch et al. (2006) as ‘pronotal bobbing’. This looks like a fast, deep ‘bow’ in the direction of the female (see DVD). The male simultaneously raises his hind legs and dips down his head, so raising the rest of his body at a steep angle, then returns to his usual stance and moves rapidly toward the female. In the analysis carried out by Hochkirch et al. the pronotal bobbing took on average only 0.8 of a second. The male next mounts the female and, if successful, holds on to her pronotum while curving his abdomen down between the rear portion of her pronotum and the nearside femur. Contact is then made by moving the open valves of his genitalia up to engage with the underside of the tip of the female’s abdomen. Mating usually lasts only a few seconds and the male then moves on. However, two males often compete to mate with a single female, both attempting to mount her at once. Females are polyandrous and are often prepared to mate with rival males in quick succession. However, they also reject some males by not opening the space between the hind femur and pronotum, and sometimes by vibrating vigorously until a mounted but unwanted male is shaken off (see DVD).

Where T. ceperoi occurs together with T. subulata mating attempts and actual mating take place between the two species. Gröning et al. (2007) studied ‘reproductive interference’ between the two species both in the laboratory and in the field. In both situations males of both species appeared not to discriminate between the females of the two species. However, possibly because of the distinctive visual courtship signal of T. ceperoi (‘pronotal bobbing’), females of that species rejected males of T. subulata more often than they rejected males of their own species (see Chapter 6).

Presumably their cryptic coloration, and tendency to rest on colour-matching substrates, is their main defence against predators. However, they can jump out of the way when disturbed (especially in warm weather), and they can augment their leaps with flight. They can also swim by powerful strokes of their hind legs if their escape attempts land them in open water, although there is no evidence of their entering the water independently of provocation.

Enemies

See under slender groundhopper (T. subulata).

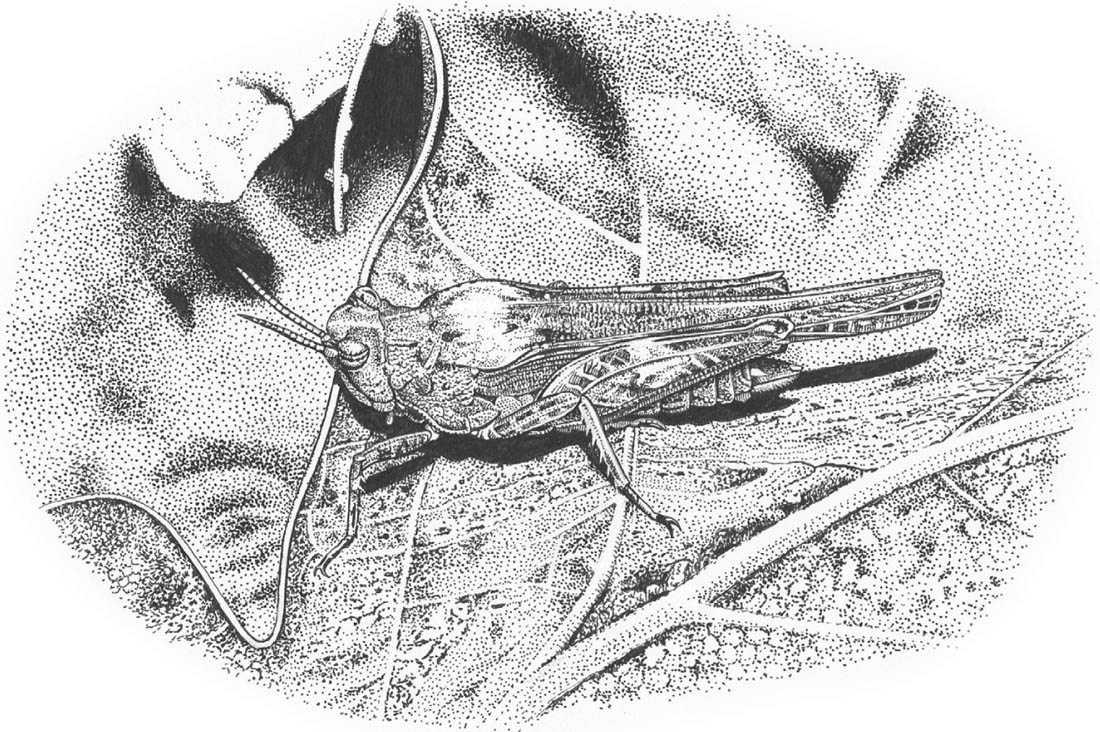

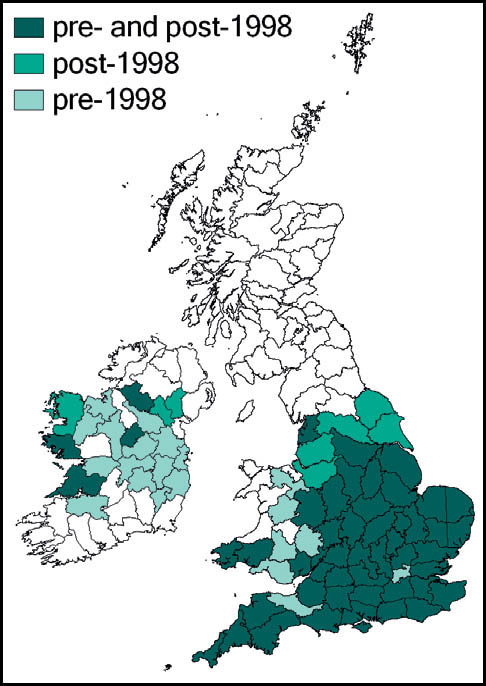

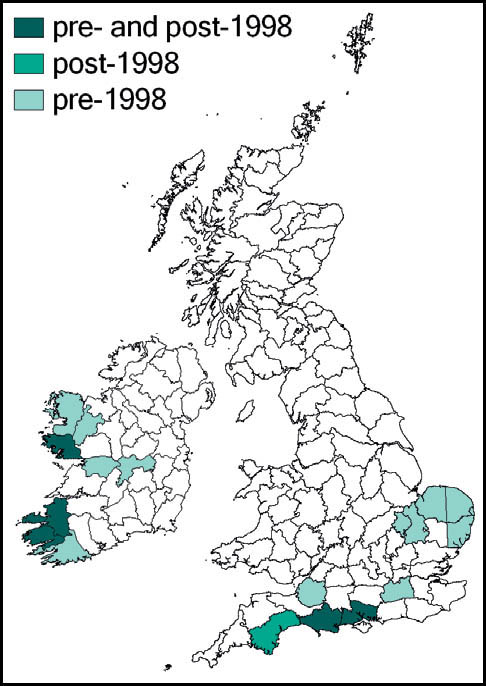

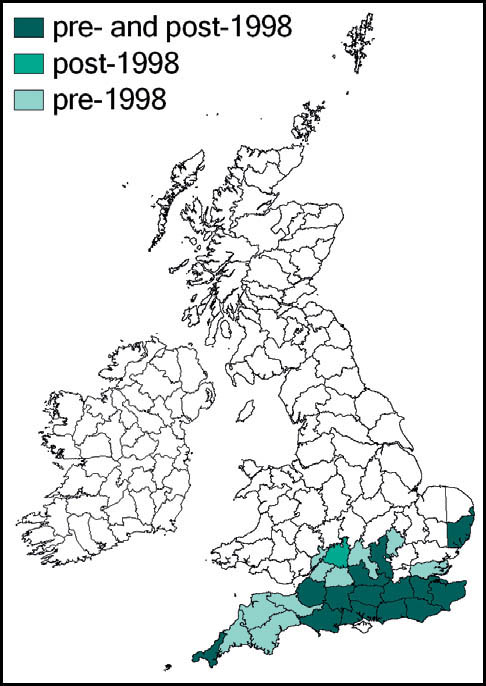

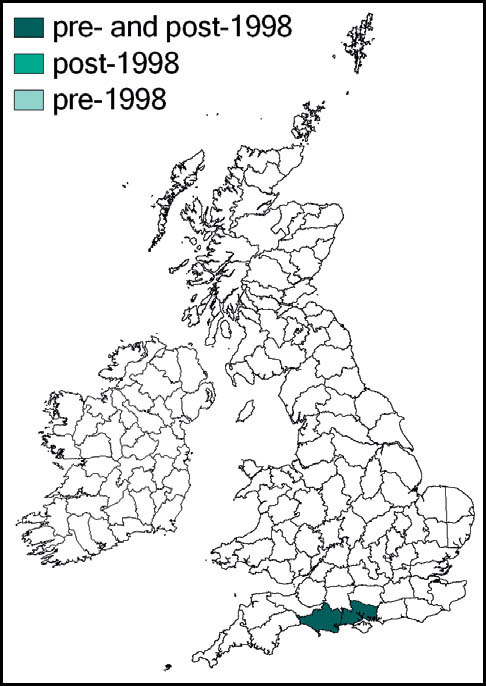

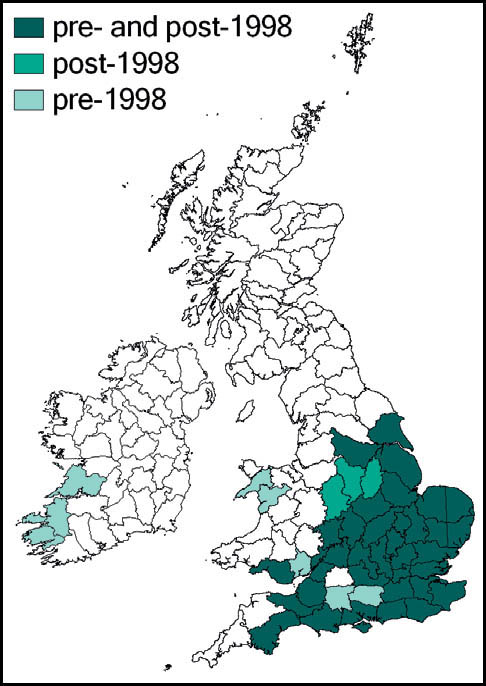

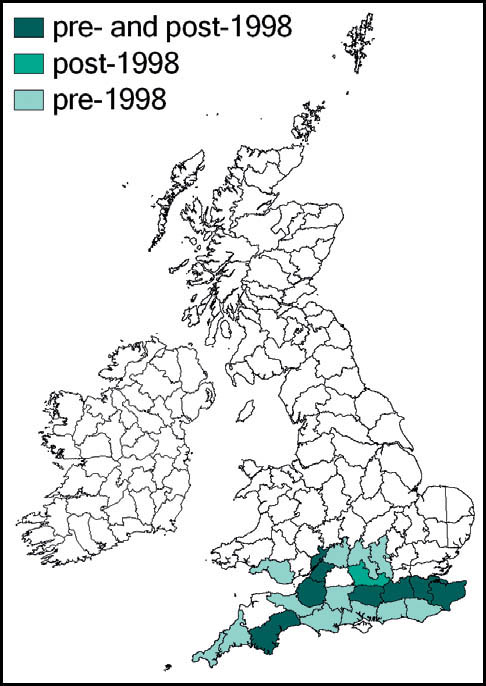

Distribution

This species is quite widespread in western and southern Europe and North Africa. In Britain it is at the northern edge of its range. Here it is regarded as a localised and scarce species, although it can be abundant in suitable sites. Its known localities are mainly coastal and in the southern counties of England and Wales. It is present in coastal districts of Kent, Sussex, Hampshire and the Isle of Wight, Dorset, Devon and Cornwall in England and Carmarthenshire and Glamorgan in south Wales. There are also inland records from Surrey and Hampshire (New Forest), and isolated records from Northamptonshire and Cambridgeshire. It is not known from Ireland.

Status and conservation

Cepero’s groundhopper was first distinguished from the slender groundhopper, Tetrix subulata, among British populations, and so recognised as a British species, by B. P. Uvarov (1940). The scarcity of T. ceperoi in Britain is probably the result of a combination of its rather specialised habitat preferences and its geographical range. It does not appear to be threatened, and, indeed, could well be under-recorded given its close similarity to T. subulata. The discovery of the species near Peterborough, many kilometres outside its previously known range, is of interest. It could be that this population is the result of an incidental introduction, but if it is not, then the possibility arises that the species may have been overlooked elsewhere outside its previously known range.

References: Brown, 1950; Caesar et al., 2007; Evans & Edmondson, 2007; Gröning et al., 2007; Hochkirch et al., 2006, 2007, 2008a; Karlsson et al., 2009; Nebours, 1929; Paul, 1988; Uvarov, 1940.

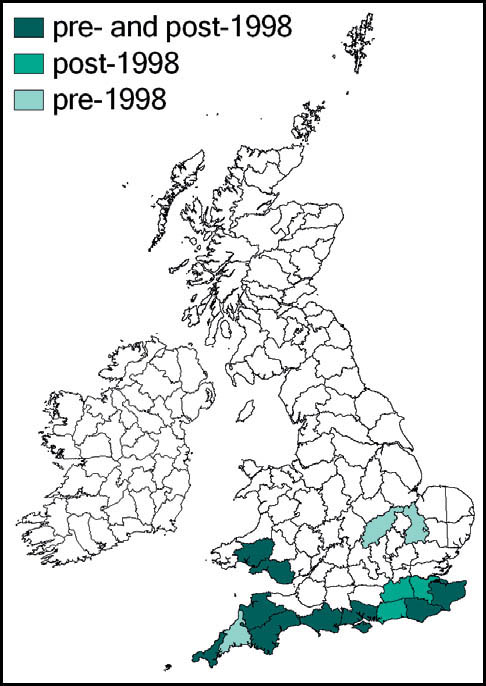

SLENDER GROUNDHOPPER

Tetrix subulata (Linnaeus, 1758)

MEASUREMENTS: Male: 9–12.5 mm in length; Female: 11–15 mm in length.

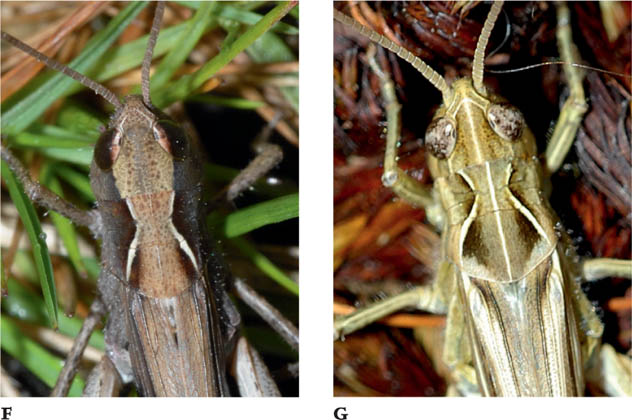

FIGS A–C. Male; dorsal view; female

FIG D. F. bifasciata

Description

This species, as its English name implies, is long and narrow in overall shape. The pronotum tapers back over the body and terminates several millimetres (3–4.5) beyond the tip of the abdomen. The fan-shaped wings, when not in use, are folded below and along the underside of the pronotum, and usually terminate just beyond its tip. The vertex is relatively broad and projects a small distance in front of the eyes. The edges of the mid femur, when viewed from the side, are straight or gently curved, not wavy, as in Cepero’s groundhopper.

Variation

There is a form of the slender groundhopper (f. bifasciata) in which the pronotum and wings are shorter than they are in the typical form, terminating only just beyond the tip of the genitalia at the rear end of the abdomen. This form varies in frequency among populations (apparently one northern locality has mostly this form (see Widgery, 1998)), and there are intermediate forms.

As in other groundhoppers, there are many different colour patterns, and usually several in any population. Some common variants are illustrated.

FIGS E–M. Dark brown with ochre patches; pale median stripe; pale shoulders; mottled form; white spot; rust-brown with dark sides; fawn with dark brown sides; dark with white flashes; dark grey unmarked.

Another colour form (not illustrated) was unmarked white, and found on exposed chalk in a disused chalk quarry (T. Tamblin, pers. obs.).

Similar species

The typical form is very similar to Cepero’s groundhopper, and close examination with a hand lens is necessary for confirmation. (For details, see under that species.)

Form bifasciata could be confused with the common groundhopper (T. undulata), but the latter is a more ‘stocky’ insect, with a strongly raised median keel on the pronotum.

Life cycle

In early spring, slender groundhoppers become fully active a little later than their close relative, the common groundhopper. Initially, much of their time is spent basking or feeding. Courtship and mating take place from early April to June in sunny weather. The eggs are approximately 3 mm in length and are loosely sausage-shaped with a horn-like projection at one end. They are laid in small holes, usually in damp soil, in clutches of 10 to 20, stuck together with an adhesive secretion. They hatch in 3 to 4 weeks. As in other Orthoptera, the initial phase is a worm-like larva, which quickly sheds its outer coating to reveal the first instar nymph. Development takes place through the spring and summer months, males passing through five, females six, nymphal stages. The previous generation of adults dies out during the summer, so that later in the year only various nymphal stages are present. The winter is spent as a final instar nymph, or as an immature adult. Full sexual maturity is reached early in the following spring.

Habitat

The slender groundhopper is usually found in damp or marshy habitats such as river edges, pond margins, wet meadows, ditches and damp hollows in heathland. However, it can also be found well away from open water, in damp woodland rides, or cart tracks. Areas of bare ground, open to sunlight, but also damp, with simple plants such as soil algae, mosses and fungi are essential. The preference for damp conditions may be associated with the relatively specialised diet, but also may reflect water demands for the eggs (Hochkirch et al., 2000). It may be that patches of bare ground are specifically required for courtship and mating, as, in many of the habitats, patches of open ground become shaded out by vigorous growth of grasses, sedges and rushes by late spring or early summer. At this time, especially, the groundhoppers climb up to sun themselves on exposed vegetation or other perches (see under ‘Behaviour’).

FIG N. Nymph.

Behaviour

Although apparently dormant during the coldest months, the groundhoppers emerge to bask in sheltered spots during sunny weather from early March (in southern England). They are present in greater numbers by the beginning of April, and by the middle of April, courtship and mating are under way.

The groundhoppers are active mainly in warm and sunny weather and later in the season, when exposed patches of bare ground are often shaded out by denser vegetation, they climb onto the higher leaves and stems of grasses or sedges to bask. They can also be seen on the reflective surfaces of containers and other litter. In one former willow plantation by a small river they could be found resting or feeding on the raised platforms provided by the mossy and part-rotted stumps of the trees (pers. obs.).

They graze on soil algae and fresh, tender shoots of mosses, but will also consume detritus, and females sometimes eat young, tender shoots of grasses or other flowering plants. The somewhat different diets of males and females might be explained in terms of the nutritional needs of the latter for egg production (Hochkirch et al., 2000). Feeding is generally accompanied by frequent antennation of the substrate, and probing with the palps (see DVD).

The females are relatively inactive, and spend most of their time resting or feeding on the ground or among detritus, while the males spend much of their time actively searching for potential mates, especially in the afternoon. Initial location of a female is probably visual, but, in close proximity, males frequently point their antennae directly towards the female and ‘twirl’ them in a way that suggests that scent may be involved. Commonly, but not always, the male faces the female and performs a very brief courtship signal. Hochkirch et al. (2006) distinguish two such signals which they term ‘frontal swinging’ and ‘lateral swinging’. Both these signals are of very brief duration (around one second), and involve raising the body of the insect slightly by stretching the fore and mid legs and swinging forward, or stretching the legs on one side to produce a sideways motion. The amplitude of the signal is very small and it is easily missed by the human observer. However, on film it is readily detectable (see DVD).

The signal may be repeated several times as the male approaches the female. As the approach is usually from the front, he commonly mounts frontally, and climbs onto her pronotum, facing backwards. He then turns around, and, gripping her pronotum with fore and mid legs, curves his abdomen down between the side of the female’s pronotum and the femur of that side. Females appear to vary in their receptiveness, and sometimes males attempt to force their way between these structures. Once this position has been achieved, the male searches with the tip of his abdomen for the genitalia of the female and mating takes place. This is usually very brief – a few seconds only – and is usually accompanied by antennal contact, the male curving his antennae down, the female raising hers. The male disconnects his genitalia from those of the female, dismounts and walks away. Frequently the female continues to feed throughout the operation.

However, this ‘textbook’ sequence is often varied. Competition between males for mates is quite intense, and it commonly happens that the mating attempts of one male are interrupted by the arrival of another suitor. The latter will often attempt to pull off the first, but, if that fails, he will simply clamber over it and attempt to mate from the other side of the female. Sometimes it appears that the second male successfully mates with the female as soon as the first completes copulation and dismounts. Often, if a male fails to elicit the appropriate response from a female he will resume the initial posture, facing backwards while standing on the pronotum of the female. This brings the tip of his abdomen over the antennae of the female. He then reverses to the standard position for copulation and is often successful. Another probable consequence of the intensity of male competition is that males often dash at and mount a female directly and without any observable courtship signal.

In addition to the two ‘swing’ signals described above, both males and females signal to one another by rapidly raising and then lowering one hind leg (or sometimes both). This ‘leg flick’ signal is most often used when males encounter one another, and is followed by one or both moving away.

FIG O. Mating pair.

Another pattern of movement that appears to have a communicative role is a rapid vibration of the whole body that looks like a brief fit of rage or frustration. It could be that this is less a visual signal than a form of vibratory communication that is sensed either by direct physical contact or via the substrate (Benediktov, 2005). However, what appears to the human eye as the same ‘vibration’ signal is used in a range of different contexts. Most frequently it is used when two or more males encounter one another. In a head-on encounter, one or both may vibrate and one moves off. Sometimes one male climbs onto another, which then vibrates until the first dismounts. This is sometimes followed by a fit of vibration from the first. In fact, males frequently make physical contact with one another, sometimes climbing onto or over one another, and often with mutual antennation or vibratory signals. Hochkirch et al. (2006) interpret this as indicating that males will attempt to mate with more or less anything of roughly the right size. Occasionally, indeed, these encounters do look like mating attempts, but more often they have the appearance of mildly antagonistic or neutral contacts. The locations where individuals congregate and perform courtship and mating appear to be strongly physically delimited within the wider habitat. It could be that these contacts function in some way to maintain the cohesion of localised aggregations, which could be important for mate location in a species without sound communication that lives in habitats offering little long-distance visibility.

Where T. ceperoi and T. subulata occur together (as they do in some British localities, such as Rye Harbour), males of both species mis-direct courtship and mating attempts to females of the ‘wrong’ species (see under T. ceperoi).

In laboratory tests of reproductive interference between T. subulata and T. undulata (Hochkirch et al., 2008a), males of both species showed a strong preference for females of T. undulata, while females of each species were equally receptive to males of either. This may be because of the close similarity of the courtship signals of the males. However, in the field, where the two species intermingle, males of T. undulata seem to court or mate with females of their own species and those of T. subulata in roughly equal proportions. Females of both species accept or resist mating attempts from males of either species without any obvious discrimination. In one extraordinary filmed sequence, a male T. undulata mounts a female T. subulata, but is pulled off by a rival male T. subulata, which then walks over the male T. undulata (eliciting a fit of vibration from the latter), to successfully mate with the female T. subulata. She then wanders off and re-encounters the original male T. undulata, who promptly mounts and successfully mates with her! (See Chapter 6 for more details, and the DVD.)

Enemies

There appear to be no literature reports of predation on groundhoppers, but it is possible that they are taken by water-side birds, amphibians or, like many other orthopterans, by spiders.

Loss of one of the back legs is common in most populations, and it is sometimes assumed that this is evidence of predation (autotomy is used by orthopterans as a means of escape from predators) but it may also be a result of imperfect moulting of nymphal cuticle during development. Cryptic coloration and the apparent tendency to select matching substrates must be an important defence against visual predators. However, when basking, and sometimes when feeding, they rest on contrasting substrates, presumably reflecting a trade-off between those priorities and predator avoidance. Their most common response to disturbance is to jump – often landing on a colour-matching surface. Especially in warm weather, they may respond by flying some four or five metres, and they can change direction to some extent while in flight. Like the other two groundhopper species, they are able to swim, using powerful kicks of the back legs. This is presumably an aid in escaping from terrestrial predators.

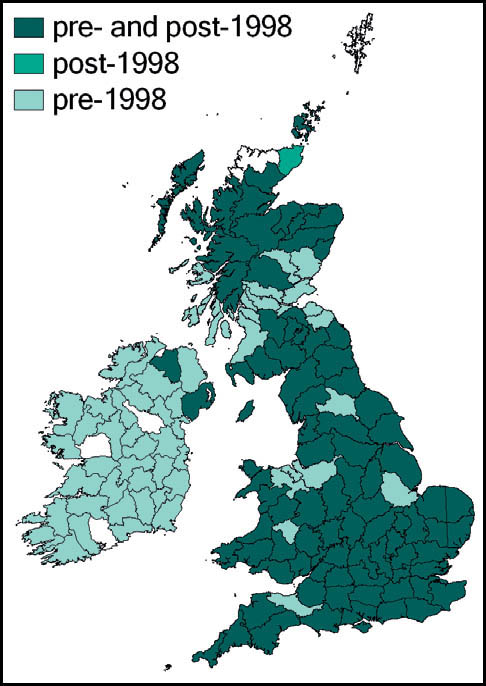

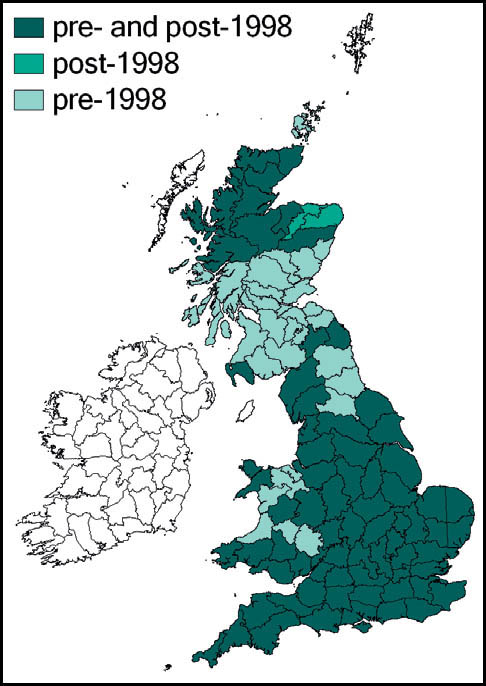

Distribution

This species has a very wide distribution throughout the temperate regions of the northern hemisphere, including most of Europe, temperate Asia, north Africa and north America. In Britain it is common and widespread in south-western, central-southern and south-eastern England and East Anglia. Kevan (1961) gives north Lincolnshire as its most northerly outpost, but it has since been recorded from Lancashire and Yorkshire (Drax power station, at Selby in 1998), and subsequently in a number of other localities in Yorkshire (Sutton, 2005a). There is also a scattering of records from southern and some eastern counties of Wales, and across Ireland.

Status and conservation

It seems likely that many of the slender groundhopper’s localities are rather temporary and vulnerable to shading out of the required bare patches by vegetative succession, and to the drying out of ponds and damp hollows. Extensive drainage of wetlands for agriculture must also have greatly affected its populations. However, it appears to be a relatively effective coloniser of newly created habitats and is regarded as a ‘pioneer’ species. Careful searching of any apparently suitable habitat within its climatic range generally reveals its presence. In view of this, it seems unlikely that this species is significantly threatened in Britain.

References: Hochkirch et al., 2000, 2006, 2008a; Gröning et al., 2007; Kevan, 1961; Sutton, 2005a.

COMMON GROUNDHOPPER

Tetrix undulata (Sowerby, 1806)

MEASUREMENTS: Male: 8–9 mm in length; female: 9–11 mm in length.

FIGS A–C. Male; male dorsal view; female.

Description

The common groundhopper is a more compact, robust insect than its two close relatives. This appearance is partly the result of the much shorter rear extension of the pronotum, the tip of which reaches back only so far as, or a little beyond, the rear end of the abdomen and genitalia. The reduced hind wings are largely concealed under the pronotum with just a narrow section of the leading edge visible below it, and to the rear of the small ridged pads that are the reduced vestiges of the fore wings. The longitudinal ridge on the dorsal surface of the pronotum forms a prominent keel in this species and has a convex outline when viewed from the side, giving a slightly ‘hump-backed’ appearance to the insect. The curvature is even in the male, but more abrupt towards the front of the pronotum in the female.

There is an uncommon fully-winged form (f. macroptera Haij) listed from two Scottish sites by Kevan (1952), and, more recently in 1991, also from Scotland (Haes & Harding, 1997).

As in the other groundhoppers, there is a great diversity of colour forms and many of these are similar in all three species – possibly reflecting their overlapping habitat preferences. (See Chapter 3, Fig 72.)

Similar species

The adults of this species can easily be distinguished from those of the other two British groundhopper species by the much shorter pronotum, and also by the raised central keel along the pronotum. However, confusion with the short-winged form bifasciata of the slender groundhopper is possible. The prominent keel in the common groundhopper is the most obvious distinguishing feature here. Early instar nymphs of all three species are very difficult to distinguish, but in the final nymphal instar the hind wing pads are clearly visible in the other two species, but not in T. undulata.

FIG D. Nymph.

Life cycle

Although they are reputed to be active in warm days through the year, common groundhoppers are rarely seen before the middle of March in southern Britain. However, by the end of that month they are very active in good weather. Courtship and mating begins at that time, and continues for much longer into the summer than is the case for the other two groundhopper species. The eggs, which are similar in form to those of the other groundhoppers (see under slender groundhopper), are laid into the ground or among low vegetation. They hatch in 3 to 4 weeks. Subsequent development is as in the other groundhoppers – an initial vermiform larva gives way to a series of five (in the male) or six (in the female) nymphal instars – but as the breeding season is more extended in this species, both adults and nymphs of various stages can be found together through the year. Overwintering nymphs complete their development the following spring, and so become fully adult later in the season than those that overwintered as adults.

Habitat

As noted by many observers, this species can be found in a much wider range of habitats than the other two British species of groundhopper. However, it does have markedly overlapping habitat preferences, so that the damp pond margins, stream edges and hollows where the slender groundhopper occurs frequently harbour this species too. It also inhabits a range of other biotopes: along path edges and in clearings in open woodland – especially among mosses and leaf litter, and on heathland among gorse and heathers. A key requirement seems to be patches of bare ground open to the sun, and plants such as algae and mosses that form its main diet. Even in apparently suitable habitat the population is often aggregated in small local patches.

Behaviour

Common groundhoppers are inactive in cool or overcast weather, and on warm, sunny days divide their time between basking, feeding and reproductive activity. Females are most often seen on the ground, feeding on various small plants, while males are generally more active. When not feeding or basking, they run in a rather jerky fashion on haphazard routes around open patches, or through leaf litter. This is presumably a mate-searching strategy, as when a female is approached the male generally stops, facing the female. Several brief and inconspicuous ‘swinging’ courtship signals may be given before the male moves forward, often making antennal contact with the female and mounting. Mounting is often from the front, so the male is initially standing on the pronotum of the female, facing backwards. He quickly turns around and probes with his abdomen to open a space between the hind femur and pronotum of the female. If the female is receptive, she allows this and the male then rubs his abdomen against that of the female and reaches down to make contact with her genitalia as she curves her abdomen in his direction. Mating usually lasts only a few seconds, and the male moves off, usually with the tip of his abdomen drooping, and the genital plates still parted.

However, there are many deviations from this pattern. Often males appear to approach directly, and mount and attempt to mate either without any obvious preliminaries, or with antennal contact only. In some examples, apparent female resistance is overcome by a mounted male reversing his position on the pronotum of the female, then reverting back to the normal mating position. One filmed sequence shows a female lacking one hind leg. A male who mounts her appears confused, dismounts, re-mounts and dismounts a further two times, despite her opening the space between her pronotum and the remaining hind femur. The sequence is completed by her walking over him, leaving him in a fit of vibration!

During their mate-searching activity, the males frequently encounter one another. When they do so, a variety of signals ensues. Commonly, two males exchange ‘leg flick’ signals with their hind legs. This usually results in one of them departing. On other occasions one or both of two adjacent males will perform a rapid up-down vibration, followed by the departure of one of them. On still other occasions, the initial ‘leg flick’ signal is ignored by another approaching male who may simply climb onto the first. This usually elicits strong vibration from the underling until the other dismounts, and is often followed by a subsequent fit of vibration on the part of the ‘abused’ male. As in T. subulata, many of these interactions between males do not appear to involve mating attempts, and may possibly have some function either in male-to-male competition, or in maintaining the cohesion of the local population.

FIG E. Male slender groundhopper attempts to mate with female common groundhopper.

These interactions between males are often replicated when males of T. undulata encounter male T. subulata. Where the two species mingle (as is very frequent in the damper parts of the habitat of T. undulata), courtship, mating attempts and mating between the two species are common (Hochkirch at al., 2006, 2008a; see under T. subulata; and see also Chapter 6 for more detail, and the DVD).

Enemies

As in the other groundhopper species, the cryptic coloration, and the associated behavioural disposition to settle on colour-matching surfaces, suggests selection by visual predation. Although camouflage appears to be their best defence, they are effective jumpers and, like their relatives, good swimmers.

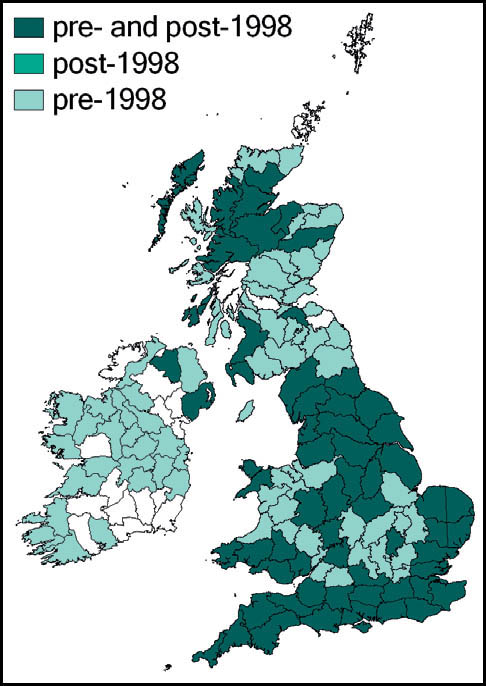

Distribution

This species is widespread throughout most of Europe, except for southern Spain and northern Scandinavia.

T. undulata is widespread throughout Britain, and has even been recorded in the Outer Hebrides (Barra and, more recently, South Uist (Sutton, 2007e)) and Orkney. In the Scottish highlands there are strong populations in ancient pine and birch woods (Marshall & Haes, 1988). In Monmouth it is recorded at altitudes up to 300m (Sutton, 2008a).

It also appears to be widespread in Ireland. Although there are gaps in the available distribution maps, this probably results from under-recording of this cryptic insect.

Status and conservation

Although T. undulata is a widespread and often abundant species, it has quite exacting habitat requirements and is vulnerable to vegetation succession as well as to habitat loss to agriculture and ‘development’. Unlike its sister species, T. subulata, it cannot fly and is likely to be relatively poor at dispersal to new sites. It is unclear whether the rare occurrence of the macropterous form is related to dispersal ability.

References: Haes & Harding, 1997; Hodgson, 1963; Hochkirch et al., 2006, 2008a; Kevan, 1952; Marshall & Haes, 1988; Sutton, 2007e, 2008a.

GRASSHOPPERS (ACRIDIDAE)

There are eleven British species in this large family. They are familiar, often abundant, inhabitants of grassland and heath. The pronotum is saddle-shaped and usually has a median keel along the dorsal surface, and a keel on each side-edge. There is also a groove, or sulcus, that cuts across the dorsal surface of the pronotum at approximately the middle. The shape of the side-edge keels and the position of the transverse sulcus are often crucial characteristics for identification.

The head bears a pair of relatively short and thickened antennae (sometimes broadened at the tip). The mouthparts are adapted for chewing vegetable matter – usually grass-blades. The female has a short, inconspicuous ovipositor, composed of two pairs of valves, while the male has an up-turned subgenital plate at the rear end of its abdomen, so the different shape of the tip of the abdomen is a useful way of distinguishing the sexes.

Stripe-winged grasshopper (© Tim Bernhard)

THE LARGE MARSH GRASSHOPPER

Stethophyma grossum (Linnaeus, 1758)

MEASUREMENTS: Male: 22–9 mm in length; female: 29–36 mm in length.

FIGS A–E. Male; male dorsal view; female; female dorsal view; dark female.

Description

This is the largest of the British grasshoppers – and perhaps the most beautifully patterned. The wings are fully developed, although varying in length to some degree – extending almost to, or a few millimetres beyond, the tip of the abdomen. The leading edge of the fore wing bulges outwards towards the base. The side keels of the pronotum are gently incurved, and diverge laterally on the rear portion of the pronotum. The cerci are relatively long in the male, and the valves of the female ovipositor are long and distinctively shaped. The aperture of the hearing organ is wide, and clearly visible on each side at the anterior end of the abdomen.

In this species the colour patterns are quite distinctive, although variable. In both sexes the hind legs are ringed with black – usually around the ‘knees’, and often with other contrasting black patches on the femora or tibiae. The femora are bright red ventrally. The colour pattern of the males is usually more contrasting than that of the females. The dorsal surface of the head and pronotum is usually olive-green (sometimes brownish), shading to yellow laterally, and on the fore and mid legs and hind tibiae. The side keels of the pronota are outlined in yellow, and there is a black band along each side of the head behind the eye. The abdomen is green, shading to yellow ventrally, with variable black markings on each segment.

The females are usually olive green, shading to greenish yellow on the sides and underside of the abdomen, with the legs frequently green, rather than contrasting yellow, as in the males. In both sexes the fore wings are usually tinted brown, usually with a yellow stripe along the leading edge. There is often black on the paranota as well as on the sides of the head.

In some females the olive-green shades to greyish brown, and there is an uncommon purple form.

Similar species

This species is quite unlike any other British species. Its large size and colour pattern on the hind femora are unique.

Life cycle

The adults emerge rather late in the season, usually from the last week in July onwards. They continue through August and September, into October. The eggs are laid in batches of up to 14 at the base of grass tufts, enclosed in an elongated pod. They enter a resting-stage, and do not hatch until May or early June the following year. The nymphs pass through five instars before emerging as adults later in the summer.

Habitat

Earlier in the last century, this species inhabited a wider range of wet habitats than is the case now in Britain, including rough, wet meadows, marshes and moorland, as well as wet heaths. Further south, in Europe, it still does. According to Lucas (1920) it was found among rank grasses by the river Bure in Norfolk in 1892, and it formerly occurred in the Norfolk broads, the fens of Cambridgeshire, and the lower Thames marshes. In the west of Ireland it is still found by rivers and lakes, in Normandy it is found in ‘fairly dry’ riparian grassland (Sutton, 2007b), and in the Swiss Alps it occurs on rocky banks of mountain streams (pers. obs.).

Its current strongholds in England are acidic quaking bogs, often associated with purple moor-grass (Molinia caerulea), bog myrtle (Myrica gale), cross-leaved heath (Erica tetralix), Sphagnum mosses, broad-leaved cotton grass (Eriophorum latifolium) and white-beaked sedge (Rhynchospora alba). It is usually found in the wettest parts of such habitats, which it shares with few other orthopterans, although it is often found in the same habitat as the bog bush-cricket (Metrioptera brachyptera), especially in the New Forest and Dorset heaths.

Behaviour

For such a large and spectacular insect, the large marsh grasshopper is surprisingly difficult to spot. On warm days the males produce their unique ‘ticking’ stridulation by flicking one hind leg (sometimes both, but out of synchronisation) against a wing tip. The sound is repeated in bursts of four to ten at a rate of two to three per second. Usually the male is static while stridulating, but continues to move through the vegetation before delivering its next burst. However, sometimes a male delivers several bursts from the same perch, in alternation with a nearby competitor (see DVD). The ‘song’ is frequently produced from a perch as much as 20 or 30 cm above the ground, from the stem of a rush or small shrub. The male is very alert while stridulating, and any sudden movement from the observer sends it running backwards and down into the undergrowth. More active disturbance, especially in warm weather, results in the grasshopper taking to the wing, in a swift, direct flight path, often of 10 metres or more. Lucas’s (1920) description of its flight and associated escape behaviour could hardly be bettered:

FIG F. Male on song perch.

One that flew near me had its long legs stretched out behind it, like those of a heron on the wing. When stalked it sometimes rises once or twice, but if thoroughly disturbed hides amongst the rank bog vegetation, with which its colours so harmonise that it is seldom again found… (Lucas, 1920: 228)

The females are usually less active, and are frequently seen lower down among low-growing plants such as Sphagnum moss. Both sexes are reluctant to fly in cool weather, and rely on their camouflage and ability to disappear into deep cover if alarmed.

They feed on blades and stems of grasses, rushes and sedges, sometimes biting through stems of rushes to access the more nutritious seed heads.

Enemies

Lucas (1920) reports having seen a male of this species being carried off by the hornet robber-fly, Asilus crabroniformis. Its cryptic coloration and the alertness of the males while stridulating suggest adaptation to visual or auditory predation – presumably from birds.

Distribution

This species is widespread (but not common, owing to its distinctive habitat requirements) throughout Europe north of the Alps, and northwards in Scandinavia to approximately 68 degrees latitude. It occurs in wet grassland and seepages in the Alps up to 2,400 metres. It is localised in northern Spain and north Italy. In the east, its range extends through eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union to Siberia.

This species has not been recorded in England north of a line from the Bristol Channel to the Wash, and even within its range it has always been restricted by its habitat requirements. It has not been recorded from Scotland or Wales, but is present in the west and south of Ireland.

It was regarded by Burr (1936) as extinct in the Cambridgeshire fens as a result of drainage, and has also been lost from its Norfolk and Thames-side localities (Marshall, 1974).

A population discovered in the Somerset Levels in 1942 was adversely affected by peat cutting and agricultural intensification. Since the 1980s there were records only from Shapwick Heath (1989) and Westhay Moor (1995), until a single specimen was reported in 2006. However, subsequent searches of the locality have proved unsuccessful (Sutton, 2007d).

It was deliberately introduced to Thursley Common, Surrey, in 1967 (Marshall & Haes, 1988) but appears to have become extinct both there, and also in what may have been a natural habitat in Surrey, where it was found in 1982. Subsequent searches of this locality have not been successful (Baldock, 1999; Sutton, 2003c).

Currently, the species appears to be confined to sphagnum-dominated mires in heathland in east Dorset and the New Forest, Hampshire. However, where suitable habitat exists in these areas, it maintains substantial populations.

Status and conservation

Haes (in Shirt 1987) rated it ‘vulnerable’, and considered the main threats to be drainage and shading of its habitat by afforestation.

As the species survives in a wider range of habitats in mainland Europe, it might be speculated that, with predicted warming of the UK climate, it might adopt a wider range here, and still be retained even if its current habitats in Dorset and Hampshire become too dry for it. Sutton (2007b) is sceptical about this possibility, however, as the Norfolk, Cambridgeshire, Surrey and Somerset populations were lost as habitat dried out.

However, reported extensions of its range in the Netherlands give rise to some cautious optimism (Sutton, 2008b), and the projected restoration of former East Anglian fens might allow for its reintroduction to that part of its range.

In the west of Ireland, it is threatened by peat extraction.

References: Baldock, 1999; Burr, 1936; Harz, 1975; Kleukers & Krekels, 2004; Lucas, 1920; Marshall, 1974; Marshall & Haes, 1988; Ragge, 1965; Shirt, 1987; Sutton, 2003c, 2007b, 2007d, 2008b.

THE STRIPE-WINGED GRASSHOPPER

Stenobothrus lineatus (Panzer, 1796)

MEASUREMENTS: Male: 15–19 mm in length; female: 17–22mm in length.

FIG A–D. Male; male dorsal view; face; female.

Description

This handsome, medium-sized grasshopper is best identified by the unique pattern formed by the veins in the fore wings. The median area of each wing is enlarged, and the cross veins form an almost parallel series, giving a ladder-like impression. Both pairs of wings are fully developed; they reach to just beyond the tip of the abdomen in males, but are often significantly shorter in females. There is no bulge on the leading edge of the fore wing. The side keels of the pronotum are moderately inflexed or incurved, and diverge toward the rear edge of the pronotum. The males have from 300 to 450 minute stridulatory pegs on the inner surface of each hind femur, and a rather elongated subgenital plate that tapers to a point. In the female, the ovipositor valves (which usually protrude slightly from the rear end of the abdomen) have a small tooth (see the Key, Fig K21b).

There is considerable variation in colour pattern, but what is probably the most common form is green on the head, pronotum and rear edges of the wings (forming a tapering green dorsal ‘roof’ over the abdomen when the insect is at rest). The green shades paler down the sides of the pronotum and head, and may be considerably paler on the face, with palps sometimes white. The eyes vary from fawn to darker brown. The side keels of the pronotum are outlined in whitish to cream or pink, edged with black externally in the anterior part of the pronotum, and internally on the posterior part. The pale lines are continued forward onto the head and eventually meet at the front of the head. The wings often appear dark brown to black, but are paler in freshly emerged specimens. There is usually a white stripe close to the leading edge of the fore wing, and a white spot, or ‘stigma’ towards the outer tip. However, one or both of these may be absent. The upper (anterior) surface of the hind femora is commonly green, but may be fawn, brown, pinkish, or even purple.

A minority colour form has the green on the top of the head and pronotum and the rear margins of the fore wings replaced by brown or grey-brown, with a pale median longitudinal stripe on the top of the head and pronotum. In this form, the sides of the head and pronotum are green, but the anterior edge of the hind femora is generally brown. There is also a rare form in which the head, pronotum and hind legs are pink (B. Pinchen, pers. corr.)

In newly emerged individuals, the abdomen is pale grey, with dark brown patches on the sides of most segments. However, with sexual maturity, the hind three to four segments and genital plate become bright red in the male. The colour often extends further up the abdomen, and also suffuses the hind tibiae and posterior edge of the hind femora. Similar, but less spectacular colour changes also occur in the females, with orange coloration on several of the abdominal segments.

FIGS E–F. Two-colour forms.

Similar species

The wing venation is the best diagnostic feature to use, but this is not always obvious in the field. The male ‘parsons nose’ subgenital plate, and the toothed ovipositor valves in the female are also reliable characters, but still less easy to use in the field.

The most closely similar species, and one that often occurs together with the striped-winged, is the common green grasshopper (Omocestus viridulus). Many colour forms of this have brown or grey paranota, but in the stripe-winged grasshopper, these are always green, even in the ‘brown’ form. However, the fully green form of the common green grasshopper can look very similar indeed to the stripe-winged. Useful clues are:

These indications are not entirely reliable, however, and for full confirmation anatomical characters should be used. In addition to the wing venation and shape of the male subgenital plate, these include the shape of the valves of the ovipositor in females: elongated and untoothed in the common green grasshopper.

Other species that could be confused with the stripe-winged grasshopper include the following:

Life cycle

The eggs are laid during the summer above the surface of the soil, among the bases of tufts of grasses. The pods contain up to eight eggs, and are oval in shape, with plant fragments attached to the outer coating. The eggs remain dormant through the winter, and hatch in April or May the following year. The resulting nymphs pass through four instars prior to reaching adulthood by June or July. In favourable seasons and localities they may reach adulthood as early as the first week in June, becoming fully sexually mature a little later. The adults continue to be active through July, August and September, with a few surviving until October.

FIG G. Final instar nymph.

Habitat

The stripe-winged grasshopper favours rough, uncultivated and well-drained grasslands and heaths. It is often found, along with the rufous grasshopper (Gomphocerippus rufus), on south-facing, rabbit-grazed downland slopes. Elsewhere it is also found on the drier parts of heather heaths and on sandy, acid soils, as on the Suffolk heaths, and the Brecks of East Anglia. In the latter habitat it favours areas with bare ground and sparse vegetation, consisting of mosses, lichens and fine grasses, adjacent to areas of longer grass and scrub and often in association with rabbit activity.

Behaviour

Both sexes are well camouflaged in their habitat, the females, especially, being rather inactive and staying close to the ground. Both males and females retreat into deeper cover when disturbed, but also can fly effectively. If pursued, they frequently fly towards their tormenter, a very effective surprise tactic. The males are more active than the females, often wandering about and pausing every few seconds to produce a burst of stridulation. Because of the densely packed stridulatory pegs on the hind femora, the sound can be produced by a rather slow movement of the legs against the wings. Usually both legs are moved, usually out of synchronisation, and the resulting sound is a very distinctive ‘wheezing’ that lasts for some 10 to 20 seconds. Sometimes only one leg is used, and individuals that have lost a hind leg can still stridulate. The song is rather quiet and unobtrusive, and one frequently sees the slowly moving hind legs of a male before hearing the song. In the presence of a female, the character of the sound changes to a ‘courtship’ song.

In a prolonged film sequence of the courtship of this species, the male faced the female, a few centimetres away, and produced a quiet stridulation by rapid, low amplitude vibrations of the hind femora against the wings. This was continued for many minutes until the female moved off. She was soon re-found by the male who then continued with his low-amplitude stridulation (see DVD for clips of this). However, Ragge (1965) describes a more elaborate courtship pattern, consisting of an alternation between an extended version of the normal song, and a more subdued series of ‘ticks’ produced by more rapid leg movements. This continues for some time, culminating in a series of louder sounds produced by quick movements of the hind legs, followed by the male attempting to mate with the female. Ragge notes that the females, too, sometimes stridulate, but it is unclear what part this plays in the mating system of the species.

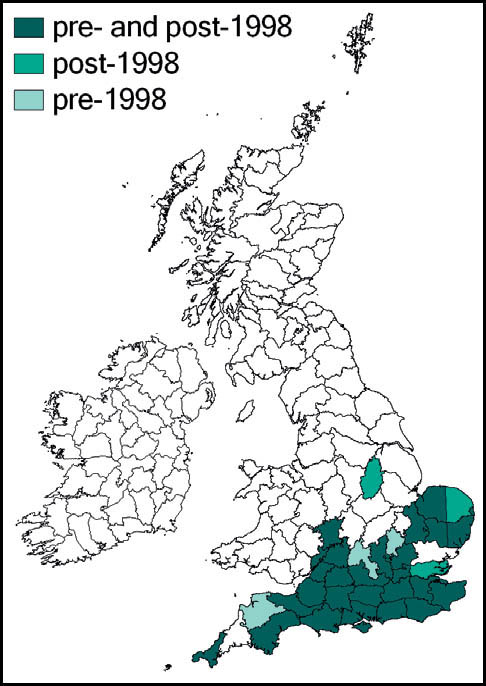

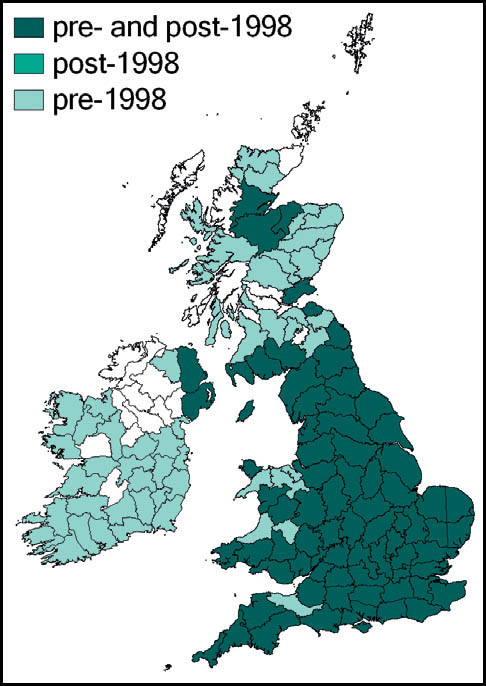

Distribution

The stripe-winged grasshopper is distributed throughout much of Europe, from Spain in the west, through to Siberia and Northern Mongolia in the east. Further south in Europe it is limited to moderate altitudes in mountains, for example, from 1,400 to 2,500 metres in the Alps.

In Britain, it is mainly confined to southern counties and East Anglia, with very few records from Cornwall and Devon. It occurs on the chalk downland of Dorset and the south of the Isle of Wight, and is common and widespread on south-facing slopes of the North and South Downs. Further north, it occurs, but is more localised, on the Mendips, the Cotswolds and the Chiltern hills, and (rarely) as far north as Nottinghamshire. It also occurs on heaths in Hampshire, Surrey and West Sussex, as well as in Suffolk and Norfolk. In the Brecks it is widespread, but thinly distributed on heather heath and dry grassland along rides and clearings in pine forest.

There are some indications that it is spreading into new localities, and possibly also expanding its range (Sutton, 2003c). Richmond reports new records that indicate that the species is spreading from its strongholds in the Brecks (Sutton, 2007d, 2008b, 2011), and it was discovered at a site in Epping Forest (the first Essex record) in 2010 (Wilde, 2009; Sutton, 2010a).

Status and conservation

It seems probable that a combination of agricultural intensification, afforestation and the decline of grazing by rabbits and livestock has rendered this species much more localised than in the past. However, as many of the remaining localities are managed by organisations with a conservation brief, it seems unlikely that this species is seriously endangered. In the Brecks, the open rides and large areas of clear fell associated with current management by the Forestry Commission appear to be very favourable to this species. The recent indications of range expansion could be a response to climate change, and close monitoring of suitable habitat away from its current range would be of interest.

References: Harz, 1975; Kleukers & Krekels, 2004; Lucas, 1920; Marshall & Haes, 1988; Ragge, 1965; Sutton, 2003c, 2007d, 2008b, 2010a, 2011; Wilde, 2009.

THE LESSER MOTTLED GRASSHOPPER

Stenobothrus stigmaticus (Rambur, 1839)

MEASUREMENTS: Male: 10 to 12 mm in length; Female: 12 to 15 mm in length.

FIGS A–D. Male; male dorsal view; female; female dorsal view.

Description

The lesser mottled grasshopper is very small, with gently incurved side-keels to the pronotum. Both pairs of wings are fully developed, but are usually quite short. In the male they reach back almost to the tip of the abdomen, but in females they are relatively shorter – often leaving two or three abdominal segments exposed. The wings are also narrow, without the expanded median zone characteristic of the stripe-winged grasshopper. The male antennae are slightly thickened towards the tip. The ovipositor valves are toothed.

In the most frequent colour pattern, the head, pronotum, side plates of the thorax to the rear of the paranota, and the anterior edges of the hind femora are all bright green. The side keels of the pronotum are outlined in cream to pale brown, with black edging externally on the anterior section of the pronotum, and, somewhat widened as wedges, internally on the rear section of the pronotum.

The pale lines are carried forward onto the head and join at the front of the head. The ground colour of the abdomen in freshly emerged specimens is grey. The fore and mid legs, as well as the outer surfaces of the hind femora, are also grey. The fore wings are fawn to cream in colour, often with a white stripe close to the leading edge, and one or two white stigmata in the outer half of each fore wing. There are often dark brown or black spots along the middle area of the fore wing, and black patches at the sides of the first few abdominal segments. There is a pale brownish rectangular patch at the front of the paranota, and the lower part of the face is creamy white to pale brown.

As the adults become sexually mature, they develop a red tint to the posterior segments of the abdomen, which sometimes extends to almost the whole of the abdomen as well as the legs and wings. This is particularly pronounced in the males.

Two minority colour forms have been noticed. In one of these, the green on the dorsal surface of the head, pronotum and edges of the femora is replaced by pale brown. In another form, all the green is replaced by brown. When this form is suffused with red, the effect is very striking.

Similar species

In general appearance this species is quite similar to its close relative, the stripe-winged grasshopper, although this does not occur in the Isle of Man. The lesser mottled grasshopper lacks the expanded central area to the fore wings, and the associated pattern in the wing venation, that characterise its relative. The subgenital plate in the male is less pronounced in the lesser mottled, and the grey or brownish patch at the front of the paranota in the lesser mottled grasshopper is distinctive, but not evident in all colour forms. The green form of the lesser mottled has fawn-brown rear edges to the fore wings (arched over the back at rest), while the green form of the stripe-winged always has green in this area.

Because of its small size, the lesser mottled grasshopper could be confused with the mottled grasshopper (M. maculatus), which does occur on the Isle of Man. However, that species has much more acutely inflexed side keels to the pronotum, and a noticeably larger head relative to the pronotum. The male antennae of the mottled grasshopper are clubbed, whereas those of the lesser mottled are only gradually thickened towards the tip.

The common green grasshopper (O. viridulus) is also quite similar, but lacks the grey or brownish patches on the paranota, has relatively longer wings, does not develop reddish tints with sexual maturity, and is considerably larger. Although O. viridulus does occur on the Isle of Man it has not been recorded in the habitats occupied by the lesser mottled.

The common field grasshopper (C. brunneus) does have an uncommon colour form that resembles the brown form of the lesser mottled grasshopper, but the field grasshopper has more strongly inflexed side keels and relatively longer wings, and is generally a much larger insect.

Life cycle

The eggs are laid during the summer, and enter a dormant stage over winter. Embryonic development has a high temperature threshold and so the eggs hatch late in the spring. Subsequent development is favoured by warm and sunny conditions that enable rapid ‘catch-up’ nymphal development (van Wingerden et al., 1991; Cherrill & Selman, 2007). There are usually four nymphal instars, but (as in C. brunneus) females sometimes develop through five instars. The adults are present from late July until September.

Habitat

On the European mainland, the subspecies (ssp. faberi) to which the British population is assigned is reported to occur on Calluna heaths, dry meadows and steppe grassland, as well as inland dunes (Harz, 1975) and sheep pasture (Bellmann, 1988). In mainland Europe there is no special association with the coast. On the Isle of Man it exists in discrete colonies on patches of grass and heathers (Calluna vulgaris) and bell-heather (Erica cinerea), in the vicinity of rocky coastal outcrops. It occurs among shorter grasses in company with the mottled grasshopper (M. maculatus), but will tolerate tussocky grassland, where it occurs together with the common field grasshopper (C. brunneus). However, it does not occur in areas of taller grasses, or where heathers and other shrubs have more than 50 per cent ground cover (Cherrill, 1994; Cherrill & Selman, 2007). The habitats favoured by this species have in common that they are warm and dry, with low-growing vegetation on nutrient-poor soils. In most localities moderate grazing by livestock, rabbits or deer seems to be required. Small populations were found close to the rough on the golf course that occupies the landward part of the Langness peninsula, on the Isle of Man (Cherrill & Selman, 2007; see also Chapter 9 for more detail.)

Behaviour

The Manx population seems to live in discrete colonies, with numerous males sharing favoured spots (e.g. a platform of flattened grass stems, or the flat top of a bank). In cool weather they remain inactive, but with an increase in temperature the males run actively through and over vegetation in their ‘patch’. This seems to be a mate-location strategy, and when a female is encountered, males begin a courtship display. Ragge (1965) gives a detailed description of this. The process begins with a burst of soft stridulation lasting from four to six seconds in which one hind leg is moved more vigorously than the other. That leg is then moved quickly downwards to make a louder sound. After a pause of three to seven seconds there is a brief period of noiseless movement of the hind legs, followed by another burst of stridulation, which is like the first, only with the other leg moved more vigorously. The whole cycle is repeated several times, usually culminating with a mating attempt on the part of the male.

Most usually, the males are rejected, the female either jumping away, or moving off more slowly, in which case she is usually followed by the male, who then resumes courtship.

Frequently, two or more males compete with one another in courting a female, in which case antagonistic signals between the males disrupt the courtship routine described by Ragge, and brief bursts of stridulation in this context appear to have more to do with male-to-male communication than courtship (see DVD).

The calling song of the male is a rather subdued ‘chirp’ lasting from two to four seconds, starting soft and becoming louder. It is repeated at irregular intervals, but only in warm, sunny weather.

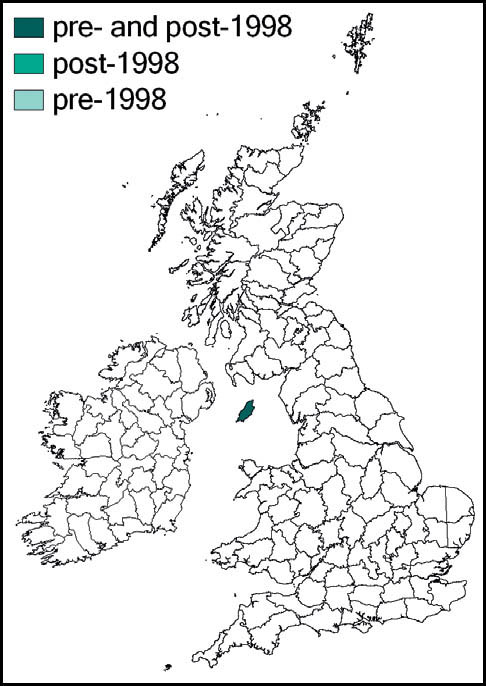

Distribution

Internationally, three subspecies are recognised, but the subspecies faberi, which includes the Isle of Man population, is widespread in central and western Europe, from lower altitudes in the Alps northwards, with north-west Germany marking the northern limit of its range on the European mainland. Eastwards, it occurs through eastern Europe to the western parts of the former Soviet Union.

In Britain it is known only from the southern tip (the Langness peninsula) of the Isle of Man, where it was first recognised in 1962 (Ragge, 1963). This is its northernmost outpost.

Status and conservation

The species is reputedly in decline in mainland Europe, where it is threatened by cessation of grazing on traditional pastures, with subsequent loss of its short-grass habitat through natural succession, and by agricultural intensification and ‘improvement’ of grassland (Bellmann & Luquet, 2009; van Wingerden & Dimmers, 1993).

Given the unique British distribution of this species, there has been some speculation that it might have been an accidental introduction. However, there is no obvious route by which this might have occurred. Also, Manx specimens are smaller than the ones from the continental mainland (the latter given as 11–13 mm (males) and 14–18 mm (females) in length), and this suggests that they may have been isolated for a long time. For both reasons, Ragge (1965) and Burton (1963) tentatively concluded that S. stigmaticus is probably a native species.

A species whose British distribution is as highly localised as that of the lesser mottled grasshopper must be considered vulnerable, despite its inclusion in the Isle of Man Wildlife Act of 1990, Section 5, and the inclusion of its habitat in a designated ASSI. An application to extend the existing golf course into the part of the peninsula occupied by the grasshopper was rejected at a public enquiry in 1990. However, the habitats continue to be privately owned, and there remains a question about appropriate management for the species. Grazing by sheep and cattle ceased around 1985, and it seems that parts of the habitat became unsuitable for S. stigmaticus as a result of the development of a tall, cool grass sward and encroachment by scrub (Cherrill & Selman, 2007). Resumption of grazing in one part of the peninsula in 2003 had resulted in recolonisation by the time the site was surveyed in 2006. Although rabbit grazing on habitat close to the rocky shore line may be adequate to maintain the habitat, the security of the species in its only known British locality will depend on appropriate management over the whole of the site. In the longer term, it is possible that some parts of the habitat will be threatened by sea-level rise.

References: Bellmann, 1988; Bellmann & Luquet, 2009; Burton, 1963; Cherrill, 1994; Cherrill & Selman, 2007; Evans & Edmondson, 2007; Harz, 1975; Marshall, 1974; Marshall & Haes, 1988; Ragge, 1963, 1965; van Wingerden et al., 1991; van Wingerden & Dimmers, 1993.

THE WOODLAND GRASSHOPPER

Omocestus rufipes (Zetterstedt, 1821)

MEASUREMENTS: Male: 13 to 17.5 mm in length; female: 18 to 22 mm in length.

FIGS A–G. Male; female dorsal; female; male face; female face; male; dark male dorsal.

Description

This is a medium-sized grasshopper, with both pairs of wings fully developed, reaching back to or beyond the tip of the abdomen in both sexes. There is no bulge on the leading edge of the fore wings. The transverse groove (sulcus) on the pronotum is anterior to the midpoint, and the side keels are strongly incurved. The ovipositor valves are short, and without teeth. The male has 90 to 130 stridulatory pegs on each hind femur.

In both sexes the side keels of the pronotum are finely outlined in white, but this may be obscured in very dark males (Fig G). When fully mature, males may be mainly black, with brown on the dorsal surface of the head, pronotum, rear-margins of the fore wings (folded over the abdomen when at rest), and the distal part of the hind femora. In these specimens, the final segments of the abdomen, the tibiae and sometimes part of the femora are bright red. The black of the face contrasts sharply with the chalk white of the palps.

The females are more variable in colour, but have two main colour forms: green and brown. In the green form, the top of the head, the pronotum and the rear edge of the fore wings are a rather dull green, sometimes shading paler medially. The white outlining of the side keels of the pronotum is clear, and bordered on the inner edge by black wedge-shaped marks on the rear section of the pronotum. The sides of the head, the pronotum and the hind femora vary from greyish through to chestnut brown. The palps, as in the male, are white, although they contrast less strongly with the face. The abdomen is greyish, with an orange-red flush on the hind segments in mature females, and black patches on the sides of the anterior segments. There are dark blackish blotches along the middle of the fore wings, usually with a white stigma towards the tip.

In the ‘brown’ form of the females, greyish or olive brown replaces the green dorsally, and the black wedge-shaped marks on the dorsal surface of the pronotum are larger, and continue to the rear margin of the pronotum.

FIGS E–F. Female with grey sides; brown female.

Similar species

The fully mature male is unmistakable, given its extensively black and red coloration, and the white palps are decisive in identification.

Either form of the female could be confused with one or other colour form of the common field grasshopper (Chorthippus brunneus). That species has more sharply inflexed side keels to the pronotum, and a small bulge on the leading edge of the fore wing which is absent in the woodland grasshopper.

The green form of the female could be confused with the following.

The ‘brown’ form of the female can be confused with the heath grasshopper (Chorthippus vagans). This rare species is sometimes found close to woodland grasshopper habitat on heathland, and is very similar in appearance to the brown form of the female of the woodland grasshopper. A useful (but not entirely reliable) field character is that the anterior (upper, when at rest) edges of the hind femora of the heath grasshopper are usually pale brown and quite distinctly marked with dark brown blotches. The hind femora of the brown form of the woodland grasshopper are usually more uniformly coloured or mottled. More reliably, the transverse sulcus on the dorsal surface of the pronotum in the heath grasshopper cuts across the pronotum at the midpoint, or slightly posterior to it (so that the front section of the pronotum is equal to or slightly longer than the rear section), whereas in the common green grasshopper, the sulcus is further forward. Finally, the fore wings of the heath grasshopper have a small bulge on the leading edge, which is absent in the woodland grasshopper.

Life cycle

The eggs are laid from June to September in batches of five or six, and enclosed in a pod with a convex lid. The pods are deposited just below the surface of the soil, and the outer wall includes soil particles. The eggs hatch in April or May, depending on weather conditions, and the resulting nymphs pass through four instars to reach adulthood in June or early July. As the adults emerge early in this species, they are among the first to die off in late summer and early autumn. In southern France and Switzerland the species completes two full life cycles in the year, with adults present from April to June, and again from August to November (Bellmann & Luquet, 2009).

Habitat

In southern England the woodland grasshopper – as its name suggests – is to be found in open woodland, woodland edges, rides and clearings. For the first few years after clear felling or coppicing, numbers can increase very quickly. However, they decline again with woodland succession, and the species often seems to disappear altogether from a site. It appears to favour ancient deciduous woodland, but can also be found in conifer plantations.

An alternative habitat is moist or dry heathland, where it occurs in grassy hollows, often with heathers, but usually close to patches of gorse or other scrub, or stands of trees. This is characteristic of its habitat in the New Forest, Hampshire. In Cornwall it occurs on heathy areas and sea cliffs, away from woodland (Haes & Harding, 1997).

Further south in Europe, it is reported to live in a much wider range of habitats, including dry pine forests, dunes, and rocky slopes (Kleukers & Krekels, 2004; Bellmann & Luquet, 2009).

Behaviour

The calling song of the male is usually delivered from a perch above the ground – on low scrub or a tall grass stem. The hind legs move rapidly over the fore wings, almost synchronously (although in anticipation of a burst of song the male usually raises one leg). The stridulation begins noiselessly and slowly builds in intensity (although never becoming loud!) and stops suddenly. It may last from five to twenty seconds, and consists of a continuously repeated rapid series of ‘ticks’. The resulting sound resembles that of a stick being drawn very rapidly across a set of railings (see DVD).

The courtship song consists of repetitions of the calling song, followed by a modified and quieter version of it ‘in which the hind legs are vibrated in a rather ragged manner’. One or more quick downstrokes of the hind femora then follow and lead to the male’s mating attempt (Ragge, 1965, 1986).

Virgin females apparently also stridulate, but it is not clear what role this has in their mating system.

Both sexes are inactive in overcast weather, and spend much of their time basking during sunny spells.

Distribution

The woodland grasshopper is widely distributed through Europe, especially in the south. It occurs in Spain and Portugal, through France and central Europe to Rumania and Bulgaria, and on to Turkey, Kazakhstan and southern Siberia. Its European distribution extends northwards into Norway and Finland.

In Britain it is confined to the southern counties, with some coastal records further north, in East Anglia. It has a scattered presence in coastal districts of Cornwall and in south Devon, one known locality in Somerset, and numerous sites in Dorset. However, its strongholds are in Hampshire (especially the New Forest) and in wooded areas of Surrey and Sussex, including the North and South Downs. It is common in parts of east Kent, but there is only one past record for Essex (from J. H. Flint, 1974, cited in Wake, 1997). However, after considerable unsuccessful searching of the area, Wake concluded that the record must be considered doubtful. Subsequent searches of coastal heathland in Suffolk, where the species were recorded in the 1990s by Mike Edwards (pers. corr.) proved unsuccessful, until the species was rediscovered by T. Gardiner in 2011 (pers. corr.). However, the tendency of this species to undergo wild fluctuations in population in response to heath and woodland management could well explain the failure to re-find it in these localities.

North of the river Thames, the woodland grasshopper is either absent or very localised. However, there are recent reports from north Gloucestershire – the northernmost known localities of the species in England – that indicate range expansion (Sutton, 2003c, 2010b).

Status and conservation

This species is abundant in its favoured localities, but is vulnerable to shading out of its woodland habitats. It may have benefited from modern forestry methods in the Weald of Kent and in east Kent (Marshall & Haes, 1988). As it is at the northern limit of its European range in southern England, its distribution is very localised in the northern fringes of its distribution in this country. However, with climate change it is possible that the reports of its range expansion in Gloucestershire herald a more general northerly spread. Suitable habitats at and beyond its range boundary should be carefully monitored.

References: Bellmann & Luquet, 2009; Haes & Harding, 1997; Harz, 1975; Kleukers & Krekels, 2004; Marshall & Haes, 1988; Ragge, 1965, 1986; Sutton, 2003c, 2010b; Wake, 1997.

THE COMMON GREEN GRASSHOPPER

Omocestus viridulus (Linnaeus, 1758)

MEASUREMENTS: Male 15 to 19mm in length; female 17 to 22 mm in length.

FIGS A–D. Green male; green female; brown male dorsal view; greysided female.

Description

This medium-sized grasshopper has fully developed wings, reaching back almost to the tip of the abdomen in females, and usually to a few millimetres beyond in males. There is no bulge on the leading edge of the fore wings. The side keels of the pronotum are strongly incurved, and the transverse sulcus is anterior to the midpoint of the dorsal surface of the pronotum. The ovipositor valves in the female are elongated and untoothed. The male has from 100 to 140 stridulatory pegs on each femur.

There is considerable variation in colour patterns, the males having ‘green’ or ‘brown’ forms.

The green form has a green head, pronotum (including paranota), hind femora, and rear edge of the fore wings (above when at rest). The side keels of the pronotum have a whitish outline, with black edging externally on the front section, and narrow wedge-shaped black markings internally on the rear section. The lower part of the face, and the antennae, palps and abdomen may be green, grey or brownish. The eyes are brown, and there are dark brown to black markings on the abdominal segments. The main central area of the wings is brown, shading to black towards the tip, often with a white stigma.

The ‘brown’ form of the male is more variable, possibly as a result of colour changes occurring with age. This form has brown replacing the green on the dorsal surface of the head and pronotum, and the rear edge of the fore wings. However, the side of the head and face, the paranota and the hind femora vary in colour from olive-green through grey to pale brown, often with black mottling. The sides of the abdomen often have larger areas of black on each segment in this form, and the black wedge-shaped markings on the dorsal surface of the pronotum are wider than in the green form, giving a rather striped appearance when viewed from above.

The females are green on the dorsal surface of the head, the pronotum and the rear edge of the fore wings (sometimes the green on the fore wings is more extensive, reaching the leading edge of the wing basally). There is sometimes a pale median line along the dorsal surface of the head and pronotum. The side keels of the pronotum are outlined in whitish, and they are edged with black, as in the male, but the black edging is less extensive, especially on the rear section of the pronotum. There is often a pale whitish or fawn median line along the head and the dorsal surface of the pronotum. The sides and front of the head and the paranota may be of the same green as the dorsal surfaces, or may be greyish or fawn-brown, sometimes with darker mottling. The ground colour of the abdomen may be greyish or very pale green, with black lateral markings on the first four or five segments. The fore wings often have a white stripe close to the leading edge, and a faintly marked white stigma.

FIGS E–F. Green female with brown side; brown male.

There is also a rare form with purple coloration on the sides of the head, on the paranota, and sometimes on the legs and the basal areas of the fore wings.

Similar species

Life cycle

The egg pods are deposited during the summer at the bases of tufts of grass. They are broadly elliptical and contain up to ten eggs. These hatch the following spring, in April or early May in most years, and the resulting nymphs pass through four instars, emerging as adults from the end of May onwards. In the south the stridulation of the male can usually be heard from the first week in June onwards (as early as 19 May in the exceptionally warm spring of 2011 (pers. obs.)), later in the north and at higher altitudes. They are at their most abundant from mid-June through to early September, adults becoming scarcer into early October.

Habitat

This species is said to favour moist, grassy sites, including ditch banks, stream valleys, and damp meadows. Its habitats include parkland, open areas and ride edges in woodland, and, at higher altitudes, unimproved pastures and moorland up to 1,000 metres in Britain. It is regarded as an indicator species of unimproved pasture (Marshall & Haes, 1988). It prefers relatively tall, cool and moist grasslands, frequently with purple moor grass (Molinea caerulea) or Yorkshire fog (Holcus lanatus). It is regarded as physiologically adapted to cooler climates as it is relatively effective in raising its temperature above the ambient, and poor at cooling when ambient temperatures are high (Willott, 1997).