THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE IN THE FOURTEENTH CENTURY

§ 1. GENERAL. Gower’s work shows that at the end of the century Latin and French still shared with English the place of a literary language. But their hold was precarious.

Latin was steadily losing ground. The Wiclifite translation of the Bible threatened its hitherto unchallenged position as the language of the Church; and the Renaissance had not yet come to give it a new life among secular scholars.

French was still spoken at the court; but in 1387 Trevisa remarks (p. 149) that it was no longer considered an essential part of a gentleman’s education: and he records a significant reform—the replacement of French by English as the medium of teaching in schools. After the end of the century Anglo- French, the native development of Norman, was practically confined to legal use, and French of Paris was the accepted standard French.

English gained wherever Latin and French lost ground. But though the work of Chaucer, Gower, and Wiclif foreshadows the coming supremacy of the East Midland, or, more particularly, the London dialect, there was as yet no recognized standard of literary English. The spoken language showed a multiplicity of local varieties, and a writer adopted the particular variety that was most familiar to him. Hence it is almost true to say that every considerable text requires a special grammar.

Confusion is increased by the scribes. Nowadays a book is issued in hundreds or thousands of uniform copies, and within a few months of publication it may be read in any part of the world. In the fourteenth century a book was made known to readers only by the slow and costly multiplication of manuscripts. The copyist might work long after the date of composition, and he would then be likely to modernize the language, which in its written form was not stable as it is at present: so of Barbour’s Bruce the oldest extant copies were made nearly a century after Barbour’s death. Again, if the dialect of the author were unfamiliar to the copyist, he might substitute familiar words and forms. Defective rimes often bear witness to these substitutions.

Nor have we to reckon only with copyists, who, are as a rule careless rather than bold innovators. While books were scarce and many could not read them, professional minstrels and amateur reciters played a great part in the transmission of popular literature; and they, whether from defective memory or from belief in their own talents, treated the exact form and words of their author with scant respect. An extreme instance is given by the MSS. of Sir Orfeo at ll. 267–8:

Auchinleck MS.: His harp, whereon was al his gle,

He hidde in an holwe tre;

Harley MS.: He takeþ his harpe and makeþ hym gle,

And lyþe al ny![]() t vnder a tre;

t vnder a tre;

Ashmole MS.: In a tre þat was holow

Þer was hys haule euyn and morow.

If the Ashmole MS. alone had survived we should have no hint of the degree of corruption.

And so, before the extant MSS. recorded the text, copyists and reciters may have added change to change, jumbling the speech of different men, generations, and places, and producing those ‘mixed’ texts which are the will-o’-the-wisps of language study.

Faced with these perplexities, beginners might well echo the words of Langland’s pilgrims in search of Truth:

This were a wikked way, hut whoso hadde a gyde

That wolde folwen vs eche a fote.

There is no such complete guide, for the first part of Morsbach’s Mittelenglische Grammatik, Halle 1896, remains a splendid fragment, and Luick’s Historische Grammatik der englischen Sprache, Leipzig 1914– , which promises a full account of the early periods, is still far from completion. Happily two distinguished scholars—Dr. Henry Bradley in The Making of English and his chapter in The Cambridge History of English Literature, vol. i, Dr. O. Jespersen in Growth and Structure of the English Language—have given brief surveys of the whole early period which are at once elementary and authoritative. But for the details the student must rely on a mass of dissertations and articles of very unequal quality, supplemented by introductions to single texts, and, above all, by his own first-hand observations made on the texts themselves.

Some preliminary considerations will be helpful, though perhaps not altogether reassuring:

(i) A great part of the evidence necessary to a thorough knowledge of spoken Middle English has not come down to us, a considerable part remains unprinted, and the printed materials are so extensive and scattered that it is easy to overlook points of detail. For instance, it might be assumed from rimes in Gawayne, Pearl, and the Shropshire poet Myrc, that the falling together of OE. -ang-, -ung-, which is witnessed in NE. among (OE. gemang) -monger (OE. mangere), was specifically West Midland, if the occurrence of examples in Yorkshire (XVII 397–400) escaped notice. It follows that, unless a word or form is so common as to make the risk of error negligible, positive evidence—the certainty that it occurs in a given period or district—is immeasurably more important than negative evidence—the belief that it never did occur, or even the certainty that it is not recorded, in a period or district. For the same reason, the statement that a word or form is found ‘in the early fourteenth century’ or ‘in Kent’ should always be understood positively, and should not be taken to imply that it is unknown ‘in the thirteenth century’ or ‘in Essex’, as to which evidence may or may not exist.

(ii) It is necessary to clear the mind of the impression, derived from stereotyped written languages, that homogeneity and stability are natural states. Middle English texts represent a spoken language of many local varieties, all developing rapidly. So every linguistic fact should be thought of in terms of time, place, and circumstance, not because absolute precision in these points is attainable, but because the attempt to attain it helps to distinguish accurate knowledge from conclusions which are not free from doubt.

If the word or form under investigation can be proved to belong to the author’s original composition, exactness is often possible. In the present book, we know nearly enough the date of composition of extracts I, III, VIII, X, XI a, XII, XIII, XIV; the place of composition of I, III, X, XI a, XII, XIII, XVI, XVII (see map).

But if, as commonly happens, a form cannot be proved to have stood in the original, endless difficulties arise. It will be necessary first to determine the date of the MS. copy. This is exactly known for The Bruce, and there are few Middle English MSS. which the palaeographer cannot date absolutely within a half-century, and probably within a generation. The place where the MS. copy was written is known nearly enough for IV b, c, XII, XIV e, XV b, c (possibly Leominster), XVI, XVII; and ME. studies have still much to gain from a thorough inquiry into the provenance of MSS. Yet, when the extant copy is placed and dated, it remains to ask to what extent this MS. reproduces some lost intermediary of different date and provenance; how many such intermediaries there were between the author’s original and our MS.; what each has contributed to the form of the surviving copy—questions usually unanswerable, the consideration of which will show the exceptional linguistic value of the Ayenbyte, where we have the author’s own transcript exactly dated and localized, so that every word and form is good evidence.

Failing such ideal conditions, it becomes necessary to limit doubt by segregating for special investigation the elements that belong to the original composition. Hence the importance of rimes, alliteration, and rhythm, which a copyist or reciter is least likely to alter without leaving a trace of his activities.

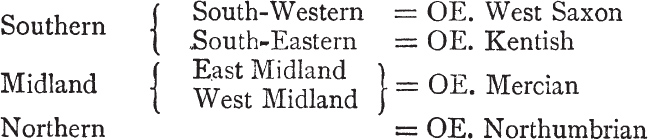

§ 2. DIALECTS. At present any marked variation from the practice of educated English speakers might, if it were common to a considerable number of persons, be described as dialectal. But as there was no such recognized standard in the fourteenth century, it is most convenient to consider as dialectal any linguistic feature which had a currency in some English-speaking districts but not in all. For example, þat as a relative is found everywhere in the fourteenth century and is not dialectal; þire ‘these’ is recorded only in Northern districts, and so is dialectal. Again, ![]() represents OE. ā in the South and Midlands, while the North retains ā (§ 7 b i): since neither

represents OE. ā in the South and Midlands, while the North retains ā (§ 7 b i): since neither ![]() nor ā is general, both may be called dialectal.

nor ā is general, both may be called dialectal.

If a few sporadic developments be excluded because they may turn up anywhere at any time, then, provided sufficient evidence were available,1 it would be possible to mark the boundaries within which any given dialectal feature occurs at a particular period: we could draw the line south of which þire ‘these’ is not found, or the line bounding the district in which the Norse borrowing kirke occurs; just as French investigators in L’Atlas linguistique de la France have shown the distribution of single words and forms in the modern French dialects.

Of more general importance is the fixing of boundaries for sound changes or inflexions that affect a large number of words, a task to which interesting contributions have been made in recent years on the evidence of place-names (see especially A. Brandl, Zur Geographie der altenglischen Dialekte, Berlin 1915, which supplements the work of Pogatscher on the compounds of street and of Wyld on the ME. developments of OE. y). For example, on the evidence available, which does not permit of more than rough indications, OE. ā remains ā, and does not develop to ![]() , north of a line drawn west from the Humber (§ 7 b i); -and(e) occurs in the ending of the pres. p. as far south as a line starting west from the Wash (§13 ii); farther south again, a line between Norwich and Birmingham gives the northern limit for Stratton forms as against Stretton (§ 8 iv, note).2 The direction of all these lines is roughly east and west, yet no two coincide. But if the developments of OE. y (§ 7 b ii) are mapped out, u appears below a line drawn athwart from Liverpool to London, and normal e east of a line drawn north and south from the western border of Kent. Almost every important feature has thus its own limits, and the limits of one may cross the limits of another.

, north of a line drawn west from the Humber (§ 7 b i); -and(e) occurs in the ending of the pres. p. as far south as a line starting west from the Wash (§13 ii); farther south again, a line between Norwich and Birmingham gives the northern limit for Stratton forms as against Stretton (§ 8 iv, note).2 The direction of all these lines is roughly east and west, yet no two coincide. But if the developments of OE. y (§ 7 b ii) are mapped out, u appears below a line drawn athwart from Liverpool to London, and normal e east of a line drawn north and south from the western border of Kent. Almost every important feature has thus its own limits, and the limits of one may cross the limits of another.

What then is a ME. dialect ? The accepted classification is

with the Thames as boundary between Southern and Midland, and the Humber between Midland and Northern. And yet of five actual limiting lines taken at random, only the first coincides approximately with the line of Humber or Thames.

Still the classification rests on a practical truth. Although each dialectal feature has its own boundaries, these are not set by pure chance. Their position is to some extent governed by old tribal and political divisions, by the influence of large towns which served as commercial and administrative centres, and by relative ease of communication. Consequently, linguistic features are roughly grouped, and it is a priori likely that London and Oxford would have more features in common than would London and York, or Oxford and Hull; and similarly it is likely that for a majority of phenomena York and Hull would stand together against London and Oxford. Such a grouping was recognized in the fourteenth century. Higden and his authorities distinguish Northern and Southern speech (XIII b); in the Towneley Second Shepherds’ Play, ll. 201 ff., when Mak pretends to be a yeoman of the king, he adopts the appropriate accent, and is promptly told to ‘take outt that Sothren tothe’. In the Reeves Tale Chaucer makes the clerks speak their own Northern dialect, so we may be sure that he thought of it as a unity.

But had Chaucer been asked exactly where this dialect was spoken, he would probably have replied, Fer in the North,—I kan nat telle where. A dialect has really no precise boundaries; its borders are nebulous; and throughout this book ‘Southern’, ‘Northern’, &c., are used vaguely, and not with any sharply defined limits in mind. The terms may, however, be applied to precise areas, so long as the boundaries of single dialect features are not violently made to conform. It is quite accurate to say that -and(e) is the normal ending of the pres. p. north of the Humber, and that u for OE. y is found south of the Thames and west of London, provided it is not implied that the one should not be found south of the Humber, or the other north of the Thames. Both in fact occur in Gawayne (Cheshire or Lancashire); and in general the language of the Midlands was characterized by the overlapping of features which distinguish the North from the South.

From what has been said it should be plain that the localization of a piece of Middle English on the evidence of language alone calls for an investigation of scope and delicacy. Where the facts are so complex the mechanical application of rules of thumb may give quick and specious results, but must in the end deaden the spirit of inquiry, which is the best gift a student can bring to the subject.

§ 3. VOCABULARY. The readiness of English speakers to adopt words from foreign languages becomes marked in fourteenth-century writings. But the classical element which is so pronounced in modern literary English is still unimportant. There are few direct borrowings from Latin, and these, like obitte XVI 269, are for the most part taken from the technical language of the Church. The chief sources of foreign words are Norse and French.

(a) Norse. Although many Norse words first appear in English in late texts, they must have come into the spoken language before the end of the eleventh century, because the Scandinavian settlements ceased after the Norman Conquest. The invaders spoke a dialect near enough to OE. to be intelligible to the Angles ; and they had little to teach of literature or civilization. Hence the borrowings from Norse are all popular; they appear chiefly in the Midlands and North, where the invaders settled; and they witness the intimate fusion of two kindred languages. From Norse we get such common words as anger, both, call, egg, hit, husband, ill, law, loose, low, meek, take, till (prep.), want, weak, wing, wrong, and even the plural forms of the 3rd personal pronoun (§ 12).

It is not always easy to distinguish Norse from native words, because the two languages were so similar during the period of borrovving, and Norse words were adopted early enough to be affected by all ME. sound changes. But there were some dialectal differences between ON. and OE. in the ninth and tenth centuries, and these afford the best criteria of borrowing. For instance in ME. we have þou![]() , þof(ON. þ

, þof(ON. þ![]() h for *þauh) beside þei(h) (OE. þē(a)h) II 433; ay (ON. ei) ‘ever’ XVI 293 beside oo (OE. ā) XV b 7; waik (ON. veik-r) VIII b 23, where OE. wāc would yield w

h for *þauh) beside þei(h) (OE. þē(a)h) II 433; ay (ON. ei) ‘ever’ XVI 293 beside oo (OE. ā) XV b 7; waik (ON. veik-r) VIII b 23, where OE. wāc would yield w![]() k the forms w

k the forms w![]() re XVI 17 (note) and wāpin XIV b 15 are from ON. várum, vápn, whereas were(n) and wĕppen V 154 represent OE. (Anglian) wēron, wēpn. So we have the pairs awe (ON. agi) I 83 and ay (OE. ege) II 571; neuen (ON. nefna) ‘to name’ XVII 12 and nem(p)ne (OE. nemnan) II 600: rot (ON. rót) II 256 and wort (OE. wyrt) VIII a 303; sterne, starne (ON. stjarna) XVII 8, 423 and native sterre, starre (OE. steorra); systyr (ON. systir) I 112 and soster (OE. sweostor) XV g 10; werre, warre (ON. verri) XVI 154 (note), 334 and native werse, wars, (OE. wyrsa) XVI 200, XVII 191; wylle (ON. vill-r) V 16 and native wylde (OE. wilde) XV b 19.

re XVI 17 (note) and wāpin XIV b 15 are from ON. várum, vápn, whereas were(n) and wĕppen V 154 represent OE. (Anglian) wēron, wēpn. So we have the pairs awe (ON. agi) I 83 and ay (OE. ege) II 571; neuen (ON. nefna) ‘to name’ XVII 12 and nem(p)ne (OE. nemnan) II 600: rot (ON. rót) II 256 and wort (OE. wyrt) VIII a 303; sterne, starne (ON. stjarna) XVII 8, 423 and native sterre, starre (OE. steorra); systyr (ON. systir) I 112 and soster (OE. sweostor) XV g 10; werre, warre (ON. verri) XVI 154 (note), 334 and native werse, wars, (OE. wyrsa) XVI 200, XVII 191; wylle (ON. vill-r) V 16 and native wylde (OE. wilde) XV b 19.

Note that in Norse borrowings the consonants g, k remain stops where they are palatalized in English words: garn XVII 298, giue, gete (ON. garn, gefa, geta) beside ![]() arn,

arn, ![]() iue, for-

iue, for-![]() ete (OE. gearn, giefan, for-gietan); kirke (ON. kirkja) beside chirche (OE. cirice). Similarly OE. initial sc- regularly becomes ME. sh-, so that most words beginning with sk-, like sky, skin, skyfte VI 209 (English shift), skirte (English shirt), are Norse; see the alliterating words in V 99.

ete (OE. gearn, giefan, for-gietan); kirke (ON. kirkja) beside chirche (OE. cirice). Similarly OE. initial sc- regularly becomes ME. sh-, so that most words beginning with sk-, like sky, skin, skyfte VI 209 (English shift), skirte (English shirt), are Norse; see the alliterating words in V 99.

There is an excellent monograph by E. Björkman: Scandinavian Loan-Words in Middle English, 1900.

(b) French. Most early borrowings from French were again due to invasion and settlement. But the conditions of contact were very different. Some were unfavourable to borrowing: the Normans, who were relatively few, were dispersed throughout the country, and not, like the Scandinavians, massed in colonies; and their language had little in common with English. So the number of French words in English texts is small before the late thirteenth and the fourteenth centuries. Other conditions made borrowing inevitable: the French speakers were the governing class; they gradually introduced a new system of administration and new standards of culture ; and they had an important literature to which English writers turned for their subject-matter and their models of form. Fourteenth-century translators adopt words from their French originals so freely (see note at p. 234, foot), that written Middle English must give a rather exaggerated impression of the extent of French influence on the spoken language. But a few examples will show how many common words are early borrowings from French: nouns like country, face, place, river, courtesy, honour, joy, justice, mercy, pity, reason, religion, war; adjectives like close, large, poor: and verbs cry, pay, please, save, serve, use.

Anglo-French was never completely homogeneous, and it was constantly supplemented as a result of direct political, commercial, and literary relations with France. Hence words were sometimes adopted into ME. in more than one French dialectal form. For instance, Late Latin ca- became cha- in most French dialects, but remained ca- in the North of France: hence ME. catch and (pur)chase, catel and chatel, kanel ‘neck’ V 230 and chanel ‘channel’ XIII a 57. So Northern French preserves initial w-, for which other French dialects substitute g(u): hence Wowayn V 121 beside Gawayn V 4, &c. (see note to V 121). Again, in Anglo-French, a before nasal + consonant alternates with au:—dance: daunce; chance: chaunce; change: chaunge; chambre XVII 281 :chaumber II 100. English still has the verbs launch and lance, which are ultimately identical.

As borrowing extended over several centuries, the ME. form sometimes depends on the date of adoption. Thus Latin fidem becomes early French feið, later fei, and later still foi. ME. has both feiþ and fay, and by Spenser’s time foy appears.

The best study of the French element in ME. is still that of D. Behrens: Beiträge zur Geschichte der französischen Sprache in England, 1886. A valuable supplement, dealing chiefly with Anglo-French as the language of the law, is the chapter by F. W. Maitland in The Cambridge History of English Literature, vol. i.

§ 4. HANDWRITING. In the ME. period two varieties of script were in use, both developed from the Caroline minuscule which has proved to be the most permanent contribution of the schools of Charlemagne. The one, cursive and flourished, is common in charters, records, and memoranda; see C. H. Jenkinson and C. Johnson, Court Hand, 2 vols., Oxford 1915. The other, in which the letters are separately written, with few flourishes or adaptations of form in combination, is the ‘book hand’, so called because it is regularly used for literary texts. Between the extreme types there are many gradations ; and fifteenth-century copies, such as the Cambridge MS. of Barbour’s Bruce, show an increasing use of cursive forms, which facilitate rapid writing.

The shapes of letters were not always so distinct as they are in print, so that copyists of the time, and even modern editors, are liable to mistake one letter for another. Each hand has its own weaknesses, but the letters most commonly misread are: —

e: o e. g. Beuo for Bouo I 59; wroche for wreche II 333; teches IV b 60, where toches (foot-note) is probably right; pesible (MS. posible) XI b 67.

u: n (practically indistinguishable) e. g. menys (MS. mouys) XVI 301; skayned (edd. skayued) V 99; ryue![]() , or ryne

, or ryne![]() V 222 (note). This is only a special case of the confusion of letters and combinations formed by repetition of the downstroke, e. g. u, n, m, and i (which is not always distinguished by a stroke above). Hence dim II 285 where modern editors have dun, although i has the distinguishing stroke.

V 222 (note). This is only a special case of the confusion of letters and combinations formed by repetition of the downstroke, e. g. u, n, m, and i (which is not always distinguished by a stroke above). Hence dim II 285 where modern editors have dun, although i has the distinguishing stroke.

y : þ e.g. ye (MS. þe) XIV d 11; see note to XV a 12. Confusion is increased by occasional transference to þ of the dot which historically may stand over y. ![]() for þ initially, as in XVI 170, is more often due to confusion of the letters þ : y and subsequent preference of

for þ initially, as in XVI 170, is more often due to confusion of the letters þ : y and subsequent preference of ![]() for y in spelling (§ 5 i) than to direct confusion of þ :

for y in spelling (§ 5 i) than to direct confusion of þ : ![]() , which are not usually very similar in late Middle English script.

, which are not usually very similar in late Middle English script.

b: h e. g. doþ (MS. doh) XV b 22; and notes to XII b 116, XVI 62.

b : v e. g. vousour (edd. bonsour) II 363.

c : t e.g. cunesmen (edd. tunesmen) XV g 6 (note); top (edd. cop) ibid. 16; see note to XIII a 7.

![]() e. g. slang (variant flang) X 53.

e. g. slang (variant flang) X 53.

![]() e.g. al (edd. as) II 108.

e.g. al (edd. as) II 108.

l : k e.g. kyþe![]() (MS. lyþe

(MS. lyþe![]() ) VI 9.

) VI 9.

§ 5. SPECIAL LETTERS. Two letters now obsolete are common in fourteenth-century MSS.: þ and ![]() .

.

þ: ‘thorn’, is a rune, and stands for the voiced and voiceless sounds now represented by th in this, thin. The gradual displacement of þ by th which had quite a different sound in classical Latin (note to VIII a 23), may be traced in the MSS. printed (except X, XII). þ remained longest in the initial position, but by the end of the fifteenth century was used chiefly in compendia like þe ‘the’, þt ‘that’.

![]() : called ‘

: called ‘![]() o

o![]() ’ or ‘yogh’, derives from

’ or ‘yogh’, derives from ![]() , the OE. script form of the letter g. It was retained in ME. after the Caroline form g had become established in vernacular texts, to represent a group of spirant sounds:

, the OE. script form of the letter g. It was retained in ME. after the Caroline form g had become established in vernacular texts, to represent a group of spirant sounds:

(i) The initial spirant in ![]() oked IX 253 (OE. geoc-)

oked IX 253 (OE. geoc-) ![]() ere I 151 (OE. gēar), where the sound was approximately the same as in our yoke, year. Except in texts specially influenced by the tradition of French spelling, y (which is ambiguous owing to its common use as a vowel = i) is less frequent than

ere I 151 (OE. gēar), where the sound was approximately the same as in our yoke, year. Except in texts specially influenced by the tradition of French spelling, y (which is ambiguous owing to its common use as a vowel = i) is less frequent than ![]() initially. Medially the palatal spirant is represented either by

initially. Medially the palatal spirant is represented either by ![]() or y: e

or y: e![]() e (OE. ē(a)

e (OE. ē(a)![]() -) XV c 14 beside eyen VIII a 168; ise

-) XV c 14 beside eyen VIII a 168; ise![]() e (OE. gesegen) XIV c 88 beside iseye XIV c 16. The medial guttural spirant more commonly develops to w in the fourteenth century: awe (ON. agi) I 83, felawe (ON. félagi) XIV d 7, halwes (OE. halg-) beside a

e (OE. gesegen) XIV c 88 beside iseye XIV c 16. The medial guttural spirant more commonly develops to w in the fourteenth century: awe (ON. agi) I 83, felawe (ON. félagi) XIV d 7, halwes (OE. halg-) beside a![]() - V 267, fela

- V 267, fela![]() -, V 83, hal

-, V 83, hal![]() - V 54.

- V 54.

(ii) The medial or final spirant, guttural or palatal, which is lost in standard English, but still spelt in nought, through, night, high: ME. no![]() t, þur

t, þur![]() , ny

, ny![]() t, hy

t, hy![]() : OE. noht, þurh, niht, hēh. The ME. sound was probably like that in German ich, ach. The older spelling with h is occasionally found; more often ch as in mycht X 17; but the French spelling gh gains ground throughout the century. Abnormal are write for wrighte XVI 230, wytes, nytes for wy

: OE. noht, þurh, niht, hēh. The ME. sound was probably like that in German ich, ach. The older spelling with h is occasionally found; more often ch as in mycht X 17; but the French spelling gh gains ground throughout the century. Abnormal are write for wrighte XVI 230, wytes, nytes for wy![]() tes, ny

tes, ny![]() tes XV i 19 f.

tes XV i 19 f.

(iii) As these sounds weakened in late Southern ME., ![]() was sometimes used without phonetic value, or at the most to reinforce a long i: e.g. Engli

was sometimes used without phonetic value, or at the most to reinforce a long i: e.g. Engli![]() sch XI a 28, 37, &c.; ky

sch XI a 28, 37, &c.; ky![]() n ‘kine’ IX 256.

n ‘kine’ IX 256.

N.B.—Entirely distinct in origin and sound value, but identical in script form, is ![]() , the minuscule form of z, in A

, the minuscule form of z, in A![]() one (= Azone) I 105, clyffe

one (= Azone) I 105, clyffe![]() ‘cliffs’ V 10, &c, It would probably be better to print z in such words.

‘cliffs’ V 10, &c, It would probably be better to print z in such words.

§ 6. SPELLING. Modern English spelling, which tolerates almost any inconsistency in the representation of sounds provided the same word is always spelt in the approved way, is the creation of printers, schools, and dictionaries. A Middle English writer was bound by no such arbitrary rules. Michael of Northgate, whose autograph MS. survives, writes diaknen III 5 and dyacne 9; uyf 22, uif 23, vif 37; bouzond 30 and þousend 34. Yet his spelling is not irrational. The comparative regularity of his own speech, which he reproduced directly, had a normalizing influence; and by natural habit he more often than not solved the same problem of representation in the same way. Scribes, too, like printers in later times, found a measure of consistency convenient, and the spelling of some transcripts, e.g. I and X, is very regular. If at first ME. spelling appears lawless to a modern reader, it is because of the variety of dialects represented in literature, the widely differing dates of the MSS. printed, and the tendency of copyists to mix their own spellings with those of their original.

The following points must be kept in mind:

(i) i : y as vowels are interchangeable. In some MSS. (for instance, I) y is used almost exclusively; in others (VIII a) it is preferred for distinctness in the neighbourhood of u, n, m, so that the scribe writes hym, but his.

(ii) ie is found in later texts for long close ![]() : chiere XII a 120, flietende XII a 157, diemed XII b 216.

: chiere XII a 120, flietende XII a 157, diemed XII b 216.

(iii) ui (uy), in the South-West and West Midlands, stands for ![]() (sounded as in French amuser): puit XIV c 12; unkuynde XIV c 103. The corresponding short ü is spelt u: hull ‘hill’, &c.

(sounded as in French amuser): puit XIV c 12; unkuynde XIV c 103. The corresponding short ü is spelt u: hull ‘hill’, &c.

(iv) Quite distinct is the late Northern addition of i (y), to indicate the long vowels ā, ē, ō: neid X 18, noyne ‘noon’ X 67.

(v) ou (ow) is the regular spelling of long ū (sounded as in too): hous, now, founden, &c.

(vi) o is the regular spelling for short u (sounded as in put) in the neighbourhood of u, m, n, because if u is written in combination with these letters an indistinct series of down-strokes results. Hence loue but luf, come infin., sone ‘son’, dronken ‘drunk’. In Ayenbyte o for ŭ is general, e.g. grochinge III 10. In other texts it is common in bote ‘but’.

(vii) u : v are not distinguished as consonant and vowel. v is preferred in initial position, u medially or finally: valay ‘valley’, under ‘under’, vuel(= üvel) ‘evil’, loue ‘love’. (Note that in XII the MS. distinction of v and u is not reproduced.)

(viii) So i, and its longer form j, are not distinguished as vowel and consonant. In this book i is printed throughout, and so stands initially for the sound of our j in ioy, iuggement, &c.

(ix) c : k for the sounds in kit, cot, are often interchangeable; but k is preferred before palatal vowels e, i (y); and c before o, u. See the alliterating words in V 52, 107, 128, 153, 272, 283.

(x) c : s alternate for voiceless s, especially in French words: sité ‘city’ VII 66, resayue ‘receive’ V 8, uyse ‘vice’ V 307, falce V 314; but also in race (ON. rás) V 8 beside rase XVII 429.

(xi) s : z (![]() ) are both used for voiced s, the former predominating: kyssedes beside ra

) are both used for voiced s, the former predominating: kyssedes beside ra![]() te

te![]() V 283; þouzond III 30 beside bousend III 34. But

V 283; þouzond III 30 beside bousend III 34. But ![]() occasionally appears for voiceless s : (a

occasionally appears for voiceless s : (a![]() -)le

-)le![]() ‘awe-less’ V 267, for

‘awe-less’ V 267, for![]() ‘force’ ‘waterfall’ V 105.

‘force’ ‘waterfall’ V 105.

(xii) sh : sch : ss are all found for modern sh, OE. sc: shuld I 50; schert II 230; sserte III 40; but sal ‘shall’, suld ‘should’ in Northern texts represent the actual Northern pronunciation in weakly stressed words.

(xiii) v: w: In late Northern MSS. v is often found for initial w: vithall X 9, Valter X 36. The interchange is less common in medial positions: in swndir X 106.

(xiv) wh-: qu(h)-: w-:—wh- is a spelling for hw-. In the South the aspiration is weakened or lost, and w is commonly written, e. g. VIII b. In the North the aspiration is strong, and the sound is spelt qu(h)-, e. g. quhelis ‘wheels’ X 17. Both qu-, and wh- are found in Gawayne. The development in later dialects is against the assumption that hw- became kw- in pronunciation.

See also § 5.

The whole system of ME. spelling was modelled on French, and some of the general features noted above (e.g. ii, iii, v, vi, x) are essentially French. But, particularly in early MSS., there are a number of exceptional imitations. Sometimes the spelling represents a French scribe’s attempt at English pronunciation: foret in XV g 18 stands for forþ, where -rþ with strongly trilled r was difficult to a foreigner; and occasionally such distortions are found as knith, knit, and even kint (Layamon, Havelok) for kni![]() t, which had two awkward consonant groups. More commonly the copyist, accustomed to write both French and English, chose a French representation for an English sound. So st for ht appears regularly in XV e: seuenist ‘sennight’, and XV g: iboust ‘bought’, &c. The explanation is that in French words like beste ‘bête’, gist ‘gît’, s became only a breathing before it disappeared; and h in ME. ht weakened to a similar sound, as is shown by the rimes with Kryste ‘Christ’ in VI 98–107. Hence the French spelling st is occasionally substituted for English ht. Again, in borrowings from French, an + consonant alternates with aun: dance or daunce: change or chaunge (p. 273); and by analogy we have Irlande or Irlaunde in XV d. Another exceptional French usage, -tz for final voiceless -s, is explained at p. 219, top.

t, which had two awkward consonant groups. More commonly the copyist, accustomed to write both French and English, chose a French representation for an English sound. So st for ht appears regularly in XV e: seuenist ‘sennight’, and XV g: iboust ‘bought’, &c. The explanation is that in French words like beste ‘bête’, gist ‘gît’, s became only a breathing before it disappeared; and h in ME. ht weakened to a similar sound, as is shown by the rimes with Kryste ‘Christ’ in VI 98–107. Hence the French spelling st is occasionally substituted for English ht. Again, in borrowings from French, an + consonant alternates with aun: dance or daunce: change or chaunge (p. 273); and by analogy we have Irlande or Irlaunde in XV d. Another exceptional French usage, -tz for final voiceless -s, is explained at p. 219, top.

§ 7. SOUND CHANGES, (a) Vowel Quantity. No fourteenth-century writer followed the early example of Orm. Marks of quantity are not used in fourteenth-century texts; doubling of long vowels is not an established rule; and there are no strictly quantitative metres, or treatises on pronunciation. Consequently it is not easy to determine how far the quantity of the vowels in any given text has been affected by the very considerable changes that occurred in the late OE. and ME. periods.

Of these the chief are:

(i) In unstressed syllables original long vowels tend to become short. Hence ŭs (OE. ūs), and bŏte (OE. būtan) ‘but’, which are usually unstressed.

(ii) All long vowels are shortened in stressed close syllables (i.e., usually, when they are followed by two consonants): e.g. kēpen, pa. t. Kĕpte, pp. kĕpt; hŭsband beside hous; wīmmen (from wīf-men) beside wīf.

Exception. Before the groups -ld, -nd, -rd, -rð, -mb, a short vowel is lengthened in OE. unless, a third consonant immediately follows. Hence, before any of these combinations, length may be retained in ME.: e.g. fēnd ‘fiend’, bīnden, chīld; but chīldren.

(iii) Short vowels ă, ĕ, ŏ are lengthened in stressed open syllables (i.e., usually, when they are followed by a single consonant with a following vowel): tă|ke > táke; mĕ|te > méte ‘meat’; brŏ|ken > bróken. To what extent ī and ŭ were subject to the same lengthening in Northern districts is still disputed. Normally they remain short in South and S. Midlands, e.g. drīuen pp.; lŏuen = lŭven ‘to love’.

There are many minor rules and many exceptions due to analogy; but roughly it may be taken that ME. vowels are:

short when unstressed;

short before two consonants, except -ld, -nd, -rd, -rð, -mb;

long (except i(y), u) before a single medial consonant;

otherwise of the quantity shown in the Glossary for the OE. or ON. etymon.

(b) Vowel Quality. The ME. sound-changes are so many and so obscure that it will be possible to deal only with a few that contribute most to the diversity of dialects, and it happens that the particular changes noticed all took effect before the fourteenth century.

(i) OE. and ON. ā develop to long open ![]() (sounded as in broad), first in the South and S. Midlands, later in the N. Midlands. In the North ā (sounded approximately as in father) remains: e.g. bane ‘bone’ IV a 54, balde ‘bold’ IV a 51. The boundary seems to have been a line drawn west from the Humber, and this approximates to the dividing line in the modern dialects. There are of course instances of

(sounded as in broad), first in the South and S. Midlands, later in the N. Midlands. In the North ā (sounded approximately as in father) remains: e.g. bane ‘bone’ IV a 54, balde ‘bold’ IV a 51. The boundary seems to have been a line drawn west from the Humber, and this approximates to the dividing line in the modern dialects. There are of course instances of ![]() to the north and of ā to the south of the Humber, since border speakers would be familiar with both ā and

to the north and of ā to the south of the Humber, since border speakers would be familiar with both ā and ![]() , or would have intermediate pronunciations; and poets might use convenient rimes from neighbouring dialects.

, or would have intermediate pronunciations; and poets might use convenient rimes from neighbouring dialects.

(ii) OE. ![]() (deriving from Germanic

(deriving from Germanic ![]() followed by i) appears normally in E. Midlands and the North as

followed by i) appears normally in E. Midlands and the North as ![]() : e.g. kȳn, hill (OE. cȳ, hyll). In the South-East, particularly Kent, it appears as

: e.g. kȳn, hill (OE. cȳ, hyll). In the South-East, particularly Kent, it appears as ![]() : kēn, hell. In the South-West, and in W. Midlands, it commonly appears as u, ui (uy), with the sound of short or long ü. London was apparently at a meeting point of the u, i, and e boundaries, because all the forms appear in fourteenth-century London texts, though

: kēn, hell. In the South-West, and in W. Midlands, it commonly appears as u, ui (uy), with the sound of short or long ü. London was apparently at a meeting point of the u, i, and e boundaries, because all the forms appear in fourteenth-century London texts, though ![]() and

and ![]() gradually give place to

gradually give place to ![]() . The extension of

. The extension of ![]() forms to the North-West is shown by Gawayne, and a line drawn from London to Liverpool would give a rough idea of the boundary. But within this area unrounding of

forms to the North-West is shown by Gawayne, and a line drawn from London to Liverpool would give a rough idea of the boundary. But within this area unrounding of ![]() to

to ![]() seems to have been progressive during the century. N.B.—It is dangerous to jump to conclusions from isolated examples. Before r + consonant e is sometimes found in all dialects, e.g. schert II 230. Church spelt with u, i, or e, had by etymology OE. i, not y. And in Northern texts there are a number of e-spellings in open syllables, both for OE. y and i.

seems to have been progressive during the century. N.B.—It is dangerous to jump to conclusions from isolated examples. Before r + consonant e is sometimes found in all dialects, e.g. schert II 230. Church spelt with u, i, or e, had by etymology OE. i, not y. And in Northern texts there are a number of e-spellings in open syllables, both for OE. y and i.

(c) Consonants:

(i) f > v (initial): this change, which dates back to OE. times, is carried through in Ayenbyte: e.g. uele uayre uorbisnen = Midland ‘fele fayre forbisnes’. In some degree it extended over the whole of the South.

(ii)s > z (initial), parallel to the change of f to v, is regularly represented in spelling in the Ayenbyte: zome ‘some’, &c. Otherwise z is rare in spelling, but the voiced initial sound probably extended to most of the Southern districts where it survives in modern dialect.

§ 8. PRONUNCIATION. One of the best ways of studying ME. pronunciation is to learn by heart a few lines of verse in a consistent dialect, and to correct their repetition as more precise knowledge is gained. The spelling can be relied on as very roughly phonetic if the exceptional usages noted in §6 are kept in mind. Supplementary and controlling information is provided by the study of rimes, of alliteration, and of the history of English and French sounds.

Consonants. Where a consonant is clearly pronounced in Modern English, its value is nearly enough the same for ME. But modern spelling preserves many consonants that have been lost in speech, and so is rather a hindrance than a help to the beginner in ME. For instance, the initial sounds in ME. kni![]() t and ni

t and ni![]() t were not the same, for kni

t were not the same, for kni![]() t alliterates always with k- (V 43, 107) and ni

t alliterates always with k- (V 43, 107) and ni![]() t with n- (VII 149); and initial wr- in wringe, wri

t with n- (VII 149); and initial wr- in wringe, wri![]() te is distinct from initial r- in ring, ri

te is distinct from initial r- in ring, ri![]() t (cp. alliteration in VIII a 168, V 136). Nor can wri

t (cp. alliteration in VIII a 168, V 136). Nor can wri![]() te rime with write in a careful fourteenth-century poem. In words like lerne, doghter, r was pronounced with some degree of trilling. And although there are signs of confusion in late MSS. (IV a, XVI, XVII), double consonants were generally distinguished from single: sonne ‘sun’ was pronounced sŭn-ne, and so differed from sone ‘son’, which was pronounced sŭ-ne (§ 6 vi).

te rime with write in a careful fourteenth-century poem. In words like lerne, doghter, r was pronounced with some degree of trilling. And although there are signs of confusion in late MSS. (IV a, XVI, XVII), double consonants were generally distinguished from single: sonne ‘sun’ was pronounced sŭn-ne, and so differed from sone ‘son’, which was pronounced sŭ-ne (§ 6 vi).

Vowels. Short vowels ă, ĕ, ī, ŏ, ŭ (§ 6 vi) were pronounced respectively as in French patte, English pet, pit, pot, put. Final unstressed -e was generally syllabic, with a sound something like the final sound in China (§ 9).

The long vowels ā, ī, ū (§ 6 v) were pronounced approximately as in father, machine, crude. But ē and ō present special difficulties, because the spelling failed to make the broad distinction between open ![]() and close

and close ![]() , open

, open ![]() and close

and close ![]() — a distinction which, though relative only (depending on the greater or less opening of the mouth passage), is proved to have been considerable by ME. rimes, and by the earlier and subsequent history of the long sounds represented in ME. by e, o.

— a distinction which, though relative only (depending on the greater or less opening of the mouth passage), is proved to have been considerable by ME. rimes, and by the earlier and subsequent history of the long sounds represented in ME. by e, o.

(i) Open ![]() (as in broad) derives:

(as in broad) derives:

(a) from OE. ā, according to § 7 b i: OE. brād, bāt, báld > ME. br![]() d, b

d, b![]() t, b

t, b![]() ld > NE. broad, boat, bold. The characteristic modern spelling is thus oa.

ld > NE. broad, boat, bold. The characteristic modern spelling is thus oa.

(b) from OE. ![]() in open syllables according to § 7 a iii: OE. brŏcen > ME. br

in open syllables according to § 7 a iii: OE. brŏcen > ME. br![]() cen(n) > NE. broken.

cen(n) > NE. broken.

NOTE.—In many texts the rimes indicate a distinction in pronunciation between ![]() derived from OE. ā and

derived from OE. ā and ![]() derived from OE. ŏ, and the distinction is still made in NW. Midland dialects.

derived from OE. ŏ, and the distinction is still made in NW. Midland dialects.

(ii) Close ![]() (pronounced rather as in French beau than as in standard English so which has developed a diphthong ọu), derives from OE. ō : OE. gōs, dōm, góld > ME. g

(pronounced rather as in French beau than as in standard English so which has developed a diphthong ọu), derives from OE. ō : OE. gōs, dōm, góld > ME. g![]() s, d

s, d![]() m, g

m, g![]() ld > NE. goose, doom, gold. The characteristic modern spelling is oo.

ld > NE. goose, doom, gold. The characteristic modern spelling is oo.

NOTE.—(1) After consonant + w, ![]() often develops in ME. to

often develops in ME. to ![]() : OE. (al)swā, twā > ME. (al)s

: OE. (al)swā, twā > ME. (al)s![]() , tw

, tw![]() > later (al)s

> later (al)s![]() , tw

, tw![]() .

.

(2) In Scotland and the North ![]() becomes regularly a sound (perhaps

becomes regularly a sound (perhaps ![]() ) spelt u : gōd > gud, blōd > blud, &c.

) spelt u : gōd > gud, blōd > blud, &c.

Whereas the distribution of ![]() and

and ![]() is practically the same for all ME. dialects, the distinction of open

is practically the same for all ME. dialects, the distinction of open ![]() and close

and close ![]() is not so regular, chiefly because the sounds from which they derive were not uniform in OE. dialects. For simplicity, attention will be confined to the London dialect, as the fore-runner of modern Standard English.

is not so regular, chiefly because the sounds from which they derive were not uniform in OE. dialects. For simplicity, attention will be confined to the London dialect, as the fore-runner of modern Standard English.

(iii) South-East Midland open ![]() (pronounced as in there) derives:

(pronounced as in there) derives:

(a) from OE. (Anglian) ![]() : Anglian

: Anglian ![]() > SE. Midl. d

> SE. Midl. d![]() l > NE. deal;

l > NE. deal;

(b) from OE. ēa : OE. bēatan > ME. b![]() te(n) > NE. beat;

te(n) > NE. beat;

(c) from OE. ĕ in open syllables according to § 7 a iii: OE. mĕte > ME. m![]() te > NE. meat.

te > NE. meat.

The characteristic modern spelling is ea.

(iv) South-East Midland close ![]() (pronounced as in French été) derives:

(pronounced as in French été) derives:

(a) from OE. (Anglian) ē of various origins: Anglian hēr, mēta(n), (ge)lēfa(n) > SE. Midl. h![]() re, m

re, m![]() te(n), l

te(n), l![]() ue(n) > NE. here, meet, (be)lieve.

ue(n) > NE. here, meet, (be)lieve.

(b) from OE. ēo : OE. dēop, þēof > ME. d![]() p, b

p, b![]() f (þief) > NE. deep, thief.

f (þief) > NE. deep, thief.

The characteristic modern spellings are ee, and ie which already in ME. often distinguishes the close sound (§ 6 ii).

NOTE.—The distinction made above does not apply in South-Eastern (Kentish), because this dialect has ME. ea, ia, ya for OE. ēa (iii b), and OE. ē for Anglian ![]() (iii a). Nor does it hold for South-Western, because the West Saxon dialect of OE. had gelīefan for Anglian gelēfa(n) (iv a). West Saxon also had str

(iii a). Nor does it hold for South-Western, because the West Saxon dialect of OE. had gelīefan for Anglian gelēfa(n) (iv a). West Saxon also had str![]() t, -dr

t, -dr![]() dan, where normal Anglian had str

dan, where normal Anglian had str![]() t, -dr

t, -dr![]() da(n), but the distribution of the place-names Stratton beside Stretton, and of the pa. t. and pp. dradd(e) beside dredd(e) (p. 270 and n.), shows that the

da(n), but the distribution of the place-names Stratton beside Stretton, and of the pa. t. and pp. dradd(e) beside dredd(e) (p. 270 and n.), shows that the ![]() forms were common in the extreme South and the East of the Anglian area; so that in fourteenth-century London both

forms were common in the extreme South and the East of the Anglian area; so that in fourteenth-century London both ![]() and

and ![]() might occur in such words, as against regular West Midland and Northern

might occur in such words, as against regular West Midland and Northern ![]() .

.

In NE. Midland and Northern texts some ē sounds which we should expect to be distinguished as open and close rime together, especially before dental consonants, e. g. ![]() ēde (OE. ēode): lēde (Anglian l

ēde (OE. ēode): lēde (Anglian l![]() da(n)) I 152–3.

da(n)) I 152–3.

§ 9. INFLEXIONS. Weakening and levelling of inflexions is continuous from the earliest period of English. The strong stress falling regularly on the first or the stem syllable produced as reflex a tendency to indistinctness in the unstressed endings. The disturbing influence of foreign conquest played a secondary but not a negligible part, as may be seen from a comparison of some verbal forms in the North and the N. Midlands, where Norse influence was strongest, with those of the South, where it was inconsiderable:

and although tangible evidence of French influence on the flexional system is wanting (for occasional borrowings like gowtes artetykes IX 314 are mere literary curiosities), every considerable settlement of foreign speakers, especially when they come as conquerors, must shake the traditions of the language of the conquered. A third cause of uncertainty was the interaction of English dialects in different stages of development.

The practical sense of the speakers controlled and balanced these disruptive factors. There is no better field than Middle English for a study of the processes of vigorous growth: the regularizing of exceptional and inconvenient forms; the choice of the most distinctive among a group of alternatives; the invention of new modes of expression; the discarding of what has become useless.

At the beginning of the fourteenth century the inflexional endings are: -e; -en; -ene (weak gen. pl.); -er (comparative); -es; -est; with -eþ, -ede (-de, -te), -ed (-d, -t), -ynge (-inde, -ende, -ande), which are verbal only.

NOTE.—(a) Sometimes one of these inflexions may be substituted for another: e.g. when -es replaces -e as the Northern ending of the 1st sg. pres. ind. Such analogical substitutions must be distinguished from phonetic developments.

(b) In disyllabic inflexions like -ede, -ynge (-ande), final -e is lost early in the North. In polysyllables it is dropped everywhere during the century.

(c) The indistinct sound of flexional -e- covered by a consonant is shown by spellings with -i-, -y- : woundis X 51; madist XI b 214; blyndiþ XI b 7; fulfillid XVI 6; etin XIV b 76; brokynne XVI 195. And, especially in West Midland texts, -us, -un (-on) appear for -es, -en : mannus XI b 234; foundun XI a 47; laghton VII 119. Complete syncope sometimes occurs: days I 198, &c.

Otherwise all the inflexions except -e, -en, are fairly stable throughout the century.

-en: In the North -en is found chiefly in the strong pp., where it is stable. In the South (except in the strong pp.) it is better preserved, occurring rarely in the dat. sg. of adjectives, e. g. onen III 4, dat. pl. of nouns, e. g. diaknen III 5, and in the infinitive; more commonly in the weak pl. of nouns, where it is stable, and in the pa. t. pl., where it alternates with -e. In the Midlands -en, alternating with -e, is also the characteristic ending of the pres. ind. pl. As a rule (where the reduced ending -e is found side by side with -en) -e is used before words beginning with a consonant, and -en before words beginning with a vowel or h, to avoid hiatus. But that the preservation of -en does not depend purely on phonetic considerations is proved by its regular retention in the Northern strong pp., and its regular reduction to -e in the corresponding Southern form.

-e: Wherever -en was reduced, it reinforced final -e, which so became the meeting point of all the inflexions that were to disappear before Elizabethan times.

-e was the ending of several verbal forms; of the weak adjective and the adjective pl.; of the dat. sg. of nouns; and of adverbs like faste, deepe, as distinguished from the corresponding adjectives fast, deep.

That -e was pronounced is clear from the metres of Chaucer, Gower, and most other Southern and Midland writers of the time. For centuries the rhythm of their verse was lost because later generations had become so used to final -e as a mere spelling that they did not suspect that it was once syllabic.

But already in fourteenth-century manuscripts there is evidence of uncertainty. Scribes often omit the final vowel where the rhythm shows that it was syllabic in the original (see the language notes to I, II). Conversely, in Gawayne forms like burne (OE. beorn), race (ON. rás), hille (OE. hyll) appear in nominative and accusative, where historically there should be no ending. The explanation is that, quite apart from the workings of analogy, which now extended and now curtailed its historical functions, -e was everywhere weakly pronounced, and was dropped at different rates in the various dialects. In the North it hardly survives the middle of the century (IV a, X). In the N. Midlands its survival is irregular. In the South and S. Midlands it is fairly well preserved till the end of the century. But everywhere the proportion of flexionless forms was increasing. It may be assumed that, in speech as in verse, final -e was lost phonetically first before words beginning with a vowel or h.

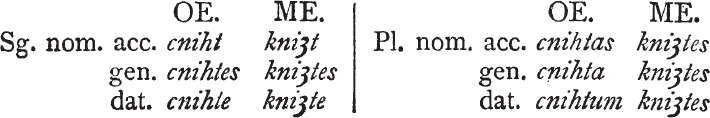

§ 10. NOUNS: Gender, which in standard West Saxon had been to a great extent grammatical (i. e. dependent on the forms of the noun), was by the fourteenth century natural (i.e. dependent on the meaning of the noun). This change had accompanied and in some degree facilitated the transfer of nearly all nouns to the strong masculine type, which was the commonest and best defined in late OE.:

In the North final -e of the dat. sg. was regularly dropped early in the fourteenth century, and even in the South the dat. sg. is often uninflected, probably owing to the influence of the accusative. In the plural the inflexion of the nom. acc. spreads to all cases; but in early texts, and relatively late in the South, the historical forms are occasionally found, e.g. gen. pl. cniste (MS. cnistes) XV g 30 (note), dat. pl. diaknen III 5.

Survivals: (i) The common mutated plurals man : men, fot : fet, &c., are preserved, and in VIII b a gen. pl. menne (OE. manna) occurs; ky pl. of cow forms a new double pl. kyn, see (iii) below; hend pl. of hand is Norse, cp. XVI 75 (note).

(ii) Some OE. neuters like shep ‘sheep’ VIII b 18, ![]() er ‘year’ II 492, þing II 218, folk II 389, resist the intrusion of the masculine pl. -es in nominative and accusative. Pl. hors II 304, XIII a 34 remains beside horses XIV b 73; but deores ‘wild animals’ occurs at XV b 29, where Modern English preserves deer.

er ‘year’ II 492, þing II 218, folk II 389, resist the intrusion of the masculine pl. -es in nominative and accusative. Pl. hors II 304, XIII a 34 remains beside horses XIV b 73; but deores ‘wild animals’ occurs at XV b 29, where Modern English preserves deer.

(iii) In the South the old weak declension with pl. -en persists, though by the fourteenth century the predominance of the strong type is assured. The weak forms occur not only where they are historically justified, e.g. ey![]() en (OE. ēagan) II III, but also by analogy in words like honden (OE. pl. honda) II 79, tren (OE. pl. trēo) XIII a 51, platen (OFr. plate) XV g 4. The inflexion still survives in three double plural formations: children VIII b 70 beside childer (OE. pl. cildru); bretheren VIII a 201 beside brether XVII 320 (OE. pl. brōþor); and ky

en (OE. ēagan) II III, but also by analogy in words like honden (OE. pl. honda) II 79, tren (OE. pl. trēo) XIII a 51, platen (OFr. plate) XV g 4. The inflexion still survives in three double plural formations: children VIII b 70 beside childer (OE. pl. cildru); bretheren VIII a 201 beside brether XVII 320 (OE. pl. brōþor); and ky![]() n IX 256 for ky (cp. (i) above). The OE. weak gen. pl. in -ena leaves its traces in the South, e.g. knauene VIII b 56, XV h 4, and unhistorical lordene VIII b 77.

n IX 256 for ky (cp. (i) above). The OE. weak gen. pl. in -ena leaves its traces in the South, e.g. knauene VIII b 56, XV h 4, and unhistorical lordene VIII b 77.

(iv) The group fader, moder, broþer, doghter commonly show the historical flexionless gen. sg., e.g. doghtyr arme I 136; moder wombe XI b 29 f.; brother hele XII a 18; Fadir voice XVI 79.

(v) The historical gen. sg. of old strong feminines remains in soule dede (OE. sāwle) I 212; but Lady day (OE. hl![]() fdigan dæg) I 242 is a survival of the weak fem. gen. sg.

fdigan dæg) I 242 is a survival of the weak fem. gen. sg.

§ 11. ADJECTIVES. Separate flexional forms for each gender are not preserved in the fourteenth century; but until its end the distinction of strong and weak declensions remains in the South and South Midlands, and is well marked in the careful verse of Chaucer and Gower. The strong is the normal form. The weak form is used after demonstratives, the, his, &c., and in the vocative. As types god (OE. gōd) ‘good’ and grēne (OE. grēne) ‘green’ will serve, because in OE. grēne had a vowel-ending in the strong nom. sg. masc., while gōd did not. The ME. paradigms are:

Examples: Strong sg. a gret serpent (OE. grēat) XII b 72; an unkindė man (OE. uncynde) XII b 1; a stillė water (OE. stille) XII a 83. Weak sg. The gretė gastli serpent XII b 126; hire oghnė hertes lif XII a 4; O lef liif (where the metre indicates leuė; for the original) II 102. Strong pl. þer wer widė wones II 365. Weak pl. the smalė stones XII a 84.

Note that strong and weak forms are identical in the plural; that even in the singular there is no formal distinction when the OE. strong masc. nom. ended in a vowel (grēne); that monosyllables ending in a vowel (e.g. fre), polysyllables, and participles, are usually invariable; and that regular dropping of final -e levels all distinctions, so that the North and N. Midlands early reached the relatively flexionless stage of Modern English.

Survivals. The Ayenbyte shows some living use of the adjective inflexions. Otherwise the survivals are limited to set phrases, e.g. gen. sg. nones cunnes ‘of no kind’, enes cunnes ‘of any kind’, XV g 20, 22. That the force of the inflexion was lost is shown by the early wrong analysis no skynnes, al skynnes, &c.

Definite Article. Parallel to the simplification of the adjective, the full OE. declension sē, sēo, þæt, &c., is reduced to invariable þe. The Ayenbyte alone of our specimens keeps some of the older distinctions. Elsewhere traces appear in set phrases, e.g. neut. sg. þat, þet in þat on ‘the one’, þat oþer ‘the other’ V 344, and, with wrong division, þe ton XI b 27, the toþer IX 4; neut. sg. dat. þen (OE. þ![]() m), with wrong division, in atte nale (for at þen ale) VIII a 109.

m), with wrong division, in atte nale (for at þen ale) VIII a 109.

§ 12. PRONOUNS. In a brilliant study (Progress in Language, London 1894) Jespersen exemplifies the economy and resources of English from the detailed history of the Pronoun. In the first and second persons fourteenth-century usage does not differ greatly from that of the Authorized Version of the Bible. But the pronoun of the third person shows a variety of developments. In the singular an objective case replaces, without practical disadvantages, the older accusative and dative: him (OE. hine and him), her(e) (OE. hīe and hiere), (h)it (OE. hit and him). The possessive his still serves for the neuter as well as the masculine, e.g. þat ryuer … chaungeþ hys fordes XIII a 55 f.; though an uninflected neuter possessive hit occasionally appears in the fourteenth century. In the plural, where one would expect objective him from the regular OE. dat. pl. him, clearness is gained by the choice of unambiguous hem, from an OE. dat. pl. by-form heom.

But as we see from Orfeo, ll. 408, 446, 185, in some dialects the nom. sg. masc. (OE. hē), nom. sg. fem. (OE. hēo), and nom. pl. (OE. hīe), had all become ME. he. The disadvantages of such ambiguity increased as the flexional system of nouns and adjectives collapsed, and a remedy was found in the adoption of new forms. For the nom. sg. fem., s(c)he, s(c)ho (mostly Northern), come into use, which are probably derived from s![]() ē, s

ē, s![]() ō, the corresponding case of the definite article. The innovation was long resisted in the South, and ho, an unambiguous development of heō, remains late in W. Midland texts like Pearl.

ō, the corresponding case of the definite article. The innovation was long resisted in the South, and ho, an unambiguous development of heō, remains late in W. Midland texts like Pearl.

In the nom. pl. ambiguous he was replaced by bei, the nom. pl. of the Norse definite article. This is the regular form in all except the Southern specimens II (orig.), III, XIII. And although the full series of Norse forms þei, þeir, þe(i)m is found in Orm at the beginning of the thirteenth century, Chaucer and other Midland writers of the fourteenth century as a rule have only þei, with native English her(e), hem in the oblique cases. (For details see the language note to each specimen.)

The poss. pl. her(e), beside hor(e), was still liable to confusion with the obj. sg. fem. her(e), cp. II 92. Consequently this was the next point to be gained by the Norse forms, e.g. in VII 181. In the Northern texts X, XVI, XVII, all from late MSS., the Norse forms þai, þa(i)r, þa(i)me are fully established; but (h)em, which was throughout unambiguous, survived into modern dialects in the South and Midlands.

Note the reduced nominative form a ‘he’, ‘they’ in XIII; and the objective his(e) ‘her’, ‘them’ in III, which has not been satisfactorily explained.

Relative: The general ME. relative is þat, representing all genders and cases (note to XV i 4). Sometimes definition is gained by adding the personal pronoun: þat … he (sche) = ‘who’; þat … it = ‘which’; þat … his = ‘whose’; þat … him = ‘whom’, &c.; e.g. a well, þat in the day it is so cold IX 5–6, cp. V 127 (note); oon That with a spere was thirled his brest-boon ‘one whose breast-bone was pierced with a spear’, Knight’s Tale 1851. For the omission of þat see note to XIII a 36.

In later texts, which, properly an interrogative, appears commonly as a relative, both with personal and impersonal antecedents, e.g. Alceone … which … him loveth XII a 3 ff.; þat steede … fro whilke þe feende fell XVI 13 f. Under the influence of French lequel, &c., which is often compounded with the article þe, e.g. a gret serpent … the which Bardus anon up drouh XII b 72 f.; no thing of newe, in the whiche the hereres myghten hauen … solace IX 275 f. Further compounding with þat is not uncommon, e.g. the queen of Amazoine, the whiche þat maketh hem to ben kept in cloos IX 190 f.

More restricted is the relative use of whos, whom, which are originally interrogatives, though both are found very early in ME. as personal relatives. Examples of the objective after prepositions are: my Lady, of quom … VI 93; God, fro whom … IX 328 f.; my Sone … in whome XVI 81 f. The possessive occurs in Seynt Magne … yn whos wurschyp 1 90 f.; I am … the same, whos good XII b 78 f.; and, compounded with the article, in Morpheüs, the whos nature XII a 113. The nominative who retains its interrogative meaning, e.g. But who ben more heretikis? XI b 77 f.; or is used as an indefinite, e.g. a tasse of grene stickes … to selle, who that wolde hem beie XII b 22 ff.; but it is never used as a relative; and probably what in XVI 174 is better taken as in apposition to myghtis than as a true relative.

§ 13. VERB. Syntactically the most interesting point in the history of the ME. verb is the development of the compound tenses with have, be, will, shall, may, might, mun, can, gan. But the flexional forms of the simple tenses are most subject to local variation, and, being relatively common, afford good evidence of dialect. Throughout the period, despite the crossings and confusions that are to be expected in a time of uncertainty and experiment, the distinction between strong and weak verbs is maintained; and it will be convenient to deal first with the inflexions common to both classes, and then to notice the forms peculiar to one or the other.

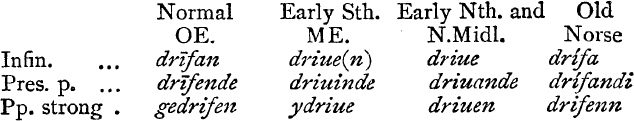

(i) The Infinitive had already in Northumbrian OE. lost final -n: drīfa ‘to drive’. Hence in ME. of the North and N. Midlands the ending is -e, which becomes silent at varying rates during the fourteenth century; e.g. dryue I 171, to luf IV a 17. In the South and S. Midlands the common ending is -e, e.g. telle III 3, which usually remains syllabic to the end of the century; but -(e)n is also found, especially in verse to make a rime or to avoid hiatus: e.g. sein (: a![]() ein) XII a 27; to parte and

ein) XII a 27; to parte and ![]() iven half his good XII b 201.

iven half his good XII b 201.

(ii) The Present Participle (OE. drīfende) in the North and N. Midlands ends in -and(e), though -yng(e), -ing(e) is beginning to appear in V, VII, XVI, XVII. In S. Midlands the historical ending -ende still prevails in Gower; but Chaucer has more commonly -yng(e); and in IX, XI, both late texts, only -yng(e) appears. In the South -yng(e) is established as early as the beginning of the century, e.g. in II.

N.B. Carefully distinguish the verbal noun which always ends in -yng(e). Early confusion resulted in the transference of this ending to the participle.

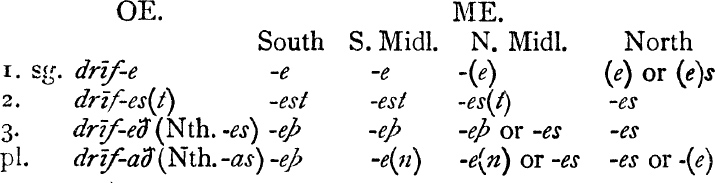

(iii) Present Indicative.

(a) Singular: OE. 1 drīfe, 2 drīf(e)s(t), 3 drīf(e)ð (late Northumbrian drīfes).

In ME. -e, -est, -eþ are still the regular endings for the South and most of the Midlands. Shortened forms like fint = findeþ II 239; stant = standeþ XII a 74 are commonest in the South, where in OE. they were a feature of West Saxon and Kentish as distinguished from Anglian. Distinct are the Northern and N. Midland mas(e) ‘makes’, tas ‘takes’, with contracted infinitives ma, ta; and bus ‘behoves’, which Chaucer uses in his imitation of Northern English, Reeves Tale 172.

In N. Midlands the modern 3rd sg. -(e)s is common (V, VI, but not in earlier I). Farther North it is invariable (IV, X, XVI, XVII). The distribution of -es as the ending of the 2nd sg. is the same, and it is extended even to the 1st person.

(b) Plural: OE. drīfað (late Northumbrian drīfas).

Only Southern ME. retains the OE. inflexion as -eþ (II, III, XIII). The Midland ending, whence the modern form derives, is -e(n); though in the N. Midlands -es occasionally appears. Northern has regularly -es, unless the personal pronoun immediately precedes, when the ending is -e, as in the Midlands, e.g. þei make XVI 103.

N.B. In applying this test, care must be taken to exclude inversions, which are subject to special rules; to distinguish the subjunctive (e.g. falle XIII a 52, drawe XIII b 6) from the indicative; and, generally, to choose examples that are syntactically free from doubt, because concord of number is not always logical in ME.

SUMMARY.

(iv) The Imperative Plural might be expected to agree with the pres. ind. pl. In fact it has the ending -eþ not merely in the South, but in most of the Midlands, e.g. I, VIII, Gower and Chaucer. Northern and NW. Midland (V, VI, XIV b, XVI) have commonly -es. But Chaucer, Gower, and most late ME. texts have, beside the full inflexion, an uninflected form, e.g. vndo XVI 182.

(v) Past Tense.

(a) Strong: The historical distinctions of stem-vowel were often obscured in ME. by the rise of new analogical forms, the variety of which can best be judged from the detailed evidence presented in the New English Dictionary under each verb. But, for the common verbs or classes, the South and S. Midlands preserved fairly well the OE. vowel distinction of past tense singular and plural; while North and N. Midlands usually preferred the form proper to the singular for both singular and plural, e.g. þey bygan I 72; þey ne blan I 73; thai slang X 53, where OE. has sg. gan : gunnon; blan : blunnon; ON. sl![]() ng : slungu.

ng : slungu.

(b) Weak: In the South and Midlands the weak pa. t. 2nd sg. usually ends in -est (N. Midland also -es): hadest II 573; cursedest I 130; kyssedes, ra![]() te

te![]() V 283. In the North, and sometimes in N. Midland, it ends in -(e): þou hadde XVI 219. The full ending of the pa. t. pl. is fairly common in the South, S. Midlands, and NW. Midlands: wenten II 185, hedden III 42, maden XII b 196, sayden VI 174.

V 283. In the North, and sometimes in N. Midland, it ends in -(e): þou hadde XVI 219. The full ending of the pa. t. pl. is fairly common in the South, S. Midlands, and NW. Midlands: wenten II 185, hedden III 42, maden XII b 196, sayden VI 174.

(vi) Past Participle (Strong): OE. (ge)drĭfen.

In the North and N. Midlands the ending -en is usually preserved, but the prefix y- is dropped. In the South the type is y-driue, with prefix and without final n. S. Midland fluctuates—for example, Gower rarely, Chaucer commonly, uses the prefix y-.

(vii) Weak Verbs with -i- suffix: In OE. weak verbs of Class II formed the infinitive in -ian, e.g. acsian, lufian, and the i appeared also in the pres. ind. and imper. pl. acsiað and pres. p. acsiende. In ME. a certain number of French verbs with an -i- suffix reinforced this class. In the South and W. Midlands the -i- of the suffix is often preserved, e.g. aski II 467, louy V 27, and is sometimes extended to forms in which it has no historical justification, e.g. pp. spuryed V 25. In the North and the E. Midlands the forms without i are generalized.

1 Sufficient evidence is not available. If in the year 1340 at every religious house in the kingdom a native of the district had followed the example of Michael of Northgate, and if all their autograph copies had survived, we should have a very good knowledge of Middle English at that time. If the process had been repeated about every ten years the precision of our knowledge would be greatly increased. For the area in which any feature is found is not necessarily constant: we know that in the pres. p. the province of -ing was extending throughout the fourteenth century; that the inflexion -es in 3 sg pres. ind. was a Northern and North-Midland feature in the fourteenth century, but had become general in London by Shakespeare’s time. And though less is known about the spread of sound changes as distinct from analogical substitutions, it cannot be assumed that their final boundaries were reached and fixed in a moment. There is reason to regret the handicap that has been imposed on ME. studies by the old practice of writing in Latin or French the documents and records which would otherwise supply the exactly dated and localized specimens of English that are most necessary to progress.

2 The evidence of place-names does not agree entirely with the evidence of texts. Havelok, which is localized with reasonable certainty in North Lincolnshire, has (a)dradd in rimes that appear to be original, and these indicate a North-Eastern extension of the area in which OE. str![]() t, dr

t, dr![]() dan appear for normal Anglian strēt, drēda(n). This evidence, supported by rimes in Robert of Brunne, is too early to be disposed of by the explanation of borrowing from other dialects, nor is the testimony of place-names so complete and unequivocal as to justify an exclusive reliance upon it.

dan appear for normal Anglian strēt, drēda(n). This evidence, supported by rimes in Robert of Brunne, is too early to be disposed of by the explanation of borrowing from other dialects, nor is the testimony of place-names so complete and unequivocal as to justify an exclusive reliance upon it.