BUGGING OUT, or EATING on the RUN

LIVING OFF THE (WASTE) LAND

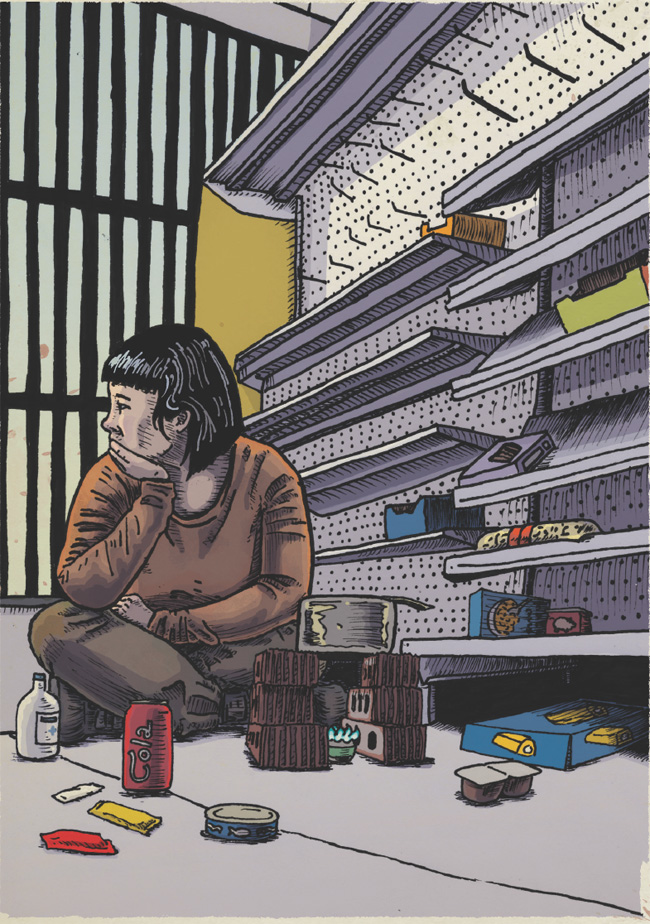

In the event that you choose to, or must, bug out, you will likely find yourself navigating “the wasteland”—that is, the abandoned homes, neighborhoods, towns, cities, and other structures that once made up what we affectionately remember as civil society. When imagining what the food supply might look like in an apocalyptic wasteland, the first thing I would recommend is to lower your expectations—significantly. Things might get bad. Like Carl Grimes-eating-cat-food bad. But don’t fret. With a little patience and planning, you can pull off some palatable wasteland eats.

Whether you are purposefully moving through the wasteland en route to a rumored survivor camp or simply shufffing about trying to stay alive, chances are you will be nomadic: moving from place to place day after day, scavenging for food and supplies while evading high densities of rotters. While the preceding sections of this book provided a cadre of skills you’ll find useful while scavenging the wasteland—namely, collecting and purifying water, hunting/trapping animals and insects, foraging, and possibly even growing your own food if you find a good place to squat—you may be forced to subsist solely on what the dregs of society can offer with intermittent access to green spaces and natural resources. Thus, the recipes and general tips in the following section are designed to help you make the most of those Twinkies, Spam, Slim Jims, and other long-term imperishable foods the wasteland has to offer.

WHO’S GOT YOUR BACK TUNA MAC

Living off the wasteland is no joke. After the initial outbreak, when most of humanity will have been picked off by the zeds like the ripe little cherries we are, finding food amid the tatters of society will be freaking tough. Finding an intact and unspoiled box of mac and cheese and a can of tuna is the equivalent, in zpoc terms, of hitting the jackpot.

There isn’t much skill involved in making a box of mac and cheese or opening a can of tuna (unless of course you don’t have a can opener), but I have included this recipe because not only does it include a good smattering of food groups, but also in all its processed junk-foody glory, it is a truly comforting dish after a long day of evading the horde. I have also included powdered butter and milk in place of the fresh varieties you’d have access to pre-zpoc—2 nonperishables that make excellent additions to any BOB. Hot sauce really is a must for this dish; otherwise, it can be quite bland, so hit up an abandoned restaurant and try to rustle up some packaged hot stuff.

Rummaging your way through the wasteland is also a great time to put some of those smaller, more portable stovetop hacks to the test—why not try out the Bevy Can Burner (page 242)? It’s excellent for stealthy indoor cooking.

YIELDS:

1 Hungry Survivor serving, 2 Regular Joe servings

REQUIRES:

1 mess kit or other scavenged pot

1 mess kit cup or other cup, mug, or small bowl

Wooden spoon or other cooking utensil

Can opener

HEAT SOURCE:

Direct, Bevy Can Burner (page 242) or other Stovetop Hack (page 42)

TIME:

15 minutes, largely unattended

INGREDIENTS:

1 box macaroni and cheese

2 tbsp. powdered butter

2¼ tsp. powdered milk

1 x 5-oz. can tuna (drained if in water)

2–4 packets takeout hot sauce

METHOD:

Set up a Bevy Can Burner or other Stove-top Hack and bring water to a boil over high heat. Cook the pasta as per the instructions on the box.

Set up a Bevy Can Burner or other Stove-top Hack and bring water to a boil over high heat. Cook the pasta as per the instructions on the box.

When the pasta is ready, make sure you remove and set aside about 1 cup of the cooking water.

When the pasta is ready, make sure you remove and set aside about 1 cup of the cooking water.

To the drained pasta, add the 2 tablespoons of powdered butter, 2¼ teaspoons of powdered milk, and the package of cheese sauce that was included in the box.

To the drained pasta, add the 2 tablespoons of powdered butter, 2¼ teaspoons of powdered milk, and the package of cheese sauce that was included in the box.

Add about ¼ cup of the reserved cooking water and stir. Add more pasta water in small increments until you get the level sauciness you desire.

Add about ¼ cup of the reserved cooking water and stir. Add more pasta water in small increments until you get the level sauciness you desire.

Add the canned tuna and mix until incorporated. Drizzle with a healthy amount of hot sauce. Eat immediately.

Add the canned tuna and mix until incorporated. Drizzle with a healthy amount of hot sauce. Eat immediately.

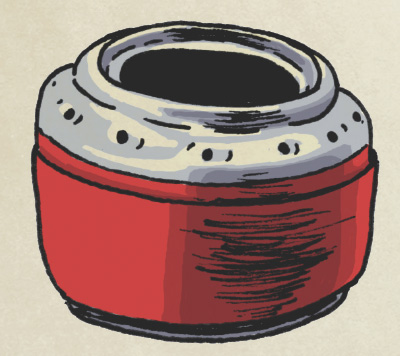

Building a Bevy Can Burner

Bevy can burners have been longtime favorites among ultra-lightweight backpackers and survivalists alike—they are easy to construct, very small, and weigh only about an ounce.

The most commonly used fuel for these stoves pre-zpoc is denatured alcohol, which you can try to scavenge in hardware stores and camping/military supply stores, or in the outdoor section of department stores. You could also use methyl alcohol. Often sold as paint thinner or gas line anti-freeze, it can be found at hardware stores, gas stations, etc.—but be forewarned that methyl alcohol has a higher toxicity and volatility than other fuels available.

Rubbing alcohol can also be used but has a lower alcohol content than denatured or methyl alcohol and so, given the bevy can burner’s design, might not get enough oxygen to burn. Grain alcohol (aka moonshine) is another option, clocking in at 95% alcohol (190 proof) and the only fuel mentioned here that is nontoxic to humans.

BEVY CAN BURNER

Because alcohol fuel burns so cleanly, bevy can burners are an excellent option for indoor cooking as they won’t produce any smoke. But be warned—alcohol burns with a near-invisible flame and any fuel spills that occur while the stove is burning could cause serious injury or fire. Do not handle the stove while it is in use!

WHAT YOU WILL NEED:

3 empty soda cans

3 empty soda cans

Metal shears or a sharp knife

Metal shears or a sharp knife

A permanent marker

A permanent marker

Measuring tape or ruler

Measuring tape or ruler

Heat-resistant tape or high-heat epoxy glue (useful, not essential)

Heat-resistant tape or high-heat epoxy glue (useful, not essential)

Make the top of your stove: Poke 16 evenly spaced holes into the outer rim of the bottom of one of the soda cans.

Make the top of your stove: Poke 16 evenly spaced holes into the outer rim of the bottom of one of the soda cans.

Cut out the smaller area inside this rim, effectively the bottom surface of the can.

Cut out the smaller area inside this rim, effectively the bottom surface of the can.

On the same can, mark off a line around the can that is ¾ inch from the bottom. Cut above this line for your first cut, then make a second cut on the line itself (it will be easier to make a good, clean cut this way). Discard the top portion of the can that you just cut off. If the cut edge on the bottom portion is jagged, sand it down using the file from your multi-tool.

On the same can, mark off a line around the can that is ¾ inch from the bottom. Cut above this line for your first cut, then make a second cut on the line itself (it will be easier to make a good, clean cut this way). Discard the top portion of the can that you just cut off. If the cut edge on the bottom portion is jagged, sand it down using the file from your multi-tool.

Make 8 evenly spaced vertical snips, about ¼ inch deep, along the rim to produce tabs. This is the top of your stove. Set aside for now.

Make 8 evenly spaced vertical snips, about ¼ inch deep, along the rim to produce tabs. This is the top of your stove. Set aside for now.

Make the bottom of your stove: Mark off a ring around a second soda can 1 inch from the bottom. Apply the same technique as in step 3, making 2 separate cuts to get to the final clean cut. This will be the bottom of your stove. Set aside for now.

Make the bottom of your stove: Mark off a ring around a second soda can 1 inch from the bottom. Apply the same technique as in step 3, making 2 separate cuts to get to the final clean cut. This will be the bottom of your stove. Set aside for now.

From the middle of the third can, cut out a section 1⅓ inches tall; this will be the inner wall of the stove.

From the middle of the third can, cut out a section 1⅓ inches tall; this will be the inner wall of the stove.

Place the strip, with ends overlapping, so that it sits directly on top of the inner rim of the stove’s bottom, pinch with your fingers to hold the strip at the appropriate size, then mark off the point halfway into the overlap—the spot where the 2 ends of the strip will need to lock together. Cut one slit into each side of the strip at that distance, but on opposite ends, so the 2 cuts can be used to lock the strip in place. Be sure that the ends are on the inside of the strip when locked together so that the outside forms a smooth ring.

Place the strip, with ends overlapping, so that it sits directly on top of the inner rim of the stove’s bottom, pinch with your fingers to hold the strip at the appropriate size, then mark off the point halfway into the overlap—the spot where the 2 ends of the strip will need to lock together. Cut one slit into each side of the strip at that distance, but on opposite ends, so the 2 cuts can be used to lock the strip in place. Be sure that the ends are on the inside of the strip when locked together so that the outside forms a smooth ring.

Cut 3 small notches, about ¼ inch deep and ½ inch wide, into this inner wall; these will allow the fuel to flow from the inner to the outer wall.

Cut 3 small notches, about ¼ inch deep and ½ inch wide, into this inner wall; these will allow the fuel to flow from the inner to the outer wall.

Put the inner wall, with notches facing downward, into the bottom of the stove.

Put the inner wall, with notches facing downward, into the bottom of the stove.

Nudge the tabs on the top of the stove so they point inward slightly; this will aid in fitting the top and bottom together. Slip the top of the stove (tabbed end first) into its bottom—this can be finicky so go slowly—and it should lock into place.

Nudge the tabs on the top of the stove so they point inward slightly; this will aid in fitting the top and bottom together. Slip the top of the stove (tabbed end first) into its bottom—this can be finicky so go slowly—and it should lock into place.

To secure the construction, tape it up with heat-resistant tape or glue it with high-heat epoxy, if available.

To secure the construction, tape it up with heat-resistant tape or glue it with high-heat epoxy, if available.

Fill the inner chamber about halfway for 15 minutes of high-heat cook time. Because alcohol is the fuel, the flame is nearly invisible; be very careful when lighting and do not handle it while it is burning (it will also be very hot) to avoid spills and serious injury.

Fill the inner chamber about halfway for 15 minutes of high-heat cook time. Because alcohol is the fuel, the flame is nearly invisible; be very careful when lighting and do not handle it while it is burning (it will also be very hot) to avoid spills and serious injury.

A small addition to the stove called a “simmer top” can be made from the top of another can, by cutting where the can starts to slope up at the top. When slipped on top of the stove, the simmer top will decrease the temperature and rate at which the fuel burns. With a simmer top, the stove can burn for upwards of 2 hours. Because it limits the oxygen exposure, only put the top on once the fire has established itself and has been burning for a few minutes. Carefully drop the simmer top onto the burning stove (or use tongs if they are available), then adjust gently so that it covers the stove.

To cook with the bevy can burner, you will need to fashion pot supports as you cannot put a pot directly on this stove. Rocks, bricks, a cylinder fashioned from sturdy mesh wire, etc., can be used to support your pot above the flame—just be sure it will not cut off the oxygen supply to the burner.

BACK TO BASICS BANNOCK

Bannock is a simple quick bread that can be made from as little as flour, baking powder, sugar/salt, and water. It’s perennially popular among campers and backpackers, who prep it ahead of time by measuring out the dry ingredients into a resealable plastic bag, then add water to make the dough when needed.

Vegetable shortening, like Spam and Twinkies, is another item that will probably have an uncomfortably long shelf life during the zpoc—manufacturers generally say 2 years if unopened and kept in a reasonably cool place, but the likelihood is that this product will be fine to eat long beyond that. If you can scavenge shortening (or some other form of appropriate fat, like oil), it will greatly improve this basic bread.

To cook bannock, fry the dough in a little fat, dry cook it in a pan over low heat or on embers, or wrap it around a stick and cook it over an open fire. This recipe is a sweet version featuring raisins and cinnamon, though you could just as easily include some minced and pan-crisped Slim Jims or Spam or whatever else you can get your hands on.

YIELDS:

1 Hungry Survivor, 2 Regular Joe servings

REQUIRES:

Mess kit bowl for mixing

Spoon or some other tool for stirring

Mess kit pan for cooking

HEAT SOURCE:

Direct, open flame or other Stovetop Hack (page 42)

TIME:

5 minutes prep

20 minutes bake time

INGREDIENTS:

1½ c. flour

1 tsp. baking powder

2 tbsp. sugar, preferably brown (or 2 sugar packets)

¼ tsp. salt

¾ tsp. cinnamon

2 tbsp. raisins

2 tbsp. vegetable shortening or oil

Scant ½ c. water

METHOD:

Set up a cooking fire or other Stove-top Hack. Over low heat, warm a mess kit frying pan.

Set up a cooking fire or other Stove-top Hack. Over low heat, warm a mess kit frying pan.

In a mess kit bowl, mix together all dry ingredients until blended. At this point you can store the dry ingredients in a resealable plastic bag to carry with you so they are ready when needed, if you’d like.

In a mess kit bowl, mix together all dry ingredients until blended. At this point you can store the dry ingredients in a resealable plastic bag to carry with you so they are ready when needed, if you’d like.

Add the oil and ¼ cup of the water and mix until combined. If the dough is still too dry to come together in a ball, add another tablespoon of water and mix until just incorporated. The dough should hold together in a shaggy ball and should not be sticky. Knead the dough a couple of times to smooth, then press it into a disk.

Add the oil and ¼ cup of the water and mix until combined. If the dough is still too dry to come together in a ball, add another tablespoon of water and mix until just incorporated. The dough should hold together in a shaggy ball and should not be sticky. Knead the dough a couple of times to smooth, then press it into a disk.

Add a very small amount of fat to the pan, just to prevent sticking, and spread it evenly so that the bottom of the pan is lightly coated. Put the dough into the preheated pan and cook over very low heat, which will allow the bread to cook through without burning, about 10 minutes per side. Test for doneness by sticking a sharp, skinny implement into the bread. It is ready when the implement comes out clean. Bannock is best enjoyed warm and will dry out completely within a day or so.

Add a very small amount of fat to the pan, just to prevent sticking, and spread it evenly so that the bottom of the pan is lightly coated. Put the dough into the preheated pan and cook over very low heat, which will allow the bread to cook through without burning, about 10 minutes per side. Test for doneness by sticking a sharp, skinny implement into the bread. It is ready when the implement comes out clean. Bannock is best enjoyed warm and will dry out completely within a day or so.

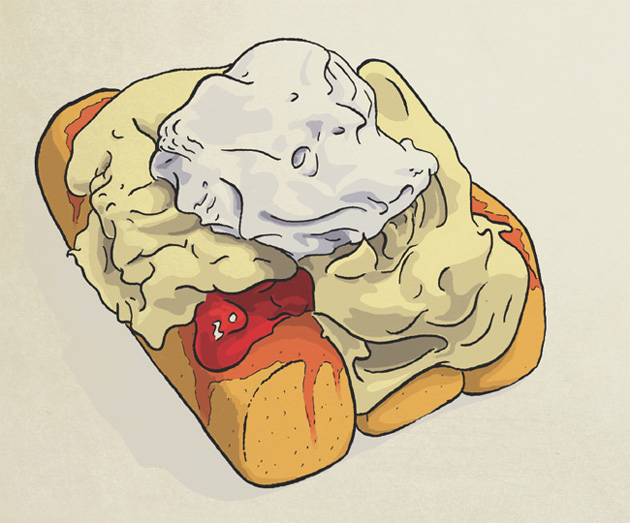

TWINKIE TRIFLE

You may remember the Twinkie scare of 2012—those few months when we thought the almighty Twinkie would disappear forever. Whichever side of the Twinkie debate you landed on pre-zpoc—Pollanite or cream-filled enthusiast—the fact that Twinkies returned from the grave (and have a seemingly endless afterlife) is good news for hungry, sweet-toothed survivors.

If I found a Twinkie while scavenging the wasteland during the zombie apocalypse, it would probably be ripped from its packaging and shoved in my face faster than you can say “Hostess.” Nonetheless, here is a slightly more “refined” way to enjoy Twinkies, in case you find yourself with a surplus of the snack cakes, or perhaps find yourself in Montreal and happen upon the commercial bakery that produces them.

YIELDS:

1 Hungry Survivor or Regular Joe serving

REQUIRES:

1 bowl

TIME:

5 minutes prep

INGREDIENTS:

3 Hostess Twinkies

2 tbsp. canned pineapple juice (optional, if available)

2 packets fruit jam (or 2 tbsp.)

½ single-serve vanilla pudding pack

2 tbsp. marshmallow fluff (optional, if available)

METHOD:

Lay the Twinkies at the bottom of a small bowl.

Lay the Twinkies at the bottom of a small bowl.

Drizzle the pineapple juice (if available) over the cakes to moisten them, then spread a thin layer of fruit jam over top.

Drizzle the pineapple juice (if available) over the cakes to moisten them, then spread a thin layer of fruit jam over top.

Cover with half the pudding pack. Top with marshmallow fluff, if available. Enjoy immediately.

Cover with half the pudding pack. Top with marshmallow fluff, if available. Enjoy immediately.

The Incredible, Edible Spam

Oh, Spam. The often sneered at and ubiquitous canned meat actually had quite humble beginnings at the family-run Hormel Foods Corporation in 1937; it originated as a way to use shoulder cuts of pork. With the arrival of WWII, the affordable and shelf-stable protein was cemented into American culture by feeding soldiers overseas.

Today Spam remains an inescapable icon of American food. Pre-zpoc it is a love/hate food, the butt of many jokes, and, thanks to Monty Python, the namesake for the email phenomenon. Post-zpoc it will be one of the most sought-after scavengeable foods.

Tons of salt and a dash of nitrites give Spam its staying power, and when the undead are trying to get your gray matter, you will be glad to find a can of this pink matter. If you happen to be in or around Minnesota or Nebraska, you might be able to scavenge direct from the source: Spam is produced in 2 facilities, one in Austin, Minnesota, and one in Fremont, Nebraska. Food scientist and author Harold McGee even recommends aging Spam for 5-plus years to give it a softer texture and better crunch when frying (see Like a Fine Wine, page 94, for other canned foods that do well with aging).

Though it is cooked and can be eaten straight from the can, the best way to enjoy Spam is panfried until crispy. And because it is reasonably bland, you can use it in any number of ways—in instant ramen, in a fried rice, as kabobs with canned pineapple, in a Hawaiian rice/Spam/nori sandwich (see End Times Musubi, below), or as an added bonus in boxed macaroni ’n’ cheese or canned soups/stews.

END TIMES MUSUBI

Spam musubi is a hugely popular grab-and-go snack food often found in Hawaiian convenience stores. It is sort of like a little Japanese inspired Spam sandwich—a compact handheld rice and Spam concoction wrapped in nori.

To make this wasteland gem yourself, all you’ll need is a can of Spam, rice, nori, and soy sauce—all ingredients with excellent shelf lives that could be found with a little dedicated scavenging. And you can use the Spam tin as a mold, so it requires no specialized equipment either. If you can find some takeout packages of mayo that are still palatable, they will make an excellent dipping sauce.

YIELDS:

2 Hungry Survivor servings, 4 Regular Joe servings (8 Musubi)

REQUIRES:

1 medium pot with lid

Baking sheet or some other clean, flat surface

1 frying pan

Tongs or fork, for flipping

HEAT SOURCE:

Direct, Bevy Can Burner (page 242) or other Stovetop Hack (page 42)

TIME:

30 minutes prep

5 minutes assembly time

INGREDIENTS:

4 c. potable water

2 c. white rice, preferably medium-grain

Salt, to taste

1 can Spam

4 packets takeout soy sauce (about 4 tbsp.)

2 sheets Nori

4 packets takeout mayo (or more to taste, if available)

METHOD:

Set up a Bevy Can Burner or Stovetop Hack and pot supports. Add the water, rice, and a pinch of salt to a medium pot. Bring to a boil over high heat, then cover, adding the simmer lid to cook on very low heat until the rice is done—about 15 minutes. Remove the pot from the heat and let sit, covered, for 5 minutes. Spread the rice out on a baking sheet or other clean surface and let it dry out while you prepare the Spam.

Set up a Bevy Can Burner or Stovetop Hack and pot supports. Add the water, rice, and a pinch of salt to a medium pot. Bring to a boil over high heat, then cover, adding the simmer lid to cook on very low heat until the rice is done—about 15 minutes. Remove the pot from the heat and let sit, covered, for 5 minutes. Spread the rice out on a baking sheet or other clean surface and let it dry out while you prepare the Spam.

Remove the simmer lid from your burner and heat a frying pan, adding more fuel if needed. In the meantime, open the Spam and set aside the tin for later use. Slice the Spam into 8 equal slices. Fry the pieces (in 2 batches if needed) in the heated pan until nicely browned and crispy on both sides, about 2 minutes per side. Add 2 packets (1 if frying in batches) of soy sauce and let it cook off/reduce to a nice slightly syrupy coating on the Spam. Flip the Spam pieces and repeat.

Remove the simmer lid from your burner and heat a frying pan, adding more fuel if needed. In the meantime, open the Spam and set aside the tin for later use. Slice the Spam into 8 equal slices. Fry the pieces (in 2 batches if needed) in the heated pan until nicely browned and crispy on both sides, about 2 minutes per side. Add 2 packets (1 if frying in batches) of soy sauce and let it cook off/reduce to a nice slightly syrupy coating on the Spam. Flip the Spam pieces and repeat.

Scoop about ¼ cup of rice into the bottom of the Spam tin and press down firmly to make a uniform layer—be careful, though the edges of the can are not generally sharp. Add a piece of the fried Spam, then cover with another ¼ cup of rice. Press it down firmly, then flip the tin and give it a gently tap to release the rice/ Spam sandwich. Wrap in a ⅓ sheet of nori, then repeat for the remaining 7 musubi. Top each with a squeeze of packet mayo and eat immediately.

Scoop about ¼ cup of rice into the bottom of the Spam tin and press down firmly to make a uniform layer—be careful, though the edges of the can are not generally sharp. Add a piece of the fried Spam, then cover with another ¼ cup of rice. Press it down firmly, then flip the tin and give it a gently tap to release the rice/ Spam sandwich. Wrap in a ⅓ sheet of nori, then repeat for the remaining 7 musubi. Top each with a squeeze of packet mayo and eat immediately.

WASTELAND CUPCAKES

Oh how cute! Cupcakes at the end of the world! Regardless of how you feel about the pre-dead-walking cupcake craze (which could be likened to a form of zombiism, I suppose), this is a recipe that makes good use of an ingredient you might very well come across in an abandoned kitchen cupboard or find accidentally nudged under a convenience store shelving unit: boxed cake mix.

What’s a survivor to do with a boxed cake mix when there are clearly no fresh eggs in sight? As long as you can get your hands on a can of soda, you’ll be in business. A regular 12-ounce can of soda (classic cola, grape, orange, whatever) will replace both the oil and eggs, leaving you with a delicious (?) wasteland dessert. In an ideal post-apocalyptic world, you could put some thought into pairing the cola with the cake: a clear mild-mannered or fruit-flavored soda with vanilla cake, or classic cola with chocolate cake. But in times like these you’re probably just going to have to use whatever you can get.

Because this cake tends to break apart easily, you’ll have most success baking it as cupcakes in a scavenged muffin tin (if you can find one). Otherwise, use any form of metallic baking pan (loaf, cake, Bundt pan, etc.). If you can also scavenge some cooking spray or parchment paper to line the cooking vessel(s), major bonus.

YIELDS:

1 x 9″ cake or about 24 cupcakes

REQUIRES:

1 large mixing bowl

1 spoon or other tool for mixing

1 muffin tin, 9″ cake pan, or other scavenged baking vessel

HEAT:

Indirect, Ammo Can Oven or other Oven Hack (page 44)

TIME:

2 minutes prep

Approximately 10−30 minutes attended baking time, depending on vessel

INGREDIENTS:

1 box cake mix

1 x 12-oz. can of soda

METHOD:

Set up an Ammo Can Oven or other Oven Hack for 350°F baking (see Judging Temperature, page 47)). If you can, grease the baking vessel you are using or line it with parchment paper.

Set up an Ammo Can Oven or other Oven Hack for 350°F baking (see Judging Temperature, page 47)). If you can, grease the baking vessel you are using or line it with parchment paper.

Dump the dry mix into a large mixing bowl. Add the soda and mix until just combined. Pour into the baking vessel(s). Baking time will depend largely on what baking vessel you have available and the brand of cake mix you are using. Consult the box for recommended baking time, but generally the cake will be ready when the top(s) look set and a toothpick or knife stuck into the middle comes out clean—roughly 15 minutes in a muffin tin or 25 minutes in a 9-inch cake pan. Cool before eating.

Dump the dry mix into a large mixing bowl. Add the soda and mix until just combined. Pour into the baking vessel(s). Baking time will depend largely on what baking vessel you have available and the brand of cake mix you are using. Consult the box for recommended baking time, but generally the cake will be ready when the top(s) look set and a toothpick or knife stuck into the middle comes out clean—roughly 15 minutes in a muffin tin or 25 minutes in a 9-inch cake pan. Cool before eating.