ESSENTIAL

SKILLS for the

HUNGRY

SURVIVOR

SURVIVAL IS THE ART OF STAYING ALIVE.

It’s safe to say that most of us have few, if any, basic survival skills. At least in the way I mean “survival”—that is, in the absence of all the modern conveniences and systems on which we have become so dependent. Do you know how to build a fire? Do you know how to obtain drinkable water? Do you know where to find food in the wild? If an undead plague were to hit tomorrow, most of us would provide a veritable smorgasbord of hors d’oeuvres with which the zeds could kick off their engorgement on the human race. And if by some stroke of luck or cunning you managed to escape immediate danger, chances are you might very well die of dehydration or starvation.

If you are part of that special class of “paranoid” subculture we lovingly call “prep-pers” or have a clear and useful memory of your time in Boy Scouts or Girl Scouts, you probably will not need the essential skills outlined in the following pages. The rest of us should master these skills before the undead uprising and practice until proficient. Whether bugging in or bugging out, these skills are essential to surviving an onslaught of decomposing cannibalistic monsters.

Water

Water is used in most of our body’s essential functions: temperature regulation, waste elimination, and digestion, among others. Under normal day-to-day circumstances, humans need 2–4 quarts (or liters) to replenish the water lost from regular body function. If it is hot, or you are doing excessive running or brain smashing, this amount naturally increases.

You will very quickly feel the ill effects of dehydration in a survival situation, especially one where you are running for dear life. Dry mouth, dizziness, nausea, muscle cramps, reduced hearing, and failing eyesight are among the urgent signs that you are in need of water. Of course, these signs might also mean you have been infected but in the absence of a bite mark, missing ear, or large hole in your abdomen, chances are you’re just dehydrated.

Remember the “Survival Rule of 3s”: Humans can generally live for 3 minutes without air, 3 days without water, and 3 weeks without food. Therefore (assuming the zombie plague isn’t airborne), procuring water should be your first priority when out in the wild or wasteland, followed by purifying any water you find so that it is drinkable, and developing a system for preserving this water for later use.

PROCURING

If you are grinding it out in the wasteland, scavenging for water will not be an easy task. Bottled water is one of the supplies that will be frantically and viciously fought over during the initial outbreak. It’s also a resource that looters and raiders will prize highly, meaning you aren’t likely to find much bottled water lying around for the taking and you should protect whatever stores you have.

It is hard to know how long our pipes will continue to deliver a potable water supply—that largely depends on how long it takes for your local power grid to go down and the people running your municipal purification facilities to inevitably flee in sheer terror.

If you are bugging in, assemble a cadre of containers for water storage and fill all that you can from your pipes during the initial outbreak (food-safe 50-gallon buckets/drums are good for this purpose, as are products like the waterBOB® bathtub bladder). These containers can be used for rainwater collection later as well (see A Hydrated Survivor Is a Happy Survivor, page 206). It would also be prudent to have a stockpile of bottled water in storage, if possible.

TIP: Your hot-water tank (and those of your recently reanimated neighbors!) will also have some potable water stored inside that will be accessible to you in a pinch.

When bugging out or looking for water in the wilderness, first try any known and close-by sources of surface water: lakes, streams, ponds. Survey your surroundings and look for lower ground, as water drains downhill. It is generally best to avoid stagnant water (see When Should You Pass on Water?, opposite), and purify any water you find out and about in the wilderness.

If you can’t find surface water, watch for wildlife. If you see squirrels, raccoons, birds, or insects, then chances are there is a water source nearby. Quietly observe their routes, and they should eventually lead you to a water source.

In dire situations you could try digging into the water table for water: Look for low ground lush with vegetation. Find moist earth, dig a hole, and let it gradually fill with groundwater. A solar still (pictured) is another option when water is scarce, as is wrapping a clean T-shirt or other absorbent fabric around your ankles and then walking through a wet dewy field before the sun has come up.

SOLAR STILL

PURIFYING

There are three common ways to treat water once you’ve collected it: using some form of filtration, boiling it, or using a chemical purifier (tablet or liquid form). Often two or more of these methods are used together for optimal results, though a rolling boil for 1–3 minutes is always a fail-safe way to kill off bacteria and pathogens.

The easiest and most effective way to treat water while on the run is with an all-in-one portable filter. These filters, which were developed for hikers, campers, and survival enthusiasts, generally have a high capacity and remove all debris, particulate, and virtually all harmful bacteria and pathogens. The Sawyer Squeeze filtration system ($40) filters up to 1,000,000 gallons, is extremely easy to clean, and weighs only 3 ounces.

FILTRATION TEEPEE

If you don’t have access to modern filtration systems or chemical treatments, you can improvise a filtration system, like a filtration teepee (pictured), to remove debris and some bacteria. In a soda bottle or a teepee constructed using wood and clean fabric, filter the water through alternating layers of nonpoisonous vegetation, sand, and hardwood charcoal from your fire. Follow this treatment with boiling to kill off any remaining bacteria or pathogens.

Rainwater can also be a source of drinking water, though it should be boiled first. Pay special attention to the surfaces and vessels with which your water comes into contact, because even boiling cannot remove chemical contaminants that might come from treated rooftops or non-food-safe storage containers. See A Hydrated Survivor Is a Happy Survivor (page 206) for more tips on harvesting and storing rainwater.

Above all, use common sense. Often it will be obvious to you which water sources are relatively safe and which are not.

PRESERVING

Once you have collected and treated water, it should be stored in food-safe plastic or glass containers. As mentioned above, when scavenging storage containers, be sure to avoid anything that may have come in contact with chemical contaminants. Store water in a cool, dry, and dark place. Adding 8 drops of bleach, if available, per gallon of water will lengthen the shelf life of stored water by discouraging mold and other bacteria from growing.

Another important component to preserving water supplies is something preppers and survivalists call “water discipline”—a crucial practice whenever you have a limited supply. Avoid dry, salty, or starchy foods as they require more water to digest. Do not consume coffee or alcohol. Do not smoke.

In extreme rationing situations, do not eat at all. Keep cool, and move as little as possible. Breathe through your nose and avoid talking. Plan your movements carefully, and plot a course of action for finding water rather than wandering aimlessly.

If you find yourself in a state of severe dehydration and manage to get water or some other drinkable liquid, do not gulp it. This will only make you hurl. Take small sips and hold them in your mouth before swallowing until you start to feel better, then take in larger amounts.

Fire

The lot of pre-historic man’s life was made a mite better by discovering fire and learning to cook food. Fast-forward 400,000 years (pre-zpoc), and many of us enjoy the shining modern convenience of stoves and ovens that put precision cooking at our fingertips. Technology! Advancement! But many of us would look a lot like our pre-historic ancestors, scratching our heads and making “huh!?!?” noises, were we tasked with building a fire sans modern conveniences like, say, a lighter.

While fire will be a solid player in your apocalyptic cooking roster (see Apocalyptic Cooking Methods, page 41), the usefulness of the skills in this section go way beyond cooking. You may find yourself shivering in the cold or with a pile of exterminated undead you need to get rid of. You should learn and practice fire-making skills until you are able to build a fire in any situation while wandering the wasteland.

Don’t underestimate the time and effort it takes to get a fire going. It’s not just a matter of carrying matches; you need to find an adequate place to build it, gather the needed supplies, and coax your flames into a self-sustaining fire. So be sure to plan ahead and begin making preparations for your fire well in advance of when you think you will actually need it.

SITE SELECTION

Indoors

There will be times, particularly during the chaos and danger of the initial outbreak, when you must build fires indoors without the use of a functioning fireplace. This flies in the face of all that we know about fire safety, but with a few considerations and some basic gear, it can be done with minimal risk.

Your main priorities will be to safely contain the flames and minimize (or eliminate) smoke. This is most easily accomplished using a clean-burning fuel, like the fuel tabs that come with most survival stoves, or denatured alcohol, as used in the bevy can burner (Building a Bevy Can Burner, page 242). A clean burn can also be achieved by using a highly efficient wood-burning stove like the rocket stove (Building a Rocket Stove, page 77). Even when using clean-burning fires with little smoke, always make sure you are in a well-ventilated space and keep the fire lit only so long as necessary for cooking.

Naturally, clear the area where you will be building your fire of any and all flammables—curtains, fabrics, furniture, books, etc. Always choose or prepare a surface to put your stove or other vessel onto; unless you have access to ceramic or sturdy tile or straight cement, try to find a sheet of metal or a cookie sheet to set up on. And always have a way to put the fire out near at hand—in most indoor spaces you should be able to find a fire extinguisher or at the very least earth from some potted plants.

Outdoors

If you are able to, choose the location for your fire carefully. Ideally it will be sheltered, away from main roads or other known geek thoroughfares.

Select a spot where there is an adequate clearing of at least 10–15 feet on all sides, where nearby or overhanging trees and brush won’t catch fire. Clear a patch of ground until you uncover bare earth. Again, have some way to extinguish the fire close at hand: a large pile of earth, or, if possible, a bucket or other container of water or sand.

PREPARATION

Once you have an adequate site, you’ll need three things to get the fire going: tinder, kindling, and fuel.

TINDER

Tinder is the highly flammable material that will be used to coax your fire to life. For emergencies, you should stock tinder in the form of cotton balls, ranger bands, and fuel tablets in your survival tin and BOB, but generally you should try to find tinder in your immediate environment. Tinder should be bone-dry. Bark and grasses, shredded paper, dryer lint, cotton balls, even tampons will work—be sure to keep an eye out and collect good tinder materials whenever you come across them; store them in a waterproof bag in your bug-out bag. The fine materials that make up your tinder should be loosely balled up for ignition.

KINDLING

Kindling is the first bit of “food” your fire will ingest after successfully latching on to the tinder. It should be made up of slightly larger and sturdier materials than tinder: small sticks, feather sticks (think thinly shaving a piece of wood to create a cluster of thin curls, like string cheese), rolled up paper, or strips of cardboard.

FUEL

Fuel is the material or materials on which your fire will sustain itself. Your best choices here are large pieces of wood; the size and quantity you need depend on how long you intend to let the fire burn.

When building a fire outdoors, try to collect hardwoods (maple, hickory, beech, and oak), as they burn better than soft-woods, give off good heat, and are good for cooking. Resinous softwoods like cedar, alder, hemlock, spruce, fir, pine, and juniper tend to spark and burn more quickly and will give your food an awful, rotten flavor. Look for wood that is decidedly dead and dry, avoiding fresh or “green” wood because it will produce a lot of smoke and burn poorly. Other items in the wild, like dry grasses and leaves, dried animal dung, and animal fat will work as fuel as well.

When building a fire indoors, remember that many pieces of furniture are covered with paints, varnishes, or other finishes that will give off noxious gases. You can also burn books (even this book could be used for fuel in a life-or-death situation!) and other paper sources.

TIP: In addition to the wood you need to build your fire, be sure to have a good supply on hand to maintain it once it gets going.

ARCHITECTURE FOR WOOD-BASED FIRES

Once you have selected your site and collected your supplies, you are ready to consider the architecture of your fire. Here are four types of fire that should cover most of your needs when on the move:

1. Underground Fires: For Concealment

This fire type is useful for concealing your presence from potentially nosy undead neighbors or wandering hordes. The Dakota Fire Hole (pictured on the next page) is an easy method for a quick underground cooking fire. Dig a small hole, about 2–3 feet wide and 1–2 feet deep. Then dig a small connecting tunnel that ends about a foot away from the main hole. This will provide oxygen to your fire, so position the tunnel opening in the direction from which the wind is blowing. In the original hole, use wood to build a small teepee or log cabin structure.

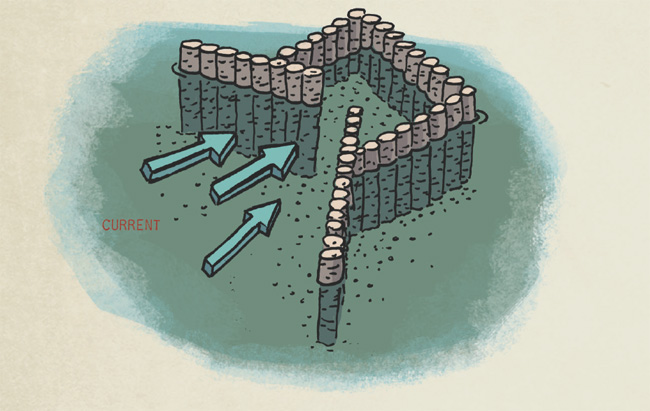

DAKOTA FIRE HOLE

2. Hunter’s Fire: For Quick & Easy Cooking

This fire (pictured) is simple and easy to set up, ideal for a quick meal on the run. Find two large bulky logs, and build your fire with tinder, kindling, and fuel between them. The larger logs provide a platform that allows you to rest your cooking pot or pan over the fire without your vessel directly touching the flames.

HUNTER’S FIRE

3. Multiple Fire Pit or Trench: For Semipermanent Dwellings

This fire architecture is ideal for large groups and longer-term camps. You can design a multi-fire pit in any configuration you like. A simple but versatile design features a 6- to 8-inch-long trench in the earth, with a circular 6-inch pit at one end. Line the outside of the trench and circular pit with rocks. The circular pit could serve as a home for a large main fire, good for cooking and providing heat. In the trench you can build several smaller fires, tending them as needed for different purposes. One could be dedicated to boiling water for cleaning and other general camp uses, while another could be kept in ember stage for baking and slower cooking.

If you have access to pots, you can build a wooden structure to hang them over the fire and use the paracord or snare wire from your BOB to hang them (see Bushcraft & Improvised Cooking Implements, page 272).

4. Star Fire: For the Axe-less Survivor

This fire is most useful when you want a long-burning easy-to-maintain fire but can’t find smaller sized logs or don’t have access to an axe. Set up 4 large logs in a cross formation (or 6 logs in a star formation), leaving enough empty space where the logs come together in the center for building a starter fire. Once the fire is self-sustaining, you can start to introduce the large logs by slowly pushing them into the fire—introducing them too quickly might suffocate the starter fire.

LIGHTING THE FIRE

Whether you have decided to construct a small hunter’s fire or a large multi-fire pit, the trickiest and most crucial part of a wood-based fire will undoubtedly be in lighting it. Gather needed supplies and method(s) of extinguishing so they are close at hand.

Ignite your tinder. Once the tinder is lit, begin the delicate process of adding kindling to ensure the flames become self-sustaining. In order to become self-sustaining, the nascent flames need the right balance of fuel and oxygen. If the kindling is too big or wet, or if you add too much kindling too quickly, the flames will be smothered. At the same time, if the tinder is too small or you add kindling too slowly, the flames will quickly die. Budding flames need to be coaxed. In inclement weather fail-safe supplies like ranger bands (bicycle tire inner tube) are especially helpful because they will burn even when wet. If your initial flames are giving off too much smoke, it could mean that they need more oxygen—don’t be afraid to blow on them. Watch your fire carefully until it is self-sustaining and burning well.

TIP: It is easier to keep a fire going than to start a new one. If you have the luxury of being in one place for an extended period, keep your fire going by having a good supply of fuel wood at the ready.

SCAVENGING SUPPLIES

Scavenging

The survival tin and bug-out bag are great for basic preparedness but can only carry so much, making scavenging another mainstay in the zpoc survivor’s skill set. The one maxim I will put forth for scavenging: reject your first idea on everything. For example, if you’re hanging around your home during the initial outbreak and wondering where you might be able to find some canned tuna, don’t consider for a second hitting up the corner store or your local grocery store. Wal-Mart? Never. Not only are those the kind of places everyone else will have tried, leaving nothing left, but the zeds will be happily feasting on an hors d’oeuvre platter of stupidity and you’ll be the cherry on top.

Or perhaps you’re doing some casual browsing while Living Off the (Waste) Land (page 237), or setting up (aka, “digging in”) your Long-Haul Bug-Out Location (page 306) and need to make a dedicated supply run to your closest population center. Bypass the obvious, and think outside the box for alternatives, like office lunchrooms, elementary schools, and abandoned houses.

Following are some guidelines for making scavenging safe and effective.

SUPPLIES

When scavenging in the wasteland, a few basic supplies are extremely useful:

Bags for lugging your loot: duffle, backpack, plastic bag

Bags for lugging your loot: duffle, backpack, plastic bag

Standard B&E fare: lockpick kit with tension wrenches, bolt cutters, crowbar

Standard B&E fare: lockpick kit with tension wrenches, bolt cutters, crowbar

Spray paint for path marking (e.g., “Dead Inside” or “Area Cleared”)

Spray paint for path marking (e.g., “Dead Inside” or “Area Cleared”)

Paper and pencil for taking inventory of any items you’d like to return for

Paper and pencil for taking inventory of any items you’d like to return for

Protective gear for keeping your tender human flesh bite free: gloves, boots, helmet, face mask, etc.

Protective gear for keeping your tender human flesh bite free: gloves, boots, helmet, face mask, etc.

Food and water for sustenance

Food and water for sustenance

Survival tin or basic survival items in case you are detained or on a multi-day trip: matches/flint, mess kit, etc.

Survival tin or basic survival items in case you are detained or on a multi-day trip: matches/flint, mess kit, etc.

TARGETS

Here are short lists of places to avoid and to target:

Places to Generally Avoid (Unless Necessary)

Convenience stores

Convenience stores

Gas stations

Gas stations

Grocery stores

Grocery stores

Hospitals

Hospitals

Pharmacies

Pharmacies

Gun stores

Gun stores

Police stations

Police stations

Camping or military surplus suppliers

Camping or military surplus suppliers

Department and big-box stores like Walmart, Costco, etc.

Department and big-box stores like Walmart, Costco, etc.

Places to Seek Out

FOR WEAPONS & SUPPLIES

Abandoned vehicles, especially police cars, fire trucks, and EMTs

Abandoned vehicles, especially police cars, fire trucks, and EMTs

Hardware stores

Hardware stores

Private medical clinics, doctors’ offices

Private medical clinics, doctors’ offices

Pet shops or veterinary hospitals

Pet shops or veterinary hospitals

Libraries

Libraries

Office towers

Office towers

Jails

Jails

FOR FOOD

Restaurants

Restaurants

Schools

Schools

Private residences

Private residences

Office towers

Office towers

Jails

Jails

PLAN OF ATTACK

Having some form of plan when scavenging an area will make your efforts effective and efficient. Here are a few tips:

Only scavenge during daylight hours.

Only scavenge during daylight hours.

Break down the immediate area into sectors or quadrants (e.g., northeast, etc.), and decide which areas you will tackle in what order. Scale could be as large as a city or as small as a block.

Break down the immediate area into sectors or quadrants (e.g., northeast, etc.), and decide which areas you will tackle in what order. Scale could be as large as a city or as small as a block.

Avoid going solo. In larger groups, break into 2- to 3-person teams, then decide who will cover which area, who will be lookout, time frame, etc.

Avoid going solo. In larger groups, break into 2- to 3-person teams, then decide who will cover which area, who will be lookout, time frame, etc.

For large areas, send scouts ahead of your main party to survey the locale and possible target locations before proceeding.

For large areas, send scouts ahead of your main party to survey the locale and possible target locations before proceeding.

Observe each building or structure before entering to avoid surprises: How many entrances/exits are there, do there appear to be signs of life? Un-life?

Observe each building or structure before entering to avoid surprises: How many entrances/exits are there, do there appear to be signs of life? Un-life?

ONCE INSIDE

You’ve scouted a location and taken stock of entrances/exits and any obvious zed activity. If the location is secured, you’ve used the lockpick kit, bolt cutters, crowbar, or good old-fashioned elbow grease to gain entrance. Now what?

If you are in a group, work in teams of 2 to 3. Once inside a building, secure an area (entire floors in larger buildings or the whole building for houses and other smaller locations) before searching it—make sure there are no zeds or other survivors hiding or lurking. Be quiet and attract as little attention as possible.

If you uncover a glut of biters that seems even remotely overwhelming, clear out. Leave entrances and exits open so they can trickle out and you can pick them off from a distance (if you have a firearm) or revisit the site at a later time. Drop any bags or items if you need to move quickly—they will only slow you down.

When searching locations, be thorough: Check drawers, under mattresses, under furniture, in closets, bathroom cabinets, in garages, in sheds, etc. Having a pen and paper will allow you to note locations and items you want to come back for if the item’s size or available bag space is a constraint.

Look at most everything with new eyes—there are potential secondary uses for most things. You can always use empty soda bottles or other plastic containers for growing food (see Container Growing, page 145), or steel drums could be used to make a hobo stove (see Apocalyptic Cooking Methods, page 41). The wire from picture frames could be used for making snares (see Tracking, Hunting, & Trapping, page 25) and coffee tins or soup cans could be used to make a rocket stove (Building a Rocket Stove, page 77), for example.

GETTING OUT

Mark all searched locations with spray paint or some other marker for future reference; tags (like, say, “Carl Was Here,” “Dead Inside,” or “Area Cleared”) could also potentially help other survivors passing through.

RECOMMENDED READING: For more on a variety of tactical missions and general zpoc survival, check out Surviving the Zombie Outbreak: The Official Zombie Survival Field Manual by Gerald Kielpinski and Brian Gleisberg.

Foraging

Did you know there are over 200 wild edibles in North America alone? Most people walk by wild edibles every day—growing out of cracks in the sidewalk or popping up as “weeds” in your garden—without ever knowing it. Once conventional food systems are wiped out, forageables can become a cornerstone of your diet and possibly your only source for fresh food.

THE UNIVERSAL EDIBILITY TEST

Several of the most common and accessible edible wild foods across North America are identified and discussed throughout this book (see Urban Hunting & Foraging, page 99; Into the Wild, page 251; and The Long Haul, page 303, for more details), but what are hungry survivors to do if they can’t find these species in their friendly neighborhood green space or while wandering around in the forest?

This approach to the Universal Edibility Test, as adapted from the SAS Survival Guide by John “Lofty” Wiseman, is a way to test any wild edible for safety. Although it takes about 16 hours to know definitively if a plant is safe, it is a reliable way of ensuring that a wild food is edible in the absence of identification guides. Be sure to have an empty stomach before beginning and test each part of the plant (flower, leaves, fruit, roots, etc.) separately.

Bruise the specimen slightly then hold it on the inside of your elbow for 15 minutes.

Bruise the specimen slightly then hold it on the inside of your elbow for 15 minutes.

If no skin reaction occurs, touch a small piece to your lips for 5 minutes.

If no skin reaction occurs, touch a small piece to your lips for 5 minutes.

If no reaction or burning sensation develops, hold a piece on your tongue for about 3 minutes.

If no reaction or burning sensation develops, hold a piece on your tongue for about 3 minutes.

Next, chew the specimen and hold it in your mouth for 15 minutes without swallowing (spit instead). If at this point there is no burning, stinging, or otherwise negative reaction, swallow and wait for 8 hours.

Next, chew the specimen and hold it in your mouth for 15 minutes without swallowing (spit instead). If at this point there is no burning, stinging, or otherwise negative reaction, swallow and wait for 8 hours.

If no vomiting or diarrhea develops, eat a handful of the specimen and wait another 8 hours. If no symptoms develop during this time, it is safe to eat!

If no vomiting or diarrhea develops, eat a handful of the specimen and wait another 8 hours. If no symptoms develop during this time, it is safe to eat!

This test does not apply to fungi. See A Note about Mushrooms (opposite) for more information on zpoc mushroom hunting.

GENERAL FORAGING TIPS

“Wildman” Steve Brill, environmental educator and author of Identifying and Harvesting Edible and Medicinal Plants in Wild (and Not So Wild) Places, offers these tips:

Pick plants in areas where they are thriving; it will be easier to collect a good quantity and you are putting less strain on the stand of plants.

Pick plants in areas where they are thriving; it will be easier to collect a good quantity and you are putting less strain on the stand of plants.

Take no more than 10% of any particular stand, and do not collect more than you think you will use.

Take no more than 10% of any particular stand, and do not collect more than you think you will use.

Don’t uproot a whole plant if you only need the leaves! Collect only the parts you are going to use so the plant can regenerate.

Don’t uproot a whole plant if you only need the leaves! Collect only the parts you are going to use so the plant can regenerate.

Put each species in a different plastic bag or container, especially when dealing with new and untested species.

Put each species in a different plastic bag or container, especially when dealing with new and untested species.

RECOMMENDED READING: For more on foraging for wild foods in North America, also check out Edible Wild Plants: A North American Field Guide to Over 200 Natural Foods by Thomas Elias and Peter Dykeman.

Tracking, Hunting, & Trapping

The vast majority of us have never once killed an animal for food. Such is the way of modern convenience—the meat we buy all pink and packaged from the grocery store is so far removed from the animal it came from that virtually all intimacy between our carnivorous appetites and the furry creatures that feed them is lost.

Come the rotters revolution, that will inescapably change. Survivors will almost certainly be forced to return to some form of hunting for food. As Nathan Martinez, author of Subsistence: A Guide for the Modern Hunter Gatherer points out, if you want to really live off the land, you can’t be squeamish.

ETHICS

While many would argue that the ethics of hunting (and ethics in general, really) went out the door with the undead masses, there are some general guidelines to keep in mind, particularly as you become more proficient at hunting:

Unless you are desperate for food or have no control when trapping, pass up obviously young animals, or at least wait until the fall when most young have had a chance to mature enough to leave their mothers. Sparing young animals is a good way to help support healthy population levels and future population growth.

Unless you are desperate for food or have no control when trapping, pass up obviously young animals, or at least wait until the fall when most young have had a chance to mature enough to leave their mothers. Sparing young animals is a good way to help support healthy population levels and future population growth.

Give animals a fair and sporting chance—that is, a fair chance at escape. While this piece of advice might seem more applicable to pre-zpoc sport hunting, unless you are starving it’s not cool to just kill an animal in its den or by exploiting some other unfair advantage.

Give animals a fair and sporting chance—that is, a fair chance at escape. While this piece of advice might seem more applicable to pre-zpoc sport hunting, unless you are starving it’s not cool to just kill an animal in its den or by exploiting some other unfair advantage.

As you become more proficient at hunting with a weapon (firearm, slingshot, bow, etc.), do your best to find a clear shot to vital areas (chest or head). This is a more humane way of hunting because it will minimize the amount of suffering the animal experiences before it dies.

As you become more proficient at hunting with a weapon (firearm, slingshot, bow, etc.), do your best to find a clear shot to vital areas (chest or head). This is a more humane way of hunting because it will minimize the amount of suffering the animal experiences before it dies.

TRACKING

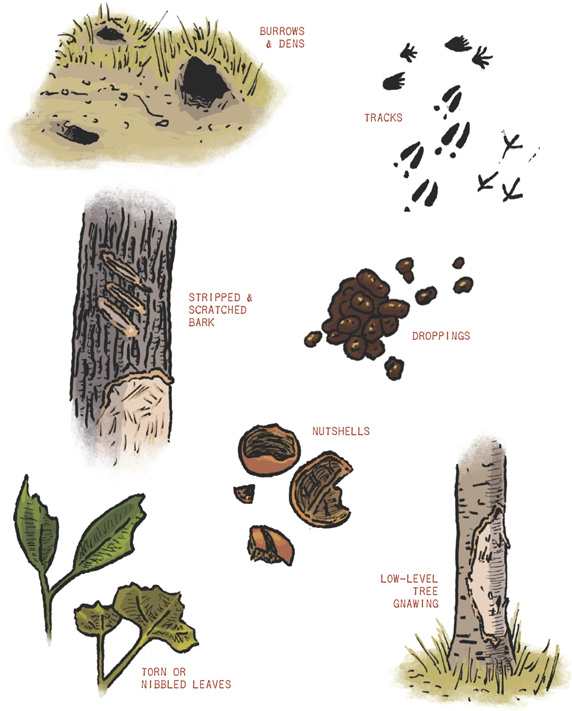

Whether hunting, trapping, or using snares—before you bag anything, you will need to track it. This will require a keen eye and picking up subtle details in the natural landscape that you probably never noticed pre-The End of the World As We Know It (TEOTWAWKI).

SIGNS OF WILDLIFE

The majority of non-nocturnal animals are most active in the first and last hours of sunlight, when they are traveling from or to their dens and nests or visiting water and food sources. These are good times to hunt, particularly if you’ve located a den or nest that you can plant yourself at (see Planting, on page 28), or at the very least good times to observe animals and their habits.

Yes, most wild animals are creatures of habit, using the same paths to and from food/water day after day. In hunter lingo a “trail” is a well-worn path used by several species, whereas a “run” is a less-used path, typically used by only one species or even one particular animal. If you can find a well-worn trail or a run that appears to be in regular use, you’ve happened upon a wealth of information and a good place to employ snares and traps. How do you find them? Most animals will live reasonably close to a water supply, so that is a good place to start.

HUNTING WITH A WEAPON

Whether using a firearm, slingshot, cross-bow, or even a simple spear, hunting with a weapon is the most common way of hunting for sport and/or sustenance pre-zpoc.

When actively pursuing an animal you need to be:

1. UNRECOGNIZABLE

The human form, face, and hands are extremely recognizable to wild animals. Cover up with a handkerchief, gloves, or any other breathable fabrics you can scavenge!

2. EXTREMELY QUIET

Because most animals have keen hearing, especially for sounds of movement at close range, you must learn how to move extremely slowly and quietly. Take advantage of “sound camouflage” whenever you can—wind, rusting leaves, etc.

3. DOWNWIND

Another keen sense for most wild animals is smell—and to most wild animals humans reek (and I am talking the living variety, let alone the rotters). Always stay downwind of your prey and mask your scent by saturating your clothing with smoke from a smoky fire.

Speaking of senses, generally two of three—scent, sight, and hearing—will be strong in any given animal. You can gain clues as to which senses an animal relies on most by simply looking at them—the larger the nose, ears, or eyes relative to the animal’s other features, the more the animal relies on that particular sense.

There are 3 general strategies for hunting, each of which has its advantages and disadvantages, depending on the type of prey:

PLANTING

Planting is just what it sounds like—planting yourself in one spot and waiting for your prey to come to you. It’s especially effective when you know where your prey dens and for animals that are notoriously skittish, like squirrels and woodchucks.

STALKING

Stalking is actively (and stealthily!) following your prey until you have a clear and potentially deadly shot. Moving slowly and silently, and knowing when to move, is a set of skills that will take time and practice to master, but stalking is an effective method for hunting deer, moose, and elk, among other prey.

FLUSHING & DRIVING

Many animals can be rustled up by walking through an area and “flushing” or “driving” them out of hiding. This is most effective when done in pairs or a small group, where one person can flush while the other shoots—though it does require coordination and a plan so that no (still living) human gets shot. It’s often used for raccoons, opossum, rabbits, and woodland birds like pheasants and grouse.

HUNTING WITHOUT A WEAPON: SNARES & TRAPPING

Hunting with a weapon is great if you can use a weapon; for the inexperienced zpoc hunter, well-placed snares and traps have more potential for success and can be much more valuable. And really, the more methods for bagging animals you employ—using hunting, trapping, and snares—the more successful you will be in getting food into your craw. Added bonus: you can be bagging dinner while otherwise avoiding pesky woodland walkers.

All components for a trap or snare should be constructed well away from the area you plan to use it—this will cause less disturbance to the vegetation in an area, which animals are keenly perceptive of. Don’t use freshly cut wood for traps or snares—the “bleeding” sap is an alarm bell to wild animals. In addition, avoid transferring your scent to snares and traps by wearing gloves. You can also attempt to remove your scent by passing wire or nonflammable traps through flames to burn it off or mask your scent with urine (from previous kills, not human), mud, or strong-smelling food.

The Basics

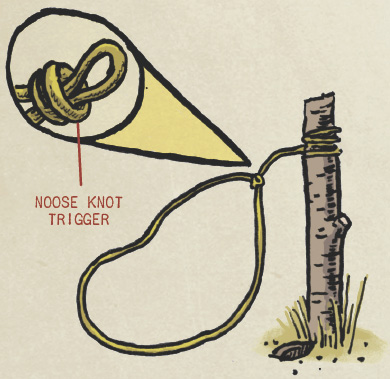

The three key components in any snare or trap are the trigger, power source, and bait.

TRIGGERS

The heart of any trap or snare is the trigger—what puts the snare or trap into action. They are most often carved from wood.

POWER SOURCES

The power source is what causes the snare or trap to entangle, trap, or kill your prey—often it is merely the struggling action of the prey itself, sometimes coupled with gravity. Bent saplings (providing a spring for spring snares) and heavy rocks or logs (providing deadly blows for deadfalls) are also common power sources.

BAIT

Bait is what attracts the animal to your snare or trap, highly increasing your chances of a catch.

Bait must be both something the animal is familiar with and something that’s not readily available to it. If your prey is carnivorous, meat (from previous catch—entrails are generally good) is an excellent choice. For vegetarians, seeds, berries, and other fruits or vegetables that grow in the area are good options. Scatter some of the bait around the trap to allow the animal to sample and develop a craving for it, with the hopes of guiding it into the trap.

Simple Snare & Traps

There are literally hundreds of snare and trap designs, all of which—according to Lofty Wiseman, author of SAS Survival Guide—can be grouped into “mangle” (deadfalls), “strangle” (noose snares), or “dangle” (spring snares). Many of the wide variety of snares are very specific to particular animals and therefore more difficult (and sometimes more effective) than the simple snare and trap examples detailed in this chapter.

RECOMMENDED READING: For advanced snare and trap building, check out The Trapper’s Bible: Traps, Snares, and Pathguards by Dale Martin.

BASIC NOOSE SNARE

A basic noose snare (pictured) falls under the “strangle” category mentioned above. Simple noose snares are made from a length of wire fitted with a noose knot at one end (the trigger). The opposite end of the wire is threaded through the open end of the knot and attached to a stake, forming a loop that should be set to a size and height appropriate for the intended prey. Once the prey walks into the snare and the loop is around its neck, the animal’s own struggle will act as the power source, tightening the noose and trapping it.

BASIC NOOSE SNARE

Most often you will need to attach the snare loop to a stake, adjusted to neck height of the intended prey. Brass snare wire is a good material to use, though other sturdy wires (from a picture frame, for example) could be scavenged as needed. A thin rope or paracord could also be used, though these materials will require you to prop the noose open with additional string or small sticks. This snare is often put in front of burrow openings and works well for small game like rabbits, squirrels, and woodland game.

This snare does not naturally lend itself to baiting. However, you can prop up some bait on a stick so that it is in the middle of the circle created by the snare—though the animal might be able to grab it without passing through the noose. This trap may or may not kill the animal and your snares should be checked often—to avoid either losing your lunch to enterprising poachers or undue suffering for the animal.

BASIC BOX TRAP

A basic box trap (pictured) is a small- to medium-sized box, usually constructed from wood, that lures prey inside with bait. Once the animal makes contact with the trigger set in the back half of the box, a sliding door at the front of the box is released, trapping the animal inside. The box trap is effective for small- to medium-sized game such as rabbit, squirrel, raccoon, etc.

The entire trap—box, door, and trigger—can be made from scavenged wood pieces or sturdy sticks and logs found in the wild. A simple notched peg trigger (as seen here) can be carved from wood. The trigger, in conjunction with a wooden pivot, keeps the door raised. Be sure that the peg trigger fits very loosely in its hole and the notch faces the front of the trap so that it is dislodged when the animal passes within. The exact dimensions aren’t entirely important, as long as it will accommodate the types of game you wish to catch—if it is too big, smaller prey will be able to get past the trigger without hitting it. It is also useful to leave the back end open and cover it securely with mesh or some other screen, as animals are much more likely to enter if they can see through the other end.

BASIC BOX TRAP

A good general strategy for using any box trap is to let it stand open with bait scattered around and inside at the back of the box so that animals can become used to eating from them. After a few days you can rig the trap. This trap will catch, but not kill, the prey.

Fishing

I am convinced that fish is the best source of edible

wild food in North America for the person in a survival

crisis. Freshwater lakes and ponds, streams, creeks

and rivers are abundant food reservoirs.

Chances are the thought of fishing during the rotters revolt won’t conjure images of quiet waters and lazy afternoons in a canoe, beer firmly in coozy and bucket full o’ the day’s catch. No, much like everything in the zpoc, survival fishing will be frantic, haphazard, and absolutely necessary.

But hey, that quote above from foremost survival expert J. Wayne Fears (what a name) is encouraging, right? For those uninitiated in the ways of the angler, the act of fishing is pretty straightforward—line goes on pole, hook goes on line, bait goes on hook, then off you go! That is, of course, an oversimplification, but if you stop reading here you will at least have a general idea of how to cobble together the survival fishing gear in your savory survival tin and BOB.

Chances are, most of your fishing will be done in freshwater. (Check out Wild Game Hunting during an Undead Uprising (page 255) for a short guide to different North American “panfish” species, where to find them, and how to catch them.) If you are near a coast or choose Maine for your Long-Haul Bug-Out Location (page 306), there are wonderful eats to be had from salt water—shellfish and ocean fish like porgies, black sea bass, and ocean perch.

Fish have varying habits. Some prefer to feed in the early morning while others prefer a later afternoon nibble. Some feed higher up the water column while others stay in the deep dark depths (the big guys!). Generally, however, they all require patience to catch (there’s a reason that pre-zpoc countless hours were spent quietly bobbing along in a boat or sitting on a bank). They all like to swim under the radar—they like to hide and hang out around sunken logs, rocks, or other debris. And, for the most part, they will stay further down in cool waters during hot weather and closer to the surface in warmer water during cold weather.

Speaking of, there’s an added bonus to apocalyptic fishing versus hunting and trapping—it can be a source of food throughout the year. Ice fishing anyone?

GEAR

If you’ve got the survival fishing kit from your survival tin or (even better) bug-out bag, great. You are ready to start fishing. If you don’t, you can try to scavenge gear in a nearby town or city or try the substitutes offered in the primer here.

POLE

Fishing poles can be a pain in the behind when you’re running from the undead—they take up a lot of room and can easily break. Luckily, most survivalists would agree that a pole isn’t needed for a survival fishing kit because a pole is probably the easiest piece of equipment to substitute and scavenge—just grab a stick. That, along with the knot-tying skills outlined here (plus line and a hook, of course) are all you need.

LINE

Commercial fishing line comes in a wide variety of diameters, or “weights.” The “tested weight” of a fishing line refers to the weight of the fish it can handle. Generally, having a stronger fishing line than you think you’ll need is desirable, but smaller fish can become “spooked” by a strong, large-diameter fishing line, which would stand out as unusual to them. A 50- or 100-pound line should cover most of your fishing needs, and in a pinch could also be used to build snares or sew clothing. Waste-land substitutes: dental floss, heavy thread, thin wire, and sinew from large game.

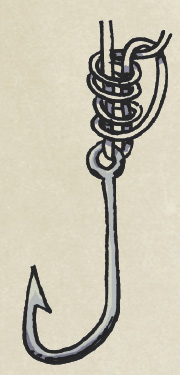

HOOKS

Hooks are what do the actual catching of your fish. Commercial hooks, which are designed specifically for fishing, are by far the easiest to use and most effective in hooking fish. Go for small as opposed to large hooks—small hooks can catch both small and large fish, whereas large hooks can only catch large fish. Small hooks have the added bonus of taking up a little less room. Wasteland substitutes: paper clips, soda can tabs, thorns, and carved bone.

SINKERS

Sinkers, or weights, are used to bring your hook further down in the water, where bottom dwellers like catfish like to hang out. The current in which you are fishing will dictate the amount of weight you use—the stronger and swifter the current, the heavier the weight you need. Sinkers are also helpful in casting your line a farther distance. Commercial sinkers have their advantages over scavenged options in that they are small and dense—you get more bang for your buck without distracting the fish. Wasteland substitute: rocks.

BAIT & LURES

Bait and lures are used to attract the fish to your hook. Bait can be real (insects, fish guts, fruit, etc.) or artificial (often plastic), while lures are typically artificial and have hooks built into them. Generally lures (and sometimes bait) use color and flashiness to attract predatory fish by tricking them into thinking the lure is a live lunch. When scavenging for bait or lures, grab whatever you can find and work through trial and error. For bait, worms, fish entrails, dragonflies, and small minnows are good options. Bright fabric strips or flashy metallic pieces of streamer make good substitutes for commercial lures.

LINE FISHING

If you’ve got a reasonably quiet afternoon on your hands, in terms of biter activity, you can hang out and actually fish if you like. Pictured are two angling-appropriate knots: the Grinner knot, for attaching your hook to the line, and the Fisherman’s Bend knot, for attaching your line to a pole. While fishing, be sure to stay back from the edge of the water—nearby fish can see further up on to the shore than you think.

Most of the time, though, you’ll be busy with other important survival tasks, such as popping brain cherries and foraging, and will want to rig up some setlines or night lines to catch fish without your involvement.

GRINNER KNOT

FISHERMAN’S

BEND KNOT

SETLINES

The term “setline” refers to a stationary pole/stick with line, a hook, lure/bait, and weight (if needed) planted firmly in the bank and then left—just set it and forget it. (Actually, you should check your lines frequently and reset as needed.) Just be sure to set your pole far enough back that it’s in solid ground and will stay put.

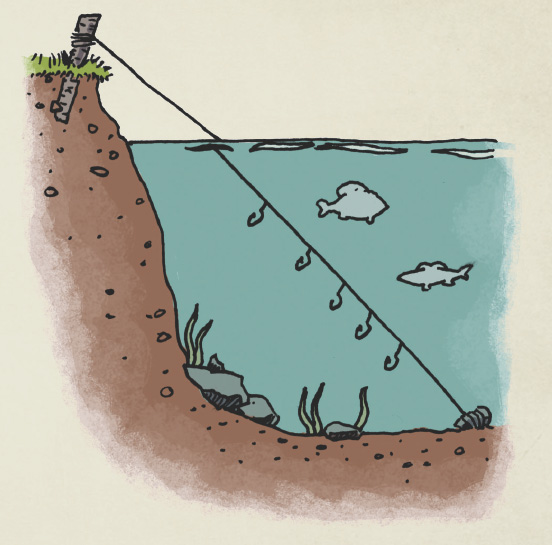

NIGHT LINES

A night line (pictured) is a type of setline. It gets its name because it is often set at night and checked in the morning. While different people will set a night line in different ways, the general idea involves a length of heavy line (say 50–100 lb.), onto which several short lines (“drop lines”) with baited hooks are attached. Small knots are used to secure the drop lines in place so they cannot slide down the main line, and a solid weight (a rock works great) is added at the main line’s end. The finished line should be attached to a pole using a Fisherman’s Bend and planted firmly into the bank. Cast the line by tossing out the weight to the desired distance and leave it largely unattended.

NIGHT LINE

In this case using a stinky bait (viscera from previous catches, for example) is a good choice because the strong smell is broadcast in the water and can attract fish from farther away. However, experiment with several different kinds of baits and tailor based on your experience.

AN ALTERNATIVE TO LINE FISHING: TRAPS

Just as there are many ways to skin a cat (no thanks, even during the zpoc), there are several ways to trap a fish. The design of fish traps can vary widely, but the general idea is to funnel fish into a semi-enclosed area (which, frankly, they are too dumb to escape from).

A simple trap (pictured on the next page) can be constructed in shallow waters by driving wood stakes into the ground very tightly together to create a pen with three sides—(the stakes should be longer than the water is deep), and the open end of the pen should face down current. Then, drive more stakes to create a V-shaped funnel that points into the opening of the pen (obviously leave the bottom of the V open to allow the fish entry to the pen).

Fill in any gaps that might be left in the open end of the pen, or angle your V so that it closes off the pen. Once you’ve caught your fish in the trap, you can use a spear to nab them.

HUMANE HANDLING OF FISH

Once you’ve caught a fish, the most humane way of dispatching it is giving it a sharp bonk on the brain (behind the eyes) or inserting a knife into that same spot. Leaving them to suffocate out of water isn’t all that nice and the undue stress will affect the quality of the meat.

Basic Field Dressing & Butchery

During the initial stages of the zombie apocalypse, most of your hunting will likely be for small- to medium-sized game and fish that will often be cooked whole or with minimal breaking down—for simplicity’s and time’s sake. In technical terms, this means little actual butchery and mostly “field dressing,” that is, removing an animal’s extremities, skin, and innards. Even if you bag larger game, you will have little time, desire, or need for specialized butchery or particular cuts of meat. Therefore, the following section focuses on basic skills—exsanguinating (bleeding out), skinning/plucking/scaling, evisceration, and basic butchery.

Be sure to practice basic hygiene: Clean hands with hot water, heated over your campfire or stove, and of course use soap if it’s available (see Keeping Clean in the Apocalypse Kitchen, page 48, for natural soap substitutes). Sterilize all tools you will be using in boiling water and have them close at hand while working. Also, before beginning, make sure the blades you will be using are very sharp. A crock-stick sharpener (pictured) is small, portable, and a good addition to the BOB.

Always dress animals several hundred yards away from well-used trails and runs as well as from where you will be sleeping. The inevitable mess will scare off the animals who use the trails or attract unwanted attention of both the wild and undead variety to your camp.

USEFUL TOOLS

In addition to the general-use hunting and survival knives in your Flee with Flavor Bug-Out Bag page 5, there are several specialized tools useful in the cleaning and butchering of game. Collect and carry as many as you can!

Boning knife

Boning knife

Butcher knife

Butcher knife

Cleaver

Cleaver

Fillet knife

Fillet knife

Meat or carpenter saw

Meat or carpenter saw

Paracord or heavy rope for hanging large game

Paracord or heavy rope for hanging large game

Paring knife

Paring knife

Plastic bags for meat and offal (preferably heavy-duty resealable freezer bags from your BOB) if not consuming right away

Plastic bags for meat and offal (preferably heavy-duty resealable freezer bags from your BOB) if not consuming right away

Knife sharpener

Knife sharpener

String or elastic bands for evisceration

String or elastic bands for evisceration

RECOMMENDED READING: For more on knife sharpening and maintenance, check out The Complete Guide to Sharpening by Leonard Lee, and The Razor Edge Book of Sharpening by John Juranitch.

BLEEDING OUT

Once an animal has been killed (see Humane Killing during the Zpoc, page 31), you should make haste to slit the throat or, preferably, sever the head and suspend the animal upside down so that the last few pumps of its heart will help drain the blood from the body.

You can bleed out any fish, though many would argue it’s not needed for small panfish. A fish can be bled out by severing the major arteries (dorsal and ventral) that terminate in the gill/head area. Lift up the gill latch and make a sharp vertical cut upward almost to the top of the head—the heart will continue to beat for several minutes after the fish is dead, helping expel the blood.

SKINNING, PLUCKING, & SCALING

It is best to skin an animal soon after killing, while the body is still warm and the skin more easily removed. However, if you are not consuming the meat right away and cannot chill it outdoors or in a cold stream (temperatures at 40°F or cooler), wait until you are ready to cook the animal before skinning to protect the flesh from exposure to dirt and bacteria.

When skinning, always make an initial incision and then cut from the inside out—cutting from the outside in will get dirty fur onto the meat and possibly contaminate it. For small animals like squirrel, rabbit, or raccoon, remove the feet, tail (if applicable), and head. Make an incision under the skin at the belly, and, being careful not to puncture the flesh or organs underneath, cut all the way around the midsection like a belt. Grab the top end and peel it off like a shirt. Then grab the bottom end and peel it off like pants.

For larger animals like wild sheep and goat or deer, make a long vertical incision along the belly (again with caution, to avoid puncturing the flesh beneath), then branch the incision off to the legs as well. Peel the hide away, using light, quick strokes from a knife if needed. Removing the head, feet, and tail will generally be easier once the hide has been removed.

For birds, first pluck the feathers. The easiest way to do this is by “wet plucking”—submerging the bird in hot water (but not boiling, ideal temperature about 130°F) for nine alternating intervals of 30 seconds under water, 30 seconds out of water. Otherwise, you can carefully remove the feathers by “dry plucking”—a particularly good way of plucking for waterfowl, whose feathers are very water resistant. Use a quick, decisive plucking motion rather than a pulling one to avoid tearing the skin, and do one feather at a time if they are tough to remove. The time frame for dry plucking is more flexible, as it need not be done while the carcass is still warm. Once the feathers have been removed, cut off the feet and head.

For most fish, simply scale while leaving the skin on—aside from rubbery little buggers like eel or catfish, fish skin crisps up nicely when cooked. To scale small and pan-sized fish, snip or cut off the fins then dip the fish in cool water (scales are easier to remove when wet). Run a spoon, butter knife, or other blunt object along the skin from tail to head; the scales should come off relatively easily.

EVISCERATING & CLEANING

For small mammals like squirrel, rabbit, raccoon, or opossum, after the skin has been removed, make an incision the length of the underside from the groin to the front breastbone, being very careful to not cut any organs beneath. The best way to avoid puncturing internal organs is by making a small incision and, pointing the tip of your knife upward, (carefully) cutting toward you from the inside out. Then open the chest cavity and remove the entrails.

For larger animals like deer, it is useful to “tie off the bung” before eviscerating. This involves cutting a deep hole around the anus (male) or anus and vulva (female)—also known as the “bung”—and pulling the incised area out slightly to tie off the exposed intestinal tract. This will prevent it from leaking when you remove it. Then, to eviscerate, open up the body through a long vertical incision along the underside, again being careful not to puncture the organs. When cutting out the stomach, clasp it shut with your hand or tie it off with string to avoid spilling its contents. After the intestines are removed, clean out any remaining glandular tissue around the bung area. It might smell foul—be sure to clean your knife and hands before continuing to remove the head and feet.

For birds, lay the plucked bird on its back and make a horizontal incision just above the anus—be gentle and slow so as to avoid nicking any internal organs. Once you have an incision big enough to slip your fingers into, vertically pull apart the upper and lower parts of the bird until you have a hole big enough to fit your hand. Reach into the body cavity and remove all entrails carefully.

For game large and small, rinse the cavity out with cool, clean water after eviscerating. Set aside choice tidbits like the heart, liver, and kidneys (see The Offal Truth about the Zpoc, page 264, for more information). If any parts of the animal were badly damaged by trapping or shooting, cut these away.

For fish, start at the tail and run your knife up the belly, being careful not to slice the intestines as you go—a fairly shallow cut should do the trick. Open up the body cavity and remove the innards (set them aside for bait). Cut the anus out with a V-shaped incision, and remove the kidneys if you see them attached to the backbone. Rinse the entire fish in cool water—inside and out.

BASIC BUTCHERY

Most often it will be easiest to cook small to medium game and fish whole on a spit (see Bushcraft & Improvised Cooking Implements, page 272); however, you can break even these small creatures down into smaller parts if you wish—a good way to share what meager catches you make with fellow survivors.

Both large and small game can be “jointed out”—that is, their legs removed at the joint—and their midsections broken down. For many four-legged game animals, the front legs are independent of the rest of the skeleton (with the exception of squirrels, who, like us, have collarbones) and can be cut away fairly easily. The back legs are typically attached through a ball and socket joint—first spread the leg and use quick slicing strokes to work your knife down to the joint, then pop it and finish removing the leg.

Birds can be handled in much the same way, first removing the neck bone, then the legs, wings, and finally breasts if you wish (see Spit-Roasted Pheasant, page 261, for further instruction).

To fillet small- to medium-sized fish (under 5 lb.), first cut the head off. Then lay the fish on its side vertically, with the tail end pointing toward you. Slip your knife under the tail skin, angle it, and cut till you can feel the backbone. Now run your knife along the backbone toward the head end of the fish. Do the same on the other side. Repeat this same process again if you wish to remove the skin from the fillets. For larger fish, start at the head (do not cut it off) and make a vertical cut down to the backbone. Then use the head to hold the fish steady as you move down toward the tail.

RECOMMENDED READING: For a more comprehensive look at butchering a wide variety of game, check out John J. Mettler Jr.’s beginner’s butchery guide, Basic Butchering of Livestock & Game.

Apocalyptic Cooking Methods

Unfortunately, cooking over an open flame during the zombie apocalypse won’t offer quite the same charm or enjoyment that it did before it became a survival necessity (especially in the absence of s’mores). Live fire cookery poses a whole new set of challenges and requires an array of new skills that must be honed almost entirely through experimentation and experience. Cobbling together fire-based stove and oven hacks, learning how to work with flame and ember for consistent temperatures, accounting for differences in fuel sources, and avoiding giving away your location to passersby are just a few of the challenges that lay ahead.

TIP: When seeking out fuel for wood fires, steer clear of softwoods like pine or fir, as their smoke makes any foods it comes in direct contact with taste rancid, and avoid the chemically treated or finished woods often found in furniture.

PLAYING WITH FIRE: DIRECT VERSUS INDIRECT HEAT

The science and thermodynamics of cooking—it’s probably the last thing you want to think about when you’ve discovered that Brad has been hiding a bite from the rest of your group, turned into a zeke, and made a real mess of the camp kitchen. But a few basics will vastly improve your abilities as an apocalyptic cook.

In a zpoc setting, where the world has gone dark and most of your cooking will employ fire in some way, shape, or form, you have two main tools at your disposal: the flames themselves and embers that are created as fuel burns down in wood fires.

These tools can be used in two different forms of cooking: direct and indirect. Cooking over an open flame is a direct cooking method whereby the food is cooked via a process called conduction. The flame comes in direct contact with the food itself or when its heat is transferred to the food via a conductive medium like a pan or pot. Grilling and baking, in contrast, are indirect cooking methods—the food does not come in direct contact with the heat source. When grilling, the food is suspended above the heat source and cooked by the heat that radiates from it. When baking, the heat source transfers energy to air within an enclosed space, which then cooks the food via a process called convection.

Using flame and embers to produce consistent cooking temperatures is probably the biggest challenge in apocalyptic cooking (see Judging Temperature on page 47 for further guidance), and there will always be some degree of variability and unpredictability when working with a live fire or embers.

For direct cooking methods involving an open flame, changing the temperature could mean adjusting how much contact your food or cooking vessel has with the fire—adjusting the height of the food or vessel so that the flames are fully and constantly touching the bottom of your pan versus the occasional lick, for example. Temperature can also be controlled by changing the fierceness of the flame or by moving your pan on and off the flames as needed.

For indirect methods involving fire or embers, distance from the heat source and the intensity of the heat source can be tweaked to control temperature and cooking times: moving the heat source up or down as needed, increasing or decreasing the number of embers, or using hot and cold zones (as described in Hibachi Grill on page 46).

While developing a feel for cooking with live fire, the most common problem you are likely to face will be temperatures that are too high, burning the outside of food before properly cooking the interior. Because of the variability that goes along with live fire cookery, it will require your constant attention and tending to—never leave food or fire unattended!

The stove and oven alternatives described below are intended to be but simple aids on your journey to becoming a proficient apocalyptic cook, something that will only come through experience and experimentation. Tweak their basic designs, experiment with construction materials and fuel sources, figure out what works and what doesn’t, and craft your very own hacks. Excelsior!

STOVETOP HACKS

No electric stove? No problem. Add these direct heat hacks to your apocalyptic culinary repertoire to impress all your still-living friends and achieve that pre-zpoc stovetop-cooked taste.

CAMP OR EMERGENCY STOVE (ESSENTIAL BACKUP)

Camp or emergency stoves are compact foldable single burner stoves often used by lightweight backpackers and survivalists. They typically come with a small supply of solid fuel tablets, though many can be used with wood or some other fuel as well. While they can only accommodate small pots or a mess kit, because of their fuel versatility, ease of use, and portability, they are good items to have in your BOB as a backup cooking method.

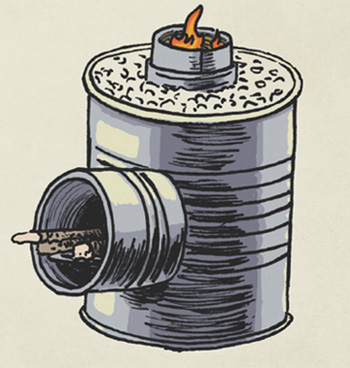

HOBO STOVE (EASY, REPLACEABLE)

A hobo stove is a simple makeshift stove that can be constructed out of a discarded tin can (tuna, cat food, soup, coffee, etc.) and can replace the emergency stove in your survivor cooking arsenal. To build one, poke small air holes around the top rim of the can, and a larger air hole close to the bottom (closed end) of the can. To use, put fuel into the can and light. Convection draws air in through the holes to help fuel the fire. This basic design can also be scaled up for larger containers like steel drums.

ROCKET STOVE (FOR INDOOR COOKING & HEATING)

Rocket stoves are extremely fuel efficient and, when properly constructed, produce very little smoke, making them good for indoor and outdoor use. The basic design can be scaled up or down in size depending on intended use and materials available. While you may be able to scavenge a pre-zpoc, pre-assembled rocket stove at camping and outdoor outfitters, you can build a small portable version with an unopened #10 can (think the large 6 lb. cans of coffee you might see in groceries or wholesalers like Costco), 4 standard-sized soup cans, and some insulation (perlite, vermiculite, damp sand, or earth). See Building a Rocket Stove (page 77) for complete instructions on assembly.

ROCKET STOVE

BEVY CAN BURNER (VERY SMALL & LIGHTWEIGHT, REPLACEABLE)

Bevy can burners, or soda can stoves, are a favorite among ultralight minimalist backpackers for their ease of construction and super light weight (about 1 oz.). They can be made from as little as two empty soda cans and provide high heat for quick (15 minute) cooking. With a simple addition, you can regulate oxygen intake and the rate at which the fuel burns to achieve a lower temperature that will burn for about 2 hours. Because they burn alcohol as fuel and produce no smoke, they are an excellent option for cooking indoors. Instructions for Building a Bevy Can Burner can be found on page 242.

BEVY CAN BURNER

WASHING BASIN FIRE PIT (SIMPLE, REPLACEABLE)

The internal metal basin from an obsolete washing machine makes for an excellent stovetop hack and wasteland fire pit—it will safely contain a fire for cooking while its perforated sides will provide ample oxygen to the fire and radiate heat for warmth. Support the whole setup with bricks.

OVEN HACKS

There are lots of ways to use indirect heat for baking in the absence of a proper oven. Preheat these hacks in your brain oven and get baking!

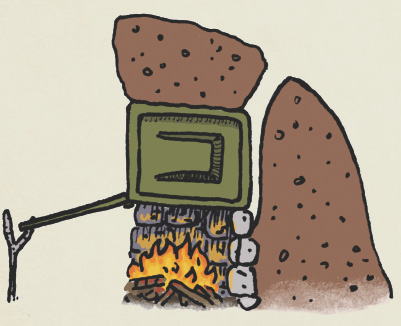

AMMO CAN OVEN (QUICK & EASY)

The ammo can oven (pictured) is a crude makeshift oven that was traditionally used by the military in survival situations. While the military-issue oven made use of “ammo cans”—the sturdy metal boxes used to store ammunition—you can build one using any metallic box with a lid and a live fire (just be sure the box wasn’t previously used for any really noxious purpose). Suspend the closed metal box containing the food you want to bake over a live fire, adjusting height as needed to achieve the desired temperature. You could also heap the container with embers, as with a Dutch oven (see below). Ideas for scavengeable metal containers: mailboxes, stripped-down electric ovens, and the bodies of charcoal grills (legs removed).

AMMO CAN OVEN

EARTH OVEN (QUICK & EASY, ALL NATURAL)

The mud oven’s little brother (see Hacks That Do Double Duty below), the earth oven (pictured) is a quick-and-dirty way of cooking food when no gear or scavengeable equipment is available. It requires only wood for a fire, rocks, vegetation, and earth; see Earth Oven (page 269) for instructions on building one. An excellent option for nomadic survivors out in the wild, the earth oven is best for moist indirect cooking applications like steaming.

EARTH OVEN

HACKS THAT DO DOUBLE DUTY

FIREPLACE (MAJOR BONUS)

While the undead moaning at your door and slowly weakening your makeshift defenses isn’t exactly conducive to a relaxing evening by the fire with a glass of whiskey, having a working fireplace when you are holed up is incredibly fortunate, especially during the initial outbreak when it will be dangerous to go outside. For stovetop functionality, find something to support pots and pans directly over the fire (think nonflammable), or to mimic oven cooking try an ammo can oven (opposite) or a Dutch oven (below).

DUTCH OVEN (EXCELLENT, NOT PORTABLE)

Dutch ovens are large heavy pots, typically made from cast iron and fitted with a lid. They are very versatile cooking vessels that I would insist you have with you at all times during the zpoc if they weren’t so damned heavy—but they are must-haves for a Well-Stocked Safe House (page 203) or Long-Haul Bug-Out Location (page 306). The cast iron that Dutch ovens are made from makes them excellent retainers and conductors of heat, useful for virtually any cooking or baking method—look for non-enameled fire- (and zpoc-) friendly versions. Park your Dutch oven over flames for general cooking. To use the Dutch oven for baking, preheat using embers: Set the vessel on a bed of embers in addition to using embers to cover the lid. Use the Hand Method (see Judging Temperature, opposite) to check the temperature before adding food. Once food is in the oven, only a thin layer of embers (both underneath and on the lid) is needed to maintain cooking temperatures and to help avoid scorching your grub. Remove all embers, being careful to avoid getting ash in your food, before removing the lid.

HIBACHI OR OTHER CHARCOAL GRILL (VERY ACCESSIBLE)

Ubiquitous little pre-zpoc relics, the infinitely useful charcoal grill offers a great way to cook or bake on the run in populated areas—even without charcoal. Grill with the top off for stovetop-like functionality, or keep the lid down for slower cooking and baking; create hot and cold zones by clearing certain sections of embers, and try keeping the food over the cold zone. The air vents on the lid and body of charcoal grills can be used to play with temperature when cooking with the lid down—all vents open will run a high temperature, whereas closing the lid vents will help maintain a medium heat.

MUD OVEN (EXCELLENT, NOT PORTABLE BUT REPLICABLE)

A mud oven (pictured) is a no-tech cooking tool perfect for those survivors who are bugging in with outdoor access or those setting up a location for the long haul. A simple mod can make it a great stovetop alternative as well; see Long-Haul Mud Oven (page 320) for instructions on building one.

MUD OVEN

JUDGING TEMPERATURE

Because the days of precision temperature dials and oven controls are gone, learning how to judge temperature in the absence of a thermometer will help you avoid countless burned breakfasts and blackened dinners.

There are a few no-tech ways of judging the temperature. The following are from fire cookery experts Sarah Huck and Jaimee Young, authors of Campfire Cookery.

1. Hand Method

This method is good for judging radiant heat sources like embers or a preheated pan. Hold your hand about 6 inches over the source and count how many seconds pass before you must take your hand away:

500°F: 1 second

450°F–500°F: 2–3 seconds

400°F–450°F: 3–4 seconds

350°F–400°F: 4–5 seconds

300°F–350°F: 5–6 seconds

250°F–300°F: 6–7 seconds

Use with: Hibachi Grill, Ammo Can Oven, Dutch Oven, Mud Oven

2. Eyeball the Embers Method

Useful for any cooking or baking method that employs embers, here you rely on assessing the look of your embers to estimate temperature:

500°F: Thin ash layer on the ember, bright red

400°F–450°F: Thicker ash layer, glowing red

350°F–400°F: Thick ash, slight glow

300°F–350°F: Solid ash, not glowing

Use with: Hibachi Grill, Ammo Can Oven, Dutch Oven

3. Live Fire Method

This is a good guide for adjusting the distance between your pot or pan and the flames to achieve a specific temperature. Scavenge some pot supports (see Heat Control & Pot Supports on page 44) or a whip up bush-craft pot rods (Bushcraft & Improvised Cooking Implements, page 272) and get cooking!

500°F: Flames fully touching the bottom of the vessel

450°F–500°F: Flames reaching the bottom of the vessel

400°F–450°F: Flames occasionally reaching the bottom of the vessel

350°F–400°F: Flames just below the vessel but not touching

300°F–350°F: Flames well below vessel

250°F–300°F: Flames are low

Use with: Emergency Stove, Hobo Stove, Ammo Can Oven, Hibachi Grill, Dutch Oven, Fireplace, Washing Basin Fire Pit

Keeping Clean in the Apocalypse Kitchen

Remember: Cleanliness is next to zombielessness (or something like that). What I mean is, keeping clean with undead body parts flying around (infected by virus, prion, fungal parasite, or otherwise)—not to mention the complete deterioration of society and all its perishable trappings—is important!

Here are some tips for keeping clean in your apocalyptic “kitchen” no matter where or when you find yourself in the zpoc.

GENERAL GOOD HYGIENE

Wash your hands! Especially after brain bashing! (If there is no soap available, there are alternatives; keep reading.) Also, wash dirty dishes right after using—they will be much easier to clean. And when all else fails, you can always sterilize tools, tongs, and what have you by putting them in good old boiling water for about 10 minutes.

WHEN BUGGING IN DURING THE INITIAL OUT BREAK

Maintaining food hygiene while bugging in is relatively easy. You should have cleaners already in your home, and once the dust settles a bit, you can scavenge from your less fortunate undead neighbors. Think bleach, borax, liquid dish or laundry soap, and powdered laundry detergent. They are all versatile choices for mixing up your own cleaners.

IN THE WELL-STOCKED SAFE HOUSE

When preparing a well-appointed safe house ahead of time, be sure to stock up on versatile cleaning agents that can form the base for several different types of cleaners:

BORAX (SODIUM BORATE)

Also known or marketed as sodium borate, borax can be used alone as a general purpose surface cleaner for its disinfecting and deodorizing properties or combined with water, a few drops of liquid soap, and baking soda for a DIY laundry detergent. It can also be used with vinegar as a good zed-fighting stain remover.

BAKING SODA (SODIUM BICARBONATE)

Aside from its usefulness in baking, baking soda is a mild alkali that can assist in dissolving dirt and grease in water. A simple paste made from water and baking soda can be used as a general cleaner, or baking soda can be combined with vinegar to form a scouring or scrubbing paste with some disinfectant power.

VINEGAR

The acetic properties of vinegar make it great for removing stains, mildew, and soap scum. Its antibacterial properties also make it a good disinfectant—a 5% solution can kill most common bacteria (don’t chance it with any zed germs, though).

RUBBING ALCOHOL (ISOPROPYL ALCOHOL)

A solution of water and rubbing alcohol (at a 1:4 ratio of alcohol to water) also has great disinfectant properties and doesn’t leave behind the smell that vinegar does. Plus, rubbing alcohol has a myriad of other uses: fuel for your Bevy Can Burner (page 242), relief of muscle pain (yup, that’s why it’s called rubbing alcohol), deodorant (yes!), and treatment of bug bites and ticks. Bonus: It’s also great for bartering.

HERBAL EXTRACTS

Many herbal extracts have disinfectant properties (and smell good to boot)—peppermint, eucalyptus, tea tree, yarrow, and pine to name a few. When combined with water, vinegar, and a little liquid soap (see DIY All-Purpose Disinfectant & Cleanser, above), these properties are enhanced to make a good all-around disinfectant cleaner.

IN THE WILD

Out in the wild you will have to depend on what nature gives you. Luckily, it turns out she gives lots of options, including:

WOOD ASH

Combine wood ash from your fire with water and (if the dirty dishes don’t have any already on them) a small amount of fat to make a thick paste. Apply this mixture to your dishes, leave for a few minutes, then scrub clean and rinse with clean potable water.

PINE OR FIR BRANCHES

Most coniferous needles have natural disinfectant properties (see Herbal Extracts on page 49). The branches of trees like pine and fir (pictured) can be used as au naturel brushes to scrub dirty dishes with makeshift ash soap.

PINE & FIR BRANCHES

YARROW

Yarrow (pictured), a flowering plant found throughout North America and most of the northern hemisphere, can be used as a powerful disinfectant. Rub it between the hands to disinfect them—or even use it directly on wounds!

YARROW

LONG HAUL

In addition to the natural cleaners outlined previously, the long-haul survivor can use rendered animal fat (any kind) and wood ashes to make soap (see Old-Timey Soap Making, opposite).

Foul smell

Foul smell