I never was a crumb, and if I have to be a crumb I'd rather be dead.

—Charles Luciano (1936)

And what did I get out of it? Nothing but misery.

—Joseph Valachi (1963)

Philip “Philly Katz” Albanese was part of the wave of street soldiers who reshaped organized crime on the waterfront. Born to immigrant parents on the Lower East Side, Philip went bad as a young man and, in 1935, was sent to prison for robbery. When he got out, Albanese did strongarm work for the Luciano Family and became a public loader of fruit on the Hudson River piers when they were still majority Irish. He also started moving narcotics on the waterfront.1

Albanese enjoyed his new prosperity by moving his family to the upper-middle-class neighborhood of Riverdale in the north Bronx. In 1946, he was convicted on a narcotics conspiracy, but the drug sentences were weak then, and he spent only nine months in jail. In the early 1950s, Albanese moved his family again, this time to suburban Valley Stream, Long Island.2

Then the Internal Revenue Service went after him. Federal prosecutors showed that Albanese “operated behind a paper wall of false and fictitious records to disguise his own financial interests” in a loading company. In 1954, Albanese was convicted of tax evasion for failing to pay $6,700 in taxes on his loader income between 1946 and 1950 (over $55,000 in 2013 dollars). At sentencing, prosecutors called him “one of the criminal rats which infest our waterfront today.” Enraged by the remark, Albanese leapt up out of his chair and yelled, “My business was oranges and grapefruits which come in on freighters!”3

We now have rich sources on the lives of wiseguys like Phil Albanese. In 1963, Senator John McClellan conducted groundbreaking hearings on the Cosa Nostra (hereafter “the McClellan Committee hearings”), which collect a wealth of untapped data on mob soldiers and their criminal activities. In addition, there are now dozens of mob memoirs, trial transcripts, and transcripts of mafiosi wiretaps. Although these sources have to be used with care, they can provide great insights on everyday life in the mob.4 Using the tools of social history, we can better understand the lives of wiseguys.

THE LIVES THEY CHOSE

Most young men who joined the Mafia did not do so because they lacked other choices but because they wanted to be wiseguys. For all the talk of the Honored Society defending the Sicilian peasantry, twentieth-century New York City was not Il Mezzogiorno (impoverished Southern Italy). Although Sicilian immigrants faced rampant bigotry and tough working conditions, Italian Americans soon had unprecedented opportunities. Gotham had nearly a million manufacturing jobs for blue-collar workers, and the economy was fairly booming after the Great Depression. By 1950, New York's unemployment rate was under 7 percent and most children (86 percent) ages fourteen to seventeen were attending school. To join the Mafia was to rebel against the immigrant Italian work ethic.5

Wiseguys themselves almost never claim that they needed to join the Cosa Nostra to escape grinding poverty. Rather, most simply wanted an easier life. “I was never a crumb, and if I have to be a crumb I'd rather be dead,” said Charles Luciano. He described a “crumb” as the ordinary man “who works and saves and lays his money aside.”6 As ex-mafioso Rocco Morelli explained, “I was always looking for a hustle, a get-rich-quick scheme—whatever it took to make a buck so I wouldn't have to work hard like my dad.”7 The Cosa Nostra subverted the work ethic. “You can lie, steal, cheat, kill, and it's all legitimate,” marveled Benjamin “Lefty Guns” Ruggiero, who grew up in lower-middle-class Knickerbocker Village.8 The mobster lifestyle fascinated young men. “All we knew was that they were better off than everybody else and people treated them as if they were important,” Willie Fopiano recalled of Boston's North End mobsters. “They seemed to move in some exciting, secret world that was invisible to anyone who wasn't one of them.”9

The Cosa Nostra was peddling an idea to young men drawn to its promises of honor and loyalty. “So many fine words! So many fine principles!” Antonio Calderone remembered of his initiation ceremony into the Mafia. “I really felt that I belonged to a brotherhood that had honor and respect,” recalled Sammy “The Bull” Gravano, the son of middle-class parents from Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. Of course, the Cosa Nostra did not live up to advertising. As Calderone discovered: “So many times over the ensuing years did I find myself confronted by a lack of respect for these rules—by deceit, betrayal, murder committed precisely to exploit the good faith of those who believed in them.” Likewise, Gravano became disillusioned. “I got to learn that the whole thing was bullshit,” Gravano said. “I mean, we broke every rule in the book.”10

GOING TO THE OFFICE

Mafia soldiers went to their version of the office. The mobster's office was usually hidden behind a front, literally and figuratively. Federal narcotics agent Charles Siragusa recalls the “many political clubs that were hangouts for the gangster elite” in the 1930s. The front of the Abraham Lincoln Independent Political Club in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, had an espresso machine and card tables, where men played pinochle and talked football. In the back of the club, behind a door marked “Private,” was the office where mob boss Joe Bonanno conducted the real business.11

Others preferred the anonymity of shabby storefronts. Cantalupo Realty looked like any another real-estate office in Brooklyn. However, as the front man Joseph Cantalupo recalled, each day mafiosi “were buzzed in daily through the small gate at the office waiting room, past what was my desk, down a short corridor to the private office on the left where [Joe] Colombo sat directing the traffic of his crime family.” New England boss Ray Patriarca's office was at the rear of a vending machine business. “The place was far from classy, more poor than rich, but when people spoke of ‘the Office’ this is what they meant,” said Joe “The Animal” Barboza.12

The wiseguy's day had its own kind of rhythm. “Everybody socialized while Nicky conducted business in another room,” said mob soldier Andrew DiNota, describing Gambino Family caporegime Nicholas Corozzo's social club. Goodfellas would sit around gossiping and trading information about potential scores, like which new gambling card games to shake down or new truck shipments to hijack. Then, at night, the crew “would hit various nightclubs or restaurants popular with the wiseguys and sit around planning new scores or reminiscing about old ones,” said Joseph Pistone, the undercover FBI agent who infiltrated the Bonanno Family.13

STREET WORK

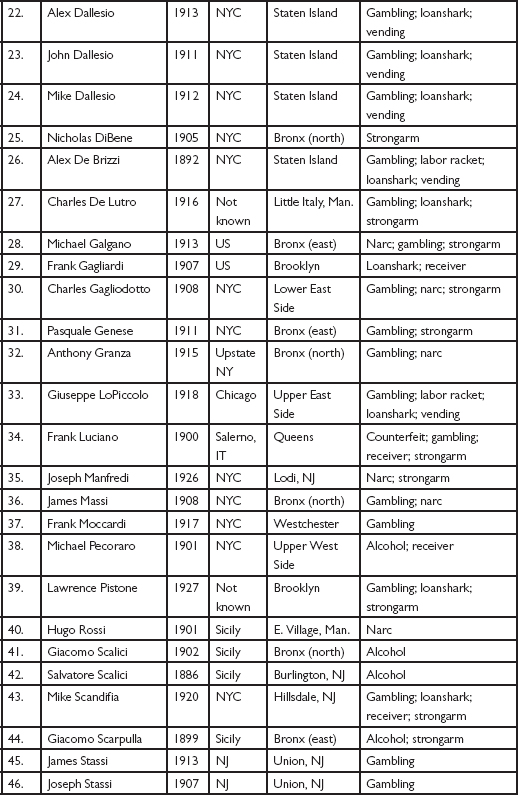

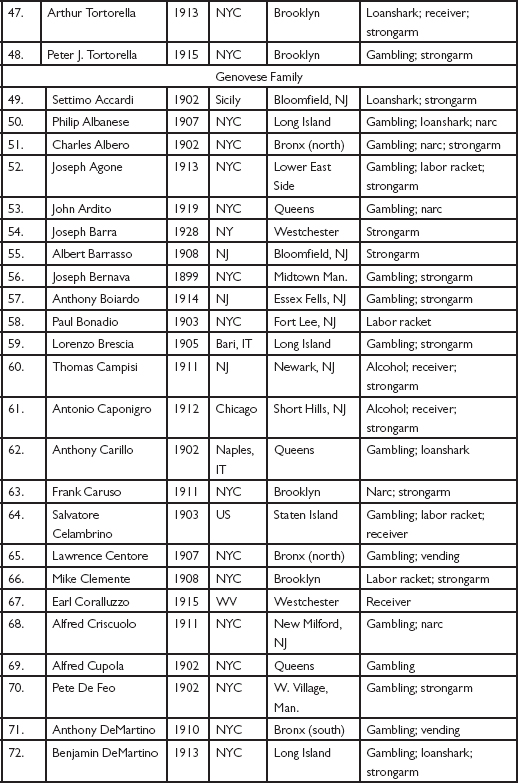

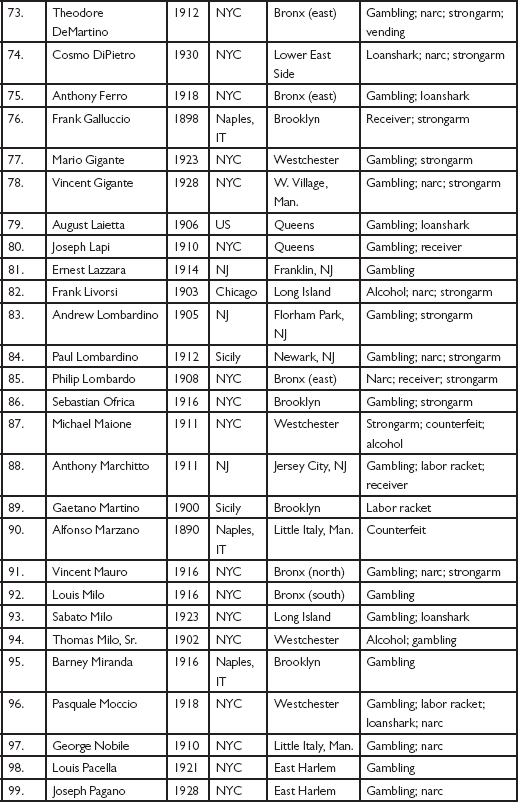

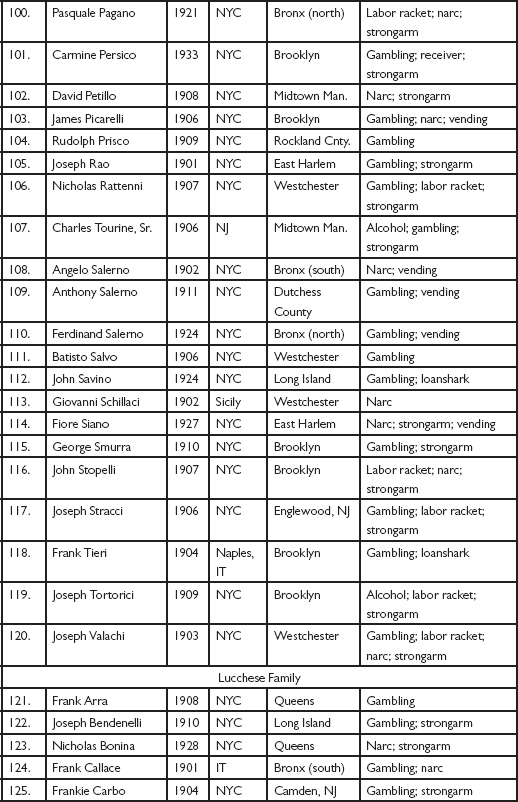

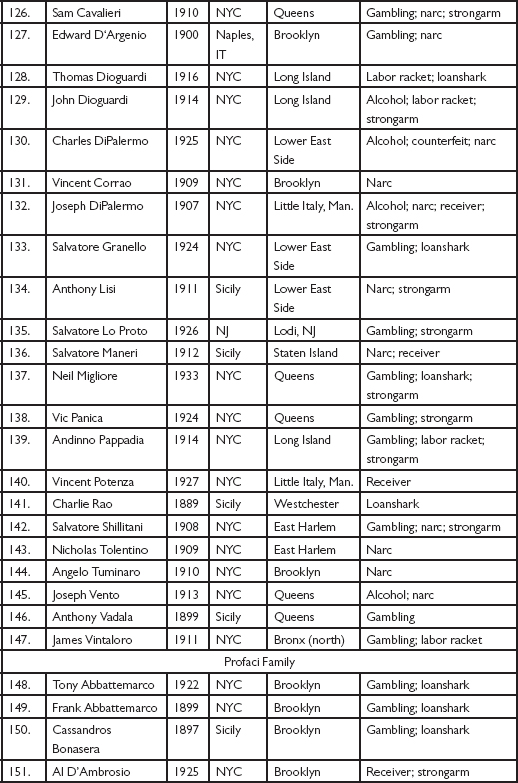

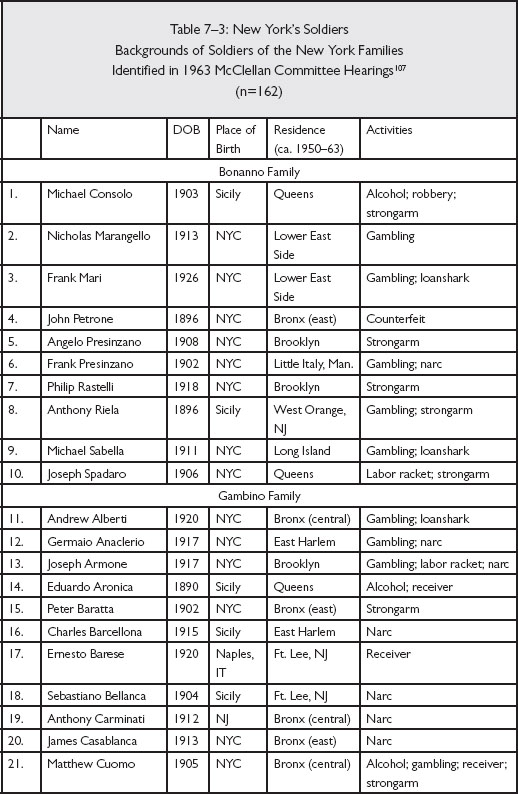

So, what exactly did wiseguys do for “work”? In 1963, the McClellan Committee hearings identified hundreds of Mafia soldiers and their activities. Based on data collected by the McClellan Committee, table 7–1 shows the top activities of the New York Mafia's soldiers in the 1950s and early 1960s:

| Table 7–1: The Work of Wiseguys Top Activities of the Soldiers of the New York Families, ca. 1950–196314 (n=162) | ||

| Categories of Activities | Percentage of Soldiers | |

| 1. | Gambling: Bookmaking for sports betting or illegal numbers lotteries. | 61% |

| 2. | Strongarm: Assault and battery, extortion, or murder. | 49% |

| 3. | Narcotics: Illegal drug trafficking or drug conspiracies. | 31% |

| 4. | Loansharking: Loans above maximum interest rates and illegal collection methods. | 20% |

| 5. | Criminal Receiver: Possessing or selling goods stolen by thievery or hijacking. | 13% |

| 6. | Labor Racketeering: Bribery of union officials, embezzlement of union funds, extortion of employers, Hobbs Act or antitrust violations. | 13% |

| 7. | Alcohol Tax: Evasion of alcohol taxes or bootlegging or moonshining operations. | 11% |

| 8. | Vending: Coin-operated cigarette, jukebox, or pinball machines. | 8% |

| 9. | Counterfeiting: Forgeries of money, checks, or government stamps. | 3% |

We have previously explored the cornerstone activities of gambling (chapter 2), labor racketeering (chapter 4), and narcotics trafficking (chapter 5). Now let us look briefly at some of the wiseguy's other major activities.

Strongarm: Assault and Battery, Extortion, and Murder

The Cosa Nostra had earned its reputation for violence. Nearly half of New York's soldiers had been involved in “strongarm” crimes like assault and battery, usually to enforce other rackets. Extortion—obtaining property through fear of violence—was a common crime of wiseguys, too. The Mafia's power rested, ultimately, on its capacity for violence.

Many of the Mafia's top leaders started out as strongarm men, including Luciano Family boss Frank Costello (convicted of illegal gun possession in 1915), Lucchese Family boss Carmine Tramunti (convicted of felony assault in 1931), and Gambino Family boss Paul Castellano (convicted of robbery in 1934).15 Mob leaders were always on the lookout for potential new soldiers, too. Andrew DiDonato gained attention of mobsters after he started extorting money from other criminals despite being only 5 feet, 9 inches and 160 pounds. “They knew if they fucked around with me, I'd get ’em with my fists, or a bat, or a tire iron,” said DiDonato of his shakedown targets. A Gambino Family crew soon recruited him into the mob.16

And sometimes the mob's soldiers murdered people. Contrary to myth, not every mafioso was a murderer (see below). But the Mafia's enforcers racked up a grisly human toll. Joe Valachi publicly detailed his roles in executing six different people.17 Gambino Family underboss Salvatore “Sammy The Bull” Gravano confessed to being involved in some way in eighteen homicides.18 Some were utterly remorseless: Carmine “Lilo” Galante was clinically diagnosed as a “psychopath” by prison psychiatrists in Sing Sing.19

Wiseguys tried to rationalize away various murders. “We do not kill innocent people,” insisted Vincent “Fish” Cafaro. He then ticked off what he saw as justifiable reasons for committing homicides, like being “a rat” or “your family got abused by someone.” The mob's soldiers purported to distinguish themselves from professional contract killers. “I don't believe in killing for money,” asserted Joseph “Hoboken Joe” Stassi. “There was always another reason, cheating or talking to the law, disobeying orders. They had a reason, even if the reason wasn't always right.”20

The mafioso lived knowing that he, too, could be eliminated by those around him. “Whenever a surprise meeting was called…there was always a sense, a fear, that this was it for you,” recalled Anthony “Tony Nap” Napoli.21 As FBI agent Joe Pistone explained, “Wiseguys wake up every day, aware that this may be the day that they get killed, at any moment, for lots of different reasons.”22 Although the Commission promised to protect wiseguys from arbitrary killings, there were no guarantees if you crossed the wrong man. “Goodfellows don't sue goodfellows,” said a mafioso on a surveillance bug. “Goodfellows kill goodfellows.”23 This realization helped fuel the fast times and high living of wiseguys.

Loansharking

Wiseguys went into loansharking because it was relatively simple, drew little attention from law enforcement, and was more profitable than bookmaking. Mob loansharks lent money above the maximum legal interest rates to bookmakers, gamblers, and overextended businessmen—people who could not get credit through banks. Of course, the terms and interest were steep: repayments at 2 to 5 percent or more per week (annual percentage rates of over 150 percent per year). “If a guy borrowed $10,000 and the loan shark charged him two points, he would have to pay $200 a week in interest—which was known as the vig or the juice—every week, and he still owed,” explained Philadelphia mobster Philip Leonetti.24

Despite—or because of—their reputation for knee-capping deadbeats, the mob's collectors only had to resort to violence sparingly for ordinary debtors. They wanted repeat customers, and they mostly relied on implicit threats. Showing up at night on the debtor's doorstep was usually intimidating enough to ensure repayment. “There's only two people I had to hit to collect. Physically, hit, I mean. Only two people. I think that says something about the reputation I had,” Sammy Gravano said of his loansharking.25 Mobster John Dalessio actually took his daughter on debt-collection trips around Staten Island. “Once a week, we'd cruise the Island in the Caddy and make stops at people's houses so my father could collect debts owed from various gambling operations,” recalled his daughter. “He'd emerge seconds later carrying an envelope or paper bag.”26 The Mafia's trademark for violence had its advantages.

Criminal Receiver: Fencing Stolen Goods, Thievery, and Hijacking

Criminal receivers sold (“fenced”) stolen goods (“swag”). Receiving was often related to thefts and hijackings. Manhattan was full of high-end consumer goods that wiseguys loved to steal. Joe Valachi got his start as a burglar who stole silk and jewelry from Manhattan stores then sold the swag to professional fences.27 “The Mafia is not primarily an organization of murderers. First and foremost, the Mafia is made up of thieves,” said FBI agent Joe Pistone.28

The Cosa Nostra specialized in hijacking targeted trucks on the highways around New York City. For a split of the profits, they would get inside tips of a lucrative shipment. Sometimes, the driver himself was involved. “Pricey stuff gets shipped everywhere. Truck drivers out for a quick buck will turn to us,” said Louis Ferrante. “Some ask me to tie them up and leave them somewhere to make it look good.”29 Like on the waterfront, shippers put up with occasional thefts because the New York market was too large to abandon. The Mafia developed fencing operations, too. “Most of the hijack loads, whether it's cigarettes, liquor, furs, appliances, or food, are shipped by the mob to discount stores they own or have connections with,” Vinnie Teresa explained. “In a matter of hours it's distributed.”30

Alcohol Tax: Bootlegging, Moonshining, and Tax Evasion

Perhaps most surprising was the wiseguys’ continued role in illegal alcohol sales after the repeal of Prohibition in 1931. This was another example of how overregulation fostered organized crime. Through the 1950s, the federal excise tax on whiskey was extremely high at $10.50 a gallon. (If the excise tax had kept up with inflation, it would be $90 a gallon in 2013 dollars instead of its current rate of $13.50). State and local fees and regulations further drove up the price of booze. Bootlegged, tax-free liquor offered significant cost savings for New York's bars and nightclubs, in which mobsters often held hidden interests.31

7–1: Joseph DiPalermo, John Longo, Nicholas Palmotto, and Carmine Galante, arrested for alcohol tax violations in 1947. (Used by permission of the John Binder Collection)

After repeal, Carlo Gambino and his brothers became the leaders of “a notorious, daring group of bootleggers” that operated secret, unlicensed alcohol distilleries around Brooklyn, New York, and Newark, New Jersey. The Gambinos supplied huge quantities of untaxed booze to Manhattan bars and nightclubs. Mob-run gay bars were infamous for their bootleg liquors.32

The Mafia's bootleggers were significant enough to be targeted by federal law enforcement well into the 1950s. As we will see, the most important mob bust in history involved Treasury Department agents of the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax Division, who were investigating mob moonshiners around Apalachin, New York, in 1957.

Vending Machines

The Mafia's most peculiar business was coin-operated vending machines. Yet it makes sense in light of the mob's practices. Organized crime first got into vending machines as an offshoot of gambling slot machines. Wiseguys then created noncompetitive “routes” for their machines by coercing bars, restaurants, and stores into using only the mob's “union”-sanctioned machines. Joseph “Crazy Joe” Gallo, a.k.a. the “jukebox king,” got his nicknames for assaulting bar owners who replaced his machines.33 The racket was easy to monitor: Gallo's machines were either in the bar or they weren't. This currency-only business was also conducive to income tax evasion.34

Senator John McClellan's committee hearings of 1957–1959 documented pervasive racketeering in the vending-machine business in New York City. Charles Lichtman, a vending-machine jobber, became enmeshed in bizarre schemes by mobsters. After Lichtman sold a new game machine to a bar owner in 1930, his mechanic was kidnapped by Dutch Schultz's gang until he removed the machine. Later on, after Lichtman became a union leader in the business, he was paid by the Associated Amusement Machine Operators of New York to “protect the locations of the various [AAMONY] operators” by picketing businesses that put in new machines by outside vendors. The mob finally shut out Lichtman from the industry. “You have no racket connections, you are nobody, so you are out,” Joe Valachi told him bluntly.35

THE MOB'S MONEY

There has been much speculation about the Mafia's money. In 1967, the President's Commission on Law Enforcement estimated that organized crime made gambling profits “as high as one-third of gross revenue—or $6 to $7 billion each year.” The commission warned that it “cannot judge the accuracy of these figures” of gambling profits.36 Nevertheless, writers have seized on these unreliable figures to give distorted pictures of the mobster life. One criminologist claimed that “any given member of Cosa Nostra is more likely to be a millionaire than not.”37 Another book on the Mafia quotes a cop as stating, “Even a simple soldier these days can wind up a millionaire.”38 Mob insiders, however, have consistently refuted the notion that ordinary soldiers routinely became millionaires.39

At the other end of the spectrum, a new history book on the Mafia portrays the soldiers as indigents, and mob bosses like Vito Genovese and John Gotti as having “a middle-class lifestyle—but nothing more.”40 The book erroneously suggests that mafiosi had little wealth because their gambling operations made only small profits.41

Both side of this debate suffer from an incomplete analysis. The narrow focus on gambling presents a skewed picture of the Cosa Nostra's diverse sources of income. Furthermore, both sides fail to account for the spending habits of wiseguys. Members of the New York families could make substantial cash incomes. However, they typically consumed it in ways which did not foster long-term wealth.

Diversified Income: The Wiseguys’ Rackets

Mobsters had to deal with interruptions in their incomes. Rackets could dry up for long stretches of time, causing low-level wiseguys to struggle financially. Stints in prison were an occupational hazard, too. When the police busted down the door of Joseph “Joe Dogs” Iannuzi, he was worried less about the charges than the disruption to his illegal income. “I was now unemployed,” said Iannuzi.42

The New York families therefore diversified into a wide variety of criminal enterprises, racketeering activities, and quasi-legitimate businesses.43 Although bookmaking was a common activity, as we saw in chapter 2, the wiseguys utilized it for basic “work” income and to raise capital for more profitable activities. Few wiseguys limited themselves solely to gambling. As shown in table 7–1, less than 10 percent of the New York soldiers identified by the 1963 McClellan Committee hearings were engaged only in gambling. Thus, it is inaccurate to project small profits from low-level bookmaking as representative of all the Mafia's income streams.

Many wiseguys were engaged in more profitable activities. Roughly 40 percent of the Mafia soldiers identified by the 1963 McClellan Committee hearings were engaged in narcotics trafficking, labor racketeering, or both (see tables 7–1 and 7–3). High-level narcotics trafficking at the smuggling and wholesale level often generates extraordinary profits and income.44 This was especially true during the 1930s through 1960s when the New York Mafia had cartel power over America's wholesale heroin markets.45

Labor racketeering generated diverse and lucrative sources of income as well. “We got our money from gambling, but our real power, our real strength came from the unions,” testified Vincent “Fish” Cafaro.46 The mob's power over unions translated into various revenue streams, including receiving bloated union salaries and no-show jobs, embezzling union treasuries and pension funds, taking bribes from employers for “strike insurance racket” and “labor peace,” using unions to set up employer cartels and collect employers’ association dues, and leveraging power over unions to gain competitive advantages for mob-owned businesses.47 Lucchese Family associate Henry Hill remembered how caporegime Paulie Vario used his power over a bricklayers’ union to create no-show union construction jobs. “We didn't even show up regular enough to pick up our own paychecks. We had guys we knew who were really working on the job bring our money,” recalled Hill.48

Suburban Mobsters

Another indication of the mafiosi's economic mobility was the flight to the suburbs after the Second World War. By the 1950s, many wiseguys had achieved roughly middle-class lives in suburban communities around the New York metropolitan area.

Like other prospering New Yorkers, successful wiseguys began moving out of inner city neighborhoods to the suburbs. As we have seen, the Mafia's traditional strongholds were Italian East Harlem, Lower Manhattan, South Brooklyn, and, to a lesser extent, South/Central Bronx. Although mobsters would continue to go into “work” in these neighborhoods, many changed their personal residences to the outer boroughs and suburban communities. “So, in the 1930s and 1940s the racketeers were our neighbors on One Hundred and Seventh Street,” remembers Salvatore Mondello, a resident of East Harlem. “The wealthiest men on my street, they left first for better neighborhoods and newer horizons.”49 The statistics in table 7–2 bear out Mondello's observation.50

| Table 7–2: The Move to the Suburbs Personal Residences of Soldiers of the New York Families, ca. 1950–196351 (n=162) | |

| Outer Boroughs and Suburbs ~ 52% | |

| Suburban New Jersey (excluding Newark, Camden, and Jersey City) | 11% |

| Queens | 10% |

| Westchester, Dutchess, or Rockland Counties (surrounding counties of NYC) | 9% |

| Long Island | 7% |

| North Bronx | 6% |

| East Bronx/Pelham Bay | 5% |

| Staten Island | 4% |

| Traditional Mob Strongholds ~ 43% | |

| Brooklyn | 22% |

| Lower Manhattan | 12% |

| East Harlem | 5% |

| South/Central Bronx | 4% |

| Other Neighborhoods ~ 5% | |

| Manhattan–Other | 3% |

| Metro New Jersey (Newark, Camden, and Jersey City) | 2% |

More than half of the soldiers identified by the 1963 McClellan Committee hearings were residing in the outer boroughs and suburbs. Mobsters sprung up in upscale communities like Rego Park, Queens, and Lido Beach, Long Island as largely assimilated suburbanites. By 1963, 80 percent of the New York Mafia's soldiers had been born in the United States.52

Take Joe Valachi, whose experience was a microcosm of the wiseguy life. The son of working-class immigrants, Valachi grew up in a cold-water tenement in East Harlem. At age nineteen, Valachi was sentenced to Sing Sing, where he made his first real contacts with mafiosi. After being initiated into the Cosa Nostra in 1930, he did strongarm work for underboss Vito Genovese, engaged in heroin trafficking, worked as a bookie and loanshark, and used his loansharking business to obtain interests in a union-free shop in the garment district and vending machines in bars. He later purchased the Lido Restaurant in the Bronx and bought a house for his family in Westchester County in order “to be in a nice neighborhood.”53 In 1959, his fortunes reversed when he was convicted of narcotics trafficking and condemned to a long sentence in federal prison. Unable to earn on the streets, Valachi lost the restaurant, the house in the suburbs, and ultimately his wife.54

Or consider John “Sonny” Franzese. The seventeenth child of Neapolitan immigrants, Franzese grew up in Brooklyn when the families were recruiting new men in the 1930s. The young thug was brought into the Mafia by Sebastian “Buster” Aloi of the Profaci Family. He was drafted into the United States Army during the war, but he was discharged in 1944 for his “pronounced homicidal tendencies.” He rose quickly with the Profaci Family as a brutal enforcer, loanshark, and extortionist who collected skims from Brooklyn bars and restaurants. He met his beautiful wife while she was working as a coat-check girl at the Stork Club. In the late 1940s, he opened the Orchid Room tavern in the burgeoning neighborhood of Jackson Heights, Queens. In 1960, he moved his family into a spacious suburban home on Long Island he bought for $39,000 (about $300,000 in 2013 dollars).55

While they were never millionaires, both mafiosi enjoyed middle-class suburban lives for decades. The fact that uneducated street thugs like Valachi and Franzese could obtain middle-class status is a perverse tribute to the capacity to make money under the Mafia.

The Wealthy Ones

A smaller minority of mafiosi made it big. Joe Valachi estimated his Genovese Family had “about 40 to 50 wealthy ones.”56 Although the net worth of a gangster is always elusive, based on evidence from tax evasion prosecutions, FBI wiretaps, and other reliable sources, there are documented cases of caporegimes and bosses who became rich on rackets:

- Luciano Family caporegime Michael “Trigger Mike” Coppola became rich from bootlegging, the numbers lottery, and labor racketeering. Coppola's wife once saw him count out $219,000 in cash on their dining room table. He explained to her that it was his regular share of the Harlem numbers. He bought a house near the ocean in Miami Beach, and he flew around the country to mob hotspots like Las Vegas. Coppola would later plead guilty to evading $385,000 in income taxes between 1956 and 1959 (about $3 million in unpaid taxes in 2013 dollars) on millions more in income.57

- Another Luciano caporegime named Ruggiero “Richie the Boot” Boiardo lived like a king in New Jersey. He first made his money as a bootlegger and speakeasy operator around Newark. As a young man, he bought audacious jewelry like a two-hundred-fifty-stone diamond belt buckle worth $5,000 in 1931 ($75,000 in 2013 dollars). Boiardo later used his profits from illegal booze and the numbers lottery to build Vittorio Castle, a lavish banquet hall with grape vineyards in the middle of Newark that attracted celebrities from New York City. He later built a “castle-like” miniature mansion worth over $75,000 in 1954 (over $650,000 in 2013 dollars) in the wealthy township of Livingston, New Jersey.58

- Genovese Family boss Anthony “Fat Tony” Salerno feasted on a variety of rackets. He held interests in the East Harlem numbers lottery and loansharking operations, engaged in labor racketeering with the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, and ran many construction industry rackets. In the 1950s, Salerno split his time between his horse ranch in Dutchess County, his apartment in tony Gramercy Park South, and his house on the exclusive Venetian Islands in Miami. In 1978, Salerno pled guilty to criminal charges of gambling and tax evasion for failing to pay $76,578 in income taxes ($273,000 in unpaid taxes in 2013 dollars) on over a million dollars in income.59

- Lucchese Family boss Anthony “Tony Ducks” Corallo started out life as a humble tile setter in East Harlem, then spent the rest of his life looting labor unions and industries in New York. As a venal labor racketeer, he took to flashing fat wads of cash, and moved his family into the wealthy neighborhood of Malba, Queens. In 1968, Corallo was convicted along with others of paying a $40,000 bribe for the award of an $840,000 city parks contract (a $268,000 bribe for a $5.6 million contract in 2013 dollars). The FBI placed an electronic bug in Corallo's black Jaguar. One day, Corallo's driver spotted FBI agents trailing them. His driver suggested they were following them because they thought Corallo controlled the toxic-waste-disposal business. “They're right,” responded Corallo, unaware he was on tape.60

- Gambino Family boss Paul Castellano wanted to appear to be another successful businessman in his fifteen-thousand-square-foot mansion on Todt Hill in Staten Island. When FBI agents wiretapped his estate, however, they discovered that his “legitimate” businesses were bolstered by racketeering. His son's Scara-Mix Concrete Company enforced a concrete cartel on Staten Island. His meat companies and union ties gave him monopolistic power in the wholesale meat markets. Meanwhile, his “industry association” controlled no-show jobs in the garment district. Castellano's power and income derived largely from the Gambino Family's control of key union locals. “Our job is to run the unions,” Castellano was picked up saying on a bug.61

The Ghost of Al Capone: Avoiding Fixed Assets

When the Treasury Department convicted Al Capone on tax evasion charges for failing to report income from illegal sources, it had a lasting impact on the Mafia. According to a report by Chicago bankers in the 1930s, mobsters began putting money into legitimate businesses so they could “withstand an investigation and show that they were earning sufficient income to enjoy the expensive living they were enjoying.” The New York Mafia was permanently affected by the Capone prosecution, too. “After Capone went down, word spread around the Mob: give Uncle Sam his vig,” said Louis Ferrante. “I wasn't going the way of Capone,” vowed Lucchese Family associate Henry Hill. “That was the hardest part; hiding the money, not making a hit.”62

The threat of an Internal Revenue Service (IRS) investigation caused mafioso to hide cash or avoid too many fixed assets that marked wealth. Big savings accounts and large homes had to be justified with “legitimate income” from businesses. New England boss Gennaro “Jerry” Angiulo beat the IRS by gradually funneling money from his illegal gambling operations into his golf course, a bowling alley, hotels and motels. Henry Hill laundered money through a shirt company and “paid cash for everything [so] there were no records or credit card receipts.” As FBI agent Joe Pistone said, “The IRS doesn't have a chance against wiseguys” because they paid for everything with thick rolls of “Lincolns and Hamiltons.”63

These extralegal measures did not encourage optimal savings and wealth creation. Jimmy Fratianno had to take hidden interests in casinos, with no paperwork, and stash away stacks of cash. Mafiosi could not simply use their cash to purchase major assets like homes. “You have to either borrow money or something if you want to buy a house. [The IRS] would say where did you get the money,” explained Fratianno.64 This frustrated normal investments. “They can't invest it without going through fucking fronts…what good is it?” complained Fratianno. “Even when they die, their heirs's got to hide the money.”65 The wife of a Gambino Family soldier lamented how she and her husband had to limit their legal assets. “Later on, when the money started coming in, everything we ever bought in the way of property—houses, office buildings, and so on and so forth—had someone else's name on the papers, not ours,” said Lynda Milto.66 Put another way, the Lucchese Family never had a pension and savings plan. Most wiseguys would not have contributed to it anyway.

In 1954, the Justice Department prosecuted Frank Costello for federal income tax evasion under a different theory. Rather than trying to establish all of Costello's illegal income, the government went through the arduous process of proving that the mob boss's spending far exceeded his declared income and assets. At trial, prosecutors painstakingly called 144 witnesses and introduced 368 exhibits to prove that Costello and his wife spent nearly $60,000 in 1948 ($580,000 in 2013 dollars) and more than $90,000 in 1949 ($872,000 in 2013 dollars).67

Although this prosecution strategy was difficult to replicate, it provided an early window on the mob lifestyle. Costello's rampant consumption was not unusual. Wiseguys spent money at astonishing rates.

Spending Money Like Water

Wiseguys spent their money on a high-consumption lifestyle. When Vincent “Fish” Cafaro was asked what he did with the millions of dollars he made, he described a spendthrift life:

| Senator Nunn: | Did you save any of it?… |

| Mr. Cafaro: | Nope. |

| Senator Nunn: | What happened to it? |

| Mr. Cafaro: | You want to tell them, Eleanore [his wife]? I spent it, Senator. Just gave it away…. As I was making it, I was spending it: women, bartenders, waiters, hotels. Just spending money. |

| Senator Nunn: | Spending, $400,000, $500,000, $600,000, $700,000 a year? |

| Mr. Cafaro: | Sure. |

| Senator Nunn: | A million dollars a year in some years? |

| Mr. Cafaro: | If I had it to spend, I'd spend $3 million.68 |

Wiseguys spent their money on all kinds of lavish consumption, starting with the mob nightlife. “Most of them like to be in the limelight. They like to get all dressed up and go to a fancy place with a broad on their arm and show off,” explained Vincent “Fat Vinnie” Teresa. Sammy “The Bull” Gravano recounted his big-spending nights on the town picking up tabs, leaving huge tips, and ordering champagne and prime steaks. “It was let's go to the Copa…and I'm broke again and its macaroni and ricotta at home,” said Gravano.69

Wiseguys tended to spend freely in their personal relationships, too. Anthony “Gaspipe” Casso recounted “spending money like there was no tomorrow” with his young wife. They went on frequent vacations to Saint Thomas, Bermuda, and Las Vegas, routinely dined at the best restaurants in Manhattan, and always saw the latest Broadway shows.70 Quite often, wiseguys were spending money on mistresses, too. “Everybody who had a girlfriend took her out on Friday night…wives went out on Saturday night,” recounted the wife of Henry Hill.71 The other woman could be costly. “Some wiseguys will set their girlfriends up with an apartment and stipend,” said Joe Pistone.72

Mobsters loved precious jewelry, stylish clothes, and new automobiles, too. As a young bootlegger, Charles “Lucky” Luciano took to wearing real gold jewelry.73 The attendees of the 1957 meeting of the Mafia at Apalachin drove luxury Lincolns and Cadillacs. Gangsters wanted to signal their success in the neighborhood. “Ninety percent of mob guys come from poverty,” Vincent Teresa explained in 1973. “Now they made it. They got money, five-hundred-buck silk suits, hundred-buck shoes, ten-grand cars…[t]hey want everyone to know they've made it.”74

Ironically, many wiseguys ended up blowing their own money on gambling. “Whether we bet on horses or sports or dice or cards, gambling was like breathing for Mob guys—we couldn't live without it,” said Sal Polisi. “That's not to say everybody was good at it. Most Mob guys were chronic losers, and a lot of those who weren't were mediocre at best.”75 John Gotti was a compulsive gambler who reportedly lost $90,000 on college bowl games over a single weekend.76

Spending on the mob lifestyle often came at the expense of long-term savings or housing. “We'd cash the checks [from no-show jobs], and by Monday we'd blown the money partying or buying clothes or gambling,” recalled Henry Hill. “I said I didn't have to save it because I would always make it. And I wasn't alone,” explained Hill, who still managed to buy a house on Long Island for his wife. Other mob spouses were less lucky. “Tommy DeSimone always drove around in a brand-new car and wore expensive clothes, and he and Angela lived in a two-room tenement slum,” said Hill's wife, Karen.77 Mobsters simply spent their money on different things than responsible citizens. Indeed, the reason that reporters were surprised that John Gotti lived in a modest house in Howard Beach was that he routinely emerged from chauffeured cars in custom-made suits at some of Manhattan's finest clubs and restaurants.78

Still, the mob lifestyle was fun to them. “I like gamblin’; I like women,” said Charles Luciano when he was asked how he spent his millions. “Those are the two things that make money go fast. It came and it went.”79 Lucky Luciano's attitude toward money was not unusual. “The money rolled in. Sometimes it went out faster than I could steal it, but I liked the life,” Vinnie Teresa explains.80 Gambling was simply a form of regular entertainment for them. “We were at the track, shooting craps in Vegas, playing cards, and betting on anything that moved. Not a thrill like it in the world,” Henry Hill recalled fondly.81 This kind of economic consumption hardly fostered wealth. But goodfellas valued it more than retirement savings. After all, a Mafia soldier never knew how long he had.

MYTHS ABOUT THE WISEGUY LIFE

Now that we've seen what the life was, we should clear up what it was not. Let us dispense with some of the major myths about being a wiseguy.

Myth Number One: “Made My Bones”

The first myth is that no one could become a “made man” until he first murdered someone for the Mafia. Mario Puzo popularized the idea in the 1969 novel The Godfather by having Sonny Corleone say: “I ‘made my bones’ when I was nineteen, the last time the Family had a war.”82 The phrase referred to transforming a living human into a stack of bones.83

This idea was revived by the 1997 film Donnie Brasco, based loosely on FBI agent Joseph Pistone's infiltration of the Bonanno Family. In the climactic (fictionalized) scene, the FBI pulls Brasco off the hit that will let him become a “made man” only seconds before the target is about to be shot.84 But in his book, Joe Pistone described a highly malleable “rule” that was routinely disregarded. Pistone recalls how caporegimes “sometimes lied by omission on that issue to get a guy made,” saying that “close friends or relatives” were proposed for membership despite no hits, and that some prospects just paid off their caporegime to get made.85

The bloodbath from such a homicidal rule makes it incredible, too. There were approximately five thousand “made men” in Gotham by the 1950s. Given that some mob hitters killed several people, for each mafioso to “make his bones,” the homicides would exceed five thousand victims. Yet there were under six thousand total homicides from all sources in New York City during the 1930s. Even if these alleged mob corpses were spread over the 1940s and ’50s, the mayhem from that many gangland hits would have been intolerable. “It would have been impossible for every made guy to have killed for such exalted status,” concludes writer Carl Sifakis.86

Myth Number Two: “The Mafia's Code of Omertà”

Another myth is that, until recently, mafiosi strictly adhered to omertà (the code of silence). Joe Valachi is mistakenly called “the first Mob turncoat to break the Mafia's code of omertà.”87 But Valachi did not testify until 1963. Long before Valachi, mafiosi were singing to the G-men:

- In the 1890s, Charles “Millionaire Charlie” Matranga testified in court against rival mafiosi in New Orleans. After the Matrangas were shot up, Charlie cooperated with the police in bringing charges against Joe Provenzano. In 1890, Matranga testified that Provenzano had threatened “bloodshed all along the wharf” if he did not get a piece of the waterfront.88

- Francesco Siino was the boss of a 670-member cosche in southwestern Sicily. During a bloody fight with rivals, he became an informant for a questore (government official). “I know that the cause of persecution of so many sons of good mothers is none other than that infamous cop-lover Francesco Siino,” yelled a mafioso as he was being arrested.89

- In the 1910s, the Morello Family, the “First Family” of New York, was crippled by informants. Facing prison time for counterfeiting, Salvatore Clemente, a close confidant of the Terranova brothers, became a paid informant for the United States Secret Service. For years, Clemente fed the Secret Service a steady stream of intelligence on the Morello Family.90

- In 1921, New York City detective Michael Fiaschetti persuaded Bartolo Fontano to confess to a murder he participated in with a gang of mafiosi called “the Good Killers.” Fontana revealed an interstate network of mobsters, including future boss Stefano Magaddino.91

- As the drug war heated up, mafiosi began trading information to avoid charges. As we saw earlier, in 1923, none other than Charles Luciano cooperated with federal agents to stay out of prison.

- Then there is Nicola Gentile, who became a fugitive on drug charges in 1939. In his memoirs, Gentile boasts of exercising “superhuman control over myself” to resist interrogation. The State Department's files tell a different story: it was Gentile who was pestering the government for a deal. On March 29, 1940, a cable said Gentile had “given valuable information…and it is believed that his testimony would be valuable in pending cases.”92

- Detroit mafioso Chester LaMare, meanwhile, had been informing for the United States Secret Service in its counterfeiting investigations.93

- In 1937, Dr. Melchiorre Allegra revealed the inner workings of the Sicilian Mafia. Dr. Allegra was a physician in Sicily who became a member of the Pagliarelli Family. After he was arrested in 1937, Allegra agreed to give testimony about the Sicilian Mafia. Long before Valachi, Dr. Allegra testified about the structure, practices, and rituals of his cosche.94

- In 1945, Peter “Petey Spats” LaTempa was to be the key witness corroborating Ernest “The Hawk” Rupolo's confession implicating Vito Genovese in the 1934 murder of Ferdinand Boccia. LaTempa committed suicide while in protective custody.95

- In the early 1950s, Lucchese Family soldier Eugene Giannini was informing for the Federal Bureau of Narcotics. Giannini revealed secrets such as how “the mob is broken down in geographic organizations,” that Tommy Lucchese's “primary sphere of activity was in the garment center,” and that Lucchese had “group leaders” like Joseph Rosato under him. On September 20, 1952, a hit team sent by Joe Valachi shot Giannini twice in the head before symbolically dumping his body on East 107th Street.96

- Around the same time, Dominick “The Gap” Petrilli, ironically, was informing on Gene Giannini. “The Gap is back. He got picked up in Italy for something and made a deal with the junk agents,” warned Anthony “Tony Bender” Strollo, a lieutenant of Genovese. On December 9, 1953, three assassins murdered Petrilli at a bar in the Bronx.97

- In July 1958, Cristoforo Rubino became another informer to fall before testifying against Mafia drug traffickers. A week before he was to testify before a grand jury investigating Vito Genovese and other traffickers, Rubino was shot dead on a Brooklyn sidewalk.98

- In May 1962, Profaci Family dissident Larry Gallo disclosed to the FBI the existence of “The Commission,” one of the most explosive secrets of the Cosa Nostra. Gallo revealed that “JOSEPH PROFACI, THOMAS LUCHESE [sic], CARLO GAMBINO, and VITO GENOVESE were due a high degree of respect and were members of the leadership group called ‘The Commission.’”99

We know there were other early informers whose names remain hidden behind black marker in redacted FBI files. The Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) bars the disclosure of deceased informants, even if they passed away fifty years ago. But the truth has a way of rising to the surface. Former FBI agent Anthony Villano said he knew of a dozen “member sources,” including “a couple names that would shock both the public and the LCN.”100 In coming years, we may be surprised by which Men of Honor betrayed each other to the feds.

Myth Number Three: “There's No Retiring from This”

The last major myth is that wiseguys could never leave the life. “Just when I thought I was out, they pull me back in,” Michael Corleone laments in The Godfather Part III. “You took an oath. There's no retiring from this,” Tony Soprano tells a soldier who wants out in The Sopranos.101

Except that many wiseguys did retire. As of the 1950s, Joe Valachi testified that while there were two thousand active members in New York City, there were also “about 2,500 or 3,000” men who were “inactive members.”102 So, who were these thousands of erstwhile mafiosi who had left the life? They fall roughly into two categories: (1) businessmen, and (2) old men.

Some mafiosi found more profitable work outside crime. Take William Medico of Pittston, Pennsylvania. Medico grew up in the same Sicilian neighborhood as mob boss Russell Bufalino. He joined Bufalino's northeastern Pennsylvania family, and he was arrested several times in this youth. Then, something unusual happened: he became a successful businessman. He built Medico Industries, Inc., into one of the biggest heavy-equipment companies in Pennsylvania, even fulfilling defense contracts for the United States Army.

While Bill Medico continued to associate with the Bufalino Family, he was preoccupied with his legitimate business. In November 1957, Medico let his cronies borrow a company car to drive to the Mafia meeting in Apalachin, but he did not bother attending himself. After Apalachin, Medico agreed to be interviewed about his business by FBI agents, who found nothing illegal. Unlike Paul Castellano's business interests, the government identified no racketeering activities associated with Medico Industries or the heavy-equipment industry in general. Bill Medico was never again charged with a crime. The wiseguy had more or less gone legit.103

Many more simply aged out of the life. When Salvatore Falcone reached his seventies he retired to Miami, Florida, like thousands of other elderly snow birds. Informants said that “due to advanced age and ill health, he has been replaced by his brother JOSEPH FALCONE of Utica, New York.” The FBI noticed that after Joseph “Staten Island Joe” Riccobono entered his seventies, he “sort of retired” to the status of “an elderly statesman.” Meanwhile, the aging mafioso Minetto Olivere left the Milwaukee Family for California, where he “retired and manages the local American-Italian Club in San Diego.”104

Even a turncoat could leave if he was no longer a threat. At the end of his memoirs Vita di Capomafia (“Life of a Mafia Boss”), Nicola Gentile renounced “my active life as a member of the honorable society,” saying he was leaving as “a lonely and embittered old man.”105 Although the Mafia considered killing him, they let him die in poverty in rural Sicily. “The rules of the Cosa Nostra aren't always carried to the extreme,” explained Antonio Calderone.106

Such were the lives of wiseguys.