Judges

1. INTRODUCING THE ERA OF THE JUDGES (1:1–3:6)

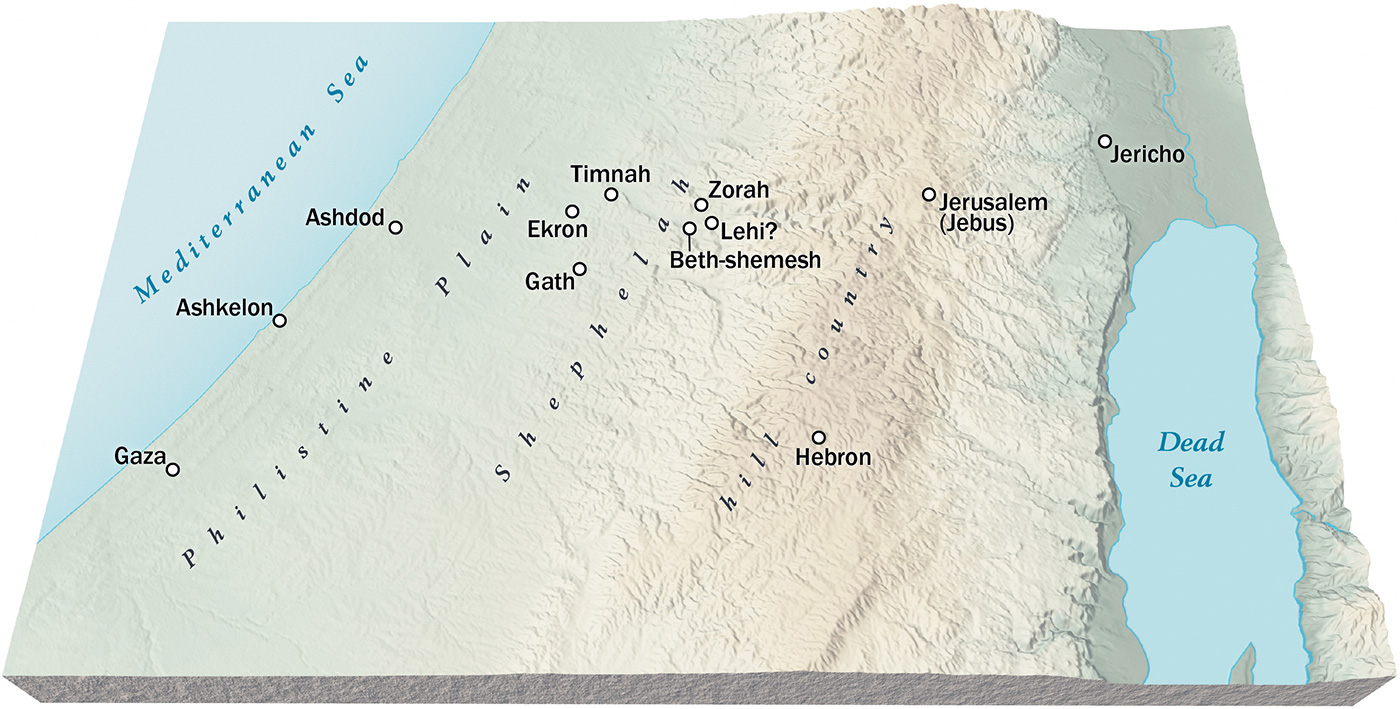

A. Military failures (1:1–2:5). The book of Joshua ends with the death and burial of Joshua (Jos 24:29–30). The book of Judges begins with an extended report of Israel’s military progress after Joshua’s death (1:1–36). Taken as a whole, this tribal conquest report seems designed to highlight a pattern of progressive deterioration. Four stages of deterioration can be discerned: (1) Judah and Simeon are able to dispossess some of the Canaanites, such that there is no mention of the Canaanites having to live among them (1:1–20). (2) Benjamin to Zebulun are unable to dispossess the Canaanites but seem to be in a dominant position, as they allow the Canaanites to live among them (1:21–30). (3) Asher and Naphtali are also unable to dispossess the Canaanites but seem to be in a subordinate position, as they have to live among the Canaanites (1:31–33). (4) Dan is stymied by Amorites and is unable even to set foot on its allotted land (1:34–36).

1:1–3. Having received prior instructions to destroy the Canaanites and take possession of their land (Nm 33:51–53; Dt 1:8; 7:1–4, 16), Israel begins by asking the Lord which tribe should lead the way in battle (1:1). After Judah is chosen and promised victory, the tribe takes leadership by inviting Simeon, whose allotted land falls within Judah’s boundary (cf. Jos 19:1–9), to join them in battle (1:2–3).

1:4–8. Judah meets with a string of initial successes, including at Bezek, where they capture its leader and become the instrument of divine vengeance by doing to him what he had previously done to other defeated kings (1:4–7). Then Judah engages the enemy in three different regions: the hill country, the southern land (Negev), and the Judean foothills (Shephelah), with the results summarized in the report that follows.

1:9–15. In the hill country, under the leadership of Caleb and his family, Judah is able to take Hebron and Debir (1:10–11; cf. Jos 14:6–15; Jdg 1:20). While Caleb’s promise to give his daughter Achsah as a reward to whoever is able to capture Debir (1:12) may seem objectionable to modern sensibilities, in so doing, Caleb is also ensuring that Achsah will be married to a valiant warrior who is able to fulfill the Lord’s command to dispossess the enemy. Besides, Caleb’s readiness to grant Achsah a blessing in the form of springs of water reinforces his overall benevolent intention toward his daughter (1:15).

1:16–17. Regarding the Negev, after briefly noting that the Kenites have relocated there with some Judahites, the author reports that Judah helps Simeon destroy Zephath. The city, previously allotted to Simeon (cf. Jos 19:4, using the city’s new name), is then renamed Hormah.

1:18. As for the lowlands, 1:18 reports that Judah is able to take the Philistine cities of Gaza, Ashkelon, and Ekron.

1:19–20. But Judah’s war effort is not without setback. According to 1:19, despite the tribe’s success in the hill country, it is unable to dispossess the Canaanites in the plains because the enemy there has iron chariots. For some the mention of iron chariots exonerates Judah since its failure is only due to the enemy’s superior technology. A careful consideration of other mentions of “iron chariots” suggests otherwise. After all, when the Joseph tribes suggested in Jos 17:14–18 that the enemy’s iron chariots were too strong for them, Joshua dismissed this by affirming the tribes’ ability to conquer enemy territory in spite of the iron chariots. In fact, Barak’s ability to defeat Sisera in Jdg 4, even though the latter has nine hundred iron chariots (4:3), proves Joshua’s point. Thus, rather than exonerating Judah, the mention of iron chariots in 1:19 actually highlights the tribe’s failure.

1:21. After the lengthy report on Judah, the author then quickly moves through the rest of the tribes west of the Jordan, following a roughly south–north trajectory. The next tribe to the immediate north is Benjamin, who fails to dispossess the Jebusites living in Jerusalem. Despite the assertion in 1:8 that Judah took Jerusalem, Jerusalem is actually part of the territory allotted to Benjamin (Jos 18:28). Thus, Benjamin has ultimate responsibility to dispossess it. The capture of the city reported in 1:8 may merely represent an initial victory where Judah, in obedience to the Lord’s command to lead the way (cf. 1:1–2), launches a successful initial assault. What 1:21 highlights, then, is Benjamin’s failure to follow up on that initial victory to permanently take possession of what has been allotted to them.

1:22–26. As the northward progression continues, the focus moves to the two Joseph tribes, whose allotments are immediately north of Benjamin. Here, the joint effort of the two tribes is first reported (1:22–26) before the individual efforts of Manasseh (1:27–28) and Ephraim (1:29) are reported.

At first glance, the joint effort spells success for the two tribes, as they not only enjoy the Lord’s presence (1:22) but also are able to conquer Bethel/Luz (1:23–26). But on closer examination, the success at Bethel/Luz is perhaps not all that it appears. First, that the Joseph tribes need to cut a deal with a local inhabitant to be shown a way into Luz seems to suggest an inability to take the city without such help. Second, since the man spared promptly goes away and builds a new Luz, the spirit of Luz is not vanquished but lives on merely at a different location.

1:27–36. The Bethel/Luz episode is then followed by a series of short reports concerning individual tribes, including Manasseh and Ephraim (1:27–29) as well as the northern tribes of Zebulun, Asher, Naphtali, and Dan (1:30–36). All these tribes fail to dispossess the cities allotted to them in Jos 16–19. Here, it should be noted that Dan was originally allotted land on the southern coastal plains next to Judah (Jos 19:40–46). Unable to take possession of that land, the tribe eventually moved to the far north (cf. Jos 19:47; Jdg 18:1–31), so that it ends up last on the list.

2:1–5. Given the Lord’s specific commands for Israel to take possession of the land and destroy its inhabitants (Nm 33:51–56; Dt 1:8; 7:1–4, 16), it is not surprising that an angel of the Lord is sent to confront the people for their disobedience in making covenants with the local population rather than dispossessing them (2:1–2). Announcing the withdrawal of his earlier promise to dispossess the local population for them (cf. Dt 7:1–2, 17–24; 9:1–5; 11:22–25; 31:3), the Lord warns that those spared by the Israelites will end up being a source of future trouble for them (2:3). On hearing this, the people weep, which explains the subsequent naming of the place as Bochim, meaning “weepers” (2:4–5).

B. Spiritual failures (2:6–3:6). 2:6–10. After reporting Israel’s military failures, the narrative then shifts to the people’s spiritual failures. Since the spiritual failures occur simultaneously with the military failures, the author traces how they came about by taking the reader back to the death of Joshua. The wording of 2:6–9 is very similar to Jos 24:28–31 and highlights the fact that, while under the leadership of Joshua and the elders who had personally experienced the Lord, the people continued to serve him. But after the death of Joshua and that generation of elders, another generation grew up without any knowledge of the Lord or what he had done for Israel. This ushers in an era of spiritual decline, where the nation’s history seems to be locked in a series of downward spirals.

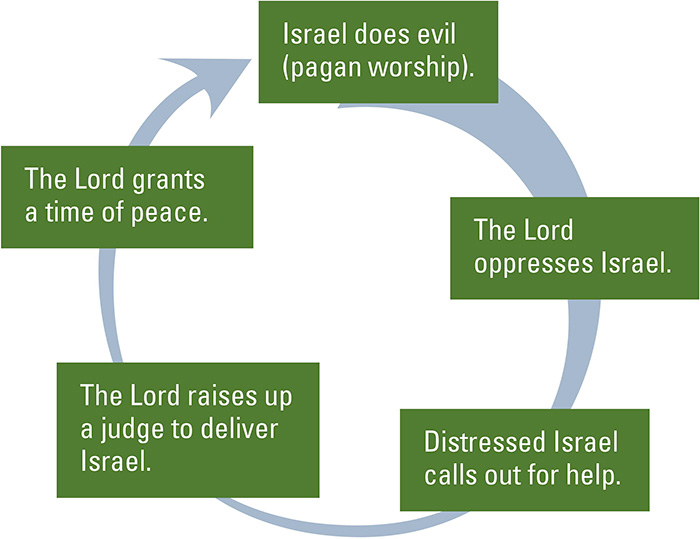

2:11–19. A recurring vicious cycle is introduced in 2:11–19, and this becomes the pattern according to which most of the subsequent narratives about the judges are organized. The cycle essentially consists of five stages: (1) the people do evil in the eyes of the Lord by worshiping idols (2:11–13); (2) the Lord, in his anger, gives Israel into the hands of foreign oppressors (2:14–15a); (3) the people cry out to the Lord in their distress (2:15b, 18b); (4) the Lord raises up judges to deliver the nation from its oppressors (2:16, 18a); (5) the land has rest (not specifically mentioned in 2:11–19, but recurring in many of the subsequent narratives of the judges). But after each judge dies (and sometimes even while the judge is still living; cf. 8:27), the people inevitably return to idolatry, thus initiating the cycle all over again (2:17, 19).

Two further comments need to be made about this cyclical pattern. First, the people’s crying out in stage three is to be understood not as acts of repentance but simply as cries for help. That is why in 10:14, the Lord, in anger, tells the people to “cry out” to the gods they have chosen instead. That being the case, the Lord’s intervention in stage four is to be understood as a gracious and compassionate act to the undeserving rather than a response to genuine repentance.

Deuteronomy stresses the importance of teaching God’s words to the next generation (Dt 6:7, 21–23; 11:9). The book of Judges proves why this is so important: after Joshua, “another generation rose up who did not know the Lord” (Jdg 2:10), and this sends them spiraling out of control.

Second, note also that the cycles are not simply static recurrences, but according to 2:19 each represents a further deterioration from the one before. This is also discernible in the narratives of the judges, such that a particular theme found in one narrative will reappear in a subsequent narrative but show trends of worsening. Moreover, even the cycle itself breaks down as it progresses. Thus, beginning with the Jephthah cycle, the land is no longer said to be at rest after each deliverance, and in the Samson cycle, there is no longer any report of the people crying out to the Lord when they are oppressed.

2:20–3:6. As in 2:1–5, where Israel’s military failures result in rebuke and the withdrawal of the Lord’s promise to dispossess the nations, so too the report of Israel’s spiritual failures is also followed by a similar rebuke and withdrawal of earlier promises. The content of 2:20–21 is not substantially different from 2:1–3, except for the further disclosure that the presence of the nations also serves to test the extent of Israel’s obedience (2:22; 3:4) and to teach warfare to a generation without battle experience (3:1–2). Unfortunately, regarding the test, Israel clearly fails, as 3:5–6 reports that the people not only live among the local population but have also intermarried with them in violation of the Lord’s explicit commands (cf. Dt 7:1–4). And as Dt 7:4 foresaw, intermarriage has indeed led to apostasy, as the Israelites also “worship other gods.”

2. EXPLOITS OF ISRAEL’S JUDGES AND LEADERS (3:7–16:31)

The book now moves into a section where the exploits of Israel’s various judges constitute the main focus. But despite the highly individual character of these narratives, the section as a whole is intricately tied to the material in the preceding section. This can be seen in that elements of the cyclical pattern found in 2:11–19 regularly appear at the beginning and end of each major judge narrative to form a frame. The narratives about the major judges in this section are thus to be understood as concrete illustrations of the cyclical pattern introduced in 2:11–19.

A. Othniel (3:7–11). Unlike the other narratives to follow, the narrative of the Judahite judge Othniel is very brief and consists primarily of stereotypical phrases already found in 2:11–19. Othniel is the only major judge presented without any discernible character flaw. It is likely that the author has intentionally set him as an ideal paradigmatic model against which subsequent judges are to be compared.

Following the expected pattern, the cycle begins with Israel doing evil in the eyes of the Lord by worshiping idols (3:7). This results in the Lord giving the nation into the hands of Cushan-rishathaim, a king who likely comes from northern Mesopotamia (Aram-naharaim is literally “Aram of Two Rivers,” referring probably to the Euphrates and the Habur). Israel is subjected to him for eight years (3:8). But as the people cry out to the Lord, the Lord raises up Othniel by sending his Spirit on him (3:9–10a). He defeats Cushan-rishathaim in battle and brings rest to the land for forty years, until his death (3:10b–11).

B. Ehud (3:12–30). 3:12–14. After the death of Othniel, Israel once again does evil in the eyes of the Lord (3:12). The Lord then empowers Eglon, king of Moab, who, with the Ammonites and Amalekites, oppresses Israel for eighteen years (3:13–14). Israel then cries out to the Lord, who responds by raising up Ehud as deliverer.

3:15. Ehud is first introduced in 3:15 as a “left-handed” man, which in Hebrew is literally a man “restricted in his right hand.” Considering that Ehud is from the tribe of Benjamin, whose name literally means “son of my right hand,” that a judge from the tribe of right-handers is restricted in his right hand immediately presents Ehud as an unlikely candidate for a deliverer.

3:16–20. To carry out his assassination (3:17–26), Ehud appears before Eglon as a tribute bearer for Israel. Because of his left-handedness, Ehud is able to smuggle his sword into the palace by strapping it to his right thigh, where no one would normally expect a weapon to be carried (3:16–17). After presenting the tribute, Ehud pretends to leave with his entourage, only to turn back near Gilgal with claims of a secret message for Eglon (3:18–19). The meaning of the word translated “carved images” in 3:19, 26 is uncertain, but it likely refers to the engraved boundary stones that mark national borders. If so, the fact that Ehud turns back alone at the border after having sent his own entourage on might have convinced Eglon that he indeed had a secret message to convey that he did not want his colleagues to know about.

A bronze dagger blade. Ehud brings a short double-edged sword to his meeting with King Eglon (Jdg 3:16).

© Baker Publishing Group and Dr. James C. Martin. Courtesy of the Oriental Institute Museum, University of Chicago.

Ehud’s actual words are not without ambiguity. The Hebrew word for “message” in 3:19–20 can equally mean “word” or “thing.” Thus, while Eglon thinks Ehud has a divine message for him, Ehud may be thinking about the thing (weapon) he has prepared for Eglon on behalf of the Lord.

3:21–26. When Eglon unsuspectingly dismisses his attendants and rises to receive what he thinks is a divine oracle, Ehud quickly deploys his hidden sword and plunges it into Eglon’s belly (3:21).

There is some debate regarding what comes out in 3:22 after the blade goes in. It may be the obscure Hebrew word is a reference to fecal matter coming out of Eglon as he dies. If this is correct, then the accompanying smell would explain why the servants later think their king is relieving himself (3:24). By the time these servants lose patience and open the locked door only to find their king dead, Ehud has already escaped back to Israel (3:25–26).

3:27–30. Sounding the ram’s horn, Ehud rallies his people with the declaration, “The LORD has handed over your enemies, the Moabites, to you” (3:27–28a). Ehud and his army then block off the fords of the Jordan, thus cutting off possible Moabite reinforcement from across the river. Having struck down ten thousand Moabites, Israel then subjects Moab to them for the next eighty years (3:28b–30).

C. Shamgar (3:31). The account of the next judge, Shamgar, is very brief and reminds one of Samson (13:1–16:31) because of the unusual weapon and the Philistine enemy that both narratives share in common. The name Shamgar son of Anath, however, is a non-Israelite name, possibly of Hurrian or Syrian origin. Although not much else is known about him, his inclusion as one of the judges shows that the Lord uses even non-Israelites to deliver his people.

D. Deborah and Barak (4:1–5:31). 4:1–3. Before long, Israel again does evil in the eyes of the Lord, resulting in the Lord selling them into the hands of the Canaanite king Jabin and his commander Sisera (4:1–2). Possessing superior technology in the form of iron chariots, they oppress Israel for twenty years (4:3).

4:4–5. Israel’s cry to the Lord is followed immediately by the appearance of Deborah. This and the description of her as “judging” Israel give the impression that Deborah must be the next judge in focus. But Deborah’s role within the narrative, primarily having to do with speaking (4:5–6, 9, 14), is more consistent with her being a prophetess (4:4) than a judge. In addition, although she is said to be “judging” Israel, this “judging” is immediately qualified in 4:5 as judicial in nature. As this is the only time within the book where the “judging” of one of Israel’s leaders is so qualified, it may be intended to distinguish Deborah’s judging from the kind of military deliverance associated with the book’s other judges. In fact, 4:14 seems to suggest that after giving the rallying cry, Deborah does not join in the battle. Nor is she mentioned again in the rest of the chapter describing Israel’s victory. Thus, Deborah is not actively involved in the military aspect of Israel’s deliverance.

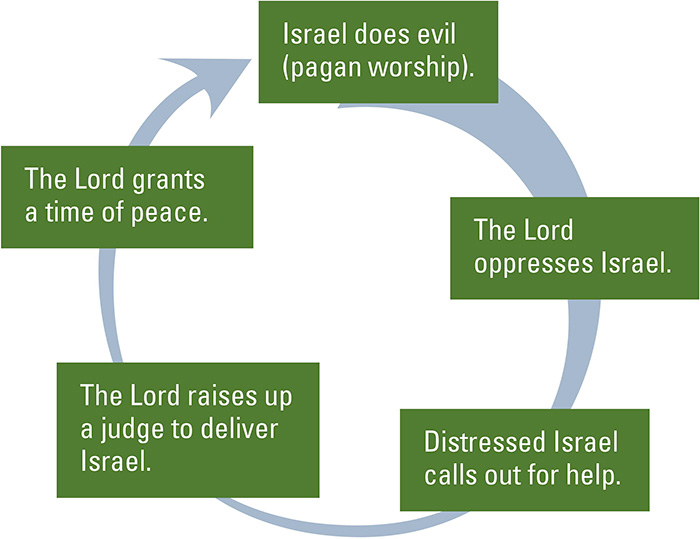

Deborah’s Campaign against Sisera and the Canaanite Chariot Army

Rather, it is Barak whom the Lord calls to fight against Sisera and into whose hands (the singular “you” in 4:7, 14 clearly refers to Barak) the Lord promises to give Sisera. This suggests that it is really Barak and not Deborah who is meant to occupy the role of the deliverer judge. That subsequent references to the judges in 1 Sm 12:11 and Heb 11:32 mention only Barak by name but not Deborah also seems to confirm that both Jewish and early Christian traditions view Barak rather than Deborah as the deliverer judge.

4:6–9. When Deborah sends for Barak and commissions him on behalf of the Lord to fight Sisera, Barak makes his acceptance conditional on Deborah’s willingness to go with him (4:6–8). Given the Lord’s clear promise of victory (4:7), Barak’s response seems to betray a lack of faith. This is especially so since, in the Ehud narrative, the similar prospect of the Lord giving the enemy into Israel’s hands (3:28) is sufficient to prompt immediate participation from the people. No wonder, then, that Barak’s response is met with the Lord’s disapproval, such that the honor of capturing and killing Sisera will now go to a woman (4:9).

4:10–16. After recounting the gathering of troops on both sides and Deborah’s rallying cry (4:10–14), the author briefly reports the battle itself in 4:15–16. Although no detail is given regarding how the victory comes about, 5:19–22 suggests that the Lord has sent a heavy rainstorm, thus flooding the Wadi Kishon and rendering Sisera’s iron chariots inoperable as the wheels get stuck in the mud. That may be why even Sisera himself has to flee on foot (4:15, 17).

4:17–24. Sisera’s escape takes him to the tent of Jael, wife of Heber the Kenite (4:17–21). Earlier, in 1:16, it was reported that the Kenites had associated themselves with the people of Judah in the south. But according to 4:11, Heber has moved away from the rest of his people toward the north. He has apparently made a peace treaty with Jabin, whose army Sisera commands (4:17). This friendly relationship thus paves the way for Jael’s offer of hospitality to be accepted without suspicion. Jael’s provision of a blanket, and of milk when Sisera merely asks for water, probably further enhances Sisera’s trust. The irony is that when Sisera instructs Jael to answer in the negative when asked if “a man” is there (4:20), little does he realize that what he means to be a lie actually turns out to be true because the only man in that tent will soon be brutally killed by his hostess (4:21). Thus, Deborah’s prophecy (4:9) is fulfilled, as Barak arrives only to find Sisera already dead by the hand of a woman (4:22). With Sisera dead and his army destroyed, the Israelites build on that momentum until Jabin is finally destroyed as well (4:23–24). [The Roles of Women in the Old Testament]

5:1. The victory likely prompts a national celebration, which may be the setting for the following song (5:1–31). A careful consideration of the content of the song suggests, however, that this may be not merely a hymn celebrating victory but a politically charged attempt to promote participation in wars against foreign oppressors.

The song itself can roughly be divided into two parts, each introduced by a refrain calling on the people to praise the Lord (5:2, 9). In both refrains, the leaders (princes) of Israel are mentioned, along with the people who willingly volunteered themselves for battle. That both calls to praise are prompted by this willing participation of leader and people alike suggests that the focus of the song is not just on the victory but also on the theme of participation.

5:2–5. In the first part, the call for praise (5:2) is followed by a call to foreign kings to listen (5:3). Then 5:4–5 describes the appearance of the Lord in a thunderstorm, apparently marching ahead of his people into battle against the enemy. Storm imagery is commonly associated with the appearance of a deity (e.g., 2 Sm 22:10–15; Pss 68:7–8; 77:16–18; 97:2–5; Is 29:6; Nah 1:3–5). In this case, such imagery appropriately anticipates the heavy rain and the subsequent flooding of the Kishon that contributes to the defeat of Sisera’s army (cf. 5:20–22).

The significance of the Lord’s coming from Seir/Edom in 5:4 is uncertain, but in Dt 33:2 and Is 63:1, the Lord is also depicted as coming from Seir and Edom, with Seir being further connected with Sinai in Dt 33:2. The mention of these southern locations likely reflects an early tradition in which the Lord’s dwelling is believed to lie in the south.

5:6–8. The plight of the people is next described, as village life is portrayed as having ceased and the main roads as having been abandoned (5:6–7). According to 5:8, the root cause of this decimation is that the people have forsaken the Lord and chosen new gods. As the Lord gave his people into the hands of foreign oppressors in judgment, war came to the city gates, where an army would have gathered before marching out. That there is neither shield nor spear among Israel’s army speaks both of the desperation of the situation and of the valor of those who would still volunteer themselves for battle. No wonder, then, that 5:8 is followed immediately by the refrain in 5:9.

5:9–11a. The second part of the song begins with another call to praise prompted by the willing participation of leaders and people (5:9). This is followed in 5:10–11a by an exhortation to travelers passing by—both the ruling class, who would ride on donkeys (cf. 10:4; 12:14), and commoners, who would walk on foot—to consider the message of the singers at the watering places. The fact that the message to be considered concerns the righteous acts not only of the Lord but also of his warriors in Israel again suggests that the overall focus of the song is on both the Lord’s intervention on behalf of his people and the role the people play in battle. The actual account of such acts then follows in the rest of the song.

5:11b–17. The recitation begins with the Lord’s people going down to the city gates to join the battle (5:11b, 13). This is followed by a roll call that includes the participating tribes (5:14–15a) as well as the nonparticipating tribes who chose to stay behind (5:15b–17). Although the impression given in 4:6, 10 is that only Zebulun and Naphtali fought in the battle, apparently other tribes also participated. That the nonparticipating tribes are also listed suggests again that the main concern of the song is not just to celebrate a victory but also to present a polemic against nonparticipation.

Among the list of participating and nonparticipating tribes are two designations that are nontribal: Machir (5:14) and Gilead (5:17). Since the geographic area known as Gilead, covering the mountainous area east of the Jordan, was occupied by Gad and the half tribe of Manasseh, the reference in 5:17 is likely to these one and a half tribes. As for Machir, the clan so named also represents the descendants of a son of Manasseh (cf. Gn 50:23; Nm 26:9). Since Gilead in 5:17 already includes the Manassites who settled east of the Jordan, the reference to Machir in 5:14 probably refers to those who have settled west of the Jordan. The use of Machir and Gilead thus likely serves to distinguish the two halves of Manasseh, who took different stances with regard to war participation.

Thus, according to this roll call, five and a half tribes—Ephraim, Benjamin, the western half of Manasseh, Zebulun, Issachar, and Naphtali (actually not mentioned until 5:18)—participated, while four and a half tribes—Reuben, Gad and the eastern half of Manasseh, Dan, and Asher—did not. When this is compared to the support Ehud received from all Israel (3:27), one can discern the beginning of a trend of deterioration. Subsequent judges will receive even less support from the people as they battle foreign enemies.

5:18–22. In the account of the battle itself, not only is the contingent from Zebulun and Naphtali depicted as having fought valiantly to prevent foreign kings from carrying off plunder (5:18–19), but forces of nature apparently also joined in to wreak havoc for the enemy’s horses (5:20–22). This involvement of the natural forces thus speaks of the Lord’s intervention on behalf of his people, thereby making it inexcusable for any Israelite not to participate as well.

5:23–24. The song returns to the theme of participation versus nonparticipation as the city of Meroz is singled out and its people twice cursed because they did not participate in the Lord’s battle (5:23). In contrast, Jael is twice called most blessed (5:24), apparently for her involvement in killing Sisera, the details of which follow in 5:25–27.

5:25–31. Functionally, 5:25–27 seems to be a hinge paragraph, as it connects both with the immediately preceding verse to explain Jael’s blessedness and also with the following section (5:28–30) to offer a contrast with Sisera’s mother. For, 5:25–27 and 5:28–30 both focus on a woman in relation to Sisera. If Jael’s offer of milk (5:25) is meant to portray her as a mother figure, then here is a mother figure who kills, in contrast to the description of Sisera’s real mother, who waits in vain for her son to return (5:28). But ironically, it is the mother figure who kills that is praised, while the real mother who waits is taunted. For 5:31a has effectively cast the real mother among the enemies of the Lord, while by her action, Jael has proven herself to be among those who love the Lord.

The entire narrative about Barak and Deborah then concludes with the note that the land had peace for forty years (5:31b).

E. Gideon (6:1–8:35). 6:1–6. The cycle is to begin anew when Israel again does evil in the eyes of the Lord (6:1a). This time, the Lord hands his people over to a coalition led by the Midianites, who for seven years have impoverished them through regular pillaging of crops and livestock (6:1b–5). As expected, Israel cries out to the Lord (6:6).

More and more, the Israelites do what is right in their own eyes (Jdg 17:6; 19:24; 21:25) and what is wrong in the eyes of the Lord (Jdg 2:11; 3:7, 12; 4:1; 6:1; 10:6; 13:1).

6:7–10. Whereas in previous cycles Israel’s cry was met almost immediately with the raising up of a deliverer judge (3:9, 15; 4:3, 6–7), this time, the Lord sends a prophet to rebuke the people for their ingratitude and disobedience, evident in their worship of foreign gods. One can sense the Lord’s increasing frustration with his people’s repeated waywardness, something that will become even more apparent at the beginning of the Jephthah narrative in 10:10–16.

6:11–24. Nonetheless, an angel of the Lord, who turns out to be the Lord himself (cf. 6:14), appears to Gideon. The Lord affirms to Gideon his presence and addresses him as a mighty warrior (6:11–12). But Gideon merely questions why, if the Lord is indeed present, Israel has not experienced the kind of miraculous deliverance known during the exodus (6:13). In response, the Lord commissions Gideon to save Israel out of Midian’s hand (6:14). But Gideon simply stresses his clan’s weakness and his own insignificance (6:15).

To counter Gideon’s protestation, the Lord reiterates his presence, but Gideon still demands a sign (6:16–18). Not until the angel disappears, after causing fire to flare from a rock to consume the offering Gideon brought, does Gideon realize he has been in the presence of the divine (6:19–22). Upon assurance from the Lord that he will not die even though he has seen the angel face to face, perhaps to commemorate the Lord’s declaration of peace (6:23) Gideon builds an altar to the Lord and names it “The LORD Is Peace” (6:24).

6:25–32. That same night comes Gideon’s first mission, as the Lord commands him to tear down the idolatrous Baal altar and Asherah pole his father sponsored for the community. In their place, Gideon is to build a proper altar to the Lord and offer a bull as burnt offering (6:25–26). Although Gideon does as he is told, because he is afraid of his family and the men of the community he carries out his mission under the cover of night (6:27). This betrays a lack of faith, as his previous and subsequent need for signs also seems to confirm.

The following morning, when the townsfolk discover what has been done and that the perpetrator is Gideon, they demand his death (6:28–30). Gideon himself seems strangely absent in this episode, and it is left to his father, Joash, to save Gideon as Joash challenges Baal to contend for his own altar (6:31). Reflecting this challenge, Gideon is also called Jerubbaal, meaning “Let Baal contend with him” (i.e., Gideon) (6:32).

6:33–35. As enemies from the east cross the Jordan and camp at the Valley of Jezreel, the Spirit of the Lord comes upon Gideon, prompting him to summon the necessary troops in preparation for battle (6:33–34). Positive responses come from three northern tribes—Asher, Zebulun, and Naphtali—as well as Gideon’s tribe, Manasseh (6:35).

6:36–40. At this point, instead of moving forward boldly, Gideon again manifests a lack of faith. Even though he is aware that the Lord has promised to save Israel by his hand (6:36; cf. 6:16), Gideon needs further assurances. After asking for a sign and receiving confirmation from the Lord as his piece of fleece becomes wet while the surrounding ground remained dry (6:37–38), Gideon asks for the reverse to happen, probably to make sure that the previous sign was not caused naturally by the sun evaporating the dew on the ground faster than the dew that had saturated the fleece (6:39). The Lord graciously accommodates the second request (6:40).

7:1–8. Having been assured, Gideon sets up camp almost directly south of the Midianites (7:1). But before battle commences, the Lord has further instructions regarding the number of Gideon’s troops (7:2–8). Concerned that in the aftermath of the impending victory, Israel will boast of its own strength rather than the Lord’s deliverance, the Lord wants the number of troops reduced so that it will be clear to all that the credit for the victory is entirely his (7:2). So the Lord tells Gideon to let all who fear to return home, and the number of troops goes from thirty-two thousand to ten thousand (7:3). But this is still too many in the Lord’s estimate. So a second round of elimination takes place by a stream in which 9,700 who knelt to drink are sent back, leaving only three hundred, who lapped water like a dog (7:4–8).

Here, although many have offered explanations for why those who lapped are chosen over those who kneeled—much of the speculation has to do with the alertness of the soldiers as reflected by their drinking pose—the text itself is silent on the matter. Since the main issue here is the number of troops and not the quality of the soldiers, perhaps the only reason why the lappers are chosen over the kneelers is that there are fewer of them (note in 7:4 that the group to be chosen is not specified beforehand). For if the victory is to be entirely the Lord’s doing, then what kind of soldiers are involved is really immaterial.

7:9–14. The night before battle, the Lord, probably because he is aware of Gideon’s propensity to fear especially in light of the drastic troop reduction, takes the initiative to offer Gideon a final reassurance. Having affirmed once again that he will give the Midianites into Gideon’s hands (7:9), the Lord then tells Gideon to go down to the enemy camp to receive further encouragement. Notice, however, that this instruction to go down is an option to be exercised only if Gideon is “afraid to attack” (7:10). That Gideon chooses to exercise this option (7:11) thus indicates his insufficient faith in spite of the Lord’s repeated promises (see 6:16; 7:7, 9). It is only after he has gone down to the enemy camp and heard even the enemy affirming the same promise the Lord has already made to him (7:12–14) that Gideon finally worships God and is ready to fight.

The spring of Harod, beside which Gideon camps with his troops in Jdg 7:1

7:15–18. When Gideon returns to the Israelite camp, he gives his troops specific instructions for battle. The strategy is unconventional, as Gideon’s three hundred men are equipped primarily with trumpets and empty jars with torches inside them (7:15–16). But this is the Lord’s battle, since he has purposely pitched an army of three hundred against a coalition innumerable and like swarms of locusts (cf. 7:12).

Curiously, however, Gideon includes his own name in the battle cry, as he instructs his troops to shout “For the LORD and for Gideon” at the designated moment (7:17–18). Considering that after Midian is defeated the Israelites invite Gideon and his descendants to “rule over” them because they see him as the one who has saved them out of the hands of Midian (8:22), one has to wonder if the inclusion of Gideon’s name on the same level as the Lord’s in the battle cry contributes to Israel’s eventual misattribution of credit to Gideon alone. This is even more ironic in light of the fact that the Lord’s explicit aim in reducing the troops earlier was to ensure that the credit due him would not be usurped by another (7:2).

7:19–25. The unconventional battle strategy proves to be entirely successful, and the Midianites flee, probably taking the noise and light to be indicative of a much larger Israelite contingent (7:19–21). In the process, the Lord confuses the Midianites and their allies, and they end up attacking each other (7:22).

As the Israelites pursue, Gideon sends word to the Ephraimites, asking them to block the fords of the Jordan so that the enemy will not be able to escape back to their eastern homeland (7:23–24). The Ephraimites are thus able to capture and kill two Midianite generals (7:25), although two Midianite kings and some of their troops manage to escape.

8:1–3. After killing the two generals, the Ephraimites launch a strong complaint against Gideon for failing to involve them earlier (8:1). But Gideon credits the Ephraimites with the more significant accomplishment, and a potential internal conflict is averted (8:2–3).

8:4–17. As Gideon and his three hundred men continue to pursue the escaped Midianite kings east of the Jordan, he seeks help from two Israelite towns, Succoth and Penuel. Each, however, refuses to help, and in response, Gideon threatens punishment on his return (8:4–9). Indeed, after successfully capturing the two Midianite kings (8:10–12), Gideon makes good on his threat and returns to the two uncooperative towns. He threshes the elders of Succoth with thorns and briers and also tears down the tower of Penuel, as he earlier promised (8:13–17a; cf. 8:7, 9). But he also kills the men of Penuel (8:17b), something that seems excessive, especially when compared to Deborah and Barak’s mere verbal rebuke of those who had similarly refused to help (cf. 5:15–17, 23). But the trend will only worsen, as Jephthah later slaughters forty-two thousand Ephraimites over the similar issue of noncooperation (12:1–6).

8:18–20. Gideon then turns his attention to the two captured kings. Having asked about the men they killed at Tabor and received confirmation that they were his brothers, Gideon exacts revenge by executing the two kings, but not before telling them that, had they spared his brothers, he would have spared them (8:18–19). Here, Gideon clearly means what he says, as his statement is accompanied by a most serious oath formula invoking the personal name of the Lord. But if so, his statement is problematic in at least two ways.

First, even from the beginning of conquest, the standard practice seems to have been the killing of defeated enemy kings, be it in battle or in its aftermath (cf. Dt 2:32–33; 3:3; Jos 8:29; 10:22–26, 28, 30, 33, 37, 39, 40; 11:10, 12). Within Judges, Adoni-bezek’s death in 1:7 could very well represent this kind of execution. In fact, even in the period of the monarchy, both Saul’s sparing of the Amalekite king Agag in 1 Sm 15 and Ahab’s sparing of the Aramean king Ben-hadad in 1 Kg 20:29–43 result in judgment from the Lord. This means Gideon actually has no legitimate basis to consider sparing the two Midianite kings.

Second, Gideon’s statement also reveals that his pursuit of the two kings may have been motivated more by personal vendetta than a desire to deal the nation’s enemy a decisive defeat. This makes one wonder if Gideon’s punishment of the two uncooperative towns is not also motivated similarly by personal revenge. In hindsight, his openness to sparing the two Midianite kings makes his killing of the men of Penuel even harder to justify.

8:21–22. After executing the two kings, Gideon takes the ornaments off their camels’ necks (8:21). This curious detail is significant in that such ornaments, along with the pendants and purple garments mentioned in 8:26, were status symbols often associated with royalty. Perhaps not coincidentally, Gideon’s interest in such items is followed immediately by the report of the people’s offer of kingship to him (8:22).

Admittedly, kingship is never explicitly mentioned in the people’s offer. But the verb “to rule over” (Hebrew mashal) is often associated with kingly rule (cf. Jos 12:2, 5; 1 Kg 4:21; 2 Ch 7:18). In fact, in Jdg 9:2, Abimelech persuades the Shechemites to let him “rule over” them, and as a result, they make him king (Jdg 9:6, 16). Furthermore, Israel’s offer to Gideon is for a dynastic rule that passes from father to son, and this suggests royalty since the office of judge was not passed down this way (cf. Jdg 12:9–11).

8:23–26. To such an offer, Gideon dutifully declines, declaring piously that only the Lord should rule over them (8:23). His declaration notwithstanding, there are numerous indications that Gideon actually does harbor kingly ambitions. After all, he seems to covet royal paraphernalia and takes them for himself (8:26; cf. 8:21). Some also understand his asking for gold earrings (8:24) as a request for tribute, which was the privilege of kings. This accumulation of wealth, together with having many wives and concubines (8:30–31), is also a decidedly kingly trapping, against which the Lord already warned in the rules he laid for Israelite kingship (cf. Dt 17:17). Finally, the fact that Gideon personally names one of his sons Abimelech (8:31), meaning “My father is king,” also hints at his kingly ambition. This is why some scholars actually see Gideon’s answer not so much as a decline of Israel’s offer but as an acceptance couched in pious clichés. But regardless of whether Gideon actually accepts the offer, his seventy sons apparently do end up ruling (mashal, as in 8:22–23) in Gideon’s place after his death (cf. Jdg 9:2).

Ancient gold earrings. Gideon’s soldiers each give him a gold earring they have taken from the slain Ishmaelites (Jdg 8:24–26).

8:27. Regarding the manufacturing of the golden ephod, it should be noted that an ephod was originally an item of clothing worn by those in priestly offices. There is also a tradition in which the ephod had a special function in relation to oracular inquiries (1 Sm 23:6, 9; 30:7). Although the text is silent on Gideon’s motive for manufacturing the golden ephod, it seems reasonable to speculate that it may be to establish his hometown as an alternative worship center where people can inquire of the Lord. However, this ill-advised move ends up ensnaring both Gideon’s family and all Israel, as the golden ephod turns into an object of idolatry.

8:28–35. The narrative about Gideon ends with a summary of his major accomplishment, the years of peace under his judgeship, and notes about his family and his place of burial (8:28–32). This is followed by further comments on the people’s spiritual state (8:33–35), with special attention to their apostasy and their failure to show covenant faithfulness to Gideon’s family. This last point then introduces the following narrative, which details Israel’s lack of covenant faithfulness.

F. Abimelech (9:1–57). 9:1–6. The narrative begins with an account of Abimelech’s rise to power. As indicated in 8:31, Abimelech is a son of Gideon by his Shechemite concubine. Going to his relatives in Shechem, Abimelech asks the city’s leaders to support him over Gideon’s seventy sons as sole ruler (9:1–2). Seeing that Abimelech has both legitimacy as Gideon’s son and blood relationship with them that Gideon’s other sons lack, the Shechemites throw their support behind Abimelech by providing him with the necessary funds to stage a coup (9:3–4a). Abimelech then hires some reckless fellows and goes back to Ophrah, where he murders his seventy half brothers on a stone (9:4b–5).

The leaders of Shechem and Beth-millo then gather to crown Abimelech king (9:6). Here, although some see the extent of Abimelech’s rule as largely restricted to Shechem and its surroundings, 9:22 suggests that it includes all Israel. After all, Abimelech usurped the power of his seventy half brothers, whose rule had probably included all the territory formerly ruled by their father. Besides, “the Israelites” in 9:55 seems to refer to Abimelech’s followers. Thus, although it is initially the leaders of Shechem and Beth-millo who crown Abimelech king, the rest of Israel may have eventually accepted his leadership as well.

9:7. Jotham, Gideon’s youngest son, somehow escapes the massacre (9:5). When he hears that Abimelech has been made king, he goes up Mount Gerizim just outside Shechem and proclaims a message of rebuke against Abimelech and the Shechemites (9:7–21).

9:8–15. Jotham begins with a fable about trees searching for a king. There is some debate as to whether the fable is against the idea of monarchy in general or only speaks to the particular situation concerning Abimelech and the Shechemites. Those who support the former interpretation point out that, since the fable suggests that honorable and productive people have no desire to become king, but only the unworthy aspire to it, kingship must therefore be an inherently bad idea. While such a reading is possible, it is more likely that by casting Abimelech as the bramble (9:14) and the Shechemites as trees looking for a king, Jotham is making the point that those who are foolish enough to choose an unworthy candidate as king should be wary of the destructive potential of their choice.

In the fable, the bramble boastfully demands that the other trees take refuge in its shade to show their sincerity (“really,” Hb emet [9:15]). Otherwise, it threatens to let fire come out to consume even the cedars of Lebanon.

9:16–21. Playing on the word emet and using it in a slightly different sense to mean “faithfully” in 9:16 (also 9:19), Jotham then sarcastically wishes both parties mutual happiness if the Shechemites have indeed acted with emet in making Abimelech king (9:16–19). But accusing them of not having done so since they sponsored the murder of Gideon’s seventy sons even though Gideon has delivered them from Midian’s oppression, he curses them with mutual destruction by fire, and then quickly makes his escape (9:20–21).

9:22–24. The rest of the narrative then focuses on how Jotham’s curse is fulfilled, as the Lord brings just retribution to both Abimelech and the Shechemites (9:22–57).

After Abimelech has governed Israel for three years (9:22), the Lord sends an evil spirit between Abimelech and the Shechemites in order to repay both for their roles in the murder of Gideon’s sons (9:23–24).

9:25–29. The conflict begins with the leaders of Shechem placing men in the hills to rob passersby, presumably to enrich themselves at the expense of Abimelech, who apparently does not live in the city (9:25). Matters soon escalate further with the appearance of Gaal (9:26), whose words in 9:28–29 imply that he is a descendant of Hamor, the father of Shechem, after whom the city may have been named (cf. Gn 34). By appealing to closer ties with the city than those of the existing ruler, the tactic Gaal uses to turn the Shechemites against Abimelech is ironically what Abimelech used earlier to turn the Shechemites against Gideon’s seventy sons. In this, one can already sense the outworking of just retribution, as the treachery Abimelech used against his half brothers is now being used against him.

9:30–49. However, Abimelech has a loyal deputy in the city’s governor, Zebul, who reports back to him all that is going on (9:30–33). Upon Zebul’s advice, Abimelech brings along his men, fights, and defeats Gaal (9:34–41). Then he turns against the city that has betrayed him and destroys it, killing its people (9:42–45). This prompts the Shechemites in a nearby tower to go and hide in a stronghold at a pagan temple. But Abimelech sets fire to the stronghold, killing all those inside (9:46–49). Jotham’s curse is thus partly fulfilled, as these Shechemites are literally destroyed by fire (cf. 9:20, 57). Inasmuch as those who helped Abimelech kill his half brothers are now themselves killed by Abimelech, the Shechemites finally receive their just retribution.

9:50–57. As for Abimelech, not until he takes his campaign of revenge to Thebez does he finally meet his just retribution (9:50). Although Thebez is not previously mentioned, Abimelech’s attack on the town suggests that it must have been aligned with Shechem in some way. As the townsfolk there have also locked themselves in a tower, Abimelech decides to use the same strategy he did before by setting the tower on fire (9:51–52). But as he approaches the entrance, a woman drops an upper millstone from above and hits Abimelech on the head, seriously wounding him (9:53). To avoid the shame of being killed by a woman, Abimelech asks his armor-bearer to kill him (9:54). Thus even in the manner of his death, there is poetic justice. For he who killed on a certain stone (9:5) is now killed by a certain woman (9:53; both use the same Hebrew term) dropping a stone on his head. Thus, God finally brings just retribution to all the perpetrators (9:56–57).

In Joab’s report to David in 2 Sm 11:18–21, he references Abimelech’s death in Jdg 9:53–54. This is probably a subtle, yet ironic, comparison of Abimelech’s defeat by a woman to David’s “defeat” by a woman (Bathsheba).

G. Tola and Jair (10:1–5). After the death of Abimelech, 10:1–5 briefly introduces two more judges, Tola (10:1–2) and Jair (10:3–5), commonly referred to as minor judges. Although the minor judges are traditionally considered to have a distinct role from the major judges, as administrators during times of peace, the so-called minor judges may also have served a military function. (See the article “The Minor Judges versus the Major Judges.”) [The Minor Judges versus the Major Judges]

H. Jephthah (10:6–12:7). 10:6–9. The new cycle that begins with sin, oppression, and crying out to the Lord is again reported in 10:6–16, but with greater detail than before. The “evil” the Israelites commit is clearly specified as apostasy, and the people’s deteriorating spiritual state is highlighted both by the long list of foreign gods they have come to serve and by the explicit statement that they have forsaken the Lord and no longer serve him (10:6). The mention of the Philistines together with the Ammonites in 10:7 as people into whose hands the Lord has sold Israel perhaps anticipates also the Samson cycle. In the narrative featuring Jephthah, however, the focus is on the Ammonites. In addition, although the Ammonite oppression seems to be most keenly felt by the tribes east of the Jordan, 10:9 makes it clear that the western and southern tribes, such as Judah, Benjamin, and Ephraim, are also affected, so that the crisis is justifiably presented as national.

10:10–16. This time, not only is Israel’s crying out to the Lord reported, but their confession that accompanies their crying out is also quoted (10:10). But instead of immediately providing a deliverer as he did in the Othniel, Ehud, and Barak cycles, the Lord, for the second time, responds with a rebuke (10:11–12). It even comes directly from him rather than through a prophet, as in the Gideon cycle. To make matters worse, the Lord initially refuses to save his people, telling them instead to go and cry out to the various gods they now serve (10:13–14). This leads to a second round of confession from the people, accompanied by concrete action as they get rid of the foreign gods among them and return to the Lord (10:15–16a).

While it may be easy to assume that the Lord’s eventual willingness to save his people indicates that he accepts their repentance, the text suggests otherwise. The Hebrew root qtsr often conveys the idea of being “weary” (10:16b) or impatient (cf. Nm 21:4; Jb 21:4; Mc 2:7; Zch 11:8). Particularly in Jdg 16:16, the word is used in relation to Samson being wearied to death by Delilah’s constant nagging and prodding. Thus, what 10:16 seems to suggest is that the Lord’s eventual action for his people comes not so much out of his acceptance of their repentance but out of compassion regarding their misery or even a sense of weariness from their constant pleading.

This figurine from Tyre, which may represent the Canaanite god Baal as a warrior (1400–1200 BC), is an example of the type of idol that the Israelites rebelliously persist in worshiping.

© Baker Publishing Group and Dr. James C. Martin. Courtesy of the British Museum, London, England.

10:17–18. But instead of waiting for the Lord to raise up a deliverer for them, Israel’s leaders decide to find a deliverer for themselves when the Ammonites are called to arms (10:17–11:11). They initially offer to make anyone willing to lead the attack against the Ammonites the head of all Gilead (10:18), but when no one apparently responds, they approach Jephthah to enlist him for the job (11:4).

11:1–3. In a brief flashback that serves to introduce the new hero, it is disclosed that, as an illegitimate son of Gilead, Jephthah has earlier been driven out by his half brothers over inheritance issues (11:1–2). This apparently happened with the blessing of the elders of the community (cf. 11:7). He then settled in Tob, where he gathered around him a group of ruffians and likely made a living from raiding (11:3). He must have made quite a name for himself, thus explaining why the elders of Gilead turn to him when no one else takes up their open offer.

11:4–11. In approaching him, the elders initially seem uncomfortable with the idea of making Jephthah head of their people. Thus, they only offer to make him commander, a military office clearly inferior to that of “head” of the people (11:6). Whether or not Jephthah knows about the earlier open offer is uncertain, but clearly considering the elders’ offer insufficient, Jephthah does not respond favorably (11:7). The elders thus revise their offer, this time agreeing to make him head of Gilead (11:8). With that, Jephthah finally agrees to go with them (11:9). As the Gileadites make Jephthah both head and commander over them, Jephthah solemnizes the agreement before the Lord at Mizpah (11:10–11).

Notice that unlike Gideon, who initially had doubts about his own ability to deliver Israel, Jephthah shows no such reservations. At a time when Israel is oppressed by the Ammonites, what these negotiations show is that, unlike the judges before him, Jephthah, in his final consent to play the role of deliverer, is mainly motivated by self-interest rather than a concern for the people’s suffering. This theme of a judge increasingly acting out of self-interest, which first surfaced with Gideon (see 8:18–20), continues through Jephthah and will eventually culminate with the final judge in the book, Samson.

11:12–13. Jephthah’s back-and-forth dialogue with the Ammonite king through messengers is reported in 11:12–28. While this may appear to be some form of negotiation, Jephthah’s words are not conciliatory and may actually be more a challenge to war. In response to Jephthah’s inquiry into the reason behind the hostility (11:12), the Ammonite king accuses the Israelites of having taken his land when they first came out of Egypt (11:13). Specifically, the land in question is the area occupied by Reuben and Gad between the rivers Arnon and Jabbok east of the Jordan.

11:14–28. Jephthah’s lengthy reply essentially consists of four points. First, he maintains that when Israel came out of Egypt, she did not take any of the land belonging to the descendants of Lot or Abraham, such as the Moabites, Ammonites, and Edomites (11:15–18). Second, he argues that the land in question was actually taken from the Amorites, as the Lord gave the Amorite king Sihon and his army into Israel’s hands when they attacked Israel (11:19–22). Third, Jephthah asserts that since Israel’s God has given that land to his people, and since that land has been in their possession for three hundred years without Ammon ever having challenged that right, Israel will continue to keep that land just as Ammon will keep what their god has given them (11:23–26). Notice that in so saying, Jephthah is not affirming the reality or authority of the Ammonite god. After all, he is involved in a dispute with war implications and is not conducting a theological debate. Therefore, he may simply be using language his opponent will understand to make a point. Fourth, having made that point, he warns that as the Ammonites’ hostility was uncalled for, they should beware that the Lord, who is the ultimate judge, will decide the dispute (11:27).

11:29–31. When the Ammonite king chooses not to respond any further (11:28), Jephthah takes active steps to prepare for war (11:29–31). As the Spirit of the Lord comes upon him, he crosses Gilead and Manasseh, presumably to mobilize his troops (11:29). But 11:30–31 also records a vow he makes to the Lord, promising to sacrifice as burnt offering whoever comes out of his house to meet him when he returns safely from war. Even though Jephthah certainly does not expect the victim to be his daughter, he seems to assume that a human being will be sacrificed. If so, this indicates two things.

First, Jephthah has apparently allowed pagan religious practices to exert a stronger influence on him than the clear stipulations of the Mosaic law (cf. Dt 12:31; 18:10). Second, to make such a high-staked vow on the eve of battle, even after the Spirit of the Lord has come upon him, betrays a desperation that points to a lack of faith. And to the extent that he is willing to put at stake a human life, whereas Gideon only asks for signs involving pieces of fleece, one can argue that Jephthah’s lack of faith represents a deterioration from Gideon.

11:32–33. The battle itself and the subsequent victory against the Ammonites are described with surprising brevity, and the focus promptly shifts to Jephthah’s homecoming.

11:34–40. The tragedy is highlighted in 11:34, when Jephthah’s unnamed daughter, described as an only child, comes out dancing in celebration of her father’s return, oblivious to the vow that will soon doom her. No wonder, then, that Jephthah reacts with great distress when he realizes what he has done (11:35). But the daughter, perhaps showing a greater awareness of the demands of the law than her father, urges him to fulfill his vow, using language that echoes Nm 30:2, as she tells him to “do to me as you have said” (11:36). All she asks for is two months, so that she can mourn with friends the fact that she will never have the chance to experience married life (11:37). He grants her request, which subsequently gives rise to a custom in which every year, Israelite women commemorate Jephthah’s daughter for four days (11:38–40).

12:1–7. Whether the events recorded in 12:1–7 happen before or after the sacrifice of Jephthah’s daughter is uncertain. But in the aftermath of the Ammonite war, the Ephraimites cross over the Jordan to complain to Jephthah, just as they did earlier to Gideon (8:1), about not having been asked to participate in the war. This time, they even threaten to burn down Jephthah’s house in retaliation (12:1). But while Gideon answered diplomatically to avert an internal conflict, Jephthah, who has earlier shown a willingness to patiently dialogue with the enemy (11:12–28), simply counteraccuses the Ephraimites of refusing to help when asked and calls out the Gileadites to fight them (12:2–4).

Using the same strategy Ehud (3:28) and Gideon (7:24) used when fighting enemies who had crossed over from the other side of the Jordan, Jephthah has his troops cut off the point of crossing at the Jordan to prevent the Ephraimites from returning to their home base. Then, using a dialectal peculiarity (the pronunciation of “Shibboleth”) to determine tribal identity, Jephthah has forty-two thousand Ephraimites killed (12:5–6).

From this, one can see that the tendency toward internal conflict that first emerged with Gideon (8:1–17) has now escalated in both scope and intensity with Jephthah, until it eventually culminates in the slaughter of almost the entire tribe of Benjamin in the civil war recorded in 20:12–48.

Note also the absence of any mention of years of peace as the Jephthah narrative comes to a close in 12:7. Thus, the cyclical structure that characterizes the narratives of the major judges is also breaking down as the overall narrative continues.

I. Ibzan, Elon, and Abdon (12:8–15). Ibzan, Elon, and Abdon are three of the so-called minor judges. (On the minor judges, see the article “The Minor Judges versus the Major Judges” near Jdg 10.) Note here that the Bethlehem with which Ibzan is associated (12:8) is likely not the famous Bethlehem in Judah but a city of the same name located within the territory of Zebulun (cf. Jos 19:15). For within the book, the other Bethlehem is almost always referred to specifically as Bethlehem of Judah (cf. Jdg 17:7–9; 19:1–2, 18).

J. Samson (13:1–16:31). 13:1–5. After another note of the Israelites doing evil in the eyes of the Lord and the Lord giving them into the hands of the Philistines (13:1), the narrative of the final judge begins somewhat unusually, with his birth narrative (13:2–25). The announcement of miraculous birth to a barren woman is a familiar biblical theme (cf. Gn 18:9–15), and the careful instructions given by the angel to Manoah’s wife further heighten the expectation that the child to be born will be special. Specifically, it is disclosed that the child is to be a Nazirite from the womb, and his mission will be to begin the deliverance of Israel from the Philistines (13:4–5).

Regarding the Nazirite status, a comparison of the instructions given by the angel with the Nazirite rule in Nm 6:1–21 shows both similarities and differences. The similarities include the prohibitions against fermented drinks and the cutting of hair. The differences involve the involuntary nature, and hence, the permanency of the Nazirite status, as well as the stipulation against unclean food. For according to Nm 6, the Nazirite vow is normally a voluntary vow that is binding only for a specific period. In Samson’s case, however, he is set apart involuntarily, while still in his mother’s womb, a fact evident through the requirement of the mother to also not drink fermented drink or eat unclean food for the duration of the pregnancy, presumably to safeguard the Nazirite status of the son in her womb. As for the duration of this Nazirite status, unlike those who would take the vow voluntarily, for Samson, it seems to be permanent. At least this is how Samson’s mother understands it, for she states in 13:7 that Samson will be a Nazirite of God from the womb until his death.

In addition, while one of the stipulations the angel specifies involves prohibition against unclean food, such a prohibition is not found in Nm 6. Instead, Nm 6 emphasizes avoiding contact with the dead. But as different as these two stipulations seem to be, both essentially concern ceremonial cleanliness (cf. Nm 6:7). Since Samson’s mission as a deliverer who will most likely kill in combat effectively renders it impractical for him to stay away from dead bodies, the stipulation against unclean food may represent an attempt to highlight the continued necessity for ceremonial cleanliness notwithstanding the nature of his mission.

13:6–23. After her encounter with the angel, the woman goes and tells her husband about her experience (13:6–7). Manoah, perhaps wanting to confirm the matter for himself, prays for the man of God to appear to him (13:8). The angel does, and after he confirms to Manoah what was said earlier to his wife, Manoah offers to prepare a meal for him, not realizing he is an angel (13:9–15). In a scene reminiscent of Gideon’s encounter with the angel of the Lord (6:20–23), it is only after flame blazes from the altar and the angel goes up with the flame that Manoah realizes he has seen an angel (13:16–21). Like Gideon, he also fears for his life, until his wife convinces him they will be safe (13:22–23).

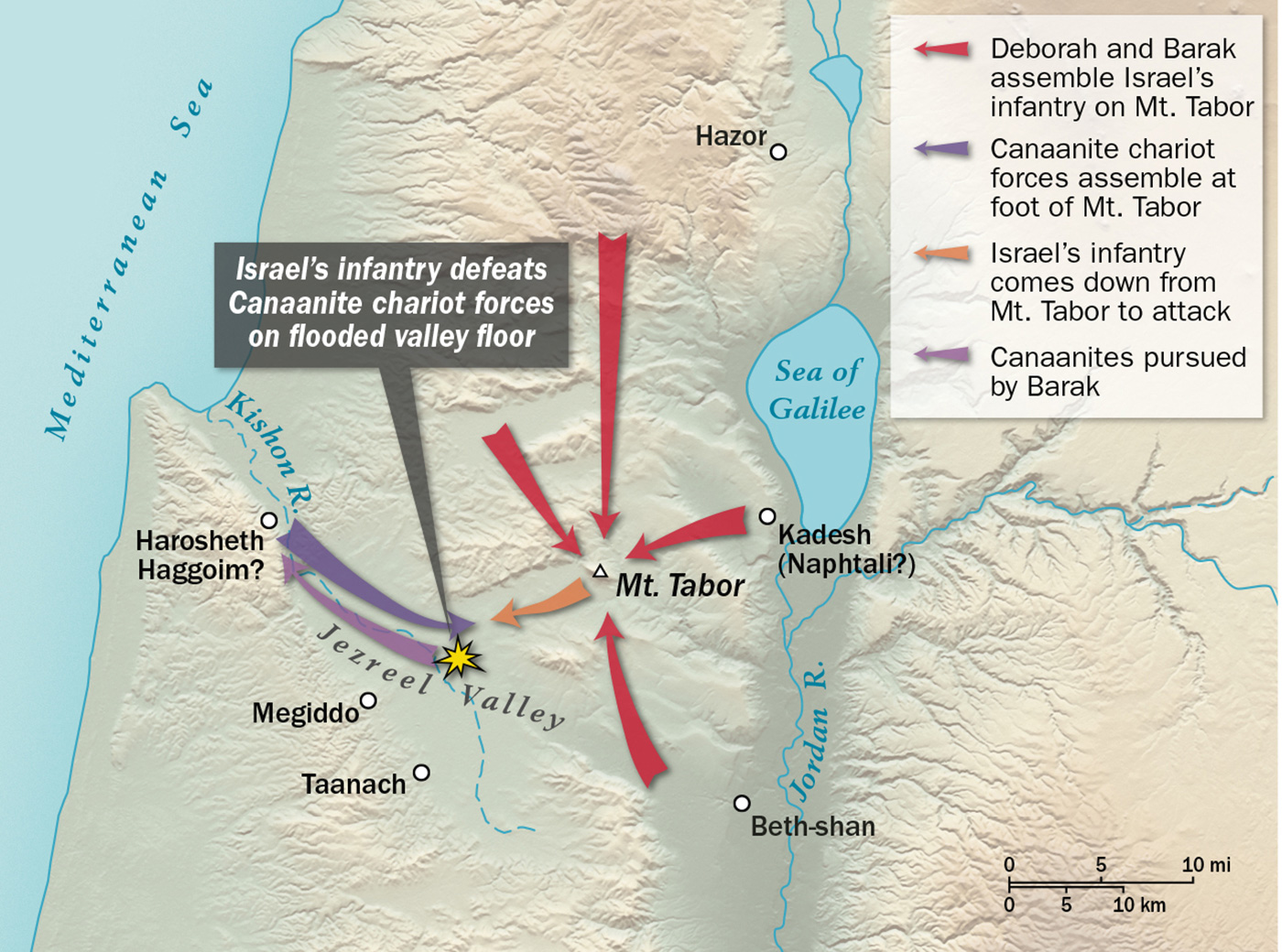

The Places of Samson’s Exploits

A decorated Philistine jug, probably used for serving beer

© Baker Publishing Group and Dr. James C. Martin. Courtesy of the British Museum, London, England.

13:24–25. The wife eventually gives birth to Samson, and it is immediately reported that the Lord blesses him as he grows up (13:24), and the Spirit of the Lord begins to stir in him (13:25). All these only heighten expectations of greatness. But such expectations are immediately put to the test, as chapter 14 recounts the events surrounding his near marriage to an unnamed Philistine woman.

14:1–3. Having noticed the Philistine woman in Timnah, Samson goes to his parents demanding that they get her for him as a wife (14:1–2). The parents, alarmed that he wants to marry a non-Israelite who belongs to the occupying power, try in vain to suggest that he find someone from among their own people (14:3a). But Samson is insistent, and echoing an expression that will eventually appear again in the epilogue’s refrain (cf. 17:6; 21:25), he justifies his request by declaring that the woman seems “right” to him (14:3b).

14:4. Given the blatant disapproval of marriages with foreigners already expressed in 3:5–6, it seems obvious that Samson’s desires in this matter should be viewed negatively. But the supplementary information provided by the narrator, that Samson’s parents are ignorant of the Lord’s plan to seek an occasion against the Philistines (14:4), suddenly seems to cast that evaluation in doubt. Is Samson right to seek a marriage alliance with the Philistines?

To answer the question, one should consider the following. First, that the Lord has planned to use Samson’s proposed marriage as an occasion to strike the Philistines does not necessarily imply his approval of Samson’s action (cf. Gn 45:5–8 and 50:19–20; God’s plan to preserve many overlapped Joseph’s brothers’ plan to harm him, but that clearly does not mean God approved of their wicked deeds). Second, the point of the narrator’s comment may be precisely to highlight the Lord’s determination to deliver his people in spite of Samson. Finally, the fact that the narrator needs to supply this extra information is proof itself that the readers are expected to agree with the parents’ perspective. The comment is therefore designed not so much to exonerate Samson but to further clarify why Samson is allowed to continue this undesirable course of action.

14:5–7. At Samson’s insistence, his parents give in. As Samson goes down to Timnah again, presumably to seek the woman’s hand in marriage, a young lion attacks him just as he is approaching the vineyards (an ominous note since a Nazirite is supposed to avoid any product of the vine). But the Spirit of the Lord comes upon him, and he tears the lion in two with his bare hands (14:5–6). When he reaches Timnah, he speaks to the woman, who, for the second time (see 14:3), is described as someone who “seemed right to Samson” (14:7).

14:8–9. Having returned home, Samson makes another trip down to Timnah to marry the woman. At the place where he previously killed the lion, he finds inside its carcass a swarm of bees and some honey, which he scoops up and eats (14:8). He even brings some back with him for his parents, who, ignorant of the source of the honey, eat it as well (14:9). In so doing, Samson both violates his Nazirite status by eating unclean food and also brings ritual defilement to his parents, as food contaminated by a carcass is considered unclean even to ordinary Israelites (see Lv 11:39–40).

14:10. But not only does Samson violate the food stipulation of his status, he also appears to violate the stipulation against fermented drink. In 14:10, he is said to have “prepared a feast there, as young men were accustomed to do.” In those days, wine and fermented drink were commonly served at such feasts. In fact, the Hebrew words for “wine” and “beer” found in the stipulations for Nazirites (Nm 6:3–4) and for Samson (Jdg 13:4, 7, 14) are explicitly associated with the word for “feast” elsewhere in the OT (1 Sm 25:36; Is 5:12; Jr 51:39; cf. Est 5:6; 7:2, 7, 8; Dn 1:16). If Samson conducted himself as was customary for bridegrooms of his day, then he would certainly have consumed such drinks.

14:11–20. Caught up in the festivity of the occasion, Samson challenges his thirty Philistine groomsmen to a timed riddle with the wager set at thirty sets of clothing (14:12–13). Since the riddle involves Samson’s earlier experience of eating honey out of the lion’s carcass, the groomsmen obviously cannot guess the answer (14:14). So they threaten Samson’s wife-to-be with death, and she, in turn, keeps nagging Samson until he gives in and tells her the answer (14:15–17a). She then reveals the answer to the groomsmen, who naturally win the bet (14:17b–18). Samson, realizing that he has been betrayed by his wife-to-be and not having the means to pay the wager, then goes down to Ashkelon, kills thirty Philistines, and takes their clothes to pay up. Then without consummating his marriage, he angrily returns to his father’s house (14:19). With the groom gone, the bride is given to one of the groomsmen instead (14:20).

15:1–2. The narrative unit in chapter 15 recounts the series of events that takes place in the aftermath of the failed marriage. Having had time to calm down, Samson returns to the house of his would-be wife with a gift, apparently wanting to continue the relationship from where he has left off (15:1). Although the mention of the wife’s room does not necessarily imply physical intimacy, the response of the father-in-law, first refusing to let him in, then explaining that the woman has already been given to another, and finally offering the supposedly more beautiful younger daughter as replacement, suggests an understanding that Samson wants to consummate the marriage (15:2).

15:3–8. Having been rebuffed, Samson angrily promises revenge on the Philistines and then sets on fire their entire harvest (15:3–5). This is particularly devastating as it is the time of the harvest (cf. 15:1), which means that the Philistines’ months of hard work are now in vain. When the Philistines discover that Samson was behind the deed, they take it out on the would-be wife and her father by burning them to death (15:6). This prompts an angry Samson to seek further revenge by slaughtering many Philistines (15:7–8).

15:9–11. This causes the Philistines to demand more revenge, as they go up to Judah and set up camp (15:9). Sensing trouble, representatives from Judah inquire about the reason for the Philistines’ military presence (15:10). Having discovered that it is related to Samson, three thousand men from Judah go to Samson’s hiding place to confront him (15:11). From their words, it is clear that by then, these Israelites from Judah have become content to be ruled by the Philistines, such that they prefer keeping the status quo peacefully rather than upsetting their overlords for any reason. Can this be why no report is made of the people crying out to the Lord when the Philistine oppression is introduced in 13:1? Thus, another stage of the cyclical structure that characterizes the narratives of the major judges has quietly broken down.

15:12. Not only are these men from Judah content to live under Philistine rule, they are even ready to side with their oppressors, as they inform Samson that they will tie him up and hand him over to the Philistines. In this, the theme of Israelites refusing to stand with their judges, which first emerged with Deborah and Barak (Jdg 5) and continued with Gideon (8:4–17) and Jephthah (12:1–7), has reached its nadir.

15:13–17. Having made them promise not to kill him, Samson allows himself to be tied up (15:13). But as he is about to be handed over to the Philistines, the Spirit of the Lord comes upon him, such that the ropes that tie him melt away (15:14). Finding the jawbone of a donkey, Samson uses it to kill a thousand Philistines (15:15–16). This results in the place being named Ramath-lehi, meaning “Jawbone Hill” (15:17).

15:18. But no sooner has he experienced this great deliverance than Samson prays a prayer that betrays a lack of faith. Interestingly, the circumstances of this prayer seem calculated to remind one of the prayers by Gideon (6:33–40) and Jephthah (11:29–31). For all three prayers are preceded by the coming of the Spirit of the Lord upon the judges, prompting them to take concrete action against the enemy. All three prayers also represent the first utterance the respective judges made to the Lord after the coming of the Spirit. While one would naturally expect these to be prayers of faith, they are, unfortunately, just the opposite.

For Samson, his prayer is essentially for his thirst to be quenched. But the way he phrases his request is manipulative. While acknowledging the great deliverance the Lord has just given him, Samson, however, uses it as a means of coercion, suggesting that the very deliverance will have been in vain if he is allowed to die of thirst and fall back into the hands of the Philistines. In this respect, his prayer compares unfavorably to Gideon’s prayer for signs and Jephthah’s desperate vow. For while the prayers of Gideon and Jephthah are made before their respective confrontations with the enemy, Samson’s manipulative prayer comes after he has just won a great victory. Thus, one can argue that Samson shows even less faith than his two predecessors.

15:19–20. In spite of Samson’s lack of faith, the Lord answers his prayer by opening up a hollow from which water comes, and the spring comes to be known as En-hakkore, meaning “Spring of the Caller” (15:19).

16:1–3. The brief unit in 16:1–3 recounts Samson’s involvement with a prostitute in Gaza, which provides another demonstration of his extraordinary strength. But more important, sandwiched between the narrative involving the Philistine woman he almost marries and the one about Delilah, whom he supposedly loves (16:4), this brief story is likely included to clarify Samson’s root problem. Lest one think that Samson is simply unlucky in love, the presence of this episode suggests that the “love” he seemingly seeks may be no more than the satisfaction of his sexual appetite.

16:4–5. Samson’s downfall through his involvement with Delilah is next recounted in 16:4–22. Although the text does not specify Delilah’s nationality, that she lives in Philistine territory and has connections with the Philistine rulers make it almost certain she is ethnically Philistine. That she lives in the Sorek Valley (16:4) also bodes ill for Samson, for the name means “Choice Vines,” thus suggesting something that should be out of bounds for a Nazirite like Samson.

The Philistine rulers, understanding the futility of their attempt at vengeance unless they can overcome Samson’s extraordinary strength, promise Delilah money for uncovering the secret of his strength (16:5).

16:6–20. The first three times Delilah tries to coax the secret out of Samson, he lies to her, but unable to withstand her constant nagging, he finally gives in (16:6–17). In his final disclosure, Samson is able to explain accurately the significance of his uncut hair, thus suggesting that he must have been aware all along of the circumstances of his birth and the calling with which he has been entrusted. Sadly, he never takes that calling seriously. The secret of his strength having been disclosed, his hair is cut while he is asleep (16:18–19). With the only visible symbol of his Nazirite status now gone, the Lord and his supernatural strength leave Samson (16:20).

16:21–22. After he is captured, Samson’s eyes, which seem to have been a major source of his repeated transgressions (cf. 14:1, 2, 8; 16:1), are gouged out, and he is taken to Gaza and imprisoned (16:21). But foreshadowing what is to come, 16:22 reports that his hair is beginning to grow back.

16:23–31. Celebrating Samson’s capture, the Philistines gather to give credit to their god Dagon for this turn of events (16:23–24). To add insult to injury, they have Samson brought out to entertain them (16:25). Perhaps feigning tiredness, Samson requests to lean on the pillars supporting the temple, and there he prays for strength for one last time (16:26–28). As he pushes hard on the supporting pillars, the temple collapses, killing all who are in it, including himself (16:29–30).

Reconstructed vertical loom. Samson’s strength easily overcame the weaving of his braids into a loom (Jdg 16:13).

Note, however, that consistent with the portrayal of Samson in these narratives, even his final prayer is motivated by personal vendetta, in order to avenge the loss of his eyes. Thus, one can say that everything Samson does against the Philistines is motivated by self-interest rather than a concern for God’s people. Nonetheless, it is reported that he killed more Philistines in death than when he was alive. His body is apparently recovered from the ruins and brought back for burial near his hometown (16:31). [Samson as a Microcosm of Israel]

These column bases in a Philistine temple from the Iron Age (Tel Aviv, Israel) may have supported pillars similar to those knocked down by Samson (Jdg 16:29–30).

© Kim Walton. Courtesy of the Eretz Israel Museum.

3. CHAOS IN ISRAELITE SOCIETY (17:1–21:25)

While the last five chapters of Judges are often referred to as the epilogue of the book, unlike the previous section these narratives feature neither any judge nor any foreign enemy. Instead they concern largely nameless individuals within Israelite society, with a focus on chaos generated entirely from within. Structurally, the cyclical framework of Judges also no longer organizes the epilogue. Instead, the refrain “In those days there was no king in Israel” (17:6; 18:1; 19:1; 21:25) binds together two extended narratives, each featuring a Levite.

Nonetheless, one can discern a continuity between the epilogue and earlier parts of the book. The deteriorating trend regarding internal conflict continues to worsen, culminating in the near annihilation of the tribe of Benjamin in a civil war (20:1–48). And apostasy is also given a closer look in the epilogue, as one family’s syncretistic worship eventually results in the idolatry of an entire tribe (17:1–18:31).

A. In the areas of religious and military practices (17:1–18:31). 17:1–5. The first of two extended narratives begins with the return of some stolen silver by one of only two named characters within the epilogue. The specification of his name (17:1) is probably for ironic purposes, as Micah (meaning “Who Is Like the Lord”) turns out to be an idol worshiper. In any event, after he returns the silver to his mother, likely out of fear for the curse she has placed, the mother invokes a blessing from the Lord, presumably to cancel out her earlier curse (17:2). She then decides to dedicate the silver to the Lord but, bizarrely, to have an idol made (17:3). Note that, although the text speaks of “a carved image and a silver idol,” this may be a figure of speech in which the two actually represent the same thing: a carved image overlaid with molten metal. For the pronoun in the last clause of 17:4 is actually singular in Hebrew; thus, “it was in Micah’s house.” As it turns out, Micah has his own household shrine, which already houses an ephod and some idols (17:5). In addition, he has established his own sons as priests, which is a clear violation of the law, as Micah is an Ephraimite (see 17:1) and Ex 28:41–43 and Nm 25:10–13 stipulate that only a specific group of Levites can serve as priests.

17:6. It is at this juncture that the full refrain “In those days there was no king in Israel; everyone did whatever seemed right to him” appears for the first time. The phrase “everyone did whatever seemed right to him” is likely an allusion to Dt 12:8, where “everyone is doing whatever seems right in his own sight” is specifically prohibited in the context of worshiping the Lord not just anywhere but at the place chosen by him. But while this first appearance of the refrain may be intended to draw attention to Micah’s illegitimate worship, the other appearances of this refrain within the epilogue, be it in full (21:25) or reduced (18:1; 19:1) form, are probably intended to serve as a commentary on the general anarchy of the period.

The identity of the “king” in the refrain is debatable. Many see it as a forward-looking reference to the human kings who will eventually rule over Israel in the monarchic period, but it could also refer to the Lord himself. After all, the Lord’s kingship over Israel is a tradition that was established relatively early in Israel’s history (cf. Ex 15:18; Nm 23:21; Dt 33:5; Gideon’s response in 8:23 also implies an understanding that the Lord is king over the nation).