B Wheelchair-Accessible Trails

If the great outdoors is so great, then why don’t people enjoy it more? The answer is because of the time trap, and I will tell you exactly how to beat it.

For many, the biggest problem is finding the time to go, whether it is hiking, backpacking, camping, fishing, boating, biking, or even just for a good drive in the country. The solution? Believe it or not, the answer is to treat your fun just as you treat your work, and I’ll tell you how.

Consider how you treat your job: Always on time? Go there every day you are scheduled? Do whatever it takes to get there and get it done? Right? No foolin’ that’s right. Now imagine if you took the same approach to the outdoors. Suddenly your life would be a heck of a lot better.

The secret is to schedule all of your outdoor activities. For instance, I go fishing every Thursday evening, hiking every Sunday morning, and on an overnight trip every new moon (when stargazing is best). No matter what, I’m going. Just like going to work, I’ve scheduled it. The same approach works with longer adventures. The only reason I have been able to complete hikes ranging from 200 to 300 miles was that I scheduled the time to do it. The reason I spend 125 to 150 days a year in the field is that I schedule them. In my top year, I had nearly 200 days where at least some of the day was enjoyed taking part in outdoor recreation.

If you get out your calendar and write in the exact dates you are going, then you’ll go. If you don’t, you won’t. Suddenly, with only a minor change in your plan, you can be living the life you were previously just dreaming about.

—Tom Stienstra

Many keep this book in their cars or pickup trucks at all times. It sits dog-eared, often with cryptic notes, on a seat, on the center floorboard or on the dashboard, ready for use. No matter where we each might be on our separate paths, we are both kind of like dogs: We need to go for a walk every day . . . and we share the hope that there is always a trail waiting nearby, always another hike to look forward to.

We’ve selected the best 1,000 trails in California for this book. We have hiked each of them. We have also involved hundreds of rangers, interpretive specialists, and field scouts across the state to review our work to make it as correct as possible as we go to press. Each word has been vetted multiple times. For this edition, we’ve included too many updates to count. If you run across any changes out there on the trail, feel free join our team and drop us a line.

This is the only complete guide to hiking in California. Its range and scope are unmatched. There are many excellent locally focused guidebooks. Both of us have written several. Most hikers love to range both near and far, to explore and make each day a discovery. Put no bounds on your life or what is possible. That is what this book can do for you.

You have the best of California in your hands. We’ve done everything possible to put it within reach.

A wise person once said that a culture can be measured by the resources it chooses to preserve. If that’s true, then California’s parks and preserve are an immense credit to our culture. The Golden State is blessed with an abundance of public land, including more than 25 units of the National Park System, 19 national forests, 137 federally designated wilderness areas, 280 state parks, and thousands of county and regional parks.

This huge mosaic of parklands celebrates California’s diverse landscape, which includes the highest peak in the contiguous United States (Mount Whitney at 14,495 feet or 14,505 feet, depending on which measurement is currently in vogue) and the lowest point in the western hemisphere (Badwater in Death Valley at 282 feet below sea level). Our state contains 20,000 square miles of desert, nearly 700 miles of Pacific coastline, an unaccountable wealth of snow-capped peaks and alpine lakes, a smattering of islands, and even a handful of volcanoes.

California also boasts its share of the world’s tallest living things, the towering coast redwoods. And we are the only state that is home to the world’s largest living trees (by volume), the giant sequoias. Also within California’s borders are groves of the planet’s oldest living things, the ancient bristlecone pines.

Quite simply, we live in a land of superlatives. California’s public lands are some of my favorite places on earth, and I believe that everyone should have the chance to see them and be humbled by their wonders. But this wish comes with a caveat: We must tread lightly and gently on our parks, with great respect and care for the land. And we must do whatever is required to ensure the protection of these beautiful places for future generations.

I wish you many inspiring days on the trail.

—Ann Marie Brown

Can’t decide where to hike this weekend? Here are our picks for the best hikes in California in 17 different categories, listed from north to south throughout the state:

Rim Loop Trail, Patrick’s Point State Park, Redwood Empire, tap here.

Lost Coast Trail/Mattole Trailhead, King Range National Conservation Area, Redwood Empire, tap here.

Lost Coast Trail/Sinkyone Trailhead, Sinkyone Wilderness State Park, Mendocino and Wine Country, tap here.

Coast Trail, Point Reyes National Seashore, San Francisco Bay Area, tap here.

Old Landing Cove Trail, Wilder Ranch State Park, Monterey and Big Sur, tap here.

Asilomar Coast Trail, Asilomar State Beach, Monterey and Big Sur, tap here.

Point Lobos Perimeter, Point Lobos State Reserve, Monterey and Big Sur, tap here.

Montaña de Oro Bluffs Trail, Montaña de Oro State Park, Santa Barbara and Vicinity, tap here.

Razor Point and Beach Trail Loop, Torrey Pines State Reserve, San Diego and Vicinity, tap here.

Cabrillo Tidepools, Cabrillo National Monument, San Diego and Vicinity, tap here.

Arcata Marsh Trail, Arcata Marsh and Wildlife Sanctuary, Redwood Empire, tap here.

Abbotts Lagoon Trail, Point Reyes National Seashore, San Francisco Bay Area, tap here.

Martin Griffin Preserve/Audubon Canyon Ranch Trail, Martin Griffin Preserve, San Francisco Bay Area, tap here.

Arrowhead Marsh, Martin Luther King Regional Shoreline, San Francisco Bay Area, tap here.

Elkhorn Slough South Marsh Loop, Moss Landing, Monterey and Big Sur, tap here.

Chester, Sousa, and Winton Marsh Trails, San Luis National Wildlife Refuge, San Joaquin Valley, tap here.

Carrizo Plain and Painted Rock, Carrizo Plains National Monument, San Joaquin Valley, tap here.

Mono Lake South Tufa Trail, Mono Lake Tufa State Reserve, Yosemite and Mammoth Lakes, tap here.

Silverwood Wildlife Sanctuary, San Diego and Vicinity, tap here.

Devils Punchbowl (via Doe Flat Trail/Buck Lake Trail), Siskiyou Wilderness, Shasta and Trinity, tap here.

Shasta Summit Trail, Shasta-Trinity National Forest, Shasta and Trinity, tap here.

Rooster Comb Loop (Long Version), Henry W. Coe State Park, San Francisco Bay Area, tap here.

Half Dome, Yosemite Valley, Yosemite and Mammoth Lakes, tap here.

Don Cecil Trail to Lookout Peak, Kings Canyon National Park, Sequoia and Kings Canyon, tap here.

Alta Peak, Sequoia National Park, Sequoia and Kings Canyon, tap here.

Mount Whitney Trail, John Muir Wilderness, Sequoia and Kings Canyon, tap here.

Mount Baldy, Angeles National Forest, Los Angeles and Vicinity, tap here.

Vivian Creek Trail to Mount San Gorgonio, San Gorgonio Wilderness, Los Angeles and Vicinity, tap here.

Ubehebe Peak, Death Valley National Park, California Deserts, tap here.

Mosaic Canyon, Death Valley National Park, California Deserts, tap here.

Wildrose Peak Trail, Death Valley National Park, California Deserts, tap here.

Ryan Mountain Trail, Joshua Tree National Park, California Deserts, tap here.

Mastodon Peak, Joshua Tree National Park, California Deserts, tap here.

Lost Palms Oasis, Joshua Tree National Park, California Deserts, tap here.

Tahquitz Canyon, Agua Caliente Indian Reservation, California Deserts, tap here.

Ladder Canyon and Big Painted Canyon, Mecca Hills Wilderness, California Deserts, tap here.

Borrego Palm Canyon, Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, California Deserts, tap here.

The Slot, Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, California Deserts, tap here.

Whiskeytown Falls, Whiskeytown Lake National Recreation Area, Shasta and Trinity, tap here.

American River Parkway, Sacramento and Gold Country, tap here.

Fallen Leaf Lake Trail, South Lake Tahoe, Tahoe and Northern Sierra, tap here.

Parker Lake Trail, Ansel Adams Wilderness, Yosemite and Mammoth Lakes, tap here.

Convict Canyon to Lake Dorothy, John Muir Wilderness, Yosemite and Mammoth Lakes, tap here.

McGee Creek to Steelhead Lake, John Muir Wilderness, Yosemite and Mammoth Lakes, tap here.

Blue Lake, John Muir Wilderness, Sequoia and Kings Canyon, tap here.

Tyee Lakes, John Muir Wilderness, Sequoia and Kings Canyon, tap here.

Farewell Gap Trail to Aspen Flat, Sequoia National Park, Sequoia and Kings Canyon, tap here.

Boucher Trail and Scott’s Cabin Loop, Palomar Mountain State Park, San Diego and Vicinity, tap here.

Mount Eddy Trail, Shasta-Trinity National Forest, Shasta and Trinity, tap here.

Lassen Peak Trail, Lassen Volcanic National Park, Lassen and Modoc, tap here.

Rubicon Trail, D. L. Bliss State Park, Tahoe and Northern Sierra, tap here.

Perimeter Trail, Angel Island State Park, San Francisco Bay Area, tap here.

Clouds Rest, Yosemite National Park, Yosemite and Mammoth Lakes, tap here.

Sentinel Dome, Yosemite National Park, Yosemite and Mammoth Lakes, tap here.

Panorama Trail, Yosemite National Park, Yosemite and Mammoth Lakes, tap here.

Moro Rock, Sequoia National Park, Sequoia and Kings Canyon, tap here.

The Needles Spires, Giant Sequoia National Monument, Sequoia and Kings Canyon, tap here.

Devils Slide Trail to Tahquitz Peak, San Jacinto Wilderness, Los Angeles and Vicinity, tap here.

Aerial Tramway to San Jacinto Peak, Mount San Jacinto State Park and Wilderness, California Deserts, tap here.

Rainbow and Lake of the Sky Trails, Tahoe National Forest, Tahoe and Northern Sierra, tap here.

Angora Lakes Trail, Tahoe National Forest, Tahoe and Northern Sierra, tap here.

Tomales Point Trail, Point Reyes National Seashore, San Francisco Bay Area, tap here.

Fitzgerald Marine Reserve, Moss Beach, San Francisco Bay Area, tap here.

Año Nuevo Trail, Año Nuevo State Preserve, San Francisco Bay Area, tap here.

Pinecrest Lake National Recreation Trail, Stanislaus National Forest, Yosemite and Mammoth Lakes, tap here.

Devils Postpile and Rainbow Falls, Devils Postpile National Monument, Yosemite and Mammoth Lakes, tap here.

Tokopah Falls, Sequoia National Park, Sequoia and Kings Canyon, tap here.

Cabrillo Tidepools, Cabrillo National Monument, San Diego and Vicinity, tap here.

Lost Horse Mine, Joshua Tree National Park, California Deserts, tap here.

Haypress Meadows Trailhead, Marble Mountain Wilderness, Shasta and Trinity, tap here.

South Gate Meadows, Mount Shasta Wilderness, Shasta and Trinity, tap here.

Carson Pass to Echo Lakes Resort (PCT), Tahoe and Northern Sierra, tap here.

Grass Valley Loop, Anthony Chabot Regional Park, San Francisco Bay Area, tap here.

Boy Scout Tree Trail, Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park, Redwood Empire, tap here.

Tall Trees Trail, Redwood National Park, Redwood Empire, tap here.

Redwood Creek Trail, Redwood National Park, Redwood Empire, tap here.

Bull Creek Trail North, Humboldt Redwoods State Park, Redwood Empire, tap here.

Redwood Creek Trail, Muir Woods National Monument, San Francisco Bay Area, tap here.

Shadow of the Giants, Sierra National Forest, Yosemite and Mammoth Lakes, tap here.

General Grant Tree Trail, Kings Canyon National Park, Sequoia and Kings Canyon, tap here.

Redwood Canyon, Kings Canyon National Park, Sequoia and Kings Canyon, tap here.

Congress Trail Loop, Sequoia National Park, Sequoia and Kings Canyon, tap here.

Trail of 100 Giants, Giant Sequoia National Monument, Sequoia and Kings Canyon, tap here.

McCloud Nature Trail, Shasta-Trinity National Forest, Shasta and Trinity, tap here.

Rainbow and Lake of the Sky Trails, Tahoe National Forest, Tahoe and Northern Sierra, tap here.

Trail of the Gargoyles, Stanislaus National Forest, Tahoe and Northern Sierra, tap here.

Shadow of the Giants, Sierra National Forest, Yosemite and Mammoth Lakes, tap here.

Methuselah Trail, Inyo National Forest, Yosemite and Mammoth Lakes, tap here.

Unal Trail, Sequoia National Forest, Sequoia and Kings Canyon, tap here.

Piño Alto Trail, Los Padres National Forest, Santa Barbara and Vicinity, tap here.

McGrath State Beach Nature Trail, McGrath State Beach, Santa Barbara and Vicinity, tap here.

Ponderosa Vista Nature Trail, San Bernardino National Forest, Los Angeles and Vicinity, tap here.

Inaja Memorial Trail, Cleveland National Forest, San Diego and Vicinity, tap here.

Taylor Lake Trailhead to Hogan Lake, Russian Wilderness, Shasta and Trinity, tap here.

Toad Lake Trail, Shasta-Trinity National Forest, Shasta and Trinity, tap here.

Echo and Twin Lakes, Lassen Volcanic National Park, Lassen and Modoc, tap here.

Woods Lake to Winnemucca Lake, Mokelumne Wilderness, Tahoe and Northern Sierra, tap here.

Coast Trail, Point Reyes National Seashore, San Francisco Bay Area, tap here.

Black Mountain, Monte Bello Open Space Preserve, San Francisco Bay Area, tap here.

May Lake and Mount Hoffman, Yosemite National Park, Yosemite and Mammoth Lakes, tap here.

Glen Aulin and Tuolumne Falls, Yosemite National Park, Yosemite and Mammoth Lakes, tap here.

Ladybug Trail, Sequoia National Park, Sequoia and Kings Canyon, tap here.

Gabrielino National Recreation Trail to Bear Canyon, Angeles National Forest, Los Angeles and Vicinity, tap here.

Preston Peak, Siskiyou Wilderness, Shasta and Trinity, tap here.

Grizzly Lake, Trinity Alps Wilderness, Shasta and Trinity, tap here.

Shasta Summit Trail, Shasta-Trinity National Forest, Shasta and Trinity, tap here.

Lassen Peak Trail, Lassen Volcanic National Park, Lassen and Modoc, tap here.

East Peak Mount Tamalpais, Mount Tamalpais State Park, San Francisco Bay Area, tap here.

Mount Dana, Yosemite National Park, Yosemite and Mammoth Lakes, tap here.

White Mountain Peak Trail, Inyo National Forest, Yosemite and Mammoth Lakes, tap here.

Mount Whitney Trail, John Muir Wilderness, Sequoia and Kings Canyon, tap here.

Mount Williamson, Angeles National Forest, Los Angeles and Vicinity, tap here.

Vivian Creek Trail to Mount San Gorgonio, San Gorgonio Wilderness, Los Angeles and Vicinity, tap here.

McClendon Ford Trail, Smith River National Recreation Area, Redwood Empire, tap here.

Deer Creek Trail, Lassen National Forest, Lassen and Modoc, tap here.

Paradise Creek Trail, Sequoia National Park, Sequoia and Kings Canyon, tap here.

Alder Creek Trail, Giant Sequoia National Monument, Sequoia and Kings Canyon, tap here.

Burney Falls Loop Trail, McArthur-Burney Falls Memorial State Park, Lassen and Modoc, tap here.

Feather Falls Loop, Plumas National Forest, Sacramento and Gold Country, tap here.

Grouse Falls, Tahoe National Forest, Tahoe and Northern Sierra, tap here.

McWay Falls Overlook, Julia Pfeiffer Burns State Park, Monterey and Big Sur, tap here.

Waterwheel Falls, Yosemite National Park, Yosemite and Mammoth Lakes, tap here.

Devils Postpile and Rainbow Falls, Devils Postpile National Monument, Yosemite and Mammoth Lakes, tap here.

Upper Yosemite Fall, Yosemite Valley, Yosemite and Mammoth Lakes, tap here.

Mist Trail and John Muir Loop to Nevada Fall, Yosemite Valley, Yosemite and Mammoth Lakes, tap here.

Bridalveil Fall, Yosemite Valley, Yosemite and Mammoth Lakes, tap here.

Tokopah Falls, Sequoia National Park, Sequoia and Kings Canyon, tap here.

Taylor Lake Trail, Russian Wilderness, Shasta and Trinity, tap here.

Kangaroo Lake Trailhead/Cory Peak, Klamath National Forest, Shasta and Trinity, tap here.

Lake Cleone Trail, MacKerricher State Park, Mendocino and Wine Country, tap here.

South Yuba Independence Trail, Nevada City, Sacramento and Gold Country, tap here.

Sierra Discovery Trail, PG&E Bear Valley Recreation Area, Tahoe and Northern Sierra, tap here.

Abbotts Lagoon Trail, Point Reyes National Seashore, San Francisco Bay Area, tap here.

McWay Falls Overlook, Julia Pfeiffer Burns State Park, Monterey and Big Sur, tap here.

Lower Yosemite Fall, Yosemite Valley, Yosemite and Mammoth Lakes, tap here.

Roaring River Falls, Kings Canyon National Park, Sequoia and Kings Canyon, tap here.

Salt Creek Interpretive Trail, Death Valley National Park, California Deserts, tap here.

Lake Margaret, Eldorado National Forest, Tahoe and Northern Sierra, tap here.

Chimney Rock Trail, Point Reyes National Seashore, San Francisco Bay Area, tap here.

Grass Valley Loop, Anthony Chabot Regional Park, San Francisco Bay Area, tap here.

Rocky Ridge and Soberanes Canyon Loop, Garrapata State Park, Monterey and Big Sur, tap here.

Path of the Padres, San Luis Reservoir State Recreation Area, San Joaquin Valley, tap here.

Lundy Canyon Trail, Hoover Wilderness, Yosemite and Mammoth Lakes, tap here.

Hite Cove Trail, Sierra National Forest, Yosemite and Mammoth Lakes, tap here.

Whitney Portal to Lake Thomas Edison (JMT/PCT), Sequoia and Kings Canyon, tap here.

Montaña de Oro Bluffs Trail, Montaña de Oro State Park, Santa Barbara and Vicinity, tap here.

Antelope Valley Poppy Reserve Loop, California Deserts, tap here.

Coastal Trail Loop (Fern Canyon/Ossagon Section), Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park, Redwood Empire, tap here.

Spirit Lake Trail, Marble Mountain Wilderness, Shasta and Trinity, tap here.

Captain Jack’s Stronghold, Lava Beds National Monument, Lassen and Modoc, tap here.

Tomales Point Trail, Point Reyes National Seashore, San Francisco Bay Area, tap here.

Pescadero Marsh, San Francisco Bay Area, tap here.

Año Nuevo Trail, Año Nuevo State Preserve, San Francisco Bay Area, tap here.

Carrizo Plain and Painted Rock, Carrizo Plains National Monument, San Joaquin Valley, tap here.

Tule Elk State Natural Reserve, San Joaquin Valley, tap here.

Caliche Forest and Point Bennett, Channel Islands National Park, tap here.

Desert Tortoise Discovery Loop, Desert Tortoise Natural Area, California Deserts, tap here.

Aside from the shoes on your feet, it doesn’t take much equipment to go day hiking. Whereas backpackers must concern themselves with tents, sleeping pads, pots and pans, and the like, day hikers don’t have as much planning and packing to do. Still, too many day hikers set out carrying too little and get into trouble as a result. Here’s our list of essentials:

Water is even more important than food, although it’s always unwise to get caught without a picnic, or at least some edible supplies for emergencies. If you don’t want to carry the weight of a couple water bottles, at least carry a purifier or filtering device so you can get water from streams, rivers, or lakes. It should go without saying, but never, ever drink water from a natural source without purifying it. The microscopic organisms Giardia lamblia and Cryptosporidium are found in backcountry water sources and can cause a litany of terrible gastrointestinal problems. Only purifying or boiling water from natural sources will eliminate giardiasis.

There are plenty of tools available to make backcountry water safe to drink. One of the most popular for day hikers and backpackers is a purifier called SteriPEN, which uses ultraviolet light rays instead of chemicals to purify water. It’s small, light, runs on batteries, and purifies 32 ounces of water in about 90 seconds.

Water bottle-style filters, such as those made by Bota, Aquamira, Katadyn, or LifeStraw, are as light as an empty plastic bottle and eliminate the need to carry both a filter and a bottle. You simply dip the bottle in the stream, screw on the top (which has a filter inside it), and squeeze the bottle to drink. The water is filtered on its way out of the squeeze top.

There’s even a straw that purifies water so you can drink right out of creeks and lakes, as long as you don’t mind having to lie on your belly next to the water to do it. It costs about 20 bucks, fits in your pocket, and weighs almost nothing. If you carry the LifeStraw Personal Water Filter and an empty water bottle, you don’t even have to lay on the ground. Just fill your empty bottle with water, then insert the LifeStraw and drink.

Of course, in desert regions and arid parts of the state, you won’t find a natural water source to filter from, so carrying water may still be necessary. Remember that trails that cross running streams in the winter and spring months may cross dry streams in the summer and autumn months.

What you carry for food is up to you. Some people go gourmet and carry the complete inventory of a fancy grocery store. If you don’t want to bother with much weight, stick with high-energy snacks like nutrition bars, nuts, dried fruit, turkey or beef jerky, and crackers. We like to carry a mix of salty and sweet foods, so we are always ready to accommodate any possible trail craving. Our rule is always to bring more than you think you can eat. You can always carry it out with you, or give it to somebody else on the trail who needs it.

If you’re hiking in a group, each of you should carry your own supply of food and water just in case someone gets too far ahead or behind.

A map of the park or public land you’re visiting is essential. Never count on trail signs to get you where you want to go. Signs get knocked down or disappear with alarming frequency due to rain, wind, wildfire, or park visitors looking for souvenirs. Many hikers think that carrying a GPS device eliminates the need for a map, but this isn’t always true. If you get lost, a map can show you where you are (via landmarks such as peaks, lakes, ridges, etc.) and can show you where the nearest trail or junction is located. It can also show alternate routes if you decide not to go the way you originally planned.

Always obtain a map from the managing agency of the place you’re visiting. Their names and phone numbers are listed in the Resource guide in the back of this book. Most California parks and preserves have online maps that you can download for free.

On the trail, conditions can change at any time. Not only can the weather suddenly turn windy, foggy, or rainy, but your body’s conditions also change: You’ll perspire as you hike up a sunny hill and then get chilled at the top of a windy ridge or when you head downhill into shade. Because of this, cotton fabrics don’t function well in the outdoors. Once cotton gets wet, it stays wet. Generally, polyester-blend fabrics dry faster. Some high-tech fabrics will actually wick moisture away from your skin. Invest in a few items of clothing made from these fabrics and you’ll be more comfortable on the trail.

Always carry a lightweight jacket, preferably one that is waterproof and also wind-resistant. If your jacket isn’t waterproof, pack along one of the $3, single-use rain ponchos that come in a package the size of a deck of cards. They’re available at outdoors stores, hardware stores, and drugstores. If you can’t part with three bucks, carry an extra-large garbage bag, which can be converted into a waterproof vest. In cooler temperatures, or when heading to a mountain summit (even on a hot day), carry gloves and a hat as well.

Just in case your hike takes a little longer than you planned, bring at least one flashlight and preferably two or three. Your cell phone light may work great, but if your battery runs out of juice, you’re out of luck. Don’t count on your cell phone as your only source of light. Mini flashlights are available everywhere, weigh almost nothing, and can save the day—or night. We especially like the tiny squeeze flashlights, about the size and shape of a quarter, which you can clip on to any key ring. Make sure you buy the kind with a long-lasting LED bulb and an on/off switch. Headlamps also make a great light source and will leave your hands free for other tasks. Whatever type of light sources you carry, make sure they work before you set out on the trail. Always take along an extra set of batteries and an extra bulb, or simply an extra light source or two.

You know the dangers of the sun. Wear sunglasses to protect your eyes and sunscreen with a high SPF rating on any exposed skin. Put on your sunscreen 30 minutes before you go outdoors so it has time to take effect. Reapply your sunscreen every two hours. In addition, protect the skin on your face with a good wide-brimmed hat, and don’t forget about your lips, which burn easily. Wear lip balm that has a high SPF rating.

Several kinds of insect repellent now come with sunscreen, so you can put on one lotion instead of two. Many types of insect repellent have an ingredient called DEET, which is extremely effective but also quite toxic. Children should not use repellent with high levels of DEET, although it seems to be safe for adults. Don’t leave it sitting on your dashboard, though; if it spills, it can damage plastic, rubber, and vinyl. Other types of repellent are made of natural substances, such as lemon eucalyptus oil. What works best? Every hiker has his or her opinion. If you visit the High Sierra in the middle of a major mosquito hatch, it often seems like nothing works except covering your entire body in mosquito netting. For typical summer days outside of a hatch period, find a repellent you like and carry it with you. We’re fond of a brand called Natrapel, which is DEET-free and available in various-sized spray bottles. It contains a 20 percent picaridin formula, which is recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and World Health Organization for insect bite protection.

Nothing major is required here unless you’re fully trained in first aid, but a few supplies for treating blisters, an antibiotic ointment, and an anti-inflammatory medicine (such as ibuprofen) can serve as valuable tools in minor and major emergencies. (For details on taking care of and preventing blisters, see Shoes and Socks.) If anyone in your party is allergic to bee stings or anything else in the outdoors, carry their medication.

Be sure to carry one with several blades, a can opener, scissors, and tweezers. The latter is useful for removing slivers or ticks.

A compass can be a real lifesaver. Just be sure that you know how to use it.

Hikers are divided over the necessity of using hiking or trekking poles. They either swear by them or swear they will never carry them. We’ve had enough injuries over the years to know that a pair of ultra-lightweight hiking poles can come in handy, especially if you’re trying to accomplish a long hike on rough, rocky trails. First, research shows that hiking poles definitely improve your speed and efficiency when walking, so if you’re traveling a long distance, they’ll get you where you want to go faster and with less fatigue. Secondly, poles are incredibly useful when you need to ford a creek or river (plant your poles in the streambed and they provide stability, so you have less chance of going for a swim) or when you’re hiking steeply downhill on loose shale (plant your poles ahead of you and you won’t topple forward). In terms of biomechanics, hiking poles transform you from a somewhat awkward two-legged human to an ultra-efficient four-legged mountain goat. Today’s hiking poles are extremely lightweight and fold up into small sections, so if you don’t want to use them for your entire hike, you can always strap them to your pack’s exterior or stick them inside.

Ask yourself this question: “What would I need to have if I had to spend the night out here?” Aside from food, water, and other items previously listed, here are some basic emergency supplies that will get you through an unplanned night in the wilderness.

Lightweight tarp or sleeping bag. Get one made of foil-like mylar film, designed to reflect radiating body heat. These make a great emergency shelter and weigh almost nothing. The non-reflective side can even be used to signal a helicopter, should the need ever arise.

Fire-starting kit. A couple of packs of matches, a lighter, a candle, and some cotton balls soaked in Vaseline. Keep these in a waterproof container or sealable plastic bag, just in case you ever need to build a fire in a serious emergency.

Whistle. If you ever need help, you can blow a whistle for a lot longer than you can shout. Voices don’t carry well in wind or near a running stream. A plastic whistle is a cheap investment that can save your life.

Small signal mirror. It could be just what you need to get found if you ever get lost. Or if you want to go the high-tech route, consider investing in a personal locator beacon (PLB). These are invaluable for people who hike enjoy hiking alone. If you wind up injured and your cell phone doesn’t work, a PLB will let you signal for help.

Every hiker eventually conducts a search for the perfect boot. This means looking for something that will provide ideal foot and ankle support and won’t cause blisters. Although there are dozens of possibilities—in fact so many that it can be confusing—you can find the perfect boot.

For advice on selecting boots, two of the nation’s preeminent long-distance hikers, Brian Robinson of Mountain View (7,200 miles in 2001) and Ray Jardine of Oregon (2,700 miles of Pacific Crest Trail in three months), weighed in on the discussion. Both believe that the weight of a boot is the defining factor when selecting hiking footwear. They both go as light as possible, believing that heavy boots will eventually tire you out. Arch support is also vital, especially to people who hike less frequently and thus have not developed great foot strength.

To stay blister-free, the most important factors are clean feet, good socks, and the flexibility of a boot. If there is any foot slippage from a too-thin or compressed sock, accumulated dirt, or a stiff boot, you can rub up a blister in minutes. Wearing two pairs of socks can sometimes do the trick—try two fresh sets of SmartWool socks ($15 a pop), or try one pair over the top of a lightweight wicking liner sock. If you still get a blister or two, know how to treat them fast so they don’t turn your walk into a sore-footed endurance test.

In addition to finding boots with the proper flexibility, comfort, and arch support, you’ll need to consider the types of terrain you’ll be covering and the number of miles (or number of days) you’ll be hiking. Investing in the correct shoes will take some time and research, but your feet will thank you for it.

There are three basic kinds of hiking footwear, ranging from lightweight to midweight to heavyweight. Select the right one for you or pay the consequences. One great trick when on a hiking vacation is to bring a couple different pairs, and then for each hike, wear different footwear. By changing boots, you change the points of stress on your feet and legs, greatly reducing soreness and the chance of creating a hot spot on a foot. This also allows you to go lightweight on flat trails with a hard surface, and heavyweight on steep trails with loose footing, where additional boot weight can help traction in downhill stretches.

In the first category, lightweight hiking boots or trail-running shoes are designed for day-hiking and short and easy backpacking trips. For those with strong feet and arches, they are popular even on multiday trips. Some of the newer models are like rugged athletic shoes, designed with a Gore-Tex top for lightness and a Vibram sole for traction. These are perfect for people who like to hike fast and cover a lot of ground. Because these boots are flexible, they’re easy to break in, and with fresh socks they rarely cause blister problems. Because they are lightweight and usually made of a breathable fabric, hiking fatigue is greatly reduced. For day-hiking, they are the footwear of choice for most. Many long-distance hikers also choose these.

On the negative side, because these boots are so light, traction is not always good on steep, slippery surfaces. In addition, lightweight boots provide less than ideal ankle and arch support, which can be a problem on rocky or steep trails. Turn your ankle and your trip can be ruined. Lightweight hiking boots often are not very durable, either. If you hike a lot, you may wear a pair out in one summer.

These boots are designed for both on- and off-trail hiking, and are constructed to meet the demands of carrying a light to moderately heavy pack. They usually feature high ankle support, a deep Vibram lug sole, built-in orthotics, arch support, and often a waterproof exterior. They can stand up to hundreds of miles of wilderness use, even if they are banged against rocks and walked through streams.

On the negative side, midweight or backpacking boots can be quite hot. If the boots get wet, they can take days to dry. They weigh a fair amount and can tire you out, especially if you are not accustomed to having weight on your feet. This may reduce the number of miles you are capable of hiking in a day.

Like midweight boots, these shoes are designed for both on- and off-trail hiking, but they can stand up to the rigors of carrying a much heavier load. They are designed to be worn on multiday backpacking trips (four days or more with substantial miles hiked each day). Mountaineering boots are identified by midrange tops, laces that extend almost as far as the toes, and ankle areas that are as stiff as a board. The lack of “give” is what endears them to some mountaineers. Their stiffness is preferred when rock climbing, walking off-trail on craggy surfaces, or hiking down the edge of streambeds. Because these boots don’t yield on rugged terrain, they can reduce ankle and foot injuries and provide better traction. Some are made so that they can accept crampons for travel on snow and ice.

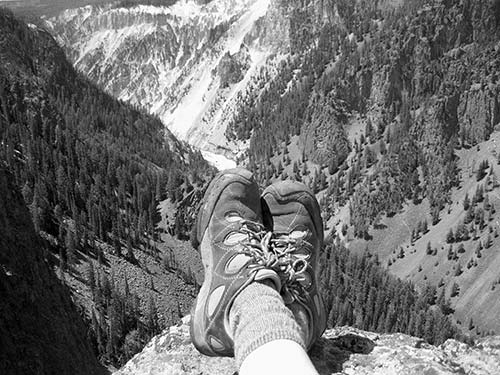

Lightweight hiking shoes are perfect for short treks and day-long trips.

The drawback to stiff boots is that if you don’t have the proper socks and your foot starts slipping around in the boot, you will get a set of blisters that require so much tape and moleskin you will end up looking like a mummy. Also, heavyweight boots must be broken in for weeks or even months before taking them out on the trail.

Hiking shoes come in a wide range of styles, brands, and prices. If you wander about comparing all their many features, you will get as confused as a kid in a toy store. Instead, go into the store with your mind clear about what you want. For the best quality, expect to spend $80-120 for lightweight hiking boots, $100-200 for midweight boots, and $150-250 for mountaineering boots. If you go much cheaper, the quality of the boot—and the health of your feet—will likely suffer. This is one area where you don’t want to scrimp.

If you plan on using the advice of a shoe salesperson, first look at what kind of boots he or she is wearing. If the salesperson isn’t even wearing boots, then take whatever he or she says with a grain of salt. Most people who own quality boots, including salespeople, will wear them almost daily if their job allows, since boots are the best footwear available.

Enter the store with a precise use and style in mind. Rather than fish for suggestions, tell the salesperson exactly what type of hiking you plan to do. Try two or three brands of the same category of shoe (lightweight, midweight, or heavyweight/mountaineering). Try on both boots in a pair simultaneously so you know exactly how they’ll feel. Always try them on over a good pair of hiking socks (see Socks), not regular everyday socks. If possible, walk up and down a set of stairs, or up and down an incline, while wearing the boots. Your feet should not slide forward easily, and your heel should not move from side to side. Also, your heel should not lift more than one-quarter inch when you walk around. Are the boots too stiff? Are your feet snug yet comfortable, or do they slip? Do they feel supportive on the inside of your foot? Is there enough room in the toe box so that your toes can spread or wiggle slightly? If your toes touch the front of your boot, count on blisters.

People can spend so much energy selecting the right kind of boot that they virtually overlook wearing the right kind of socks. One goes with the other.

Your socks should be thick enough to cushion your feet and should fit snugly. Without good socks you might fasten the bootlaces too tight, and that’s like putting a tourniquet on your feet. On long trips of a week or more, you should have plenty of clean socks on hand, or plan on washing what you have during your trip. As socks become worn, they also become compressed, dirty, and damp. If they fold over, you’ll get a blister.

Do not wear cotton socks. Your foot can get damp and mix with dirt, which can cause a hot spot to start on your foot. Instead, start with a sock made of a synthetic composite, such as those made by SmartWool. These will partially wick moisture away from the skin.

If you choose to wear two pairs, or a pair of socks over a sock liner, the exterior sock should be wool or its synthetic equivalent. This will cushion your feet, create a snug fit in your boot, and provide some additional warmth and insulation in cold weather. It is critical to keep socks clean. If you wear multiple socks, you may need to go up a boot size to accommodate the extra layers around your feet.

In almost all cases, blisters are caused by the simple rubbing of skin against the rugged interior of a boot. It can be worsened by several factors:

The key to treating blisters is to work fast at the first sign of a hot spot. If you feel a hot spot, never keep walking, figuring the problem will go away. Stop immediately and remedy the situation. Before you remove your socks, check to see if the sock is wrinkled—a likely cause of the problem. If so, either change socks or pull them tight, removing the tiny folds, after taking care of the blister.

To take care of the blister, cut a piece of moleskin to cover the offending spot, securing the moleskin with white medical tape. Even better than moleskin is a product called Spenco Second Skin, which helps to heal the blister as well as protect it, and will stick to your skin without tape.

Ticks, poison oak, and stinging nettles can be far worse than a whole convention of snakes, mountain lions, and bears. But you can avoid them with a little common sense, and here’s how:

The easiest way to stay clear of ticks is to wear long pants and long sleeves when you hike, and tuck your pant legs into your socks. But this system isn’t fail-proof. The darn things sometimes find their way on to your skin no matter what you do. Always check yourself thoroughly when you leave the trail, looking carefully for anything that’s crawling on you. Check your clothes, and also your skin underneath. A good friend can be a useful assistant in this endeavor.

Remember that if you find a tick on your skin, the larger brown ones are harmless. Of the nearly 50 varieties of ticks present in California, only the tiny brown-black ones, called the western black-legged tick, can carry Lyme disease.

Most tick bites cause a sharp sting that will get your attention. But rarely, ticks will bite you without you noticing. If you’ve been in the outdoors, and then a few days or a week later start to experience flu-like symptoms like headaches, fever, muscle soreness, neck stiffness, or nausea, see a doctor immediately. Tell the doctor you are concerned about possible exposure to ticks and Lyme disease. Another early tell-tale symptom is a slowly expanding red rash near the tick bite, which appears a week to a month after the bite. Caught in its early stages, Lyme disease is easily treated with antibiotics, but left untreated, it can be severely debilitating.

The best way to remove a tick is by grasping it as close to your skin as possible, then pulling it gently and slowly straight out, without twisting or jerking it. Tweezers work well for the job, and many Swiss Army knives include tweezers.

That old Boy Scout motto holds true: Leaves of three, let them be. Learn to recognize and avoid Toxicodendron diversilobum, which produces an itching rash that can last for weeks. The shiny-leaved shrub grows with maddening exuberance in California coastal and mountain canyons below 5,000 feet. If you can’t readily identify poison oak, stay away from vinelike plants that have three leaves. Remember that in spring and summer, poison oak looks a little like wild blackberry bushes and often has red colors in its leaves, as well as green. In late fall and winter, poison oak goes dormant and loses its leaves, but it’s still potent.

Avoid poison oak by staying on the trail and wearing long pants and long sleeves in areas that are encroached by it. If you prefer to wear shorts when you hike, try a pair of the convertible pants that are found at most outdoor stores. These are lightweight pants with legs that zip off to convert to shorts. Put the pant legs on when you come to an area that is rife with poison oak. If you accidentally touch the plant with your bare skin, wash off the area as soon as possible. Waiting until you get home five hours later may be too late, so wash as best as you can, using stream water or whatever is available. Hikers who are highly allergic to poison oak should consider carrying packages of Tecnu, a poison oak wash-off treatment that is sold in bottles or individual foil packs. Carrying one little package could save you weeks of scratching.

poison oak

Remember that if poison oak touches your clothes, your pack, or even your dog, and then you handle any of those items, the oils can rub off onto your skin. Wash everything thoroughly as soon as you get home.

If you do develop poison oak rash, a few relatively new products on the market can help you get rid of it. One product is called Zanfel, and although it costs a small fortune ($20-40 a bottle), it is available at pharmacies without a prescription. You simply pour it on the rash and the rash vanishes, or at least greatly diminishes. Some hikers also swear by a product called Mean Green Power Hand Scrub, which costs about half what Zanfel does. No matter what you use, if you get a severe enough case of poison oak, the only recourse is a trip to the doctor for prednisone pills.

Ouch! This member of the nettle family is bright green, can grow to six feet tall, and is covered with tiny stinging hairs. When you brush against one, it zaps you with its poison, which feels like a mild bee sting. The sting can last for up to 24 hours. Stinging nettles grow near creeks or streams, and they’re usually found in tandem with deer ferns and sword ferns. If the nettles zing you, grab a nearby fern leaf and rub the underside of it against the stinging area. It sounds odd, but it sometimes helps to take the sting out. If it doesn’t help, you’re out of luck, and you just have to wait for the sting to go away.

Snakes, mountain lions, and bears—these creatures deserve your respect, and you should understand a little bit about them.

Eight rattlesnake species are found in California. These members of the pit viper family have wide triangular heads, narrow necks, and rattles on their tales. Rattlesnakes live where it’s warm, usually at elevations below 6,000 feet. Most snakes will slither off at the sound of your footsteps; if you encounter one, freeze or move back slowly so that it can get away without feeling threatened. They will almost always shake their tails and produce a rattling or buzzing noise to warn you off. The sound is unmistakable, even if you’ve never heard it before.

If you’re hiking on a nice day, when rattlesnakes are often out sunning themselves on trails and rocks, keep your eyes open for them so you don’t step on one or place your hand on one. Be especially on the lookout for rattlesnakes in the spring, when they leave their winter burrows and come out in the sun. Morning is the most common time to see them, as the midday sun is usually too hot for them.

Although rattlesnake bites are painful, they are very rarely fatal. More than 100 people in California are bitten by rattlesnakes each year, resulting in only one or two fatalities on average. About 25 percent of rattlesnake bites are dry, with no venom injected. Symptoms of bites that do contain venom usually include tingling around the mouth, nausea and vomiting, dizziness, weakness, sweating, and/or chills. If you should get bitten by a rattlesnake, your car key—and the nearest telephone—are your best first aid. Call 911 as soon as you can, or have someone drive you to the nearest hospital. Don’t panic or run, which can speed the circulation of venom through your system.

Except for a handful of rattlesnake species, all other California snakes are not poisonous. Just give them room to slither by.

The mountain lion (also called cougar or puma) lives in almost every region of California but is rarely seen. Most habitats that are wild enough to support deer will support mountain lions, which typically eat about one deer per week. When the magnificent cats do show themselves, they receive a lot of media attention. The few mountain lion attacks on California hikers have been widely publicized. Still, the vast majority of hikers never see a mountain lion, and those who do usually report that the cat vanished into the brush at the first sign of nearby humans.

If you’re hiking in an area where mountain lions or their tracks have been spotted, remember to keep children close to you on the trail, and your dog leashed. If you see a mountain lion and it doesn’t run away immediately, make yourself appear as large as possible (raise your arms, open your jacket, wave a big stick) and speak loudly and firmly or shout. If you have children with you, pick them up off the ground, but try to do it without crouching down or leaning over. (Crouching makes you appear smaller and less aggressive, more like prey.) Don’t turn your back on the cat or run from it, but rather back away slowly and deliberately, always retaining your aggressive pose and continuing to speak loudly. Mountain lions are far more likely to attack a fleeing mammal than one that stands its ground. Even after attacking, lions have been successfully fought off by adult hikers and even children who used rocks and sticks to defend themselves.

The only bears found in California are black bears (even though they are usually brown in color). A century ago, our state bear, the grizzly, roamed here as well, but the last one was shot and killed in the 1930s. Black bears almost never harm human beings—although you should never approach or feed a bear, or get between a bear and its cubs or its food. Black bears weigh between 250 and 400 pounds, can run up to 30 miles per hour, and are powerful swimmers and climbers. When they bound, the muscles on their shoulders roll like ocean breakers. If provoked, a bear could cause serious injury.

There’s only one important fact to remember about bears: They love snacks. The average black bear has to eat as much as 30,000 calories a day, and since their natural diet is made up of berries, fruits, plants, fish, insects, and the like, the high-calorie food of human beings is very appealing to them. Unfortunately, too many California campers have trained our state’s bears to crave the taste of corn chips, hot dogs, and soda pop.

Any time you see a bear, it’s almost a given that it is looking for food, preferably something sweet. Bears have become specialists in the food-raiding business. As a result, you must be absolutely certain that you keep your food away from them. Backpackers should always use bear-proof canisters to store their food for overnight trips. Hanging food from a tree is largely ineffective when done improperly, and the practice is now banned in most of the Sierra Nevada, where bear-proof food canisters are required by law. You can rent or buy a bear canister from most outdoor stores, or from many ranger stations in national parks and national forests. In national parks like Yosemite, Sequoia, and Kings Canyon, you can rent a bear canister for $5, then return it at the end of your trip.

At car campgrounds in bear territory, metal bear-proof food storage lockers must be used. Never leave your food unattended or in your vehicle. Rangers will ticket you for these violations. In addition, get an update from the rangers in your park about suitable bear precautions.

Bears are sometimes encountered on trails, although not as frequently as in campgrounds. If you’re hiking, bears will most likely hear you coming and avoid you. If one approaches you, either on the trail or in camp, yell loudly, throw small rocks or pine cones in the vicinity, and try to frighten the bear away. A bear that is afraid of humans is a bear that will stay wild and stay alive.

If you are backpacking in an area where bear canisters are not required, or where bears aren’t as bold as they are in the Sierra Nevada, you can substitute a food hang for a bear canister. This is where you place your food in a plastic or canvas garbage bag (always double-bag your food), then suspend it from a rope in midair, 10 feet from the trunk of a tree and 20 feet off the ground. Counterbalancing two bags with a rope thrown over a tree limb is very effective, but finding an appropriate limb can be difficult.

This is most easily accomplished by tying a rock to a rope, then throwing it over a high but sturdy tree limb. Next, tie your food bag to the rope and hoist it in the air. When you are satisfied with the position of the food bag, tie off the end of the rope to another tree.

Once a bear gets her mitts on your food, she considers it hers. There is nothing you can do. If this happens to you once, you will learn never to let food sit unattended.

A leading cause of death in the outdoors is hypothermia, which occurs when your body’s core temperature drops low enough that your vital organs can no longer function. Most cases of hypothermia occur at temperatures in the 50s, not below freezing, as you might expect. Often the victim has gotten wet, and/or is fatigued from physical exertion.

Initial symptoms of hypothermia include uncontrollable shivering, often followed by a complete stop in shivering, extreme lethargy, and an inability to reason. A hypothermic person will often want to lie down and rest or sleep. His or her hiking partners must jump into action to get the victim warm and dry immediately. Remove all wet clothes and put on dry ones. Cover his or her head with a warm hat. If someone in the group has an emergency space blanket (see Hiking Gear Checklist), wrap it around the victim. Get the hypothermic person to eat some quick-energy food, even candy, and drink warm beverages—this helps the body produce heat. Do not give the person alcohol, as this encourages heat loss.

Usually the result of overexposure to the sun and dehydration, symptoms of heat stroke include headache, mental confusion, and cramps throughout the body. Immediate action must be taken to reduce the body’s core temperature. Pour water on the victim’s head. Have him or her sit in a cool stream if possible. Make the person drink as much liquid as possible. Heat stroke is easily avoided by staying adequately hydrated and wearing a large-brimmed hat for protection from the sun.

Many hikers experience a shortness of breath when hiking only a few thousand feet higher than the elevation where they live. If you live on the California coast, you may notice slightly labored breathing while hiking at an elevation as low as 5,000 feet. As you go higher, it gets worse, sometimes leading to headaches and nausea. It takes a full 72 hours to acclimate to major elevation changes, although most people acclimatize after only 24 to 48 hours. The best preparation for hiking at a high elevation is to sleep at that elevation, or as close to it as possible, the night before. If you are planning a strenuous hike at 7,000 feet or above, spend a day or two before doing easier hikes at the same elevation. Also, get plenty of rest and drink plenty of fluids (but avoid all alcohol). Lack of sleep and dehydration can contribute to your susceptibility to “feeling the altitude.”

Serious altitude sickness typically occurs above 10,000 feet. It is generally preventable by simply allowing enough time for acclimation. But how do you acclimate for a climb to the top of Mount Whitney or Shasta, at more than 14,000 feet? The answer is you can’t, at least not completely. Spending a few days beforehand hiking at 10,000 feet and above will help tremendously. Staying fueled with food and fully hydrated will also help. But if you’ve never hiked above a certain elevation—say 13,000 feet—you don’t know how you are going to feel until you get there. If you start to feel ill (nausea, vomiting, severe headache), you are experiencing altitude sickness. Some people can get by with taking aspirin and trudging onward, but if you are seriously ill, the only cure is to descend as soon as possible. If the altitude has gotten to you badly enough, you may need someone to help you walk. Fatigue and elevation sickness can cloud your judgment in the same manner that hypothermia does, so take action before your symptoms become too severe.

Rock cairns act as directional aids on the trail.

For some hikers, it is quite easy to become lost. If you don’t get your bearings, getting found is the difficult part. If you’re hiking with a family or group, make sure everybody stays together. If anyone decides to split off from the group for any reason, make sure they have a trail map with them and that they know how to read it. Also, ensure that everyone in your group knows the rules regarding what to do if they get lost:

In areas above tree line or where the trail becomes faint, some hikers will mark the route with piles of small rocks to act as directional signs for the return trip. But if an unexpected snow buries these piles of rocks, or if you get well off the track, all you are left with is a moonscape. That is why every hiker should understand the concept of orienteering. In the process, you become a mountaineer.

When lost, the first step is to secure your present situation—that is, to make sure it does not get any worse. Take stock of your food, foul-weather gear, camp fuel, clothes, and your readiness to spend the night. Keep in mind that this is an adventure, not a crisis.

Then take out your topographic map, compass, and altimeter. What? Right: Never go into the unknown without them. Place the map on the ground, then set the compass atop the map and orient it north. In most cases, you will easily be able to spot landmarks, such as prominent mountaintops. In cases with a low overcast, where mountains are obscured in clouds, you can take this adventure one step further by checking your altimeter. By scanning the elevation lines on the map, you will be able to trace your near-exact position.

Always be prepared to rely on yourself, but also file a trip plan with the local ranger station, especially if hiking in remote wilderness areas. Carry plenty of food, fuel, and a camp stove. Make sure your clothes, weather gear, sleeping bag, and tent will keep you dry and warm. Always carry a compass, altimeter, and map with elevation lines, and know how to use them, practicing in good weather to get the feel of it.

With enough experience, you will discover that you can “read” the land so well that you will hardly even need to reference a map to find your way.

If you see or hear a thunderstorm approaching, avoid exposed ridges and peaks. This is disheartening advice when you’re only a mile from the summit of Half Dome, but follow it anyway. If you’re already on a mountain top, stay out of enclosed places, such as rock caves or recesses. Confined areas are deadly in lightning storms; hikers seeking refuge from lightning have been killed inside the stone hut on top of Mount Whitney. Do not lean against rock slopes or trees; try to keep a few feet of air space around you. Squat low on your boot soles, or sit on your day pack, jacket, or anything that will insulate you in case lightning strikes the ground.

Hiking is a great way to get out of the concrete jungle and into the woods and the wild, to places of natural beauty. Unfortunately, this manner of thinking is shared by millions of people. Following some basic rules will ensure that we all get along and keep the outdoors a place we can enjoy... together.

Take good care of this beautiful land you’re hiking on. The basics are simple: Leave no trace of your visit. Pack out all your trash. Do your best not to disturb animal or plant life. Don’t collect specimens of plants, wildlife, or even pine cones. Never, ever carve anything into the trunks of trees. If you’re following a trail, don’t cut the switchbacks. Leave everything in nature exactly as you found it, because each tiny piece has its place in the great scheme of things.

You can go the extra mile, too. Pick up any litter that you see on the trail. Teach your children to do this as well. Carry an extra bag to hold picked-up litter until you get to a trash receptacle, or just keep an empty pocket for that purpose in your day pack or fanny sack.

If you have the extra time or energy, join a trail organization in your area or spend some time volunteering in your local park. Anything you do to help this beautiful planet will be repaid to you, many times over.

When hiking with others, and especially over several days, it pays to do a little planning and a lot of communicating. Here are some tips to having a successful trip:

The destination and activities must be agreed upon. A meeting of the minds gives everybody an equal stake in the trip.

If backpacking, guarantee yourself refreshing sleep. Make certain that your sleeping bag, pillow, pad, and tent are clean, dry, warm, and comfortable.

Develop technical expertise. Test all gear at home before putting it to use on the trail.

Guarantee yourself action. Pick a destination with your favorite activity: adventuring, wildlife watching, swimming, fishing...

Guarantee yourself quiet time. Savor the views and the sound of a stream running free, and reserve time with people you care for, and your soul will be recharged.

Accordance on food. Always have complete agreement on the selections for each meal, and check for allergies.

Agree on a wake-up time. Then when morning comes, you will be on course from the start.

Equal chances at the fun stuff. Many duties can be shared over the course of a trip, such as navigating and preparing meals.

Be aware, not self-absorbed. Live so there can be magic in every moment, with an awareness of the senses: sight, sound, smell, touch, taste, and how you feel inside. Have an outlook that alone can promote great satisfaction.

No whining. You can’t always control your surroundings, only your state of mind.

Dogs are wonderful friends and great companions. But dogs and nature do not mix well. Bless their furry little hearts, most dogs can’t help but disturb wildlife, given half a chance. Even if they don’t chase or bark at wildlife, dogs leave droppings that may intimidate other mammals into changing their normal routine. But kept on a leash, a dog can be the best hiking companion you could ask for.

Dogs are allowed on some trails in California and not on others. For many dog owners, it’s confusing. When using this book, check the User Groups listing under each trail listing to see whether dogs are permitted. Always call the park or public land in advance if you are traveling some distance with your dog. Here are general guidelines to park rules about dogs:

If you are visiting a national or state park, 99 percent of the time, your dog will not be allowed to hike with you. There are only a few exceptions to this rule within the national and state park systems. Dogs are usually allowed in campgrounds or picnic areas, but they are not allowed on trails in these parks. If you are planning to visit a national or state park, consider leaving your dog at home.

At other types of parks (county parks, regional parks, and so on), dogs may or may not be allowed on trails. Always follow and obey a park’s specific rules about dogs. Oftentimes, if dogs are allowed, they must be on a six-foot or shorter leash. Don’t try to get away with carrying the leash in your hand while your dog runs free; rangers may give you a ticket.

In national forest or wilderness lands, dogs are usually permitted off leash, except in special wildlife management areas or other special-use areas. Understand that your dog should still be under voice control—for his or her safety more than anything. The outdoors presents many hazards for dogs, including mountain lions, porcupines, black bears, ticks, rattlesnakes, and a host of other potential problems. Dogs are frequently lost in national forest areas. Keeping your dog close to your side or on a leash in the national forests will help you both have a worry-free trip and a great time.

Check to make sure your dog is allowed on a trail.

Although many regions of California exist where you can hike without seeing another soul, even on holiday weekends, some of our better-known parks and public lands are notorious for crowds. No matter where in California you want to hike, there’s no reason to subject yourself to packed parking lots, long lines of people snaking up and down switchbacks, and trail destinations that look like Times Square on New Year’s Eve. If you take a few simple steps, you can avoid the crowds almost anywhere, even in well-traveled parks near urban areas and in our famous national parks.

Hike in the off-season. For most public lands, the off-season is any time other than summer, or any time when school is in session. Late September through mid-May is an excellent period of time for hiking trips (except during the week between Christmas and New Year’s and Easter week). Try to avoid periods near holidays; many people try to beat the crowds by traveling right before or after a holiday, and the result is more crowds.

Time your trip for midweek. Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday are always the quietest days of the week in any park or public land.

Get up early. Even Yosemite Valley is serene and peaceful until 8 or 9am. In most parks, if you arrive at the trailhead before 9am, you’ll have the first few hours on the trail all to yourself. As an insurance policy, get to the trailhead even earlier.

If you can’t get up early, stay out late. When the days are long in summer, you can hike shorter trails from 4pm to 7:30pm or even later. You may see other hikers in the first hour or so, but they’ll soon disperse. Trailhead parking lots are often packed at 1pm, then nearly empty at 5pm. Note that if you hike in the late afternoon or evening, you should always carry a flashlight with you (at least one per person), just in case it gets dark sooner than you planned.

Get out and hike in foul weather. Don your favorite impermeable layer, and go where fair-weather hikers dare not go. Some of the best memories are made on rainy days, cloudy days, foggy days, and days when the wind blows at gale force. The fact is, the vast majority of hikers only hike when the sun is out. Witness nature in all its varied moods, and you may be surprised at how much fun you have.