The rocky points of Mount Roosevelt rise above Snow Lake (Hike 29).

The rocky points of Mount Roosevelt rise above Snow Lake (Hike 29).

DISTANCE: 4.8 miles

ELEVATION GAIN: 3000 feet

HIGH POINT: 5220 feet

DIFFICULTY: Hard

HIKING TIME: 4 to 6 hours

BEST SEASON: Late spring to late fall

TRAIL TRAFFIC: Moderate foot traffic

PERMIT: Northwest Forest Pass

MAPS: USGS Bandera; Green Trails Bandera No. 206

TRAILHEAD GPS: 47.42463°N, 121.5833°W

NOTE: Parking can be a challenge during summer. Arrive early or be prepared to park up to 0.25 mile away on Forest Road 9031.

GETTING THERE: From I-90 between North Bend and Snoqualmie Pass, take Exit 45. Eastbound turn left to go under the freeway and join the westbound exit, following FR 9030 as it veers left and continues 0.9 mile to a fork. Veer left onto FR 9031 and follow it for 2.9 miles until the road terminates at the Ira Spring Trailhead. Privy available.

Why stick to only the most popular mountaintops and lakesides? Putrid Pete’s Peak is a fun alternative to nearby Mason Lake and Bandera Mountain. Short and steep, this hike is a workout. The trail builders were much more interested in expedience than preserving your knees. Bring along some poles, especially for the descent, which can be tricky: many rocks are loose, making it easy to slip and lose your footing on the uneven ground or send boulders careening down the slopes. You’re unlikely to find a great deal of company on this hike, but it affords many of the same views as other, more popular trails nearby.

From the trailhead, begin along the Ira Spring (Mason Lake) Trail #1038, which follows an abandoned roadbed for 0.2 mile. Here, where the Ira Spring Trail heads right to its first switchback up Mount Defiance, continue straight into the trees following a faint boot path. This unmarked trail is unofficial, though well maintained and easily followed once you’re on it. Avoid paths that branch to the left and lead down the mountain. Some of these trails lead up to Dirty Harry’s Peak, and others snake down to I-90.

Continue onward, upward, and always to the right, reaching an unsigned junction at 1.0 mile. The trail straight ahead leads to Dirty Harry’s Balcony; instead, turn right, directly uphill, and begin climbing steeply, eventually breaking free of the trees into rocky meadows of bear grass and wildflowers in season. As you leave the trees, the path becomes patchy and thin; keep heading up, and you’ll soon find yourself on a minor ridge leading directly to your destination.

Clamber up the piles of rocks at the top of the peak and peer carefully over the edge; there’s quite a drop into the bowl that cups Spider Lake below. Look west toward West Defiance (aka Web Mountain), Mount Washington, and Dirty Harry’s Balcony just above I-90 as it disappears into the lowlands. To the north, the peaks of the Alpine Lakes Wilderness rise out of a vast blanket of green—and on good days, you can also pick out Mounts Adams and Baker and Glacier Peak. The view to the east is dominated by Mount Defiance, with Bandera Mountain close behind. And directly across the valley sits the unmistakable horn of McClellan Butte and its neighbors to the east, Mount Kent followed by Mount Gardner. Find a place out of the wind to soak up the views and add your name to the summit registry.

A couple of well-worn unofficial paths lead down the mountainside toward I-90 to a short spur off Exit 42, a winter trailhead for the Ira Spring (Mason Lake) Trail when the main trailhead is snowed in. You can also continue on the trail at the 1.0-mile junction to head out to Dirty Harry’s Peak, Dirty Harry’s Balcony, and Web Mountain.

This little bump was named in honor of Pete Schoening, a Seattle-area mountaineer and outdoorsman who is most famous for his belay on K2 on August 10, 1953. On that day, Schoening managed to arrest the fall of all five members of his roped climbing party with nothing more than an ice axe, stopping them from plunging down the slopes of K2. In the mountaineering community, the legendary event is known simply as “The Belay.” Schoening passed away in 2004, though it seems that Putrid Pete’s Peak was christened sometime before his death by his friends Tom Hornbein and Bill Sumner. References to Putrid Pete begin around 2001, which is probably when the registry was placed at the summit. Many thanks to the Schoening family for helping us piece this story together.

Looking north from the summit of Putrid Pete’s Peak to Spider Lake and Pratt River Valley

There is often some confusion regarding the names of the high points along this ridge. To clarify, Banana Ridge runs northwest from the top of Mount Defiance to another peak known as both West Defiance and Web Mountain. Putrid Pete’s Peak, or P3, lies between the two ends of the ridge, and a few sources dubbed it Middle Defiance before 2001.

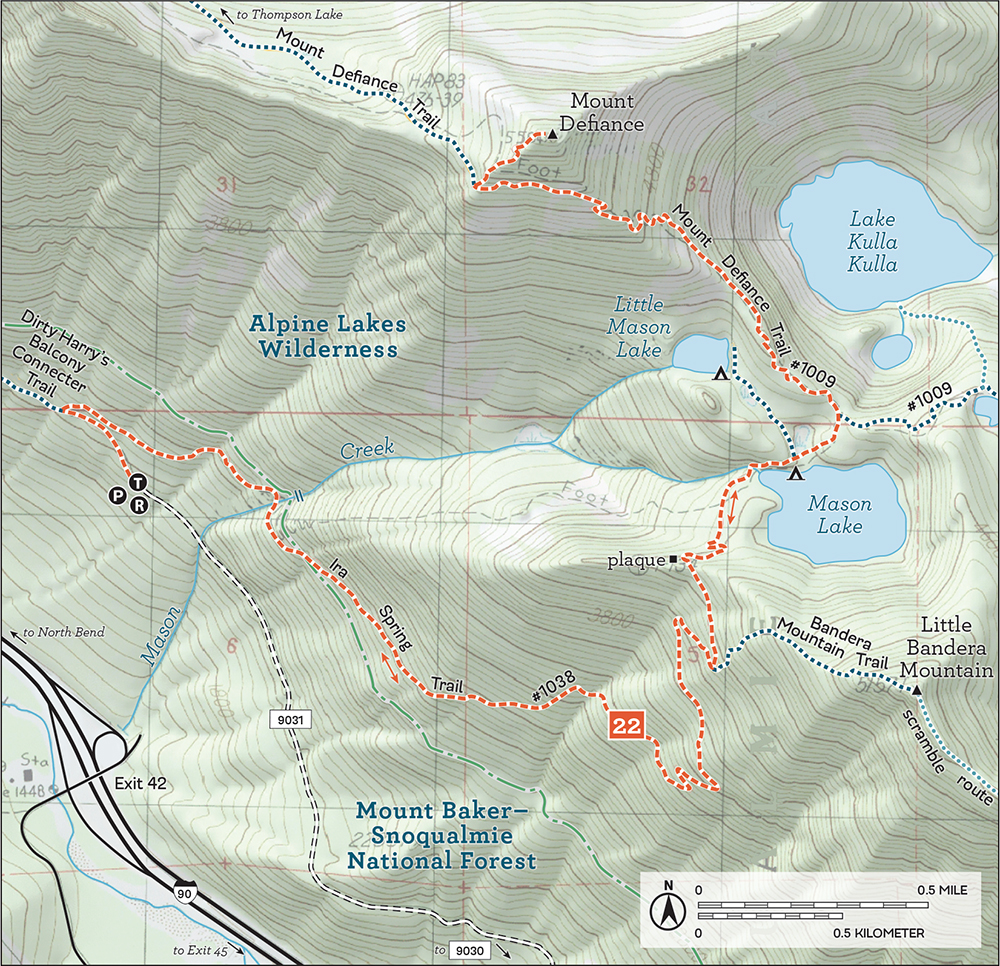

DISTANCE: 6.8 miles to Mason Lake; 10.4 miles to summit of Mount Defiance

ELEVATION GAIN: 2100 feet to Mason Lake; 3400 feet to Mount Defiance

HIGH POINT: 4300 feet Mason Lake; 5584 feet Mount Defiance

DIFFICULTY: Moderate to Mason Lake; hard to Mount Defiance

HIKING TIME: 6 to 7 hours for Mount Defiance

BEST SEASON: Late spring to early fall

TRAIL TRAFFIC: Heavy foot traffic to Mason Lake; moderate to Mount Defiance

PERMIT: Northwest Forest Pass

MAPS: USGS Bandera; Green Trails Bandera No. 206

TRAILHEAD GPS: 47.42463°N, 121.5833°W

NOTE: Parking can be a challenge during summer. Arrive early or be prepared to park up to 0.25 mile away on Forest Road 9031.

GETTING THERE: From I-90 between North Bend and Snoqualmie Pass, take Exit 45. Eastbound turn left to go under the freeway and join the westbound exit, following FR 9030 as it veers left and continues 0.9 mile to a fork. Veer left onto FR 9031 and follow it for 2.9 miles until the road terminates at the Ira Spring Trailhead. Privy available.

Accessible and not too challenging, Mason Lake is one of the more popular destinations in this region and a gateway to a number of other nearby destinations. Big and beautiful Mason Lake provides a window into the wilderness, inspiring hikers and would-be backpackers to delve deeper. Those who are thirsty for a vista can continue up to the summit of Mount Defiance, where you are richly rewarded with sprawling views of the Alpine Lakes Wilderness as well as a bird’s-eye view of the Snoqualmie Valley below.

The Ira Spring Memorial Trail cuts through talus and fields of beargrass.

From the trailhead, the Ira Spring (Mason Lake) Trail #1038 begins on the bones of a repurposed fire road, with a grade suitable for conveying heavy machinery up a mountainside. You’ll cross a few streams including Mason Creek, entering the Alpine Lakes Wilderness before 1.2 miles.

At 1.5 miles the trail leaves the young forest behind for a much steeper path up the mountain. The dusty trail moves beyond the evergreens for ever-larger glimpses of the valley below, and once the trail sheds the last of the trees, enormous views are your compensation for being fully exposed to the elements.

At 2.9 miles, reach the junction with the Bandera Mountain Trail (Hike 23) to the right. Stay left to continue upward to the west through subalpine meadows and talus fields, passing the Ira Spring Memorial plaque just before the short descent to Mason Lake, reached at 3.4 miles. The lakeshore offers an abundance of campsites and the possibility of a refreshing dip. This big lake has a lot of room, so keep walking to find a quiet spot to claim. This is a gorgeous place for picnicking or splashing in the water on a sunny summer afternoon.

Picturesque Mason Lake is a tempting place to stay, though there is plenty more to see. It’s another 1.8 miles up to the summit of Mount Defiance, reached by following the trail around Mason Lake to the junction with the Mount Defiance Trail #1009. Veer left onto rougher trail, climbing through the trees over rocks and roots before eventually reaching the meadows of Mount Defiance, famously brimming with lush fields of wildflowers in the late spring and early summer. Watch for a small rock cairn at 5.0 miles marking the spur trail to the right to the summit. From here it’s a short 0.2-mile climb to the top. On the best of days, you can see five volcanic peaks: Adams, Baker, Glacier, Rainier, and St. Helens. Lakes are liberally sprinkled throughout the bowl between Bandera and Defiance—Lake Kulla Kulla is the largest, with Blazer Lake and Rainbow Lake just to the east. Little Mason Lake is nestled below familiar Mason Lake. To the northeast you can make out a portion of Pratt Lake (Hike 26) resting at the base of Pratt Mountain.

To beat the crowds at Mason Lake, consider a side trip up to Little Mason Lake, a short jaunt up from the main trail. There are also other nearby lakes found by following the Mount Defiance Trail east for 1.5 miles past Rainbow Lake to the Island Lake spur (Hike 24). Alternatively, you can reach Thompson Lake (Hike 1) from the top of Mount Defiance by following the Mount Defiance Trail as it continues northwest down the other side of the mountain, dropping 1400 feet over 2.8 miles.

Since it was first blazed in 1958, the trail known today as the Ira Spring (Mason Lake) Trail has had a reputation for being steep and dirty. Over the years, thousands of boots badly eroded the trail, and hikers were forced to negotiate long uphill stretches over rocks and boulders. At the urging of wilderness advocate Ira Spring, a new route was proposed to address the trail damage, the steep grade, and the rocky obstacle course. In 2003 and 2004, volunteers in coordination with the Forest Service made the new trail a reality. With Ira Spring’s passing in 2003, the trail was dedicated the Ira Spring Memorial Trail.

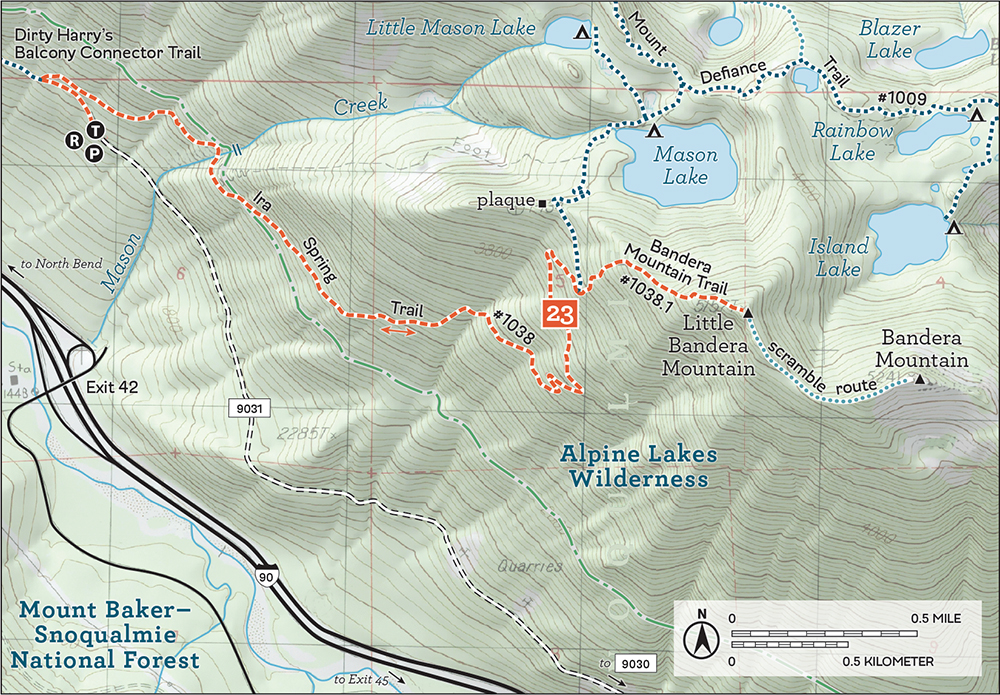

DISTANCE: 6.8 miles

ELEVATION GAIN: 2900 feet

HIGH POINT: 5157 feet

DIFFICULTY: Moderate

HIKING TIME: 4 to 5 hours

BEST SEASON: Early spring to early fall

TRAIL TRAFFIC: Heavy foot traffic

PERMIT: Northwest Forest Pass

MAPS: USGS Bandera; Green Trails Bandera No. 206

TRAILHEAD GPS: 47.42463°N, 121.5833°W

NOTE: Parking can be a challenge during summer. Arrive early or be prepared to park up to 0.25 mile away on Forest Road 9031.

GETTING THERE: From I-90 between North Bend and Snoqualmie Pass, take Exit 45. Eastbound turn left to go under the freeway and join the westbound exit, following FR 9030 as it veers left and continues 0.9 mile to a fork. Veer left onto FR 9031 and follow it for 2.9 miles until the road terminates at the Ira Spring Trailhead. Privy available.

As prominences and high points go, Bandera Mountain is among the best, offering sprawling 360-degree views of the Alpine Lakes Wilderness and Snoqualmie Valley. Less popular than nearby summits that offer a little more space at the top, Bandera is a welcome challenge for those looking for new peaks to bag.

From the trailhead, follow the Ira Spring (Mason Lake) Trail #1038, which starts casually, following a repurposed logging road. Work your way through young forest, crossing a few streams before entering the Alpine Lakes Wilderness at 1.2 miles.

At 1.5 miles, leave the gentle logging road and begin the hike in earnest; the grade sharpens and begins a series of tight switchbacks. Whatever time of year, this section of the trail offers a front-row seat to an ever-expanding mountainous panorama, courtesy of the fires that have kept much of the mountainside free of trees.

At 2.9 miles reach a junction with the Bandera Mountain Trail #1038.1. Keep right here, continuing to traverse along the mountain’s shoulders. Once you reach the ridgeline, peek over the edge at Mason Lake (Hike 22) tucked in a bowl beneath Mount Defiance. Follow the rocky path to the top of Little Bandera Mountain at 3.4 miles to find a sprawling vista. That’s Island Lake below (Hike 24), and Mount Rainier presides over a sprawling landscape of lesser peaks. McClellan Butte and Mount Gardner are just across the snaking ribbon of I-90. You can make out the rocky outcroppings of Dirty Harry’s Balcony just above I-90 to the west. Find a rock and take in your hard-earned panorama.

Looking west from the summit of Little Bandera toward with the sharp point of McClellan Butte above the freeway as it snakes toward North Bend

While Little Bandera is the usual stopping point, it’s not the true summit. Reach the latter by scrambling east along the ridgeline as it drops slightly before working its way to the next prominence, about 100 feet higher than the first. From the true summit, there are better views of Granite Mountain (Hike 27) and Snoqualmie Pass.

After a long climb up to Bandera’s upper reaches, a quick dip in Mason Lake (Hike 22), only 0.5 mile past the Ira Spring–Bandera junction, might be welcome.

Bandera has long been a name entwined with the history of Snoqualmie Pass. Though the mountain was officially recognized by the US Board on Geographic Names as Bandera Mountain only in 1920, a nearby train station along the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul, and Pacific Railroad named “Bandera” had been operating since 1909 and continued service until 1980. In 1948, the Bandera Airstrip was dedicated, marking the first emergency airfield in the Snoqualmie Pass area; it is still actively used today. The original trail up the mountain was first blazed to provide access for crews fighting a large fire around Mason Lake in the summer of 1958 and was later popularized by the late Harvey Manning.

DISTANCE: 10.2 miles

ELEVATION GAIN: 2500 feet

HIGH POINT: 4400 feet

DIFFICULTY: Moderate

HIKING TIME: 5 to 8 hours

BEST SEASON: Late spring to early fall

TRAIL TRAFFIC: Heavy foot traffic to Mason Lake; light foot traffic to Island Lake

PERMIT: Northwest Forest Pass

MAPS: USGS Bandera; Green Trails Bandera No. 206

TRAILHEAD GPS: 47.42463°N, 121.5833°W

NOTE: Parking can be a challenge during summer. Arrive early or be prepared to park up to 0.25 mile away on Forest Road 9031.

GETTING THERE: From I-90 between North Bend and Snoqualmie Pass, take Exit 45. Eastbound turn left to go under the freeway and join the westbound exit. following FR 9030 as it veers left and continues 0.9 mile to a fork. Veer left onto FR 9031 and follow it for 2.9 miles until the road terminates at the Ira Spring Trailhead. Privy available.

Quiet and only a little deeper in the wilderness than Mason Lake, Island Lake offers a more enchanting setting: little islands dot tranquil waters overshadowed by talus fields strewn down the shoulders of Bandera Mountain (Hike 23). The hike to Island Lake is great if you’re ready to move beyond more popular and well-trodden trails. While the first two-thirds of the route are likely to be crowded, as you push past the Bandera Mountain Trail junction and Mason Lake, you’ll soon find yourself almost entirely alone. Island Lake and Rainbow Lake also work as quick backpacking destinations, since you can be setting up camp on the quiet shores of a lovely alpine lake in fairly short order.

From the Ira Spring Trailhead, follow the Ira Spring (Mason Lake) Trail #1038 on an abandoned road as it wanders through a young forest still recovering from fires that ravaged the mountain as recently as 1958. The trail slowly works its way up the slopes, crossing Mason Creek and its waterfall before entering the Alpine Lakes Wilderness at 1.2 miles.

At 1.5 miles, the logging road is replaced by serious trail, exchanging the road’s gentle grade for a steep, rocky path. After a short climb, the dusty trail moves beyond the conifers for everlarger glimpses of the valley below. Once the trail sheds the last of the trees, enjoy the enormous views that come with traversing a grassy mountainside.

At 2.9 miles, reach the junction with the Bandera Mountain Trail to the right. Head left through subalpine meadows and talus fields, reaching the Ira Spring Memorial plaque just before the short descent to Mason Lake, at 3.4 miles. The lakeshore offers plenty of nooks to take in the sparkling waters, and it’s tempting to remain here. But your destination lies beyond.

Push onward, following the trail along the lake and farther from the shore to reach the Mount Defiance Trail #1009 (Hike 22). Keep right and soon find yourself wandering through peaceful tree-lined meadows. Pass Rainbow Lake at 4.6 miles and reach the signed junction to Island Lake at 4.8 miles. From here it’s just a 0.3-mile jaunt past a few tarns to sparkling Island Lake, resting quietly below Bandera Mountain. Find a cozy rock and enjoy a slice of tranquility.

The Mount Defiance Trail continues eastward to connect with the Pratt Lake Trail #1007, providing access to Olallie Lake, Talapus Lake, and Pratt Lake (Hikes 25 and 26). These two trails also allow for a through-hike with a shuttle vehicle at the Pratt Lake/Granite Mountain Trailhead (Hikes 26 and 27).

Island Lake tempts swimmers during the summer heat.

Before the 1960s, the only way for hikers to reach Island Lake was to start at the Pratt Lake/Granite Mountain Trailhead and trek out to the Mount Defiance Trail junction. Named for the lake’s small rocky island, Island Lake used to see many more visitors than it does today, and distant Mason Lake was a side trip for those heading to the top of Mount Defiance. That changed in 1958 when a large wildfire on the slopes of Bandera Mountain prompted crews to hastily build a fire road to help fight the blaze. Not too long after, curious hikers explored the area and used it as a back door to Mason Lake and an approach to Bandera Mountain. Harvey Manning popularized the route, and soon the official Mason Lake Trail #1038 was born.

Much loved over the years, the trail was in desperate need of repairs by the turn of the twentieth century. Ira Spring advocated for a new route, which was built between 2003 and 2004 and renamed the Ira Spring Memorial Trail #1038 after his passing.

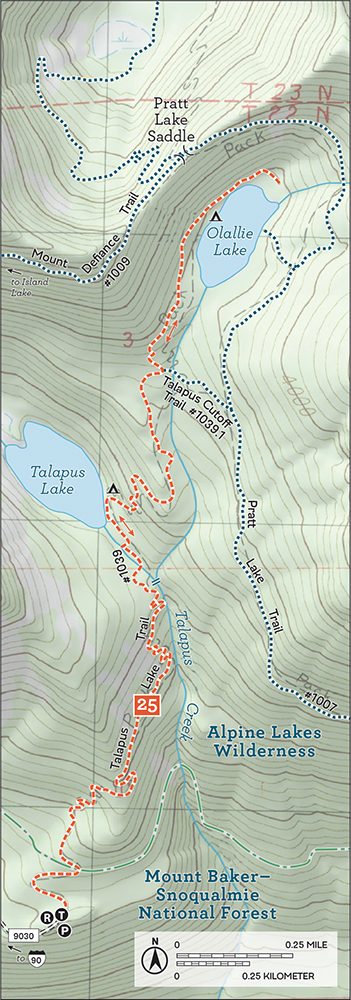

DISTANCE: 5.8 miles

ELEVATION GAIN: 1200 feet

HIGH POINT: 3800 feet

DIFFICULTY: Easy

HIKING TIME: 3 to 4 hours

BEST SEASON: Late spring to late fall

TRAIL TRAFFIC: Heavy foot traffic

PERMIT: Northwest Forest Pass

MAPS: USGS Bandera; Green Trails Bandera No. 206

TRAILHEAD GPS: 47.4011°N, 121.5185°W

Talapus Lake from the log-clogged lake outlet

GETTING THERE: From I-90 between North Bend and Snoqualmie Pass, take Exit 45. Eastbound turn left to go under the freeway and join the westbound exit, following FR 9030 as it veers left and continues 0.9 mile to a signed junction with FR 9031 to the left. Keep right, following the sign to Talapus Lake. Continue for 2.3 miles to the trailhead parking lot. Privy available.

Talapus Lake and Olallie Lake deliver alpine lakes, waterfalls, and stretches of deep, mossy forest with minimal mileage. This hike is a popular summer choice with families and young backpackers, and a great introduction to the Alpine Lakes Wilderness, so you can expect a little company. Whatever time of year, the trail provides a tempting taste of the wilderness—stands of old growth, crystalclear alpine lakes, and rugged landscapes make it easy to forget the relatively close trappings of civilization.

From the trailhead, follow Talapus Lake Trail #1039 on an old forest road into secondgeneration forest. Wander beneath stands of young trees before leaving the wide track for more-rugged trail. Soon after, at 0.3 mile, cross into the Alpine Lakes Wilderness.

As you climb, the trail cuts through marshy areas along an elaborate system of raised boardwalks and bridges. After navigating mild grades and walkways, the route soon reaches the banks of Talapus Creek. From here, the trail follows the creek to Talapus Lake, passing an impressive waterfall just off the trail at 1.3 miles. Look and listen for the cascade at a sharp bend in the trail just before it angles upward.

At 1.6 miles, reach Talapus Lake tucked in a bowl between Bandera Mountain (Hike 23) and Pratt Mountain. Explore the maze of boot paths snaking around the lake to a handful of campsites and inviting stopping points along the water—perfect for a snack or extended stay.

Once you’ve taken it all in, push onward toward Olallie Lake, following the trail as it meanders peacefully past mature cedars and firs. At the 2.3-mile mark, pass the Talapus Cutoff Trail #1039.1, which offers a quick connection with the Pratt Lake Trail #1007 and access to a number of nearby lakes and prominences.

From the junction, push on another 0.6 mile to reach the wooded shores of Olallie Lake, resting beneath the slopes of West Granite Mountain and Pratt Lake Saddle (Hike 26). Find a quiet spot and settle in to enjoy the solace.

The Talapus Cutoff Trail #1039.1 offers access to nearby Pratt Lake (Hike 26) or Island Lake (Hike 24) via the Pratt Lake Trail. Hikers can also put together a longer through-hike by parking a shuttle vehicle at either the Granite Mountain Trailhead (Hike 27) or the Ira Spring Trailhead (Hike 22).

Like so many place names in the area, Talapus and Olallie Lakes bear the legacy of the early interaction of pioneers and American Indians. Talapus translates to “coyote” in Chinook Jargon, while Olallie roughly means “berry.” Largely born through the necessity of trade, Chinook Jargon is an amalgamation of French, English, and Salishan languages native to the Pacific Northwest.

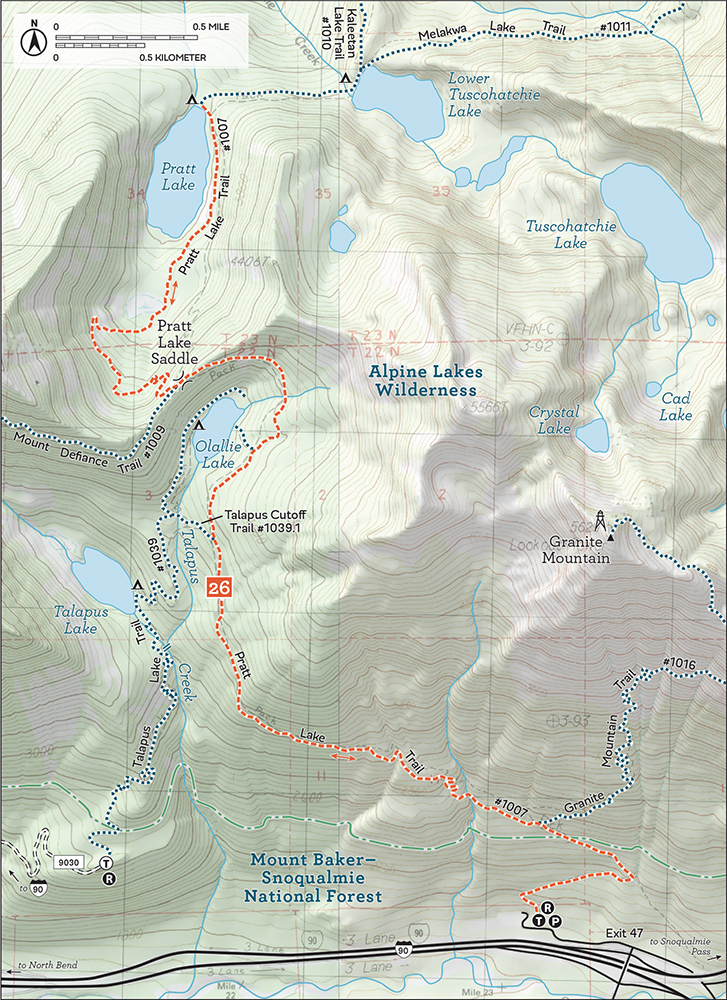

DISTANCE: 11.8 miles

ELEVATION GAIN: 2300 feet in; 750 feet out

HIGH POINT: 4100 feet

DIFFICULTY: Moderate

HIKING TIME: 5 to 7 hours

BEST SEASON: Spring to late fall

TRAIL TRAFFIC: Moderate to light foot traffic

PERMIT: Northwest Forest Pass

MAPS: USGS Bandera; Green Trails Bandera No. 206

TRAILHEAD GPS: 47.39776°N, 121.4865°W

NOTE: Parking can be a challenge much of the year; arrive early to get a spot closer to the trailhead.

GETTING THERE: From I-90 between North Bend and Snoqualmie Pass, take Exit 47. If eastbound, turn left and cross over the freeway to a signed T intersection; if westbound, turn right to this T intersection. At the T, turn left and continue a short distance to the trailhead parking lot. Privy available.

The Pratt Lake Trail is one of the gateways into the Alpine Lakes Wilderness, providing access to many lakes and peaks. A trek out to Pratt Lake leads through dense forest, past dramatic views of Mount Rainier, and over Pratt Lake Saddle to the shores of a wooded alpine lake.

From the trailhead, the Pratt Lake Trail #1007 is well worn and wide, crossing small creeks and rivulets through pleasant stands of maturing firs and pines. Cross into the Alpine Lakes Wilderness at 0.8 mile, and shortly after, at 1.0 mile, reach the junction with the Granite Mountain Trail #1016 on the right. Stay left to continue on the Pratt Lake Trail for the first bit of real elevation gain, skirting the slopes of Granite Mountain (Hike 27) and occasionally catching glimpses of mountaintops through windows in the trees carved by streams and talus fields.

At 2.9 miles, the trail intersects the Talapus Lake Cutoff Trail #1039.1 to the left, which offers access to the shores of both Talapus and Olallie Lakes (Hike 25). Continue straight ahead on the Pratt Lake Trail as it traverses the bowl above Olallie Lake, offering occasional glimpses of the water below. As you make your way around the end of the lake, the trees open up in a talus field to reveal a stunning view of Mount Rainier rising above the water, framed by Pratt Mountain on the right and Bandera Mountain (Hike 23) on the left. This is the best view on the hike, so take a few minutes to enjoy it.

False Solomon’s seal, trillium, and bleeding heart line the trail above Pratt Lake.

Press on up to Pratt Lake Saddle at 4.0 miles, a low point on a shoulder of Pratt Mountain. Soon reach the junction with the Mount Defiance Trail #1009 (Hike 22) to the left; stay to the right to switchback somewhat steeply down through talus fields and sections of marsh and swamp into the Pratt Lake Basin. The trail breaks out of the trees and traverses the rocky slopes above the lake. Continue to the far end of the lake for the best campsites and lake views at 5.9 miles. Find a quiet spot to settle in and enjoy this pristine setting.

The Pratt Lake Trail continues past the end of Pratt Lake for another 0.5 mile out to Lower Tuscohatchie Lake. From there, hikers can take the Kaleetan Lake Trail #1010 left up to its namesake lake or the Melakwa Lake Trail #1011 to the right to head up to Melakwa Lake (Hike 28).

Adventurous backpackers and throughhikers can follow the Old Pratt Lake Trail into the Pratt Valley, though this unmaintained section between Pratt Lake and the end of the Pratt River Trail #1035 (Hike 5) requires some bushwhacking and routefinding. Once you reach the Pratt River Trail, you can follow it all the way out to the Middle Fork Snoqualmie River.

In 1897, a trail was blazed up the Pratt River Valley, past Pratt Lake and on to Melakwa Lake, to access mining claims on Chair Peak. Back then, the Pratt River was known as Tuscohatchie Creek, and Pratt Lake was labeled “Ollie Lake” on USGS maps. Sometime before 1916, The Mountaineers named the lake in honor of one of their own, John W. Pratt, and got the maps changed by 1917. Older maps show a “Twilight Camp” near Pratt Lake along the Pratt Lake Trail, most likely a long-gone mining camp. By the 1950s, the Pratt River Valley approach was largely abandoned, and hikers reached the lake by pushing past Olallie Lake and climbing over Pratt Lake Saddle.

DISTANCE: 8.6 miles

ELEVATION GAIN: 3700 feet

HIGH POINT: 5629 feet

DIFFICULTY: Hard; see note about avalanche hazard in trail description

HIKING TIME: 5 to 7 hours

BEST SEASON: Late spring to early fall

TRAIL TRAFFIC: Heavy foot traffic

PERMIT: Northwest Forest Pass

MAPS: USGS Snoqualmie Pass; Green Trails Snoqualmie Pass No. 207

TRAILHEAD GPS: 47.39776°N, 121.4865°W

NOTES: Parking can be a challenge much of the year at this popular trailhead; arrive early to get a spot closer to the trailhead. Spring avalanches have taken lives on Granite Mountain; use extra caution early in the season.

The sprawling view from the Granite Mountain Lookout includes Mount Rainier and a sea of other mountaintops.

GETTING THERE: From I-90 between North Bend and Snoqualmie Pass, take Exit 47. If eastbound, turn left and cross over the freeway to a signed T intersection; if westbound, turn right to this T intersection. At the T, turn left and continue a short distance to the trailhead parking lot. Privy available.

As the years pass and the lookout towers of a bygone era slowly disappear, the ones that remain draw hikers up steep mountainsides. They come not only to share the lookout’s commanding views but also to connect to a time before satellites and aerial photography, when it was vitally important to maintain a small battalion of watchful eyes perched upon mountaintops, scanning the horizon for wildfire smoke. At 5629 feet, Granite Mountain is one of the most easily accessible and popular summits in the Snoqualmie Pass region. Still, this hike can be challenging. In summer, the sun beats down on exposed rocks and meadows, making the trail dusty without much available water once the snow melts. During the spring, avalanches have taken the lives of hikers on Granite, so use extra caution early in the season. The uphill trek to Granite’s fire lookout tower makes for a long day, but the views from the top are more than ample reward.

From the trailhead, follow the Pratt Lake Trail #1007 as it rolls through lush forests of cedar and Douglas fir, frequently crossing creeks and streamlets along the way. Cross into the Alpine Lakes Wilderness at 0.8 mile and soon after, at 1.0 miles, reach the junction with the Granite Mountain Trail #1016. Turn right toward Granite Mountain.

Immediately the tenor of the trail shifts from an uphill amble to a thigh-burning workout. Navigate the rocky trail as it switchbacks through the increasingly dry terrain, and catch the occasional glimpse of your eventual goal high overhead. As you gain elevation, trees thin and become more diminutive while ferns yield to bear grass and mountain blueberry. Eventually you leave the trees entirely behind; the views are laid bare, breezes keep the bugs at bay during the summer, and the trail grade relents slightly as the fire lookout comes into view.

Climb, climb, and climb some more, working your way up to the base of the summit bluff. When snow is on the ground, follow the bootprints up the spine of the talus-covered ridge straight to the summit, avoiding most avalanche danger. As the snow recedes, the rocky ridge is less appealing than the formal trail that snakes beneath the ridge before zigzagging up the bluff the lookout resides upon. Whichever path you take, arrive at the boulder-strewn lookout at 4.3 miles from the trailhead.

The views that began hundreds of feet below culminate as you attain the lookout, snowy mountaintops spreading out with a mesmerizing immensity. Mount Rainier dominates the skyline, in every way demanding attention and dwarfing Mount Catherine and Humpback Mountain just across I-90 far below. If you can tear your eyes off Rainier, the beginnings of Keechelus Lake can be seen to the east, and Bandera Mountain (Hike 23) quietly neighbors to the west. Looking north, your eye is drawn to distinctive Kaleetan Peak, as well as Chair Peak and Mount Stuart far beyond, and just below, Crystal Lake and Tuscohatchie Lake gleam invitingly in the sunlight.

First established in 1920, Granite Mountain’s fire lookout began as a flimsy cabin that was rebuilt and elevated in 1924. When the snow melts, the cement foundations of the 1924 cabin can still be seen near the current operational lookout tower, which was built in 1955 and is staffed by the Forest Service during the summer.

DISTANCE: 8.5 miles

ELEVATION GAIN: 2300 feet

HIGH POINT: 4600 feet

DIFFICULTY: Moderate

HIKING TIME: 5 to 8 hours

BEST SEASON: Late spring to late fall

TRAIL TRAFFIC: Heavy foot traffic

PERMIT: Northwest Forest Pass

MAPS: USGS Snoqualmie Pass; Green Trails Snoqualmie Pass No. 207

TRAILHEAD GPS: 47.41525°N, 121.4433°W

NOTES: Parking is challenging during high season. The hike up to Melakwa Lake requires crossing Denny Creek; use caution during high water.

GETTING THERE: From I-90 between North Bend and Snoqualmie Pass, take Exit 47. If eastbound, turn left to cross over the freeway to a signed T intersection; if westbound, turn right to this T intersection. At the T, turn right, heading under the freeway for 0.25 mile to Forest Road 58. Turn left on FR 58 and follow it for 2.5 miles to Denny Creek Campground. Just past the entrance to the campground, turn left onto FR 5830 for 0.25 mile to the road-end trailhead and parking. Privy available.

Trek up to a secluded alpine lake, flanked by sentinels of craggy granite on this hike through talus, forest, and—if your timing is right—wildflower meadows. The trail also leads to the Denny Creek Waterslide, an area along the creek where the water flows over “slippery slabs” of granite to create a popular place for splashing and playing in the summer. The steep climb to charming Melakwa Lake doesn’t dissuade thousands of hikers from visiting the lake every year. Though extra company does not diminish the beauty of the hike, plan an early start or a weekday venture to avoid the thickest crowds. On the plus side, all those boot steps keep the trail hardpacked and in decent shape, as do the volunteers who work hard to maintain this well-loved trail.

From the trailhead, follow the wide, well-trodden Denny Creek Trail #1014 through overarching trees into deep old-growth forest. Cross Denny Creek over a sturdy bridge and work toward the increasing din of I-90 as the trail approaches the elevated freeway. The roar of cars grows as you pass under the causeway at 0.5 mile and veer up into the creek valley, every step leaving the noise a little farther behind.

Before long, reunite with the creek at the wilderness boundary at 0.9 mile, followed soon after by the Denny Creek Waterslide 1.1 miles from the trailhead. There is no bridge here, though crossing during the summer should not pose much challenge. Heed the warning signs cautioning against a crossing during high water. The slabs that are such fun to slide down during the summer are treacherous to cross when icy water is blasting down the creek.

Across the creek, the trail continues through sheltering forest before leaving the trees for expansive meadows. At 1.7 miles, find lovely views of Keekwulee Falls dropping more than 140 feet into the basin below. Enjoy the waterfall and surrounding slopes splashed with swaths of verdant green before continuing onward, as the trail is about to become much steeper.

From the falls, the trail steeply switchbacks through talus and occasional patches of trees. As you climb, you may hear or catch a glimpse of Snowshoe Falls, the highest Denny Creek has to offer. These 150-foot falls are difficult to see from the trail itself and may require some offtrail effort to fully appreciate. The trail momentarily relents to cross Denny Creek once again on a log bridge before again switchbacking up to Hemlock Pass at 3.8 miles.

From the pass, drop slightly for another 0.4 mile to Melakwa Lake, passing a signed junction with the Melakwa Lake Trail #1011, which leads down to Lower Tuscohatchie Lake and Pratt Lake (Hike 26). Reach Melakwa Lake and cross the logjam of silver snags clogging the outlet to reach a heavily used camping area. The lake lies in a narrow cirque, nestled between the jagged mountaintops of Chair Peak and Bryant Peak on the eastern shore and Kaleetan Peak to the west. A thin band of trees clutches the shoreline, dividing the water from the vast talus fields that cover the slopes.

Just to the north, Upper Melakwa Lake hides behind a few trees and serves as the source of the Pratt River. Wander around the lakes to find a quiet spot to enjoy this quintessential alpine setting.

A hike to Melakwa Lake all but requires a visit to Upper Melakwa Lake, which can be reached by following a boot path circling around the west side of the lake for 0.2 mile. From Upper Melakwa Lake, the adventuresome can scramble up to Melakwa Pass at the head of the cirque and from there continue a more technical scramble up to Kaleetan Peak. Another option is to continue to follow the Melakwa Lake Trail down to Lower Tuscohatchie Lake.

Push past the busy day-use area to pretty Upper Melakwa Lake and views of Melakwa Pass.

Most of the features in this area were named by The Mountaineers, and the names were officially submitted in 1916. They named the lake Melakwa, which means “mosquito” in Chinook Jargon, for reasons that become very obvious during the late spring and early summer. They also named one of the falls Keekwulee, which means “to fall down” or “low/below,” both apt meanings. Denny Creek was named for David T. Denny, brother of Arthur Denny, who had claims along the creek in 1890. As The Mountaineers climbed, they may have been more focused on the hike than the names, since they christened Snowshoe Falls for the snowshoes they had on and Hemlock Pass for the trees growing there. A few years later, in 1924, The Mountaineers gave Bryant Peak its name honoring Sidney Bryant, a member of The Mountaineers who helped spearhead the construction of their Snoqualmie Lodge.

DISTANCE: 6.3 miles

ELEVATION GAIN: 1300 feet in; 400 feet out

HIGH POINT: 4400 feet

DIFFICULTY: Moderate

HIKING TIME: 4 to 6 hours

BEST SEASON: Late spring to late fall

TRAIL TRAFFIC: Heavy foot traffic

PERMIT: Northwest Forest Pass

MAPS: USGS Snoqualmie Pass; Green Trails Snoqualmie Pass No. 207

TRAILHEAD GPS: 47.4454°N, 121.4235°W

GETTING THERE: Take I-90 to Snoqualmie Pass. Eastbound take Exit 52 and turn left onto Alpental Road for about 2 miles to a large gravel parking lot. Westbound take Exit 53, turning left under the freeway and soon reaching a T intersection. Turn right onto State Road 906, following the sign pointing toward Alpental. Continue 2.7 miles through the ski area to the parking area. The trailhead is across the road to the right. Privy available.

Snow Lake is one of the largest lakes in the Alpine Lakes Wilderness, as well as one of the most easily accessible. As a result, this enormously popular trail attracts hundreds of hikers every sunny weekend. While there is plenty of lake to accommodate the visitors, the short trip out to Source Lake provides a stretch of trail time that you are unlikely to have to share.

From the trailhead, Snow Lake Trail #1013 begins mildly, cutting a long swath through fields of bracken fern and salmonberry before entering a forest of hemlock and fir. As you slowly gain elevation, navigate your way across talus fields and cascading streams. Enjoy the well-trod path, beaten down by tens of thousands of boots every year that keep it clear of debris and encroaching brush.

At 1.7 miles, the trail meets up with Source Lake Trail #1013.2 signed “Source Lake Overlook Trail,” which was the primary route to Snow Lake before washouts prompted building a more direct route over the cliffs. Stay to the right on the Snow Lake Trail, following the newer route to the lake.

The climb up the Snow Creek headwall includes impressive views of Bryant Peak and other summits around Source Lake.

Switchback steeply up the rocky ridge, crossing into the Alpine Lakes Wilderness and reaching the ridgetop at a saddle at 2.5 miles. At the saddle is another junction with the Source Lake Trail to the left; stay right on the Snow Lake Trail to descend to the shores of Snow Lake.

Stretching out over a mile, Snow Lake is large, its placid waters wrapping around Chair Peak, which obscures the lake’s western reaches. The vegetation around the lake is riddled with footpaths, lingering evidence of the multitudes struggling to find their own private slice of solace near the water. At 2.8 miles, pass a short spur out to the water that leads to the foundations of the old Fenton family cabin. Designated campsites are just off the trail as it continues north around the lake.

On the hike back out, reach the junction at the saddle at the 3.3-mile mark. Here, follow the Source Lake Trail to the right to explore the Source Lake Overlook. Largely abandoned since the newer route opened, the trail is rough and unmaintained, though easy to follow. It leads through small alpine meadows, past tiny lakelets, and under a small waterfall—and it is far less crowded than the main trail. By the time Source Lake is in view at 4.2 miles, the trail improves greatly, mostly thanks to adventurous mountaineers scrambling up to the Tooth and Chair Peak located nearby. Continue past the overlook another 0.4 mile to rejoin the Snow Lake Trail and return to the trailhead.

Snow Lake is not only beautiful, it’s very accessible, drawing in thousands of hikers year after year. If solitude is your goal, this is not your trail. At the same time, this is a classic hike and one that every alpine lake lover should experience!

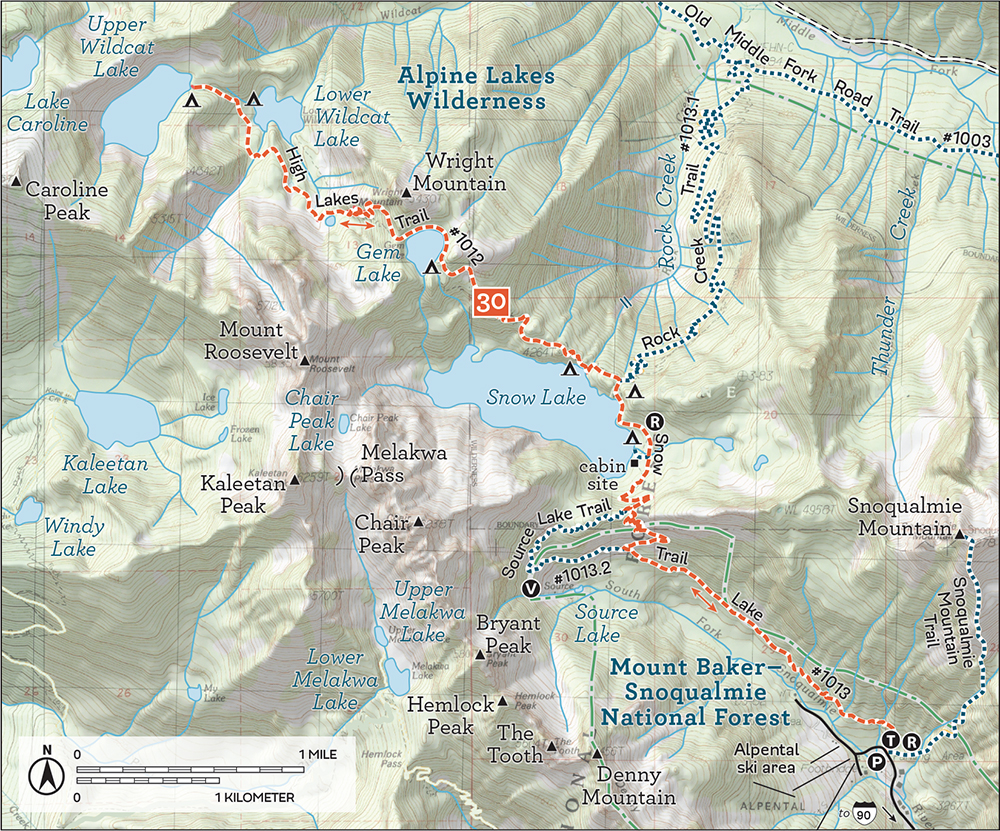

From the cabin site, Gem Lake (Hike 30) is another 1.8 miles down the Snow Lake Trail and High Lakes Trail #1012. While it’s a rocky climb, the tranquil setting is well worth the extra mileage. Alternatively, the junction with the Rock Creek Trail #1013.1 is 0.5 mile down the trail. It’s a short-but-steep drop down to get a decent view of Rock Creek Falls (Hike 14).

Tucked on the slopes of Denny Mountain, the Alpental ski area is the most recent addition to this part of Snoqualmie Pass, having operated here since 1967. Various landlords held fleeting ownership long before, including the mountain’s namesake, Arthur Denny, who staked mining claims in the area while prospecting for iron ore in 1869. Following in Denny’s wake, mining claims proliferated throughout the valley, including along parts of Snow Lake. As the years passed, these claims were sold or abandoned, becoming either part of Alpental or what would become the Alpine Lakes Wilderness.

The cabin on the shores of Snow Lake was built in 1930 by Aldrich Fenton and a band of hired Norwegian carpenters. The private twostory cabin was built for the Fenton family to enjoy, as the family also owned several acres around the lake. After twenty years, the cabin roof collapsed under heavy snows in the winter of 1950, and times were changing. Tired of break-ins and vandalism, the family decided not to rebuild and eventually sold the land. The cabin slowly deteriorated over the years, with only the fireplace and a few sections of wall remaining today.

DISTANCE: 13.8 miles

ELEVATION GAIN: 2500 feet in; 1300 feet out

HIGH POINT: 4900 feet

DIFFICULTY: Hard

HIKING TIME: Overnight

BEST SEASON: Early summer to fall

TRAIL TRAFFIC: Heavy foot traffic to Snow Lake; moderate to light foot traffic on High Lakes Trail

PERMIT: Northwest Forest Pass

MAPS: USGS Snoqualmie Pass; Green Trails Snoqualmie Pass No. 207

TRAILHEAD GPS: 47.4454°N, 121.4235°W

GETTING THERE: Take I-90 to Snoqualmie Pass. Eastbound take Exit 52 and turn left onto Alpental Road for about 2 miles to a large gravel parking lot. Westbound take Exit 53, turning left under the freeway and soon reaching a T intersection. Turn right onto State Route 906, following the sign pointing toward Alpental. Continue 2.7 miles through the ski area to the parking area. The trailhead is across the road to the right. Privy available.

Spend a night on the shores of a lovely alpine lake, not too far from civilization but far enough to feel the solace of the wilderness. With three different lakes to choose from, each a little deeper into the wild, you have a lot of ways to enjoy this backpacking adventure.

From the trailhead, follow the Snow Lake Trail #1013 as it cuts through the underbrush and enters the forest. Slowly climb past firs, hemlocks, and cedars, eventually reaching fields of talus. The path is wide, well worn, and easy to navigate, thanks to the thousands of hikers who pound this trail bed every season. Skip across a few streams and, at 1.7 miles, pass the junction with the Source Lake Trail #1013.2, signed “Source Lake Overlook Trail,” which served as the primary route to Snow Lake before washouts prompted the building of a more direct route over the cliffs. Keep right on the Snow Lake Trail.

Switchback steeply up the ridge, crossing into the Alpine Lakes Wilderness at 2.4 miles shortly before you crest the top of the ridge and reach the other end of the Source Lake Trail. Pause at the clearing at the top to catch your breath before descending to Snow Lake. It’s a short 0.4-mile drop to the water, with lovely views of the lake sprawling out before you.

From the lakeshore, the first junction you reach leads to the water and the crumbling foundations of a cabin built in 1930 (see History for Hike 29). Explore the ruins and take in Snow Lake before pressing farther down the trail, circling the lake to reach a trail junction at 3.3 miles. Here, the Rock Creek Trail #1013.1 (Hike 14) to the right leads down to the Middle Fork Snoqualmie Valley, and the High Lakes Trail #1012 begins to the left. Keep left, following the arrow toward Gem Lake, and begin your ascent.

And a climb it is; soon leave Snow Lake behind for narrow, rocky trail that goes up, up, up. Push through talus fields and pass moss-covered trees to eventually reach Gem Lake at 4.6 miles. Once you see the water, note the dozens of boot paths spiderwebbing up into the slopes around the lake and down to the shore. Some lead to campsites, others to quiet perches with views of Gem or Snow or both. Find a spot to rest, and when you’re ready, push onward, following the widest trail around the north side of the lake and passing the boot path that climbs the flanks of Wright Mountain to its summit (the route is not considered technical and the views from the top are excellent).

Gem Lake and Wright Mountain in the heart of summer

Beyond Gem Lake the trail climbs up a small ridge to a saddle before steeply dropping into Wildcat Basin, switchbacking first through talus and then forest all the way down to a creek. Work your way up the basin, gaining elevation and passing a number of ponds to a campsite and trail junction at 6.5 miles. The short path to the left leads down to Lower Wildcat Lake and another campsite. To the right the trail continues another 0.4 mile to Upper Wildcat Lake.

While the poorly maintained trail to it requires a bit more climbing, the upper lake is the more appealing of the two and worth the effort. Cross the logjam at the outlet to find campsites. Brushy boot paths lead around the lake, drawing you closer to its enchanting island. Above the lake, Caroline Peak rises dramatically to the southwest. This truly is an alpine paradise.

If a climb to the top of Wright Mountain near Gem Lake doesn’t appeal, a side trip down to Rock Creek Falls (Hike 14) from Snow Lake is an easy addition. If time allows, add a swing out to Source Lake Overlook (Hike 29) to your journey as well.

Gem Lake is fairly small, less than fifteen acres. Perhaps its small size inspired The Mountaineers to give it a name suggesting a jewel set into the landscape. Wright Mountain’s name is also a legacy of The Mountaineers, who named it in honor of George E. Wright, an early member who died in 1923.

DISTANCE: 3.0 miles

ELEVATION GAIN: 3100 feet

HIGH POINT: 6278 feet

DIFFICULTY: Hard

HIKING TIME: 4 to 6 hours

BEST SEASON: Early summer to early fall

TRAIL TRAFFIC: Moderate foot traffic

PERMIT: Northwest Forest Pass

MAPS: USGS Snoqualmie Pass; Green Trails Snoqualmie Pass No. 207

TRAILHEAD GPS: 47.4452°N, 121.4234°W

GETTING THERE: Take I-90 to Snoqualmie Pass. Eastbound take Exit 52 and turn left onto Alpental Road for about 2 miles to a large gravel parking lot. Westbound take Exit 53, turning left under the freeway and soon reaching a T intersection. Turn right onto State Route 906, following the sign pointing toward Alpental. Continue 2.7 miles through the ski area to the parking area. The trail begins along an unsigned dirt road a few dozen feet south of the Snow Lake Trailhead. Privy available.

Climb to unmatched views from a perch high on the Cascade Crest, the tallest tip in the Snoqualmie Pass area. While this unimproved trail has all the challenges associated with a rough boot path, it leads to commanding views more than worth the brushy, sweaty climb.

Near the summit of Snoqualmie Mountain with Keechelus Lake and Guye Peak in the background

Start at an unsigned dirt road a few feet south of the Snow Lake Trailhead. At 0.1 mile, keep an eye out for a small side trail branching off to the right—if you reach a shed, you’ve gone too far. Buckle up for a rough ride on this first section of narrow trail. The route takes advantage of rocky stream beds that are sometimes brimming with bubbling water. Cut straight up the mountainside, pushing aside encroaching slide alder as you climb. Be mindful of loose rock as you navigate up talus slopes.

After a long 0.6-mile climb, reach a boulderstrewn saddle and a signed junction marking the routes to Snoqualmie Mountain to the left and Guye Peak to the right. Veer left over the rocks for Snoqualmie Mountain, and soon reach a stream crossing complete with a lovely waterfall. Push onward and ever upward, catching occasional pocket views of the ski slopes of Alpental and Snoqualmie Pass. Watch as the trail quickly trades thick underbrush for mountain forest before shedding the woods for alpine meadows spotted with wildflowers and a few trees. After the trail opens up, it begins a series of tight switchbacks up an exposed ridge, with views getting more impressive with every step.

It’s a thigh-burning workout, but Snoqualmie Mountain dishes out a phenomenal panorama. On a clear day, Mount Rainier dominates the skyline. Looking clockwise from Rainer’s snowy slopes, follow the long, craggy ridgeline that begins with Denny Mountain, becomes the Tooth, then extends to Hemlock Peak and Bryant Peak before culminating above Snow Lake (Hike 29) in a massive mountain that sprouts Chair Peak, Kaleetan Peak, and Mount Roosevelt. Swing past Snow Lake and check out the seemingly gentle ridges of the Middle Fork Snoqualmie Valley; on the best of days catch a glimpse of Glacier Peak in the distance. Nearby Lundin Peak and distinctive Red Mountain (Hike 33) sit almost directly opposite Rainier, along with Mount Thompson, Kendall Peak, and Alta Mountain (Hike 42). Cave Ridge and Guye Peak (Hike 32) sit to the southeast with Keechelus Lake beyond.

A trip to the top of Snoqualmie Mountain is not for everyone, but for those who persevere, there is plenty of room at the top to find a place to settle down, argue about the names of peaks, and enjoy a hard-earned lunch.

A side trip out to Guye Peak (Hike 32) is available for those who still have the energy for more climbing. It’s about 0.5 mile from the trail junction to the top, but it is somewhat of a technical scramble, so be sure your legs are up to the challenge before you venture out onto the rocks.

Snoqualmie Mountain rises quietly above the rest of the Snoqualmie Pass peaks, clocking in at 6278 feet. Despite being the highest peak in the pass, its broad, rounded slopes do not cut a dramatic profile. Snoqualmie Mountain and the surrounding area were already abuzz with activity by the time a USGS survey led by Albert H. Sylvester made the first recorded summit climb in 1898. While miners’ boots originally pounded out most of the trails in the area, it was The Mountaineers who in the 1920s put Snoqualmie Mountain on their list of peaks to bag and kept the trail from being lost.

DISTANCE: 2.5 miles

ELEVATION GAIN: 2000 feet

HIGH POINT: 5168 feet

DIFFICULTY: Hard

HIKING TIME: 3 to 5 hours

BEST SEASON: Late spring to early fall

TRAIL TRAFFIC: Light foot traffic

PERMIT: Northwest Forest Pass

MAPS: USGS Snoqualmie Pass; Green Trails Snoqualmie Pass No. 207

TRAILHEAD GPS: 47.4452°N, 121.4234°W

GETTING THERE: Take I-90 to Snoqualmie Pass. Eastbound take Exit 52 and turn left onto Alpental Road for about 2 miles to a large gravel parking lot. Westbound take Exit 53, turning left under the freeway and soon reaching a T intersection. Turn right onto State Route 906, following the sign pointing toward Alpental. Continue 2.7 miles through the ski area to the parking area. The trail begins along an unsigned dirt road a few dozen feet south of the Snow Lake Trailhead. Privy available.

It’s something of an exaggeration to call the route to the top of Guye Peak a trail, as it is more a series of scrambles over boulders and fallen trees connected by short boot-pounded paths through narrow bands of vegetation. The route aggressively attacks the elevation, conveying you up the slope with only an occasional begrudging switchback or two. The short trail distance and close proximity to I-90 mean easy access, making this route popular with both hikers and mountaineers year-round, but don’t be fooled into thinking it is easy. Use caution near the top—quite a number of people have died on Guye Peak since the 1960s.

From an unsigned dirt road a few feet south of the Snow Lake Trailhead, begin heading up. Watch for a side trail branching off to the right at 0.1 mile; if you climb up to a shed, turn around and retrace your steps to find the trail. Battle up the mountainside, over streams, through brush, and across loose rock to the top of a talus field and a signed junction at 0.6 mile with the Snoqualmie Mountain Trail (Hike 31) to the left. Turn right for Guye Peak.

Here the trail levels out, and an unmarked spur trail leads off to the right (south), soon passing a seasonal pond. If you start to descend before finding the spur trail, you’ve passed the turnoff. Retrace your steps to find the path and begin the final push to the top. Leave the trees for exposed rock, navigating under granite overhangs and scrambling past big drop-offs to reach the windswept summit. Use caution in this section, as slick conditions can easily lead to a tumble or worse.

The Guye Peak Trail is never short on impressive views of the Snoqualmie Pass peaks.

Though the route up Guye Peak is short and brutal, the top pays dividends in spectacular views. Survey the ski slopes of Alpental and Snoqualmie Pass, as well as the whole of Commonwealth Basin. To the west lies Denny Mountain, supporting the slopes of Alpental and beginning a north-running ridgeline that includes the Tooth, Bryant Peak, and Chair Peak. Snoqualmie Mountain (Hike 31) dominates the view to the north, while Red Mountain (Hike 33) steals the show as you look east to take in Kendall Peak (Hike 34).

A blistering climb to the top of Snoqualmie Mountain (Hike 31) is possible for those with a thirst for greater heights. Note that access to Cave Ridge can be found along this hike, but the Forest Service has asked that hikers avoid the area because parts of Cave Ridge are privately owned, and degrading trail conditions have created a hazard for hikers.

Largely exposed and bare, Guye Peak has a distinct look about it. Perhaps as a result of that look, it’s had several names over the years. It was tentatively named Slate Mountain for a time, and the alternatives Mount Logan and Guye’s Mountain were also considered. The Guye in question is Francis M. Guye, who, along with David Denny, staked out mining claims on both Guye Peak and Snoqualmie Mountain, all within what was then known as the Summit Mining District. Many of the rough paths that crisscross the mountains above Alpental have their origins in the mining activities of the late 1800s.

DISTANCE: 8.8 miles

ELEVATION GAIN: 2400 feet

HIGH POINT: 5400 feet

DIFFICULTY: Hard

HIKING TIME: 6 to 8 hours

BEST SEASON: Late spring to early fall

TRAIL TRAFFIC: Moderate foot traffic

PERMIT: Northwest Forest Pass

MAPS: USGS Snoqualmie Pass; Green Trails Snoqualmie Pass No. 207

TRAILHEAD GPS: 47.42787°N, 121.4134°W

GETTING THERE: Take I-90 to Snoqualmie Pass. Eastbound take Exit 52 and turn left under the freeway toward Alpental, and in a few thousand feet turn right onto a small spur road marked “Pacific Crest Trail.” Westbound take Exit 53, turning left under the freeway, soon reaching a T intersection. Turn right onto State Route 906, following the sign pointing toward Alpental. Continue 0.7 mile through the ski area to a small spur road marked “Pacific Crest Trail.” Follow the spur road to two large parking areas. The first is reserved for stock; hikers should continue to the farther parking lot and trailhead. Privy available.

This route leads out through a broad creek basin and up to a mountain pass with big views. Along the way enjoy chattering creeks, a lonely tarn, and, in the fall, mountainsides afire with oranges, reds, and yellows.

From the trailhead, begin down the Pacific Crest Trail #2000 (PCT) and in a short distance pass an unmarked but well-trodden trail branching off to your left. This is the old Cascade Crest Trail (CCT) route that is no longer maintained but is clearly still well loved. (If you’re feeling adventurous, that trail also connects with the Commonwealth Basin Trail #1033, but it is a little more difficult to navigate.) Instead, continue straight ahead, sticking with the PCT.

Soon enter a mixed forest of fir and hemlock as the trail slowly climbs, crossing into the Alpine Lakes Wilderness at the 0.4-mile mark. Wide and well maintained, this section of trail breezes by. Skip over streams and cross long swaths of talus and meadowlands while finding increasingly better views of Commonwealth Basin and Snoqualmie Pass. Enjoy the wildflowers that dazzle during spring and summer as the trail steepens on long switchbacks and becomes increasingly rocky.

After 2.4 miles reach a connector trail on your left that leads a few hundred feet down to the Commonwealth Basin Trail. Veer down into the basin and follow the trail deeper into the valley. Enjoy the sounds of rushing water and occasional pocket views of the valley walls before reaching the end of the basin and beginning a sharp climb up the base of Red Mountain toward Red Pass. After a number of steep switchbacks, attain a level shoulder at 3.9 miles, where short spur trails lead down to Red Pond and up to the crown of Red Mountain. Decide here whether to brave the difficult scramble up Red Mountain, or take a quick jaunt down to Red Pond before pushing up to Red Pass.

Switchback upward, pressing toward the pass to find ever-better views of Commonwealth Basin stretching out below. Reach the pass at the 4.4-mile mark and note the junction signed “trail abandoned.” This is the old PCT route leading down to the Middle Fork Snoqualmie and Goldmyer Hot Springs (Hike 15) that predates the Kendall Katwalk. While a few brave souls still try to follow this route, it’s a long, unpleasant bushwhack best left abandoned.

Looking down from the trail at Red Pond’s shallow waters and a snow-dusted Commonwealth Valley

The climb to the pass is well worth the effort: the views here are spectacular. The mountain simply drops away, providing you a perch at the top of a massive natural amphitheater. The horn of Mount Thompson steals the show, a fitting counterpoint to Mount Rainier to the south. Commonwealth Basin spreads out to Alpental in the distance. Red Mountain suddenly looks much craggier and more intimidating from this side. From here, Snoqualmie Mountain (Hike 31) and Guye Peak (Hike 32) seem less imposing than they usually do, and the rocky top of Lundin Peak is just ahead on the trail.

Lundin East Peak is easily accessible from Red Pass. Simply follow the trail that continues along the ridge from the pass, ignoring signs that say the trail is abandoned. Take the left fork and head upward, sticking to the rough trail to the top. The views don’t change much with the extra effort of pushing past the usual stopping point of Red Pass, but it’s a cozy little spot to settle down and refuel.

The Commonwealth Basin Trail has its origins in the mining claims common in this area. The trail was originally built by prospectors around 1890 to access claims within the valley. In 1928 Fred Cleator, who was put in charge of the US Forest Service region encompassing Oregon and Washington, immediately pieced together a contiguous trail through his region that would eventually become the CCT. The old Commonwealth Basin route served as part of the CCT until the early 1960s, when the preferred CCT route shifted over to the Snow Lake–Rock Creek approach (Hikes 29 and 14).

DISTANCE: 12.2 miles to Kendall Katwalk

ELEVATION GAIN: 3000 feet

HIGH POINT: 5784 feet

DIFFICULTY: Hard

HIKING TIME: 6 to 8 hours

BEST SEASON: Early summer to early fall

TRAIL TRAFFIC: Heavy foot traffic

PERMIT: Northwest Forest Pass

MAPS: USGS Snoqualmie Pass; Green Trails Snoqualmie Pass No. 207

TRAILHEAD GPS: 47.42787°N, 121.4134°W

GETTING THERE: Take I-90 to Snoqualmie Pass. Eastbound take Exit 52 and turn left under the freeway toward Alpental. In a few thousand feet turn right onto a small spur road marked “Pacific Crest Trail.” Westbound take Exit 53, turning left under the freeway, soon reaching a T intersection. Turn right onto State Route 906, following the sign pointing toward Alpental. Continue 0.7 mile through the ski area to a small spur road marked “Pacific Crest Trail”. Follow the spur road to two large parking areas. The first is reserved for stock; hikers should continue to the farther parking lot and the trailhead. Privy available.

Something about the obvious intrusion of humankind onto a fairy-tale-like landscape has attracted hikers and backpackers for decades. “Kendall Katwalk” can summon thoughts of a vertigo-inducing shimmy across an exposed cliff face hundreds of feet in the air. In reality, this dynamite-blasted trail is not nearly so harrowing. It’s a fun destination along this popular section of the Pacific Crest Trail, though the views from the Katwalk cannot compare to the stunning panorama from the top of Kendall Peak.

From the trailhead, begin by following the Pacific Crest Trail #2000 (PCT) into a forest of mixed fir and hemlock, soon passing an unmarked but obvious trail on the left that follows long-abandoned roadbed into young underbrush. This is the unmaintained but still loved Cascade Crest Trail (CCT) that can be used as an alternate approach to Red Pass (Hike 33). For now, press onward, watching as the trees quickly thin and give way to dense patches of huckleberry and salmonberry. At about 0.4 mile, cross into the Alpine Lakes Wilderness and follow long, lazy switchbacks up a mild grade, with the occasional rock and root to navigate around.

Eventually the trail steepens and begins a long traverse through talus fields and subalpine meadows, with accompanying open views of Snoqualmie Pass and the surrounding landscape. During spring and summer, the meadows fill with wildflowers, adding some much-needed color to an increasingly rocky trail. Pass the junction with the Commonwealth Basin Connector Trail (Hike 33) at 2.4 miles, continuing to navigate stretches of talus and ever-changing views of the basin below.

Drilled and dynamited in the 1970s, the Kendall Katwalk was carved directly into the mountainside.

At about 5.0 miles, reach the shoulders of Kendall Peak, where the trail quickly switchbacks; just beyond, at 5.3 miles, look for an unmarked boot path straight up the mountainside to the summit. Though it’s a bit of a scramble beset with loose rock, the path is fairly well defined and easy to follow. Quickly gain the narrow ridgeline and cautiously follow it to the top, keeping one eye on the rubble at the bottom of the cliffs hundreds of feet below.

The view is tremendous. The weather-worn spires and crags of the Alpine Lakes Wilderness fill the horizon like a sea of crumbling sand castles. Red Mountain catches the eye to the north, with Mount Thompson just beyond. Mount Rainier rises to the south, a dramatic backdrop for Mount Catherine and the Snoqualmie ski slopes. Guye Peak (Hike 32) is below, stoically keeping watch over Snoqualmie Pass. To the southeast are the shimmering waters of Keechelus Lake. Find a comfortable rock to sit down on—it’s going to take a while to drink all this in. Before you head back down, look for the cast-iron tube containing a summit registry maintained by The Mountaineers, and add your name.

Scramble back to the PCT and continue another 0.8 mile to the Katwalk, which is farther down the trail than anyone expects. The Katwalk looks very much like it was blasted from the side of a mountain, and the rubble below is ample proof. Enjoy the view from this artificial balcony before packing up and heading back to the trailhead.

The entire PCT route between Snoqualmie Pass and Stevens Pass, of which this hike is the first leg, encompasses a myriad of backpacking adventures outlined later in this book (Hike 100).

The PCT took the better part of sixty years under construction. In the 1930s, a coalition of hiking and youth groups sketched out an approximate route for a Pacific coast counterpart to the Appalachian Trail. From the 1930s until 1968, the route was blazed and explored, receiving federal recognition under the 1968 National Trail System Act. Then various trail organizations, land management agencies, and an army of volunteers worked to link regional trails from Mexico to Canada to form the PCT. By the early 1970s, one of those regional trails—the CCT—was rerouted to meet the PCT’s trail standards.

In 1938 the earliest CCT route went up Commonwealth Basin (Hike 33) and over Red Pass down to the Middle Fork Snoqualmie River Valley. By the 1960s, the preferred CCT route followed Rock Creek (Hike 14) down to the Middle Fork Snoqualmie and eventually up over Dutch Miller Gap (Hike 93). Both of those routes did not accommodate pack animals and, as a result, did not fully meet the trail standards set out by the 1968 act.

By 1971, the Forest Service was trying to locate a better route and, after much consternation and a lot of pushback, decided on the Kendall Katwalk approach. Contractor Elmo Warren of Sagle, Idaho, won the bid to build it and quickly addressed a number of difficulties presented by the Forest Service. The problem of marking the route on the granite cliffs was solved by filling beer bottles with red paint and dropping them from a helicopter. The issue of how the trail would be carved out of the rock was solved by hauling eighty-pound gas-driven Pionjar drills to slowly chip away at whatever rock could not be blasted away by dynamite. Most of the initial clearing was done in 1976, and it was completed in 1977. The new section of the PCT that included Kendall Katwalk officially opened in 1979.