11 |

SINGAPORE: A GLOBAL TRADER |

An often-used assessment of present-day Singapore is that the People’s Action Party government transformed Singapore from a “colonial backwater” into a modern, prosperous global city. While it is true that the PAP transformed the city, it was certainly not a backwater. British Malaya was of great significance to global economic and political issues during the years between the two world wars. Malaya and Singapore were deeply involved in three of the most important issues that faced the world’s two largest powers – Britain and the United States. Questions of international debt, the balance of power and the price of key raw materials for industry invariably included British Malaya and Singapore. The infrastructure and services that these territories developed to service straits exports could not be matched or replicated anywhere else in the area.

By the turn of the twentieth century, Singapore was the most important port in Southeast Asia and the seventh largest port in the world. As the production of raw materials in the area around it grew, Singapore had the geographical advantage as well as a well-developed infrastructure to facilitate the expansion of trade and commerce. Financial and commercial services were required to make growth possible, and the island was able to provide them. Even though large amounts of capital were raised from outside the area, the need for credit and banking facilities in Malaya boosted Singapore’s financial community significantly. The money to expand production, buy machinery and finance trade brought increased profits to established banks and drew new banks from the United States, France, the Netherlands, and the Middle East. The need to insure cargoes to and from the area resulted in the setting up of an insurance market as well. These developments rapidly established Singapore as an important financial center as well as a thriving port city. It made its living by offering services to trade.

Many companies that owned rubber estates and tin mines were in London and did not have the personnel or expertise necessary to facilitate their production. As such, many well-established companies in Singapore provided these services. Guthrie, Sime Darby, Boustead and others acted as agents in purchasing supplies and equipment, providing labor and management services and facilitating the shipment of raw materials to the rest of the world. These agencies also acted as distributors of imported products to meet the growing demand for Western manufactured goods.

Although most Singaporeans were unaffected by the international conflict that took place between 1914 and 1918, World War I did leave its imprint on the country. Economically, Singapore benefited from the rise in demand and prices of raw materials from Malaya and the archipelago. Property and businesses owned by Germans were seized and turned over to British subjects. Regular British armed forces were transferred to the war in Europe, and defense of the island was the responsibility of British Indian troops.

Muslim troops serving in the British Indian army had mixed loyalties during the war. Turkey was allied with Germany, and the idea of fighting fellow Muslims upset the troops, especially since the sultan of Turkey was the caliph (leader) of the Islamic kingdom. Many of the troops also believed a story spread by Turkish agents that the Kaiser had converted to Islam. At the mosque near their barracks, the imam (religious leader) inflamed the Singapore troops with anti-British propaganda and said that it was a sin to serve enemies of the Turks.

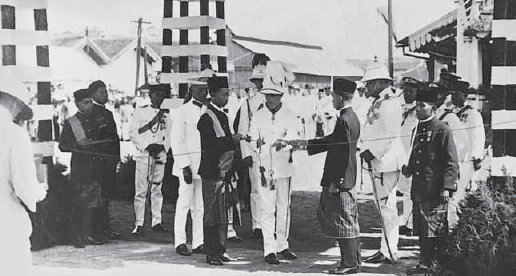

On February 15, 1915, Muslim troops mutinied, killing many of their officers and then going on a rampage and murdering British civilians. Initially, people on the island did not notice the commotion because it was Chinese New Year, and the gunfire was mistaken for firecrackers, but they soon recognized the threat.

The sultan of Johor and his army joined with men from ships in the harbor and European and Japanese civilians. When the mutiny was put down with the assistance of regular troops from Burma and other Allied powers, over forty people had been killed. Forty-seven soldiers were subsequently court-martialed and executed in public, one of the darker chapters in the history of the British Indian army.

Execution of mutinous Indian soldiers in Singapore in 1915.

While most of these agencies were owned by Europeans, many Chinese prospered along with them and in spite of them. These Asian entrepreneurs provided the link between the small producers of tin, rubber and other Straits produce and the export agencies. Chinese businessmen also distributed the imported goods at the consumer level, and their financial and commercial institutions grew alongside the European concerns. Through contacts with other immigrant Chinese, the commerce of small ports and of less important products, such as copra and spices, was dominated by Chinese merchants mainly based in Singapore. An indication of Singapore’s growth as a trading center is that in 1895 its total trade amounted to about $250 million; by 1923, it had increased to almost a billion dollars.

By the early twentieth century, a three-way economic relationship had developed among the United States, British Malaya and Britain. America was consuming the majority of raw materials coming from the Straits but selling very little to Malaya. The beneficiaries of this trade imbalance were shareholders of British plantations and mines as well as British banks and insurance and shipping companies. American money flowed through the Straits to London to such an extent that during the period between 1918 and 1942, British Malaya became known as Britain’s “dollar arsenal” and was arguably Britain’s most profitable colonial venture, not just because of the resources from the area but also because of the income from trade services.

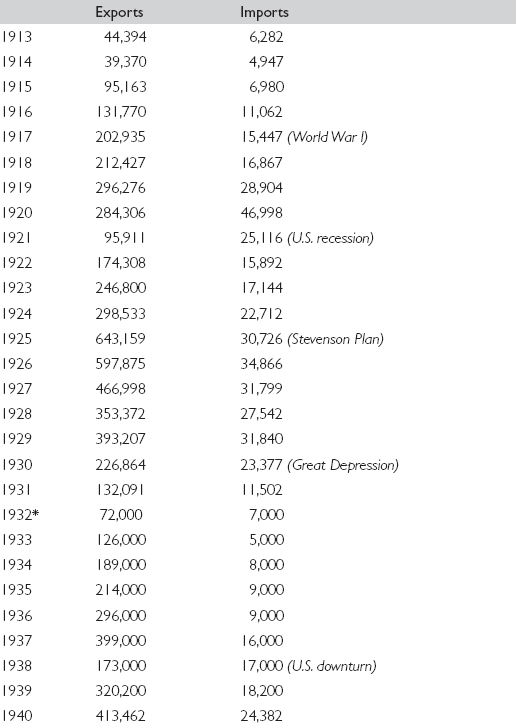

Table 11.1: Straits Settlements Trade with the United States, 1913–1940 (in millions of £)

Compiled from Sodhy, Pamela, Passage of Empire, p. 127; Statistical Abstract of the United States 1941, p. 59; and Straits Settlements Annual Reports. ( 1932–1939 rounded off.)

1932–1939 rounded off.)

The rubber plantations that developed in British Malaya in the early twentieth century became directly tied to the fortunes of the American rubber and automobile industry. The ties between the two were so close that it was said: “when America sneezed, Malaya caught a cold.”

The United States had emerged from World War I as the world’s creditor nation as well as enjoying a trade surplus with the world. France and Britain, its major debtors, were trying to get their war-shattered economies back on their feet. These war-time allies felt that since the debts had resulted from a common cause, the United States should be flexible while the nations recovered from the war, but the United States insisted that the war debts be serviced and paid. It also began to raise the tariffs on imports to the United States. This presented the debtors with a dilemma. If they could not export to the United States, where would they find the foreign exchange to service the debts?

Britain owed the United States $4.7 billion. The need to find foreign exchange to pay this debt was further complicated by Britain’s chronic trade deficit. For example, between 1901 and 1913, Britain ran an average trade deficit of £150,000,000 a year. Britain may have been the first country to industrialize, but by the turn of twentieth century, British free trade and new competitors, such as the United States, Germany and Japan, had seriously reduced Britain’s share of the global market for manufactured goods. Britain had compensated for the goods deficits with trade in financial and commercial services provided in London and with the income from its foreign investments. Until World War I, this had easily compensated for its trade deficit. In fact, British banks, insurers, commodity traders and shipping companies had actually created a surplus in Britain’s overall balance of payments.

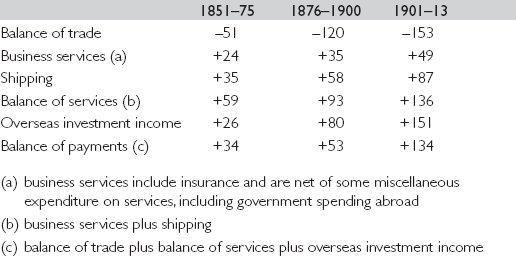

Table 11.2: Invisible Trade and Balance of Payments: Britain, 1851–1913 (annual average in millions of £)

Cain, P.J. and A.G. Hopkins, British Imperialism, Innovation and Expansion, 1688–1914, p. 170

Table 11.2 illustrates that the services to trade and foreign investment were essential to Britain’s ability to balance its international payments. In the eyes of British policy makers, a strong pound sterling that drew funds from abroad was key to this balancing act. Prior to the war, Singapore had become an important part of Britain’s trade and services sectors. As Singapore’s trade grew, so did British shipping. A majority of the shipping in and out of Singapore was carried on British ships. Singapore firms had important connections with London for financing and insuring this trade.

Britain’s war debts as an outflow of foreign exchange to the United States posed a great challenge to Britain’s international economic standing and the pound sterling. British Malaya helped meet the challenge. Malaya was an important source of the US dollar foreign exchange that flowed from Singapore to London. Between 1922 and 1928, British Malaya’s trade surplus with the United States brought over US$1 billion into the imperial coffers. Even during the Great Depression, Malaya’s surplus average was over US$100 million a year.

The relationship between the United States, Britain and British Malaya was brought to the forefront by the American recession of 1920–1922. The slowdown in its economy hit the price of rubber in Singapore dramatically. It fell from US$1.05 a pound in 1920 to US$0.46 a pound in 1921 and eventually went as low as US$0.16 a pound in 1922. This created an economic crisis not only in British Malaya, but in London as well. In Malaya, many plantations faced bankruptcy. Migrant labor was laid off. The volume of trade dropped, and many small rubber buying and shipping companies went out of business. In London, the dividends of 30,000 British investors vanished. The shipping/finance infrastructure that had serviced the booming rubber trade was hit hard. Besides this, the influx of needed American exchange went down over US$150,000,000.

In both London and Singapore, there was a growing sense of urgency to do something about the price of rubber. Winston Churchill, then the colonial secretary, reflected the view in London when he said in 1921: “The whole industry in which £100,000,000 of British capital had been sunk was falling into ruin ... It was impossible for the colonial office to witness the financial ruin of the rubber producing colonies owing to the continual sale of their products below the cost of production ... [Also] one of our principal means of paying our debt to the United States is in the provision of rubber.”

In the view of London and in Singapore, the answer to the problem was to restrict the supply of rubber on the markets to drive up its price. To do this, the colonial office, in concert with the Rubber Growers Association, came up with what became known as the Stevenson Plan.

Originally the plan was to draw all the rubber-producing areas of the world into a quota system to restrict the supply of rubber, not unlike OPEC today. Other rubber producers, such as the Dutch East Indies, French Indochina and Siam, refused to go along with the British. The British proceeded alone, based on the fact that British territories produced over two-thirds of the world’s rubber. In the short run, the plan was successful. It drove up rubber prices and restored the profitability of the rubber plantation industry. By 1925, the price of rubber had risen to US$1.25 a pound, a far cry from US$0.16, and a level that reaped great profits for the rubber plantation industry.

The manipulation of rubber prices by London touched off a vocal and angry response from American captains of industry. Besides its key connection with the automobile industry, the rubber industry alone was responsible for hundreds of thousands of American jobs. American companies tried alternate sources of rubber, such as plantations in South America and growing the trees in the United States, but these new sources were poor alternatives to Malaya.

In the long run, however, the Stevenson Plan was detrimental to the Malayan rubber plantation industry. The high prices encouraged other countries to produce more, especially in the Dutch East Indies. High prices also encouraged rubber goods manufacturers to reclaim and recycle rubber products. The impact on Malaya was significant in that by 1927, it was only producing about half the world’s natural rubber. The increased non-British production put downward pressure on prices, and by 1927, the very people who had pushed for the restrictions began to demand an end to them. Interestingly, Singapore itself benefited significantly from the heavy flow of trade through its harbor that was created by the increase in production in the East Indies.

The scheme was scrapped in 1928. The true impact of the Stevenson Plan was that it highlighted the importance of trade goods emanating from British Malaya.

Singapore’s services were not confined to Malaya. Trade from Borneo and the Dutch East Indies also flowed through Singapore. Although the Dutch tried to prevent it, much of Indonesia’s raw materials passed through Singapore because of its superior port and trading facilities. An example was its assumption of a role it plays to this very day as the most important oil bunkering facility in Asia. The discovery of oil in Borneo, Sumatra, and East Java and the increased use of petroleum products for fuel created the need for a central facility for its storage and ready availability. Singapore became the clearing house for kerosene and, later, other oil products. The first plant was set up on Pulau Bukom in 1905 by the forerunners of Shell, and it remains one of Shell’s most important facilities 100 years later.

Singapore’s economic lifeblood depended not only on its geographical position but also on its ability to offer a good infrastructure for trade. To this end, significant progress was made toward improving its capacity to provide smooth flow of trade. A key concern at the turn of the century was the island’s ability to expand and improve its harbor and dock facilities to meet the increase in trade. The docks of Singapore were all privately owned, the majority by the New Harbor Dock Company. This company was owned by private investors who were not willing to spend millions on expansion and improvements. In 1905, Governor Sir John Anderson decided that the government would buy out the company and take over the docks and harbor. In 1913, the administration of the port was turned over to a newly formed government agency – the Singapore Harbor Board, now the Port Authority of Singapore. A large expansion of the port culminated with the opening of the Empire Dock in 1917, the largest dry dock in Southeast Asia. Without government intervention, Singapore’s port would probably have choked on its own success.

The causeway that linked the island of Singapore with the peninsula was opened to rail traffic in 1923. This meant Singapore was connected directly to the rail and highway systems of Malaya. Electric tram lines were built, new roads laid and reservoirs dug to service the growing port and city.

In 1937, the Kallang air and sea plane terminal was opened. This marked the beginning of a new role for Singapore as a hub for air travel. As early as the 1930s, KLM Royal Dutch Airlines, Pan American Airlines, Qantas and Imperial Air Ways (later British Air) used Singapore as their central destination in Southeast Asia. Although the airstrip crossed roads and barriers had to be dropped when airplanes landed, it was the beginning of Singapore’s role as an international center for air travel.

The causeway linking Singapore and Malaysia was opened in 1923 by Governor Laurence Guillemard of Singapore (cutting ribbon) and Sultan Ibrahim of Johor.

Singapore’s importance as a port grew dramatically in the decades before World War II, as did its strategic and military importance. Since its victory over Russia in 1904 and its subsequent alliance with Britain, Japan’s naval power and influence in Asia had increased considerably. Prior to and during World War I, Britain was not concerned about Japan’s growing power as the strength of its ally in the Pacific freed Britain to meet the German challenge. However, by the time the war was over, Japan had moved from the position of convenient ally to that of a military and commercial threat to British interests in Asia.

Victory in World War I was painfully expensive for the British. Many of the best and brightest of a generation had died in French fields and trenches. Britain also spent a great deal of money fighting the war, draining its reserves and becoming indebted to Americans for billions of dollars. When the war was over, Britain had neither the will nor the financial resources to reestablish its traditional naval role in Asia.

Originally, the problem of Japan’s rising power was thought to have been solved at the 1921 Washington Conference, at which Britain, the United States, and Japan agreed on a ratio of 5:5:3, respectively, in capital ships, and Britain and the United States agreed not to build any bases within striking distance of Japan. The treaty was easy to circumvent, and it was soon evident that Japan was building a navy that could dominate the Pacific. Britain was faced with a dilemma. It could not afford to build a second fleet to meet Japan’s challenge in the Pacific, nor could it move the fleet that defended its home waters to the Pacific. The solution was to build an Asian base capable of accommodating the home fleet in an emergency.

Singapore was chosen as the site for the new base. At the same time, the United States built up Pearl Harbor in Hawaii as a deterrent to Japanese naval power. The decision to build the base in Singapore was announced in 1923, but it took over fifteen years to complete because it became a “political football” as governments changed in Britain. Its building took on new urgency when Japanese expansionist intentions became evident with their invasion of Manchuria in 1932. By the time the base was completed in 1939, it had cost the British and Imperial taxpayers close to $500 million. It was an impressive facility, boasting the largest dry dock in the world. Sir Winston Churchill called it the Gibraltar of the East, “Fortress Singapore.”

The problem was that there was no fleet to occupy the base, and when the need came for one, Britain’s fleet was too busy fighting Germany. Regardless of Britain’s inability to use the base to its fullest potential, Singapore took on new significance as the British military headquarters in the Far East. The jobs created by the building of the facilities and by the increased military presence were a boon to Singapore’s economy.

Singapore’s growth in economic and strategic importance between the two world wars was impressive. The problem was that its strengths were also its weaknesses. The island’s prosperity was tied to trade and its ability to facilitate the production and sale of the area’s raw materials. As a result, the Great Depression hit Singapore hard.

As factories in the West closed, the demand for tin and rubber fell and with it the income Singapore derived from them. Economies collapsed and countries scrambled to put up trade barriers to protect their markets, while Singapore suffered from the resulting drop in world trade. For many people in territories near Singapore, falling back on the land to survive was always an alternative. Urban Chinese who fled the cities in Malaya and the rural Malays could survive, but for most people in Singapore, this was not an option on an island that was 42 by 21 km (26 by 13 miles) and highly urbanized. There was massive unemployment and economic hardship.

The Great Depression not only marked economic bad times but also a turning point in the nature of the Singapore community. Economic fortunes improved with time, but the social ramifications were dramatic and long lasting.

A fundamental change in the nature of the Chinese community was caused by changes in British immigration policy. Already facing high unemployment in Singapore, the government feared an influx of immigrants fleeing even worse conditions in China. It offered to pay the passage of anyone who wanted to return to China, and for the first time, there were actually more people leaving the colony than entering it. The British also established the first immigration restrictions on Chinese entering British Malaya. A quota system reduced to a trickle the number of Chinese men who were allowed to enter Singapore. In 1930, 158,000 Chinese males arrived in Singapore; by 1933, this had been reduced to 14,000. Significant to this quota system was that the government did not restrict the entry of women and children. Families in China sent thousands of what they saw as unneeded daughters away from the hardships of war, depression, and famine. In 1921, there were more than two males to every female in Singapore; by the end of the 1940s, the ratio was almost one to one.

It is difficult to overstate the ramifications of this female immigration. The women who came to Singapore in the 1930s and 1940s are sometimes called “the mothers of Singapore.” Prior to this huge influx of women, the majority of the Chinese community consisted of male migrant workers. These males had no ties to the community, provided cheap labor, and contributed to many of the social ills of Singapore, such as drug taking, prostitution, and gambling. As the male/female ratio began to balance out in the 1930s and 1940s, more and more Chinese began to accept Singapore as their home. In 1931, 38 percent of the Chinese community in Singapore was locally born; by 1947, this rose to about two-thirds. The majority of Chinese citizens in Singapore today only date their ties to the country from this time, a time when Singapore ceased being a migrant society and became a truly immigrant one.

Prior to the 1930s and 1940s, much of government policy in Singapore had been based on a view that, because most Chinese were transient, it had little obligation for their welfare. The transformation of Singapore’s population made those government views obsolete. Take, for example, the problem of opium. Worldwide pressure had been building against Britain’s legal drug dealing, but colonial administrators were less than eager to give up this important source of government revenue. Their initial response was to take control of the market to end the crime and the excesses that existed. All addicts were required to register, but as long as the government could portray the opium problem as primarily among the coolies, there was not sufficient public pressure to end its sale and consumption. Some colonials even argued that, given the drudgery of a coolie’s life, opium was not an altogether bad form of relief and relaxation.

As the nature of the population changed, the government’s position was no longer defensible. In 1934, no new addicts were allowed to register, and the authorities committed to ending government-sanctioned drug use. Between 1920 and 1935, the amount of opium imported into Singapore was cut by over 60 percent.

Up until this time, Singapore had a reputation as “sin city.” It was a port with a predominantly male population and was infamous for its vices. As increasing numbers began to sink roots and raise families, the Asian population began to demand that the British address the problems of law and order in the various communities. The police force expanded to some 4,000 men, and more Chinese were included on the force. Police training programs were upgraded, numerous new police stations were set up and crime rates went down.

The stabilized Chinese population presented challenges that the authorities had previously downplayed or ignored. One of the most important issues was housing. Before 1930, a significant portion of the population could be housed dormitory-style with little provision for privacy, sanitation or comfort. The male laborers were viewed as temporary residents who could endure sub-standard accommodation. Singapore’s Chinatown became one of the most congested areas in the world. Besides this, thousands were squatters in undeveloped areas of the island, such as Toa Payoh and Tampines. In some ways, they were better off than those in the downtown districts because they had space and communities, but they had little access to basic amenities, such as water and electricity. When these new families started having children, the congested conditions grew worse.

The change from a society of transients to a resident society was so quick and dramatic that there was no way to cope. Within a decade, Singapore had to provide homes for tens of thousands of new families and their children. An attempt was made to deal with the problem with the establishment of the Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT), which began to clear slum areas and provide new housing, but the Depression and World War II hindered its progress, and nothing much was achieved until the late 1940s and 1950s.

For the Malays in Singapore, the 1920s and 1930s marked a period of increasing political awareness and a change in the community’s leadership. Some two-thirds or more of the Malay heads of household were literate at least in their own language, close to twice the number for the Chinese. As a result, the Malays were more susceptible to involvement in civil affairs. Their traditional links with the area also motivated them to take an interest in British political decisions that affected their lives.

The Malay population tended to be lumped together by the authorities as a Muslim community and had traditionally been led by wealthy Arab and Arab/Malay families. Many of these Arab families played key roles in Singapore’s economic and social affairs, and their names are remembered to this day – Alsagoff, Aljunied and Alkaff. Many Malays wanted to replace the Arab leadership with Malay leaders. To this end, they fought for a Malay, not Muslim, seat on the legislative council. Their efforts paid off in 1924 when the British expanded the Asian representation on the legislative council and appointed Mohammed Eunos bin Abdullah, a prominent Malay journalist and civic leader, to the council.

Eunos had been editor of Utusan Melayu, which featured local, urban Malay news and commentary on public issues. The newspaper was known for urging Malays to progress and was not afraid to advocate awkward Malay causes. At the same time, the newspaper was impartial and balanced in its criticism and responsive to government pressure. Eunos had also been an informal advisor to the government on Malay affairs and had considerable influence within his own community as well. He was active in social and welfare organizations and was a member of the Muslim Advisory Board. He was appointed Justice of the Peace, then Municipal Commissioner, and finally the first Malay member of the Straits Settlements Legislative Council.

Among the leadership of the Malay community, it was felt that Eunos needed the support of a viable Malay organization to give his views credibility and weight. In 1926, the Singapore Malay Union (SMU) was founded to further Malay interests. Reflecting the Malay desire to be seen as an independent entity, it barred membership to Arab and Indian Muslims. This was the first Malay political organization formed in British Malaya. Led by English-educated journalists, civil servants, and merchants, it provided an interesting contrast to the political leadership of Malaya. While both groups were mostly English-educated, Singapore’s leaders were non-aristocratic, reflecting the urban, immigrant nature of its Malays. The SMU showed that Malays were perfectly capable of political participation in government without the assistance of a traditional ruling elite.

The SMU expanded its activities in the 1930s when it set up branches in Penang and Melaka. In many ways, it was a model for and forerunner of similar groups in the peninsula before World War II – conservative, willing to cooperate with the British, and concerned with furthering Malay educational and economic interests. The SMU’s example and inspiration led to a congress of Malay associations in Kuala Lumpur in 1939, which could be characterized as the beginning of what would become the primary Malay nationalist organization after the war – the United Malays National Organization (UMNO).

More and more Chinese were calling Singapore home, but only a minority viewed the political affairs of Malaya and Singapore with much interest. The Chinese were a divided community with few common causes or interests. Apart from the traditional divisions along dialect, clan, and family lines, the Chinese were also divided between those with roots in the area – the Straits Chinese – and those who were more recent arrivals.

The Straits Chinese were a minority whose political outlook was directed toward their adopted home, Malaya. They were mostly educated in English and had a higher standard of living than their immigrant counterparts. The vast majority, because of their longevity in the area, were British subjects. Their lifestyle, dress, and social activities tended to resemble those of the West and Britain more than those of the Chinese newcomers. The Straits Chinese wanted the focus of Chinese political activities to be on British Malaya, their home and their future. Lim Cheng Ean, a prominent Penang lawyer, speaking in 1931, reflected this view:

Who is to say this is a Malay country? When Captain Light (or in the case of Singapore, Raffles) came here did he find Malays or Malay villages? Our forefathers came here and worked as hard as coolies – weren’t ashamed to become coolies – and they didn’t send their money back to China. They married and spent their money here and in this way the government was able to open up the country from jungle to civilization. We’ve become inseparable from this country. This is ours, our country.

While most Malays would take issue with this view, many Straits Chinese, having lived in the area for generations, saw no reason why the civil service in the Straits Settlements and membership in the legislative council should not be opened up to greater numbers of Asians, especially to non-Malays who were British subjects. Organizing as the Straits Chinese British Association (SCBA), they formed one of the first legal Asian political organizations in British Malaya. Led by Tan Cheng Lock, they lobbied for Straits-born British subjects to have expanded representation in the government. The civil service gradually began to accept and recruit qualified Asians, that is, English-educated Asians, and some Asian members were appointed to the legislative councils of the colonies, although not as many as the SCBA had requested.

Except for this elite minority, most Chinese showed scant interest in the political affairs of British Malaya. They were too busy trying to make a living to be concerned with much else. Like all new immigrants, their frame of reference was the country they had left. Satisfaction with their lives would be framed relative to the conditions of their former lives, and in the early years of their move, those ties were still strong. Thus what little political activity that did exist among the more recent immigrants concerned China. As a result, Singapore had always been fertile ground for raising money to support political activities in China. Dr. Sun Yat Sen, the leader of the 1911 revolution in China, visited Malaya a number of times to raise money and support. After 1911, Dr. Sun’s party, the Kuomintang (KMT), continued to court overseas Chinese, especially Singapore Chinese. The importance of the immigrant communities was evidenced by the fact that the Chinese republican government declared that all overseas Chinese were considered citizens of China unless they publicly and legally renounced their citizenship.

The Chinese community in Singapore had serious divisions along lines of class, dialect group, clan membership and length of residence in the colony. In spite of this, most Chinese saw themselves as a part of the larger Chinese community. One of the first (if not the first) times that this community came together in common political cause was the 1905 boycott of American goods.

Chinese around the world had long resented the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which prohibited further immigration of Chinese to America and prevented Chinese residents of the U.S. from becoming American citizens.

Chinese labor had been drawn to America by the California Gold Rush in 1849 and after that to build the transcontinental railroad. When the gold rush was over and the railroad completed, many remained in the country. American racism and fear of competition for jobs led to the Exclusion Act.

The act was reinforced by an 1884 treaty with China to curtail immigration, and both actions caused deep, worldwide Chinese resentment of Americans. In 1904, the resentment had built to the point where China was forced to withdraw from the treaty but the exclusion laws were still in effect, and in the same year, beginning in Shanghai, Chinese business leaders began to call for boycotts of American goods to protest its immigration policies.

In June 1905, Chinese merchants in Singapore picked up the call for an American boycott. Most of them had roots in the same part of China as those who had gone to America, and this created a degree of solidarity. Singapore Chinese were also insulted by the inherent racism of the Exclusion Act, and many feared that the British might institute a similar law in Singapore.

The boycott was significant because it crossed the fault lines of the Chinese community and appeared to achieve a degree of success. In a request for intervention to the British Foreign Office, the American Embassy in London claimed that “the trade in general is at a standstill.” It is interesting that the Americans also said that the boycott was the action of “unfriendly aliens in a friendly port.” The British however, refused to take action because no laws had been broken.

A branch of the KMT was organized in Singapore in the early 1920s, and much of its activities revolved around promoting Chinese education based on a curriculum formulated in China. As in Malaya, KMT activities in the Chinese schools drew the ire of the British authorities because of their chauvinistic and anti-British rhetoric. Under the governorship of Sir Cecil Clementi (1930–1934), many of their activities were curtailed, and on occasion their leaders were jailed for threatening the peace of the community, although there were only a few thousand active members.

In China, the Nationalist movement up until 1927 had included both the KMT and the communists. This had given the communists opportunities to infiltrate the KMT in Malaya and Singapore, where they competed with the noncommunist KMT activists for support among Chinese students and laborers.

In 1927, General Chiang Kai-shek expelled the communists from the United Front in China, and this in turn brought about a purge in Singapore. Forced underground, the communists regrouped, and in 1930, they formed the Malayan Communist Party (MCP). In the 1930s, the MCP’s activities revolved around organizing Chinese workers, especially in the factories, on the docks, and at the naval base. Strikes called by the communists, although rarely successful, had a disruptive effect on the economy and drew repressive measures from the authorities. By the mid-1930s, the MCP in Singapore probably numbered some five thousand committed members and had some success in influencing the trade union movement. However, like the KMT, it was only able to mobilize a small portion of the recent immigrant population.

The one issue that did capture the interest and emotions of most Chinese in Singapore was the Japanese invasion of China in 1937. The MCP and the KMT in Singapore once again joined in common cause to form the National Salvation Movement. Other organizations followed, including the Hot Blooded Corps, the Traitors Elimination Corps, the Dare-to-Die Corps, the Anti-Enemy Backing Up Society, and the Fragrance of Chrysanthemum Sisters, prostitutes who sold flowers to raise money for the anti-Japanese cause. Led by prominent businessman and philanthropist Tan Kah Kee, successful boycotts of Japanese goods were organized, demonstrations were held, money was raised for China, and campaigns promoted Chinese unity.

As time went on, even these activities ran out of steam. Some Chinese objected to the anti-British rhetoric, and there were inherent divisions within the Chinese community. Ultimately, the KMT and MCP were more interested in furthering the interests of their individual parties than in uniting to oppose the Japanese.

Although Westerners, or Europeans as they were called then, were a fraction of the population, they were the elite. They ruled and ran the trade of the island.

In their commercial lives, European businessmen and civil servants were immersed in the crossroads of race and culture of Malaya. Although plantation rubber came mostly from British companies, the rubber shipped to Singapore from the Dutch East Indies and from smaller producers in Malaya was controlled by Chinese agents. European businessmen dealt with and worked through these Asian retailers and middlemen. For example, the gas stations of Singapore and Malaya were Mobil and Shell franchises that were mainly owned by Chinese, and Europeans traveled throughout the area to improve and expand their networks and interacted significantly with Asians.

After business hours, however, Europeans withdrew into an elite society that was racially and culturally exclusive – the “European” community. Between the two world wars, European society in British Malaya was at its most parochial, imperial, racist and exclusive.

In the first two decades of the twentieth century, the colonial bureaucracy had expanded greatly. Specialized agencies, such as public works, health, the harbor board and the police, had brought in large numbers of British officials. At the top of this official world was the Malayan Civil Service (MCS), the administrative branch of the colonial government. These were the men who ran British Malaya, and they were primarily from the “public school-Oxbridge class,” or as historians P.J. Cain and A.G. Hopkins would say, the “gentlemanly class.” Prior to this, the MCS had employed a more diverse and colorful mix. According to historian James de Vere Allen, the post-war recruits “were not only drawn from a very much narrower sector of British society, but also from a sector which was more than usually intolerant of behavioral eccentricities or people with different social backgrounds in its midst.” The British residents of Singapore were relatively transient and few had multi-generational families that would have been considered socially elite. As a result, the mores of colonial society were determined by those at the top of the administrative ladder – the Malayan Civil Service. These members of the British gentlemanly class determined who was accepted into the elite colonial social circle.

There was another reason for the exclusivity of colonial society. Prior to the 1920s, race had no doubt been an important measure of social standing, but there had been some social interaction between European men and Asian women. Changes in the demographic makeup of European society during the inter-war years curtailed that interaction. As the percentage of married officials and businessmen increased, their wives, who were the organizers and enforcers of colonial social life, defended the color bar and were on the frontline in “maintaining standards.”

The color bar produced some interesting anomalies. Singapore’s prosperity and expansion of public services offered rapid upward social mobility. People of somewhat common backgrounds who worked for the agency houses were accepted because they handled the investments of London’s gentlemanly class. Working in Singapore also meant that many of these businessmen had the wherewithal to advance the social standing of their children by sending them to private boarding schools.

In the 1920s and 1930s, colonial society became more diverse in terms of class origins than it was in Britain. There is anecdotal evidence that many of the British wives came from quite common backgrounds. Travel writer Tatsuki Fujii claims that many scrub women, farmers’ daughters and manicurists became “ladies” in Malaya. Noel Coward was amazed by the smug pretensions and poor manners of Singapore society. At the European-only Tanglin Club, one of the members asked him how he liked the club, saying, “You know the Tanglin Club is one of our best clubs.” Coward replied, “After meeting your best people, now I know why there is such a shortage of servants in London.”

The colonial pecking order made British civil servants instant officers. Those who would have been minor civil servants back home found they had moved into the ruling class in Malaya. They had large homes, servants and membership in private clubs. Virtually every Western man was addressed as “Tuan” (master) by the indigenous people.

However, Europeans who worked in retail trade were excluded from many social circles as this form of trade was not considered a gentleman’s occupation. Thus Singapore was a strange world, in which Westerners who had franchises on filling stations and minor civil servants belonged to all the important clubs, including the bastion of the establishment, the Singapore Club, while prosperous businessmen who ran retail establishments, such as Robinsons, John Little and Whiteaways, were excluded.

When Westerners arrived in Singapore, they were quickly reminded of whose “side” they were on in multiracial, multicultural Singapore. They socialized in clubs and hotels that had clearly defined or implied racial barriers. The Tanglin Club, Cricket Club and Swimming Club only accepted “Whites.” They could negotiate business deals with Chinese businessmen in the morning but could not seal the deals with lunch at their clubs.

Racial exclusivity went beyond just the clubs. General Hospital had a “European” ward. Hotels and restaurants imposed a racial divide. The Raffles Hotel drove Asians away through dress requirements, rudeness and poor service. The Hotel L’ Europe was for whites only. At the movies, Europeans sat upstairs in the “dress circle” and “Asiatics” sat downstairs. Even the Botanical Gardens made it clear that Asians were not welcome. It would seem the only places where the races mixed socially were at the racetrack and in the dance halls and cabarets.

To be fair, photograph albums of Europeans who lived in Malaya at this time invariably include pictures of them with Asians at Chinese restaurants. The Chinese dinner was apparently neutral ground. The albums also show Europeans visiting the homes of Asian acquaintances during Chinese New Year festivities, but the social interaction never went the other way. Journalist George Peet claims the only time he witnessed a social visit by an Asian to a European home was at a Methodist missionary’s house.

It was a seductive life. Most Europeans became instant upper-class citizens. The privileges, the clubs, the social scene and the standard of living made life good in 1920s and 1930s Malaya. They lived in palatial houses with sprawling grounds, and most Europeans had six to eight servants.

In the era before jet travel, tours of duty were three to five years, followed by home leaves of six months to a year. Holidays consisted of visits to that most colonial of institutions – the hill station. The 1920s saw the creation of Fraser’s Hill and Cameron Highlands, temperate-climate retreats to which the Europeans withdrew to recuperate from the efforts of trading, ruling and saving souls in the sweltering tropics. Fraser’s Hill was a little English village transplanted at 1,500 meters (5,000 feet) in the Malayan jungle. It gave even the most ordinary European a taste of genteel country living, no doubt a somewhat ersatz version. Tudor-style cottages came with servants who cooked traditional English country fare. Afternoon tea was scones, strawberries and cream around a cozy fireplace. Gardens blazed with colorful roses, and there was even a village pub.

The 1920s and 1930s marked the arrival of American popular culture on the Singapore scene. American movies and music seemed to take the city by storm. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer set up an office on Orchard Road in 1927, and anywhere from 60–75 percent of the movies shown in Singapore came from the United States. Many of the British lamented the bad influence of Hollywood, citing the reduction in the number of British traveling theater companies that visited the colony. Yet, American movies flourished, and Singapore became a regular stop for movie stars promoting their films. Gloria Swanson, Douglas Fairbanks Jr., Charlie Chaplin and Will Rogers all visited Singapore.

The 1920s and 1930s may have been high points in colonial European society, but, in many ways, they also represented the last moments of Western social dominance. The Japanese threat and the rise of nationalism that would end colonialism in Southeast Asia were just over the horizon.

Singapore censors in the 1960s and 1970s were sometimes criticized by the West for over-curtailing the rights of citizens, but those censors reflect a Western standard that was in place long before Singapore became a nation.

British officials in the 1920s and 1930s were concerned about what people watched on the screen. If you consider the criteria given to the censors of the time, it was amazing any movies were shown. The instructions stated: “All films are objectionable which depict murders, robberies, the modus operandi of thieves, counterfeiters or other criminals, violent assaults on females. Or films which will obviously tend to produce racial ill feeling, set class against class, outrage religious sensibilities of any section of the community, bring the laws or administration of justice into contempt, encourage immorality, pander to solicitous instincts or give rise to a feeling of unrest or insecurity.”