Chapter 22

Hitler’s Secret Book

The Unpublished Sequel to Mein Kampf

In the course of the four years during which Hitler was forbidden to speak in public, he continued to express his worldviews by dictating two more manuscripts of his memoirs and opinions while sojourning at Obersalzberg above Berchtesgaden.

It is astonishing how few people today—even World War II history buffs—have heard about, let alone read, Hitler’s unpublished sequel to the infamous Mein Kampf. Historians and scientific researchers on Hitler’s sphere of influence and the National Socialist period widely fail to study, or refer to, the important source of historically valuable information divulged in Hitlers Zweites Buch (Hitler’s Second Book), at one time referred to as “Hitler’s Secret Book.”

Mein Kampf, on the other hand, has been referenced countless times as a source of Hitler’s Weltanschauung in hundreds of books and articles. To better understand Hitler’s foreign policy, war plans, and persecution of the Jews, among other topics, his “secret” or unknown and unpublished book sheds light on the politician’s early worldview, dictated in 1928, five years before seizing power, and a decade before the inception of World War II.

For clarity’s sake, this “Second Book” should not be confused with Hitler’s “Volume 2” of Mein Kampf. There is the general assumption that, in Landsberg Prison, Adolf Hitler wrote the entire memoir “Four and a Half Years (of Struggle) against Lies, Stupidity, and Cowardice,” the title of which was later shortened to Mein Kampf (My Struggle). It is true that the first volume was, indeed, dictated to his secretary Rudolf Hess in 1924, but the second volume was dictated in Berchtesgaden in 1925 following his early release from prison. These two volumes were later merged and published as Mein Kampf by Max Amann of Eher-Verlag as a single two-part book: volume 1 titled “A Reckoning” and volume 2 “The National Socialist Movement.” However, the unpublished manuscript of Hitler’s “Second Book” discussed below was dictated to a typist in June and July 1928 and is wholly separate from Mein Kampf.

The Discovery of “Hitler’s Secret Book”

Referred to in the 1960s as “Hitler’s Secret Book,” the manuscript was located in the late 1950s by the renowned historian Gerhard Weinberg, a German-born American military historian noted for his studies of National Socialist Germany and World War II. Weinberg has penned a dozen or more books related to these topics, as well as numerous articles for renowned magazines and scientific journals. He was elected president of the German Studies Association in 1996, has been a fellow of the American Council of Learned Societies, and was a Fulbright professor at the University of Bonn, a Guggenheim Fellow, and a Shapiro Senior Scholar in Residence at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, among many other such honors.1

In 2009, Weinberg was chosen as the recipient of the $100,000 Pritzker Military Library Literature Award for lifetime excellence in military writing, and in 2011 he was awarded the Samuel Eliot Morison Prize, a lifetime achievement award given by the Society for Military History. The listing of Weinberg’s accomplishments and reputation has been included with the aim of validating the authenticity of the manuscript in question: Hitler’s unpublished book.

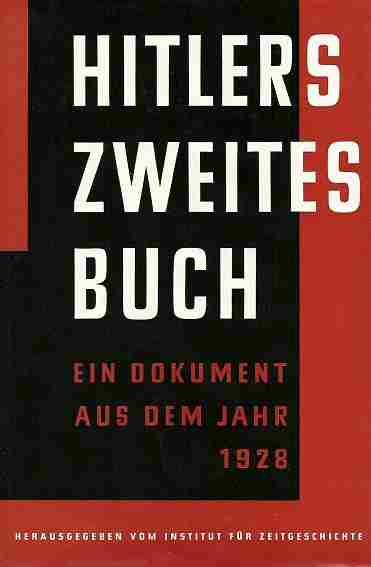

The actual document dictated by Adolf Hitler in 1928, but never published during his lifetime, was hidden away in a cache of confiscated German records in Alexandria, Virginia, until it was located by Gerhard Weinberg in 1958. Though the manuscript was subsequently published in Germany by the Institute for Contemporary History in Munich in 1961, the work titled Hitlers Zweites Buch: Ein Dokument aus dem Jahr 1928 (Hitler’s Second Book: A Document from the Year 1928) sold out quickly and was not published in Germany again until 1995, when it reappeared as part of a series titled Hitlers Reden, Schriften, Anordnungen (Hitler’s Speeches, Writings, Directives), edited by the same institute.

In 2006, Weinberg edited an English-language version of the original text, translated by Krista Smith and published by Enigma Books, an edition that included Weinberg’s thought-provoking introduction to the historical document. It is a shame, however, that Hitler’s Second Book is out of print today, as it contains some highly interesting statements regarding the future Führer’s views on Great Britain and the United States, as well as on the choice of allies he had in mind for the new Germany. As early as 1928, Hitler came to the conclusion that Germany would need to prepare for war with the United States, a plan that helps us understand why, already in 1937, he ordered the development of intercontinental bombers and long-haul super-battleships.2

Having stated that the English-language book is no longer available, there still exist limited copies of a Bramhall House (New York) edition reprinted in 1986 with introductions by notable historians William Shire and Telford Taylor. Apparently, a pirated version is in circulation, mostly as an electronic book, that is the result of an untrustworthy translation and is allegedly published by a right-wing editor.

Authenticating the Manuscript

Knowing that a purported diary of Adolf Hitler was exposed as a fake,3 that false Hitler quotes have been in circulation, and that works of art attributed to Hitler were revealed as forgeries, it is essential to validate the authenticity of Weinberg’s astonishing 1958 discovery. The historian had followed a lead from a 1949 book written by Albert Zoller, a French officer who carried out the interrogations of Hitler’s secretary Christa Schroeder and whose report made mention of an unpublished book on foreign policy dictated by Hitler. The second mention of the manuscript came from Hitler himself when he said, “In 1925 I wrote in Mein Kampf (and also in an unpublished work) that world Jewry saw in Japan an opponent beyond its reach.”4

Meanwhile, thanks to Josef Berg,5 a colleague of Hitler’s publisher Max Amann, the Institute of Contemporary History in Munich also got wind of the alleged existence of another book. Berg claimed that Hitler had dictated the manuscript to Amann and that, in addition to the copy in the publisher’s safe, a second copy had been stored at Obersalzberg. Both claims would be confirmed with the discovery of the manuscript. Weinberg located the document among files that U.S. authorities were in the process of microfilming: the book in question had been laid aside and erroneously thought to be simply a draft of Mein Kampf. Along with the long sought-after manuscript was the confiscation memo proving that an American officer had obtained it from Hitler’s publisher, Eher-Verlag, in May 1945, after the book was handed over by Josef Berg with the claim that it was a work written by Hitler more than fifteen years earlier.6

When the 1961 German-language publication was released in Germany, Albert Speer noted in his diary that he remembered that Hitler, at the time of the construction of the Berghof in the mid-1930s, had “accepted a hundred-thousand-mark advance” from Eher-Verlag “for a manuscript that he—for reasons of foreign policy—did not yet wish to see published.”7

Also, a letter dated June 26, 1928, signed by Hitler’s personal secretary Rudolf Hess in Hitler’s chancellery in Munich, responded to someone’s request for an appointment with Hitler as follows: “Herr Hitler is likely to be in Berlin for several days at the beginning of July. A visit . . . can hardly be considered earlier, as Herr Hitler will probably be away from Munich until his trip to Berlin, in order to write his book.”8 In addition, Weinberg also compared passages in the original manuscript that correspond to events that took place in 1928.9

Why Was the Book Kept Secret?

Weinberg suggests that Amann likely advised against publishing Hitler’s second book due to the poor sales of Mein Kampf in 1928, with only 3,015 copies sold. Additionally, the financial struggles of the National Socialist Party at the time, including the forced cancellation of their annual rally for lack of funds, would have made it unwise to invest in a new book that could compete with Mein Kampf.10 Furthermore, the political and economic developments of 1929 would have required extensive revisions to the original manuscript, which Hitler did not have time for.11 Speer also cited “foreign policy reasons” for Hitler’s failure to publish his 1928 manuscript. The blatant proposition of a new war to acquire vast territories in Eastern Europe and the constantly repeated disavowal of the 1914 borders as the goal of German policy could have led Hitler, especially in the first years after his rise to power, to view the publication of his “foreign policy position” as inopportune.12

Hitler’s 1928 Manuscript: Content and Excerpts

The “Second Book” by Hitler, with its focus on foreign policy, serves as a crucial source of insight into the period when Hitler was still vying for power. It offers an unfiltered view of his ideology and subsequent policies as leader of the Third Reich. In an effort to highlight the most significant and revealing discussions contained in the 238 pages of the manuscript, this text provides section titles for thematic organization. It’s important to note that the book was never edited after its initial dictation, and the English translation will feature any original errors or omissions.

The Ongoing Fight for Bread and Land

In chapter 1, Hitler’s first line states that “politics is history in the making. History itself represents the progression of a people’s struggle for survival.”13 He explains that the instinct of self-preservation

corresponds to the two most powerful motivations in life: hunger and love. While the . . . satisfaction of the eternal hunger guarantees self-preservation, the gratification of love secures its furtherance. In truth, these two impulses are the rulers of life. . . . The laws that apply to the individual are the same for a society: a people is a collectivity of more or less equal people who need to fight for their self-preservation and continuity.14

Hitler elaborates on the creation of the planet and, finally, the appearance of humans who eventually form “families, tribes, peoples, states.”15 Humans fight off animals—and each other—in the pursuit of self-preservation. Politics, he maintains, “is the art of the implementation of this struggle.”16

The next discussion raises the argument that war is dangerous because it “leads to a racial selection within a people; this means a disproportionate destruction of the best elements.”17 The most courageous, idealistic, valorous, and strong men of the nation are willing to sacrifice their lives on the battlefield “for the benefit of the community,” in contrast to “those pathetic egoists who see the preservation of their own strictly personal existence as the highest duty of this life. The hero dies, the criminal . . . survives.”18 Hitler concludes this thought by stating that war should only be considered as a means to preserve this existence.

A peaceful society, he argues, will eventually weaken: rather than fight for their bread, they will be content with less bread or leave their homeland in search of better conditions. “The farm boy who emigrated to America 150 years ago was the most determined and boldest in his village.”19 As a consequence, migration from Germany will in the long run deprive the nation of its “best bloodline” and reduce its population. Hitler sums up by stating, “Fundamentally peaceful policy becomes a scourge for the people.”20

In chapter 2 Hitler states that “the most secure basis for the existence of a people has always been its own territory and land.”21 However the growth of a healthy population must be proportionate to the nation’s Lebensraum (living space). He proceeds to endorse a policy of invasion for the acquisition of additional territory to feed the population. He says,

The human life lost on the battlefield will automatically be replaced many times over. Thus, from the distress of war grows the bread of freedom. The sword breaks the path for the plow, and if one wishes to speak of human rights, then in this one case war has served the highest right: it gave land to a people that wishes to cultivate it industriously and honestly and which can in the future provide daily sustenance for its children.22

In his argument, Hitler does not mention the rights of those from whom the Germans are stealing the land. He then describes the dangers of international trade and commerce and concludes that a population and its Lebensraum must be in a healthy proportion to each other, but to achieve that, a people needs weapons because “land acquisition is always linked to the use of force.”23

Germany’s Armed Forces and Racial Superiority

In the same chapter, Hitler uses the example of the subjugation of 350,000 Helots through the greater strength of only six thousand Spartans due to their “racial superiority.” Here he reveals his views on eugenics and child euthanasia in order to breed these alleged supermen whose

racial superiority . . . was the result of systematic racial preservation, so we see in the Spartan state the first racialist state. The abandonment of sick, frail, deformed children—in other words, their destruction—demonstrated greater human dignity and was in reality a thousand times more humane than the pathetic insanity of our time, which attempts to preserve the lives of the sickest subjects—at any price—while taking the lives of a hundred thousand healthy children through a decrease in the birth rate or through abortifacient agents, subsequently breeding a race of degenerates burdened with illness.24

In chapter 3 Hitler claims that the “handing over of our weapons” as ordered by the Versailles Treaty was insignificant—“weapons can rust.”25 The significant issue was the destruction of the German army, he maintains. Hitler praises the military as a time-honored product of the German people:

The German army at the turn of the century was still the greatest organization in the world and its effectiveness was more than beneficial for our German people. The breeding ground of German discipline, German efficiency, even disposition, open courage, bold recklessness, tenacious perseverance, and unyielding honesty. The sense of honor of an entire profession gradually and imperceptibly became the common property of an entire people.26

He also boasts about the social equality of the German armed forces, in which the meritorious, and not only the rich or titled, can become officers and leaders.

Hitler goes on to maintain that Germany has been unarmed many times throughout history but that “our real defenselessness lies in our pacifist-democratic contamination, as well as in the internationalism that destroys and poisons our people’s most significant sources of strength.”27 He claims that “the source of a people’s entire power lies not in its store of weapons or its army organization, but in its inner quality—represented by the racial significance or racial value of a people, by the presence of superior individual personal qualities, and by a healthy attitude toward the idea of self-preservation.”28 He continues by arguing that “all peoples are not the same” and that their values and culture “provide a benchmark for the overall valuation of a people.” He concludes this racial assertion by stating, “The higher the racial worth of a people, the greater its overall value, [through] which, in conflict and in the struggle with other peoples, it must then mobilize for the benefit of its life.”29

The Führer Principle

In chapter 4 Hitler examines the value of learning from history and suggests forcing the acquired values and way of life on the German people—whether they agree with them or not.

Thus, for those who feel called to educate a people, it is their task to learn from history and to apply their knowledge practically, without regard to the understanding, comprehension, ignorance, or even repudiation of the masses. The greatness of a man is all the more significant the greater his courage to use his superior insight—in opposition to the generally prevailing but ruinous view—to lead to overall victory. The National Socialist movement would have no right to consider itself a truly great phenomenon in the life of the German people if it did not summon the courage [to] learn from the experiences of the past and impose on the German people the laws of life that it represents, despite all opposition.30

Praise for Bismarck

Chapter 6 includes a brief history lesson in which Hitler praises Otto von Bismarck for his successes in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871. Approvingly, he reiterates, “A large number of German states that were previously only loosely allied with each other—and historically were not infrequently hostile to each other—were united into one Reich. . . . A province of the old Holy German Empire, lost 170 years earlier (which had been definitively annexed by France in a brief theft), came back to the motherland [now known as Alsace Lorraine].”31 However, Hitler strongly lamented Germany viewing these new subjects as citizens of the Reich: “It was problematic that this state included [over three] million Poles and [figures unknown] from Alsace and Lorraine who had become French. This conformed neither to the idea of a nation state nor to that of an ethnic state.”32

Hatred for the Poles

Hitler sees no chance of including Polish people in the Germany nation and recommends their “removal”:

[The nation-state] would also have to instill German thoughts in these people, through [their] education and life, and turn them into bearers of these ideas. This was weakly attempted, possibly never seriously desired, and in reality the opposite was achieved. The ethnic state, in contrast, could under absolutely no circumstances annex Poles with the intention of turning them into Germans one day. It would instead have to decide either to isolate these alien racial elements in order to prevent the repeated contamination of one’s own people’s blood, or it would have to immediately remove them entirely, transferring the land and territory that thus became free to members of one’s own ethnic community.33

Lessons from World War I and Expansionist Aims

Chapter 7 includes a detailed criticism of the Triple Alliance—the secret 1882 agreement between Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy. Though Otto von Bismarck was the principal architect of the alliance, Italy’s aim was mostly to gain support against France shortly after losing its North African ambitions to the French. Hitler bemoans Germany having been “pushed into the war” and views the alliance as follows:

But the benefits of the Triple Alliance lay exclusively on the Austrian side. Due to determining factors in the policies of the individual states, only Austria could ever be the beneficiary of this alliance. . . . It was a defensive alliance, which, according to the provisions of the agreement, was at most only intended to secure the maintenance of the status quo. Because of the impossibility of sustaining their people, Germany and Italy were forced to adopt an offensive policy.34 . . . In reality, the advantages of the alliance with Austria lay all on Austria’s side, while Germany had to bear all the disadvantages. And they were not few.35

He also laments how, due to this alliance, Germany took all the undue blame for having initiated World War I.

Still recalling Germany’s expansionist failures in the Great War, Hitler advocates vast enlargement for Germany:

however, only through a territorial policy in Europe could the population resettled there, be preserved for our people including their military utilization. An additional 500,000 square kilometers of land in Europe can provide millions of German farmers with new homesteads, and can add to the strength of the German people millions of soldiers available for the decisive moment. The only area in Europe that could be considered for such a territorial policy was Russia. The sparsely populated western areas bordering Germany (which had already once welcomed German colonizers as bearers of culture) also came into consideration for the new European territorial policy of the German nation.36

Though Hitler explicitly refers to the rape of Russian land, to give an idea of Hitler’s goal of acquiring half a million square kilometers of territory for the resettling of German farmers, France was roughly that size in 1928 or, to offer an example on Germany’s eastern borders, Poland and Czechoslovakia together corresponded more or less to the landmass that Hitler coveted.

In chapter 8 Hitler expresses his views on the disasters of the Great War:

The only war aim that would have been worthy of these enormous casualties would have been to promise the German troops that so many hundreds of thousands of square kilometers of land would be allotted to the frontline soldiers as property or made available for colonization by Germans. In that way, the war would also immediately have lost the character of an imperial undertaking and would instead have become a matter of concern to the German people. Because ultimately, the German soldiers did not really shed their blood so that the Poles could obtain a state. . . . In 1918 we thus stood at the conclusion of a completely pointless and aimless waste of the most valuable German blood.37 Once again, our people offered up infinite heroism, courage in the face of sacrifice—yes, courage in the face of death—and willingness to accept responsibility, and nevertheless had to leave the battlefield defeated and weakened. Victorious in a thousand battles and engagements, yet still conquered by the losers in the end.38

He also repeats the widely propagated lie about Germany’s forced surrender:

On November 11, 1918, in the forest of Compiègne, the armistice agreement was signed. For this, fate had destined a man who had been one of the chief culprits in the disintegration of our people. Matthias Erzberger, representative of the Center Party—and, according to various claims, the illegitimate son of a maid and a Jewish employer—was the German negotiator who then also signed his name to a document which, unless one assumes a deliberate intent to destroy Germany, appears incomprehensible in light of the four and a half years of heroism demonstrated by our people.39

Erzberger’s opponents circulated the fabricated contention that he was part Jewish,40 an untruth that was widely repeated in the post–World War I era.

The chapter also includes a dramatically formulated critique of Germany’s surrender at the end of the war:

People should not speak of national honor, particularly in today’s Germany, and people should not attempt to give the impression that national honor can [again] be preserved through any sort of outwardly directed rhetorical barking. No, that cannot be done—because it no longer exists at all. And it has by no means disappeared because we lost the war or because the French occupied Alsace-Lorraine, the Poles stole Upper Silesia or the Italians took South Tyrol. No, our national honor is gone because the German people, in the most difficult time of its struggle for survival, demonstrated a lack of conviction, shameless servility, and cringing, groveling tail-wagging that can only be called shameless. Because we gave in pathetically without being forced to do so, because the leadership of this people, against historical truth and its own knowledge, assumed the war guilt—yes, burdened our entire people with it.41

Interestingly, Hitler vents his anger more at the so-called November Criminals—the politicians who negotiated and signed the 1918 Armistice—than at the World War I enemies of the Reich:

Anyone who today wants to act in the name of German honor must first announce the most relentless fight against the intolerable defilers of German honor. But those are not our former opponents; rather, they are the representatives of the November crime. That collection [of] Marxist, democratic-pacifist, and Centrist traitors that pushed our people into its current state of powerlessness. Upbraiding one-time enemies in the name of national honor while acknowledging as gentlemen the dishonorable allies of these enemies in our own midst—that fits with the national dignity of this current so-called national bourgeoisie. I admit most frankly that I could reconcile myself with every one of those old enemies, but that my hate for the traitors in our own ranks is unforgiving and will remain. What the enemies did to us is serious and humiliating for us, but the sins committed by the men of the November crime—that is the most dishonorable, dastardly crime of all time. By attempting to bring about circumstances that will someday force these creatures to accountability, I am helping to restore German honor.42

German Emigration to the United States

Chapter 9 begins with Hitler deploring the fact that so many Germans were forced to emigrate due to lack of space. In particular he mentions those who lived in the United States (referred to as the American Union):

under no circumstances will they be able to participate any longer in the motherland’s struggle with destiny in any significant way, nor in the cultural development of their people. Whatever the Germans in North America achieve specifically, it will not be credited to the German people, but is forfeited to the body of culture of the American Union. Here the Germans really are only the cultural fertilizer for other peoples everywhere. Yes, in reality the greatness of these peoples, to a high degree, is not infrequently [attributable] to achievements contributed by Germans.43

However, Hitler already sees German emigrants to English-speaking countries as a lost cause: “But because the German people does not consist of Jews, the [Germans?] in Anglo-Saxon countries in particular will, unfortunately, nevertheless become progressively more anglicized. They will presumably also become spiritually and intellectually lost to our people in the same way that their practical work achievements are already lost to our people.”44

Return of German Lands through War

Conversely, Hitler sees hope for those Germans still residing near the borders of the Reich, though their regions’ return to the Reich would come only at the cost of war: “But with regard to the fate of those Germans who were forcibly cut off from the German body politic through the Great War and the peace treaties, it must be said that their fate and their future is a question of politically regaining the power of the motherland. Lost territories are not regained through protest campaigns but by a victorious sword.”45

Hitler’s Praise for the United States

Though Hitler expresses next to no hope for Germany’s success in international trade, he begrudgingly cites America’s successes:

in addition to all the European states that are struggling for the world market as export nations, the American Union is now also the stiffest competitor in many areas. The size and wealth of its internal market permits production levels and thus production facilities that decrease the cost of the product to such a degree that, despite the enormous wages, underselling [by Germany] no longer seems at all possible. The development of the automotive industry can serve as a cautionary example here. It is not only that we Germans, for example, despite our ludicrous wages, are not in a position to export successfully against the American competition even to a small degree; [at the same time?] we must watch how American vehicles are proliferating even in our own country.46 This is only possible because the size of the internal American market and its wealth of buying power and also, again, raw materials guarantee the American automobile industry internal sales figures that alone permit production methods that would simply be impossible in Europe due to the lack of internal sales opportunities. At issue is the general motorization of the world—a matter of immeasurable future significance. For the American Union, in any case, today’s automobile industry leads all other industries.”47

Once again praising the United States, this time Hitler weaves his views of “racial superiority” into the picture and regrets the emigration of the Nordic peoples from Europe:

This gradual removal of the Nordic element within our people leads to a lowering of our overall racial quality and thus to a weakening of our technical, cultural, and also political productive forces. The consequences of this weakening will be particularly grave for the future because now a state is appearing as an active participant in world history which for centuries, as a true European colony, obtained through the emigration of Europe’s best Nordic forces, which has now, facilitated by the commonality of the original blood, formed these forces into a new national community of the highest racial quality.48

“It is not by chance,” he continues,

that the American Union is the state in which by far the greatest number of bold, sometimes unbelievably so, inventions are currently taking place. Compared to old Europe, which has lost an infinite amount of its best blood through war and emigration, the American nation appears as a young, racially select people. Just as the achievements of a thousand degenerate Levanters49 in Europe—say, on Crete—cannot equate with the achievements of a thousand racially much superior Germans or Englishmen, the achievements of a thousand racially questionable Europeans cannot equate with the capabilities of a thousand racially first-rate Americans.50

Hitler perceives the United States as being a “Nordic-Germanic state and not at all a mishmash of peoples”51 and commends the United States for having implemented a strict immigration quota: “the American Union itself, motivated by the theories of its own racial researchers, established specific criteria for immigration.”52 “By making an immigrant’s ability to set foot on American soil dependent on specific racial requirements on the one hand as well as a certain level of physical health of the individual himself . . . 53 Scandinavians,” he continues, “then Englishmen and finally Germans are allocated the largest contingents. Romanians and Slavs very limited; Japanese and Chinese one would rather exclude altogether.”54

Germany’s Military Vulnerability and Future Allies

In chapter 11 Hitler examines Germany’s vulnerable situation in the event of attack: “Germany is currently encircled by three power factors or power groups. England, Russia, and France are currently Germany’s militarily most threatening neighbors. . . . Germany lies wedged between these states, with completely open borders.”55 He worries about the great length as well as the lack of natural obstacles along Germany’s border with France and points out that much of this zone includes Germany’s principle industrial area and that fighting over it could lead to the destruction of the nation’s resources.56 He mentions that Germany’s second largest industrial region, Saxony, would be endangered should Czechoslovakia join the fray.57 If Poland were involved as well, he adds, Germany would be open to attack along that border, a mere 175 kilometers (109 mi) from the capital, Berlin.58

Hitler drives the point home by claiming, “France comes into question as the most dangerous enemy because, thanks to its alliances, it is in a position to be able to threaten almost all of Germany with airplanes within an hour of the outbreak of a conflict. Germany’s military counteraction against the application of this weapon is, all things considered, currently nil.”59 Russia’s alliance with France in World War I makes Hitler cautious:

there are still well-intentioned national men who believe in all seriousness that we must enter into an association with Russia. Considered even from a purely military perspective, such an idea is unfeasible or disastrous for Germany. Just as prior to 1914, today we can also always assume it to be absolutely certain that in every conflict in which Germany will become entangled—regardless of the reasons and regardless of the causes—France will always be our enemy. Whatever European combinations may appear in the future, France will always cooperate with the anti-German ones.60

He maintains that France’s possession of Alsace-Lorraine does not, in any way, satisfy its long-term intentions and that its hopes are “still the conquering of the Rhine border; [and] the tearing up of Germany into individual states, as loosely attached to one another as possible.” Hitler also ascertains that “actually, France has never taken part in a coalition that would also have advanced German interests in any way. In the last three hundred years, up to 1870, Germany has been attacked by France twenty-nine times.”61

As was his custom, Hitler pitches racial slurs into his attack on the French in no uncertain terms

French nationalist chauvinism has removed itself so far from ethnic viewpoints that in order to satisfy a pure urge for power the French allow their own blood to be niggerized [sic] just to be able to maintain the numerical character of a “Grandnation” [sic]. France will thus also be a perpetual international troublemaker until a decisive and thorough instruction of this people is undertaken one day. For the rest, no one has characterized the character of French vanity better than Schopenhauer with his dictum: Africa has its monkeys and Europe its French.62

Hitler’s ongoing obsession with a perceived “Jewish-capitalist Bolshevik Russia” and its imminent threat to Germany is made clear in his claim that “any European coalition that does not mean tying down France is automatically prohibited for Germany.”

The belief in a German-Russian understanding is fanciful as long as a government that is preoccupied with the sole effort to transmit the Bolshevist poison to Germany rules in Russia. Thus, when communist elements agitate for a German-Russian alliance, this is then natural. They justly hope that in doing so, they can bring Bolshevism to Germany itself. But it is incomprehensible when nationalist Germans believe that they can arrive at an understanding with a state whose highest interest includes the destruction of precisely this nationalist Germany. It goes without saying that if such an alliance were to materialize today, its result would be the complete dominance of Judaism in Germany, just as in Russia.63

He also issues a warning: “So if a German-Russian alliance were one day to have to stand the test of reality—and there are no alliances without thoughts of war—then Germany would be exposed to the concentric attacks of all of western Europe without being able to mount any serious resistance of its own.”64 Hitler closes chapter 11 with a glimpse of his future actions: “For Germany, a future alliance with Russia has no sense . . . the goal of German foreign policy . . . in the one and only place possible: [acquiring] space in the East.”65

British “World Colonization” as a Model

In chapter 14, in defense of his own expansionist ambitions, Hitler expresses his admiration for British racial attributes and Britain’s world colonization. “The pride of the English today,” he observes,

is no different than the pride of the ancient Romans. It is mistaken to believe that world empires owed their origin to chance or that at least the events that determined their development were random historical incidents that always turned out well for a people. Ancient Rome, just like England today, owed its greatness to the correctness of Moltke’s dictum that “in the long run luck is only with the competent.” This competence of a people, however, does not lie in its racial worth alone, but also in the capability and skillfulness with which this worth is employed. A world empire of the magnitude of ancient Rome or current Great Britain is always the result of marrying the highest genetic quality with the clearest political objective. The objective of today’s England is determined by the quality of the Anglo-Saxon people itself and the insular location. It was part of the Anglo-Saxon people’s character to pursue space. Inevitably, this drive could only find its fulfillment outside today’s Europe.66

In his final discourse, chapter 16, Hitler concludes that, despite the fact that Germany and Italy fought on opposing fronts in World War I, a future alliance should be welcome for both parties: “A nationally aware Germany and an equally proud Italy will one day—through their sincere, mutual friendship, based on common interests—also be able to heal the wounds left by the Great War.” And again: “Only a National Socialist Germany will find the way to an ultimate understanding with fascist Italy and definitively eliminate the danger of military conflict between the two peoples.” He also adds Great Britain into his planned alliance: “So if one examines Germany’s foreign policy options more closely, then only two states actually remain as potential valuable allies for the future: Italy and England. Italy’s relationship with England itself is already a good one today.”67

Broadening his scope of allies, he adds: “Spain and Hungary can also already be assigned to this community of interests today—if only quietly.68 . . . In the distant future, one could then perhaps imagine a new association of nations—composed of individual states of superior national quality—that could then perhaps challenge the imminent overpowering of the world by the American Union.”69

Hitler’s War against International Jewry

In the final statements and arguments of his two-hundred-and-some pages on domestic and foreign policy, Hitler returns to his ongoing obsession with the “Jewish Question”:

The war against Germany was waged by a most powerful international coalition in which only some of the states could have had a direct interest in the destruction of Germany. . . . The power that initiated this enormous war propaganda campaign was international Jewry.70 The Jews, although they are a people whose core is not entirely uniform in terms of race, are nevertheless a people with certain essential particularities that distinguish it from all other peoples living on the earth.

Judaism is not a religious community; rather, the religious ties between the Jews are in reality the current national constitution of the Jewish people. The Jew has never had his own territorially defined state like the Aryan states. Nonetheless, his religious community is a real state because it ensures the preservation, propagation, and future of the Jewish people. . . . The fact that no territorial boundaries underlie the Jewish state—as is the case with Aryan states—is associated with the fact that the essence of the Jewish people lacks the productive forces to build and sustain a territorial state.71

Here Hitler brings in the National Socialist ideology of “blood and soil,” in contrast to the purported values of his “enemy”:

But here the struggle for survival takes various forms, corresponding to the entirely different natures of the Aryan peoples and the Jews. The basis of the Aryans’ struggle for survival is the land, which is cultivated by them and which now provides the general basis for an economy that, in an internal cycle, satisfies their own requirements through the productive forces of their own people. The Jewish people, because of its lack of productive capabilities, cannot carry out the territorially conceived formation of a state; instead, it needs the labor and creative activities of other nations to support its own existence. The existence of the Jew himself thus becomes a parasitic existence within the life of other peoples.72

Hitler proceeds to demonize the Jew as an apocalyptic force that threatens every nation on earth:

The ultimate goal of the Jewish struggle for survival is the enslavement of productively active peoples. Weapons assisting him in this are the attributes of shrewdness, cleverness, cunning, disguise, and so on, which are rooted in the character of his people. They are stratagems in his fight to preserve life, just like the stratagems of other peoples in military conflict. In terms of foreign policy, he attempts to get the peoples into restlessness, divert them from their true interests, hurl them into war with one another, and thus gradually—with the help of the power of money and propaganda become their masters. His ultimate aim is the denationalization and chaotic bastardization of the other peoples, the lowering of the racial level of the highest, and domination over this racial mush through the eradication of these peoples’ intelligentsias and their replacement with the members of his own people.73

Hitler’s final xenophobic statement on a perceived imminent threat posed by “the Jew” is that National Socialists will lead the decisive fight to save humanity from “International Jewry’s” downward spiral of inevitable doom:

The Jewish international struggle will therefore always end in bloody Bolshevization—that is to say, in truth, the destruction of the intellectual upper classes associated with the various peoples, so that he himself will be able to rise to mastery over the now leaderless humanity. In this process, stupidity, cowardice, and wickedness play into his hands. Bastards provide him the first opening to break into a foreign ethnic community. Jewish domination always ends with the decline of all culture.74 . . . The fiercest struggle over the victory of the Jews is currently taking place in Germany. Here it is the National Socialist movement alone that has taken up the fight against this execrable crime against humanity.75

It is clear that when Adolf Hitler was thirty-nine years old, five years before he came to power, he held well-defined opinions about the political, economic, and social state of the world. In “Hitler’s Second Book,” he expresses his intentions to impose his will on the German people, his preference for certain alliances with countries like Italy, his proposals for a war of expansion in Eastern Europe, and his plan for a National Socialist campaign against global “Jewry.”

Regrettably, when he and the National Socialists rose to power in 1933, Hitler’s 1928 domestic and foreign policies were, indeed, implemented. Thanks to a state-of-the-art propaganda assault on the German people, the creation of an efficient terror organization, and the prodigious remilitarization of the Reich, Hitler’s twelve-year reign would generate the greatest calamity in recorded human history.

Notes

1. “Gerhard Weinberg,” PritzkerMilitary.org, https://www.pritzkermilitary.org/explore/commemorate-their-service/gerhard-weinberg-honorial.

2. Gerhard Weinberg, Foreword to Hitler’s Second Book: The Unpublished Sequel to Mein Kampf, by Adolf Hitler (New York: Enigma Books, 2006).

3. Robert Harris, Selling Hitler: The Story of the Hitler Diaries (New York: Pantheon, 1986).

4. Percy Ernst Schramm, ed., Hitlers Tischgespräche im Führerhauptquartier 1941–1942 (Stuttgart: Seewald, 1965), 178.

5. Adolf Dresler, Geschichte des “Völkischen Beobachters” und des Zentralverlags der NSDAP (Munich: Zentralverlag der NSDAP, 1937), 89.

6. Gerhard Weinberg, Introduction to Hitler’s Second Book: The Unpublished Sequel to Mein Kampf, by Adolf Hitler (New York: Enigma Books, 2006).

7. Albert Speer, Spandauder Tagebücher (Frankfurt am Main: Ullstein, 1975), 533.

8. Rudolf Hess to the Gauleitung Hannover-Nord of the NSDAP, June 26, 1928, with notation of receipt June 28, 1928; Niedersächsischen Hauptstaatsarchiv Hannover, Des. 310 I A 19.

9. Weinberg, Introduction to Hitler’s Second Book.

10. Oron James Hale, “Adolf Hitler: Taxpayer,” American Historical Review 60, no. 4 (July 1955): 830–42.

11. Gerhard Weinberg, Introduction to Hitler’s Second Book.

12. Ibid.

13. Adolf Hitler, Hitler’s Second Book: The Unpublished Sequel to Mein Kampf, by Adolf Hitler (New York: Enigma Books, 2006), 7.

14. Ibid., 7–8.

15. Ibid., 9.

16. Ibid.

17. Ibid., 11.

18. Ibid.

19. Ibid., 13.

20. Ibid., 14.

21. Ibid., 16.

22. Ibid., 17.

23. Ibid., 27.

24. Ibid., 20.

25. Ibid., 28.

26. Ibid., 30.

27. Ibid., 30–31.

28. Ibid., 31.

29. Ibid.

30. Ibid., 38–39.

31. Ibid., 49.

32. Ibid., 49–50.

33. Ibid., 50.

34. Ibid., 73.

35. Ibid., 66.

36. Ibid., 78.

37. In World War I, 1,885,291 German soldiers were killed and 4,248,158 were wounded. See Statistisches Jahrbuch für das Deutsche Reich 1924–25 (Berlin: Herausgegeben vom Statistischen Reichsamt. Verlag für Politik und Wirtschaft, 1925), 25.

38. Hitler, Hitler’s Second Book, 83–84.

39. Ibid., 81.

40. See Klaus Epstein, Matthias Erzberger and the Dilemma of German Democracy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1959).

41. Hitler, Hitler’s Second Book, 96–97.

42. Ibid., 98.

43. Ibid., 99.

44. Ibid., 100.

45. Ibid., 100–101.

46. In 1927, 35,686,000 Reichsmarks’ worth of motorcycles and motor vehicles were exported from the United States to the German Reich. At that time, equivalent German goods valued at 693,000 Reichsmarks were sold in the United States. See Statistisches Jahrbuch für das Deutsche Reich 1928 (Berlin: R. Hobbing, 1928), 327f.

47. Hitler, Hitler’s Second Book, 106–107.

48. Ibid., 108–109.

49. Levanters = inhabitants of the Levant, the Mediterranean lands east of Italy.

50. Hitler, Hitler’s Second Book, 109

51. Ibid., 118.

52. Ibid., 118, footnote by Weinberg: “Allusion to the May 26, 1924, Immigration Act of 1924 to limit the immigration of aliens into the United States, which regulated immigration into the U.S.A. much more tightly. The First Quota Act of May 19, 1921, had already established maximum limits for individual ethnic groups.”

53. Ibid., 109

54. Ibid., 118.

55. Ibid., 136.

56. Ibid.

57. Ibid., 137

58. Ibid., 138.

59. Ibid., 139.

60. Ibid., 140.

61. Ibid., 141.

62. Ibid., 144.

63. Ibid., 144–45.

64. Ibid., 148.

65. Ibid., 153.

66. Ibid., 160–61.

67. Ibid., 229–30.

68. Ibid.

69. Ibid., 231.

70. Footnote by Weinberg: “As is generally known, the situation was precisely the opposite. To the extent that one can even speak of a ‘Jewish’ position in World War I, it was—due to the pogroms in Russia—more pro- than anti-German.”

71. Ibid., 233.

72. Ibid., 234.

73. Ibid.

74. Ibid., 234–35.

75. Ibid., 237.