To protect banks’ depositors from a loss in case of bankruptcy. Depositors are small atomized creditors. They do not have access to sufficient information in order to monitor their bank properly (Dewatripont and Tirole, 1994).

To protect banks’ depositors from a loss in case of bankruptcy. Depositors are small atomized creditors. They do not have access to sufficient information in order to monitor their bank properly (Dewatripont and Tirole, 1994).Over the past 5 years, a considerable amount of work has been undertaken by the Basel Committee, by practitioners, and by academics in order to design a new master regulatory framework for banks. The task is proving a real challenge because the banking industry has undergone substantial transformations as a consequence of the deregulation of financial markets. At the same time, risk management and risk transfer have gained in sophistication. Regulators, therefore, have to cope with two different issues simultaneously. First and foremost, they want to provide an accurate insolvency frontier applicable to banks, in order to avoid macroeconomic and microeconomic shocks. In addition they aim at educating banks in order to set common risk practices among the financial community.

The current regulatory framework (Basel I) was initiated in 1988. The regulatory constraint expressed by the 1988 “Cooke ratio” (discussed later in the section on banking regulation) has quickly been bypassed by banks thanks to innovation and arbitrage. Based on this experience, the main concern with the new accord currently under development (Basel II) is related to its potential flexibility in order to cope with the ongoing developments of financial markets. Another source of concern is the risk that the new accord may hinder a sufficient level of diversity across the banking industry.

In this chapter we first review regulation from a historical point of view and focus on the microeconomics of regulation. We then describe the main limitations of the first Basel Accord, and we review the main components of the Basel II Accord. Finally, we discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the proposed new framework.

In this section we focus primarily on U.S. history but also report on some recent European developments. Banking regulation has been intimately linked with the transformation of the banking industry over the twentieth century. The title of a paper by Berger, Kashyap, and Scalise (1995) summarizes well the financial revolution: “The transformation of the US banking Industry: What a long, strange trip it’s been.” We could extrapolate, saying: The transformation of the banking regulation: what a long strange trip it has been.

In the United States, the history of banking regulation is clearly tied to the decreasing level of capital detained by banks. In 1840 for instance, banks’ accounting value of equity represented 55 percent of loans. Since then this level has steadily decayed until the enforcement of the first Basel Accord.

The Federal Reserve System was created in 1914 and has helped to reduce bank failures by providing liquidity through central bank refinancing. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) was founded in 1933 and since then has offered an unconditional guarantee to most creditors of American banks. It has also restricted the level of interest rate that could be offered by banks on deposits.

Since the 1929–1939 crisis and before the first Basel Accord, a standard level of capital was required from banks. This level was defined independently from the risk borne by banks, either on balance sheet or off balance sheet. This situation did not lead to real difficulties as long as the business scope of banks was tightly controlled (in the United States, the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 separated commercial banking and investment banking, and the McFadden Act of 1927 prevented banks from establishing branches in multiple states).

In the 1980s, following the end of the Bretton Woods international monetary system in 1973, banks have expanded internationally. This evolution occurred in a period of increased level of inflation, massive development of new financial products, and ongoing deregulation. It has led to significant banking crises, such as the partial collapse of the savings and loans industry at the beginning of the 1990s in the United States. Banks had become more aggressive and expanded to new markets in which they had no experience. They also increased their exposure vis-à-vis emerging markets and sometimes adopted pricing policies that did not fully reflect the effective level of risk of their investments. In addition, most international banks did not increase their level of equity accordingly. At the same time disintermediation of the highest-quality credits (in particular through commercial paper issuance) has tilted the balance sheet of some banks toward more speculative investments. These radical changes left the banks in an open and competitive environment where the role of financial markets was ever increasing.

The last major change in the U.S. banking landscape has arisen from the Financial Services Act of 1999 that repealed the major provisions of the Glass-Steagall Act and has allowed banks to expand significantly their range of financial services in any type of business, including brokerage and insurance. All these evolutions have translated into radical changes in the financial industry: Banks have been involved in an increasing wave of mergers.

In parallel, the Basel Committee on Banking and Supervision was created in 1974 by the governors of the Group of Ten1 (G10) central banks. Its necessity was felt after several crises on forex markets as well as after bank failures such as the Herstatt Bank crisis in 1974. The committee does not possess any formal supranational supervisory authority, and its conclusions do not have legal force. Rather it formulates broad supervisory standards and guidelines and recommends statements of best practice in the expectation that individual authorities (local regulators) will take steps to implement them through detailed arrangements that are best suited to their own national systems.

At the end of the eighties and at the beginning of the nineties, regulators focused on reducing the level of bank insolvency. Capital has received a particular emphasis in this respect, as it has been considered altogether as a cushion in order to absorb potential losses, as an instrument to reduce moral hazard linked with the deposit insurance safety net, and as a way to protect depositors and insurers. The first Basel Accord of 1988 became applicable by 1992. It has been an important step in banking regulation. The objective was to strengthen and stabilize the whole international banking system, first of all by setting some standardized criteria for capital levels, but also by promoting a single homogeneous framework that would lead to fair competition among international banks. The main breakthrough of this regulatory scheme was to introduce a risk-based definition of capital.

National regulators have cooperated to implement the Basel rules and to provide a common and consistent regulatory platform. The first Basel Accord was translated as an American mandatory requirement in 1991 (Federal Deposit Insurance Improvement Act) and in Europe in 1993 (directive on the solvability ratio). The adaptation of the banking industry to this new regulation in the 1990s has shown its limits. As a result, in 1996 an amendment regarding market risk was adopted. It allows banks to use their own internal models on their trading books. This amendment has, however, created a split between the trading book and the banking book of banks. A high level of arbitrage between the two books has therefore emerged since then. In addition, regulators themselves have been able to identify some structural weaknesses: “While examination assessments of capital adequacy normally attempt to adjust reported capital ratios for shortfalls in loan loss reserves relative to expected future charge-offs, examiners’ tools are limited in their ability to deal effectively with credit risk—measured as uncertainty of future credit losses around their expected levels” (Federal Reserve, 1998).

The central criticism about the first Basel Accord is probably focused on its inability to evolve in accordance with financial practice, as Alan Greenspan pointed out in 1998 in the B.I.S. Review: “While no one is in favor of regulatory complexity, we should be aware that capital regulation will necessarily evolve over time as the banking and financial sectors themselves evolve.” From a practical standpoint, we can distinguish two periods in the history of regulation. The period until the mid-1990s was characterized by a rather rigid and standardized regulatory approach. Since the mid-1990s, market discipline and the recourse to internal models have been constantly progressing. The new Basel II Accord that should be applicable in 2006–2007 corresponds to an intermediary step in regulation. It pushes toward individualized solutions and focuses on self-discipline but falls short of allowing internal portfolio models as drivers for the calculation of regulatory capital.

Time will tell whether this new regulatory framework contains sufficient flexibility and adaptation potential to cope with the ongoing trend of innovation in the financial arena.

Borio (2003) suggests a distinction between “macro-prudential” and “micro-prudential” perspectives. In the former the focus is on safeguarding global financial stability by avoiding systemwide distress. In the latter the objective is to limit distress risk in each financial institution and thereby protect consumers and investors. The equivalence of the two approaches is often assumed, but it is not clear whether individual failures always entail systemic risk. This is particularly unclear when the trigger for a failure lies in idiosyncratic factors. This open question represents a fundamental issue regarding the justification of the heavy regulation procedures currently being developed for Basel II.

In what follows, we review the microeconomics of banking regulation and try to identify when systemic risk is at stake or not. Practically, we are going to review major contributions from the academic literature that have attempted to answer the following questions: Why regulate? Is regulation biasing the banking system? How should the regulator intervene? And how should rules be defined?

There is no real consensus on the intrinsic value of regulation. For Fama (1985) there should not be any difference regarding the treatment of a bank and an industrial firm. As a consequence there will be little rationale for a specific regulation that may bring noise to market equilibrium and generate misallocation of resources and lost growth opportunities. Regulation may, however, be considered acceptable if it enables us to minimize market imperfections such as imperfect information and monopolistic situations or to protect public good.

Four main motivations are generally mentioned to justify the existence of banking regulation2:

To protect banks’ depositors from a loss in case of bankruptcy. Depositors are small atomized creditors. They do not have access to sufficient information in order to monitor their bank properly (Dewatripont and Tirole, 1994).

To protect banks’ depositors from a loss in case of bankruptcy. Depositors are small atomized creditors. They do not have access to sufficient information in order to monitor their bank properly (Dewatripont and Tirole, 1994).

To ensure the reliability of a public good, i.e., money. Money corresponds not only to the currency but also to the distribution, payment, and settlement systems (Hoenig, 1997).

To ensure the reliability of a public good, i.e., money. Money corresponds not only to the currency but also to the distribution, payment, and settlement systems (Hoenig, 1997).

To avoid systemic risk arising from domino effects (Kaufman, 1994). This type of effect typically comes from a shock on a given financial institution that impacts gradually all the other financial institutions because of business links or reputation effect. The precise mechanism entails three steps: (1) contagion, and then (2) amplification, leading ultimately to (3) a macroeconomic cost that impacts the gross domestic product. In this respect the action of the Federal Reserve to protect the banking system against the adverse consequences of the collapse of the hedge fund LTCM characterizes such a preventive action. In contrast, the bankruptcies of the banks BCCI and Drexel Burnham Lambert show that when there is no real perceived contagion risk, the intervention of regulators may not be required.

To avoid systemic risk arising from domino effects (Kaufman, 1994). This type of effect typically comes from a shock on a given financial institution that impacts gradually all the other financial institutions because of business links or reputation effect. The precise mechanism entails three steps: (1) contagion, and then (2) amplification, leading ultimately to (3) a macroeconomic cost that impacts the gross domestic product. In this respect the action of the Federal Reserve to protect the banking system against the adverse consequences of the collapse of the hedge fund LTCM characterizes such a preventive action. In contrast, the bankruptcies of the banks BCCI and Drexel Burnham Lambert show that when there is no real perceived contagion risk, the intervention of regulators may not be required.

To maintain a high level of financial efficiency in the economy. The distress or insolvency of a major financial institution could have an impact on the industry and services in a region. In this respect Petersen and Rajan (1994) consider that the collapse of a bank could lead to a downturn in the industrial investment in a region. Other banks may not be in a position to quickly provide a substitute offer, given their lack of information on the firms impacted by the fall of their competitor.

To maintain a high level of financial efficiency in the economy. The distress or insolvency of a major financial institution could have an impact on the industry and services in a region. In this respect Petersen and Rajan (1994) consider that the collapse of a bank could lead to a downturn in the industrial investment in a region. Other banks may not be in a position to quickly provide a substitute offer, given their lack of information on the firms impacted by the fall of their competitor.

In the United States, depositors are protected by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. Most banks subscribe to it. Merton (1978) very early mentioned moral hazard issues linked with deposit insurance. Deposit insurance can indeed generate costly instability because it may provide incentive for banks to increase their risks. In case of insolvency, banks know they will not face major consequences vis-à-vis depositors. There have been several contributions about the cost of the insurance premium. Kane (1989) suggests that it should reflect the true risk of each bank. Merton and Bodie (1992) suggest several measures to minimize these effects, such as linking the value of the insurance premium to the risk level of the assets, setting a reserve requirement that should be transferred to the central bank; requiring an appropriate equity level, limiting the recourse to the lender of last resort, or restricting too large diversification. Chan, Greenbaum, and Thakor (1992) show that if the premium is calculated in an optimal way, moral hazard is then reduced.

Deposit insurance also carries another weakness. Given the safety net it provides, it suppresses the natural incentive for depositors to monitor their bank. Calomiris and Kahn (1991) and Peters (1994) show that depositors will withdraw their deposits when they receive signals that the bank has a risky behavior. This approach is very much linked with the topic of bank runs due to the diffusion of information. Peters (1994) suggests that a limited coverage of risk through deposit insurance is optimal because it still leaves room for monitoring by depositors.

When liquidity is offered by a lender of last resort to an insolvent bank without any specific requirement, the service provided is not different from deposit insurance (Bhattacharya, Boot, and Thakor, 1998). Rochet and Tirole (1996) indicate that governments behave like lenders of last resort when they provide liquidity to banks that are in difficulty or when they nationalize them. This intervention by states is inefficient, as it reduces the incentive for banks to monitor one another on the interbank market. The intervention is based on the too-big-to-fail doctrine. This means that when a financial institution is large, the risk of contagion may be so important that it leads a government to react and prevent such an event. In the wake of Bagehot (1873), Rochet and Tirole (1996) suggest that governments should intervene if and only if the distressed bank remains intrinsically viable though facing a sudden crisis. Acharya and Dreyfus (1989), Fries, Mella-Barral, and Perraudin (1997), and Mailath and Mester (1994) have tried to define criteria in order to decide whether a bank should be closed or saved.

Prudential rules focused on minimum capital requirements have been criticized. For Kahane (1977) they are inaccurate, and for Koehn and Santomero (1980) they lead to more risky behaviors. For Besanko and Kanatas (1993) and Besanko and Thakor (1993), initial shareholders become less important, and their incentive to manage the bank properly is reduced. According to this theory, the cost of capital for the bank implies an increase in interest rates charged to its clients and therefore a reduction in lending activity.

Regulation entails two specific actions: setting prudential rules and monitoring banks adequately. Optimal regulation has recently been defined as a choice—a menu—of different alternatives offered to banks. Whatever the choice made by banks, regulation aims at inducing them to reveal early private information about their risks and about the way they are managed. This increased transparency enables regulators and banks to anticipate crisis situations.

In order to discriminate among banks, three directions have been suggested:

Customizing the premium of the deposit insurance, based on risk. Chan, Greenbaum, and Thakor (1992) suggest that the premium of the deposit insurance should be calculated in order to factor in the risk held by banks without having to proceed to costly verification. Their suggestion is to play both on the deposit insurance premium cost and on a minimum capital requirement. They show that banks holding substantial risk would be ready to pay a high premium provided that the level of capital required remains low. Conversely, risk-averse banks will typically opt for a low premium cost and a high capital level.3

Customizing the premium of the deposit insurance, based on risk. Chan, Greenbaum, and Thakor (1992) suggest that the premium of the deposit insurance should be calculated in order to factor in the risk held by banks without having to proceed to costly verification. Their suggestion is to play both on the deposit insurance premium cost and on a minimum capital requirement. They show that banks holding substantial risk would be ready to pay a high premium provided that the level of capital required remains low. Conversely, risk-averse banks will typically opt for a low premium cost and a high capital level.3

Focusing on discriminating senior executives. Rochet (1992) focuses on the identification of the efficient or inefficient senior management of banks. He shows that the composition of the portfolio of a bank can reveal insight into how to categorize management with regard to efficiency.

Focusing on discriminating senior executives. Rochet (1992) focuses on the identification of the efficient or inefficient senior management of banks. He shows that the composition of the portfolio of a bank can reveal insight into how to categorize management with regard to efficiency.

Relying on the precommitment approach. Kupiec and O’Brien (1995a, 1995b, 1997) have centered their analysis on the level of trustworthiness that internal models for risk management can bring to regulators. Credibility stands at the center of their “pre-commitment approach.” According to this approach, banks should declare, using their own tools, what their maximum level of loss over 10 working days can be in the next 6 months. This underpins the definition by banks of a level of required capital. If banks go beyond this threshold, they are then penalized through fines, the release of information to markets, etc.

Relying on the precommitment approach. Kupiec and O’Brien (1995a, 1995b, 1997) have centered their analysis on the level of trustworthiness that internal models for risk management can bring to regulators. Credibility stands at the center of their “pre-commitment approach.” According to this approach, banks should declare, using their own tools, what their maximum level of loss over 10 working days can be in the next 6 months. This underpins the definition by banks of a level of required capital. If banks go beyond this threshold, they are then penalized through fines, the release of information to markets, etc.

Prescott (1997) distinguishes between what he considers to be the three ages of banking regulation:

A standardized approach corresponding to the Cooke ratio and its extensions.

A standardized approach corresponding to the Cooke ratio and its extensions.

An approach based on internal models to define the capital at risk.

An approach based on internal models to define the capital at risk.

An approach where the banks themselves choose the rules they are going to be judged on. This corresponds more or less to the precommitment approach. This approach does not mean a weak level of control. It has to be seen as a customized trade-off between obligations and penalties.

An approach where the banks themselves choose the rules they are going to be judged on. This corresponds more or less to the precommitment approach. This approach does not mean a weak level of control. It has to be seen as a customized trade-off between obligations and penalties.

It is widely accepted that risk increases during growth periods and bank failures tend to materialize during recessions. Two main reasons account for this. First, growth periods may lead to the underestimation of risk and to more lenient lending criteria, as described by Honohan (1997). Second, as we saw in Chapter 2, defaults tend to increase during downturn periods, thereby increasing the likelihood of bank failures.

In this respect, tracking systematic risk and providing incentive to diversify risk at a bank level is a sound reaction. It typically corresponds to the microprudential focus of the regulation described in Borio (2003). Understanding the sensitivity of the whole banking system to economic cycles remains, however, an element to be investigated in greater detail. The capability of any regulation framework to account and adjust for these cycles is currently under discussion, with an increasing literature on the potential procyclical effects of regulation. This shows that the macroprudential aspect of current bank regulation may not yet be fully dealt with.

The approach currently followed by regulators assumes that common methodologies will lead to a common understanding of risk and reduce major insolvency issues. In other words the new Basel II regulatory framework can be seen as the definition of an insolvency frontier that prevents any failure of banks at a microeconomic level. The underlying assumption is that microeconomic security will automatically generate macroeconomic stability.

There is, however, growing concern among the financial community that the criteria that define the conditions for macroeconomic stability may not yet be fully understood and included in the Basel II Accord. In particular, several concepts have recently emerged that have not yet found fully satisfactory answers, such as:

“Procyclicality” risk, as discussed above

“Procyclicality” risk, as discussed above

“Liquidity” risk linked with the banking portfolio4

“Liquidity” risk linked with the banking portfolio4

“Time horizon” for the evaluation of risk which may go beyond 1 year5

“Time horizon” for the evaluation of risk which may go beyond 1 year5

“Earning management” by banks and its related risk6

“Earning management” by banks and its related risk6

“Growing consolidation” among financial institutions by mergers, along with their impact on macrofinancial stability

“Growing consolidation” among financial institutions by mergers, along with their impact on macrofinancial stability

The main pending issue related to the previous discussion is that the cost-benefit structure of the current regulatory scheme may be found acceptable, looking from a microprudential standpoint, as it may indeed provide a robust insolvency frontier for each bank. It is still criticized, though, from a macroprudential standpoint since it may not provide sufficient specific remedy to the effect of macroeconomic instability on the financial system.

The cornerstone of the first Basel Accord is the Cooke ratio. This ratio is defined as the amount of capital divided by risk-weighted assets. This ratio has to exceed 8 percent. In the 1988 Basel Accord, there are only four risk buckets:

OECD sovereigns: 0 percent risk weight

OECD sovereigns: 0 percent risk weight

OECD banks and non-OECD sovereigns: 20 percent risk weight

OECD banks and non-OECD sovereigns: 20 percent risk weight

Mortgage loans: 50 percent risk weight

Mortgage loans: 50 percent risk weight

Corporates and non-OECD banks: 100 percent risk weight

Corporates and non-OECD banks: 100 percent risk weight

Risk-weighted assets are simply the amount lent multiplied by the risk weight. For instance, at least 8 percent of risk-weighted corporate assets must be held as capital by the bank. Let us consider $100 lent to a corporate. It has to be backed up by at least 8 percent × 100 percent × $100 = $8 of capital, while the same loan to an OECD bank only requires 8 percent × 20 percent × $100 = $1.6.

The accord was amended, later on, in order to integrate market risk. The great novelty with the 1996 amendment is that it has allowed banks to use their own internal model in order to measure market risk.7 In addition, this amendment has enabled banks to integrate off-balance sheet instruments such as securitization.

The accord has been praised for ensuring an internationally accepted minimum capital standard. Many shortcomings of the simple rule described above have, however, also been recognized. In particular:

There has not been any clear motivation for setting the level of capital requirement at 8 percent.

There has not been any clear motivation for setting the level of capital requirement at 8 percent.

The definition of the risk buckets does not reflect sufficiently the true level of risk of obligors (for example, all corporates are in the same bucket).

The definition of the risk buckets does not reflect sufficiently the true level of risk of obligors (for example, all corporates are in the same bucket).

The Cooke ratio may not be very informative about the effective level of insolvency risk of banks, given its static bias and its unsophisticated distinction among risks (no impact of seniority, no maturity effect, etc.).

The Cooke ratio may not be very informative about the effective level of insolvency risk of banks, given its static bias and its unsophisticated distinction among risks (no impact of seniority, no maturity effect, etc.).

The effect of diversification is not factored in.

The effect of diversification is not factored in.

Arbitrage between the banking and the trading books has increased extensively (with, for example, the dramatic development of credit derivatives).

Arbitrage between the banking and the trading books has increased extensively (with, for example, the dramatic development of credit derivatives).

This regulatory framework has also had an impact on accounting practices within banks, as it has provided some incentive to develop new financial instruments dedicated to regulatory purposes only.

One of the main motivations for Basel II was to escape from the “one-size-fits-all” setting of Basel I. Initially, the Basel Committee was considering a menu of three types of approaches to deal with credit risk (Santos, 2000):

The IRBA (internal ratings-based approach). In each bank a rating is allocated to any counterparty, and for each rating there is a corresponding probability of default.

The IRBA (internal ratings-based approach). In each bank a rating is allocated to any counterparty, and for each rating there is a corresponding probability of default.

The FMA (full models approach). Internal models developed by banks to measure credit risk are accepted following some due diligence by regulators.

The FMA (full models approach). Internal models developed by banks to measure credit risk are accepted following some due diligence by regulators.

The PCA (precommitment approach). Each bank provides ex ante its maximum loss at a given time horizon. A penalty is applied ex post if the effective loss exceeds the ex ante declaration.

The PCA (precommitment approach). Each bank provides ex ante its maximum loss at a given time horizon. A penalty is applied ex post if the effective loss exceeds the ex ante declaration.

There are shortcomings associated with each of these three approaches. For example, the IRBA will not account properly for diversification, as it will be accounted for in a stylized way only. The FMA would suppose that the portfolio methodologies used by banks have been tested over a significant period of time in order to demonstrate a sufficient level of reliability. The PCA may show some limitations if the risk of bankruptcy deters the regulator from penalizing noncredible banks appropriately.

In its January 2001 proposals, the Basel Committee stepped back and narrowed its focus to a simplified scheme. The main rationale for this move was probably that the degree of sophistication of banks was quite unequal, with an understanding of credit risk that was not sufficiently homogeneous.

It has, however, kept the idea of a menu with three options8 (see Figure 10-1):

FIGURE 10-1

Credit Risk Assessment in the Three Approaches to Basel II

A (revised) standardized approach derived from the 1988 Basel Accord. The main difference is that unlike in the first accord, the weight allocated to each facility depends on the creditworthiness of the obligor via external ratings.

A (revised) standardized approach derived from the 1988 Basel Accord. The main difference is that unlike in the first accord, the weight allocated to each facility depends on the creditworthiness of the obligor via external ratings.

An internal ratings-based (IRB) foundation approach where the bank calculates PDs using its internal rating system, but other inputs such as loss given default are obtained from external sources (the regulator).

An internal ratings-based (IRB) foundation approach where the bank calculates PDs using its internal rating system, but other inputs such as loss given default are obtained from external sources (the regulator).

An IRB advanced approach where the banks’ own estimates of input data are used exclusively (probabilities of default, loss given default, maturities).

An IRB advanced approach where the banks’ own estimates of input data are used exclusively (probabilities of default, loss given default, maturities).

Credit mitigation as well as asset securitization techniques are incorporated in all three approaches. A lot of emphasis has been put on the regulator to define precisely the treatment of collateral, credit derivatives, netting, and securitization. The application of these mitigation techniques sometimes is nonspecific to the rating approach selected.

Like the 1988 Basel Accord, the Basel II framework is, above all, targeting internationally active banks. It has to be applied on a consolidated basis, including all banking entities controlled by the group as well securities firms, other financial subsidiaries,9 and the holding companies within the banking group perimeter.

The Basel Committee recognizes that its main challenge is to deal with the complexity of the new risk-based rules. As a result, the clarification and simplification of the structure of the accord has been one of its core objectives. This effort is tangible when looking at the difference in the presentation of the IRB approach between the initial version dated January 2001 and the QIS 3 version as per late 2002 and the CP3 consultative paper in 2003. In order to minimize the effect of the complexity in the rules, the committee has tried to work in a cooperative manner with the industry to develop practical solutions to difficult issues and to draw ideas from leading industry practice.

The ultimate goals of the Basel Committee are precisely defined and announced:

Providing security and stability to the international financial system by keeping an appropriate level of capital within banks

Providing security and stability to the international financial system by keeping an appropriate level of capital within banks

Providing incentive for fair competition among banks

Providing incentive for fair competition among banks

Developing a wider approach to measure risks

Developing a wider approach to measure risks

Measuring in a better way the true level of risk within financial institutions

Measuring in a better way the true level of risk within financial institutions

Focusing on international banks

Focusing on international banks

The Basel Committee has defined in a precise way the conditions under which the accord should work.

First, the Basel Committee has provided a lot of documentation about the methodologies applying to the collection and use of quantitative data. In addition, its objective has been to complement the internal calculation of regulatory capital by two external monitoring actions: regulatory supervision and market discipline. In order to emphasize that these last two components are as important as the first one, the committee has described capital calculation, regulatory supervision, and market discipline as the three pillars of a sound regulation (see Figure 10-2).

FIGURE 10-2

The Three Pillars of Basel II

Pillar 1—minimum capital requirements. The objective is to determine the amount of capital required, given the level of credit risk in the bank portfolio.

Pillar 1—minimum capital requirements. The objective is to determine the amount of capital required, given the level of credit risk in the bank portfolio.

Pillar 2—supervisory review. The supervisory review enables early action from regulators and deters banks from using unreliable data. Regulators should also deal with issues such as procyclicality that may arise as a consequence of a higher risk sensitivity of capital measurement.

Pillar 2—supervisory review. The supervisory review enables early action from regulators and deters banks from using unreliable data. Regulators should also deal with issues such as procyclicality that may arise as a consequence of a higher risk sensitivity of capital measurement.

Pillar 3—market discipline. The disclosure of a bank vis-à-vis its competitors and financial markets is devised to enable external monitoring and a better identification of its risk profile by the financial community.

Pillar 3—market discipline. The disclosure of a bank vis-à-vis its competitors and financial markets is devised to enable external monitoring and a better identification of its risk profile by the financial community.

In what follows, we focus exclusively on credit risk, but the Basel Accord also incorporates market and operational risks. The general framework is described on Figure 10-3.

FIGURE 10-3

General Capital Adequacy Calculation

Under the standardized approach, the calculation of the risk-weighted assets defined in Figure 10-3 is split between the determination of risk weights and the size of the exposure.11 We detail first how risk weights depend on the creditworthiness of the underlying assets. We then focus on the calculation of the exposure, given the mitigation brought by various types of collateral and hedging tools.

Risk Weights and Probabilities of Default With this approach, a bank determines the probability of default of a counterparty based on accepted rating agencies’ ratings12 or export agencies’ scores when available. A standard weight applies to counterparties without any external creditworthiness reference.

The standard risk weight for assets is normally 100 percent. Some adjustment coefficients are, however, determined in order to reflect the true level of credit risk associated with each counterparty. Table 10-1 gives a comprehensive description of the risk weights, based on Standard & Poor’s rating scale.13

TABLE 10-1

Risk Weights under the Standardized Approach

This revised approach entails significant differences with the Cooke ratio of Basel I. The former approach considered in particular the difference between OECD and non-OECD countries as critical for sovereign and bank risk weights. With the new approach references to the OECD have been replaced with the rating of the institution, as shown in Tables 10-2 and 10-3 (recall that Greece and Poland are OECD members, while Chile, Kuwait, and Singapore are not).

TABLE 10-2

New Sovereign Risk Weights

TABLE 10-3

New Bank Risk Weights

Determination of the Exposure Taking into Account Credit Risk Mitigation Banks following the standardized approach will be able to adjust the exposure of each asset by taking into account the positive role played by guarantees, collateral, and hedging tools such as credit derivatives. The Basel II framework provides guidance to mitigate the negative impact of the volatility of the collateral due to price or exchange rate changes by offering precise and adequate haircut rules. The principles of credit risk mitigation (CRM) are summarized in Table 10-4.

TABLE 10-4

Treatment of Credit Risk Mitigants*

From a practical standpoint, there are two types of approaches to account for CRM—the simple approach and the comprehensive one:

Under the simple approach, one defines rules for changes in the risk weights, given the quality of the collateral, while leaving the exposure unchanged.

Under the simple approach, one defines rules for changes in the risk weights, given the quality of the collateral, while leaving the exposure unchanged.

Under the comprehensive approach, the risk weights remain unchanged, but the exposures are adjusted to account for the benefit of the collateral. The exposure adjustment supposes the definition of haircuts to adjust for the volatility generated by market movements on the value of both the asset and the collateral. Banks have the choice between a standard haircut and their own estimated haircut. Under both cases, the framework is similar; i.e., the exposure after mitigation is equal to the current value of the exposure augmented by a haircut, minus the value of the collateral, which is reduced by two haircuts—one related to its volatility and the second linked with currency risk when it exists.

Under the comprehensive approach, the risk weights remain unchanged, but the exposures are adjusted to account for the benefit of the collateral. The exposure adjustment supposes the definition of haircuts to adjust for the volatility generated by market movements on the value of both the asset and the collateral. Banks have the choice between a standard haircut and their own estimated haircut. Under both cases, the framework is similar; i.e., the exposure after mitigation is equal to the current value of the exposure augmented by a haircut, minus the value of the collateral, which is reduced by two haircuts—one related to its volatility and the second linked with currency risk when it exists.

Once a bank adopts an IRB approach, the bank is expected to apply that approach across the entire banking group. A phased rollout is, however, accepted in principle and has to be agreed upon by supervisors.

The appeal of the IRB approach for banks is that it may allow them to obtain a lower level of capital requirement than when using the standardized approach. This result will, though, be conditional on the quality of the assets embedded in their portfolio. In addition, the benefit of using the IRB approach is limited to 90 percent of the capital requirement of the previous year during the first year of implementation of the approach and to 80 percent in the second year.

The IRB approach exhibits a different treatment for each major asset class.14 The framework remains, however, quite standard. It is described below.

Calculation of Risk Weights Using Probabilities of Default, Loss Given Default, Exposure at Default, and Maturity Risk-weighted assets are given as  , where K corresponds to the capital requirement. Exposures at default, EAD, are precisely defined in the accord. Unlike in the standardized approach, collateral is not deducted from EAD.

, where K corresponds to the capital requirement. Exposures at default, EAD, are precisely defined in the accord. Unlike in the standardized approach, collateral is not deducted from EAD.

The capital requirement K is determined as the product of three constituents:

We will examine these three constituents, in turn, below.

The LGD factor has a considerable impact on the capital requirement K, as they are linearly related, as shown in Figure 10-4. Thus an increase in LGD raises capital requirements by a similar factor irrespective of the initial level of LGD.

FIGURE 10-4

LGD Factor in Basel II Calculation K

In the foundation IRB approach, LGD levels are predetermined. For example, senior claims on corporates, sovereigns, and banks will be assigned a 45 percent LGD, whereas subordinated claims will be assigned a 75 percent LGD. In addition, some collateral types, such as financial collateral or commercial and residential real estate, are eligible in order to reduce LGD levels.

In the foundation IRB approach, LGD levels are predetermined. For example, senior claims on corporates, sovereigns, and banks will be assigned a 45 percent LGD, whereas subordinated claims will be assigned a 75 percent LGD. In addition, some collateral types, such as financial collateral or commercial and residential real estate, are eligible in order to reduce LGD levels.

In the advanced IRB approach, banks will use their own internal estimates of LGD.

In the advanced IRB approach, banks will use their own internal estimates of LGD.

In the capital requirement equation (above), PD* corresponds to a function that integrates the effect of correlation. PD* can be seen as a stressed probability of default taking into account the specific correlation factor of the asset class.

Unlike for LGD, the function mapping the probability of default to the capital requirement is concave.16 As a consequence, at high levels of PDs (e.g., non-investment grade), the relative impact on capital requirements of an increase in the LGD term is stronger than for the PD term (see Figure 10-5).

FIGURE 10-5

PD Factor in Basel II Capital Calculation K

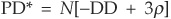

Basel II uses a simple one-factor porftolio model like those described in Chapters 5 and 6. Asset returns A are assumed to be normally distributed [A ∼ N(0,1)] and driven by a systematic factor C and an idiosyncratic factor ε, both also standard normally distributed:

where R is the factor loading.

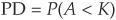

The probability of default corresponds to the probability that the asset return falls below some threshold K:

Under an average scenario (C = 0), we can calculate

where DD is the distance to default.

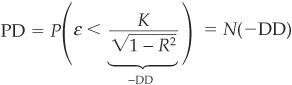

Basel considers a stressed scenario corresponding to the worst realization of the systematic factor at the 99.9 percent level. Under the standard normal distribution, this scenario corresponds to 3 standard deviations, i.e.,  . The stressed probability is

. The stressed probability is

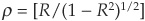

Using the normal distribution,  , where

, where  is the cumulative distribution function for a standard normal random variable and

is the cumulative distribution function for a standard normal random variable and  .

.

For various asset classes, the systematic factor loading R is adjusted. Figure 10-6 shows the different rules for R. The Basel II Accord determines different correlation levels for the various asset classes as a function of the PD of the obligor.

FIGURE 10-6

Proposed Correlations (R) for Various Asset Functions

In the capital requirement equation (above), f(.) is a function of M, the maturity of the loan, and b is a maturity adjustment factor depending on the probability of default. In the foundation IRB approach, the effective maturity of the facility is assumed to be 2.5 years. In the advanced IRB approach, the capital requirement formula is adjusted for the effective maturity of each instrument, depending on the level of PD.17 The impact of maturity is described in Figures 10-7 and 10-8.

FIGURE 10-7

Maturity Adjustment as a Function of the PD

FIGURE 10-8

Risk Weights for Large Entities for Various Maturities

Figure 10-7 shows that high-quality (investment-grade) facilities are more penalized by the maturity adjustment than low-quality ones. It implies that some of the relief granted in Basel II to the best credits is offset by the maturity adjustment.

There is a large development in the Basel II package regarding the treatment of securitization. Risk transfer through securitization is recognized as a risk mitigation tool both in the standardized and in the IRB approaches.

The Basel Committee distinguishes between traditional and synthetic securitization.18 The general criteria necessary to define when securitization enables capital relief are:

In the case of traditional securitization. The assets located in the vehicle are isolated from the bank transferring credit risk.

In the case of traditional securitization. The assets located in the vehicle are isolated from the bank transferring credit risk.

In the case of synthetic securitization. The underlying credit derivatives are complying with the requirements expressed previously in the Basel II package in Table 10-4.

In the case of synthetic securitization. The underlying credit derivatives are complying with the requirements expressed previously in the Basel II package in Table 10-4.

When banks are choosing the standardized approach, the various weights are incorporated as shown earlier in Table 10-1. The ratings provided by external agencies still play a major role, for both the standardized and the IRB approaches. In the IRB approach, the KIRB, which is the amount of required capital,19 becomes the central concept. Practically, there are two ways to calculate the amount of required economic capital: the ratings-based approach (RBA) and the supervisory formula approach. The former uses predetermined risk weights associated with the ratings of each tranche, and the latter is based on a parametric formula determined by the Basel Committee.

In addition to credit risk, the Basel II Accord focuses on operational risk. We have, however, deliberately chosen not to detail associated requirements, as they go beyond credit risk.

In the first part of his testimony to a congressional subcommittee on why a capital standard is necessary, Roger W. Ferguson, Jr., (2003) vice chairman of the Board of Governors of the U.S. Federal Reserve System, recognized that a change in the banking regulation was highly necessary. In this respect, the Basel II Accord corresponds to a clear improvement, compared with the Basel I framework. Ferguson testified:

Basel II presents an opportunity for supervisors to encourage these banks20 to push their management frontier forward. Of course, change is always difficult, and these new mechanisms are expensive. But a more risk-sensitive regulatory and capital system would provide stronger incentives to adopt best practice internal risk management.

Let me be clear. If we do not apply more risk-sensitive capital requirements to these very large institutions, the usefulness of capital adequacy regulation in constraining excessive risk-taking at these entities will continue to erode. Such an erosion would present U.S. bank supervisors with a highly undesirable choice. Either we would have to accept the increased risk instability in the banking system or we would be forced to adopt alternative—and more intrusive—approaches to the supervision and regulation of these institutions. (Ferguson, 2003)

Although there is a universal recognition that banking regulation should change rapidly, the consensus about what type of improvement is the most appropriate does not seem to be very strong yet.

Here we review five categories of criticisms that are commonly discussed regarding the new regulatory scheme:

1. The already growing gap between industry best practices and Pillar 1

2. The capability of Basel II to offer equal treatment to banks that operate in a competitive but diversified environment

3. The capability of Basel II to provide fair regulation that is not uniform, leading to gregarious behaviors of banks

4. The difference between regulatory constraint and risk management

5. The coherence between the new regulatory framework and the new accounting rules

The Basel II framework corresponds, as we have shown in the previous sections, to a significant technical improvement compared with Basel I. It reflects the evolution of the state-of-the-art practices in risk management over the past 10 years. If there is a broad acceptance that the present Basel II package reflects current best practices, there is still some concern for the future. Considering the current research in credit risk management, it is likely that the proposed framework will need to be updated in at least five directions in the next few years:

The inclusion of diversification and concentration in regulatory capital calculation in a customized manner and a more refined approach of dependencies

The inclusion of diversification and concentration in regulatory capital calculation in a customized manner and a more refined approach of dependencies

The refinement and replacement of the loan equivalent measure for the calculation of the exposure at default of contingent products

The refinement and replacement of the loan equivalent measure for the calculation of the exposure at default of contingent products

The replacement of VaR by coherent measures

The replacement of VaR by coherent measures

The measurement of liquidity risk

The measurement of liquidity risk

The value of linking the definition of an adequate time horizon for the calculation of the economic capital and the average maturity of the underlying portfolio of each bank.

The value of linking the definition of an adequate time horizon for the calculation of the economic capital and the average maturity of the underlying portfolio of each bank.

Let us consider an example of a shortcoming of the current regulatory framework:

Although correlation is included in Basel II, there is no real benefit associated with diversification under the IRB approach.21 Let us assume a portfolio composed of a single facility corresponding to a large corporate with an exposure of $100, an LGD of 45 percent, a maturity of 2.5 years, and a 1-year PD of 1 percent. It will receive the same regulatory capital, whatever the regulatory approach used, as a very diversified portfolio containing 100 facilities for various large corporates, each having a $1 exposure, an LGD of 45 percent, a maturity of 2.5 years, and a 1 percent PD.22

Moreover the general treatment of correlations in Basel II will probably have to be under review. For example, the Basel Committee has been openly challenged by some European governments regarding the treatment of SMEs, and as a result, the SME correlations were changed. We have seen in Chapter 5 that the link between PDs and correlations for large corporates is unclear. Equity-based models and empirical default correlations tend to exhibit correlations that increase in the level of PDs, but some intensity-based models report the opposite. For SMEs, empirical evidence is even more scarce. We therefore expect the Basel Committee to revise its correlation assumptions in a few years when more research is available on the topic.

Beyond this example, the challenge for the Basel Committee and for regulators will be to modify the technical framework corresponding to Pillar 1, subsequent to any substantial change in industry best practice. The good news is that this point is already widely discussed and accepted by regulators. In particular, Roger W. Ferguson, Jr., who was quoted earlier, notes: “Just as the methods of determining the inputs [EAD, PD, and LGD] can change as the state of the art changes, the formulas that translate the inputs into capital requirements can be modified as well by the regulators. Basel II can improve as knowledge improves” (Ferguson, 2003).

The proposed new regulatory framework ensures a common approach to risk and to required regulatory capital. There remains, however, some fear that this apparently very scientific and unbiased approach leads to unequal treatment among banks, for many different reasons:

Different perimeter. In the United States, Basel II treatment23 may eventually be applied to the 10 largest banks only, whereas in Europe the current consideration is rather for a much larger scope.

Different perimeter. In the United States, Basel II treatment23 may eventually be applied to the 10 largest banks only, whereas in Europe the current consideration is rather for a much larger scope.

Competitive bias I. The behavior of retail customers in each country can vary significantly, with some countries where individuals have a net positive savings position and others where there is a net negative one on average. Because of this, the retail business may not correspond to the same level of risk in each country, though its regulatory treatment will remain equal across countries.

Competitive bias I. The behavior of retail customers in each country can vary significantly, with some countries where individuals have a net positive savings position and others where there is a net negative one on average. Because of this, the retail business may not correspond to the same level of risk in each country, though its regulatory treatment will remain equal across countries.

Competitive bias II. Regarding residential and commercial real estate, the situation is identical in some countries where the effect of cycles is more pronounced than in others.

Competitive bias II. Regarding residential and commercial real estate, the situation is identical in some countries where the effect of cycles is more pronounced than in others.

Diversification. In some countries the integration of the banking activity with the insurance business is much more widespread than in others. Arbitrage between banking and insurance regulation may provide an advantage to the more integrated financial groups.

Diversification. In some countries the integration of the banking activity with the insurance business is much more widespread than in others. Arbitrage between banking and insurance regulation may provide an advantage to the more integrated financial groups.

Regulatory bias. Within the context of the Basel II rules, each regulator is entitled, under Pillar 2, to ask for an additional cushion on top of the level of capital defined by the calculation of Pillar 1. There is a concern that regulators may not behave in the same manner in all countries, expressing different levels of systemic risk aversion. In particular, regulators may decide to be more conservative in countries where liquidity is constrained because of weak financial markets.24

Regulatory bias. Within the context of the Basel II rules, each regulator is entitled, under Pillar 2, to ask for an additional cushion on top of the level of capital defined by the calculation of Pillar 1. There is a concern that regulators may not behave in the same manner in all countries, expressing different levels of systemic risk aversion. In particular, regulators may decide to be more conservative in countries where liquidity is constrained because of weak financial markets.24

Time will tell whether such fears are justified or not. Being able to be flexible enough to adapt the regulation, on a global basis, in order to cope with potential issues such as these will represent a real challenge for the Basel Committee.

This section illustrates the debate between those who favor the definition of a unique regulatory framework and those who think that regulation is more a matter of individual precommitment. The former, who think that there is no alternative but the definition of objective and precise regulatory guidelines for banks, will find what follows irrelevant. In particular, they will say that regulators have nothing to do with the strategy of each bank. The latter, who think that a one-size-fits-all view of any banking regulation can prove dangerous, will consider this section very important.

We will not enter this debate here but want to explain the main issue. We have seen in Chapters 6 and 7 that senior executives of banks have to manage both technical risk25 and business risk.26 Basel II typically focuses on technical risk only and ignores business risk that is linked with value creation. In particular, given the profile, the perception, and the expectations of the shareholders of a specific bank, the senior executives of that bank may decide to adopt a certain risk aversion profile. For instance, the shareholders of a regional, nondiversified bank will not have the same type of expectations as those of a geographically diversified universal bank. As a consequence, the senior executives of each of these banks will tend to set different hurdle rates for their business units and will also provide different guidelines regarding diversification requirements. In other words, for them technical risk management rules should arguably depend on business risk management principles. There is a natural trend to adjust risk management rules to the characteristics of the business.

By isolating technical risk management from business risk management, pro-precommitment supporters believe that regulators incur the risk of providing a strong incentive for gregarious behaviors. The experience of the nineties in the area of market risk has shown that the recourse to tools that adjust for risk in a similar way during crisis periods may lead to market overreaction and increased macroeconomic risk.

Should the new regulatory framework be considered the tool for internal risk management? With Basel I, banks have learned to separate regulatory requirements from internal risk management. The main difference between Basel I and Basel II is about costs. The cost of implementation of the new accord within each bank is indeed much larger than previously. As a result, senior executives of banks often would like to be able to merge the two risk approaches by using the Basel II scheme as their only monitoring tool for risk management.

Looking at the facts, the answer is, however, mixed. The positive aspect is that the vast data collection effort that is required by Basel II corresponds to a clear necessity for any type of bottom-up risk management approach. As the cost associated with Basel II is largely the consequence of data collection, there is no duplication of cost at stake in this respect. Regarding the modeling part of the Basel Accord, the perspective of the regulator and that of banks differ. The former tries to set a robust insolvency frontier, whereas the latter looks for tools that provide dynamic capital allocation and management rules. It thus does not seem very appropriate to rely on the Basel II framework only. The previous chapters of this book and the other sections of this chapter have constantly underscored these differences. The good news, however, is that the cost of adopting an alternative bottom-up methodology is not that large compared with the cost of data acquisition.

In 1998 Arthur Levitt, former chairman of the SEC, gave what is now known as “The Numbers Game” speech. He criticized the practice of manipulating accounting principles in order to meet analysts’ expectations. Eighteen months after, his comment was that “the zeal to project smoother earnings from year to year cast a pall over the quality of the underlying numbers . . . .” Since then, the failure of Enron, Worldcom, and others has shed a vivid light on this issue. Galai, Sulganik, and Wiener (2002) show how earnings smoothing and management can also be applicable to banks.

In order to reduce accounting bias, the International Accounting Standards Committee (IASC) has been working on a revision of its principles. In particular, IAS 39, “Financial Instruments: Recognition and Measurement,” was issued in early 1999. It is heading toward a wider use of fair values for financial instruments. As of today, only the trading book is measured on the basis of marked-to-market prices. The banking book is currently measured using historical prices, including related amortization. With IAS 39, there will be a strong incentive to shift the banking book to fair value measurement.27

IAS and Basel II will be applicable to banks roughly at the same time. There is concern that the uncoordinated implementation of the new accounting scheme and of the Basel II Accord will lead to a good deal of confusion. Advocates of Basel II claim that fair value pricing will introduce a lot of volatility in the balance sheet of the bank and at the same time duplicate the effort in terms of transparency. People who favor IAS claim to have solved risk management issues in an easy way, without having to use the complex Basel II framework. The debate is far from over.

In our view the IAS approach tries to tackle what the Basel II Accord has carefully avoided up to now: measuring liquidity risk. In principle, bringing liquidity risk to the debate is fine. From a practical perspective, it may, however, still be quite difficult to evaluate it in a homogeneous way. For instance, two banks holding the same asset may come with two different fair values, because of their own evaluation of the related liquidity premium or because of different trading experiences.

In our view the Basel II Accord should be seen as a starting point. Banks will have to move ahead, and this new framework is a clear incentive for them to make progress in the area of risk management.

The main question remains, however: Will the financial system be better protected against systemic risk?

Basel II acknowledges that relying only on models and regulators is insufficient. Pillar 3 (about transparency) is aimed at promoting self-regulation. Banks are still perceived as very opaque entities (much more so than corporate companies), and the development of off-balance-sheet instruments has further increased opacity. Up to now many banks have tried to minimize the cost of opacity by building a strong reputation. The recent difficulties that large U.S. banks have experienced related to internal conflicts of interest show that reputation may not be a sufficient answer to sustain high shareholder value. Market disclosure and transparency may soon become the most important pillar of Basel II if financial markets are sufficiently efficient at discriminating among banks based on their release of accurate information.