Chapters 2 to 5 detailed the three major drivers of portfolio credit risk: the probability of default extracted from qualitative or quantitative approaches, loss given default, and correlations. We have so far treated all these factors in isolation. This chapter brings these building blocks together to derive important indicators such as economic capital or portfolio loss measures.

We start the chapter by explaining why we need a credit risk portfolio model (CRPM). Next we look at the common architecture of the main commercial models and distinguish between an analytical approach and a simulation-based approach. We then turn our attention to the main part of this chapter: a review of five of the most popular models commercially available—CreditMetrics, CreditPortfolioView, Portfolio Risk Tracker, CreditRisk+, and Portfolio Manager—and a discussion of their relative strengths and weaknesses. After that, we focus on the most recent methodologies designed to obtain quick approximations based on analytical shortcuts (the saddle point method and the fast Fourier transform), and we discuss stress testing. Finally, we present risk-adjusted performance measures (RAPMs).

Most commercial models fit in a bottom-up approach to credit risk. The idea is to aggregate the credit risk of all individual instruments in a port-folio. The output is a portfolio credit risk measure that is not the sum of risks of individual positions thanks to the benefits of diversification.

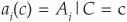

One of the main difficulties of dealing with credit-risky assets is that their profit and loss distributions are far from normal (see Figure 6-1). They are frequently characterized by a limited upside, as in the case for loans, but suffer from large potential downside because of high probabilities of large losses due to default (fat tail).

FIGURE 6-1

Typical Profit and Loss Profile for a Credit Portfolio

The development of portfolio management tools for market risk in the 1980s and early 1990s has enabled banks to better understand and control that risk. Since then, banks have worked actively to achieve a similar degree of sophistication in their credit risk management systems. This exercise was complicated by the nonnormality of credit loss distributions and the lack of reliable credit data for many asset classes. Four main reasons have driven banks to undertake the development or improvement of their credit portfolio tools:

Regulatory purposes. CRPMs are useful and will become part of the reporting in the Basel II context (see Chapter 10). Regulatory capital will be tied to the riskiness, maturity, and diversification of the bank’s portfolio.

Regulatory purposes. CRPMs are useful and will become part of the reporting in the Basel II context (see Chapter 10). Regulatory capital will be tied to the riskiness, maturity, and diversification of the bank’s portfolio.

Economic capital calculation and allocation. Beside regulatory capital, portfolio risk measures are used in banks to determine reserves based on economic capital calculations. The split of economic capital consumed by the various loans can also be used to set credit limits to counterparts or to select assets based on risk-return trade-offs, taking into account diversification benefits specific to the constitution of the bank portfolio.

Economic capital calculation and allocation. Beside regulatory capital, portfolio risk measures are used in banks to determine reserves based on economic capital calculations. The split of economic capital consumed by the various loans can also be used to set credit limits to counterparts or to select assets based on risk-return trade-offs, taking into account diversification benefits specific to the constitution of the bank portfolio.

Pricing purposes. Some financial instruments can be seen as options on the performance of a portfolio of assets. This is the case, for example, with collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) whose payoffs rely on cash flows generated by a pool of credit instruments. Measuring the risk of a portfolio of credit-risky assets can therefore also be useful both for pricing purposes and for the rating of such instruments by rating agencies (see Chapter 9).

Pricing purposes. Some financial instruments can be seen as options on the performance of a portfolio of assets. This is the case, for example, with collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) whose payoffs rely on cash flows generated by a pool of credit instruments. Measuring the risk of a portfolio of credit-risky assets can therefore also be useful both for pricing purposes and for the rating of such instruments by rating agencies (see Chapter 9).

Fund management. Asset managers can also benefit from a portfolio credit risk model for asset allocation. The selection of facilities to include in a portfolio or a fund is better determined when a global view on aggregate risk and diversification is available.

Fund management. Asset managers can also benefit from a portfolio credit risk model for asset allocation. The selection of facilities to include in a portfolio or a fund is better determined when a global view on aggregate risk and diversification is available.

A good credit risk portfolio model ideally should capture all facets of credit risk. The most obvious one is default risk (the probability of default and LGD) at the facility level and aggregated in the portfolio. Credit risk also encompasses changes in prices due to credit events. A CRPM therefore should, although in practice it rarely does, incorporate both downgrade and spread risk for the constituents of the portfolio. Finally, we have seen the crucial impact of correlations in the tails of loss distributions: A good portfolio model should also be in a position to reflect diversification or concentration effects accurately.

Here we describe the main architecture of portfolio models. They can be split into two categories: analytical models and simulation-based models.

Analytical models provide “exact” solutions to the loss distribution of credit assets, given some simplifying assumptions. The first step is to group homogeneous assets in subportfolios for which the homogeneity assumption allows us to derive analytical solutions for the loss distribution. Aggregate losses at the portfolio level are then obtained by a simple addition.

The main advantage of analytical models is that we can obtain results very quickly. Unfortunately, analytical solutions often come at the cost of many stringent assumptions on the drivers of default. The CreditRisk+ model reviewed below belongs to the analytical category.

Simulation-based models do not yield closed-form solutions for the portfolio loss distribution. The idea underlying this category of models is to approximate the true distribution by an empirical distribution generated by a large number of simulations (scenarios). This process enables gains in flexibility and can accommodate complex distributions for risk factors. The main drawback of this approach is that it is computer-intensive

Figure 6-2 describes the general process of a simulation-based model. The necessary inputs are assessments of probabilities of default, losses given default (mean and standard deviation), and asset correlations for all facilities. Using a Monte Carlo engine, we can use these inputs to simulate many scenarios for asset values which translate into correlated migrations. Conditional on terminal ratings at the end of the chosen horizon, values for each asset are computed and compared with their initial value, thereby providing a measure of profit or loss. The inputs and steps needed to implement a simulation-based model are explained in more detail in the CreditMetrics section that follows.

FIGURE 6-2

Simulation Framework

In this section we examine five credit risk portfolio models developed by practitioners: CreditMetrics, PortfolioManager, Portfolio Risk Tracker, CreditPortfolioView, and CreditRisk+. The last one belongs to the analytical class, whereas the first four are simulation-based.

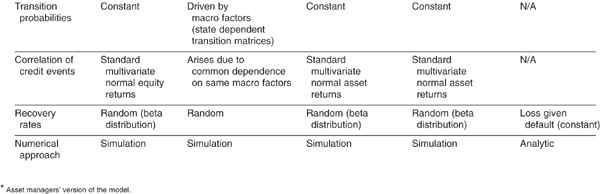

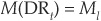

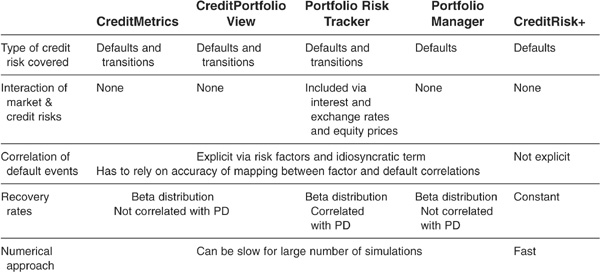

In a survey of 41 large international banks, Brannan, Mengle, Smithson, and Zmiewski (2002) report that more than 80 percent of banks use one of the products listed above as their credit portfolio risk model. Table 6-1 displays the various features of the models: the credit events captured by the models (defaults, transitions, and changes in spreads), the factors driving risk, the type of transition matrices used, the way that correlation is embedded, the specification adopted for LGD, as well as the category of model (analytical versus simulation-based).

TABLE 6-1

Comparative Structure of the Main Models

CreditMetrics is the credit risk portfolio tool of RiskMetrics. It is a one-period rating-based model enabling the user to calculate credit value at risk via the simulation of multiple normally distributed risk factors. We review in detail below the various steps leading to the calculation of portfolio losses. A more exhausitive description of the model can be found in the technical documents (JP Morgan, 1997). These documents also discuss the important issues of exposure measurement for nonstandard instruments such as derivatives.

Most inputs for credit risk portfolio models (PDs, LGDs, and correlations) have been studied at length in Chapters 2 to 5. We just briefly review them here and refer the reader to relevant chapters for more details.

CreditMetrics relies on many different inputs1:

PDs and transition probabilities

PDs and transition probabilities

Mean and standard deviation of recovery rates per industry and seniority

Mean and standard deviation of recovery rates per industry and seniority

Factor correlations and how each obligor is related to them (factor loadings)

Factor correlations and how each obligor is related to them (factor loadings)

Riskless yield curve

Riskless yield curve

Risky yield curves per rating class

Risky yield curves per rating class

Individual credit exposure profiles

Individual credit exposure profiles

Before reviewing the calculation methodology, we first spend some time discussing the various inputs.

PDs and Transition Probabilities CreditMetrics is a rating-based model. Each exposure is assigned a rating (e.g., BBB). A horizon-specific probability of transition is associated with every rating category. It can be obtained from transition matrices (see Chapter 2).

Each obligor is matched with a corresponding distribution of asset returns. This distribution of asset returns is then “sliced” (Figure 6-3) such that each tranche corresponds to the probability of migration from the initial rating (BBB in this example) to another rating category. The largest area is, of course, that of BBB, because an obligor is most likely to remain in its rating class over a (short) horizon. Thresholds delimiting the various classes can be obtained by inverting the cumulative normal distribution.

FIGURE 6-3

Splitting the Asset Return Distribution on Rating Buckets

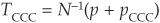

For example, the default threshold is obtained as  , where p is the probability of default of a BBB bond over the horizon and N−1(.) is the inverse of the cumulative normal distribution. The threshold delimiting the CCC and B classes is calculated as

, where p is the probability of default of a BBB bond over the horizon and N−1(.) is the inverse of the cumulative normal distribution. The threshold delimiting the CCC and B classes is calculated as

where pCCC is the probability of migrating to CCC, etc.

LGD Data CreditMetrics draws random beta-distributed recovery rates and assigns the random values to defaulted facilities. Recovery rates on various defaulted counterparts are assumed not to be correlated with one another nor with probabilities of default or other risk factors in the model. Appendix 6A shows how to draw random numbers from an arbitrary distribution.

The beta distribution is specific to a given industry, country, and seniority level. Figure 6-4 is an example of the beta distribution fitted to the mean and volatility of recovery rates in the “machinery” sector across seniorities using U.S. data from Altman and Kishore (1996).

FIGURE 6-4

Density of Recovery Rate Calibrated to “Machinery” Sector

Factor and Asset Correlations Several approaches can be employed to simulate correlated asset returns. The most straightforward is to simulate them directly by assuming a joint distribution function and calculating a correlation matrix for all assets. This can be done when the number of lines N in the portfolio is small but becomes intractable for realistic portfolio sizes. The size of the correlation matrix is indeed N × N.

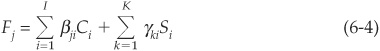

The traditional approach, employed by CreditMetrics, is to reduce the dimensionality of the problem by assuming that a limited number  of factors Fi drive the asset returns. Let Aj denote the asset return for firm j at the chosen horizon:

of factors Fi drive the asset returns. Let Aj denote the asset return for firm j at the chosen horizon:

Systematic factors2 Fi and the idiosyncratic term εj follow normal distributions, and so does Aj.

The CreditMetrics model thus requires input of the correlation matrix of the factors Fi as well as the variance of the idiosyncratic terms. It also requires factor loadings αij which reflect the sensitivity of a given obligor j to the various factors i.

An example of how to calculate the correlation between two firms’ asset returns and their default correlation is given in Appendix 6B.

CreditMetrics considers losses arising both from defaults and from migration. Transition losses are more complex to incorporate in a model than default losses. They require the computation of the future values of all instruments in the portfolio conditional on all possible migrations, as will be shown below.

Future expected values for debt instruments can be computed from the forward interest rate curves. An important input for that purpose is therefore a collection of forward curves (Figure 6-5) for all rating categories.

FIGURE 6-5

U.S. Industrial Bond Yield Curves (March 11, 2002)

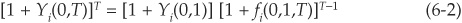

From the yield curves in Figure 6-5, one can extract forward rates per class of risk at the horizon of the model, typically 1 year. Let Yi(0,T) denote the yield at time 0 of a T-maturity zero-coupon bond in rating class i. Forward rates 1 year ahead fi(0,1,T) are obtained using the following relationship:

Equation (6-2) means that the return obtained from an investment at the rate Yi at time 0 for T years should be equal to an investment for 1 year reinvested for T–1 years at an agreed-upon rate at time 0. The agreed rate is the 1-year forward rate for rating category i: fi(0,1,T).

Exposures Most of the inputs discussed so far are not specific to a given bank’s portfolio. Obviously the most important input in the model is the identification of the instruments that belong to the portfolio. This comprises the size of each exposure, their rating, their sensitivity to the factors (factor loadings were discussed above), etc.

For plain vanilla loans the definition of the exposure is quite simple, but for optional instruments or swaps the exposure is not constant but depends, for example, on the evolution of interest rates. CreditMetrics assumes that a calculation of the average exposure has been performed elsewhere by the user of the model. The use of such “loan-equivalent” approximations is not fully satisfactory.

Once the user has collected all the necessary input variables (step 1), CreditMetrics can start calculating portfolio losses. As a ratings-based model, the primary purpose of the simulation engine is to generate migration events with the appropriate correlation structure.

Figure 6-6 illustrates the impact of asset correlations on the joint migration of obligors, assuming that there are two nondefault states (investment grade, or IG, and non-investment grade, or NIG) and an absorbing default state D.

FIGURE 6-6

Probabilities of Joint Migrations for Various Levels of Asset Correlation ρ

The experiment uses a one-factor model such as that described in Chapter 5, Equation (5-30). Similar results would be obtained in the multi-factor setup described in Equation (6-1). The tables are bivariate transition matrices for various levels of asset correlation ρ under the assumption of joint normality of asset returns and using aggregate probabilities of transition extracted from CreditPro.3 In order to reduce the size of the tables, we have assumed that the pair IG/NIG is identical from a portfolio point of view to the pair NIG/IG. Thus each bivariate matrix is 6 x 6 instead of 9 x 9.

Taking, for example, the case of two non-investment-grade obligors (line NIG/NIG), we can observe that as the correlation increases, the joint default probability (as well as the joint probability of upgrades) increases significantly.

Multivariate transition probabilities cannot be computed for portfolios with reasonable numbers of lines. In a standard rating system with 8 categories, a portfolio with N counterparts would imply an 8N × 8N transition matrix that soon becomes intractable.

CreditMetrics simulates realizations of the factors Fi and the idiosyncratic components εj [Equation (6-1)]. Given that firms all depend on the same factors, their asset returns are correlated and their migration events also exhibit co-movement.

Joint downgrades for two obligors 1 and 2 will occur when the simulations return a low realization for both asset returns A1 and A2. This will be more likely when these asset returns are highly correlated than in the independent case.

In step 2, CreditMetrics simulates all the terminal ratings of the obligors in the portfolios. Step 3 calculates the profits or losses arising from these transitions including defaults. For all defaulted assets, a random value for the recovery rate is drawn from the beta distribution, with mean and variance corresponding to the issuer’s industry and seniority. For “surviving” obligors, the terminal values of the assets are calculated using the forward curves as observed at the time of the calculations.

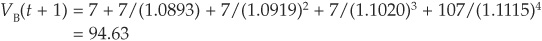

Measuring “Marked-to-Model” Losses: Example for a Straight Bond Consider a 5-year straight bond with a current rating of BBB and an annual coupon of 7 percent. We assume that a coupon has just been paid, so that the first cash flow will be paid in exactly 1 year. We have extracted the 1-year forward rates for all rating classes from AAA to CCC using Equation (6-2). Some of the rates are reported in Table 6-2.

From the forward curves computed in Table 6-2, we can calculate the forward values of the bond at our credit horizon (assumed to be 1 year) conditional on the bond terminating in a given rating. At the end of the horizon, the bond will have only 4 years left to maturity.

TABLE 6-2

1-Year Forward Rates

If it does not default, the bond will have a rating of AAA, AA, …, or CCC.

For example, if the obligor is upgraded to A, its forward price will be

However, if it is downgraded to B, the forward price will be

The forward price must be computed for all seven possible terminal ratings. Hence for each asset in the portfolio, CreditMetrics calculates all possible terminal values.

For each realization of risk factors Fi, we have calculated in step 2 the terminal rating of each security. Using the calculation described in step 3, we know what the forward prices of the facilities are, conditional on their terminal ratings.

Step 4 consists of summing up all forward values of the facilities and comparing the discounted sum (terminal value of the portfolio) with the current value of the portfolio. For each simulation run, we obtain a realization of credit profit and loss conditional on the specific value of the risk factors.

The above procedure is repeated a very large number of times, e.g., 1 million times, to obtain an entire distribution of portfolio losses. The distribution can then be used to calculate value at risk, expected shortfall, or any other risk statistic.

KMV’s Portfolio Manager is very similar to CreditMetrics. However, unlike CreditMetrics, it is a one-factor model focusing on default losses only. Bohn and Kealhofer (2001) provide an introduction to this model.

The main difference between Portfolio Manager and a simple one-factor version of CreditMetrics lies in the inputs for Portfolio Manager. We first briefly explore the basic structure of the model (which is identical to the CreditMetrics setup) and then discuss the necessary inputs.

The Portfolio Manager model is based on the multivariate normal distribution: Asset values for all firms are assumed to have normally distributed returns.4 Just as in CreditMetrics, when asset returns are low, the firm defaults. Transitions to other ratings are ignored.

The model therefore consists of:

1. Drawing many replications of the multivariate normal distribution

2. For each run of simulations, recording which firms default

3. Summing up the losses assuming beta-distributed loss given default

4. Calculating portfolio loss distribution and VaR

Since the model relies on the normal distribution, only two types of inputs are necessary: the probabilities of default for all obligors at the chosen horizon and asset correlations.

Instead of using probabilities of default extracted from the rating category of the debt issuer (as in CreditMetrics), Portfolio Manager relies on expected default frequencies (EDFs). EDFs are probabilities of default extracted from a Merton-type model of credit risk (see Chapter 3).

The first input in the model is therefore a set of EDFs. Given that Portfolio Manager is a one-factor model, correlations are driven by only one-factor loading. The general setup can be written as

The careful reader will have noticed that the factor also has subscript j, which means that it is specifically built for firm j. More specifically, it is obtained as

Ci are the indexes for the countries to which the firm is exposed, and Si are the sectors in which the firm operates.5

Equation (6-3) can be estimated from a time series of asset values. The R2 of the regression determines the balance between systematic and unsystematic risks and therefore the correlation between asset values.

The user of the model can override the R2 calculated this way and choose to fix it arbitrarily without any reference to a composite index. This flexibility is one of the rare degrees of freedom available to the user in this model. The remainder of the model is identical to CreditMetrics, and the reader can refer to the previous section for details on the calculations in a CreditMetrics-type framework.

Portfolio Risk Tracker (PRT) is Standard & Poor’s rating-based model. While the two products we have discussed so far are static (i.e., they focus exclusively on realizations of risk factors at a chosen horizon), PRT is dynamic. When choosing a 5-year horizon for example, risk factors are simulated at the end of each of the 5 years before the horizon. This allows Portfolio Risk Tracker to tackle products such as credit derivatives and CDOs in the calculation of credit value at risk. Unlike CreditMetrics and Portfolio Manager, PRT includes stochastic interest rates and is therefore able to deal with floating-rate notes and other interest rate–sensitive instruments, without having to rely on loan equivalence. Details of the methodology can be found in de Servigny, Peretyatkin, Perraudin, and Renault (2003).

Portfolio Risk Tracker also includes stochastic spreads,6 which makes it the only model out of the five discussed in this section to capture the three sources of credit risk: defaults, transitions, and changes in spreads.

Additional novelties embedded in this product include (among others):

The possibility to choose between correlation matrices extracted from spreads, equities, or empirical default correlations

The possibility to choose between correlation matrices extracted from spreads, equities, or empirical default correlations

The modeling of sovereign ceilings (the rating of corporates is capped at the level of the sovereign), which enables contagions in specific countries

The modeling of sovereign ceilings (the rating of corporates is capped at the level of the sovereign), which enables contagions in specific countries

The modeling of the correlation between PD and LGD (see Chapter 4)

The modeling of the correlation between PD and LGD (see Chapter 4)

The possibility to include equities, Treasury bonds, and interest rate options

The possibility to include equities, Treasury bonds, and interest rate options

Figure 6-7 is an example of the loss distribution computed with PRT. It clearly displays the asymmetric and fat-tailed shape of credit losses.

FIGURE 6-7

Distribution of Terminal Portfolio Value, Combining Market and Credit Risk

The main difference between CreditPortfolioView (CPV) and the three models presented above is that it explicitly makes transition matrices dependent on the economic cycle. Default and migration rates in a given country and industry at the chosen horizon are conditional on the future values of macroeconomic variables. This idea is intuitive and supported by empirical evidence (see Chapter 2). Macroeconomic variables are the key drivers of default rates through time. Figure 6-8 illustrates this statement using U.S. data: Industrial production changes are clearly reflected in fluctuations in probabilities of default (the survival probability is defined as 1 minus the annual default rate across all industries).

FIGURE 6-8

Survival Probability and Industrial Production Growth

CPV estimates an econometric model for a macroeconomic index which drives sector default rates. Simulated default rates subsequently determine which transition matrix (expansion or recession) is used over the next time step. By simulating random paths for the macro index at a given horizon, the model enables the user to approximate a distribution of portfolio losses. The main references for this model are three works by Wilson (1997a, 1997b, 1997c).

Any macroeconomic variable can be used as the driver of default rates. The choice is left to the user, who may decide (or preferably test) what factors are the most relevant to explain changes in default rates. The set of variables may include:

GDP or industrial production growth

GDP or industrial production growth

Interest rates

Interest rates

Exchange rates

Exchange rates

Savings rate

Savings rate

Unemployment rate

Unemployment rate

The explanatory variables above are easily available from public sources such as central banks or national statistics bureaus. The explained variables are the default rates per industry and country. They are available from rating agencies for long time series in the United States but not always in the rest of the world. Bankruptcy rates (often at the country level) are sometimes available to compensate for missing information in regions where the rated universe is too small or the time-series history too short.

Other necessary inputs are, as usual, details about the specific exposures included in the portfolio as well as transition matrices and recovery rate statistics.

In a given country and industrial sector, CPV proceeds in three steps to calculate the default rate.

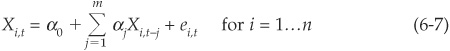

Step one first makes an assumption about the dynamics of the n selected macroeconomic variables Xi that will enter into the macroeconomic index. They are chosen to follow autoregressive processes so that the value at time t of variable Xi is given by

Step one first makes an assumption about the dynamics of the n selected macroeconomic variables Xi that will enter into the macroeconomic index. They are chosen to follow autoregressive processes so that the value at time t of variable Xi is given by

where ei,t are identically independently distributed (i.i.d) normal error terms that can be correlated across variables. The number of lags (m) to include should be determined by likelihood ratio tests, although CPV uses two lags for all variables. The parameters are estimated, and the residual covariance matrix is saved.

Second, the macroeconomic variables are aggregated into sector indexes

Second, the macroeconomic variables are aggregated into sector indexes  according to the following specification:

according to the following specification:

where  are also i.i.d. normal disturbance terms and s denotes the sector. Each index reflects the health of the economy of a given sector. The macroeconomic indexes above take values in (−∞, + ∞,).

are also i.i.d. normal disturbance terms and s denotes the sector. Each index reflects the health of the economy of a given sector. The macroeconomic indexes above take values in (−∞, + ∞,).

The final step applies the logistic transformation to Y in order to obtain a default rate (DR) that lies in [0,1]:

The final step applies the logistic transformation to Y in order to obtain a default rate (DR) that lies in [0,1]:

Thus as  , DR

, DR  , 1 and as

, 1 and as  ,

,  .

.

The estimation of the parameters and residuals in Equations (6-7) and (6-8) can be performed using standard econometric techniques. In order to estimate Equation (6-8) one first needs to invert Equation (6-9) to obtain implied values of the index from observed default rates in each sector. For a given sector s, the index is obtained from

Let us pause and summarize the process. We want to estimate the macroeconomic drivers of the default rate  in a given sector s. Intuitively we want to link this default rate to a macroeconomic index that would incorporate all macro variables. This index is

in a given sector s. Intuitively we want to link this default rate to a macroeconomic index that would incorporate all macro variables. This index is  and determines the default rate via Equation (6-9). The index is a weighted sum of individual macro variables Xi,t [Equation (6-8)] that are assumed to follow a simple autoregressive process [Equation (6-7)].

and determines the default rate via Equation (6-9). The index is a weighted sum of individual macro variables Xi,t [Equation (6-8)] that are assumed to follow a simple autoregressive process [Equation (6-7)].

The previous section consisted of specifying the dynamics of default rates and estimating the parameters (α, β) on historical data. We now move on to the main goal of the CPV model, which is to use the dynamics calibrated on past default rates to simulate future possible realizations of default rates at various horizons.

Future default rates will be linked to future realizations of macro variables. The simulation engine generates random variables that are used to simulate paths for the macro variables and therefore for the credit index and ultimately for the probabilities of default per industry.

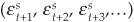

1. The first step is to generate a large number K of vectors of correlated random variables (ei,t+1, ei,t+2, ei,t+3,…) and  where the length is the time corresponding to the chosen horizon. For example, if the chosen horizon is 1 year and Equations (6-7) and (6-8) have been estimated on quarterly data, the simulated paths should have four time steps. In order to simulate these paths, we need to draw correlated normal random variables with a covariance matrix chosen to correspond to that estimated in the previous section (see Appendix 6A for more information on simulation).

where the length is the time corresponding to the chosen horizon. For example, if the chosen horizon is 1 year and Equations (6-7) and (6-8) have been estimated on quarterly data, the simulated paths should have four time steps. In order to simulate these paths, we need to draw correlated normal random variables with a covariance matrix chosen to correspond to that estimated in the previous section (see Appendix 6A for more information on simulation).

2. These random values are then plugged into Equations (6-7) and (6-8) to obtain K realizations of the macroeconomic index.

3. Then the macroeconomic index realizations are transformed into K realizations of the default rate P (default) using Equation (6-9).

4. For each simulation run, if P (default) is below its long-term average, the sector is assumed to be in expansion and we would choose an expansion transition matrix. But if P (default) is above its average, we would choose a recession matrix for the sector.

In CPV, the correlation arises across sectors due to the fact that sector default probabilities all depend on the same macro factors.

We consider Mh and Ml, the transition matrices associated with high states (growth) and low states (recessions), respectively, in the economic cycle. The significant difference between those two matrices is discussed, for example, in Bangia, Diebold, Kronimus, Schagen, and Schuermann (2002). Naturally, downgrade and default probabilities are higher in low states than in high states.

In order to calculate the N-period transition matrix necessary to calculate portfolio losses N years ahead (assuming a yearly time step), CPV starts by simulating many realizations of the default rate for the N periods as described above. For each path and each year, the 1-year transition matrix is taken to be Mh if the default rate is below its unconditional mean and Ml if it is above.

Then, assuming that transition matrices are Markovian and denoting as DR* the historical average default rate, the multiperiod transition matrix is calculated as

where the function M (.) is such that  if

if  and

and  if

if  .

.

When we simulate a large number of replications of Equation (6-11) we can approximate the distribution of default rates for any rating class as well as the distribution of migration probabilities from any initial to any terminal rating. Combining cumulative default rates with an assumption about LGD (not specified within the model) as well as each exposure characteristic, CPV can approximate portfolio loss distributions.

The main advantage of CPV is that it relies on inputs that are relatively easy to obtain. Its main weakness is that it models aggregate default rates and not obligor-specific default probability.

CreditRisk+ is one of the rare examples of an analytical commercial model. It is a modified version of a proprietary model developed by Credit Suisse Financial Products (CSFP) to set its loan loss provisions. A complete description of the model is available in Credit Suisse Financial Products (1997).

CreditRisk+ follows an actuarial approach to credit risk and only captures default events. Changes in prices, spreads, and migrations are ignored. This model is therefore more appropriate for investors choosing buy-and-hold strategies.

The issue is not whether specific securities in the portfolio default, but rather what proportion of obligors will default in a sector and will default at the portfolio level. Facilities are grouped in homogeneous buckets with identical loss given default. The default rate in a given sector is assumed to be stochastic.

The required inputs are

Individual credit exposure profiles

Individual credit exposure profiles

Yearly default rates per industry or category of assets

Yearly default rates per industry or category of assets

Default rate volatilities

Default rate volatilities

An estimate of recovery rates (assumed constant in this model)

An estimate of recovery rates (assumed constant in this model)

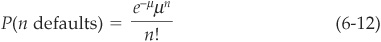

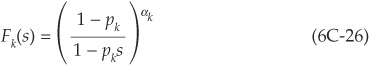

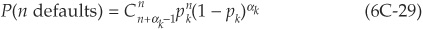

Assuming that probabilities of default are small and time-homogeneous, the probability of default in a given sector can be approximated by a Poisson distribution with mean µ such that the probability of n defaults is

CreditRisk+ assumes that the mean default rate µ is itself stochastic and gamma-distributed. Introducing the probability generating function (PGF), it is possible to express the PGF of the default losses in each bucket and to aggregate them into the probability generating function of portfolio losses.

An algorithm then allows us to derive the distribution of portfolio losses from the PGF, thereby providing a fast analytical solution to the calculation of economic capital and other risk measures.

Factor correlations are not modeled in CreditRisk+. In that model the factors are the default rates in the buckets, which are assumed to be independent. CSFP argues that there is not enough data to estimate default correlations with reasonable accuracy and that the CreditRisk+ model captures fat tails in loss distributions (similar to those generated using correlated factors) through their assumption of stochastic default rates.

For a detailed description of the model, see Appendix 6D.

We have discussed the features of five of the most well-known commercial models of credit portfolio risk. This section focuses on comparing the relative merits of competing approaches. For brevity, we will use the following acronyms: CM (CreditMetrics), PRT (Portfolio Risk Tracker), CPV (CreditPortfolioView), PM (Portfolio Manager), and CR+ (CreditRisk+).

The first four models are simulation-based and therefore much more time-consuming than CR+ for large portfolios. This is the main advantage of CR+ over its competitors. Unfortunately it comes at the cost of several disadvantages.

First CR+ is a default-only model, as is PM. This means that portfolio losses due to migrations are ignored. For a portfolio of investment-grade bonds, default risk itself is quite limited, and a substantial share of portfolio losses is due to downgrades. Ignoring this substantially underestimates the total credit risk. Similarly, spread risk is not taken into account by any product but PRT.

CR+ assumes constant LGDs and does not specifically account for correlations (second-order effects are incorporated in CR+ via the randomness of default rates). Other models use beta-distributed LGDs and incorporate correlations of assets, factors, or macroeconomic variables. Table 6-3 summarizes some strengths and weaknesses of the main commercial models.

TABLE 6-3

Strengths and Weaknesses of Main Models

A criticism often directed toward some off-the-shelf products is their lack of transparency. This lack of transparency, along with a lack of flexibility, has led first-tier banks to develop their own internal models over which they have total control. Some of these models are similar to those presented above, while others rely on alternative approaches, to which we now turn.

In this section we review two recent alternatives to standard portfolio models. Their primary goals are to achieve fast computation of portfolio losses while providing more flexibility than CreditRisk+. The first approach relies on saddle point methods, while the second one combines fast Fourier transforms and Monte Carlo.

We have stressed above that on the one hand there are “exact” and fast models of portfolio credit risk that enable us to calculate portfolio losses instantly but at the cost of stringent assumptions about the distribution of factors, and on the other hand there are simulated approaches that can accommodate more complex distributions but must rely on time-consuming simulations. Saddle point methods are an alternative way to approximate the true distribution without the use of simulations. They are very fast and particularly accurate in the tails of the distributions, which are of specific interest to risk managers.

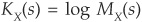

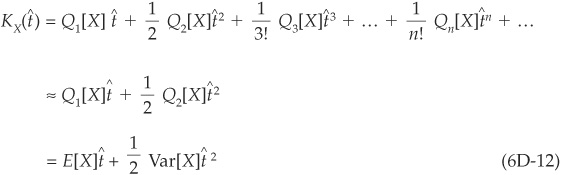

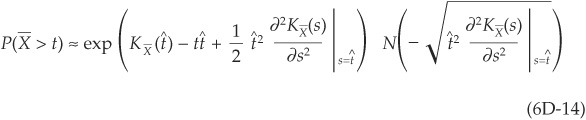

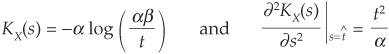

Saddle point methods are based on the observation that although some combinations of distribution functions may be impossible to calculate analytically, their moment generating function or cumulant generating function (CGF) may remain tractable. For example, assume that we have a portfolio of two assets whose returns are both distributed according to some distribution. The portfolio returns thus correspond to a weighted sum of this distribution, which may not be easy to calculate. However, the CGF may be much easier to calculate.

An approximate but fairly accurate mapping of the CGF to the distribution function is then performed. It allows the risk manager to obtain fast approximations of the tail of its portfolio loss distributions. A detailed description of the approach is provided in Appendix 6D.

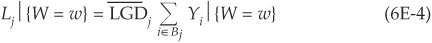

In a recent paper Merino and Nyfeler (2002) propose a new technique combining fast Fourier transforms and Monte Carlo simulations that is both fast and accurate over the entire portfolio loss distribution. The algorithm is applied to the class of conditionally independent models introduced in Chapter 5 and relies on several results already used in the derivation of CreditRisk+. This approach is described in Appendix 6E.

So far we have dealt with the estimation of portfolio loss distributions. We now consider the most commonly used indicators of portfolio risk. We then explain the two usual ways to split economic capital between facilities in a portfolio. Finally we review risk-adjusted return on capital (RAROC).

The output of a risk model is generally a distribution of losses, i.e., the levels of possible losses with their associated probabilities. This distribution captures all the information about the losses that can be incurred on a specific portfolio at a specific horizon. In order to make decisions, we need to transform the distribution into some synthetic measures of risk which enable the risk manager to communicate with the board of the bank or with external counterparts such as clients or regulators. Some of the most widely used measures of risk are expected and unexpected losses, value at risk, economic capital, and expected shortfall.

The first indicator of risk that a bank considers is expected loss. It is the level of loss that the bank is exposed to on average.

The expected loss on a security i is defined as

where EL is the expected loss and EAD is the exposure at default (the amount of investment outstanding in security i).

The expected loss of a portfolio of N assets is the sum of the expected losses on the constituents of the portfolio:

where LP denotes the random loss on the portfolio.

The expected loss contribution of a specific asset i to a portfolio is thus easy to determine. It carries information about the mean loss on the portfolio at a given horizon. This expected loss is normally assumed to be covered by the interest rates the bank charges to its clients. It does not bring any information about the potential extreme losses the bank faces because of a stock market crash or a wave of defaults, for example.

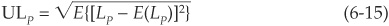

The unexpected loss ULP is defined as the standard deviation of portfolio losses:

If portfolio losses were normally distributed, expected and unexpected loss would completely characterize the loss distribution. The normal distribution is indeed specified by its first two moments.

Unfortunately, portfolio losses are far from being normal (Figure 6-1), and ELP and ULP are very partial measures of riskiness. In particular, unexpected loss ignores the asymmetric nature of returns (upside versus downside potential). Unexpected loss also fails to qualify as a coherent8 measure of risk as defined by Artzner, Delbaen, Eber, and Heath (1999). It is indeed possible to find two portfolios where  , although all

, although all  . Note that in the Basel II framework, UL corresponds to value at risk, rather than to the standard deviation of portfolio losses.

. Note that in the Basel II framework, UL corresponds to value at risk, rather than to the standard deviation of portfolio losses.

Value at risk is by far the most widely adopted measure of risk, in particular for market risk. It is also frequently used in credit risk although it is arguably less appropriate for reasons we explain below.

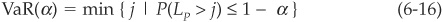

Value at risk addresses the issue of tail risk, i.e., the risk of large losses. The value at risk at the confidence level α (e.g., 95 percent) at a given horizon (usually 10 days for market risk and 1 year for credit risk) is the level of losses on the portfolio that will only be exceeded 1 − α percent of the time on average over that horizon. More formally,

It is important to bear in mind that a VaR measure is only meaningful if we know both the chosen horizon and the confidence level. Expected loss and value at risk are illustrated graphically in Figure 6-9.

FIGURE 6-9

Portfolio Loss Distribution

Several criticisms are commonly directed at value at risk. First, the value at risk at the α confidence level says nothing about the size of losses beyond that point. It is easy to create examples where the values at risk of two portfolios are identical but their level of extreme tail risk is very different. For example, Figure 6-10 shows two loss distributions that have the same 95 percent VaR. However, one of the loss distributions (solid line) has a much thinner right tail than the other one. The likelihood of a very large loss is much smaller with this distribution than with the other (dotted line).

FIGURE 6-10

Two Loss Distributions with Indentical VaR(95%)

VaR has the added drawback that it is not a coherent measure of risk (Artzner et al., 1999). In particular, it is not subadditive. In financial terms, it means that the value at risk of a portfolio may exceed the sum of the VaRs of the constituents of the portfolio.

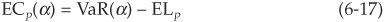

Finally, VaR tends to be very unstable at high confidence levels. For levels above, say, 99 percent confidence, changing the level of α by a small amount may lead to large swings in the calculated value at risk. In many instances, the plot of VaR(α) against α would look similar to Figure 6-11, computed for economic capital (EC). This is a matter of concern for banks, as they typically report their values at risk at confidence levels ranging from 99 to 99.99 percent.

FIGURE 6-11

Derivative of EC(α)

Economic capital is one of the key indicators for bank portfolio managers. Most of the time it is calculated at a 1-year horizon. The common market practice is to estimate the economic capital as

where ELP is the expected loss and VaR(α) is the value at risk at the confidence level α—for example, 99.9 percent.

Economic capital is interpreted as the amount of capital buffer that a bank needs to put aside to avoid being insolvent with α confidence level. Banks targeting a specific rating, say AA, will often consider it appropriate to hold a level of capital ECP(α) such that 1 − α corresponds to the probability of default of an AA-rated entity. This reasoning is flawed in general, as the rating agency analyst will consider many factors (business risk, for example) that are not reflected in economic capital (for more details see Chapter 7).

Another problem with economic capital that is directly inherited from the properties of value at risk is that it is very sensitive to the choice of the confidence level α and can be very unstable at high confidence levels. Figure 6-11 is a plot of the sensitivity of economic capital to the chosen confidence level:

The results are those of a Monte Carlo experiment, described in Chapter 5, where we simulated a very granular portfolio of 10,000 facilities with identical probability of default and pairwise correlation. Clearly at confidence levels above 99 percent, economic capital and value at risk become highly unstable. This implies that the level of capital on a bank’s book may change dramatically for only minor changes in the chosen level of confidence. Given that there is no theoretical reason for choosing one α over another, it is a significant drawback of both economic capital and value-at-risk measures. This observation shows that practitioners do not have a precise measurement of their risk far at the tail, i.e., corresponding to very improbable events. In order to compensate for such uncertainties, extreme value theory (EVT) models have been introduced in financial applications. This type of approach is devised to fit the tail of the distribution despite the scarcity of the data. EVT models stimulated a lot of interest among practitioners in the late nineties, but applications of these models to credit risk remain rare.

Other approaches are being developed to tackle the problem of tail instability. In particular, economic capital can be made a function of VaRs over a continuum of confidence levels. This average is weighted by a function reflecting the bank’s risk aversion (utility function). The averaging provides a much more stable measure of risk and capital (see Chapter 7).

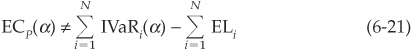

Expected shortfall (ES) is an alternative risk measure that focuses on the tail of the loss distribution. It is the average loss conditional on the loss being above the VaR(α) level and is thus similar to an insurance premium:

Expected shortfall is a coherent measure of risk and is progressively becoming a very popular complement of VaR. Combining VaR and ES indeed provides the risk manager with both a measure of the amount of risk at a given confidence level and also an estimate of the (mean) size of losses once that amount is breached. ES is also shown on Figure 6-9.

The previous section has shown how risk managers calculate the overall risk of their portfolios, in particular unexpected loss and value at risk. In this section, we explain how these two measures can be split into individual risk contributions at the facility level. This will be important in order to allocate capital appropriately to the various facilities (which we focus on in a later section).

In order to determine what facilities contribute most to the total risk of the portfolio, it is customary to use incremental or marginal VaR. The key academic reference on this topic is Gouriéroux, Laurent, and Scaillet (2000).

The incremental VaR of a facility i (IVaRi) is a measure defined as the difference between the value at risk of the entire portfolio (VaRP) minus the VaR of the portfolio without facility i (VaRP−i:

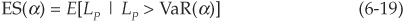

The main drawback of this measure is that incremental VaRs do not add up to the total value at risk of the portfolio. Therefore they are not appropriate for allocating economic capital, as

unless IVaRs are specifically rescaled to satisfy the equation.

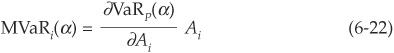

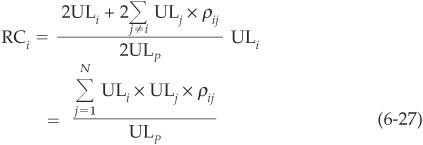

Another way to allocate economic capital to facilities is to consider marginal VaRs (MVaRs, also called delta VaRs). MVaRs are similar to IVaRs but are based on partial derivatives:

where Ai is the number of units of asset i held in the portfolio. MVaRs satisfy the additivity condition (the sum of marginal VaRs is the portfolio VaR):

which immediately leads to a rule for splitting economic capital among facilities:

Note that we write ECP,i(α) and not ECi(α). This is to emphasize that the economic capital allocated to facility i depends on the constitution of the portfolio and is not the economic capital corresponding to a portfolio of facility i only.

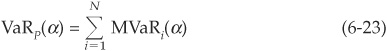

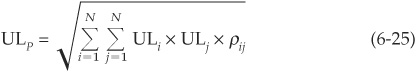

Recall that unexpected loss is simply the standard deviation of portfolio losses [Equation (6-15)]. The variance (square of the standard deviation) of portfolio losses is the sum of the covariances of the losses of individual facilities. Therefore

where ρij denotes the correlation of losses on facilities i and j.

The individual risk contribution RC of facility i to the unexpected loss of the portfolio is given by

The risk contribution is thus the sensitivity of the portfolio’s unexpected loss to changes in the unexpected loss of facility i times the size of RCi.

Differentiating Equation (6-25) and using (6-26), we can calculate the risk contributions explicitly:

Risk contributions calculated as above are the sum of covariances of asset i with all other assets scaled by the volatility (standard deviation) of portfolio losses. They satisfy

which is a desirable property for a risk measure. It means that the total risk of the portfolio is the sum of the individual risks of its constituents. It also leads to a formula for economic capital allocation at the portfolio level.

Assume that the risk manager has calculated the bank’s economic capital and unexpected loss such that

where mα is the multiplier, which typically ranges from 5 to 15 in practice. This multiplier calculated from Equation (6-29) can then be applied to calculate economic capital at the facility level.

The economic capital ECP,i allocated for a loan i in the portfolio is calculated with the following formula:

This rule is easy to implement in practice and widely used. We should bear in mind that it implies that risk is accurately measured by variances and covariances. While this is an appropriate assumption if losses are normally distributed, it is not correct in the case of credit losses.

To show this, it suffices to calculate the individual risk contributions RCi using Equation (6-27) and individual economic capital using Equation (6-24). Then it is possible to calculate the multiplier mα from Equation (6-30). If unexpected loss contribution were a good measure of marginal risk, we would find a multiplier that is similar across assets. In practice mα exhibits very large variations from one facility to the next, which indicates that covariances only partly capture joint risk among the facilities in the portfolio.

Now that we have an assessment of the individual contribution of a facility to the total risk of a portfolio, the next logical step is to balance this risk against the return offered by individual assets.

Traditional performance measures in the finance literature can generally be written as

For example, the Sharpe ratio is calculated as the expected excess return (over the riskless rate rf) on facility i divided by the volatility of the returns on asset i, σ,i:

The Treynor ratio replaces the total risk (volatility) by a measure of undiversifiable risk—the β of the capital asset pricing model (see, e.g., Alexander, Bailey, and Sharpe, 1999):

Both these measures and many others devised for portfolio selection treat assets as stand-alone facilities and do not consider diversification/concentration in the bank’s portfolio.

Unlike Equations (6-32) and (6-33), risk-adjusted performance measures enable bank managers to select projects as trade-offs between expected returns and cost in terms of economic capital [EC enters Equation (6-31) as the risk term]. We have seen that economic capital does integrate dependences across facilities, and the asset selection thus becomes specific to the bank’s existing portfolio.

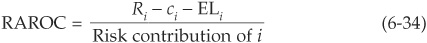

Many RAPMs have been proposed, depending on the definition of the risk, revenue Ri, and cost ci variables: RAROC, RORAC, RARORAC, and so on. It is easy to get lost in the numerous acronyms. Common practice is to use the generic term RAROC9 defined as

The denominator may be chosen to be the risk contribution calculated in Equation (6-27) or the marginal value at risk in Equation (6-22), or a version of the marginal economic capital [Equation (6-24) or (6-30)].

As mentioned above, the great novelty of RAROC compared with traditional risk-return trade-offs is the use of a risk measure that is specific to a bank’s existing holdings and incorporates dependences.

The simple formula (6-34) is intuitive and appealing but unfortunately not very easy to implement in practice for many instruments. In particular, the allocation of costs is not obvious. Costs include fixed operating costs as well as interest costs for funding the facility. Should these costs be split equally across assets?

Looking now at the traditional organization of a bank, many questions remain difficult to solve from a practical standpoint:

Banks often calculate their RAPM measures at the facility level rather than at the counterparty level. Should RAPM measures aggregate all the exposures vis-à-vis a client across all products, or should they be transaction-based? A client measure should clearly be preferred, given bankers’ appetite for cross-selling. From a practical standpoint it can be very difficult to implement, and it explains why many banks look primarily at transaction RAROC.

Banks often calculate their RAPM measures at the facility level rather than at the counterparty level. Should RAPM measures aggregate all the exposures vis-à-vis a client across all products, or should they be transaction-based? A client measure should clearly be preferred, given bankers’ appetite for cross-selling. From a practical standpoint it can be very difficult to implement, and it explains why many banks look primarily at transaction RAROC.

Allocating economic capital to existing customers ex post is a difficult task. At the origination level (ex ante) it is even more difficult to determine what the impact of a new facility will be on the whole portfolio of the bank without running the portfolio model. No bank, however, could afford to run a simulation-based model, including more than 50,000 credit lines, several times each day. Apart from making the assumption that the contribution of any new facility to the economic capital of the bank is marginal (which will often be a heroic assumption), the only alternative is to use quick analytic methods based, for example, on saddle point approximation.

Allocating economic capital to existing customers ex post is a difficult task. At the origination level (ex ante) it is even more difficult to determine what the impact of a new facility will be on the whole portfolio of the bank without running the portfolio model. No bank, however, could afford to run a simulation-based model, including more than 50,000 credit lines, several times each day. Apart from making the assumption that the contribution of any new facility to the economic capital of the bank is marginal (which will often be a heroic assumption), the only alternative is to use quick analytic methods based, for example, on saddle point approximation.

Once RAROC or another performance measure has been chosen and implemented, it enables the bank to rank its facilities from the best performing (highest risk-return ratio) to the worst.

However, this is insufficient for deciding whether an investment is worthwhile. For that purpose the bank needs to determine what the minimum acceptable level of risk-adjusted performance is for each of its business units. This corresponds to spelling out its risk aversion.

The critical level or risk-adjusted performance above which investments will be considered justified is called the hurdle rate. We can thus introduce an excess RAPM measure:

Note that RAPM* does not change the ranking of projects. It only makes more explicit the risk premium corresponding to the bank’s risk aversion. The hurdle rate is specified by the bank’s management and corresponds to the minimum return acceptable in a given business unit. The definition of an appropriate hurdle rate is very important. The process allowing us to define the hurdle rate is described in Chapter 7.

A fundamental assumption we have made up to this point is that the exposure at default is known in advance. This implicit assumption is made in Equation (6-13) and indirectly in all the following ones. While determining the EADi for a standard loan is easy, it is much less straightforward for derivative products such as swaps and options. Assume that we have bought a call from a bank and that the bank defaults before the maturity of our option. At the maturity, if the call expires out of the money (worthless), our exposure at default is zero and default is harmless. However, if the call ends up deep in the money, the exposure at default will be substantial. The same is true for a swap contract where the counterparts are positively or negatively exposed to default risk depending on whether they are on the receiving or paying side of the contract (i.e., if interest rates change in their favor or not).

The “proper” way to deal with such complexity is to use a full model for the underlying stock price or interest rate to determine the distribution of the exposure at default. The risk measures described above can be computed by Monte Carlo simulations. The process can prove time-consuming, and it is often not easy to determine the joint distribution of the default events and the price of the underlying asset of the option.

In order to simplify this process, banks rely on a fairly crude approach of “loan equivalence.” The loan equivalent of a complex instrument is an average of the positive exposure during the life of the contract. Once this average is computed, it is plugged into Equation (6-13) and onward, and it is assumed that the loss on the derivative instrument is similar to the loss on a loan with this average exposure at default.

RAROC is a useful tool for measuring performance and is widely used by banks. In the survey by Brannan, Mengle, Smithson, and Zmiewski (2002), the authors report that 78 percent of the banks explicitly using a performance measure for their credit portfolio use RAROC. There seem to be as many definitions of RAROC as there are financial institutions, but they all have in common the calculation of a risk-return trade-off that takes into account portfolio diversification. The chosen RAROC measure will only be as good (or as bad) as its constituents, namely the net return measure (numerator) and the risk component (denominator). We have seen that many commonly used risk measures (in particular those based on unexpected loss) suffer from severe deficiencies linked to the fact that credit portfolios are skewed and fat-tailed.

As a final word of caution, we would like to stress that the usual RAROC is calculated ex ante, i.e., in order to select the best assets for the future. The effect of an additional facility (a new investment) is assumed to have a marginal impact on the portfolio and on the economic capital of the bank. This may be a fair assumption if the new facility is small, but ex ante RAROC may differ substantially from ex post RAROC for large positions. The usefulness of RAROC for dynamic capital allocation may therefore be very limited, as we will see in the next chapter.

In this section we want to briefly highlight the impact of the business cycle on portfolio loss distributions. By doing so, we will show how important it is to carry out careful stress tests on the various inputs of the model, in particular on probabilities of default and correlations.

We perform a simulation experiment on a portfolio of 100 non-investment-grade bonds with unit exposure, identical probabilities of default, and pairwise default correlations. We consider three scenarios:

1. Growth scenario. The default probability for all bonds is equal to the average probability of default of a NIG bond in a year of expansion10 (4.32 percent), and the correlation is set equal to its average value in expansion (0.7 percent).

2. Recession scenario. The default probability for all bonds is equal to the average probability of default of a NIG bond in a year of recession (8.88 percent), and the correlation is set equal to its average value in recession (1.5 percent).

3. Hybrid scenario. Default probability = recession value, and correlation = expansion value.

For all scenarios the recovery associated with each default is drawn from a beta distribution with mean 0.507 and standard deviation 0.358.11

Portfolio losses are then calculated as the sum of losses on individual positions. The smoothed distributions of losses are plotted on Figure 6-12. When moving from the growth scenario to either the hybrid or the recession scenario, we can observe a shift in the mean of the loss distribution. This shift is due to the significant increase in probabilities of default in recessions. Comparing the tail of the loss distribution in the hybrid scenario with that in the recession case (both cases have the same mean default rate), we can see that the recession scenario has a fatter tail. This is purely attributable to increases in correlations.

FIGURE 6-12

Correlation and the Business Cycle

Figure 6-13 focuses specifically on the tail of the distributions. More precisely, it compares the credit VaR in the three scenarios for various confidence levels. The gap between the growth VaR and the hybrid VaR is due exclusively to the increase in PDs during recessions, whereas the gap between the hybrid and the recession cases is the correlation contribution.

FIGURE 6-13

Credit VaR in Growth and Recession

Figure 6-14 displays the same information but in relative terms. It shows the percentage of the increase in portfolio credit VaR that can be attributed to the increase in correlation or to the increase in probabilities of default in a recession year. At very high confidence levels, the correlation becomes the dominant contributor.

FIGURE 6-14

Relative Contributions of Correlation and PDs to VaRs

The implication for banks is that they should perform careful stress tests not only on their PD assumptions but also on their correlation assumptions. When reporting VaR at very high confidence levels, a substantial part of the information conveyed by the figures relates to correlations. We have seen in Chapter 5 that default correlations were estimated with a lot of uncertainty and that different sources of data (equity versus realized defaults, for example) could lead to very different results. It is therefore advisable to triangulate the approaches to correlations and to treat correlation inputs in credit portfolio models conservatively.

Portfolio models have received considerable attention in the past years. Some canonical methodologies have been developed, including the rating-based approach and the actuarial models. Calculation speed has then become a major area of focus with the introduction of semianalytical methods such as fast Fourier transform, saddle point, and related techniques.

With the wider use of more complex financial products like ABSs, CDOs, and credit default swaps, the current challenge is to integrate these new tools in portfolio management tools in a relevant manner. Another outstanding issue is the precise measurement of the benefits of portfolio diversification under changing economic conditions.

For the future, we anticipate a trend aimed at reuniting pricing and risk measurement. Portfolio tools used by banks indeed provide marked-to-model information. Shifting to marked-to-market is, in our view, the next frontier.

Many computer packages include built-in functions to generate random variables in specific standard distributions such as the normal, gamma, x2, etc.

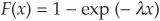

A general procedure to draw random variables from an arbitrary but known distribution is the following:

1. Draw random variables (R.V.) from a uniform [0,1] distribution. This is always available in standard computer packages.

2. Invert the cumulative distribution function to obtain random variables with the chosen distribution.

The cumulative distribution function is  . The first step consists of drawing n uniform [0,1]-distributed random variables Ui, for

. The first step consists of drawing n uniform [0,1]-distributed random variables Ui, for  . Then by inverting the distribution function, we can obtain

. Then by inverting the distribution function, we can obtain  , which follows the appropriate exponential distribution.

, which follows the appropriate exponential distribution.

For many distributions, such as the normal or the beta used to simulate factors or recovery rates in credit models, there is no closed form for the inverse function F−1(x). A numerical inversion can, however, be performed.

Figure 6A-1 summarizes the procedure for the normal distribution and the t-distribution with 3 degrees of freedom. Drawing a random number x from the uniform distribution and inverting the normal distribution and t-distribution, we can obtain two different random numbers from the chosen distributions.

FIGURE 6A-1

Drawing Normal and t-Distributed Random Variables

Factors used in credit risk portfolio models are frequently correlated and have to be simulated jointly. Assume, for instance, that we want to draw N realizations of a matrix of M correlated standard normal variables (as in CreditMetrics, for example, where factors follow a multivariate normal distribution). We will thus draw an N × M matrix A with random elements.

We use Ω to denote the M ×M factor covariance matrix and proceed in three steps:

Draw an N ×M matrix of uncorrelated uniform random variables.

Draw an N ×M matrix of uncorrelated uniform random variables.

Invert the cumulative standard normal distribution function as explained above to obtain an N ×M matrix B of uncorrelated standard normal variables.

Invert the cumulative standard normal distribution function as explained above to obtain an N ×M matrix B of uncorrelated standard normal variables.

Impose the correlation structure by multiplying B by the Choleski decomposition of the covariance matrix Ω [chol(Ω)].

Impose the correlation structure by multiplying B by the Choleski decomposition of the covariance matrix Ω [chol(Ω)].

Then C = chol(Ω) × B is an N × M matrix of normally distributed R.V. with the desired correlations.

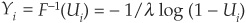

In this appendix we want to calculate the default correlation between Vivendi Universal and General Motors. Vivendi Universal is a company involved in mobile telecommunications (T) and leisure (L). General Motors is the world’s largest car manufacturer (industry C).

The analyst considers that the exposure of Vivendi is the following12:

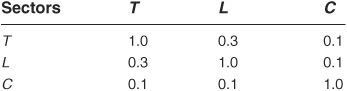

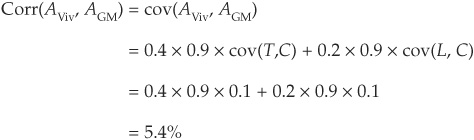

while that for General Motors is

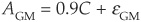

The factor correlation matrix, estimated from equity indices, is the following:

We can immediately calculate the two firms’ asset correlation13:

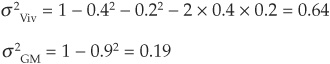

The variances of the idiosyncratic term can be calculated using the constraint that the asset returns have unit variance:

At the end of 2002, Vivendi and GM were rated BB and BBB, respectively, by S&P. Looking up the 1-year average default rates for issuers in BB and BBB categories, we find 1.53 percent and 0.39 percent.

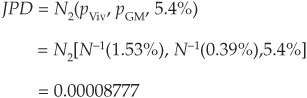

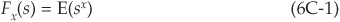

We can now immediately calculate the joint probability of default JPD for Vivendi and GM at the 1-year horizon (see Chapter 5):

Finally, the default correlation is obtained as

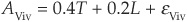

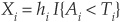

In this appendix we provide a more extensive derivation of the loss distribution and finally review implementation issues and extensions. We have already dealt with the inputs for the model and the general setup in the main body of the chapter.

In this section we derive the main results of the CreditRisk+ model. We start by introducing the simple case where the portfolio consists of only one asset with constant probability of default, and we introduce the concept of the probability generating function. We then extend the setup to the case of multiple assets and finally allow for the grouping of assets in homogeneous groups and for probabilities of default to be stochastic.

The model considers two states of the world for each issuer:

Default with probability pA

Default with probability pA

No default with probability (1 − pA)

No default with probability (1 − pA)

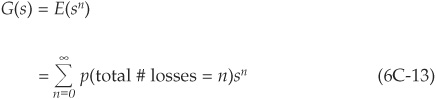

The probability of default for a given issuer is assumed to be constant through time. We can then calculate the probability distribution of a portfolio of N independent facilities.

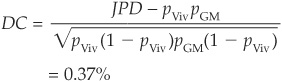

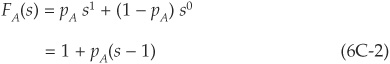

The probability generating function (PGF) Fx for a random variable x is defined as

where s in an auxiliary variable.

In the case of a binomial random variable such as A above, we find

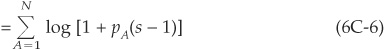

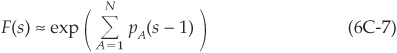

The PGFF(s) of a sum of N independent random variables is the product of the individual PGF:

Taking logarithms, we get

Recall that for Z small, log  . Using this approximation, we find

. Using this approximation, we find

where  is the mean number of defaults.

is the mean number of defaults.

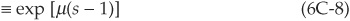

Expanding the exponential in (6C-8) and comparing with (6C-1), we find

where Eµ (.) denotes the expectation of a Poisson distribution with parameter. µ

This shows that, providing that the approximation in (6C-7) is acceptable (small probabilities of default), the distribution of a portfolio of independent binomial variables (default/no default) follows a Poisson distribution.

CreditRisk+ then groups exposures in m homogeneous buckets. Each bucket is characterized by having exposures of the same size vjL and with identical expected loss εjL for  . L is the size of a unit loss (e.g., $100,000). The smaller L, the more precise the buckets, but also the more numerous. Exposures in one group are assumed to be independent of exposures in other groups.

. L is the size of a unit loss (e.g., $100,000). The smaller L, the more precise the buckets, but also the more numerous. Exposures in one group are assumed to be independent of exposures in other groups.

In each bucket the expected number of defaults is µj, which is assumed to be known. For each individual bucket we are therefore in a similar situation as in (6C-10):

Dividing the mean loss by the size of the individual losses, we have the mean number of losses:

We can now compute the PGF of the entire portfolio G(Z) by aggregating the losses arising from all independent groups:

Using the independence assumption, we get

using the same approximation as in (6C-7).

Continuing the calculations, we get

with

and

We have just obtained a closed-form expression for the probability generating function of the loss of the portfolio.

In order to obtain the actual distribution of losses from the PGF, we use the following relationship:

This can be calculated recursively using the following algorithm proposed by CreditRisk+:

We now consider the case where probabilities of default are random. Facilities remain independent, but the randomness in probability of default will help generate fat tails in the portfolio loss distribution. The portfolio still comprises N facilities grouped in n sectors. An individual borrower A has probability of default XA, which has mean pA and standard deviation σA.

The default rate Xk in a specific sector k is assumed to follow a gamma distribution with mean  and standard deviation

and standard deviation  for

for  . The probability density function for the gamma distribution is

. The probability density function for the gamma distribution is

with

We again introduce the probability generating function F(s) of portfolio losses in terms of sector loss PGF Fk(s):

using the independence assumption.

The PGF for sector losses is less straightforward than in previous cases because the mean loss rate is itself random. However, conditional on a specific realization of the mean loss rate  , we can treat Xk as a constant, and we are back to the case described in Equation (6C-37) and onward:

, we can treat Xk as a constant, and we are back to the case described in Equation (6C-37) and onward:

The probability generating function for the loss in a given sector k can be expressed as the sum (integral) of the probability generating function conditional on realizations of the factors:

Plugging (6C-21) and (6C-22) into (6C-25) and simplifying, we obtain

where

Developing (6C-27), we get a nice formula for the PGF in a given sector:

We recognize the expectation of sn using the binomial law, from which we conclude using (6C-1):

In the same way that (6C-15) extends (6C-10) when homogeneous buckets are created, (6C-23) to (6C-29) extend to

where

The probability generating function can be written as a power series expansion:

where the An terms can be calculated using a recurrence rule.

The recurrence rule proposed in CreditRisk+ is easy to implement. It is based on the widely used Panjer (1981) algorithm. Unfortunately it suffers from numerical problems. For example, for very large portfolios, µ [in Equation (6C-20)] may be very large. At some point the computer will round off e−µ to 0, and the algorithm will stall. Another caveat comes from the fact that the recurrence algorithm accumulates rounding errors. After several iterations, the calculated values may differ significantly from the true output of the algorithm because of rounding by the computer.

Gordy (2002) proposes to apply saddle point methods (see Appendix 6D) to benchmark the standard algorithm. While the output of saddle points does not outperform the standard algorithm in all regions of the distribution and for all values of the input parameters, it appears to be accurate in the cases where the Panjer algorithm leads to numerical difficulties.

Giese (2003) offers yet another alternative. Unlike saddle point approximations, it is exact but relies on a faster and more stable algorithm that does not break down when the portfolio size or the number of factors is large. The author also suggests a way to incorporate correlations between factors.

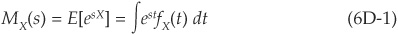

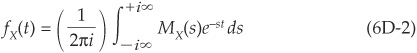

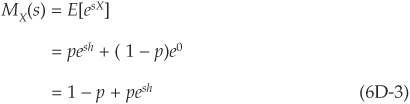

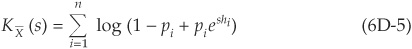

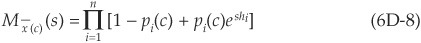

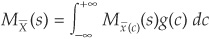

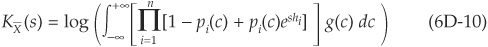

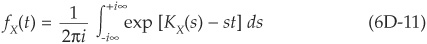

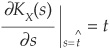

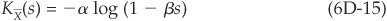

In this appendix we start by introducing moment and cumulant generating functions and then describe the saddle point methodology and give an example to illustrate its accuracy.

In some cases where the distribution of portfolio losses fX is very complex, there may be a tractable expression for the moment generating function (MGF) MX.

The MGF of the random loss X is defined in terms of an auxiliary variable s:

Conversely we can obtain the density from the MGF through

Assume, for example, that the random variable X defines a risky bond that may default with probability p. If it does default, then the loss is h (h can be seen as loss given default times exposure at default); if not, the loss is zero.

We can simply calculate MX(s) as

Cumulant generating functions have the nice property that they are multiplicative for independent random variables Xi, for  . Alternatively, their logarithms [the cumulant generating functions KX(s)] are additive.

. Alternatively, their logarithms [the cumulant generating functions KX(s)] are additive.

Define

Then

For a portfolio of independent bonds, we obtain15:

and

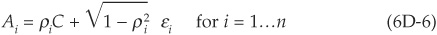

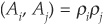

Naturally the various lines in a portfolio are not independent. However, in the usual framework of conditionally independent defaults corresponding to most factor models, we can extend this approach.

Consider the case of a one-factor model (already introduced in Chapter 5). The firms’ asset returns follow:

such that var , cov

, cov  for

for  , cov

, cov for

for  and cov

and cov for all i.

for all i.