In Chapters 2, 3, and 4 we considered default probabilities and recovery rates for individual obligors. At the portfolio level, individual PDs and LGDs are important but insufficient to determine the entire distribution of losses. The portfolio loss distribution is not the sum of distributions of individual losses because of diversification effects.

In this chapter we introduce multivariate effects, i.e., interactions between facilities or obligors. Portfolio measures of credit risk require measures of dependency across assets. Dependency is a broad concept capturing the fact that the joint probability of two events is in general not simply the product of the probabilities of individual events.

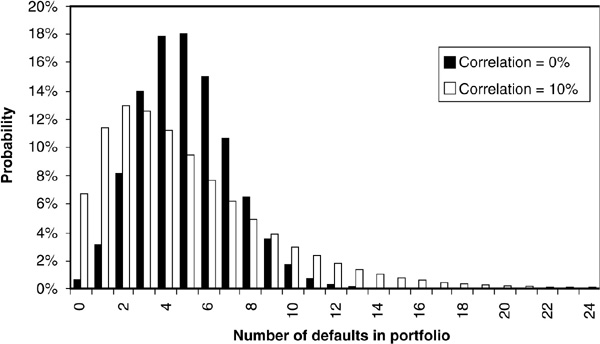

The most common measure of dependency is linear correlation.1Figure 5-1 illustrates the impact of correlation on portfolio losses.2 When the default correlation is zero, the probability of extreme events (large number of defaults or zero default) is low. However, when the correlation is significant, the probability of very good or very bad events increases substantially. Given that risk managers focus a lot on tail measures of credit risk such as value at risk and expected shortfall (see the next chapter), correlations are of crucial importance.

FIGURE 5-1

Effect of Correlations on Portfolio Losses

For most marginal distributions, however, the linear correlation is only part of the dependency structure and is insufficient to construct the joint distribution of losses. In addition, it is possible to construct a large set of different joint distributions from identical marginal distributions. Correlation is therefore a weaker concept than dependency, except in particular cases. A large section of this chapter will be dedicated to alternative dependency measures.

Dependency also includes more complex effects such as the co-movement of two variables with a time lag, or causality effects. In a time-series context, correlation provides information about the simultaneity of events, but not on which event triggered another. It ignores contagion and infectious events (see, e.g., Davis and Lo, 1999a, 1999b).

In this chapter, we will focus primarily on measuring default dependencies rather than on explaining them. Before doing so, it is worth spending a little time on the sources of joint defaults.

Defaults occur for three main types of reasons:

Firm specific reasons. Bad management, fraud, large project failure, etc.

Firm specific reasons. Bad management, fraud, large project failure, etc.

Industry-specific reasons. Entire sectors sometimes get hit by shocks such as overcapacity or a rise in the prices of raw materials.

Industry-specific reasons. Entire sectors sometimes get hit by shocks such as overcapacity or a rise in the prices of raw materials.

General macroeconomic conditions. Growth and recession, interest rate changes, and commodity prices affect all firms to various degrees.

General macroeconomic conditions. Growth and recession, interest rate changes, and commodity prices affect all firms to various degrees.

Firm-specific causes do not lead to correlated defaults. Defaults triggered by these idiosyncratic factors tend to occur independently. In contrast, macroeconomic and sector-specific shocks do lead to increases in the default rates of entire segments of the economy and push up correlations.

Figure 5-2 depicts the link between macroeconomic growth (measured by the growth in gross domestic product) and the default rate of non-investment-grade issuers. The default rate appears to be almost a mirror image of the growth rate. This implies that defaults will tend to be correlated since they depend on a common factor.

FIGURE 5-2

U.S. GDP Growth and Aggregate Default Rates

FIGURE 5-3

Default Rates in the Telecom and Energy Sectors

Figure 5-3 shows the impact of a sector crisis on default rates in the energy and telecom sectors. The surge in oil prices in the mid-eighties and the telecom debacle starting in 2000 are clearly visible. Commercial models of credit risk presented in Chapter 6 incorporate sector, idiosyncratic, and macroeconomic factors.

We begin this chapter with a review of useful statistical concepts. We start by introducing the most popular measures of dependency (covariance and correlation) and show how to compute the variance of a portfolio from individual risks.

Next we use several examples to illustrate that correlation is only a partial and sometimes misleading measure of the co-movement or dependency of random variables. We review various other partial measures and introduce copulas, which fully describe multivariate distributions.

These statistical preliminaries are useful for understanding the last section in the chapter, which deals with credit-specific applications of these dependency measures. Various methodologies have been proposed to estimate default correlations. These can be extracted directly from default data or derived from equity or spread information.

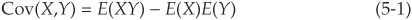

The covariance between two random variables X and Y is defined as

where E(.) denotes the expectation. It measures how two random variables move together.

The covariance satisfies two useful properties:

Cov(X,X) = var(X), where var (X) is the variance

Cov(X,X) = var(X), where var (X) is the variance

Cov(aX,bY) = ab cov(X,Y)

Cov(aX,bY) = ab cov(X,Y)

In the case where X and Y are independent,  , and the covariance is 0.

, and the covariance is 0.

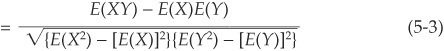

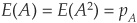

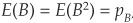

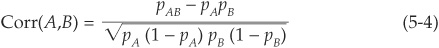

The correlation coefficient conveys the same information about the co-movement of X and Y but is scaled to lie between −1 and +1. It is defined as the ratio of X and Y covariance to the product of their standard deviations:

In the particular case of two binary (0,1) variables A and B, taking value 1 with probability pA and pB, respectively, and 0 otherwise and with joint probability pAB, we can calculate  ,

,  , and

, and  .

.

The correlation is therefore

This formula will be particularly useful for default correlation because defaults are binary events. Later in the chapter we will explain how to estimate the various terms in the above equation.

Let us first consider a simple case of a portfolio with two assets X and Y with proportions w and 1 − w, respectively. Their variances and covariance are  ,

, , and σXY.

, and σXY.

The variance of the portfolio is given by

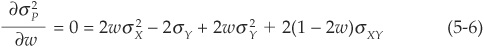

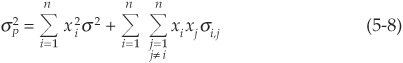

The minimum variance of the portfolio can be obtained by differentiating Equation 5-5 and setting the derivative equal to 0:

The optimal allocation w* is the solution to Equation (5-6):

We thus find the optimal allocation in both assets that minimizes the total variance of the portfolio. We can immediately see that the optimal allocation depends on the correlation between the two assets and that the resulting variance is also affected by the correlation. Figures 5-1 and 5-2 illustrate how the optimal allocation and resulting minimum portfolio variance change as a function of correlation. In this example,  and

and  .

.

In Figure 5-4 we can see that the allocation of the portfolio between X and Y is highly nonlinear in the correlation. If the two assets are highly positively correlated, it becomes optimal to sell short the asset with highest variance (X in our example); hence w* is negative. If the correlation is “perfect” between X and Y, i.e., if  or

or  1 it is possible to create a riskless portfolio (Figure 5-5). Otherwise the optimal allocation w* will lead to a low but positive variance.

1 it is possible to create a riskless portfolio (Figure 5-5). Otherwise the optimal allocation w* will lead to a low but positive variance.

FIGURE 5-4

Optimal Allocation versus Correlation

FIGURE 5-5

Minimum Portfolio Variance versus Correlation

Figure 5-6 shows the impact of correlation on the joint density of X and Y, assuming that they are standard normally distributed. It is a snapshot of the bell-shaped density seen “from above.” In the case where the correlation is zero (left-hand side), the joint density looks like concentric circles. When nonzero correlation is introduced (positive in this example), the shape becomes elliptical: It shows that high (low) values of X tend to be associated with high (low) values of Y. Thus there is more probability in the top-right and bottom-left regions than in the top-left and bottom-right areas. The reverse would have been observed in the case of negative correlation.

FIGURE 5-6

Impact of Correlation on the Shape of the Distribution

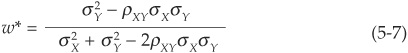

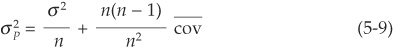

We can now apply the properties of covariance to calculate the variance of a portfolio with multiple assets. Assume that we have a portfolio of n instruments with identical variance σ2 and covariance σi,j for i,  .

.

The variance of the portfolio is given by

where xi is the weight of asset i in the portfolio.

Assuming that the portfolio is equally weighted:  , for all i, and that the variance of all assets is bounded, the variance of the portfolio reduces to:

, for all i, and that the variance of all assets is bounded, the variance of the portfolio reduces to:

where the last term is the average covariance between assets.

When the portfolio becomes more and more diversified, i.e., when  , we have

, we have  . The variance of the portfolio converges to the average covariance between assets. The variance term becomes negligible compared with the joint variation.

. The variance of the portfolio converges to the average covariance between assets. The variance term becomes negligible compared with the joint variation.

For a portfolio of stocks, diversification benefits are obtained fairly quickly: For a correlation of 30 percent between all stocks and a volatility of 30 percent, we are within 10 percent of the minimum covariance with n around 20. For a pure default model (i.e., when we ignore spread and transition risk and assume 0 recovery) the number of assets necessary to reach the same level of diversification is much larger. For example, if the probability of default and the pairwise correlations for all obligors are 2 percent, we need around 450 counterparts to reach a variance that is within 10 percent of its asymptotic minimum.

As mentioned earlier, correlation is by far the most used measure of dependency in financial markets, and it is common to talk about correlation as a generic term for co-movement. We will use it a lot in the section of this chapter on default dependencies and in the following chapter on portfolio models. In this section we want to review some properties of the linear correlation that make it insufficient as a measure of dependency in general—and misleading in some cases. This is best explained through examples.3

Using Equation (5-2), we see immediately that correlation is not defined if one of the variances is infinite. This is not a very frequent occurrence in credit risk models, but some market risk models exhibit this property in some cases.

Using Equation (5-2), we see immediately that correlation is not defined if one of the variances is infinite. This is not a very frequent occurrence in credit risk models, but some market risk models exhibit this property in some cases.

Example. See the vast financial literature on α -stable models since Mandelbrot (1963), where the finiteness of the variance depends on the value of the α parameter.

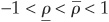

When specifying a model, one cannot choose correlation arbitrarily over [−1,1] as a degree of freedom. Depending on the choice of distribution, the correlation may be bounded in a narrower range

When specifying a model, one cannot choose correlation arbitrarily over [−1,1] as a degree of freedom. Depending on the choice of distribution, the correlation may be bounded in a narrower range  , with

, with  .

.

Example. Suppose we have two normal random variables x and y, both with mean 0 and with standard deviation 1 and σ, respectively. Then  and

and  are lognormally distributed. However, not all correlations between X and Y are attainable. We can show that their correlation is restricted to lie between

are lognormally distributed. However, not all correlations between X and Y are attainable. We can show that their correlation is restricted to lie between

See Embrecht, McNeil, and Strautmann (1999a) for a proof.

Two perfectly functionally dependent random variables can have zero correlation.

Two perfectly functionally dependent random variables can have zero correlation.

Example. Consider a normally distributed random variable X with mean 0 and define  . Although changes in X completely determine changes in Y, they have zero correlation. This clearly shows that while independence implies zero correlation, the reverse is not true!

. Although changes in X completely determine changes in Y, they have zero correlation. This clearly shows that while independence implies zero correlation, the reverse is not true!

Linear correlation is not invariant under monotonic transformations.

Linear correlation is not invariant under monotonic transformations.

Example. (X,Y) and [exp (X), exp (Y)] do not have the same correlation.

Many bivariate distributions share the same marginal distributions and the same correlation but are not identical.

Many bivariate distributions share the same marginal distributions and the same correlation but are not identical.

Example. See the section in this chapter on copulas.

All these considerations should make it clear that correlation is a partial and insufficient measure of dependency in the general case. It only measures linear dependency. This does not mean that correlation is useless. For the class of elliptical distributions, correlation is sufficient to combine the marginals into the bivariate distribution. For example, given two normal marginal distributions for X and Y and a correlation coefficient ρ, we can build a joint normal distribution for (X,Y).

Loosely speaking, this class of distribution is called elliptical because when we project the multivariate density on a plane, we find elliptical shapes (see Figure 5-6). The normal and the t-distribution, among others, are part of this class.

Even for other nonelliptical distributions, covariances (and therefore correlations) are second moments that need to be calibrated. While they are insufficient to incorporate all dependency, they should not be neglected when empirically fitting a distribution.

Many other measures have been proposed to tackle the problems of linear correlations mentioned above. We only mention two here, but there are countless examples.

Spearman’s rho. This is simply the linear correlation but applied to the ranks of the variables rather than on the variables themselves.

Spearman’s rho. This is simply the linear correlation but applied to the ranks of the variables rather than on the variables themselves.

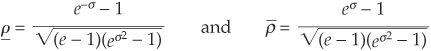

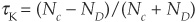

Kendall’s tau. Assume we have n observations for each of two random variables, i.e., (Xi,Yi), where

Kendall’s tau. Assume we have n observations for each of two random variables, i.e., (Xi,Yi), where  .

.

We start by counting the number of concordant pairs, i.e., pairs for which the two elements are either both larger or both lower than the elements of another pair. Call that number Nc.

Then Kendall’s tau is calculated as

where ND is the number of discordant (nonconcordant) pairs.

Kendall’s tau shares some properties with the linear correlation: τK∈[–1,1] and  for X,Y independent. However, it has some distinguishing features that make it more appropriate than the linear correlation in some cases. If X and Y are comonotonic,4 then

for X,Y independent. However, it has some distinguishing features that make it more appropriate than the linear correlation in some cases. If X and Y are comonotonic,4 then  ; while if they are countermonotonic,

; while if they are countermonotonic,  . σK is also invariant under strictly monotonic transformations. To return to our example above,

. σK is also invariant under strictly monotonic transformations. To return to our example above,  = σK [exp (X),exp (Y)].

= σK [exp (X),exp (Y)].

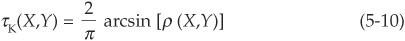

In the case of the normal distribution, the linear and rank correlations can be linked analytically:

These dependency measures have nice properties but are much less used by finance practitioners. Again they are insufficient to obtain the entire bivariate distribution from the marginals. The function that achieves this task is called a copula. We now turn to this important statistical concept and will come back to Spearman’s rho and Kendall’s tau when we express them in terms of the copula.

A copula is a function that combines univariate density functions into their joint distribution. A comprehensive analysis of copulas is beyond the scope of this book,5 but we just want to provide sufficient background to understand the applications of copulas to credit risk that will be discussed below. Applications of copulas to risk management and the pricing of derivatives have soared over the past few years.

Definition. A copula with dimension n is an n-dimensional probability distribution function defined on [0,1]n that has uniform marginal distributions.

One of the most important and useful results about copulas is known as Sklar’s theorem (Sklar, 1959). It states that any group of random variables can be joined into their multivariate distribution using a copula. More formally: If Xi, for i = 1…n, are random variables with respective marginal distributions Fi, for i = 1…n, and multivariate probability distribution function F, then there exists an n-dimensional copula such that

and

Furthermore, if the marginal distributions are continuous, then the copula function is unique.

Looking at Equation (5-11a), we clearly see how to obtain the joint distribution from the data. The first step is to fit the marginal distributions Fi, i = 1 …n, individually on the data (realizations of Xi, i = 1…n). This yields a set of uniformly distributed random variables  , …,

, …,  .

.

The second step is to find the copula function that appropriately describes the joint behavior of the random variables. There is a plethora of possible choices that make the use of copulas sometimes impractical. Their main appeal is that they allow us to separate the calibration of the marginal distributions from that of the joint law. Figure 5-7 is a graph of a bivariate Frank copula (see below for an explanation).

FIGURE 5-7

Shape of a Bivariate Copula

Copulas satisfy a series of properties including the four listed below. The first one states that for independent random variables, the copula is just the product of the marginal distributions. The second property is that of invariance under monotonic transformations. The third property provides bounds on the values of the copula. These bounds correspond to the values the copula would take if the random variables were countermonotonic (lower bound) or comonotonic (upper bound). Finally the fourth one states that a convex combination of two copulas is also a copula.

Using similar notations as above where X and Y denote random variables and u and v stand for the uniformly distributed margins of the copula, we have:

1. If X and Y are independent, then  .

.

2. Copulas are invariant under increasing and continuous transformations of marginals.

3. For any copula C, we have max

4. If C1 and C2 are copulas, then  , for

, for  , is also a copula.

, is also a copula.

We now briefly review two important classes of copulas which are most frequently used in risk management applications: elliptical (including Gaussian and student-t) copulas and Archimedean copulas.

There are a wide variety of possible copulas. Many but not all are listed in Nelsen (1999). In what follows, we introduce elliptical and Archimedean copulas. Among elliptical copulas, Gaussian copulas are now commonly used to generate dependent random vectors in applications requiring Monte-Carlo simulations (see Wang, 2000, or Bouyé, Durrelman, Nikeghbali, Riboulet, and Roncalli, 2000). The Archimedean family is as convenient as it is parsimonious and has a simple additive structure. Applications of Archimedean copulas to risk management can be found in Schönbucher (2002) or Das and Geng (2002), among many others.

Elliptical Copulas: Gaussian and t-Copulas Copulas, as noted above, are multivariate distribution functions. Obviously the Gaussian copula will be a multivariate Gaussian (normal) distribution.

Using the notations of Equation (5-11b), we can write  , the n- dimensional Gaussian copula with covariance matrix Σ:

, the n- dimensional Gaussian copula with covariance matrix Σ:

where  and N−1 denote, respectively, the n-dimensional cumulative Gaussian distribution with covariance matrix Σ and the inverse of the cumulative univariate standard normal distribution.

and N−1 denote, respectively, the n-dimensional cumulative Gaussian distribution with covariance matrix Σ and the inverse of the cumulative univariate standard normal distribution.

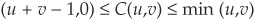

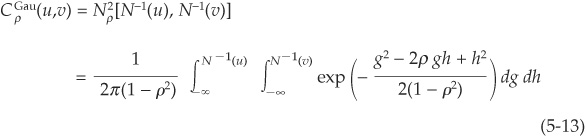

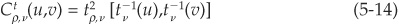

In the bivariate case, assuming that the correlation between the two random variables is ρ, Equation (5-12) boils down to

The t-copula (bivariate t-distribution) with v degrees of freedom is obtained in a similar way. Using evident notations, we have

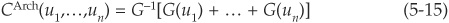

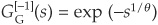

Archimedean Copulas The family of Archimedean copulas is the class of multivariate distributions on [0,1]n that can be written as

where G is a suitable function from [0,1] to ]0,∞ [satisfying  and

and  called the generator of the copula.

called the generator of the copula.

Three examples of Archimedean copulas used in the finance literature are the Gumbel, the Frank, and the Clayton copulas, for which we provide the functional form now. They can easily be built by specifying their generator (see Marshall and Olkin, 1988, or Nelsen, 1999).

Example 1 The Gumbel Copula (Multivariate Exponential)

The generator for the Gumbel copula is

with inverse

and  .

.

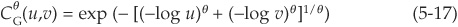

Therefore using Equation (5-15), the copula function in the bivariate case is

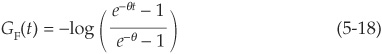

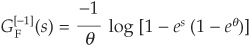

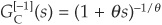

Example 2 The Frank Copula

The generator is

with inverse

and  .

.

The bivariate copula function is therefore

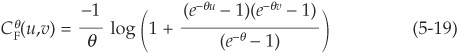

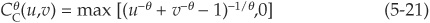

Example 3 The Clayton Copula

The generator is

and  .

.

The bivariate copula function is therefore

Assume we want to calculate the joint cumulative probability of two random variables X and Y:  . Both X and Y are standard normally distributed. We are interested in looking at the joint probability depending on the choice of copula and on the parameter θ.

. Both X and Y are standard normally distributed. We are interested in looking at the joint probability depending on the choice of copula and on the parameter θ.

The first step is to calculate the margins of the copula distribution:  and

and  . For our numerical example, we assume

. For our numerical example, we assume  and

and  . Hence

. Hence  and

and  .

.

The joint cumulative probability is then obtained by plugging these values into the chosen copula function [Equations (5-17), (5-19), and (5-21)]. Figure 5-8 illustrates how the joint probabilities change as a function of θ for the three Archimedean copulas presented above. The graph shows that different choices of copulas and theta parameters lead to very different results in terms of joint probability.

FIGURE 5-8

Examples of Joint Cumulative Probabilities Using Archimedean Copulas

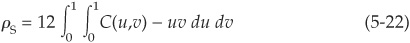

Recall that earlier in the chapter we introduced Spearman’s rho and Kendall’s tau as two alternatives to linear correlation. We mentioned that they could be expressed in terms of the copula. The formulas linking these dependency measures to the copula are

Spearman’s rho:

Spearman’s rho:

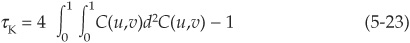

Kendall’s tau:

Kendall’s tau:

Thus once the copula is defined analytically, we can immediately calculate rank correlations from it. Copulas also incorporate tail dependency. Intuitively, tail dependency will exist when there is a significant probability of joint extreme events. Lower (upper) tail dependency captures joint negative (positive) outliers.

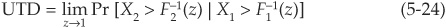

If we consider two random variables X1 and X2 with respective marginal distributions F1 and F2, the coefficients of lower (LTD) and upper tail dependency (UTD) are

and

Figure 5-9 illustrates the asymptotic dependency of variables in the upper tail, using t-copulas. The tail dependency coefficient shown corresponds to UTD.

FIGURE 5-9

Upper-Tail Dependency Coefficients for Gaussian and t-Copulas for Various Asset Correlations

This section completes our introduction to correlation, copulas, and other dependency measures. We have shown that, although overwhelmingly used by finance practitioners, correlation is a partial indicator of joint behavior. The most general tool for that purpose is the copula, which provides a complete characterization of the joint law. But which copula to use? This is a difficult question to address in practice, and choices are often (always?) driven by practical considerations rather than any theoretical reasons. The choice of one family of copulas against another or even of a specific copula over another in the same class may lead to substantial differences in the outcome of the model, be it an option price or a tail loss measure such as value at risk.

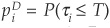

In Equation (5-4) we have derived the correlation formula for two binary events A and B. These two events can be joint defaults or joint downgrades, for example. Consider two firms originally rated i and j, respectively, and let D denote the default category. The marginal probabilities of default are  and

and  , while

, while  denotes the joint probability of the two firms defaulting over a chosen horizon. Equation (5-4) can thus be rewritten as

denotes the joint probability of the two firms defaulting over a chosen horizon. Equation (5-4) can thus be rewritten as

Obtaining individual probabilities of default per rating class is straightforward. These statistics can be read off transition matrices (we have discussed this at length in Chapter 2). The only unknown term that has to be estimated in Equation (5-26) is the joint probability.

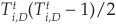

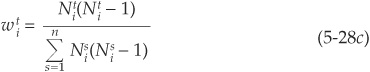

Consider the joint migration of two obligors from the same class i (say, a BB rating) to default D. The default correlation formula is given by Equation (5-26) with  , and we want to estimate

, and we want to estimate  .

.

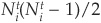

Assume that at the beginning of a year t, we have Nti firms rated i. From a given set with  elements, we can create

elements, we can create  different pairs. Using

different pairs. Using  to denote the number of bonds migrating from this group to default D, we can create

to denote the number of bonds migrating from this group to default D, we can create  defaulting pairs. Taking the ratio of the number of pairs that defaulted to the number of pairs that could have defaulted, we obtain a natural estimator of the joint probability. Considering that we have n years of data and not just 1, the estimator is

defaulting pairs. Taking the ratio of the number of pairs that defaulted to the number of pairs that could have defaulted, we obtain a natural estimator of the joint probability. Considering that we have n years of data and not just 1, the estimator is

where w is the weight representing the relative importance of a given year.

Among possible choices for the weighting schemes, we can find

or

or

Equation (5-27) is the formula used by Lucas (1995) and by Bahar and Nagpal (2001) to calculate the joint probability of default. Similar formulas can be derived for transitions to and from different classes. Both papers rely on Equation (5-28c) as the weighting system.

Although intuitive, estimator (5-27) has the drawback that it can generate spurious negative correlation when defaults are rare. Taking a specific year, we can indeed check that when there is only one default,  . This leads to a zero probability of joint default. However, the probability of an individual default is 1/N. Therefore, Equation (5-26) immediately generates a negative correlation since the joint probability is 0 and the product of marginal probabilities is (1/N)2.

. This leads to a zero probability of joint default. However, the probability of an individual default is 1/N. Therefore, Equation (5-26) immediately generates a negative correlation since the joint probability is 0 and the product of marginal probabilities is (1/N)2.

De Servigny and Renault (2003) therefore propose to replace Equation (5-27) with

This estimator of joint probability follows the same intuition of comparing pairs of defaulting firms with the total number of pairs of firms. The difference lies in the assumption of drawing pairs with replacement. de Servigny and Renault (2003) use the weights (5-28b). In a simulation experiment, they show that formula (5-29) has better finite sample properties than (5-27); i.e., for small samples (small N) using (5-29) and (5-26) provides an estimate that is on average closer to the true correlation than using (5-27) and (5-26).

Using the Standard & Poor’s CreditPro database that contains about 10,000 firms and 22 years of data (from 1981 to 2002), we can apply formulas (5-29) and (5-26) to compute empirical default correlations. The results are shown in Table 5-1.

TABLE 5-1

1-Year Default Correlations, All Countries, All Ratings, 1981–2002 (×100)

The highest correlations can be observed in the diagonal, i.e., within the same industry. Most industry correlations are in the range of 1 to 3 percent. Real estate and, above all, telecoms stand out as exhibiting particularly high correlations. Out-of-diagonal correlations tend to be fairly low.

Table 5-2 illustrates pairwise default correlations per class of rating.7 From these results we can see that default correlation tends to increase substantially as the rating deteriorates. This is in line with results from various studies of structural models and intensity-based models of credit risk that we consider below.

TABLE 5-2

1-Year Default Correlations, All Countries, All Industries, 1981–2002 (×100)

We will return to this issue later in this chapter when we investigate default correlation in the context of intensity models of credit risk.

So far we have only considered the 1-year horizon. This corresponds to the usual horizon for calculating VaR but not to the typical investment horizon of banks and asset managers. Tables 5-3 and 5-4 shed some light on the behavior of correlations as the horizon is lengthened. A marked increase can be observed when we extend the horizon from 1 to 3 years (Tables 5-1 and 5-3). Correlations seem to plateau between 3 and 5 years (Tables 5-3 and 5-4).

TABLE 5-3 3-Year Default Correlations, All Countries, All Ratings, 1981–2002 (×100)

TABLE 5-4

5-Year Default Correlations, All Countries, All Ratings, 1981–2002 (×100)

One explanation for this phenomenon can be that at the 1-year horizon, defaults occur primarily for firm-specific reasons (bad management, large unexpected loss, etc.) and therefore lead to low correlations. However, when the horizon is 3 to 5 years, industry and macroeconomic events start entering into effect, thereby pushing up correlations.

Similar calculations could be performed using downgrades rather than defaults. This could be achieved simply by substituting the number of downgrades for T in Equation (5-29). Correlations of downgrades would benefit from a much larger number of observations and would arguably be more robust estimates. They, however, raise new questions. Should one treat a two-notch downgrade as a one-notch downgrade? As two one-notch downgrades? Is a downgrade from an investment-grade rating to a speculative rating equivalent to any other downgrade? There are no simple answers to all these questions.

An alternative approach to deriving empirical default correlations is proposed by Gordy and Heitfield (2002). It relies on a maximum-likelihood estimation of the correlations using a factor model of credit risk. In this section we introduce this important class of credit risk models.8

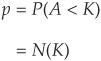

In a factor model, one assumes that a latent variable drives the default process: When the value A of the latent variable is sufficiently low (below a threshold K), default is triggered. It is customary to use the term “asset return” instead of “latent variable,” as it relates to the familiar Merton-type models where default arises when the value of the firm falls below the value of liabilities.

Asset returns for various obligors are assumed to be functions of common state variables (the factors) and of an idiosyncratic term Ai that is specific to each firm i and uncorrelated with the factors. The systematic and idiosyncratic factors are usually assumed to be normally distributed and are scaled to have unit variance and zero mean. Therefore the asset returns are also standard normally distributed. In the case of a one-factor model with systematic factor denoted as C, asset returns at a chosen horizon (say, 1 year) can be written as

such that

In order to calculate default correlation using Equation (5-26), we need to obtain the formulas for individual and joint default probabilities. Given the assumption about the distribution of asset returns, we have immediately

and

where  is the cumulative standard normal distribution. Conversely, the default thresholds can be determined from the probabilities of default by inverting the Gaussian distribution:

is the cumulative standard normal distribution. Conversely, the default thresholds can be determined from the probabilities of default by inverting the Gaussian distribution:  .

.

Figure 5-10 illustrates the asset return distribution and the default zone (the area where  ). The probability of default corresponds to the area below the density curve from −∞ to K.

). The probability of default corresponds to the area below the density curve from −∞ to K.

FIGURE 5-10

Asset Return Distribution

Assuming further that asset returns for obligors i and j are bivariate normally distributed,9 the joint probability of default is obtained using

Equations (5-32a and b) and (5-33) provide all the necessary building blocks to calculate default correlation in a factor model of credit risk.

Figure 5-11 illustrates the relationship between asset correlation and default correlation for various levels of default probabilities, using Equations (5-33) and (5-26). The lines are calibrated such that they reflect the 1-year probabilities of default of firms within all rating categories.10

FIGURE 5-11

Default Correlation versus Asset Correlation

It is very clear from the picture that as default probability increases, default correlation also increases for a given level of asset correlation. This implies that some of the increase in default correlation reported in Tables 5-2 to 5-4 will be captured by a factor model simply because default probabilities increase with the horizon. We will discuss below whether this effect is sufficient to replicate the empirically observed increase in correlations as the horizon is extended.

Lopez (2002) reports that asset correlations decrease in the probability of default. The overall impact of the horizon is therefore unclear in the context of a factor-based model: On the one hand, according to equity-based models, default correlations11 increase in the probability of default (which grows with the horizon), but on the other hand, Lopez claims that asset correlations decrease in the probability of default, which should lead to a fall in default correlations.

We have just seen that the formula for pairwise default correlation is quite simple but relies on asset correlation, which is not directly observable. It has become market practice to use equity correlation as a proxy for asset correlation. The underlying assumption is that equity returns should reflect the value of the underlying firms, and therefore that two firms with highly correlated asset values should also have high equity correlations.

To test the validity of this assumption, de Servigny and Renault (2003) have gathered a sample of over 1100 firms for which they had at least 5 years of data on the ratings, equity prices, and industry classification. They then computed average equity correlations across and within industries. These equity correlations were inserted in Equation (5-33) to obtain a series of default correlations extracted from equity prices. They then proceeded to compare default correlations calculated in this way with default correlations calculated empirically using Equation (5-29).

Figure 5-12 summarizes their findings. Equity-driven default correlations and empirical correlations appear to be only weakly related, or, in other words, equity correlations provide at best a noisy indicator of default correlations. This casts some doubt on the robustness of the market standard assumption and also on the possibility of hedging credit products using the equity of their issuer.

FIGURE 5-12

Empirical versus Equity-Driven Default Correlations

Although disappointing, this result may not be surprising. Equity returns incorporate a lot of noise (bubbles, etc.) and are affected by supply and demand effects (liquidity crunches) that are not related to the firms’ fundamentals. Therefore, although the relevant fundamental correlation information may be incorporated in equity returns, it is blended with many other types of information and cannot easily be extracted.

We mentioned earlier that empirical default correlation tends to increase substantially between 1 year and 3 to 5 years. We have also argued that a factor-based model will automatically generate increasing default correlation as the horizon increases. de Servigny and Renault (2003) show on their data set that a constant asset correlation cannot replicate the extent of this increase by the simple mechanical effect of the increase in default probabilities. In order to replicate the empirically observed increase, one needs to increase substantially the level of asset correlation in accordance with the chosen horizon.

In conclusion, using equity correlation without adjusting for the horizon is insufficient. One needs either to take into account the term structure of correlations or to calibrate a copula. The parameter of such a copula driving the fatness of the tail would be linked to the targeted horizon.

We have seen earlier in Chapter 4 that intensity-based models of credit risk were very popular among practitioners for pricing defaultable bonds and credit derivatives. We will return to these models in later chapters on spreads and credit derivatives. This class of model, where default occurs as the first jump of a stochastic process, can also be used to analyze default correlations.

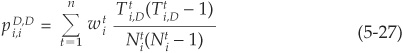

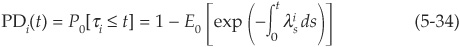

In an intensity model, the probability of default over [0,t] for a firm i is

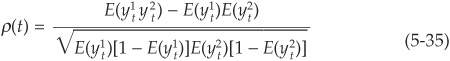

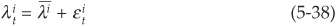

where  is the intensity of the default process, an τi is the default time for firm i. The linear default correlation (5-26) can thus be written as

is the intensity of the default process, an τi is the default time for firm i. The linear default correlation (5-26) can thus be written as

where

Yu (2002b) implements several intensity specifications belonging to the class of conditionally independent models including those of Driessen (2002) and Duffee (1999) using empirically derived parameters. These models are similar in spirit to the factor models described in Appendix 5A except that the factor structure is imposed on the intensity rather than on asset returns.

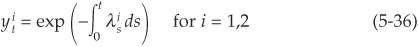

The intensities are functions of a set of k state variables  defined below. Conditional on a realization of Xt, the default intensities are independent. Dependency therefore arises from the fact that all intensities are functions of Xt.

defined below. Conditional on a realization of Xt, the default intensities are independent. Dependency therefore arises from the fact that all intensities are functions of Xt.

Common choices for the state variables are term structure factors (level of a specific Treasury rate, slope of the Treasury curve), other macroeconomic variables, firm-specific factors (leverage, book-to-market ratio), etc.

For example, the two state variables in Duffee (1999) are the two factors of a riskless affine term structure model (see Duffie and Kan, 1996). Driessen (2002) also includes two term structure factors and adds two further common factors to improve the empirical fit.

In most papers including those mentioned above, the intensities  are defined under the risk-neutral measure (see the definition in Chapter 8), and they therefore yield correlation measures under that specific probability measure. These correlation estimates cannot be compared directly with empirical default correlations as shown in Tables 5-1 to 5-4. The latter are indeed calculated under the subjective historical measure.

are defined under the risk-neutral measure (see the definition in Chapter 8), and they therefore yield correlation measures under that specific probability measure. These correlation estimates cannot be compared directly with empirical default correlations as shown in Tables 5-1 to 5-4. The latter are indeed calculated under the subjective historical measure.

Yu (2002b) relies on results from Jarrow, Lando, and Yu (2001), who prove that asymptotically in a very large portfolio, average intensities under the risk-neutral and historical measures coincide. Yu argues that given that the parameters of the papers by Driessen and Duffee are estimated over a large and diversified sample, this asymptotic result should hold. He then computes default parameters from the estimated average parameters of intensities reported in Duffee (1999) and Driessen (2002) using Equations (5-35) and (5-36).

These results are reported in Tables 5-5 and 5-6. The model by Duffee (1999) tends to generate much too low default correlations compared with other specifications.

TABLE 5-5

Default Correlations Inferred from Duffee (1999), in Percent

TABLE 5-6

Default Correlations from Driessen (2002), in Percent

Tables 5-7 and 5-8 are presented for comparative purposes. As Tables 5-6 and 5-8 show, Driessen (2002) yields results that are comparable to those of Zhou (2001).

TABLE 5-7

Average Empirical Default Correlations [Using Equation (5-29)], in Percent

TABLE 5-8

Default Correlations from Zhou (2001), in Percent

Both intensity-based models exhibit higher default correlations as the probability of default increases and as the horizon is extended.

Yu (2002b) notices that the asymptotic result by Jarrow, Lando, and Yu (2001) may not hold for short bonds because of tax and liquidity effects reflected in the spreads. He therefore proposes an ad hoc adjustment of the intensity:

where t is time and a and b are constants obtained from Yu (2002a).

Tables 5-9 and 5-10 report the liquidity-adjusted tables of default correlations. The differences with Tables 5-5 and 5-6 are striking. First, the level of correlations induced by the liquidity-adjusted models is much higher. More surprisingly, the relationship between probability of default and default correlation is inverted: The higher the default risk, the lower the correlation.

TABLE 5-9

Liquidity-Adjusted Default Correlations Inferred from Duffee (1999), in Percent

TABLE 5-10

Liquidity-Adjusted Default Correlations Inferred from Driessen (2002), in Percent

The modeling approach proposed by Yu (2002b) relies critically on the result by Jarrow, Lando, and Yu (2001) about the equality of risk-neutral and historical intensities which only holds asymptotically. If the assumption is valid, then the risk-neutral intensity calibrated on market spreads can be used to calculate default correlations for risk management purposes.

Das, Freed, Geng, and Kapadia (2002) take a different approach and avoid extracting information from market spreads. They gather a large sample of historical default probabilities derived from the RiskCalc model for public companies from 1987 to 2000. Falkenstein (2000) describes this model that provides 1-year probabilities for a large sample of firms.

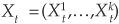

Das, Freed, Geng, and Kapadia (2002) start by transforming the default intensity into average intensities over 1-year periods. Using Equation (5-34) and an estimate of default probabilities, they obtain a monthly estimate of default intensity by

The time series of intensities are then split into a mean component  and a zero-mean stochastic component

and a zero-mean stochastic component

Das, Freed, Geng, and Kapadia (2002) study the correlations between  and

and  for two firms i and j. Table 5-11 reports their results for various time periods and rating classes. These results cannot be directly compared with those presented above because they are correlations of intensities and not of default events.

for two firms i and j. Table 5-11 reports their results for various time periods and rating classes. These results cannot be directly compared with those presented above because they are correlations of intensities and not of default events.

TABLE 5-11

Average Correlations between Intensities

Other specifications for the intensity processes are also tested by the authors, including an autoregressive process and a model with asymmetric correlation structure (different correlations for increases and decreases in default intensities). These are also used in the model we now present about applying copulas to default dependencies.

Das and Geng (2002) perform an extensive empirical analysis of alternative specifications of the joint distribution of defaults. Their approach differs from that of Yu (2002b) in that they rely on copula functions and thus estimate marginal distributions separately from the multivariate distribution.

The authors proceed in three steps:

The first step consists of modeling the dynamics of the mean default rate for each rating group (they divide the Moody’s rating scale into six rating categories such that rating

The first step consists of modeling the dynamics of the mean default rate for each rating group (they divide the Moody’s rating scale into six rating categories such that rating  corresponds to a higher default probability than rating i). Two specifications are tested: a jump process and a regime-switching (high probability, low probability) model.

corresponds to a higher default probability than rating i). Two specifications are tested: a jump process and a regime-switching (high probability, low probability) model.

Then individual default probabilities (marginal distributions) are calibrated using one of three alternative probability laws: Gaussian, student-t, or skewed double exponential. The parameters of these distributions are estimated by maximum likelihood, and statistical tests are performed to determine which distribution is better able to fit each time series of default probability. Their data are the same as in Das, Freed, Geng, and Kapadia (2002).

Then individual default probabilities (marginal distributions) are calibrated using one of three alternative probability laws: Gaussian, student-t, or skewed double exponential. The parameters of these distributions are estimated by maximum likelihood, and statistical tests are performed to determine which distribution is better able to fit each time series of default probability. Their data are the same as in Das, Freed, Geng, and Kapadia (2002).

Finally, copula functions are used to combine marginal distributions into one multivariate distribution and are constrained to match pairwise correlations between obligors. Four specifications of the copula functions are tested: Gaussian, Gumbel, Clayton, and t-copulas (see the section on correlations and other dependency measures earlier in this chapter).

Finally, copula functions are used to combine marginal distributions into one multivariate distribution and are constrained to match pairwise correlations between obligors. Four specifications of the copula functions are tested: Gaussian, Gumbel, Clayton, and t-copulas (see the section on correlations and other dependency measures earlier in this chapter).

While standard test statistics are available to identify the marginal distribution fitting the data most closely, multivariate distribution tests in order to calibrate copulas are less widespread. Das and Geng (2002) therefore develop a goodness-of-fit metric that focuses on several criteria.

Goodness of Fit Das and Geng (2002) choose three features of the multivariate distribution that they think are the most important to calibrate:

The level of intensity correlation. The copula should permit the calibration of empirically observed correlations.

The level of intensity correlation. The copula should permit the calibration of empirically observed correlations.

Correlation asymmetry. It should allow for different levels of correlations depending on the level of PD.

Correlation asymmetry. It should allow for different levels of correlations depending on the level of PD.

Tail dependency. The dependency in the lower and upper tails is also a desirable property to calibrate (see the section presented earlier on the copula).

Tail dependency. The dependency in the lower and upper tails is also a desirable property to calibrate (see the section presented earlier on the copula).

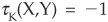

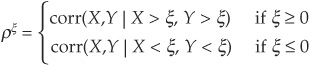

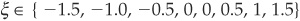

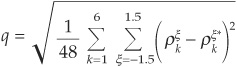

These three features can be measured on a graph of exceedance correlation (Figure 5-13). A correlation at an exceedance level ξ is the correlation  between two random variables X and Y conditional on both variables registering increases or decreases of more than ξ standard deviations from their means. For X and Y centered and standardized, it is defined as

between two random variables X and Y conditional on both variables registering increases or decreases of more than ξ standard deviations from their means. For X and Y centered and standardized, it is defined as

FIGURE 5-13

The Asymmetric Correlation Structure

The variable of interest (for which we consider exceedance) is the total hazard rate THRt defined as the sum of the default intensities of all firms at a point in time t. The sample of PDs is then split into categories corresponding to the exceedance levels:

i.e., PDs that are more than 1.5, 1, or 0.5 standard deviation below or above their mean, etc.

Figure 5-13 incorporates all three features of interest. The level of correlation is immediately visible (level of the curves). The asymmetry is also obvious: We observe much higher correlations for positive changes in intensity. The level of tail dependency can be measured by the slope of the lines. As we go further in the tails, the slope decreases, which reflects tail dependency.12

The metric used by Das and Geng (2002) to gauge the quality of the fit of the copula is the average of the squared deviations between the exceedance empirically observed correlations (as shown in Figure 5-13) and those produced by the copula. The idea is therefore to minimize

where k denotes the rating and ξ denotes the exceedance level. Starred correlations are those produced by the copula.

Results The main results of this extensive empirical study are the following:

The regime-switching model (high probability, low probability) performs better than the jump model in fitting the mean default rates.

The regime-switching model (high probability, low probability) performs better than the jump model in fitting the mean default rates.

The skewed double-exponential distribution seems an appropriate choice for the marginal distribution.

The skewed double-exponential distribution seems an appropriate choice for the marginal distribution.

Combined with the Clayton copula, the skewed double-exponential distribution provides the best fit to the data.

Combined with the Clayton copula, the skewed double-exponential distribution provides the best fit to the data.

The calibration of marginal distributions is not indifferent to the outcome of the copula to fit the joint distribution.

The calibration of marginal distributions is not indifferent to the outcome of the copula to fit the joint distribution.

The last point deserves a little more explanation. The use of copulas is often motivated by the fact that one can separate the task of estimating marginal distributions from that of fitting the multivariate distribution. While this is true, this empirical study shows that the choice of marginal distributions does impact on the choice of the best copula and therefore on the shape of the multivariate distribution. This result is probably dependent on the metric used to select the appropriate specification.

On the whole this broad study sheds some light on many issues of interest to credit portfolio managers. The results reported above are difficult to compare with others, as the empirical literature on applications of copulas to credit risk is very thin. It would, for example, be interesting to check the sensitivity of the conclusions to the choice of metric or to the frequency of data observations.

In this chapter we have discussed default dependencies. We have shown that although a partial measure of joint variations, correlations still play a primordial role in financial applications. We have introduced the concept of copula, which proves a promising tool for capturing dependency in credit markets. However, the appropriate choice of a specific copula function remains an open issue.

As far as empirical results are concerned, some stylized facts clearly emerge: Correlations increase markedly in the horizon and appear to be time-dependent. Depending on the choice of model, correlations will either increase or decrease in the probability of default. Empirical correlations increase in default probability, as do correlations implied by an equity-type model of credit risk. On the other hand, intensity-based models tend to generate decreasing correlations as credit quality deteriorates.

We believe that three avenues of research will yield interesting results in the coming years. The first one involves a careful analysis of the common factors driving correlations. Up to now, empirical analyses of default correlations have considered obvious choices such as macroeconomic or industry factors. No convincing systematic study of potential determinants has yet been published to our knowledge.

Second, contagion models are still in their infancy. Davis and Lo (1999a, 1999b) and Yu (2002b) provide interesting insights, but more sophisticated models will no doubt be proposed. Biomedicine researchers have developed an extensive literature on contagion that has not yet been taken on board by financial researchers.

Finally, we have seen several attempts to model correlations under the physical probability measure. Few of these have yet taken the direct approach of modeling joint durations between rating transitions or defaults. This will doubtless be a research direction in the near future.

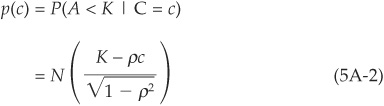

The basic setup of a one-factor model of credit risk involves the modeling of asset returns A at a chosen horizon T as a sum of a systematic factor C and an idiosyncratic factor ε:

where A, C, and, ε are assumed to follow standard normal distributions.

The probability of default p is the probability that the asset return is below a threshold K:

Conditional on a specific realization of the factor C = c, the probability of default is

Furthermore, conditional on c, defaults become independent, which enables simple computations of portfolio loss probabilities.

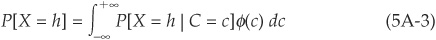

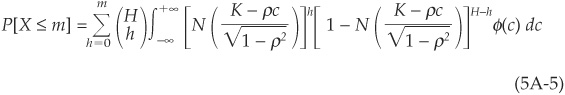

Assume that we have a portfolio of H obligors with the same probability of default and the same factor loading ρ. Out of these obligors, one may observe X= 0, 1, 2 or up to H defaults before the horizon T. Using the law of iterated expectations, the probability of observing exactly h defaults can be written as the expectation of the conditional probability:

where φ(.) is the standard normal density.

Given that defaults are conditionally independent, the probability of observing h defaults conditional on a realization of the systematic factor will be binomial such that

Using Equations (5A-2) and (5A-3), we then obtain the cumulative probability of observing less than m defaults:

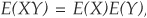

The graph in Figure 5A-1 is a plot of  for various assumptions of factor correlation from

for various assumptions of factor correlation from  percent to

percent to  percent. The probability of default is assumed to be 5 percent for all

percent. The probability of default is assumed to be 5 percent for all  obligors.

obligors.

FIGURE 5A-1

Impact of Correlation on Portfolio Loss Distribution

The mean number of defaults is 5 for all three scenarios, but the shape of the distribution is very different. For ρ = 0 percent, we observe a roughly bell-shaped curve centered on 5. When correlation increases, the likelihood of joint bad events increases, implying a fat right-hand tail. The likelihood of joint good events (few or zero defaults) also increases, and there is a much larger chance of 0 defaults.

In Chapter 3 we discussed the simple Merton (1974) model of credit risk. One of the weaknesses of this model was that default is only allowed at the maturity of the debt T.

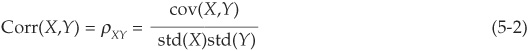

The Merton framework has been extended to include an early default barrier by Black and Cox (1976) and many subsequent authors. Zhou (2001) was the first to derive a formula for default correlation in a structural model with a barrier. Using Equation (5-30), we need to derive the formulas for univariate and bivariate default probabilities of default:  and

and  . Univariate probabilities of default correspond to the probability that the value of firm 1 or firm 2 hit their default barriers (see Figure 5B-1). The default times are denoted as τ1 and τ2.

. Univariate probabilities of default correspond to the probability that the value of firm 1 or firm 2 hit their default barriers (see Figure 5B-1). The default times are denoted as τ1 and τ2.

FIGURE 5B-1

First Passage Times of Firms i and j to Default Boundary

The probabilities of default  and

and  correspond to the probability that a geometric Brownian motion (the firm value process) hits an exponentially drifting boundary (the default threshold) before some time T. This formula can be found in textbooks such as Harrison (1985) or Musiela and Rutkowski (1998).

correspond to the probability that a geometric Brownian motion (the firm value process) hits an exponentially drifting boundary (the default threshold) before some time T. This formula can be found in textbooks such as Harrison (1985) or Musiela and Rutkowski (1998).

The main contribution of Zhou (2001) is to derive the complex joint probability